Abstract

This study investigated inter-arm systolic blood pressure difference (IASBPD) and mortality risks in 8628 Chinese community residents from an atherosclerosis cohort. IASBPD was calculated by subtracting the systolic blood pressure of the left arm from that of the right arm. Participants were categorized as |IASBPD| <10 mmHg or ≥10 mmHg. These groups were further subdivided into four categories according to specific IASBPD values. The endpoints included all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality. Over a median follow-up of 9.87 years, a total of 442 all-cause and 138 cardiovascular deaths were recorded. Compared to |IASBPD| <10 mmHg group, the |IASBPD| ≥10 mmHg group had a 53% increase in all-cause mortality risk (adjusted HR = 1.53, P = 0.002) and a 71% increase in cardiovascular mortality risk (adjusted HR = 1.71, P = 0.021). When comparing specific IASBPD, no significant increase in all-cause mortality risk was observed in the group with a right arm higher ≥10 mmHg (adjusted HR = 1.17, P = 0.507) or in the group with a left arm higher ≤10 mmHg (adjusted HR = 0.90, P = 0.329). Conversely, the left arm higher >10 mmHg group demonstrated a significant 59% increase in the risk of all-cause mortality (adjusted HR = 1.59, P = 0.013). While the association with cardiovascular mortality was not statistically significant in this subgroup, the trend paralleled that observed for all-cause mortality. In conclusion, an elevated IASBPD is significantly associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality risks, with higher IASBPD in the left arm showing a stronger link to all-cause mortality risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypertension constitutes a global public health burden across both developing and developed nations [1], demonstrating strong associations with diverse cardiovascular sequelae [2].Guidelines recommend the simultaneous measurement of blood pressure in both upper limbs during the initial assessment to accurately determine which arm exhibits higher blood pressure and to evaluate the inter-arm systolic blood pressure difference (IASBPD) [3]. Technological advancements in oscillometric devices have enhanced the precision and practicality of IASBPD assessment [4], transforming this metric into an emerging prognostic tool - while its diagnostic utility in peripheral artery disease screening is well-established, growing evidence supports its prognostic value for cardiovascular events and mortality risk stratification [5].

Despite over a century of scientific recognition, clinical underrecognition persists: only 13% of practitioners routinely implement bilateral measurements [6]. Contemporary research identifies IASBPD as a composite biomarker reflecting multiple cardiovascular risk determinants, including age [7], gender [8], smoking [9], alcohol consumption [9], hyperlipidemia [7, 10], and diabetes mellitus [11]. Although numerous epidemiological studies demonstrate IASBPD-mortality associations across heterogeneous populations [12,13,14,15,16], substantial controversy persists regarding its independent prognostic value, with conflicting reports from recent investigations [17,18,19,20]. Notably, no prospective cohort study has systematically examined the laterality-specific prognostic implications of IASBPD - a critical knowledge gap our study seeks to address.

The investigation of laterality-specific associations between IASBPD and mortality risk is grounded in distinct hemodynamic pathways. Anatomically, the left subclavian artery’s direct origin from the aortic arch renders left-arm blood pressure measurements more sensitive to proximal aortic pathology, such as atherosclerotic plaque burden or hemodynamically significant stenosis [21]. These central arterial abnormalities are established precursors of systemic vascular dysfunction. Conversely, right-arm pressure, obtained distal to the brachiocephalic trunk, may primarily reflect localized vascular changes with limited prognostic relevance.

Based on this anatomical paradigm, We hypothesized that left-arm IASBPD higher (≥10 mmHg) will demonstrate stronger associations with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality than right-arm. Therefore, the current community-based cohort study aimed to: (1) quantify mortality risk associated with directional IASBPD in a Chinese population; (2) determine whether left-arm systolic dominance confers incremental prognostic value compared to right-arm differences.

