Abstract

Nociceptin/orphanin FQ (N/OFQ), an endogenous opioid neuropeptide, and its G-protein coupled receptor NOPR have been implicated in motivation, feeding behaviors, and aversion. Stress-induced dysfunction in these states is central to the development of numerous psychiatric disorders, and the N/OFQ-NOPR system’s role in reward- and stress-related responses has driven broad interest in NOPR as a therapeutic target for anxiety and depression. However, the impact of stress on N/OFQ signaling in the context of its influence on discrete midbrain reward circuitry remains unknown. To this end, we focused on a possible candidate population of N/OFQ neurons in the paranigral ventral tegmental area (pnVTAPNOC) that have been shown to act locally on NOPR-containing VTA dopamine neurons to suppress motivation. Here we report and characterize pnVTAPNOC sensitivity during exposure to a diverse range of stressors. Our results indicate that pnVTAPNOC neurons become recruited during exposure to a variety of acute stressor types, suggesting that this N/OFQ population in the pnVTA could act as a critical bridge between stress and motivation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stress exposure is a major risk factor in the development of addiction, relapse susceptibility, anxiety, and mood disorders, all of which collectively impose a staggering global health burden [1,2,3,4]. While these disorders are vastly diverse, they all commonly involve the emergence of anhedonia and atypical motivation, indicating that the neurobiological mechanisms driving functional reward-related behaviors are highly susceptible to disruption in these disease states [5,6,7,8,9]. Understanding the circuitry and neurobiological substrates central to reward processing that become altered by stress is a critical first step toward identifying viable therapeutic targets with improved function.

The mesolimbic pathway, comprised of dopaminergic projections from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to the nucleus accumbens (NAc), plays a central role in processing and responding to reward [10, 11]. Converging animal [12,13,14] and human studies [15,16,17,18] have demonstrated that acute stress impacts neural activity within mesolimbic circuitry. In the VTA specifically, stress is generally found to have a net effect of suppressing VTA dopamine (DA) neuron activity [19, 20]. Recent studies have also expanded on the VTA’s molecular complexity by revealing diverse neuropeptide subpopulations, released both by the VTA itself and by upstream inputs that have significant influence over this critical reward circuitry [21,22,23,24].

Among these subpopulations, neurons in the paranigral nucleus of the VTA (pnVTA) enriched with the endogenous opioid peptide nociceptin/orphanin FQ (N/OFQ) have recently emerged as key regulators of motivated behavior [25]. Our group previously reported that activation of these N/OFQ-expressing pnVTA neurons (pnVTAPNOC neurons) suppresses motivated reward-seeking behavior and drives aversive responses. Notably, N/OFQ signaling through its cognate G-protein coupled receptor NOPR, which is largely expressed on VTA DA neurons [26], negatively regulates dopamine tone [27], paralleling the effects of stress. Despite widespread implications of N/OFQ in stress responses [28], whether stress impacts this particular pnVTAPNOC population which is critically situated to regulate motivation and reward-related behaviors remains unexplored.

Here, we employed in vivo calcium imaging with the genetically-encoded calcium indicator GCaMP to monitor pnVTAPNOC neuronal dynamics during exposure to physical, environmental, and predatory forms of stress. These findings contribute to a growing understanding of VTA circuitry in stress processing and identify a unique role of pnVTA N/OFQ neurons as a tenable bridge underlying stress regulation of motivated behavior.

Materials and methods

Animals

Adult (18–35 g, 3–6 months old) male and female Pnoc-IRES-Cre (PNOC-Cre) mice were group housed in the animal facility at 22–24 °C on a 12 h/12 h reverse light/dark cycle (9:00 AM lights off) in ventilated cages with ad libitum access to standard chow and water. All animals were monitored for health status daily and before experimentation for the entirety of the study. Animal procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Washington and conformed to US National Institutes of Health guidelines. All resources are listed in Table S1.

Stereotaxic surgery

All coordinates, viruses, and volumes for experiments are listed in Table S2. After acclimating to the holding facility for at least seven days, mice were anaesthetized in an induction chamber (1–4% isoflurane) and placed into a stereotaxic frame (Kopf Instruments, model 1900) where they were maintained at 1–2% isoflurane. A blunt needle syringe (86200, Hamilton Company) was used to deliver virus at a rate of 100 nL/min in the pnVTA. An optic fiber (400 µm core, 2.5 mm ferrule, Doric) was slowly lowered to 0.05 mm above the injection site and secured using MetaBond (C & B Metabond). A stainless-steel head-ring was also secured on animals undergoing air puff to allow for head-fixation. Animals were allowed to recover from surgery for a minimum of 3 weeks before any behavioral testing, permitting optimal viral expression.

Fiber photometry recordings

Fiber photometry studies were completed as described previously [29] (see Supplementary Methods). In brief, GCaMP6s fluorescence was excited using a 470 nm LED (Ca2+-dependent signal) and a 405 nm LED (isosbestic control, Ca2+-independent signal). LED intensities were set to 30 µW at the optic fiber tip. GCaMP6s emissions were filtered (525 ± 25 nm), detected with a photoreceiver, and recorded by a real-time processor.

