Abstract

Orphan genes (OGs), which are genes unique to a specific taxon, play a vital role in primary metabolism. However, little is known about the functional significance of Brassica rapa OGs (BrOGs) that were identified in our previous study. To study their biological functions, we developed a BrOG overexpression (BrOGOE) mutant library of 43 genes in Arabidopsis thaliana and assessed the phenotypic variation of the plants. We found that 19 of the 43 BrOGOE mutants displayed a mutant phenotype and 42 showed a variable soluble sugar content. One mutant, BrOG1OE, with significantly elevated fructose, glucose, and total sugar contents but a reduced sucrose content, was selected for in-depth analysis. BrOG1OE showed reduced expression and activity of the Arabidopsis sucrose synthase gene (AtSUS); however, the activity of invertase was unchanged. In contrast, silencing of two copies of BrOG1 in B. rapa, BraA08002322 (BrOG1A) and BraSca000221 (BrOG1B), by the use of an efficient CRISPR/Cas9 system of Chinese cabbage (B. rapa ssp. campestris) resulted in decreased fructose, glucose, and total soluble sugar contents because of the upregulation of BrSUS1b, BrSUS3, and, specifically, the BrSUS5 gene in the edited BrOG1 transgenic line. In addition, we observed increased sucrose content and SUS activity in the BrOG1 mutants, with the activity of invertase remaining unchanged. Thus, BrOG1 probably affected soluble sugar metabolism in a SUS-dependent manner. This is the first report investigating the function of BrOGs with respect to soluble sugar metabolism and reinforced the idea that OGs are a valuable resource for nutrient metabolism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Orphan genes (OGs), genes that are restricted to a single lineage or species, show either nonsignificant or no sequence similarity with genes in other related species. OGs have been identified in many species or lineages, such as Arabidopsis thaliana1, Brassica rapa2, and Citrus sinensis3, with the continuing sequencing of several genomes. Although there is limited information on the functional significance of OGs in a particular species, they are known to play a role in primary metabolism, respond to biotic and abiotic stresses, and influence species-specific evolution and species-specific traits. A study reported that a drought-inducible Vigna unguiculata OG, UP12_8740, induced increased tolerance to osmotic stresses and soil drought, indicating the vital role played by OGs in specific environmental adaptation4. The A. thaliana OG Qua Quine Starch (QQS) is known to regulate the primary metabolic functions of carbon and nitrogen partitioning, and affected protein content when it was overexpressed in soybean, maize, and rice5. An in-depth analysis showed that QQS and its interactor NF-YC4 could reduce Arabidopsis and soybean susceptibility to viruses, bacteria, fungi, aphids, and soybean cyst nematodes6. The salamander-specific protein Prod1 can regulate limb regeneration by determining the direction of limb growth7. Currently, the prediction and characterization of the functions of most OGs are unclear, as they lack identifiable folds, recognizable domains, and functional motifs.

In plants, gene function can be investigated by employing a gain-of-function approach8. Target genes can be introduced into a plant genome under the control of a suitable constitutive promoter and terminator sequence to generate specific gain-of-function mutants and, subsequently, the overexpression of these genes can result in corresponding distinct phenotypes, which would help in deducing gene function9. A previous study showed that a full-length soybean cDNA overexpression mutant library in A. thaliana, which was constructed to study the function of soybean genes, provided an abundance of mutants for the genetic development of soybean10. Approximately 6000 A. thaliana transgenic lines were generated by overexpressing full-length Brassica napus cDNAs under the inducible FOX-Hunting system and several lines showed visible phenotypes post induction11. Therefore, the functional analysis of B. rapa OGs (BrOGs) could be performed rapidly based on the efficient transformation frequency and short generation time of A. thaliana. Until now, there have been no reports on the construction of a mutant library of OGs or on functional analysis of BrOGs.

Brassica vegetables are rich in nutrients and are planted and consumed worldwide12. These vegetables contain several types of soluble sugars, including sucrose (Suc) and its products glucose (Glc) and fructose (Fru), which provide energy and the basic carbon skeletons for various metabolic pathways13,14. There exist closes relationship between sugar signaling and developmental processes, and soluble sugars can act as signal transduction molecules to regulate development and adaptation to environmental challenges15,16. The hydrolysis products of Suc act as carbon and energy sources. Suc can be reversibly hydrolyzed by Suc synthase (SUS) to produce Fru and UDP-Glc, and irreversibly hydrolyzed by invertase (INV) to yield Fru and Glc14,17. There are six SUS isoforms in Arabidopsis that exhibit a high level of redundancy18. Arabidopsis SUS quadruple mutants (sus1/sus2/sus3/sus4) display normal growth and development, but the level of reduction in SUS activity varies among vegetative tissues18,19. There are several isoforms of acid INV, including acid INV isozymes in the cell wall (encoded by six genes, CWINVs) and vacuole (two genes, VINV), and neutral/alkaline INV isozymes (encoded by nine genes, CINVs) in the cytosol, plasma membrane, nucleus, mitochondrion, and chloroplast18,20. A study showed that mutations in A. thaliana cinv1/cinv2 resulted in severe growth inhibition and abnormal cell division18. SUS plays a central role in photosynthetic carbon assimilation and partitioning, and INV is involved in specific developmental stages18; however, it is challenging to differentiate their in planta role20. Until now, there have been no reports on the relationships between BrOGs and soluble sugar metabolism. Thus, the identification of BrOGs that could influence soluble sugar metabolism in B. rapa could be substantially beneficial for improving the nutritional quality of this species.

Previous studies have used mutagenesis and genetic transformation to create new cultivars, which are known to facilitate breeding processes21. However, instead of using laborious selection strategies to remove random mutations introduced by traditional mutagenesis methods, recent studies have employed CRISPR/Cas9 (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat/CRISPR-associated Cas9) technology for targeted gene modification and precise gene editing in several organisms22. Several studies have reported successful CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutations in many Cruciferae species, such as A. thaliana23, Camelina sativa24, B. napus25, and Brassica oleracea26, indicating its potential application in B. rapa, as well. Nonetheless, there are few reports on CRISPR/Cas9-induced mutations in transgenic B. rapa lines27. Therefore, an efficient gene-editing system is required to study the gene functions in B. rapa.

