Abstract

Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) hold significant promise for gene therapy targeting the central nervous system (CNS). However, current delivery methods are either invasive or cause significant systemic exposure. Intranasal (IN) delivery presents a promising noninvasive alternative for direct CNS targeting, though its efficacy in delivering AAVs to the brain has seldom been explored. Here, we quantitatively assessed AAV transduction in the brain and peripheral organs of Swiss, BALB/c, and C57BL/6 J mice following IN administration, using intravenous (IV) injection as a benchmark for comparison. Our findings revealed that IN administration of the AAV9 vector achieved approximately 15% of the transduction efficiency and 9% of the gene expression levels observed with IV delivery. Importantly, IN delivery significantly reduced systemic exposure to most major peripheral organs by up to 1.34 × 104-fold compared to IV injection. The ratios of gene transduction between the brain and various peripheral tissues were calculated, revealing that for key organs such as the liver, stomach, kidney, and spleen, IN delivery achieved higher brain-to-peripheral transduction ratios than IV delivery. These findings underscore the potential of IN delivery for noninvasive brain-targeted gene delivery with significant reductions in peripheral exposure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The central nervous system (CNS) is a key target for gene therapy, as it is often affected by genetic abnormalities underlying various neurological disorders [1,2,3]. Delivery of gene therapies to the CNS often relies on vector-based carriers to efficiently transport and introduce genetic material to target areas [4]. Among the available vectors, adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) stand out due to their favorable safety profile and ability to achieve stable, long-term gene expression [5,6,7]. AAV-based therapies, including Zolgensma—the first and only therapy clinically approved for a CNS disorder—have proven safe and effective in treating genetic conditions [8, 9]. However, despite significant advancements in CNS-targeted gene therapies, their clinical expansion remains limited by challenges with delivering these therapies safely to the brain [10].

The brain presents unique barriers that hinder gene delivery, most notably the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [11]. While essential for protecting the brain from harmful toxins and pathogens, this selective barrier also restricts the entry of many therapeutic agents, including AAV vectors. To address this challenge, several strategies have been developed to overcome the BBB and enhance delivery to the brain [10]. For instance, direct brain delivery methods, such as intrathecal or intracerebroventricular injection, have shown great promise in bypassing the BBB and delivering sufficient genetic payload to target regions; however, these methods are invasive and pose significant health and safety risks due to the nature of the procedures [12]. Consequently, less invasive approaches are needed to mitigate these concerns. Systemic AAV administration, primarily through intravenous (IV) infusion, remains the standard for minimally invasive gene transfer to the brain [13]. Certain AAV vectors, like AAV9 and AAVrh10, naturally cross the BBB when delivered systemically; however, peripheral exposure to these vectors can lead to adverse effects, including liver dysfunction, severe immune responses, and, in extreme cases, fatal outcomes [14].

In recent years, intranasal (IN) delivery has emerged as a promising noninvasive approach for brain drug delivery due to its ease of administration and potential to reduce peripheral exposure [15]. Preclinical and clinical studies have demonstrated successful delivery of neuropeptides, proteins, nanoparticles, and small-molecule drugs to the brain via the nasal route, highlighting its potential for treating neurodegenerative diseases, brain tumors, and other CNS disorders [16,17,18,19,20,21]. IN delivery of AAV vectors has also been explored for treatment of CNS disorders, primarily in preclinical models [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. For instance, this method has shown promise in treating mucopolysaccharidosis type I (MPS I), where IN application of AAV encoding the enzyme α-L-iduronidase (IDUA) restored enzyme activity in the brain, leading to reduced lysosomal storage materials and improved behavioral symptoms in MPS I mouse models [22,23,24]. Similarly, preclinical studies exploring IN AAV delivery for the treatment of depressive disorders have reported elevated levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, as well as reduced depressive-like behaviors, in rodent models that received AAV encoding BDNF intranasally [25,26,27,28,29]. Beyond depression, therapeutic AAV delivery through the nasal route has been applied to the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, demonstrating neuroprotective effects, including reduced amyloid and tau pathology, improved cognition, and sustained anti-Aβ immune responses, in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models [30, 31].

While IN delivery of AAV has shown therapeutic potential for CNS disease treatment, significant gaps remain in our understanding of its brain biodistribution and overall efficacy in targeting the brain. The objective of this study was to quantitatively assess AAV delivery to the brain following IN administration, comparing its outcomes to those of IV delivery as a benchmark of brain-targeting efficiency. This study utilized AAV9 encoding the enhanced green fluorescence protein (EGFP), delivered either intranasally or intravenously to Swiss, BALB/c, and C57BL/6 J mice. Multiple mouse strains were included to validate delivery efficiency across diverse genetic backgrounds.

This study addresses several key aspects. First, we analyzed the spatial distribution of AAV-mediated gene delivery across different brain regions following IN administration. Second, we assessed the overall brain-targeting efficiency of IN AAV delivery relative to the conventional IV administration route. Third, we evaluated peripheral exposure associated with IN delivery against IV administration. Assessing peripheral biodistribution provided insights into the potential off-target effects and overall safety profile of IN versus IV AAV delivery for CNS targeting.

Materials and methods

Animals

Adult Cr.NIH (Swiss), BALB/c, and C57BL/6 J mice (aged 8-12 weeks; average body weight 20–25 g) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA, USA). All animal procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Washington University in St. Louis (Protocol NO. 24-0222) and conducted in compliance with the National Institute of Health (NIH) Guidelines for animal research. Female mice were used across all strains to limit inter-group variability, given prior reports of sex-related differences in vector-mediated transduction and transgene expression efficiency [32,33,34,35]. Mice were housed in a room maintained at 23–26°C and 55% relative humidity, under a 12 h light/dark cycle, and were provided access to standard laboratory chow and water. Ten of each mouse strain (30 mice total) were randomly divided into two experimental groups: one receiving IN administration and the other receiving IV administration.

