Abstract

Background

Modern oral healthcare extensively uses polymer items and devices derived from various monomeric compounds. These materials are essential for personal protective equipment, infection barriers, packaging, and intraoral devices. The COVID-19 pandemic has led to an increased reliance on single-use polymer items, causing supply chain disruptions and higher costs. This systematic review explores the extent of polymer waste and pollution generated in oral healthcare clinics.

Materials and methods

A systematic review protocol was registered with PROSPERO and was formatted according to PRISMA guidelines and SWiM recommendations. Eligibility criteria included studies that provided quantified estimates of polymer waste or pollution in air or wastewater from oral healthcare clinics. Comprehensive electronic searches were conducted across several bibliometric databases, followed by data extraction and risk of bias assessments performed by two independent reviewers.

Results

A total of thirty studies were included in the review. Sixteen papers reported on waste audits that detailed polymer waste data, while eight studies focused on pollution caused by polymer nano- and microparticles in clinical settings. Additionally, six experimental studies investigated potential leakage of monomeric eluates or polymer particles from landfill waste. There was significant variation in the amount of polymer waste generated per patient, ranging from 81 to 384 g per operatory room per day. On-site sampling revealed the presence of polymer nano- and microparticles in the clinic air, which was influenced by dental procedures and the equipment used.

Conclusions

This review highlights critical knowledge gaps about polymer waste and pollution in oral healthcare clinics. The variability of study designs limited the feasibility of meta-analysis. Current evidence indicates substantial polymer waste generation, particularly from single-use items, as well as potential environmental impacts from monomeric eluates and polymer microparticles. Future research should focus on sustainable polymer waste management solutions to reduce environmental pollution in oral healthcare settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Modern oral healthcare relies on a wide range of polymer items and devices (PIDs) composed of monomeric compounds. Some compounds are used in personal protective equipment (PPE), as barriers to prevent cross-infection, and for packaging and wrapping. Other compounds have been explicitly designed to resist degradation in the patient’s mouth. A third category of polymer compounds is elastomers, which are employed as impression materials for creating casts (Supplementary Table 1).

Many devices for intraoral use are customised from monomeric materials in the clinic and polymerise chemically after mixing or following exposure to heat or light. The extent of remaining unreacted monomeric compounds varies depending on the degree of polymerisation. The properties of polymers, which can range from rigid to flexible and durable to fragile, are influenced by the presence of intended or unintended monomeric compounds and other copolymers. In this paper, ‘polymer’ comprises plastic and rubber-like materials, regardless of their content of unreacted monomeric compounds.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of single-use polymer items increased significantly, leading to disrupted supply chains and rising costs [1]. The situation stimulated initiatives to improve the conservation of devices and instruments [2]. There is also a recognition of the importance of managing biomedical waste effectively, particularly hazardous waste containing infectious and potentially infectious materials [3]. Developing innovative solutions is crucial for facilitating the reprocessing and recycling of PIDs and other polymer products for circular use, as well as enhancing the current management of polymer waste from oral healthcare clinics [4].

There is growing recognition in healthcare clinics of the importance of reducing, reusing, and recycling monomeric materials and PIDs [5]. However, identifying the most effective and safe solutions remains challenging due to significant knowledge gaps. These include limited understanding of the potential hazards of nano- and microparticles (NMPs) and chemical additives leaching from medical plastics [6]. There is also insufficient evidence on best practices for segregating biomedical and domestic waste in hospitals and how to manage waste effectively to prevent NMP pollution in air and wastewater systems [7]. On a broader scale, the environmental impacts of monomeric eluates and polymer-derived NMPs in marine ecosystems are not fully understood [8,9,10]. Furthermore, the relative viability and long-term effectiveness of local versus centralised bioremediation strategies for polymer waste remain uncertain [11]. Finally, emerging research suggests potential risks to human health and the environment from persistent organic pollutants released by monomeric compounds [12, 13], including possible epigenomic effects—yet much remains to be explored.

The extent of polymer waste and pollution in oral healthcare clinics has not been systematically reviewed. This systematic review aims to address this knowledge gap by evaluating the existing scientific evidence to answer the research question: ‘How much polymer waste and pollution is generated in oral healthcare clinics?’

Methods

Before beginning the work, we registered a protocol with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO CRD42023472616). The protocol serves as the foundation for this SR, formatted according to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) [14], complemented by the Synthesis Without Meta-analysis (SWiM) recommendations [15].

Eligibility criteria

We searched for studies that reported quantified estimates of polymer waste or pollution in the air or wastewater within oral healthcare clinics. A broad search was adopted since the topic is under-researched, with no limitations regarding variables such as the waste collection year, the timeframe for collecting waste, or the clinic setting, i.e., private or public single or group practices, hospitals, or faculty hospitals. The same applied to studies detailing the levels of monomeric eluate, monomeric degradation compounds, or NMPs associated with the collection, management, and disposal of polymer waste. Eligible studies included waste audits and field-based research reporting polymer pollution in oral healthcare clinics. Additionally, we included laboratory studies experimentally designed to estimate polymer pollution from waste collection, management, and disposal in oral healthcare clinics. Our only exclusion criterion was studies that did not report quantified estimates, regardless of study design, although the reference lists were routinely scrutinised to identify possible eligible studies.

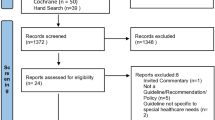

Information sources and search strategy

Two reviewers independently conducted systematic and comprehensive electronic searches to identify potentially eligible records. A Boolean search strategy was developed for searches in Pubmed: (Dentist OR dental health services[mesh] OR Dentistry[mesh]) AND (Polymers[mesh] OR Organic Chemicals[mesh] OR plastic*[tw] OR polymer*[tw] OR Resin*[tw] OR acryl*[tw]) AND ((Medical Waste[MeSH] OR Medical Waste Disposal[MeSH] OR Waste Management[MeSH] OR Waste Disposal Facilities[MeSH] OR Hazardous Waste[MeSH] OR Environmental Pollution[MESH] OR Dental Waste[MESH])). The SRA Polyglot Search Translator was adopted to modify the search strategy to various bibliometric databases and grey literature. Scientific literature was searched on the Cochrane Library, Embase via Ovid, EBSCOhost (restricted to CINAHL, Risk Management Reference Center, GreenFILE, MEDLINE, the eBook Open Access Collection, and AMED [The Allied and Complementary Medicine Database]), the National Library of Medicine (MEDLINE via PubMed), ScienceDirect, and the Web of Science (Supplementary Table 2).