In a previous study, we identified OGs and revealed their possible roles in B. rapa2. However, their functional role remains unknown. Thus, we used A. thaliana as a host plant to perform a functional analysis of BrOGs. Here, we constructed a BrOG overexpression (BrOGOE) mutant library in A. thaliana, after which we characterized the phenotypic variations and the content of soluble sugars in the BrOGOE mutants. We performed an in-depth analysis of a specific OG (BrOG1) by establishing a gene-editing system, which revealed the potential role of BrOG1 in soluble sugar metabolism. This is the first report presenting a comprehensive evaluation of the function of BrOGs involved in soluble sugar metabolism.

Results

Generation of a BrOGOE mutant library and phenotypic investigation

To explore the functional significance of BrOGs, we generated a BrOGOE mutant library in A. thaliana. We successfully transformed 43 BrOGs (gene IDs listed in Supplementary Table S1) into A. thaliana (Col-0) through floral-dip transformation with random selection. The CaMV 35S promoter controlled the expression of BrOGs. Efficient screening of transgenic plants was performed using the DsRed marker gene under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter, which resulted in the selection of T2 homozygous seeds from different self-pollinated T1 transgenic seed lines. The overexpression of the transgenes was confirmed by quantitative reverse-transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR) for both the mutants and wild type (WT), and the results showed that the expression was detected only in the transgenic plants.

Next, we systematically investigated variations in the following phenotypic characteristics of the BrOGOE mutants using stable homozygous T2 transgenic plants during the vegetative and reproductive stages: stem height, rosette radius, leaf color, flowering time, leaf shape, seed number, and silique length. We found phenotypic variations in 19 BrOGOE mutants compared with the WT; 24 BrOGOE mutants showed no significant difference in phenotypes (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table S1). BrOG49OE, BrOG61OE, and BrOG91OE displayed decreased-stem height phenotypes, BrOG96OE displayed increased-stem height phenotypes, BrOG43OE and BrOG53OE displayed decreased-seed number phenotypes, BrOG111OE showed a decreased-silique length phenotype, and BrOG26OE showed an increased-rosette radius phenotype (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1, and Supplementary Fig. S1). Interestingly, the remaining 11 BrOGOE mutants, such as BrOG72OE, showed at least two different phenotypes compared with that of the WT. Five and two BrOGOE mutants showed delayed-flowering and early-flowering phenotypes, respectively, and the phenotypes of these two mutants were shared with others.

The blue bar and the solid circle represent mutants whose phenotype did not differ compared with that of the wild type (WT). The green bar and the solid circle represent mutants with whose phenotype significant differed from that of the WT. The solid gray circle indicates the absence of a corresponding phenotype for that mutant. The yellow column in the lower-left corner represents the total number of mutants corresponding to the phenotype. SHND: stem height with no difference compared with that of the WT; SHD: decreased stem height; SHI: increased stem height; RRND: rosette radius, with no difference; RRD: decreased rosette radius; RRI: increased rosette radius (the leaf color is green and yellow); FND: flowering time, with no difference; DF: delayed flowering; EF: early flowering; LSND: leaf shape, with no difference; LSC: leaf shape change; SNND: seed number, with no difference; SND: decreased seed number; SLND: silique length, with no difference; SLD: decreased silique length

Screening for mutants in which the soluble sugar content is affected

A previous study showed the significance of OGs in primary metabolism5. Soluble sugars are one of the main evaluation indicators of nutritional quality of Brassica vegetables13. Most of the mutants showed no distinct phenotype, indicating that these mutants were involved in primary metabolism. Thus, we screened the BrOGOE Arabidopsis lines to isolate mutants presenting variation in the contents of soluble sugars, such as Fru, Glc, and Suc. The soluble sugars were extracted from the shoots of representative 30-day-old T2 plants and measured through ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) (Fig. 2). After screening 43 mutant lines, we found that the Fru contents in 17 lines (such as BrOG1OE) was enhanced and those of 4 lines (such as BrOG10OE) decreased; 29 lines (such as BrOG1OE) showed a higher Glc content compared with that in the WT, whereas only one mutant (BrOG2OE) showed decreased Glc contents. Twenty lines (such as BrOG2OE) showed increased Suc contents and ten lines (such as BrOG1OE) showed decreased contents. In addition, 81.40% of the lines showed variations in total soluble sugar contents: 34 lines (such as BrOG1OE) showed increased contents, 1 (BrOG52OE) showed decreased contents, and only 8 lines (such as BrOG19OE) displayed no significant difference compared those in with WT. We observed a change in soluble sugar content in 42 Arabidopsis lines (BrOG19OE was excluded), which suggested that BrOGs could extensively impact soluble sugar metabolism.

Wild-type Col-0 (WT) and BrOGOE plants were grown under LD conditions. Thirty-day-old plants were used to analyze the soluble sugars, including fructose (Fru, light blue bar), glucose (Glc, light green bar), and sucrose (Suc, light pink bar), simultaneously. The data in bar graphs are expressed as the means ± SEs, calculated from three replications. Each replicate consisted of an independent pool of 15 plants. The black asterisks inside the bars indicate significant differences between the mutants and WT for Fru, Glc, and Suc (p < 0.05) based on Student’s t-tests. The red asterisks at the top of the bars indicate significant differences in total soluble sugars between the mutants and WT (p < 0.05) based on Student’s t-tests

Sequence analysis of BrOG1

BrOG1 (BraA08002322) was randomly chosen for preliminary analysis of its role in soluble sugar metabolism due to the high abundance of variation in soluble sugar contents in the BrOGOE library. BrOG1 has a highly homologous gene located on the scaffold in the B. rapa reference genome (v2.5); in addition, BrOG1 has a nucleotide sequence similarity of 99.23% and a protein sequence similarity of 98.84%. In this study, these two intronless genes were labeled BrOG1A (BrOG1) and BrOG1B (BraSca000221). We found sequence differences between BrOG1A and BrOG1B consisting of synonymous mutations (132 bp, C to T) and nonsynonymous mutations (258 bp, G to T, causing E to D) (Fig. 3a). Therefore, BrOG1A could represent the function of BrOG1B and was thus used to characterize the potential role of BrOG1 in Arabidopsis. Protein sequence analysis of BrOG1A and BrOG1B showed that they had no conserved domains, signal peptides, or cleavage sites and were not identified as transcription factors.

