Abstract

Approximately one third of people with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) experience a relapse within six months of discontinuing antidepressant medication (ADM), however, reliable predictors of relapse following ADM discontinuation are currently lacking. A putative behavioural predictor is delay discounting, which measures a person’s impatience to receive reward. Previous studies have linked delay discounting to both MDD and reduced serotonergic function, rendering it a plausible candidate predictor. In this multi-site study we measured delay discounting in participants with remitted MDD (N = 97), before and within six months after discontinuation of ADM, and in matched controls without a lifetime history of MDD (N = 54). Using predictive models, we tested whether either baseline discounting, or an early change in discounting following ADM discontinuation, predicted depressive relapse over a six month follow up period. We also tested differences between remitted MDD and control groups in delay discounting at baseline, and associations between discounting and depressive symptoms. We found that the remitted MDD group, compared to the control group, showed significantly higher (p < 0.05; Cohen’s d = 0.34) discounting at baseline. In addition, baseline discounting was positively correlated with depression rating scores (Spearman ρ = 0.24). However, delay discounting did not increase following ADM discontinuation. Neither baseline discounting, nor a change in discounting following ADM discontinuation, predicted subsequent depressive relapse. We conclude that delay discounting is elevated in remitted MDD treated with antidepressant medication. However, delay discounting neither increases following ADM discontinuation, nor does it prospectively predict depressive relapse. These results suggest that delay discounting in Major Depressive Disorder has little relationship with illness trajectory following ADM discontinuation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Depressive disorders are estimated to be among the largest contributors to years lived with disability worldwide [1, 2]. This huge burden of morbidity is largely attributable to the chronic or recurring pattern [3, 4] that often characterizes depression. Furthermore, although many people derive benefit from antidepressant medication, approximately one in three will experience another depressive episode within six months of antidepressant discontinuation [5]. An initially successful treatment is therefore still too often followed by a relapse.

Randomized controlled trials indicate that continual maintenance treatment with antidepressant medication reduces the risk of relapse or recurrence [5,6,7,8]. Nevertheless, maintenance treatment does not completely eliminate the risk of suffering from breakthrough depression while still on treatment, or from further depressive episodes after subsequent discontinuation [9]. Additionally, many people experience unpleasant side effects of antidepressant medication, such as weight gain and sexual dysfunction [10]. Thus, not all individuals who experience a depressive episode benefit equally from continuing medication after achieving remission. There is therefore a pressing clinical need to distinguish those who can safely discontinue antidepressants from those with a higher risk of relapse following discontinuation.

Current clinical guidelines recommend continued treatment for at least six months after obtaining remission from a first episode of depression, and at least two years of treatment after remission for patients deemed to be at high risk of relapse [11, 12]. The risk of relapse is assessed using one or more of different predictors, such as the number of prior episodes [11], physical and psychological comorbidities [11], ethnicity [13], a melancholic subtype [14], anxiety [15], somatic pain [16], and previous response to medication [17]. However, several of these predictors lack robust replication studies to support their relevance (for a review see [18]). Where replications do exist, these sometimes reach conflicting conclusions, for example regarding the effect of the number of previous episodes on future relapse risk [6, 19]. Other predictors are difficult to reliably measure; for example, in clinical practice, previous response to treatment is often unclear [18]. This uncertainty not only calls for continued investigation into existing markers of relapse, but also motivates a search for novel relapse predictors.

In this study we evaluate delay discounting, which is thought to quantify a person’s impatience to receive reward, as a candidate behavioural predictor of depressive relapse following antidepressant discontinuationFootnote 1. Delay discounting can be quickly assessed, by offering participants a series of choices between immediate and delayed rewards of varying magnitude. Conventionally, such choices are used to estimate a parameter termed the ‘discount rate’, which captures how steeply the subjective value of reward decreases as it is delayed. Higher discount rates imply a steeper decrease in reward value with delay, and thereby greater impatience. The behavioral and neural correlates of delay discounting have been extensively studied (see e.g. [20,21,22,23]).

Existing evidence suggests that delay discounting is a plausible candidate marker of depressive relapse following antidepressant discontinuation. Firstly, studies have reported higher delay discount rates amongst people with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) when compared to healthy controls [24,25,26,27]. Notably differences in discounting between depressed participants and non-depressed controls are not found reliably across all studies and comparisons. Some studies find no significant difference [28, 29], while others find differences from healthy controls only amongst sub-groups of depressed participants [24, 27], or only for larger rewards [26]. Nevertheless, a meta-analysis of seven case-control studies supports a conclusion of elevated discounting in MDD, with a small effect size (Hedges g = 0.38) [30]. The greater impatience observed in MDD has been interpreted as resulting from the pessimistic future outlook which is a feature of depression [4, 31,32,33,34,35,36] and as reflecting the loss of evaluative differentiation concerning future outcomes [37].

Secondly, most antidepressant medications are believed to increase serotonin levels, which is thought to be crucial for their therapeutic effect [38, 39], while discounting is also found to be sensitive to serotonergic manipulations. Tryptophan depletion, which lowers brain serotonin levels, induces acute symptomatic relapse in patients with remitted depression [40, 41], and has been found to increase discount rates in healthy participants [42, 43] (though Tanaka et al. did not replicate this effect) [44]. Furthermore, a small study found that discount rates were reduced by acute administration of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor amongst participants with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder [45]. More definitively, rodent studies have demonstrated that stimulating serotonergic neurons in the dorsal raphe, or their projections to medial prefrontal cortex, augments an animal’s willingness to wait for reward [46, 47], while lesioning or blocking serotonergic neurotransmission increases impatience [48,49,50].

In summary, evidence indicates that discounting is increased in MDD, increases following serotonin depletion and decreases following enhancement of serotonin release. Thus, delay discounting is a candidate marker of both serotonergic function and depressive cognition. Based on these findings, our primary hypothesis was that patients with remitted MDD who show higher delay discounting are at increased risk of relapse following antidepressant discontinuation. A secondary hypothesis was that antidepressant discontinuation results in an increase in delay discounting, and that the magnitude of this early increase in discounting predicts subsequent depressive relapse. We tested these hypotheses within the AIDA (Antidepressiva Absetzstudie) study – a two-center, longitudinal, observational study of antidepressant discontinuation [51,52,53]. We also tested how delay discounting is related to depression symptom scores and other psychometric data amongst this sample of patients with remitted depression.

