Abstract

Cell death mediated by executioner caspases is essential during organ development and for organismal homeostasis. The mechanistic role of activated executioner caspases in antibacterial defense during infections with intracellular bacteria, such as Listeria monocytogenes, remains elusive. Cell death upon intracellular bacterial infections is considered altruistic to deprive the pathogens of their protective niche. To establish infections in a human host, Listeria monocytogenes deploy virulence mediators, including membranolytic listeriolysin O (LLO) and the invasion associated protein p60 (Iap), allowing phagosomal escape, intracellular replication and cell-to-cell spread. Here, by means of chemical and genetical modifications, we show that the executioner caspases-3 and -7 efficiently inhibit growth of intracellular Listeria monocytogenes in host cells. Comprehensive proteomics revealed multiple caspase-3 substrates in the Listeria secretome, including LLO, Iap and various other proteins crucially involved in pathogen-host interactions. Listeria secreting caspase-uncleavable LLO or Iap gained significant growth advantage in epithelial cells. With that, we uncovered an underappreciated defense barrier and a non-canonical role of executioner caspases to degrade virulence mediators, thus impairing intracellular Listeria growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To survive in the host, pathogenic bacteria evolved multiple effectors that allow specific interactions with the host to form a protective niche. The virulence strategy of Listeria monocytogenes (Lm) is characterized by uptake even in non-phagocytic cells, such as epithelial cells and fibroblasts, a process that is mediated by a group of surface proteins, called internalins (Inl) [1]. After uptake, they avoid lethal lysosomal degradation by a phagosomal escape mechanism, which is promoted by their key virulence mediator, listeriolysin O (LLO) in cooperation with two distinct phospholipases C [2]. In the cytosol, Lm specifically interact with the actin cytoskeleton, mediated by the actin assembly-inducing protein (ActA) [3] and the invasion associated protein p60 (Iap) [4], to gain motility for cell-to-cell spread, a process that is again mediated by LLO [5]. By successfully doing so, Lm cause a life-threatening disease in humans, particularly in the immunocompromised and during pregnancy [6].

Immune proteases have been recognized to display crucial internal barrier function in antibacterial defense. Neutrophil effector proteases have been demonstrated to be critical for the elimination of gram+ and gram- bacteria in in vitro and in vivo models [7,8,9,10]. These proteases were demonstrated to target bacterial proteins related to virulence [11], including LLO [12]. Our work revealed that the lymphocytic effector proteases, the granzymes, target bacterial proteins to inhibit their growth [13], including virulence mediators [14].

The induction of programed host cell death, particularly its lytic forms, necroptosis and pyroptosis, is widely recognized to act as an innate antibacterial defense barrier [15]. Less defined in antibacterial defense is the role of apoptosis [16], which is the immunologically silent, non-lytic form of programmed cell death, characterized by DNA fragmentation, chromatin condensation, membrane blebbing and cytoskeletal breakdown. This process relies on an intracellular cascade of the caspases. Initiator caspases-8 and -9 are activated by extrinsic factors, such as death receptor activation by tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) [17], intrinsic mediators, such as mitochondrial cytochrome C release [18], or by the granzymes [19]. Upon initiation, the executioner caspases-3, -6 and -7 are activated and they then cleave vital substrates resulting in apoptosis [20]. Apoptosis in the context of bacterial infections is considered as altruistic death, depriving intracellular bacteria of their protected niche. In this study, we have asked specifically if activated executioner caspases engage in more direct interactions with intracellular bacteria to inhibit their growth.

Results

Executioner caspases activity is induced by Lm infection and inhibits their intracellular growth

To experimentally confirm executioner caspases activity upon infection, we infected HeLa cells with WT or LLO-deficient Lm (both strain 10403S) and monitored executioner caspases (DEVDase) activity using the chromogenic caspase-3 and -7 substrate, Ac-DEVD-pNA (Fig. 1A). We also infected HeLa cells with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, in which caspase-3 activation was already mechanistically explored [21]. WT Listeria and Salmonella but not LLO-deficient Lm led to significant DEVDase activity 5 h postinfection that further increased after 16 hours. The colorimetric data were confirmed by western blot analysis using antibodies against the cleaved forms of the initiator caspase-9 (p35), executioner caspase-7 (p18), and of Parp1 (p89), which results upon caspase-3 cleavage [22] (Fig. 1B), as well as of the cleaved form of caspase-3 (Fig. 1C). Infections with virulent Salmonella and Listeria increased the signal intensity of cleaved Parp1 (rather weak for Lm), activated caspase-9 and caspase-7 already after 5 h and displayed full activation (compared to staurosporine, STS) after 16 hours. The LLO-deficient Listeria strain did not induce caspase-9 activity or Parp1 cleavage after 16 h, suggesting that it needs LLO for efficient caspase activation. Caspase activation was strongly reduced using the caspases-3 and -7 inhibitor DEVD-fmk or with pan-caspase inhibitor zVAD treatment indicating specificity of the detection. Caspase-3 activation (p17 fragment) upon virulent Lm infection alone was less efficient, only resulting in weak signal of cleaved caspase-3 after 16 h (Fig. 1C). As the death receptor ligand TNF-α is known to induce caspase-mediated apoptosis in intrinsically stressed HeLa cells, e.g. by protein synthesis inhibition [23, 24], and mice lacking TNF-α quickly succumb to Lm infections [25], we infected HeLa cells with Lm in presence of TNF-α for 16 h and measured caspase activation by immunoblot. Indeed, treatment with TNF-α markedly increased the activation of caspase-9, -3 and -7 (Fig. 1D). As a possible explanation for this phenomenon, we found full caspase-8 activation only in conditions of Lm infection with TNF-α indicating intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic signals simultaneously present in these cells that drive downstream caspase activation (Fig. 1E).

A HeLa cells were treated with staurosporine (STS, 0.1 μg/ml) or infected with virulent Lm (WT, strain 10403S), listeriolysin O deficient Lm (ΔLLO) or Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (SL1344) at a MOI of 1 for 1 h before extracellular bacteria were removed by gentamicin treatment. After further culture, the cells were lysed at indicated time points before caspase activity in the lysates was assessed using the chromogenic dye DEVD-pNA. Averages +/− SEM of three independent experiments are shown. HeLa cells infected with indicated bacteria as above +/− DEVD (20 μM), zVAD (20 μM) or STS (0.1 μg/ml) treatment were lysed at the indicated time points and their lysates were assessed by western blot for cleaved caspases-9 and -7 (Cl. casp9 and casp7), as well as the caspase-3-cleavage fragment of Parp1 (cl. parp1, B) or cleaved caspase-3 (cl. casp3) after 16 h (C). α−tubulin served as loading control. HeLa cells were infected with Lm WT as above or left non-infected (non-inf) for 16 h +/− TNF-α (10 ng/ml) before measuring caspase-9, caspase-3 and caspase-7 cleavage (D), as well as activation of caspase 8 (E) by immunoblot. In all panels, representative blots of three independent experiments are shown. DEVDase activity (F), MTS metabolic activity (G) and LDH release (H) were assessed in HeLa cells infected as above for 16 h with Lm WT, Lm ΔLLO or in uninfected cells +/− TNF-α (10 ng/ml) +/− zVAD (20 μM) treatment. Average +/− SEM of three independent experiments is shown. I HeLa cells were infected with Lm WT as above +/− DEVD-fmk (20 μM), zVAD (20 μM) or TNF-α (10 ng/ml) treatment. At indicated times, cells were lysed, and Lm were enumerated by CFU assay. Average +/− SEM of three independent experiments is presented. Asterisks indicate significant differences to untreated controls. P-values are * < 0.05, ** < 0.01 and *** < 0.005.