Grey literature was explored through Google Scholar and the Abstracts Database of the International Association for Dental Research (IADR). The ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global database was searched for master’s and doctoral theses. The language was limited to English. The reference lists of the included studies were further screened to identify additional relevant studies. The final search in the bibliometric databases was conducted in March 2025. Records from the literature searches were exported into EndNote, where duplicates were removed before being transferred to a relational database (Microsoft Access) to create a digital entry form for further data extraction from the primary studies.

Selection and data collection process

One investigator (AJ) scrutinised the titles and abstracts of the identified records to ascertain whether the publication contained pollution estimates or polymer waste. Conversely, the second investigator (AMG) ensured that the excluded titles did not meet this criterion. In cases of disagreement, a consensus was reached on which articles to review in full text. The two investigators independently extracted data from eligible studies into an online Microsoft Access database form. The extracted data were compared, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion. After confirming its accuracy, one investigator (AJ) entered the agreed-upon data into Access. The authors of the included studies were not contacted to verify missing data.

Data items

Data were collected regarding the study objectives and methodology, as well as the relevant characteristics of the objects or study participants, interventions, sampling and measurement methods, and the duration of the study. The eligible outcomes and measures were as follows:

-

1.

Polymer waste qualities or quantities: monomeric eluate, NMP count or mass per intervention, patient, or clinic measured daily, weekly, monthly, or according to any other time frame.

-

2.

Polymer pollution qualities or quantities: monomeric eluate, NMP count or mass in the clinic’s ambient air or wastewater.

-

3.

Monomeric eluate or NMP count in waste landfills associated with PIDs from oral healthcare clinics.

Study risk of bias assessment

Exhaustive literature searches did not identify validated tools for addressing the risk of bias in waste audits. Consequently, we developed a checklist that included recommended processes mandated by the Environment Agency in the United Kingdom for the treatment and transfer of healthcare waste [16]. (Supplementary Table 3). Discrepancies between the two investigators’ assessments of bias risk were to be resolved by consensus, involving an evaluation of the risk of bias researcher if necessary.

Effect measures

We planned to analyse the effect size of reported comparative approaches for reducing polymer waste, monomeric eluate, and polymer NMP content in air or wastewater. We intended to compare mean differences alongside estimated confidence intervals for aggregated continuous data. The waste audit data were to be converted into polymer waste mass per patient (g), operatory per day (kg) and operatory per year (kg). The heterogeneity of the study sample was assessed using I² statistics to determine the suitability of conducting a meta-analysis.

Synthesis of outcome results

We aimed to synthesise effect estimates to obtain summary estimates using RevMan v.5.4, if comparable data could be identified in at least five studies with low clinical heterogeneity and statistical heterogeneity, as assessed by I² statistics. Data reported in measurement units that differed from other studies were transformed to facilitate comparisons within each synthesis. If meta-analyses were not feasible, we planned to follow the SWiM guidelines [17, 18]. We did not intend to conduct any analyses to investigate heterogeneity or to perform sensitivity analyses to evaluate the robustness of the synthesised results. Nor did we plan to assess the risk of bias resulting from missing results in a synthesis due to potential reporting biases, or to evaluate the certainty or confidence in the body of evidence for any outcomes.

Certainty assessment

The GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations) framework was to be considered, provided sufficient outcome data could be extracted from the primary studies to undertake meta-analyses.

Results

Study selection

The bibliometric searches yielded numerous duplicates and records unrelated to the topic. After screening and thoroughly reading the full texts to assess eligibility, we identified 30 references for data extraction (Fig. 1).

Sixteen papers described waste audits that included data on polymer waste [5, 19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. Eight studies described polymer NMP pollution in the clinic work area [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. Six experimental laboratory studies reported the potential leakage of monomeric eluates or polymer NMPs from landfill waste [42,43,44,45,46,47].

Polymer waste

Waste generation and management in oral healthcare clinics is a recurring topic in national and international dental and medical journals. However, the number of research papers detailing the qualities and quantities of polymer waste and other waste remains limited. Few waste audits have documented specific amounts and these originate from Iran (n = 6) [21,22,23, 25, 27, 29], Greece (n = 3) [20, 26, 28], United Kingdom (n = 2) [5, 24], the USA (n = 2) [31, 32], and single studies from Australia [33], and Turkey [19]. Relevant supplementary data is a waste audit conducted in a hospital in Australia that identified the most common wasted polymers in surgical operating theatres [30] (Table 1).

Study characteristics

Waste audits conducted between 2002 and 2023 demonstrate various approaches and contexts in which polymer waste is evaluated. Clinical settings include dental faculty clinics (n = 2) [19, 33], dental faculty undergraduate preclinic (n = 1) [32], private clinics (n = 5) [20, 22, 26, 28, 31], public clinics (n = 2) [25, 27], mixed clinics (n = 2) [5, 24], speciality clinics (n = 2) [21, 23, 29], and one surgical operating theatre [30]. Sample sizes differ markedly, with the most significant number of treated patients totalling n = 2542 over 20 days [26, 28]. Some focus on the number of clinics involved. While most publications mention the number of clinics, many fail to specify the number of operatories within each clinic. Only five publications report the number of patients treated during the sampling period [5, 26, 27, 29, 33]. The duration of these studies also differs, ranging from a single-day audit [33], to multi-month observations [29]. The primary data collected from all studies are the masses of polymer waste, although additional details, such as waste per compound, were scarce [30]. Notably, the study by Martin et al. documented 150 observations by auditors over 120 days across three different types of clinics: a teaching hospital, an NHS primary care clinic, and two private primary clinics [5] (Table 2).

