Abstract

Epigenetic changes that cause dysregulated gene expression during progression of androgen-independent prostate cancer (PCa) and metastatic skeletal lesions remain elusive. Here, we explored the role of histone demethylase NO66 in the pathogenesis of PCa and bone metastasis-related skeletal lesions. Tissue and cDNA microarrays of PCa were analyzed for NO66 mRNA and protein levels. We examined the effects of gain and loss of NO66 function on cell viability, colony formation, migration, invasion, and tumor-induced skeletal lesions in femoral bone. RNAseq and ChIPseq were performed to elucidate NO66-target genes in PCa. We report that NO66 levels were upregulated in advanced primary prostate tumors compared to normal tissue or tumors with low Gleason scores. Forced expression of NO66 promoted cell survival and invasion of PCa cells; whereas, knockdown of NO66 resulted in decreased cell survival and increased sensitivity to docetaxel. NO66-overexpressing PC3 cells implanted into the femoral bone of male SCID mice caused massive bone loss and stimulation of mouse osteoclast-promoting genes, including Dickkopf1, Cathepsin K, Nf-kβ,; and Calcr, suggesting a role for NO66 in tumor growth in bone and osteoclast activity. Combined RNAseq and ChIP-seq revealed that NO66 activates the survival gene MCL1, the invasion-associated genes IGFBP5 and MMP3, the pro-oncogenic genes CTNNB1 and CCND1, and the epigenetic modifier gene KMT2A in androgen-independent PCa. Our findings uncover the role of NO66 as a key oncogenic driver in PCa, causing osteolytic lesions through upstream epigenetic regulation of key genes for survival, invasion and metastasis, and pro-osteoclastic factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metastatic and castration-resistant PCa (mCRPC) invades primarily to bones and develops focal skeletal lesions, thus resulting in severe bone pain and fragility fractures [1,2,3]. Several molecular prognostic factors regulated by epigenetic mechanisms play a key role in the recurrence and metastases of PCa and skeletal lesions [4]. Aberrant expression of histone demethylases in PCa induces expression of many genes through epigenetic mechanism to contribute to resistance to a variety of drugs and to function independently of androgen receptor signaling, thus allowing progression of mCRPC [4, 5]. Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) is a biomarker in advanced PCa, contributes to the activation of AR-target genes in mCRPC, and promotes tumor progression [6,7,8]. MLL1 (KMT2A) is highly elevated and translocated in mCRPC, and activates several oncogenes independently of AR signaling [9]. These epigenetic modifiers in PCa also regulatethe expression of growth factors and cytokines during metastasis and promoting skeletal lesions [6, 10, 11].

PCa cells invade bone tissue, proliferate, and release factors, such as transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), bone morphogenetic protein (e.g., BMP2), insulin-like growth factor (IGF), fibroblast growth factor (e.g., FGF9), receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL), and Wnt proteins, all of which are potent regulators of bone homeostasis [12,13,14]. Bone marrow stromal cells then produce pro-angiogenic factors, growth factors, and RANKL, which supports tumor growth as well as regulates osteoblast and osteoclast formation [15,16,17]. Overexpression of noggin in PC3 cells inhibits cell migration, invasion, and osteolytic lesions, indicating that BMPs play a pathological role in promoting PCa-induced skeletal lesions at metastatic sites [18, 19]. We previously reported that the histone demethylase NO66, specific for H3K4me3 and H3K36me3, inhibits osteoblasts differentiation and bone formation through regulating gene expression [20,21,22]. NO66 also acts as hydroxylase for ribosomal proteins [23]. We also showed that NO66 interacts with the polycomb proteins PHF19, EZH2, and SUZ12, and inhibits the expression of the PRC2-target genes in mouse embryonic cells [24]. These studies indicate that NO66 serves as an epigenetic regulator through histone methylation and controls chromatin activity. NO66 expression at the RNA and protein levels is upregulated in many cancers, including lung cancer, renal carcinoma, and colorectal cancer [25, 26]. However, the role of NO66 in PCa pathogenesis has not yet been reported.

We show that NO66 promotes survival and invasion of cancer cells and is highly expressed in advanced PCa tumors compared to normal or low Gleason score tumors. NO66-expressing cells implanted into mouse femurs induce severe osteolytic lesions through activation of osteoclast formation. Finally, combined RNAseq and ChIPseq experiments reveal that NO66 activates a large cohort of genes with known functions of cell survival, migration, and drug resistance during PCa progression.

Results

NO66 is highly expressed in clinical PCa samples

To study the clinical significance of NO66 in PCa, we first analyzed the expression of NO66 in patient samples using immunohistochemistry with tissue microarray. We found that NO66 was expressed in more than 70% (63 out of total 90) of the tumors analyzed with predominantly nuclear localization and its protein levels were higher in tissue from patients with advanced PCa with Gleason scores of 8–10 (Fig. 1a) than in samples with Gleason scores of 6 or 7. Negative staining for NO66 was shown in samples with a Gleason score of 6. As shown in Fig. 1b, the percentage of PCa specimens with high immunostaining intensity for nuclear NO66 increased for samples with higher Gleason scores (p = 0.0168, chi-square, df = 12.08, 4) suggesting a role for NO66 in advanced stages of PCa. Using protein and RNA arrays, we also observed that NO66 protein levels are higher in lung, colon, pancreas, and prostate tumors, but lower in melanoma tumors than in healthy tissue (Fig. 1c). NO66 mRNA levels were higher in primary prostate tumors than in healthy prostate tissue (Fig. 1d). Independent public data set from TCGA and the Oncomine database indicate genomic alteration (deletion or amplification) of the NO66 gene in a subset of prostate adenocarcinoma (Fig. 1e) and that NO66 levels in PCa tumors associates with patient poor overall survival (Fig. 1f).

