Abstract

Study design

Cross-sectional analysis from the Inception Cohort of the Swiss Spinal Cord Injury Study (SwiSCI).

Objectives

To describe five lifestyle components in newly injured individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI), explore co-occurrence of these components, and identify associated personal and clinical factors.

Settings

Initial rehabilitation stay following traumatic and non-traumatic SCI.

Methods

Lifestyle components including overweight/obesity, low diet score, physical inactivity, smoking, and alcohol consumption were used independently and to calculate a composite lifestyle score. Analyses were conducted using descriptive statistics, co-occurrence analysis, and multivariate logistic regression.

Results

We included 251 individuals, of whom 77.7% were male, 73.7% suffered from traumatic SCI, and 59.8% had paraplegia. The median age was 51 years (IQR 36–64). Approximately twelve weeks after the injury, more than two-thirds of the study population met the criteria for overweight/obesity, and consumed insufficient amounts of fruits and vegetables, and excessive amounts of meat. Alcohol was consumed by 85.3% of individuals, and 26.8% were current smokers. Almost all study participants met the physical activity guidelines (90 min of moderate to strenuous activity physical activity per week). One-quarter of study participants experienced the co-occurrence of overweight/obesity, low diet score and alcohol consumption. Female sex, younger age and higher education were associated with healthier lifestyle components.

Conclusion

Despite methodological limitations, this study underscores the complexities of healthy lifestyle adherence among individuals newly injured with SCI. It highlights the necessity of improving and implementing screening strategies throughout the continuum of SCI care as early as possible following the trauma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Increased cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk after spinal cord injury (SCI) is often attributed to a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome (MetS) that develops as a consequence of a mismatch between daily energy intake and energy expenditure [1]. MetS comprises central obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, low plasma high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), hypertension, and hyperglycemia [1]. When three or more of the above-mentioned components are present together, they enhance the formation of atherosclerotic plaque and premature CVD development and may represent the same clinical threat as type 2 diabetes (T2D) or an existing coronary artery disease [2]. Physical deconditioning and a hypercaloric diet, although not included in MetS components, together with prolonged oxidative and inflammatory stress, are the major underlying factors that contribute to the development of insulin resistance, hypertension and dyslipidemia following the injury [1, 3, 4].

CVD prevention remains a challenge since the most of predisposing factors are non-modifiable (e.g., sex, ethnicity, and genetic predisposition) [5,6,7]. Lifestyle interventions, such as continued nutritional guidance, moderate to strenuous intensity exercise and structured behavioral retraining, are among the most important modifiable risk factors and represent the most promising strategies in CVD prevention [8, 9]. Research in SCI population has mainly focused on single lifestyle components and their health benefits in chronic SCI [10,11,12,13,14] and only a limited number of studies addressed lifestyle components in the early injury phase [15,16,17,18,19]. Cardiometabolic disease burden was already high within months post-injury [20,21,22]. In a recent study, at discharge from initial rehabilitation stay around 40% of study participants met criteria for MetS and around one third were classified as presenting a moderate to high risk for a first CVD event over the next 10 years [20, 21]. Recent guidelines of the Association of the Scientific Medical Societies (AWMF) argue that the initiation of early clinical intervention is central and that patients should already be educated with regards to preventive behaviors during their first rehabilitation [23]. The health benefits of healthy lifestyle go far beyond cardiometabolic disease risk improvement and were linked with improved immune system function, skin, bone and gastrointestinal health, and overall wellbeing [24,25,26,27,28].

In the current study, we aim to describe five major lifestyle components (i.e., overweight/obesity, poor diet, alcohol intake, physical inactivity, and smoking) and explore which of them co-occur in newly injured individuals with SCI. Further, we aim to identify which personal and clinical factors associate with the above-mentioned lifestyle components.

Methods

Data source

The Inception Cohort of the Swiss Spinal Cord Injury (SwiSCI) study is a prospective multicenter study recruiting study participants in the four specialized rehabilitation centers in Switzerland (Balgrist University Hospital Zurich, REHAB Basel, Clinique Romande de Réadaptation Sion, and Swiss Paraplegic Center Nottwil) [29]. A wide range of demographic, biopsychosocial, and clinical parameters, as well as biological samples are collected from persons newly diagnosed with traumatic or non-traumatic SCI. The assessments were made at multiple time-points during initial rehabilitation stay (~28 days, ~84 days, ~168 days and around discharge) and one-year post-injury [29]. Participants completing assessments in the Inception Cohort are subsequently followed up in the SwiSCI community survey, which takes place every 5 years. Using May 2020 as a cut-off date, all participants from the Inception Cohort discharged ≥ 2 years ago from the initial rehabilitation were invited to participate in the Community Survey 2022 which is a community-based arm of the SwiSCI study. The current study relies on data collected during the second assessment of the Inception Cohort (approximately 84 days or 12 weeks post-injury, during the initial rehabilitation stay). Unfortunately, due to missing repeated data on lifestyle components longitudinal study was not possible.

