Abstract

The role of natural selection in shaping spatial patterns of genetic diversity in the Neotropics is still poorly understood. Here, we perform a genome scan with 24,751 probes targeting 11,026 loci in two Neotropical Bignoniaceae tree species: Handroanthus serratifolius from the seasonally dry tropical forest (SDTF) and Tabebuia aurea from savannas, and compared with the population genomics of H. impetiginosus from SDTF. OutFLANK detected 29 loci in 20 genes with selection signal in H. serratifolius and no loci in T. aurea. Using BayPass, we found evidence of selection in 335 loci in 312 genes in H. serratifolius, 101 loci in 92 genes in T. aurea, and 448 loci in 416 genes in H. impetiginosus. All approaches evidenced several genes affecting plant response to environmental stress and primary metabolic processes. The three species shared no SNPs with selection signal, but we found SNPs affecting the same gene in pair of species. Handroanthus serratifolius showed differences in allele frequencies at SNPs with selection signal among ecosystems, mainly between Caatinga/Cerrado and Atlantic Forest, while H. impetiginosus had one allele fixed across all populations, and T. aurea had similar allele frequency distribution among ecosystems and polymorphism across populations. Taken together, our results indicate that natural selection related to environmental stress shaped the spatial pattern of genetic diversity in the three species. However, the three species have different geographical distribution and niches, which may affect tolerances and adaption, and natural selection may lead to different signatures due to the differences in adaptive landscapes in different niches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Savannas and seasonally dry tropical forests (SDTF) are two of the most threatened ecosystems in the world due to agricultural expansion, harvesting for wood products and the increase of fire frequency due to agricultural practices (e.g., Miles et al. 2006; Collevatti et al. 2013). Most of the remaining areas of SDTFs are in the Neotropics, in South America (~54.2%), in Northeast and Central Brazil and in Southeast Bolivia, Paraguay and Northern Argentina (Dexter et al. 2018). Brazilian savanna is the most diverse savanna in the world and is considered one of the world’s hotspots of biodiversity (Myers et al. 2000). These seasonally dry vegetations, SDTFs and savannas, are corridors between two tropical rainforests, the Amazon and the Atlantic rainforests, and act as a barrier to the migration of species between these two rainforests, (see Prado and Gibbs 1993; Pennington et al. 2006). However, there might be routes for species migration, mainly via riparian forests (e.g., Ratter et al. 1997; Sobral-Souza et al. 2015; Souza-Neto et al. 2016; Cássia-Silva et al. 2020).

Species from both ecosystems, savannas and SDTFs, have undergone geographical distribution modifications during the Neogene and the Quaternary, affecting the spatial distribution of genetic diversity (see review in Collevatti et al. 2020). Overall, tree species from savannas had contractions and range shifts in their geographical distribution during glaciations, such as Tabebuia aurea (Collevatti et al. 2015), Handroanthus ochraceus (Vitorino et al. 2018), Qualea spp. (Buzatti et al. 2017), Caryocar brasiliense (Collevatti et al. 2015), Eugenia dysenterica (Lima et al. 2017), Byrsonima coccolobifolia (Resende-Moreira et al. 2017), and Dimorphandra mollis (Souza et al. 2017). SDTF species had a more variable response to glaciations. Handroanthus impetiginosus (Collevatti et al. 2012) and H. serratifolius (Vitorino et al. 2016), for instance, expanded their distribution during glaciation, whereas Tabebuia roseoalba had a contraction (Melo et al. 2016). The geographical distribution dynamics may have increased allele frequency in some new areas due to dispersal of genotypes at the edge of expansion (Hewitt 1996), as the species expanded tracking suitable environments. Allele surfing (Excoffier and Ray 2008; Arenas et al. 2013) and founder events may have caused gradients in genetic diversity due to demographic history (Excoffier et al. 2009; Waters et al. 2013).

The high differentiation among populations in species from savannas and SDTFs, the diverse spatial pattern in genetic diversity, and the lack of congruent biogeographical patterns mainly in species from SDTFs suggest that demographic history, and thus genetic drift, is likely not the only possible process driving spatial patterns (Kimura 1991). Spatial variation in the pattern of natural selection can lead to local adaptation and genetic differentiation among populations. Adaptation to spatially varying selective pressures is evident in the geographical distribution of many traits in plants (e.g., Joshi et al. 2001; Sakai and Larcher 2012). Savannas and SDTFs occur under a similar seasonal climate with a dry season during the winter (Pennington et al. 2006; Silva de Miranda et al. 2018). They differ notably in soil fertility and structure; while savannas are usually found over more ancient soils, dystrophic, with lower pH, and higher concentration of aluminum, SDTFs are usually found in eutrophic and oligotrophic soils with moderate pH and low levels of aluminum (Oliveira-Filho and Ratter 1995; Dexter et al. 2018). Thus, natural selection may also be shaping the current patterns and distribution of genetic variation associated with limited gene flow (Nadeau et al. 2016; Collevatti et al. 2019). Alternatively, adaptive selection with migration spreading favorable alleles among populations may lead to allele fixation (Yeaman and Whitlock 2011; Savolainen et al. 2013; Melo et al. 2020). However, confounding effects due to the spatial correlation of climatic gradients, geographical space and recolonization routes may hinder the disentangling of spatial patterns caused by neutral genetic drift and selection (Nadeau et al. 2016; Collevatti et al. 2019). Thus, unraveling the effects of demographic history and selection in extant genetic diversity is important to better understand the evolution of species distributions. A genome-wide scan analysis may help understanding the evolutionary processes underlying the genetic diversity and population differentiation, as we propose here.

Genome scans have been used to identify selection footprints in plants and animals, from temperate (Yeaman et al. 2016; Jordan et al. 2017; Thomaz and Knowles 2020), and tropical climates (Lanes et al. 2018; Collevatti et al. 2019; Brousseau et al. 2020; Melo et al. 2020). Target sequence capture has been increasingly used to genotype large numbers of markers because it significantly reduces costs and effort compared with whole-genome sequencing (Jones and Good 2016; Silva-Junior et al. 2018a; Andermann et al. 2019). Target sequencing has been applied successfully to study population genetic structure and adaptation in plants (e.g., Zhou and Holliday 2012; Syring et al. 2016; Loiseau et al. 2019; Collevatti et al. 2019; Melo et al. 2020). Recently, we generated genomic resources for the Neotropical tree Handroanthus impetiginosus, such as the genome assembly (Silva-Junior et al. 2018b), exome capture target-sequencing system (Silva-Junior et al. 2018a), population genomics analysis (Collevatti et al. 2019) and chloroplast genome assembly (Sobreiro et al. 2020). These genomic resources provided the opportunity to advance the understanding of evolutionary history, population demography and adaptation of Bignoniaceae species, an important family in Neotropical ecosystems and still largely neglected forest trees.

Here, we perform a comparative population genomics analysis of three phylogenetically related tree species from Bignoniaceae Tabebuia alliance (sensu Olmstead et al. 2009): H. impetiginosus, H. serratifolius, and T. aurea. This is a good clade to understand the roles of natural selection and genetic drift in shaping the genetic diversity and population differentiation because these phylogenetically related species are found in different habitats: SDTFs (H. impetiginosus and H. serratifolius) and savannas (T. aurea). The three species have similar pollination and seed dispersal systems. They are pollinated by large-size bees, such as bumblebees (Bombus spp.), carpenter bees (Xylocopa spp.) and Centris spp., and seeds are wind-dispersed. While H. impetiginosus and H. serratifolius are self-incompatible (Bittencourt and Semir 2005), T. aurea is self-compatible (Braga and Collevatti 2011). We expect that (i) the species from savanna has higher population differentiation than SDTF species due to the range retraction in the last glaciation. We expect that species from SDTF with more similar niches, geographical overlap (H. impetiginosus and H. serratifolius) and with similar response to Quaternary climate changes (range expansion), have similar spatial patterns of genetic differentiation due to genetic drift (ii). Similarly, we expect that SDTF species show higher number of SNPs with selection signature (iii), differences among ecosystems in allele frequencies in SNPs with selection signature (iv), and thus higher shifts in allele frequency between populations (v) than the savanna species (T. aurea), due to broader climatic and soil niche in SDTF species, and due to different responses of ecosystems to Quaternary climate changes. For this, we first evaluated the set of targeted sequencing probes developed for H. impetiginosus (Silva-Junior et al. 2018a) in H. serratifolius and T. aurea. Having confirmed the possibility to use these probes to sequence capture and SNP genotype, we then performed population genomics analysis of H. serratifolius and T. aurea to compare with published data of H. impetiginosus (Collevatti et al. 2019).

