Abstract

Metastasis following surgical resection is a leading cause of mortality in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition is thought to play an important role in metastasis, although its clinical relevance in metastasis remains uncertain. We evaluated a panel of RNA in-situ hybridization probes for epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related genes expressed in circulating tumor cells. We assessed the predictive value of this panel for metastasis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and, to determine if the phenotype is generalizable between cancers, in colonic adenocarcinoma. One hundred fifty-eight pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas and 205 colonic adenocarcinomas were classified as epithelial or quasimesenchymal phenotype using dual colorimetric RNA-in-situ hybridization. SMAD4 expression on pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas was assessed by immunohistochemistry. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas with quasimesenchymal phenotype had a significantly shorter disease-specific survival (P = 0.031) and metastasis-free survival (P = 0.0001) than those with an epithelial phenotype. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas with SMAD4 loss also had lower disease-specific survival (P = 0.041) and metastasis-free survival (P = 0.001) than those with intact SMAD4. However, the quasimesenchymal phenotype proved a more robust predictor of metastases—area under the curve for quasimesenchymal = 0.8; SMAD4 = 0.6. The quasimesenchymal phenotype also predicted metastasis-free survival (P = 0.004) in colonic adenocarcinoma. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition defined two phenotypes with distinct metastatic capabilities—epithelial phenotype tumors with predominantly organ-confined disease and quasimesenchymal phenotype with high risk of metastatic disease in two epithelial malignancies. Collectively, this work validates the relevance of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human gastrointestinal tumors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is an aggressive malignancy and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States. Survival remains poor despite advances in surgical techniques and chemotherapy due to the aggressive biology of these tumors. Metastasis is a major driver behind the lethal nature of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, but the mechanisms involved in the metastatic cascade have been difficult to unravel due to the complexity of the process.

Early stage and apparently resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas frequently metastasize, with the most common sites of disease being the liver and lung. Therefore, a predictor of metastasis is important for optimizing therapeutic interventions. Among the genetic events associated with the progression of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma alterations in KRAS, INK4a, ARF (CDKN2A), TP53 and SMAD4, only loss of SMAD4 has shown prognostic and predictive value in identifying patterns of metastasis [1, 2]. Previous work has identified distinct patterns of progressive disease in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma with 70% of patients with extensive metastatic disease and 30% with locally aggressive disease; SMAD4 could distinguish between these two disease phenotypes [2].

Epithelial- mesenchymal transition is a phenomenon by which terminally differentiated epithelial cells acquire a mesenchymal phenotype [3, 4]. During this process, epithelial cells lose polarity, cell-cell junctions, and cytoskeletal components and acquire enhanced migratory capacity, elevated resistance to apoptosis and secrete proteases required to breakdown extracellular matrix [5]. Although studies across multiple cancer models suggest epithelial-mesenchymal transition as an important mediator of tumor dissemination, its role as a mechanism for systemic dissemination remains controversial.

Gene expression analysis can categorize pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas into classical, epithelial and quasimesenchymal subtypes with linkage to resistance to therapy and survival, but differences in metastasis was not shown [6]. In our prior work, circulating tumor cells in genetically engineered mouse models and patient samples showed epithelial-mesenchymal transition [7].

A more recent analysis of RNA expression data using computational virtual microdissection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma indicates that the quasimesenchymal signature may represent an artifact, one caused by stromal contamination [8]. An alternate model suggests that the epithelial-mesenchymal transition program is dispensable for metastasis [9, 10]. Deletion of epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related transcription factors such as Twist and Snail did not impair metastatic ability [9, 10], although deletion of Zeb1 demonstrated impaired metastases [11]. In a murine mammary tumor model, Fischer et. al., using green fluorescent protein as a proxy for the epithelial-mesenchymal transition transcription factors FSP1 and vimentin, also showed that most cells in a metastatic lesion did not undergo epithelial-mesenchymal transition [10].

Most studies exploring the role of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in tumor dissemination use either bulk sequencing of epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related genes, a technique that cannot elude stromal contamination, single-marker immunohistochemistry or knockout of specific genes in murine models. These approaches reflect neither the dynamic and heterogeneous nature of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition process nor do they account for the redundancies in the program. We overcome some of these challenges by evaluating a dual colorimetric RNA in-situ hybridization [12] assay that consists of a cocktail of epithelial and mesenchymal markers to assess epithelial-mesenchymal transition status in primary pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and colonic adenocarcinoma. Collectively, our data suggests that epithelial-mesenchymal transition remains an important mechanism of metastases in both pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and colonic adenocarcinomas and the dual colorimetric RNA-in-situ hybridization assay provides a quantitative overview of epithelial-mesenchymal transition status in primary tumors, which can be clinically leveraged to predict systemic metastases.