AAV administration

AAV9, under the control of the human synapsin promoter and carrying the EGFP reporter gene, was obtained from Addgene (Catalog #50465, Watertown, MA, USA). The viral titer was provided by the manufacturer as 1.9 × 1013 viral genomes (vg)/mL. Mice in all experimental groups received 20 µL of the viral solution. Prior to administration, mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine cocktail (100 µL/kg; Dechra Pharmaceuticals, Northwich, UK).

To perform IN administration, the anesthetized mice were positioned supine on a heated surface, with padding placed under their heads to maintain a flat neck. The viral solution was administered by gently pipetting 2 µL droplets into each nostril, alternating between nostrils at 2-min intervals. For IV administration, the mice were secured to a heated stereotactic frame and a catheter inserted into their tail vein. The viral solution was infused through the catheter, followed by a saline flush. Mice were returned to their respective cages after full recovery from anesthesia.

Tissue collection

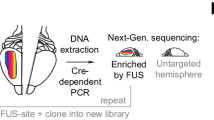

Four weeks post-treatment, mice were transcardially perfused with 1× phosphate-buffered saline while under deep isoflurane anesthesia. Immediately following perfusion, their brains were harvested and dissected. Each brain was divided into the left and right hemispheres, and the olfactory bulb, cerebellum, and brainstem were isolated. The remaining brain tissue, comprising the majority of the forebrain and midbrain regions, were coronally sectioned into two equal segments, as illustrated in Fig. 1A. Samples of peripheral tissues, including the nose, lung, heart, liver, stomach, intestine, kidney, and spleen were also collected. All tissues were frozen on dry ice and stored at -80°C until further processing.

A Mouse brains were segmented into the olfactory bulb (OB), large forebrain and midbrain areas (B1 and B2), cerebellum (CBM), and brainstem (BS) to assess AAV biodistribution. EGFP DNA copies B and protein concentrations C were measured in these brain regions across Swiss, BALB/c, and C57BL/6 J mouse strains. DNA levels are given as a ratio of EGFP copies to 1 000 mouse beta-actin (mActb) gene copies, while protein levels are expressed as picograms (pg) of EGFP protein per microgram (µg) of total protein. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA, with Tukey’s post-hoc test used to correct for multiple comparisons. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), with N = 5 mice per group. Asterisks (*) denote comparisons with the olfactory bulb within the same strain (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001), while hashtags (#) indicate comparisons with the olfactory bulb of C57BL/6 J mice (#p < 0.05). Heatmaps illustrating the relative AAV biodistribution in the mouse brain were generated by calculating the ratios of EGFP DNA D and protein levels E in each brain region to total brain levels.

EGFP DNA quantification by ddPCR

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from fresh-frozen mouse tissue samples using the Column-Pure Animal Genomic DNA Kit (Lamda Biotech, #D427-100, Ballwin, MO, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration and purity of gDNA were measured using the NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The gDNA was diluted to 5–20 ng/μL for droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR) analysis to quantify EGFP DNA levels in the mouse tissue samples. The forward and reverse primer sequences for EGFP were 5’- GACCAC-TACCAGCAGAACACC -3’ and 5’- CCAGCAGGACCATGTGATCG -3’, respectively. The EGFP probe, sequenced as 5’- CCGACAACCACTACCTGAGCACCCAGTC -3’, was labeled with a hexachlorofluorescein (HEX) fluorophore and a Black Hole Quencher 1 (BHQ1). ddPCR reactions were conducted using the Bio-Rad Q200X according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Data were acquired using the QX600 droplet reader (Bio-Rad) and analyzed using QX Manager Software (Bio-Rad). All results were manually reviewed for false-positive and background noise droplets based on negative and positive control samples. EGFP DNA levels were then normalized to the mouse beta-actin (mActb) gene by dividing EGFP DNA copy numbers (provided by QX Manager) by mActb gene copy numbers (also provided by QX Manager). The beta-actin gene, commonly used as an internal control in quantitative gene expression analyses [36], accounted for variations in DNA input and quality across samples. ddPCR evaluation was performed by an experimenter without knowledge of the experimental conditions.

EGFP protein quantification by ELISA

Fresh-frozen tissue samples were homogenized and lysed in 1× RIPA buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, catalog #9806, Danvers, MA, USA) containing protease inhibitors. Total protein concentrations were measured using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, catalog #23225, Waltham, MA, USA). EGFP protein levels were quantified using an EGFP-specific ELISA kit (Abcam, ab229403, Cambridge, UK). ELISA was performed following the manufacturer’s guidelines, and fluorescence signals were measured using the BioTek Cytation 5 reader (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). EGFP protein concentrations were calculated based on a standard curve and normalized to the total protein concentration of each tissue sample.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (version 10, La Jolla, CA, USA). All experimental groups included N = 5 mice to enable statistically meaningful comparisons across strains and delivery routes. All reported outcomes reflect data from a single experimental cohort per condition. Technical replicates (N ≥ 3) were included for all molecular assays performed in this study. Statistical methods are specified in the figure legends. Differences in means were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Results

IN AAV administration predominantly targets the olfactory bulb

EGFP DNA and protein levels in the mouse brain were quantified in various brain regions following IN AAV administration. AAV was detected primarily in the olfactory bulb, where EGFP DNA copy numbers were 3.51- to 105.57-fold higher (Fig. 1B) and protein concentrations were 2.03- to 91.88-fold higher (Fig. 1C) than in other brain regions across all mouse strains.