Material and methods

Population sampling

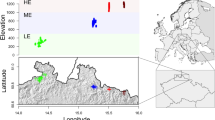

We sampled 16 populations (total of 144 individuals) of H. serratifolius across SDTFs in three ecosystems: Caatinga, Cerrado and Atlantic Forest (Fig. 1A and Appendix S1 Table S1). For T. aurea we sampled six populations (34 individuals) in savannas in the Cerrado, Pantanal, and Atlantic Forest ecosystems (Fig. 1B and Table S1). Handroanthus serratifolius has 2n = 80, with an estimated genome size of 1C = 0.68 Gb (Collevatti and Dornelas 2016). Due to their dense (1.08 g/cm3) rot-resistant woods, H. serratifolius and H. impetiginosus are the most logged timber in Brazil (Schulze et al. 2008). Tabebuia aurea has 2n = 40, with an estimated genome size of 1C = 0.60 Gb (Collevatti and Dornelas 2016). Adult individuals were georeferenced and their leaves were collected for DNA extraction using Qiagen DNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen, DK). For H. impetiginosus, we used the results based on the genotyping of 75,838 SNPs in 128 individuals across 13 populations published in Collevatti et al. (2019). We also extracted the SNP data to perform complementary analyses (see below).

A Geographical distribution of the 16 Handroanthus serratifolius populations sampled for genetic analyses and the Bayesian clustering of individuals based on 39,614 putatively neutral SNP loci, showing the best number of cluster K = 3. B Geographical distribution of the six Tabebuia aurea populations sampled for genetic analyses and the Bayesian clustering of individuals based on 5579 putatively neutral SNP loci, showing the best number of cluster K = 4. Each color represents the inferred cluster following the figure legends. The size of cluster chart section represents population co-ancestry for each cluster. The shape file of ecosystems was obtained from IBGE (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics) data base (https://www.ibge.gov.br/geociencias/informacoes-ambientais/15842-biomas.html).

SNP genotyping

All individuals of H. serratifolius and T. aurea were genotyped using the same set of probes of H. impetiginosus: 24,751 120-mer probe sequences targeting 11,026 distinct loci of the 30,271 predicted protein-coding genes across the genome assembly of H. impetiginosus (Silva-Junior et al. 2018a, b). Targeted DNA enrichment, capture, and sequencing were carried out by RAPiD Genomics LLC (Gainesville, CA) using SureSelectXT (Agilent Technologies, CA) enrichment system followed by Illumina Hiseq 2000 sequencing to generate paired-end 2 × 100-bp reads in one lane (detailed protocol in Neves et al. 2013, and Supplementary File S1).

All sequencing reads were trimmed for adapters and aligned to the genome sequence assembly of H. impetiginosus (Silva-Junior et al. 2018b) using BWA v. 0.5.9 (Li and Durbin 2009). SNP calling was carried out using GATK version 3.8 (McKenna et al. 2010) and CRISP version 3.7 (Bansal 2010). We followed the pipeline and analyzed parameters described in Collevatti et al. (2019), and details are in the Supplementary File S1.

To analyze probe transferability and common SNPs, we compared eight randomly selected individuals of H. impetiginosus (Collevatti et al. 2019), with eight individuals of H. serratifolius and T. aurea. We used the R package UpSetR v1.4.0 (Conway et al. 2017) to report the distribution of useful probes and SNPs genotyped across the set of species.

Genetic structure and demographic dynamics

We used the same framework applied for H. impetiginosus in Collevatti et al. (2019) allowing the comparison among the three species. We estimated genetic parameters using only putatively neutral loci. For this, we first removed SNPs that were detected as outliers by OutFLANK v.0.2 and BayPass v.2.2 (see below). Then, we analyzed the linkage equilibrium among putatively neutral loci using PLINK v1.90b6.16 (Purcell et al. 2007) and generate a pruned subset of SNPs (see details in Supplementary File S1). We obtained 39,614 putatively neutral SNPs for H. serratifolius, 3506 for H. impetiginosus, and 5579 SNPs for T. aurea. We calculated the number of polymorphic sites, expected heterozygosity under Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (He) and observed heterozygosity (Ho) and inbreeding coefficient (FIS). We performed a hierarchical AMOVA (prediction i) implemented in the software Arlequin 3.5 (Excoffier and Lischer 2010) to estimate the genetic differentiation among ecosystems (FCT) and among populations within ecosystems (FSC) and inbreeding coefficient (FIS) across all SNPs. We performed AMOVA analysis with and without populations with N < 3, but the results were equivalent. We also performed hierarchical AMOVA using only SNP loci with selection signal to compare the relative effects of genetic drift and selection in genetic structure.

Using these subsets of putatively neutral loci we performed a Bayesian clustering simulation (prediction ii) to access the number of genetic clusters (K) using the software fastSTRUCTURE v.1.0 (Raj et al. 2014). We run fastSTRUCTURE v.1.0 for each possible K, from 2 to16 in H. serratifolius, and 2 to 6 in T. aurea. To choose the best K value we used (Puechmaille 2016) method, implemented in Structure Selector website (Li and Liu 2018). We analyzed Structure Selector results using CLUMPAK v.1.1 software (Kopelman et al. 2015).

For the set of potentially neutral loci of the three species we analyzed whether populations are isolated by distance using a linear regression of linearized FST on the logarithm of geodesic geographic distance. We also performed an autocorrelation analysis with Moran’s I to understand the effect of spatial scale in genetic differentiation, using the software SAM v 4.0 (Spatial Analysis in Macroecology; Rangel et al. 2010).

Finally, to understand the role of genetic drift due to demographic dynamics we estimated the variation in population size of the three species using the pairwise sequentially Markovian coalescent (PSMC) model (Li and Durbin 2011) implemented in the R package PSMCR (https://github.com/emmanuelparadis/psmcr). We used the H. impetiginosus’ genome assembly (Silva-Junior et al. 2018b) as the reference genome. For each population and species, we run PSMCR using the following parameters: 30 iterations, 100 bootstrap replicates, 0.018 as the θ/ρ ratio, i.e., the ratio between the mutation parameter and the recombination rate, the pattern of 4 + 5 × 3 + 4 for the number of free atomic time interval, and maxt, i.e., the largest possible value for time to the most recent common ancestor, of 15 for H. impetiginosus, 20 for H. serratifolius and 100 for T. aurea.

Genome scans for selection footprints

To detect candidate loci under selection in H. serratifolius and T. aurea, and test predictions iii to v, we used two different methods in attempt to detect more loci under selection. We first used FST-based outlier analyses implemented in OutFLANK v.0.2 software (Whitlock and Lotterhos 2015) in R enviroment (https://github.com/whitlock/ OutFLANK). To run OutFLANK v.0.2 we selected only one SNP per probe to minimize linkage disequilibrium and removed SNPs for which all individuals were heterozygous, remaining 2266 loci in H. serratifolius, and 1298 loci in T. aurea (details in Supplementary File S1). We used the following parameters in OutFLANK: 5 and 10% left and right trim for the null distribution of FST, minimum heterozygosity for loci of 0.1, and 5% false discovery rate (q value).

Next, we used BayPass v.2.2 (Gautier 2015) to identify local selection by estimating linear correlations among allele frequencies and environmental variables, while controlling for relationships among populations. The environmental variables were selected from the WorldClim Global Climate database (www.worldclim.org/bioclim) with a spatial resolution of 30” for all populations sampled in the three species. We selected three bioclimatic variables using factorial analyses with Varimax rotation (details in Supplementary File S1) to avoid collinearity (Appendix S1 Tables S2 and S3).