Materials and methods

We evaluated 158 patients who were diagnosed with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and resected with curative intent between March 1999 and December 2013. The surgical procedures included pancreaticoduodenectomy (126), distal pancreatectomy (31) and total pancreatectomy (1). One hundred nineteen pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients received adjuvant therapy and twenty-two neo-adjuvant therapy. We also evaluated 10 pancreatic intraepithelial lesions within this cohort of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas.

We also evaluated 205 consecutive patients with colonic adenocarcinoma resected between 2008 and 2013. The cohort included 119 patients (57%) that did not receive chemotherapy.

A multidisciplinary team evaluated all patients. We utilized a dual-colorimetric and quantifiable RNA-in-situ hybridization assay to examine the expression of seven epithelial and three mesenchymal transcripts on formalin fixed paraffin embedded tissue. The tumor staging was performed as per the 7th Edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer.

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: loco-regional disease versus systemic metastasis

We categorize our cohort into: (1) systemic metastasis- disease with distant metastasis including the liver, lung or bone, among others, and (2) loco-regional disease, defined as that confined to the pancreas and local recurrence involving the pancreatic bed and tissue around the superior mesenteric artery. In our study, we did not classify peritoneal carcinomatosis as distant metastasis. The mechanism of peritoneal spread in gastrointestinal malignancies is due to spillage and serosal invasion rather than through hematogenous spread [13,14,15]. Since the design of the biomarker panel was based on genes enriched in circulating tumor cells, it is expected to predict metastases resulting from hematogenous spread.

RNA in-situ hybridization

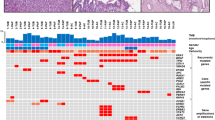

We used RNA-in-situ hybridization to quantify epithelial and mesenchymal signature markers on a dual colorimetric platform as per protocol (ViewRNA in-situ hybridization, Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). The ViewRNA probes target epithelial [CDH1 (1:50), EPCAM (1:50), KRT5 (1:100), KRT7 (1:100), KRT8 (1:100), KRT18 (1:100), KRT19 (1:100); all type 1 probes] and mesenchymal transcripts [FN1 (1:50), CDH2 (1:50), SERPINE1 (1:50); all type 6 probes] with the former in red and the latter in blue. Normal ductal epithelium served as an internal positive control for expression of epithelial markers whereas the tumor stroma serves as a positive control for mesenchymal markers. The epithelial markers were scored relative to the intensity of staining in the normal ductal epithelium (Table 1, Fig. 1). Samples that lacked positive controls for epithelial and/or mesenchymal markers were excluded from the analyses as these sections had poor RNA preservation. The expression of mesenchymal markers in the tumor stroma was heterogeneous in some tumors. This is likely a consequence of heterogeneity in expression of stromal markers during evolution of myofibroblasts [16, 17].

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Epithelial predominant (epithelial phenotype) pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (a and b). Hematoxylin and eosin stained section (a) and corresponding in situ hybridization stain (b) showing tumor cells exclusively expressing high-level epithelial markers. Epithelial loss (quasimesenchymal phenotype) c and d The tumor cells show loss of expression of epithelial markers (arrow) (d). Note the high expression of mesenchymal markers in the stromal compartment. Epithelial loss and mesenchymal gain (quasimesenchymal phenotype) (e and f). Note the tumor cells (arrow) show both red (epithelial markers) and blue (mesenchymal markers) signal. a, c, and e—hematoxylin and eosin stain. b, d, and f—in situ hybridization stain for epithelial and mesenchymal markers

SMAD4 status

SMAD4 status was determined using Rabbit polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Catalog number sc7966) at 1:25 concentration per standard immunohistochemistry methods. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas were considered to have absent SMAD4 expression if neoplastic cells lacked nuclear labeling and adjacent non-neoplastic cells (e.g., stromal cells, islets and lymphocytes) were positive, an internal control. The presence of nuclear SMAD4 expression in any core was accepted as intact SMAD4 expression. We could not evaluate SMAD4 expression in 21 (13%) patients, primarily because of the lack of a positive internal control and non-specific background reactivity.

