Abstract

A maternal high-fat diet (HFD) is a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases in offspring. The aim of the study was to determine whether maternal HFD causes the epigenetic programming of vascular angiotensin II receptors (ATRs) and leads to heightened vascular contraction in adult male offspring in a sex-dependent manner. Pregnant rats were treated with HFD (60% kcal fat). Aortas were isolated from adult male and female offspring. Maternal HFD increased phenylephrine (PE)-and angiotensin II (Ang II)-induced contractions of the aorta in male but not female offspring. NG-nitro-L-arginine (ʟ-NNA; 100 μM) abrogated the maternal HFD-induced increase in PE-mediated contraction. HFD caused a decrease in endothelium-dependent relaxations induced by acetylcholine in male but not female offspring. However, it had no effect on sodium nitroprusside-induced endothelium-independent relaxations of aortas regardless of sex. The AT1 receptor (AT1R) antagonist losartan (10 μM), but not the AT2 receptor (AT2R) antagonist PD123319 (10 μM), blocked Ang II-induced contractions in both control and HFD offspring in both sexes. Maternal HFD increased AT1R but decreased AT2R, leading to an increased ratio of AT1R/AT2R in HFD male offspring, which was associated with selective decreases in DNA methylation at the AT1aR promoter and increases in DNA methylation at the AT2R promoter. The vascular ratio of AT1R/AT2R was not significantly different in HFD female offspring compared with the control group. Our results indicated that maternal HFD caused a differential regulation of vascular AT1R and AT2R gene expression through a DNA methylation mechanism, which may be involved in HFD-induced vascular dysfunction and the development of a hypertensive phenotype in adulthood in a sex-dependent manner.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, obesity or overweight has been increasing dramatically in developed and developing countries and has become a major public health problem worldwide, which is known as a crucial risk factor for various lifestyle diseases, such as hypertension, coronary heart disease, myocardial hypertrophy, and type 2 diabetes mellitus [1,2,3,4]. Obesity during pregnancy has short- and long-term effects on the health of the offspring as a consequence of “fetal programming”. Numerous studies have supported that the programming effects of obesity or overweight rooted in maternal nutrition lead to energy homeostasis disorders and cardiovascular diseases later in life [5, 6]. Indeed, obesity during pregnancy can cause cardiovascular disorders and hypertension in offspring in different animal models [7,8,9]. A high dietary intake of fat is a major risk factor for the development of obesity. Using a well-established rat model of HFD during pregnancy, we have previously demonstrated that HFD during pregnancy caused cardiac hypertrophy in both fetal and adult male offspring [10, 11]. In addition, maternal HFD impairs endothelial function in primate offspring [12]. However, there is currently a limited mechanistic understanding of how maternal HFD causes fetal programming of cardiovascular diseases.

Angiotensin II (Ang II) is a critical regulator of cardiovascular homeostasis, which has been implicated in hypertension and other cardiovascular dysfunction induced by adverse in utero environments during fetal development [13,14,15]. Ang II mediates its signal transduction and functions by binding to two major G protein-coupled receptors: Ang II type 1 receptor (AT1R) and Ang II type 2 receptor (AT2R). Activation of AT1R mediates many pathophysiological effects, including vasoconstriction and cardiac remodeling. AT2R is thought to oppose the effects of AT1R, although AT2R-mediated actions in the cardiovascular system are controversial. In an animal model of prenatal nicotine, Ang II-mediated vascular contractility was enhanced in adult male offspring exposed in utero to nicotine [16]. In addition, maternal HFD programmed hypertension in adult offspring, which was related to the activation of the adipose renin–angiotensin system (RAS) [17]. Furthermore, according to previous reports, oral administration of AT1R antagonists in early postnatal life after protein restriction in utero prevented the development of hypertension in adult offspring, implicating the RAS in this process [18, 19]. These studies suggest a link between programming of the Ang II receptor to fetal insults and cardiovascular dysfunction later in life. However, whether maternal HFD alters vascular Ang II receptor expression patterns in offspring remains to be elucidated.

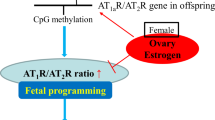

Recent studies demonstrated that DNA methylation, a fundamental epigenetic modification of gene expression, plays important roles in fetal programming of cardiovascular diseases and occurs at the cytosine in the CpG dinucleotide [20,21,22,23]. Methylation in promoter regions is generally associated with the repression of transcription, resulting in a shutdown of the associated gene. A previous study showed that a prenatal low-protein diet causes the development of hypertension in rat offspring because of epigenetic modification of the RAS [24, 25]. Thus, the present study tested the hypothesis that maternal HFD causes a differential epigenetic regulation of AT1aR and AT2R gene expression patterns via a DNA methylation mechanism, leading to an increased risk of hypertension in adult offspring. To investigate the potential sex effects of maternal HFD, studies were performed in both adult male and female offspring.

