Abstract

There is a lack of data on how nighttime blood pressure (BP) might modify the relationship between sleep duration and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk. Self-reported sleep duration data were available for 2253/2562 patients from the J-HOP Nocturnal BP study; of these, 2236 had complete follow-up data (mean age 63.0 years, 83% using antihypertensive drugs). CVD outcomes included stroke, coronary artery disease (CAD), and atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD [stroke + CAD]). Associations between sleep duration and nighttime home BP (measured using a validated, automatic, oscillometric device) were determined. During a mean follow-up of 7.1 ± 3.8 years, there were 133 ASCVD events (52 strokes and 81 CAD events). Short sleep duration (<6 versus ≥6 and <9 h/night) was significantly associated with the risk of ASCVD (hazard ratio [HR] 1.85, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.07–3.22), especially stroke (HR 2.47, 95% CI 1.08–5.63). When nighttime systolic BP was <120 mmHg, those with a sleep duration <6 versus ≥6 and <9 h/night had a significantly higher risk of ASCVD and CAD events (HR [95% CI] 3.46 [1.52–7.92] and 3.24 [1.21–8.69], respectively). Even patients with “optimal” sleep duration (≥6 and <9 h/night) were at significantly higher risk of stroke when nighttime systolic BP was uncontrolled (HR [95% CI] 2.76 [1.26–6.04]). Adding sleep duration and nighttime BP to a base model with standard CVD risk factors significantly improved model performance for stroke (C-statistic 0.795, 95% CI 0.737–0.856; p = 0.038). These findings highlight the importance of both optimal sleep duration and control of nocturnal hypertension for reducing the risk of CVD, especially stroke. Clinical Trial registration: URL: http://www.umin.ac.jp/icdr/index.html. Unique identifier: UMIN000000894.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As many as 35% of adults have a self-reported sleep duration below the recommended optimum of 7 h/night [1], and data from the Sleep Heart Health Study suggest that objective sleep duration is <6 h/night in ~50% of the population [2]. Optimal sleep duration is critical for cardiovascular health because both long and short sleep durations are associated with adverse health outcomes, as described in the 2016 American Heart Association (AHA) Scientific Statement on sleep duration and cardiovascular risk [3]. This statement is based on a large body of evidence showing U-shaped relationships between the duration of sleep and the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) [4,5,6,7,8] and, to a lesser extent, all-cause death [5, 9,10,11,12].

Sleep duration has also been reported to be a risk factor for the development of hypertension [13, 14]. Hypertension, especially nocturnal hypertension, represents an important risk factor for the development of CVD and the occurrence of CVD events [15,16,17,18]. In addition to nocturnal hypertension, abnormalities in the natural circadian variation of blood pressure (BP) also increase cardiovascular risk [19, 20]. Both insufficient and excessive sleep have been associated with attenuated nighttime BP dipping [21], which is a prognostic marker for CVD [22, 23]. Thus, there is the potential that the combination of nocturnal hypertension with an abnormal dipping pattern and nonoptimal sleep duration could have additive, or even synergistic, negative effects on cardiovascular risk. However, there is a lack of data on the interplay between sleep duration and nighttime BP with respect to the risk of different forms of CVD and associated mortality.

This analysis used data from the nationwide practice-based Japan Morning Surge-Home Blood Pressure (J-HOP) study to investigate associations between self-reported sleep duration and incident CVD in the context of nighttime home BP values.

Methods

Study design

The prospective J-HOP study was conducted between January 2005 and May 2012 at 71 institutions throughout Japan. The study protocol was approved by the internal review board at the Jichi Medical University School of Medicine, Tochigi, Japan. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients enrolled in the study.

Study population

Participants in J-HOP were ambulatory outpatients who had at least one of the following cardiovascular risk factors: hypertension; hyperlipidemia; diabetes (defined as fasting blood sugar ≥ 126 mg/dL or treatment with antidiabetic agents); glucose intolerance; metabolic syndrome; chronic kidney disease (defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2); history of CVD (including coronary artery disease [CAD], stroke, aortic dissection, peripheral artery disease, congestive heart failure); atrial fibrillation; current smoking; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; and/or sleep apnea syndrome. For the present study, recruitment was based on J-HOP study participants who had nighttime home BP measured at baseline. Further details of the J-HOP Nocturnal BP study protocol and procedures have been published [16].