Risk of bias

Waste audits are conducted for various reasons, and ethical approval is not always required. Some identified reports cited national regulations, while others underscored the necessity for logistical planning within local communities. Several waste audit studies explored best practices, which may require ethical approvals in certain countries. Most reports did not disclose their funding sources; however, some indicated that they received funding from universities and the public. The scores from the eight questions, which assess the potential risk of bias, ranged from 2/8, signifying a high risk, to 5/8. Concerns regarding potential bias were because of i) a failure to segregate monomaterial waste from layered material waste, ii) a lack of segregation between non-polymerised material and polymerised polymeric materials, and iii) the inability to distinguish the quantities of different hard and soft polymers, including HDPE, LDPE, PET, PP, PS, PVC, SR, and elastomers. Two studies were evaluated against fewer criteria because of their particular study objectives [5, 32] (Table 3).

Results of individual studies

Numerous studies failed to provide estimates of the mean mass of polymer waste per patient, procedure, day, and year. These estimates had to be derived from other data presented within the papers. The polymer waste per patient information is sourced from six studies [5, 26, 28, 29, 32, 33]. Estimates of the waste attributed to specific items per patient are ~81 g of aprons [33], 4 to 56 g of gloves [26, 28, 29, 32, 33], 13 to 24 g of impression materials [32, 33], 3 to 17 g of masks [32, 33], and 3 g of suction tips [29]. A substantially higher estimate of polymer waste per patient is 384 g, due to discarded single-use items [5]. Nine studies provided data to enable estimates of polymer waste per operatory room per day [5, 19, 20, 24, 26, 28,29,30, 33]. The amount of waste in hospital operating theatres is not directly transferable to oral healthcare clinics [30], but PET predominates, which has also been identified as the primary aerosol contaminant in oral healthcare clinics [41].

The estimated total annual mass of SUP waste from 47,000 oral healthcare professionals in the United Kingdom who perform operative procedures on five patients per day for 160 days per year is 14.4 tonnes [5]. If additional COVID-19 protection is required for the clinic staff, the estimate becomes 27 tonnes [5]. With these premises, a single professional generates 307.2 kg of SUP waste per year, 1.92 kg per day, and 384 g per patient. If additional COVID-19 protection for the working staff is required, the estimates are 575.2 kg per year, 3.6 kg per day and 719 g per patient. The estimates surpass those based on waste audits conducted in Iran [21,22,23, 25, 27] and the USA [30].

Considering the various study designs, potential biases, and evaluated outcomes, we found it unfeasible to combine the data in a meta-analysis (Table 4).

Polymer pollution into air and waterways

On-site sampling studies of polymer pollution in oral healthcare clinics have concentrated on the emissions of polymer NMP into the ambient air during actual clinical interventions [34,35,36, 38,39,40,41]. One study conducted in a hospital clinic contributes to the existing data by describing aerosolised polymer pollution produced in a cardiothoracic surgical operating theatre [37] (Table 5).

Study characteristics

The study clinics varied markedly and included one open-concept clinic comprising six units [39], one public clinic [38], one hospital operating theatre with an adjoining anaesthetic room [37], and six clinics (three private and three public) featuring between one and seven operatories [34]. The participants and sample sizes ranged from n = 10 [39], to n = 84 adult patients undergoing 253 procedures [38]. Additionally, the interventions varied, with the dental interventions comprising routine adult dental care [34, 38], or orthodontic bonding and debonding [39]. The analytic technologies included optical particle sizers, mass concentration measurements using laser photometers, personal samplers for microbial analysis, glass sampling beakers analysed via micro-Fourier-transform infra-red spectroscopy, and thermal desorption tubes examined with gas chromatographs. Ultimately, the results comprised particle count (n/m³) or particle mass concentrations (ng/m³), the distribution of chemical compounds, and monomer concentration above the patient’s mouth and in the clinician’s breathing zone (Table 6).

Risk of bias

The potential risk of bias was considered low for two studies [34, 37]. The other two papers lacked detailed information regarding the calibration process for the analytical equipment and were therefore considered to have a low to moderate risk of bias [38, 39] (Table 7).

Results of individual studies

Working with polymer materials in patients’ mouths releases NMPs containing 2-HEMA and TEGDMA, with the highest concentrations found just above the patients’ mouths. Still, these rapidly dilute further from the working area [34]. Hospital surgeons are exposed to atmospheric NMPs, with the predominant compounds being volatilised PET, PP, PE, and nylon [37]. The quantity and dimensions of NMPs in dental clinics are influenced by the type of rotating burs and other work instruments clinicians use [38]. Ultimately, the quantity of NMPs increases during work procedures but may surge even higher after the procedures are completed [39] (Table 8).

Any meta-analysis was deemed unsuitable due to the heterogeneity of study designs and outcomes measured.

Waste landfill disposal and monomeric eluates or polymer NMPs

The potential pollution from waste containing polymers deposited in municipal landfills has been explored only by a limited number of studies by a research group in Sheffield, U.K. [42,43,44,45,46,47] (Table 9).

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the various simulation studies conducted by one research group at the University of Sheffield, U.K., were relatively consistent. A common feature is that polymer specimens or NMPs produced from these specimens were stored in solutions mimicking municipal landfill conditions, including incubation in sterilised and non-sterilised landfill leachate [43, 44], ‘microcosms’ storage for three months [45], and groundwater at 10 °C for 12 months [46], or in tap water for 12 months [47]. Various analytical methods, including chromatography, spectrometry, potentiometry, and electron microscopy, were utilised to identify particle compounds, dimensions, and protonation-deprotonation behaviours across multiple pH levels and time points (Table 10).

Risk of bias

The data from the simulation studies were presented at IADR research meetings [42, 43, 45, 46], and in proceedings from one conference [44]. The possibility of thoroughly assessing all methodological aspects of the experiments is limited; thus, their risk of bias is high when considered individually. However, the results are either summarised or referenced in a single peer-reviewed publication, which has been deemed to have a low risk of bias [47] (Table 11).

Results of individual studies

The experiments carried out by the research group over a decade yield incremental findings. The initial study, conducted in 2015, outlines the leakage of predominantly Urethane Dimethacrylate (UDMA) and Triethylene Glycol Dimethacrylate (TEGDMA) monomeric compounds from resin-based composite (RBC) waste [42]. The subsequent reports describe how aged NMPs exhibit markedly different surface characteristics compared with fresh NMP, as well as compelling data indicating the role of microorganisms in the degradation process and the release of eluates [43,44,45,46]. The latest experiments provided further evidence of the likelihood that the behaviour of protonation and deprotonation across the pH range creates surface groups capable of binding at sites involving carboxyl (pK≈3–5), silanol/silica (pK≈6–7), and hydroxyl groups (pK>8) [45, 47] (Table 12).

