Abstract

Heightened negative affect is a core feature of serious mental illness. Over 90% of American adults own a smartphone, equipped with an array of sensors which can continuously and unobtrusively measure behaviors (e.g., activity levels, location, and phone usage patterns) which may predict increases in negative affect in real-time in individuals’ daily lives. Sixty-eight adults with a primary mood or psychotic disorder completed daily emotion surveys for over a year, on average (mean 465 days; total surveys = 12,959). At the same time, semi-continuous collection of smartphone accelerometer, GPS location, and screen usage data, along with accelerometer tracking from a wrist-worn wearable device, was conducted for the duration of the study. A range of statistical approaches, including a novel personalized ensemble machine learning algorithm, were compared in their ability to predict states of heightened negative affect. A personalized ensemble machine learning algorithm outperformed other statistical approaches, achieving an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.72 (for irritability) −0.79 (for loneliness) in predicting different negative emotions. Smartphone location (GPS) variables were the most predictive features overall. Critically, there was substantial heterogeneity between individuals in the association between smartphone features and negative emotional states, which highlights the need for a personalized modeling approach. Findings support the use of smartphones coupled with machine learning to detect states of heightened negative emotions. The ability to predict these states in real-time could inform the development and timely delivery of emotionally beneficial smartphone-delivered interventions which could be automatically triggered via a predictive algorithm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A defining characteristic of serious mental illness (SMI), encompassing mood disorders (bipolar and major depressive disorder) and psychotic disorders, is disturbance in negative affect, including increased frequency, intensity, or duration of negative emotional states such as sadness, anxiety, and anger, which commonly last hours [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. There is a critical need to develop scalable tools to identify and alleviate states of heightened negative affect as they arise in, and interfere with, the daily lives of these individuals. Towards this goal, over 90% of American adults own a smartphone [10], which are equipped with an array of built-in sensors capable of tracking behaviors predictive of shifts in affect, including activity levels (accelerometer), location (GPS), call and text data, and patterns of phone usage [11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Smartphones can continuously and unobtrusively monitor individuals in their day-to-day lives, providing rich and potentially predictive information on emotional states. For example, an individual experiencing a surge in sadness may become less active, spend more time in their home and be less likely to initiate and respond to texts and calls, all of which can be measured from smartphone sensors.

Whether such “passive” (i.e., no user input required) smartphone data can reliably predict states of heightened negative affect among those suffering from SMI is an open question. Several studies provide promising initial evidence indicating that passively collected data from smartphone sensors can signal elevated negative emotions [11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. To the extent that states of heightened negative emotions could be reliably predicted from smartphone data, brief, low-cost and highly scalable psychosocial interventions could be immediately triggered on an individual’s smartphone (e.g., app-delivered mindfulness, behavioral activation, or cognitive reappraisal exercises) to alleviate these states in a timely fashion.

The present study builds on prior research examining the relationship between smartphone-derived variables and emotional states in several ways. First, we will test whether machine learning approaches (e.g., random forest, support vector machines, regularized regression) well-suited to complex, high-dimensional passive sensor data outperform simpler, conventional statistical approaches (e.g., multilevel modeling). We will also directly compare different machine learning approaches to determine if any one algorithm yields superior predictive performance. Of relevance, one recent smartphone study in youth with elevated depressive symptoms found that random forest predicted negative emotional states more accurately than several other statistical algorithms [15]. In addition, given that some machine learning approaches rely on very different underlying algorithms for modeling the association between predictors and outcomes (e.g., elastic net is a relatively simple variant of conventional Ordinary Least Squares [OLS] regression, whereas random forest is a decision-tree based approach which can detect higher-order interactions and non-linear associations) they may have complementary strengths [15, 18, 19]. Thus, we also tested whether a weighted combination of these machine learning algorithms outperforms any individual algorithm.

Second, prior studies have typically collected passive sensing data over relatively short timeframes ranging from a few days to a few weeks [14, 20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29] (For an exception, see [30]). Such relatively short timeframes may not provide adequate opportunity to observe sufficient variance in symptoms and limit statistical power for within-person (idiographic) analyses. Individuals with SMI experience fluctuations in symptoms at multiple timescales and of varying severity; therefore, here we employed an extended study observation period of one year in each individual to ensure adequate sampling of mood and affect over a timeframe expected to result in clinically meaningful changes.