Outcomes

CVD outcomes included stroke (fatal or nonfatal; defined as the sudden onset of neurological deficit confirmed on brain computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging that persisted for ≥24 h in the absence of any other disease that might explain the symptoms [excluding transient ischemic attack]) and CAD (fatal or nonfatal; defined as acute myocardial infarction, angina pectoris requiring percutaneous coronary intervention, and sudden death within 24 h of the abrupt onset of symptoms). The term atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD) was used to describe the combination of both stroke and CAD events.

Data on CVD outcomes were obtained from a general physician at each study center. Incident stroke and CAD outcomes were also ascertained by regular (annual or more frequent) review of participants’ medical records. When patients did not come to the hospital, they or their family members were interviewed by telephone.

All endpoint events were adjudicated by an endpoint committee that was unaware of individual clinical characteristics, including home BP data.

Assessments

Home BP measurements were performed using a validated cuff oscillometric device (HEM-5001; Medinote; Omron Healthcare, Co., Ltd, Kyoto, Japan) in accordance with hypertension guidelines that were current at the time assessments were performed [24,25,26]. The device automatically takes three separate measurements of BP at 15-s intervals for each assessment. At bedtime, the device can be set to measure BP during sleep, and all recorded BP parameters are stored in the device memory, with identification of measurements as morning, evening or during sleep.

Home BP values were recorded over a period of 14 days. Subjects were asked to measure morning home BP after awakening and prior to breakfast and taking antihypertensive medication and evening BP before taking antihypertensive medication and going to bed, BP measurements were taken after the participant remained in a sitting position for 2 min. Readings from the first day were excluded, and the average of all home BP measurements (three each morning and three each evening) was calculated. Nighttime home BP was recorded on at least one night in the 14-day measurement period at three different preset times (2 a.m., 3 a.m., and 4 a.m.), and nighttime home BP was calculated as the average of all sleep BP values measured. Patients were divided into two groups based on nighttime home systolic BP (SBP): <120 and ≥120 mmHg [15, 27]. All BP data from the home BP monitoring (HBPM) device were downloaded to a computer and transferred to the study control center for analysis by investigators who were unaware of the clinical characteristics of the study participants.

Self-reported sleep data were obtained from a questionnaire completed by the patient at baseline (Table I in the Online Data Supplement). Patients were divided into subgroups based on sleep duration: <6 h/night, ≥6 and <9 h/night, and ≥9 h/night [28].

Statistical analysis

Between-group differences were evaluated using one-way analysis of variance for mean values and the chi-square test for frequencies. The cumulative incidence of CVD events in sleep duration subgroups was visualized using Kaplan–Meier curves adjusted for covariates (age, sex, body mass index, current smoking, history of diabetes, statin use, aspirin use, antihypertensive medication use, history of CVD, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and office SBP). Associations between sleep duration, nighttime home BP values (nighttime SBP < 120 or ≥120 mmHg), and the risk of ASCVD, stroke, and CAD were assessed using Cox proportional hazards models (hazard ratio [HR] and 95% confidence intervals [CIs] were calculated).

The proportionality assumption for the Cox model was confirmed graphically, and comparison of the discriminative ability of the model was performed using Harrell’s C-statistics (with 95% CI calculated by bootstrapping) [29]. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Two-sided p values < 0.05 were defined as statistically significant.

Results

Study population

Of the 2562 patients included in the J-HOP Nocturnal BP study, 2253 patients completed the sleep questionnaire, and 2236 of these participants had complete follow-up data (Fig. I in the Online Data Supplement). Just over half of all patients were male, the mean age was 63.0 ± 10.3 years, and 83% of participants were taking antihypertensive medication. The proportions of individuals with sleep durations <6 h/night, ≥6 and <9 h/night, and ≥9 h/night were 8%, 84%, and 8%, respectively (Table 1). Follow-up data were collected over a mean of 7.1 ± 3.8 years (15,896 person-years), during which time there were 133 ASCVD events, including 52 strokes and 81 CAD events.

ASCVD events and sleep duration

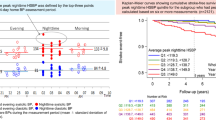

Kaplan–Meier curves demonstrated that compared with sleep duration ≥ 6 and <9 h/night, sleep duration < 6 h/night was associated with a significantly increased risk of total ASCVD (p = 0.029) and stroke (p = 0.031) but not CAD (Fig. 1). Short sleep duration (<6 h/night) was a significant independent predictor of an increased risk of ASCVD and stroke events compared with a sleep duration of ≥6 and <9 h in the Cox model (Fig. 2).