Methods and materials

Participants and study design

Data from the AIDA study has been analysed previously [51,52,53]. However, the delay discounting data reported here have not previously been examined. The dataset consists of: i) participants treated with antidepressant medication (ADM), who decided to discontinue their antidepressant medication independently from study participation, after being diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder, and ii) healthy control (HC) participants matched for age, sex and education to the ADM group. Healthy controls were excluded if there was a lifetime history of DSM IV Axis I or Axis II disorders, with the sole exception of nicotine dependence. Recruitment criteria for the ADM group included: (a) at least one severe [54] or multiple depressive episodes, (b) initiation of antidepressant treatment during the last depressive episode, and (c) achieving stable remission, assessed by a score of less than 7 on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale 17 [55] for 30 days. See [51,52,53] for detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria.

All participants gave informed written consent and received monetary compensation for their time. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the cantonal ethics commission Zurich (BASEC: PB_2016-0.01032; KEK-ZH: 2014-0355) and the ethics commission at the Campus Charité-Mitte (EA 1/142/14), and procedures were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

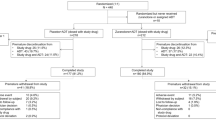

As shown in Fig. 1, participants were assessed and compared at Main Assessment 1 (MA1) to identify features characterising the remitted, medicated state. Next, patients were randomised to either discontinue their medication at MA1 (MA1-D-MA2) or enter a waiting period approximately matched to the length of discontinuation time (group MA1-MA2-D). Patients in the waiting group discontinued their ADM after Main Assessment 2 (MA2). Details of the randomisation procedure are provided in the Supporting Material. After discontinuation, all patients entered a six month follow-up (FU) period, wherein some patients experienced a relapse.

We recruited remitted patients treated with antidepressant medication (ADM) and healthy controls matched for age, sex and education to the patients group. Patients were assessed at Main Assessment 1 (MA1) to identify features characterizing the remitted, medicated state. Next, patients were randomized to either discontinue their medication before MA2 (bottom arm, “group MA-1-D-MA2” or enter a waiting period while continuing their ADM, matched to the length of discontinuation time (top arm, “group MA1-MA2-D”). Discounting was assessed at MA1 and MA2, to investigate the effects of discontinuation. Patients in the MA1-MA2-D discontinued their ADM after MA2. After discontinuation, all patients entered the follow-up (FU) period of 6 months, during which some patients relapsed. Numbers below each box indicate the number of subjects in that group. The numbers below each box indicate the number of subjects in the corresponding group.

The data analysis plan for the current study was preregistered [56], and is provided in Supplementary Table 1. All participants answered rating questionnaires, among which, the measures of prior interest for the present study were Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D), Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ), Brief Self-Control Scale (BSCS), Daily Hassles, Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE), Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ), Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire (TLEQ), and the Mehrfachwahl-Wortschatz-Intelligenztest (MWT-B).

We also conducted a power analysis for group differences prior to the study commencement. The description of which is provided in the Supporting Material.

Delay discounting tasks

Delay-discounting procedures estimate the indifference point at which a smaller but immediately available reward, r, and a larger but delayed reward, R, have approximately the same subjective value to the participant. Here, participants completed two delay discounting tasks to estimate indifference points for rewards across a range of delays. The first task was Kirby’s monetary choice questionnaire (MCQ) [57], which consists of 27 items each asking participants to choose between an immediate and a delayed reward. In the second task, participants answered an adaptive version of the questionnaire [58], wherein a discount rate is estimated after each choice the subject makes, and the next immediate and delayed rewards offered are provided from the currently estimated indifference point. At each step, this procedure elicits the most informative choice, based on a participant’s estimated discount rate. The procedure continues until a stable estimation of the indifference point is reached [58]. Including two tasks, rather than one, was intended to bolster reliability.

In this study, rewards were hypothetical. Although one previous study found a small reduction in discount rates for real as opposed to hypothetical rewards [59], a number of other studies report no systematic differences in discounting for real and hypothetical rewards [60,61,62], suggesting that assessing discounting for hypothetical rewards is a valid procedure.

Delay discounting model and model fitting procedure

We modeled the participants’ choices using a standard hyperbolic model [63]:

This equation describes the subjective value, V, of a reward, R, available after a delay d. \(K \,{{{\rm{is}}}}\; {{{\rm{a}}}}\; {{{\rm{discount}}}}\; {{{\rm{rate}}}},{{{\rm{estimated}}}}\; {{{\rm{from}}}}\; {{{\rm{participants}}}}{{\hbox{'}}}{{{\rm{indifference}}}}\; {{{\rm{points}}}}.\;{{{\rm{Higher}}}}\; {{{\rm{values}}}}\; {{{\rm{of}}}}\) K reflect greater impatience and reduced tolerance for delay [52]. The hyperbolic model of delay discounting is illustrated in Fig. 2. A generalization of this hyperbolic model includes an exponent on the delay term, which adjusts the curvature of the discount curve [64, 65]. Here, since we are interested in individual differences, we omit this exponent in favour of the standard hyperbola, which captures variability in discounting with a single parameter, K.

Illustration of the hyperbolic model of delay discounting for a subset of nine questions from Kirby’s monetary choice questionnaire (MCQ) consisting of small amount of delayed reward (25$–35$). Each open white circle represents one of the nine questions: its X-coordinate indicates how long one would have to wait for the delayed reward (delay, d), while its Y-coordinate indicates the value of the immediate, no delay reward relative to the delayed reward (relative value, V/R). Each dotted curve represents the hyperbolic delay discount rate, K, at which a participant would be indifferent between immediate and delayed rewards for each specific choice. The dashed curve corresponds to a discount function with K = 0.01. A person with this fitted value of the discount rate would choose the immediate rewards in the questions with \(K\) values larger than \(0.01\) (bottom four hyperbolic curves), and would choose the delayed reward on the questions with \(K\) values smaller than \(0.01\) (top five hyperbolic curves). Open grey circles represent the subjective values, V(R, d), predicted by the dashed curve for each value of delay (d) of the nine questions. Adapted from [49, 59, 71].

We fitted the delay discounting model using a Bayesian hierarchical (mixed-effects) logistic regression [66]. This general procedure is widely used to fit parameters in decision making tasks, see e.g. [66,67,68,69]. In brief, estimated discount rate yields a difference in subjective value between immediate and delayed rewards for each choice. A logistic sigmoid (softmax) function, \(\sigma \left(x\right)=\frac{1}{1+\exp (-x)}\), transforms this subjective value difference into a probability of choosing the immediate reward on each choice. We used an optimization procedure to find parameters that maximize the joint probability of each participant’s observed choices, assuming an empirical prior distribution over discount rates. This prior distribution, which is estimated using Expectation-Maximization (EM), served to regularise the inference and prevent parameters that are not well-constrained from taking on extreme values [66]. The reader is referred to [66] for the full technical details of the routine.

