Abstract

Ferroptosis has emerged as a potential therapeutic target in cancer. This study shows the critical role of AGR2 in ferroptosis suppression across pancreatic cancer cell lines and in vivo models. Notably, human pancreatic cancer cells exhibit dose-dependent AGR2 upregulation upon exposure to ferroptosis inducers. Genetic ablation of AGR2 significantly sensitizes cells to ferroptosis through a p53-mediated mechanism, while p53 knockdown effectively rescues ferroptosis resistance. Mechanistic investigations demonstrate that AGR2 deficiency activates p53 signaling, downregulating the iron exporter SLC40A1 (encoding ferroportin/FPN1), inducing intracellular iron overload and consequent ferroptosis. Clinically, we find a positive correlation between AGR2 and FPN1 expression in PDAC specimens, with co-elevation of both markers predicting unfavorable patient prognosis. Therapeutically, administration of an AGR2-targeting peptide synergizes with ferroptosis inducers, significantly enhancing cell death in PDAC models. Our findings not only elucidate a novel AGR2/p53/FPN1 regulatory axis in ferroptosis control but also propose innovative combination strategies for pancreatic cancer treatment.

Highlights

-

AGR2 is upregulated during ferroptosis in pancreatic cancer.

-

AGR2 is a negative regulator of ferroptosis in pancreatic cancer.

-

AGR2 inhibits ferroportin expression by modulating p53.

-

Ferroportin inhibited ferroptosis in pancreatic cancer.

-

Peptide treatment sensitized PDAC cells to ferroptosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) ranks among the most lethal malignancies, with a five-year survival rate below 10%, underscoring an urgent need to unravel the molecular drivers of its aggressiveness and therapeutic resistance [1]. While dysregulation of oncogenic and tumor-suppressive pathways, such as KRAS activation and TP53 inactivation, has been extensively studied, emerging players like Anterior Gradient 2 (AGR2) are gaining attention for their roles in shaping PDAC biology [2,3,4]. AGR2, a protein disulfide isomerase overexpressed in pancreatic cancer, is implicated in metastasis, chemoresistance, and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress adaptation [2, 3, 5,6,7,8]. However, the mechanisms by which AGR2 intersects with canonical tumor-suppressor networks, particularly p53, and influences cell death pathways remain poorly defined.

Recent advances have positioned ferroptosis as a therapeutic vulnerability in apoptosis-resistant cancers like PDAC [9, 10]. Central to ferroptosis regulation is cellular iron homeostasis, governed by iron transporters such as ferroportin (FPN1), the sole iron exporter [11,12,13]. Intriguingly, the tumor suppressor p53, beyond its canonical roles in cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, has been shown to modulate ferroptosis through transcriptional control of iron metabolism genes [14, 15]. Yet, how oncogenic factors like AGR2 interface with p53 to disrupt iron flux and ferroptosis sensitivity in PDAC is unknown, representing a critical gap in understanding the disease’s adaptive mechanisms.

This study identifies AGR2 as a novel regulator of the p53-ferroportin axis in pancreatic cancer. We demonstrate that AGR2 suppresses p53 activity, leading to the transcriptional downregulation of FPN and subsequent iron retention, which shields PDAC cells from ferroptosis. This AGR2-driven axis not only promotes tumor survival under stress but also correlates with poor patient outcomes and resistance to standard-of-care therapies. Our work reveals a previously unrecognized crosstalk between AGR2, p53, and iron metabolism, positioning AGR2 as a rheostat of ferroptosis susceptibility.

Results

AGR2 is upregulated during ferroptosis in pancreatic cancer

Our previous studies have proved the role of AGR2 in pancreatic carcinogenesis and progression [2]. Further analysis of sequencing data of the pancreas of KC verse KC;Agr2−/− mice (PRJEB40643) proved that ferroptosis might be involved in the pancreatic cancer progression (Fig. 1A). GSEA analysis presented that AGR2 knockout induced the enrichment of ferroptosis (Fig. 1B). Thus, we hypothesize that AGR2 might regulate pancreatic cancer progression by regulating ferroptosis. Firstly, we analyzed the relationship between cell death and mRNA expression of AGR2 in PDAC cell lines (HPAC and Capan2). Indeed, treatment with erastin or RSL3 induced cell death in a dose-dependent manner, and this effect was significantly attenuated by the ferroptosis-specific inhibitors liproxstatin-1 and ferrostatin-1 (Fig. 1C, D, Supplementary fig. 1A, B). Pharmacological inhibition of necroptosis (via necrosulfonamide [NSA]) and apoptosis (via Z-VAD-FMK) did not attenuate RSL3- or erastin-induced cell death in HPAC and Capan2 cell lines (Fig. 1C, D, Supplementary fig. 1A, B). Transcriptional profiling revealed erastin- and RSL3-mediated upregulation of AGR2 mRNA expression in these cells, a phenomenon suppressed by the ferroptosis inhibitors liproxstatin-1 and ferrostatin-1 but unaffected by Z-VAD-FMK or NSA (Fig. 1E, F, Supplementary fig. 1C, D). Subsequent western blot analysis corroborated these findings, demonstrating that liproxstatin-1 abolished erastin/RSL3-induced elevation of AGR2 protein levels (Fig. 1G, Supplementary fig. 1E). Consistent with established ferroptosis markers, treatment with erastin or RSL3 inhibited protein expression of the pro-ferroptotic enzyme acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4), glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), and solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11) expression (Fig. 1G, Supplementary fig. 1E). Furthermore, we check the expression of AGR2 on the tumor of KPC tissues, the immunoblot and immunohistochemistry showed the high expression of AGR2 in the tumor (Supplementary fig. 1F, G). These collective results implicate AGR2 is highly upregulated during ferroptosis.