In vivo animal experiments

All animal behaviors were performed within a sound-attenuated room maintained at 23 °C at least one week after habituation to the holding room. Animals were handled for a minimum of three days prior to experimentation and were habituated to fiber photometry patch cord attachment to their fiber implants. For all experiments, mice were brought into the experimental room and allowed to acclimate to the space for at least 30 min prior to any testing. All experiments were conducted in red light to accommodate the reverse light cycle schedule, unless otherwise stated. All sessions were video recorded.

Behaviors

Cued foot shock

Mice were placed in Med Associates Fear Conditioning Chambers (NIR-022MD) which consisted of a 29.5 × 23.5 × 21 cm chamber with a conductive grid floor lit by infrared light and contained within a soundproof box. Mice were exposed to ten 10 s tones co-terminating with a 2 s 0.5 mA shock with a variable inter-trial interval (VITI) of 45–90s.

Tail lift

Mice were placed in a 10” x 10” clear acrylic box illuminated by a dim, diffuse white light ( ~ 30 lux). Mice were suspended by the tail four times for 20 s with a VITI of 120–180s. All suspensions were made to the same height.

Air puff

Four days prior to testing, mice were habituated to head-fixation on the OHRBETS platform as described previously [29, 30]. A fixed, solenoid-controlled O2 valve was positioned above the animal’s left whiskers. Mice were exposed to fifteen 0.1 s 20 PSI air puffs with a VITI of 45–75s. Solenoid opening (Parker, 003-0257-900) was controlled using an Arduino Mega 2560 REV3 (Arduino) and custom Arduino programs.

Looming

Mice were placed in a white-walled plexiglass arena (50 × 50 cm) illuminated by a diffuse white light ( ~ 80 lux) and allowed to roam freely. Looming was simulated four times via a posterboard blocking the arena’s overhead lighting (arena illumination reduced to ~25 lux) for 1–2s, with an ITI of 120 s.

Odor delivery

Mice were placed in a polyethylene chamber approximately 12 × 12 x 24 cm where air was continuously vacuumed out at a rate of 2 L/min [31]. To minimize odor release into the room, the chamber was placed in a fume hood and vacuumed air was passed through a carbon filter. Odors (2% 2MT or 2% peppermint oil, in separate sessions) were delivered four times per session for 30 s periods with a VITI of 120–180s.

Open field test (OFT)

OFT was completed as described previously [31, 32] in a white-walled plexiglass arena (50 × 50 cm) illuminated by a white light ( ~ 200 lux). Center zone was defined as the middle 50% of the arena size. Mice were allowed to roam the arena freely for 30 min.

Elevated zero maze (EZM)

EZM was completed as described previously [31, 32] in a circular maze (Harvard Apparatus) with a 200 cm circumference comprised of four 50 cm sections (two open and two closed ‘arms’), elevated 50 cm above the floor illuminated by a white light ( ~ 25 lux). The maze path was 4 cm wide with a 0.5 cm lip on each open arm and 17 cm walls on each closed arm. Mice were positioned head-first into a closed arm and allowed to roam the maze freely for 7 min.

Tissue preparation and immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Unless otherwise stated, animals were transcardially perfused with 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) followed by 40 mL 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were dissected and post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight and then transferred to 30% sucrose solution for cryoprotection. Brains were sectioned at 30 µm on a microtome and stored in 0.1 M phosphate buffer at 4 °C prior to immunohistochemistry and tracing experiments. Immunohistochemistry was completed as described previously [29, 33, 34] (see Supplementary Methods). For behavioral cohorts, viral expression and optic fiber placements were evaluated before inclusion in the presented datasets.

Fiber photometry analysis

Fiber photometry data were analyzed as described previously [29]. In brief, custom MATLAB scripts were used to normalize signal by detrending bleaching decay and correcting for motion artifact using the isosbestic trace. Normalized traces were extracted in windows surrounding the onset of relevant behavioral events (tail lift, odor, shock, air puff, looming, open arm entry, center entry), z-scored relative to the mean and standard deviation of a 10-s baseline period preceding each event window, and then averaged.

Behavioral scoring

For foot shock and looming video recordings, behavior annotations were conducted manually by a blinded investigator to avoid bias in scoring sex differences. A trial was categorized as “freeze” if mice were immobile for at least 2 s following stimulus onset, whereas a trial was categorized as “flight” if mice fled from their original position with enhanced velocity within 5 s of stimulus onset. Trials not classified as either freeze or flight were labeled as “neither.”

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed as indicated (see Supplementary Methods) in GraphPad Prism 9 and MATLAB 9.9 (MathWorks). For spontaneous behaviors where experimenters did not control the timing of each trial (open field test, elevated zero maze), any trials that occurred less than 10 s after a directly preceding trial were removed to prevent signal contamination within the baseline period. No other data were excluded from analyses. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM unless otherwise specified.