To maximize reliability, we fitted the model to the concatenated answers of both the classic and the adaptive versions of the questionnaires. We estimated the goodness-of-fit of the resulting model using McFadden’s pseudo-R², averaged across all subjects [70]. Furthermore, after fitting the model, we excluded subjects whose model accuracy is not significantly better than chance, estimated by a corresponding binomial test with a significance threshold of 0.05. Specifically, we calculated \(p={\sum }_{i=k}^{n}\left(\begin{array}{c}n\\ i\end{array}\right){0.5}^{i}{0.5}^{n-i} \) and excluded participants for which p > 0.05. Here, n is the number of questions in the questionnaire, k is the number of correctly classified answers and p denotes the p-value of a right-tailed binomial test, i.e., the probability of obtaining k or more correct classifications out of n by chance.

Data analysis

Analyses were performed in Matlab (R2023a) according to the pre-registered analysis plan provided in Supplementary Table 1 and also in [56]. In each analysis step reported below, we refer the reader to the corresponding analysis step from Supplementary Table 1, or indicate the step was not part of the original analysis plan. In this study we report analyses of discounting choice data. For the sake of clarity, we divide the analyses into three categories: i) prediction of relapse, ii) effect of discontinuation, and iii) discounting in remitted MDD.

Since previous studies show that discount rates, K, are log-normally distributed [71, 72] we test for differences in log K rather than K. Unless otherwise stated, paired and independent-samples t-tests were used to compare group means. Given that each group comprised at least 30 participants, the Central Limit Theorem supports the assumption that the sampling distribution of the mean was approximately normal. Indeed, for each comparison, normality and equal variance were tested using Kolmogorov-Smirnov (MATLAB kstest function) and Bartlett tests (MATLAB vartestn test), respectively. For the few comparisons where either test rejected the null hypothesis of normality or equal variance, a non-parametric test was used: Wilcoxon Signed Rank for paired samples or Rank Sum for independent samples. We report means and standard deviations (or, where relevant, medians and interquartile ranges) for all comparisons in Supplementary Table 5.

Prediction of relapse

We started by testing for association between discount rate and relapse by using a one-tailed two-sample t-test to test if log K at MA1 was greater in patients who relapsed than in patients who did not relapse during follow-up. This test explores the potential of baseline log K as a predictor of future relapse. We also used a one-tailed two-sample t-test to test if the change in log K between MA1 and MA2 (gain scores) differed between subjects from the MA1-D-MA2 group who relapsed during follow-up and subjects from the MA1-D-MA2 group who did not relapse during follow-up. This test examines whether a change in log K following discontinuation is associated with subsequent relapse. The tests detailed in this paragraph were not part of the pre-registered analysis plan.

In addition, to test for an association between time to relapse and discount rate, we used MATLAB coxphfit function to fit a Cox proportional hazards model with days to relapse as the dependent variable. We fitted two such models, with independent variables as i) log K at MA1 (Step (4) in the analysis plan), or ii) log K at both MA1 and MA2 (Step (5) in the analysis plan).

To examine whether discount rates can predict subsequent relapse, we fitted a logistic regression model with an L1 regularization (known as “Lasso” [73]), as implemented by the lassoglm function in Matlab, with relapse as the dependent variable and either log K at MA1 (Step (4) in the analysis plan), or both log K at MA1 and log K at MA2 as independent variables (Step (5) in the analysis plan). Consistent with the analysis plan, the model was trained on subjects from the Zurich sample, with a view to testing on the Berlin sample. We applied tenfold cross validation with stratification to optimize the value of the L1-regularization parameter.

Effect of discontinuation

We also hypothesized that discontinuation at MA1 would be associated with an increase in log K (between MA1 and MA2), assessed relative to the group who discontinued at MA2. To test for this, we fitted a linear mixed effects model using MATLAB fitlme function, with log K at both timepoints as the dependent variable, and group (i.e., MA1-D-MA2 or MA1-MA2-D), timepoint (i.e., MA1 or MA2) and [group × timepoint], as independent (fixed effect) variables (Step (2) in the analysis plan). We included a random slope term for each participant.

Discounting in remitted MDD

We used a one-tailed two-sample t-test to test the hypothesis that log K at MA1 was greater in patients than in controls (Step (1) in the analysis plan). We also tested for associations between log K at MA1 and scores on the various rating scales, using simple linear regression, with log K as the dependent variable. Additionally, we expressed pairwise associations between log K at MA1 and each rating scale as a Spearman correlation coefficient (Step (3) in the analysis plan).

Finally, we tested whether log K at MA1 was associated with a change in depression (HAM-D) scores over time, independent of discontinuation (Step (6) in the analysis plan). To do so, we fitted a linear mixed effect model, wherein the dependent variable is HAM-D score (at MA1 or MA2), the independent variables (with fixed effects) are log K at MA1, timepoint (MA1 or MA2), a [log KMA1 × timepoint] interaction, discontinuation group (MA1-D-MA2 vs. MA1-MA2-D) and [discontinuation group × timepoint] interaction. We included a random slope for each participant. Here, the [log KMA1 × timepoint] interaction term expresses the extent to which a change in depression score across time depends on log K at baseline, whereas the [discontinuation group × timepoint] interaction term controls for possible confounding that results from testing on two discontinuation groups that differ in the time of withdrawal. Here we hypothesized that participants with higher baseline discounting would show less improvement in depressive symptoms across time.

Complementary analysis methods and results that appear in the a priori analysis plan are provided in the Supplementary Material. As set out in the analysis plan, all comparisons were performed first on the Zurich sample, with a view to testing on the Berlin sample as an out-of-sample validation of predictive accuracy. However, where no significant associations between log K and the variables of interest were found in either sample, we pooled both samples to maximize power. We report these pooled analyses here.

Results

Sample description

Out of 104 patients with remitted MDD and 57 controls who were initially recruited, 97 patients (71 from Zurich and 26 from Berlin; 77% female, average age 34.78) and 54 controls (32 from Zurich and 22 from Berlin; 70% female, average age 33.52) answered the discounting questionnaire at MA1. 47 and 50 patients were randomized at MA1 to the discontinuation (MA1-D-MA2) and continuation group (MA1-MA2-D), respectively. 10 patients dropped out before MA2 and 7 more patients dropped during the follow-up period. The 17 dropouts were excluded from the prediction of relapse analysis. Among the included patients, 52 remained well (65%) and 28 (35%) relapsed during the follow-up period. The numbers of participants in each group are also indicated in Fig. 1. At baseline, HAM-D scores in the remitted patient group, although below the clinical threshold for MDD, were significantly higher than those in the control group (HAM-D controls mean = 0.38, median = 0, HAM-D patients mean = 1.81, median = 1; two-sample, two-tailed t-test t(147) = 5.15, p < 0.001; Wilcoxon rank sum test p < 0.001).

