Abstract

Mechanical frequency combs (MFCs), built upon wave mixing in mode-coupled micromechanical resonators, are often limited by their narrow and sparse spectra due to small energy exchange rates. However, the ability to model and enhance the energy exchange rate remains insufficiently explored. Here, we systematically propose coupling enhancement schemes for different architectures, and present a coupling-enhancement anchor design to achieve the giant energy exchange rate between the coupled modes of our device, enabling the broadening of comb spacing to overlap harmonic clusters of MFCs, leading to the generation of supercontinuum frequency combs. A theoretical model describing the physical relationship between the energy exchange rate and resonator parameters is developed, which is validated by the consistent correlation between the energy exchange rate and the induced mode amplitude under varying driving frequencies. Our finding builds a design-oriented approach to raise the energy exchange rate in mode-coupled resonators and to construct decade-wide dense spectral range of MFCs, paving the way for their potential applications in precision timekeeping and signal processing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Conventional linear, single-mode resonant micro-electro-mechanical systems (MEMS) have been extensively utilized in timing, sensing, and signal processing applications due to their high-quality factors, low power consumption, and ease of integration1,2. However, as system requirements grow more demanding, the exploration of nonlinear MEMS architectures, particularly those involving modal interactions, has unlocked new dynamic functionalities by facilitating energy transfer between distinct vibrational modes, capabilities that are unattainable in linear devices3,4. This modal energy transfer pathway allows the system to access complex dynamic behaviors, such as bifurcations5,6,7, modal localization8,9,10, and random process11,12. Many prior works have intentionally designed weak energy exchange rate to enhance sensitivity to perturbations or to study subtle energy dissipation mechanisms, as limited modal energy transfer enables disturbances to remain localized, amplifying mode-specific responses within individual modes. This strategy offers novel opportunities in precision sensing and dynamic filtering.

Beyond these applications, mode-coupled MEMS resonators have also been demonstrated as platforms for generating micromechanical frequency combs (MFCs) characterized by a series of equally spaced spectral lines, with potential for chip-scale precision timing and frequency synthesis in recent years13,14. The theoretical foundation of MFCs was first established by Cao et al. through the nonlinear modal coupling inside a Fermi-Pasta-Ulam \(\alpha\) chain15. Following this, a variety of MFC implementations have been realized utilizing mode coupling. Ganesan et al. experimentally demonstrated MFCs via autoparametric subharmonic excitation in piezoelectric resonators16,17,18. Czaplewski et al. employed 1:3 internal resonance to induce MFCs through saddle-node bifurcations19,20. Apart from these works, MFCs have been also studied through various means, including parametric excitation21,22,23, internal resonance24,25,26,27, and self-excitation by negative dissipation28,29.

Despite the extensive research effort in MFCs, the comb spacing is generally less than one-tenth of the corresponding excitation frequency, the number of comb lines is few, and the bandwidth remains very narrow, typically unable to span a full frequency octave of the excitation signal, significantly limiting their potential in precision timing. We hypothesize that tuning (mostly raising) the comb spacing could help solving this challenge. However, the ability to systematically model and tune the energy exchange rate among coupled modes, a key parameter governing comb spacing, remains insufficiently explored. Among them, Okamoto et al. investigated the dynamic coupling rate between two GaAs-based mechanical resonators under modulated pumping signals30. Chen et al. directly observed coherent energy transfer between coupled vibrational modes and quantitatively characterized the energy exchange rate within the internal resonance regime31. Zhang et al. indicated that the energy exchange rate is impacted by asymmetry-induced energy localization and can be enhanced by nonlinearity32. Park et al. demonstrated the formation and evolution of MFCs using non-degenerate parametric pumping, and discussed how comb spacing varies with pump amplitude and frequency33. Zhou et al. designed a vacuum-sealed microelectromechanical silicon ring resonator to study the first-order sideband dynamical coupling process with great control flexibility34. In our previous work, we generated MFCs in a 1:3 internal resonance device and studied the evolution of comb spacings due to period-doubling bifurcation and cyclic-fold bifurcation35,36. However, it still remains unknown on the relationship between the energy exchange rate and the comb spacing, which hinders a strategy toward expanded and denser MFC spectra.

