Abstract

Coronary artery calcification (CAC), a marker of atherosclerosis, is predictive of incident hypertension based on the 2017 ACC/AHA high blood pressure guidelines. We performed a large cohort study to investigate whether incident hypertension could be predicted from CAC measurements as a measure of atherosclerosis, even when updated hypertension criteria are applied. A total of 27,918 male subjects who underwent CAC examination during a health screening program between 2011 and 2017 were enrolled. According to the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines, hypertension was defined as 130/80 mmHg. Cox proportional hazard analysis was used to assess the risk of incident hypertension according to CAC categories (CAC = 0, 1–10, 11–100, >100). After exclusion, 14,335 subjects were included (mean age 40.0 [5.7] years). During the follow-up period (median 3.63 years), 3050 subjects (21.3%) developed hypertension. The subjects in the highest CAC category showed an increased risk of hypertension compared with the lowest CAC category, as confirmed by multivariate adjusted hazard ratios of 1.27 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01–1.60; P < 0.001). The increased risk of developing hypertension was consistent after adjustments were made for several confounding factors. The CAC score, a marker of atherosclerosis, is positively associated with incident hypertension according to the updated 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High blood pressure (BP) is the strongest and most common modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular events and mortality [1,2,3]. Thus, the early detection or prediction of hypertension (HTN) is important from the perspective that cardiovascular disease is a leading cause of mortality, disability, and global healthcare costs [4].

Coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring using computed tomography (CT) is a useful and reliable marker of coronary atherosclerosis [5]. CAC scores reflect the long-term effects of elevated CVD risk factors and are an independent predictor of future CVD events in individuals spanning a wide range of ages, including asymptomatic adults [5, 6]. CAC scores have a direct, continuous relation with total coronary plaque burden in histology [7], and the severity of coronary artery disease [8].

In a previous study, CAC was found to have a significant association with incident HTN; the presence and severity of CAC at baseline were associated with incident HTN in multivariable models that were adjusted for traditional risk factors [9, 10].

The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) recently released revised guidelines for HTN with lower BP thresholds than those in the previous guidelines (systolic blood pressure [SBP] ≥130 vs. 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure [DBP] ≥80 vs. 90 mmHg) [11, 12]. These changes are expected to increase the prevalence of patients with HTN, especially in higher-risk populations compared with the general population [13].

No previous studies have demonstrated an association between subclinical atherosclerotic burden and BP levels in the new guidelines, especially in a young population. Therefore, we aimed to determine whether CAC, a marker of atherosclerosis, is a predictor of incident HTN in a large sample of apparently healthy young Korean men who participate in a regular health checkup program.

Methods

Study population

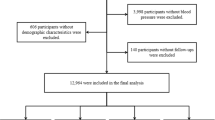

The Kangbuk Samsung Health Study is a cohort of Korean adult men and women who underwent annual or biennial comprehensive health examinations at the two Kangbuk Samsung Hospital Total Healthcare Centers located in Seoul and Suwon, South Korea. This study population included 27,918 male subjects who had CAC data and visited at least twice during 2010–2017. We excluded participants with any missing data (n = 1297), participants with medication for HTN, diabetes mellitus, or dyslipidemia at baseline (n = 3515), and participants with BP ≥ 130/80 (n = 12,197). The final sample included 14,335 participants.

The study was approved by the Kangbuk Samsung Hospital Institutional Review Board, which waived the requirement for informed consent, as we only used deidentified data obtained as part of routine health screening exams.

Data collection

Study participants provided information at each screening visit on medical history, family history, medication use, smoking habits, amount of alcohol intake, education level, and physical activity using a self-administered questionnaire. Anthropometric measurements, including weight and height, were taken at each screening visit by trained medical personnel. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2).