Interestingly, despite significant DEVDase activity in Lm-infected HeLa cells that was further enhanced by TNF-α and abolished by zVAD (Fig. 1F), we found no significant decrease of MTS metabolization (Fig. 1G) or release of LDH from infected cells after 16 h (Fig. 1H). This contrasted with STS treatment, which lysed the cells completely after 16 h.

Most importantly, the inhibition of executioner caspase activity in Lm-infected HeLa cells with caspase-3/7 specific DEVD-fmk or pan-caspase inhibitor zVAD increased growth of intracellular Lm whereas the treatment with TNF-α reduced the bacterial burden as compared to untreated cells (Fig. 1I).

Lm infection in presence of TNF-α results in high cytoplasmic DEVDase activity without inducing host cell death

To assess morphological signs of cell death upon Lm infection in presence of the proapoptotic agent TNF-α, we used fluorescent DEVD to indicate active caspases by microscopy. Strikingly, around half of the cells displayed bright cytoplasmic DEVD staining after 7 h upon Lm infection and TNF-α treatment (Fig. 2A, D). However, the nuclear morphology and cytoskeleton organization of the infected cells did not display obvious apoptotic features, similar to negative control HeLa cells (Fig. 2B). This was in stark contrast to STS treatment, leading to nuclear caspase translocation [26], as well as chromatin condensation and actin cytoskeleton breakdown [27] (Fig. 2C, D).

HeLa cells were infected with Lm at a MOI of 1 in presence of TNF-a (A), left without any manipulations (B), or treated with STS (0.1 mg/ml) (C) for 7 h before staining the cells with FITC-DEVD-fmk for another hour. After fixation, the cells were counterstained with Hoechst and 647-phallodin, then analyzed by confocal microscopy. In all panels, bars are 20 μm. (D), DNA condensation, cytoplasmic and nuclear DEVDfitc was quantified by counting five visible fields (n ~ 50) in three independent experiments. Presented are average +/− SEM. Significant differences are indicated. P-values are * < 0.05, ** < 0.01 and *** < 0.005.

In addition, in Lm-infected cells treated with TNF-α, only a few cells bound the Cytodeath® M30 antibody detecting cleaved cytokeratin-18 in early apoptotic cells [28] (Fig. 3A, D) as compared to untreated control cells (Fig. 3B). Even in cells showing active Lm proliferation, cytokeratin-18 remained unaffected (arrow in Fig. 3A). This was again in sharp contrast to STS treatment where most of the cells stained positive for M30 (Fig. 3C, D).

HeLa cells were infected with green fluorescent Lm (white arrow) in presence of TNF-α (A), left untreated (B), or treated with STS (0.1 mg/ml) (C) for 7 h. After methanol fixation, cytokeratin-18 cleavage was assessed using the M30 Cytodeath® antibody and Hoechst counter staining by microscopic analysis. (D), M30 positive cells were quantified by counting five visible fields (n ~ 50) in three independent experiments. Depicted are representative images from three independent experiments. Presented are average +/− SEM. Significant differences are indicated. P-values are * < 0.05, ** < 0.01 and *** < 0.005.

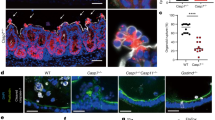

Host cells lacking executioner caspases are less resistant to bacterial infection

As the chemical inhibition of caspases is prone to off-target effects, executioner caspases were deleted in HeLa cells using CRISPR/Cas9 technology. For this purpose, HeLa cells (a commercial caspase-3 knockout (KO) and the corresponding parental line) were nucleofected with Cas9/guide RNA ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) directed to caspase-7 before cloning deletion lines by limited dilutions (Fig. 4A). First, the engineered lines were assessed for their levels of DEVDase activity in response to STS (Fig. 4B). While there was a clear (yet not significant) reduction in DEVDase activity in the single KO lines, DEVDase activity decreased in the CASP3−/− and CASP7−/− HeLa line as compared to the parental cells. This pattern was also displayed upon infection with Lm, where again caspase activity was only statistically significantly reduced in CASP3−/− and CASP7−/− cells; this was particularly obvious in host cells that were simultaneously treated with TNF-α (Fig. 4C). To evaluate the change DEVDase activity in CASP3−/− or CASP7−/− cells, we assessed intracellular Lm growth with and without TNF-α treatment. In these experiments, CFUs were calculated from bacterial growth curves as illustrated in the supplementary Figures S1. While TNF-α significantly reduced the bacterial burden in the parental HeLa line (WT), bacterial growth was not significantly affected by TNF-α in caspase deleted host cells (Fig. 4D). Only CASP3−/− and CASP7−/− HeLa cells were significantly less resistant to intracellular Lm growth than the parental line in absence of TNF-α (Fig. 4E). Of note, though executioner activity in HeLa cells was highly increased upon gram- Salmonella infections (Fig. 1A), their growth in CASP3−/− and CASP7−/− cells was not significantly affected (data not shown), suggesting strain specificity of this caspase-mediated defense mechanism in epithelial cells. To study the impact of the host cell type, we additionally aimed to delete caspase-3 and -7 in the monocyte-like human cell line THP-1. While the depletion of caspase-7 was complete, a weak band in the caspase-3 immunoblot still appeared after multiple rounds of nucleofection and limited dilution cloning (Fig. 4F) that was also reflected by the largely unchanged DEVDase activity upon Lm infection in this line (Fig. 4G). In contrast to HeLa cells, simultaneous TNF-α treatment did not alter DEVDase activity neither in the WT cells nor the KO lines. As the depletion of caspase-3 in THP-1 cells was obviously incomplete, we only tested the CASP7−/− THP-1 cells for intracellular bacteria growth. Indeed, we found a significantly increased bacterial burden in, Lm- (Fig. 4H) and surprisingly also Salmonella-infected CASP7−/− THP-1 cells (Fig. 4I), that was again not affected by simultaneous TNF-α treatment.

Parental HeLa or commercial caspase-3 KO (C3) cells (Abcam) were nucleofected with Cas9/guide RNA ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) targeting caspase-7 before enriching for deletion lines by limited dilutions. Knockout was confirmed by immunoblot using anti caspase-3, caspase-7 and α-tubulin antibodies (A). B caspase-deficient or parental HeLa lines were treated with staurosporine (STS) for 7 h before lysis and measuring DEVDase activity using DEVD-pNA. Indicated HeLa lines were infected with WT Listeria at MOI 0.1 for 16 h +/− TNF-α before the cells were lysed and DEVDase activity was measured (C), and CFU were calculated from bacterial growth curves (D and E), as shown in Figure S1. Averages +/− SEM of three independent experiments are shown. THP-1 cells were nucleofected with Cas9/guide RNPs targeting caspase-3 or -7 before cloning by limited dilutions and assessment by western blot (F). Cells of indicated genotype were infected with Lm at the MOI of 0.1 for 16 h +/− TNF-α, then the cells were lysed and DEVDase activity was assessed using fluorescent DEVD-fmk (G), and CFU were determined as above (H). WT and caspase-7 KO THP-1 cells were additionally infected with SL1344 at a MOI of 0.001 + /- TNF-α for 16 h before intracellular CFU were calculated from growth curves as shown in Figure S1G (I). Averages +/− SEM of three independent experiments are shown and significant differences between groups are indicated by asterisks. P-values are * < 0.05, ** < 0.01 and *** < 0.005.