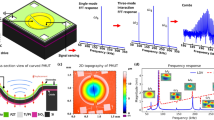

Unlike the weak coupling favored in sensing applications, the formation of stable MFCs requires strong mode coupling to sustain efficient energy exchange rate and enforce modal-coupling conditions37. To address the limited tunability of energy exchange rates in existing MFC systems, we investigate how structural design can be systematically employed to enhance modal coupling strength, including beam geometry variation, symmetry breaking, and coupling interface modification. Figure 1 illustrates several representative structural optimization strategies aimed at reinforcing modal coupling in both single and coupled MEMS resonators, thereby enabling stronger energy exchange rate critical for broadband MFC generation. In the fixed anchor design shown in Fig. 1a, the flexural mode and torsional mode of the resonator are nearly orthogonal along the out-of-plane (Z-axis) direction, resulting in minimal energy exchange. To overcome this, we redesign a truss anchor structure, where the truss can undergo out-of-plane motion along z-axis easily. This modification enhances the hybridization between two initially independent modes (the flexural mode along the x-axis and the torsional mode along the z-axis), thereby increasing the modal interaction. The uniform clamped–clamped beam in Fig. 1b exhibits inherent orthogonality between its second and third flexural modes, thus suppressing modal energy exchange under linear conditions. However, Asadi et al. introduced asymmetry into the beam structure and enables non-orthogonal modal projection, thereby facilitating coupling strength between these otherwise decoupled modes38. Rahmanian et al. achieved more than 150 equidistant peaks in the case of a 2:1 modal interaction in an imperfect nano-cantilever beam where energy exchange was enhanced unintentionally26. Beyond single-resonator designs, modal coupling strength in multi-resonator systems can also be enhanced. As illustrated in Fig. 1c, the electrostatic coupling is replaced with a mechanical connection using short coupling beams, achieving nearly a tenfold increase in coupling strength. In Fig. 1d, Santos et al. investigated tuning-fork structures and found that decreasing the spacing between cantilever beams while increasing the base anchor size led to an exponential increase in modal coupling strength, due to enhanced mechanical interaction at the shared anchor39. These diverse architecture designs demonstrate the broad applicability of structural optimization as an effective strategy for enhancing modal coupling strength in both single and multi-resonator systems.

In this Article, we demonstrate MFCs with drastically increased comb spacing by giant energy exchange rate between the coupled flexural and torsional modes in a truss-anchored resonator. A theoretical model is developed to quantitatively relate the energy exchange rate to key resonator parameters, providing a foundation for controlling the spectral properties of MFCs. The model is validated through experiments under varying drive frequencies, confirming the predicted correlation between the giant modal energy exchange rate and the MFC spectra. By employing a mode-coupled resonator with a giant energy exchange rate, we achieve supercontinuum MFCs featuring broader comb spacings and decade-wide spectral range.

Results

Device characterization and analytical modelling

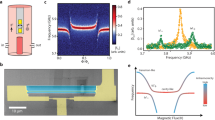

The schematic diagrams of two capacitive MEMS resonators, namely Device A and Device B, used in this paper are shown in Fig. 2. The two resonators share similar geometry size and both exhibit 1:3 internal resonance between the flexural mode and the torsional mode. The two resonators are both driven by an ac voltage \({V}_{{ac}}\) and a bias voltage \({V}_{{dc}}\) in a vacuum chamber with a pressure less than 0.1 Pa. The mechanical motions are monitored mainly by optical measurement with a laser spot at similar positions on both devices. Device A, shown in Fig. 2a, features a shuttle mass supported by four fixed-guided tether beams, resulting in a relatively weak modal coupling because the torsional mode is not easy to excite. In contrast, Device B incorporates a modified anchored structure for coupling enhancement, as shown in Fig. 2b, where one side of the tethers is anchored on a movable truss that can displace vertically in z-axis (the same as that in Fig. 1a), resulting in a strong coupling between the two modes. The mode shapes and resonance frequencies of the two resonators are analyzed through COMSOL simulation. Interestingly, under identical driving force, Device A exhibits a larger torsional amplitude than Device B, as part of the input energy in Device B is absorbed by the bending of the truss. This enhanced coupling enables a higher energy exchange rate in Device B, allowing for larger driving forces to be applied without damaging the structure.

Figure 2 also illustrates the simulated mode shapes, where \({u}_{1}\) denotes the vibration amplitude of the flexural mode while \({\phi }_{2}\) corresponds to the rotational angle of the torsional mode. To facilitate the derivation of the coupled dynamic system, the rotational angle \({\phi }_{2}\) is equivalently transformed into a translational displacement \({u}_{2}\) by introducing an effective mass \({m}_{2}\) that accounts for the energy associated with torsional motion. Based on this equivalence in the coupling system, due to the geometric nonlinearity of beams with a large length-to-width ratio more than 230:4, the stiffness response includes only linear and cubic terms. Regarding the coupling mechanism, cubic terms alone satisfy the frequency–phase matching condition required for internal resonance, whereas the frequency components arising from linear or other nonlinear interactions cannot effectively contribute to the energy transfer. Hence, a two-mode coupled system with Duffing nonlinearity subjected to an electrostatic force can be established as:

where \({m}_{i}\) and \({\gamma }_{i}\) are the effective mass and damping coefficient, \({k}_{11}\) and \({k}_{21}\) are linear stiffness coefficients, \({k}_{13}\) is the Duffing nonlinear stiffness coefficient, \(\kappa\) is the coupling coefficient, and \(F\) is the driving amplitude of the external force with a driving frequency \(\Omega\).