Methods

Study population

Participants were recruited from an atherosclerosis cohort survey conducted in the Gucheng and Pingguoyuan communities of Shijingshan district in Beijing, China, between December 2011 and April 2012. The detailed procedures of this cohort study have been previously described [22]. Initially, 9540 participants (≥40 years old) were enrolled in the baseline survey from December 2011 to April 2012, and we excluded participants without brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity (ba-PWV) measurements and those who had already reported a history of stroke or myocardial infarction at baseline. Finally, 8828 eligible subjects with a median follow-up of 9.87 years were included in this analysis. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Peking University First Hospital, and each participant provided written informed consent. The study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The procedures followed were in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Data collection

As described in our previous report [22], all participants were interviewed by trained research coordinators using a standardized questionnaire to collect baseline data, including demographic characteristics, lifestyle, medical history, and medications. The term “current smoking” was defined as smoking one cigarette per day for at least six months. The term “Current drinking” was defined as drinking once per week for at least six months. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height in meters squared (m2). Peripheral blood pressure (pBP) was measured using an Omron HEM-7117 electronic sphygmomanometer (Kyoto, Japan), following the standard protocol. Triplicate measurements on the right arm were performed with ≥1 min intervals between successive readings. Each patient’s peripheral SBP (pSBP) and peripheral diastolic blood pressure(pDBP) used in the analysis were calculated as the mean the three consecutive measurements.

After overnight fasting, venous blood samples were obtained from each participant by venipuncture. Serum samples were used to measure fasting blood glucose (FBG), total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TGs), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and a 2-h oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) using a Roche C8000 Automatic Analyzer. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) [23].

Hypertension was defined as SBP ≥ 140 mmHg and/or DBP ≥ 90 mmHg and/or the use of anti-hypertensive medications and/or a history of hypertension. Diabetes was defined as FBG ≥ 7.0 mmol/l or/and OGTT ≥ 11.1 mmol/l or/and use of anti-diabetes medications or/and a history of diabetes. Dyslipidemia was self-reported or defined as receiving any lipid-lowering medications or concentrations of TG ≥ 1.7 mmol/L (150 mg/dL), total cholesterol (TC) ≥ 5.18 mmol/L (200 mg/dL), LDL-C ≥ 3.37 mmol/L (130 mg/dL) or HDL-C < 1.04 mmol/L (40 mg/dL). CVD was defined as any self-reported history of coronary heart disease, stroke, or transient ischemic attack.

Measurement of inter-arm systolic blood pressure

We performed simultaneous blood pressure measurements on all four extremities while participants were in the supine position after resting for at least 5 min using an arteriosclerosis detection device (BP203RPE III, Omron Healthcare, Kyoto, Japan) by a trained technician following a standard protocol. The details of this method have been described and validated previously [24].

The inter-arm systolic blood pressure difference was calculated as the SBP of the right arm minus the SBP of the left arm. The absolute value of IASBPD, denoted by |IASBPD|, was then determined. Participants were stratified into two groups in accordance with the 2024 European Society of Hypertension Guidelines, utilizing an |IASBPD| threshold of ≥10 mmHg [25]. The IASBPD was further categorized into four distinct groups: 0–10 mmHg (right arm higher by <10 mmHg), ≥10 mmHg (right arm higher by ≥10 mmHg), −10 to <0 mmHg (left arm higher by ≤10 mmHg), and <−10 mmHg (left arm higher by >10 mmHg).

Outcomes

Data on participant’ deaths were collected from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (National Mortality Surveillance System) and Beijing Municipal Health Commission (Inpatient Medical Record Home Page System). The International Classification of Diseases in the 10th Revision (ICD-10) was used to classify the leading cause of death. The endpoints included all-cause death and CV death (I00-I99) [26]. We defined the follow-up time from baseline to death of the participants or the end of the follow-up (December 31, 2021).

Statistics

For continuous variables, data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range), and categorical variables are expressed as numbers (percentages). The differences between groups were compared using the t-test, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), or Kruskal–Wallis rank test for continuous variables as appropriate, and the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables as appropriate.