Expression of NO66 in subset of patient specimens. a Immunohistochemistry analysis with NO66-specific antibody in PCa patient samples. Representative images with ×10 ×and 20 magnification are shown with negative, medium, and high staining with Gleason Scores. b Quantification of NO66 expression in tissue microarray. c Dot blot showing levels of NO66 in normal and tumor lysate dot array, and d mRNA levels of NO66 in patient samples using cDNA array plate. e Genomic alteration of NO66 in interrogated database (Cbio.portal.org). f Interrogated TCGA data for the NO66 levels in survival analysis of PCa patients (https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000170468-RIOX1/pathology/tissue/prostate+cancer)

NO66 knockdown inhibits cell survival and potentiates docetaxel-induced cytotoxicity

To investigate NO66 function in PCa cell survival, we knocked-down NO66 levels in an androgen-independent (AI) DU145 cell line by lentivirus NO66 shRNAs (DU-sh) and control shRNA (DU-Nsh). Knockdown efficiency was confirmed by measuring the NO66 mRNA levels in those shRNA-expressing clones (Fig. 2a). With clonogenic and MTT assays, we showed that NO66 depletion led to the formation of fewer colonies in DU-sh1 and DU-sh2 than control (DU-Nsh) cells and also decreased cell survival in shRNA-expressing cells (Fig. 2b, c). In addition, the invasive and migration abilities of NO66-depleted cells were also reduced as analyzed by Boyden chamber assay (Suppl. Figure 1). Docetaxel has been an important treatment option for patients with metastatic CRPC, but nearly all patients eventually develop resistance. To determine whether NO66 alters docetaxel sensitivity, we examined the sensitivity of NO66-depleted DU145 cells to docetaxel-induced cytotoxicity. Indeed, DU-NO66sh cells were more sensitive to docetaxel-induced cell death than DU-Nsh cells, as shown by an MTT assay (Fig. 2d). Furthermore, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) showed that the fraction of subG1 population was increased in NO66-depleted cells (54%) treated with 4 nM docetaxel when compared with control cells treated with docetaxel (24%) (Fig. 2e), suggesting that NO66 expression may cause resistance to docetaxel. Additionally, levels of cleaved PARP increased in NO66-depleted cells compared to control cells, when treated with docetaxel (Fig. 2f). We next tested the level of expression of known candidate genes involved in apoptosis. The expression levels of BBC3, CASP2, PLAUR, and PUMA genes were significantly upregulated in DU-sh1 and DU-sh2 cells (Fig. 2g). We then reproduced the oncogenic role of NO66 in another AI cell line, PC3, in which NO66 was depleted by lenti-shRNA (Fig. 2h). Based on clonogenic and soft agar assays, NO66 depletion decreased both the size and number of colonies (Fig. 2i, j), which suggests a role for NO66 in cellular transformation.

Knockdown of NO66 in DU145 and PC3 cells inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptotic gene expression. a NO66 mRNA levels by qRT-PCR in DU-Nsh and DU-sh clones. b Clonogenic assay with DU-Nsh and DU-sh cells (n = 3). c MTT assay for cell proliferation ability of DU-sh clones at different days. d MTT assay for docetaxel-induced toxicity in DU-Nsh (black line) and DU-sh1 cells (red line). e Cell cycle analysis by FACS of untreated and treated cells with 4 nM docetaxel, as indicated in the panel, for 24 h cells followed by staining with propidium iodide. f Western blot showing the levels of cleaved PARP in docetaxel treated cells (4 nM) using cleaved PARP antibody. g Quantitative gene expression analysis in DU-Nsh and DU-sh clones. h Western blot for NO66 levels in stably expressing NO66-shRNA clones with NO66-specific antibody. i Clonogenic assay and j Anchorage-independent growth in PC3-Nsh and PC3-sh1 cells. Error bars indicate “mean ± SEM”; P < 0.05

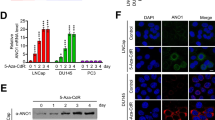

Gain of NO66 function promotes survival, migration, and invasion

In contrast to the effects of NO66 depletion in PCa cells, overexpression of NO66 in PC3 cells (Fig. 3a), NO66 increased their cell survival compared with control having vector alone (PC3-Vec) cells, as indicated with the MTT assay (Fig. 3b). With Boyden chamber assay to study the invasion and migration abilities, our data indicate that more PC3-NO66 cells than control cells migrated to the matrigel barrier (Fig. 3c, d) while NO66 depletion in DU145 cells inhibited their invasion and migration (Suppl. Figure 1). Levels of the invasion marker MMP2 were significantly increased in PC3-NO66 cells, thereby indicating that NO66 promotes invasion of PCa cells (Fig. 3a). RUNX2 levels were also increased in PC3-NO66 cells, which promotes PCa proliferation and invasion through activation of metastases-related genes [27].

Stably-expressed NO66 in PC3 cells increases their cell proliferation, invasive ability and levels of invasion markers. a Western blot analysis for the levels of NO66 in PC3 cells expressing FlagNO66 with a Flag antibody and levels of MMP2, and RUNX2 with their respective antibodies. Vinculin serves as loading control. b MTT assay in PC3-Vec and PC3-NO66 cells. c Representative image of invaded cells through matrigel barrier. d Quantification of the invaded cells (n = 5) for (c). Error bars indicate “mean ± SEM”; P < 0.001