Results

pnVTAPNOC neurons exhibit sustained activity throughout acute stress exposure across multiple stress conditions

N/OFQ-containing neurons in the pnVTA (pnVTAPNOC neurons) act to suppress motivated behaviors. Stress is also known to disrupt motivation, but despite evidence linking N/OFQ with stress, the impact of stress on the activity of this population remains unknown. Importantly, the effects of stress exposure on motivation can vary depending on the form and duration of the stressor. To evaluate the effects of diverse stress conditions on pnVTAPNOC activity, we injected PNOC-Cre mice with a Cre-dependent GCaMP6s (AAV-DJ-Ef1a-DIO-GCaMP6s) and implanted optic fibers in the paranigral ventral tegmental area (pnVTA) to record the calcium activity of pnVTA N/OFQ neurons (pnVTAPNOC) during exposure to a variety of stressful stimuli (Fig. 1A, B). At 3–4 weeks post injection we detected robust, transient activation of pnVTAPNOC neurons in response to a mild foot shock (Fig. 1C–F, one-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of time F3,24 = 14.26, p < 0.0001; Tukey’s baseline vs shock p < 0.0001), a 20-s tail lift (Fig. 1G–I, one-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of time F4,44 = 10.94, p < 0.0001; Tukey’s baseline vs lift p < 0.0001), and a brief 0.1 s air puff delivered to the whiskers (Fig. 1J–L, one-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of time F2,16 = 18.05, p < 0.0001; Tukey’s baseline vs puff p < 0.0001).

A Fiber photometry schematic and cartoon of DIO-GCaMP6s (GCaMP6s) viral injection and fiber implant in the pnVTA of PNOC-Cre mice. B Representative coronal image showing DAPI (blue) and GCaMP6s (green) expression in pnVTA. C Representative trace of GCaMP6s ∆F/F fluorescence throughout a cued foot shock session. Black arrows are aligned with foot shock onset. D Trial structure for a cued foot shock session (10 s tone co-terminating with 2 s 0.5 mA shock). E Left: Averaged trace of pnVTAPNOC GCaMP6s activity during epoch surrounding tone-cued foot shock, aligned to tone onset. Right: Intensity-sorted heat map of GCaMP6s fluorescence during same epoch, each row correspond to a trial in the averaged trace (left). (N = 9 mice). F Area under the curve (AUC) for averaged traces from (E), calculated over 8-s intervals surrounding cued-foot shock events. GCaMP6s signal increases in response to shock but not tone (one-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of time [F3,24 = 14.26, p < 0.0001]. Tukey’s multiple comparisons test [****p < 0.0001, ***p = 0.0003], N = 9 mice). G–I Same as (D–F) but for pnVTAPNOC GCaMP6s activity during 20 s tail lift. Activity averaged in 5-s intervals surrounding each tail lift shows increases first during tail lift and again when animal is lowered to the ground (one-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of time [F4,44 = 10.94, p < 0.0001]. Tukey’s multiple comparisons test [****p < 0.0001, ***p = 0.0002, *p = 0.0342], N = 12 mice). J–L Same as (D–F) but for pnVTAPNOC GCaMP6s activity during acute air puff (0.1 s, 20 PSI). Activity averaged in 5-s intervals surrounding each air puff (one-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of time [F2,14 = 13.99, p = 0.0005]. Tukey’s multiple comparisons test [****p < 0.0001, **p = 0.0044], N = 9 mice). All data represented as mean ± SEM.

Interestingly, pnVTAPNOC activity was time-locked with the duration of the stressor. Activity returned to baseline levels following the offset of the 2 s foot shock (Fig. 1F, Tukey’s baseline vs post-stimuli p = 0.8908) or 0.1 s air puff (Fig. 1L, Tukey’s baseline vs post-stimulus p = 0.1113) but remained elevated throughout the 20 s tail suspension (Fig. 1I, Tukey’s baseline vs during p = 0.0275). Across these stressors we did not detect sex-dependent effects on pnVTAPNOC activity during stress (Supplementary Fig. 1A–C, two-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of sex, foot shock: F1,7 = 2.699, p = 0.1444; tail lift: F1,10 = 0.8557, p = 0.3767; air puff: F1,7 = 0.2339, p = 0.6434), although foot shock did elicit a larger response in females (Supplementary Fig. 1A, two-way repeated-measures ANOVA interaction between time and sex F3,21 = 5.505, p = 0.006; Tukey’s shock male vs female p = 0.0003). Notably, pnVTAPNOC neurons were not activated in response to the 10-s tone that preceded each foot shock (Fig. 1E, F, Tukey’s baseline vs. tone p = 0.9993), suggesting that pnVTAPNOC neurons have selective sensitivity to stress rather than simply responding indiscriminately to any salient stimuli.

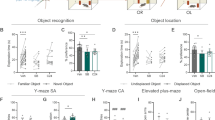

Stressful environmental cues elicit pnVTAPNOC neuron activation during exploration

We next evaluated pnVTAPNOC dynamics during innately anxiogenic exploratory behaviors (Fig. 2A). In the open field test (OFT), we detected a significant increase in calcium activity as animals transitioned from the ‘safe’ edge of the arena to the open, ‘risky’ center (Fig. 2B, D, one-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of time F2,30 = 16.18, p < 0.0001; Tukey’s baseline vs center entry p < 0.0001). We observed a similar increase in the elevated zero maze (EZM) as animals entered the unprotected open arms of the maze (Fig. 2C, E, one-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of time F2,30 = 6.305, p = 0.0052; Tukey’s baseline vs open arm entry p = 0.007). No sex-dependent effects were identified in either OFT or EZM (Supplementary Fig. 1D, E, two-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of sex, OFT: F1,14 = 0.0007, p = 0.9794; EZM: F1,14 = 1.058, p = 0.3212). These findings demonstrate that pnVTAPNOC neurons are also engaged by innately stressful environmental stimuli. Taken together, our results indicate that multiple forms of acute stress elicit robust activation of N/OFQ-containing pnVTA neurons.