A Heatmap showing the expression levels of ferroptosis-related genes in pancreatic tissues from KC and KC; Agr2−/− mice. B Gene set enrichment analysis indicating significant enrichment of ferroptosis-related genes in pancreatic cancer. C–F Quantitative analysis showed the cell death rate and the AGR2 mRNA expression of Capan2/ HPAC cells treated with different concentrations of Erastin (0–20 µM) or RSL3 (0–2 µM). G Protein expression levels of ACSL4, GPX4, SLC7A11, and AGR2 in HPAC and Capan2 cells treated with Erastin, RSL3, Lip-1. Data are presented as the mean of 3 independent experiments ± SEM. *P < 0.1, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

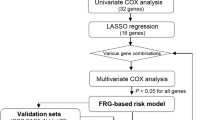

AGR2 is a negative regulator of ferroptosis in pancreatic cancer

As AGR2 was identified as an oncogene in cancers, we hypothesized that AGR2 might be a negative regulator of ferroptosis. AGR2 knockout (KO) cell lines were established (Fig. 2A, Supplementary fig. 2A). RNA sequencing and KEGG analysis show ferroptosis might be involved in the AGR2 KO cellular process (Fig. 2B, C). And the ferroptosis might associated with the p53 pathways. Indeed, AGR2 KO sensitized RSL3 or erastin-induced cell death in PDAC cells with wold-type p53 (p53wt) (HPAC and Capan2) (Fig. 2D); While for the PDAC cells with mutated p53 (p53mut) (PANC1, Miacapa2, and AsPC-1), While AGR2 KO alone did not induce increased cell death. And AGR2 KO did not sensitized RSL3 or erastin-induced cell death (Supplementary fig. 2B, C). Lipid peroxidation level, GSH/GSSG ratio, mRNA of prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTSG2) and MDA level were induced with AGR2 KO and were inhibited by Lip-1 in p53wt cells, but not in p53mut cells (Fig. 2E, Supplementary fig. 2D–G). To investigate the cytoprotective role of AGR2 in ferroptosis regulation, AGR2 KO combined with TBH treatment induced morphological hallmarks of ferroptosis, including cellular shrinkage and membrane disintegration, in pancreatic cancer cells (Fig. 2G). This result demonstrates that AGR2 functions as a negative regulator of ferroptosis in pancreatic malignancies and is associated with p53 status.

A Western blot analysis demonstrated expression of AGR2 protein in AGR2 knockout groups compared to control cells in Capan2, HPAC, and PANC1 cells; Quantification of AGR2 mRNA expression relative to GAPDH is shown beneath the blot. B Heatmap representation of dysregulated genes expression in AGR2 knockout groups compared to control cells of HPAC, Capan2, and PANC1 cells. C KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes in HPAC and Capan2 cells upon AGR2 knockout. D Quantitative analysis showed the cell death rate of Capan2 and HPAC cells with or without AGR2 knockout, treated with different concentrations of Erastin (0–20 µM) or RSL3 (0–20 µM). E BODIPYTM 581/591 C11 levels of Capan2 and HPAC cells with or without AGR2 knockout, treated with or without the Lip-1. F Quantification of BODIPY 581/591 C11 fluorescence in Capan2 and HPAC cells. G Representative bright-field images of HPAC and Capan2 cells treated with TBH to induce ferroptosis in control, AGR2 KO, and AGR2 KO + Lip1 groups. Scale bar, 250 µm. Data are presented as the mean of 3 independent experiments ± SEM. *P < 0.1, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

AGR2 KO inhibits the tumor development of orthotopic PDAC partly through ferroptosis

To evaluate the therapeutic synergy between ferroptosis induction and AGR2 ablation, we conducted assessments of IKE—a metabolically stabilized derivative of the ferroptosis inducer erastin—in orthotopic pancreatic cancer models. By in vivo results, AGR2 KO or IKE treatment significantly inhibited tumor growth, and the combination of AGR2 KO and IKE treatment significantly suppressed tumor growth (Fig. 3A–E). The MDA levels, the mRNA expression of PTGS2, lipid ROS levels, and HMGB1 protein level were also increased, all of which were inhibited by the ferroptosis inhibitor Lip-1 (Fig. 3F–M). And 4HNE and ki67 staining proved that AGR2 KO and IKE treatment induced ferroptosis and inhibited tumor proliferation, all of which were reversed by the ferroptosis inhibitor Lip-1 (Fig. 3N–S). These in vivo studies supported the hypothesis that AGR2 KO inhibits the tumor development of orthotopic PDAC partly through ferroptosis