A generalized additive model using a spline smoothing function was employed to explore the relationship between IASBPD and mortality. Kaplan–Meier survival plots were generated to illustrate survival from baseline to the time of mortality. Univariate and multivariat Cox regression analyses were conducted to estimate the relationships between IASBPD and mortality, adjusting for potential confounders (including baseline age, body mass index, sex, current smoking, current drinking, eGFR, diabetes, antidiabetic treatment, total cholesterol, triglycerides, lipid-lowering treatment, and anti-hypertensive treatment). Additionally, the right-arm pSBP measurements were intentionally selected as the adjustment covariate because they represent the conventional clinical standard for blood pressure assessment and serve as a stable “baseline” reference.

All analyses were performed using Empower(R) (version:2.0, www.empowerstats.com, X&Y Solutions Boston, MA, USA) and R (version:3.5.1, http://www.R-project.org). A p-value < 0.05 (2-sided) was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of all participants according to IASBPD’s four groups are shown in Table 1. A total of 8628 subjects were included, with a mean age of 56.58 ± 8.97 years, and 5566 (64.51%) were female. Among them, 380 (4.40%) had an IASBPD ≥ 10 mmHg, and 409 (4.74%) had an IASBPD < −10 mmHg. Participants with higher IASBPD levels were older. They had higher BMI, pSBP, pDBP, TGs and FBG levels, as well as higher rates of hypertension, anti-hypertensive treatment, diabetes mellitus, and antidiabetic treatment.

We further analyzed the baseline characteristics of the participants using |IASBPD| (≥10 mm Hg). A total of 908 (10.52%) patients had |IASBPD| ≥10 mmHg. The median |IASBPD| was 3.00 (2.00–6.00) mmHg. The mean age of patients with |IASBPD| ≥10 mmHg was significantly greater than those with |IASBPD| <10 mmHg (57.67 ± 9.63 vs. 56.46 ± 8.88, respectively, P < 0.001). Individuals with |IASBPD| ≥10 mmHg were older at baseline and had higher BMI, pSBP, pDBP, TGs and FBG levels. Moreover, they presented with lower baseline eGFR and HDL-C levels. The baseline characteristics were similar to those of the four IASBPD groups (Supplementary Table S1).

Associations of the IASBPD with the risk of mortality

During a median follow-up of 9.87 years, 442 cases of all-cause mortality (5.19%) and 138 cases of cardiovascular mortality (1.62%) occurred. Participants with |IASBPD| ≥10 mmHg exhibited significantly higher rates of all-cause mortality (7.37% vs. 4.94%, P = 0.002) and cardiovascular mortality (2.57% vs. 1.51%, P = 0.018) compared to those with |IASBPD| <10 mmHg. Higher IASBPD levels were independently associated with increased all-cause mortality risk (Supplementary Table S2).

The smooth curve in Fig. 1 reflects the relationship between the IASBPD and mortality. A U-shaped curve was observed between IASBPD and all-cause mortality, It aslo showed monotonic mortality risk escalation with left-arm-dominant IASBPD magnitude versus flat trends for right-arm differences (Fig. 1A). However, the trend in the effect of IASBPD on cardiovascular mortality was nonlinear (Fig. 1B).

Smoothing curve showing the effects of IASBPD on risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. A All-cause mortality; B Cardiovascular mortality. IASBPD Inter-arm systolic blood pressure difference, HR hazard ratio. Adjusted for age, body mass index, sex, current smoking, current drinking, estimated glomerular filtration rate, diabetes, antidiabetic treatment, total cholesterol, triglycerides, lipid-lowering treatment, and anti-hypertensive treatment

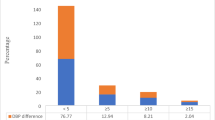

The Kaplan–Meier curve suggested that the greater the difference in |IASBPD|, the higher the cumulative risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. The Log-rank test showed a statistically significant difference (all-cause mortality, P = 0.0017, cardiovascular mortality, P = 0.0152, Fig. 2A, C). The greater the difference in IASBPD, the higher is the cumulative risk of all-cause mortality. The Log-rank test revealed a significant difference (P = 0.0115, Fig. 2B). However, there was no significant difference in the cardiovascular mortality between the four groups (Fig. 2D).