Study population

The present study considered adult individuals (aged ≥18 years) residing in Switzerland, who were newly diagnosed with traumatic or non-traumatic SCI and had undergone their first inpatient rehabilitation since the start of the SwiSCI study (May 2013) until March 2024. Individuals lacking information on injury characteristics, individuals with neoplastic non-traumatic SCI, and those with missing information on lifestyle components were removed from the study (see Fig. 1).

Study measures

Characteristics of study participants

Clinical and demographic characteristics (i.e., age, sex, years of education) were derived from patients’ medical records. SCI characteristics included SCI etiology (i.e., traumatic versus non-traumatic), causes of injury, and level and completeness of the injury. The level of injury was classified as tetraplegia (level C2–C8) and paraplegia (level T1–S5), and the completeness of injury as motor complete (AIS A and B) and motor incomplete injury (AIS C, D and E), based on the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (ISNCSCI) [30]. The third version of the Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM III) was used to describe activity limitations [31]. The total score ranges from 0 to 100 with a lower score indicating greater activity limitations and less physical independence.

Lifestyle components

Waist circumference was measured after bowel care, at the end of normal expiration, approximately between the lower edge of the last palpable rib and the top of the iliac crest. It was measured using a flexible tape measure to an accuracy of 0.5 cm. Weight was measured using an electric scale. The weight of the wheelchair was subtracted from the participant’s total weight with the wheelchair to determine the participant’s weight expressed in kilograms (kg). Both waist circumference and weight were measured once per assessment. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the standard formula [weight in kilograms/(height in meters)2] [29]. Physical activity was measured using the Physical Activity Scale for Individuals with Physical Disabilities (PASIPD) [32]. To assess dietary habits including fluid intake (L per day, excluding alcoholic beverages), fruit and vegetable intake (portions per day, 1 item on fruit intake, 1 item on vegetable intake: <1, 1–2, 3–4, ≥5), meat intake (portions per week: never, ≤1, 2–3, 4–5, 6, daily) and alcohol intake (frequency per day/week/month and quantity of alcohol intake measured with number of drinks consumed), participants answered questions adopted from the Swiss Health Survey (SHS) [33]. Smoking status, number of years of smoking and number of cigarettes per day were assessed following standardized approach proposed within the ISCoS Pulmonary function basic data set assessments. We classified individuals as with overweight/obesity as a waist circumference ≥ 86.5 cm or BMI ≥ 22 kg/m2. Based on the current Swiss nutrition recommendations of the Swiss Nutrition Society, we grouped individuals as adherent or non-adherent to current recommendation for fluid intake, fruit and vegetable intake and meat intake. A nutritional score of 0–4 points was calculated; adherence to a healthy diet is achieved with 3 points or more, while a lower score (0–2 points) is considered as non-adherence to a healthy diet. We used a recent guideline published by Ginis et al. to define the cut off for physical activity which proposes cardiometabolic health with engagement in at least 30 min of moderate to vigorous intensity aerobic exercise 3 times per week [34,35,36,37,38]. Thus, physically active were those individuals reaching at least 90 min per week of moderate or strenuous activity. Individuals who consumed alcohol less than once a month or who never drink were classified as non-drinkers, and the others were classified as consuming alcohol. Smoking refers to study participants who reported actively smoking on the day of interview. The lifestyle score was created as a sum of these five scores providing a lifestyle score ranging from 0 to 5, with higher scores indicating higher adherence to healthy lifestyle habits. Currently, there are no studies linking lifestyle score with SCI outcomes, thus, we used the median total score value to dichotomize study participants into those with high score (scoring 4 or 5 points out of maximum of 5 points) and those with low score (scoring 0–3 points out of maximum of 5 points). Details are provided in Online Appendix I.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics was applied to summarize the baseline characteristics of individuals who had information on all five lifestyle components. To explore the possibility of non-response bias, we compared the baseline characteristics of those who were included in analyses and those for whom the lifestyle score could not be computed by using the chi-squared test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test as applicable. To address the primary aim of our study, we provided a descriptive summary of the five lifestyle components and the overall lifestyle score. To understand a complex interplay between lifestyle components, we provided a graphical summary of poor lifestyle components’ co-occurrence, by applying STATA command “combination” and reporting the counts of each unique combination of lifestyle components. To address the secondary aim of our study, we used the equality of proportions test to compare the lifestyle components and lifestyle score between sexes (male vs. female), age groups (elderly or ≥65 years old vs. young), injury etiologies (non-traumatic vs. traumatic), injury severities (tetra- vs. paraplegia) and years of education (≥14 years vs. <14 years). Potential influencing factors were chosen based on the recent systematic review of the literature that explored and summarized the major factors influencing clustering and co-occurrence of multiple risk behaviors [39] and based on availability and completeness of data in the SwiSCI study. For instance, we applied the “prtest” command for a two-sample proportion test in STATA which performs a test of the null hypothesis that the proportion of individuals with low nutrition score is the same between the individuals with traumatic vs. non-traumatic SCI. We further used the multivariable logistic regression to explore the association between personal and injury characteristics (i.e., age, sex, injury level, injury etiology, and education) and lifestyle components and overall lifestyle score. All analyses were performed using STATA 17.0 for Windows. A p value lower than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant, but as sensitivity analysis, to account for multiple testing, for each group of results we set an adjusted significance threshold based on the Bonferroni correction such that P for adjustment < .05 / (number of comparisons). Thus, we adjusted the p value from 0.05 to 0.0017 by applying the Bonferroni correction for the number of tests in regression analysis (n = 30). Further, in the main analyses, we used SCI-adjusted BMI and waist circumference cut-offs to define overweight/obesity. In the sensitivity analyses, we re-ran all analyses using the overweight/obesity definition from the general population. Therefore, overweight/obesity was defined as BMI > 25 kg/m2 or waist circumference ≥88 cm for women and ≥102 cm for men [40].