a Sequence alignment of BrOG1A and BrOG1B. The coding sequences and protein sequences were obtained from the Brassica database (BRAD). The two solid black boxes represent synonymous mutations (132 bp, C to T) and nonsynonymous mutations (258 bp, G to T, causing E to D), respectively. b Phenotypes of BrOG1AOE T3 lines in A. thaliana. Representative images of 37-day-old mutants resulting from three independent genetic transformation events (T3-1, T3-2, and T3-3) and wild-type Col-0 (WT). The scale bars are 2 cm. c Soluble sugar content in 30-day-old wild-type (WT) and BrOG1AOE transgenic Arabidopsis plants. The analysis was performed in triplicate, with 15 plants per replicate. d Detection of enzyme activity of sucrose synthase (SUS) and invertase (INV). e Levels of AtSUS transcripts in WT and BrOG1AOE plants. d, e The analysis was performed in triplicate, with three plants per replicate. c–e All the values are expressed as the means ± SEs. The black letters indicate statistically different groups (one-way ANOVA, p < 0.05). c The red letters at the top of the bars indicate significant differences in total soluble sugars between the mutants and WT (one-way ANOVA, p < 0.05)

BrOG1 probably influenced the content of soluble sugar in a SUS-dependent manner

We compared the phenotypic features between the BrOG1AOE mutant and WT during the vegetative and reproductive growth stages under LD conditions. The results showed a similarity between the phenotypes of the BrOG1AOE mutant and the WT (Supplementary Table S2 and Fig. 3b). Three T3 lines from independent genetic transformation events were further characterized for their soluble sugar content. Consistent with the results of T2 representative lines, overexpression of BrOG1A increased the contents of Fru, Glc, and total sugars, and decreased the contents of Suc compared with those in the WT (Fig. 3c). The activity of Suc-degrading enzymes, SUS and INV, were then analyzed in the BrOG1AOE mutant. There was no significant difference in AtINV activity of the BrOG1AOE mutant or the WT, whereas the AtSUS activity in the BrOG1AOE mutant significantly decreased compared with that in the WT (Fig. 3d). The decrease in AtSUS enzyme activity was further confirmed by expression analysis of all AtSUSs, which were found to be downregulated in the BrOG1AOE lines (Fig. 3e).

Sequence validation of BrOG1A and BrOG1B in Chinese cabbage for genetic transformation

To confirm the potential role of BrOG1 in Chinese cabbage, we knocked out the OG BrOG1 in Chinese cabbage using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutation. Sequence identification of these two genes was performed in the self-propagating Chinese cabbage GT-24, which was also used for genetic transformation. A common specific primer pair (BrOG1-com F/R) was designed via upstream and downstream extension of these two genes. Sequence analysis of BrOG1A and BrOG1B in GT-24 and Chiifu revealed high similarity. These results suggested the occurrence of BrOG1 gene-specific mutagenesis.

Detection of sgRNA target activity and vector construction

Five common single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) neighboring a 5′-NNGRRT-3′ PAM (Supplementary Table S3) were designed, after which the activity of the sgRNA target was measured. The results of electrophoresis postenzyme digestion showed that only sgRNA3 exhibited a high in vitro digestion efficiency, whereas the other sgRNAs showed no digestion activity, which laid the foundation for subsequent gene-knockout experiments (Fig. 4a). sgRNA3 was then constructed into the sgRNA expression vector VK005-101, which was confirmed by sequencing using primer vector-seq-R, and was used for further genetic transformation experiments (Fig. 4b).

a Detection of the target efficiency of sgRNAs in vitro. The DNA fragment indicates the in vitro transcription template of sgRNA (T7 promoter, target, and the sgRNA scaffold sequence). The red and green arrows indicate cut bands and uncut bands, respectively. The “+” and “−” symbols indicate that the corresponding substances were included and omitted, respectively. The negative controls NC-1 and NC-2 indicate the exclusive addition of the DNA fragments of sgRNA5 and g2, respectively. The g1 and g2 positive controls indicate standard gRNA1 and gRNA2, respectively. b Schematic diagram of the T-DNA region of the assembled SaCas9/sgRNA expression vector (VK005-101) for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. RNA-guided Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 nuclease system (SaCas9) using both the A. thaliana ubiquitin 6-26 (atU6) promoter and a 2× 35S promoter was used to express a single guide RNA (sgRNA) scaffold. For plant selection, the constructs harbored a hygromycin (Hyg) resistance cassette. LB: left border, RB: right border. c Results of agarose gel electrophoresis for the detection of exogenous T-DNA insertion in six T0 plants. GT-24 indicates the nontransgenic control and P1–P6 indicate different lines in the T0 generation. Amplified bands of mutants carrying the transgene insertion occurred at 693 bp. d Four mutant alleles that were from one double heterozygous T0 plant (P2) generated by CRISPR/Cas9 were tested through Sanger sequencing. The name of the allele and the size of each insertion are shown on the right. The inserted base of the alleles is highlighted using the red color. WT indicates a GT-24 nontransgenic plant. The PAMs are underlined. e Sequencing of targeted mutations in transgenic T0 plants (P1, P4, P5, and P6). The size of each insertion and deletion of the alleles are indicated on the right; WT represents the absence of a mutation. f Detection of exogenous T-DNA insertions in T1 plants by PCR. Nos. 1–30 represent individual T1 plants from the inbreeding generations of line P2. g Alignment of the CRISPR/Cas9 target sequences from BrOG1A and BrOG1B compared to the sequence of a potential off-target site. The PAMs are underlined and SNPs are highlighted in red