Caspase-3 degrades Listeria supernatant proteins involved in pathogen-host interactions

We next studied if the proteolytic activity of executioner caspases – and with that, bacterial substrate degradation – might contribute to bacterial growth inhibition. Caspase accessibility was hypothesized to favor degradation of bacterial proteins that are released into the cytoplasm. Therefore, we performed unbiased proteomics approaches to identify caspase-3 substrates in cell-free Lm supernatants. Comparative 2-dimensional (2D) SDS-PAGE identified 29 proteins whose intensities changed by at least a factor 2 upon caspase-3 treatment in three replicate analyses (Fig. 5A). To backup these findings using an alternative approach, we additionally analyzed the caspase-3 degradome in Lm supernatants by terminal amine isotopic labeling of substrates (TAILS) [29]. TAILS analysis revealed 88 supernatant proteins that were detected as cleaved in three independent replicate samples (Fig. 5B). To our surprise, the overlap of the two analyses was only partial (9 proteins, Fig. 5C), presumably due to major differences in the sensitivities of the assays. All substrates of the two approaches and the potential cleavage sites according to the TAILS analysis are listed in Table 1. The 9 overlapping proteins are at the top of the list, including the well-established Lm virulence factors listeriolysin O (LLO) [5] and the broad range phospholipase C (PlcB) [30], essential for cell-to-cell spread. As the substrate selection criteria in the two approaches were highly stringent (found in 3 replicate samples), we run the bioinformatics analyses with the pooled substrate list of 108 proteins. We first screened the substrate list for pathways that are significantly enriched according to their false discovery rate (FDR) and ordered them by fold enrichment (Fig. 5D). The top enriched pathways include ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter complexes, PrfA-dependent virulence factors and peptidoglycan hydrolases, all essential for full virulence in vivo [31,32,33]. A pathway network analysis revealed a high interconnectivity between the enriched pathways (Fig. 5E), clearly indicating targeted substrate selection by caspase-3. Gene Oncology (GO) analysis of the cellular components showed, as expected, the extracellular region to be at the top of the list (Fig. 5F). However, the enrichment of membrane proteins and cytoplasmic proteins in a proteomics analysis of cell-free bacterial supernatant was unexpected. This was also indicated in the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis by the STRING software with most proteins being neither extracellular nor periplasmic (Figure S2) [34]. The PPI analysis though with an enrichment p-value of 1.08e-12 proofed to be highly significant, contracting a random set of proteins.

Cell-free Lm supernatants were treated with purified caspase-3 before analysis by comparative 2D SDS-PAGE (A), analyzed spots are indicated on the non-treated gel or by TAILS degradomics (B), Venn Diagram. The overlap in proteins is depicted in (C). All proteins are listed in Table 1 and the protein network analysis is indicated in Figure S2. Gene ontology analysis using ShinyGO 0.80 software revealed several significantly enriched pathways (D) that demonstrated to be highly interconnected (E). Two pathways (green nodes) are considered connected if they share at least 20% genes. Darker nodes represent more significantly enriched gene sets and bigger nodes are larger gene sets. Thicker edges indicate more overlapped genes. (F) Gene ontology analysis indicates significant enrichment in cellular component. Dashed line shows the FDR cut-off p-value of 0.05. Caspase-3-mediated degradation (caspase-3/Lm protein weight ratios from 1/1 to 1/100 for 4 h) of LLO in Lm supernatant was confirmed by western blot (G), and of purified GST-tagged LLO and Iap by Coomassie stained SDS-PAGE (H). Full-length protein, cleavage fragments and caspase-3 are indicated by arrow heads.

For the virulence mediators LLO and the invasion associated protein p60 (Iap), an extracellular endopeptidase [4], the proteomics data were experimentally validated. Caspase-3 efficiently and dose-dependently cleaved LLO in Lm supernatants (Fig. 5G), as well as LLO and Iap as purified proteins (Fig. 5H). The detected cleavage fragments of LLO (c-term 52 kDa) and Iap (c-term 45.1 kDa) correspond to the top score sites according to SitePrediction [35] (Figure S3A), as well as to ScreenCap3 [36].

The detection of secreted Lm proteins in infected host cells is highly challenging as miniscule amounts of bacterial proteins are mixed with overwhelming amounts of host proteins. However, we were able to detect a band in the lysates of Lm infected HeLa cells that corresponds in size to the 13 kDa cleavage fragment of LLO mediated by caspase-7 (Figure S3B). This band is suppressed by DEVD-fmk and induced by TNF-α. However, as this is the only indication for intracellular Lm protein cleavage by caspase-3 at this point, and the blots needed to be overexposed to saturation (demonstrating various unspecific bands) to detect the potential cleavage fragment, we added this finding to the supplementary information. Further study is needed for firm conclusions.

Caspase-uncleavable LLO or Iap mutants render Lm more virulent in HeLa cells

To test if executioner caspase-mediated degradation of LLO directly affects intracellular bacteria growth, we generated a Listeria line that secretes caspases-3 and -7-uncleavable, recombinant LLO in ΔLLO Lm. Cleavage SitePrediction software (and our caspase-3 TAILS proteomics data, see Table 1) predicted top score sites at the aspartate positions D62 (caspase-3) and D416 (caspase-7) in the LLO sequence (Figure S3A).

Comparison with the LLO structure revealed that these sites are well accessible as potential protease targets [37] (Figure S3C). Therefore, we replaced these potential cleavage site aspartates with glutamates and integrated the mutated LLO into the chromosome of ΔLLO Lm to generate LmLLOc3/7 (Fig. 6A). The treatment of supernatants from LmLLOwt and LmLLOc3/7 with caspases-3 or -7 confirmed protection of the mutated protein (Fig. 6B). As the D62 to E point mutation is within the PEST domain critical for activity [38], we tested the hemolytic activity in the supernatants. The activity of the mutated LLO was indeed significantly decreased (Fig. 6C). However, contrary to the LLOwt supernatants, neither caspase-3 nor caspase-7 affected the hemolytic activity of LLOc3/7 (Fig. 6D). Due to this difference in the hemolytic activities, we could not directly compare the virulent growth of these two lines in host cells. To circumvent this difficulty, we compared the growth upon treatment with zVAD where all caspase activity is blocked (Fig. 6E). Indeed, in the LLOc3/7 mutant strain, the time differences to the zVAD controls in untreated and particularly in TNF-α treated conditions were significantly reduced as compared to LLOwt Lm, indicating a growth advantage mediated by caspase-uncleavable LLO (Fig. 6F). As Iap is highly expressed in Lm supernatants and efficiently cleaved by caspase-3 (Fig. 5H), but not caspase-7 (not shown), we additionally mutated the cleavage site aspartate D48 (to glutamate) in Iap to generate a caspase-3-uncleavable mutant (Fig. 6G). This mutant was hemolytic unimpaired (not shown) and the mutation is far away from the c-terminal catalytic domain NlpC/P60 [39], allowing direct comparison of the wild type and the mutant line. Growth assays in HeLa cells revealed a significant growth advantage of the mutant compared to wild-type Lm, which was again amplified by the presence of TNF-α (Fig. 6H). Overall, these findings directly link the caspase-mediated degradation of virulence mediators to intracellular Lm growth.

Culture supernatants of ΔLLO Lm, transfected with indicated pIMK2-LLO constructs (A), were treated with caspase-3 or caspase-7 for 4 h (B). Secretion and caspase-mediated cleavage of LLO were assessed by immunoblots. Detection of Iap served as loading control in (A). C Human red blood cells were treated with serial dilutions (C) or caspase-treated (D) Lm supernatants containing LLOwt or LLOc3/7 for 15 min at 37 °C. Hemoglobin release was measured spectrophotometrically at 405 nm wavelength and average +/− SEM of three independent experiments is presented. E HeLa cells were infected with indicated Lm mutants +/− zVAD +/− TNF-α treatment before the intracellular bacterial load was assessed by growth curves assay. Arrows indicate the differences in delay times to the zVAD controls to reach the threshold OD of 0.1 that is plotted in (F). Average +/− SEM of the delay time normalized to zVAD controls in three independent experiments is shown. G Lm culture supernatants of lines secreting caspase-3-uncleavable (IAPc3) or wild-type Iap (IAPwt) were treated with caspase-3 for 4 h and cleavage of Iap was assessed by immunoblot. H HeLa cells were infected with indicated Lm mutants +/− TNF-α before the intracellular CFU were calculated from growth curves. Average +/− SEM of three independent experiments is shown. Significant differences between indicated groups are marked by asterisks. P-values are * < 0.05, **< 0.01 and ***< 0.005.