A Gross appearance of the tumor in the con, IKE, IKE+Lip- 1, AGR2 KO, AGR2 KO + IKE, and AGR2 KO + IKE+Lip-1 groups of HPAC and Capan2 cells. B, C Tumor volume of mouse model in the con, IKE, IKE+Lip-1, AGR2 KO, AGR2 KO + IKE, and AGR2 KO + IKE+Lip-1 groups of HPAC and Capan2 cells. D, E Tumor weight of mouse model in the con, IKE, IKE+Lip-1, AGR2 KO, AGR2 KO + IKE, and AGR2 KO + IKE+Lip-1 groups of HPAC and Capan2 cells. F, G The bar chart shows the MDA levels of tumors in the con, IKE, IKE+Lip-1, AGR2 KO, AGR2 KO + IKE, and AGR2 KO + IKE+Lip-1 groups of HPAC and Capan2 cells. H, I The bar chart shows the mRNA expression of PTGS2 of tumors in the con, IKE, IKE+Lip-1, AGR2 KO, AGR2 KO + IKE, and AGR2 KO + IKE+Lip-1 groups of HPAC and Capan2 cells. J, K The bar chart shows the HMGB1 levels of tumors in the con, IKE, IKE+Lip-1, AGR2 KO, AGR2 KO + IKE, and AGR2 KO + IKE+Lip-1 groups of HPAC and Capan2 cells. L, M The bar chart shows the Lipid ROS levels of tumors in the con, IKE, IKE+Lip-1, AGR2 KO, AGR2 KO + IKE, and AGR2 KO + IKE+Lip-1 groups of HPAC and Capan2 cells. N–Q Bar charts show the number of 4-NHE and Ki67 cells of tumors in the con, IKE, IKE+Lip-1, AGR2 KO, AGR2 KO + IKE, and AGR2 KO + IKE+Lip-1 groups of HPAC and Capan2 cells. R, S Representative IHC staining of 4HNE and Ki67 of tumors in the con, IKE, IKE+Lip-1, AGR2 KO, AGR2 KO + IKE, and AGR2 KO + IKE+Lip-1 groups of HPAC and Capan2 cells. Scale bar = 100 µm. Data are presented as the mean of 3 independent experiments ± SEM. *P < 0.1, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

AGR2 acts as a p53 repressor to regulate ferroptosis

Then, we investigated the potential molecular mechanism of AGR2 in ferroptosis. Our study identified p53 as the downstream target of AGR2 [2]. And the KEGG analysis of RNA-sequencing data showed involvement of p53 in ferroptosis (Fig. 2C). Previous studies also identified the role of p53 in ferroptosis [16, 17]. Thus, we hypothesized that AGR2 regulates ferroptosis by p53 pathway. Then, p53 was knocked down (KD) in HPAC and Capan2 cell lines with siRNA (Fig. 4A). As expected, p53 KD rescued RSL3 or erastin-induced cell death in HPAC and Capan2 cells upon erastin or RSL3 treatment (Fig. 4B, C). Lipid peroxidation level, MDA level, PTGS2 mRNA level, and lipid ROS level were induced with AGR2 KO and were reversed by p53 KD (Fig. 4D–K). These results revealed that AGR2 acts as a p53 suppressor to regulate ferroptosis.

A Western blot analysis shows p53 and GAPDH expression in Con, AGR2 KO, AGR2 KO+sip53 group of HPAC and Capan2 cells. B, C Quantitative analysis showed the cell death rate of Capan2 and HPAC cells treated with different concentrations of Erastin (0–20 µM) or RSL3 (0–20 µM). D, E Bar charts show the GSH/GSSG ratios in the AGR2 KO, AGR2 KO+sip53 groups of HPAC and Capan2 cells. F, G Bar charts show the MDA levels in the AGR2 KO, AGR2 KO+sip53 group of HPAC and Capan2 cells. H, I Bar charts show the mRNA expression of PTGS2 in the AGR2 KO, AGR2 KO+sip53 groups of HPAC and Capan2 cells. J, K Bar charts show the lipid ROS levels in the AGR2 KO, AGR2 KO+sip53 groups of HPAC and Capan2 cells. Data are presented as the mean of 3 independent experiments ± SEM. *P < 0.1, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