Generation of CRISPR/Cas9-induced BrOG1 mutations in Chinese cabbage

We cocultivated 200 cotyledon-petiole explants of Chinese cabbage GT-24 via Agrobacterium tumefaciens containing a recombinant plasmid. Sixteen resistant buds were obtained after selection, with a differentiation rate of 8%. A total of 16 shoots were then regenerated as rooted plantlets in tissue culture and 9 rooted plantlets were transferred to the greenhouse, of which 6 plantlets survived (named P1 to P6). The T0 plants that contained the transgene were selected using Cas_detect_F and CaMVtR primers, which amplified a T-DNA region that contained the CRISPR/Cas9 target sequence and sgRNA (Supplementary Table S4). Five plants (except P3) were identified as transgenic, with a transformation rate of 31.25% based on the number of resistant buds (Fig. 4c). BrOG1-com F/R primers flanking the target region were then used to sequence both BrOG1A and BrOG1B of the transgenic plants (Supplementary Table S4). The sequencing results showed that one plant (P2) had mutations in all the target sequences: two in BrOG1A and two in BrOG1B. The final transformation rate was 6.25%, based on the number of resistant buds (Fig. 4d). The respective alleles were labeled A2 and B2 for a single base A insertion and A3 and B3 for a single base T insertion. The P2 plant did not carry the WT (nonmutated) alleles (A1/B1) and could be a double heterozygote plant. The CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutations occurring near the PAM sequence and a single base insertion (A or T) were identified. These frameshift mutations most likely form nonfunctional proteins. Mutations induced by CRISPR/Cas9 causing a single base insertion (A, T, and C) or a two-base deletion (CA) were also found in other knockout lines; however, the nonmutated types (A1/B1) were also found (Fig. 4e). Thus, the results indicated the absence of a functional BrOG1 gene in P2.

Inheritance of CRISPR/Cas9-induced BrOG1 mutations

We screened 30 T1 plants by PCR using the Cas_detect_F and CaMVtR primers, which revealed 21 transgenic and 9 nontransgenic plants (Fig. 4f), and matched the expected mendelian segregation ratio for a single gene (Supplementary Table S5). This indicated that P2 contained a single Cas9 insertion. Both BrOG1A and BrOG1B from the 30 T1 plants were sequenced. All the plants contained the mutated alleles, suggesting that P2 was a double heterozygote (A2A3/B2B3). In addition, the segregation pattern was consistent with double gene inheritance and random segregation between genes. The mutations were not associated with the transgene insertion, because we found nontransgenic plants that had all four mutant alleles (such as T2-6 and T2-19). Nine genotypes were obtained, which were expected to have undergone random segregation.

Off-target analysis

Next, we searched for a possible off-target site of Cas9 endonuclease activities in the P2 mutant plant. We hypothesized that if these activities had occurred, these two mutated sequences would be highly similar to sequences of the BrOG1 genes (noncoding region on chromosome A02) (Fig. 4g). PCR primer pairs (OffA02F/R) that would bind to the flanking sequences from the potential off-target sites were designed (Supplementary Table S4). We sequenced the PCR products from ten T1 offspring and P2 plants. The absence of any sequence variation compared with the Chiifu reference genome indicated that these plants did not contain any off-target mutations in this region. Thus, in one step, we produced a double mutant that did not contain any WT allele but carried mutated BrOG1A and BrOG1B genes.

The phenotype of the BrOG1-knockout mutants complements that of BrOG1AOE mutants

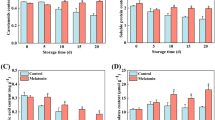

During the seedling stage, we observed no significant phenotypic variations between the BrOG1-knockout lines and GT-24 (Fig. 5a). As the overexpression of BrOG1A resulted in increased contents of Fru, Glc, and total soluble sugars in Arabidopsis, we expected them to decrease in the BrOG1 knockdown mutants. Similarly, the decrease in Suc content in the BrOG1AOE lines should be opposite in the BrOG1 mutants. We assessed the contents of Fru, Glc, Suc, and total sugars in the T2 BrOG1 mutants and compared them to the contents in GT-24 control plants. We found decreased Fru, Glc, and total sugar contents and increased Suc contents (Fig. 5b). We then compared the activity of BrSUS and BrINV in the mutants with that in the WT to understand the cause behind the variation in soluble sugars. The results showed a higher activity of BrSUS enzymes in BrOG1 T2 lines compared with that in GT-24; however, there was no significant difference in the activity of BrINV (Fig. 5c). We then searched for BrSUSs through protein sequence alignment with six AtSUS genes (AtSUS1–6) against the B. rapa genome through the BLASTP program. A total of seven BrSUSs were identified in the B. rapa genome with significant similarity to AtSUSs (query cover and identification ≥ 70%) and were labeled BrSUS1a, 1b, 2, 3, 5, 6a, and 6b based on their evolutionary relationship to AtSUSs (Fig. 5d). The expression of seven BrSUSs was then analyzed via qRT-PCR. Consistent with the increased BrSUS activity in the BrOG1 mutants, we found elevated expression of BrSUS1b, BrSUS3, and BrSUS5 (Fig. 5e). However, there was no significant difference in the expression of BrSUS6a and BrSUS6b compared with that in the control, and transcripts of BrSUS2 were not detected. Thus, complementary tests, along with studies on the contents of soluble sugars, enzyme activity, and gene expression in the overexpression and knockout transgenic lines, further substantiated the potential role of BrOG1 in soluble sugar metabolism.

a Phenotypes of BrOG1-knockout lines. The images were taken upon the appearance of four true leaves (30-day-old plants). Representative T2 plants (T2-6 and T2-19) from a T0 plant were self-pollinated (P2). GT-24 indicates wild-type plants. The scale bars are 3 cm. b Soluble sugar content in 30-day-old wild-type (GT-24) and BrOG1 mutants. The analysis was performed in triplicate, with fifteen plants per replicate. Fru (fructose, light blue bar), Glc (glucose, light green bar), and Suc (sucrose, light pink bar) were analyzed simultaneously. c Detection of the activity of sucrose synthase (SUS) and invertase (INV) using an ELISA. d Phylogenetic relationships of SUSs between A. thaliana and B. rapa. Thirteen amino acid sequences were analyzed. A neighbor-joining tree was constructed by aligning the amino acid sequences. The red solid triangle and green solid box indicate BrSUSs and AtSUSs, respectively. e Expression levels of BrSUSs in GT-24 and BrOG1 plants. c, e The analysis was performed in triplicate, with three plants per replicate. GT-24, control plants (light brown bar); T2-6 (light red bar); T2-19 (light orange bar). b, c, e All the values are expressed as the means ± SEs. The black letters indicate significant differences between the mutants and the control (one-way ANOVA, p < 0.05). b The red letters at the top of the bars indicate significant differences in total soluble sugars between the mutants and the control (one-way ANOVA, p < 0.05)

Discussion

In this study, we first generated a BrOGOE mutant library in A. thaliana and comprehensively investigated the phenotypic variations in the BrOGOE mutants. Based on the importance of primary metabolism in Brassica vegetables12, we explored the role of the respective mutations in soluble sugar metabolism. Due to the abundance of variation in soluble sugar content in this BrOGOE library, BrOG1 was randomly chosen for preliminary evaluation of its role in soluble sugar metabolism and CRISPR/Cas9 was used to mediate mutations in BrOG1 in Chinese cabbage to verify its function.