Discussion

In this study, we present compelling evidence for an underappreciated host defense mechanism against intracellular Lm that is mediated by executioner caspases-3 and -7. Executioner caspase activity is robustly activated in HeLa cells upon infection with virulent Lm, presumably via the intrinsic pathway and the activation of caspase-9. By engaging the extrinsic pathway and triggering caspase-8 activation, downstream caspase activity can be significantly enhanced by simultaneous TNF-α treatment. It was reported earlier that Lm infection triggers nucleosomal DNA fragmentation in mouse hepatocytes [40], presumably mediated by caspase-3 [41]. Caspase-7 activation upon Lm infection in murine macrophage was demonstrated to exert a cytoprotective effect on the host cells [42]. In this study, caspase activation was shown to not require caspase-1 or key innate signaling molecules, such as ASC, RIP2 or MyD88. However, how exactly Lm infections trigger executioner caspase activity remains elusive.

Though remarkably high cytoplasmic caspase-3 and/or -7 activity was recorded in HeLa cells upon Lm infection, particularly in presence of TNF-α, the cells stayed viable according to nuclear morphology, cytoskeleton organization, plasma membrane integrity and mitochondrial metabolization rate, at least at the low multiplicities of infection (MOI ≤ 1) used in this study. At this point, we can only speculate why activated executioner caspases upon Lm infections (and caspase-9 activation) did not translocate into the nucleus to further proceed with the host cell death program by degrading nuclear substrates [26]. The executioner caspases may be sequestered in the cytosol by the increased supply of protein substrates secreted from Lm, as suggested by our identification of a 13 kDa LLO fragment, presumably provided by caspase-7 proteolytic activity in the cytosol of infected host cells. However, at higher MOI ≥ 10, infected HeLa cells die rapidly, demonstrating signs of multiple death programs as this was recently observed and named PANoptosis [43], potentially indicating that at higher infection doses this cellular immune defense mechanism might be overwhelmed and additional inflammatory programs are need to fight the infection.

More importantly, we additionally demonstrate that the chemical inhibition of DEVDase activity or the genetic depletion of both caspases-3 and -7 decreases the resistance of HeLa cells against intracellular Lm. Surprisingly, caspase depletion did not affect resistance to Salmonella Typhimurium that highly induces executioner caspase activity, and crucial virulence effectors (SipA, SifA) are degraded by active caspase-3 [21, 44]. However, in contrast to Lm, effector cleavage might be even beneficial for the dissemination of Salmonella, suggesting major species-specific differences in caspase-mediated anti-bacterial defense [21]. The beneficial caspase-3 cleavage of SipA for the dissemination of Salmonella was explored predominantly in an experimental in vivo model, highlighting the need of more comprehensive in vivo studies to define the role of executioner caspases in antibacterial immunity.

Interestingly, in the monocytic acute leukemia line, THP-1, the single knock-out of caspase-7 led to increased intracellular bacteria growth of both Lm and Salmonella. Caspase-7, though structurally closely related to caspase-3, has a dual role in cell death and inflammation. Unlike caspase-3, it is activated by inflammatory processes, including active caspase-1 [45]. Active caspase-7, independently of caspase-1, was detected upon Lm infection [42], as well as during intracellular Salmonella and Legionella pneumophila infections, downstream of caspase-1 [46,47,48]. Remarkably, caspase-7-deficient mice allowed increased growth of L. pneumophila in their macrophages in vitro, and in their lungs in vivo [49]. Substantial replication of L. pneumophila was also observed in dendritic cells of caspase-3-deficient mice [50], suggesting that some gram- bacteria are also susceptible to executioner caspase activity. Using the unique model of gut specific caspase deletion, it was recently demonstrated that caspase-3 and -7 are required in intestinal epithelial cells to restrict Clostridium difficile infections [51], again highlighting the need for additional in vivo studies to clarify the role of executioner caspases during bacterial infections.

A crucial role of caspases-3 and -7 in immune defense against Lm was additionally demonstrated by the increased growth of a mutant strains that secretes caspase-uncleavable LLO or Iap in HeLa cells. Both LLO and Iap are also substrates of human granzyme B [14]. This overlap in substrate selection by granzyme B in general is not uncommon, as it shares cleavage specificity after aspartate residues with the caspases [52] and activates numerous caspases by direct cleavage, including caspase-3 [53] and caspase-7 [54]. To induce apoptosis, granzyme B can directly process numerous caspase substrates, such as Parp1, NuMA, DNA-PK or ICAD [55, 56].

Comprehensive proteomics analysis of caspase-3 substrates in the Lm secretome identified proteins critically involved in pathogen-host interactions and virulence. The top enriched pathways include membrane transport, in particular via the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter complex [57], the PrfA-dependent virulence factors LLO, ActA, PlcA and PlcB [58], peptidoglycan catabolic hydrolases, such as Iap, and proteins anchored to the outer surface via Gly-Trp (GW)-domains, including InlB [59], all pathways critical for full Lm virulence in a host. The pathways and the overall protein substrate network is remarkably interconnected with highly significantly enriched interactions, indicating a targeted attack of caspase-3 on proteins that are essential for pathogen-host interactions. The top subcellular localization was as expected the extracellular region. However, the screen revealed in addition a multitude of membrane and cytoplasmic proteins. A potential interpretation of the presence of these types of proteins in cell-free supernatants is provided by the comparison of the caspase-3 substrate list with a recent independent proteomics analysis of Lm membrane vesicles [60]. 93.1% of the caspase-3 substrates were also found with high confidence (in three replicate analyses) in highly purified membrane vesicles. To conclude how the release of membrane vesicles mediates Lm virulence and how the caspases interfere with it needs extensive further study.

In conclusion, this study identifies the executioner caspases-3 and -7 as a novel innate immune barrier against intracellular growing Lm. This barrier is established by the targeted degradation of a multitude of bacterial proteins that are critically involved in pathogen-host interactions, therefore inhibiting virulent growth.

Methods and Materials

Human cells and cell culture conditions

HeLa cells (Abcam, Mycoplasma free) were cultured in DMEM (Pan Biotech, P04-04510), supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Sigma) and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic solution (Thermo Fisher).

THP-1 cells (Sigma, Mycoplasma free) were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Pan Biotech, P04-18500), supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Sigma), 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic solution (Thermo Fisher).

Bacterial Strains

Listeria monocytogenes 10403S and 10403S ΔLLO, EGD-e and EGD-e ΔIap, and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium SL1344 used for infections were grown to mid-log in appropriate medium (Brain Heart Infusion (Millipore, 53286) + 50 μg/ml streptomycin for 10403S and 5 μg/ml erythromycin for EGD-e; Luria broth (Sigma, L3022) + 50 μg/ml streptomycin for Salmonella). 50 μg/ml kanamycin was added to grow mutant Listeria (pIMK2 transfected) [61]).