AGR2 inhibits ferroportin expression by modulating p53

To elucidate potential mechanisms of the AGR2-p53 axis in regulating ferroptosis in pancreatic cancer models, we re-analyzed transcriptomic data of Capan2 KO cells. Dysregulated genes were investigated. Among these, we focused on SLC40A1 (encoding ferroportin, FPN1), a critical iron exporter (Fig. 5A). Genetic perturbation experiments demonstrated that AGR2 KO significantly suppressed FPN1 expression, while p53 KD effectively rescued FPN1 suppression (Fig. 5B). Pharmacological activation with Nutlin-3a (a p53 activator) confirmed the result, upregulated p53 expression inhibited FPN1 protein level, and this effect was reversed by concurrent P53 knockdown (Fig. 5C). Given that p53’s established role is as a transcription factor, we hypothesized that p53 directly transcriptional transcription of FPN1. Indeed, transcription prediction showed that p53 might bind to the promoter area of SLC40A1 genes (Fig. 5D). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays validated physical interaction between p53 and the SLC40A1 promoter region (Fig. 5D, E). Subsequent functional validation through dual-luciferase reporter assays demonstrated dose-dependent transcriptional repression of SLC40A1 by p53 (Fig. 5F). Furthermore, the pancreatic transgenic mouse model proved that AGR2 KO significantly induced p53 activation and downregulation of FPN1 (Supplementary fig. 3A–C). And the level of MDA, PTGS2 mRNA level, and HMGB1 level were also upregulated (Supplementary fig. 2D). These results confirmed that AGR2 inhibited FPN1 expression through p53.

A Venn diagram illustrating the overlap between P53 target genes and two datasets: Capan2 and HPAC. B Western blot shows the FPN1 expression in con, AGR2KO, and AGR2KO+sip53 groups of HPAC and Capan2 cells. C Western blot shows the p53 and FPN1 expression in con, Nutin, and Nutin+sip53 groups of HPAC and Capan2 cells. D Schematic representation of the SLC40A1 promoter region, showing the possible p53 binding site and primer positions. E ChIP-PCR analysis shows binding of p53 to the SLC40A1 promoter region in Capan2 cells. F Bar chart shows the ChIP-qPCR result of the percentage of input of p53 binding to the SLC40A1 promoter. G Luciferase reporter assays demonstrated p53-mediated activation of the SLC40A1 promoter in Capan2 cells transfected with pCAG-control or pCAG-p53-Flag plasmids. Data are presented as the mean of 3 independent experiments ± SEM. *P < 0.1, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Ferroportin inhibited ferroptosis in pancreatic cancer

Previous studies have identified the role of FPN1 in ferroptosis [18, 19], while it remains unclear in PDAC. Firstly, FPN1 was knocked down in HPAC and Capan2 cells (Fig. 6A). Further analysis proved that FPN1 KD significantly upregulated MDA levels, Fe2+(ferrous iron), mRNA expression of PTGS2, HMGB1, and lipid ROS, all of which were reversed by Lip-1 (Fig. 6B-G); In addition, the hepcidin (FPN1 inhibitor) was used. Intrusively, hepcidin significantly induced up-expression of MDA, Fe2+, PTGS2, HMGB1, Relative BODIPYTM 581/591 C11, and lipid ROS, all of which were down-regulated after Lip-1 treatment (Fig. 6H–M). We next investigated the function of FPN1 in vivo. Consistent with in vitro results, FPN1 KD or hepcidin treatment blocked tumor growth compared with the control group; this inhibitory effect was reversed by Lip-1 treatment (Fig. 6N–R). Moreover, the further immunohistochemistry staining of 4-HNE and Ki-67 of tumors supported our in vivo results (Fig. 6S–V, Supplementary fig. 4). These preclinical animal studies supported the hypothesis that FPN1 inhibited ferroptosis in pancreatic cancer.

A Western blots show the expression of FPN1, GAPDH in the control and FPN1 knockout group of Capan2 and HPAC cells. B–G Bar charts show the level of MDA, Ferrous iron, HMGB1, lipid ROS, BODIPYTM 581/591 C11 levels, and the mRNA expression of PTGS2 in control and FPN1 knockout and FPN1 knockout+Lip-1 groups of Capan2 and HPAC cells. H–M Bar charts show the level of MDA, Iron ion, HMGB1, lipid ROS, BODIPYTM 581/591 C11 levels, and the mRNA expression of PTGS2 in control and hepcidin and hepcidin+Lip-1 groups of Capan2 and HPAC cells. N Representative images of tumors from HPAC and Capan2 xenografts in mice under different treatment conditions. O, P Tumor weight of the tumor in the control, siFPN1, hepcidin, siFPN1+Lip-1, and siFPN1+Lip-1 groups of HPAC and Capan2 cells. Q, R Tumor volume of the tumor in the control, siFPN1, hepcidin, siFPN1+Lip-1, and siFPN1+Lip-1 groups of HPAC and Capan2 cells. S–V Bar charts show the number of 4-NHE and Ki67 cells of tumors in the control, siFPN1, hepcidin, siFPN1+Lip-1, and siFPN1+Lip-1 groups of HPAC and Capan2 cells.

