Abstract

Clinical case reports have linked isotretinoin to depressive symptoms. As acne incidence peaks in adolescence, we focused on adolescent exposure. However, prior studies on isotretinoin’s effects in adolescents have yielded inconsistent results, and direct mechanistic evidence remains scarce. Here, we analyzed depressive-like behaviors in adolescent mice treated with isotretinoin. Pathological changes in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus of isotretinoin-treated mice were observed. We characterized the metabolic and gene-expression signatures of the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex in isotretinoin-treated mice using RNA sequencing and untargeted metabolomics. The results show that isotretinoin induced depressive- and anxiety-like behaviors and caused significant pathological changes in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. In the prefrontal cortex, two differentially expressed genes (Nmb and Pmch) within the neuroactive ligand–receptor interaction pathway correlated positively with depressive-like behaviors; in the hippocampus, two genes (Pomc and Gh) within the same pathway correlated with anxiety-like behaviors. Six differential metabolites associated with the neuroactive ligand–receptor interaction pathway — Adenosine (hippocampus); Tyramine, Taurine, N-acetylaspartylglutamic Acid (NAAG), and ADP (prefrontal cortex); and Taurine (serum) — were associated with depressive-like behaviors. Taurine in the prefrontal cortex was also associated with anxiety-like behaviors. Finally, we reanalyzed metabolomics data from depressed patients to determine whether plasma Taurine levels are elevated. Our findings clarified the biological mechanisms underlying isotretinoin-induced depression and highlighted the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway, especially four genes (Nmb and Pmch in the prefrontal cortex; Pomc and Gh in the hippocampus) and one metabolite (Taurine in the prefrontal cortex) as potential targets for mitigating isotretinoin-induced depression and anxiety.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Depression is one of the most prevalent serious mental disorders, characterized by anhedonia and behavioral despair [1, 2]. It has been reported to be one of the leading causes of global mental health-related disease burden [3]. Meanwhile, depression and anxiety frequently co-occur, and treating patients with comorbid conditions presents greater difficulties and challenges [4, 5]. Although the neurobiological mechanisms are not fully understood in either primary or secondary depression, our previous studies have revealed that neuroinflammation, autophagy [6], gut-brain axis disorder [7, 8], D-ribose [9], and dyslipidemia [9, 10] were involved in the onset of depression. In contrast to primary depression, secondary depression can be caused by several specific reasons, such as medications [11]. Treatment with the anti-acne drug isotretinoin ranks fourth in the top five medicines with the most frequent reports of depression [12]. Due to the concurrence of peak acne onset and ongoing emotional development during adolescence, adolescent mice were chosen as the subjects for this investigation.

Isotretinoin is one of the retinoic acid (RA) isoforms, which belongs to the active metabolite of vitamin A [13]. As a fat-soluble compound, isotretinoin can cross the blood-brain barrier easily and act in the brain tissue wherever intracellular retinoid receptors are present [14]. Isotretinoin has different effects on limbic brain structures, and retinoids modulate a wide spectrum of gene expression in these regions and thereby interfere with the function of many dopaminergic, serotonergic, and noradrenergic neurons involved in the regulation of mood and emotion [15]. Moreover, isotretinoin and its parent compound, vitamin A, have been associated with severe depression and even suicide [16, 17]. RA can also induce hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and behavioral changes, especially depressive-like behavior in rodents, and the selective antagonist of RA receptor α has been considered a potential novel strategy for the treatment of depression [18]. Furthermore, RA plays an important role in both the developing brain and adult brain, especially synaptic plasticity, neurite outgrowth, and neurogenesis [19]. However, whether depressive syndrome is a side effect is currently the subject of considerable controversy. Misery et al. [20] suggested that isotretinoin treatment did not increase the depression risk. In addition, the physiopathological mechanisms are still poorly understood.

The hippocampus is a crucial brain region of the limbic system, and it has a critical role in mood regulation [21,22,23]. Previous studies have revealed changes in the hippocampus in patients with depressive or anxiety disorders [24, 25]. Similarly, the prefrontal cortex is another depression-related brain area that is important for mood regulation [26,27,28]. Abnormalities in hippocampus-prefrontal cortex connectivity also exist in depression [29]. Considering the critical roles of the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex in emotional regulation, investigating the impact of RA on these important brain regions is of significant importance. Moreover, the integration of metabolomics and transcriptomics is an innovative way of determining phenotype-related gene functions and metabolic pathways based on a series of gene actions and their final products, metabolites [30, 31]. To our knowledge, no study has been carried out on the use of metabolomics and transcriptomics to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of RA-induced mental disorder in the mouse hippocampus and prefrontal cortex.

In this study, we first examined the effects of isotretinoin on depressive- and anxiety-like behaviors. The pathological changes in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex were evaluated using hematoxylin and eosin staining and Nissl staining. Then, to investigate the underlying mechanism of isotretinoin-induced depression disorder, untargeted metabolomics was used to analyze metabolic changes in the central (hippocampus and prefrontal cortex) and peripheral (serum). Transcriptomics was used to capture the functions of the altered genes in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. Moreover, by integrating metabolomics and transcriptomics data with mice behaviors, we sought to identify molecular correlates of isotretinoin-induced depressive- and anxiety-like behaviors and to explore potential hippocampus–prefrontal cortex interactions. Finally, we reanalyzed the metabonomics data from our earlier study to clarify the change of taurine in the plasma of depressed patients. Our findings suggest that taurine in the prefrontal cortex is a key mediator in mediating depression- and anxiety-like behaviors; modulation of taurine warrants further investigation as a potential therapeutic strategy for isotretinoin-related mood disturbances.

Methods

Animals and treatments

Male C57BL/6 mice (4–6 weeks old) were purchased from Beijing HFK Bioscience Co., Ltd. To model chronic clinical isotretinoin exposure during adolescence, we employed mice within the adolescent age range [32, 33]. Given the documented role of estrogen in modulating depressive-like behaviors in mice [34], only male mice were used in this study. All mice were housed under a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle at a controlled temperature of 21–25 °C, with ad libitum access to food and water. After a 7-day acclimatization period, the mice were randomly divided into an isotretinoin treatment group and a control group. Our dosing protocol was guided by the standard human clinical dosage of isotretinoin [35] and alignment with methodologies established in prior literature [36]. Mice in the experimental group were administered 20 mg/kg of isotretinoin (HY-15127, MedChemExpress, USA) via intraperitoneal injection daily for 4 weeks. Isotretinoin was dissolved in DMSO and mixed with corn oil in a ratio of 1:9. Meanwhile, control group mice received an equivalent volume of the DMSO-corn oil mixture.

