Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients and AD mouse models usually have cognitive impairments, such as significant spatial memory deficits, which are coupled with dysregulation in the structure and function of neural circuits. The medial mammillary body (MM) is associated with spatial memory, and its dysfunction emerges in early AD. However, the link between spatial memory deficits and MM dysfunction remains unclear. Here, by combining c-Fos mapping with optogenetic stimulation, we found the MM was involved in the retrieval of object-location memory. Furthermore, using viral tracing, we demonstrated the axonopathy of MM neurons in the thalamus in the early stages of AD mouse model. Fiber photometry revealed that neuronal activity of MM neurons showed distinct responses to objects in different locations. However, neuronal activity was significantly reduced during the object-location memory retrieval phase in AD mice. Activating MM neurons in AD mice through optogenetic manipulation rescues the object-location memory impairment. Together, our results highlight the importance of MM dysfunction in AD, which may serve as a foundation for further exploration of new targets in AD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a classic neurodegenerative disorder characterized by amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, along with synaptic deficits and neural excitatory-inhibitory (E-I) imbalance [1]. These pathological injuries disrupt the normal structure and function of neural circuits, especially the memory-related Papez circuit, which includes the hippocampus, mammillary body, and anterior thalamus nucleus (ATN) [2,3,4]. This disruption ultimately leads to spatial memory impairments [4]. Numerous studies have indicated a significant correlation between hippocampal injuries and spatial memory deficits in AD. However, the mechanisms underlying the interactions between subcortical memory-related brain regions and spatial memory deficits in AD remain inadequately understood.

The medial mammillary body (MM) is one of the crucial brain regions of the Papez circuit, which plays a significant role in higher cognitive functions, such as reference memory, working memory, and spatial memory [5,6,7,8]. Based on the Papez circuit, studies have shown that the MM is a major downstream projection target area of the hippocampus. Almost all neuronal activity in the MM is synchronized with theta rhythms in the hippocampus, which regulate spatial information [7, 9, 10]. For instance, the theta activity of neurons in the MM is suppressed due to damage to the medial septal nuclei, which reduces hippocampal theta rhythms [11]. However, the MM also receives projections from other brain regions, such as the ventral tegmental nucleus, therefore, afferent information from these regions may also be involved in modulating spatial memory [12]. In addition, damage to the MM or mammillothalamic tract results in spatial memory deficits in rats [12, 13]. These studies suggest that the MM, an essential component of the Papez circuit, receives and integrates inputs from various brain regions, and subsequently transmits these processed messages to different nuclei in the ATN, which are involved in the modulation of spatial memory [9]. Both magnetic resonance imaging and pathological tissue staining have revealed that the MM in patients with AD is significantly reduced in size and positively correlates with spatial memory deficits in patients [14,15,16]. Studies from animal models of AD have identified the MM as one of the earliest brain regions to show amyloid plaques and axonal damage. Furthermore, hyperexcitation of neurons in the MM has been observed in AD and modulating MM neurons can alleviate the pathological features of AD [17, 18]. These studies suggest that MM neuronal dysfunction is closely related to spatial memory impairments in AD; however, the neural circuit mechanism remains unclear.

To explore the neural circuit mechanism of spatial memory impairment caused by damage to the MM in AD models, combined viral tracing, fiber photometry, and optogenetic manipulation, we revealed the dynamic activity changes of MM neurons during the object-location memory retrieval and their dysfunction in AD. Our findings highlight the critical contribution of MM dysfunction to spatial memory deficits in AD.

Methods

Animals

All recordings and behavioral experiments were conducted using 2–3-month-old adult male C57BL/6J mice and 2–6-month-old 5xFAD mice (The Jackson Laboratories, RRID: MMRRC_034848-JAX). Mice were provided with ad libitum feeding and housed under a 12:12-h light/dark cycle (lights on at 8:00 a.m.). Before the start of each experiment, we wrapped the mice in a soft towel to habituate the experimenter for 3 days. All experimental procedures were conducted under the guidelines set forth by the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals at Chongqing Medical University (IACUC-CQMU-2024-0919).

Behavioral assays

All behavioral tests were conducted during the light phase. All test mice were transferred to the testing room 3 days prior to behavioral testing. Behavioral data were automatically tracked using EthoVision XT 17.0 (Noldus). The animals were randomly assigned to the control and experimental groups in the present study, and the investigator was blinded to the behavior experiments.

Open Field Test (OFT)

The OFT was used to evaluate the locomotor ability, anxiety levels, and exploratory behavior of mice. The animals were placed in an open field arena (40 × 40 × 40 cm) for 10 min. The central zone was defined as a 20 × 20 cm area, with the remaining space designated as the outer zone. The total distance, speed, and time spent in the central zone were recorded.

Elevated Plus Maze (EPM)

The EPM was used to assess the anxiety levels of mice. The apparatus consisted of two open arms (25 × 7 cm) and two closed arms (25 × 7 cm with 16 cm-high walls in height), positioned 70 cm above the floor. Mice experience a conflict between exploration and avoidance in open arms, reflecting anxiety. Each mouse was placed in the central area facing an open arm, and entries into the open/closed arms, time spent and distance traveled were recorded.

Object Location Test (OLT)

The OLT exploits mice’s innate preference for exploring objects in novel locations to assess spatial memory. The experiment included three phases: 1. Habituation phase: Mice were placed in an open field without any objects for 10 min daily over two consecutive days. 2. Encoding phase: two identical objects (named object-A and object-B, respectively) were placed in fixed locations. The mice were allowed to explore freely for 10 min, and the exploration times for both objects were recorded. 3. Retrieval phase: After 24 h, one object was moved to a new location (displaced-object), while another remained unchanged (unmoved-object). The mice explored the open field freely for 10 min as before. For optogenetic manipulation, mice received either 10 min of optogenetic activation or inhibition during retrieval. Object-location memory was quantified using the object recognition index calculated with the formula: Object recognition index = Tdisplaced ÷ (Tunmoved + Tdisplaced).