When comparing AAV delivery efficiency between the different strains tested, few strain-specific differences were observed, particularly between the olfactory bulb of the different mouse strains. For instance, C57BL/6 J mice exhibited approximately 2.83-fold higher transgene DNA copy numbers in the olfactory bulb compared to Swiss mice (36.46 ± 24.53 versus 12.87 ± 6.90 EGFP copies per 1000 mActb gene copies; p = 0.0496; Fig. 1B). Conversely, the average protein concentration in the olfactory bulb of C57BL/6 J mice (0.16 ± 0.02 pg EGFP protein per µg total protein) was the lowest among the three strains, significantly lower than that of BALB/c mice (0.26 ± 0.01 pg EGFP protein per µg total protein) by 1.63-fold (p = 0.0265; Fig. 1C). Nonetheless, the overall contribution of mouse strain to variation in the datasets was minimal, with p-values of 0.4950 and 0.7305 for EGFP DNA and protein levels, respectively, based on two-way ANOVA analysis. In contrast, the contribution of brain region to variation in the datasets was significant, with p = 0.0012 for transgene copies and p < 0.0001 for protein levels. These findings suggest that while IN AAV delivery to the brain resulted in regional variation, the overall efficiency in transducing the brain remained largely consistent across the tested mouse strains.

To visualize the spatial distribution of AAV-mediated gene transduction and expression in the brain following IN delivery, the ratios of EGFP DNA and protein levels in each brain region relative to total brain levels were calculated and presented as heatmaps (Fig. 1D and 1E). Across all mouse strain groups, DNA and protein ratios in the olfactory bulb accounted for over half (≥ 0.58) of the total levels in the brain. Outside the olfactory bulb, DNA ratios were highest in the B1 region, representing 0.11 to 0.21 of the total DNA levels across strains (Fig. 1D). Similarly, protein ratios in the B1 and B2 regions were elevated, accounting for 0.12 to 0.20 of the overall detected levels (Fig. 1E). In contrast, protein ratios in the cerebellum and brainstem were considerably low, ranging from 0.01 to 0.02 of the total. These findings suggest that IN AAV-mediated gene delivery primarily targets the forebrain and midbrain regions, with the highest localization in the olfactory bulb and minimal activity in the hindbrain.

IN achieves lower gene transfer to the brain compared to IV

To assess the efficiency of IN AAV delivery compared to IV infusion, we calculated the mean DNA and protein levels from brain sections extracted from IV-treated mice (N = 5 mice per strain). These means were then used as a baseline to calculate the ratios of EGFP DNA and protein levels in the brain regions of the IN-treated groups relative to the IV groups (Fig. 2). EGFP DNA levels in the olfactory bulb from IN administration were generally lower than those observed with IV infusion (0.73 and 0.74 times lower in Swiss and BALB/c mice, respectively), except in C57BL/6 J mice, where levels averaged 2.39 times those observed in IV-treated C57BL/6 J mice. However, protein expression levels in the olfactory bulb following IN delivery were lower across all strains, averaging 0.17, 0.28, and 0.14 times the levels observed in the IV-treated Swiss, BALB/c, and C57BL/6 J mice, respectively. In the other brain regions, mean EGFP DNA and protein levels did not exceed 0.14 and 0.06 times those achieved from IV delivery, respectively, across all strains.

Mean DNA and protein levels from the brain sections of IV-treated mice were calculated and are shown as a baseline (indicated by a red horizontal line). Ratios of DNA (top row) and protein levels (bottom row) in the dissected brain regions, as well as in the whole brain of IN-treated Swiss (left column), BALB/c (middle column), and C57BL/6 J (right column) mice were calculated relative to the mean DNA and protein levels of corresponding brain regions from IV-treated groups. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. N = 5 mice per group. OB: olfactory bulb; B1 and B2: brain segments 1 and 2; CBM: cerebellum; BS: brainstem; WB: whole brain.

EGFP DNA copy numbers and protein concentrations were averaged across all brain regions for each mouse in both the IN and IV groups to represent whole brain levels. Ratios of whole brain levels from the IN groups to average whole brain levels of the corresponding IV groups were then calculated. IN delivery achieved 0.28 times the DNA levels of IV delivery in the whole brain of C57BL/6 J mice, the highest among the IN groups. Similarly, protein concentrations from IN delivery averaged 0.10 times those from IV infusion in BALB/c mice, also the highest among the strains. Overall, IN administration achieved approximately 0.15 times the EGFP DNA levels and 0.09 times the protein levels observed with IV delivery in the whole brain, averaged across all tested mouse strains. These findings highlight the reduced gene transduction and expression efficiency in the brain through IN AAV administration compared to IV delivery.

IN minimizes systemic exposure to major peripheral organs compared to IV

EGFP DNA copies were measured in seven major peripheral organs to evaluate the systemic distribution of AAV following IN and IV administration (Fig. 3). DNA levels in the nasal tissue were also assessed to examine AAV localization within the nasal cavity after IN delivery compared to IV. In the IN groups, DNA copies were detected predominantly in the nasal tissue and lungs across all strains. In contrast, IV administration resulted in the highest DNA copy numbers observed in the liver, kidney, and spleen compared to other tissues.

