Abstract

Uniform assessment of response to treatment is crucial to managing multiple myeloma (MM) and developing new therapies. Measurement of monoclonal protein forms the cornerstone of disease assessment in MM. According to International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) guidelines, serum-free light chain (sFLC) is included in MM response assessment in patients with no measurable disease by electrophoresis and to define stringent complete response. We retrospectively analyzed the independent value of serial FLC on response and progression assessments in 839 patients with measurable disease by sFLC as well as serum/urine electrophoresis. A significant association was observed between sFLC and electrophoretic responses during initial therapy and at best response (p < 0.001). This study revealed comparable percentage changes in serial dFLC and urine M-protein, with parallel trends (p < 0.001) and strong correlations (r 0.55–0.79, p < 0.001). The response was detected earlier by sFLC (1.1 months, 95% CI 1.06–1.17), and sFLC ≥ PR after two cycles of induction demonstrated a strong predictive value for subsequent electrophoresis responses (OR 9.33, p < 0.001). Following induction, no difference in PFS was observed between very good partial response (VGPR) as determined by sFLC, sPEP, and uPEP (p = 0.538). The median second-PFS for patients with only sFLC-progression disease (PD) was similar to those with urine M-protein PD with or without sFLC-PD (HR 1.28, 95% CI 0.77–2.13, p 0.334). However, the median overall survival from the first relapse was significantly better for patients with only sFLC-PD (HR 1.87, 95% CI 1.07–3.27, p 0.03). Among patients with PD, 12% had sFLC as the only detectable tumor marker at the time of second-line therapy. This study supports the incorporation of serial sFLC measurements for monitoring response and progression in MM, even in patients with electrophoretic measurable disease, and further advocates replacing 24-h urine with serial sFLC in response assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A better understanding of the biology and clinical behavior of multiple myeloma (MM) has translated to improvement in treatment approaches and outcomes [1,2,3]. The treatment landscape in newly diagnosed MM has undergone a remarkable evolution with the introduction of many immunotherapies, which has led to deeper responses and better survival outcomes [4,5,6,7,8]. Integration of monoclonal antibodies as the backbone of anti-MM therapy, increasing utilization of bispecific antibodies, and chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR-T) are transforming the treatment paradigm for MM. [9,10,11,12,13,14]. However, with enhanced treatment efficacy, we need more sensitive tools to detect low levels of circulating monoclonal proteins for accurate response assessment and early relapse detection. Monoclonal (M) protein can be detected in the serum and/or urine of patients with MM as either intact immunoglobulins (Ig) or free light chains (FLC). The serum immunoglobulin-free light chain (sFLC) assay measures the serum levels of free kappa and lambda light chains [15, 16]. In MM, the elevated levels of sFLC reflect the tumor burden and, due to their shorter half-life compared to immunoglobulins, allow for an earlier assessment of the response to therapy [17, 18]. Serum FLC measurement is part of the new diagnostic criteria for MM and serves as a marker to monitor changes in tumor burden over time [19]. Over 90% of patients with Immunoglobulin-secretory MM (Ig-MM) and nearly all patients with light chain MM (LCMM) have detectable or measurable sFLC at diagnosis [20]. Advances in techniques, such as high-resolution electrophoresis and mass spectrometry, continue to improve the sensitivity of monoclonal protein detection but are still not routinely accessible in daily clinical practice.

According to IMWG guidelines, sFLC is included in the MM response assessment to define stringent complete response (sCR) [21]. Serial sFLC measurements are only indicated for evaluating response and progression in patients with no measurable M-protein in the serum or urine, as defined by IMWG response criteria, with at least 1 g/dL and 200 mg/24 h in the serum and urine, respectively [3]. M-protein should be measured using sPEP and/or uPEP at each assessment in these patients. If urine M-protein is not measurable at baseline, urine M-protein is not required to document partial or minor responses; however, it is necessary for complete and very good partial responses. Nevertheless, 24-h urine assessments remain burdensome for patients, resulting in inadequate adherence and failure to assess disease response, especially in the setting of clinical trials. Recent studies have suggested that serum-free light chain may be used in place of 24-h urine protein electrophoresis in most situations. This study was designed to determine how serial measurements of sFLC correlate with those of serum and urine-based assessments in monitoring response and progression in MM with serum and/or urine-measurable disease with standard electrophoretic methods. Additionally, we also evaluated whether serial measurements of sFLC can replace the 24-h urine protein electrophoresis as a measure of disease response in this cohort.