Methods

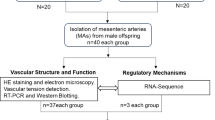

Experimental animals

Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from Guangdong Medical Laboratory Animal Center and housed under specific pathogen-free conditions and maintained on a 12 h:12 h light/dark cycle at 25 °C. Pregnant rats were fed either a standard chow diet (control group, 15% fat, 27% protein, and 58% carbohydrate) or a high-fat diet (HFD group, 60% fat, 20% protein, 20% carbohydrate, and D12492) from days 1 to 21 of gestation. At term, dams were allowed to deliver, and litters were standardized to 8 pups. All offspring were fed a standard chow diet and studied at 3 months of age. All animal experiments in the present study were approved in advance by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Guangzhou Medical University (nos. GY2017-067, 10/17/2017).

Contractions of aortic rings

Aortas with endothelial integrity from adult offspring were isolated and cut into 4 mm rings. Segments were suspended in 10 ml tissue baths containing modified Krebs solution and gassed with a mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2, as described previously [26, 27]. After 60 min of equilibration, each ring was stretched to the optimal resting tension (1.5 g/mm2) as determined in 120 mM KCl before adding drugs. The contraction induced by the drugs was normalized to the KCl-elicited contraction. Induced contractions were obtained following the cumulative addition of Ang II or phenylephrine (PE). In certain experiments, some tissues were pretreated for 20 min with the nonspecific NO synthase inhibitor (NG-nitro-L-arginine, ʟ-NNA; 100 µM), followed by cumulative addition of PE or Ang II. Some tissues were pretreated for 20 min with the AT1R inhibitor losartan (10 µM) or the AT2R inhibitor PD123319 (10 µM), followed by cumulative addition of Ang II, as described in a previous study [16, 27]. For relaxation studies, the segments were submaximally preconstricted with 1 μM PE (male control: 2.02 ± 0.12 g/mm2, male HFD: 3.92 ± 0.06 g/mm2, female control: 3.18 ± 0.08 g/mm2, female HFD: 3.14 ± 0.08 g/mm2), followed by ACh or SNP added in a cumulative manner.

Western immunoblotting analysis

Aortas with endothelial integrity were homogenized in lysis buffer (cell lysis buffer, CST) and incubated for 1 h on ice. Homogenates were then centrifuged at 4 °C for 15 min at 12,000 × g, and supernatants were collected. Protein concentrations were measured using a protein assay kit (Thermo). Samples were loaded in each lane for electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinyl difluoride membranes (Millipore, MA). The membranes were incubated overnight with primary antibodies against AT1R (1:2000 dilution, ab124734, 41 kDa, Abcam) and AT2R (1:2000 dilution, ab92445, 41 kDa, Abcam). After washing, membranes were incubated with secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies and visualized with chemiluminescence reagents, and blots were exposed to Hyperfilm. The band intensities were analyzed by densitometry (Bio-Rad image software) and normalized to GAPDH as an internal control.

Real-time RT-PCR

RNA was extracted from aortic rings with endothelium integrity using the TRIzol protocol (Invitrogen). AT1aR, AT1bR, and AT2R mRNA abundance was determined by real-time RT-PCR using thermal cycler block (Applied Biosystems). The primers used were AT1aR (Gene ID: 24180), 5′-ggagaggattcgtggcttgag-3′ (forward) and 5′-ctttctgggagggttgtgtgat-3′ (reverse); AT1bR (Gene ID: 81638), 5′-atgtctccagtcccctctca-3′ (forward) and 5′-tgacctcccatctccttttg-3′ (reverse); and AT2R (Gene ID: 24182), 5′-caatctggctgtggctgactt-3′ (forward) and 5′-tgcacatcacaggtccaaag-3′ (reverse). Real-time RT-PCR was performed in a final volume of 20 µl. Each PCR mixture consisted of primers, SYBR® Premix Ex Taq II (TliRNaseH Plus) and ROX Reference Dye (Takara). We used the following RT-PCR protocol: 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 10 s. GAPDH was used as an internal reference. Each sample was assayed in triplicate, and the threshold cycle numbers were averaged. The mRNA of target genes was quantified using the ΔΔCт method and normalized to GAPDH mRNA levels.

Pyrosequencing for quantitative measurement of DNA methylation

Genomic DNA was extracted from the aorta of 3-month-old male offspring by a QIAGEN DNeasy kit (69506, QIAGEN) and treated by bisulfite conversion with a QiagenEpiTect Bisulfite Kit (59104, QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. CpG methylation at the AT1aR and AT2R gene promoters was determined using pyrosequencing analysis (PyroMark Q96 ID, QIAGEN). Primers for pyrosequencing assays were designed by PyroMark Assay Design 2.0 software. The primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance (P < 0.05) was determined by analysis of variance followed by Neuman–Keuls post hoc testing or Student’s t test, where appropriate.