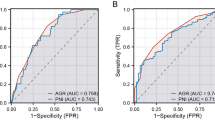

AGR2 is positively correlated with SLC40A1 expression in pancreatic cancer

Building on these findings, this study investigated the co-expression patterns of AGR2 and SLC40A1/FPN1 using both TCGA database analysis and our institutional PDAC patient cohort. The TCGA dataset showed that SLC40A1 was upregulated in PDAC tumors compared with normal pancreas (Fig. 7A). Transcriptomic analysis revealed a positive correlation between AGR2 and SLC40A1 mRNA expression levels (Fig. 7B; Supplementary fig. 5A–C). As 50–70 percent of PDAC patients harbor a mutation in p53, the rest of PDAC patients acquired wild-type p53 [20]. And subgroup analysis also showed positive correlation between two genes independent status of p53 (Supplementary fig. 5D–G). Further immunoblot analysis proved high expression of FPN1 in PDAC tumors (Fig. 7C). Subsequent immunohistochemical validation confirmed a positive correlation of AGR2 and FPN1 expression (Fig. 7D–F). The statues of p53 were listed in the Tables 1, Table 2. All the patients were divided into several groups according to the p53 status. For the patients with wild-type p53, the expression of AGR2 was positively correlated with the expression of the FPN1 (Supplementary fig. 5H); And for the patients with frameshift variant and stop gained p53, the expression of FPN1 did not correlated with AGR2 expression (Supplementary fig. 5I, J), which might due to the small number of patients in this group. For the patients with missense variant p53, the expression of FPN1 did positively correlate with AGR2 expression (Supplementary fig. 5J). Furthermore, survival analysis through Kaplan-Meier curves with log-rank testing demonstrated that high FPN1 and high AGR2 expression were significantly associated with reduced overall survival (OS) in PDAC patients (Fig. 7G). These results indicate that FPN1 is correlated with AGR2 expression in PDAC patients and is a marker for survival.

A Boxplot shows the expression of FPN1 in normal and PDAC tissues from the TCGA database. B Scatter plot shows the correlation between SLC40A1 and AGR2 in PDAC from the TCGA database. C Western blot analysis of FPN1 expression in normal pancreas and PDAC tissue. D Representative immunohistochemical staining shows the expression of FPN1 in pancreatic and PDAC tissues. Scale bar = 100 µm. E Representative immunohistochemical staining shows the expression of AGR2 in PDAC tissues. F Chi-square test shows the relationship between FPN1 and AGR2 expression in PDAC. G The correlation between AGR2/FPN1 double positive patients and the AGR2/FPN1 double negative group was analyzed.

AGR2 blocking with peptide sensitized PDAC cells to ferroptosis

Previous results have identified the AGR20-p53-FPN1 axis. We then investigated whether interfering with the AGR2-p53-FPN1 axis might sensitize PDAC to ferroptosis. Our previous study had identified a novel peptide in the treatment of pancreatic carcinogenesis [2]. As expected, peptide treatment increased RSL3 or erastin-induced cell death in HPAC and Capan2 cells (Fig. 8A, B). Immunoblot analysis showed peptide treatment induced upregulation of p53 and downregulation of FPN1 (Fig. 8C). MDA level, Fe2+, HMGB1, PTGS2 mRNA levels, and lipid ROS level were also induced with peptide (Fig. 8D–M). In vivo results showed that the peptide significantly inhibited tumor growth and was reversed by Lip-1 treatment (Fig. 7O, Supplementary fig. 6A–D). The immunohistochemistry staining of 4-HNE and Ki-67 of tumors proved that peptide treatment induced upregulation of 4-HNE and proliferative inhibition. And peptide treatment sensitized PDAC cells to IKE treatment, while this effect was reversed by Lip-1 treatment (Fig. 8P–S, Supplementary fig. 6E, F). These results confirmed that the peptide could provide potential therapeutic targets for developing ferroptosis-based interventions against PDAC.

A, B Bar charts show the cell death percentages in HPAC and Capan2 cells treated with Erastin or RSL3 under different concentrations. C Western blot analysis of FPN1, p53, and GAPDH protein levels in HPAC and Capan2 cells. D, E The bar chart shows the MDA levels in HPAC and Capan2 cells treated with the peptide. F, G Bar chart shows the Fe²⁺ levels in HPAC and Capan2 cells. H, I HMGB1 secretion levels in HPAC and Capan2 cells. J, K PTSG2 mRNA expression in HPAC and Capan2 cells. L, M Lipid ROS levels in HPAC and Capan2 cells. O Representative images of tumor xenografts from HPAC and Capan2 cells under different treatment conditions. P–S Quantification of 4-NHE and Ki-67 levels in HPAC and Capan2 tumors under different conditions.

Discussion

Pancreatic cancer remains one of the most lethal malignancies, characterized by dismal prognosis and the highest mortality rates among solid tumors [1, 21]. The paucity of effective therapeutic interventions constitutes a critical clinical challenge [22], compounded by limited progress in treatment strategies over recent decades. These unmet medical needs underscore the imperative to develop innovative therapeutic approaches. Emerging evidence has established ferroptosis as a promising therapeutic target in pancreatic cancer [23, 24]. Notably, AGR2 has emerged as a multifunctional oncoprotein implicated in tumorigenesis, metastatic progression, chemoresistance, and apoptosis regulation through modulation of carcinogenesis-associated signaling pathways [2, 25]. Nevertheless, the mechanistic interplay between AGR2 and ferroptosis regulation remains to be comprehensively elucidated. In the present study, we showed that ferroptosis induction upregulates AGR2 expression in PDAC cells. Importantly, our findings revealed that AGR2-mediated regulation of the p53/FPN1 axis enhances ferroptosis, positioning AGR2 as a novel regulatory target for modulating this cell death pathway in PDAC.