Patients and methods

Study population

This retrospective study included newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM) patients evaluated at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester between 2011 and 2021. Only patients with measurable levels of sFLC by FLC assay and M-protein by either serum electrophoresis (sPEP) and/or 24-h urine protein electrophoresis (uPEP) at baseline were included. We selected this population to compare changes in sFLC levels with those of M-protein measured by electrophoresis. According to the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG), measurable disease in MM is defined as follows: for serum FLC assay, involved FLC level ≥10 mg/dL, with an abnormal serum FLC ratio, for serum M-protein level ≥1 g/dL, and urine M-protein level ≥200 mg in 24-h urine [3]. The data for the following three variables, the difference between involved and uninvolved free light chains (dFLC), serum M-protein by sPEP, and urine M-protein by uPEP, were collected longitudinally during the study, in response to progression.

In the response set, available data for each biomarker were collected at baseline, after each cycle during induction therapy (4 cycles), and at the time of the best response. In the context of disease progression (PD), data for each biomarker were collected at three time points before the initiation of treatment and at the time of second-line therapy.

We excluded patients who did not have at least two serial measurements for each marker (dFLC, serum M-protein, and urine M-protein). All cohorts were stratified into different categories based on the presence of measurable M-protein in serum and/or urine, as detected by electrophoresis. Three categories were defined: (1) measurable M-protein in serum with either no measurable urine M-protein or no urine sample available, (2) measurable M-protein in both serum and urine, and (3) measurable M-protein only in the urine (light chain multiple myeloma, LCMM). As per the inclusion criteria, all patients had measurable FLC in serum.

After approval by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board, the medical records of approximately 3000 patients with NDMM between 2011 and 2021 were reviewed, and 839 patients met the study´s inclusion criteria. The study was conducted following the International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines on Good Clinical Practice and the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Monoclonal protein measurements

All measurements of monoclonal components (serum and urine M-protein) were prospectively performed and collected from the electronic medical records. Serum and urine M-protein were quantified by serum and urine electrophoresis (sPEP/uPEP). The serum FLC assay was performed using FREELITE (The Binding Site, Birmingham, United Kingdom). This assay measures two distinct components, kappa (k) and lambda (λ) free light chain, quantifying the concentration of each element separately and providing a ratio within a normal range of 0.26–1.65 [22]. In this study, the difference between involved and uninvolved free light chains (dFLC) was considered a primary variable of interest for comparison with serum and urine M-protein levels, measured by electrophoresis.

Response and progression definition

Response and progression assessments for each marker were classified according to the IMWG guidelines. We applied the IMWG response and progression criteria for MM with measurable serum and urine M-protein disease quantified by electrophoresis. FLC response and progression were evaluated based on changes in the difference between involved and uninvolved FLC levels, as established by the IMWG response criteria for the FLC measurable disease. FLC responses were outlined as follows: Very good partial response (VGPR) as a reduction of 90% or more of dFLC, Partial response (PR) as a reduction of more than 50%, and less than 90% of dFLC. FLC progression is defined as a 25% increase in dFLC and an absolute increase in involved FLC of at least 10 mg/dL.

The overall response rate (ORR) was described as the proportion of patients who achieved at least a partial response (≥PR). A summary of each category of response or progression for each marker is shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Statistical methods

Descriptive analysis of qualitative variables was conducted using frequency distributions, while continuous variables were described with median, range, and interquartile range. We directly compared response rates among the three biomarkers (serum and urine M-protein measured by sPEP/uPEP and serum dFLC) at different time points. A Fisher exact test of proportions was performed to test for the association between FLC response and standard (serum and urine) electrophoretic response after each treatment cycle during the first four cycles of induction and at the time of best response. All comparisons are displayed with chart bars. The same analysis was conducted in a progression context, comparing sPEP/uPEP, PD with serum FLC-PD. Three time points were identified based on the moment of PD detection, by either electrophoresis, FLC, or both, before starting the second line of treatment. The percentage changes of serum dFLC were compared with the percentage change of 24-h urine M-protein over time during the induction therapy. A Spearman’s correlation was conducted to determine the relationship between the absolute value of dFLC and urine M-protein during the induction therapy after each cycle.

This analysis was performed separately for patients with measurable M-protein in serum and urine and urine-only patients. Time to response was calculated as the time from the first day of the first cycle of treatment until the date of first documentation of at least partial response, according to the (IMWG) response criteria for MM with measurable disease, and is presented as median (95% confidence interval).

Survival analyses were estimated with the Kaplan–Meier method and compared by the 2-sided log-rank test. The analyses were conducted using the R language, and an alpha error of 0.05 was taken as the cut‐off for two‐sided p‐value statistical significance, and all confidence intervals (CI) were reported as 95% CI.