A Cartoon of DIO-GCaMP6s (GCaMP6s) injection and fiber implant into pnVTA of PNOC-Cre mice. GCaMP6s activity was recorded during open field test (OFT) and elevated zero maze (EZM). B Left: Averaged traces of pnVTAPNOC GCaMP6s activity during high-anxiety epochs of the OFT, aligned to entries into the center zone of the open field arena. Right: Area under the curve (AUC) for averaged traces (left) calculated over 5-s intervals surrounding center zone entry. GCaMP6s activity increases during and immediately after center entry (one-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of time [F2,30 = 16.18, p < 0.0001]. Tukey’s multiple comparisons test [****p < 0.0001, **p = 0.0011], N = 16 mice). C Same as (B) but for pnVTAPNOC GCaMP6s activity during high-anxiety epochs of the EZM, aligned to entries into either open arm of the maze (one-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of time [F2,30 = 6.305, p = 0.0052]. Tukey’s multiple comparisons test [**p = 0.007, *p = 0.0233], N = 16 mice). D Heat map from a representative animal showing proportion of time spent in each area of the open field arena. Heat map shows more time spent around the edge than in the center. E Same as (D) but showing proportion of time spent in each area of the elevated zero maze. Heat map shows more time spent in the closed arms than in the open arms. All data represented as mean ± SEM.

Predator odor stress engages pnVTAPNOC neurons in both sexes, while predator looming stress elicits responses only in males

We further characterized the stress sensitivity of pnVTAPNOC neurons by recording calcium activity following different predatory stressors (Fig. 3A). When exposed to a looming stimulus that mimics the threat of an overhead predator, male mice displayed a significant increase in pnVTAPNOC calcium activity while females did not (Fig. 3B,C, two-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of sex F1,13 = 8.796, p = 0.0109; Tukey’s male baseline vs loom p = 0.0004, female baseline vs loom p = 0.9979).

A Cartoon of DIO-GCaMP6s (GCaMP6s) injection and fiber implant into pnVTA of PNOC-Cre mice. GCaMP6s activity was recorded during looming or exposure to predator odor. B Averaged traces of pnVTAPNOC GCaMP6s activity for males (blue, N = 5 mice) and females (magenta, N = 7 mice) aligned to looming onset. C Area under the curve (AUC) for averaged traces from B for females (left, magenta) and males (right, blue), calculated over 5-s intervals. GCaMP6s activity increases during and immediately after looming in males, but not females (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of time [F2,26 = 9.383, p = 0.0009], main effect of sex [F1,13 = 8.796, p = 0.0109], interaction of time x sex [F2,26 = 4.728, p = 0.0177]. Tukey’s multiple comparisons test [***p = 0.0004, **p = 0.0027], N = 8 males, 7 females). D Left: Averaged traces of pnVTAPNOC GCaMP6s activity surrounding 30-s exposure to either predator odor (2% 2MT, green) or a control non-predator odor (2% peppermint oil, blue). Right: Intensity-sorted heat map of GCaMP6s fluorescence during same epoch, each row correspond to a trial in the averaged trace (left). (N = 10 mice). E AUC for averaged traces from D calculated over 10-s intervals surrounding exposure to either the 2MT predator odor (left, green) or the peppermint oil (right, blue). pnVTAPNOC GCaMP6s activity increases during 2MT but not peppermint oil exposure (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of time [F4,72 = 6.173, p = 0.0003], main effect of odor [F1,18 = 4.896, p = 0.0401], interaction of time x odor [F4,72 = 4.041, p = 0.0052]. Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, 2MT over time [****p < 0.0001, **p = 0.0032], 2MT vs peppermint [**p = 0.0025, *p = 0.0419], N = 10 mice per group). All data represented as mean ± SEM.

We also assessed pnVTAPNOC calcium activity dynamics in response to an aversive predator odor (2% 2MT, a predator urine derivative [35]) and a non-aversive novel odor (2% peppermint oil), which served as a control for salience (Fig. 3D). The aversive 2MT predator odor evoked a robust, sustained increase in calcium activity, whereas the non-aversive peppermint odor elicited no response (Fig. 3E, 2MT: one-way repeated-measures ANOVA F4,36 = 6.007, p = 0.0008; peppermint oil: one-way repeated-measures ANOVA F4,36 = 0.5098, p = 0.7288). These data are consistent with our initial findings that pnVTAPNOC neurons are selectively activated by stressful stimuli and reveal a potential sex-dependent circuit level effect in response to certain predatory stressors, in male mice.