Virus injection

After anesthesia with 5% isoflurane, the mice were placed on a heating pad inside a stereotaxic instrument, receiving a consistent oxygen flow of 1 L/min while being sustained with 1.0–1.5% isoflurane. Stereotaxic coordinates were based on the second edition of The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates, with the following the anteroposterior (AP), mediolateral (ML), and dorsoventral (DV) coordinates used in our experiments: MM (−2.64, ±0.40, −5.25); AV (−0.60, ±1.00, −3.50); AM (−0.50, ±0.63, −4.10). All viruses were purchased from BrainVTA Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China or Taitool Bioscience Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China. Cranial windows were created via dental drilling, and viruses were delivered at a rate of 0.5nL/s using glass electrodes attached to a microinjection system. Post-injection, the micropipette remained at the injection site for 10 min, was lifted by 10 µm, and held for an additional 10 min before slow withdrawal.

For optogenetic inhibition of the MM neurons of C57BL/6J mice, 200 nL rAAV2/9-cfos- CreERT2 (5E + 12 vg/ml) and 150 nL rAAV2/9-EF1α-DIO-eNpHR3.0-mCherry (5E + 12 vg/ml) were injected to the MM. To test the specificity of tamoxifen and Cre recombination, 200 nL rAAV2/9-cfos- CreERT2 (5E + 12 vg/ml) and 150 nL rAAV2/9-EF1α-DIO- mCherry (5E + 12 vg/ml) were injected to the MM in C57 mice.

For optical fiber-based Ca2+ recording in the MM, 200 nL rAAV2/9-CAG-GCaMP6S (1E + 13 vg/ml) was injected into the MM of 5xFAD mice and C57BL/6J mice.

To optogenetic activation of the MM neurons of 5xFAD mice, 150 nL rAAV2/9-hSyn-ChrimsonR-mCherry (5E+12vg/ml) were delivered to the MM.

To map the projection of MM neurons, 200 nL rAAV2/9-EF1α-EGFP was injected into MM. For mapping co-projections of the MM neurons to AV and AM, 100 nL RV-N2C(G)-ΔG-mCherry (1.50E + 08 IFU/mL) and RV-N2C(G)-ΔG-EGFP (1.50E + 08 IFU/mL) were injected into the AV and AM of C57BL/6J mice at 15-week-old, respectively. To label the presynaptic elements, 200 nL rAAV2/9-hSyn-EGFP.PreSynapses-T2A-EBFP2 was injected into the MM of C57BL/6J mice. To map axonal damage of MM neurons in 5xFAD mice, 200 nL rAAV2/9-hSyn-EGFP was injected into the MM of 12-week-old 5xFAD mice and C57BL/6J mice, respectively. The diameter of axonopathic swellings was defined as larger than 3 μm [18].

Optical fiber-based Ca2+ recording

As described previously [19], the neuronal calcium signals were recorded by the three-wavelength fiber photometry system (Thinker Tech Nanjing Biotech CO., Ltd). An optical fiber (diameter, 200 μm, NA = 0.37) was implanted into MM. The calcium signals from both unmoved and displaced objects were recorded simultaneously. The laser intensity at the tip of the optic fiber was adjusted to 30–40 μW. Exploration onset was defined as the mouse’s head entering a 2 cm radius around objects. Video and calcium signals were synchronized using EthoVision XT 17. Baseline activity was defined as −2–0 s before exploration [20].

Optogenetics

The optical fiber (diameter, 200 μm, NA = 0.37, Newdoon Inc. China) was implanted 100 μm above the MM injection site. One end of the optic fiber was connected to a rotary joint on the chamber ceilings, and the other end was connected to the mouse implant during habituation and testing.

TRAP2 labelling for optogenetics inhibition: Previous study showed that targeted recombination in active populations (TRAP) - the tamoxifen (TM) dependent Cre recombinase CreERT2- was sensitive to neuronal activation 23–24 h after TM injection [21]. In this study, three weeks after the virus injection, tamoxifen (sigma, T5648-1G, 20 mg/mL) was injected intraperitoneally to induce the Cre recombination (150 mg/1 kg body weight), followed by encoding testing. After 24 h, mice were subjected to retrieval testing (phase1). This strategy allowed us to specifically manipulate these neurons that activated during the retrieval phase. After 2 weeks, mice were subjected to encoding and retrieval testing (phase2). Inhibition used a continuous 589 nm laser with power at the fiber tip was 5–6 mW during retrieval testing (phase2). After 2 weeks, mice were subjected to encoding and retrieval testing (phase3) without optogenetics inhibition.

For activation, the experimental process of optogenetic activation is similar to that of optogenetic inhibition, but without TM. Laser power at the fiber tip was 8–10 mW (12 Hz, 10 ms pulse width) during retrieval testing (phase2) as previous study [22].

Immunofluorescence staining

Tissue perfusion and fixation: After mice were anesthetized with Tribromoethanol (30 μl/g, MeilunBio CAS 75-80-9), the chest wall was opened to expose the heart, followed by perfusion with 1 × PBS (Servicebio, G0002). The skull was cut open, the brain was isolated and then immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 24 h. The mouse brain was dehydrated using a gradient of sucrose solution at concentrations of 20 and 30% over the next 4 days so that the brain sank to the bottom of the sucrose solution. Next, the surface of the mice’s brains was wiped dry with filter paper. The brain was then embedded in an optimal cutting temperature compound (Tissue-Tek O.C.T. Compound 4583) and sliced on a cryostat (50 µm per slide), the cell membrane was permeabilized using PBST (0.25% Triton X-100, Beyotime P0096). It was blocked with 10% donkey serum and subsequently stained as desired.