Copy numbers were quantified in the nasal tissue, lung, heart, liver, stomach, intestine, kidney, and spleen of Swiss (top), BALB/c (middle), and C57BL/6 J (bottom) mice. DNA levels are given as a ratio of EGFP copies to 1000 mouse beta-actin (mActb) gene copies. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (N = 5 mice per group). Nonparametric multiple t-tests were used to analyze this data, and the Mann-Whitney test was used to compare ranks between each group (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

Between the two delivery methods, EGFP DNA levels were significantly lower in the liver (by 4.39 × 103-fold, 7.66 × 103-fold, and 1.34 × 104-fold for Swiss, BALB/c, and C57BL/6 J mice, respectively), stomach (by 34.96-fold, 34.03-fold, and 51.52-fold for Swiss, BALB/c, and C57BL/6 J mice, respectively), intestine (by 17.22-fold, 25.34-fold, and 53.86-fold for Swiss, BALB/c, and C57BL/6 J mice, respectively), kidney (by 675.44-fold, 35.80-fold, and 30.56-fold for Swiss, BALB/c, and C57BL/6 J mice, respectively), and spleen (by 216.64-fold, 14.68-fold, and 18.76-fold for Swiss, BALB/c, and C57BL/6 J mice, respectively) of IN groups compared to IV groups. Conversely, DNA copy numbers were higher in the nasal tissue (by 3.19-fold, 3.23-fold, and 2.62-fold for Swiss, BALB/c, and C57BL/6 J mice, respectively) and lungs (by 5.45-fold, 1.51 × 103-fold, 5.01-fold for Swiss, BALB/c, and C57BL/6 J mice, respectively) post-IN delivery compared to IV administration, though these differences were not statistically significant. Overall, these findings indicate that IN administration leads to AAV accumulation primarily in the nasal tissue and lungs while significantly reducing systemic spread to other major peripheral organs compared to IV delivery.

IN delivery demonstrates higher brain-to-peripheral transduction ratios for most peripheral organs compared to IV

Although IN AAV administration resulted in lower overall brain transduction compared to IV delivery, its significant reduction in peripheral tissue exposure offers a distinct advantage for brain-targeted gene delivery. Systemic administration often results in high peripheral exposure, increasing the risk of adverse effects such as hepatotoxicity and immune activation [37, 38]. As depicted in Fig. 3, IN administration reduced peripheral distribution by up to 1.34 × 104-fold compared to IV delivery—the largest observed difference in peripheral AAV genome levels between IN- and IV-treated groups across all mouse strains and organs analyzed, specifically in the liver of C57BL/6 J mice—highlighting its potential to minimize off-target effects and enhance the safety profile of AAV-based CNS therapies.

To assess the brain-targeting efficiency of IN versus IV AAV administration relative to peripheral distribution, ratios of EGFP DNA copy numbers in the brain to those in peripheral tissues were calculated. As shown in Fig. 4, ratios were significantly higher for IN compared to IV delivery in the brain-to-liver (52.94 for IN versus 1.01 for IV, Fig. 4D), brain-to-stomach (31.51 for IN versus 1.88 for IV, Fig. 4E), brain-to-kidney (12.12 for IN versus 0.21 for IV, Fig. 4G), and brain-to-spleen (1.05 for IN versus 0.04 for IV, Fig. 4H) comparisons. In contrast, the brain-to-nasal tissue ratio was significantly higher for IV than IN administration (0.05 for IN versus 1.17 for IV, Fig. 4A), reflecting the consequential accumulation of AAV in the nasal tissue following IN delivery. For other comparisons, including the brain-to-heart (207.53 for IN versus 14.78 for IV, Fig. 4C) and brain-to-intestine (37.34 for IN versus 1.66 for IV, Fig. 4F) ratios, IN exhibited overall higher brain-to-peripheral ratios than IV, though these differences were not statistically significant. Brain-to-lung ratios were similar between the IN and IV groups (29.16 for IN versus 35.44 for IV, Fig. 4B), indicating comparable efficiency in brain targeting relative to the lungs between the two delivery methods.

Ratios of mean EGFP DNA levels in the brain were calculated relative to the nasal tissue A, lung B, heart C, liver D, stomach E, intestine F, kidney G, and spleen H. Data from all tested mouse strains were pooled for each plot. The grand mean of the pooled data is shown in each plot, and statistical comparisons between the ranks of pooled IN and IV data were conducted using a two-tailed Mann-Whitney test (ns: not significant, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001).

Overall, this data highlights a trade-off between the two administration routes. While IV delivery achieves greater AAV transduction in the brain, it is associated with substantial systemic spread to peripheral tissues, which may compromise its effectiveness for CNS-specific treatment. Conversely, IN delivery, though less efficient in targeting the brain, significantly reduces systemic spread to major peripheral organs, potentially making it a safer option for brain-targeted gene delivery, particularly in cases where minimizing off-target effects in major peripheral organs is desired.

Discussion

This study evaluated the biodistribution of AAV9 in the brain and peripheral tissues following IN administration. It is the first to quantitatively assess whole brain transduction efficiency via IN delivery and directly contrast it with IV administration, offering new insights into the nasal route’s effectiveness for brain targeting compared to the conventional IV method.