Results

Patient characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the 839 patients meeting the inclusion criteria are outlined in Table 1. Patients were classified into three groups based on the presence of measurable M-protein in serum and/or urine as defined by electrophoresis as described before. A total of 52.4% (n = 440) had measurable M-protein in serum, 27.2% (n = 228) had measurable M-protein in both serum and urine, and 24% (n = 171) had measurable M-protein only in the urine. Among patients with measurable paraprotein available only in serum at diagnosis, 60% had no measurable urine M-protein at baseline, while 40% did not have urine samples collected at the time of diagnosis. Within the total study population, nearly half of the patients, 47.6% (399), had measurable urine M-protein at baseline, 30.6% (257) had no measurable urine M-protein, and 21.8% (183) did not have urine samples available at diagnosis. In the urine-only group, we observed a higher median difference in FLC (303 mg/dL), creatinine levels (1.3 mg/dL), and monoclonal proteinuria (1.89 g/24 h), along with the lowest level of IgG (515 mg/dL).

As first-line treatment, the most common regimen consisted of a combination of novel agents, such as monoclonal antibodies (daratumumab), proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib, carfilzomib, ixazomib), immunomodulators (lenalidomide, pomalidomide), alkylating agents (cyclophosphamide), and dexamethasone within or outside of clinical trials. A total of 68.5% of patients underwent autologous transplants as part of first-line therapy. Overall, 17% of all patients had t (11; 14) at diagnosis; however, in the LCMM group, this percentage was higher (33%).

Response assessment

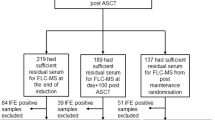

The overall response rates (ORR) were compared directly across three biomarkers after each cycle during the first four cycles of induction and at the time of the best response (Fig. 1). We evaluated each FLC response for association with each paraprotein response at the five time points.

After the first cycle of treatment, response rates for ≥very good partial response (VGPR) and partial response (PR) were as follows: based on serum dFLC (41.9%, 39.5%), serum M-protein (11%, 47%), and urine M-protein (50.3%, 16.6%). According to IMWG criteria, an ORR of ≥90% for dFLC was achieved after the second cycle, while for serum and urine paraprotein, measured by electrophoresis, this level was achieved after the fourth cycle of treatment.

We performed an additional analysis to evaluate alternative cutoffs for urine M-protein response, comparing them to serum markers. We examined a cutoff of ≥90% reduction in urine M-protein for VGPR-uPEP and a reduction between ≥50% and ≤90% for PR-uPEP. (Supplementary Fig. 1). Based on this modified criterion, the ORR for urine M-protein after each induction cycle was consistently higher than those assessed based on the standard IMWG criteria and more closely aligned with FLC response trends. A reduction of ≥90% for urine M-protein was observed after the second cycle of induction, as with sFLC.

At the time of best response, 98% of patients (824/839) achieved at least a PR based on sPEP/uPEP. Similarly, among the 817 samples available for FLC response assessment, 98% (810/817) also showed at least a PR at the time of best electrophoretic response. Among the 824 patients who achieved ≥PR by sPEP/uPEP, only 7 (<1%) patients did not achieve ≥PR by sFLC, including one patient who met the FLC progression criteria. Similarly, among the 810 patients who achieved ≥PR by sFLC, 7 (<1%) patients did not have an electrophoretic response.

Among the 83% (696/839) of patients who achieved ≥VGPR by sPEP/uPEP at their best response, 95% also achieved sFLC-VGPR. In contrast, among the 17% (141/839) of patients who did not achieve VGPR by sPEP/uPEP, 57% (80/141) had sFLC-VGPR. These results demonstrate that nearly half of the patients with less than VGPR by sPEP/uPEP, at their time of best response, had at least a 90% decline in monoclonal sFLC.

We also demonstrated that achieving an early FLC response (≥PR), after two cycles of induction, is a strong predictor of subsequent serological responses assessed by electrophoresis (sPEP/uPEP), with an odds ratio of 9.33 (95% CI: 2.76–31.5; P = 0.001). This early FLC response was also associated with a moderate reduction in the risk of progression with a hazard ratio of 0.77 (95% CI: 0.61–0.99; p = 0.046). Ninety-nine percent of early FLC responders (638/644) after the second cycle of induction eventually achieved an overall electrophoretic response.

Focusing on the 47.5% (399/839) of the total study population with measurable urine at diagnosis, 98% achieved at least a PR by sPEP/uPEP; all except two patients had also sFLC-PR. In the LCMM group, 99% (169/171) eventually achieved at least a PR based on uPEP. Furthermore, all LCMM responders by uPEP also had an FLC response during the first-line therapy. Additionally, when assessing the VGPR rate in LCMM patients, 96% of uPEP responders also achieved VGPR based on FLC evaluation.