The brain slides were stained with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C: Anti-c-Fos (1:5000, synaptic systems c-Fos antibody-226380), Anti-PSD-95 (1:400, Cell Signaling 3450), anti-Aβ (X-34, Sigma SML1954), anti-tau (1:500, Thermo Fisher MN1020) and Anti-Neun antibody (1:1000, Sigma MAB377). After staining, the slides were washed with 1 × PBS 3 times for 10 min each time and then incubated with a fluorescent secondary antibody (1:500, sigma, Fluoro-488 Donkey anti-Guinea, SAB4600033; 1:500, Fluoro-594 Donkey anti-rabbit, ThermoD, A-21207; 1:500, Fluoro-647 Donkey anti-mouse ThermoD A-31571; and 1:500, Fluoro-488 Donkey anti-mouse, ThermoD, A-21202) at room temperature for 1 h. After that, the antibody was washed with 1 × PBS 3 times. The DAPI (Beyotime C1006) was then stained for 10 min at room temperature, washed with 1 × PBS, and mounted a specimen on a slide.

The DANIR-8c (Beijing Shihong Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, 072701) was used to label amyloid plaques as previous study [23]. Coronal sections of 5×FAD mouse brains were cut to a thickness of 70 μm and rinsed 3 times for 10 min with 1x PBS. Following the rinsing, the brain slices were stained with a 0.01 mol/mL DANIR-8c solution for 8 min at 4 °C, protected from light. The slices were then rinsed in a 50% ethanol solution for 3 min, followed by three rinses with PBS solution. Finally, the stained brain slices were mounted and imaged with a slide scanner (Olympus VS120) or a confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, LSM710).

Data analysis and statistics

No results were included that were not observed in multiple animals in this study and results throughout the paper were reproduced. All experimental data were analyzed for statistical significance with GraphPad Prism version 9.5.1 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, United States). All measurements were listed as Mean ± SEM. To compare between groups, two-way or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and associated multiple comparison tests were employed. A paired t-test was used for paired statistics. All experiments were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Identification of MM engaged in object-position memory

Memory refers to the neurobiological processes encompassing information encoding, consolidation, and retrieval [24]. Previous research has established the involvement of MM neurons in spatial memory [25]. To validate this mechanism, we conducted OLT with adult C57BL/6J mice (Fig. 1A). Consistent with previous finding [26], the mice exhibited a higher object recognition index for displaced object compared to unmoved object (Fig. 1B). To elucidate the temporal dynamics of neuronal activation, we conducted immunohistochemical analyses of the immediate early gene c-Fos expression in brain tissues harvested 90 min post-encoding and post-retrieval phases, respectively. Quantitative assessments revealed a significantly elevated density of c-Fos+ neurons in the MM during memory retrieval compared to the encoding phase in C57BL/6J mice (Fig. 1C–E). Additionally, the Anteroventral nucleus (AV) and Anteromedial nucleus (AM), which are downstream regions of the MM, also exhibited significant neuronal activation during both spatial encoding and retrieval phases (Fig. 1C–E). These findings collectively demonstrate that the MM plays a predominant role in object-location memory retrieval, while its associated thalamic nuclei participate in both mnemonic processing stages.

A. Schematic representation of OLT. B. Heatmap for the activity of C57BL/6J mice during the retrieval phase of the OLT (left), and object recognition index of unmoved object and displaced object, n = 6, paired two-tailed t-test. C and D. c-Fos expression in neurons of the MM (left), AM and AV (right) in C57BL/6J mice during the encoding phase (C) and during retrieval phase (D). E. Quantification of c-Fos+ neurons in MM, AM, and AV of C57BL/6J mice during the encoding and retrieval phases of OLT. Encoding phases n = 10; retrieval phases, n = 13. Unpaired two-tailed t-test. F. Scheme of virus injecting in MM (top). Confocal images of labeled neurons in MM, and their downstream in AM, and AV (bottom). Scale bar: 200 μm. G. Object recognition index of C57BL/6J mice before, during and after optogenetic inhibition of the MM neurons, n = 8, One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. All data are listed as the Mean ± SEM.

Emerging evidence indicates that experience-activated neuronal ensembles undergo plasticity-dependent consolidation to form engram cell networks, which exhibit cue-responsive reactivation during memory recall [27]. To interrogate the functional necessity of MM neurons in spatial memory retrieval regulation, we employed a dual-virus strategy combining AAV2/9-cfos- CreERT2 with cre-dependent optogenetic silencing vector AAV2/9-DIO-eNpHR3.0-mCherry. We delivered the virus to MM via stereotaxic injection (Fig. 1F). Previous study had showed that targeted recombination in active populations (TRAP) - the tamoxifen (TM) dependent Cre recombinase CreERT2- was sensitive to neuronal activation 23–24 h after TM injection [21]. Tamoxifen was used to induce Cre expression, followed by encoding testing. This strategy allowed us to specifically manipulate these neurons that activated during the retrieval phase. Behavioral quantification revealed intact spatial novelty preference in control conditions, with subjects exhibiting a significantly elevated discrimination index for displaced object versus unmoved object (Fig. 1G). Crucially, after two weeks, optogenetic inhibition of MM engram ensembles during the retrieval phase induced profound deficits in spatial discrimination, manifesting as attenuated exploration time toward displaced object and significantly reduced discrimination index (Fig. 1G). Remarkably, this cognitive impairment exhibited full reversibility, with discrimination capacity returning to baseline levels two weeks post-silencing (Fig. 1G). To test the specificity of tamoxifen and Cre recombination, we conducted three sets of control experiments: AAV2/9-cfos-CreERT2 + TM (Supplementary Fig. 1A, B); AAV2/9-cfos-CreERT2 + AAV2/9-DIO-eNpHR3.0-mCherry (Supplementary Fig. 1C, D); and AAV2/9-cfos-CreERT2 + AAV2/9-DIO-eNpHR3.0-mCherry + TM (Supplementary Fig. 1E, F). All viruses were injected into the MM of C57BL/6J mice. Then, mice were subjected to OLT. The results showed that only mice that received injection both TM and the virus (including AAV2/9-cfos-CreERT2 + AAV2/9-DIO-eNpHR3.0-mCherry) expressed mCherry (Supplementary Fig. 1). These data conclusively demonstrate that MM neuronal populations are indispensable for the dynamic implementation of object-location memory retrieval while maintaining system-level plasticity for subsequent mnemonic information processing.