Kaplan–Meier curves showing the relationship between the number of hours of sleep and the risk of cardiovascular events (adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, current smoking, history of diabetes, statin use, aspirin use, antihypertensive medication use, history of cardiovascular disease, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and office systolic blood pressure). ASCVD atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, CAD coronary artery disease

Hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) values for the risk of cardiovascular events based on the number of hours of sleep (adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, current smoking, history of diabetes, statin use, aspirin use, antihypertensive medication use, history of cardiovascular disease, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and office systolic blood pressure). ASCVD atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, CAD coronary artery disease

Impact of nighttime SBP

Compared to the reference (sleep duration of ≥6 and <9 h/night plus nighttime SBP < 120 mmHg), sleep duration of <6 h/night was associated with an increased risk of stroke irrespective of nighttime SBP status (HR [95% CI] for stroke was 4.65 [0.98–21.98] when nighttime SBP was <120 mmHg [p = 0.052] and 4.80 [1.57–14.65] when nighttime SBP was ≥120 mmHg [p = 0.006]) (Table 2). A sleep duration of <6 h/night was also associated with a risk of ASCVD and CAD when nighttime SBP was <120 mmHg (Table 2). There was a trend toward an increased risk of stroke in patients who slept for ≥9 h/night and had nighttime BP ≥ 120 mmHg (HR [95% CI] 3.01 [0.98–9.30]; p = 0.055) (Table 2). Even patients who slept for the “optimal” duration of ≥6 and <9 h/night were at significantly higher risk of experiencing stroke when nighttime SBP was ≥120 mmHg (HR [95% CI] 2.76 [1.26–6.04]; p = 0.011) (Table 2).

Model performance

The base model yielded a C-statistic value of 0.757 (95% CI 0.719–0.794) for ASCVD, 0.763 (95% CI 0.718–0.825) for stroke, and 0.788 (95% CI 0.731–0.847) for CAD (Table 3). The addition of sleep duration and nighttime SBP level (<120 or ≥120 mmHg) to the base model significantly increased the C-statistic value for stroke (0.795, 95% CI 0.737–0.856; p = 0.038) but not for CAD or total ASCVD (Table 3).

Discussion

The results of this clinical practice-based, prospective study showed that short sleep duration (<6 h/night) was an independent risk factor for ASCVD events, especially stroke. In addition, for the first time, we found that the risk of stroke was independently associated with shorter sleep duration irrespective of whether nighttime BP was <120 or ≥120 mmHg. In contrast, short sleepers were at increased risk of overall ASCVD and CAD events only when nighttime SBP was <120 mmHg. For patients with optimal (≥6 and <9 h/night) or long (≥9 h/night) sleep duration, the risk of stroke was only increased significantly when nighttime SBP was ≥120 mmHg.

Our findings of a significant association between sleep duration and cardiovascular risk are consistent with the published literature. The majority of current literature in this field shows a U-shaped relationship between sleep duration and CVD risk, with those who sleep for short (<6 h) or long (≥9 h) periods each night having a significantly increased risk of developing CVD or experiencing a CVD event [4,5,6,7,8, 28, 30,31,32,33,34]. For example, data from a prospective cross-sectional study of 30,397 participants in the National Health Interview Survey 2005 showed that sleep durations of ≤5, ≤6, 8, and ≥9 h/night were significantly associated with the occurrence of CVD events (odds ratio [95% CI] values of 2.20 [1.78–2.71], 1.33 [1.13–1.57], 1.23 [1.04–1.41], and 1.57 [1.31–1.89], respectively, for the comparison with sleep duration of 7 h/night), independent of potential confounders (including age, sex, race/ethnicity, smoking, alcohol intake, body mass index, physical activity, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and depression) [28].

This analysis of J-HOP data evaluated the role of nighttime BP as a contributor to or modifier of the relationship between sleep duration and CVD for the first time. Using the J-HOP study database, nocturnal hypertension (detected using ambulatory BP monitoring or HBPM) has previously been shown to be significantly associated with both overall CVD and stroke [35]. New data from the current analysis highlighted that the association between short sleep duration and increased cardiovascular risk was seen regardless of nighttime SBP level. Thus, even patients with nighttime SBP < 120 mmHg had a significantly increased risk of CVD when sleep duration was suboptimal. This suggests that short sleep duration may be a stronger risk factor for ASCVD than nighttime BP. In contrast, the increased cardiovascular risk found in longer sleepers mostly disappeared after controlling for nighttime BP and other covariates in this analysis, with the exception of stroke in patients with SBP ≥ 120 mmHg.