Results

Among the individuals admitted to first inpatient rehabilitation, 1 226 consented to participate in the SwiSCI study. We removed 287 individuals due to missing information on injury characteristics (n = 199), non-traumatic spinal cord injuries of neoplastic origin (n = 73), and for being underage (n = 15); leaving 939 individuals for further consideration. Overall, 251 individuals had information on all five lifestyle components and formed the study population (see Fig. 1). The median age was 51 years (IQR 36–64), the most of included individuals were male (77.7%) and suffered from traumatic SCI (73.7%). Incomplete motor injury (71.3%) and paraplegia (59.8%) were the most common injury characteristics and the median SCIM III score was 55 points (IQR 35–74). The median duration of rehabilitation was 166 days (IQR 119-208) and median time from injury to rehabilitation admission was 14 days (IQR 8–24), Table 1. When comparing the basic characteristics of study population and individuals with missing information on lifestyle factors, we observed that excluded individuals were older, had higher proportion of non-traumatic SCI, motor incomplete injury and female participants. The proportion of tetra- and paraplegia was similar across included and excluded individuals, and no significant difference was observed in activities limitations (Table 1).

Lifestyle components during inpatient stay

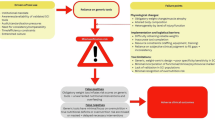

Twelve weeks after the injury, 64.9% of individuals met SCI-specific criteria for overweight/obesity. Among the elderly (≥65 years old) and individuals with non-traumatic SCI, around 80% could be classified as overweight/obese (Tables 2, 3). Alcohol consumption was reported by 85.3% of included individuals, with almost 10% of people consuming alcohol daily. More than two-thirds of included individuals (70.9%) consumed less than five portions of fruit and vegetables a day, and 60.2% consumed more than three meat portions per week. One-quarter of study population (27.9%) were smokers and almost everyone met the recommended 90 min of moderate to strenuous physical activity per week recommendation, Table 2. The Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1 show the-cooccurrence of poor lifestyle choices in study population. One quarter of study participant experienced overweight/obesity, low diet score and alcohol consumption co-occurrence (n = 64, 25.5%), whereas low nutrition score (≤2 points) and alcohol consumption were seen in 29 (11.5%) people. The second most common pattern was a one with no obesity, physical activity, and smoking abstinence, yet including alcohol consumption (n = 31, 12.3%). Supplementary Tables 2, 3 show the co-occurrence patterns in men and women. In men, results remain stable, with almost one third experiencing the co-occurrence of overweight/obesity, low diet score and alcohol consumption. The second most common pattern was overweight/obesity, low diet score, alcohol consumption and smoking (12.8%). On the other hand, the most common pattern seen in women was a relatively healthy pattern (including alcohol consumption, no obesity, no smoking, high diet score and physical activity) seen in 23.2% of women, followed by co-occurring pattern of low diet score and alcohol consumption (10.7%).

Dark gray squares indicate the presence of an unfavorable lifestyle component or risky behavior, while light gray squares indicate its absence. The numbers denote the percentage of people meeting criteria for the co-occurrence of depicted lifestyle components (i.e., 25.5% of individuals were overweight/obese, have low nutrition score and consume alcohol).

Factors influencing lifestyle components

We observed a higher prevalence of poor diet score (68.2% vs. 42.9%) and alcohol consumption (89.2% vs. 71.4%) in men as compared to women. Women, in general, were more likely to have higher lifestyle score ( ≥ 4 points out of five) points as compared to men (35.7% vs. 14.9%), Table 3. Results from multivariate logistic regression model were in line, and after adjustment for age, injury etiology, injury severity and years of education, women had 4-times higher odds of higher lifestyle score ( ≥ 4 points) as compared to men [OR 4.1 (95% CI 2.0-8.5), p ≤ 0.001]. They were also less likely to consume alcohol [OR 0.3 (95% CI 0.1–0.6), p = 0.002], to report poor diet [OR 0.3 (95% CI 0.2–0.6), p = 0.001], and to have obesity [OR 0.4 (95% CI 0.2–0.6), p = 0.01, the finding was non-significant after Bonferroni correction] Table 4. Elderly (≥65 years old) had higher prevalence of overweight/obesity (82.3%) as compared to younger study population (59.3%), Table 3. When controlling for other factors, the elderly had 2.3-times higher odds of being overweight/obese [(95% CI 1.1–5.0), p = 0.03, non-significant after Bonferroni correction], Table 4. Individuals with non-traumatic injury had higher proportion of overweight/obesity (81.8%) as compared to traumatic SCI (58.9%), and results of logistic regression were in line [the odds of overweight/obesity were 0.4 in traumatic vs. non-traumatic SCI (95% CI 0.2–0.8), p = 0.007, non-significant after Bonferroni correction]. We did not observe statistically significant differences in lifestyle components based on injury level. Finally, the odds of scoring four or five points on overall lifestyle scale, the odds of not consuming alcohol and being non-smoker were lower among people who spent ≥14 years in education vs. the reference group, however, when applying Bonferroni correction, the results did not remain significant, Table 3.