Although IN delivery of AAV to the brain has not been directly compared with IV, it has been previously compared with other routes, such as intracerebroventricular and intrathecal injection. In a study by Belur et al., IN delivery of AAV9 encoding the IDUA gene resulted in lower overall enzyme levels in the brain compared to intracerebroventricular and intrathecal injection. However, it still provided sufficient enzyme activity to prevent neurocognitive deficits in a rodent model of MPS I [24]. These findings underscore the potential of IN AAV delivery for CNS disease treatment despite its lower brain transduction efficiency relative to other routes. Notably, the same study also found that IN delivery produced the highest enzyme activity in the olfactory bulb, consistent with our findings of the highest EGFP DNA and protein levels detected in the olfactory bulb following IN AAV9 administration. Similar observations have been documented in other studies. For instance, an earlier study by Belur et al. briefly examined IN delivery of AAV9 encoding GFP and found GFP expression confined exclusively to the olfactory epithelium and olfactory bulb [23]. Likewise, Mathiesen et al. reported restricted transgene expression in the olfactory bulb after nasal administration of both AAV-PHP.eB and AAV9 encoding tdTomato and GFP, respectively [39]. Both studies concluded that no transgene expression was detected in other brain regions; however, these conclusions were based solely on histological and immunofluorescence image-based analyses and lacked further quantitative assessments to support their findings. Our study builds upon these prior image-based assessments by employing precise and sensitive quantitative methods (ddPCR and ELISA) to evaluate AAV-based gene transduction and expression across multiple brain regions, providing additional interpretation of the delivery efficiency and gene distribution patterns achieved through IN administration. Nonetheless, future studies integrating advanced spatial and cell-type–resolved techniques, such as RNAscope or single-cell transcriptomics, alongside quantitative analyses would further strengthen the assessment of transgene distribution and elucidate the cellular specificity of AAV delivery via the intranasal route.

Our study demonstrated that AAV can reach the brain through the nasal pathway, with transduction primarily localized to the olfactory bulb. In C57BL/6 J mice, transgene DNA levels in the olfactory bulb following IN AAV9 delivery reached those observed with IV administration, highlighting the potential of the nasal route to achieve similar gene transduction in this region. The localized transduction observed in the brain following IN delivery suggests its suitability for targeting forebrain regions near the olfactory bulb while limiting distribution to hindbrain areas such as the cerebellum and brainstem. Nonetheless, across all the mice strains tested in this study, IN delivery to the brain achieved approximately 15% the EGFP DNA levels and 9% the protein levels observed with IV administration, reflecting lower overall delivery efficiency. While this reduced efficiency may limit its applicability for certain CNS disease treatments, its localized targeting may provide significant therapeutic potential, particularly in contexts where selective delivery to specific forebrain regions is desired.

In addition to analyzing brain delivery, our study evaluated peripheral biodistribution following IN AAV9 delivery and compared it to IV administration. We observed that systemic distribution to major peripheral organs was significantly reduced following IN delivery compared to IV administration. Similar findings were reported by Ye et al., who also compared peripheral biodistribution between IN and IV delivery of the AAV5 vector in Swiss mice [40]. In their study, peripheral tissues collected four weeks post-delivery showed significantly lower transgene DNA levels in the heart, liver, stomach, intestine, kidney, and spleen for mice that received IN delivery compared to IV delivery, consistent with our findings. Also consistent with our results, Ye et al. detected higher transgene DNA levels in the lungs following IN delivery compared to IV delivery, though this difference was not statistically significant in either study. Our work expands the findings of Ye et al. to the clinically relevant AAV9 vector while confirming similar patterns of peripheral exposure observed with AAV5. Additionally, by incorporating multiple mouse strains, our study demonstrates consistent brain and peripheral biodistribution profiles across different genetic backgrounds.

In our study, the ratios of EGFP DNA levels detected in the brain to those detected in various peripheral tissues were calculated to assess the efficiency of brain delivery relative to peripheral exposure. The brain-to-peripheral transduction ratios for the liver, kidney, spleen, and stomach were significantly higher for IN compared to IV delivery. These findings further emphasize the ability of IN delivery to minimize systemic exposure to major peripheral organs despite its lower delivery efficiency to the brain.

It is important to note that IN delivery resulted in high AAV9 accumulation in the nasal and lung tissues compared to IV delivery. This aligns with previous studies, which have shown that viral capsids administered intranasally effectively localize and express in the nasal and lung airway epithelia [41,42,43,44,45]. Interestingly, Belur et al. suggested potential therapeutic benefits of ectopic transgene expression in the nasal epithelium for treating CNS disorders [23]. In their study, nasal infusion of AAV9 carrying the IDUA gene led to a reduction in lysosomal storage materials in the brains of MPS I mice. This effect was hypothesized to result from diffusion of the expressed IDUA enzyme from the nasal epithelium and olfactory bulb into affected brain regions. This finding suggests that gene expression in the nasal area could be beneficial for treating CNS disorders in instances where the expressed gene is secretory.

Overall, many factors can influence intranasal AAV-mediated gene delivery and biodistribution to the central nervous system. Vector characteristics, such as capsid serotype and promoter selection, greatly influence AAV transduction efficiency, cellular specificity, and tissue tropism following administration. Distinct AAV serotypes exhibit varying affinities for specific tissues and cell types, with serotypes like AAV2, AAV5, AAV9, and AAVrh10 having shown enhanced CNS tropism in various studies [46,47,48]. Likewise, the choice of promoter, which directs transgene expression via host transcriptional machinery, plays a key role in the AAV targeting specificity. While ubiquitous promoters such as CMV, CAG, and EF1α drive broad expression, cell type- or region-specific promoters restrict transgene expression to defined cellular populations, thereby improving targeting precision and minimizing off-target effects [49,50,51].

Beyond capsid and promoter selection, additional vector elements may further impact intranasal AAV delivery outcomes, including regulatory elements—for instance, the woodchuck hepatitis virus post-transcriptional regulatory element and synthetic introns—that enhance transgene expression, genome configuration (single-stranded versus self-complementary AAV), which affects expression kinetics, and vector genome size and packaging efficiency [52,53,54]. Vector dose and formulation, such as the use of surfactants, mucolytics, or permeation enhancers, can further modulate nasal uptake and subsequent CNS targeting [55, 56]. Systematic evaluation of these variables is essential for enhancing the safety and efficacy of IN-mediated gene delivery to the brain.