Overall, stroke was the event most closely associated with sleep duration in our study after controlling for covariates and when nighttime BP was <120 mmHg. This finding highlights the importance of sleep duration with respect to stroke risk even in the presence of normal nighttime BP and adds to current knowledge in this area. A meta-analysis of data specifically relating to sleep duration and stroke reported an increased risk of prevalent stroke when sleep duration was short (OR 1.71, 95% CI 1.39–2.02) or long (OR 2.12, 95% CI 1.51–2.73) [36]. In individuals who responded to the National Health Interview Surveys (n = 154,599; 2006–2011), age-standardized prevalence rates for stroke were 2.8, 2.0, and 5.2% in those with a self-reported sleep duration of ≤6, 7–8, and ≥9 h/night, respectively [37]. Other large population studies have also highlighted a U-shaped relationship between sleep duration and stroke [5, 38]. Although the relationship between sleep duration and stroke is modified by a number of covariates [37, 39], ours is the first study to evaluate the contribution of nighttime BP to the risk of stroke and CAD as it relates to sleep duration.

There are a number of plausible biological mechanisms that might link short sleep duration with an increased risk of CVD. These mechanisms have been reviewed in detail elsewhere but include increased sympathetic nervous system activity, heart rate and BP; vasoconstriction; and salt retention [36, 40]. Of particular relevance to the current analysis are data from sleep deprivation studies that show increased nighttime BP and attenuated nighttime BP dipping, along with an amplified morning BP surge [41, 42], probably due to enhanced cardiac sympathetic drive [43, 44]. Lack of sleep has also been shown to have negative effects on vascular structure and function, with increased arterial stiffness documented after only one night of sleep deprivation [45]. Impaired endothelial function is a marker of poor vascular health and is likely to be a precursor of atherosclerosis [46]. This idea is supported by data from a prospective cohort study showing that individuals with an objective sleep duration of <6 h/night had a greater burden of preclinical atherosclerosis than those sleeping for 7–8 h/night (OR 1.27, 95% CI 1.06–1.52; p = 0.008) [47]. Similarly, a large general population study showed that carotid intima-media thickness values were lowest in subjects who got 7–8 h of sleep per night [48].

In contrast, the mechanisms underlying the association between long sleep duration and cardiovascular risk are less clear. Nevertheless, a recent study provides a potential rationale for the U-shaped relationship between sleep duration and CVD [49]. Cash et al. investigated the link between sleep duration and what they defined as “cardiovascular health,” which was based on the AHA’s ideal cardiovascular health metrics, where seven modifiable health behaviors were scored as ideal (2 points), intermediate (1 point), or poor (0 points) [49]. This cross-sectional evaluation based on NHANES data found that sleep duration of <6 and ≥9 h was associated with a decreased likelihood of ideal cardiovascular health and a significant decrease in the mean cardiovascular health score after adjustment for demographic, clinical, and social factors. Any deviation from “ideal” cardiovascular health would likely contribute to future development of CVD, although more research is needed to fully understand the implications of sleep duration in relation to CVD, including better characterization of any causal relationships.

Based on our study findings, it would appear that the impact of short sleep duration on the cardiovascular system, by whatever mechanism or mechanisms, usually overpowers the negative impact of nocturnal hypertension, especially with respect to ASCVD risk. However, there may be greater interplay between long sleep duration and nighttime BP. Nighttime BP could also be considered a hemodynamic measure of sleep quality, but this requires more research before definitive conclusions can be drawn.

Thus, in addition to nocturnal hypertension, unhealthy sleep duration represents a modifiable cardiovascular risk factor that could be amenable to population-level interventions. However, the impact of such interventions needs to be evaluated in randomized, controlled clinical trials because it is currently unclear whether improving the duration and quality of sleep will help prevent the development and/or progression of CVD. The lack of data in this area is reflected in the current ACC/AHA guidelines for the primary prevention of CVD, which do not include any recommendations about sleep duration [50].