A view of the projection patterns of MM

Previous neuroanatomical studies have established that MM efferents form topographically organized projections to anterior thalamic nuclei (ATN) via the mammillothalamic tract (MTT), a critical pathway mediating spatial cognition and head-direction signal integration [25]. Building upon this framework, our investigation revealed co-activation patterns in MM, AM, and AV during object-location memory processing. Thus, to systematically map structural connectivity between these regions we injected expressed enhanced green fluorescent protein virus AAV2/9-EF1α-EGFP into the MM. Postmortem analysis following a 3-week viral expression period demonstrated precise MM-restricted transduction, viral expression was confined to the MM, with axon terminals predominantly localized to the ipsilateral AV, AM, and dorsal tegmental nucleus of Gudden (Fig. 2A). To further investigate the distribution pattern of MM projections, we performed complementary retrograde tracing strategies by employing unilateral AM injections of RV-EGFP and contralateral AM injection of RV-mCherry. Histology results revealed strictly ipsilateral MM-originating projections to AM (Fig. 2B). A similar connectivity pattern was also recapitulated in MM-AV circuitry (Fig. 2C). To determine whether the same populations of MM neurons project to the AV and AM, dual retrograde tracing via simultaneous RV-mCherry (AM-targeted) and RV-EGFP (ipsilateral AV-targeted) injections uncovered spatial segregation of MM subpopulations: AM-projecting neurons occupied anteromedial MM domains, whereas AV-targeting populations localized to posterolateral MM domains (Fig. 2D–E). To further confirm the connection between the MM and ANT at the synaptic-level, we implemented a presynaptic marker system AAV2/9-hSyn-EGFP.PreSynapses-T2A-EBFP2 to label the presynaptic elements of MM neurons (Fig. 2F). After 6 weeks of viral expression, the brains were perfused and collected. Subsequent analysis revealed a significant presynaptic apposition from MM neurons onto thalamic targets, with dense terminal arborizations observed in both AV and AM (Fig. 2G). Together, these results suggested that MM forms independent subcircuits with distinct subregions of the ATN.

A. Distribution of axon terminals of MM neurons throughout the whole brain, n = 3, scale bar: 1 mm. B and C. Schematic diagram of RV-EGFP and RV-mCherry retrograde virus in AM (B) and AV (C) bilaterally, respectively (top), and RV-labelled MM neurons (bottom). n = 3, Scale bar: 500 μm. D. Diagram of retrograde virus tracing: RV-EGFP into AV and RV-mCherry into ipsilateral AM (left) and confocal image in AV and AM (right). n = 3, Scale bar: 1 mm. E. Confocal images of AM and AV retrograde virus in MM along the anterior-posterior axis. Scale bar: 500 μm. F. Diagram of synapses-labeled with virus tracing. G. Visualization of the synaptic terminal distribution in the AV and AM. n = 3, Scale bar: 500 μm.

Behavioral and Pathological changes in 5xFAD mice

The 5xFAD transgenic mouse model exhibits accelerated AD-type neuropathological progression compared to conventional amyloidogenic models, with amyloid-β plaque deposition initiating at ~1.5 postnatal months, followed by progressive synaptic dysfunction and hippocampal-dependent spatial memory deficits emerging by 4 months [28]. Additionally, a reduced anxiety phenotype is observed by 6 months of age age [29]. To systematically characterize the behavioral phenotype of 16-week-old 5xFAD mice, we conducted a multimodal behavioral battery encompassing the OFT, EPM and OLT. Quantitative locomotor analysis in OFT revealed preserved ambulatory capacity in 5xFAD mice, with total movement distance and velocity profiles indistinguishable from age-matched C57BL/6J controls, which indicated that 5xFAD mice did not exhibit deficits in motor ability (Fig. 3A). However, the EPM revealed a lower anxiety level in 5xFAD mice compared to C57BL/6J mice, demonstrated by a longer duration spent in the open arms (Fig. 3B). More importantly, OLT cognitive testing uncovered substantial spatial memory retrieval impairments, with 5xFAD mice displaying a reduction in spatial discrimination index compared to controls during the retrieval phase (Fig. 3C), These findings collectively demonstrate that 5xFAD mice recapitulate core AD-relevant behavioral trajectories—preserved motor function, reduced anxiety-like behavior, and selective spatial memory retrieval deficits—at this prodromal disease stage.