Results

Effect of maternal HFD on PE-induced contractions in adult male and female offspring

Our previous study reported that maternal HFD had no significant effect on litter size. There was a decrease in birthweight in the HFD group compared to the control group [10, 11]. In addition, maternal HFD had no effect on the sex ratio (1.13 ± 0.12 vs. 1.04 ± 0.19, p > 0.05). Maternal HFD had no effect on KCl-induced contractions of aortas in adult male (1.61 ± 0.03 vs. 1.68 ± 0.03 g/mm2) and female (1.77 ± 0.05 vs. 1.71 ± 0.04 g/mm2) offspring. PE produced a concentration-dependent vasoconstriction in all vessels. Figure 1a shows the effect of maternal HFD on PE-mediated concentration-dependent contractions of aortas in the absence or presence of the eNOS inhibitor ʟ-NNA in adult male offspring. In the absence of ʟ-NNA, both pD2 and the maximal response (Emax) were significantly increased in the aorta of HFD male offspring compared with those of the control group (Table 1). However, in the presence of ʟ-NNA, maternal HFD had no effect on PE-induced contractions (Fig. 1a, Table 1). In the control rats, inhibition of eNOS with ʟ-NNA significantly potentiated PE-induced contractions (Fig. 1a, Table 1). In contrast, in the HFD groups, ʟ-NNA had no effect on PE-mediated contractions (Fig. 1a, Table 1).

Effect of maternal HFD on phenylephrine (PE) and angiotensin II (Ang II)-mediated contractions of aortas in adult male and female offspring. PE (a, b n = 5/group)- or Ang II (c, d n = 6/group)-induced contractions in the absence or presence of ʟ-NNA (100 µM, 20 min) were determined in aortas of adult male (left panel) and female (right panel) offspring that had been exposed in utero to a standard laboratory chow diet or HFD. Con control, HFD high-fat diet. The pD2 values and the maximal response (Emax) are presented in Table 1. Values are the means ± SEM. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, HFD vs. Con; #P < 0.05, +ʟ-NNA vs. −ʟ-NNA

In contrast to male offspring, there was no significant difference in PE-induced contractions between the control and HFD female offspring in the absence or presence of ʟ-NNA (Fig. 1b, Table 1). In addition, ʟ-NNA increased PE-induced contractions in both the control and HFD female offspring (Fig. 1b, Table 1).

Effect of maternal HFD on Ang II-induced contractions of aortas in adult male and female offspring

As shown in Fig. 1c and Table 1, in the absence of ʟ-NNA, the maximal response of Ang II-induced contractions was significantly increased in the aortas of HFD-treated male offspring compared with that of the control group. Similarly, in the presence of ʟ-NNA, maternal HFD also increased Ang II-induced contraction. In both male control and HFD-treated offspring, ʟ-NNA significantly potentiated Ang II-induced contractions (Fig. 1c, Table 1).

In contrast to the finding in the male offspring, maternal HFD had no effect on Ang II-induced contractions of the aorta in adult female offspring, regardless of ʟ-NNA treatment (Fig. 1d, Table 1). As shown in Fig. 1d and Table 1, ʟ-NNA increased Ang II-induced maximal contractions of the aorta from control and HFD female adult offspring.

Effect of losartan and PD123319 on Ang II-induced contractions in both control and HFD offspring

To determine the receptor subtype of Ang II-induced vascular contractions, aortic rings were pretreated with losartan (AT1R inhibitor) or PD123319 (AT2R inhibitor). Losartan almost completely blocked Ang II-induced contractions in both the control (Fig. 2a, c) and HFD groups (Fig. 2b, d) in both sexes. However, PD123319 had no significant effect on Ang II-induced contractions in the control and HFD offspring regardless of sex (Fig. 2).

Effect of losartan and PD123319 on angiotensin II (Ang II)-induced contractions of aortas in adult male and female offspring. Ang II-induced contractions in the absence or presence of losartan or PD123319 (PD) were determined in aortas from male (a, b) and female (c, d) offspring that had been exposed in utero to a high-fat diet or standard laboratory chow diet. a control male group (n = 5/group); b HFD male group (n = 5/group); c control female group (n = 5/group); d HFD female group (n = 5/group). Con control, HFD high-fat diet. Values are the means ± SEM. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05. Ang II vs. Ang II + losartan

Effect of maternal HFD on endothelium-dependent and endothelium-independent relaxation in male and female offspring

To determine the effect of maternal HFD on endothelium-dependent relaxation in male and female adult offspring, ACh-induced relaxation was examined (Fig. 3, top). Maternal HFD significantly decreased the maximal relaxation induced by ACh in adult male (75.03 ± 2.43 vs. 44.73 ± 2.27) but not female offspring (77.59 ± 4.15 vs. 78.30 ± 3.30) (Fig. 3, top).