Strengths and limitations

This analysis is the first to evaluate the interaction between sleep duration and nighttime BP as risk factors for CVD. The study included a large population of community-based adults, and nighttime home BP was determined using the latest automated technology. However, several limitations need to be taken into account when interpreting the findings. First, sleep duration was evaluated only at the start of the study and was based on patient self-report rather than objective measures such as actigraphy. Home BP was also only determined over a single 14-day period at the beginning of the study. Therefore, the impact of changes in home BP or sleep duration over time on the study findings is unknown. The majority of patients in the study (>80%) were taking antihypertensive medication, and no comparisons were made between treated and untreated patients. Therefore, the effects of antihypertensive therapy on the relationships identified in this study cannot be determined. Finally, the longitudinal study design provides data on associations between sleep duration and/or nighttime BP and CVD events but does not allow causation to be attributed.

Conclusions

These findings showed some modulation of the effect of sleep duration on CVD risk by nighttime home BP. This finding highlights the importance of considering both sleep duration and nighttime BP in cardiovascular risk assessments and suggests that sleep hygiene is an important consideration when designing and implementing CVD prevention strategies in patients with hypertension. Future studies will help to determine whether improving the duration and quality of sleep will help prevent the development and/or progression of CVD. The current study shows that this research also needs to include an evaluation of nocturnal BP to provide a more comprehensive picture of CVD risk.

References

Liu Y, Wheaton AG, Chapman DP, Cunningham TJ, Lu H, Croft JB. Prevalence of healthy sleep duration among adults—United States, 2014. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:137–41.

Silva GE, Goodwin JL, Sherrill DL, Arnold JL, Bootzin RR, Smith T, et al. Relationship between reported and measured sleep times: the Sleep Heart Health Study (SHHS). J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:622–30.

St-Onge MP, Grandner MA, Brown D, Conroy MB, Jean-Louis G, Coons M, et al. Sleep duration and quality: impact on lifestyle behaviors and cardiometabolic health: a scientific statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134:e367–86.

Kwok CS, Kontopantelis E, Kuligowski G, Gray M, Muhyaldeen A, Gale CP, et al. Self-reported sleep duration and quality and cardiovascular disease and mortality: a dose-response meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e008552.

Cappuccio FP, Cooper D, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep duration predicts cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1484–92.

Itani O, Jike M, Watanabe N, Kaneita Y. Short sleep duration and health outcomes: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Sleep Med. 2017;32:246–56.

Jike M, Itani O, Watanabe N, Buysse DJ, Kaneita Y. Long sleep duration and health outcomes: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;39:25–36.

Krittanawong C, Tunhasiriwet A, Wang Z, Zhang H, Farrell AM, Chirapongsathorn S, Sun T, Kitai T, Argulian E. Association between short and long sleep durations and cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2019;8:762–70.

Cappuccio FP, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep. 2010;33:585–92.

Gallicchio L, Kalesan B. Sleep duration and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sleep Res. 2009;18:148–58.

Kim JH, Hayek SS, Ko Y-A, Liu C, Samman Tahhan A, Ali S, et al. Sleep duration and mortality in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2019;123:874–81.

Kurina LM, McClintock MK, Chen JH, Waite LJ, Thisted RA, Lauderdale DS. Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: a critical review of measurement and associations. Ann Epidemiol. 2013;23:361–70.

Gangwisch JE, Heymsfield SB, Boden-Albala B, Buijs RM, Kreier F, Pickering TG, et al. Short sleep duration as a risk factor for hypertension. Hypertension. 2006;47:833–9.

Gottlieb DJ, Redline S, Nieto FJ, Baldwin CM, Newman AB, Resnick HE, et al. Association of usual sleep duration with hypertension: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Sleep. 2006;29:1009–14.

Fujiwara T, Hoshide S, Kanegae H, Kario K. Cardiovascular event risks associated with masked nocturnal hypertension defined by home blood pressure monitoring in the J-HOP Nocturnal Blood Pressure Study. Hypertension. 2020;76:259–66.

Kario K, Kanegae H, Tomitani N, Okawara Y, Fujiwara T, Yano Y, et al. Nighttime blood pressure measured by home blood pressure monitoring as an independent predictor of cardiovascular events in general practice. Hypertension. 2019;73:1240–8.

Kikuya M, Ohkubo T, Asayama K, Metoki H, Obara T, Saito S, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure and 10-year risk of cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality: the Ohasama study. Hypertension. 2005;45:240–5.