A. Heatmap for the activity of 5xFAD mice and C57BL/6J mice in OFT (left) and the total distance they moved (right), C57, n = 21; 5xFAD, n = 17. Unpaired two-tailed t-test. B. Heatmap for the activity of 5xFAD mice and C57BL/6J mice in the EPM (left), and the time duration in open arms (right), C57BL/6J, n = 26; 5xFAD, n = 31. Unpaired two-tailed t-test. C. Heatmap for the activity of 5xFAD mice and C57BL/6JBL/6J mice in the OLT (left), and the discrimination index in 6 h and 24 h after encoding (right), C57BL/6J-6h, n = 9; 5xFAD-6h, n = 13, C57BL/6J-24h, n = 16; 5xFAD-24h, n = 13. Unpaired two-tailed t-test. D. Staining of amyloid plaques in 2-month-old 5xFAD mice and 4-month-old 5xFAD mice (left) and statistical result (right). Scale bar: 200 μm, 2 M, n = 6; 4 M, n = 4. Unpaired two-tailed t-test. E. Staining neurons of MM in 4-month-old 5xFAD mice and C57BL/6J mice (left) and the statistical result of neuronal density (right). Scale bar: 200 μm, C57BL/6J, n = 4; 5xFAD, n = 6. Unpaired two-tailed t-test. F. Schematic diagram of AAV2/9-hSyn-mCherry labeling of MM neurons in 4-month-old 5xFAD mice and C57BL/6J mice. G and J. The confocal images of axonopathy of MM neurons in AM and AV in 4-month-old 5xFAD mice (G) and C57BL/6J mice (J). Scale bar: 200 μm. H and I. The magnifications of axonopathy in AM (H) and AV (I) in 5xFAD mice from G. K and L. The magnifications of axonal terminals in AM (K) and AV (L) in C57 mice from G. Scale bar: 50 μm. M. Quantitative analysis of axonopathy in AV and AM of 5xFAD mice, respectively. n = 8, Unpaired two-tailed t-test. All data are listed as the Mean ± SEM.

To investigate the AD-related pathological changes in the MM, we performed quantitative neuropathological assessments of Aβ plaques in MM of 5xFAD mice. The results showed increased deposition of Aβ plaques with increasing age (Fig. 3D). As previous study reported that neurons lose in AD [30]. To study whether neurons in MM also decreased, we performed immunochemical staining to quantify the number of neurons in MM. The result showed that the number of neurons in MM of 16-week-old 5xFAD mice was similar to the age-matched C57BL/6J mice (Fig. 3E).

Previous study has shown that Aβ plaque accumulation could disrupt the transport of cargos in axons and lead to axonopathy and synaptic loss [2]. To investigate whether there is axonal damage of MM neurons in 5xFAD mice, we injected AAV2/9-hSyn-EGFP into the MM of 12-weeks-old 5xFAD mice and C57BL/6J mice, respectively (Fig. 3F). After four weeks of viral expression virus, we observed profound axonal pathology, characterized by the axons with swellings or spheroids in the AV and AM of 5xFAD mice, while this phenomenon was not observed in the C57BL/6J mice. (Fig. 3G–M). In addition, we performed immunofluorescence staining for PSD-95 and tau. We observed pronounced puncta of PSD-95 and tau in the MM brain region of 5xFAD mice, a phenomenon not detected in control mice (Supplementary Fig. 2). These results indicated that the spatial memory deficits in 5xFAD mice are likely attributed to synaptic damage of MM neurons.

Optogenetic regulation of MM neurons rescued object-location memory in 5xFAD mice

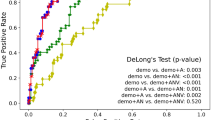

Our integrated findings from c-Fos neuronal activation mapping, optogenetic silencing, and anterograde viral tracing establish a tripartite mechanistic framework: (1) MM engram ensembles are dynamically recruited during object-location memory retrieval; (2) 5xFAD mice exhibit MM-ATN axonal dystrophy concomitant with spatial memory deficits; and (3) MM network hypofunction directly correlates with impaired spatial discrimination. To interrogate the causal relationship between MM circuit dysfunction and cognitive decline, we performed in vivo calcium imaging via stereotaxic delivery of AAV2/9-CAG-GCamp6s into MM of 5xFAD mice and C57BL/6Jmice at 12 weeks old, respectively (Fig. 4A). Then, we conducted fiber photometry to record Ca2+ activity in MM neurons when the mice were subjected to explore objects with different locations during the retrieval phase in OLT (Fig. 4B). We found that during the memory retrieval phase, MM neurons showed stronger Ca2+ activity when C57BL/6J mice approached the unmoved object compared to the displaced object (Fig. 4C, E). However, there was no difference in the Ca2+ activity when the 5xFAD mice explored the objects in different locations (Fig. 4D, E). More importantly, further analysis of dynamic changes in MM neuronal activity revealed significantly increased calcium signaling in response to displaced object in 5xFAD mice compared to that in C57BL/6J mice (Fig. 4E). In addition, calcium signaling of MM neurons to unmoved object significantly decreased compared to C57BL/6J mice, although the difference is not significant (Fig. 4E). These results indicated that MM participates in spatial memory retrieval, which showed different responses to the two objects in different locations in normal condition. The different response was diminished in AD model.