Effect of maternal HFD on the acetylcholine (Ach)- or sodium nitroprusside (SNP)-induced relaxation of aortas from adult male and female offspring. Aortic rings were pretreated with 1 µM phenylephrine (PE), followed by a cumulative addition of Ach (n = 6/group) or SNP (n = 5/group). Con control, HFD high-fat diet. Values are the means ± SEM. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, HFD vs. Con

Unlike ACh, there was no significant difference in SNP-induced endothelium-independent relaxations between the control and HFD offspring in either sex (Fig. 3, bottom).

Effect of maternal HFD on AT1R and AT2R expression in adult male and female offspring

As shown in Fig. 4a, b, maternal HFD increased AT1R protein and AT1aR mRNA but decreased AT2R protein and mRNA, resulting in a significant increase in the ratio of AT1R/AT2R in adult male offspring.

Effect of maternal HFD on AT1R and AT2R expression in the aorta of adult male and female offspring. AT1R and AT2R protein levels were determined by western blotting in aortas from adult male (a) and female (c) offspring. AT1R and AT2R mRNA levels were determined by real-time RT-PCR in aortas from adult male (b) and female (d) offspring. Con control, HFD high-fat diet. Values are the means ± SEM. Data were analyzed by Student’s t test. *P < 0.05, HFD vs. Con, n = 4/group

In contrast to the finding in male offspring, the AT2R protein level and mRNA abundance were significantly increased in the aortas from the HFD female group compared with levels from the control female group (Fig. 4c, d). The AT1R protein level and AT1aR mRNA abundance were also increased in the HFD group, resulting in no significant difference in the AT1R/AT2R ratio between the control and HFD groups in female offspring (Fig. 4c, d).

Effect of maternal HFD on the DNA methylation of the CpG locus at the AT1aR and AT2R promoters in adult male offspring

Previous studies have indicated that alteration of the CpG methylation in transcription factor binding sites in the promoter of genes plays a vital role in epigenetic modification of gene expression in the fetal programming of cardiovascular diseases [28]. The transcription factor binding sites located in the CpG locus at the AT1aR and AT2R gene promoters were identified in a previous study [29]. As shown in Fig. 5a, the methylation levels of the CpG locus at Sp1 transcription factor binding site (−96), CREB binding site (−150), and ERα and β binding site (−484) of the AT1aR promoter were significantly decreased in the aortas of adult male HFD offspring compared with the control. However, maternal HFD did not alter the methylation of the GATA-1 binding site (−809) at the AT1aR gene promoter region (Fig. 5a). In contrast to the alteration of AT1aR, maternal HFD significantly increased the methylation levels of the CpG locus at the CREB binding site (−444), GRE binding site (+11), and CpG site (−52) near the TATA box (Fig. 5b).

Effect of maternal HFD on the DNA methylation of the CpG locus at the AT1aR and AT2R promoters of aortas from adult male offspring. Aortic rings were freshly isolated from male adult offspring that had been exposed in utero to a high-fat diet or standard laboratory chow diet. DNA was isolated, and methylation levels were determined by pyrosequencing. Con control, HFD high-fat diet. Values are the means ± SEM. Data were analyzed by Student’s t test. *P < 0.05, HFD vs. Con, n = 5/group

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated the effect of a maternal HFD on vascular contractility and the underlying mechanisms in postnatal life. The major findings of the present study are as follows: (1) vascular function was impaired due to maternal HFD exposure, manifested as enhanced contractility and depressed endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation in male but not female offspring; (2) maternal HFD differentially regulated AT1R and AT2R expression in the aorta in adult offspring in a sex-specific manner; and (3) the differential regulation of AT1aR and AT2R gene expression via a DNA methylation mechanism may be involved in maternal HFD-induced heightened vasoconstriction and the development of a hypertensive phenotype later in life.

The present study reported that maternal HFD increased PE-induced contraction of the aorta in male offspring, which is consistent with recent studies in human and animal models showing that adverse intrauterine environments contributed to an increased risk of hypertension in adulthood [30,31,32,33,34]. In control male offspring, the aorta showed a significant increase in PE after inhibition of eNOS by ʟ-NNA, indicating basal eNOS activity in the regulation of vascular reactivity. However, ʟ-NNA had no effect on PE-mediated vascular constriction in HFD male offspring. In addition, there was no significant difference in PE-induced contraction between control and HFD male offspring in the presence of ʟ-NNA. These findings suggested that the increased PE-induced aortic contraction in male HFD offspring may be primarily due to the loss of eNOS-mediated vasodilation. The present study also demonstrated that maternal HFD increased Ang II-induced contraction in the absence or presence of ʟ-NNA. ʟ-NNA enhanced Ang II-induced contraction in both control and HFD offspring. A similar finding has been demonstrated in male offspring exposed to nicotine before birth [16]. Therefore, it is likely that fetal programming of eNOS activity and its effect on vasoconstrictors is agonist dependent.