Gene modification by CRISPR/Cas9 methodology and clone selection limiting dilution

The gene editing was based on the nucleofection (4D Nucleofector System, Lonza) of preformed Cas9-guideRNA-ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes into target cell line (HeLa, THP-1) according to manufacturer’s recommendations (IDT). Three guides per gene were tested and the efficiency of knockdown was assessed by western blot. The cells that displayed most efficient knockdown (usually around 50%) were used for downstream dilution assays. HeLa cell gene edits were started using a commercial caspase-3 KO and the corresponding parental lines (abcam, ab255370, ab255448). Most efficient guide sequences were GATCGTTGTAGAAGTCTAAC for caspase-3 (in THP-1 cells) and GATATGTAGGCACTCGGTCC for caspase-7. Monoclonal cell populations were selected by seeding in an average of 0.5 cells in 100 μl in 96-well plates for 7 days before subcloning in repeated standard limiting dilution assays.

Generation of a caspase-uncleavable LLO and Iap mutant

Full-length (including the natural ribosome binding site and signal peptide) LLO and Iap were PCR amplified from the chromosome of Lm 10403S and EGD-e, respectively. The amplicons were cloned into the bacterial expression vector pGEX4Ti (Sigma) using the BamH1 and Xho1 restriction sites. Cleavage sites for caspases were predicted using the SitePrediction software [35] and experimentally validated. The validated top score cleavage site aspartic acids were mutated to glutamic acid by sequential two-step overlap PCRs [62]. Correct point mutations were confirmed by sequencing (Microsynth AG, Balgach, Switzerland). Wild-type and mutated genes were cloned into the integration vector pIMK2 [61] at the BamH1/Xho1 sites, electroporated into LLO- or Iap-deficient Lm (10403S and EGD-e, respectively). The mutants were selected on kanamycin BHI agar plates to generate the lines LmLLOwt and LmLLOc3/7, as well as LmIAPwt and LmIAPc3.

Hemolysis assays

Serial dilutions (10-80fold) of Lm culture supernatant were incubated with human red blood cells at a hematocrit of 0.4% in hemolysis buffer (100 mM NaCl, 40 mM NaPO4, 0.5 mg/ml BSA, pH=5.5) in u-bottomed microtiter plates at 37 °C for 15 min. After the incubation, the plate was spun (500 x g, 3 min) and the supernatant was transferred to a flat-bottomed microtiter plate. Hemolysis was assessed by absorbance readings at 405 nm in a plate reader (Synergy H1, Biotek). Specific hemolysis was normalized to positive control lysis induced by 0.1% Triton X-100, corrected by the spontaneous hemoglobin release in buffer only conditions. For some experiments, a 10fold dilutions of the Lm culture supernatants were pretreated with 2 U/μl of purified caspase-3 (see below) or commercial caspase-7 (Enzo Life Sciences) for 4 h at 37 °C before the assessment of the hemolytic activity.

Bacterial infections, colony forming unit (CFU), growth assays, DEVDase activity assessment and caspase activation

Before infections, overnight cultures of bacteria were diluted 1:50 in fresh broth and grown to mid-log, then were washed with PBS and resuspended in infection medium (RPMI + 1% BSA + appropriate antibiotics as above). Cell density was estimated by OD600 spectrometry (OD600 = 0.1 corresponds to ~2 × 107 bacteria/ml) and confirmed by CFU assay.

HeLa and THP-1 cells were infected with Lm 10403S and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium SL1344 for 60 min at indicated multiplicity of infection (MOI) in 24-well plates in triplicates. The infected cells were washed throuroughly with PBS and then further incubated with gentamicin (25 μg/ml) in infection medium. For some experiments, particularly when using higher MOIs due to cytopathic effects and subsequent susceptibility to gentamicin, gentamicin treatment was only for 30 min, followed by further incubation in gentamicin-free infection medium that was exchanged every 4 h. In some experiments, 20 μM zVAD, 20 μM zDVED-fmk or 10 ng/ml TNF-α was added. At indicated times, samples were washed with PBS and then hypotonically lysed by adding ice-cold sterile water for 45 min on ice.

For CFU assays, lysates were serially diluted in broth and spread on LB-Agar plates containing the appropriate antibiotics. Colonies were enumerated after 24 h at 37 °C.

For the growth assays, lysates were 10fold diluted in flat-bottomed 96-well plates and the OD at wavelength 600 nm was measured every 15 min while discontinuous shaking in heat-controlled plate reader for 24 h at 37 °C (Synergy H1, BioTek).

For the colorimetric DEVDase activity measurement (only in HeLa cells), lysates were cleared by centrifugation, and the supernatants were 10fold diluted into caspase assay buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 0.3% NP-40, 1 mM DTT) containing 200 μM Ac-DEVD-pNA (Sigma). Cleavage was monitored colorimetrically at 405 nm after 4 h at 37 °C. Due to general lower DEVDase activity in THP-1 cells, DEVDase activity was measured fluorometrically. For this purpose, TF3-DEVD-FMK (Cell Meter™ Live Cell Caspase-3/7 Binding Assay Kit, AAT Bioquest) at 1:150 ratio was added to the cells 60 min before the experimental endpoint. Cells were washed twice for 3 min in Washing Buffer (Kit component B) before fluorescent intensity was monitored in the well area scanning mode at Ex/Em = 550/595 nm in the Synergy H1 plate reader.

Caspase activation in the lysates was directly detected by western blot using antibodies against active caspases-3, -7 and -9, and cleaved Parp1 (Cleaved Caspase Antibody Sampler Kit #9929, Cell Signaling), as well as against caspase-8 (Initiator Caspases Antibody Sampler Kit #12675, Cell Signaling) according to manufacturer’s recommendations.

Assessment of host cell viability by MTS assay, LDH release and microscopy

2 h before the experimental endpoint, MTS reagent (MTS Assays Kit, abcam) was added (1:10 ratio) to host cells (treated as above), the absorbance was then measured at 490 nm wavelength.

Cells were gently spun (300 x g, 3 min) before the supernatant was transferred into flat-bottomed 96-well plates for the assessment of LDH release (Cytotoxicity Detection kit, Roche) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. To some wells, Triton X-100 (Sigma) was added to a final concentration of 0.1% before the centrifugation to determine the maximal release.

For microscopy, HeLa cells were seeded in culture medium at a density of 105 cells in 200 μl on glass coverslips in 24-well plates overnight, and then infected and treated in infection medium with Listeria as above. 1 h before fixation, FITC-DEVD-fmk (abcam) was added to the cells to a final concentration of 60 μM. The cells were then fixed and washed twice with PBS before staining with phalloidin-AF647 (250 nM, ThermoFisher) and Hoechst (1 μg/ml, Sigma) for 30 min at room temperature in the dark.

Additionally, HeLa cells were infected and treated as above with Lm, prestained with 2 μM CFSE (Sigma) for 30 min on ice. To assess early cell death, infected cells were fixed in cold methanol (−20 °C) for 15 min, washed twice with PBS and then stained with the CytoDEATH M30 antibody (Roche) and Hoechst (1 μg/ml, Sigma) for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. After the primary antibody, cells were washed with PBS and then counterstained with anti-mouse IgG-AF594 (R&D Systems) for 30 min at room temperature.

As positive control to induce cell death in these experiments, some wells were treated with 0.1 μg/ml staurosporine (STS).

All stained cover slips were washed twice with PBS before mounting in Vectashield (Vectorlabs) and analysis by confocal microscopy (Leica SP5).