Transcriptome analysis of the NO66-target genes

To identify the NO66-target genes, we performed RNAseq-based transcriptome analysis of DU-Nsh cells and three DU-sh clones (sh1, 2, and 3). We identified a total of 32 differentially expressed genes; 18 genes were down-regulated, and 14 genes were upregulated (Table 1) in all three shRNA clones compared to control cells. Among the genes with low expression in all DU-sh clones, IGFBP5, AKR1C3, CEMIP, MTRNR2L2/8/9, and S100A9 are known to play a role in the progression of various cancers, including prostatic tumors: IGFBP5 (in tumor progression), AKR1C3 (androgen synthesis in metastatic PCa [28,29,30]), CEMIP [31, 32] (tumor cell migration and proliferation), MTRNR2L2/8/9 (neuroprotective and anti-apoptotic), and S100A9 (inflammation process). Normalized expression tags for IGFBP5 and AKR1C3 were obtained by IGV (Integrated Genome Viewer, MIT) from RNAseq data (Fig. 4a). In addition, with low stringency criteria (FDR > 0.05), several other important genes with altered expression levels were identified, and a few of them were validated by quantitative RT-PCR in control cells and DU-sh1 and 2 clones (Fig. 4b). We showed that genes with oncogenic function, β-Catenin (CTNNB1), IGFBP5, MMP3, AKR1C3, CXCL5 [33], and KISS1R [34, 35], were significantly down-regulated in DU-sh cells compared to control DU-Nsh cells; whereas, genes with anti-proliferative activity, IL32 [36], ESM1 [37, 38], and RGS2 [39, 40], were remarkably upregulated in DU-sh cells. In fact, both β-catenin mRNA and protein levels were decreased in NO66-depleted (DU-sh1/2) cells compared with control DU-Nsh cells (Fig. 4b, d). Taken together, our transcriptome analysis shows that NO66 regulates expression of genes associated with proliferation, survival, and invasion in PCa.

Validation of RNAseq analysis in DU145 cells. a An IGV snapshot of transcriptome analysis for IGFBP5 and AKR1C3 genes between DU-Nsh and DU-sh clones. b, c Quantitative RT-PCR showing the mRNA levels of differentially expressed genes. Error bars indicate “mean ± SEM”; P < 0.05. d Western blot showing the levels of β-catenin in these cells as indicated above the panel

NO66 protein levels correlate with the severity of osteolytic bone lesions

To investigate the role of NO66 in the development of focal skeletal lesions by PCa in the bone, we injected PC3-NO66, PC3-sh1, and PC3-Vec cells into the distal end of the right femur of SCID mice. The left femur served as a control (with no injection of cells). The microCT analyses indicated that injection of PC3-NO66 cells caused more massive femoral bone loss than did no injection (control) or femur injected with PC3-Vec cells (Fig. 5a), however, injection of PC3-sh1 cells showed less bone loss than PC3-Vec cells. Both trabecular and cortical bones were decreased in xenografts with NO66-overexpressing cells (Fig. 5b, c, right panel). X-ray data clearly indicated that bone loss was apparently greater in the xenograft with PC3-NO66 than with control PC3-Vec cells (Fig. 5d). Bone volume and bone mineral density (BMD) were decreased in NO66-overexpressing cells compared to either control or shRNA-expressing (sh1) cells (Fig. 5e, f). We reasoned that the increased bone loss in femurs with NO66-overexpressing xenografts was most likely due to increased osteolytic activity. Fig. 6a shows that expression levels of Wnt inhibitor (Dkk1, Dickkopf1), osteoclast inducers (CtsK, Cathespin K), Nf-kβ; and Calcr (calcitonin receptor) were indeed more stimulated in the femur with PC3-NO66 xenografts. Though Nfatc levels were higher in xenograft with control and PC3-NO66 cells than in the femurs with no cells injected. We then asked whether NO66 promotes the levels of osteolytic factors. Co-culture of murine primary osteoblasts with control PC3-Vec and PC3-NO66 cells clearly showed that the expression levels of Dkk1, Nf-kβ, and Sost genes, which are inducers of osteoclasts, were strongly upregulated in primary osteoblasts (Fig. 6b). Furthermore, levels of bone forming factor, osteoprotegerin (OPG), were increased; whereas, levels of osteoclast factor, RANKL, were decreased in PC3-sh1 cells (Fig. 6c), which supports the reduced bone loss by PC-sh1 cells (Fig. 5a). These findings suggest that high levels of NO66 promote the osteolytic lesions in PCa by promoting the osteoclast activity.

NO66 induces bone lysis in xenografts. a Representative microCT of control left femur (no cell injection) and right femur of SCID mice injected with PC3-Vec, PC3-FlagNO66, or PC3-sh1 cells (n = 5, 0.5 million cells/femur) at 21 days after cell injection. b MicroCT showing the trabecular bone. c MicroCT showing cortical bone. d X-ray image taken before microCT. a, d Arrows and bracket indicate lesions. e Bone volume and f bone mineral density (BMD) in femurs with no cells control (−) and injected PC3 cells (−Vec, −NO66, and −sh1). Error bars indicate “mean ± SEM”; P < 0.05 from 5 animal per group

NO66 promotes bone loss through activation of osteolytic factors secreted from PCa cells. a Gene expression levels of mouse genes in femoral bone injected with no cells, PC3-Vec (control) cells, and PC3-FlagNO66 cells. b Gene expression levels of mouse genes in primary murine osteoblasts co-cultured with PC3-Vec and PC3-NO66 cells. Representative data of three independent experiments is shown. Error bars indicate “mean ± SEM”; P < 0.05. c Western blot analysis for levels of OPG and RANKL in lysates of PC3-Nsh and PC3-sh

Genome wide distribution of the NO66 interactions in PC3 cells by ChIP sequencing

To gain insights into the molecular mechanism of NO66 in gene activation during AI PCa, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIPseq) using NO66- and H3K9AC-specific antibodies in PC3-NO66 cells. These experiments allowed us to identify the NO66-bound genes and their activation in AI-PC3 cells. Bioinformatics analysis with the peak-calling program MACS was used to identify the NO66 peaks in the genomic loci (criteria- cutoff with p-value < 1.00E-07 and FDR <0.1). We obtained a total of 897 unique peaks corresponding to the NO66 binding throughout the genome and most of them (51%) lies at the promoter regions and rest of them lies within upstream, intronic, exon, and enhancer regions (Fig. 7a). A list of NO66 peaks distribution is provided in Suppl. Section (NO66 Peak Distribution). Interestingly, 88% of the NO66 peaks overlapped with the peaks of H3K9AC (an active histone marker) mostly in the promoter region, as shown with a heat map (Fig. 7b). Our analysis suggests that binding of NO66 at gene promoters, co-localized with H3K9AC, has a pivotal role in the activation of these genes through histone acetylation and chromatin remodeling activity.