It is well known that endothelium-dependent vasodilatation is a vital measurement of endothelial function. Commonly, in response to certain physiological or pharmacological stimuli, impaired arteries have a decreased capacity to dilate fully. Our findings showed that maternal HFD caused a nearly 50% reduction in vasorelaxation in response to the endothelium-dependent vasodilator ACh in male adult offspring. However, maternal HFD had no effect on SNP-induced relaxation in adult male offspring. These findings suggested that maternal HFD caused impaired endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation. It has been reported that adverse intrauterine environments may cause a reduction in endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation in offspring in both human and animal models [12, 35].

AT1R is primarily expressed in various tissues, including vascular smooth muscle, endothelium, and heart, mediating most of the physiological actions of Ang II. A previous study showed that in endothelial cells (ECs), AT1R signaling mediates endothelial dysfunction via inhibition of nitric oxide (NO) production [36]. Vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) are critically involved in maintaining vascular integrity and tone, which contribute to arterial remodeling through various processes, including growth/apoptosis and inflammation. Ang II acts on VSMCs via AT1R, leading to an increase in intracellular Ca2+, which then causes vasoconstriction [15]. In contrast to AT1R, AT2R is highly expressed only in the fetus, including early ECs, and declines to an undetectable level after birth. AT2R is upregulated during certain diseases, and the effect of AT2R remains controversial. It has been reported that AT2R can promote vasorelaxation by activating endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) or NO-cGMP production in ECs and VSMCs [37]. However, AT2R stimulation induced vasoconstriction in mesenteric arteries from spontaneously hypertensive rats [36]. In the present study, we found that the AT1R blocker losartan, not the AT2R blocker PD123319, almost completely blocked Ang II-induced contractions of the aorta from both the control and HFD groups in both sexes, indicating a primary role of AT1R in Ang II-induced vascular tension. Similar findings in other animal models showed that AT1R plays a key role in Ang II-increased vascular constriction [16, 38]. Western blotting added new and supportive evidence that maternal HFD significantly increased AT1R protein but decreased AT2R protein expression, resulting in a significant increase in the ratio of AT1R/AT2R in the vessels of male offspring. This is likely to contribute to the increased vascular sensitivity to Ang II in male offspring exposed to HFD before birth. In addition, there is an increase in AT1aR mRNA but a decrease in AT2R mRNA in the vessels of adult male HFD offspring compared with control offspring, indicating that maternal HFD-induced alteration of AT1R and AT2R protein levels is primarily regulated at the transcriptional level. Unlike AT1R, the exact role and the extent to which AT2R plays a role in the regulation of vascular constriction remain unclear. Previous studies have reported that AT2R activation induces vasodilation in normotensive rats but induces vasoconstriction in pathological states of the vasculature [37, 39,40,41,42]. A previous study also showed that there is an upregulation of AT1R and downregulation of AT2R in spontaneously hypertensive rats [43, 44]. Taken together, these findings suggest the crucial role of an increase in the ratio of AT1R/AT2R in the development of the hypertensive phenotype. Given that eNOS and cyclooxygenase (COX) are important mediators of the Ang II effects on ECs, precise studies of the NO pathway, and COX are warranted in the future to further evaluate potential endothelium-dependent mechanisms underlying the observed alterations in the present study. A previous study showed that maternal and early postnatal HFD exposure impairs endothelial function of the abdominal aorta by decreasing NO bioactivity in nonhuman primate offspring [12]. In addition, Gray also reported that maternal high-fat intake significantly decreased eNOS levels but had no effect on COX-1 and COX-2 expression in resistance vessels in adult male offspring [45].

It has been demonstrated that perinatal insults increase disease susceptibility later in life via epigenetic modifications. DNA methylation is one of the major mechanisms for epigenetic modification of gene expression, which occurs at the cytosine in CpG dinucleotides. Methylation of CpG islands in gene promoters is associated with transcriptional repression [46, 47]. According to the molecular biology database NCBI, AT1aR, and AT2R do not have CG islands or repeated CG sites for methylation. However, previous studies have indicated that alteration of CpG methylation in transcription factor binding sites of gene promoters plays a vital role in the epigenetic modification of gene expression patterns in response to different intrauterine insults [28, 48]. Several CpG sites at transcription factor binding sites in the AT1aR and AT2R promoters have been demonstrated. Of these CpG sites, the methylation levels at the −96, −150, and −484 CpG loci at the AT1aR promoter were significantly decreased in the aorta of adult male offspring compared with the control offspring, indicating that maternal HFD-induced upregulation of aortic AT1aR may primarily be due to the hypomethylation of these CpG loci of the AT1aR promoter. A previous study demonstrated that perinatal nicotine decreased sequence-specific CpG methylation at the SP1 and ERα and β binding sites of the AT1aR promoter, resulting in increased transcription factor binding affinity and activity of the AT1aR promoter [49]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the effect of fetal stress on DNA methylation is tissue specific, gene specific, species specific, and sex specific [21, 49, 50]. Unlike hypomethylation at specific CpGs in the AT1aR promoter, maternal HFD significantly increased the methylation levels at the −444, −52, and +11 CpG loci at the AT2R promoter in male offspring arteries, giving rise to the downregulation of AT2R in male offspring, suggesting that the effect of maternal HFD on DNA methylation is at least gene dependent.