Caspase-3 purification

Recombinant, human caspase-3 was purified from E. coli as described [63, 64]. In brief, the pET21b-Caspase-3 plasmid (Addgene) was transformed into BL-21 E. coli. These cells were grown to a density of A600nm = 0.6–0.8 at 37 °C and 220 rpm in 500 ml of induction medium (20 g/l Tryptone, 10 g/l yeast extract, 5 g/l NaCl, 0.4% glucose, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM CaCl2) containing 0.1 mg/ml ampicillin. Isopropyl-1-thio-b-D-galactopyranoside (IPTG, 1 mM) was added, and the culture was shaken at 25 °C, 200 rpm for 3 h. Cells were pelleted (centrifugation 3000 x g for 12 min) and resuspended in 50 ml of His binding buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 20 mM imidazole, and 500 mM NaCl, pH 8.0) containing 0.1 mg/ml lysozyme and 0.1% Triton X-100. The cells are incubated for 40 min on ice and vortexed every 10 min. Then, the cells underwent three freeze-thaw cycles and a sonication to make the sample less viscous. After centrifugation (17’000 x g for 47 min at 4 °C), the supernatant was harvested and 50 ml of His binding buffer were added to dilute it. After filtration with a 0.22 µm filter, the supernatant was loaded onto a 5 ml HisTrap HP column (Cytiva, 17524801) equilibrated with His binding buffer. The purified caspase-3 protein was eluted from the column using a linear imidazole gradient (until 1 M imidazole). A sample of each fraction were used for a gel electrophoresis and Coomassie staining to select the fraction containing the caspase-3 protein. These fractions were mixed and concentrated using a 3 kDa MWCO Amicon filter (Millipore, UFC9003), and the buffer was changed by caspase-3 buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 0.1% CHAPS, 10 mM DTT, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA and 10% sucrose).

Assessment of caspase-3 substrate cleavage in the Lm secretome by comparative 2D SDS-PAGE and TAILS proteomics

Lm were grown to mid-log in 100 ml of BHI medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml streptomycin. Then, the bacteria were grown in 100 ml of RPMI-1640 medium (Pan Biotech, P04-18500) supplemented with 50 μg/ml streptomycin for 4 h at 37 °C at 180 rpm. The supernatant was harvested after centrifugation of the bacterial culture (4000 rpm for 15 min) and filtered with a 0.22 µm filter. The supernatant proteins were concentrated by ultrafiltration using a 3 kDa MWCO Amicon filter (Millipore, UFC9003), and the RPMI was exchanged by caspase-3 assay buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 0.1% CHAPS, 5 mM DTT, 2 mM EDTA). 50 µg of supernatant proteins were treated or not with caspase-3 (weight ratio caspase-3 to bacterial proteins 1/10) for 24 h at 37 °C and then precipitated by trichloroacetic acid precipitation. The samples were used either for 2D SDS-PAGE or TAILS proteomics assays.

For 2D SDS-PAGE, the precipitated proteins were resuspended into 300 µl of 2-D sample solution (7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% (w/v) CHAPS, 40 mM DTT, 0.2% (w/v) Bio-Lyte® ampholytes pH3-10) and passively loaded into a 17 cm immobilized pH gradient (IPG) strip pH3-10 for 16 h (Bio-rad, 1632007). The proteins were then separated according to their isoelectric pH by isoelectric focusing. Thereafter, the IPG strip was treated with 1% w/v dithiothreitol (DTT) and 4% w/v iodoacetamide (IAA) for reduction and alkylation of proteins respectively. The proteins were then separated according to their molecular weight by electrophoresis. For this, the strip was placed on the top of a 12% polyacrylamide gel and fixed with 0.5% agarose solution. The 2D SDS-PAGE experiments have been carried out with the Bio-rad materials according to the provided instructions. For the visualization of protein spots, the gel was first fixed and then stained in silver stain (Silver stain plus kit, Bio-Rad, 1610449). Pictures of the stained gels were taken with the Perfection V850 Pro scanner (Epson). The Delta2D (DECODON) software was used to analyze the gel pictures and select the spots to pick up for mass spectrometry (MS) analysis. Spots whose intensities changed by at least a factor 2 upon caspase-3 treatment in three replicate analyses were selected for MS analysis. Before MS analysis, each spot was destained and the proteins were digested by trypsin, extracted from the gel pieces, and cleaned up.

For the TAILS, a protocol adapted from Kleifeld et al. [29] was used. Briefly, the precipitated proteins were resuspended into 50 µl of TAILS buffer (2.5 M GuHCl, 250 mM HEPES, pH 7.8). The proteins were denaturated with 1 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP) for 1 h at 65 °C, and alkylated with 5 mM chloroacetamide (CAA) for 30 min at 65 °C. The N-termini were labelled with stable isotopes (TMTsixplex™ Isobaric Label Reagent Set, ThermoFisher, 90061) for 1 h at room temperature. The quench labelling reaction was then done with a final concentration of 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate (NH4HCO3), for 30 min at room temperature. The clean-up of samples was performed by the addition of ice-cold acetone (7 volumes) and methanol (1 volume), followed by the incubation of samples for 2 h at −80 °C. After centrifugation at 4’700 rpm for 20 min, the protein pellet was washed with 5 mL of ice-cold methanol and then resolubilized with 100 mM NaOH solution (as little as possible), followed by the addition of HEPES buffer, pH 7.8, to a final concentration of 100 mM. Trypsin (Promega, V5113) was added at a 1:100 ratio (enzyme/substrate), and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 18 h. Adjust the pH of the samples to pH 6-7 using 2 M HCl. Add fivefold excess (w/w) of hyperbranched polyglycerol-aldehydes (HPG-ALD) polymer (Flintbox) and 5 M NaBH3CN to a final concentration of 50 mM NaBH3CN and incubate at least 16 h at 37 °C. Thereafter, the polymer is separated from the unbounded peptides by ultrafiltration using a 30 kDa MWCO Amicon filter (Millipore, UFC5030). The TAILS samples were acidified to pH < 2 using 10% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and cleaned up. For this, the proteins were loaded onto a column made of C18 solid phase extraction (SPE) disks (Empore, 66883-u). The samples were washed twice with 0.1% formic acid, eluted with a solution of 80% acetonitrile, 0.1% TFA, and completely dried under vacuum.

Mass spectrometry analysis and data extraction

Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry/ Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) measurements were performed on a Q Exactive HF-X mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) coupled to an EASY-nLC 1000 nanoflow-HPLC (Thermo Scientific). Peptides were separated on a fused silica HPLC-column tip (75 µm inner diameter (New Objective), self-packed with ReproSil-Pur 120 C18-AQ, 1.9 µm particle size (Dr. Maisch GmbH) to a length of 20 cm) using a gradient of A (0.1% formic acid in H2O) and B (0.1% formic acid in 80% acetonitrile in H2O): samples were loaded with 0% B with a flow rate of 600 nL/min; peptides were separated by 5–30% B within 85 min with a flow rate of 250 nL/min. Spray voltage was set to 2.3 kV and the ion-transfer tube temperature to 250 °C; no sheath and auxiliary gas were used. The mass spectrometer was operated in the data-dependent mode; after each MS scan (mass range m/z = 370–1750; resolution: 120,000), a maximum of twelve MS/MS scans were performed using an isolation window of 1.6, a normalized collision energy of 28%, a target Automatic Gain Control of 1e5 and a resolution of 30,000. MS raw files were analyzed with the MaxQuant software [65], using the UniProt full-length Listeria monocytogenes proteome (UP000001288), additionally including common contaminants (e.g., keratin) and trypsin, as reference. Carbamidomethylcysteine was set as fixed modification and protein amino-terminal acetylation and oxidation of methionine were set as variable modifications. The MS/MS tolerance was set to 20 ppm and three missed cleavages were allowed using Trypsin/P as enzyme specificity. Peptide and protein false discovery rates (FDR), based on a forward-reverse database, were set to 0.01, minimum peptide length was set to 7, and minimum number of unique peptides for identification of proteins was set to one. The “match-between-run” option was used with a time window of 0.7 min. MS raw files of TAILS experiment were processed using Proteome Discoverer software (Thermo Scientific) following the protocol of Madzharova et al. [66].

Experimental validation of the proteomics data

Cleavage of native LLO was experimentally confirmed by treating cell free Lm culture supernatant (as above) with indicated concentrations of purified caspase-3 at 37 °C and analyzed by immunoblot using rabbit anti-LLO antibodies (Abcam).