Ferroptosis is an iron-driven programmed cell death mechanism initiated by lipid peroxidation cascades under glutathione depletion, culminating in iron-mediated lipid peroxidation and subsequent cellular demise [26, 27]. This process is mechanistically governed by two core regulatory axes: systemic iron homeostasis and intracellular redox equilibrium [28]. As an essential micronutrient, iron’s pathophysiological impact is mediated through a network of metabolic regulators, including transferrin receptors, divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1), and iron regulatory protein 2 (IRP2), which collectively orchestrate cellular iron flux to modulate ferroptotic susceptibility [28]. Malignant progression is frequently associated with reprogrammed iron metabolism pathways encompassing acquisition, storage, utilization, and export mechanisms – adaptations that facilitate tumorigenic iron accumulation [29]. While the complete ferroptosis effector network remains to be fully elucidated, current evidence establishes iron-driven oxidative stress and consequent membrane lipid peroxidation as the central biochemical executors of this cell death pathway [30, 31]. Of relevance, AGR2 has been implicated in cellular homeostasis maintenance through its protein disulfide isomerase activity [32]. In this study, we observed significant AGR2 upregulation in PDAC cells following treatment with canonical ferroptosis inducers (erastin and RSL3). Notably, this induction is proved specific to ferroptotic stimuli, as co-treatment with necroptosis inhibitor NSA or pan-apoptosis inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK failed to reverse AGR2 elevation. CRISPR-mediated AGR2 knockout substantially enhanced PDAC cells’ sensitivity to ferroptosis induction, prompting mechanistic exploration through our established gene expression atlas. Transcriptomic analysis of AGR2-regulated networks revealed p53 is a key nodal point, consistent with its established dual regulatory roles in ferroptosis [14, 15]. Indeed, p53 is a well-known tumor suppressor frequently mutated in PDAC; however, more than 30 percent of PDAC patients maintain WT p53 [33]. Yet, precision therapy targeting p53 in one-third of PDAC cases is not available but desired. While p53 is recognized as a context-dependent ferroptosis modulator capable of both promoting and suppressing cell death [34], our prior work demonstrated AGR2’s oncogenic function through p53 suppression in PDAC carcinogenesis [2]. Currently, we have identified p53 as a potent suppressor of AGR2 knockout-induced ferroptosis sensitization. Mechanistic interrogation uncovered SLC40A1 (encoding ferroportin/FPN1) as a novel p53 transcriptional target, with p53 overexpression significantly repressing FPN1 expression. AGR2-knockout demonstrated concomitant FPN1 downregulation and elevated ferroptosis biomarkers.

FPN1,the exclusive iron export pump in mammals, maintains intracellular iron homeostasis through transmembrane efflux [11, 12]. Its dysfunction induces pathological iron overload through Fenton chemistry-mediated redox cycling between Fe²⁺ and Fe³⁺ [35], generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) that inflict macromolecular damage across DNA, proteins, lipids, and organelles [28]. This iron-dependent oxidative cascade constitutes the biochemical cornerstone of ferroptosis, with cellular iron accumulation shown to potentiate ferroptotic sensitivity across diverse cell types [28]. Consequently, our findings established the AGR2-p53-FPN1 axis as a critical regulatory circuit governing iron homeostasis and ferroptotic vulnerability in PDAC.

To investigate the functional role of FPN1 in pancreatic cancer, we generated FPN1-KO pancreatic cancer cell lines. Genetic ablation of FPN1 triggered significant upregulation of ferroptosis biomarkers and induced intracellular iron overload. Consistent with this finding, treatment with hepcidin - a known FPN1 inhibitor - similarly promoted iron accumulation and enhanced ferroptosis marker expression. Notably, these phenotypic changes were effectively reversed by co-treatment with the ferroptosis inhibitor Lip-1. Complementary in vivo experiments corroborated the tumor-promoting function of FPN1 in pancreatic cancer progression, aligning with prior mechanistic studies [28, 36].

Related clinical findings revealed a high positive correlation between AGR2 and FPN1 expression in pancreatic cancer specimens independent the statues of p53. Survival analysis demonstrated significantly reduced overall survival in patients exhibiting dual high expression of AGR2/FPN1 compared to those with low expression profiles. Moreover, TCGA data was used and analyzed. In total, the mRNA expression of AGR2 was positively correlated with mRNA expression of SLC40A1, and subgroup analysis also showed positive correlation between two genes. This result indicated that AGR2 is correlated with FPN1 (SLC40A1). Despite the key role of p53 in the AGR2/FPN1 axis, there might be potential other mechanisms need further investigation in the future. Mechanistically, our study identified the AGR2/p53/FPN1 regulatory axis as a critical modulator of ferroptosis susceptibility in pancreatic cancer. This novel pathway provides potential therapeutic targets for developing ferroptosis-based interventions against PDAC. And whether the activation of AGR2/p53/FPN1 regulatory axis in other cancers need further investigation.