Correlating responses and survival outcomes

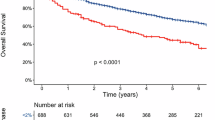

We compared the impact of achieving VGPR based on dFLC, serum M-protein by sPEP, and urine M-protein by uPEP on progression-free survival (PFS) after four cycles of induction treatment (Fig. 2A) for all cohorts and by splitting by monoclonal measurable groups (Fig. 2B). This analysis revealed that there were no statistically significant differences in PFS between VGPR responses assessed by dFLC, sPEP, and uPEP in all patients (p = 0.538) and by subgroups.

A Median progression-free survival (PFS), in patients achieving VGPR by serum-free light chain (sFLC), serum and urine M-protein by electrophoresis (SM-protein/UM-protein), after the fourth cycle of induction therapy. (All cohort). B Median progression-free survival (PFS), in patients achieving VGPR by serum-free light chain (sFLC), serum and urine M-protein by electrophoresis (SM-protein/UM-protein), after the fourth cycle of induction therapy. (Splitting by measurable M-protein).

Correlation between serum FLC and 24-h urine M-protein

The median percentage changes of dFLC and 24-h urine M-protein were analyzed and compared after each cycle of treatment during the induction. After the first cycle of treatment, we demonstrated a substantial median reduction in dFLC of 86%, with a comparable median percentage decline of 90% in 24-h urine M-protein. The median percentage reductions in subsequent cycles of therapy showed parallel trends, indicating consistent and similar reductions across both markers over time (Fig. 3). The correlation coefficients between changes in the absolute values of serum FLC and 24 h of urine M-protein after each cycle of treatment showed a moderate-strong correlation; cycle 1 (r 0.791, p < 0.001), cycle 2 (r 0.597, p < 0.001), cycle 3 (r 0.597, p < 0.001), and cycle 4 (r 0.540, p < 0.001). A strong correlation was also detected between dFLC and 24-h urine M-protein in the LCMM group, with coefficients ranging from 0.616 to 0.771. A similar analysis was conducted in the subgroup of patients with measurable urine M-protein at baseline (N = 399), where the correlation remained robust, ranging from 0.601 to 0.787. Consistent results were also observed in patients with renal insufficiency (creatinine ≥2 at diagnosis), with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.617 to 0.781 (Table 2).

Time to response

The number of patients assessed for response by dFLC, serum M-protein, and urine M-protein was 839 (100%)/668 (79.62%)/399 (47.56%). Patients were assessed for overall response (≥PR) and at least a very good partial (≥VGPR), resulting in 787/593/269 and 615/290/239 for dFLC, serum M-protein, and urine M-protein, respectively. The median time to partial response for all cohorts, detected earlier by dFLC (1.1 months, 95% CI: 1.06–1.17), in comparison with serum M-protein (1.5 months, 95% CI: 1.40–1.62) and urine M-protein (2.8 months, 95% CI: 2.42–3.10), with p < 0.001. (Fig. 4A). The median time to VGPR for all patients was significantly shorter for dFLC (2.00 months, 95% CI: 1.87–2.13) compared to serum M-protein (4.37 months, 95% CI: 4.072–4.67) and urine M-protein (3.12 months, 95% CI: 2.73–3.52) with p < 0.001. (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, the study demonstrated that the median time to VGPR was significantly shorter for urine M-protein, compared to serum M-protein (p < 0.001). (Fig. 4B). Table 3 presents a summary of the median time to responses.

We additionally analyzed the median time to partial response based on subcategories.

For the serum M-protein measurable by sPEP group, the median time to PR by dFLC was 1.2 months (95% CI: 1.06–1.24), which was significantly shorter than that observed by serum M-protein (1.48 months, 95% CI: 1.34–1.62) with (p < 0.001). Among patients with measurable M-protein in both serum and urine, the median time to response (TTR) by dFLC was 1.08 months (95% CI: 1.01–1.16), which was detected earlier compared to serum M-protein (1.51 months, 95% CI: 1.31–1.71), and urine M-protein (3.19 months, 95% CI: 2.57–3.80), p < 0.001. In patients with measurable urine-only M-protein at baseline, earlier detection of response by dFLC (1.12 months, 95% CI: 1.00–1.23) was observed, compared to urine M-protein (2.37 months, 95% CI: 2.00–2.73), p < 0.001 (Table 4).