After applying mass and stiffness normalization to the coupled equations, the amplitudes \({u}_{1}\) and \({u}_{2}\) can be transferred into non-dimensional parameters \({q}_{1}\) and \({q}_{2}\), and the coupled equations can be written as:

where \(\tau =\sqrt{\frac{{k}_{11}}{{m}_{1}}}t={\omega }_{1}t\), \({Q}_{2}=\frac{{m}_{2}{\omega }_{2}}{{\gamma }_{2}}\), \(p=\frac{{\omega }_{2}}{{\omega }_{1}}\), \(h=\frac{1}{\sqrt{\frac{{k}_{13}}{{k}_{11}}-\frac{\kappa }{{k}_{11}}}}\), \({c}_{1}={\gamma }_{1}\sqrt{\frac{1}{{k}_{11}{m}_{1}}}\), \({c}_{2}=\frac{p}{{Q}_{2}}\), \(\alpha =\frac{\kappa {h}^{2}}{{k}_{11}}\), \(f=\frac{F}{{k}_{11}h}\), and \({\omega }_{d}=\frac{\Omega }{{\omega }_{1}}\). The coupled dynamic equations are numerically solved using a four-step variable length Runge–Kutta method. Resonator parameters can be extracted by fitting the simulated amplitude-frequency response curves to experimental data (details about parameter extraction is in Supplementary Section 4 of Supplementary Information).

By tuning the ac voltage \({V}_{{ac}}\) loaded on the devices while maintaining a fixed bias voltage \({V}_{{dc}}\) (24 V for Device A and 50 V for Device B), the amplitude-response curves of the flexural mode under different driving forces are plotted in Fig. 3. Solid lines represent experimental measurements, while dotted lines denote simulation results. For Device A, the natural frequency is ~50,095 Hz. At low drive levels (\({V}_{{ac}}\) less than 400 mV), a typical stiffness hardening behavior is observed. When the input excitation fails to sustain the nonlinear dynamics, the system exhibits a downward transition to the lower response branch, as demonstrated in Fig. 3a. As the driving amplitude increases from 400 to 1000 mV, a primary Hopf bifurcation emerges near one-third of the torsional mode frequency, resulting in the initiation of internal mode coupling. The bifurcation frequency remains nearly constant in the internal resonance region, as the driving energy is redistributed from the flexural to the torsional mode and is insufficient to maintain large-amplitude vibrations in both modes simultaneously. Once the input exceeds 1500 mV, the system overcomes the primary Hopf bifurcation and stabilizes on the upper branch. Within the internal resonance region, a Neimark–Sacker bifurcation is triggered to generate MFCs. For Device B, with a natural frequency of ~50,255 Hz, a similar stiffness hardening trend is observed in Fig. 3c. However, due to the enhanced coupling strength, the Hopf bifurcation location remains effectively stationary over a much wider range of excitation amplitudes, spanning from 600 to 4000 mV. At the same time, a stiffness-softening trend is observed at the high-amplitude end under 4\({V}_{{ac}}\) excitation, which results from the combined effects of a high energy exchange rate that redistributes a substantial portion of the vibration energy from the flexural mode to the torsional mode and reduces the effective stiffness of the flexural mode, together with the additional electrostatic softening effect introduced by the 4\({V}_{{ac}}\) application. Due to the measurement limitations of the operational amplifier chip, MFCs induced by Neimark–Sacker bifurcation under higher driving voltages are challenging to capture through electrical detection. Therefore, we subsequently adopted optical measurement for characterization. Consequently, the energy is more efficiently transferred, leading to a bifurcation behavior that spans a broader excitation range. The resonator parameters are fitted and listed in the following Table 1. The coupling coefficient \(\kappa\) is estimated by tuning the parameters of the coupled equations such that the bifurcation points under small-amplitude excitation in the simulations (Fig. 3b, d) matches the experimental results (Fig. 3a, c).