Model fitting

Model accuracy met the (binomial test) accuracy criterion described above for all participants, and therefore no participants were excluded. The average model accuracy was 85%; mean McFadden’s pseudo-\({R}^{2}\) across subjects was 0.59, indicating a good fit to the data. Discount rates obtained from the adaptive discounting questionnaire and the Kirby MCQ were only moderately correlated (Spearman ρ = 0.32, p < 0.001).

In addition, no significant associations were found between log K at baseline and any possible confounding factors tested. The details and results are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Prediction of relapse

We found no significant difference in log K at MA1 between subjects treated with ADM who relapsed during follow-up and subjects treated with ADM who did not relapse (t(78) = 0.44, p > 0.25,two-tailed two-sample; Cohen’s d = 0.10). Furthermore, a change in log K following discontinuation (i.e., between MA1 and MA2 amongst the MA1-D-MA2 group), did not differ significantly between participants who subsequently relapsed and those who did not relapse (t(37) = 0.58, p > 0.25, one-tailed; Cohen’s d = 0.20), see Fig. 3. In a Cox proportional hazards regression model, including log K at both timepoints, neither log KMA1 nor log KMA2 were significantly associated with days-to-relapse (Coefficient log KMA1 = −0.02, p > 0.25; coefficient log KMA2 = −0.08, p > 0.25), nor was log KMA1 associated with relapse when entered into a separate regression model (Coefficient = −0.08, p > 0.25).

Cohen’s d effect size, for various group comparisons. The top bar shows the comparison of log K at MA1 between controls and patients, where the effect size in this case indicates that the average of log K in the Patients group (at both sites) at MA1 is greater than the average of log K in the Controls group at MA1. The second bar from above shows the comparison of log K at MA1 between patients who subsequently relapsed and patients who did not, where the effect size in this case indicates that the average of log K in non-relapsers at MA1 is greater than the average of log K in relapsers at MA1. The third bar shows the comparison of the change in log K between the two timepoints (gain scores), between patients who discontinued their treatment at MA1 (MA1-D-MA2) and patients who continued their treatment until MA2 (MA1-MA2-D), where the effect size indicates that the average of gain scores in the MA1-D-MA2 group is greater than the average of gain scores in the MA1-MA2-D group. The bottom bar shows the comparison of the change in log K between the two timepoints (gain scores), between patients from the MA1-D-MA2 group who subsequently relapsed and patients from the MA1-D-MA2 group who did not, where the effect size indicates that the average of gain scores in the non-relapsers group was greater than the average of gain scores in the relapsers group. Error bars represent 95% confidence interval for Cohen’s d effect size, estimated using MATLAB meanEffectSize function. Group difference p-value: * 0.01<p < 0.05.

In the prediction of relapse, the regularized regression weights were found to be all zero, resulting in a balanced accuracy of 0.5 and reflecting the balanced proportion of the majority class. For the sake of completeness, the distribution of baseline log K in the different relapse groups is shown in Supplementary Figure S1.

Effect of discontinuation

Contrary to our secondary hypothesis, antidepressant discontinuation was not associated with a significant increase in impulsive choice, relative to continuing medication. Specifically, in a linear mixed effects model with log K as the dependent variable, we found no significant [timepoint × discontinuation group] interaction (\({\beta }_{{timepoint\; x\; group}}\) = 0.04, t(180) = 0.15, p > 0.25). In other words, discontinuation did not significantly alter a change in log K across time. Main effects of timepoint and group were also small and non-significant (\({\beta }_{{group}}\) = −0.05, t(180) = −0.10, p > 0.25 ; \({\beta }_{{timepoint}}\) = 0.10, t(180) = 0.56, p > 0.25).

We further explored this null finding in a post hoc analysis, by performing a one-tailed two-sample t-test on log K gain scores to test whether log K increased more in patients who discontinued at MA1 (MA1-D-MA2) than in patients who discontinued at MA2 (MA1-MA2-D). To prevent error accumulation due to the additivity of noise, in model fitting, the difference between log K at MA1 and log K at MA2 was estimated concurrently with log K at MA1. Again, we found no significant difference in the change in log K between MA1 and MA2, among the MA1-D-MA2 group compared with the MA1-MA2-D group (t(82) = 0.19, p > 0.25; Cohen’s d = 0.04), also indicated in Fig. 3.

A possible explanation for these null results would be that our delay discounting measure was unreliable. If this were the case, we would expect no consistent relationship between discounting at MA1 and MA2. Contrary to this idea however, across all patients we found a moderate correlation between log K at the two timepoints (r = 0.72, p < 0.001). Similar test-retest correlations were observed in both the MA1-D-MA2 (r = 0.80, p < 0.001) and MA1-MA2-D groups (r = 0.65, p < 0.001). These results indicate that the rank order of discounting across participants was moderately stable over time, supporting the reliability of our discounting measure.

A further possible explanation for observing no effect of discontinuation on impulsivity would be that discontinuation produced no significant withdrawal syndrome in the study participants. Against this, the MA1-D-MA2 group exhibited a statistically significant increase in depressive symptoms following discontinuation (MA1 HAM-D mean = 1.65, median = 1; MA2 HAM-D mean = 3.16, median = 3; t(39) = 4.39, p < 0.001, two-tailed; Wilcoxon signed rank p < 0.001). No such symptom change was observed in the MA1-MA2-D group, who did not discontinue medication until after the second timepoint (MA1 HAM-D mean = 1.98, median = 2; MA2 HAM-D mean = 2.18, median = 2; t(40) = 0.34, p = 0.733, two-tailed; Wilcoxon signed rank p = 0.610). Furthermore, symptom change between the two timepoints in the MA1-D-MA2 group was significantly greater than that in the MA1-MA2-D group (two-sample t-test, t(79) = 2.77, p = 0.007, two-tailed; Wilcoxon rank sum p = 0.013). These findings indicate a detectable effect of discontinuation.

Discounting in remitted MDD

Group comparison of log K between healthy controls and patients with remitted MDD (treated with ADM) at MA1 revealed significantly higher discount rates in the patient group (t(149) = 2.03 and p = 0.022, one-tailed; Cohen’s d = 0.34), also indicated in Fig. 3. Notably both groups showed low levels of impulsivity, and the absolute difference in K between the two groups was small. Mean K in the remitted MDD group was 0.0065, corresponding to indifference between a reward of 75 euros received in 20 days and an immediate reward of 66 euros. Mean K in the control group was 0.0037, corresponding to indifference between a reward of 75 euros received in 20 days and an immediate reward of 70 euros.