Kaplan–Meier survival curve for mortality by IASBPD. A Kaplan–Meier survival curve for all-cause mortality was stratified by |IASBPD| (<10 vs. ≥10 mmHg). B Kaplan–Meier survival curve for all-cause mortality was stratified by the four IASBPD groups. C Kaplan–Meier survival curve for cardiovascular mortality stratified by |IASBPD| (<10 vs ≥10 mmHg). D Kaplan–Meier survival curve for cardiovascular mortality stratified by IASBPD four groups. IASBPD, inter-arm systolic blood pressure difference. The P-value obtained using the log-rank test was used for each comparison

Multivariate Cox Regression analysis was used to evaluate the association between IASBPD and all-cause mortality (Table 2). After adjusting for covariates, each 1 mmHg increase in |IASBPD| was associated with a 2% increase in the risk of all-cause mortality (adjust hazard ratio, HR = 1.02, 95% CI: 1.00–1.04, P = 0.011). Compared to the group with |IASBPD| <10 mmHg, the group with |IASBPD| ≥10 mmHg group had a 53% increase in the risk of all-cause mortality (adjusted HR = 1.53, 95% CI: 1.18 - 2.00, P = 0.002), and the association still existed after adjusting for pSBP. When the 0–10 mmHg (mean right arm higher <10 mmHg) group was used as the reference group, the risk of all-cause mortality was not significantly increased in the right arm higher ≥10 mmHg group (adjusted HR = 1.17, 95% CI: 0.74–1.84, P = 0.507) or −10–< 0 mmHg (left arm higher by ≤10 mmHg, adjusted HR = 0.90, 95%CI: 0.74–1.11, P = 0.329). However, the risk of all-cause mortality significantly increased by 59% in the IASBPD < -10mmHg (mean left arm higher >10 mmHg) group (adjusted HR = 1.59, 95% CI: 1.10–2.30, P = 0.013). The results remained significant after adjusting for pSBP (adjusted HR = 1.56, 95% CI: 1.08–2.24, P = 0.018).

The association between IASBPD and cardiovascular mortality is presented in Table 3. Compared to the group with |IASBPD| <10 mmHg, the group with |IASBPD| ≥10 mmHg group had a 71% increase in the risk of cardiovascular mortality (adjusted HR = 1.71, 95% CI: 1.09–2.70, P = 0.021), and the association still existed after adjusting for pSBP(adjusted HR = 1.59, 95% CI: 1.01–2.51, P = 0.047). After adjusting for covariates, there was no significant increase in the IASBPD < −10 mmHg (means left arm higher >10 mmHg) group, but the trend was consistent with all-cause mortality risk (HR = 1.58, 95% CI: 0.84–2.97, P = 0.155).

To evaluate whether a large inter-arm systolic blood pressure difference (|IASBPD| ≥10 mmHg) is an independent prognostic factor irrespective of baseline left-arm systolic blood pressure, we performed subgroup analyses within the elevated left-arm systolic blood pressure (L-SBP ≥ 140 mmHg) and normal L-SBP (L-SBP < 140 mmHg) groups as detailed in Table S3. In the elevated L-SBP group, individuals with |IASBPD| ≥10 mmHg (n = 310) had a significantly higher risk of all-cause mortality compared to those with |IASBPD| <10 mmHg (n = 1093) after multivariable adjustment for covariates, with an adjusted HR of 1.63 (95% CI: 1.09–2.46, P = 0.018). Similarly, in the normal L-SBP group, individuals with |IASBPD| ≥10 mmHg (n = 218) exhibited a significantly elevated risk of the all-cause mortality compared to those with |IASBPD| <10 mmHg (n = 2744) following adjustment for the same covariates, yielding an adjusted HR of 1.93 (95% CI: 1.04–3.55, P = 0.036). The interaction term between L-SBP group (elevated/normal) and |IASBPD| (≥10 vs. <10 mmHg) was not statistically significant (P-interaction = 0.737), indicating that the association between IASBPD and mortality was consistent across L-SBP strata.