Generation of BrOGOE Arabidopsis lines

A previous study first investigated the numbers, features, and expression patterns of OGs in B. rapa (BrOGs), providing valuable biological information for exploring the function of BrOGs2. To explore the functions of these OGs, we developed an A. thaliana overexpression library using 43 BrOGs from B. rapa under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter. Functional analysis of BrOGs using A. thaliana is an efficient method, because it requires relatively little time to analyze gene function. In addition, the floral-dip method is the easiest way to perform highly efficient gene transformation8,10,28. These BrOGs do not contain any homologous sequences in A. thaliana and their ectopic expression would result in phenotypic variations, making it easier to understand the function of OGs2. Furthermore, BrOG function could also be analyzed using A. thaliana as a heterologous host, as OGs could play similar roles across species5. Thus, we speculated that the functions of BrOGs in A. thaliana might be identical to their roles in B. rapa.

The use of the DsRed marker gene under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter increases the convenience of the selection of transgenic seeds through fluorescence29. In A. thaliana, one or more transgenes are likely to be present in the selected lines, which is typical for the Agrobacterium-mediated floral-dip method11; thus, we did not investigate the copy number of the T2 homozygous mutants. Phenotypic observations of the BrOGOE mutants revealed that only 44% of the mutants displayed visible variations. These results were similar to those of the visual phenotype of the overexpression and RNA interference mutant lines of Arabidopsis OG QQS, which are known to be indistinguishable from the WT at all stages—from seedling to senescence30,31. In a soybean full-length cDNA overexpression library, a low percentage of mutants exhibited abnormal or favorable phenotypes10. Moreover, the overexpression of the V. unguiculata OG UP12_8740 showed no visible phenotype under normal conditions compared with that of the control4. Thus, the construction of the BrOG mutant library will contribute to revealing the function of OGs.

BrOGOE in Arabidopsis largely influenced soluble sugar metabolism

Chinese cabbage is a popular vegetable, with a long history of cultivation in China. Soluble sugars are essential nutrients and important parameters of vegetable quality32,33. The taste characteristics of vegetables can be evaluated based on soluble sugar contents34. Therefore, we screened mutants with altered contents of soluble sugars within the BrOGOE mutant library. A high rate of variation in soluble sugar content was observed, which could be due to the unique function of these BrOGs. Functional analysis of the A. thaliana OG QQS indicated that it could serve as a component of the starch metabolic network in A. thaliana leaves, and the increased transcript level of the QQS in the sugar-insensitive sis8 mutant suggests its possible role in maintaining the balance of carbon flow to Suc31. Another study showed that QQS might integrate primary metabolism and changes in the environment to optimize tolerance to various stresses35. Prediction of the cellular roles of OGs within the Poaceae indicated that more than 26% of genes were involved in central intermediary and energy metabolism36. Many BrOGs altered the contents of soluble sugars, suggesting that they play vital roles in the metabolism of soluble sugars; however, the underlying mechanism is unclear and needs further exploration.

CRISPR/Cas9 caused highly efficient target-gene mutations in Chinese cabbage

Tissue culture in B. rapa is challenging; thus, studies on B. rapa vegetable transformation are limited, especially with respect to Chinese cabbage27. Our laboratory has successfully developed a simple, efficient method for A. tumefaciens-induced transformation of Chinese cabbage, in which the ratio of the regenerated plantlets to the total number of cocultivated explants can reach approximately 3%37. This efficient transgenic approach promotes breeding and gene functional studies in Chinese cabbage. Recently, compared with traditional mutagenesis strategies, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutation has gained popularity as a precise and efficient method for gene functional characterization and crop improvement21. Thus, in this study, we used CRISPR/Cas9 to knock out BrOG1A and BrOG1B in Chinese cabbage. The observed mutation frequency (83.33%) in the T0 plants was consistent with that in other plant species, such as B. napus and Oryza sativa, which suggested that the variations in genome size did not influence the efficiency of the targeted genome editing mediated by CRISPR/Cas921,38.

A recent study reported a high mutation efficiency in genome editing of Chinese cabbage39 and the ratio of the regenerated plantlets to the total number of cocultivated explants was relatively low (0.12–1.07%) compared with that in the present study (3%). Based on the T1 generation plants, we knew that the mutations were stably inherited regardless of the presence of T-DNA. Similar results were observed for the CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutations in B. napus21,25. Frameshift mutations within the common target sequences of BrOG1A and BrOG1B were induced. The lack of mutations within a potential off-target site with high homology to the sgRNA target sequence suggested that CRISPR/Cas9-induced mutations in Chinese cabbage were highly accurate. Thus, this is the first report on CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutations of OGs in the Chinese cabbage genome.

BrOG1 altered the contents of soluble sugars probably in a SUS-dependent manner

In this study, BrOG1AOE was chosen for gene characterization as a representative BrOGOE mutant for functional research. As BrOG1A and BrOG1B are highly homologous genes (Fig. 3a), BrOG1A served as the representative for BrOG1B and was overexpressed in A. thaliana. We found an insignificant difference between the BrOG1AOE mutants and the WT (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table S2) and a decrease in AtSUS activity and AtSUS expression (Fig. 3d, e). Consistent with our findings, A. thaliana sus1/sus2/sus3/sus4 and sus5/sus6 mutant plants and control plants showed no visible differences, and the levels of AtSUS activity in the leaves and stems were lower in the mutants than in the controls18,19. Another study indicated that the loss of SUS activity had minimal influence on root growth under well-aerated conditions18. Compared with the control plants, the BrOG1AOE plants had high contents of total soluble sugars caused by an increase in the contents of Fru and Glc and lower contents of Suc (Fig. 3c). Multiple AtSUS T-DNA insertion lines displayed changes in sugar composition, whereas one mutant did not20. Overexpression of DsSWEET12 (Dianthus spiculifolius sugars will eventually be exported transporters 12s) in A. thaliana resulted in decreased Suc content; however, the contents of Fru and Glc were higher in the overexpression line than in the WT40.