We also obtained physical and chemical characteristics of topsoil (0–30 cm) and subsoil (30–100 cm) from the Harmonized World Soil Database version 1.2 (http://www.fao.org/3/aq361e/aq361e.pdf). Varimax factorial analysis (details in Supplementary File S1) selected five soil variables per species (Tables S3 and S5). For H. impetiginosus we used the climatic and soils variables selected in Collevatti et al. (2019).

To estimate the covariance matrix of allele frequencies among populations, we used 300 SNPs separated by at least 10 kb across all populations for each species using BayPass with 100,000 steps through the chain. We ran BayPass v.2.2 independently for each bioclimatic/soil variable with 1,000,000 iterations. Following the directions of BayPass v.2.2 manual, SNPs were considered candidates by having high approximated Bayesian p value in the log10 scale (eBFmc > 3).

For loci under selection detected by BayPass, we calculated the shifts in allele frequencies between pairs of populations, i.e., the difference between the allele frequency of the population with highest and lowest value for each climatic and soil variable and for each SNP locus (prediction v). For each variable, we obtained a vector of differences in allele frequency for the loci under selection and then we calculated the density function using the function density implemented in the stats package in R v. 3.6.3. (R Core Team 2019).

Candidate SNPs and annotation analysis

Putative SNP loci under selection were annotated with SNPEff v.4.3t (Cingolani et al. 2012) using H. impetiginosus reference genome (Silva-Junior et al. 2018b). If a SNP was annotated as being in the coding region of a gene and upstream of another, only the coding-sequence annotation was kept. Affected genes were analyzed for their functional annotation in terms of Gene Ontology (GO) categories (Ashburner et al. 2000) and UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org/). Then, we identified genes and GO terms shared by the three species. Finally, we mapped the allele frequencies of the genes with selection signal to find common spatial patterns in allele frequency distributions among ecosystems and populations (prediction iv).

Results

SNPs detection and genotyping

Handroanthus impetiginosus, H. serratifolius, and Tabebuia aurea shared 2475 probes that could capture SNPs in the three species (Appendix S2 Fig. S1), but only shared 361 SNPs (Fig. S2). Handroanthus impetiginosus and H. serratifolius shared a higher number of Probes (2083) and SNPs (1817) than with T. aurea (Figs. S1 and S2). See details of SNP detection and genotyping in Supplementary File S1.

Genetic structure and demographic dynamics

Mean genetic diversity among populations was similar for H. serratifolius and T. aurea (Table 1 and Appendix S1 Table S1), and slightly higher than for H. impetiginosus (He = 0.339, SD = 0.201).

The three species showed high genetic differentiation among ecosystems and populations. Handroanthus impetiginosus had higher differentiation among ecosystems (FCT = 0.313, p = 0.001) and among populations within ecosystems (FSC = 0.324, p = 0.001), and significant inbreeding (FIS = 0.100, p = 0.001), indicating higher frequency of mating between related individuals. For H. serratifolius, genetic differentiation among ecosystems (FCT = 0.116, p = 0.001) was similar to the differentiation among populations within ecosystems (FSC = 0.161, p = 0.001), and FIS was not significant (FIS = −0.387, p = 0.999). Tabebuia aurea showed similar pattern with high differentiation among populations from different ecosystems (FCT = 0.125, p = 0.052), and among populations within ecosystems (FSC = 0.101, p = 0.001). Inbreeding within populations was also not significant (FIS = −0.002, p = 0.522).

When genetic differentiation was analyzed based on SNPs with selection signal, we found lower differentiation among populations from different ecosystems for H. impetiginosus (FCT = 0.044, p = 0.001) than among populations within ecosystems (FSC = 0.261, p = 0.001). However, both H. serratifolius (FCT = 0.306, p = 0.001; FSC = 0.311, p = 0.001) and T. aurea (FCT = 0.268, p = 0.001; FSC = 0.132, p = 0.001) had higher genetic differentiation in regions under selection than for neutral loci.

Neutral genetic differentiation among pairs of populations was significantly, but poorly correlated to geographical distance for H. serratifolius (r2 = 0.071, p < 0.009, Appendix S2 Fig. S3a). Autocorrelation analysis showed a significant but weak relationship between genetic differentiation and geographical distance for populations up to ~322 km (r2 = 0.08, p = 0.003, Fig. S3b). For T. aurea, we found no significant correlation between genetic differentiation and geographical distance (r2 = 0.122, p = 0.226, Appendix S2 Fig. S4a), but autocorrelation showed a significant relationship up to ~480 km (r2 = 0.25, p = 0.045, Fig. S4b). Handroanthus impetiginosus showed no significant isolation-by-distance (r2 = 0.005, p = 0.179, Fig S5a, b).

Bayesian clustering analyses supported a higher number of independent genetic clusters in T. aurea (K = 4) than in H. serratifolius (K = 3) (Fig. 1 and Appendix S1 Tables S6 and S7; Appendix S2 Figs. S6 and S7). Handroanthus impetiginosus also showed four clusters (see Fig. 1 in Collevatti et al. 2019). The three species had a predominant southeast-northwest spatial differentiation among clusters, with one widespread cluster in the Cerrado ecosystem, but in H. serratifolius it was shared with Caatinga (Fig. 1). They had a different cluster in the Atlantic Forest, or in the transition between Cerrado and Atlantic Forest, agreeing with the high genetic differentiation across ecosystems based on the FCT. The analyses also recovered admixture within H. serratifolius’ populations from different ecosystems (Fig. 1A), similarly to H. impetiginosus (Fig. 1 in Collevatti et al. 2019) but low admixture among T. aurea’s populations (Fig. 1B).

PSMC recovered the demographic dynamics of H. impetiginosus (Fig. 2A) and H. serratifolius (Fig. 2B) from ~200 to ~10 ka, and T. aurea from the LGM (~21 ka) to 1 ka (Fig. 2C). Both H. impetiginosus and H. serratifolius showed higher effective population sizes during the last glaciation, followed by a decrease after the LGM. On the other hand, T. aurea showed an increase in effective population size after the end of the last glaciation. The sharp decrease in the Holocene (after c. 10 ka for SDTF species and c. 1 ka for T. aurea) is an artifact of the PSCM model may not reliably estimate recent changes in Ne (Mather et al. 2020).

Genome scan for selection footprints

We detected 29 loci with selection signal in H. serratifolius (Appendix S1 Table S8 and Appendix S2 Fig. S8) based on OutFLANK. These outlier loci were found in 22 different scaffolds with average FST = 0.690 (p < 0.001) and average He = 0.431. Outflank found 14 loci with the selection signal in H. impetiginosus (Collevatti et al. 2019) and no outlier loci in T. aurea (Table S9 and Fig. S9).

We recovered several SNPs correlated with environmental variables in the three species using BayPass. We found high eBFmc values, ranging from 3.05 to 15.35 (Appendix S2 Figs. S10–S15). BayPass detected 310 SNPs in H. impetiginosus via their correlation with climatic and 138 with soil variables (Appendix S1 Tables S10 and S11). In H. serratifolius, we found 127 loci for climatic variables (Table S12) and 208 loci for soil variables (Table S13). For T. aurea, we identified 46 loci with allele frequency correlated with climatic variables (Table S14) and 55 loci with soil variables (Table S15). OutFLANK and BayPass retrieved different SNPs with selection signature and SNPs in different probes for the three species.

Most loci under selection had small differences in allele frequency between populations with different climatic and soil conditions (Fig. 3), but T. aurea showed the highest shifts. Handroanthus impetiginosus showed higher shifts in SNPs with correlation with soil variables (Fig. 3A): subsoil calcium carbonate (CaCO3) and subsoil clay cationic exchange capacity (CEC Clay); while H. serratifolius showed higher shifts (Fig. 3B) for topsoil cationic exchange capacity (T_CEC), topsoil clay fraction, annual mean temperature (Bio1) and temperature annual range (Bio7). For T. aurea, SNPs with correlation with mean diurnal range (Bio2), precipitation seasonality (Bio15), subsoil base saturation (BS), calcium carbonate (CaCO3) and topsoil salinity (T_ECE) showed the highest shifts (Fig. 3C).