Progression assessment

With a median follow-up of 53.3 (IQR 31.5–77.4) months, 54% (452/839) of patients experienced progression of disease (PD) by at least one of the biomarkers, as described previously. The median time from disease progression to the initiation of second-line therapy was 7 (IQR 0–17.7) days. At the time of the second line of treatment, the proportion of patients with sFLC-PD was higher than those with serum and urine electrophoretic PD, respectively (61%, 51%, and 24%, p = 0.001).

Among patients with confirmed PD based on sFLC (261/427), 24% (103/427) met PD criteria exclusively by sFLC per IMWG criteria. Of these 103 patients, none had PD criteria by sPEP, 48% (49/103) did not meet progression criteria by uPEP, and 52% (54/103) had no urine sample available; if we evaluate only those patients who had both serum and urine samples available at the time of assessing disease progression (excluding those with missing urine samples [54]), in 12% (49/427) of total patients with PD, sFLC was the only detectable tumor marker at the time of initiating a new line of treatment. Of these patients, 45% underwent bone marrow evaluation at the time of second line, which revealed >10% clonal plasma cells. Patients with sFLC-PD subsequently initiated a second line of therapy. Almost half of these patients were in the LCMM group.

Among patients with measurable M-protein in urine only (LCMM) at diagnosis, 52% (89/171) experienced PD. Within this group, 84% (75/89) showed PD by sFLC, and only 39% (26/67 available urine samples) by uPEP. All patients who met the urine progression criteria also met the PD criteria based on sFLC.

In patients with measurable urine M-protein at baseline, 59% (235/399) developed PD. However, only 19.5% (45/235) showed PD based on uPEP, while 67.6% (158/235) presented PD by sFLC. (Supplementary Table 2). All patients with progression by uPEP also had sFLC-PD; however, among 158 patients with sFLC-PD, only 28% (45/158) met the criteria for PD by uPEP, 57 patients (nearly one-third) did not fulfill PD criteria by urine M-protein, and another 56 (35%) did not have urine samples at the time of second line of treatment.

We next evaluated the clinical impact of PD type, comparing patients with sFLC-PD only to those with PD detected by uPEP, with or without sFLC-PD. The median second progression-free survival (PFS-2) for patients with only sFLC-PD was similar to those with urine M-protein PD with or without sFLC-PD (HR 1.28, 95% CI = 0.77–2.13, p 0.334). (Fig. 5A). However, the median overall survival (OS) from the first relapse was significantly better for patients with only sFLC-PD, compared to those with urine M-protein PD with or without sFLC-PD (HR 1.87, 95% CI = 1.07–3.27, p 0.026). (Fig. 5B), which may reflect the impact of earlier initiation of therapy, although it could also suggest differences in disease biology.

We evaluated the association between each sFLC-PD and paraprotein-PD at 3-time points before confirmation of PD and at the time of second-line therapy. The evaluation cutoff was defined as the point at which one or more biomarkers met the progression criteria before starting second-line treatment (Fig. 6). The median time between the first, second, and third detection of PD by any of the three biomarkers and the initiation of second line of therapy was 93, 60, and 42 days, respectively. In 34% (89/261) of patients with sFLC-PD, disease progression preceded electrophoretic progression with a median of 3 months, and all patients eventually had confirmed electrophoretic PD, except for two patients who were lost the follow-up. Serial measurement of serum FLC showed the earlier detection of relapse by sFLC compared to standard electrophoretic measurements.

*Time: The evaluation cutoff, when one or more of the biomarkers meet the progression criteria before starting the 2nd line of therapy (last cluster bars). **The median time between the first, second, and third detection of progressive disease and the start of the second line of therapy: {Time 1: 93 days, Time 2: 60 days, and Time 3: 42 days}. ***Percentage is calculated by the number of patients with criteria of progression/number of samples available at each time point. PD progression disease.

Discussion

This study highlights several important messages regarding the value of serial sFLC measurements in monitoring response and progression in MM, demonstrating a strong association, comparable response rates, and high concordance between sFLC and electrophoresis responses, which underscore sFLC as a reliable surrogate marker for monitoring treatment response. Serum FLC overall response (≥PR) was detected earlier than sPEP/uPEP response across all subgroups and strongly predicted overall electrophoretic responses after two cycles of induction, with a modest trend toward improved PFS. These findings suggest that serial sFLC measurements can support timely clinical decisions and provide optimal therapy adjustments in the early phase of treatment, leading to better outcomes.