Bioinformatics analysis for the genome wide distribution of the NO66 interactions. a Percentages of the interaction sites in the genome. b Representation via heat map for interaction sites after ChIPseq for NO66 and H3K9AC using respective antibodies. c An IGV snapshot of the peaks for NO66 and H3K9AC in target genes. d Quantitative RT-PCR for gene expression in PC3-Vec, PC3-FlagNO66, and PC3-NO66 (AKA) cells. NO66 (AKA) is a mutant for defective histone demethylase activity by substitution of catalytic histidine to alanine [20]. Error bars indicate “mean ± SEM”; P < 0.05. e ChIP analysis for the occupancy of NO66 in the chromatin of PC3-Vec and PC3-NO66 cells shows the NO66 interaction in the promoter region (Prox) and coding region (Int) of the genes DDIT3, MCL1, and CTNNB1

NO66-target genes play key roles in androgen-independent prostate cancer

Our analysis revealed that most of the genes bound with NO66 and H3K9AC play key roles in the progression and metastasis of PCa, independently of AR signaling. Fig. 7c and Suppl. Figure 2 show a snapshot of few genes including miRNAs and long non-coding RNAs with co-localization of NO66 and H3K9AC at the promoter regions. Expression levels of these genes were further validated in PC3-NO66 and PC3-Vec cells (Fig. 7d). The mRNA levels of CTNNB1, RICTOR, CCND1, DVL (Disheveled), FOXA1, and the epigenetic modifier MLL1 (KMT2A) were more induced in PC3-NO66 cells than control (PC3-Vec) cells. However, expression of a dominant negative histone demethylase mutant NO66 in PC3-NO66(AKA) cells also stimulated the transcription of these NO66-target genes, which indicates that NO66 regulates transcription of these genes independently of its histone demethylase activity (Fig. 7d). Protein levels of MLL1, EZH2, and β-Catenin were highly induced in PC3-NO66 cells, while that of CyclinD1 was only partially induced in NO66-expressing PC3 cells (Suppl. Figure 3A). Studies have shown that KMT2A, FOXA1, and RICTOR are key inducers in the progression of mCRPC [9, 41,42,43,44], while CTNNB1 promotes PCa proliferation and progression through activation of Wnt signaling [45,46,47]. The occupancy of NO66 at the close proximity of DDIT3 (ER stress gene), MCL1 (survival gene), and CTNNB1 genes was confirmed by manual ChIP PCR in NO66-expressing cells (Fig. 7e). ChIPseq analysis also revealed the NO66 binding peaks in other genes and miRNAs which are known for promoting PCa progression and metastasis (Suppl. Figure 2). These genes are EZH2, TGIF1, ANAX2R, MIR21, MIR23A, and MIR100HG in which interactions of NO66 and H3K9AC are co-localized in their promoters and have an oncogenic role during malignancies [6, 48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55]. Further, out of the 89 genes listed for the KEGG PCa pathway obtained from the IGV portal, 23 genes from our data set are included in the KEGG prostate pathway (Suppl. Table 1). We show the peaks for NO66 and H3K9AC for the corresponding genes which are present in the PCa pathway (Suppl. Figure 2). Based on Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) and DAVID GO, analysis of the NO66-target genes revealed the network of these genes converges to support cancer progression, as well as signaling pathways including Wnt/βcatenin, Notch, and TGF-β (Suppl. Table 2). We also tested the levels of NO66 in androgen-sensitive C42B cells treated with androgen analog (R1881). At the lower dose of R1881 (1 nM), an induction in NO66 and AR levels was observed, but the higher concentration of R1881 had an inhibitory effect (Suppl. Figure 3B). Indeed, R1881 stimulated the mRNA levels of NO66 in C42B cells (Suppl. Figure 3C), suggesting a role of NO66 in AR-dependent progression of PCa. Consistent with other reports on the role of NO66 in colorectal and lung cancers, our findings support the oncogenic role of NO66 in PCa and induction of skeletal lesions through activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and epigenetic modifiers, including MLL1.

Discussion

In this study, we present several lines of evidence that NO66 promotes PCa cell proliferation and migration, and skeletal osteolytic lesions through activation of expression of genes associated with cell survival, invasiveness, and osteoclast activation. We also show that NO66 is upregulated in high-grade tumors compared to low-grade tumors and normal tissues.