Third, wrist-worn wearable devices (e.g., smartwatches and actigraphy wristbands) may offer a valuable extension to smartphone-derived measures for enhancing the prediction of heightened negative affect. These wrist-worn wearables often include built-in accelerometers and gyroscopes, enabling the measurement of physical activity and movement patterns. This data can be crucial in understanding the correlation between physical activity levels and emotion fluctuations. Wrist-worn devices sometimes also offer continuous and unobtrusive monitoring of emotion-relevant physiological parameters such as heart rate, skin conductance, and sleep patterns. Importantly, the data collected with these devices provide an uninterrupted stream of data collection (including during sleep if the wrist-worn device is kept on at night), compared to smartphones which may be left behind/forgotten, fail to transmit signal, or turned off. This granularity may allow for more accurate and timely predictions of negative affective states, enabling early intervention or support when needed. The psychometric properties of these measures vary by device, manufacturer, and wear time compliance [31,32,33]. For example, with regards to reliability, one study using the GENEActiv wrist worn accelerometer in over 2745 children found that to achieve acceptable reliability (ICC = 0.70), 3–5 nights of data are needed for sleep estimates and 3–4 days of data are needed for physical activity and sedentary time estimates [31]. Studies have also evaluated the validity of wrist-worn device estimates of activity such as step count (relative to manual tallying of steps or accelerometry in a controlled setting) and sleep (e.g., relative to gold-standard polysomnography) [31,32,33]. Of note, variability in the reliability and validity of consumer-grade devices and updates to software can pose challenges for consistent data collection [34,35,36]. To address this, we used a research-grade wearable (GENEActiv) with full access to raw triaxial accelerometer signals, ensuring transparency and consistency in our derived signals.

Fourth, and critically, there may be substantial between-individual differences in the behavioral patterns associated with negative emotional states. For example, an individual experiencing heightened anxiety may become more physically restless, as reflected by increased overall activity levels (captured by the smartphone’s accelerometer) and movement from location to location (GPS) and may spend more time interacting with their smartphone [37, 38]. In contrast, another individual in the midst of an anxious state may show a very different pattern: for example, they may spend more time in their home (GPS) with limited movement (accelerometer), and show increased interpersonal avoidance (e.g., as evidenced by sending and responding to fewer text messages and phone calls). In other words, individuals may differ both in the direction of the association between particular smartphone variables and increases in specific negative emotions (e.g., increases vs. decreases in activity levels predicting heightened anxiety) and in which features predict heightened negative emotions. In summary, such between-person differences highlight the need for a person-specific (idiographic) modeling strategy, where the association between passive sensing features and negative affect is modeled separately for each individual.

At the same time, certain passive sensor-emotion associations may be shared across individuals. Thus, when predicting the negative emotional states of one individual it may be helpful to leverage information from the predictive model of other individuals. The present study will compare the predictive performance of fully idiographic models (i.e., only using the individual’s own data when building a predictive model for them) versus a weighted ensemble model that allows for the borrowing of information from the predictive models of other individuals to improve predictive performance by leveraging shared predictive patterns.

Methods

Participants and procedure

Study participants were 70 adults diagnosed with a primary affective disorder (e.g., bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder) or psychotic disorder (i.e., schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder). Among participants enrolled between 2015 and 2019, passive smartphone signals and wrist-worn actigraphy were available for subsets of 68 and 31 participants, respectively (see Table 1 for demographic and clinical characteristics of the final sample). Participants were recruited via study advertisement through the divisions for Depression and Anxiety Disorders and Psychotic Disorders at McLean Hospital and using the Rally platform through Mass General Brigham (MGB). The duration of the study per participant was set as one year, with the option of continuing participation depending on the severity and fluctuation of a participant’s symptoms as assessed during monthly clinic visits (M = 465 days, SD = 426 days, range = 3–2044 days; total daily emotion surveys collected = 12,959). Participants installed the Android and iOS compatible smartphone application Beiwe [38, 39] onto their own device to provide semi-continuous, passive collection of screen usage, accelerometry, and GPS data. Using Beiwe, participants were also invited to complete ecological surveys (see Measures: Outcomes). Participants were also given the option to wear a GENEActiv (ActivInsights, Inc.) actigraphy device on their wrist continuously and return or swap out the watch at the time of their monthly clinical visit. This wrist-worn device measures movement which is used to derive metrics for a participant’s sleep and physical activity.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Mass General Brigham (MGB) Institutional Review Board (2015P002189) and informed consent was obtained from all subjects. All procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration.

Measures

Outcomes

When initially enrolled, demographic information (age, gender, and race) and patient’s diagnoses were recorded. The daily 31-item survey consisted of questions on emotion, psychotic symptoms, social behavior, physical activity, sleep, and alcohol and coffee consumption. The primary outcomes for our study were the daily negative affect items which included self-report questions on feeling anxious, irritable, upset, and lonely (ordinal, 1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = moderately, 4 = extremely; e.g., “How anxious have you been feeling today?”).

Predictors

Primary predictors include variables extracted from passive smartphone data. Using smartphone accelerometry and screen usage data, we performed weekly estimations of sleep epochs to derive features reflecting (1) phone usage during the sleep epoch, (2) sleep onset, (3) sleep offset, (4) sleep duration, (5) phone usage during the wake period, (6) the difference in phone usage between wake and sleep periods, and (7) missing phone data. All these variables are explained in Supplementary Table S1. GPS coordinates collected by the smartphones were analyzed by our open-source Deep Phenotyping of Location (DPLocate) pipeline [40]. This pipeline which was designed and validated in multiple data sets, uses different temporal and spatial filters to clean the GPS data and detect frequently visited places, called points of Interest (POI), using density-based clustering techniques, and assign those POIs to the related minutes of the day [40]. The daily location maps are then used to estimate features for (1) distance from home location, (2) radius of mobility, (3) percentage of time spent at home location, (4) number of locations visited, and (5) GPS missing time. The definition of these variables is also explained in Supplementary Table S1. Moreover, the daily measures of (1) phone accelerometer and (2) phone use that are used as daily features in the analysis are explained in this table.