Threat-response strategies were similar between male and female mice, but female mice spent more time freezing after looming

During foot shock, all mice of both sexes employed a ‘flight’ escape response following the onset of the shock (Fig. 4A, 100% flight response, SD = 0, N = 4 males, 5 females). Males and females also had similar latencies to initiation of the flight behavior, although there was a slight but non-significant trend toward faster response time in females (Fig. 4B, two-tailed Mann–Whitney test, p = 0.0635). There were no detectable sex-dependent differences in behavioral response during the cue period that preceded each foot shock trial (Supplementary Fig. 2, two-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of sex on behavioral response F1,21 = 0.000, p > 0.999; two-tailed Mann Whitney test on time spent freezing to tone, males vs females p = 0.1905). These results suggest that the sex-dependent difference in pnVTAPNOC potentiation during shock is not accompanied by notable differences in behavior between males and females.

A Percentage of total shock trials (10 per session) where each male (blue, square) or female (magenta, circle) mouse showed behavioral responses categorized as either freeze, flight, or neither during foot shock (100% flight response, SD = 0 for all behavior types. N = 5 females, 4 males). B Trial averaged latency to flight response following foot shock (two-tailed Mann–Whitney test, males vs females p = 0.0635, N = 5 females, 4 males). C Percentage of total looming trials (4 per session) where each male (blue, square) or female (magenta, circle) mouse showed behavioral responses categorized as either freeze, flight, or neither during the loom (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of behavior [F2,39 = 5.457, p = 0.0081], main effect of sex [F1,39 = 0.000, p > 0.9999], interaction of behavior x sex [F2,39 = 0.9989, p = 0.3775]. Tukey’s multiple comparisons test male vs female in behavior type neither: [p = 0.2586], freeze: [p = 0.4956], and flight: [p = 0.6491]. N = 7 females, 8 males). D Trial averaged time spent freezing in the 10-s window beginning at loom onset for animals that had a freeze response to looming (two-tailed Mann–Whitney test, males vs females p = 0.0079, N = 5 females, 5 males). All data represented as mean ± SEM.

During looming stress, although mice had more overall variation in which strategy they employed in response to the stressor, there were similar proportions of male and female mice that opted for flight, freeze, or neither strategy (Fig. 4C, two-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of sex on behavioral response F1,39 = 0.000, p > 0.999;). During looming, the primary difference in pnVTAPNOC signal between sexes was detected during the first 10 s after the loom. Since freezing was the more prevalent threat-response for this behavior compared to flight, we quantified the total time each sex spent freezing during this 10-s time period (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, female mice spent more time freezing during this time window compared to male mice (Fig. 4D, two-tailed Mann Whitney test on time spent freezing to loom, males vs females p = 0.0079). These findings indicate that the lack of pnVTAPNOC activity we observed during looming in females but not males is accompanied by a sex-dependent difference in freezing behavior.

pnVTAPNOC activation does not sensitize to repeated stress exposure across an acute exposure session

Since we observed differences in the magnitude of pnVTAPNOC activity across different types of stressors, we next examined whether activation of these neurons became sensitized by repeated exposure to the same stressor. For each of the experimentally-evoked stressful stimuli that we tested (foot shock, tail lift, air puff, predator odor, and looming), mice experienced multiple presentations of the stressor within a single experimental session. For each of these stress types, we divided each experimental session into three time periods, early, mid, and late, and then evaluated pnVTAPNOC activity during trials that occurred within each time period (Fig. 5).

A Left: Averaged traces of pnVTAPNOC GCaMP6s activity during epoch surrounding tone-cued foot shock, aligned to tone onset. Trials were grouped by when they occurred during the session, with early trials (light green) in the first third, mid trials (medium green) in the second third, and late trials (dark green) occurring in the final third of the session. Right: Area under the curve (AUC) for averaged traces from left panel, calculated over the 8-s window following foot shock. AUC was similar across early, mid, and late trials (one-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of time F2,16 = 2.403, p = 0.1223. Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, ns = non-significant. N = 9 mice). B–F Same as (A) but for pnVTAPNOC GCaMP6s activity during B 20 s tail lift (one-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of time F2,22 = 1.803, p = 0.1884. Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, ns = non-significant. N = 12 mice), C 0.1 s air puff (one-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of time F2,16 = 0.5601, p = 0.5820. Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, ns = non-significant. N = 9 mice), D predator odor (one-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of time F2,18 = 0.4393, p = 0.6512. Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, ns = non-significant. N = 10 mice), E looming in male mice (one-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of time F2,14 = 0.4527, p = 0.6449. Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, ns = non-significant. N = 8 mice), and F looming in female mice (one-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of time F2,12 = 1.180, p = 0.3405. Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, ns = non-significant. N = 7 mice). For data in (B–F), AUC was calculated over the 5-s window following stress exposure onset. All data represented as mean ± SEM.