In contrast to the male offspring, PE-induced aortic constriction was not affected in the female offspring of HFD-treated rats in the absence or presence of ʟ-NNA. In addition, maternal HFD had no effect on Ang II-mediated vascular contraction in female offspring. Furthermore, there was no significant difference in ACh- or SNP-induced vasorelaxation in HFD female offspring compared with the control group. Our results indicate that there was sexual dimorphism in the abnormalities of vascular function and are consistent with previous findings that perinatal undernutrition caused increased blood pressure levels only in male offspring [51]. However, Woodall et al. considered male and female offspring as no sex differences were apparent in offspring of the control or restricted diet group [52]. In an animal model of a maternal low-protein diet, female offspring developed more severe hypertension than male offspring [53]. These findings suggest differential sex mechanisms of fetal programming of hypertension caused by an adverse intrauterine environment. Although the results of sex dimorphism are conflicting, male offspring are generally more susceptible than females to the manifestation of cardiovascular disease caused by intrauterine insults. It is likely that various mechanisms are involved in the sex-specific effect induced by maternal HFD. In the present study, we found that maternal HFD increased AT1R but decreased AT2R, resulting in an increased AT1R/AT2R ratio in male offspring. However, maternal HFD had no effect on vascular function in adult female offspring, which was related to a lack of change in the AT1R/AT2R ratio. Further studies of the precise underlying mechanisms of the sex differences in maternal HFD-induced vascular dysfunction are warranted. The present study demonstrated that maternal HFD decreased the methylation of ERα and β binding sites at the AT1aR promoter, suggesting that estrogen/its receptor (ER) may interact with the Ang II receptor by regulating DNA methylation patterns at the gene promoter, resulting in the protection of female offspring from the development of hypertension.

In summary, the current study provides new information on the molecular mechanism of how prenatal exposure to HFD could reprogram vascular functions later in life. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1 (diagram), maternal HFD causes programming of vascular AT1aR and AT2R gene expression by altered methylation of specific CpGs at the AT1aR and AT2R promoters, contributing to the heightened vascular contractility in adult male offspring in a sex-dependent manner. Given the current global overnutrition and obesity epidemic and the increasing prevalence of obese pregnant women, further mechanistic studies and the potential roles of sex hormones in maternal HFD-mediated programming of adult vascular reactivity are warranted. Therefore, our findings emphasize the importance of a balanced diet during pregnancy and the potential targeting of therapeutic interventions in early life to reduce the prevalence of obesity.

References

Jung S. Implications of publicly available genomic data resources in searching for therapeutic targets of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Exp Mol Med. 2018;50:43.

Forno E, Young OM, Kumar R, Simhan H, Celedon JC. Maternal obesity in pregnancy, gestational weight gain, and risk of childhood asthma. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e535–46.

Costa RM, Neves KB, Tostes RC, Lobato NS. Perivascular adipose tissue as a relevant fat depot for cardiovascular risk in obesity. Front Physiol. 2018;9:253.

Sonoda C, Fukuda H, Kitamura M, Hayashida H, Kawashita Y, Furugen R, et al. Associations among obesity, eating speed, and oral health. Obes Facts. 2018;11:165–75.

Loche E, Blackmore HL, Carpenter AA, Beeson JH, Pinnock A, Ashmore TJ, et al. Maternal diet-induced obesity programmes cardiac dysfunction in male mice independently of post-weaning diet. Cardiovasc Res. 2018;114:1372–84.

Ghnenis AB, Odhiambo JF, McCormick RJ, Nathanielsz PW, Ford SP. Maternal obesity in the ewe increases cardiac ventricular expression of glucocorticoid receptors, proinflammatory cytokines and fibrosis in adult male offspring. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0189977.

Miranda A, Sousa N. Maternal hormonal milieu influence on fetal brain development. Brain Behav. 2018;8:e00920.

Lock MC, Botting KJ, Tellam RL, Brooks D, Morrison JL. Adverse intrauterine environment and cardiac miRNA expression. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:2628.

Jawerbaum A, White V. Review on intrauterine programming: consequences in rodent models of mild diabetes and mild fat overfeeding are not mild. Placenta. 2017;52:21–32.