Using data from a subset of the cohort (n = 31) with available wrist-worn actigraphy, we derived additional daily features related to sleep and activity using a previously published open source pipeline (DPSleep [41]). Primary predictors derived from wrist-worn actigraphy include (1) accepted days of watch data after quality control, (2) sleep onset, (3) sleep offset, (4) sleep duration, (5) activity during sleep epoch, (6) activity during wake period, (7) the difference in activity between wake and sleep periods, and (8) sleep fragmentation (Supplementary Table S2). Due to high level of missingness, we were only able to analyze 8 subjects with sufficient number of observations of either the wrist-worn actigraphy measures or negative emotions. Thus, the results presented below focus on smartphone features as predictors. For wrist-worn actigraphy results see the supplementary document.

Analytic approach

Missing data imputation

Missingness for the above smartphone predictor variables was imputed using multiple imputation (MICE package in r) [42], while outcome variables were not imputed to avoid overfitting of prediction models. The imputation process was performed jointly for all passive variables, excluding the outcome variables (i.e., negative emotional states). We produced 5 imputations and performed 5 iterations per imputation, which are the default choices in MICE [42]. Since the goal of our analysis is prediction, we used the mean values of the imputed passive variables across the five imputations when training the predictive algorithms [43].

Definition of high negative affect (HNA) states

This study is focused on the prediction of states of heightened negative emotions (specifically, anxious, irritable, upset, and lonely). For brevity, below we refer to these states as high negative affect (HNA) states. Consistent with Ren et al. [15], HNA states were computed based on elevations above the person-specific average emotion score for a given individual. Specifically, for each emotion, if the observed emotion score of a given participant at a particular timepoint exceeds their mean emotion score by at least 1/2 point, we define this as an HNA state of that emotion (see Table 2). This cutoff value is identical to a previous study [15] and was selected by balancing the tradeoff between (1) the selected cutoff value to define an HNA state and (2) the proportion of these states. By selecting a higher cutoff value, we can be more confident that HNA states are in fact instances of “high” negative affect. However, overly high cutoff values may result in proportions of HNA states that are too low to successfully train a classification algorithm. On the other hand, although low cutoff values provide us with more HNA states for statistical modeling, it also increases the chance that at least some of these identified states are questionable (i.e., too low to be considered true states of “high” negative affect). For each of the negative affect items, patients were excluded from the analyses if they had less than 10 total observations and 4 or 10% (whichever implies more total number of HNA events) of negative emotion events. For example, a subject with 100 total observations and 4 HNA events will be removed since the proportion of HNA events is less than 10%. Using this threshold, the number of participants for the analyses predicting anxious, irritable, upset, and lonely states was 35, 36, 40, and 42, respectively.

Personalized predictions of HNA states

Passive smartphone features and wrist-worn actigraphy data were used to predict HNA states from the same day. We used two approaches to model the relation between these passive data features and HNA states. First, we used a generalized linear mixed effects regression (GLMER) with logit link and subject-specific random intercept to model the heterogeneity between participants. The GLMER model combines fixed effects and the best linear unbiased predictions of the random effects [44] to predict the person-specific outcomes (HNA states). The GLMER is a simpler and commonly used approach that we implemented for comparison against our machine learning ensemble approach described below.

Next, we used a recently developed ensemble machine learning approach [15, 45] that builds a unique predictive model for each individual while borrowing information from other individuals’ models in an effort to improve predictive performance. Specifically, this approach develops an ensemble of idiosyncratic prediction models \({f}_{i}^{l}\left(x\right),{i}=1,\ldots ,K,{l}=1,\ldots ,L\), where K is the number of individuals and L represents the number of different learning algorithms (e.g., logistic regression). \({f}_{i}^{l}\left(x\right)\) is trained on data from participant i with algorithm l. The “personalized ensemble model” (PEM) \({f}_{i}\left({x;}{w}^{i}\right)\) for participant i is a linear combination of all idiosyncratic models (IM):

and the combination weights \({w}^{i}=({w}_{{i}^{{\prime} },l}^{i};{i}^{{\prime} }=1,\ldots K,l=1,\ldots ,L)\) with the constraints that \({\sum }_{{i}^{{\prime} },l}{w}_{{i}^{{\prime} },l}^{i}=1\) and \({w}_{{i}^{{\prime} },l}^{i}\ge 0\) for all \(i,{i}^{{\prime} }\in \{1,\ldots ,K\}\) and \(l\in \{1,\ldots ,L\}\) are selected to minimize a cross-validated loss function:

where \({n}_{i}\) is the number of observations for participant i and \({f}_{i,-j}^{l}(x)\) is the IM trained on all data from participant i except for the j-th observation (or a fold containing the j-th observation) with algorithm l. \({\mathscr{L}}\) is a loss function (log-loss for binary outcomes given that we are predicting whether or not an HNA state is present). In summary, this approach develops a personalized model for each individual via a data-driven search for the optimal weighting of IMs for that individual (i.e., “borrowing” information from the prediction models for other individuals in an effort to improve predictive performance). See Ren et al. [15] for additional details.