As shown in Fig. 4, depressive symptoms (measured by the HAM-D scale) were significantly correlated with baseline discount rate, log KMA1 (Spearman ρ = 0.24, p = 0.003), an association which survived Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (p = 0.022, corrected for 8 comparisons), and was also present when testing only on the patients’ group (Spearman ρ = 0.23, p = 0.025). Other questionnaire instruments did not exhibit significant correlations with log KMA1 (Fig. 4). We note that baseline discount rate showed a significant correlation with two subscales of the CTQ questionnaire, namely CTQ-physical abuse (Spearman ρ = 0.18, p = 0.023) and CTQ-emotional neglect (Spearman ρ = 0.16, p = 0.049). See Supplementary Figure S2 for the comparisons with other questionnaire subscales. When all questionnaire variables were entered into a linear regression model with log KMA1 as the dependent variable, only HAM-D emerged as a significant explanatory variable (coefficient estimate = 0.19, t(142) = 2.51, p = 0.013). Coefficients and t-statistics for the remaining rating scales are provided in Supplementary Table 3.

HAM-D Hamilton Depression Scale, ERQ Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ), BSCS Brief Self-Control Scale, SWLS Satisfaction with Life Scale, ACE Adverse Childhood Experience, CTQ Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, TLEQ Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire, MWTB Mehrfachwahl-Wortschatz-Intelligenztest. Error bars represent 95% confidence interval for Spearman’s correlation coefficient estimated using 10,000 bootstrap iterations. Group difference p-value: * 0.01<p < 0.05, ** 0.001<p < 0.01.

We went on to test for an association between a change in depression across time, and baseline discounting (at MA1), in a mixed-effects linear regression with HAM-D scores as the dependent variable. We found a significant main effect of log KMA1 (coefficient estimate = 0.56, t(150) = 2.26, p = 0.025). This result is consistent with the findings reported above of a correlation between log KMA1 and HAM-D at MA1. We found no significant main effect of timepoint (coefficient estimate = 0.01, t(150) = 0.01, p = 0.989); here, the positive coefficient indicates that the average participant showed a marginal, albeit non-significant, increase in HAM-D score across time. There was a significant [timepoint × log K] interaction (coefficient estimate = −0.30, t(150) = −2.01, p = 0.045). Here, contrary to our prediction, the negative coefficient indicates that participants who were more impulsive (higher log K) at baseline showed a greater reduction in depression score across time. We found no significant effect of discontinuation group(coefficient estimate = 0.19, t(150) = 0.22, p = 0.820), nor a significant effect of the [discontinuation group × timepoint] interaction (coefficient estimate = −0.47, t(150) = −0.94, p = 0.345).

Discussion

In this pre-registered analysis, we examined the potential of delay discounting as a behavioral marker of relapse after antidepressant discontinuation. There is a priori evidence to suggest that delay discounting might help predict illness trajectory following discontinuation of antidepressant medication (ADM). To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to prospectively examine i) whether discounting predicts future depressive relapse following ADM discontinuation, and ii) the effect of ADM discontinuation on delay discounting. Our results suggest that delay discounting is not altered by ADM discontinuation to a clinically meaningful extent. Furthermore, we found that neither baseline delay discounting, nor a change in discounting following ADM discontinuation were predictive of future depressive relapse. However, we did find significantly steeper delay discounting amongst patients with remitted MDD, compared with controls (Cohen’s d = 0.34), and a robust relationship between the discount rate and depressive symptoms (Spearman ρ = 0.24).

We note that our observed correlation between delay discounting and depressive symptoms may be attributable to subdomains of depressive symptoms. This possibility accords with previous studies finding relationships between discounting and symptom variables such as hopelessness, anhedonia [31] and suicidal ideation [24] or acts [35]. Owen et al. [37] reported a loss of evaluative differentiation concerning future outcomes in patients with MDD, which might serve as an explanation for our findings.

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to find significantly elevated delay discounting amongst medicated patients with remitted MDD. This finding is consistent with previous studies that have observed a relationship between trait-level impulsivity (e.g., as assessed in self-report rating scales) and remitted depression [74, 75]. A previous study by Pulcu et al. [26], which compared delay discounting amongst people with remitted, medication-free MDD and healthy controls, found that patients with remitted depression showed marginally steeper discounting than controls, however this difference was statistically significant only for larger rewards. In both the study of Pulcu et al., and the present study, depressive symptoms were significantly correlated with discount rate across all participants. The elevated discounting seen here in remitted MDD might therefore reflect residual, sub-clinical depressive symptoms. In keeping with this hypothesis, the remitted patient group exhibited higher depressive symptom scores than the control group.

Alternatively, discounting might partly capture a trait-level vulnerability to depression, which persists despite symptom resolution. Previous studies find that delay discounting indeed has properties of a trait variable, being conserved across different types of reward [76], with moderate test-retest reliability [77]. Our combined delay-discounting score exhibited a similar degree of stability within-participants across the two time points of the study (r = 0.72) to that recently reported in meta-analysis (r = 0.670, 95% CI [0.618, 0.716]) [77]. These findings suggest that delay discounting can be considered a trait variable. However, since our study did not measure discounting longitudinally in patients as they moved into remission, we have no direct evidence to support an hypothesis that steeper discounting is a vulnerability factor for MDD.

In the current study, higher discounting at baseline was not predictive of future relapse following discontinuation; nor was baseline discounting associated with worsening depressive symptoms between the two timepoints of the study (up to six months apart). The relatively small sample size of this study may be underpowered to detect subtle relationships. For example, a post-hoc power analysis for a two-tailed two-sample t-test with a type I error rate of α = 0.05, comparing 28 relapsers and 52 non-relapsers, indicates a power of 0.8 to detect an effect size of d = 0.66 and a power of 0.95 to detect an effect size of d = 0.85. Furthermore, the power to detect a medium effect size of d = 0.5 is 0.55 (using G★-power 3.1 [78]). While we do not provide evidence for the absence of effects, power considerations inform our interpretation and suggest that large effect sizes, greater than 0.5, are unlikely.

Another limitation that restricts our ability to accurately predict future risk of relapse is the limited six-month follow-up period, which may lead us to overlook patients who did not relapse during this time period but might have relapsed if observed for a longer duration. Nevertheless, our null finding suggests that, if discounting is indeed a trait-level vulnerability factor for MDD, this effect is too small to be clinically meaningful over short-term follow up.

A potential limitation of our statistical analyses concerns how the hierarchical Bayesian procedure used to estimate the discount rate was applied in the context of a regularized regression analysis to predict relapse. Within the cross-validation framework used to optimize the regularization parameter discount rate was not fitted separately for training and validation sets of each fold, resulting in non-independent estimates between these two sets, and potentially optimistic estimates of prediction accuracy. However, this concern is mitigated in our specific case as the prediction results remain insignificant. Furthermore, the issue does not affect the critical test of training the model on the Zurich dataset and testing it on the Berlin dataset.