In contrast to these findings in the BrOG1AOE mutants, compared with the control plants, the BrOG1 mutants showed higher levels of BrSUS activity, BrSUS expression, and Suc content but lower contents of Fru, Glc, and total soluble sugars. The phenotypes of the BrOG1AOE and BrOG1 mutants and the control plants did not differ, and there was no significant difference in INV activity in the mutants compared with that in the control plants. A previous study showed that most of the functions proposed for INV were unique to specific developmental periods, and that cytosolic INV is indispensable for the normal growth of A. thaliana under experimental conditions18. Therefore, the phenotypes caused by the knockout of BrOG1 in Chinese cabbage and the overexpression of BrOG1A in Arabidopsis were found to be complementary. Moreover, the expression of AtINVs or BrINVs was not detected, as INVs are regulated at the posttranscriptional level by proteinase inhibitors, kinases, or compartmentalization41. The development of large sinks is highly dependent on SUS activity in crop plants, which might be the result of domestication and selection from their wild counterparts20, suggesting that BrOG1 caused variations in the soluble sugar content probably in a SUS-dependent manner in sink cells. These findings indicated that BrOGs play vital roles in soluble sugar metabolism and act as important genetic resources for improving the nutritional quality of B. rapa.

Materials and methods

Plant materials, growth conditions, and characterization of the mutants

A. thaliana ecotype Col-0 and the transformed lines were grown under LD conditions (16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod) in the presence of cool-white fluorescence light at 22 ± 1 °C at a relative humidity of 65–70%. For the characterization of BrOGOE mutants, flowering time was measured by counting the number of rosette leaves until flowering or the number of days until the first flower opens, following the methods of a previous study42, and rosette radius was determined at the same time by taking the mean of the length of the two largest leaves. The silique length and seed number were measured following a previously described method43. Stem height was measured from the central base of the rosette leaves to the main stem top after most siliques turned ripe. Fifteen plants of the BrOGOE lines or Col-0 were randomly investigated.

Overexpression of the vector constructs, Arabidopsis transformation, and selection

Full-length genome sequences of BrOGs with 15 bp extensions (BrOGOEc-F/R primers; Supplementary Table S4) were seamlessly inserted into the EcoRI/XhoI linearized plant binary expression vector pBinGlyRed3-35S using a TaKaRa In-Fusion® HD Cloning Kit (Dalian, China, catalog number 639650), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The constructed plasmids were sequenced by Sanger sequencing. The pBinGlyRed3-35S vector was modified from the pBinGlyRed3 vector29. The CaMV35Sp-MCS-NOS fragments from the intermediate vector 35S-INT were cloned using a RED3c-F/R primer (Supplementary Table S4) and connected to a BamHI/HindIII linearized pBinGlyRed3 vector using an In-Fusion® HD Cloning Kit, after which the constructed plasmid pBinGlyRed3-35S was sequenced through Sanger sequencing. The DsRed (Discosoma red fluorescent protein) marker gene in this vector under the control of the constitutively expressed cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter was used to select fluorescent transgenic seeds. The binary vector containing CaMV35Sp-BrOGs-NOS was introduced into A. tumefaciens GV3101 by the freeze-thaw method. Transgenic Arabidopsis Col-0 plants were generated via the floral-dip method28.

Sequence analysis

The Conserved Domain Database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) and the Pfam database (https://pfam.xfam.org/) were used for searching conserved domains. The SignalP Server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/) was used to search signal peptides and protein cleavage sites, and the Plant Transcription Factor Database (PlantTFDB) (http://planttfdb.cbi.pku.edu.cn/) was used to identify transcription factors.

Construction of the CRISPR/Cas9 vector

Five sgRNAs (Supplementary Table S3) were designed using CRISPR-GE (http://skl.scau.edu.cn/). A SaCas9-gRNA Target Efficiency Detection Kit (ViewSolid Biotech, China, catalog number VK012) was used to determine the sgRNA target efficiency, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The in vitro transcription template of sgRNA included the T7 promoter, target, and sgRNA scaffold sequence. The target efficiency of sgRNA was determined based on the in vitro digestion of the double-stranded DNA of the target gene by sgRNA. The guide sequence was inserted into the gRNA expression vector backbone (VK005-101; Fig. 4b) using annealed oligonucleotides, following the instructions of a SaCas9/gRNA Construction Kit (ViewSolid Biotech, China, catalog number VK005-101). Supplementary Table S4 lists the primers used in this study.

Chinese cabbage transformation

Chinese cabbage (GT-24, self-propagating material provided by the laboratory) was used for genetic transformation. Seeds of GT-24 were surface sterilized by immersion in 75% ethanol for 30 s and 10% sodium hypochlorite for 1 min, followed by soaking in 2% sodium hypochlorite. The seeds were stirred for 15 min and washed with sterile water (four to five times). Afterward, 10–20 seeds were placed in a glass culture bottle containing 30–40 mL of germination media that consisted of 1/2-strength MS basal media supplemented with 6-BA (5 mg/L), NAA (0.5 mg/L), AgNO3 (4 mg/L), Suc (30 g/L), and agar (7 g/L; pH 5.8), and maintained under LD conditions (16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod) in the presence of cool-white fluorescence light at 25 °C. Cotyledons, including petioles (1–2 mm), which were carefully excised from 4-day-old seedlings were used as explants in the transformation experiments. A. tumefaciens strain GV3101 containing the working vector was cultured to an OD600 of 0.5 in LB liquid media consisting of kanamycin (50 mg/L) and gentamicin (50 mg/L) at 28 °C at 220 r.p.m. The cells were collected and resuspended in DM liquid media (MS basal media with 100 μM acetosyringone) twice. The explants were then suspended in a tenfold diluted infection solution in the DM liquid media for 15 min, with stirring every 5 min. After being blot-dried on sterilized paper towels, the explants were transferred to cocultivation media (MS media supplemented with 6-BA (5 mg/L), NAA (0.5 mg/L), AgNO3 (4 mg/L), Suc (30 g/L), agar (7 g/L), and acetosyringone (100 μM) pH 5.8) for 2 days at 25 °C in the dark. The explants were then transferred to shoot induction media (MS media supplemented with 6-BA (5 mg/L), NAA (0.5 mg/L), AgNO3 (4 mg/L), Suc (30 g/L), agar (7 g/L), hygromycin (25 mg/L), and timentin (200 mg/L); pH 5.8) until shoot buds developed (~14 days later). Resistant buds excised from the explants were transferred to new shoot induction media. When the hygromycin-resistant shoots were more than 2 cm tall and had more than four leaves, they were transferred to root induction media (MS media supplemented with NAA (0.5 mg/L), IBA (1.5 mg/L), Suc (30 g/L), agar (7 g/L), and timentin (200 mg/L); pH 5.8). The rooted shoots were transplanted into a sterile peat substrate (Pindstrup Horticulture Co., Ltd) and acclimatized in a growth chamber at 25 °C and with 60–70% humidity.