For the PEM statistical approach, we conducted 10-fold cross-validation (CV) to estimate the combination weights \({\widehat{{\rm{w}}}}^{i}\) and examined three different learning algorithms (see supplement for time-series CV, which yielded a similar pattern of findings): GLM with elastic net penalty (ENet), support vector machine (SVM), and random forest (RF). We used these algorithms individually \((L=1)\) in three separate ensemble (PEM-ENet, PEM-SVM and PEM-RF) models and in combination \((L=3)\) (i.e., 4 separate ensemble models were tested in total). We refer to the PEMs with \(L=3\) as a personalized double ensemble model (PDEM). Note that the cross-validation procedure partitions time points within a subject into different folds. See supplement for additional details. R code for all analyses is available online (https://github.com/bcj2024/BLS_ensemble). We assume that the pattern of missingness in our data is Missing at Random (MAR; See Supplement for details).

Feature engineering

The original PEM approach in Ren et al. [15] used a principal component analysis (PCA) to first reduce the raw smartphone features into several PCs, which yielded better prediction performance compared to models using the raw features as predictors. In this study, we used a modified version of the PEM approach, combining the generalizability of PCA-based models and the specificity of the raw feature-based models, in an effort to achieve an improved personalized prediction performance. This was achieved by including two idiosyncratic models (IMs) for each learning algorithm and participant, where one used the raw features as the predictors and the other used the PCs of the raw features. Operationally, with L learning algorithms, 2L IMs were generated, where \({f}_{i}^{l}\) and \({f}_{i}^{L+l}\) are the raw-feature- and PCA-based models, respectively, for participant i using learning algorithm l.

Clustering based on feature importance

We visualized the feature importance measures of each smartphone variable based on the best performing PEMs by linearly combining the feature importance of the IMs with the ensemble weights w. We normalized these measures such that the sum of their absolute values is one per subject. The signs of the importance are determined by the conditional relationship implied by the PEMs between a feature and an outcome. We then performed a K-medoid clustering on the feature importance matrix to identify subgroups of patients with similar feature importance signature. Euclidean distance was used to compute the pairwise dissimilarity between participants. The number of clusters was selected to maximize the average silhouette width, with an upper limit of five imposed to enhance the robustness and reliability of the clustering results, given the small between-subject sample size in our dataset. The pam function in R package cluster was used for this analysis.

Results

HNA state summary statistics

On average, over 200 daily emotion ratings were collected per participant, and HNA states were present at 25–30% of these timepoints (see Table 2). HNA states were, on average, 0.94 to 1.36 points above an individual’s mean emotion score. To convert these scores into a Cohen’s d-type effect size [46], we divided them by the mean within-person standard deviation (SD) of each emotion. For example, the mean within-person SD of anxiety was 0.69, and HNA states of anxiety were, on average, 0.94 points higher than an individual’s mean anxiety score. Thus, the effect size is d = 1.36 (0.94/0.69). The corresponding values for the 3 other emotions were d = 1.45 (irritable), d = 1.43 (upset) and d = 1.33 (lonely). In summary, HNA states were, on average, approximately 1.3 to 1.5 SDs above an individual’s own mean emotion scores, which would be considered large elevations in negative emotions according to d-type effect size conventions (0.2 = “small”, 0.5 = “medium” and 0.8 = “large”) [46].

PEM-RF and PDEM outperformed other models in predicting NA

Based on passively collected sensor data, machine learning models were able to predict states of heightened NA above chance (i.e., AUC > 0.50). All ensemble machine learning approaches (PDEM, PEM-RF, PEM-Enet, and PEM-SVM) outperformed a simpler, conventional linear mixed effects model (GLMER) in predicting NA, highlighting the benefit of these algorithms with regards to improving prediction accuracy (see Table 3 and Fig. 1). For each of the 4 emotions, the most complex model (PDEM) outperformed all other models, but only had slightly higher AUC relative to PEM-RF, which in turn outperformed the other 3 models (PEM-Enet, PEM-SVM and GLMER). Recall that PDEM is a weighted ensemble of PEM-RF, PEM-Enet and PEM-SVM. Thus, the above pattern of findings suggests that the main contributor to the superior performance of PDEM is PEM-RF. When comparing the four emotions, PEM methods achieve the highest level of accuracy for predicting loneliness, followed by anxiety, feeling upset, and irritability. See Supplement for a time series cross-validation (as opposed to regular 10-folds cross-validation) which yielded a very similar pattern of findings.