Contrary to our prediction, higher impulsivity at baseline was associated with a marginally significant decrease in depressive score across time. We are uncertain as to the explanation for this effect. We speculate that higher impulsivity is linked to greater venturesomeness, which encourages exploration and thereby recovery from depression. Alternatively, this unexpected finding might arise due to regression to the mean of depressive symptoms across time. That is, since participants with higher baseline impulsivity tended to show higher baseline depressive symptoms, if higher baseline symptoms tended to regress to the mean over time, impulsivity also would appear to be weakly associated with symptomatic improvement. However, since this finding is against our prior predictions, further replication is needed.

A secondary hypothesis was based on an idea that discounting would be a sensitive marker of psycho-physiological changes following ADM discontinuation. However, we did not observe an increase in impulsivity following ADM discontinuation. Specifically, we did not find a significant change in log K amongst remitted patients who discontinued their treatment (MA1-D-MA2 group), relative to remitted patients who continued their treatment (MA1-MA2-D group). This finding is also consistent with an AIDA study of effort-reward tradeoffs [52], where the authors found no effect of ADM discontinuation on choices of high-effort high-reward options. Although our finding may be the result of limited statistical power, the relatively small effect sizes obtained from the corresponding group comparisons (Cohen’s d < 0.1), as well as the significant group differences obtained in other comparisons, suggest otherwise. Indeed, our finding of a small yet statistically significant increase in depressive symptoms following ADM discontinuation, indicating that stopping medication had a clinically detectable effect, further points to a dissociation between discounting and discontinuation.

We had hypothesized that discounting might be sensitive to decreases in serotonergic neuromodulation following antidepressant discontinuation. However, although discounting has been shown to be sensitive to serotonergic manipulations, it is unclear whether the elevated discounting observed in MDD is linked to changes in serotonin. Furthermore, the directionality and temporality of the adaptive changes in the 5-HT system following antidepressant discontinuation are uncertain. Some evidence points to a reduction in the extracellular 5-HT levels following discontinuation [79, 80], while other studies indicate a rebound above pre-treatment levels (see e.g. [80,81,82,83]). Taking these considerations together, a lack of association between discounting and ADM discontinuation is not out of keeping with the state of existing knowledge concerning causal relationships between serotonergic function, depressive disorders and ADM.

Conclusion

Delay discounting is not strongly affected by ADM discontinuation and therefore appears to be of limited use as a biomarker for decisions related to anti-depressant discontinuation.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and in line with the ethical rules.

Code availability

The MATLAB code used to analyse the data is available upon reasonable request to the corresponding authors.

Notes

The term ‘relapse’ is conventionally reserved for episodes within the first six months, after which the term ‘recurrence’ is usually employed. In this study, since the time from first episode varied amongst our patient group, we do not distinguish between relapse and recurrence, and adopt the term ‘relapse’ throughout.

References

WHO. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates (World Health Organization, 2017).

GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global. Regional, and National Burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. The Lancet Psychiatry 2022;9,137–150.

Lépine J-P, Briley M. The increasing burden of depression. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:3.

American Psychiatric Association, A.; Association, A. P. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5; Washington, DC: American psychiatric association, 2013; Vol. 10.

Geddes JR, Carney SM, Davies C, Furukawa TA, Kupfer DJ, Frank E, et al. Relapse prevention with antidepressant drug treatment in depressive disorders: a systematic review. Lancet. 2003;361:653–61.

Kaymaz N, van Os J, Loonen AJ, Nolen WA. Evidence that patients with single versus recurrent depressive episodes are differentially sensitive to treatment discontinuation: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:6813.

Glue P, Donovan MR, Kolluri S, Emir B. Meta-analysis of relapse prevention antidepressant trials in depressive disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44:697–705.

Sim K, Lau WK, Sim J, Sum MY, Baldessarini RJ. Prevention of relapse and recurrence in adults with major depressive disorder: systematic review and meta-analyses of controlled trials. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;19:pyv076.

Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Stewart JW, Warden D, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: A STAR* D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1905–17.

Olfson M, Marcus SC, Tedeschi M, Wan GJ. Continuity of antidepressant treatment for adults with depression in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:101–8.

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Depression: The Treatment and Management of Depression in Adults (Updated Edition). Leicester (UK): British Psychological Society. 2010.

Recommendations Depression in adults: treatment and management | Guidance | NICE. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng222/chapter/Recommendations#preventing-relapse Accessed 2023-09-14.

Trinh N-HT, Shyu I, McGrath PJ, Clain A, Baer L, Fava M, et al. Examining the Role of Race and ethnicity in relapse rates of major depressive disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2011;52:151–5.

McGrath PJ, Stewart JW, Petkova E, Quitkin FM, Amsterdam JD, Fawcett J, et al. Predictors of relapse during fluoxetine continuation or maintenance treatment of major depression. J Clin Psychiat. 2000;61:518–24.

Joliat MJ, Schmidt ME, Fava M, Zhang S, Michelson D, Trapp NJ, et al. Long-term treatment outcomes of depression with associated anxiety: efficacy of continuation treatment with fluoxetine. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1080.

Fava M, Wiltse C, Walker D, Brecht S, Chen A, Perahia D. Predictors of relapse in a study of duloxetine treatment in patients with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2009;113:263–71.

Stewart JW, Quitkin FM, McGrath PJ, Amsterdam J, Fava M, Fawcett J, et al. Use of pattern analysis to predict differential relapse of remitted patients with major depression during 1 year of treatment with fluoxetine or placebo. Arch Gen Psychiat. 1998;55:334–43.

Berwian IM, Walter H, Seifritz E, Huys QJ. Predicting relapse after antidepressant withdrawal–a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2017;47:426–37.

Viguera AC, Baldessarini RJ, Friedberg J. Discontinuing antidepressant treatment in major depression. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1998;5:293–306.

Bickel WK, Athamneh LN, Basso JC, Mellis AM, DeHart WB, Craft WH, et al. Excessive discounting of delayed reinforcers as a trans-disease process: update on the state of the science. Curr Opin Psychol. 2019;30:59–64.

Frost R, McNaughton N. The neural basis of delay discounting: a review and preliminary model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;79:48–65.

Critchfield TS, Kollins SH. Temporal discounting: basic research and the analysis of socially important behavior. J Appl Behav Anal. 2001;34:101–22. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2001.34-101

Koffarnus MN, Jarmolowicz DP, Mueller ET, Bickel WK. Changing delay discounting in the light of the competing neurobehavioral decision systems theory: a review: changing delay discounting. J Exp Anal Behav. 2013;99:32–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/jeab.2

Cáceda R, Durand D, Cortes E, Prendes-Alvarez S, Moskovciak T, Harvey PD, et al. Impulsive choice and psychological pain in acutely suicidal depressed patients. Psychosom Med. 2014;76:445–51. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000075

Engelmann JB, Maciuba B, Vaughan C, Paulus MP, Dunlop BW. Posttraumatic stress disorder increases sensitivity to long term losses among patients with major depressive disorder. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e78292 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0078292

Pulcu E, Trotter PD, Thomas EJ, McFarquhar M, Juhász G, Sahakian BJ, et al. Temporal discounting in major depressive disorder. Psychol Med. 2014;44:1825–34.