Two pathologists, blinded to the clinical outcome, evaluated the immunohistochemical and RNA-in-situ hybridization slides.

Statistical analysis

Disease-specific survival and metastasis-free survival probability curves were constructed using the Kaplan-Meier method; log-rank test was used to evaluate the statistical significance of differences. We used a proportional hazards regression model to correct for the variables that achieved significance on a univariate analysis. Chi square test was used to compare categorical data and independent t-test for comparing continuous versus categorical data. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS- version 21. We used a two-sided significance level of 0.05 for all analyses.

Results

Baseline pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma characteristics are summarized on Supplementary table 1. Follow up data was available on all patients and ranged from 3 to 127 months.

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

Validation of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition RNA-in-situ hybridization for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma was performed on two human patients derived pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma xenografts with known epithelial and quasimesenchymal status based on RNA-sequencing gene expression signatures (Supplementary figure 1). PDAC6, a xenograft from a known epithelial cell line was strongly positive for the epithelial and negative for mesenchymal signature. Notably, intratumoral stroma was negative for mesenchymal markers, demonstrating the specificity of the mesenchymal RNA-in-situ hybridization markers to human transcripts. In contrast, PDAC3, a quasimesenchymal cell line had heterogeneous expression of epithelial and mesenchymal markers. Notably, while the epithelial cell line showed near exclusive expression of epithelial markers, the expression in the quasimesenchymal cell line was more heterogeneous, with areas that were epithelial positive, mesenchymal positive, epithelial and mesenchymal positive (data not shown), and epithelial low (data not shown). This mixture of epithelial and mesenchymal markers is consistent with RNA-sequencing expression in these cell lines; RNA-in-situ hybridization resolves the inherent heterogeneity of quasimesenchymal pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas. Given these findings, a classification scheme was developed: epithelial loss or mesenchymal gain—quasimesenchymal tumor; epithelial predominant—epithelial tumor (Table 1).

Patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma were classified into two groups based on RNA—in-situ hybridization (Fig. 1): (1) epithelial phenotype 70 patients (44%), and (2) quasimesenchymal phenotype 88 patients (56%) (Table 2). Among the quasimesenchymal tumors, 16 patients (18%) showed exclusively epithelial-loss, while 72 cases (82%) showed gain of mesenchymal markers, most which also showed loss of epithelial markers (55 cases, 63%). Analysis of clinical parameters revealed a significant association of the quasimesenchymal phenotype with systemic metastasis (Hazard ratio 10, 95% confidence interval (5-25); P = 0.0001) (Table 3b and Fig. 2). Sixty-four percent of patients with the quasimesenchymal phenotype developed systemic metastasis compared to 11% with epithelial phenotype (P = 0.0001). In addition, a gain of mesenchymal signature (with or without epithelial loss) also predicted metastasis-free and disease-specific survival (Supplementary figure 2). The median metastasis-free survival for the epithelial phenotype was 18 months, whereas patients with a quasimesenchymal phenotype had a median metastasis-free survival of 8 months. Collectively, this suggests that epithelial and quasimesenchymal pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma phenotypes show distinct modes of tumor dissemination.

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition RNA-in-situ hybridization and SMAD4 status predict survival and metastasis. a Metastasis-free survival of epithelial and quasimesenchymal phenotype pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. b Metastasis-free survival of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma—SMAD4 loss versus SMAD4 intact. c Disease-specific survival of epithelial and quasimesenchymal phenotype pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. d Disease-specific survival of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma—SMAD4 loss versus SMAD4 intact. P is by log rank test

Poorly differentiated tumors were more likely to be quasimesenchymal than the epithelial cohort: 37% vs. 19%, respectively (P = 0.016). However, tumor grade alone did not predict metastasis-free survival on a univariate analysis.

The predictive value of epithelial-mesenchymal transition RNA-in-situ hybridization for metastasis-free survival persisted on a Cox proportional hazards model after adjusting for variables that attained significance on a univariate model (P = 0.0001, Hazard Ratio = 10) (Tables 3a and 3b).

SMAD4 immunohistochemistry

In keeping with prior literature, SMAD4 loss was also significantly associated with adverse metastasis-free survival (Table 3b, Hazard ratio 3, 95% Confidence interval (2-5); P = 0.001), and this association persisted in a Cox proportional hazards model after adjusting for variables that attained significance on a univariate model. The median metastasis-free survival for the cohort with SMAD4 loss was 8 months and that for intact SMAD4 expression 10 months.