A Density plot for Handroanthus impetiginosus based on 448 loci with selection signature. B Density plot for Handroanthus serratifolius based on 335 loci with selection signature. C Density plot for Tabebuia aurea based on 101 loci with selection signature. A shift is defined as the difference between the allele frequencies of the population with the highest and the lowest value for each climatic and soil variable. Variables are: Bio01, mean annual temperature; Bio2, mean diurnal Range (mean of monthly (max temp–min temp); Bio4, temperature seasonality; Bio5, maximum temperature of the warmest month; Bio7, temperature annual range; Bio10, mean temperature of the warmest quarter; Bio12, annual precipitation; Bio15, precipitation seasonality; Bio16, precipitation of the wettest quarter; Bio17, precipitation of the driest quarter; CEC, clay cationic exchange capacity; T_CaCO3, toposoil calcium carbonate concentration; BS, subsoil base saturation; S_GRAVEL, subsoil gravel content; CASO4, topsoil gypsum; T_CEC, topsoil CEC; T_CLAY, topsoil clay fraction; T_PH_H2O, topsoil pH (H2O); S_CACO3, subsoil calcium carbonate; S_REF_BULK_DENSITY, subsoil reference bulk density; T_ECE, topsoil salinity.

Functional annotation of SNPs with selection signal

For the 448 SNPs with selection signature found in H. impetiginosus based on BayPass, SNPEff annotation suggested 416 genes that were potentially affected by these SNPs. Specifically correlated to the four climate variables, we found 310 SNPs potentially affecting 307 genes. From these SNPs, 195 were within the genes transcribed regions and the remaining SNPs were found down or upstream, between genes or in the 3′/5′ prime UTR region (Table S10). For three soil variables, BayPass indicated 138 SNPs potentially affecting 138 genes (Table S11). Within coding regions SNPEff indicated 86 SNPs, and outside the genes coding regions 53 SNPs were found. GO annotation indicated a wide spectrum of functions including response to bacterium (CDL12_02600) and ovule development (CDL12_23705). In H. impetiginosus, BayPass detected one common gene with OutFLANK (Collevatti et al. 2019), CDL12_11669, related to DNA transcription.

Among the 29 outlier SNPs identified by OutFLANK in H. serratifolius, only one was outside the transcribed region of the annotated genes. Based on the SNPEff annotation, the remaining 28 SNPs (~97%) potentially affect the expression of 20 different genes (Appendix S1 Table S16). GO annotation of these 20 genes pointed to a wide spectrum of biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components (Table S16).

The SNPEff annotation of the 335 SNPs detected with BayPass in H. serratifolius indicated that 312 genes were potentially affected by these SNPs. The 127 loci correlated with climate variables were found within or near 124 genes. Most SNPs (93 of 127; ~73%) affected a gene within their transcribed regions (exons and introns; Table S12), while 34 SNPs (27%) affected one or two genes outside the transcribed region. The 208 SNPs correlated with soil variables potentially affected 188 genes (Table S13). From these SNPs, 158 (~84%) were within exons or introns in genes. The remaining SNPs were found at 5′ or 3′ UTR (15 SNPs), up or downstream of the transcribed region (20 SNPs) and at intergenic regions (15 SNPs). GO annotation of the 312 genes potentially affected by the 335 SNPs with putative signals of adaptive selection revealed their involvement in a wide spectrum of underlying molecular functions, biological processes, and cellular components (Table S13). OutFLANK and BayPass detected selection in SNPs affecting the same genes for CDL12_18396 (response to abiotic stress), CDL12_01901 (unnamed protein) and CDL12_06047 (auxin response).

Among the 101 SNPs detected in T. aurea based on BayPass, 46 were correlated with at least one of the selected climate variables, 54 with soil variables, and eight with both climate and soil variables. SNPEff annotation of these SNPs indicated that 92 genes are potentially affected by these variations at the DNA level. The 46 loci correlated with climate variables were found within or near 46 different genes (Table S14). From these loci, 39 affected genes at their transcribed region (exons, introns, or splice region). Most of the remaining SNPs were found in intergenic regions and one at 5′ UTR.

The 55 SNPs correlated with soil variables potentially affect 54 genes in T. aurea (Table S15). From the SNPs, 41 were within gene’s exons (~76%), four (~7%) within introns and splice regions. The remaining SNPs were found outside the transcribed region or between genes. GO annotation of the 54 genes potentially affected by the 55 SNPs with putative signals of adaptive selection revealed their involvement in molecular functions, biological processes and cellular components (Table S15).

Most SNPs were found within gene transcribed region in the three species (Fig. 4). Within gene transcribed regions, almost all mutations had low, i.e., is a synonymous variant unlikely to change protein behavior, or moderate putative effects, i.e., is a missense variation or in frame deletion that might change protein effectiveness, independent of the GO category (Fig. 4). In untranscribed regions, most mutations had a modifier putative effect, i.e., variants affecting non-coding genes, where predictions are difficult or there is no evidence of impact (Fig. 4).

The strength of putative functional effects are: Low, is a synonymous variant unlikely to change protein behavior. Moderate, a missense (nonsynonymous) variation or a frame deletion that might change protein effectiveness. High, a stop or frameshift variant, probably causing protein truncation, loss of function or triggering nonsense mediated decay. Modifier, variants affecting non-coding genes, where predictions are difficult or there is no evidence of impact.

We found genes potentially affected by SNPs that were classified with the GO category of transcription factors (BZIP and C2H2 Zinc Finger) related to abiotic stress (Han et al. 2020) and genes involved in signal transduction (Serine/Threonine kinase and Rab3 GTPase-activating protein). Although the species shared no SNPs with selection signature, we found SNPs with selection signal affecting the same gene in species pairs (Table S17), involved in nucleic acid and protein binding function. Handroanthus impetiginosus showed higher number of affected genes in SNPs with selection footprints, followed by H. serratifolius and T. aurea.

Overall, H. impetiginosus had an allele fixed in almost all populations at SNPs with selection footprints (Fig. 5). Nevertheless, a few loci were polymorphic, but without a clear spatial pattern, such as CDL12_02600 (Fig. 5A), a gene related to plant response to bacteria. In Handroanthus serratifolius several loci showed remarkable difference in allele frequency among ecosystems, also evinced by high FCT, mainly between Caatinga/Cerrado and Atlantic Forest (Fig. 6). In T. aurea, overall, the SNP loci were polymorphic and had no clear spatial pattern in allele frequency distribution among or within ecosystems (Cerrado, Pantanal, and Atlantic Forest, Fig. 7).

A Gene related to a protein involved in hypersensitive response to bacteria. B Gene related to a protein involved in the response to oxidative stress. C Gene related to a protein involved in the response to fungi. D Gene related to a protein involved in the response to osmotic stress. In orange the reference allele and in purple the alternative allele.

Discussion

We found adequate probe transferability between H. impetiginosus and the other two species of the Tabebuia alliance. Handroanthus serratifolius revealed SNPs for the majority of the probes (13,796) while T. aurea showed a lower number of probes containing SNPs (4921). Even though these results may change with larger sample sizes, they are consistent with the increasing phylogenetic distance of these species from H. impetiginosus (Grose and Olmstead 2007a, b). This is expected given the long time (c. 25 Mya, see Collevatti et al. 2012, 2015) since the species diverged from their common ancestor. In addition, most SNPs have a low minor allele frequency (MAF < 0.15), indicating that they might be more recent than the time since the species diverged.

Our results highlight the power of the sequence capture approach for SNP genotyping across a species complex. While sampling different sets of SNPs in different species was expected, the possibility of using the same set of sequence capture probes for high density SNP genotyping across these relatively distant species will constitute an excellent resource for refined genome-wide population genomics studies in the Tabebuia alliance.

High neutral admixture among ecosystems

Our results show high neutral genetic differentiation among ecosystems evidenced by both, Bayesian clustering (see Fig. 1) and AMOVA. Contrary to our expectations (i), that species from savanna has higher population differentiation than SDTF species, they had similar genetic differentiation (FCT). However, H. serratifolius and H. impetiginosus showed similar spatial pattern of genetic differentiation following our prediction (ii) due to admixture among ecosystems, especially Cerrado and Caatinga, and Cerrado and Atlantic Forest. Tabebuia aurea, on the other hand, had low admixture among ecosystems or populations within ecosystems.