Sensitivity analyses

When using the definitions of overweight and obesity from the general population, 41.4% of individuals met the criteria, compared to 64.9% when using the SCI-specific BMI and waist circumference cut-off. Supplementary Tables 4–6 show the co-occurrence of poor lifestyle components using the general population obesity definition. The most common pattern observed was a low nutrition score combined with alcohol consumption, seen in 23.9% of the study population. In contrast, in this analysis, the pattern—obesity, low nutrition score which was the most common when using the SCI specific cut-off for overweight/obesity, and alcohol consumption—dropped to the third position at 13.2%. Elderly individuals, those with non-traumatic SCI, and those with lower education levels had a higher burden of overweight/obesity (see Supplementary Table 7). Results from the logistic regression analysis reflected the same trend, with the elderly having higher odds and those with traumatic SCI having lower odds of overweight/obesity; however, the latter results did not remain significant after Bonferroni correction (see Supplementary Table 8).

Discussion

A significant proportion of newly injured individuals with SCI had overweight/obesity, particularly the elderly and those with non-traumatic SCI. Alcohol consumption was prevalent among the study participants, with a notable portion consuming alcohol daily. Overweight/obesity, low nutrition scores and alcohol consumption co-occurred in one-quarter of the study population. Meanwhile, only a small fraction of the study population appeared to have a healthy lifestyle pattern while being in a controlled environment, such as inpatient rehabilitation. Sex, age, injury etiology, and education level were associated with lifestyle components, whereas, injury severity appeared not to play a role. Herein, we discuss the most important findings from our study and how they correlate with other evidence in the field.

Overweight/obesity

Healthy (and unhealthy lifestyle components) co-occur in complex ways that are still insufficiently understood [41]. In our study, overweight/obesity was accompanied by poor dietary choices and alcohol consumption in a large proportion of our study population. In the general population, obesity has been linked to sedentary behavior, physical inactivity, and the consumption of energy-dense food such as sugar-sweetened beverages, alcohol, and snacks as well as a low intake of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains [42]. In addition to those factors, in the SCI population, age at the time of injury, time since injury, injury severity, and hormonal changes (e.g., a decrease in circulating testosterone) further contribute to adverse changes in body composition, beginning within days to weeks post-injury [7, 43,44,45]. Increasing number of studies have modeled changes in body composition following the injury making these changes foreseeable [46,47,48,49]. Structured nutrition and physical activity regimen are largely incorporated in rehabilitation programs, and despite this, percentage of overweight/obesity at discharge from initial rehabilitation remained high [21], thus, appears that currently there is no magic formula to address the complexities of weight control in individuals with SCI [10, 11].

Diet and alcohol intake

In the context of acute/subacute SCI, studies frequently focused on the risk of malnutrition [50, 51]. This focus is justified given that optimizing macronutrient composition, caloric intake, and nutrient timing, along with the use of selected dietary supplements, can enhance the physiological response to SCI, immobilization and health complications such as skin wounds [52]. Indeed, malnutrition was widespread during inpatient rehabilitation (at three months and prior to discharge), with highest risk being observed in ventilated persons and persons with pressure injuries [51]. In the current study, we reported a discrepancy with current Swiss nutrition guidelines, noting excessive meat intake and insufficient intake of fruits and vegetables during the inpatient stay. Our colleagues assessed the diets among individuals with chronic and acute SCI and did not find a difference between the two groups. Yet, both groups consumed inappropriate amounts of micro- (e.g., very low intakes of vitamins C, D, E, folic acid, pantothenic acid, and biotin) and macronutrients (i.e., insufficient carbohydrates, excess fat) [15]. This is in line with the studies in chronic population that reported excessive energy intake and imbalanced diets comprising too much protein, carbohydrates, and insufficient vitamins and minerals [53]. We reported lower odds of poor diet score in women, which is in line with other studies in general and SCI population, that suggest that women are more likely to maintain healthier diets and are less often overweight/ obese [54]. Similarly, in our study, women were less likely to consume alcohol, which is in line with the findings among the community-dwelling SCI individuals [54]. One fifth of individuals with SCI met the criteria for alcohol abuse or heavy drinking [19, 55,56,57]. In our study, 41% of individuals consumed alcohol 1–3 times a week, whereas almost 10% of study participants consumed alcohol daily during initial rehabilitation stay. Various factors were associated with alcohol and other psychoactive substances use after the injury, including personality traits, posttraumatic depression, poor coping skills, lack of social support and pain [58]. In early injury phase, we identified male sex, and lower education status as potential factors influencing drinking patterns. These results can help build an effective screening strategy within the rehabilitation program and as a preparation for re-integration into community living.