We found that the magnitude of pnVTAPNOC neuron responses remained consistent across early, mid, and late trials for all tested stressors, including tone-cued foot shock (Fig. 5A, one-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of time F2,16 = 2.403, p = 0.1223), 20 s tail lift (Fig. 5B, one-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of time F2,22 = 1.803, p = 0.1884), 0.1 s air puff (Fig. 5C, one-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of time F2,16 = 0.5601, p = 0.5820), predator odor (Fig. 5D, one-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of time F2,18 = 0.4393, p = 0.6512), and looming (Fig. 5E, F, one-way repeated-measures ANOVA main effect of time males: [F2,14 = 0.4527, p = 0.6449], females: [F2,12 = 1.180, p = 0.3405]). In conclusion, these findings indicate that pnVTAPNOC activation is stable across repeated exposure to a given stressor occurring within an acute ( < 30 min) time frame.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to characterize how stress exposure impacts pnVTAPNOC neuron activity. We demonstrate that pnVTAPNOC neurons are selectively activated in response to stress rather than salience in a primarily non-sex-dependent manner, except during looming predator stress where activity increased in males only. Our findings reveal new insights into a pathway by which stress interfaces with a neuropeptide subpopulation known to direct motivated reward-seeking behaviors through its influence on mesolimbic circuitry. We also show that pnVTAPNOC neurons do not sensitize with acute, repeated exposure to the same stressor, but do have varying sensitivity to different stressors, with physical and predator-based stimuli producing a larger dynamic response than the innately stressful environmental cues experienced during exploratory behaviors. Whether these differences in dynamics are related to the perceived valence of the stressful stimulus will be an important follow-up for further study.

In this study we recorded changes in calcium activity via GCaMP6s fluorescence as a proxy for pnVTAPNOC neuron activity. It is important to note that although calcium activity can serve as an indirect measure of neuron activity, our recordings do not directly measure N/OFQ release within the VTA and therefore do not necessarily reflect recruitment of endogenous N/OFQ signaling. The recent development of biosensors specific to a wide array of neuromodulators and neuropeptides, including a sensor for N/OFQ [29], have opened up new avenues for direct detection of neuromodulator release and should be used in future studies to examine N/OFQ dynamics during the stress response within the pnVTA neuronal population.

Although the looming behavior was not formally cued, the timing of signal onset in pnVTAPNOC neurons slightly precedes the initiation of the looming trial (Fig. 2B). This suggests that the mice may have detected inadvertent environmental cues (e.g. movement of the researcher to initiate a trial) in anticipation of the upcoming loom trial, which is a limitation to consider when interpreting the temporal precision of this specific behavior.

N/OFQ has been implicated in the stress response, but the observed effects of stress on the N/OFQ-NOPR system vary widely both across the brain and depending on the form and duration of stress exposure [28, 36]. Prior studies have also reported notable sex differences in rats, where stress-induced changes to N/OFQ expression were more prominent in males [37, 38]. While most of the stressors we evaluated in this study evoked similar pnVTAPNOC responses in males and females, the activity during looming that occurred exclusively in male mice mirrors these prior findings where a stress-evoked change in N/OFQ was only seen in males. On the contrary, we observed a potentiation of pnVTAPNOC activation during foot shock in females relative to males (Supplementary Fig. 1), suggesting that sex-dependent effects on how N/OFQ neurons respond to stress can also extend to females. This potentiation during foot shock was not accompanied by any detectable behavioral differences between sexes. In contrast, the lack of pnVTAPNOC response in females during looming was accompanied by an increase in freezing time compared to males, suggesting a sex-dependent effect on the presence but not the magnitude of pnVTAPNOC activation in response to stress (Figs. 3 and 4). Given the lack of a sex-dependent difference in the behavioral response to foot shock, it would be interesting to determine whether individual heterogeneity in terms of an animal’s resilience or vulnerability to stress shapes the magnitude of pnVTAPNOC neuron response during stress exposure.

The N/OFQ-NOPR system has been closely linked with anhedonia and changes to motivated behavior (for a summary see Gavioli and Calo, 2013). It is well established that stress is a prominent factor in the pathophysiology and development of anhedonia and motivational deficits, but the specific circuit-level mechanisms by which stress alters motivated behaviors are less understood. In previous work, we reported that activation of pnVTAPNOC activity suppresses effort-based reward seeking in mice [25], suggesting a mechanism by which N/OFQ activity in this circuit may regulate motivation. Our findings in this study demonstrate that these pnVTAPNOC neurons are also sensitive to acute stress, identifying a potential pathway through which stress could suppress motivation by driving excessive activation of N/OFQ signaling in the pnVTA, and subsequent modulation of dopaminergic tone as previously demonstrated by our group [25]. Further work with specialized genetic approaches is needed to more directly test this hypothesis however, particularly in evaluating whether inhibition of pnVTAPNOC activity can improve chronic stress-induced motivation deficits, and furthermore how NOPR expressing dopamine neuron activity is impacted under these situations.

In our previous work, we found that over-activation of pnVTAPNOC neurons suppressed reward-seeking behavior in mice while pnVTAPNOC inhibition enhanced motivation [25]. This suggests that N/OFQ neuron activity may be critical for fine-tuning reward-related behavior, and imbalances in either direction of standard expression levels could drive opposing effects on motivation. Our findings here showed enhanced pnVTAPNOC activation in response to stress, thus we would predict that stress-induced activation of this population would contribute to an overall anhedonic phenotype. However, it is important to note that our findings are still limited by the selection of stressors used in this study. Given that some forms of stress exposure have also been shown to exacerbate impulsive behaviors such as drug self-administration [39, 40], further work should investigate if other forms and extended durations of stress have a suppressive effect on pnVTAPNOC activity, in addition to evaluating their effects on motivated behavior.