Discussion

Limitations of the evidence

Potentially biased data estimates

We identified a significant potential bias using our custom scale, which should not be construed as a criticism of the reported waste audit procedures. In most countries, national regulatory policies govern waste audits across various sectors, emphasising societal needs and requirements. Waste is typically categorised into five fractions: infectious waste, domestic-type waste, toxic chemicals, sharps, and other hazardous waste. Identifying the proportion of polymer waste relative to the total waste amount is challenging and necessitates secondary calculations of the presented data in the original primary studies (Table 4). To better estimate the potential environmental impacts of polymer waste, data should differentiate between aspects such as monomaterial polymers (recyclable) versus layered materials (seldom recyclable), polymerised versus unused non-polymerised scrap materials, and ideally, provide separate information on different polymers, including HDPE, LDPE, PET, PP, PS, PVC, synthetic rubbers and elastomers.

The most common method for quantifying polymer waste involves directly weighing the accumulated waste, provided that end users have adequately segregated the various materials, ideally distinguishing between potentially recyclable items and complex polymers [48]. Random waste selections from storage solutions may be taken from multiple sites or over time to alleviate logistical challenges, provided these are replenished regularly. A more expedient alternative to weighing is to count the number of different polymer items and correlate these counts with known weights. Another option is to complete pre- and post-surgery inventory lists to record waste quantities. One could also argue that reviewing waste consignment or transfer records, or other waste management records or invoice lists, should suffice for estimating polymer waste in comparison to different categories of waste. Which method comes closest to accuracy remains unclear, and ultimately, hospital managers must consider allocating busy healthcare staff to engage in direct patient care rather than other activities [49].

Polymer waste reflected by patient demographics and delivered care

Waste generation and management in oral healthcare clinics is a recurring topic in national and international dental and medical journals. However, the number of research papers detailing the qualities and quantities of polymer waste and other waste remains limited. Moreover, the polymer waste produced in oral healthcare clinics will vary significantly depending on the level of care and range of interventions [5]. One must also consider the socioeconomic and cultural contexts of clinician–patient cohorts. Some studies have presented separate analyses of polymer waste generated in public versus private clinics and urban versus rural communities. The heterogeneity of clinical variables renders comparisons between different publications challenging and undermines the validity of any meta-analyses. Unfortunately, there is very little scientific research data available for analysis. A recent exhaustive scoping review concluded that the generalisability of waste audit data within the oral healthcare sector is unreliable, citing several arguments in support of this conclusion [50]. A recent publication from the United Kingdom best represents contemporary clinical practices in developed countries [5]. These estimates were based on a 4-day work week over 40 weeks, with an average of five operative procedures daily.

In Norway, official statistics and research indicate that the average dentist works 230 days a year and treats 10 patients daily [51, 52]. Based on U.K. estimates, the average dentist in Norway generates 883 kg of waste each year solely from polymer SUP refuse. If additional PPE is required during a pandemic, this figure rises to 1654 kg each year.

Polymer biomedical or domestic-type waste

A complicating factor in estimating the amount of polymer waste from oral healthcare clinics is that most studies limit their reporting to the mass of hazardous waste compared to domestic-type waste, following guidance from the World Health Organisation [53,54,55], rather than focusing on the type of material. Furthermore, the packaging of goods and devices has often been overlooked in many of these waste audits, likely leading to an underestimation of the impact of the widespread use of polymer wrapping and barrier foil [5]. The amount of polymer waste can vary by country depending on national legislation that requires mandatory cross-contamination practices. For instance, creating ‘plastic film barriers’ may be compulsory in some countries. Conversely, in others, it may be optional, depending on the circumstances, and even viewed as overly cautious by some [56]. Finally, limited research has documented the outcomes of audits regarding the appropriate waste receptacles set up in clinics and the level of compliance with proper segregation of polymer and other waste, a vital step for ensuring adequate waste stream disposal.

Polymer waste management

Managing polymer waste at local, national, and international levels has a significant impact on the global environmental footprint of the oral healthcare sector. Depending on local demographics, the logistics infrastructure for effective polymer waste collection and management may be centralised or decentralised [57]. Regrettably, such deployment remains impractical in numerous countries for several reasons, primarily because optimal technologies are costly and require substantial resources [3]. Open waste burning continues to be practised in various parts of the world, alongside other mismanagement practices that may account for 80–90% of all public waste [58]. The degree to which polymer waste from oral healthcare facilities contributes remains unclear.

Elastomer waste proportion of the total waste estimate

Several publications indicate a significant quantity of waste referred to as ‘impression materials’; however, they do not specify the nature of this material [21, 23]. The lack of detail introduces confounding factors since some impression materials are recyclable. For instance, impression plaster and hydrocolloid biopolymers, such as alginate derived from brown seaweed, can be recycled. Conversely, elastomers, made from synthetic polymers, are specifically designed not to degrade. Furthermore, the environmental impacts of the most common dental impression elastomers—condensation silicone, polyether, polysulfide, polyvinyl siloxane, and vinylsiloxanether will likely differ from a comprehensive life cycle perspective. Compounding the difficulty in estimating polymer waste amounts, clinicians often fabricate models from impressions in-house before discarding the impression rather than sending it to a dental laboratory. Estimating elastomer waste is challenging, as impression tray options vary between metal, single-use plastic, and custom-made from a mouldable polymer material. While the former requires manual removal, cleaning, and sterilisation, the latter is typically discarded entirely [59].

Product monomeric-polymer contents

Public information on the environmental footprint of manufacturing items containing polymers for the oral healthcare sector is virtually nonexistent. Monomers and polymers that form the basis of products in oral healthcare clinics can be classified as more or less sustainable, according to the ‘green metric’ [48]. Polymers designed for medical use often have significant environmental impacts due to the manufacturing and subsequent refining processes needed to reduce monomer residues and contaminants that could compromise biocompatibility.