Our results contrast with previous work based on nuclear microsatellite loci (Collevatti et al. 2014) that retrieved low genetic differentiation among populations of T. aurea based on FST (0.006). However, genetic differentiation was high based on stepwise-mutation model (RST = 0.209) and Bayesian clustering showed a higher number of genetic groups (K = 19). The differences may be due to sampling size, since the present work used a subset of the populations studied in (Collevatti et al. 2014, 2015). Differences are also likely due to evolutionary rates. SNP and microsatellite markers evolve differently and, therefore, reveal different evolutionary timescales. As microsatellites evolve faster, they should indicate more recent evolutionary processes compared to the SNP markers. Chloroplast (FST = 0.773) and nuclear ribosomal DNA (nrDNA ITS, FST = 0.966) sequencing showed high differentiation among populations (Collevatti et al. 2015). Genetic differentiation among populations within ecosystems for H. serratifolius was high, following the high differentiation in nrDNA ITS (ΦST = 0.742) and chloroplast intergenic spacers (ΦST = 0.528) (Vitorino et al. 2016).

The differences may also be due to demographic history, i.e., the dynamics in effective population size throughout the Quaternary. While T. aurea had a predicted range and demographic retraction during the LGM, followed by an expansion in the Holocene (Collevatti et al. 2014, 2015), H. serratifolius expanded its geographical distribution in the LGM increasing the effective population size (Vitorino et al. 2016), similar to H. impetiginosus (Collevatti et al. 2012), leading to admixture. Our results also show an increase in effective population size during the mid-Holocene for T. aurea, and retraction for both H. serratifolius and H. impetiginosus, matching the forecast based on ecological niche modeling. Because favorable climatic conditions for T. aurea (i.e., hot and drier climates, see Collevatti et al. 2014) were spatially more restricted during glacial than interglacial periods in the Neotropics, smaller effective population size during the cold phases of the last glacial cycle was a consequence of the retraction in geographical range leading to high differentiation in the SNPs loci (predictions i and ii), chloroplast and nrDNA, that evolve under infinite sites model, with lower mutation rates.

Moreover, we found week evidence of isolation-by-distance. The three species are bee-pollinated and seeds are wind-dispersed which may promote long-distance dispersal leading to connectivity among populations (Collevatti et al. 2012, 2014; Vitorino et al. 2016). Taken together, our results support the demographic dynamics during the Quaternary as an important driver of spatial patterns in genetic diversity and differentiation in the three species.

Local selection may lead to differences in allele frequency among ecosystems

Our findings show evidence of selection footprints in H. serratifolius and T. aurea in several SNP loci. Sampling across different ecosystems, we found 364 SNPs with selection footprints in H. serratifolius and 101 in T. aurea. In H. impetiginosus, besides the 14 outlier loci detected using OutFLANK in Collevatti et al. (2019), we could detect an additional 448 loci using BayPass. OutFLANK and BayPass methods detected different SNP loci with selection signals, although a few SNPs were in the same gene. It is important to highlight that BayPass could detect a higher number of loci with selection signal than the software Bayenv2 (Günther and Coop 2013), increasing our ability of detecting selection. For instance, Bayenv2 detected a much lower number of SNP loci with selection signature in H. impetiginosus (32, Collevatti et al. 2019), and in a preliminary analysis we found only 37 loci in H. serratifolius and 45 in T. aurea.

Despite the high phylogenetic relationship among the three species, we found no common SNPs with selection signature between pair of species, although we found different SNPs in the same gene. It is also noteworthy that we found a higher number of SNPs with selection footprints in H. impetiginosus and H. serratifolius from SDTFs than in T. aurea from savanna, following our expectations (iii), although this may also be due to genome sampling, because of the lower number of SNP loci genotyped in T. aurea.

We also found evidences that phylogenetically related species have different selection signatures. The three species showed different spatial pattern in allele frequency distribution among ecosystems, but not following our prediction of higher differences among ecosystems in SDTF species (iv), most likely due to the selection signal in different genes and demographic history. Despite the overlap in geographical distribution between the SDTF species, the three species have different niches, which may affect tolerances and adaptation. Natural selection may lead to different signatures due to the differences in adaptive landscapes in different niches (Laughlin and Messier 2015). Handroanthus impetiginosus is widely distributed in SDTFs in South and Mesoamerica, under a broad climatic conditions and soil fertility, occurring in a wide range of soil cationic exchange capacity, pH and BS (Collevatti et al. 2012, 2019). Handroanthus serratifolius occurs mainly in rain forests and riparian forests, but can also be found in SDTFs, under wide variation in precipitation and soil fertility (Vitorino et al. 2016), being more generalist (broader climatic and soil niches) than H. impetiginosus. Tabebuia aurea is more adapted to hot and drier climates than the former species. In addition, T. aurea has narrower niche breadth for annual precipitation and temperature than the two Handroanthus species (Collevatti et al. 2014), although it may be found in different local habitats such as seasonally dry and seasonally wet savannas.

In H. serratifolius, we found high differentiation among ecosystems in allele frequency for most SNPs with selection footprints, especially in Atlantic Forest and Cerrado/Caatinga, also evidenced by the high FCT. In fact, Atlantic Forest is a rainforest ecosystem and Cerrado and Caatinga are seasonally dry ecosystems. Thus, the climatic conditions, and soil structure and fertility are highly different in these ecosystems, possibly leading to the selection of different alleles. Population SCA from Cerrado had similar allele frequencies to populations from Atlantic Forest. This population is in the southeast edge of Cerrado, in the transition between Cerrado and Atlantic Forest ecosystems, which may explain the higher similarity of SCA with populations from Atlantic Forest than Cerrado.

It is important to note that the spatial pattern in allele frequency in several SNPs with selection footprints is highly similar to the distribution of genetic clusters of putatively neutral loci in H. serratifolius (see Figs. 1 and 6), and a few loci have similar allele frequencies among ecosystems and populations. We hypothesize that the high historical connectivity among populations, due to range expansion in glacial periods (Vitorino et al. 2016) may have spread favorable alleles among populations leading to allele sharing (see Yeaman and Whitlock 2011; Savolainen et al. 2013). The spread of favorable alleles due to range expansion in glacial periods (Collevatti et al. 2012) may also explain the spatial distribution in allele frequency in H. impetiginosus, with an allele fixed in almost all populations (Fig. 5) and low FCT based on SNPs with selection footprints.

For T. aurea, we found differences in allele frequencies at SNPs with selection footprints between Atlantic Forest, Cerrado, and Pantanal, but no allele fixation (Fig. 7). Most populations are polymorphic for loci under selection. In fact, we found higher shifts in allele frequency between contrasting environments in the savanna species, T. aurea, than in SDTF species, the opposite of our prediction that SDF species would have higher shifts (v). The shifts in allele frequency distributions among contrasting environments for most loci in T. aurea, together with the polymorphism within and among populations from the same ecosystem suggest balanced selection maintaining genetic diversity across populations. In addition, new mutations can be maintained in different populations because of parallel adaptation, i.e., mutations that lead to similar phenotypes (Arendt and Reznick 2008) maintaining genetic diversity (Messer and Petrov 2013). Moreover, climatic changes leading to cycles of range expansion and retraction through time in T. aurea may have changed the adaptive landscape through time. Neutral or deleterious alleles may become beneficial in different populations under different environmental conditions increasing genetic diversity (Przeworski et al. 2005).

Evidences of selection were detected in genes related to response to environment stress

Some SNPs with selection signature affected constitutive genes, involved in the maintenance of primordial cellular functions (housekeeping genes), related to processes of DNA and RNA replication, regulation, and protein processing. Nevertheless, we found several SNPs with selection footprints in genes related to adaptation to biotic and abiotic stress evidencing local selection in the three species. Examples include the late embryogenesis abundant proteins which are induced in response to cellular dehydration in many organisms (Magwanga et al. 2018), as well as genes involved in signal transduction such as serine/threonine kinases.