Mokwatsi GG, Hoshide S, Kanegae H, Fujiwara T, Negishi K, Schutte AE, Kario K, et al. Direct comparison of home versus ambulatory defined nocturnal hypertension for predicting cardiovascular events: the Japan Morning Surge-Home Blood Pressure (J-HOP) Study. Hypertension. 2020;76:554–61.

de la Sierra A, Redon J, Banegas JR, Segura J, Parati G, Gorostidi M, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with circadian blood pressure patterns in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2009;53:466–72.

Kario K, Pickering TG, Hoshide S, Eguchi K, Ishikawa J, Morinari M, et al. Morning blood pressure surge and hypertensive cerebrovascular disease: role of the alpha adrenergic sympathetic nervous system. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:668–75.

Friedman O, Shukla Y, Logan AG. Relationship between self-reported sleep duration and changes in circadian blood pressure. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22:1205–11.

Gavriilaki M, Anyfanti P, Nikolaidou B, Lazaridis A, Gavriilaki E, Douma S, et al. Nighttime dipping status and risk of cardiovascular events in patients with untreated hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Hypertens. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.14039.

Kario K, Hoshide S, Mizuno H, Kabutoya T, Nishizawa M, Yoshida T, et al. Nighttime blood pressure phenotype and cardiovascular prognosis: practitioner-based nationwide JAMP Study. Circulation. 2020;142:1810–20.

Pickering TG, Miller NH, Ogedegbe G, Krakoff LR, Artinian NT, Goff D. Call to action on use and reimbursement for home blood pressure monitoring: a joint scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American Society Of Hypertension, and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. Hypertension. 2008;52:10–29.

Parati G, Stergiou GS, Asmar R, Bilo G, de Leeuw P, Imai Y, et al. European Society of Hypertension guidelines for blood pressure monitoring at home: a summary report of the Second International Consensus Conference on Home Blood Pressure Monitoring. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1505–26.

Imai Y, Kario K, Shimada K, Kawano Y, Hasebe N, Matsuura H. Japanese Society of Hypertension Committee for Guidelines for Self-monitoring of Blood Pressure at Home et al. The Japanese Society of Hypertension guidelines for self-monitoring of blood pressure at home (second edition). Hypertens Res. 2012;35:777–95.

Asayama K, Fujiwara T, Hoshide S, Ohkubo T, Kario K, Stergiou GS, et al. Nocturnal blood pressure measured by home devices: evidence and perspective for clinical application. J Hypertens. 2019;37:905–16.

Sabanayagam C, Shankar A. Sleep duration and cardiovascular disease: results from the National Health Interview Survey. Sleep. 2010;33:1037–42.

Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB. Overall C as a measure of discrimination in survival analysis: model specific population value and confidence interval estimation. Stat Med. 2004;23:2109–23.

Kim YS, Davis S, Stok WJ, van Ittersum FJ, van Lieshout JJ. Impaired nocturnal blood pressure dipping in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Hypertens Res. 2019;42:59–66.

Ikehara S, Iso H, Date C, Kikuchi S, Watanabe Y, Wada Y, et al. Association of sleep duration with mortality from cardiovascular disease and other causes for Japanese men and women: the JACC study. Sleep. 2009;32:295–301.

Im E, Kim GS. Relationship between sleep duration and Framingham cardiovascular risk score and prevalence of cardiovascular disease in Koreans. Medicine. 2017;96:e7744.

Liu J, Yuen J, Kang S. Sleep duration, C-reactive protein and risk of incident coronary heart disease−results from the Framingham Offspring Study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;24:600–5.

Krittanawong C, Kumar A, Wang Z, Jneid H, Baber U, Mehran R, et al. Sleep duration and cardiovascular health in a representative community population (from NHANES, 2005 to 2016). Am J Cardiol. 2020;127:149–55.

Hoshide S, Yano Y, Haimoto H, Yamagiwa K, Uchiba K, Nagasaka S, et al. Morning and evening home blood pressure and risks of incident stroke and coronary artery disease in the Japanese general practice population: the Japan Morning Surge-Home Blood Pressure Study. Hypertension. 2016;68:54–61.

Covassin N, Singh P. Sleep duration and cardiovascular disease risk: epidemiologic and experimental evidence. Sleep Med Clin. 2016;11:81–9.

Fang J, Wheaton AG, Ayala C. Sleep duration and history of stroke among adults from the USA. J Sleep Res. 2014;23:531–7.