Xue Q, Chen P, Li X, Zhang G, Patterson AJ, Luo J. Maternal high-fat diet causes a sex-dependent increase in AGTR2 expression and cardiac dysfunction in adult male rat offspring. Biol Reprod. 2015;93:49.

Xue Q, Chen F, Zhang H, Liu Y, Chen P, Patterson AJ, et al. Maternal high-fat diet alters angiotensin ii receptors and causes changes in fetal and neonatal rats. Biol Reprod. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/biolre/ioy262).

Fan L, Lindsley SR, Comstock SM, Takahashi DL, Evans AE, He GW, et al. Maternal high-fat diet impacts endothelial function in nonhuman primate offspring. Int J Obes. 2013;37:254–62.

de Kloet AD, Steckelings UM, Sumners C. Protective angiotensin type 2 receptors in the brain and hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2017;19:46.

Nishiyama A, Kobori H. Independent regulation of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in the kidney. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2018;22:1231–9.

Eguchi S, Kawai T, Scalia R, Rizzo V. Understanding angiotensin II type 1 receptor signaling in vascular pathophysiology. Hypertension. 2018;71:804–10.

Xiao D, Xu Z, Huang X, Longo LD, Yang S, Zhang L. Prenatal gender-related nicotine exposure increases blood pressure response to angiotensin II in adult offspring. Hypertension. 2008;51:1239–47.

Guberman C, Jellyman JK, Han G, Ross MG, Desai M. Maternal high-fat diet programs rat offspring hypertension and activates the adipose renin-angiotensin system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:262.e1–8.

Szczepanska-Sadowska E, Czarzasta K, Cudnoch-Jedrzejewska A. Dysregulation of the renin-angiotensin system and the vasopressinergic system interactions in cardiovascular disorders. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2018;20:19.

Sherman RC, Langley-Evans SC. Early administration of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor captopril, prevents the development of hypertension programmed by intrauterine exposure to a maternal low-protein diet in the rat. Clin Sci. 1998;94:373–81.

Moore LD, Le T, Fan G. DNA methylation and its basic function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:23–38.

Kader F, Ghai M, Maharaj L. The effects of DNA methylation on human psychology. Behav Brain Res. 2018;346:47–65.

Thomas ML, Marcato P. Epigenetic modifications as biomarkers of tumor development, therapy response, and recurrence across the cancer care continuum. Cancers. 2018;10:101.

Stoll S, Wang C, Qiu H. DNA methylation and histone modification in hypertension. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:1174.

Bogdarina I, Welham S, King PJ, Burns SP, Clark AJ. Epigenetic modification of the renin-angiotensin system in the fetal programming of hypertension. Circ Res. 2007;100:520–6.

Langley-Evans SC, Sherman RC, Welham SJ, Nwagwu MO, Gardner DS, Jackson AA. Intrauterine programming of hypertension: the role of the renin-angiotensin system. Biochem Soc Trans. 1999;27:88–93.

Xue Q, Ducsay CA, Longo LD, Zhang L. Effect of long-term high-altitude hypoxia on fetal pulmonary vascular contractility. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104:1786–92.

Xiao D, Huang X, Lawrence J, Yang S, Zhang L. Fetal and neonatal nicotine exposure differentially regulates vascular contractility in adult male and female offspring. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320:654–61.

Patterson AJ, Xiao D, Xiong F, Dixon B, Zhang L. Hypoxia-derived oxidative stress mediates epigenetic repression of PKCepsilon gene in foetal rat hearts. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;93:302–10.

Xue Q, Patterson AJ, Xiao D, Zhang L. Glucocorticoid modulates angiotensin II receptor expression patterns and protects the heart from ischemia and reperfusion injury. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e106827.

Chiossi G, Costantine MM, Tamayo E, Hankins GD, Saade GR, Longo M. Fetal programming of blood pressure in a transgenic mouse model of altered intrauterine environment. J Physiol. 2016;594:7015–25.

Sakuyama H, Katoh M, Wakabayashi H, Zulli A, Kruzliak P, Uehara Y. Influence of gestational salt restriction in fetal growth and in development of diseases in adulthood. J Biomed Sci. 2016;23:12.

Paixao AD, Alexander BT. How the kidney is impacted by the perinatal maternal environment to develop hypertension. Biol Reprod. 2013;89:144.

Chong E, Yosypiv IV. Developmental programming of hypertension and kidney disease. Int J Nephrol. 2012;2012:760580

Katkhuda R, Peterson ES, Roghair RD, Norris AW, Scholz TD, Segar JL. Sex-specific programming of hypertension in offspring of late-gestation diabetic rats. Pediatr Res. 2012;72:352–61.

Taylor PD, Khan IY, Hanson MA, Poston L. Impaired EDHF-mediated vasodilatation in adult offspring of rats exposed to a fat-rich diet in pregnancy. J Physiol. 2004;558:943–51.