Comb spacing is an essential metric for MFCs, which represents the amplitude modulation period of the vibration signal and is determined by the energy exchange rate \({\gamma }_{{ex}}\). With the extracted parameters, we can calculate the normalized coupling coefficients \(\alpha =\kappa \cdot \frac{{h}^{2}}{{k}_{11}}\) as \({\alpha }_{A}=0.0165\) and \({\alpha }_{B}=0.3155\), and then quantify the energy exchange rate \({\gamma }_{{ex}}\) between the two coupled modes. From Eqs. (3) and (4), we can derive the power transferred from \({q}_{1}\) to \({q}_{2}\) as:

where \({A}_{1}\) and \({A}_{2}\) are the corresponding amplitude of \({q}_{1}\) and \({q}_{2}\) while \({\phi }_{\mathrm{1,0}}\) and \({\phi }_{\mathrm{3,0}}\) are the corresponding phase. To calculate the energy exchange rate \({\gamma }_{{ex}}\), we divide \(\bar{P}\) by the energy \(E\) of \({q}_{1}\), where \({E}_{1}={\frac{1}{2}K}_{11}{A}_{1}^{2}=\frac{1}{2}{A}_{1}^{2}\), because \({K}_{11}\) has been stiffness normalized. Hence, we can relate the formula of energy exchange rate \({\gamma }_{{ex}}\) to other key factors by a coefficient \(C\):

Not considering the complex bifurcations within the MFCs pattern, we can conclude that the energy exchange rate\(\,{\gamma }_{{ex}}\), also as the comb spacing of MFCs, is proportional to the coupling coefficient, amplitudes of the coupled modes, driving frequency, and the phase difference between the two coupled modes. Through structural optimization, the coupling coefficient can be enhanced by an order of magnitude, which significantly increases the energy exchange rate without the risks of device damage or excessive power consumption that may arise from merely increasing the driving voltage.

MFCs evolution and exergy exchange rate

To further verify the relationship between the energy exchange rate\(\,{\gamma }_{{ex}}\) and resonator parameters, optical measurements are performed at a 2-Hz interval to record the torsional mode amplitude \({A}_{2}\) and the corresponding energy exchange rate\(\,{\gamma }_{{ex}}\) for both Devices A and B under varying driving frequencies. To ensure the consistency of the proportional coefficient \(C\), the analysis is restricted to data within the same MFCs bifurcation regime, where flexural mode amplitude \({A}_{1}\) and phase difference \({3\phi }_{\mathrm{1,0}}-{\phi }_{\mathrm{3,0}}\) hardly change, as illustrated in Fig. 4. The blue asterisks represent the experimental energy exchange rate \({\gamma }_{{ex}}\) and the red asterisks represent the measured torsional amplitude \({A}_{2}\).

In the case of Device A, the driving voltage is fixed at \({{\rm{V}}}_{{\rm{dc}}}=24{\rm{V}}\) and \({{\rm{V}}}_{{\rm{ac}}}=1.5{\rm{V}}\). The driving frequency is swept from 59,353 Hz to 59,367 Hz. As shown in Fig. 4a, both the energy exchange rate \({\gamma }_{{ex}}\) and amplitude \({A}_{2}\) initially increase with driving frequency and then decrease. At \({\omega }_{d}=59,353{\rm{Hz}}\times 2{\rm{\pi }}\), the corresponding MFCs spectrum exhibits a relatively low energy exchange rate of 326.15 Hz and a torsional amplitude of 122.48 nm. As the frequency increases to 59,363 Hz, \({\gamma }_{{ex}}\) reaches its maximum of 332.15 Hz, accompanied by the highest torsional amplitude of 148.37 nm. Beyond this point, further increase in the driving frequency leads to a decline in both parameters. At \({\omega }_{d}=59,367{\rm{Hz}}\times 2{\rm{\pi }}\) Hz, the energy exchange rate \({\gamma }_{{ex}}\) drops to 328.65 Hz and the amplitude \({A}_{2}\) decreases to 133.17 nm, indicating a limit in the comb spacing expansion before the system transitions into a new dynamical state via a cyclic-fold bifurcation. The close agreement between the two nonlinear trends confirms a positive correlation between \({\gamma }_{{ex}}\) and \({A}_{2}\), validating the theoretical relationship within the observed frequency range.

Remarkably, Device B demonstrates a similar nonlinear response in Fig. 4b, where the trends of energy exchange rate \({\gamma }_{{ex}}\) and amplitude \({A}_{2}\) show strong consistency, reinforcing the validity of the correlation described in Eq. (6). It is important to emphasize that due to energy absorption by the bending of the truss, the measured absolute value of the torsional amplitude \({A}_{2}\) cannot directly quantify the exact amount of energy transferred (details about resonator characterization is in Supplementary Section 3 of Supplementary Information). However, a positive correlation between the trend of \({A}_{2}\) and \({\gamma }_{{ex}}\) remains evident. When the driving frequency is swept from 50,830 Hz to 50,840 Hz, \({\gamma }_{{ex}}\) increases rapidly from 1942.84 Hz to 2126.92 Hz, accompanied by a corresponding rise in \({A}_{2}\) from 9.62 nm to 14.55 nm. Beyond 50,840 Hz, both parameters continue to grow but at a slower rate, indicating the proximity of a cyclic-fold bifurcation. The mutual agreement of the nonlinear increasing rates of \({\gamma }_{{ex}}\) and \({A}_{2}\) also proves the positive correlation between them.