Considering the small size of the mice brain tissues, the experiments were conducted in two different batches. The first batch was used for metabolomics studies, while the second batch was used for transcriptomics studies. Upon completion of behavioral tests, mice were euthanized, and their brains were immediately dissected. Three brain tissue samples from each group were selected for histopathological examination. The prefrontal cortex and hippocampus were isolated, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80 °C. Blood samples were collected via orbital puncture and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min at room temperature to separate the serum, which was then stored at -80 °C. The overall experimental design is depicted in Fig. 1A. The U.K. Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986, was followed for all procedures, and the Ethical Committee of Chongqing Medical University gave its approval (No. IACUC-CQMU-2024-0115).

A Experimental flowchart. B Comparison of sucrose preference rates between the two groups after 4 weeks of isotretinoin treatment. C Comparison of immobility times in the forced swimming test (FST) between the two groups. D Comparison of immobility times in the tail suspension test (TST) between the two groups. E–G In the open field test, total distance traveled (E), number of entries into the center zone (F), and time spent in the center zone (G) were assessed. Statistical comparisons were performed using unpaired t-tests (for normally distributed data) or non-parametric Mann-Whitney U tests (for non-normally distributed data). Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 8 per group). HPC hippocampus, PFC prefrontal cortex.

Behavioral experiments

All tests were conducted by two experimenters blinded to the group assignments. Tests were performed between 10:00 and 16:00, with a 24-h interval between each test to prevent interference [6, 7, 37].

Sucrose preference test (SPT)

Mice were adapted to a 1% sucrose solution for 3 days. Then, one bottle of 1% sucrose and one bottle of water were given for two days, with the bottle positions alternated to avoid position preference each day. For sucrose preference, mice were deprived of water for 12 h and given one bottle of water and one bottle of 1% sucrose solution, and sucrose consumption was measured over the next 12 h. The sucrose preference was calculated as sucrose consumption/total liquid intake [1, 38].

Open field test (OFT)

Mice were placed in the center of an open field apparatus (42 × 42 × 42 cm) and video-recorded for 5 min and 30 s, with the first 30 s used for adaptation. The apparatus was cleaned with 75% ethanol after each test, and the Noldus automated tracking system (EthoVision XT, Noldus, Netherlands) was used to analyze the mice’s locomotor activity.

Tail suspension test (TST)

A tape was attached to the mouse’s tail, and the other end was fixed to a horizontal bar, suspending the mouse 30 cm above the ground. The test lasted for 6 min, with the first 2 min used for adaptation. The Noldus automated tracking system was used to analyze the immobility duration of each mouse.

Forced swimming test (FST)

Mice were placed in a cylindrical container filled with water to a depth of 20 cm at 24 ± 1 °C and video-recorded for 6 min. The first 2 min are used for adaptation. After the test, mice were returned to their cages, and the water in the container was changed. The Noldus automated tracking system was used to analyze the immobility duration of each mouse.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0 (Chicago, IL, US) and R studio (version 3.6.0, 2021). Student’s t-test, non-parametric tests, and Spearman’s correlation analysis were used when appropriate in this study. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of mean. p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Multiple testing corrections were conducted using the Benjamini and Hochberg False Discovery method. DESeq2 was used to identify the differential genes (adjusted p-value < 0.05). Orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) was used to check whether there were differential metabolic phenotypes between the two groups, and then we used variable importance in projection (VIP) > 1.0 and adjusted p-value < 0.05 to identify the differential metabolites [39]. Functional analysis of these identified differential genes and metabolites was conducted based on the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database. All data collection and analyses were performed blind to the conditions of the experiments. Sample sizes are defined in the corresponding figure legend.

The Hematoxylin–Eosin (H&E) staining, Nissl staining, untargeted metabolomics analysis, RNA extraction, sequencing analysis, and analysis of the change of taurine in depressed patients were performed as described in detail in the Supplementary Information.

Results

Isotretinoin-induced depression- and anxiety-like behaviors in mice

Sucrose preference was significantly lower in the isotretinoin-treated group than in the control group (t(14) = 2.383, p = 0.032; Fig. 1B). In the FST, the immobility time (IT) of the isotretinoin-treated mice was significantly higher than that of the control group (t(14) = 2.213, p = 0.044; Fig. 1C). However, in the TST, there was no significant difference in IT between the two groups (t(14) = 0.183, p = 0.858; Fig. 1D).

In the OFT, the total distance traveled by the isotretinoin-treated mice was significantly less than that of the control group (Mann–Whitney U = 12, p = 0.038; Fig. 1E), and the number of entries into the center area was lower in the isotretinoin-treated group (U = 14, p = 0.058; Fig. 1F), although there was no significant difference in the time spent in the center area between the two groups (U = 18, p = 0.161; Fig. 1G). Similarly, the behavioral results from the second batch also showed that isotretinoin induced lower sucrose preference and decreased center-area exploration in the OFT. (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Isotretinoin significantly impaired the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex

HE staining analysis (Supplementary Fig. S2A) revealed that isotretinoin induced neuronal pathology in both the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. In the hippocampus, treated mice exhibited increased pyknotic neurons in CA1, cellular vacuolization in CA3, and reduced granule-cell density in the dentate gyrus (DG) relative to controls. In the prefrontal cortex, treated mice showed increased neuronal vacuolization.

Nissl staining (Supplementary Fig. S2B) showed numerous deeply stained structures in the prefrontal cortex of isotretinoin-treated mice, which is consistent with the disintegration of Nissl bodies. Isotretinoin treatment also induced a significant reduction in the number of normal-appearing neurons in the CA1 region, and the cellular structure in the DG region was less densely arranged.

Differential genes in the hippocampus of isotretinoin-treated mice

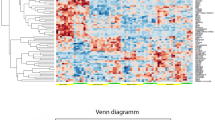

In total, there were 203 differentially expressed genes (n = 107, down-regulated; n = 96, up-regulated) in the hippocampus between the isotretinoin group and control group, and the heat map consisting of these differential genes showed a consistent clustering pattern within the individual groups (Fig. 2A).