Smoking

Smoking prevalence in SCI is largely consistent with the general population, in population-based studies the smoking prevalence was around 35% [13], whereas in clinical cohorts it ranged from 22.6% [59] to 44% [17]. Lower socioeconomic status, binge drinking, and pain medication misuse were associated with smoking [13]. Great proportion of smokers, never tried to quit, and among those who tried, only one third tried to seek professional help [13]. Besides social environment that encourages smoking, concurrent alcohol use has been identified as one of the barriers to smoking cessation [60]. In our study, around one third of individuals were smokers and smoking was mostly co-occurring together with other lifestyle components (e.g., overweight/obesity, low nutrition score and alcohol consumption were seen). This is important when considering development of future preventive strategies and complex interplay between various lifestyle components and health consequences.

Physical inactivity

Every second person with SCI engages in inactive lifestyle (as compared to approximately 30% in general population) [12, 61,62,63]. Individuals admitted to rehabilitation undergo personalized exercise regimen, occupational training, and psychological interventions. Thus, a very low proportion of individuals not meeting exercise guidelines seen in our study could be influenced by this structured physical rehabilitation program. We therefore, could not properly explore the association between personal and clinical factors and participation in physical activities. A small study in the Netherlands explored the physical behavior at discharge from initial rehabilitation and at 6- and 12-months post-discharge [16]. On average the mean duration of engagement in physical activity increased and duration of sedentary behavior decreased from discharge to 6 months post-discharge; whereas, in the next 6 month period no significant changes were observed [16]. They reported injury level, age and lower ambulation level as factors influencing physical activity patterns in this transition phase. The main concern remains individuals with high injury levels (above the sixth thoracic segment), who may participate in physical exercise or may not reach the 40–59% of peak oxygen uptake that is considered a minimum to observe health benefits [64], this subpopulation may benefit the most from composite lifestyle and/or behavioral strategies.

Study limitations and directions for future research

Our study is the first to examine the co-occurrence of five lifestyle components in newly injured individuals with SCI and to explore the association between personal and clinical factors and each lifestyle component, as well as the overall lifestyle score. One-quarter of the study participants experienced a combination of overweight/obesity, low diet scores, and alcohol consumption, indicating that these factors may require special attention during the initial phase of injury recovery. Men, older adults, and individuals with lower educational attainment may struggle to adhere to healthy lifestyle guidelines and could benefit from structured strategies designed to enhance behaviors and establish long-lasting healthy habits.

Although providing important information that can help guide future screening or preventive strategies, our findings should be interpreted with caution. First, the response rate to participation in the SwiSCI study was around 48%, and women, older persons, persons with lower functional independence and those with non-traumatic injury were less likely to participate [29]. Similar findings were observed in our sensitivity analysis when comparing people with complete information on lifestyle components with those with missing information. Thus, our findings may not be generalizable to individuals with more severe injuries, women or elderly. Second, the assessment of lifestyle components is based on self-reported information (i.e., diet, alcohol intake, smoking, and physical activity). While this issue is common in lifestyle research, we cannot exclude the possibility of recall bias (e.g., individuals who follow a special diet or pay close attention to their dietary intake may be more likely to remember and accurately report their habits). Additionally, there is a possibility of social desirability bias, meaning that participants, aware that drinking (while hospitalized) is not desirable, may provide answers they believe will be viewed favorably by others. Also, the diet score has been created based on frequency of fluid, fruits, vegetables and meat intake, and may not provide enough granularity to address the overall diet quality. Further, obesity was defined using clinical assessment of BMI and waist circumference using SCI specific cut-offs, however, since our study measurements were done around 12 weeks post-injury, this cut-off could be overestimating the prevalence of overweight/obesity. Thus, as sensitivity analysis, we applied the general population cut-off for overweight/obesity and our results remain stable. Third, the lifestyle factors were measured around twelve weeks post-injury during initial rehabilitation stay. Since we used the data obtained through a standardized measurement within the SwiSCI study, we did not have information on lifestyle components prior to the injury. The change in health-related behavior often slow and changing for better remains difficult [65], thus, we can argue that some lifestyle habits, such as smoking, dietary or alcohol intake may reflect the habits observed prior to the injury. Changes in body weight and physical activity engagement are more likely to change dramatically after the injury. Perhaps, studies exploring the evolution of lifestyle patterns before and after the injury, could help us understand the behavioral profile of affected individuals and create more effective strategies targeting lifestyle and behavior. For instance, in our analysis age, sex and education were associated with lifestyle components, which is similar as observed in general population. Whereas, injury severity was not associated with lifestyle components, yet, the injury severity, independence in activities of daily living, social support and other environmental factors may be crucial in providing support to develop and maintain healthy lifestyle habits in community setting. Fourth, despite meals being provided by the hospital and the controlled environment designed to promote abstinence from smoking and drinking (without an official ban), our study population still engaged in risky behaviors. We therefore anticipate a potential decline in adherence to a healthy lifestyle during the transition from inpatient rehabilitation to community living, which is a critical period for preventing medical complications such as metabolic syndrome or diabetes [21]. Thus, future studies should explore the lifestyle changes adopted during this transition phase and identify the most important personal and clinical characteristics associated with potential lifestyle components worsening. The complex role of psychosocial factors including social support, needs to be considered alongside other factors. Furthermore, it is necessary to study the association between multiple lifestyle components on health outcomes in both the early injury phase and among those aging with SCI, who may be especially prone to developing health complications (e.g., MetS, CVD, pressure injuries or gastrointestinal problems). Finally, focusing on the synergistic effects of interventions integrating multiple lifestyle components will help develop personalized, sustainable interventions that address multiple risk factors simultaneously. This approach will allow us to identify effective and lasting strategies for disease prevention, improve overall quality of life, and create tailored healthcare approaches for the SCI population.