Conclusion

In summary, our study demonstrates that inhibiting AGR2-dependent FPN1 expression contributes to ferroptosis resistance in PDAC cells in vitro and in vivo. The expression of AGR2 is positively correlated with FPN1 in pancreatic tumor tissues, which is related to the poor prognosis of pancreatic cancer patients. Therefore, targeting the AGR2/p53/FPN1 pathway may potentially tumor growth and enhance ferroptosis-based therapeutic strategies.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, in accordance with standard procedures.

References

Leonhardt CS, Gustorff C, Klaiber U, Le Blanc S, Stamm TA, Verbeke CS, et al. Prognostic Factors for Early Recurrence After Resection of Pancreatic Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2024;167:977–92.

Zhang Z, Li H, Deng Y, Schuck K, Raulefs S, Maeritz N, et al. AGR2-Dependent Nuclear Import of RNA Polymerase II Constitutes a Specific Target of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma in the Context of Wild-Type p53. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:1601–14.e1623.

Tian S, Chu Y, Hu J, Ding X, Liu Z, Fu D, et al. Tumour-associated neutrophils secrete AGR2 to promote colorectal cancer metastasis via its receptor CD98hc-xCT. Gut. 2022;71:2489–501.

Zhang H, Chi J, Hu J, Ji T, Luo Z, Zhou C, et al. Intracellular AGR2 transduces PGE2 stimuli to promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis of colorectal cancer. Cancer Lett. 2021;518:180–95.

Dumartin L, Alrawashdeh W, Trabulo SM, Radon TP, Steiger K, Feakins RM, et al. ER stress protein AGR2 precedes and is involved in the regulation of pancreatic cancer initiation. Oncogene. 2017;36:3094–103.

Hussein D, Alsereihi R, Salwati AAA, Algehani R, Alhowity A, Al-Hejin AM, et al. The anterior gradient homologue 2 (AGR2) co-localises with the glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78) in cancer stem cells, and is critical for the survival and drug resistance of recurrent glioblastoma: in situ and in vitro analyses. Cancer cell Int. 2022;22:387.

Yuan SH, Wu CC, Wang YC, Chan XY, Chu HW, Yang Y, et al. AGR2-mediated unconventional secretion of 14-3-3ε and α-actinin-4, responsive to ER stress and autophagy, drives chemotaxis in canine mammary tumor cells. Cellular Mol Biol Lett. 2024;29:84.

Li H, Zhang Z, Shi Z, Zhou S, Nie S, Yu Y, et al. Disrupting AGR2/IGF1 paracrine and reciprocal signaling for pancreatic cancer therapy. Cell Rep. Med. 2025;6:101927.

Shen X, Chen Y, Tang Y, Lu P, Liu M, Mao T, et al. Targeting pancreatic cancer glutamine dependency confers vulnerability to GPX4-dependent ferroptosis. Cell Rep. Med. 2025;6:101928.

de Laat V, Topal H, Spotbeen X, Talebi A, Dehairs J, Idkowiak J, et al. Intrinsic temperature increase drives lipid metabolism towards ferroptosis evasion and chemotherapy resistance in pancreatic cancer. Nature Commun. 2024;15:8540.

Marques O, Horvat NK, Zechner L, Colucci S, Sparla R, Zimmermann S, et al. Inflammation-driven NF-κB signaling represses ferroportin transcription in macrophages via HDAC1 and HDAC3. Blood. 2025;145:866–80.

Li L, Wang K, Jia R, Xie J, Ma L, Hao Z, et al. Ferroportin-dependent ferroptosis induced by ellagic acid retards liver fibrosis by impairing the SNARE complexes formation. Redox Biol. 2022;56:102435.

Zhang C, Yu JJ, Yang C, Shang S, Lv XX, Cui B, et al. Crosstalk between ferroptosis and stress-Implications in cancer therapeutic responses. Cancer Innov. 2022;1:92–113.

Liu Y, Su Z, Tavana O, Gu W. Understanding the complexity of p53 in a new era of tumor suppression. Cancer cell. 2024;42:946–67.

Zhao S, Liu X, Luo R, Jian Z, Xu C, Hou Y, et al. USP38 functions as an oncoprotein by downregulating the p53 pathway through deubiquitination and stabilization of MDM2. Cell Death Differ. 2025.

Freitas-Cortez MA, Masrorpour F, Jiang H, Mahmud I, Lu Y, Huang A, et al. Cancer cells avoid ferroptosis induced by immune cells via fatty acid binding proteins. Molecular cancer. 2025;24:40.

Zeng K, Huang N, Liu N, Deng X, Mu Y, Zhang X, et al. LACTB suppresses liver cancer progression through regulation of ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 2024;75:103270.

Geng N, Shi BJ, Li SL, Zhong ZY, Li YC, Xua WL, et al. Knockdown of ferroportin accelerates erastin-induced ferroptosis in neuroblastoma cells. European Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;22:3826–36.