A 203 differential genes (n = 96, up-regulated; n = 107, down-regulated) between the two groups were identified. B The results of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway annotation showed that signaling molecules and interaction (KEGG level 2) had the most differential genes. C The results of KEGG enrichment analysis showed that there were six changed pathways (KEGG level 3), and neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction under the signaling molecules and interaction category had six differential genes. D Melanocortin 3 receptor (MC3R), cholinergic receptor nicotinic beta 4 subunit (Chrnb4), pyroglutamylated RFamide peptide receptor like (Qrfprl), pro-opiomelanocortin (Pomc) and growth hormone (Gh) were significantly decreased in the isotretinoin-treated group, and Trhr2 was significantly increased in the isotretinoin-treated group.

To explore the potential functions of these differential genes, we firstly conducted a KEGG pathway annotation analysis, and the results showed that signaling molecules and interaction (KEGG level 2) had the most differential genes (Fig. 2B). Secondly, KEGG enrichment analysis was conducted, and the results showed that there were six changed pathways in the isotretinoin group (KEGG level 3; Fig. 2C). Neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway under signaling molecules and interaction category had five decreased differential genes (Melanocortin 3 receptor (MC3R), Cholinergic Receptor Nicotinic Beta 4 Subunit (Chrnb4), pyroglutamylated RFamide peptide receptor like (Qrfprl), pro-opiomelanocortin (Pomc) and growth hormone (Gh)) and one increased differential gene (thyrotropin releasing hormone receptor 2 (Trhr2) (Fig. 2D). The detailed information of these differential genes was described in Supplementary Table S1.

Differential genes in the prefrontal cortex of isotretinoin-treated mice

We also analyzed the levels of genes in the prefrontal cortex of isotretinoin-fed mice. There were 159 differentially expressed genes (n = 107, down-regulated; n = 52, up-regulated) between the isotretinoin group and the control group (Supplementary Fig. S3A). The heat map consisting of these differential genes also showed a consistent clustering pattern within the individual groups (Supplementary Fig. S3B). The results of KEGG pathway annotation analysis showed that signaling molecules and interaction (KEGG level 2) had the most differential genes, and the results of KEGG enrichment analysis showed that only one changed pathway (neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction) was identified, and there were four decreased differential genes under this pathway: Neuromedin B (Nmb), Pro-Melanin Concentrating Hormone (Pmch), Thyrotropin Releasing Hormone (Trh), and Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Type A Receptor Subunit Rho2 (Gabrr2) (Supplementary Fig. S3C). The detailed information of these differential genes was described in Supplementary Table S2.

Correlations between differential genes and behavioral phenotypes

Spearman correlation analysis was used here to explore the potential correlations between behaviors and differential genes under neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction. As shown in Fig. 3, there were obvious correlations among the different types of behaviors. Percentage of sucrose preference (SP%; represented anhedonia) and IT (represented despair) were the two important types of depressive-like behaviors. Here, we found that two differential genes in the prefrontal cortex were positively correlated with SP% (Nmb, r = 0.786, p = 0.029; Pmch, r = 0.738, p = 0.036). Pmch was negatively correlated with immobility time (r = −0.810, p = 0.015) (Fig. 3).

Moreover, in the OFT, central distance (CD), central time (CT), entry times (ET), and latency period (LP) were four important indexes used to assess anxiety-like behaviors. We found that two differential genes in the hippocampus were positively correlated with CD (Pomc, r = 0.786; p = 0.021; Gh, r = 0.756, p = 0.030), CT (Pomc, r = 0.833; p = 0.010; Gh, r = 0.756, p = 0.030), ET (Pomc, r = 0.905; p = 0.002; Gh, r = 0.805, p = 0.015), and negatively correlated with LP (Pomc, r = −0.904; p = 0.002; Gh, r = −0.805, p = 0.029).

Differential metabolites in the hippocampus of isotretinoin-treated mice

The built OPLS model showed that mice in the isotretinoin-treated group were obviously separated from mice in the control group with no overlap, suggesting a divergent metabolic phenotype in the hippocampus between the isotretinoin-treated group and control group (Fig. 4A). According to VIP and p-value, there were 48 differential metabolites (n = 22, up-regulated; n = 26, down-regulated) responsible for separating the two groups (Fig. 4B). The heat map consisting of these differential metabolites showed a consistent clustering pattern within the individual groups (Fig. 4C). The detailed information of these differential metabolites was described in Supplementary Table S3.

A Orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis model was built using metabolites in the hippocampus, and the results indicated that the metabolic phenotype in the hippocampus was different between the two groups. B Volcano plot of differential metabolites according to variable importance in projection (VIP) and p-value. C Heat map consisting of these differential metabolites. D Significantly changed pathways that these differential metabolites were involved in.

The results of KEGG enrichment analysis using these differential metabolites showed that there were 24 significantly changed pathways in the isotretinoin-treated group, including neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction (Fig. 4D). Specifically, among these identified differential metabolites, adenosine (p = 0.006, up-regulated in the isotretinoin-treated group) and N-Arachidonoyl Dopamine (p = 0.048, up-regulated in the isotretinoin-treated group) belonged to the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway.

Differential metabolites in the prefrontal cortex and serum of isotretinoin-treated mice

We also explored the metabolic phenotypes in both the prefrontal cortex and serum between the two groups. Firstly, the results of OPLS model built with metabolites in the prefrontal cortex showed that the metabolic phenotype was different between the isotretinoin-treated group and the control group (Fig. 5A). The 159 differential metabolites were identified, and the detailed information of these differential metabolites was described in Supplementary Table S4. KEGG enrichment analysis using these differential metabolites showed that there were 33 significantly changed pathways in the isotretinoin group, including neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction (Fig. 5B). Secondly, we found that the metabolic phenotype in serum was also different between the isotretinoin-treated group and control group (Fig. 5C). The 150 differential metabolites were identified, and the detailed information of these differential metabolites was described in Supplementary Table S5.

A Orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis model built with metabolites in the prefrontal cortex indicated a differential metabolic phenotype between the two groups. B Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis showed that the identified 159 differential metabolites were significantly involved in 33 pathways. C Orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis model built with metabolites in serum indicated a differential metabolic phenotype between the two groups. D KEGG enrichment analysis showed that the identified 150 differential metabolites were significantly involved in 24 pathways. Seven differential metabolites under the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway were identified (n = 4, prefrontal cortex; n = 3, serum).

KEGG enrichment analysis using these differential metabolites showed that there were 24 significantly changed pathways in the isotretinoin-treated group, including neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction (Fig. 5D). Meanwhile, we found that four differential metabolites (Tyramine, Taurine, N-Acetylaspartylglutamic Acid (NAA), Adenosine Diphosphate (ADP) in the prefrontal cortex and three differential metabolites (Histamine, Taurine, Aspartic Acid) in serum belonged to the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway (Fig. 5E).

Correlations between differential metabolites and behavioral phenotypes

According to the abovementioned results, there were nine differential metabolites under neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction. To explore the potential correlations between behavioral phenotypes and these nine differential metabolites, Spearman correlation analysis was used. The results (Fig. 6A) showed that SP% had significant relationships with six differential metabolites: Adenosine in the hippocampus (r = −0.846, p = 0.001); Tyramine (r = 0.685, p = 0.014), Taurine (r = −0.755, p = 0.005), NAA (r = 0.601, p = 0.039), and ADP (r = −0.601, p = 0.039) in the prefrontal cortex; and Taurine (r = −0.615, p = 0.033) in serum. Taurine in the prefrontal cortex was also found to be significantly correlated with CT (r = 0.636, p = 0.026). No significant correlations between other types of behaviors and these nine differential metabolites were observed.

A The percentage of sucrose preference (SP%) had significant relationships with six differential metabolites under the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway. B Taurine in the prefrontal cortex had close relationships with the other five differential metabolites (Adenosine, Tyramine, N-Acetylaspartylglutamic Acid, Adenosine Diphosphate (ADP) in the prefrontal cortex; and Taurine in serum) significantly related to SP% and was also significantly related to histamine in serum. C The relative abundance of taurine in MDD patients (n = 56) compared to healthy controls (n = 35). D The relative abundance of taurine in MDD-suicide attempters (n = 21), MDD-non attempters (n = 35), and healthy controls (n = 35). Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Meanwhile, Taurine in the prefrontal cortex was significantly correlated with five other differential metabolites significantly related to SP%: Adenosine (r = 0.846, p = 0.0005) in the hippocampus; Tyramine (r = −0.783, p = 0.003), NAA (r = −0.783, p = 0.003), and ADP (r = 0.650, p = 0.022) in the prefrontal cortex; and Taurine (r = 0.678, p = 0.015) in serum (Fig. 6B). Taurine in the prefrontal cortex was also significantly correlated with Histamine (r = −0.713, p = 0.009) in serum (Fig. 6B). Moreover, we investigated taurine levels in the plasma of patients with depression. The relative abundance of taurine was significantly increased in the plasma of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) (p < 0.0001) compared to healthy controls (Fig. 6C). When subdividing MDD patients into those with and without suicide attempts, taurine levels were significantly higher in both groups compared to healthy controls, with an increase in suicide attempters (p < 0.01) and non-attempters (p < 0.0001; Fig. 6D). Though there was no significant difference between suicide attempters and non-attempters. These results suggested that the increase of Taurine might have an important role in the onset of isotretinoin-induced depressive- and anxiety-like behaviors.

Discussion

In this study, we explored the effects of isotretinoin on emotion and investigated the underlying mechanism, mainly focusing on the role of genes and metabolites in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus. We found that isotretinoin treatment mainly produced depressive-like behavioral changes in mice, evidenced by a decreased sucrose preference and an increased immobility time in the forced-swim test (FST). Interestingly, we also observed anxiety-like behavior in the open-field test, reflected by fewer entries into the center area. Histological staining revealed pathological changes in neurons in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus of isotretinoin-treated mice. Moreover, the integration of central and peripheral metabolomics and transcriptomics analyses identified the enrichment of differential genes and metabolites in the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway. Furthermore, under the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway, two genes (Nmb and Pmch) in the prefrontal cortex were positively associated with depressive-like behaviors, and two genes (Pomc and Gh) in the hippocampus were positively correlated with anxiety-like behaviors. Meanwhile, six metabolites (Adenosine in hippocampus; Tyramine, Taurine, NAA, ADP in prefrontal cortex; Taurine in serum) were significantly correlated with depressive-like behaviors, and Taurine in prefrontal cortex was also significantly associated with anxiety-like behaviors. Finally, we further clarified that the Taurine level was significantly increased in the depressed patients.

Similar to our results, previous research also showed isotretinoin-induced depression-like behavior in mice, though anxiety-like behavior did not show significant changes [40, 41]. However, an earlier study found that isotretinoin did not induce depression-like behavior in rats [42]. These discrepancies might be attributed to differences in strains, age of test subjects, administration methods (gavage or intraperitoneal injection), dosage, duration, and behavioral detection methods. Studies have shown that the strain and age of animals are associated with their baseline depression-like and anxiety-like behaviors [43, 44]. Previous studies used adolescent (4–6 weeks old) C57 mice [41], adult (4 weeks old) DBA/2 J mice [40], and adult (postnatal 82 days) SD rats [42], while here we used adolescent (6 weeks old) C57 mice. Thus, differences in strain and age at drug exposure may lead to variations in experimental results. Moreover, the route of administration is also a potential influencing factor. When administered orally, gut microbiota may affect the metabolism of the drug, whereas intraperitoneal administration can bypass this influence [45]. Future research should further explore the effects of age, strain, route of administration, as well as timing and dosage on the action of isotretinoin. Furthermore, isotretinoin treatment in our study significantly increased immobility time in the FST, although no significant change was observed in the TST. This differential effect suggests that isotretinoin may act selectively on specific pharmacological pathways [46] and patterns of brain-region activation [47, 48], thereby resulting in distinct behavioral responses across testing paradigms.