In addition, LLO-GST and Iap-GST fusion proteins using the constructs, pGEX4Ti-LLO or pGEX4Ti-Iap, respectively, in E. coli BL21 were purified on a GST column (GSTtrap HP, GE Healthcare) following the manufacture’s recommendation. These fusion proteins were treated with indicated concentrations of caspase-3 for 4 h and analyzed on Coomassie stained SDS-PAGE.

Statistics

All experiments were performed in triplicates and were repeated at least three times independently. Data are presented as means ± SEM. Comparisons between the different groups with similar variance were performed with two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-tests (using Microsoft Excel). P-values of less than 0.05 were considered significant. For the growth experiments in Fig. 2C, D, G, H, significant differences refer to the measured raw data of lag times before calculation of CFUs.

Data availability

The proteomics dataset generated and analyzed during in this study is available in Table 1. All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. All materials are available under request to the corresponding author.

References

Bierne H, Sabet C, Personnic N, Cossart R. Internalins: a complex family of leucine-rich repeat-containing proteins in Listeria monocytogenes. Microbes Infect. 2007;9:1156–66.

Smith GA, Marquis H, Jones S, Johnston NC, Portnoy DA, Goldfine H. The two distinct phospholipases C of Listeria monocytogenes have overlapping roles in escape from a vacuole and cell-to-cell spread. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4231–7.

Pillich H, Puri M, Chakraborty T. ActA of and Its Manifold Activities as an Important Listerial Virulence Factor. Actin Cytoskeleton Bact Infect. 2017;399:113–32.

Pilgrim S, Kolb-Mäurer A, Gentschev I, Goebel W, Kuhn M. Deletion of the gene encoding p60 in leads to abnormal cell division and loss of actin-based motility. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3473–84.

Cossart P. Illuminating the landscape of host-pathogen interactions with the bacterium Listeria monocytogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:19484–91.

Ramaswamy V, Cresence VM, Rejitha JS, Lekshmi MU, Dharsana KS, Prasad SP, et al. Listeria-review of epidemiology and pathogenesis. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2007;40:4–13.

Korkmaz B, Moreau T, Gauthier F. Neutrophil elastase, proteinase 3 and cathepsin G: physicochemical properties, activity and physiopathological functions. Biochimie. 2008;90:227–42.

Hirche TO, Benabid R, Deslee G, Gangloff S, Achilefu S, Guenounou M, et al. Neutrophil elastase mediates innate host protection against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Immunol. 2008;181:4945–54.

Hahn I, Klaus A, Janze AK, Steinwede K, Ding N, Bohling J, et al. Cathepsin G and neutrophil elastase play critical and nonredundant roles in lung-protective immunity against Streptococcus pneumoniae in mice. Infect Immun. 2011;79:4893–901.

Steinwede K, Maus R, Bohling J, Voedisch S, Braun A, Ochs M, et al. Cathepsin G and neutrophil elastase contribute to lung-protective immunity against mycobacterial infections in mice. J Immunol. 2012;188:4476–87.

Weinrauch Y, Drujan D, Shapiro SD, Weiss J, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil elastase targets virulence factors of enterobacteria. Nature. 2002;417:91–94.

Arnett E, Vadia S, Nackerman CC, Oghumu S, Satoskar AR, McLeish KR, et al. The pore-forming toxin listeriolysin O is degraded by neutrophil metalloproteinase-8 and fails to mediate Listeria monocytogenes intracellular survival in neutrophils. J Immunol. 2013;192:234–44.

Walch M, Dotiwala F, Mulik S, Thiery J, Kirchhausen T, Clayberger C, et al. Cytotoxic cells kill intracellular bacteria through granulysin-mediated delivery of granzymes. Cell. 2014;157:1309–23.

López León D, Matthey P, Fellay I, Blanchard M, Martinvalet D, Mantel PY. et al. Granzyme B attenuates bacterial virulence by targeting secreted factors. Iscience. 2020;23(3):100932.

Jorgensen I, Rayamajhi M, Miao EA. Programmed cell death as a defence against infection. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:151–64.

Behar SM, Briken V. Apoptosis inhibition by intracellular bacteria and its consequence on host immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2019;60:103–10.

Wajant H, Pfizenmaier K, Scheurich P. Tumor necrosis factor signaling. Cell death Differ. 2003;10:45–65.

Garrido C, Galluzzi L, Brunet M, Puig PE, Didelot C, Kroemer G. Mechanisms of cytochrome c release from mitochondria. Cell death Differ. 2006;13:1423–33.

Chowdhury D, Lieberman J. Death by a thousand cuts: granzyme pathways of programmed cell death. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:389–420.

Lawen A. Apoptosis - an introduction. Bioessays. 2003;25:888–96.

Srikanth CV, Wall DM, Maldonado-Contreras A, Shi H, Zhou D, Demma Z, et al. Salmonella pathogenesis and processing of secreted effectors by caspase-3. Science. 2010;330:390–3.

Boulares AH, Yakovlev AG, Ivanova V, Stoica BA, Wang GP, Iyer S, et al. Role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage in apoptosis - Caspase 3-resistant PARP mutant increases rates of apoptosis in transfected cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22932–40.

Miura M, Friedlander RM, Yuan JY. Tumor Necrosis Factor-Induced Apoptosis Is Mediated by a Crma-Sensitive Cell-Death Pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8318–22.

Sidoti-de Fraisse C, Rincheval V, Risler Y, Mignotte B, Vayssiére JL. TNF-α activates at least two apoptotic signaling cascades. Oncogene. 1998;17:1639–51.

Pfeffer K, Matsuyama T, Kundig TM, Wakeham A, Kishihara K, Shahinian A, et al. Mice deficient for the 55 kd tumor necrosis factor receptor are resistant to endotoxic shock, yet succumb to L. monocytogenes infection. Cell. 1993;73:457–67.

Faleiro L, Lazebnik Y. Caspases disrupt the nuclear-cytoplasmic barrier. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:951–9.

White SR, Williams P, Wojcik KR, Sun S, Hiemstra PS, Rabe KF, et al. Initiation of apoptosis by actin cytoskeletal derangement in human airway epithelial cells. Am J Respiratory Cell Mol Biol. 2001;24:282–94.

Caulin C, Salvesen GS, Oshima RG. Caspase cleavage of keratin 18 and reorganization of intermediate filaments during epithelial cell apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:1379–94.

Kleifeld O, Doucet A, Prudova A, Keller UAD, Gioia M, Kizhakkedathu JN, et al. Identifying and quantifying proteolytic events and the natural N terminome by terminal amine isotopic labeling of substrates. Nat Protoc. 2011;6:1578–611.

Petrisic N, Adamek M, Kezar A, Hocevar SB, Zagar E, Anderluh G. et al. Structural basis for the unique molecular properties of broad-range phospholipase C from Listeria monocytogenes. Nat Commun. 2023;14:6474.

Tanaka KJ, Song S, Mason K, Pinkett HW. Selective substrate uptake: The role of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) importers in pathogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 2018;1860:868–77.

de las Heras A, Cain RJ, Bielecka MK, Vazquez-Boland JA. Regulation of Listeria virulence: PrfA master and commander. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2011;14:118–27.

Vermassen A, Leroy S, Talon R, Provot C, Popowska M, Desvaux M. Cell Wall Hydrolases in Bacteria: Insight on the Diversity of Cell Wall Amidases, Glycosidases and Peptidases Toward Peptidoglycan. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:331.

Szklarczyk D, Kirsch R, Koutrouli M, Nastou K, Mehryary F, Hachilif R, et al. The STRING database in 2023: protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic acids Res. 2023;51:D638–D646.