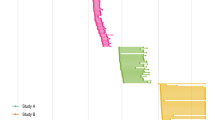

Location (GPS) variables were most predictive of NA

To determine which variables were driving the predictive performance of the models, we plotted feature/variable importance for each participant (columns) and each emotion (panels) (Fig. 2). Averaging across all participants, the GPS variables had the highest feature importance across all four emotions. Importantly, given the personalized modeling approach, two individuals could have very different rankings of variable importance, as well as differences in the direction of associations between a given predictor variable and outcome. For example, when examining the raw correlations between individual features and emotion scores, most (80%) participants had an inverse association between GPS radius mobility (the radius of the smallest circle that contains all points of interest visited during the day) and loneliness. In contrast, half (49%) of participants had a positive association between activity levels (accelerometer) and anxiety, whereas the other half had an inverse association.

The vertical black lines demarcate the clusters of patients identified based on feature importance. Note that their clusters exhibited strong within-cluster consistency and cross-cluster heterogeneity in the directionality of a feature’s effect for the top 4 or 5 most important features. See Supplement (Feature Importance section) for additional details.

Benefit of personalized ensemble models (PEM) over idiosyncratic models (IMs)

The boxplots in Fig. 3 illustrate the distribution of differences between the PEM and IMs on two metrics of predictive performance (AUC and Brier score). That is, for each individual, we computed the difference in predictive performance for each PEM approach versus their corresponding IM. We can see that all three algorithms (ENet, SVM, and RF) consistently benefited from the ensemble approach (PEM) with a median increase in AUCs of 0.05 and a median decrease in Brier scores of 0.013. All boxplots are not overlapped with zero, indicating these improvements are consistent across at least 75% of the participants.

Supplementary Fig. S2 provides further support for the benefit of a PEM approach. Specifically, each row of the plot displays (with red shading) the weights applied to each IM for a given individual’s PEM. If it were the case that the most accurate predictions of heightened negative emotional states were obtained by exclusively relying on one’s own data then we would expect that the PEM algorithm (data-driven search for the optimal weighting of IMs) would apply 100% weight to one’s own IM and 0% to the IMs of other individuals (as reflected by red shading only being present along the diagonal line), which is not the case. In summary, for most participants, states of heightened negative emotions are more accurately predicted when the statistical approach allows for the borrowing of information from other individual’s models (i.e., PEM) rather than exclusively relying on one’s own data (i.e., IM) to predict one’s negative emotional state. The Supplementary text provides additional details.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to test the extent to which data derived from passively collected smartphone sensors and a wrist-worn actigraphy band can predict states of heightened negative emotions among individuals with SMI. Results revealed that machine learning applied to passive data could predict negative emotional states significantly better than chance. Critically, these predictions relied solely on passively collected sensor data, requiring no user input. This is particularly critical given that self-report measures – especially EMA, which typically involves multiple assessments per day – may be quite burdensome for individuals with SMI. Passively collected data may offer a more unobtrusive and sustainable alternative for monitoring fluctuations in emotional and symptom states in the daily lives of individual.

To predict negative emotional states from passive smartphone and wrist-worn actigraphy data, we compared a range of different machine learning algorithms. Consistent with Ren et al. [15], random forest – a decision tree-based machine learning algorithm – outperformed both a simpler statistical approach (linear mixed effect model) and other machine learning approaches (support vector machines and elastic net)Footnote 1. The random forest model with the highest AUC (0.79) was for the prediction of loneliness, with an accuracy of 71% (sensitivity = 0.74 and specificity = 0.70) at the optimal cut-off. As a concrete example, assuming a participant was in the study for 200 days and on 50 of those days they experienced high levels of loneliness (the remaining 150 days were instances of low loneliness) then with a sensitivity of 74% our algorithm would be expected to accurately predict 37 out of 50 of those days of high loneliness. With a specificity of 70%, the algorithm would be expected to correctly predict that the participant had low levels of loneliness on 105 out of the 150 days. These predictions are significantly better than chance (50%) and, critically, are based solely on information derived from passively collected smartphone sensors. As a next step, a subsequent study could test the emotional benefits of “just-in-time” (JIT) smartphone-delivered interventions which are automatically triggered based on our random forest algorithm predicting high loneliness (and other negative emotional states) from passive smartphone data. The JIT intervention could be delivered via a text message or push notification, recommending an app-based mental health exercise such as brief behavioral activation, mindfulness, or cognitive reframing exercise. In addition, interventions could eventually be tailored to specific symptom-related behavioral patterns detected by passive sensors. For example, if passive data indicated a significant increase in time spent at home (detected via smartphone GPS) coupled with substantially reduced social contact (e.g., phone metadata revealing fewer calls and texts sent and received), a behavioral activation intervention could be triggered on the smartphone. As another example, if smartphone and wearable (e.g., smartwatch or smart ring) data detected maladaptive changes in sleep patterns—such as significantly later sleep onset, shorter sleep duration, or decreased sleep efficiency—a sleep hygiene intervention or CBT for insomnia intervention could be initiated.