A. The experimental strategy of optical fiber-based Ca2+ recording in the MM neurons. AAV2/9-CAG-GCaMP6s into the MM of C57BL/6J and 5xFAD mice at 12 weeks old, and the optical fiber was implanted in the MM (left). One example image showed the optical fiber position in the MM (right). Scale bar: 500 μm. B. The experimental procedure of OLT with fiber photometry. C and D. Heatmap of fluorescence signals of MM neurons when mice approached to unmoved-object (up) and displaced-object (bottom) during the retrieval phase of C57BL/6J mice (C) and 5xFAD mice (D). Peri-event plot of average fluorescence changes of MM neurons when mice approached to unmoved-object and displaced-object during the retrieval phase (right) of C57BL/6J mice (C) and 5xFAD mice (D). Thick lines indicate the mean, and shaded areas indicate the SEM. C57BL/6J, n = 10, 5xFAD, n = 7. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. E.Quantitative analysis of the mean fluorescence signals between unmoved-object and displaced-object during the retrieval phase of C57BL/6J mice and 5xFAD mice. All data are listed as the Mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. C57BL/6J, n = 10, 5xFAD, n = 7. F. The experimental strategy of activation of t the MM neurons in 5xFAD mice. AAV2/9-hSyn-ChrimsonR-mCherry was injected into the MM of 5xFAD mice at 12 weeks old, and the optical fiber was implanted in the MM (left). One example image showed the optical fiber position in the MM (right). Scale bar: 500 μm. G. Statistical plots of object-location recognition index (left) and distance (right) measured before, during and after optogenetic activation of MM neurons in the retrieval phase, with two-week intervals between sessions, n = 8. Two-tailed paired t-test. All data are listed as the Mean ± SEM.

Next, we investigated whether artificial activation of the MM neurons could rescue the object-location memory retrieval deficit in 5xFAD mice. To address this, we injected AAV2/9-hSyn-ChrimonR-mCherry into the MM of 5xFAD mice and implanted an optic fiber 70 µm above the viral injection site for optogenetic activation (Fig. 4F). As expected, before activating the MM neurons, the 5xFAD mice showed obvious spatial memory impairment. However, when the MM neurons were activated through optogenetics, 5xFAD mice significantly enhanced discrimination for the displaced object during the object-location retrieval phase. Interestingly, two weeks after the activation, we re-tested the spatial memory ability of the 5xFAD mice. The results showed that the recognition index of the AD mice had significantly decreased (Fig. 4G), indicating that the activation of MM neurons could rescue the object-location memory retrieval deficit in AD model.

Discussion

Spatial memory impairments in AD are mechanistically linked to dysregulation of the Papez circuit evolutionarily conserved limbic network, including the hippocampus, mammillary body, thalamus and dentate gyrus [31]. The hippocampal CA1 subregion mediates spatial learning in rodents, as evidenced by significant reductions in target location memory following its pharmacological inactivation [32]. While the relationship between hippocampal lesions and spatial memory deficits has been extensively characterized, the circuit-level mechanisms linking subcortical structural damage to AD-related mnemonic decline remain poorly understood. Combining c-Fos activity mapping, viral tract tracing, and closed-loop optogenetics, we demonstrate functional recruitment of MM neurons during object-location memory retrieval. With fiber photometry, we uncovered calcium dysregulation in MM neurons correlates with retrieval deficits in AD model. Optogenetic activation of these neurons restores spatial discrimination capacity in AD model. Together, these findings establish a novel pathophysiological framework wherein MM dysfunction contributes to object-location memory retrieval deficits in neurodegenerative disorders.

During early AD progression, the Papez circuit exhibits heightened vulnerability, with subcortical components developing Aβ deposits, pathological tau aggregates, and aberrant neural activity accompanied by presynaptic terminal loss [17]. These pathophysiological alterations disrupt Papez circuit information transfer, precipitating cognitive-behavioral deficits including spatial memory impairment [2]. Our investigation revealed that 5xFAD mice exhibit amyloid plaque deposition in the MM during prodromal AD stages, concomitant with spatial memory deficits and anxiety-like phenotypes. Aβ plaques specifically within the MM region have been reported to disrupt axonal cargo transport, leading to axonopathy and synaptic loss [33]. We found that tau aggregates in dystrophic neurites and pronounced puncta of PSD-95 surrounding Aβ plaques. We also identified synaptic pathology in MM neurons, characterized by axonal terminal swelling and dystrophic neurites, despite preserved neuronal density. Our findings provide direct evidence implicating Aβ-driven pathology in this region [34]. The 5xFAD model was selected for its rapid Aβ plaque development in subcortical regions [17, 28], allowing efficient investigation of amyloid-associated synaptic alterations in the MM region – a key focus of this manuscript. While our study leveraged the 5xFAD model to probe amyloid-specific mechanisms in the MM region, we agree that comparisons with age-matched APP/PS1 mice or non-AD models (e.g., α-synucleinopathy models) would strengthen conclusions about AD specificity. This dissociation between intact somata and compromised synaptic integrity suggests that spatial memory deficits arise primarily from functional rather than structural neurodegeneration in MM circuits.

The MM is involved in spatial memory that is mediated through theta-rhythmic interactions with hippocampal formation. Hippocampal CA1 inputs drive MM theta oscillations that facilitate memory consolidation via temporal coding of neuronal ensembles and spike-timing-dependent synaptic plasticity [35, 36]. Previous clinical studies have found that the MM-ATN axis is critical for human episodic memory, with mammillothalamic tract integrity predicting spatial recall performance [37]. Rodent lesion experiments demonstrate that MM inactivation impairs spatial navigation across multiple paradigms, including spontaneous T-maze, and the eight-armed maze [38,39,40,41]. These studies all point to a possible role of the MM in spatial memory. In this study, we observed that the MM neurons are responsive to the object-location memory retrieval phase in C57BL/6J mice, as determined by c-Fos mapping. Furthermore, fiber photometry revealed that MM neurons responded more strongly to the unmoved object than to the displaced object during the object-location memory retrieval phase. In contrast, optogenetic inhibition of these neurons significantly decreased the retrieval of object-location memory in mice, indicating that the MM plays a crucial role in the retrieval of spatial memory. However, calcium signaling in MM neurons showed no significant differences when 5xFAD mice explored different object locations, and optogenetic activation of MM neurons could rescue the deficit in object-location memory retrieval. Our fiber photometry data suggest MM neurons encode object-location novelty. Global optogenetic effects may disrupt this signal, impairing discrimination. While not context-specific, the directional optogenetic effects (activation → impaired retrieval; inhibition → enhanced retrieval) align with fiber photometry inhibition during displaced object investigation. This implies that MM activity suppression is required for normal displaced-object recognition. We acknowledge that global manipulations cannot fully resolve if MM neurons drive behavior via: (a) Direct encoding of object-location context, or (b) Generalized modulation of memory retrieval. Future studies using projection-specific or context-specific optogenetics will clarify this. Taken together, these results reveal how MM neurons respond to different object locations and provide strong support for the importance of MM dysfunction in spatial memory deficits in the AD model.