Limitations of the review processes

The data presented in this paper likely reflect publication bias from a planetary perspective, as we included only scientific studies published in English. It is acknowledged that developing countries face the most significant challenges relating to waste management, and data is likely available in publications written in native languages. The authors lacked the multilingual interpretation skills and resources to appraise non-English literature online or in alternative bibliometric databases. We were unable to investigate publication bias and small-study effects due to the limited number of identified studies.

Certainty assessment

Despite exhaustive searches, the number of identified records was limited. Although the risk of bias was considered low for many of the studies, the extrapolation to how the measured eluates and NMPs may affect the environment remains uncertain. The heterogeneity of study designs, measurement methodologies, and outcomes prevented the undertaking of meta-analyses. Our pre-hoc choice of at least five studies for undertaking a meta-analysis is because statistical power is low with fewer than five studies [60]. In summary, the current evidence to answer the research question, ‘How much polymer waste and pollution is generated in oral healthcare clinics?’ is limited.

Implications for practice, policy, and future research

Synthetic polymers versus biopolymers

There has been a growing demand for polymers synthesised from sources other than petrochemicals. Biopolymers have emerged as a viable alternative; however, there is limited data on their performance. While some benefits exist in mitigating specific environmental impacts, other challenges remain or are created [61]. Moreover, a notable variation in the biodegradability of products promoted as biopolymers necessitates careful interpretation of the data [62]. Commercial products must demonstrate compliance with standards for the biodegradation of polymers established by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). The relevant standards for aerobic biodegradation include composting (ISO 14855), soil burial (ISO 17556), and water (ISO 14851 and ISO 14852). The applicable standards for anaerobic biodegradation focus on high solid decomposition (ISO 15985) and water (ISO 14853).

Polymers used in cross-contamination practices

Using polymer barrier foils is a legislated practice in certain countries to prevent cross-contamination and optional in others. However, this practice may result in excessive usage and has even been deemed redundant in most circumstances [56].

Waste audits in healthcare clinics

The waste audits published in hospital and oral healthcare clinics were challenging to evaluate since the reported data was presented in a generic format or categorised according to descriptors in guidance documents developed by the World Health Organisation [53]. However, these lack the necessary details to enable comparisons of polymer waste across different healthcare clinics. Future studies should adhere to recommendations for best practices and reporting waste audits in healthcare environments [49].

Healthcare waste management practices

Numerous papers have outlined best practices for waste management in healthcare clinics [54]. Moreover, innumerable surveys of oral healthcare providers and their staff suggest very high compliance, although opinions vary on the validity of these conclusions. One may also question the use of many non-validated questionnaires and survey designs [63]. Scientists have sought to understand how improved adherence to best waste management practices can be achieved [64]. Focusing on adequate waste segregation and the responsible disposal of each component diminishes environmental impacts and societal costs [65]. Robust advocacy for environmental sustainability within the UK’s oral healthcare sector fosters a sense of optimism about the future [65,66,67].

One aspect that should be more effectively addressed in healthcare clinics is unwrapping multiple sterile PIDs in preparation for surgery [68]. The practice is required when there is a high chance of adverse events; however, PIDs can be unwrapped sequentially depending on the circumstances during the surgery [69].

Waste pollution from PIDs

The data presented by the research group in Sheffield over a decade is compelling evidence that terrestrial microbiomes can degrade polymer waste containing RBC residues and particulates. The first experiment from 2015 emphasised the influence of molecular weight, hydrophilicity, diffusion rates, and the high surface areas of polymer NMPs [42]. The following two reports provide evidence of bacterial-mediated degradation of polymer NMPs in landfill leachate [43, 44]. Even later titles such as ‘Environmental Pollution From the Microparticulate Waste of CAD/CAM Resin-based Composite‘ [45], and ‘Elution of Resin-based Composite Monomers into Groundwaters’ [46], appear to have initiated research elsewhere. The 2021 peer-reviewed publication provided further insights into the degradation of RBC residues and particulates [47]. The research team voiced concerns the following year in the British Dental Journal [70], but neither scientific communities nor the public media appear to have taken extensive action.

Modern wastewater treatment facilities can effectively remove nano- and microparticle-size materials [71]. However, such facilities necessitate significant investments and are energy-intensive, making them unattainable in many parts of the world due to economic constraints [72].

Polymer waste management globally

The extent to which global polymer waste is disposed of according to best disposal practices and subjected to pyrolysis, recycling, or reuse remains unknown. Estimates suggest that the proportion of waste from polymer products ending up in private and municipal landfills varies from 25% in Europe, 22% to 43% in the USA, and 66% in India [7, 73]. Unfortunately, additional unknown quantities of hazardous chemicals and compounds are released from uncontrolled open dumpsites to terrestrial ecosystems [74], or inefficient open-burning [75], resulting in the release of persistent organic pollutants into the atmosphere [76], and waterways [72].

Polymer waste and pollution likely impact human and planetary health

To limit the length of this SR, we have not addressed in further detail the potential hazards posed by polymer waste and degradation products to humans [6, 77], and planetary ecosystems [78]. Additional degradation occurs in marine and terrestrial environments, rendering polymer NMPs potential vectors for health hazards to living organisms [79, 80], and our planet [81, 82]. There is a strong international consensus that there is a need to end plastic pollution, and creating a culture of striving for a circular economy is one means to achieve this objective [83].

Conclusions

Our understanding of the short- and long-term effects of polymer degradation and monomer elution on human and planetary health is limited. There is no doubt that a consensus exists on the need to mitigate monomeric eluate and polymer NMP pollution; however, multiple challenges remain to be addressed [84]. Oral healthcare professionals must collaborate in transdisciplinary research with environmental researchers, policymakers, and other stakeholders to identify knowledge gaps and develop sustainable solutions to minimise the environmental impact of polymer waste within the oral healthcare sector.

Data availability

Data are provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Cohen J, Rodgers Y van der M. Contributing factors to personal protective equipment shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev Med. 2020;141:106263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106263.

Walsh LJ. Reusable personal protective equipment viewed through the lens of sustainability. Int Dent J. 2024;74:S446–S454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.identj.2024.07.1270.

Zhao X, Klemeš JJ, Fengqi You. Energy and environmental sustainability of waste personal protective equipment (PPE) treatment under COVID-19. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2022;153:111786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.111786.