With parameters summarized in Table 1 and fixed driving amplitudes, the simulated evolution of MFCs for Devices A and B are obtained to validate the accuracy of the theoretical model, where the red and blue dots represent the simulated energy exchange rate \({\gamma }_{{ex}}\) and torsional amplitude \({A}_{2}\), respectively as shown in Fig. 4c, d. For Device A, the simulation captures the nonlinear growth trends of both \({\gamma }_{{ex}}\) and \({A}_{2}\) over the frequency range of 59,347–59,358 Hz in Fig. 4c when the flexural mode amplitude \({A}_{1}\) is ~3 μm. The results further confirm the positive correlation between these two quantities as observed experimentally. For Device B, the much-increased value of the torsional amplitude \({A}_{2}\) is calculated from the dynamic Eqs. (3) and (4), not considering the energy consumption of the truss. Device B exhibits a comparable nonlinear relationship between \({\gamma }_{{ex}}\) and \({A}_{2}\) from 51,030 Hz to 51,072 Hz as depicted in Fig. 4d.

To determine the proportional coefficient \(C\) in Eq. (6), we extracted the amplitudes \({A}_{1}\) and \({A}_{2}\) under various driving frequencies. As shown in Fig. 5, a linear fit for Device A yields a slope of \({C}_{A}=0.00183\) with a coefficient of determination \({R}^{2}=0.9951\). Due to its fixed anchor structure, the power transmission rate \(\alpha {A}_{1}{A}_{2}{\omega }_{d}\sin \left({3\phi }_{\mathrm{1,0}}-{\phi }_{\mathrm{3,0}}\right)\) from \({q}_{1}\) to \({q}_{2}\) remains relatively low, leading to a small energy exchange rate. In contrast, Device B featuring a truss anchor design exhibits an over two-order-of-magnitude improvement in power transmission rate between modes. The corresponding linear fitted slope of \({C}_{B}=0.00194\) with \({R}^{2}=0.9949\) is demonstrated in Fig. 5, indicating a giant enhancement in energy exchange rate. Although there is a slight deviation between \({C}_{A}\) and \({C}_{B}\) caused by the different phase difference \({3\phi }_{\mathrm{1,0}}-{\phi }_{\mathrm{3,0}}\), the consistent nonlinear trend between energy exchange rate and driving frequency across both devices confirms the validity of the theoretical proportionality between the energy exchange rate and resonator parameters. Hence, the theoretical model of Eq. (6) has been proved significant guidance for us to control the spectral range and comb spacings of MFCs.

Giant \({{\boldsymbol{\gamma }}}_{{\boldsymbol{ex}}}\) induced supercontinuum MFCs

To further validate the tunability of the energy exchange rate \({\gamma }_{{ex}}\), a comparative analysis of Devices A and B under varying excitation levels is carried out within the same vacuum environment. The results, presented in Fig. 6, highlight the progressive development of their corresponding MFCs. As demonstrated in Fig. 6a1, 6a2, Device A exhibits a modulation period of 14.8 ms, giving rise to distinctly separated comb clusters centered around harmonics, with an associated \({\gamma }_{{ex}}\) of 67.214 Hz. This relatively low energy exchange rate is associated with a weaker coupling coefficient \({\alpha }_{A}\) and small vibration amplitude \({A}_{2}\). Upon increasing the driving amplitude, the modulation period of Device A shortens to 2.99 ms due to a substantial rise in the energy exchange rate to 334.3 Hz, as illustrated in Fig. 6b1, b2. A comparison between the spectral amplitudes in Fig. 6a3–a5 and 6b3–b5 reveals that the enhanced torsional vibration amplitude \({A}_{2}\) results in frequency combs with wider spacing and an expanded spectral range, confirming the key role of giant energy exchange rate in shaping MFC spectra.

Temporal domain of the weakly coupled resonator Device A under small driving amplitude (a1) and larger driving amplitude (b1). Corresponding discrete and narrow MFCs with small energy exchange rate (a2) and with slightly broader comb spacing and spectral range (b2). The enlarged MFCs spectrum on the first three harmonics under small driving amplitude (a3–a5) and larger driving amplitude (b3–b5). Temporal domain of the strongly coupled resonator Device B under small driving amplitude (c1) and larger driving amplitude (d1). Corresponding supercontinuum MFCs with giant energy exchange rate (c2) and with even more elevated energy exchange rate (d2)