The MM integrates afferent information from the hippocampus and transmits it to downstream brain regions. Structurally, it receives projections from the dorsal and ventral hippocampus, medial entorhinal cortex, and septal nuclei, and then sends out axons to form the mammillothalamic tract to the ATN, which is interconnection with ventral tegmental nuclei of Gudden [25]. In this study, we explored the structural connections of the MM by viral tracing and found that the projections of MM neurons to the AV and AM were ipsilateral. Further retrograde tracing revealed that different subgroups of MM neurons projected to the AV and AM, with AV-projecting MM neurons concentrated in the anterior-medial portion of the MM, and AM-projecting MM neurons primarily located posteriorly in the posterior-lateral portion of the MM. Whether the projections from MM to different subregions of the ATN contribute to spatial memory independently or in collaboration with other MM output pathways is also worthy of future investigation. Previous research has reported that MM neurons are primarily excitatory but include different molecular phenotypes. Specifically, neurotensin-positive (Nts+) neurons are mainly found in the medial section of the MM, while calbindin-1-positive (Calb1+) neurons reside in the lateral area of the MM. These neurons, characterized by different molecular markers, project to various downstream brain regions [42]. However, we still do not know which specific molecular markers are expressed by these neurons or which downstream brain regions are involved in spatial memory retrieval. The intricate mechanisms underlying this process of each neuron type in the MM warrant further investigation to enhance our exploration of how processes information.

Data availability

All the data that support the findings of this study are provided in the article and its supplementary information files and source data. Source data are provided with this paper. Additional information about this paper (i.g., live imaging data, including behavioral videos and Optical Fiber-Based Ca2+ Recording) are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Palop JJ, Mucke L. Amyloid-beta-induced neuronal dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: from synapses toward neural networks. Nat. Neurosci. 2010;13:812–8.

Canter RG, Penney J, Tsai LH. The road to restoring neural circuits for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2016;539:187–96.

Busche MA, Hyman BT. Synergy between amyloid-β and tau in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2020;23:1183–93.

Harris SS, Wolf F, De Strooper B, Busche MA. Tipping the scales: peptide-dependent dysregulation of neural circuit dynamics in alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2020;107:417–35.

Santín LJ, Rubio S, Begega A, Arias JL. Effects of mammillary body lesions on spatial reference and working memory tasks. Behav Brain Res. 1999;102:137–50.

Nelson AJD, Vann SD. Mammilliothalamic tract lesions disrupt tests of visuo-spatial memory. Behav. Neurosci. 2014;128:494–503.

Dillingham CM, Milczarek MM, Perry JC, Frost BE, Parker GD, Assaf Y, et al. Mammillothalamic disconnection alters hippocampocortical oscillatory activity and microstructure: implications for diencephalic amnesia. J. Neurosci. 2019;39:6696.

Gutiérrez-Guzmán BE, Hernández-Pérez JJ, Olvera-Cortés ME. Serotonergic modulation of septo-hippocampal and septo-mammillary theta activity during spatial learning, in the rat. Behav Brain Res. 2017;319:73–86.

Vann SD, Aggleton JP. The mammillary bodies: two memory systems in one? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;5:35–44.

Kitanishi T, Umaba R, Mizuseki K. Robust information routing by dorsal subiculum neurons. Sci. Adv. 2021;7:eabf1913.

Dillingham CM, Milczarek MM, Perry JC, Vann SD. Time to put the mammillothalamic pathway into context. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021;121:60–74.

Vann SD. Dismantling the Papez circuit for memory in rats. eLife. 2013;2:e00736.

Vann SD, Erichsen JT, O’Mara SM, Aggleton JP. Selective disconnection of the hippocampal formation projections to the mammillary bodies produces only mild deficits on spatial memory tasks: implications for fornix function. Hippocampus. 2011;21:945–57.

Tsivilis D, Vann SD, Denby C, Roberts N, Mayes AR, Montaldi D, et al. A disproportionate role for the fornix and mammillary bodies in recall versus recognition memory. Nat. Neurosci. 2008;11:834–42.

Thierry M, Boluda S, Delatour B, Marty S, Seilhean D, Letournel F, et al. Human subiculo-fornico-mamillary system in Alzheimer’s disease: tau seeding by the pillar of the fornix. Acta Neuropathol. 2020;139:443–61.

Baloyannis SJ, Mavroudis I, Baloyannis IS, Costa VG. Mammillary bodies in Alzheimer’s disease: a Golgi and electron microscope study. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Demen. 2015;31:247–56.

Gail Canter R, Huang W-C, Choi H, Wang J, Ashley Watson L, Yao CG, et al. 3D mapping reveals network-specific amyloid progression and subcortical susceptibility in mice. Commun. Biol. 2019;2:360.

Zhang J, Long B, Li A, Sun Q, Tian J, Luo T, et al. Whole-brain three-dimensional profiling reveals brain region specific axon vulnerability in 5xFAD mouse model. Front. Neuroanat. 2020;14:1–14.