Handroanthus serratifolius occurs across highly variable macroclimatic conditions, from the humid Atlantic and Amazon Forests to the seasonally dry Cerrado savanna, the semi-arid Caatinga, but always associated with forests and moist microhabitats. The genome scan detected several SNPs affecting genes related to plant response to stress, growth, and seed and plant development, and also transcription factors related to plant response to biotic or abiotic stresses. For instance, we identified selection signals in the GRAS domain-containing protein (CDL12_03605, Fig. 6A). GRAS proteins act as transcription factors that regulate diverse processes in root and shoot development, gibberellic acid signaling and phytochrome A signal transduction (Hirsch and Oldroyd 2009). We also detected the LRR-containing protein in H. serratifolius related to auxin-activated signaling pathway gene (CDL12_08761, Fig. 6B) that affects several processes of plant development, such as cell division, elongation, and differentiation, and physiological processes (Teale et al. 2006; Lau et al. 2008). Another SNP correlated to climatic variables affect the methionine-S-oxide reductase protein (CDL12_16963, Fig. 6C), which is related to plant response to oxidative stress conditions, and environmental constraints leading to osmotic stress such as drought, high salt concentration, and low temperature (Rey and Tarrago 2018). Adaptin N-terminal region protein (CDL12_18396, Fig. 6D) has SNP with selective signal and is involved in floral organ development, acting in clathrin-mediated endocytosis for the regulation of phytohormone signaling during floral organ development (Yamaoka et al. 2013).

Tabebuia aurea occurs across highly variable microclimatic conditions, associated to seasonally dry savannas or seasonally wet savannas, such as in Pantanal (population CAC), and on islands of savanna remnants in semi-arid biome such as Caatinga. In this species, we found selection signal in a SNP affecting the translational repressor Pumilio/PUF3 gene (CDL12_03401, Fig. 7A). This gene down-regulates translation under oxidative stress (Rowe et al. 2014). This SNP is correlated to mean diurnal temperature range and soil BS. The SNP affecting the Rab3 GTPase-activating protein (CDL12_12992, Fig. 7B) is correlated with both climatic (mean diurnal temperature range) and soil (CaCO3) variables, reinforcing its importance in local selection in T. aurea. This gene is related to intracellular membrane trafficking by organizing the biogenesis, transport, biding, and fusion of membrane-bound organelles and vesicles, endosome organization, cytokinesis, post-Golgi traffic to the plasma membrane and vacuoles, and may play important role in biotic and abiotic stress (Fukuda 2008; Agarwal et al. 2009). The SNP related to the C2H2-type domain-containing protein (CDL12_16543, Fig. 7C) was correlated to both climatic (precipitation seasonality) and soil (CaCO3) variables. This gene belongs to the zinc-finger protein genes, one of the largest transcription factor families in plants, and play important roles in abiotic stress resistance (Han et al. 2020). The SNP associated with a gene that codes for the LRR-containing protein (CDL12_25674, Fig. 7D), also had selection signal correlated to the mean diurnal temperature range. The LRR-containing protein family has several functions such as the control of membrane homeostasis under phosphate deprivation conditions (Block et al. 2007), and is involved in plant development and perception of environmental condition or stresses (Dufayard et al. 2017).

In fact, T. aurea is less responsive to drought stress at the transcriptional level, compared with H. serratifolius or H. impetiginosus (Sobreiro et al. 2021), most likely due to a more developed root system in trees from savannas compared to trees from forests (Hoffmann and Franco 2003; Hoffmann et al. 2004). We hypothesize that the species may experience less drought stress due to the anatomical adaptations of roots, but also due to polymorphisms in genes related to the response to abiotic stress, allowing local adaptation. In addition, T. aurea show adaptation to drought stress via molecular plasticity in leaf osmotic control (Sobreiro et al. 2021). On the other hand, H. serratifolius has high molecular plasticity to drought stress, displaying high number of DEGs (differentially expressed genes). We also found evidence of local selection in several SNPs in this species with higher differentiation in allele frequency among different ecosystems, which is expected for a species occurring in a broad range of macroclimatic conditions.

Concluding remarks

Our results point to the local selection in H. serratifolius and T. aurea, in SNP loci affecting genes related to basic metabolic processes or housekeeping functions that are likely under strong purifying selection (Siol et al. 2010), and genes related to plant response to environmental stress. Considering the number of loci genotyped for each species and the transcriptome size of H. impetiginosus (nearly 32k genes; Silva-Junior et al. 2018b), the number of loci with selection signature was relatively low, although we could detect more loci than in Collevatti et al. (2019) using a different method. The available methods to detect adaptive selection are based on the assumption that positive selection on a mutation leads to hard selective sweeps, and therefore have little power to detect other types of selection such as background and balancing selection (Przeworski et al. 2005; Nielsen 2005; Messer and Petrov 2013). Thus, it is possible that our methodology allowed detection of only a fraction of loci under selection, at a few specific loci that were within the detectable level of our sample size and confounding genetic structure background. Adaptive traits are mostly under polygenic control (Pritchard and Di Rienzo 2010) involving many loci with small effects, and are likely subject to stabilizing selection toward an intermediate optimum (Fisher 1930; Wright 1935).

Data availability

Additional data are provided as supporting information in the online version of this article. DNA datasets are available in GeneBank database (https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA784695?reviewer=fnms7m8ign29phdm5r7dd7jnr4).

References

Agarwal P, Reddy MK, Sopory SK, Agarwal PK (2009) Plant rabs: Characterization, functional diversity, and role in stress tolerance. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 27:417–430

Andermann T, Torres Jiménez MF, Matos-Maraví P, Batista R, Blanco-Pastor JL, Gustafsson ALS et al. (2019) A guide to carrying out a phylogenomic target sequence capture project. PeerJ Prepr 10:1–20

Arenas M, François O, Currat M, Ray N, Excoffier L (2013) Influence of admixture and paleolithic range contractions on current European diversity gradients. Mol Biol Evol 30:57–61

Arendt J, Reznick D (2008) Convergence and parallelism reconsidered: what have we learned about the genetics of adaptation? Trends Ecol Evol 23:26–32

Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM et al. (2000) Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet 25:25–29

Bansal V (2010) A statistical method for the detection of variants from next-generation resequencing of DNA pools. Bioinformatics 26:318–i324

Bittencourt NS, Semir J (2005) Late-acting self-incompatibility and other breeding systems in Tabebuia (Bignoniaceae). Int J Plant Sci 166:493–506

Block MA, Douce R, Joyard J, Rolland N (2007) Chloroplast envelope membranes: A dynamic interface between plastids and the cytosol. Photosynth Res 92:225–244

Braga AC, Collevatti RG (2011) Temporal variation in pollen dispersal and breeding structure in a bee-pollinated Neotropical tree. Heredity 106:911–919

Brousseau L, Fine PVA, Dreyer E, Vendramin GG, Scotti I (2020) Genomic and phenotypic divergence unveil microgeographic adaptation in the Amazonian hyperdominant tree Eperua falcata Aubl. (Fabaceae). Mol Ecol 30:1136–1154

Buzatti RS, de O, Lemos-Filho JP, Bueno ML, Lovato MB (2017) Multiple Pleistocene refugia in the Brazilian cerrado: evidence from phylogeography and climatic nichemodelling of two Qualea species (Vochysiaceae). Bot J Linn Soc 185:307–320

Cássia-Silva C, Cianciaruso MV, Dias PA, Freitas CG, Souza-Neto AC, Collevatti RG (2020) Among cradles and museums: seasonally dry forest promotes lineage exchanges between rain forest and savanna. Plant Ecol Divers 13:1–13

Cingolani P, Platts A, Wang LL, Coon M, Nguyen T, Wang L et al. (2012) A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly (Austin) 6:80–92

Collevatti RG, Dornelas MC (2016) Clues to the evolution of genome size and chromosome number in Tabebuia alliance (Bignoniaceae). Plant Syst Evol 302:601–607

Collevatti RG, Estolano R, Ribeiro ML, Rabelo SG, Lima EJ, Munhoz CBR (2014) High genetic diversity and contrasting fine-scale spatial genetic structure in four seasonally dry tropical forest tree species. Plant Syst Evol 300:1671–1681

Collevatti RG, Novaes E, Silva-Junior OB, Vieira LD, Lima-Ribeiro MS, Grattapaglia D (2019) A genome-wide scan shows evidence for local adaptation in a widespread keystone Neotropical forest tree. Heredity 123:117–137