Imhoff S, Harris M, Weiser J, Reynolds B. Delay discounting by depressed and non-depressed adolescent smokers and non-smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;135:152–5.

Brown HE, Hart KL, Snapper LA, Roffman JL, Perlis RH. Impairment in delay discounting in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder but not primary mood disorders. npj Schizophr. 2018;4:9 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-018-0050-z

Weidberg S, García-Rodríguez O, Yoon JH, Secades-Villa R. Interaction of depressive symptoms and smoking abstinence on delay discounting rates. Psychol Addictive Behav. 2015;29:1041–7. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000073

Amlung M, Marsden E, Holshausen K, Morris V, Patel H, Vedelago L, et al. Delay discounting as a transdiagnostic process in psychiatric disorders: a meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76:1176–86.

Lempert KM, Pizzagalli DA. Delay discounting and future-directed thinking in anhedonic individuals. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2010;41:258–64.

Szuhany KL, MacKenzie Jr D, Otto MW. The impact of depressed mood, working memory capacity, and priming on delay discounting. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2018;60:37–41.

Felton JW, Strutz KL, McCauley HL, Poland CA, Barnhart KJ, Lejuez CW. Delay discounting interacts with distress tolerance to predict depression and alcohol use disorders among individuals receiving inpatient substance use services. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2020;18:1416–21.

Moody L, Franck C, Bickel WK. Comorbid depression, antisocial personality, and substance dependence: relationship with delay discounting. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;160:190–6.

Dombrovski AY, Szanto K, Siegle GJ, Wallace ML, Forman SD, Sahakian B, et al. Lethal forethought: delayed reward discounting differentiates high-and low-lethality suicide attempts in old age. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70:138–44.

Takahashi T, Oono H, Inoue T, Boku S, Kako Y, Kitaichi Y, et al. Depressive patients are more impulsive and inconsistent in intertemporal choice behavior for monetary gain and loss than healthy subjects--an analysis based on Tsallis’ statistics. Neuro Endocrinology Letters 2008;29:351–8.

Owen GS, Martin W, Gergel T. Misevaluating the future: affective disorder and decision-making capacity for treatment–a temporal understanding. Psychopathology. 2019;51:371–9.

Cowen PJ, Browning M. What has serotonin to do with depression? World Psychiatry. 2015;14:158.

Ruhé HG, Frokjaer VG, Haarman BCM, Jacobs GE, Booij J, Molecular Imaging of Depressive Disorders. In PET and SPECT in Psychiatry; Dierckx, RAJO, Otte, A, et al. Eds.; Cham: Springer International Publishing:, 2021; pp 85–207.

Neumeister A, Nugent AC, Waldeck T, Geraci M, Schwarz M, Bonne O, et al. Neural and behavioral responses to tryptophan depletion in unmedicated patients with remitted major depressive disorder and controls. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:765–73.

Cowen PJ. Serotonin and depression: pathophysiological mechanism or marketing myth? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29:433–6.

Schweighofer N, Bertin M, Shishida K, Okamoto Y, Tanaka SC, Yamawaki S, et al. Low-serotonin levels increase delayed reward discounting in humans. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4528–32.

Crockett MJ, Clark L, Lieberman MD, Tabibnia G, Robbins TW. Impulsive choice and altruistic punishment are correlated and increase in tandem with serotonin depletion. Emotion. 2010;10:855–62.

Tanaka SC, Schweighofer N, Asahi S, Shishida K, Okamoto Y, Yamawaki S, et al. Serotonin differentially regulates short- and long-term prediction of rewards in the ventral and dorsal striatum. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e1333.

Carlisi CO, Chantiluke K, Norman L, Christakou A, Barrett N, Giampietro V, et al. The effects of acute fluoxetine administration on temporal discounting in youth with ADHD. Psychological Med. 2016;46:1197–209.

Miyazaki KW, Miyazaki K, Tanaka KF, Yamanaka A, Takahashi A, Tabuchi S, et al. Optogenetic activation of dorsal raphe serotonin neurons enhances patience for future rewards. Curr Biol. 2014;24:2033–40.

Miyazaki K, Miyazaki KW, Sivori G, Yamanaka A, Tanaka KF, Doya K. Serotonergic projections to the orbitofrontal and medial prefrontal cortices differentially modulate waiting for future rewards. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eabc7246.

Wogar MA, Bradshaw CM, Szabadi E. Effect of lesions of the ascending 5-hydroxytryptaminergic pathways on choice between delayed reinforcers. Psychopharmacology. 1993;111:239–43.

Mobini S, Chiang T-J, Ho M-Y, Bradshaw CM, Szabadi E. Effects of central 5-hydroxytryptamine depletion on sensitivity to delayed and probabilistic reinforcement. Psychopharmacology. 2000;152:390–7.

Denk F, Walton ME, Jennings KA, Sharp T, Rushworth MFS, Bannerman DM. Differential involvement of serotonin and dopamine systems in cost-benefit decisions about delay or effort. Psychopharmacology. 2005;179:587–96.

Berwian IM, Wenzel JG, Kuehn L, Schnuerer I, Seifritz E, Stephan KE, et al. Low predictive power of clinical features for relapse prediction after antidepressant discontinuation in a naturalistic setting. Sci Rep. 2022;12:1–11.

Berwian IM, Wenzel JG, Collins AG, Seifritz E, Stephan KE, Walter H, et al. Computational mechanisms of effort and reward decisions in patients with depression and their association with relapse after antidepressant discontinuation. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77:513–22.

Berwian IM, Wenzel JG, Kuehn L, Schnuerer I, Kasper L, Veer IM, et al. The relationship between resting-state functional connectivity, antidepressant discontinuation and depression relapse. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1–10.

Wakefield JC, Schmitz MF. When does depression become a disorder? using recurrence rates to evaluate the validity of proposed changes in major depression diagnostic thresholds. World Psychiatry. 2013;12:44–52.

Williams JB. A structured interview guide for the hamilton depression rating scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:742–7.

Delay Discounting Analysis Plan. https://github.com/doronelad/AIDA_analysis_discouting/blob/main/AnalysisPlan_Discounting.pdf.

Kirby KN, Petry NM, Bickel WK. Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug-using controls. J Exp Psychol Gen. 1999;128:78.