We investigated whether serial sFLC measurements could replace 24-h urine electrophoresis for assessing light chain response. Although the IMWG recommends 24-h urine electrophoresis to monitor Bence Jones Protein (BJP) in MM patients with a measurable urine M-protein at baseline, this approach has limitations in both real-life practice and clinical trials [21]. Several studies have demonstrated the clinical benefit of serum FLC for monitoring monoclonal proteins [23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. Despite this evidence, current response criteria have not yet incorporated sFLC. This is mainly due to the insufficient correlation between urine and serum FLC levels, which is influenced by renal metabolism, making them non-interchangeable. This has undoubtedly been the primary determinant for requiring 24-h urine M-protein for response assessments. When monoclonal FLC production is low, such as in deep responses to therapy or early relapse, urine BJP may not accurately reflect tumor burden due to renal tubular reabsorption. In contrast, Freelite immunoassays can detect sFLC levels below 1 mg/L, providing significantly greater sensitivity than electrophoretic methods [24]. Additionally, collecting serial 24-h urine samples can be cumbersome and inconvenient, particularly for older and frail patients.

In the current study, we observed a significant association and comparable response rates between sFLC and urine electrophoretic responses during the induction and at the time of best response. With alternative cutoffs for urine M-protein response (≥90% reduction for VGPR-uPEP and 50%–90% for PR-uPEP), the study found a higher ORR based on uPEP and improved concordance with sFLC response trends. This finding suggests that the current IMWG urine criteria may underestimate early treatment response, while sFLC provides a more timely reflection of treatment dynamics. Our data revealed consistent and comparable median percentage changes and strong correlations between serial dFLC and 24-h urine M-protein, over time, with even higher correlation rates in LCCM. These findings support the idea that serial sFLC can replace 24-h urine protein electrophoresis as a measure of light chain response. Comparable PFS among patients achieving VGPR after four cycles of induction by all three biomarkers suggests that sFLC-VGPR could potentially replace the urine M-protein VGPR (<100 mg in 24-h urine) as part of the electrophoretic VGPR response criteria, currently required by the IMWG.

Dispenzieri et al. [23] reported in 399 MM patients that early sFLC responses predicted electrophoretic response but not survival outcomes, with poor correlation between sFLC and uPEP responses. The study was limited by the absence of novel therapies and single-time-point assessments. Dejoie et al. [24] compared sFLC and electrophoresis responses after two and four cycles of induction and transplantation in 25 light chains and 157 intact immunoglobulin MM (IIMM) patients. In contrast to our study, only 62% of the IIMM group had measurable sFLC, and one-third of the LCCM group had measurable uPEP at baseline. Despite poor correlation between sFLC and urine M-protein, they found that sFLC measurement is more sensitive than urine for detecting tumor activity. In another study by Dejoie et al. [25], serum involved FLC (iFLC) and uPEP measurements were compared in 113 LCMM patients. At diagnosis, iFLC was more sensitive, detecting measurable disease in 100% of patients, compared to 64% of patients detected by urine electrophoresis. This trend persisted after 1 and 3 cycles of treatment. Similar to our findings, using involved FLC instead of dFLC, Gran et al. [26] found that a ≥50% decrease in involved FLC predicted responses at least three months before sPEP. Bradwell et al. [16] evaluated responses in 224 LCMM and suggested that an sFLC provides a more accurate marker of complete remission than 24-h urine measurements, and urine assay could overestimate the response compared to sFLC.

In the context of disease progression, serial sFLC measurements provide significant advantages. However, the IMWG criteria state that for patients with a measurable serum or urine M-protein at baseline, progression cannot be defined by an increase in serum FLC alone. Our data showed that, at the time of second-line therapy, PD was predominantly identified based on sFLC (61%), compared to serum/urine electrophoresis. However, this percentage could be considerably higher if urine samples had been available from all. Half of these patients were classified as LCMM at the time of diagnosis. Almost all patients with PD by uPEP also had sFLC-PD. These findings suggest that monitoring response only based on uPEP could miss a substantial proportion of PD in LCCM, whereas sFLC appears to be more sensitive for detecting progression. Briolli et al. [28] conducted the largest study on free light chain escape, reporting an incidence of 10% among 520 patients with conventionally defined relapse. Similar to our research, nearly half of the patients with LC escape were missed by urine assessment. Tacchetti et al. [27] reported that in 150 MM patients treated with first-line bortezomib-based regimens, 20% had sFLC escape, which preceded conventional relapse by a median of 3.8 months.

One of the promising findings of our study was that patients with only sFLC-PD had similar PFS-2 compared to those with urine M-protein PD; however, they had significantly better median OS from the first relapse, confirming the evidence that earlier detection and treatment intervention of relapse lead to better outcomes. In a recent study, Taccehtti et al. [29] observed that in 339 Ig-MM patients treated with a first-line novel therapy, sFLC-PD negatively impacts overall survival (OS) after progression, compared to electrophoresis progression without FLC increase, suggesting more aggressive clinical features in patients with FLC escape. They showed a similar second time to progression for conventional methods and FLC escape patients. These findings support modifications to the IMWG criteria, which currently state that progression cannot be defined by increases in serum FLC alone in patients with measurable M-protein by sPEP and/or uPEP at baseline. Recently, Dejoie et al. [30] proposed modified response criteria, suggesting the incorporation of sFLC to replace 24-h urine collection for response assessment in all MM patients, presenting a new modified model aligned with the current IMWG criteria.