Expression of NO66 has recently been reported in small cell lung cancer, colorectal cancer, and renal carcinoma [25, 26, 56]; however, the mechanisms of NO66 function in these cancers and its role in PCa are unknown. A positive correlation between NO66 levels and tumors with high Gleason scores suggests a clinical significance for NO66 in PCa progression. Aberrant expression of histone demethylases, including KDM1A, KDM5/6A, and JMJD2A has a pro-oncogenic role through deregulation of gene expression in various cancers [4, 5, 57, 58]. Our findings, including RNAseq-based transcriptome and ChIPseq analyses, support a pro-oncogenic and anti-apoptotic role for NO66 in PCa. Knockdown of NO66 decreased cell proliferation, most likely due to inhibition of expression levels of pro-oncogenic genes, including IGFBP5, MMP3, CXCL5, and β-catenin; and activation of pro-apoptotic genes, including BBC3, CASP2, and PUMA. It also appears that NO66 regulates expression of genes for androgen synthesis, since levels of AKR1C1, AKR1C2, and AKR1C3 were decreased in NO66-depleted DU145 cells. These genes are involved in androgen synthesis and promote drug resistance in CRPC [59]. Furthermore, depletion of NO66 resulted with more sensitivity to docetaxel-mediated cell toxicity, suggesting that NO66 may stimulate the expression of drug resistance genes. Indeed, interactions of NO66 with the promoter of the gene RICTOR and strong stimulation of expression of this gene in NO66-overexpressing PC3 cells corroborate a positive role for NO66 in drug resistance. Notably, RICTOR promotes cytotoxic drug resistance through the mTOR pathway in many cancers [60]. Moreover, NO66 interactions with MLL1 (KMT2A) and EZH2, as well as some miRNAs including miR21, miRNA23, and lncRNA miR100HG, which are involved in the progression and metastasis of PCa, suggest that NO66 acts as an upstream regulator of these epigenetic modifiers, which are associated with the progression of AR-independent PCa through gene activation. Taken together, our data suggest that the molecular mechanisms of the NO66 oncogenic function are via its interactions with chromatin and activation of genes for proliferation, migration, and transcriptional regulation.

The pathological and clinical features of skeletal metastases from PCa include osteoblastic (bone forming) and osteoclastic (bone lysing), or mixed, lesions [61]. In animal and in vitro co-culture studies, we demonstrated that NO66 expression promoted massive osteolytic lesions and increased expression levels of osteoclastic genes (DKK1, Ctsk, and Nf-kβ), thereby supporting a role for NO66 in the secretion of pro-osteoclastic factors which cause osteolytic lesions in AR-independent PCa. The secretion of these factors by PCa cells allows their invasion, migration, and interactions with stromal cells in bones. Consistent with this notion, ChIPseq analysis identified several NO66-target genes, including CXCL1, CXCL2, ANAXA2R, RUNX2, and PTHLH, that regulate chemo-attraction, interaction with stroma cells, migration, and osteoclast formation.

Taken together, our findings indicate that NO66 is an epigenetic regulator of AR-independent PCa and osteolytic lesions, through controlling the expression of a cohort of downstream target genes, including oncogenes and cytokine-expressing genes that are associated with PCa progression and metastasis. Since we and others have reported on the crystal structure of NO66 [62, 63], development of small molecule inhibitors targeting NO66 may be an effective therapeutic approach for treating PCa and other malignancies. Furthermore, NO66 levels in prostatic tumors may be a useful molecular marker to predict disease stage and response of patients to chemotherapeutics.

Materials and methods

Cell culture, reagents, and antibodies

PCa cell lines PC3, DU145, and C42B (ATCC) were routinely cultured in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin and streptomycin, and periodically tested for mycoplasma contamination. NO66—a peptide polyclonal antibody was developed previously and reported by Sinha et al. [20]. Primer sequence and antibodies are described in Suppl. Section.

Generation of cell lines for NO66-shRNA and NO66-overexpression

The FlagNO66 cDNA was cloned into a pLenti-Vector (Origene, Rockville, MD, USA) and lentiviral particles were produced in HEK293T cells using packaging kit (TR30037, Origene, Rockville, MD, USA). The virus particles containing NO66-shRNA (three different shRNAs), control (scrambled) shRNA, pLenti-vector, and pLenti-FlagNO66 were transduced in PC3 or DU145 cells, and transduced cells were selected with media containing 2 μg/mL puromycin (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) for 1 week.

Cell proliferation, migration and invasion, and anchorage-independent growth assays

Cell survival/proliferation was studied with an MTT assay in a 96-well plate. Briefly, cells were cultured for the indicated time, incubated with 200 μl of 0.6 mg/ml MTT in serum-free medium for 4 h, and then further incubated in dimethyl sulfoxide for 4 h, followed by a colorimetric reading at 595 nm with a microplate reader (Biotek,VT, USA). The invasion assay was performed in Matrigel-coated transwell invasion chambers with an 8.0-μm pore size (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). For this assay, 1 × 105 cells were added into the top chamber containing 250 μl of serum-free DMEM. Another 750 μL of NIH3T3-conditioned media was added into the bottom chamber, and the cells were allowed to invade for 24 h. The cells that invaded through the filter into the bottom chamber were stained with a three-step process and counted. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, and mean values are presented. For clonogenic assays, cells were plated on 35-mm plates, stained with 0.2% crystal violet, and counted under a bright-field light microscope. Cell cycle distribution was determined by a standard procedure of propidium iodide stained cells followed by FACS analysis. Anchorage-independent colony formation assay was performed as described previously [64].

RNASeq, ChIP-Seq, and data analysis

For RNA sequencing, total RNA was isolated from DU145 cell lines, control shRNA (DU-Nsh), and three different clones of NO66-shRNA-expressing cells (DU-sh1, DU-sh2, and DU-sh3). For ChIP-Seq experiments, chromatins were prepared from PC3-NO66 cells and immunoprecipitation was done with NO66 and H3K9AC (C15410004, Diagenode, Denville, NJ, USA) antibodies as described previously by Sinha et al. [20]. Library preparation, adaptor ligation, and sequencing of RNA and DNA samples were done by the core facility at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (UTMDACC) Sequencing and Microarray Core Facility. The raw data were analyzed by bioinformaticians at UTMDACC using appropriate software programs.