In analyses of the IASBPD four groups, the limited number of events (35 events in the left arm higher >10 mmHg group and 21 events in the right arm higher ≥10 mmHg group) raised concerns about model overfitting, despite the adjustment for 12 covariates. To address this, we applied least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression to select the most relevant predictors from the following variables: age, body mass index, sex, current smoking, current drinking, eGFR, diabetes, antidiabetic treatment, total cholesterol, triglycerides, lipid - lowering treatment, and anti - hypertensive treatment. LASSO regression identified age, sex, eGFR, and diabetes as as the most influential predictors. These variables were subsequently used in multivariable models to reassess the association between IASBPD and all-cause mortality. The results—direction, magnitude, and statistical significance remained robust and consistent with the original fully adjusted models, as shown in Supplementary Table S4.

Discussion

Previous research has suggested that increased IASBPD may serve as a predictor of mortality. However, the specific implications of discrepancies between SBP readings in the left and right arms have not been thoroughly investigated. Our study reveals that within populations exhibiting elevated IASBPD, individuals with a higher left arm SBP difference were associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality. A similar trend was also observed for cardiovascular mortality.

This phenomenon can be attributed to a confluence of anatomical, hemodynamic, and pathophysiological factors. In our study cohort, the SBP was marginally higher in the left arm compared to the right, with a correspondingly elevated detection rate of IASBPD in the left arm (4.74% vs. 4.40%). This asymmetry may stem from both methodological and biological determinants. Methodologically, the larger sample size of the left-arm subgroup (n = 409 vs. n = 380) and the higher baseline SBP may have enhanced the statistical sensitivity for detecting mortality associations. Biologically, anatomical differences in arterial origins may contribute to lateralized blood pressure patterns: the right brachial artery derives from the innominate artery via the right subclavian artery, whereas the left brachial artery originates directly from the aortic arch through the left subclavian artery [27]. While this configuration typically yields slightly higher right-arm pressures physiologically, our observed left-arm SBP elevation implies potential vascular pathology. Specifically, it may indicate asymmetrical atherosclerosis, hemodynamic disturbances, or subclavian/proximal vascular dysfunction—findings that align with prior evidence positioning left-arm IASBPD as a marker of systemic vascular disease and mortality risk [28]. Mechanistically, post-hoc analyses revealed that participants with IASBPD ≥ 10 mmHg exhibited significantly higher ba-PWV compared to those with smaller differences (1747.14 ± 441.23 vs. 1633.15 ± 359.30 cm/s, P < 0.001). In our prior published research, we indeed observed a positive correlation between elevated IASBPD and baPWV (OR = 1.001, P < 0.001) [29]. These suggest that asymmetric arterial stiffening disrupts pressure propagation, particularly in aging or metabolically compromised individuals—a finding consistent with established links between aortic stiffness and peripheral pressure discordance [30, 31]. Notably, the partial mediation by ba-PWV implies coexisting mechanisms: while systemic arterial stiffening contributes to mortality risk, localized vascular pathologies (e.g., subclavian atherosclerosis) manifesting as IASBPD may independently exacerbate outcomes. This dual mechanism aligns with our observation that left-arm asymmetries correlate more strongly with atherosclerotic burden than right-arm variations [32]. However, the clinical interpretation of these findings requires caution given methodological limitations in existing literature. Most prior IASBPD studies employed sequential rather than simultaneous arm measurements, potentially confounding true pressure differences. Furthermore, the paucity of studies systematically analyzing arm-specific SBP patterns underscores the need for standardized protocols to clarify the prognostic significance of lateralized blood pressure disparities.