The hippocampus and prefrontal cortex are two key brain regions associated with emotion processing. Neuronal loss has been observed in both the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus of patients with depression [49, 50], and anxiety is closely linked to neuronal activity in these areas [51]. Here, cytoplasmic vacuoles were observed in both the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus of the isotretinoin-treated mice, along with loose arrangement of the dentate gyrus and dense purple chromatin in the prefrontal cortex and CA1. Neuronal death can occur through apoptosis, necrosis, autophagy, and pyroptosis [52]. A previous study has reported that isotretinoin induces apoptosis in neural crest cells, leading to developmental abnormalities [53]. The pathological changes in apoptosis are characterized by cells forming round or oval clumps with dark eosinophilic cytoplasm and dense purple nuclear chromatin fragments [54]. In contrast, necrotic cells exhibit major morphological changes such as cell swelling, cytoplasmic vacuolization, and ribosome disintegration and dissociation [54]. It is noteworthy that isotretinoin does not specifically affect a single brain region. Instead, it induces neuronal death in both the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus simultaneously. Overall, our finding suggests that isotretinoin induces neuronal apoptosis or necrosis in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, which may lead to the occurrence of depression and anxiety.

Transcriptomic analysis identified the differentially expressed genes in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex were enriched in neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathways. Neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathways comprise a collection of receptors and ligands on the plasma membrane that are associated with intracellular and extracellular signaling pathways [55]. It has been reported that genes related to major depressive disorder are significantly enriched in the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathways [56, 57]. Among these significantly altered genes under the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway, we found Nmb and Pmch in the prefrontal cortex were positively correlated with depressive-like behaviors. Nmb and Pmch are known to influence central nervous system functions and are implicated in the regulation of mood. Nmb, through its receptor NmbR, has been shown to modulate depression-like behaviors, as evidenced by reduced immobility time in depressive mice upon Nmb injection into the mPFC [58]. In addition, Nmb can regulate cell apoptosis. Studies have shown that lower concentrations of Nmb can reduce apoptosis in Leydig cells [59, 60]. Meanwhile, the Pmch gene encodes a precursor protein that is processed into multiple products, including melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH), neuropeptide-glutamic acid-isoleucine, and neuropeptide-glycine-glutamic acid. Similarly, Pmch-derived MCH regulates arousal and energy balance, and its downregulation in severely depressed patients suggests a role in depression [61].

We also identified that Pomc and Gh in the hippocampus were positively related to anxiety-like behaviors. Pomc is a precursor for adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), melanocyte-stimulating hormones, and endorphins, collectively known as melanocortins [62]. Pomc and Gh are more closely associated with the body’s stress response and growth regulation, which are critical in anxiety behaviors. In addition, ACTH, as a component of melanocortins, affects anxiety-like activity in rats [63]. Gh’s role in regulating growth and development is also linked to anxiety. This is particularly evident in adolescents, where dysfunction in Gh secretion is associated with both anxiety and depressive symptoms [64, 65]. Simultaneously, Gh also exhibits neuroprotective effects. During brain hypoxia, GH can protect neurons from damage and prevent neuronal apoptosis [66]. Our results suggest that isotretinoin may mediate depression-like behaviors by downregulating Nmb and Pmch, while anxiety-like behaviors may be mediated by the regulation of Pomc and Gh expression in the hippocampus. These results highlight the potential for distinguishing the roles of these genes in depression and anxiety.

Moreover, metabolomics analysis also revealed that the differential metabolites in the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, and serum were enriched in the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway. Among these significant altered metabolites under the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway, we found six metabolites (Adenosine in hippocampus; Tyramine, Taurine, NAA, ADP in the prefrontal cortex; Taurine in serum) were significantly correlated with depressive behaviors, and Taurine in the prefrontal cortex was also significantly correlated with anxiety-like behaviors. Additionally, our previous metabolomic data confirmed that taurine levels were significantly elevated in the plasma of depressed patients. The results suggested that high levels of Taurine were correlated with depression.

Adenosine and ADP are metabolites in the purinergic signaling system, playing crucial roles in energy transfer. Changes in hippocampal adenosine and the prefrontal cortex suggest that isotretinoin may alter purinergic system transmission, inducing depression [67]. Moreover, genetic deletion of adenosine deaminase—an enzyme responsible for adenosine breakdown—has been found to induce anxiety-like behavior in mice [68]. Additionally, elevated expression of adenosine A1 receptors and the synaptic protein Homer1a in the hippocampus is associated with reduced resilience to chronic stress and increased depression-like behaviors [69]. Mechanistically, overactivation of inhibitory adenosine A1 receptors can suppress neurotransmitter release and disrupt synaptic transmission, thereby negatively affecting mood regulation [70]. Collectively, these findings imply that dysregulation of the adenosine system may underlie the emotional disturbances associated with isotretinoin treatment. Meanwhile, Tyramine and NAA are metabolites related to neurotransmitter systems. Tyramine increases the release of norepinephrine, while NAA activates presynaptic mGluR3 receptors to inhibit glutamate release [71]. Studies have shown that changes in tyramine and NAA are also observed in patients with depression [72, 73]. Taurine has been found to be involved in alleviating depressive and anxiety-like symptoms that may be related to inflammation, dendritic changes, brain-derived neurotrophic factor depletion, and anti-apoptotic [74,75,76,77]. Magnetic resonance studies in depression models found increased taurine levels in the hippocampus and frontal lobe, suggesting a compensatory neuroprotective response [78]. Taurine is also considered a potential target for treating depression and anxiety [79]. Here, taurine levels were elevated in the prefrontal cortex and serum of the isotretinoin-treated mice, which correlated with anxiety and depression-like behaviors. These findings suggest that isotretinoin may induce compensatory taurine increases, exerting neuroprotective effects and mediating anxiety and depression-like behaviors.