The smartphone features that were most predictive of heightened negative emotional states were the GPS variables (see Fig. 2). These findings highlight the importance of location data – including metrics such as distance from home, percentage of time spent at home, and the number of locations visited – in enhancing the accuracy of predictions of negative emotional states. Notably, given the person-specific modeling approach, every individual can have a different ranking of which features were most predictive of their negative emotional states. In addition, there were also between-person differences in the direction of the association between a given predictor and outcome. For example, the relationship between accelerometer-measured activity levels and anxiety showed considerable variability from person to person. Some participants became more active when experiencing heightened anxiety, while others exhibited decreased activity. In contrast, the inverse relationship between GPS radius mobility—the smallest circle that encompasses all the locations a person visited during the day—and loneliness was more consistent across individuals. For most participants, a smaller radius of movement was associated with increased loneliness, suggesting that individuals who visited fewer locations or were more stationary during a given day tended to experience greater feelings of loneliness. The latter finding highlights the potential for using passive smartphone-derived mobility patterns as a relatively reliable indicator of loneliness. But overall, these results underscore the substantial heterogeneity in how individuals experience emotional states and the importance of adopting a person-specific approach in predictive modeling.

At the same time, our results also highlighted the benefits of borrowing information from the predictive models of other individuals. As shown in Fig. 3, an ensemble approach that searched for the optimal combination of person-specific models outperformed a fully idiographic approach (i.e., only using an individual’s own data to predict negative emotional states). This finding is consistent with previous research in adolescents [15], suggesting that borrowing information across individuals can enhance predictive accuracy. In practice, this means that by leveraging shared patterns across individuals, we can improve the reliability of predicting negative emotional states, even in cases where we have limited data from a single individual. These results suggest that predictive relationships between passive data features (e.g., GPS mobility patterns, activity levels) share common characteristics across sets of individuals. In other words, these relationships are not completely unique from person to person and future predictive algorithms will likely benefit from incorporating this fact of shared patterns into their modeling approach and, ultimately, into efficient JIT interventions.

Strengths of the study included: (1) daily assessments of negative emotions for over a year, on average (mean 465 days; total surveys collected = 12,959), (2) semi-continuous collection of multiple streams of passive data during the entire study period, (3) comparing the predictive performance of different machine learning approaches and a simpler statistical approach (linear mixed effects model), and (4) the comparison of ensemble vs idiographic (person-specific) modeling approaches to test whether incorporating information from other individuals’ models (i.e., an ensemble) outperforms a model that exclusively relies on one’s own data (i.e., an idiographic model) to predict heightened negative emotions.

The study also had several limitations. First, we had once daily assessments of affect. Multiple affect assessments per day would have provided a more granular view of fluctuations in emotions within a day. It should be noted that Ren et al. [15] had 2–3 emotion assessment per day (but over fewer days and in a smaller sample) and their findings were very similar to ours. Second, other smartphone features (e.g., call and text meta-data, or patterns of social media use) may help further improve accuracy in predicting negative emotions. Third, although our analyses were focused on within-person predictions and we had many (over 200 on average) assessment timepoints per participant, a larger sample size would have been beneficial. Fourth, findings relating to the sample of participants enrolled in this study may not necessarily generalize to the broader population of individuals with SMI (e.g., those responding to advertisements to participate in a study may differ meaningfully from those who do not see or respond to these ads). Fifth, the relatively small number of subjects in our study may reduce the reliability of the clustering analysis based on feature importance. Sixth, we note that PCA might not be the most appropriate dimension reduction technique for our dataset. This is evident from the reduced prediction accuracy of models relying solely on the PCs compared to those using both PCs and raw features as predictors. Finally, the watch data had high levels of missing data which was problematic for modeling (consequently, these results were reported in the supplement).

These limitations notwithstanding, there is now a growing body of research indicating that passive sensors from smartphones and wearables can predict states of heightened negative affect at the individual level which could inform the development and deployment of JIT interventions. The ultimate goal of this work is to deliver low-cost and scalable smartphone-delivered interventions when individuals are most in need (i.e., when they are predicted to be in the midst of a negative emotional state).

Data availability

Mass General Brigham requires IRB approval and a signed Data Use Agreement for data sharing. Please contact the corresponding author.

Notes

Random forest had similar performance to a more complex ensemble (PDEM) of machine learning approaches (i.e., a prediction algorithm that searched for the optimal weighting of each of the other algorithms) (mean AUC across emotions = 0.746 vs. 0.752, respectively). In other words, there was little additional benefit to adding other algorithms to random forest alone. This pattern of findings may be due to the fact that random forest can discover nonlinear associations and higher order interactions that may exist among the passive data features in predicting negative emotional states[19, 47, 48]. In contrast to linear mixed effects models, elastic net or SVM, these interactions and nonlinear associations do not need to be specified or tuned ahead of time in the model as the random forest decision tree algorithm effectively automatically searches for them.

References

Barlow DH, Curreri AJ, Woodard LS. Neuroticism and disorders of emotion: a new synthesis. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2021;30:410–7.

Fan R, Varol O, Varamesh A, Barron A, van de Leemput IA, Scheffer M, et al. The minute-scale dynamics of online emotions reveal the effects of affect labeling. Nat Hum Behav. 2019;3:92–100.

Verduyn P. Emotion duration. In: Waugh CE, Kuppens P, editors. Affect dynamics. Switzerland AG: Springer Nature; 2021. pp. 3–18.