Conclusions

This study provides a descriptive summary of five lifestyle components, their co-occurrence, and factors associated with single components and overall lifestyle score in individuals newly diagnosed with SCI and undergoing their first inpatient rehabilitation. Despite the notable methodological limitations of our approach, we offer valuable insights which can be used to address the complexities of SCI care. We identify obesity, alcohol consumption, and diet as factors requiring special consideration during the early injury phase. Men, the elderly, and individuals with lower education levels may particularly struggle to adhere to healthy lifestyle recommendation and may benefit from structured approaches towards improving behavior and building healthy habits in this vulnerable period. Future studies are to replicate our findings in other settings and address methodological issues raised within the current study.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the commitment to SwiSCI study participants and their privacy but are available from SwiSCI Study Center (contact@swisci.ch) on reasonable request.

References

Kressler J, Cowan RE, Bigford GE, Nash MS. Reducing cardiometabolic disease in spinal cord injury. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2014;25:573–604, viii.

Rochlani Y, Pothineni NV, Kovelamudi S, Mehta JL. Metabolic syndrome: pathophysiology, management, and modulation by natural compounds. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;11:215–25.

Rankin KC, O’Brien LC, Segal L, Khan MR, Gorgey AS. Liver adiposity and metabolic profile in individuals with chronic spinal cord injury. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:1364818.

Cragg JJ, Noonan VK, Krassioukov A, Borisoff J. Cardiovascular disease and spinal cord injury: results from a national population health survey. Neurology. 2013;81:723–8.

van Bussel EF, Hoevenaar-Blom MP, Poortvliet RKE, Gussekloo J, van Dalen JW, van Gool WA, et al. Predictive value of traditional risk factors for cardiovascular disease in older people: A systematic review. Prev Med. 2020;132:105986.

Raguindin PF, Frankl G, Itodo OA, Bertolo A, Zeh RM, Capossela S, et al. The neurological level of spinal cord injury and cardiovascular risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Spinal cord. 2021;59:1135–45.

Raguindin PF, Bertolo A, Zeh RM, Fränkl G, Itodo OA, Capossela S, et al. Body composition according to spinal cord injury level: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2021;10:3911.

Nash M, Gater D. Cardiometabolic disease and dysfunction following spinal cord injury. Phys Med Rehab Clinics North America. 2020;31:415–36.

Bigford G, Nash MS. Nutritional health considerations for persons with spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2017;23:188–206.

Itodo OA, Flueck JL, Raguindin PF, Stojic S, Brach M, Perret C, et al. Physical activity and cardiometabolic risk factors in individuals with spinal cord injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2022;37:335–65.

Stojic S, Eriks-Hoogland I, Gamba M, Valido E, Minder B, Chatelan A, et al. Mapping of dietary interventions beneficial in the prevention of secondary health conditions in spinal cord injured population: a systematic review. J Nutr Health Aging. 2023;27:524–41.

Ginis KA, Latimer AE, Arbour-Nicitopoulos KP, Buchholz AC, Bray SR, Craven BC, et al. Leisure time physical activity in a population-based sample of people with spinal cord injury part I: demographic and injury-related correlates. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:722–8.

Saunders LL, Krause JS, Saladin M, Carpenter MJ. Prevalence of cigarette smoking and attempts to quit in a population-based cohort with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2015;53:641–5.

Chuang CH, Chen PC, Bai CH, Wu YL, Tsai MC, Li CY. Association between spinal cord injury and alcohol dependence: a population-based retrospective cohort study. J Pers Med. 2022;12:473.

Perret C, Stoffel-Kurt N. Comparison of nutritional intake between individuals with acute and chronic spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2011;34:569–75.

Postma K, Bussmann JBJ, van Diemen T, Post MWM, Dekkers J, van Nes IJW, et al. Physical activity and sedentary behavior from discharge to 1 year after inpatient rehabilitation in ambulatory people with spinal cord injury: a longitudinal cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;101:2061–70.

Haisma JA, van der Woude LH, Stam HJ, Bergen MP, Sluis TA, Post MW, et al. Complications following spinal cord injury: occurrence and risk factors in a longitudinal study during and after inpatient rehabilitation. J Rehabil Med. 2007;39:393–8.

Wouda MF, Lundgaard E, Becker F, Strøm V. Changes in cardiorespiratory fitness and activity levels over the first year after discharge in ambulatory persons with recent incomplete spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2021;59:354–60.

Davis JF, Cao Y, Krause JS. Changes in alcohol use after the onset of spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2018;41:230–7.