Our study has several limitations. First, due to mice brain sample size limitation, the samples used for transcriptome sequencing and metabolome sequencing were not from the same batch; thus, we did not perform integrated analysis of genes and metabolites to explore their correlation. Being aware of this limitation, we have taken a series of measures to minimize its impact, including using a uniform data analysis process and considering the potential impact of the sample source. Future research may attempt to use samples from the same source for transcriptome and metabolome sequencing to obtain more consistent and comparable results and further explore the relationship between genes and metabolites. Second, we primarily focused on the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus in our study. Other emotion-related brain regions, such as the amygdala and nucleus accumbens, were not examined. Further research is needed to explore these areas. Third, due to the limitations of technologies and funds, we did not conduct further experiments to validate the functional relationship of interaction with the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway, especially the four genes and one metabolite that we have found. Fourth, to eliminate the potential confounding effects of estrogen on mood-related behaviors, only male mice were employed in this study. However, given the higher prevalence of depression in females [80], future studies should further examine the influence of sex on isotretinoin-induced depressive behaviors. Fifth, although the OFT was used to assess anxiety-like behavior—and previous study has indeed validated its relevance—relying on a single behavioral assay is insufficient to fully capture the anxiety phenotype. To strengthen and complement our findings, additional well-established anxiety tests, such as the elevated plus maze and the light–dark box, will be incorporated in future work. Sixth, while antidepressants like sertraline have been demonstrated to alleviate isotretinoin-induced depressive symptoms [81, 82], the present study focused solely on measuring plasma taurine levels in patients with MDD. Due to limitations in resources, we did not conduct supplementary animal experiments. Subsequent research should evaluate the therapeutic potential of conventional antidepressants in this model and elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to reveal the underlying mechanism of isotretinoin-induced depression and anxiety using transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis. The altered neuroactive receptor pathway, especially four genes (Nmb and Pmch in the prefrontal cortex; Pomc and Gh in the hippocampus) and one metabolite (Taurine in the prefrontal cortex) may contribute to the onset of isotretinoin-induced depression and anxiety. The findings of this study further highlight that isotretinoin could affect emotion and provide potential targets for the development of anti-acne drugs with fewer side effects.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Xu K, He Y, Chen X, Tian Y, Cheng K, Zhang L, et al. Validation of the targeted metabolomic pathway in the hippocampus and comparative analysis with the prefrontal cortex of social defeat model mice. J Neurochem. 2019;149:799–810.

Jia X, Gao Z, Hu H. Microglia in depression: current perspectives. Sci China Life Sci. 2021;64:911–25.

Marwaha S, Palmer E, Suppes T, Cons E, Young AH, Upthegrove R. Novel and emerging treatments for major depression. Lancet. 2023;401:141–53.

Kalin NH. The critical relationship between anxiety and depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177:365–7.

Pan H-Q, Xia T, Zhang Y-Y-N, Zhang H-J, Xu M-J, Guo J, et al. Unveiling the enigma of anxiety disorders and depression: from pathogenesis to treatment. Sci China Life Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11427-025-3024-y (2025).

Xu K, Wang M, Wang H, Zhao S, Tu D, Gong X, et al. HMGB1/STAT3/p65 axis drives microglial activation and autophagy exert a crucial role in chronic stress-induced major depressive disorder. J Adv Res. 2023;59:79–96.

Xu K, Ren Y, Zhao S, Feng J, Wu Q, Gong X, et al. Oral D-ribose causes depressive-like behavior by altering glycerophospholipid metabolism via the gut-brain axis. Commun Biol. 2024;7:69.

Wang J, Xie J, He F, Wu W, Xu K, Ren Y, et al. Akkermansia muciniphila-derived SCFAs improve the depression-like behaviors of mice by inhibiting neuroinflammation. Pharmacol Res. 2025;220:107938.

Xu K, Zhao S, Ren Y, Zhong Q, Feng J, Tu D, et al. Elevated SCN11A concentrations associated with lower serum lipid levels in patients with major depressive disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2024;14:202.

Xu K, Zheng P, Zhao S, Wang M, Tu D, Wei Q, et al. MANF/EWSR1/ANXA6 pathway might as the bridge between hypolipidemia and major depressive disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12:527.

Li NX, Hu YR, Chen WN, Zhang B. Dose effect of psilocybin on primary and secondary depression: a preliminary systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2022;296:26–34.

Ergun T, Seckin D, Ozaydin N, Bakar Ö, Comert A, Atsu N, et al. Isotretinoin has no negative effect on attention, executive function and mood. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:431–9.

Khalil NY, Darwish IA, Al-Qahtani AA. Isotretinoin. Profiles Drug Subst Excip Relat Methodol. 2020;45:119–57.

Borovaya A, Olisova O, Ruzicka T, Sárdy M. Does isotretinoin therapy of acne cure or cause depression?. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1040–52.

Jentsch JD, Roth RH, Taylor JR. Role for dopamine in the behavioral functions of the prefrontal corticostriatal system: implications for mental disorders and psychotropic drug action. Prog Brain Res. 2000;126:433–53.

van der Spek A, Stewart ID, Kühnel B, Pietzner M, Alshehri T, Gauß F, et al. Circulating metabolites modulated by diet are associated with depression. Mol Psychiatry 2023;28:3874–87.

Fernandes T, Magina S. Oral isotretinoin in the treatment of juvenile acne and psychiatric adverse effects - a systematic review. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2023;42:83–90.

Hu P, Liu J, Zhao J, Qi XR, Qi CC, Lucassen PJ, et al. All-trans retinoic acid-induced hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal hyperactivity involves glucocorticoid receptor dysregulation. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3:e336.

Jiang W, Wen EY, Gong M, Shi Y, Chen L, Bi Y, et al. The pattern of retinoic acid receptor expression and subcellular, anatomic and functional area translocation during the postnatal development of the rat cerebral cortex and white matter. Brain Res. 2011;1382:77–87.

Misery L, Feton-Danou N, Consoli A, Chastaing M, Consoli S, Schollhammer M, et al. [Isotretinoin and adolescent depression]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2012;139:118–23.

Wang J, Lu T, Gui Y, Zhang X, Cao X, Li Y, et al. HSPA12A controls cerebral lactate homeostasis to maintain hippocampal neurogenesis and mood stabilization. Transl Psychiatry. 2023;13:280.

Borsini A, Giacobbe J, Mandal G, Boldrini M. Acute and long-term effects of adolescence stress exposure on rodent adult hippocampal neurogenesis, cognition, and behaviour. Mol Psychiatry. 2023;28:4124–37.

Feola B, Beermann A, Manzanarez Felix K, Coleman M, Bouix S, Holt DJ, et al. Data-driven, connectome-wide analysis identifies psychosis-specific brain correlates of fear and anxiety. Mol Psychiatry. 2024;29:2601–10.

Bremner JD, Narayan M, Anderson ER, Staib LH, Miller HL, Charney DS. Hippocampal volume reduction in major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:115–8.