Advanced strategies to enhance AAV delivery to the brain can also be explored in the future to further improve the efficacy of intranasal AAV delivery. One potential solution for increased brain transduction may be the modification of AAV vectors to enhance absorption and retention through the nose-to-brain pathway. In recent years, scientists have developed advanced technologies, such as capsid engineering, to enhance BBB-crossing abilities of AAV for systemic administration [57,58,59,60]. However, these engineered AAV vectors may not improve retention in the brain following IN delivery, as transport mechanisms through the nasal cavity differ. For instance, Mathiesen et al. demonstrated that the engineered PHP.eB vector capsid, which significantly enhances brain transduction after systemic IV administration, did not exhibit the same effect after intranasal administration [39]. Therefore, understanding barriers specific to nose-to-brain transport, such as mucociliary clearance, the nasal epithelial barrier, and enzymatic degradation in the nasal mucosa, may guide the development of vectors capable of efficient brain absorption via the nasal route [61,62,63].

Another promising approach that has already been demonstrated to enhance IN AAV uptake in the brain is the application of focused ultrasound combined with microbubbles [40]. This noninvasive method, known as focused ultrasound-mediated intranasal (FUSIN) delivery, employs transcranial acoustic energy to induce microbubble cavitation, facilitating the transport of intranasally administered agents to specific brain regions [64]. In the study by Ye et al., focused ultrasound application was shown to enhance AAV delivery and gene expression in the brainstem and cortex following IN administration, demonstrating the potential of FUSIN to facilitate targeted delivery to the brain [40]. Despite these advancements, significant gaps remain in our understanding of the long-term effects of intranasal AAV administration, the precise mechanisms governing AAV transport from the nasal cavity to the brain, and potential sex-based differences in vector biodistribution and transgene expression via the nasal route. Future research is needed to address these gaps and to further optimize IN delivery in efforts to overcome the limitations of this promising method.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available in the WashU Research Data Repository (https://doi.org/10.7936/6RXS-108271).

References

Fiandaca MS, Lonser RR, Elder JB, Ząbek M, Bankiewicz KS. Advancing gene therapies, methods, and technologies for Parkinson’s Disease and other neurological disorders. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2020;54:220–31.

Pena SA, Iyengar R, Eshraghi RS, Bencie N, Mittal J, Aljohani A, et al. Gene therapy for neurological disorders: challenges and recent advancements. J Drug Target. 2020;28:111–28.

Parambi DGT, Alharbi KS, Kumar R, Harilal S, Batiha GES, Cruz-Martins N, et al. Gene Therapy Approach with an Emphasis on Growth Factors: Theoretical and Clinical Outcomes in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Mol Neurobiol. 2022;59:191–233.

Gao J, Gunasekar S, Xia Z, Shalin K, Jiang C, Chen H, et al. Gene therapy for CNS disorders: modalities, delivery and translational challenges. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2024;25:553–72.

Pupo A, Fernández A, Low SH, François A, Suárez-Amarán L, Samulski RJ. AAV vectors: The Rubik’s cube of human gene therapy. Mol Ther. 2022;30:3515–41.

Au HKE, Isalan M, Mielcarek M. Gene Therapy Advances: A Meta-Analysis of AAV Usage in Clinical Settings. Front Med. 2022;8:809118.

Ling Q, Herstine JA, Bradbury A, Gray SJ. AAV-based in vivo gene therapy for neurological disorders. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2023;22:789–806.

Singh M, Brooks A, Toofan P, McLuckie K. Selection of appropriate non-clinical animal models to ensure translatability of novel AAV-gene therapies to the clinic. Gene Ther. 2024;31:56–63.

Stevens D, Claborn MK, Gildon BL, Kessler TL, Walker C. Onasemnogene Abeparvovec-xioi: Gene Therapy for Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Ann Pharmacother. 2020;54:1001–9.

Kang L, Jin S, Wang J, Lv Z, Xin C, Tan C, et al. AAV vectors applied to the treatment of CNS disorders: Clinical status and challenges. J Controlled Release. 2023;355:458–73.

Wu D, Chen Q, Chen X, Han F, Chen Z, Wang Y. The blood–brain barrier: structure, regulation, and drug delivery. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:217.

Vuillemenot BR, Korte S, Wright TL, Adams EL, Boyd RB, Butt MT. Safety evaluation of CNS administered biologics-study design, data interpretation, and translation to the clinic. Toxicol Sci. 2016;152:3–9.

Gessler DJ, Tai PWL, Li J, Gao G. Intravenous infusion of AAV for widespread gene delivery to the nervous system. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;1950:143–63.

Shen W, Liu S, Ou L. rAAV immunogenicity, toxicity, and durability in 255 clinical trials: A meta-analysis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1001263.

Lochhead JJ, Thorne RG. Intranasal delivery of biologics to the central nervous system. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:614–28.

Kubek MJ, Domb AJ, Veronesi MC. Attenuation of Kindled Seizures by Intranasal Delivery of Neuropeptide-Loaded Nanoparticles. Neurotherapeutics. 2009;6:359–71.

Mathé AA, Michaneck M, Berg E, Charney DS, Murrough JW. A randomized controlled trial of intranasal Neuropeptide Y in patients with major depressive disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;23:783–90.