Raguindin PF, Mueller G, Stoyanov J, Eriks-Hoogland I, Jordan X, Stojic S, et al. Burden of cardiovascular risk in individuals with spinal cord injury and its association with rehabilitation outcomes: results from the swiss spinal cord injury cohort. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2023;102:1043–54.

Raguindin PF, Stoyanov J, Eriks-Hoogland I, Stucki G, Jordan X, Schubert M, et al. Cardiometabolic risk profiling during spinal cord injury rehabilitation: A longitudinal analysis from the Swiss Spinal Cord Injury (SwiSCI) cohort. PM R. 2023;15:715–30.

Raguindin PF, Itodo OA, Eriks-Hoogland I, Muka T, Brach M, Stucki G, et al. Does cardiometabolic risk profile differ among individuals with traumatic and non-traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI): the evidence from the multicenter SCI cohort in Switzerland (SwiSCI). Spinal Cord. 2024;62:387–95.

Deutschsprachige Medizinische Gesellschaft für Paraplegiologie e.V. S2k-Leitlinie Lebenslange Nachsorge für Menschen mit Querschnittlähmung [Internet]. AWMF Leitlinien-Register; [cited 2023 Nov 19]. Report No.: 1.0. Available from: https://register.awmf.org/de/start.

Nowak AM, Molik B, Marszalek J. Anaerobic performance among children with spina bifida. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2020;60:132–9.

Vajdi M, Farhangi MA. A systematic review of the association between dietary patterns and health-related quality of life. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18:337.

Leeming ER, Johnson AJ, Spector TD, Le Roy CI. Effect of diet on the gut microbiota: rethinking intervention duration. Nutrients. 2019;11:2862.

Sahni S, Mangano KM, McLean RR, Hannan MT, Kiel DP. Dietary approaches for bone health: lessons from the Framingham Osteoporosis Study. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2015;13:245–55.

Ljungberg T, Bondza E, Lethin C. Evidence of the importance of dietary habits regarding depressive symptoms and depression. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1616.

Fekete C, Gurtner B, Kunz S, Gemperli A, Gmünder HP, Hund-Georgiadis M, et al. Inception cohort of the Swiss Spinal Cord Injury Cohort Study (SwiSCI): Design, participant characteristics, response rates and non-response. J Rehabil Med. 2021;53:jrm00159.

Marino RJ, Barros T, Biering-Sorensen F, Burns SP, Donovan WH, Graves DE, et al. International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2003;26:S50–6.

Itzkovich M, Gelernter I, Biering-Sorensen F, Weeks C, Laramee MT, Craven BC, et al. The spinal cord independence measure (SCIM) version III: reliability and validity in a multi-center international study. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29:1926–33.

de Groot S, van der Woude LH, Niezen A, Smit CA, Post MW. Evaluation of the physical activity scale for individuals with physical disabilities in people with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2010;48:542–7.

Federal Statistics Office. Swiss Health Survey. Neuenburg: Federal Department of Home Affairs (FDHA); 2007.

Sumrell RM, Nightingale TE, McCauley LS, Gorgey AS. Anthropometric cutoffs and associations with visceral adiposity and metabolic biomarkers after spinal cord injury. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0203049.

Ginis KA, Hicks AL, Latimer AE, Warburton DE, Bourne C, Ditor DS, et al. The development of evidence-informed physical activity guidelines for adults with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2011;49:1088–96.

Evans N, Wingo B, Sasso E, Hicks A, Gorgey AS, Harness E. Exercise recommendations and considerations for persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:1749–50.

van der Scheer JW, Martin Ginis KA, Ditor DS, Goosey-Tolfrey VL, Hicks AL, West CR, et al. Effects of exercise on fitness and health of adults with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Neurology. 2017;89:736–45.

Martin Ginis KA, van der Scheer JW, Latimer-Cheung AE, Barrow A, Bourne C, Carruthers P, et al. Evidence-based scientific exercise guidelines for adults with spinal cord injury: an update and a new guideline. Spinal Cord. 2018;56:308–21.

Meader N, King K, Moe-Byrne T, Wright K, Graham H, Petticrew M, et al. A systematic review on the clustering and co-occurrence of multiple risk behaviours. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:657.

Lean ME, Han TS, Morrison CE. Waist circumference as a measure for indicating need for weight management. BMJ. 1995;311:158–61.

Leech RM, McNaughton SA, Timperio A. The clustering of diet, physical activity and sedentary behavior in children and adolescents: a review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11:4.

Popkin BM, Ng SW. The nutrition transition to a stage of high obesity and noncommunicable disease prevalence dominated by ultra-processed foods is not inevitable. Obes Rev. 2022;23:e13366.

Gorgey AS, Dolbow DR, Dolbow JD, Khalil RK, Castillo C, Gater DR. Effects of spinal cord injury on body composition and metabolic profile - part I. J Spinal Cord Med. 2014;37:693–702.

Itodo OA, Raguindin PF, Wöllner J, Eriks-Hoogland I, Jordan X, Hund-Georgiadis M, et al. Early changes in androgen levels in individuals with spinal cord injury: a longitudinal SwiSCI study. J Clin Med. 2022;11:6559.

Boehl G, Raguindin PF, Valido E, Bertolo A, Itodo OA, Minder B, et al. Endocrinological and inflammatory markers in individuals with spinal cord injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2022;23:1035–50.