Antoniadou M, Varzakas T, Tzoutzas I. Circular economy in conjunction with treatment methodologies in the biomedical and dental waste sectors. Circ Econ Sustain. 2021;1:563-92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43615-020-00001-0.

Martin N, Mulligan S, Fuzesi P, Hatton PV. Quantification of single use plastics waste generated in clinical dental practice and hospital settings. J Dent. 2022;118:103948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2022.103948.

Gopinath PM, Parvathi VD, Yoghalakshmi N, Kumar SM, Athulya PA, Mukherjee A, et al. Plastic particles in medicine: a systematic review of exposure and effects to human health. Chemosphere. 2022;303:135227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.135227.

Jiao H, Ali SS, Alsharbaty MHM, Elsamahy T, Abdelkarim E, Schagerl M, et al. A critical review on plastic waste life cycle assessment and management: challenges, research gaps, and future perspectives. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2024;271:115942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2024.115942.

Jambeck JR, Geyer R, Wilcox C, Siegler TR, Perryman M, Andrady A, et al. Marine pollution. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science. 2015;347:768–71. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1260352.

Landrigan PJ, Stegeman JJ, Fleming LE, Allemand D, Anderson DM, Backer LC, et al. Human health and ocean pollution. Ann Glob. Health. 2020;86:151 https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.2831.

Landrigan PJ, Raps H, Cropper M, Bald C, Brunner M, Canonizado EM, et al. The Minderoo-Monaco Commission on Plastics and Human Health. Ann Glob. Health. 2023;89:23 https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.4056.

Malik S, Maurya A, Khare SK, Srivastava KR. Computational exploration of bio-degradation patterns of various plastic types. Polymers. 2023;15:1540. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15061540.

Alijagic A, Suljević D, Fočak M, Sulejmanović J, Šehović E, Särndahl E, et al. The triple exposure nexus of microplastic particles, plastic-associated chemicals, and environmental pollutants from a human health perspective. Environ Int. 2024;188:108736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2024.108736.

Wagner M, Monclús L, Arp HPH, Groh, K. J, Løseth, M. E., Muncke, J. et al. State of the science on plastic chemicals - identifying and addressing chemicals and polymers of concern. Zenodo; 2024. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10701706.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. J Clin. Epidemiol. 2021;134:178–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.03.001.

Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, Katikireddi SV, Brennan SE, Ellis S, et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ. 2020;368:l6890 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l6890.

UK Government. Healthcare waste: appropriate measures for permitted facilities - Waste pre-acceptance, acceptance and tracking appropriate measures - Guidance - GOV.UK. 2021. Accessed 20 Feb 2025. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/healthcare-waste-appropriate-measures-for-permitted-facilities/waste-pre-acceptance-acceptance-and-tracking-appropriate-measures.

McKenzie JE, Brennan SE, Ryan RE, Thomson HJ, Johnston RV. Summarizing study characteristics and preparing for synthesis. In: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2019:229–40.

McKenzie JE, Brennan SE. Synthesizing and presenting findings using other methods. In: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2019:321–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119536604.ch12.

Ozbek M, Sanin FD. A study of the dental solid waste produced in a school of dentistry in Turkey. Waste Manag. 2004;24:339–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2003.08.002.

Kizlary E, Iosifidis N, Voudrias E, Panagiotakopoulos D. Composition and production rate of dental solid waste in Xanthi, Greece: variability among dentist groups. Waste Manag. 2005;25:582–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2004.10.002.

Nabizadeh R, Koolivand A, Jafari AJ, Yunesian M, Omrani G. Composition and production rate of dental solid waste and associated management practices in Hamadan, Iran. Waste Manag Res J Int Solid Wastes Public Clean Assoc ISWA. 2012;30:619–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X11412110.

Nabizadeh R, Faraji H, Mohammadi AA. Solid waste production and its management in dental clinics in Gorgan, Northern Iran. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2014;5:216–21.

Amouei A, Faraji H, Samani AK, Samani MK. Quantity and quality of solid wastes produced in dental offices of Babol city. Casp J Dent Res. 2016;5:44–49.

Richardson J, Grose J, Manzi S, Mills I, Moles DR, Mukonoweshuro R, et al. What’s in a bin: a case study of dental clinical waste composition and potential greenhouse gas emission savings. Br Dent J. 2016;220:61–66. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.55.

Majlesi M, Alavi NA, Mohammadi AA, Valipor S. Data on composition and production rate of dental solid waste and associated management practices in Qaem Shahr, Iran 2016. Data Brief. 2018;19:1291–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2018.05.114.

Mandalidis A, Topalidis A, Voudrias EA, Iosifidis N. Composition, production rate and characterization of Greek dental solid waste. Waste Manag. 2018;75:124–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2018.01.035.

Momeni H, Tabatabaei Fard SF, Arefinejad A, Afzali A, Talebi F, Rahmanpour Salmani E. Composition, production rate and management of dental solid waste in 2017 in Birjand, Iran. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2018;9:52–60. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijoem.2018.1203.

Voudrias EA, Topalidis A, Mandalidis A, Iosifidis N. Variability of Greek dental solid waste production by different dentist groups. Environ Monit Assess. 2018;190:418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-018-6803-3.

Aghalari Z, Amouei A, Jafarian S. Determining the amount, type and management of dental wastes in general and specialized dentistry offices of Northern Iran. J Mater Cycles Waste Manag. 2020;22:150-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10163-019-00924-3.

Wyssusek K, Keys M, Laycock B, Avudainayagam A, Pun K, Hansrajh S, et al. The volume of recyclable polyethylene terephthalate plastic in operating rooms—a one-month prospective audit. Am J Surg. 2020;220:853–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.05.011.

Alstrom B. Audit of waste collected over one week from Superior Dental Health of Lincoln (Student theses). Department of Environmental Studies: Undergraduate. Published online January 1, 2021. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/envstudtheses/287.

Oxborrow DG, Dong C, Lin IF. Simulation clinic waste audit assessment and recommendations at the University of Washington School of Dentistry. J Dent Educ. 2024;88:623–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/jdd.13470.

Yeoh S, Bourdamis Y, Saker A, Marano N, Maundrell L, Ramamurthy P, et al. An investigation into contaminated waste composition in a university dental clinic: opportunities for sustainability in dentistry. Clin Exp Dent Res. 2024;10:e70015. https://doi.org/10.1002/cre2.70015.