Rusch BD, Abercrombie HC, Oakes TR, Schaefer SM, Davidson RJ. Hippocampal morphometry in depressed patients and control subjects: relations to anxiety symptoms. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50:960–4.

Wang HY, You HL, Song CL, Zhou L, Wang SY, Li XL, et al. Shared and distinct prefrontal cortex alterations of implicit emotion regulation in depression and anxiety: An fNIRS investigation. J Affect Disord. 2024;354:126–35.

Kishi T, Ikuta T, Sakuma K, Hatano M, Matsuda Y, Wilkening J, et al. Theta burst stimulation for depression: a systematic review and network and pairwise meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2024;29:3893–9.

Li L, Ren L, Liu C. Can intermittent theta-burst stimulation of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex relieve executive dysfunction in patients with late-life depression?. Alpha Psychiatry. 2024;25:115–7.

Shu H, Yuan Y, Xie C, Bai F, You J, Li L, et al. Imbalanced hippocampal functional networks associated with remitted geriatric depression and apolipoprotein E ε4 allele in nondemented elderly: a preliminary study. J Affect Disord. 2014;164:5–13.

Zagare A, Preciat G, Nickels SL, Luo X, Monzel AS, Gomez-Giro G, et al. Omics data integration suggests a potential idiopathic Parkinson’s disease signature. Commun Biol. 2023;6:1179.

Spathopoulou A, Sauerwein GA, Marteau V, Podlesnic M, Lindlbauer T, Kipura T, et al. Integrative metabolomics-genomics analysis identifies key networks in a stem cell-based model of schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2024;29:3128–40.

Shearer KD, Stoney PN, Morgan PJ, McCaffery PJ. A vitamin for the brain. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35:733–41.

Bremner JD, Shearer KD, McCaffery PJ. Retinoic acid and affective disorders: the evidence for an association. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:37–50.

Walf AA, Frye CA. A review and update of mechanisms of estrogen in the hippocampus and amygdala for anxiety and depression behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1097–111.

Paichitrojjana A, Paichitrojjana A. Oral isotretinoin and its uses in dermatology: a review. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2023;17:2573–91.

Qin XY, Fang H, Shan QH, Qi CC, Zhou JN. All-trans retinoic acid-induced abnormal hippocampal expression of synaptic genes SynDIG1 and DLG2 is correlated with anxiety or depression-like behavior in mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:2677.

Xu K, Wang M, Zhou W, Pu J, Wang H, Xie P. Chronic D-ribose and D-mannose overload induce depressive/anxiety-like behavior and spatial memory impairment in mice. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:90.

Debler RA, Madison CA, Hillbrick L, Gallegos P, Safe S, Chapkin RS, et al. Selective aryl hydrocarbon receptor modulators can act as antidepressants in obese female mice. J Affect Disord. 2023;333:409–19.

Xu K, Ren Z, Zhao S, Ren Y, Wang J, Wu W, et al. Fecal metabolites as early-phase biomarkers and prediction panel for ischemic stroke. BMC Microbiol. 2025;25:525.

O’Reilly KC, Shumake J, Gonzalez-Lima F, Lane MA, Bailey SJ. Chronic administration of 13-cis-retinoic acid increases depression-related behavior in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1919–27.

Su XH, Li WP, Wang YJ, Liu J, Liu JY, Jiang Y, et al. Chronic administration of 13-cis-retinoic acid induces depression-like behavior by altering the activity of dentate granule cells. Neurotherapeutics. 2022;19:421–33.

Ferguson SA, Cisneros FJ, Gough B, Hanig JP, Berry KJ. Chronic oral treatment with 13-cis-retinoic acid (isotretinoin) or all-trans-retinoic acid does not alter depression-like behaviors in rats. Toxicol Sci. 2005;87:451–9.

Eltokhi A, Kurpiers B, Pitzer C. Baseline depression-like behaviors in wild-type adolescent mice are strain and age but not sex dependent. Front Behav Neurosci. 2021;15:759574.

Shoji H, Takao K, Hattori S, Miyakawa T. Age-related changes in behavior in C57BL/6J mice from young adulthood to middle age. Mol Brain. 2016;9:11.

Hayashi M, Sutou S, Shimada H, Sato S, Sasaki YF, Wakata A. Difference between intraperitoneal and oral gavage application in the micronucleus test. The 3rd collaborative study by CSGMT/JEMS.MMS. Collaborative Study Group for the Micronucleus Test/Mammalian Mutagenesis Study Group of the Environmental Mutagen Society of Japan. Mutat Res. 1989;223:329–44.

Chatterjee M, Jaiswal M, Palit G. Comparative evaluation of forced swim test and tail suspension test as models of negative symptom of schizophrenia in rodents. ISRN Psychiatry. 2012;2012:595141.

Choi SH, Chung S, Cho JH, Cho YH, Kim JW, Kim JM, et al. Changes in c-Fos expression in the forced swimming test: common and distinct modulation in rat brain by desipramine and citalopram. Korean J Physiol Pharm. 2013;17:321–9.

Hiraoka K, Motomura K, Yanagida S, Ohashi A, Ishisaka-Furuno N, Kanba S. Pattern of c-Fos expression induced by tail suspension test in the mouse brain. Heliyon. 2017;3:e00316.

Rajkowska G. Postmortem studies in mood disorders indicate altered numbers of neurons and glial cells. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:766–77.

Lee AL, Ogle WO, Sapolsky RM. Stress and depression: possible links to neuron death in the hippocampus. Bipolar Disord. 2002;4:117–28.

Ghasemi M, Navidhamidi M, Rezaei F, Azizikia A, Mehranfard N. Anxiety and hippocampal neuronal activity: Relationship and potential mechanisms. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2022;22:431–49.

Fricker M, Tolkovsky AM, Borutaite V, Coleman M, Brown GC. Neuronal cell death. Physiol Rev. 2018;98:813–80.

Melnik BC. Apoptosis may explain the pharmacological mode of action and adverse effects of isotretinoin, including teratogenicity. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:173–81.

Elmore S. Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35:495–516.

He Z, Tang F, Lu Z, Huang Y, Lei H, Li Z, et al. Analysis of differentially expressed genes, clinical value and biological pathways in prostate cancer. Am J Transl Res. 2018;10:1444–56.