Migliore MM, Vyas TK, Campbell RB, Amiji MM, Waszczak BL. Brain delivery of proteins by the intranasal route of administration: A comparison of cationic liposomes versus aqueous solution formulations. J Pharm Sci. 2010;99:1745–61.

Meredith ME, Salameh TS, Banks WA. Intranasal Delivery of Proteins and Peptides in the Treatment of Neurodegenerative Diseases. AAPS J. 2015;17:780–7.

Gao X, Chen J, Tao W, Zhu J, Zhang Q, Chen H, et al. UEA I-bearing nanoparticles for brain delivery following intranasal administration. Int J Pharm. 2007;340:207–15.

Zhang C, Chen J, Feng C, Shao X, Liu Q, Zhang Q, et al. Intranasal nanoparticles of basic fibroblast growth factor for brain delivery to treat Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Pharm. 2014;461:192–202.

Wolf DA, Hanson LR, Aronovich EL, Nan Z, Low WC, Frey WH, et al. Lysosomal enzyme can bypass the blood-brain barrier and reach the CNS following intranasal administration. Mol Genet Metab. 2012;106:131–4.

Belur LR, Temme A, Podetz-Pedersen KM, Riedl M, Vulchanova L, Robinson N, et al. Intranasal Adeno-Associated Virus Mediated Gene Delivery and Expression of Human Iduronidase in the Central Nervous System: A Noninvasive and Effective Approach for Prevention of Neurologic Disease in Mucopolysaccharidosis Type i. Hum Gene Ther. 2017;28:576–87.

Belur LR, Romero M, Lee J, Podetz-Pedersen KM, Nan Z, Riedl MS, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Intracerebroventricular, Intrathecal, and Intranasal Routes of AAV9 Vector Administration for Genetic Therapy of Neurologic Disease in Murine Mucopolysaccharidosis Type I. Front Mol Neurosci. 2021;14:618360.

Ma XC, Chu Z, Zhang XL, Jiang WH, Jia M, Dang YH, et al. Intranasal Delivery of Recombinant NT4-NAP/AAV Exerts Potential Antidepressant Effect. Neurochem Res. 2016;41:1375–80.

Ma XC, Liu P, Zhang XL, Jiang WH, Jia M, Wang CX, et al. Intranasal Delivery of Recombinant AAV Containing BDNF Fused with HA2TAT: A Potential promising therapy strategy for major depressive disorder. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22404.

Liu F, Liu YP, Lei G, Liu P, Chu Z, Gao CG, et al. Antidepressant effect of recombinant NT4-NAP/AAV on social isolated mice through intranasal route. Oncotarget. 2017;8:10103–13.

Li XL, Liu H, Liu SH, Cheng Y, Xie GJ. Intranasal Administration of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Rescues Depressive-Like Phenotypes in Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress Mice. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2022;18:1885–94.

Chen C, Dong Y, Liu F, Gao C, Ji C, Dang Y, et al. A study of antidepressant effect and mechanism on intranasal delivery of BDNF-HA2TAT/AAV to rats with post-stroke depression. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2020;16:637–49.

Qi B, Yang Y, Cheng Y, Sun D, Wang X, Khanna R, et al. Nasal delivery of a CRMP2-derived CBD3 adenovirus improves cognitive function and pathology in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Mol Brain. 2020;13:58.

Zhang J, Wu X, Qin C, Qi J, Ma S, Zhang H, et al. A novel recombinant adeno-associated virus vaccine reduces behavioral impairment and β-amyloid plaques in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2003;14:365–79.

Davidoff AM, Ng CYC, Zhou J, Spence Y, Nathwani AC. Sex significantly influences transduction of murine liver by recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors through an androgen-dependent pathway. Blood. 2003;102:480.

Voutetakis A, Zheng C, Wang J, Goldsmith CM, Afione S, Chiorini JA, et al. Gender differences in serotype 2 adeno-associated virus biodistribution after administration to rodent salivary glands. Hum Gene Ther. 2007;18:1109–18.

Pfeifer C, Aneja MK, Hasenpusch G, Rudolph C. Adeno-associated virus serotype 9-mediated pulmonary transgene expression: Effect of mouse strain, animal gender and lung inflammation. Gene Ther. 2011;18:1034–42.

Guzman E, Khoo C, O’Connor D, Devarajan G, Iqball S, Souberbielle B, et al. Gender difference in pre-clinical liver-directed gene therapy with lentiviral vectors. Exp Biol Med. 2025;250:10422.

Stephens AS, Stephens SR, Morrison NA. Internal control genes for quantitative RT-PCR expression analysis in mouse osteoblasts, osteoclasts and macrophages. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:410.

Ertl HCJ. Immunogenicity and toxicity of AAV gene therapy. Front Immunol. 2022;13:975803.

Jagadisan B, Dhawan A. Hepatotoxicity in Adeno-Associated Viral Vector Gene Therapy. Curr Hepatol Rep. 2023;22:276–90.

Mathiesen SN, Lock JL, Schoderboeck L, Abraham WC, Hughes SM. CNS Transduction Benefits of AAV-PHP.eB over AAV9 Are Dependent on Administration Route and Mouse Strain. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2020;19:447–58.

Ye D, Yuan J, Yang Y, Yue Y, Hu Z, Fadera S, et al. Incisionless targeted adeno-associated viral vector delivery to the brain by focused ultrasound-mediated intranasal administration. EBioMedicine. 2022;84:104277.

Auricchio A, O’Connor E, Weiner D, Gao GP, Hildinger M, Wang L, et al. Noninvasive gene transfer to the lung for systemic delivery of therapeutic proteins. J Clin Investig. 2002;110:499–504.