Detection of mutations induced by CRISPR/Cas9 and off-target analysis

The standard CTAB method was employed to extract DNA from the leaf samples. PCR-based analysis was performed following a previously described method2. The target genes were amplified using specific primers (BrOG1-com F/R) flanking the designed target sequences. The PCR products were purified using a TaKaRa MiniBEST DNA Fragment Purification Kit (Dalian, China, catalog number 9761) following the manufacturer’s instructions and were cloned into a vector using a TaKaRa pMD™ 18-T Vector Cloning Kit (Dalian, China, catalog number 6011) for further sequencing. A minimum of ten clones from each sample were sequenced through Sanger sequencing. The prediction of the potential off-target sites was performed using CRISPR-GE (http://skl.scau.edu.cn/). Similarly, purified PCR products amplified with OffA02 F/R primers from the samples were cloned into a TaKaRa pMD™ 18-T vector for Sanger sequencing. A minimum of six clones from each sample were sequenced.

Soluble sugar content and enzyme activity analysis

Preparation of samples for analyzing the soluble sugar content (including Fru, Glc, and Suc) was performed following a previously described method44. Lyophilized powder of the aerial tissues collected from 30-day-old BrOGOE, Col-0 plants, BrOG1 and GT-24 plants (3 biological replicates each, with 15 plants per replicate) was used for extraction. The extraction of soluble sugars was performed using a previously described method45 and the sugar contents were analyzed using an UPLC system (Agilent 1290 Infinity II, USA) on an amine column (DiKMA Platisil™ 5 µm NH2, 250 × 4.6 mm, China) equipped with a refractive index detector (1290 RID, G7162B). The mobile phase consisted of 75% acetonitrile : 25% water and the flow rate was maintained at 1 mL/min. The temperature of the amine column was maintained at 35 °C. Sample preparation for enzyme activity analysis was identical to the sample preparation for soluble sugar content analysis (three biological replicates with three plants per replicate). The detection of SUS and INV activity was performed using an MLBIO Plant Sucrose Synthase ELISA Kit (catalog number ml077397) and an MLBIO Plant Invertase ELISA Kit (catalog number ml036302), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Expression analysis of the SUS genes

The sample preparation for the detection of SUS gene expression was consistent with the sample preparation for the enzyme activity analysis (three biological replicates with three plants per replicate). Total RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and qRT-PCR were performed following previously described methods2. The 2−∆∆Ct method46 was used to determine gene expression. Supplementary Table S4 lists the primer pairs used.

Statistical analysis

The χ2-test was used to determine the confidence level for the segregation ratios of the BrOG1 T1 lines. Other statistical evaluations were performed via Student’s t-tests or one-way analysis of variance, followed by individual comparisons with Duncan’s multiple range tests using SPSS software v19.0. Sequence alignment was performed using BioEdit software v7.2.547. Evolutionary relationships of the SUSs in A. thaliana and B. rapa were inferred using MEGA v6 software48. The data were graphically analyzed using GraphPad Prism software v8 (San Diego, CA, USA) and TBtools software v0.66549.

References

Donoghue, M. T., Keshavaiah, C., Swamidatta, S. H. & Spillane, C. Evolutionary origins of Brassicaceae specific genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Evol. Biol. 11, 47 (2011).

Jiang, M. et al. Mining of Brassica-specific genes (BSGs) and their induction in different developmental stages and under Plasmodiophora brassicae stress in Brassica rapa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 2064 (2018).

Xu, Y. et al. Identification, characterization and expression analysis of lineage-specific genes within sweet orange (Citrus sinensis). BMC Genomics 16, 995 (2015).

Li, G. et al. Orphan genes are involved in drought adaptations and ecoclimatic-oriented selections in domesticated cowpea. J. Exp. Bot. 28, 3101–3110 (2019).

O’Conner, S. et al. in Engineering Nitrogen Utilization in Crop Plants (eds Shrawat, A., Adel Zayed, A. & Lightfoot, D.) 95–117 (Springer, 2018).

Qi, M. et al. QQS orphan gene and its interactor NF-YC4 reduce susceptibility to pathogens and pests. Plant Biotechnol. J. 17, 252–263 (2019).

Kumar, A., Gates, P. B., Czarkwiani, A. & Brockes, J. P. An orphan gene is necessary for preaxial digit formation during salamander limb development. Nat. Commun. 6, 8684 (2015).

Kondou, Y. et al. Systematic approaches to using the FOX hunting system to identify useful rice genes. Plant J. 57, 883–894 (2009).

Dubouzet, J. G. et al. Screening for resistance against Pseudomonas syringae in rice-FOX Arabidopsis lines identified a putative receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase gene that confers resistance to major bacterial and fungal pathogens in Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 9, 466–485 (2011).

Li, X. et al. Large-scale investigation of soybean gene functions by overexpressing a full-length soybean cDNA library in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 631 (2018).

Ling, J. et al. Development of iFOX-hunting as a functional genomic tool and demonstration of its use to identify early senescence-related genes in the polyploid Brassica napus. Plant Biotechnol. J. 16, 591–602 (2018).

Song, X. et al. Genes associated with agronomic traits in non-heading Chinese cabbage identified by expression profiling. BMC Plant Biol. 14, 71 (2014).

Rosa, E., David, M. & Gomes, M. H. Glucose, fructose and sucrose content in broccoli, white cabbage and Portuguese cabbage grown in early and late seasons. J. Sci. Food Agric. 81, 1145–1149 (2001).

Xiang, L. et al. Exploring the neutral invertase-oxidative stress defence connection in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 3849–3862 (2011).