Pooseh S, Bernhardt N, Guevara A, Huys QJ, Smolka MN. Value-based decision-making battery: a bayesian adaptive approach to assess impulsive and risky behavior. Behav Res Methods. 2018;50:236–49.

Hinvest NS, Anderson IM. The effects of real versus hypothetical reward on delay and probability discounting. Q J Exp Psychol. 2010;63:1072–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470210903276350

Johnson MW, Bickel WK. Within-subject comparison of real and hypothetical money rewards in delay discounting. J Exp Anal Behav. 2002;77:129–46. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.2002.77-129

Madden GJ, Raiff BR, Lagorio CH, Begotka AM, Mueller AM, Hehli DJ, et al. Delay discounting of potentially real and hypothetical rewards: II. Between- and within-subject comparisons. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;12:251–61. https://doi.org/10.1037/1064-1297.12.4.251

Lagorio CH, Madden GJ. Delay discounting of real and hypothetical rewards III: steady-state assessments, forced-choice trials, and all real rewards. Behav Process. 2005;69:173–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2005.02.003

Mazur JE. An adjusting procedure for studying delayed reinforcement. Quant Anal Behav. 1987;5:55–73.

Van den Bos W, McClure SM. Towards a general model of temporal discounting. J Exp Anal Behav. 2013;99:58–73.

McKerchar TL, Green L, Myerson J, Pickford TS, Hill JC, Stout SC. A comparison of four models of delay discounting in humans. Behav Process. 2009;81:256–9.

Huys QJ, Cools R, Gölzer M, Friedel E, Heinz A, Dolan RJ, et al. Disentangling the roles of approach, activation and valence in instrumental and pavlovian responding. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7:e1002028.

Guitart-Masip M, Huys QJ, Fuentemilla L, Dayan P, Duzel E, Dolan RJ. Go and No-Go learning in reward and punishment: interactions between affect and effect. Neuroimage. 2012;62:154–66.

Gillan CM, Kosinski M, Whelan R, Phelps EA, Daw ND. Characterizing a psychiatric symptom dimension related to deficits in goal-directed control. elife. 2016;5:e11305.

Akam T, Rodrigues-Vaz I, Marcelo I, Zhang X, Pereira M, Oliveira RF, et al. The anterior cingulate cortex predicts future states to mediate model-based action selection. Neuron. 2021;109:149–63.

McFadden, D Conditional Logit Analysis of Qualitative Choice Behavior. 1973.

Myerson J, Baumann AA, Green L. Discounting of delayed rewards:(A) theoretical interpretation of the kirby questionnaire. Behav Process. 2014;107:99–105.

Wilson AG, Franck CT, Mueller ET, Landes RD, Kowal BP, Yi R, et al. Predictors of delay discounting among smokers: education level and a utility measure of cigarette reinforcement efficacy are better predictors than demographics, smoking characteristics, executive functioning, impulsivity, or time perception. Addict Behav. 2015;45:124–33.

Tibshirani R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J R Stat Soc Ser B Stat Methodol. 1996;58:267–88.

Saddichha S, Schuetz C. Impulsivity in remitted depression: a meta-analytical review. Asian J Psychiatry. 2014;9:13–16.

Altaweel N, Upthegrove R, Surtees A, Durdurak B, Marwaha S. Personality traits as risk factors for relapse or recurrence in major depression: a systematic review. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:709.

Odum AL. Delay discounting: trait variable? Behav Proc. 2011;87:1–9.

Gelino BW, Schlitzer RD, Reed DD, Strickland JC. A systematic review and meta‐analysis of test–retest reliability and stability of delay and probability discounting. J Exp Anal Behav. 2024;121:358–72.

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang A-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41:1149–60.

Guiard BP, Mansari ME, Murphy DL, Blier P. Altered response to the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor escitalopram in mice heterozygous for the serotonin transporter: an electrophysiological and neurochemical study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15:349–61.

Collins, HM Investigation of the Behavioural and Neurobiological Effects of SSRI Discontinuation in Mice. PhD Thesis, University of Oxford, 2023. https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:97caafe1-ea12-460b-8c1d-0de202db5592. Accessed 2023-09-24)

Trouvin JH, Gardier AM, Chanut E, Pages N, Jacquot C. Time course of brain serotonin metabolism after cessation of long-term fluoxetine treatment in the rat. Life Sci. 1993;52:PL187–PL192.

Caccia S, Fracasso C, Garattini S, Guiso G, Sarati S. Effects of short-and long-term administration of fluoxetine on the monoamine content of rat brain. Neuropharmacology. 1992;31:343–7.

Bosker FJ, Tanke MA, Jongsma ME, Cremers TI, Jagtman E, Pietersen CY, et al. Biochemical and behavioral effects of long-term citalopram administration and discontinuation in rats: role of serotonin synthesis. Neurochem Int. 2010;57:948–57.

Elad, D; Story, GW; Berwian, IM; Stephan, KE; Walter, H; Huys, Q Delay discounting correlates with depression but does not predict relapse after antidepressant discontinuation. OSF. 2024. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/5buq4.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Inga Schnuerer, Dipl Psych, and Daniel Renz (Translational Neuromodeling Unit, University of Zurich and ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland) and Julia G. Wenzel, Leonie Kuehn and Christian Stoppel, MD, PhD (Charité Universitätsmedizin, Campus Charité Mitte, Berlin, Germany) for their help in acquiring the data.

Funding

The AIDA study was funded by a Swiss National Science Foundation grant to QH (320030L_153449/1) and the German Research Foundation to HW (WA1539/5-1). QJMH acknowledges support by the UCLH NIHR BRC. Additional funds were provided by the Clinical Research Priority Program “Molecular Imaging” at the University of Zurich and by the René and Susanne Braginsky Foundation (KES).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.J.M.H and H.W conceived and designed the study with critical input from K.E.S.; I.M.B collected the data under the supervision of Q.J.M.H and H.W.; K.E.S was the study sponsor in Zurich.; Q.J.M.H, K.E.S and H.W. acquired funding for the study.; G.W.S, I.M.B and Q.J.M.H formulated the pre-registered analysis plan.; D.E and G.W.S performed the analyses and wrote the manuscript. All authors provided critical comments, read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

QJMH reports receiving fees and options for consultancies for Aya Technologies and Alto Neuroscience; and research grant funding Koa Health. The other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design, conduct or analysis of the study and had no influence over the decision to publish. The authors disclose that this manuscript has been posted in the preprint server PsyArxiv on August 18, 2024 [84].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elad, D., Story, G.W., Berwian, I.M. et al. Delay discounting correlates with depression but does not predict relapse after antidepressant discontinuation. Mol Psychiatry (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-025-03402-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-025-03402-5