The limited coupling coefficient \({\alpha }_{A}\) of Device A constraints its comb spectral range, preventing higher-order harmonic components from overlapping with each other to form supercontinuum MFCs. In contrary, Device B, designed with a giant coupling coefficient \({\alpha }_{B}\), exhibits a significantly shorter modulation period of 0.587 ms, corresponding to an energy exchange rate of 1699.7 Hz, as illustrated in Fig. 6c1, c2. This elevated exchange rate facilitates the spectral overlap of higher-order harmonics, and with precise alignment of the excitation frequency to match the comb lines, supercontinuum MFCs spanning nearly a decade can be achieved. Further increasing the driving amplitude results in a larger torsional vibration amplitude and an even higher energy exchange rate \({\gamma }_{{ex}}\), leading to a further reduced modulation time of 0.163 ms and increased comb spacing of 6131.2 Hz, as shown in Fig. 6d1, d2. These results collectively demonstrate that by appropriately controlling the coupling coefficient and the vibration amplitude of the resonator, the energy exchange rate can be effectively tuned over a wide range, thereby enabling precise modulation and formation of the spectral characteristics of supercontinuum MFCs.

In general, a higher energy exchange rate facilitates stronger interactions between the coupled modes, which is favorable for generating stable and broadband MFCs. If the comb spacing is too small, comb lines may interfere with each other, leading to signal crosstalk and a reduced signal-to-noise ratio. For precision timing, MFCs with larger comb spacing and improved stability can serve as highly accurate on-chip frequency references and reduce phase noise in timing systems. Similarly, for frequency synthesis, the tunable comb spacing and broad spectral range provides flexible access to multiple frequency channels, which is advantageous for generating harmonics or intermediate frequencies. Therefore, both quantities are meaningful indicators for evaluating the overall performance of MFCs. Figure 7 summarizes and compares these two parameters across various reported MFCs implementations40,41,42, including our work. Notably, our Device B, enabled by the coupling-enhanced anchor design, exhibits an order-of-magnitude improvement in both normalized energy transfer rate and MFCs spectral range, leading to the supercontinuum MFCs.

Discussion

In summary, we have demonstrated a systematic method for enhancing the energy exchange rate in internally coupled MEMS resonators through targeted structural design and dynamics study. Two devices with distinct coupling coefficients are fabricated and characterized via both experiments and numerical simulations. A theoretical model describing the proportional relationship between the energy exchange rate and key resonator parameters was developed. By sweeping the driving frequency, the positive correlation between the energy exchange rate and the torsional amplitude is verified and the proportional coefficient \(C\) is quantitatively determined through numerical fitting. Notably, the enhanced coupling coefficient in Device B facilitated broader comb spacings and a significantly expanded spectral range of MFCs, leading to a supercontinuum MFC spanning over a decade in bandwidth. These findings provide a design-oriented strategy for dynamic spectral control of MFCs, with promising implications for precision timing, frequency synthesis, and on-chip signal processing.

Materials and methods

Resonator fabrication

The MEMS resonator is fabricated using a conventional silicon-on-insulator (SOI) micromachining process, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S1. The fabrication begins with backside photolithography followed by etching to remove the 350-μm-thick high-resistivity silicon handle layer. Subsequently, the 25-μm-thick phosphorus-doped device layer is coated with a metal stack consisting of 15 nm of nickel and 200 nm of gold. Frontside patterning of the device silicon is carried out through standard photolithography, and structures are defined by deep reactive ion etching. Finally, the buried oxide layer is released using vapor-phase hydrofluoric acid, and the device undergoes post-release cleaning.

Experimental setup

The experimental setup diagram is demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. S2, including a temperature-stabilized vacuum chamber, which maintains room temperature and a vacuum level of ~0.1 Pa. A RIGOL DP832 DC power supply is used to provide a constant bias voltage, while a Zurich Instruments MFLI lock-in amplifier supplies the AC driving signal. The DC and AC voltages are superimposed using a T-bias configuration and applied to the same side of the comb-drive electrode. A 2-V DC bias is applied to the device, where mechanical motion modulates the current via the piezoresistive effect. The resulting signal is amplified using a transimpedance amplifier for lock-in detection. This voltage signal is fed into the voltage input of the lock-in amplifier for signal acquisition. All frequency sweep measurements are performed via computer control using the Zurich MFLI interface. Optical measurements are also performed using a Polytec MSV-600 laser Doppler vibrometer, which offers a higher signal-to-noise ratio and a noise floor as low as 100 fm, allowing accurate detection of the torsional modes.