Serum triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and glucose were measured in fasting serum samples at each screening visit. Diabetes was defined as a self-reported physician diagnosis, the self-reported use of insulin or other hypoglycemic agents, or a measured fasting serum glucose ≥126 mg/dl. We measured physical activity levels using the validated Korean version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF) [14], which was part of the self-administered questionnaire. The IPAQ-SF measures the duration and frequency of moderate to vigorous physical activities, including walking, for more than ten consecutive minutes in all contexts (i.e., work, home, and leisure) during a 7-day period [15, 16]. Physical activity was then categorized into three groups: inactive, minimally active (≥3 days of vigorous activity for ≥20 min/day, ≥5 days of moderate intensity activity or walking for ≥30 min/day, or ≥5 days of any combination of walking and moderate intensity or vigorous intensity activities achieving ≥600 MET-minutes/week), and health-enhancing physically active (HEPA; ≥3 or more days of vigorous intensity activity achieving ≥1500 MET-minutes/week, or 7 days of any combination of walking, moderate intensity, or vigorous intensity activities achieving ≥3000 MET-minutes/week).

Blood pressure was measured with an automated oscillometric device (53,000, Welch Allyn, New York, USA) used by trained nurses while participants were in a sitting position with their arm supported at heart level after a 5 min rest. We recorded three consecutive BP readings and used the average of the second and third readings for our analysis. Hypertension (HTN) was defined by SBP ≥ 130 mmHg, DBP ≥ 80 mmHg, or current use of anti-HTN medication [17].

Coronary artery calcium score

CAC scores were measured with a LightSpeed VCT XTe-64 slice MDCT scanner (GE Healthcare, Tokyo, Japan) in both study centers using the same standardized protocol with 2.5 mm slice thickness, 400 ms rotation time, 120 kV tube voltage, and 124 mAS (310 mA × 0.4 s) tube current under ECG-gated dose modulation [9]. CAC scores were estimated using the method proposed by Agatston et al. [18]. The intraclass correlation coefficient for CAC scores was 0.99 [17].

Statistical analysis

Comparisons of baseline characteristics and cardiovascular risk factors for the participants according to HTN were performed using the following analysis method. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test. For continuous variables, Student’s t tests or Mann–Whitney tests were used to compare two groups, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Kruskal–Wallis tests were used for comparison of multiple groups as appropriate. Categorical variables are expressed as the number (%), and continuous variables are expressed as the mean (standard deviation [SD]) or median (interquartile range [IQR]), depending on the distribution of continuous variables.

A Cox proportional hazard analysis model was used to estimate adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for incident HTN, adjusted for confounding factors identified from baseline characteristics.

According to CAC categories, we estimated aHRs for incident HTN by comparing the three highest categories of CAC to the lowest category (reference group). In our analyses, we used four models to adjust for confounding factors: model 1 was adjusted for age, education (college graduate), health-enhancing physical activity (HEPA), current smoking, alcohol consumption (g/day), center, and year; model 2 was further adjusted for BMI and SBP; and model 3 was further adjusted for DBP.

We used Kaplan–Meier estimates to evaluate event rates over time according to CAC score quartiles and used the log-rank test for analysis. The interaction effect between variables was also measured. All P values were two-tailed, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 15.0 (Stata Corp. 2017, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

We followed 14,335 nonhypertensive participants over a median period of 3.65 years (IQR, 2.07–4.81 years; meam ± SD [range], 3.55 ± 1.60 [0.49–7.59]).

The mean participant age was 39.99 ± 5.69. At the end of the follow-up period, 3050 (21.28%) participants developed HTN according to the revised 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines.

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the study population, including metabolic markers divided into normotensive and incident HTN groups. Participants who developed HTN were older (40 ± 5.6 vs. 39.9 ± 5.7 years) and more obese (BMI, 25.1 ± 2.7 vs. 24.2 ± 2.7 kg/m2). Except for HDL-C levels, all metabolic values were significantly higher in the HTN group than in the normotensive group. Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics according to CAC categories. In general, the mean values of SBP and DBP were highest among patients in the top CAC categories. This trend generally held true for other metabolic measurements in the top CAC categories as well.