Verduyn P, Delvaux E, Van Coillie H, Tuerlinckx F, Van Mechelen I. Predicting the duration of emotional experience: two experience sampling studies. Emotion. 2009;9:83.

Verduyn P, Van Mechelen I, Tuerlinckx F. The relation between event processing and the duration of emotional experience. Emotion. 2011;11:20.

Verduyn P, Van Mechelen I, Kross E, Chezzi C, Van Bever F. The relationship between self-distancing and the duration of negative and positive emotional experiences in daily life. Emotion. 2012;12:1248.

Verduyn P, Delaveau P, Rotgé J-Y, Fossati P, Van Mechelen I. Determinants of emotion duration and underlying psychological and neural mechanisms. Emot Rev. 2015;7:330–5.

Verduyn P, Lavrijsen S. Which emotions last longest and why: the role of event importance and rumination. Motiv Emot. 2015;39:119–27.

Webb CA, Israel ES, Belleau E, Appleman L, Forbes EE, Pizzagalli DA. Mind-wandering in adolescents predicts worse affect and is linked to aberrant default mode network–salience network connectivity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;60:377–87.

Consumer Affairs. How many Americans own a smartphone? 2024 ConsumerAffairs. 2023. https://www.consumeraffairs.com/cell_phones/how-many-americans-own-a-smartphone.html. Accessed 26 Jan2024.

Boukhechba M, Daros AR, Fua K, Chow PI, Teachman BA, Barnes LE. DemonicSalmon: monitoring mental health and social interactions of college students using smartphones. Smart Health. 2018;9:192–203.

Cai L, Boukhechba M, Wu C, Chow PI, Teachman BA, Barnes LE, et al. State affect recognition using smartphone sensing data. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/ACM international conference on connected health: applications, systems and engineering technologies. Washington, D.C: CHASE; 2018. p. 120–5. https://doi.org/10.1145/3278576.3284386.

Cao J, Truong AL, Banu S, Shah AA, Sabharwal A, Moukaddam N. Tracking and predicting depressive symptoms of adolescents using smartphone-based self-reports, parental evaluations, and passive phone sensor data: development and usability study. JMIR Ment Health. 2020;7:e14045.

Jacobson NC, Chung YJ. Passive sensing of prediction of moment-to-moment depressed mood among undergraduates with clinical levels of depression sample using smartphones. Sensors. 2020;20:3572.

Ren B, Balkind EG, Israel ES, Pastro B, Pizzagalli DA, Rahimi-Eichi H, et al. Predicting states of elevated negative affect in adolescents from smartphone sensors: a novel personalized machine learning approach. Psychol Med. 2023;53:5146–54.

Sequeira L, Perrotta S, LaGrassa J, Merikangas K, Kreindler D, Kundur D, et al. Mobile and wearable technology for monitoring depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: a scoping review. J Affect Disord. 2020;265:314–24.

Shah RV, Grennan G, Zafar-Khan M, Alim F, Dey S, Ramanathan D, et al. Personalized machine learning of depressed mood using wearables. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:1–18.

Rosellini AJ, Dussaillant F, Zubizarreta JR, Kessler RC, Rose S. Predicting posttraumatic stress disorder following a natural disaster. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;96:15–22.

Webb CA, Cohen ZD, Beard C, Forgeard M, Peckham AD, Björgvinsson T. Personalized prognostic prediction of treatment outcome for depressed patients in a naturalistic psychiatric hospital setting: a comparison of machine learning approaches. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2020;88:25–38.

Canzian L, Musolesi M. Trajectories of depression: unobtrusive monitoring of depressive states by means of smartphone mobility traces analysis. In: Proceedings of the 2015 ACM international joint conference on pervasive and ubiquitous computing. 2015. p. 1293–304. https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/2750858.2805845.

Jacobson NC, Bhattacharya S. Digital biomarkers of anxiety disorder symptom changes: personalized deep learning models using smartphone sensors accurately predict anxiety symptoms from ecological momentary assessments. Behav Res Ther. 2022;149:104013.

Lu J, Shang C, Yue C, Morillo R, Ware S, Kamath J, et al. Joint modeling of heterogeneous sensing data for depression assessment via multi-task learning. Proceedings of the ACM on interactive, mobile, wearable and ubiquitous technologies. 2018;2:1–21.

Moura I, Teles A, Viana D, Marques J, Coutinho L, Silva F. Digital phenotyping of mental health using multimodal sensing of multiple situations of interest: a systematic literature review. J Biomed Inform. 2023;138:104278.

Opoku Asare K, Moshe I, Terhorst Y, Vega J, Hosio S, Baumeister H, et al. Mood ratings and digital biomarkers from smartphone and wearable data differentiates and predicts depression status: a longitudinal data analysis. Pervasive Mob Comput. 2022;83:101621.

Pedrelli P, Fedor S, Ghandeharioun A, Howe E, Ionescu DF, Bhathena D, et al. Monitoring changes in depression severity using wearable and mobile sensors. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:584711. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.584711.