Cell lysates, western blot, and quantitative gene expression

Cell extracts and Western blot were performed as described previously [20]. For gene expression analysis, total RNA was extracted with a Zymo DNAse-free RNA isolation kit (Zymo, CA, USA) and cDNA was prepared with a ViLO kit (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). Gene-specific primers were used for quantitative PCR on a StepOne Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). Details of primers are included in the Supplemental Section. Gene expression values were normalized to 18S rRNA.

Immunohistochemistry with PCa patient tissue microarray

PCa tissue microarrays obtained from US Biomax (Cat # HProA100PG02, Rockville, MD, USA) contained 90 patient samples with low to high Gleason grades, including normal prostate tissue samples. Immunohistochemsitry with NO66 antibody (1:200 dilution) was done with a standard procedure using immunoperoxidase procedure (ABC-Elite;Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The scoring of NO66 staining in the tumor sections was performed by a pathologist based on nuclear and cytoplasmic localization of NO66. We quantitated NO66 protein expression using a three-tiered scoring system as published previously [65] as follows: no detectable staining in more than 70% of tumor cell nuclei was scored as negative, 30% or more tumor cell nuclei weakly stained (discernable nucleoli) as weak, and more than 30% of nuclei strongly stained (invisible nucleoli) as strong. Normal and tumor protein blot, and cDNA arrays were purchased from Origene (Rockville, MD, USA) (Cat# CSRT101) and were used for detection of NO66 protein and mRNA levels respectively.

Xenograft studies and bone analysis

Stable cell lines, and PC3-Vec, PC3-NO66sh1, and PC3-NO66 cells (5 × 105/5 μl/femur) were injected into the distal femur of 6-week-old male SCID mice (Charles River, MA, USA) (n = 5 mice each group). At 3 weeks post-injection, micro CT and X-ray were performed on anesthetized animals and then mice were sacrificed to remove femurs for isolation of total RNA and gene expression analysis. Animal studies were performed under approved animal protocol by Institutional Animal Care and Utilization Committee of MDACC.

Statistical analysis

Bar graphs and statistical analysis were performed using GraphPad program. One way ANOVA for multiple comparison were used for p values and Student's t-test was performed for Boyden chamber assay. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant, and statistical significance was indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001. Clonogenic, boyden chamber assay, MTT, and FACS experiments were repeated at least three times. All data were expressed as means ± SEM of representative experiments.

References

Logothetis CJ, Lin SH. Osteoblasts in prostate cancer metastasis to bone. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:21–8.

Logothetis CJ, Navone NM, Lin SH. Understanding the biology of bone metastases: key to the effective treatment of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1599–602.

Akech J, Wixted JJ, Bedard K, van der Deen M, Hussain S, Guise TA, et al. Runx2 association with progression of prostate cancer in patients: mechanisms mediating bone osteolysis and osteoblastic metastatic lesions. Oncogene. 2010;29:811–21.

Crea F, Sun L, Mai A, Chiang YT, Farrar WL, Danesi R, et al. The emerging role of histone lysine demethylases in prostate cancer. Mol Cancer. 2012;11:52.

Ellinger J, Kahl P, von der Gathen J, Rogenhofer S, Heukamp LC, Gutgemann I, et al. Global levels of histone modifications predict prostate cancer recurrence. Prostate. 2010;70:61–9.

Xu K, Wu ZJ, Groner AC, He HH, Cai C, Lis RT, et al. EZH2 oncogenic activity in castration-resistant prostate cancer cells is Polycomb-independent. Science. 2012;338:1465–9.

Yang YA, Yu J. EZH2, an epigenetic driver of prostate cancer. Protein & Cell. 2013;4:331–41.

Yu J, Yu J, Rhodes DR, Tomlins SA, Cao X, Chen G, et al. A polycomb repression signature in metastatic prostate cancer predicts cancer outcome. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10657–63.

Malik R, Khan AP, Asangani IA, Cieslik M, Prensner JR, Wang X, et al. Targeting the MLL complex in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nat Med. 2015;21:344–52.

Saha B, Kaur P, Tsao-Wei D, Naritoku WY, Groshen S, Datar RH, et al. Unmethylated E-cadherin gene expression is significantly associated with metastatic human prostate cancer cells in bone. Prostate. 2008;68:1681–8.

Tamada H, Kitazawa R, Gohji K, Kitazawa S. Epigenetic regulation of human bone morphogenetic protein 6 gene expression in prostate cancer. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:487–96.

Li ZG, Mathew P, Yang J, Starbuck MW, Zurita AJ, Liu J, et al. Androgen receptor-negative human prostate cancer cells induce osteogenesis in mice through FGF9-mediated mechanisms. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2697–710.

Wan X, Liu J, Lu JF, Tzelepi V, Yang J, Starbuck MW, et al. Activation of beta-catenin signaling in androgen receptor-negative prostate cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:726–36.

Lee YC, Cheng CJ, Bilen MA, Lu JF, Satcher RL, Yu-Lee LY, et al. BMP4 promotes prostate tumor growth in bone through osteogenesis. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5194–203.

Liu XH, Kirschenbaum A, Yao S, Liu G, Aaronson SA, Levine AC. Androgen-induced Wnt signaling in preosteoblasts promotes the growth of MDA-PCa-2b human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5747–53.

Zhou HJ, Yan J, Luo W, Ayala G, Lin SH, Erdem H, et al. SRC-3 is required for prostate cancer cell proliferation and survival. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7976–83.

Verras M, Sun Z. Roles and regulation of Wnt signaling and beta-catenin in prostate cancer. Cancer Lett. 2006;237:22–32.

Feeley BT, Krenek L, Liu N, Hsu WK, Gamradt SC, Schwarz EM, et al. Overexpression of noggin inhibits BMP-mediated growth of osteolytic prostate cancer lesions. Bone. 2006;38:154–66.