IASBPD have been increasingly recognized as a clinical indicator of asymmetric arterial stenosis in upper-extremity vasculature, with hemodynamic alterations typically manifesting as reduced pressure on the stenotic side. The subclavian artery represents the most prevalent site of stenosis, accounting for ~88% of such cases [4]. While our primary analysis focused on left-arm SBP. elevation as the predominant contributor to IASBPD, we acknowledge that right-arm SBP reduction—secondary to stenosis of the right subclavian or innominate artery—may also drive significant inter-arm discrepancies. Notably, only 0.13% of our cohort (n = 12) exhibited right-arm SBP ≤ 90 mmHg, a prevalence substantially lower than anticipated from anatomical models. This discrepancy may be attributed to the relative anatomical protection of the innominate artery compared to the left subclavian artery. Originating directly from the aortic arch, the left subclavian artery demonstrates heightened susceptibility to atherosclerotic stenosis due to its exposure to turbulent flow dynamics and mechanical stress [21]. Therefore, in our analysis, there was no significant association between the reduction in right - arm systolic blood pressure and mortality. The absence of mortality correlation with right-arm-dominant SBP elevation warrants mechanistic interpretation. First, the conventional IASBPD threshold (≥10 mmHg) may lack sensitivity for detecting right-arm-specific hemodynamic perturbations, as subtle pressure gradients caused by non-occlusive lesions or branching anomalies might evade clinical detection. Second, right-arm SBP elevation may reflect compensatory hemodynamic adjustments to anatomical variations (e.g., aberrant subclavian artery origins) rather than atherosclerotic pathology. Unlike left-sided IASBPD, which strongly correlates with aortic arch atherosclerosis, right-arm pressure discordance could be modulated by benign vascular adaptations, thereby attenuating its prognostic significance. In summary, a left-arm SBP ≥ 10 mmHg was significantly associated with increased mortality, whereas the same threshold in the right arm showed no such association. While this discrepancy may be partially attributable to statistical power, previous hemodynamic studies suggest that left-arm SBP more closely reflects central aortic pressure due to its direct anatomical connection to the aortic arch via the left subclavian artery. This lends biological plausibility to the use of left-arm SBP ≥ 10 mmHg as a more sensitive clinical risk marker. Nevertheless, this should not be interpreted to suggest that right-arm SBP differences lack pathophysiological significance.

The relationship between IASBPD and all-cause mortality remains inconsistently characterized across epidemiological studies, likely reflecting variations in cohort risk profiles and methodological approaches. While the Framingham Heart Study (n = 3390) found no mortality association in its low-risk, middle-aged population (HR = 1.02, 95%CI:0.76–1.38) [33]. our findings align with Shanghai cohort data (n = 3133) demonstrating significant risk elevation in participants [12], This divergence suggests IASBPD’s prognostic utility may be context-dependent, with heightened predictive value in populations exhibiting baseline vascular vulnerability. Our previous meta-analysis (HR = 1.28, 95% CI:0.89–1.85, P = 0.18) initially revealed nonsignificant pooled effects, yet substantial heterogeneity (I² = 65%, P = 0.01) prompted sensitivity analyses. Exclusion of outlier studies unmasked significant mortality risk for IASBPD ≥ 10 mmHg (HR = 1.43, 95% CI:1.01–2.03, P = 0.04) [34], underscoring the critical influence of cohort selection on observed effects. Notably, subanalyses in high-risk subgroups—including hypertensive populations [15] and patients with peripheral vascular disease [19]—consistently demonstrate IASBPD’s capacity to stratify mortality risk. These collective findings position IASBPD as a pragmatic clinical indicator, particularly valuable for risk assessment in populations with preexisting cardiovascular compromise where subtle hemodynamic disturbances carry amplified prognostic significance. In our present study, stratified analyses further demonstrated that IASBPD ≥ 10 mmHg independently predicted an increased risk of all-cause mortality in participants with both elevated (≥140 mmHg) and normal (<140 mmHg) baseline systolic blood pressure. A formal test for interaction indicated that baseline L-SBP level did not significantly modify this association (P for interaction = 0.737), suggesting that the prognostic relevance of IASBPD is consistent across blood pressure categories. Collectively, these findings support the broader applicability of a large IASBPD as a robust mortality risk marker and advocate for its inclusion in routine cardiovascular risk assessment—regardless of baseline blood pressure status.