Limberis MP, Wilson JM. Adeno-associated virus serotype 9 vectors transduce murine alveolar and nasal epithelia and can be readministered. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:12993–8.

Quinn K, Quirion MR, Lo CY, Misplon JA, Epstein SL, Chiorini JA. Intranasal administration of adeno-associated virus type 12 (AAV12) leads to transduction of the nasal epithelia and can initiate transgene-specific immune response. Mol Ther. 2011;19:1990–8.

Myint M, Limberis MP, Bell P, Somanathan S, Haczku A, Wilson JM, et al. In vivo evaluation of adeno-associated virus gene transfer in airways of mice with acute or chronic respiratory infection. Hum Gene Ther. 2014;25:966–76.

Limberis MP, Vandenberghe LH, Zhang L, Pickles RJ, Wilson JM. Transduction efficiencies of novel AAV vectors in mouse airway epithelium in vivo and human ciliated airway epithelium in vitro. Mol Ther. 2009;17:294–301.

Wu Z, Asokan A, Samulski RJ. Adeno-associated Virus Serotypes: Vector Toolkit for Human Gene Therapy. Mol Ther. 2006;14:316–27.

Aschauer DF, Kreuz S, Rumpel S. Analysis of Transduction Efficiency, Tropism and Axonal Transport of AAV Serotypes 1, 2, 5, 6, 8 and 9 in the Mouse Brain. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e76310.

Issa SS, Shaimardanova AA, Solovyeva VV, Rizvanov AA. Various AAV Serotypes and their applications in gene therapy: an overview. Cells. 2023;12:785.

Qin JY, Zhang L, Clift KL, Hulur I, Xiang AP, Ren BZ, et al. Systematic comparison of constitutive promoters and the doxycycline-inducible promoter. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10611.

Bohlen MO, McCown TJ, Powell SK, El-Nahal HG, Daw T, Basso MA, et al. Adeno-associated virus capsid-promoter interactions in the brain translate from rat to the nonhuman primate. Hum Gene Ther. 2020;31:1155–68.

Finneran DJ, Njoku IP, Flores-Pazarin D, Ranabothu MR, Nash KR, Morgan D, et al. Toward Development of Neuron Specific Transduction After Systemic Delivery of Viral Vectors. Front Neurol. 2021;12:685802.

Li L, Vasan L, Kartono B, Clifford K, Attarpour A, Sharma R, et al. Advances in Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus Vectors for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biomedicines. 2023;11:2725.

Wagner HJ, Weber W, Fussenegger M. Synthetic Biology: Emerging Concepts to Design and Advance Adeno-Associated Viral Vectors for Gene Therapy. Adv Sci. 2021;8:2004018.

Kolesnik VV, Nurtdinov RF, Oloruntimehin ES, Karabelsky AV, Malogolovkin AS. Optimization strategies and advances in the research and development of AAV-based gene therapy to deliver large transgenes. Clin Transl Med. 2024;14:e1607.

Arjomandnejad M, Dasgupta I, Flotte TR, Keeler AM. Immunogenicity of Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) Vectors for Gene Transfer. BioDrugs. 2023;37:311–29.

Marcello E, Chiono V. Biomaterials-Enhanced Intranasal Delivery of Drugs as a Direct Route for Brain Targeting. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:3390.

Chan KY, Jang MJ, Yoo BB, Greenbaum A, Ravi N, Wu WL, et al. Engineered AAVs for efficient noninvasive gene delivery to the central and peripheral nervous systems. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:1172–9.

Chen W, Yao S, Wan J, Tian Y, Huang L, Wang S, et al. BBB-crossing adeno-associated virus vector: An excellent gene delivery tool for CNS disease treatment. J Controlled Release. 2021;333:129–38.

Stanton AC, Lagerborg KA, Tellez L, Krunnfusz A, King EM, Ye S, et al. Systemic administration of novel engineered AAV capsids facilitates enhanced transgene expression in the macaque CNS. Med. 2023;4:31–50.e8.

Huang Q, Chen AT, Chan KY, Sorensen H, Barry AJ, Azari B, et al. Targeting AAV vectors to the central nervous system by engineering capsid–receptor interactions that enable crossing of the blood–brain barrier. PLoS Biol. 2023;21:e3002112.

Trevino JT, Quispe RC, Khan F, Novak V. Non-Invasive Strategies for Nose-to-Brain Drug Delivery. J Clin Trials. 2020;10:439.

Bhise S, Yadav A, Avachat A, Malayandi R. Bioavailability of intranasal drug delivery system. Asian J Pharm. 2008;2:201–15.

Illum L. Transport of drugs from the nasal cavity to the central nervous system. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2000;11:1–18.

Ye D, Chen H. Focused ultrasound-mediated intranasal brain drug delivery technique (FUSIN). MethodsX. 2021;8:101266.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants DP1DK143574, R01EB027223, R01EB030102, R01NS128461, and UG3MH126861. The funding sources had no involvement in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CC and HC conceptualized and designed the study; CC and JY conducted experiments and collected data under the supervision of HC; CC analyzed the data and interpreted the statistical results; CC wrote the paper; JY and HC reviewed and revised the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Washington University in St. Louis (Protocol NO. 24-0222) and conducted in compliance with the National Institute of Health (NIH) Guidelines for animal research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chukwu, C., Yuan, J. & Chen, H. Intranasal versus intravenous AAV delivery: A comparative analysis of brain-targeting efficiency and peripheral exposure in mice. Gene Ther (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41434-025-00585-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41434-025-00585-y