Feeley BT, Gamradt SC, Hsu WK, Liu N, Krenek L, Robbins P, et al. Influence of BMPs on the formation of osteoblastic lesions in metastatic prostate cancer. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:2189–99.

Sinha KM, Yasuda H, Coombes MM, Dent SY, de Crombrugghe B. Regulation of the osteoblast-specific transcription factor Osterix by NO66, a Jumonji family histone demethylase. EMBO J. 2010;29:68–79.

Sinha KM, Zhou X. Genetic and molecular control of osterix in skeletal formation. J Cell Biochem. 2013;114:975–84.

Sinha KM, Yasuda H, Zhou X, deCrombrugghe B. Osterix and NO66 histone demethylase control the chromatin of Osterix target genes during osteoblast differentiation. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:855–65.

Ge W, Wolf A, Feng T, Ho CH, Sekirnik R, Zayer A, et al. Oxygenase-catalyzed ribosome hydroxylation occurs in prokaryotes and humans. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:960–2.

Brien GL, Gambero G, O’Connell DJ, Jerman E, Turner SA, Egan CM, et al. Polycomb PHF19 binds H3K36me3 and recruits PRC2 and demethylase NO66 to embryonic stem cell genes during differentiation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:1273–81.

Pires-Luis AS, Vieira-Coimbra M, Vieira FQ, Costa-Pinheiro P, Silva-Santos R, Dias PC, et al. Expression of histone methyltransferases as novel biomarkers for renal cell tumor diagnosis and prognostication. Epigenetics. 2015;10:1033–43.

Nishizawa Y, Nishida N, Konno M, Kawamoto K, Asai A, Koseki J, et al. Clinical significance of histone demethylase NO66 in invasive colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:841–9.

Ge C, Zhao G, Li Y, Li H, Zhao X, Pannone G, et al. Role of Runx2 phosphorylation in prostate cancer and association with metastatic disease. Oncogene. 2016;35:366–76.

Yepuru M, Wu Z, Kulkarni A, Yin F, Barrett CM, Kim J, et al. Steroidogenic enzyme AKR1C3 is a novel androgen receptor-selective coactivator that promotes prostate cancer growth. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:5613–25.

Adeniji AO, Chen M, Penning TM. AKR1C3 as a target in castrate resistant prostate cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2013;137:136–49.

Zeng CM, Chang LL, Ying MD, Cao J, He QJ, Zhu H, et al. Aldo-keto reductase AKR1C1-AKR1C4: functions, regulation, and intervention for anti-cancer therapy. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:119.

Liang G, Fang X, Yang Y, Song Y. Silencing of CEMIP suppresses Wnt/beta-catenin/Snail signaling transduction and inhibits EMT program of colorectal cancer cells. Acta Histochem. 2018;120:56–63.

Liang G, Fang X, Yang Y, Song Y. Knockdown of CEMIP suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells: downregulation of GRP78 and attenuation of unfolded protein response. Biochem Cell Biol. 2017;96:332–41.

Begley LA, Kasina S, Mehra R, Adsule S, Admon AJ, Lonigro RJ, et al. CXCL5 promotes prostate cancer progression. Neoplasia . 2008;10:244–54.

Ji K, Ye L, Mason MD, Jiang WG. The Kiss-1/Kiss-1R complex as a negative regulator of cell motility and cancer metastasis (Review). Int J Mol Med. 2013;32:747–54.

Wang H, Jones J, Turner T, He QP, Hardy S, Grizzle WE, et al. Clinical and biological significance of KISS1 expression in prostate cancer. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:1170–8.

Park MH, Song MJ, Cho MC, Moon DC, Yoon DY, Han SB, et al. Interleukin-32 enhances cytotoxic effect of natural killer cells to cancer cells via activation of death receptor 3. Immunology. 2012;135:63–72.

Rebollo J, Geliebter J, Reyes N. ESM-1 siRNA knockdown decreased migration and expression of CXCL3 in prostate cancer cells. Int J Biomed Sci. 2017;13:35–42.

Bettin A, Reyes I, Reyes N. Gene expression profiling of prostate cancer-associated genes identifies fibromodulin as potential novel biomarker for prostate cancer. Int J Biol Markers. 2016;31:e153–62.

Cacan E. Epigenetic regulation of RGS2 (Regulator of G-protein signaling 2) in chemoresistant ovarian cancer cells. J Chemother. 2017;29:173–8.

Wolff DW, Xie Y, Deng C, Gatalica Z, Yang M, Wang B, et al. Epigenetic repression of regulator of G-protein signaling 2 promotes androgen-independent prostate cancer cell growth. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:1521–31.

Chowdry RP, Ledet E, Ranasinghe L, Sartor AO. MLL translocation in two castration-resistant prostate cancer patients. Can J Urol. 2016;23:8483–6.

Jin HJ, Zhao JC, Ogden I, Bergan RC, Yu J. Androgen receptor-independent function of FoxA1 in prostate cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 2013;73:3725–36.

Bragina O, Njunkova N, Sergejeva S, Jarvekulg L, Kogerman P. Sonic Hedgehog pathway activity in prostate cancer. Oncol Lett. 2010;1:319–25.

Chen X, Cheng H, Pan T, Liu Y, Su Y, Ren C, et al. mTOR regulate EMT through RhoA and Rac1 pathway in prostate cancer. Mol Carcinog. 2015;54:1086–95.

Nandana S, Tripathi M, Duan P, Chu CY, Mishra R, Liu C, et al. Bone metastasis of prostate cancer can be therapeutically targeted at the TBX2-WNT signaling axis. Cancer Res. 2017;77:1331–44.

Sottnik JL, Hall CL, Zhang J, Keller ET. Wnt and Wnt inhibitors in bone metastasis. Bone Rep. 2012;1:101.