Liu Y, Wheaton AG, Chapman DP, Croft JB. Sleep duration and chronic diseases among U.S. adults age 45 years and older: evidence from the 2010 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Sleep. 2013;36:1421–7.

Ruiter Petrov ME, Letter AJ, Howard VJ, Kleindorfer D. Self-reported sleep duration in relation to incident stroke symptoms: nuances by body mass and race from the REGARDS study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23:e123–32.

Nagai M, Hoshide S, Kario K. Sleep duration as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease- a review of the recent literature. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2010;6:54–61.

Covassin N, Bukartyk J, Sahakyan K, Svatikova A, Calvin A, St Louis EK, et al. Experimental sleep restriction increases nocturnal blood pressure and attenuates blood pressure dipping in healthy individuals. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:A1352.

Yang H, Haack M, Lamanna M, Mullington J. Blunted nocturnal blood pressure dipping and exaggerated morning blood pressure surge in response to a novel repetitive sleep restriction challenge. FASEB J. 2015;29:957–8.

Dettoni JL, Consolim-Colombo FM, Drager LF, Rubira MC, Souza SB, Irigoyen MC, et al. Cardiovascular effects of partial sleep deprivation in healthy volunteers. J Appl Physiol. 2012;113:232–6.

Zhong X, Hilton HJ, Gates GJ, Jelic S, Stern Y, Bartels MN, et al. Increased sympathetic and decreased parasympathetic cardiovascular modulation in normal humans with acute sleep deprivation. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:2024–32.

Sunbul M, Kanar BG, Durmus E, Kivrak T, Sari I. Acute sleep deprivation is associated with increased arterial stiffness in healthy young adults. Sleep Breath. 2014;18:215–20.

Verma S, Buchanan MR, Anderson TJ. Endothelial function testing as a biomarker of vascular disease. Circulation. 2003;108:2054–9.

Domínguez F, Fuster V, Fernández-Alvira JM, Fernández-Friera L, López-Melgar B, Blanco-Rojo R, et al. Association of sleep duration and quality with subclinical atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:134–44.

Wolff B, Völzke H, Schwahn C, Robinson D, Kessler C, John U. Relation of self-reported sleep duration with carotid intima-media thickness in a general population sample. Atherosclerosis. 2008;196:727–32.

Cash RE, Hery CMB, Panchal AR, Bower JK. Association between sleep duration and ideal cardiovascular health among US adults, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2013-2016. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17:190424.

Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140:e563–95.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing support was provided by Nicola Ryan, an independent medical writer, and Ayako Okura, funded by Jichi Medical University.

Funding

This study was financially supported in part by a grant from the 21st Century Center of Excellence Project run by Japan’s Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (to KK); a grant from the Foundation for Development of the Community (Tochigi, Japan); a grant from Omron Healthcare Co., Ltd.; a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (21390247) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan, 2009 to 2013; and funds from the MEXT-Supported Program for the Strategic Research Foundation at Private Universities, 2011 to 2015 Cooperative Basic and Clinical Research on Circadian Medicine (S1101022). The funding sponsors had no role in designing or conducting this study; in the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; in the preparation of the article; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K. Kario is the principal investigator of the J-HOP study, supervised its conduct and data analysis, and had primary responsibility for the writing of this paper. S. Hoshide and M. Nagai reviewed/edited the manuscript. H. Kanegae advised on the data analysis under the guidance of K. Kario. K. Kario and S. Hoshide collected the data. Y. Okawara conducted data analysis. All authors have read and given final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

KK has received research grants from Omron Healthcare and A&D Co. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kario, K., Hoshide, S., Nagai, M. et al. Sleep and cardiovascular outcomes in relation to nocturnal hypertension: the J-HOP Nocturnal Blood Pressure Study. Hypertens Res 44, 1589–1596 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00709-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00709-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Isolated nocturnal hypertension and its association with sleep duration and quality

Journal of Human Hypertension (2025)

-

Inadequate sleep increases stroke risk: evidence from a comprehensive meta-analysis of incidence and mortality

GeroScience (2025)

-

Prestroke sleep and stroke: a narrative review

Sleep and Breathing (2025)

-

Time in therapeutic range for out-of-office blood pressure in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: A better risk assessment measurement

Hypertension Research (2024)

-

Development of beat-by-beat blood pressure monitoring device and nocturnal sec-surge detection algorithm

Hypertension Research (2024)