Kawai T, Forrester SJ, O’Brien S, Baggett A, Rizzo V, Eguchi S. AT1 receptor signaling pathways in the cardiovascular system. Pharm Res. 2017;125:4–13.

Carey RM. AT2 receptors: potential therapeutic targets for hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2017;30:339–47.

Tao H, Rui C, Zheng J, Tang J, Wu L, Shi A, et al. Angiotensin II-mediated vascular changes in aged offspring rats exposed to perinatal nicotine. Peptides. 2013;44:111–9.

Gong WK, Lu J, Wang F, Wang B, Wang MY, Huang HP. Effects of angiotensin type 2 receptor on secretion of the locus coeruleus in stress-induced hypertension rats. Brain Res Bull. 2015;111:62–8.

Hagihara GN, Lobato NS, Filgueira FP, Akamine EH, Aragao DS, Casarini DE, et al. Upregulation of ERK1/2-eNOS via AT2 receptors decreases the contractile response to angiotensin II in resistance mesenteric arteries from obese rats. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e106029.

Hiyoshi H, Yayama K, Takano M, Okamoto H. Angiotensin type 2 receptor-mediated phosphorylation of eNOS in the aortas of mice with 2-kidney, 1-clip hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;45:967–73.

Widdop RE, Matrougui K, Levy BI, Henrion D. AT2 receptor-mediated relaxation is preserved after long-term AT1 receptor blockade. Hypertension. 2002;40:516–20.

Touyz RM, Endemann D, He G, Li JS, Schiffrin EL. Role of AT2 receptors in angiotensin II-stimulated contraction of small mesenteric arteries in young SHR. Hypertension. 1999;33:366–72.

Cheng HF, Wang JL, Vinson GP, Harris RC. Young SHR express increased type 1 angiotensin II receptors in renal proximal tubule. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:F10–7.

Gray C, Harrison CJ, Segovia SA, Reynolds CM, Vickers MH. Maternal salt and fat intake causes hypertension and sustained endothelial dysfunction in fetal, weanling and adult male resistance vessels. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9753.

Weber M, Hellmann I, Stadler MB, Ramos L, Paabo S, Rebhan M, et al. Distribution, silencing potential and evolutionary impact of promoter DNA methylation in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2007;39:457–66.

Wan J, Oliver VF, Wang G, Zhu H, Zack DJ, Merbs SL, et al. Characterization of tissue-specific differential DNA methylation suggests distinct modes of positive and negative gene expression regulation. BMC Genom. 2015;16:49.

Xiong F, Xiao D, Zhang L. Norepinephrine causes epigenetic repression of PKCepsilon gene in rodent hearts by activating Nox1-dependent reactive oxygen species production. FASEB J. 2012;26:2753–63.

Xiao D, Dasgupta C, Li Y, Huang X, Zhang L. Perinatal nicotine exposure increases angiotensin II receptor-mediated vascular contractility in adult offspring. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e108161.

Tost J, Gut IG. Analysis of gene-specific DNA methylation patterns by pyrosequencing technology. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;373:89–102.

Kwong WY, Wild AE, Roberts P, Willis AC, Fleming TP. Maternal undernutrition during the preimplantation period of rat development causes blastocyst abnormalities and programming of postnatal hypertension. Development. 2000;127:4195–202.

Woodall SM, Breier BH, Johnston BM, Bassett NS, Barnard R, Gluckman PD. Administration of growth hormone or IGF-I to pregnant rats on a reduced diet throughout pregnancy does not prevent fetal intrauterine growth retardation and elevated blood pressure in adult offspring. J Endocrinol. 1999;163:69–77.

Goyal R, Longo LD. Maternal protein deprivation: sexually dimorphic programming of hypertension in the mouse. Hypertens Res. 2013;36:29–35.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Guiping Zhang for technical guidance. This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2018A030313719) and the Guangzhou Education Bureau (1201410365).

Funding

This study was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2018A030313719) and the Guangzhou Education Bureau (1201410365).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, F., Cao, K., Zhang, H. et al. Maternal high-fat diet increases vascular contractility in adult offspring in a sex-dependent manner. Hypertens Res 44, 36–46 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-0519-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-0519-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Parental diet and offspring health: a role for the gut microbiome via epigenetics

Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology (2025)

-

Maternal exercise upregulates the DNA methylation of Agtr1a to enhance vascular function in offspring of hypertensive rats

Hypertension Research (2023)

-

Maternal nutrition and effects on offspring vascular function

Pflügers Archiv - European Journal of Physiology (2023)

-

Estrogen normalizes maternal HFD-induced vascular dysfunction in offspring by regulating ATR

Hypertension Research (2022)

-

Effect of estrogen on fetal programming in offspring from high-fat-fed mothers

Hypertension Research (2022)