Comparison of quasimesenchymal phenotype with SMAD4

The quasimesenchymal phenotype proved a more robust means of predicting systemic metastasis—area under the curve for quasimesenchymal = 0.8, SMAD4 = 0.6 (Supplementary figure 3). The epithelial phenotype showed a higher negative predictive value for metastasis than intact SMAD4 (negative predictive value—epithelial Vs. SMAD4 intact = 89% versus 68%). The quasimesenchymal phenotype had a greater positive predictive value for metastasis (positive predictive value—quasimesenchymal versus SMAD4 loss = 64 and 58%, respectively) (Supplementary table 2).

Interestingly, there was no correlation between the quasimesenchymal phenotype and SMAD4 status, although both parameters independently predicted metastasis (Kappa = 0.086; P = 0.287).

Disease-specific survival: epithelial/quasimesenchymal phenotype versus SMAD4

On a multivariate model, the quasimesenchymal phenotype and tumors with loss of SMAD4 showed a significantly lower disease-specific survival [Hazard ratio 2, (P = 0.048) and 2 (P = 0.025), respectively (Table 3b).

Epithelial/quasimesenchymal phenotype in pancreatic intra-epithelial neoplasia

Ten pancreatic intra-epithelial neoplasia lesions were evaluated for epithelial and mesenchymal markers. The quasimesenchymal phenotype was exclusively noted in pancreatic intra-epithelial neoplasia grade 2 and 3 lesions: 3 of 5 pancreatic intra-epithelial neoplasia grade 2 and 1 of 3 grade 3 lesions showed a quasimesenchymal phenotype. Notably, none of the patients with epithelial phenotype pancreatic intra-epithelial neoplasia and two of four patients with quasimesenchymal pancreatic intra-epithelial neoplasia developed systemic metastasis.

Response to chemotherapy

On a multivariate model, patients who received chemotherapy had a significantly longer metastasis-free survival than those who did not [P = 0.001; HR = 4; 95% CI (2–9)] (Table 3b). Both the epithelial and quasimesenchymal cohorts who received chemotherapy had an improved metastasis-free survival compared to untreated patients in their class: epithelial—with versus without chemotherapy (P = 0.007), and quasimesenchymal—with versus without chemotherapy (P = 0.005) (Fig. 3). Among the patients that did not receive chemotherapy, epithelial tumors had longer metastasis-free survival compared to quasimesenchymal tumors (P = 0.001), an observation that suggests that the quasimesenchymal phenotype predicts poor metastasis-free survival independent of chemotherapy.

Quasimesenchymal signature predicts poor metastasis-free survival independent of chemotherapy. Kaplan–Meier curves of epithelial and quasimesenchymal tumor with and without chemotherapy. Note that chemotherapy naïve epithelial tumors showed a superior metastasis-free survival when compared to chemotherapy naïve quasimesenchymal tumors (P = 0.0001)

There was no difference in disease-specific survival in either the epithelial (P = 0.165) or quasimesenchymal (P = 0.885) cohorts between the patients who underwent chemotherapy and those that did not.

Neo-adjuvant therapy

A greater proportion of patients that received neo-adjuvant chemotherapy had an epithelial (59%, 13/22) than quasimesenchymal phenotype (41%, 9/22). Conversely, a lesser proportion of patients that did not receive neo-adjuvant therapy showed an epithelial phenotype: epithelial = 42%, 57/136 versus quasimesenchymal phenotype 58%, 79/136. A similar correlation emerged with SMAD4. In the neo-adjuvant cohort 18% (4/22) of patients showed loss of SMAD4 while 82% (18/22) showed intact SMAD4. In patients that did not receive neo-adjuvant therapy, 40% (46/115) of patients showed loss of SMAD4 and 60% (69/115) showed intact SMAD4 expression. The data suggests that neo-adjuvant therapy did not trigger quasimesenchymal phenotype or SMAD4 deficient tumors. Additionally, SMAD4 loss and epithelial-mesenchymal transition predicted metastasis-free survival and disease-specific survival in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients that did not receive chemotherapy (see supplementary figure 4).