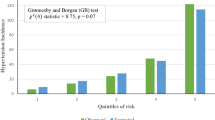

The risk of incident HTN increased progressively across CAC categories (Table 3). In the fully adjusted multivariate models, including adjustments for age, medical center, year of screening examination, smoking status, alcohol intake, exercise, educational level, BMI, SBP, and DBP, the aHR (95% CI) for incident HTN comparing the highest with the lowest (reference group) CAC categories was 1.27 (1.01–1.60). Table 4 shows the risk of incident HTN according to the absence or presence of CAC. The risk of incident HTN increased [aHR 1.3 (1.03–1.24)], and the results did not differ by physical activity. The Kaplan–Meier curves for the risk of incident HTN according to CAC categories are shown in Fig. 1. The rate was higher for groups with higher CAC categories and the presence of CAC (P < 0.001), which did not differ by physical activity (Fig. 1). The 3D bar graph plotted in Fig. 2 shows that the incidence of HTN was increased by increasing CAC as a category and by baseline SBP. The combination of the highest quartile of CAC and baseline SBP predicted an incidence of HTN 7–8 times higher than that predicted by the lowest combination.

We also analyzed the HR of the incidence of HTN defined as ≥140/90 mmHg according to CAC category (Supplementary Table 1) and the presence/absence of CAC (Supplementary Table 2). The results were similar to the results for HTN defined as ≥130/80 mmHg after adjustments were made for all atherosclerotic predictors, including SBP and DBP, as shown in a previous paper [9].

We also analyzed ROC with a cut-off value. For the cut-off value of a CAC score of 16, the sensitivity was 55%, and the specificity was 53.9 with an AUC of 0.5516 (Supplementary Figure).

Discussion

In this study, we showed that CAC, a marker of atherosclerosis, is associated with incident HTN, with an aHR of 1.27 between the highest and lowest quartiles and of 1.3 between the presence and absence of CAC in a large asymptomatic middle-aged Asian population. These associations were consistent with the definition of HTN according to ACC/AHA guidelines (BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg) and ESC/EHS or JSH guidelines (BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg) after adjustments were made for all atherosclerotic predictors, including SBP and DBP, as shown in a previous paper [9]. We suggest that by the time of the diagnosis of HTN, atherosclerotic change in the blood vessels has already occurred, and the damage to the blood vessels may affect the increase in BP, which may eventually meet the criteria for the diagnosis of HTN.

Calcification can occur in both the intima and media of the arterial wall. Current consensus holds that coronary calcification represents primarily intimal calcification, whereas extracoronary calcification may be a combination of medial and intimal calcification. Vascular calcification, either intimal or medial, may directly increase arterial stiffness. Alternatively, arterial stiffness may contribute to the development of calcification and focal plaque [19].

The mechanism for a relationship between arterial stiffness and intimal calcification is that increased stiffness increases stress on the arterial wall, which makes it more prone to atherosclerosis and calcification.

An association between coronary calcification and arterial stiffness is supported by evidence that arterial stiffness (PWV) is associated with other measures of atheroma, such as intravascular ultrasound-detected coronary plaque volume [20]. Sawabe et al. [21] found that repeat PWV measures were correlated with the overall atherosclerotic burden at autopsy across eight sites of the large arteries in 304 Japanese elderly subjects.

Arterial stiffness is by no means synonymous with raised BP, but it is closely linked to raised BP. Arterial stiffness has long been known as a consequence of long-standing HTN. Aortic stiffness is associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes, independent of BP. The Prospective Studies Collaboration group reported in their renowned publications that the proportional difference in the risk of vascular death associated with a given absolute difference in usual BP is about the same, down to at least 115 mmHg usual SBP and 75 mmHg usual DBP, below which there is little evidence. At ages 40–69 years, each difference of 20 mmHg usual SBP (or, as an approximate equivalent, 10 mmHg usual DBP) is associated with more than a twofold difference in the stroke death rate and with a twofold difference in the death rates from IHD and from other vascular causes [22]. This study suggested that BP below the level of HTN, even at the level of normal BP, would be associated with vascular death and vascular damage.

CAC, a marker of atherosclerosis, may also identify subjects with abnormal BP (who either are below the threshold for a HTN diagnosis or have yet to receive a diagnosis) complicated by endothelial dysfunction, aortic stiffness [23, 24], and/or left ventricular hypertrophy [25], all of which are associated with a risk of HTN. Furthermore, CAC may reflect the cumulative exposure of the vasculature to BP, including abnormal diurnal BP patterns, and masked HTN, all of which increase susceptibility to the development of HTN but are not well captured using office-based BP measurements.