In conclusion, the findings we report here provide insight into how stress modulates N/OFQ neuron activity within the VTA microcircuitry. These results advance our understanding of how the N/OFQ system interfaces with both stress and motivational deficits within a single circuit, laying the groundwork for further studies to explore stress-related mechanisms for anhedonic behavior in the context of this neuropeptidergic pathway. Future research should examine the long-term effects of chronic stress on pnVTAPNOC activity and evaluate the therapeutic potential of NOPR antagonism within this circuit during motivation in models of stress-induced anhedonia.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Brown SA, Vik PW, Patterson TL, Grant I, Schuckit MA. Stress, vulnerability and adult alcohol relapse. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56:538–45.

Pittenger C, Duman RS. Stress, depression, and neuroplasticity: a convergence of mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;33:88–109.

Kosten TR, Gawin FH, Rounsaville BJ, Kleber HD. Cocaine abuse among opioid addicts: demographic and diagnostic factors in treatment. Am J Drug Alcohol Abus. 1986;12:1–16.

Steel Z, Marnane C, Iranpour C, Chey T, Jackson JW, Patel V, et al. The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis 1980–2013. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:476–93.

Szczepanik JE, Furey ML, Nugent AC, Henter ID, Zarate CA, Lejuez CW. Altered interaction with environmental reinforcers in major depressive disorder: relationship to anhedonia. Behav Res Ther. 2017;97:170–7.

Struijs SY, Lamers F, Vroling MS, Roelofs K, Spinhoven P, Penninx BWJH. Approach and avoidance tendencies in depression and anxiety disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2017;256:475–81.

Ironside M, Amemori K-I, McGrath CL, Pedersen ML, Kang MS, Amemori S, et al. Approach-Avoidance Conflict in Major Depressive Disorder: Congruent Neural Findings in Humans and Nonhuman Primates. Biol Psychiatry. 2020;87:399–408.

Whitton AE, Treadway MT, Pizzagalli DA. Reward processing dysfunction in major depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2015;28:7–12.

Meyer PJ, King CP, Ferrario CR. Motivational processes underlying substance abuse disorder. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2016;27:473–506.

Schultz W. Dopamine reward prediction-error signalling: a two-component response. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016;17:183–95.

Lammel S, Lim BK, Malenka RC. Reward and aversion in a heterogeneous midbrain dopamine system. Neuropharmacology. 2014; 76 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.03.019.

Brake WG, Zhang TY, Diorio J, Meaney MJ, Gratton A. Influence of early postnatal rearing conditions on mesocorticolimbic dopamine and behavioural responses to psychostimulants and stressors in adult rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:1863–74.

Cabib S, Puglisi-Allegra S. The mesoaccumbens dopamine in coping with stress. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:79–89.

Moore H, Rose HJ, Grace AA. Chronic cold stress reduces the spontaneous activity of ventral tegmental dopamine neurons. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2001;24:410–9.

Kirshenbaum JS, Pagliaccio D, Pizzagalli DA, Auerbach RP. Neural sensitivity following stress predicts anhedonia symptoms: a 2-year multi-wave, longitudinal study. Transl Psychiatry. 2024;14:1–9.

Pizzagalli DA, Holmes AJ, Dillon DG, Goetz EL, Birk JL, Bogdan R, et al. Reduced caudate and nucleus accumbens response to rewards in unmedicated individuals with major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:702–10.

Vidal-Ribas P, Benson B, Vitale AD, Keren H, Harrewijn A, Fox NA, et al. Bidirectional associations between stress and reward processing in children and adolescents: a longitudinal neuroimaging study. Biol Psychiatry: Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2019;4:893–901.

Lincoln SH, Pisoni A, Bondy E, Kumar P, Singleton P, Hajcak G, et al. Altered reward processing following an acute social stressor in adolescents. PLOS ONE. 2019;14:e0209361.

Lowes DC, Harris AZ. Stressed and wired: The effects of stress on the VTA circuits underlying motivated behavior. Curr Opin Endocr Metab Res. 2022;26:100388.

Bouarab C, Thompson B, Polter AM. VTA GABA neurons at the interface of stress and reward. Front Neural Circuits. 2019;13:78.

Anderegg A, Poulin J-F, Awatramani R. Molecular heterogeneity of midbrain dopaminergic neurons – moving toward single cell resolution. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:3714–26.

Morales M, Margolis EB. Ventral tegmental area: cellular heterogeneity, connectivity and behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017;18:73–85.

Perez-Bonilla P, Santiago-Colon K, Leinninger GM. Lateral hypothalamic area neuropeptides modulate ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons and feeding. Physiol Behav. 2020;223:112986.

Poulin J-F, Caronia G, Hofer C, Cui Q, Helm B, Ramakrishnan C, et al. Mapping projections of molecularly defined dopamine neuron subtypes using intersectional genetic approaches. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21:1260–71.

Parker KE, Pedersen CE, Gomez AM, Spangler SM, Walicki MC, Feng SY, et al. A paranigral VTA nociceptin circuit that constrains motivation for reward. Cell. 2019;178:653–71.e19.