Parameter extraction

The resonator parameters were extracted through a combination of experimental measurement and numerical modeling. First, a low-amplitude linear frequency sweep was conducted to determine the resonance frequency and quality factor of each mode (shown in Supplementary Fig. S3). Based on the geometric dimensions of the proof mass and supporting beams, the effective modal mass, linear stiffness, and cubic nonlinear stiffness for both flexural and torsional modes were estimated using analytical expressions43,44. The coupled-mode equations governing the 1:3 internal resonance behavior were then solved using the method of multiple scales to derive amplitude-frequency response relations45,46. Numerical simulations of the frequency response were performed via MATLAB using ODE solvers, allowing us to generate theoretical sweep curves under various parameter sets. By systematically comparing these simulated curves with experimentally measured frequency responses, we were able to fit and extract key parameters, including the modal coupling coefficient and the torsional stiffness.

References

Salvia, J. C., Melamud, R., Chandorkar, S. A., Lord, S. F. & Kenny, T. W. Real-time temperature compensation of MEMS oscillators using an integrated micro-oven and a phase-locked loop. J. Microelectromechanical Syst. 19, 192–201 (2010).

Heidarpour Roshan, M. et al. A MEMS-assisted temperature sensor with 20- μK resolution, conversion rate of 200 S/s, and FOM of 0.04 pJK2. IEEE J. Solid State Circuits 52, 185–197 (2017).

Li, L., Zhang, Q., Wang, W. & Han, J. Nonlinear coupled vibration of electrostatically actuated clamped–clamped microbeams under higher-order modes excitation. Nonlinear Dyn. 90, 1593–1606 (2017).

Zhang, Z. et al. Virtually coupled resonators with modal dominance for improved sensitivity and bandwidth. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 11, 57 (2025).

Yan, Y., Dong, X., Huang, L., Moskovtsev, K. & Chan, H. B. Energy transfer into period-tripled states in coupled electromechanical modes at internal resonance. Phys. Rev. X 12, 031003 (2022).

Wang, X., Huan, R., Zhu, W., Pu, D. & Wei, X. Frequency locking in the internal resonance of two electrostatically coupled micro-resonators with frequency ratio 1:3. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 146, 106981 (2021).

Czaplewski, D. A., Strachan, S., Shoshani, O., Shaw, S. W. & López, D. Bifurcation diagram and dynamic response of a MEMS resonator with a 1:3 internal resonance. Appl. Phys. Lett. 114, 254104 (2019).

Pandit, M. et al. Utilizing energy localization in weakly coupled nonlinear resonators for sensing applications. J. Microelectromechanical Syst. 28, 182–188 (2019).

Zhang, H., Huang, J., Yuan, W. & Chang, H. A high-sensitivity micromechanical electrometer based on mode localization of two degree-of-freedom weakly coupled resonators. J. Microelectromechanical Syst. 25, 937–946 (2016).

Li, H., Zhang, Z., Zu, L., Hao, Y. & Chang, H. Micromechanical mode-localized electric current sensor. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 8, 42 (2022).

Chen, T.-Y. & Li, W.-C. True random number generation in nonlinear internal-resonating MEMS resonators. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 45, 116–119 (2024).

Defoort, M., Rufer, L., Fesquet, L. & Basrour, S. A dynamical approach to generate chaos in a micromechanical resonator. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 7, 17 (2021).

Hussein, H. M. E., Kim, S., Rinaldi, M., Alù, A. & Cassella, C. Passive frequency comb generation at radiofrequency for ranging applications. Nat. Commun. 15, 2844 (2024).

Wu, H. et al. Precise underwater distance measurement by dual acoustic frequency combs. Annal. der Physik 531, 1900283 (2019).

Cao, L. S., Qi, D. X., Peng, R. W., Wang, M. & Schmelcher, P. Phononic frequency combs through nonlinear resonances. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 075505 (2014).

Ganesan, A., Do, C. & Seshia, A. Phononic Frequency Comb via Intrinsic Three-Wave Mixing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 033903 (2017).

Ganesan, A. & Seshia, A. Coexistence of multiple multimode nonlinear mixing regimes in a microelectromechanical device. Appl. Phys. Lett. 112, 084102 (2018).

Ganesan, A., Do, C. & Seshia, A. Excitation of coupled phononic frequency combs via two-mode parametric three-wave mixing. Phys. Rev. B 97, 014302 (2018).

Czaplewski, D. A. et al. Bifurcation generated mechanical frequency comb. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 244302 (2018).

Eriksson, A. M., Shoshani, O., López, D., Shaw, S. W. & Czaplewski, D. A. Controllable branching of robust response patterns in nonlinear mechanical resonators. Nat. Commun. 14, 161 (2023).

Adarsh Ganesan, A. S. Hysteresis in phononic frequency combs. In European Frequency and Time Forum (EFTF) (IEEE, 2018), pp. 6–9.

Han, X. et al. Superconducting cavity electromechanics: the realization of an acoustic frequency comb at microwave frequencies. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 107701 (2022).