Therefore, does HTN cause vascular damage? Is the damage to blood vessels causing HTN? In other words, it is pointless to argue the “chicken or the egg” controversy. Although there may be differences depending on the individual, the usual BP may cause damage to the blood vessels, and any pressure may cause vascular damage. In our study results, the incidence of HTN increased according to not only CAC categories but also baseline SBP levels of initially normotensive subjects. The combination of CAC categories and baseline SBP level synergistically predicted the incidence of HTN (Fig. 2). The public health clinic requires a therapeutic approach to HTN according to the prescribed BP. At the individual level, however, the approach of pinpointing blood vessel damage and BP is a way to implement precision medicine.

There are several other potential explanations for the relationship between incident HTN and markers of atherosclerosis, CAC. Subjects with elevated CAC may carry a higher burden of risk factors associated with incident HTN. Shared risk factors between CAC and HTN may link both conditions [26]. However, in this study, even after accounting for various variables, the association between CAC and incident HTN persisted. A recent report found that men with high levels of physical activity had higher CAC scores than did men with lower levels of physical activity [27], and it is still unclear whether the higher CAC scores were associated with high levels of physical activity. We analyzed the data by accounting for physical activity status, but there was no significant effect on the results.

Study limitations

This study has several potential limitations. First, our study included relatively healthy young Asian male subjects, and our findings may differ for different age and sex groups. In addition, to generalize these results to other ethnic groups, further studies are needed. Second, we diagnosed HTN based on a single-visit BP measurement, which may lead to misclassification of BP status. However, well-trained nurses measured BP with a standard method three times and used the average of the second and third readings for our analysis, and we believe this procedure could increase reliability. Third, although we adjusted for various confounding factors (age, education, physical activity, current smoking, alcohol consumption (g/day), BMI, SBP, and DBP) that may affect incident HTN, there could be residual confounding factors, such as salt intake status, waist circumference, family history, and baseline arterial stiffness.

Conclusions

We found that CAC, a marker of atherosclerosis, is associated with incident HTN in a large asymptomatic middle-aged population. By the time of the diagnosis of HTN, atherosclerotic change in the blood vessels has already occurred, and the damage to the blood vessels may affect the increase in BP, which may eventually meet the criteria for the diagnosis of HTN.

References

Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2224–60.

Rapsomaniki E, Timmis A, George J, Pujades-Rodriguez M, Shah AD, Denaxas S, et al. Blood pressure and incidence of twelve cardiovascular diseases: lifetime risks, healthy life-years lost, and age-specific associations in 1.25 million people. Lancet. 2014;383:1899–911.

Shen L, Ma H, Xiang MX, Wang JA. Meta-analysis of cohort studies of baseline prehypertension and risk of coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112:266–71.

Gaziano TA, Bitton A, Anand S, Weinstein MC. The global cost of nonoptimal blood pressure. J Hypertens. 2009;27:1472–7.

Budoff MJ, Achenbach S, Blumenthal RS, Carr JJ, Goldin JG, Greenland P, et al. Assessment of coronary artery disease by cardiac computed tomography: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Committee on Cardiovascular Imaging and Intervention, Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention, and Committee on Cardiac Imaging, Council on Clinical Cardiology. Circulation. 2006;114:1761–91.

Carr JJ, Jacobs DR Jr., Terry JG, Shay CM, Sidney S, Liu K, et al. Association of coronary artery calcium in adults aged 32 to 46 years with incident coronary heart disease and death. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:391–9.

Sangiorgi G, Rumberger JA, Severson A, Edwards WD, Gregoire J, Fitzpatrick LA, et al. Arterial calcification and not lumen stenosis is highly correlated with atherosclerotic plaque burden in humans: a histologic study of 723 coronary artery segments using nondecalcifying methodology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:126–33.