Norton CS, Neal CR, Kumar S, Akil H, Watson SJ. Nociceptin/orphanin FQ and opioid receptor-like receptor mRNA expression in dopamine systems. J Comp Neurol. 2002;444:358–68.

Zheng F, Grandy DK, Johnson SW. Actions of orphanin FQ/nociceptin on rat ventral tegmental area neurons in vitro. Br J Pharm. 2002;136:1065–71.

Gavioli EC, Holanda VAD, Calo G, Ruzza C. Nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptor system blockade as an innovative strategy for increasing resilience to stress. Peptides. 2021;141:170548.

Zhou X, Stine C, Prada PO, Fusca D, Assoumou K, Dernic J, et al. Development of a genetically encoded sensor for probing endogenous nociceptin opioid peptide release. Nat Commun. 2024;15:5353.

Gordon-Fennell A, Barbakh JM, Utley MT, Singh S, Bazzino P, Gowrishankar R, et al. An open-source platform for head-fixed operant and consummatory behavior. Elife. 2023;12:e86183.

Luskin AT, Li L, Fu X, Martin MM, Barcomb K, Girven KS, et al. Heterogeneous pericoerulear neurons tune arousal and exploratory behaviours. Nature. 2025;643:437–47.

McCall JG, Siuda ER, Bhatti DL, Lawson LA, McElligott ZA, Stuber GD, et al. Locus coeruleus to basolateral amygdala noradrenergic projections promote anxiety-like behavior. Elife. 2017;6:e18247.

Al-Hasani R, McCall JG, Foshage AM, Bruchas MR. Locus coeruleus kappa-opioid receptors modulate reinstatement of cocaine place preference through a noradrenergic mechanism. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:2484–97.

Kim T, McCall JG, Jung YH, Huang X, Siuda ER, Li Y, et al. Injectable, cellular-scale optoelectronics with applications for wireless optogenetics. Science. 2013;340:211–6.

Isosaka T, Matsuo T, Yamaguchi T, Funabiki K, Nakanishi S, Kobayakawa R, et al. Htr2a-Expressing Cells in the Central Amygdala Control the Hierarchy between Innate and Learned Fear. Cell. 2015;163:1153–64.

Witkin JM, Statnick MA, Rorick-Kehn LM, Pintar JE, Ansonoff M, Chen Y, et al. The biology of Nociceptin/Orphanin FQ (N/OFQ) related to obesity, stress, anxiety, mood, and drug dependence. Pharm Ther. 2014;141:283–99.

Randesi M, Zhou Y, Mazid S, Odell SC, Gray JD, Correa da Rosa J, et al. Sex differences after chronic stress in the expression of opioid-, stress- and neuroplasticity-related genes in the rat hippocampus. Neurobiol Stress. 2018;8:33–41.

Zhang L, Chen X, Sindreu C, Lu S, Storm DR, Zweifel LS, et al. Dynamics of a hippocampal neuronal ensemble encoding trace fear memory revealed by in vivo Ca2+ imaging. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0219152.

Han X, DeBold JF, Miczek KA. Prevention and reversal of social stress-escalated cocaine self-administration in mice by intra-VTA CRFR1 antagonism. Psychopharmacology. 2017;234:2813–21.

Leonard MZ, DeBold JF, Miczek KA. Escalated cocaine “binges” in rats: enduring effects of social defeat stress or intra-VTA CRF. Psychopharmacology. 2017;234:2823–36.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Drs. Azra Suko, Dr. Selena Schrieber, and Larry Zweifel for their help with virus production, and Dr. Raaj Gowrishankar for assistance with fiber photometry analysis and interpretation. This research was supported by NIH/NIMH P50 MH119467 (MRB), NIH/NIDA F31 DA059438 (CS), NIH/NIDA P30 DA048736, and the Mallinckrodt Foundation (MRB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CS and MRB conceptualized the study and designed experiments. CS, ALP, and MRB wrote the manuscript. CS, ALP, ASA, JCJ, and SJ conducted experiments and analyzed data. CS, ALP, and DJM performed statistical analyses and visualized the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

CS and MRB declare that this research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a conflict of interest. CS was an employee of the University of Washington at the time of the study and is now an employee of the Allen Institute. ALP and DJM are employees of the University of Washington. ALP was previously an employee of the Boston Children’s Hospital. ASA, JCJ, and SJ were students at the University of Washington at the time of this study. ASA is now an employee of Dermatology and Skin Care Associates. JCJ is now an employee of the University of Minnesota. SJ was previously an employee of Fred Hutch Cancer Center and Randstad Life Sciences, and is a current student at Imperial College London. MRB is a full time employee of the University of Washington, and also a co-founder and SAB member of Neurolux, Inc, and Biosyft, LLC. Neither of these commercial relationships interact with the current study in any way shape or form, but are disclosed nonetheless.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stine, C., Pasqualini, A.L., Achanta, A.S. et al. Identification of a stress-sensitive endogenous opioid-containing neuronal population in the paranigral ventral tegmental area. Neuropsychopharmacol. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-025-02292-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-025-02292-z