Zhang C, Zhu H, Ni Z, Xin Q, Zhou T, Wu R, et al. Dynamics of a disinhibitory prefrontal microcircuit in controlling social competition. Neuron. 2022;110:516–31.e6.

Li Y, Bao H, Luo Y, Yoan C, Sullivan HA, Quintanilla L, et al. Supramammillary nucleus synchronizes with dentate gyrus to regulate spatial memory retrieval through glutamate release. eLife. 2020;9:e53129.

Guenthner CJ, Miyamichi K, Yang HH, Heller HC, Luo L. Permanent genetic access to transiently active neurons via TRAP: targeted recombination in active populations. Neuron. 2013;78:773–84.

Zhang J, Yao M, Jiang T, Li A, Gong H, He M, et al. A dorsal subiculum-medial mammillary body pathway for spatial memory. Mol. Psychiatry. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-025-03087-w.

Long B, Li X, Zhang J, Chen S, Li W, Zhong Q, et al. Three-dimensional quantitative analysis of amyloid plaques in the whole brain with high voxel resolution. Sci. Sin. Vitae. 2019;49:140.

Guskjolen A, Cembrowski MS. Engram neurons: encoding, consolidation, retrieval, and forgetting of memory. Mol. Psychiatry. 2023;28:3207–19.

Dillingham CM, Frizzati A, Nelson AJD, Vann SD. How do mammillary body inputs contribute to anterior thalamic function? Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2015;54:108–19.

Denninger JK, Smith BM, Kirby ED. Novel object recognition and object location behavioral testing in mice on a budget. JoVE. 2018. https://doi.org/10.3791/58593.

Refaeli R, Kreisel T, Groysman M, Adamsky A, Goshen I. Engram stability and maturation during systems consolidation underlies remote memory. Curr. Biol. 2023;33:3942–3950.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2023.07.042.

Oakley H, Cole SL, Logan S, Maus E, Shao P, Craft J, et al. Intraneuronal beta-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations: potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:10129–40.

Jawhar S, Trawicka A, Jenneckens C, Bayer TA, Wirths O. Motor deficits, neuron loss, and reduced anxiety coinciding with axonal degeneration and intraneuronal Aβ aggregation in the 5XFAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2012;33:196.e29–40.

Yan H, Pang P, Chen W, Zhu H, Henok KA, Li H, et al. The lesion analysis of cholinergic neurons in 5XFAD mouse model in the three-dimensional level of whole brain. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018;55:4126.

Babcock KR, Page JS, Fallon JR, Webb AE. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Stem Cell Rep. 2021;16:681–93.

Pettit NL, Yap E-L, Greenberg ME, Harvey CD. Fos ensembles encode and shape stable spatial maps in the hippocampus. Nature. 2022;609:327–34.

De Vos KJ, Grierson AJ, Ackerley S, Miller CC. Role of axonal transport in neurodegenerative diseases. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2008;31:151–73.

He Z, Guo JL, McBride JD, Narasimhan S, Kim H, Changolkar L, et al. Amyloid-β plaques enhance Alzheimer’s brain tau-seeded pathologies by facilitating neuritic plaque tau aggregation. Nat. Med. 2018;24:29–38.

Bland BH, Konopacki J, Kirk IJ, Oddie SD, Dickson CT. Discharge patterns of hippocampal theta-related cells in the caudal diencephalon of the urethan-anesthetized rat. J. Neurophysiol. 1995;74:322–33.

Buzsáki G. Theta oscillations in the hippocampus. Neuron. 2002;33:325–40.

Kril JJ, Harper CG. Neuroanatomy and neuropathology associated with Korsakoff’s syndrome. Neuropsychol Rev. 2012;22:72–80.

Tsanov M, Vann SD, Erichsen JT, Wright N, Aggleton JP, O’Mara SM. Differential regulation of synaptic plasticity of the hippocampal and the hypothalamic inputs to the anterior thalamus. Hippocampus. 2011;21:1–8.

Aggleton JP, O’Mara SM, Vann SD, Wright NF, Tsanov M, Erichsen JT. Hippocampal–anterior thalamic pathways for memory: uncovering a network of direct and indirect actions. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2010;31:2292–307.

Aggleton JP, Poirier GL, Aggleton HS, Vann SD, Pearce JM. Lesions of the fornix and anterior thalamic nuclei dissociate different aspects of hippocampal-dependent spatial learning: implications for the neural basis of scene learning. Behav. Neurosci. 2009;123:504–19.

Aggleton JP, Vann SD, Saunders RC. Projections from the hippocampal region to the mammillary bodies in macaque monkeys. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2005;22:2519–30.

Mickelsen LE, Flynn WF, Springer K, Wilson L, Beltrami EJ, Bolisetty M, et al. Cellular taxonomy and spatial organization of the murine ventral posterior hypothalamus. eLife. 2020;9:e58901.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by STI2030-Major Projects (Nos. 2021ZD0202400), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 32400850), Hainan Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 822QN298), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Nos. 2022M710989) and Hainan Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Nos. 2022-32).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JZ, DH and YL conceived and designed the study. DH performed most of the experiments. JW, YY, JY, YH, YL, PL, MY, XS and XT provided support with analysis of the data. JZ and PZ wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

We testify that this study has not been published in whole or in part elsewhere.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of the Animal Care and Use Committee of Chongqing Medical University (IACUC-CQMU-2024-0919). The informed consent was obtained from all participants. There were no identifiable images from human research participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, D., Long, Y., Yang, Y. et al. Impairments of spatial memory retrieval via medial mammillary body dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease model. Transl Psychiatry 15, 353 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03583-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03583-1