Our study has several limitations, including its retrospective design, heterogeneity in anti-myeloma therapies, and variability in treatment duration. To address this, we focused on the first response and progression. Additionally, comparisons among the three biomarkers were not consistently performed within the same patients. Furthermore, our findings for sFLC measurements are based on Freelite assays; differences in sensitivity and lack of standardization across other sFLC assays may impact the applicability and interpretation of these results. Finally, the presence of missing urine samples in this mature and well-established dataset remains a concern, even in referral centers.

To our knowledge, this is the largest study conducted to date that includes a substantial sample size, with simultaneous measurements of sFLC, serum M-protein, and 24-h urine M-protein, evaluating the benefits of serial FLC in monitoring MM with measurable disease at multiple time points, based on novel therapies.

In conclusion, our study highlights that serial serum FLC measurements provide independent and additional value in predicting treatment response and detecting disease progression in multiple myeloma patients with measurable electrophoresis disease, especially in the era of novel immunotherapies. The results showed a significant association and agreement between the sFLC response and standard electrophoretic response during the induction therapy. A similar response rate between sFLC and urine paraprotein confirms the current cutoffs used for response categories for sFLC. A strong correlation between sFLC and urine M-protein in both LCMM and serum-immunoglobulin MM during induction, with a parallel percentage reduction of monoclonal protein, suggests that sFLC can replace 24-h urine protein electrophoresis as a measure of light chain response. This study strongly supports the integration of serial sFLC measurements for monitoring response and progression in MM, even with electrophoretic measurable disease.

Data availability

De-identified data utilized for this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, Blade J, Merlini G, Mateos MV, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e538–548.

Palumbo A, Avet-Loiseau H, Oliva S, Lokhorst HM, Goldschmidt H, Rosinol L, et al. Revised international staging system for multiple myeloma: a report from International Myeloma Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2863–9.

Kumar S, Paiva B, Anderson KC, Durie B, Landgren O, Moreau P, et al. International Myeloma Working Group consensus criteria for response and minimal residual disease assessment in multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:e328–46.

Engelhardt M, Kortüm KM, Goldschmidt H, Merz M. Functional cure and long-term survival in multiple myeloma: how to challenge the previously impossible. Haematologica. 2024;109:2420–35.

Abdallah NH, Smith AN, Geyer S, Binder M, Greipp PT, Kapoor P, et al. Conditional survival in multiple myeloma and impact of prognostic factors over time. Blood Cancer J. 2023;13:78.

Facon T, Kumar SK, Plesner T, Orlowski RZ, Moreau P, Bahlis N, et al. Daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MAIA): overall survival results from a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:1582–96.

Sonneveld P, Dimopoulos MA, Boccadoro M, Quach H, Ho PJ, Beksac M, et al. Daratumumab, bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:301–13.

Facon T, Dimopoulos MA, Leleu XP, Beksac M, Pour L, Hájek R, et al. Isatuximab, bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2024;391:1597–609.

Lakshman A, Kumar SK. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cells, bispecific antibodies, and antibody-drug conjugates for multiple myeloma: an update. Am J Hematol. 2022;97:99–118.

Cohen AD, Raje N, Fowler JA, Mezzi K, Scott EC, Dhodapkar MV. How to train your T cells: overcoming immune dysfunction in multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:1541–54.

Chari A, Minnema MC, Berdeja JG, Oriol A, van de Donk NWCJ, Rodríguez-Otero P, et al. Talquetamab, a T-cell-redirecting GPRC5D bispecific antibody for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:2232–44.

Usmani SZ, Garfall AL, van de Donk NWCJ, Nahi H, San-Miguel JF, Oriol A, et al. Teclistamab, a B-cell maturation antigen × CD3 bispecific antibody, in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (MajesTEC-1): a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 1 study. Lancet. 2021;398:665–74.

Munshi NC, Anderson LD, Shah N, Madduri D, Berdeja J, Lonial S, et al. Idecabtagene vicleucel in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:705–16.

Berdeja JG, Madduri D, Usmani SZ, Jakubowiak A, Agha M, Cohen AD, et al. Ciltacabtagene autoleucel, a B-cell maturation antigen-directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (CARTITUDE-1): a phase 1b/2 open-label study. Lancet. 2021;398:314–24.