Verspurten J, Gevaert K, Declercq W, Vandenabeele P. SitePredicting the cleavage of proteinase substrates. Trends Biochemical Sci. 2009;34:319–23.

Fu SC, Imai K, Sawasaki T, Tomii K. ScreenCap3: Improving prediction of caspase-3 cleavage sites using experimentally verified noncleavage sites. Proteomics. 2014;14:2042–6.

Koster S, van Pee K, Hudel M, Leustik M, Rhinow D, Kuhlbrandt W. et al. Crystal structure of listeriolysin O reveals molecular details of oligomerization and pore formation. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3690.

Decatur AL, Portnoy DA. A PEST-like sequence in listeriolysin O essential for pathogenicity. Science. 2000;290:992–5.

Yu MF, Zuo JR, Gu H, Guo ML, Yin YL. Domain function dissection and catalytic properties of p60 protein with bacteriolytic activity. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;99:10527–37.

Rogers HW, Callery MP, Deck B, Unanue ER. Listeria monocytogenes induces apoptosis of infected hepatocytes. J Immunol. 1996;156:679–84.

McDougal CE, Sauer JD. The impact of cell death on infection and immunity. Pathogens. 2018;7:8.

Cassidy SKB, Hagar JA, Kanneganti TD, Franchi L, Nunez G, O'Riordan MXD. Membrane damage during Listeria monocytogenes infection triggers a caspase-7 dependent cytoprotective response. PLoS Pathogens. 2012;8:e1002628.

Christgen S, Zheng M, Kesavardhana S, Karki R, Malireddi RKS, Banoth B, et al. Identification of the PANoptosome: a molecular platform triggering pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis (PANoptosis). Front Cell Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:237.

Patel S, Wall DM, Castillo A, McCormick BA. Caspase-3 cleavage of Salmonella type III secreted effector protein SifA is required for localization of functional domains and bacterial dissemination. Gut Microbes. 2019;10:172–87.

Lamkanfi M, Kanneganti TD. Caspase-7: A protease involved in apoptosis and inflammation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:21–24.

Lamkanfi M, Kanneganti TD, Van Damme P, Vanden Berghe T, Vanoverberghe I, Vandekerckhove J, et al. Targeted Peptidecentric Proteomics Reveals Caspase-7 as a Substrate of the Caspase-1 Inflammasomes. Mol Cell Proteom. 2008;7:2350–63.

Nozaki K, Maltez VI, Rayamajhi M, Tubbs AL, Mitchell JE, Lacey CA, et al. Caspase-7 activates ASM to repair gasdermin and perforin pores. Nature. 2022;606:960–7.

Goncalves AV, Margolis SR, Quirino GFS, Mascarenhas DPA, Rauch I, Nichols RD, et al. Gasdermin-D and Caspase-7 are the key Caspase-1/8 substrates downstream of the NAIP5/NLRC4 inflammasome required for restriction of Legionella pneumophila. PLoS Pathog. 2019;15:e1007886.

Akhter A, Gavrilin MA, Frantz L, Washington S, Ditty C, Limoli D. et al. Caspase-7 activation by the Nlrc4/Ipaf inflammasome restricts Legionella pneumophila infection. PLoS pathog. 2009;5:e1000361.

Nogueira CV, Lindsten T, Jamieson AM, Case CL, Shin S, Thompson CB. Rapid Pathogen-Induced Apoptosis: A Mechanism Used by Dendritic Cells to Limit Intracellular Replication of Legionella pneumophila. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000478.

Saavedra PHV, Huang LY, Ghazavi F, Kourula S, Vanden Berghe T, Takahashi N. et al. Apoptosis of intestinal epithelial cells restricts infection in a model of pseudomembranous colitis. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4846.

Poe M, Blake JT, Boulton DA, Gammon M, Sigal NH, Wu JK, et al. Human cytotoxic lymphocyte granzyme B. Its purification from granules and the characterization of substrate and inhibitor specificity. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:98–103.

Darmon AJ, Nicholson DW, Bleackley RC. Activation of the apoptotic protease CPP32 by cytotoxic T-cell-derived granzyme B. Nature. 1995;377:446–8.

Chinnaiyan AM, Hanna WL, Orth K, Duan H, Poirier GG, Froelich CJ, et al. Cytotoxic T-cell-derived granzyme B activates the apoptotic protease ICE-LAP3. Curr Biol: CB. 1996;6:897–9.

Andrade F, Roy S, Nicholson D, Thornberry N, Rosen A, Casciola-Rosen L. Granzyme B directly and efficiently cleaves several downstream caspase substrates: implications for CTL-induced apoptosis. Immunity. 1998;8:451–60.

Thomas DA, Du C, Xu M, Wang X, Ley TJ. DFF45/ICAD can be directly processed by granzyme B during the induction of apoptosis. Immunity. 2000;12:621–32.

Lewis VG, Ween MP, McDevitt CA. The role of ATP-binding cassette transporters in bacterial pathogenicity. Protoplasma. 2012;249:919–42.

Renzoni A, Cossart P, Dramsi S. PrfA, the transcriptional activator of virulence genes, is upregulated during interaction of with mammalian cells and in eukaryotic cell extracts. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:552–61.

Bierne H, Cossart P. InIB, a surface protein of that behaves as an invasin and a growth factor. J cell Sci. 2002;115:3357–67.

Coelho C, Brown L, Maryam M, Vij R, Smith DFQ, Burnet MC, et al. virulence factors, including listeriolysin O, are secreted in biologically active extracellular vesicles. J Biol Chem. 2019;294:1202–17.

Monk IR, Gahan CG, Hill C. Tools for functional postgenomic analysis of listeria monocytogenes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:3921–34.

Heckman KL, Pease LR. Gene splicing and mutagenesis by PCR-driven overlap extension. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:924–32.

Mittl PRE, DiMarco S, Krebs JF, Bai X, Karanewsky DS, Priestle JP, et al. Structure of recombinant human CPP32 in complex with the tetrapeptide Acetyl-Asp-Val-Ala-Asp fluoromethyl ketone. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6539–47.

Stennicke HR, Salvesen GS. Caspases: preparation and characterization. Methods. 1999;17:313–9.

Cox J, Mann M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1367–72.

Madzharova E, Sabino F, Auf dem Keller U. Exploring Extracellular Matrix Degradomes by TMT-TAILS N-Terminomics. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;1944:115–26.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Marianne Blanchard for excellent technical support, Dirk Bumann, Biozentrum, University of Basel, Switzerland, and Trinad Chakraborty, Justus-Liebig-University in Giessen, Germany, for providing Salmonella Typhimurium SL1344 and Listeria monocytogenes EGD-e ΔIap (p60), respectively. pIMK2 was a kind gift from Colin Hill, School of Microbiology, University College Cork, Ireland.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant # 310030_169928 to MW; 31003A_182729 to PYM), the Vontobel Foundation, Novartis Foundation for Medical-Biological Research, the Kurt and Senta Herrmann Foundation, and the Research Pool of the University of Fribourg (to MW).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MW conceived and conceptualized the study by providing the methodology and design of most assays. ML, RS, SDG, SB, MB, OA, TM, TS, LC, AF, PM, MS conducted the investigation. MW, ML, RS, MS, DK, and PYM analyzed the data. MW wrote the original draft of the manuscript. ML, RS, DK and PYM wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. MW supervised the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. As no human subjects or animals were used in this study, ethics approval was not necessary.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Edited by Hans-Uwe Simon

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lavergne, M., Schaerer, R., De Grandis, S. et al. Executioner caspases degrade essential mediators of pathogen-host interactions to inhibit growth of intracellular Listeria monocytogenes. Cell Death Dis 16, 55 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-025-07365-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-025-07365-x