Budoff MJ, Diamond GA, Raggi P, Arad Y, Guerci AD, Callister TQ, et al. Continuous probabilistic prediction of angiographically significant coronary artery disease using electron beam tomography. Circulation. 2002;105:1791–6.

Grossman C, Shemesh J, Dovrish Z, Morag NK, Segev S, Grossman E. Coronary artery calcification is associated with the development of hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2013;26:13–9.

Aladin AI, Al Rifai M, Rasool SH, Dardari Z, Yeboah J, Nasir K, et al. Relation of coronary artery calcium and extra-coronary aortic calcium to incident hypertension (from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis). Am J Cardiol. 2018;121:210–6.

Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:e127–248.

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. Jama. 2003;289:2560–72.

Vaduganathan M, Pareek M, Qamar A, Pandey A, Olsen MH, Bhatt DL. Baseline blood pressure, the 2017 ACC/AHA high blood pressure guidelines, and long-term cardiovascular risk in SPRINT. Am J Med. 2018;131:956–60.

Lee JY, Ryu S, Cheong E, Sung KC. Association of physical activity and inflammation with all-cause, cardiovascular-related, and cancer-related mortality. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:1706–16.

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1381–95.

Oh JY, Yang YJ, Kim BS, Kang JH. Validity and reliability of Korean version of International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) short form. J Korean Acad Fam Med. 2007;28:532–41.

Budoff MJ, Nasir K, McClelland RL, Detrano R, Wong N, Blumenthal RS, et al. Coronary calcium predicts events better with absolute calcium scores than age-sex-race/ethnicity percentiles: MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:345–52.

Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, Zusmer NR, Viamonte M Jr., Detrano R. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:827–32.

Mackey RH, Venkitachalam L, Sutton-Tyrrell K. Calcifications, arterial stiffness and atherosclerosis. In: Safar ME, Frohlich ED, editors. Atherosclerosis, large arteries and cardiovascular risk. Basel: Karger; 2007. pp. 234–44.

McLeod AL, Uren NG, Wilkinson IB, Webb DJ, Maxwell SR, Northridge DB, et al. Non-invasive measures of pulse wave velocity correlate with coronary arterial plaque load in humans. J Hypertens. 2004;22:363–8.

Sawabe M, Takahashi R, Matsushita S, Ozawa T, Arai T, Hamamatsu A, et al. Aortic pulse wave velocity and the degree of atherosclerosis in the elderly: a pathological study based on 304 autopsy cases. Atherosclerosis. 2005;179:345–51.

Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:1903–13.

Tikhonoff V, Casiglia E. Measuring regional arterial stiffness in patients with peripheral artery disease: innovative technology. Hypertens Res. 2013;36:191–3.

Al-Mallah MH, Nasir K, Katz R, Takasu J, Lima JA, Bluemke DA, et al. Thoracic aortic distensibility and thoracic aortic calcium (from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis [MESA]). Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:575–80.

Post WS, Larson MG, Levy D. Impact of left ventricular structure on the incidence of hypertension. The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1994;90:179–85.

Mahoney LT, Burns TL, Stanford W, Thompson BH, Witt JD, Rost CA, et al. Coronary risk factors measured in childhood and young adult life are associated with coronary artery calcification in young adults: the Muscatine Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:277–84.

DeFina LF, Radford NB, Barlow CE, Willis BL, Leonard D, Haskell WL, et al. Association of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality with high levels of physical Activity and concurrent coronary artery calcification. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4:174–81.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the efforts of the health screening group at Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, Korea.

Funding

Funded by author’s own resources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KS contributed to the hypothesis, wrote the methods and contributed to the discussion. ML analyzed the data. JK contributed to the discussion. JP contributed to the discussion. EC contributed to the discussion. AA contributed to the discussion and introduction. KS is the guarantor for the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sung, KC., Lee, MY., Kim, JY. et al. Prediction of incident hypertension with the coronary artery calcium score based on the 2017 ACC/AHA high blood pressure guidelines. Hypertens Res 43, 1293–1300 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-0526-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-0526-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Updates on CAD risk assessment: using the coronary artery calcium score in combination with traditional risk factors

The Egyptian Heart Journal (2025)