Collevatti RG, dos Santos JS, Rosa FF, Amaral TS, Chaves LJ, Ribeiro MC (2020) Multi-scale landscape influences on genetic diversity and adaptive traits in a neotropical savanna tree. Front Genet 11:1–14

Collevatti RG, Terribile LC, Lima-Ribeiro MS, Nabout JC, De Oliveira G, Rangel TF et al. (2012) A coupled phylogeographical and species distribution modelling approach recovers the demographical history of a Neotropical seasonally dry forest tree species. Mol Ecol 21:5845–5863

Collevatti RG, Terribile LC, de Oliveira G, Lima-Ribeiro MS, Nabout JC, Rangel TF et al. (2013) Drawbacks to palaeodistribution modelling: the case of South American seasonally dry forests (R Pearson, Ed.). J Biogeogr 40:345–358

Collevatti RG, Terribile LC, Rabelo SG, Lima-Ribeiro MS (2015) Relaxed random walk model coupled with ecological niche modeling unravel the dispersal dynamics of a Neotropical savanna tree species in the deeper Quaternary. Front Plant Sci 6:653

Conway JR, Lex A, Gehlenborg N (2017) UpSetR: An R package for the visualization of intersecting sets and their properties. Bioinformatics 33:2938–2940

Dexter KG, Pennington RT, Oliveira-Filho AT, Bueno ML, Silva de Miranda PL, Neves DM (2018) Inserting tropical dry forests into the discussion on biome transitions in the tropics. Front Ecol Evol 6:1–7

Dufayard JF, Bettembourg M, Fischer I, Droc G, Guiderdoni E, Périn C et al. (2017) New insights on Leucine-rich repeats receptor-like kinase orthologous relationships in angiosperms. Front Plant Sci 8:1–18

Excoffier L, Foll M, Petit RJ (2009) Genetic consequences of range expansions. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 40:481–501

Excoffier L, Lischer HEL (2010) Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol Ecol Resour 10:564–567

Excoffier L, Ray N (2008) Surfing during population expansions promotes genetic revolutions and structuration. Trends Ecol Evol 23:347–351

Fisher RA (1930) The genetical theory of natural selection. Claredon Press, Oxford

Fukuda M (2008) Membrane traffic in the secretory pathway: regulation of secretory vesicle traffic by Rab small GTPases. Cell Mol Life Sci 65:2801–2813

Gautier M (2015) Genome-wide scan for adaptive divergence and association with population-specific covariates. Genetics 201:1555–1579

Grose SO, Olmstead RG (2007a) Taxonomic revisions in the polyphyletic genus Tabebuia s. l. (Bignoniaceae). Syst Bot 32:660–670

Grose SO, Olmstead RG (2007b) Evolution of a charismatic neotropical clade: molecular phylogeny of Tabebuia s. l., Crescentieae, and Allied Genera (Bignoniaceae). Syst Bot 32:650–659

Günther T, Coop G (2013) Robust identification of local adaptation from allele frequencies. Genetics 195:205–220

Han G, Lu C, Guo J, Qiao Z, Sui N, Qiu N et al. (2020) C2H2 Zinc finger proteins: master regulators of abiotic stress responses in plants. Front Plant Sci 11:1–13

Hewitt GM (1996) Some genetic consequences of ice ages, and their role in divergence and speciation. Biol J Linn Soc 58:247–276

Hirsch S, Oldroyd GED (2009) GRAS-domain transcription factors that regulate plant development. Plant Signal Behav 4:698–700

Hoffmann WA, Franco AC (2003) Comparative growth analysis of tropical forest and savanna woody plants using phylogenetically independent contrasts. J Ecol 91:475–484

Hoffmann WA, Orthen B, Franco AC (2004) Constraints to seedling success of savanna and forest trees across the savanna-forest boundary. Oecologia 140:252–260

Jones MR, Good JM (2016) Targeted capture in evolutionary and ecological genomics. Mol Ecol 25:185–202

Jordan R, Hoffmann AA, Dillon SK, Prober SM (2017) Evidence of genomic adaptation to climate in Eucalyptus microcarpa: implications for adaptive potential to projected climate change. Mol Ecol 26:6002–6020

Joshi J, Schmid B, Caldeira MC, Dimitrakopoulos PG, Good J, Harris R et al. (2001) Local adaptation enhances performance of common plant species. Ecol Lett 4:536–544

Kimura M (1991) The neutral theory of molecular evolution: a review of recent evidence. Jpn J Genet 66:367–386

Kopelman NM, Mayzel J, Jakobsson M, Rosenberg NA, Mayrose I (2015) Clumpak: a program for identifying clustering modes and packaging population structure inferences across K. Mol Ecol Resour 15:1179–1191

Lanes ÉC, Pope NS, Alves R, Carvalho Filho NM, Giannini TC, Giulietti AM et al. (2018) Landscape genomic conservation assessment of a narrow-endemic and a widespread morning glory from amazonian savannas. Front Plant Sci 9:532

Lau S, Jürgens G, De Smet I (2008) The evolving complexity of the auxin pathway. Plant Cell 20:1738–1746

Laughlin DC, Messier J (2015) Fitness of multidimensional phenotypes in dynamic adaptive landscapes. Trends Ecol Evol 30:487–496

Li H, Durbin R (2009) Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25:1754–1760

Li H, Durbin R (2011) Inference of human population history from individual whole-genome sequences. Nature 475:493–496

Li YL, Liu JX (2018) StructureSelector: a web-based software to select and visualize the optimal number of clusters using multiple methods. Mol Ecol Resour 18:176–177

Lima JS, Telles MPC, Chaves LJ, Lima-Ribeiro MS, Collevatti RG (2017) Demographic stability and high historical connectivity explain the diversity of a savanna tree species in the Quaternary. Ann Bot 119:645–657

Loiseau O, Olivares I, Paris M, de La Harpe M, Weigand A, Koubínová D et al. (2019) Targeted capture of hundreds of nuclear genes unravels phylogenetic relationships of the diverse neotropical palm tribe geonomateae. Front Plant Sci 10:1–16

Magwanga RO, Lu P, Kirungu JN, Lu H, Wang X, Cai X et al. (2018) Characterization of the late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) proteins family and their role in drought stress tolerance in upland cotton. BMC Genet 19:1–31

McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A et al. (2010) The genome analysis toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res 20:1297–1303

Melo WA, Lima-Ribeiro MS, Terribile LC, Collevatti RG (2016) Coalescent simulation and paleodistribution modeling for Tabebuia rosealba do not support south American dry forest refugia hypothesis. PLoS ONE 11:1–23

Melo WA, Vieira LD, Novaes E, Bacon CD, Collevatti RG (2020) Selective Sweeps Lead to Evolutionary Success in an Amazonian Hyperdominant Palm. Front Genet 11:1–14

Messer PW, Petrov DA (2013) Population genomics of rapid adaptation by soft selective sweeps. Trends Ecol Evol 28:659–669

Mather N, Traves SM, Ho SYW (2020) A pratical introduction to sequenctially Markovian coalescent methods for estimating demographic history from genomic data. Ecol Evol 10:579–589

Miles L, Newton AC, DeFries RS, Ravilious C, May I, Blyth S, et al. (2006) A global overview of the conservation status of tropical dry forests. J Biogeogr 33:491–505

Myers N, Mittermeler RA, Mittermeler CG, Da Fonseca GAB, Kent J (2000) Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403:853–858

Nadeau S, Meirmans PG, Aitken SN, Ritland K, Isabel N (2016) The challenge of separating signatures of local adaptation from those of isolation by distance and colonization history: the case of two white pines. Ecol Evol 6:8649–8664

Neves LG, Davis JM, Barbazuk WB, Kirst M (2013) Whole-exome targeted sequencing of the uncharacterized pine genome. Plant J 75:146–156

Nielsen R (2005) Molecular signatures of natural selection. Annu Rev Genet 39:197–218

Oliveira-Filho AT, Ratter JA (1995) A study of the origin of central brazilian forests by the analysis of plant species distribution patterns. Edinb J Bot 52:141–194