Chen G, Shukeir N, Potti A, Sircar K, Aprikian A, Goltzman D, et al. Upregulation of Wnt-1 and beta-catenin production in patients with advanced metastatic prostate carcinoma: potential pathogenetic and prognostic implications. Cancer. 2004;101:1345–56.

Xiang G, Yi Y, Weiwei H, Weiming W. TGIF1 promoted the growth and migration of cancer cells in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:9303–10.

D’Souza S, Kurihara N, Shiozawa Y, Joseph J, Taichman R, Galson DL, et al. Annexin II interactions with the annexin II receptor enhance multiple myeloma cell adhesion and growth in the bone marrow microenvironment. Blood. 2012;119:1888–96.

Cai S, Chen R, Li X, Cai Y, Ye Z, Li S, et al. Downregulation of microRNA-23a suppresses prostate cancer metastasis by targeting the PAK6-LIMK1 signaling pathway. Oncotarget. 2015;6:3904–17.

Wang Z, Wei W, Sarkar FH. miR-23a, a critical regulator of “migR“ation and metastasis in colorectal cancer. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:489–91.

Yang B, Liu Z, Ning H, Zhang K, Pan D, Ding K, et al. MicroRNA-21 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells as a novel biomarker in the diagnosis and prognosis of prostate cancer. Cancer Biomark. 2016;17:223–30.

Sheth S, Jajoo S, Kaur T, Mukherjea D, Sheehan K, Rybak LP, et al. Resveratrol reduces prostate cancer growth and metastasis by inhibiting the Akt/MicroRNA-21 pathway. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e51655.

Wang S, Ke H, Zhang H, Ma Y, Ao L, Zou L, et al. LncRNA MIR100HG promotes cell proliferation in triple-negative breast cancer through triplex formation with p27 loci. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:805.

Shang C, Zhu W, Liu T, Wang W, Huang G, Huang J, et al. Characterization of long non-coding RNA expression profiles in lymph node metastasis of early-stage cervical cancer. Oncol Rep. 2016;35:3185–97.

Suzuki C, Takahashi K, Hayama S, Ishikawa N, Kato T, Ito T, et al. Identification of Myc-associated protein with JmjC domain as a novel therapeutic target oncogene for lung cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:542–51.

Vieira FQ, Costa-Pinheiro P, Ramalho-Carvalho J, Pereira A, Menezes FD, Antunes L, et al. Deregulated expression of selected histone methylases and demethylases in prostate carcinoma. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21:51–61.

Kim TD, Jin F, Shin S, Oh S, Lightfoot SA, Grande JP, et al. Histone demethylase JMJD2A drives prostate tumorigenesis through transcription factor ETV1. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:706–20.

Stanbrough M, Bubley GJ, Ross K, Golub TR, Rubin MA, Penning TM, et al. Increased expression of genes converting adrenal androgens to testosterone in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2815–25.

Morrison Joly M, Hicks DJ, Jones B, Sanchez V, Estrada MV, Young C, et al. Rictor/mTORC2 drives progression and therapeutic resistance of HER2-Amplified breast cancers. Cancer Res. 2016;76:4752–64.

Ortiz A, Lin SH. Osteolytic and osteoblastic bone metastases: two extremes of the same spectrum? Recent Results Cancer Res Fortschr der Krebsforsch Progres dans Les Rech sur Le Cancer. 2012;192:225–33.

Tao Y, Wu M, Zhou X, Yin W, Hu B, de Crombrugghe B, et al. Structural insights into histone demethylase NO66 in interaction with osteoblast-specific transcription factor osterix and gene repression. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:16430–7.

Chowdhury R, Sekirnik R, Brissett NC, Krojer T, Ho CH, Ng SS, et al. Ribosomal oxygenases are structurally conserved from prokaryotes to humans. Nature. 2014;510:422–6.

Bagheri-Yarmand R, Mandal M, Taludker AH, Wang RA, Vadlamudi RK, Kung HJ, et al. Etk/Bmx tyrosine kinase activates Pak1 and regulates tumorigenicity of breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:29403–9.

Theurillat JP, Udeshi ND, Errington WJ, Svinkina T, Baca SC, Pop M, et al. Prostate cancer. Ubiquitylome analysis identifies dysregulation of effector substrates in SPOP-mutant prostate cancer. Science. 2014;346:85–9.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Mary A. Hall for editorial assistance, Ling Zhong for microscopy, and Jun Yang for technical assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant P50 CA140388 (NCI-SPORE- Developmental Research Program) to CL and KMS, Center for Epigenetics at MDACC allowance for Next-Gen sequencing to KMS, the Bone Diseases Program of Texas to RFG, and by UTHealth startup funding to JH.

Author’s contribution

KMS and RB-Y designed and performed experiments, analyzed data and wrote manuscript. YL performed bioinformatics analysis, MZ conducted histological analysis; SA performed histology; SL and YR provided technical assistance for experiments; NN and XW for cell lines and animal studies; BO, CL, RFG, and JH for administrative and material support; KMS, RB-Y, BO, and JH discussed and reviewed the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sinha, K.M., Bagheri-Yarmand, R., Lahiri, S. et al. Oncogenic and osteolytic functions of histone demethylase NO66 in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Oncogene 38, 5038–5049 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-019-0774-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-019-0774-x

This article is cited by

-

Promoter hypermethylation as a novel regulator of ANO1 expression and function in prostate cancer bone metastasis

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Recent Advances and Therapeutic Implications of 2-Oxoglutarate-Dependent Dioxygenases in Ischemic Stroke

Molecular Neurobiology (2024)

-

A transcriptomic signature for prostate cancer relapse prediction identified from the differentially expressed genes between TP53 mutant and wild-type tumors

Scientific Reports (2022)