Henriks-Eckerman ML, Alanko K, Jolanki R, Kerosuo H, Kanerva L. Exposure to airborne methacrylates and natural rubber latex allergens in dental clinics. J Environ Monit. 2001;3:302–5. https://doi.org/10.1039/b101347p.

Sotiriou M, Ferguson SF, Davey M, Wolfson JM, Demokritou P, Lawrence J, et al. Measurement of particle concentrations in a dental office. Environ Monit Assess. 2008;137:351–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-007-9770-7.

Polednik B. Aerosol and bioaerosol particles in a dental office. Environ Res. 2014;134:405–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2014.06.027.

Field DT, Green JL, Bennett R, Jenner LC, Sadofsky LR, Chapman E, et al. Microplastics in the surgical environment. Environ Int. 2022;170:107630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2022.107630.

Lahdentausta L, Sanmark E, Lauretsalo S, Korkee V, Nyman S, Atanasova N, et al. Aerosol concentrations and size distributions during clinical dental procedures. Heliyon. 2022;8:e11074. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11074.

Rafiee A, Carvalho R, Lunardon D, Flores-Mir C, Major P, Quemerais B, et al. Particle size, mass concentration, and microbiota in dental aerosols. J Dent Res. 2022;101:785–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220345221087880.

Tang F, Wen X, Zhang X, Qi S, Tang X, Huang J, et al. Ultrafine particles exposure is associated with specific operative procedures in a multi-chair dental clinic. Heliyon. 2022;8:e11127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11127.

Akhtar N, Tahir A, Qadir A, Masood R, Gulzar Z, Arshad M. Profusion of microplastics in dental healthcare units; morphological, polymer, and seasonal trends with hazardous consequences for humans. J Hazard Mater. 2024;479:135563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.135563.

Mulligan S, Kakonyi G, Thornton SF, Moharamzadeh K, Fairburn A, Martin N. The environmental fate of waste microplastics from resin-based dental composite IADR Abstract Archives. In: IADR British Division Meeting. 2015. Accessed June 2, 2024. https://iadr.abstractarchives.com/abstract/brit-iadr2015-2314833/the-environmental-fate-of-waste-microplastics-from-resin-based-dental-composite.

Mulligan S, Fairburn A, Kakonyi G, Moharamzadeh K, Thornton SF, Martin N. Optimal Management of Resin-Based Composite Waste: Landfill vs. Incineration IADR Abstract Archives. In: IADR/AADR/CADR General Session, 2017. Accessed June 2, 2024. https://iadr.abstractarchives.com/abstract/17iags-2625197/optimal-management-of-resin-based-composite-waste-landfill-vs-incineration.

Falyouna O, Kakonyi G, Mulligan S, Fairburn A, Moharamzadeh K, Martin N, et al. Behavior of dental composite materials in sterilized and non-sterilized landfill leachate | Collections | Kyushu University Library. In: Proceedings of the international exchange and innovation conference on engineering & sciences. 2018:72–76. Accessed June 2, 2024. https://hdl.handle.net/2324/1961288.

Mulligan S, Kakonyi G, Thornton SF, Ojeda JJ, Ogden M, Moharamzadeh K, et al. Environmental pollution from the microparticulate waste of CAD/CAM resin-based composite IADR abstract archives. In: IADR/PER General Session, 2018. Accessed June 2, 2024. https://iadr.abstractarchives.com/abstract/18iags-2957711/environmental-pollution-from-the-microparticulate-waste-of-cadcam-resin-based-composite.

Martin N, Mulligan S, Thornton S, Kakonyi G, Moharamzadeh K. Elution of resin-based composite monomers into groundwater IADR abstract archives. 2019. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://iadr.abstractarchives.com/abstract/bsodr-iadr2019-3231160/elution-of-resin-based-composite-monomers-into-groundwater.

Mulligan S, Ojeda JJ, Kakonyi G, Thornton SF, Moharamzadeh K, Martin N. Characterisation of microparticle waste from dental resin-based composites. Materials. 2021;14:4440. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14164440.

Tabone MD, Cregg JJ, Beckman EJ, Landis AE. Sustainability metrics: life cycle assessment and green design in polymers. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44:8264-9. https://doi.org/10.1021/es101640n.

Slutzman JE, Bockius H, Gordon IO, Greene HC, Hsu S, Huang Y, et al. Waste audits in healthcare: a systematic review and description of best practices. Waste Maag Res J. 2023;41:3–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X221101531.

Mitsika I, Chanioti M, Antoniadou M. Dental solid waste analysis: a scoping review and research model proposal. Appl Sci. 2024;14:2026. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14052026.

Statistics Norway. Dental health care. SSB. Accessed February 20, 2025. https://www.ssb.no/en/helse/helsetjenester/statistikk/tannhelsetenesta.

Grytten J, Listl S, Skau I. Do Norwegian private dental practitioners with too few patients compensate for their loss of income by providing more services or by raising their fees? Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2023;51:778–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdoe.12750.

Prüss A, Emmanuel J, Stringer R, et al. Safe Management of Wastes from Health-Care Activities/Edited by A. Prüss …[et al.]. 2nd ed. World Health Organization; 2014. Accessed February 17, 2025. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/85349.

World Health Organization. Safe Management of Wastes from Health-Care Activities: A Summary. World Health Organization; 2017. Accessed February 9, 2025. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/259491.

WHO fact sheet on healthcare waste. Health-care waste. Accessed February 20, 2025. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/health-care-waste.

Duane B, Ashley P, Ramasubbu D, Fennell-Wells A, Maloney B, McKerlie T, et al. A review of HTM 01-05 through an environmentally sustainable lens. Br Dent J. 2022;233:343–50. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-022-4903-5.

Chen HL, Nath TK, Chong S, Foo V, Gibbins C, Lechner AM. The plastic waste problem in Malaysia: management, recycling and disposal of local and global plastic waste. SN Appl Sci. 2021;3:437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-021-04234-y.

Ramadan BS, Rachman I, Ikhlas N, Kurniawan SB, Miftahadi MF, Matsumoto T. A comprehensive review of domestic-open waste burning: recent trends, methodology comparison, and factors assessment. J Mater Cycles Waste Manag. 2022;24:1633–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10163-022-01430-9.