Bradwell AR, Carr-Smith HD, Mead GP, Tang LX, Showell PJ, Drayson MT, et al. Highly sensitive, automated immunoassay for immunoglobulin free light chains in serum and urine. Clin Chem. 2001;47:673–80.

Bradwell AR, Carr-Smith HD, Mead GP, Harvey TC, Drayson MT. Serum test for assessment of patients with Bence Jones myeloma. Lancet. 2003;361:489–91.

Mead GP, Carr-Smith HD, Drayson MT, Morgan GJ, Child JA, Bradwell AR. Serum free light chains for monitoring multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2004;126:348–54.

Hill PG, Forsyth JM, Rai B, Mayne S. Serum free light chains: an alternative to the urine Bence Jones proteins screening test for monoclonal gammopathies. Clin Chem. 2006;52:1743–8.

Dispenzieri A, Kyle R, Merlini G, Miguel JS, Ludwig H, Hajek R, et al. International Myeloma Working Group guidelines for serum-free light chain analysis in multiple myeloma and related disorders. Leukemia. 2009;23:215–24.

Katzmann JA, Kyle RA, Benson J, Larson DR, Snyder MR, Lust JA, et al. Screening panels for detection of monoclonal gammopathies. Clin Chem. 2009;55:1517–22.

Durie BGM, Harousseau JL, Miguel JS, Bladé J, Barlogie B, Anderson K, et al. International uniform response criteria for multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2006;20:1467–73.

Katzmann JA, Clark RJ, Abraham RS, Bryant S, Lymp JF, Bradwell AR, et al. Serum reference intervals and diagnostic ranges for free kappa and free lambda immunoglobulin light chains: relative sensitivity for detection of monoclonal light chains. Clin Chem. 2002;48:1437–44.

Dispenzieri A, Zhang L, Katzmann JA, Snyder M, Blood E, Degoey R, et al. Appraisal of immunoglobulin free light chain as a marker of response. Blood. 2008;111:4908–15.

Dejoie T, Attal M, Moreau P, Harousseau JL, Avet-Loiseau H. Comparison of serum free light chain and urine electrophoresis for the detection of the light chain component of monoclonal immunoglobulins in light chain and intact immunoglobulin multiple myeloma. Haematologica. 2016;101:356–62.

Dejoie T, Corre J, Caillon H, Hulin C, Perrot A, Caillot D, et al. Serum free light chains, not urine specimens, should be used to evaluate response in light-chain multiple myeloma. Blood. 2016;128:2941–8.

Gran C, Afram G, Liwing J, Verhoek A, Nahi H. Involved free light chain: an early independent predictor of response and progression in multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2021;62:2227–34.

Tacchetti P, Cavo M, Rocchi S, Pezzi A, Pantani L, Brioli A, et al. Prognostic impact of serial measurements of serum-free light chain assay throughout the course of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma treated with bortezomib-based regimens. Leuk Lymphoma. 2016;57:2058–64.

Brioli A, Giles H, Pawlyn C, Campbell JP, Kaiser MF, Melchor L, et al. Serum free immunoglobulin light chain evaluation as a marker of impact from intraclonal heterogeneity on myeloma outcome. Blood. 2014;123:3414–9.

Tacchetti P, Rocchi S, Zamagni E, Barbato S, Rizzello I, De Cicco G, et al. Role of serum-free light chain assay for defining response and progression in immunoglobulin secretory multiple myeloma. Am J Hematol. 2022;97:1607–15.

Dejoie T, Corre J, Caillon H, Moreau P, Attal M, Loiseau HA. Responses in multiple myeloma should be assigned according to serum, not urine, free light chain measurements. Leukemia. 2019;33:313–8.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the CRIS foundation (Cancer Research and Innovation, Spain), in collaboration with the Spanish Society of Hematology (SEHH). We gratefully acknowledge all authors for granting permission to access patient data at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, US.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EA and SK designed the study and directed the analysis; EA collected the data and clinical information; EA and SK performed the primary analysis and wrote the first draft; AD, FB, SH, MG, PK, WG, TK, DD, RW, NL, YL, EM, JC, MB, NA, LH, MH, AF, DM, RAK, SVR, made substantial contributions to provide the data and revisions; SK and AD critically revised the manuscript; SK gave final approval of the manuscript to be submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (IRB # 18-0011366). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Askari, E., Dispenzieri, A., Buadi, F.K. et al. Value of serum-free light chain measurements in response and progression assessment in multiple myeloma with monoclonal protein measurable by electrophoresis. Blood Cancer J. 15, 133 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01340-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01340-7