Felleiter P, Krebs J, Haeberli Y, Schmid W, Tesini S, Perret C. Post-traumatic changes in energy expenditure and body composition in patients with acute spinal cord injury. J Rehabil Med. 2017;49:579–84.

Desneves KJ, Kiss N, Daly RM, Abbott G, Ward LC. Longitudinal changes in body composition and diet after acute spinal cord injury. Nutrition. 2024;120:112345.

Ma Y, de Groot S, Romviel S, Achterberg W, van Orsouw L, Janssen TWJ. Changes in body composition during and after inpatient rehabilitation in people with recent spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord Series and Cases. 2021;7:88.

Singh R, Rohilla RK, Saini G, Kaur K. Longitudinal study of body composition in spinal cord injury patients. Indian J Orthop. 2014;48:168–77.

Rowan C, Kazemi A. An observational study of feeding practice in ventilated patients with spinal cord injury. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2020;37:107–13.

Flury I, Mueller G, Perret C. The risk of malnutrition in patients with spinal cord injury during inpatient rehabilitation-A longitudinal cohort study. Front Nutr. 2023;10:1085638.

Smith-Ryan AE, Hirsch KR, Saylor HE, Gould LM, Blue MNM. Nutritional considerations and strategies to facilitate injury recovery and rehabilitation. J Athl Train. 2020;55:918–30.

Farkas GJ, Pitot MA, Berg AS, Gater DR. Nutritional status in chronic spinal cord injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Spinal Cord. 2019;57:3–17.

Groah SL, Nash MS, Ljungberg IH, Libin A, Hamm LF, Ward E, et al. Nutrient intake and body habitus after spinal cord injury: an analysis by sex and level of injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2009;32:25–33.

Saunders LL, Krause JS. Psychological factors affecting alcohol use after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2011;49:637–42.

Tate DG, Forchheimer MB, Krause JS, Meade MA, Bombardier CH. Patterns of alcohol and substance use and abuse in persons with spinal cord injury: risk factors and correlates. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:1837–47.

Young ME, Rintala DH, Rossi CD, Hart KA, Fuhrer MJ. Alcohol and marijuana use in a community-based sample of persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76:525–32.

Tétrault M, Courtois F. Use of psychoactive substances in persons with spinal cord injury: a literature review. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2014;57:684–95.

Saunders LL, Krause JS, Carpenter MJ, Saladin M. Risk behaviors related to cigarette smoking among persons with spinal cord injury. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16:224–30.

Saunders L, Newman S, Aust R, Krause JS. Qualitative study of barriers and facilitators to cigarette smoking after spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol. 2018;63:400–7.

Williams TL, Smith B, Papathomas A. The barriers, benefits and facilitators of leisure time physical activity among people with spinal cord injury: a meta-synthesis of qualitative findings. Health Psychol Rev. 2014;8:404–25.

Tasiemski T, Bergström E, Savic G, Gardner BP. Sports, recreation and employment following spinal cord injury–a pilot study. Spinal Cord. 2000;38:173–84.

World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. Physical inactivity: a global public health problem.

Flank P, Fahlstrom M, Bostrom C, Lewis JE, Levi R, Wahman K. Self-reported physical activity and risk markers for cardiovascular disease after spinal cord injury. J Rehabil Med. 2014;46:886–90.

Kelly MP, Barker M. Why is changing health-related behaviour so difficult? Public Health. 2016;136:109–16.

Acknowledgements

We thank the SwiSCI Steering Committee, in particular its members Fabienne Reynard (Clinique Romande de Réadaptation, Sion); Michael Baumberger, Luca Jelmoni (Swiss Paraplegic Center, Nottwil); Armin Curt, Martin Schubert (Balgrist University Hospital, Zurich); Laurent Prince (Swiss Paraplegic Association, Nottwil); Daniel Joggi (Representative of individuals with SCI); NN (Parahelp, Nottwil); Mirjam Brach, Gerold Stucki (Swiss Paraplegic Research, Nottwil) and Carla Sabariego (SwiSCI Coordination Group at Swiss Paraplegic Research, Nottwil).

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Bern.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MG conceptualized the study. MH and SS analyzed the data. MH, SS, and MG prepared the first draft of the manuscript. IEH, JS, MHG and CP interpreted the data and critically revised the manuscript. MG supervised the study conduct. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The SwiSCI study is compliant with the Swiss Human Research Act (810.30 Federal Act of September 30, 2011, on Research involving Human Beings) and Federal Regulations on Data Protection. Participation in the SwiSCI study is voluntary, and the patients’ informed consent is obtained prior to participation. The relevant ethics committees of the participating centers (Ethics Committee northwest/central Switzerland (EKNZ), Ethics Committee Vaud (CEVD), Ethics Committee Zurich (KEKZH)) have approved the study protocol and all associated assessments. The data used for the present study were anonymized, with no possibility to identify participants. All study participants signed informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Haldemann, M., Stojic, S., Eriks-Hoogland, I. et al. Exploring lifestyle components and associated factors in newly injured individuals with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 62, 708–717 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-024-01039-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-024-01039-9