Li, Y. et al. Arabidopsis sucrose transporter SUT4 interacts with cytochrome b5-2 to regulate seed germination in response to sucrose and glucose. Mol. Plant 5, 1029–1041 (2012).

Smeekens, S. Sugar regulation of gene expression in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 1, 230–234 (1998).

Fallahi, H. et al. Localization of sucrose synthase in developing seed and siliques of Arabidopsis thaliana reveals diverse roles for SUS during development. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 3283–3295 (2008).

Barratt, D. H. et al. Normal growth of Arabidopsis requires cytosolic invertase but not sucrose synthase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 13124–13129 (2009).

Baroja-Fernandez, E. et al. Sucrose synthase activity in the sus1/sus2/sus3/sus4 Arabidopsis mutant is sufficient to support normal cellulose and starch production. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 321–326 (2012).

Ruan, Y. L. Sucrose metabolism: gateway to diverse carbon use and sugar signaling. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 65, 33–67 (2014).

Yang, H., Wu, J. J., Tang, T., Liu, K. D. & Dai, C. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing efficiently creates specific mutations at multiple loci using one sgRNA in Brassica napus. Sci. Rep. 7, 7489 (2017).

Sander, J. D. & Joung, J. K. CRISPR-Cas systems for editing, regulating and targeting genomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 347–355 (2014).

Feng, Z. et al. Efficient genome editing in plants using a CRISPR/Cas system. Cell Res. 23, 1229–1232 (2013).

Jiang, W. Z. et al. Significant enhancement of fatty acid composition in seeds of the allohexaploid, Camelina sativa, using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. Plant Biotechnol. J. 15, 648–657 (2017).

Braatz, J. et al. CRISPR-Cas9 targeted mutagenesis leads to simultaneous modification of different homoeologous gene copies in polyploid oilseed rape (Brassica napus). Plant Physiol. 174, 935–942 (2017).

Lawrenson, T. et al. Induction of targeted, heritable mutations in barley and Brassica oleracea using RNA-guided Cas9 nuclease. Genome Biol. 16, 258 (2015).

Li, G. et al. Research progress on Agrobacterium tumefaciens-based transgenic technology in Brassica rapa. Hortic. Plant J. 4, 126–132 (2018).

Zhang, X., Henriques, R., Lin, S. S., Niu, Q. W. & Chua, N. H. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana using the floral dip method. Nat. Protoc. 1, 641–646 (2006).

Zhang, C. et al. A thraustochytrid diacylglycerol acyltransferase 2 with broad substrate specificity strongly increases oleic acid content in engineered Arabidopsis thaliana seeds. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 3189–3200 (2013).

Li, L. & Wurtele, E. S. The QQS orphan gene of Arabidopsis modulates carbon and nitrogen allocation in soybean. Plant Biotechnol. J. 13, 177–187 (2015).

Li, L. et al. Identification of the novel protein QQS as a component of the starch metabolic network in Arabidopsis leaves. Plant J. 58, 485–498 (2009).

Fan, S. K. et al. Effects of split applications of nitrogen fertilizers on the Cd level and nutritional quality of Chinese cabbage. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 18, 897–905 (2017).

Gao, L. W. et al. Genome-wide analysis of auxin transport genes identifies the hormone responsive patterns associated with leafy head formation in Chinese cabbage. Sci. Rep. 7, 42229 (2017).

Jin, C. et al. Carbon dioxide enrichment by composting in greenhouses and its effect on vegetable production. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 172, 418–424 (2009).

Arendsee, Z. W., Li, L. & Wurtele, E. S. Coming of age: orphan genes in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 19, 698–708 (2014).

Yao, C., Yan, H., Zhang, X. & Wang, R. A database for orphan genes in Poaceae. Exp. Ther. Med. 14, 2917–2924 (2017).

Zhao, Y. Establishment of Agrobacterium-mediated transformation system in Chinese Cabbage. MSc thesis, Shenyang Agricultural Univ. (2017).

Bortesi, L. et al. Patterns of CRISPR/Cas9 activity in plants, animals and microbes. Plant Biotechnol. J. 14, 2203–2216 (2016).

Jeong, S. Y. et al. Generation of early-flowering Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa spp. pekinensis) through CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 13, 491–499 (2019).

Zhou, A., Ma, H., Feng, S., Gong, S. & Wang, J. A novel sugar transporter from Dianthus spiculifolius, DsSWEET12, affects sugar metabolism and confers osmotic and oxidative stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 497 (2018).

Cabello, S. et al. Altered sucrose synthase and invertase expression affects the local and systemic sugar metabolism of nematode-infected Arabidopsis thaliana plants. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 201–212 (2014).

Dotto, M., Gómez, M. S., Soto, M. S. & Casati, P. UV-B radiation delays flowering time through changes in the PRC2 complex activity and miR156 levels in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant, Cell Environ. 41, 1394–1406 (2018).

Griffiths, J. et al. Genetic characterization and functional analysis of the GID1 gibberellin receptors in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18, 3399–3414 (2006).

Yu, X. et al. Evaluation of genotypic variation during leaf development in four Cucumis genotypes and their response to high light conditions. Environ. Exp. Bot. 124, 100–109 (2016).

Zhao, D. et al. The role of sugar transporter genes during early infection by root-knot nematodes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 302 (2018).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCt method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

Hall, T. A. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucl. Acids Symp. Ser. 41, 95–98 (1999).

Tamura, K., Stecher, G., Peterson, D., Filipski, A. & Kumar, S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729 (2013).

Chen, C. et al. TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 13, 1194–1202 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31772326) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFD0101802).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.P. and M.J. conceived and designed the experiments. M.J., Z.Z., and H.L. performed the experiments. M.J., Z.Z., H.L., X.D., and Z.P. analyzed the data. M.J. wrote the manuscript and Z.P., F.C., Z.Z., and X.D. revised it. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, M., Zhan, Z., Li, H. et al. Brassica rapa orphan genes largely affect soluble sugar metabolism. Hortic Res 7, 181 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41438-020-00403-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41438-020-00403-z

This article is cited by

-

Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of orphan genes in twelve Musa (sub)species

3 Biotech (2025)

-

CRISPR mediated gene editing for economically important traits in horticultural crops: progress and prospects

Transgenic Research (2025)

-

Role of Brassica orphan gene BrLFM on leafy head formation in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa)

Theoretical and Applied Genetics (2023)