Olmstead RG, Zjhra ML, Lohmann LG, Grose SO, Eckert AJ (2009) A molecular phylogeny and classification of Bignoniaceae. Am J Bot 96:1731–1743

Pennington TR, Lewis G, Ratter J (2006) An overview of the plant diversity, biogeography and conservation of neotropical savannas and seasonally dry forests. In: Pennington RT, Lewis GP, Ratter JA (eds.) Neotropical Savannas and the seasonally dry forests, Vol 01. CRC Press, Boca Raton, p 1–29

Prado DE, Gibbs PE (1993) Patterns of species distributions in the dry seasonal forests of South America. Ann Mo Bot Gard 80:902–927

Pritchard JK, Di Rienzo A (2010) Adaptation—not by sweeps alone. Nat Rev Genet 11:665–667

Przeworski M, Coop G, Wall JD (2005) The signature of positive selection on standing genetic variation. Evolution 59:2312–2323

Puechmaille SJ (2016) The program structure does not reliably recover the correct population structure when sampling is uneven: Subsampling and new estimators alleviate the problem. Mol Ecol Resour 16:608–627

Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MAR, Bender D et al. (2007) PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet 81:559–575

Raj A, Stephens M, Pritchard JK (2014) FastSTRUCTURE: Variational inference of population structure in large SNP data sets. Genetics 197:573–589

Rangel TF, Diniz-Filho JAF, Bini LM (2010) SAM: a comprehensive application for spatial analysis in macroecology. Ecography 33:46–50

Ratter JA, Ribeiro JF, Bridgewater S (1997) The Brazilian cerrado vegetation and threats to its biodiversity. Ann Bot 80:223–230

Resende-Moreira LC, Vasconcelos PN, de, Souto AP, Menezes APA, Lemos-Filho JP, de, Lovato MB (2017) East-west divergence in central Brazilian Cerrado revealed by cpDNA sequences of a bird-dispersed tree species. Biochem Syst Ecol 70:247–253

Rey P, Tarrago L (2018) Physiological roles of plant methionine sulfoxide reductases in redox homeostasis and signaling. Antioxidants 7:1–26

Rowe W, Kershaw CJ, Castelli LM, Costello JL, Ashe MP, Grant CM et al. (2014) Puf3p induces translational repression of genes linked to oxidative stress. Nucleic Acids Res 42:1026–1041

Sakai A, Larcher W (2012) Frost survival of plants: responses and adaptation to freezing stress. Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

Savolainen O, Lascoux M, Merilä J (2013) Ecological genomics of local adaptation. Nat Rev Genet 14:807–820

Schulze M, Grogan J, Uhl C, Lentini M, Vidal E (2008) Evaluating ipê (Tabebuia, Bignoniaceae) logging in Amazonia: sustainable management or catalyst for forest degradation? Biol Conserv 141:2071–2085

Silva-Junior OB, Grattapaglia D, Novaes E, Collevatti RG (2018a) Design and evaluation of a sequence capture probe set for characterization and genotyping of SNPs in the genome of a Neotropical hardwood tree species. DNA Res 25:535–545

Silva-Junior OB, Grattapaglia D, Novaes E, Collevatti RG (2018b) Genome assembly of the Pink Ipê (Handroanthus impetiginosus, Bignoniaceae), a highly valued, ecologically keystone Neotropical timber forest tree. Gigascience 7:1–16

Silva de Miranda PL, Oliveira-Filho AT, Pennington RT, Neves DM, Baker TR, Dexter KG (2018) Using tree species inventories to map biomes and assess their climatic overlaps in lowland tropical South America. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 27:899–912

Siol M, Wright SI, Barrett SCH (2010) The population genomics of plant adaptation. N. Phytol 188:313–332

Sobral-Souza T, Lima-Ribeiro MS, Solferini VN (2015) Biogeography of Neotropical Rainforests: past connections between Amazon and Atlantic Forest detected by ecological niche modeling. Evol Ecol 29:643–655

Sobreiro MB, Collevatti RG, dos Santos YLA, Bandeira LF, Lopes FJF, Novaes E (2021) RNA-Seq reveals different responses to drought in Neotropical trees from savannas and seasonally dry forests. BMC Plant Biol 21:1–17

Sobreiro MB, Vieira LD, Nunes R, Novaes E, Coissac E, Silva-Junior OB et al. (2020) Chloroplast genome assembly of Handroanthus impetiginosus: comparative analysis and molecular evolution in Bignoniaceae. Planta 252:1–16

Souza-Neto AC, Cianciaruso MV, Collevatti RG (2016) Habitat shifts shaping the diversity of a biodiversity hotspot through time: Insights from the phylogenetic structure of Caesalpinioideae in the Brazilian Cerrado. J Biogeogr 43:340–350

Souza HAV, Collevatti RG, Lima-Ribeiro MS, De Lemos-Filho JP, Lovato MB (2017) A large historical refugium explains spatial patterns of genetic diversity in a Neotropical savanna tree species. Ann Bot 119:239–252

Syring JV, Tennessen JA, Jennings TN, Wegrzyn J, Scelfo-Dalbey C, Cronn R (2016) Targeted capture sequencing in whitebark pine reveals range-wide demographic and adaptive patterns despite challenges of a large, repetitive genome. Front Plant Sci 7:1–15

Teale WD, Paponov IA, Palme K (2006) Auxin in action: Signalling, transport and the control of plant growth and development. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7:847–859

Team RDC (2019) A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Found Stat Comput 2: https://www.R-project.org

Thomaz AT, Knowles LL (2020) Common barriers, but temporal dissonance: Genomic tests suggest ecological and paleo-landscape sieves structure a coastal riverine fish community. Mol Ecol 29:783–796

Vitorino LC, Lima-Ribeiro MS, Terribile LC, Collevatti RG (2016) Demographical history and palaeodistribution modelling show range shift towards Amazon Basin for a Neotropical tree species in the LGM. BMC Evol Biol 16:1–15

Vitorino LC, Lima-Ribeiro MS, Terribile LC, Collevatti RG (2018) Demographical expansion of Handroanthus ochraceus in the Cerrado during the Quaternary: implications for the genetic diversity of Neotropical trees. Biol J Linn Soc 123:561–577

Waters JM, Fraser CI, Hewitt GM (2013) Founder takes all: density-dependent processes structure biodiversity. Trends Ecol Evol 28:78–85

Whitlock MC, Lotterhos KE (2015) Reliable detection of loci responsible for local adaptation: inference of a null model through trimming the distribution of FST. Am Nat 186:24–36

Wright S (1935) Evolution in populations in approximate equilibrium. J Genet 30:257–266

Yamaoka S, Shimono Y, Shirakawa M, Fukao Y, Kawase T, Hatsugai N et al. (2013) Identification and dynamics of arabidopsis adaptor protein-2 complex and its involvement in floral organ development. Plant Cell 25:2958–2969

Yeaman S, Hodgins KA, Lotterhos KE, Suren H, Nadeau S, Degner JC et al. (2016) Convergent local adaptation to climate in distantly related conifers. Science 353:1431–1433

Yeaman S, Whitlock MC (2011) The genetic architecture of adaptation under migration-selection balance. Evolution 65:1897–1911

Zhou L, Holliday JA (2012) Targeted enrichment of the black cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa) gene space using sequence capture. BMC Genomics 13:1–12

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by competitive grants from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) to RGC (project no. 470306/2013-0 and Rede Cerrado CNPq/PPBio project no. 457406/2012-7), and Procad/CAPES project (# 88881.068425/2014-01). EN and RGC have been continuously supported by productivity grants from CNPq, which we acknowledge. LDV received a doctoral fellowship from Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES). We thank Professor Paradis for helping adapt PSMCR scripts for our data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RGC conceived and supervised the project, collected samples and extracted genomic DNA. OBS and LDV performed sequence data analysis and protein-coding gene annotation. EN and OBS performed transferability analysis. LDV and RGC performed population genomic analyses, wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Associate editor: Pår Ingvarsson.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vieira, L.D., Silva-Junior, O.B., Novaes, E. et al. Comparative population genomics in Tabebuia alliance shows evidence of adaptation in Neotropical tree species. Heredity 128, 141–153 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41437-021-00491-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41437-021-00491-0