Bao WD, Pang P, Zhou XT, Hu F, Xiong W, Chen K, et al. Loss of ferroportin induces memory impairment by promoting ferroptosis in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell death Differ. 2021;28:1548–62.

Morton JP, Timpson P, Karim SA, Ridgway RA, Athineos D, Doyle B, et al. Mutant p53 drives metastasis and overcomes growth arrest/senescence in pancreatic cancer. Proceedings Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:246–51.

Xue C, Chu Q, Zheng Q, Yuan X, Su Y, Bao Z, et al. Current understanding of the intratumoral microbiome in various tumors. Cell Rep. Med. 2023;4:100884.

Kleeff J, Michalski CW. Precision oncology for pancreatic cancer in real-world settings. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:469–71.

Xu W, Guan G, Yue R, Dong Z, Lei L, Kang H, et al. Chemical Design of Magnetic Nanomaterials for Imaging and Ferroptosis-Based Cancer Therapy. Chemical Rev. 2025;125:1897–961.

Qiao C, Wang L, Huang C, Jia Q, Bao W, Guo P, et al. Engineered Bacteria Manipulate Cysteine Metabolism to Boost Ferroptosis-Based Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Therapy. Advanced Mater (Deerfield Beach, Fla). 2025;37:e2412982.

Boisteau E, Posseme C, Di Modugno F, Edeline J, Coulouarn C, Hrstka R, et al. Anterior gradient proteins in gastrointestinal cancers: from cell biology to pathophysiology. Oncogene. 2022;41:4673–85.

Qian ZB, Li JF, Xiong WY, Mao XR. Ferritinophagy: A new idea for liver diseases regulated by ferroptosis. Hepatobiliary & pancreatic diseases international. HBPD INT. 2024;23:160–70.

Alves F, Lane D, Nguyen TPM, Bush AI, Ayton S. In defence of ferroptosis. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025;10:2.

Ru Q, Li Y, Chen L, Wu Y, Min J, Wang F. Iron homeostasis and ferroptosis in human diseases: mechanisms and therapeutic prospects. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9:271.

Yu R, Hang Y, Tsai HI, Wang D, Zhu H. Iron metabolism: backfire of cancer cell stemness and therapeutic modalities. Cancer cell Int. 2024;24:157.

Tang D, Chen X, Kang R, Kroemer G. Ferroptosis: molecular mechanisms and health implications. Cell Res. 2021;31:107–25.

Meng H, Yu Y, Xie E, Wu Q, Yin X, Zhao B, et al. Hepatic HDAC3 Regulates Systemic Iron Homeostasis and Ferroptosis via the Hippo Signaling Pathway. Research (Wash, DC). 2023;6:0281.

Qu S, Jia W, Nie Y, Shi W, Chen C, Zhao Z, et al. AGR2: The Covert Driver and New Dawn of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Cancer Treatment. Biomolecules 2024;14.

Integrated Genomic Characterization of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer cell 2017;32:185–203.e113.

Xu R, Wang W, Zhang W. Ferroptosis and the bidirectional regulatory factor p53. Cell death Discov. 2023;9:197.

Gattermann N, Muckenthaler MU, Kulozik AE, Metzgeroth G, Hastka J. The Evaluation of Iron Deficiency and Iron Overload. Deutsches Arzteblatt Int. 2021;118:847–56.

Zhang Y, Zou L, Li X, Guo L, Hu B, Ye H, et al. SLC40A1 in iron metabolism, ferroptosis, and disease: A review. WIREs mechanisms Dis. 2024;16:e1644.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply thankful to the patients and their families for their willingness to allow the use of tumor tissue for research. We thank Prof. Bo Kong for his revised the manuscript and providing of the peptide used in this study.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82203330, 82300887, 8200259, 82302327), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2022TQ0132, 2022M711589, 2024M760451). the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20220717), Distinguished Youth Project of Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital. Nanjing Health Science and Technology Development Project (YKK22065, YKK22267).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhang Z., Yang Y., Cheng T., and Zuo S. Designed and supervised the study. Song L., Shi N., Pan T., Zhang Q., Gong J., Zhang Q., Lu L., Li R. and Jian Z. collected and analyzed data and wrote the original draft. Cheng T., Zhang, W., and Li R. revised the paper. Zhang H., Pan T., Zhang Q., Gong J., Zhang Q., and Song J. conducted experiments. All authors participated in the revision of the manuscript and ratified the final version for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval for the experiments was obtained from the Animal Ethics Committee of Southeast University (20200407060) by the ethical requirements. All procedures that involved human sample collection were approved by the tissue bank of The Ethics Committee of Zhongda Hospital (2024ZDSYLL517-Y01), Southeast University (Nanjing, China). Informed consent was obtained from human participants or their family members.

Consent for publication

All authors have reviewed and agreed to the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Edited by Professor Piacentini

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jian, Z., Song, J., Lu, L. et al. AGR2 suppresses ferroptosis via the p53/FPN1 regulatory axis and drives therapeutic vulnerabilities in pancreatic cancer. Cell Death Dis 16, 877 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-025-08263-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-025-08263-y