Singh, R. et al. Giant tunable mechanical nonlinearity in graphene-silicon nitride hybrid resonator. Nano Lett. 20, 4659–4666 (2020).

Gobat, G., Zega, V., Fedeli, P., Touzé, C. & Frangi, A. Frequency combs in a MEMS resonator featuring 1:2 internal resonance: ab initio reduced order modelling and experimental validation. Nonlinear Dyn. 111, 2991–3017 (2022).

Wu, J. et al. Self-injection locked and phase offset-free micromechanical frequency combs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 107201 (2025).

Rahmanian, S. et al. NEMS generated electromechanical frequency combs. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 11, 8 (2025).

Kubena, R. L., Wall, W. S., Koehl, J. & Joyce, R. J. Phononic comb generation in high-Q quartz resonators. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116, 053501 (2020).

Mahboob, I., Dupuy, R., Nishiguchi, K., Fujiwara, A. & Yamaguchi, H. Hopf and period-doubling bifurcations in an electromechanical resonator. Appl. Phys. Lett. 109, 073101 (2016).

Ochs, J. S. et al. Frequency comb from a single driven nonlinear nanomechanical mode. Phys. Rev. X 12, 041019 (2022).

Okamoto, H. et al. Coherent phonon manipulation in coupled mechanical resonators. Nat. Phys. 9, 480–484 (2013).

Chen, C., Zanette, D. H., Czaplewski, D. A., Shaw, S. & López, D. Direct observation of coherent energy transfer in nonlinear micromechanical oscillators. Nat. Commun. 8, 15523 (2017).

Zhang, H. et al. Coherent energy transfer in coupled nonlinear microelectromechanical resonators. Nat. Commun. 16, 3864 (2025).

Park, M. & Ansari, A. Formation, evolution, and tuning of frequency combs in microelectromechanical resonators. J. Microelectromechanical Syst. 28, 429–431 (2019).

Zhou, X. et al. Dynamic modulation of modal coupling in microelectromechanical gyroscopic ring resonators. Nat. Commun. 10, 4980 (2019).

Wu, J. et al. Widely-tunable MEMS phononic frequency combs by multistage bifurcations under a single-tone excitation. J. Microelectromechanical Syst. 33, 384–394 (2024).

Wu, J. et al. Limit cycle convergence leads to period-doubling and cyclic-fold bifurcation in internal resonance-induced mechanical frequency combs. Nonlinear Dyn. 113, 19289–19310 (2025).

Shoshani, O. & Shaw, S. W. Resonant modal interactions in micro/nano-mechanical structures. Nonlinear Dyn. 104, 1801–1828 (2021).

Asadi, K., Yeom, J. & Cho, H. Strong internal resonance in a nonlinear, asymmetric microbeam resonator. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 7, 9 (2021).

Gil-Santos, E., Ramos, D., Pini, V., Calleja, M. & Tamayo, J. Exponential tuning of the coupling constant of coupled microcantilevers by modifying their separation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 123108 (2011).

Sun, J. et al. Generation and evolution of phononic frequency combs via coherent energy transfer between mechanical modes. Phys. Rev. Appl. 19, 014031 (2023).

Xi, J. et al. Frequency-comb-like behavior in a resonant MEMS accelerometer subject to blue sideband excitation. In 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Inertial Sensors and Systems (INERTIAL) 1-4 (IEEE, 2024).

Zhao, Z., Li, Y., Zhang, W., Luo, W. & Liu, D. Acoustic frequency comb generation on a composite diamond/silicon microcantilever in ambient air. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 11, 12 (2025).

Villa, M. M. & Paul, M. R. Stochastic dynamics of micron-scale doubly clamped beams in a viscous fluid. Phys. Rev. E 79, 056314 (2009).

Greywall, D. S. Sensitive magnetometer incorporating a high-Q nonlinear mechanical resonator. Meas. Sci. Technol. 16, 2473–2482 (2005).

Shoshani, O., Strachan, S., Czaplewski, D., Lopez, D. & Shaw, S. W. Extraordinary frequency stabilization by resonant nonlinear mode coupling. Phys. Rev. Appl. 22, 054055 (2024).

Li, L. et al. Modal coupled vibration behavior of piezoelectric L-shaped resonator induced by added mass. Nonlinear Dyn. 109, 2297–2318 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 125B2033, No. 12427801 and No. 12372016) and the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2023YFF0723000).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Experiments were performed by J.W. Theoretical analysis was performed by J.W. and P.S. The first draft of the manuscript was written by J.W. S.Z. helped in writing. L.S. and W.Z. supervised the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, J., Zang, S., Song, P. et al. Giant energy exchange rate in mode-coupled resonators enables supercontinuum mechanical frequency combs. Microsyst Nanoeng 12, 56 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-026-01168-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-026-01168-6