Pratap A, Atkins DC, Renn BN, Tanana MJ, Mooney SD, Anguera JA, et al. The accuracy of passive phone sensors in predicting daily mood. Depress Anxiety. 2019;36:72–81.

Saeb S, Zhang M, Karr CJ, Schueller SM, Corden ME, Kording KP, et al. Mobile phone sensor correlates of depressive symptom severity in daily-life behavior: an exploratory study. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e175. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4273.

Saeb S, Lattie EG, Kording KP, Mohr DC. Mobile phone detection of semantic location and its relationship to depression and anxiety. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2017;5:e112.

Wahle F, Kowatsch T, Fleisch E, Rufer M, Weidt S. Mobile sensing and support for people with depression: a pilot trial in the wild. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016;4:e111.

Nepal S, Wang W, Vojdanovski V, Huckins JF, Dasilva A, Meyer M. et al. COVID studentstudy: A year in the life of college students during the COVID-19 pandemic through the lens of mobile phone sensing. In Proceedings of the 2022 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems. 2022. p. 1–19. https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3643501.

Antczak D, Lonsdale C, del Pozo Cruz B, Parker P, Sanders T. Reliability of GENEActiv accelerometers to estimate sleep, physical activity, and sedentary time in children. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2021;18:73.

Fuller D, Colwell E, Low J, Orychock K, Tobin MA, Simango B, et al. Reliability and validity of commercially available wearable devices for measuring steps, energy expenditure, and heart rate: systematic review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8:e18694.

Plekhanova T, Rowlands AV, Davies MJ, Hall AP, Yates T, Edwardson CL. Validation of an automated sleep detection algorithm using data from multiple accelerometer brands. J Sleep Res. 2023;32:e13760.

Case MA, Burwick HA, Volpp KG, Patel MS. Accuracy of smartphone applications and wearable devices for tracking physical activity data. JAMA. 2015;313:625–6.

Gao Z, Liu W, McDonough DJ, Zeng N, Lee JE. The dilemma of analyzing physical activity and sedentary behavior with wrist accelerometer data: challenges and opportunities. J Clin Med. 2021;10:5951.

Germini F, Noronha N, Debono VB, Philip BA, Pete D, Navarro T, et al. Accuracy and acceptability of wrist-wearable activity-tracking devices: systematic review of the literature. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24:e30791.

Elhai JD, Dvorak RD, Levine JC, Hall BJ. Problematic smartphone use: a conceptual overview and systematic review of relations with anxiety and depression psychopathology. J Affect Disord. 2017;207:251–9.

Torous J, Kiang MV, Lorme J, Onnela J-P. New tools for new research in psychiatry: a scalable and customizable platform to empower data driven smartphone research. JMIR Ment Health. 2016;3:e16.

Onnela J-P, Rauch SL. Harnessing smartphone-based digital phenotyping to enhance behavioral and mental health. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:1691–6.

Rahimi-Eichi H, Coombs G, Onnela J-P, Baker JT, Buckner RL. Measures of Behavior and life dynamics from commonly available GPS data (DPLocate): algorithm development and validation. medRxiv:2022.07.05.22277276. 2025. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.07.05.22277276v1.

Rahimi-Eichi H, Iii GC, Bustamante CMV, Onnela J-P, Baker JT, Buckner RL. Open-source longitudinal sleep analysis from accelerometer data (DPSleep): algorithm development and validation. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2021;9:e29849.

Buuren S, van, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45:1–67.

Miles A. Obtaining predictions from models fit to multiply imputed data. Sociol Methods Res. 2016;45:175–85.

Henderson CR. Best linear unbiased estimation and prediction under a selection model. Biometrics. 1975;31:423–47.

Ren B, Patil P, Dominici F, Parmigiani G, Trippa L. Cross-study learning for generalist and specialist predictions. arXiv:200712807 [math, stat] 2025. http://arxiv.org/abs/2007.12807. Accessed 23 Aug 2021.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, N.J: Routledge; 1988.

Boehmke B, Greenwell BM. Hands-on machine learning with R. 1st ed. Boca Raton: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2019.

Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Friedman J. The elements of statistical learning: data mining, inference, and prediction. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2017.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NIMH U01MH116925 (JTB). The first author (CAW) was partially supported by NIMH R01MH116969, NCCIH R01AT011002, the Tommy Fuss Fund and a Young Investigator Grant from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JB acquired funding for the project. CW, JB, BR, HR, and JB conceptualized the study. HR, BG, YC, and JT acquired and processed the data. CW, HR, and BR processed and analyzed the data. All authors contributed to interpretation of findings and drafting the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

CAW has received consulting fees from King & Spalding law firm. JTB has received consulting fees from Tetricus, Inc., Sama Therapeutics, Inc, Niraxx Therapeutics, Inc., and Mindstrong Health, Inc.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Webb, C.A., Ren, B., Rahimi-Eichi, H. et al. Personalized prediction of negative affect in individuals with serious mental illness followed using long-term multimodal mobile phenotyping. Transl Psychiatry 15, 174 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03394-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03394-4

This article is cited by

-

Multimodal prediction of future depressive symptoms in adolescents

BMC Psychiatry (2025)