Validation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition RNA-in-situ hybridization panel in colonic adenocarcinoma cohort

The patient characteristics are summarized in Supplementary table 4. Like pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma epithelial-mesenchymal transition RNA-in-situ hybridization panel identified two phenotypes with distinct metastatic capabilities (Fig. 4): 14% of epithelial phenotype patients developed systemic metastasis as compared to 37% of quasimesenchymal tumors (metastasis-free survival, P = 0.004). On a multivariate model, the quasimesenchymal phenotype showed a significant association with metastasis after correcting for tumor stage and chemotherapy [metastasis-free survival: P = 0.015; Hazard ratio = 2.280; Supplementary figure 5B].

Colonic adenocarcinoma. Epithelial predominant (epithelial phenotype) colonic adenocarcinoma (a and b). Hematoxylin and eosin stained section (a) and corresponding RNA in situ hybridization stain (b) showing tumor cells exclusively expressing epithelial markers. Mesenchymal gain (quasimesenchymal phenotype) (c and d). The tumor cells show both epithelial markers (*) and mesenchymal markers (arrow) (d). The mesenchymal markers were often expressed at the periphery of tumor islands. Colonic adenocarcinoma with near-exclusive mesenchymal phenotype (e and f). Although most of the tumor shows loss of epithelial and gain of mesenchymal markers, rare foci of tumor (arrow) showed only paucity of epithelial markers. a, c, and e—hematoxylin and eosin stain. b, d, and f—in situ hybridization stain for epithelial and mesenchymal markers

In the colonic adenocarcinoma cohort 56 patients received folinic acid, fluorouracil and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX regimen), 9 patients fluorouracil, 9 patients capecitabine, 8 patients folinic acid, fluorouracil, irinotecan, oxaliplatin (FOLFIRINOX regimen); data was not available on 9 patients.

Among patients treated with chemotherapy, epithelial phenotype tumors had a longer metastasis-free survival compared to the quasimesenchymal phenotype (P = 0.038; Supplementary figure 5D). Among patients that did not receive chemotherapy, there was no difference in metastasis-free survival among the epithelial and quasimesenchymal phenotypes (P = 0.478; Supplementary figure 5E). The limitation of this cohort is that there were fewer tumor-related deaths (n = 15), particularly in the cohort that was not treated with chemotherapy. Consequently, the lack of statistically significant differences in disease-specific survival (epithelial versus quasimesenchymal status, tumor stage and chemotherapy response) and metastasis-free survival in the chemotherapy naïve cohort may be attributable to the paucity of events (Supplementary figure 5C).

Discussion

The evidence for epithelial-mesenchymal transition as a driver of the metastatic cascade is well defined in genetically engineered models and in vitro studies [6, 18]. In cell line and mouse models, epithelial-mesenchymal transition has been shown to be important for active migration, vascular invasion and the acquisition of a stem cell phenotype [18,19,20]. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition has also been shown to confer resistance to chemotherapy and targeted therapies in human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cell lines [6]. However, despite a wealth of scientific work, the clinical world continues to debate the relevance of epithelial-mesenchymal transition, which we believe to be due to the paucity of robust clinical assays.

The RNA-in-situ hybridization panel, a surrogate marker of epithelial-mesenchymal transition, distinguished two classes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: (1) the epithelial phenotype correlated with organ-confined disease, (2) the quasimesenchymal phenotype, associated with high risk for systemic disease. In the pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cohort, both quasimesenchymal phenotype and SMAD4 loss were independent predictors of metastasis-free and disease-specific survival in a multivariate Cox regression model. Notably, the quasimesenchymal phenotype was not overrepresented in the neo-adjuvant therapy cohort, and the predictive value of the quasimesenchymal phenotype was also noted in patients that did not receive pre-operative chemotherapy (Supplementary figure 4). However, compared to SMAD4 status, the quasimesenchymal phenotype proved to be a far more robust predictor of metastasis. The quasimesenchymal phenotype also predicted metastasis-free survival in colon carcinoma. There were no tumors with a complete mesenchymal phenotype, an observation consistent with our RNA-sequencing of patient derived cell line data and circulating tumor cells [6, 7].