Fan T, Hu Y, Xin J, Zhao M, Wang J. Analyzing the genes and pathways related to major depressive disorder via a systems biology approach. Brain Behav. 2020;10:e01502.

Liu Y, Fan P, Zhang S, Wang Y, Liu D. Prioritization and comprehensive analysis of genes related to major depressive disorder. Mol Genet Genom Med. 2019;7:e659.

Li S, Luo H, Lou R, Tian C, Miao C, Xia L, et al. Multiregional profiling of the brain transmembrane proteome uncovers novel regulators of depression. Sci Adv. 2021;7:eabf0634.

Ma Z, Zhang Y, Su J, Yang S, Qiao W, Li X, et al. Effects of neuromedin B on steroidogenesis, cell proliferation and apoptosis in porcine Leydig cells. J Mol Endocrinol. 2018;61:13–23.

Ma Z, Guo J, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Zhang M, Zong R, et al. Neuromedin B regulates steroidogenesis, cell viability and apoptosis in rabbit leydig cells. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2020;288:113371.

Al Shweiki MR, Oeckl P, Steinacker P, Barschke P, Dorner-Ciossek C, Hengerer B, et al. Proteomic analysis reveals a biosignature of decreased synaptic protein in cerebrospinal fluid of major depressive disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10:144.

Harno E, Gali Ramamoorthy T, Coll AP, White A. POMC: The physiological power of hormone processing. Physiol Rev. 2018;98:2381–430.

Chaki S, Okuyama S. Involvement of melanocortin-4 receptor in anxiety and depression. Peptides. 2005;26:1952–64.

Akaltun İ, Çayır A, Kara T, Ayaydın H. Is growth hormone deficiency associated with anxiety disorder and depressive symptoms in children and adolescents?: A case-control study. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2018;41:23–27.

Karachaliou F-H, Karavanaki K, Simatou A, Tsintzou E, Skarakis NS, Kanaka-Gatenbein C. Association of growth hormone deficiency (GHD) with anxiety and depression: experimental data and evidence from GHD children and adolescents. Hormones (Athens). 2021;20:679–89.

Arce VM, Devesa P, Devesa J. Role of growth hormone (GH) in the treatment on neural diseases: from neuroprotection to neural repair. Neurosci Res. 2013;76:179–86.

Szopa A, Socała K, Serefko A, Doboszewska U, Wróbel A, Poleszak E, et al. Purinergic transmission in depressive disorders. Pharmacol Ther. 2021;224:107821.

Sauer AV, Hernandez RJ, Fumagalli F, Bianchi V, Poliani PL, Dallatomasina C, et al. Alterations in the brain adenosine metabolism cause behavioral and neurological impairment in ADA-deficient mice and patients. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40136.

Serchov T, Schwarz I, Theiss A, Sun L, Holz A, Döbrössy MD, et al. Enhanced adenosine A1 receptor and Homer1a expression in hippocampus modulates the resilience to stress-induced depression-like behavior. Neuropharmacology. 2020;162:107834.

Gomes JI, Farinha-Ferreira M, Rei N, Gonçalves-Ribeiro J, Ribeiro JA, Sebastião AM, et al. Of adenosine and the blues: the adenosinergic system in the pathophysiology and treatment of major depressive disorder. Pharmacol Res. 2021;163:105363.

Benarroch EE. N-acetylaspartate and N-acetylaspartylglutamate: neurobiology and clinical significance. Neurology. 2008;70:1353–7.

Sandler M, Ruthven CR, Goodwin BL, Reynolds GP, Rao VA, Coppen A. Deficient production of tyramine and octopamine in cases of depression. Nature. 1979;278:357–8.

Reynolds LM, Reynolds GP. Differential regional N-acetylaspartate deficits in postmortem brain in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:54–59.

Wu GF, Ren S, Tang RY, Xu C, Zhou JQ, Lin SM, et al. Antidepressant effect of taurine in chronic unpredictable mild stress-induced depressive rats. Sci Rep. 2017;7:4989.

Jangra A, Rajput P, Dwivedi DK, Lahkar M. Amelioration of repeated restraint stress-induced behavioral deficits and hippocampal anomalies with taurine treatment in mice. Neurochem Res. 2020;45:731–40.

Zhu Y, Wang R, Fan Z, Luo D, Cai G, Li X, et al. Taurine alleviates chronic social defeat stress-induced depression by protecting cortical neurons from dendritic spine loss. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2023;43:827–40.

Kumari N, Prentice H, Wu JY. Taurine and its neuroprotective role. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;775:19–27.

Pavlova I, Ruda-Kucerova J. Brain metabolic derangements examined using 1H MRS and their (in)consistency among different rodent models of depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2023;127:110808.

Jangra A, Gola P, Singh J, Gond P, Ghosh S, Rachamalla M, et al. Emergence of taurine as a therapeutic agent for neurological disorders. Neural Regen Res. 2023;19:62–68.

Stetler C, Miller GE. Depression and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activation: a quantitative summary of four decades of research. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:114–26.

Jacobs DG, Deutsch NL, Brewer M. Suicide, depression, and isotretinoin: Is there a causal link?. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:S168–75.

Ng CH, Tam MM, Hook SJ. Acne, isotretinoin treatment and acute depression. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2001;2:159–61.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFA0505700), Non-profit Central Research Institute Fund of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (2019PT320002), Chongqing Youth Top-Notch Talent Program (YXQN2025031), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81820108015, 82301720), Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing (CSTB2025NSCQ-GPX1127), Qiande Talents Program of the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (2025QDTS-04), and CQMU Program for Youth Innovation in Future Medicine (W0168).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KX, PX, and JC designed the general project. YR, ZR, SZ, WW, and QZ performed behavioral tests. YR, JW, FH, and HZ performed histology experiments. YR, ZR, KX, and JC did the data analysis and interpretation. YR, KX, and JC wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript revision and gave final approval of the version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

All experimental procedures were approved by the Ethical Committee of Chongqing Medical University (Approval No. IACUC-CQMU-2024-0115) and were conducted in accordance with the U.K. Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986, and its guiding principles.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ren, Y., Ren, Z., Zhao, S. et al. Chronic administration of isotretinoin induces depressive- and anxiety-like behaviors by altering the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway in adolescent mice. Transl Psychiatry 16, 28 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03750-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03750-4