Komilis DP, Voudrias EA, Anthoulakis S, Iosifidis N. Composition and production rate of solid waste from dental laboratories in Xanthi, Greece. Waste Manag. 2009;29:1208-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2008.06.043.

Valentine JC, Pigott TD, Rothstein HR. How many studies do you need? A primer on statistical power for meta-analysis. J Educ Behav Stat. 2010;35:215-47. https://doi.org/10.3102/1076998609346961.

Unger SR, Hottle TA, Hobbs SR, Thiel CL, Campion N, Bilec MM, et al. Do single-use medical devices containing biopolymers reduce the environmental impacts of surgical procedures compared with their plastic equivalents?. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2017;22:218–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/1355819617705683.

Lavagnolo MC, Poli V, Zampini AM, Grossule V. Biodegradability of bioplastics in different aquatic environments: a systematic review. J Environ Sci China. 2024;142:169–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2023.06.013.

Mannocci A, di Bella O, Barbato D, Castellani F, La Torre G, De Giusti M, et al. Assessing knowledge, attitude, and practice of healthcare personnel regarding biomedical waste management: a systematic review of available tools. Waste Manag Res J. 2020;38:717–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X20922590.

Lakhani B, Givati A. Perceptions and decision-making of dental professionals to adopting sustainable waste management behaviour: a theory of Planned Behaviour analysis. Br Dent J. Published online October 4, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-024-7907-5.

Wilmott S, Duane B. An update on waste disposal in dentistry. Br Dent J. 2023;235:370-2. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-023-6359-7.

Duane B, Ramasubbu D, Harford S, Steinbach I, Swan J, Croasdale K, et al. Environmental sustainability and waste within the dental practice. Br Dent J. 2019;226:611–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-019-0194-x.

Duane B, ed. Sustainable dentistry: making a difference. Springer International Publishing; 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-07999-3.

Hashemizadeh A, Lyne A, Liddicott M. Reducing single-use plastics in dental practice: a quality improvement project. Br Dent J. 2024;237:483-6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-024-7836-3.

Bravo D, Thiel C, Bello R, Moses A, Paksima N, Melamed E. What a waste! The impact of unused surgical supplies in hand surgery and how we can improve. HAND. 2023;18:1215-21. https://doi.org/10.1177/15589447221084011.

Mulligan S, Hatton PV, Martin N. Resin-based composite materials: elution and pollution. Br Dent J. 2022;232:644-52. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-022-4241-7.

Cristaldi A, Fiore M, Zuccarello P, Oliveri Conti G, Grasso A, Nicolosi I, et al. Efficiency of wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) for microplastic removal: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:8014 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218014.

Lin HT, Schneider F, Aziz MA, Wong KY, Arunachalam KD, Praveena SM, et al. Microplastics in Asian rivers: geographical distribution, most detected types, and inconsistency in methodologies. Environ Pollut. 2024;349:123985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2024.123985.

US EPA Organization. Plastics: Material-Specific Data. September 12, 2017. Accessed February 20, 2025. https://www.epa.gov/facts-and-figures-about-materials-waste-and-recycling/plastics-material-specific-data.

Siddiqua A, Hahladakis JN, Al-Attiya WAKA. An overview of the environmental pollution and health effects associated with waste landfilling and open dumping. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2022;29:58514-36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-21578-z.

Velis CA, Cook E. Mismanagement of plastic waste through open burning with emphasis on the global south: a systematic review of risks to occupational and public health. Environ Sci Technol. 2021;55:7186-207. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c08536.

Ni HG, Lu SY, Mo T, Zeng H. Brominated flame retardant emissions from the open burning of five plastic wastes and implications for environmental exposure in China. Environ Pollut Barking Essex 1987. 2016;214:70-76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2016.03.049.

Borgatta M, Breider F. Inhalation of microplastics—a toxicological complexity. Toxics. 2024;12:358. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics12050358.

de Souza Machado AA, Kloas W, Zarfl C, Hempel S, Rillig MC. Microplastics as an emerging threat to terrestrial ecosystems. Glob Change Biol. 2018;24:1405–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14020.

Schmalz G, Hickel R, van Landuyt KL, Reichl FX. Nanoparticles in dentistry. Dent Mater. 2017;33:1298-314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2017.08.193.

Leso V, Battistini B, Vetrani I, Reppuccia L, Fedele M, Ruggieri F, et al. The endocrine-disrupting effects of nanoplastic exposure: a systematic review. Toxicol Ind. Health. 2023;39:613–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/07482337231203053.

Brar SK, Verma M, Tyagi RD, Surampalli RY. Engineered nanoparticles in wastewater and wastewater sludge—evidence and impacts. Waste Manag. 2010;30:504-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2009.10.012.

Froggett SJ, Clancy SF, Boverhof DR, Canady RA. A review and perspective of existing research on the release of nanomaterials from solid nanocomposites. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2014;11:17. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-8977-11-17.

United Nations Environment Programme. Turning off the tap: how the world can end plastic pollution and create a circular economy. United Nations Environment Programme; 2023. https://doi.org/10.59117/20.500.11822/42277.

Kibria MDG, Masuk NI, Safayet R, Nguyen HQ, Mourshed M. Plastic waste: challenges and opportunities to mitigate pollution and effective management. Int J Environ Res. 2023;17:20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41742-023-00507-z.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude to Dr. P.L. Fan, former Director of ADA International Science and Standards, for his expert guidance on the scientific content and potential bias, as well as his constructive criticism of the draft manuscript.

Funding

The authors did not receive any external funds to support this research. The open-access APC was funded through the Norwegian Directorate for Higher Education and Skills. Open access funding provided by UiT The Arctic University of Norway (incl University Hospital of North Norway).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M.G. and A.J. conceptualised and designed the study, collected the data, analysed the results, interpreted the data and drafted the paper. Both authors reviewed, revised and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests. This review analyses only existing, publicly available data and does not include new data collection or the processing of identifiable personal information. Therefore, ethical approval is not required according to Norwegian research ethics guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gussgard, A.M., Jokstad, A. Polymer waste and pollution in oral healthcare clinics: a systematic review. BDJ Open 11, 52 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41405-025-00342-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41405-025-00342-8