The most frequently used strategy to evaluate epithelial-mesenchymal transition in patient samples has been to assess for the loss of epithelial markers or acquisition of mesenchymal proteins such as vimentin, fibronectin, FSP-1 and N-cadherin. Other investigators have looked at transcriptional factors implicated in epithelial-mesenchymal transition including Snail, Slug, ZEB1, Twist and LEF-1[21]. By evaluating individual proteins, these studies fail to capture the complexity of epithelial-mesenchymal transition, explaining some of the inconsistencies across different studies. Javle and co-workers evaluated 34 resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas using antibodies to vimentin, fibronectin, E-cadherin, and phosphorylated Erk and showed that patients with an epithelial-mesenchymal transition phenotype showed poor survival [22]. In a study of 174 pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas, a multivariate analysis correlated epithelial-mesenchymal transition with aggressive tumor behavior [23]. In a follow-up paper, these authors demonstrated a relationship between a mesenchymal phenotype and loss of SMAD4 [23, 24]. Conversely, in a study of 68 pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas, Twist, Slug, and N-cadherin expression were not associated with patient outcome or duration of survival [25].

We used an assay originally developed to assess epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human breast circulating tumor cells, the cells thought to initiate the metastatic cascade [26]. In this study the probes were validated in patient derived pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cell lines. The probes were chosen, in part, because they were not expressed in blood cells, accounting for the excellent specificity. However, a challenge of utilizing epithelial-mesenchymal transition assays in tissue is the high expression of these genes in reactive stromal cells. The superior cellular preservation and the ability to precisely localize intracellular mRNAs allowed for the distinction of epithelial cells from background stromal cells, a level of discrimination not afforded by even meticulously performed microdissection studies. Moreover, many well established mesenchymal genes from cell line models are secreted proteins (SERPINE1 and FN1) that can be easily assessed with RNA-in-situ hybridization but are nearly impossible to resolve with immunohistochemistry. Another factor to consider when evaluating epithelial-mesenchymal transition is the presence of this signature in non-neoplastic but regenerating tissue. A meticulous evaluation of the tissue sections is generally necessary to distinguish malignant cells from regenerating tissue. In summary, the intrinsic cellular heterogeneity of epithelial-mesenchymal transition precludes a clear definition of this phenotype using single marker immunohistochemistry or bulk expression analysis. The simultaneous visualization of both epithelial and mesenchymal signatures in situ overcomes many of these limitations and realizes the potential of epithelial-mesenchymal transition as a clinical biomarker of metastasis.

The relationship between SMAD4 and epithelial-mesenchymal transition is complex and still not fully defined. SMAD4 is a key transcription factor downstream of the transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) signaling cascade, a well-established epithelial-mesenchymal transition signaling pathway. Therefore, the loss of SMAD4 would be predicted to confer a more epithelial phenotype, as has been shown in genetically engineered mouse models [27]. In contrast to this work, in an autopsy study that examined 76 pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas, SMAD4 loss was reported in 22% of locally advanced cases (limited metastatic disease), but in 78% of those with widespread metastatic disease. This data provides additional evidence that SMAD4 function may help constrain metastatic spread in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas. Interestingly, in our pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cohort, there was no correlation between the quasimesenchymal phenotype and SMAD4 status. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and SMAD4 loss may thus represent distinct mechanisms for metastasis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [28, 29]. The predictive value of SMAD4 for metastasis is however inferior to the quasimesenchymal phenotype.

The characterization of molecular subtypes in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma continues to evolve, although the highly variable stromal composition and intrinsic intratumoral phenotypic heterogeneity of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma are inherent barriers. Moffitt and co-workers [8] demonstrated the ability to digitally separate tumor and stromal gene signatures with non-negative matrix factorization, but the routine application of these methods in the clinic remains a challenge. Collectively, these observations support two distinct phenotypes in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma with differing metastatic potential [6]. The RNA-in-situ hybridization assay improves on this work by leveraging the ability of this in-situ hybridization platform to detect the quasimesenchymal phenotype in paraffin embedded tissue.

The epithelial-mesenchymal transition in-situ hybridization panel is a robust predictor of metastasis in two independent cancer models: pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and colonic adenocarcinoma. The epithelial and quasimesenchymal phenotypes could be used to stratify patients entering clinical trials and tailor current therapeutic strategies in patients treated with curative surgery. Additional studies are required to assess the value of this platform to the pre-operative management of patients. Collectively, this work validates the relevance of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human gastrointestinal tumors and brings decades of in vitro and animal work into the clinical realm.

References

Biankin AV, Morey AL, Lee CS, et al. DPC4/Smad4 expression and outcome in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4531–42.

Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Fu B, Yachida S, et al. DPC4 gene status of the primary carcinoma correlates with patterns of failure in patients with pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1806–13.

Tam WL, Weinberg RA. The epigenetics of epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity in cancer. Nat Med. 2013;19:1438–49.

Kalluri R. epithelial-mesenchymal transition: when epithelial cells decide to become mesenchymal-like cells. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1417–9.

Gupta PB, Mani S, Yang J, et al. The evolving portrait of cancer metastasis. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2005;70:291–7.

Collisson EA, Sadanandam A, Olson P, et al. Subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and their differing responses to therapy. Nat Med. 2011;17:500–3.

Ting DT, Wittner BS, Ligorio M, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing identifies extracellular matrix gene expression by pancreatic circulating tumor cells. Cell Rep. 2014;8:1905–18.

Moffitt RA, Marayati R, Flate EL, et al. Virtual microdissection identifies distinct tumor and stroma-specific subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1168–78.

Zheng X, Carstens JL, Kim J, et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is dispensable for metastasis but induces chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2015;527:525–30.

Fischer KR, Durrans A, Lee S, et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is not required for lung metastasis but contributes to chemoresistance. Nature. 2015;527:472–6.

Krebs AM, Mitschke J, Lasierra Losada M, et al. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition-activator Zeb1 is a key factor for cell plasticity and promotes metastasis in pancreatic cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19:518–29.

Fujii S, Mitsunaga S, Yamazaki M, et al. Autophagy is activated in pancreatic cancer cells and correlates with poor patient outcome. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:1813–9.

Sperti C, Pasquali C, Piccoli A, et al. Recurrence after resection for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. World J Surg. 1997;21:195–200.

Kusamura S, Baratti D, Zaffaroni N, et al. Pathophysiology and biology of peritoneal carcinomatosis. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;2:12–8.

Jayne DG. The molecular biology of peritoneal carcinomatosis from gastrointestinal cancer. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2003;32:219–25.

Ohlund D, Handly-Santana A, Biffi G, et al. Distinct populations of inflammatory fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in pancreatic cancer. J Exp Med. 2017;214:579–96.

Yazdani S, Bansal R, Prakash J. Drug targeting to myofibroblasts: implications for fibrosis and cancer. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017;121:101–16.

Rhim AD, Mirek ET, Aiello NM, et al. epithelial-mesenchymal transition and dissemination precede pancreatic tumor formation. Cell. 2012;148:349–61.

Tam WL, Weinberg RA. The epigenetics of epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity in cancer. Nat Med. 2013;19:1438–49.

Kalluri R, Weinberg RA. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1420–8.

Krantz SB, Shields MA, Dangi-Garimella S, et al. Contribution of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cells to pancreatic cancer progression. J Surg Res. 2012;173:105–12.

Javle MM, Gibbs JF, Iwata KK, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (epithelial-mesenchymal transition) and activated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (p-Erk) in surgically resected pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3527–33.

Yamada S, Fuchs BC, Fujii T, et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition predicts prognosis of pancreatic cancer. Surgery. 2013;154:946–54.

Yamada S, Fujii T, Shimoyama Y, et al. SMAD4 expression predicts local spread and treatment failure in resected pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2015;44:660–4.

Cates JM, Byrd RH, Fohn LE, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Pancreas. 2009;38:e1–6.

Yu M, Bardia A, Wittner BS, et al. Circulating breast tumor cells exhibit dynamic changes in epithelial and mesenchymal composition. Science. 2013;339:580–4.

Hezel AF, Kimmelman AC, Stanger BZ, et al. Genetics and biology of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1218–49.

Tarin D, Thompson EW, Newgreen DF. The fallacy of epithelial mesenchymal transition in neoplasia. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5996–6000.

Whittle MC, Izeradjene K, Rani PG, et al. RUNX3 controls a metastatic switch in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cell. 2015;161:1345–60.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NSF PHY-1549535 (D.T.T.), SU2C and Lustgarten Foundation (D.T.T.), and Affymetrix, Inc. (D.T.T., K.S.A, V.D.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

VD, DTT have received research support from Affymetrix. The remaining authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mahadevan, K.K., Arora, K.S., Amzallag, A. et al. Quasimesenchymal phenotype predicts systemic metastasis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol 32, 844–854 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-018-0196-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-018-0196-2

This article is cited by

-

Proteomics in pancreatic cancer

Biomarker Research (2025)

-

The tumour microenvironment in pancreatic cancer — clinical challenges and opportunities

Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology (2020)