The relationship between IASBPD and the risk of cardiovascular death remains controversial. The Vietnam experience study found no significant association between elevated IASBPD and cardiovascular mortality risk after adjusting for confounding variables [35], suggesting that IASBPD did not enhance the Framingham risk score’s predictive power regarding mortality. This finding may be limited by the relatively low prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors in the study cohort. Similarly, a study conducted in Shanghai reported no statistically significant difference between elevated IASBPD and cardiovascular mortality [12], which was potentially influenced by the low detection rate of elevated IASBPD (6.4%) in that study. Although some scholars argue that the effects of atherosclerosis differ between the coronary and peripheral arteries, thereby diminishing the link between IASBPD and cardiovascular mortality [36], our previous studies have shown significant correlations between IASBPD and various cardiovascular risk factors [29], suggesting that an increase in IASBPD may more accurately reflect the burden of cardiovascular risk factors. Our previous meta-analysis indicated that individuals with |IASBPD| ≥10 mmHg experienced a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular mortality compared to those with |IASBPD| <10 mmHg (HR = 1.88, 95% CI: 1.31–2.71, P < 0.01), with minimal heterogeneity among the studies (P = 0.27, I² = 23.0%) [34]. Further individual-level meta-analyses have confirmed that after adjusting for the Framingham risk score, an increase in IASBPD is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease [5].

The attenuation of hazard ratios (33% reduction) upon adjustment for hypertension, diabetes, and lipid profiles in our fully adjusted models (Table 3) suggests these traditional risk factors mediate approximately one-third of IASBPD’s CVD mortality association. This aligns with mechanistic studies positioning IASBPD as an integrative marker of early vascular dysfunction preceding clinical events. Notably, the null associations with myocardial infarction (HR = 1.41, 0.92–2.18) and cerebral infarction (HR = 1.11, 0.88–1.40) in our cohort—consistent with prior reports [14, 20]—suggest IASBPD primarily reflects systemic vascular aging rather than localized atherosclerotic effects. This distinction may explain the observed mortality discordance: as a surrogate for aortic stiffness and global arterial remodeling, IASBPD’s predictive capacity emerges most clearly in studies capturing pan-vascular pathophysiology rather than isolated coronary/cerebral events.

Persisting uncertainties regarding IASBPD’s anatomical specificity (aortic vs. coronary lesions) and temporal dynamics (incident vs. progressive differences) underscore the need for targeted investigations. Future studies should incorporate advanced vascular imaging to disentangle localized plaque burden from systemic arterial degradation, while standardized IASBPD protocols (simultaneous bilateral measurements, longitudinal monitoring) could enhance clinical interpretability.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the participants were drawn from a Chinese community-based population, which raises questions about the generalizability of our findings to other populations. Second, reliance on a single measurement may be less accurate than multiple repeated assessments. Nonetheless, previous reproducibility studies have shown that as far as the BP ratio or difference is concerned, the intersession variation is small [37]. Some investigations have reported that a single reading is sufficient for screening individuals based on the IASBPD [38]. Third, although our multivariable models adjusted for 12 covariates, the relatively limited number of outcome events in subgroup analyses may have affected the precision of the effect estimates. To address this, we performed sensitivity analyses using covariate-reduced models (Supplementary Table S4), which yielded consistent results and support the robustness of our findings. Nevertheless, validation in larger and more diverse cohorts is warranted. Finally, we could not exclude patients with subclavian artery stenosis, which is anatomically related to IASBPD [39]. Future prospective studies that exclude individuals with preexisting subclavian artery disease would help clarify the impact of IASBPD on mortality risk.

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate that elevated IASBPD is significantly associated with the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in a Chinese community-based population, and this association remains independent of pSBP. Furthermore, individuals with a higher SBP difference in the left arm exhibited a more pronounced correlation with all-cause mortality risk.

References

Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Whelton PK, He J. Worldwide prevalence of hypertension: a systematic review. J Hypertens. 2004;22:11–9.

Forouzanfar MH, Liu P, Roth GA, Ng M, Biryukov S, Marczak L, et al. Global burden of hypertension and systolic blood pressure of at least 110 to 115 mm Hg, 1990-2015. JAMA. 2017;317:165–82.

Mancia G, Kreutz R, Brunström M, Burnier M, Grassi G, Januszewicz A, et al. 2023 ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension Endorsed by the International Society of Hypertension (ISH) and the European Renal Association (ERA). J Hypertens. 2023;41:1874–2071.

Chinese expert consensus on the four-limb blood pressure measurement in adults. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2021;49:963–71.

Clark CE, Warren FC, Boddy K, McDonagh STJ, Moore SF, Goddard J, et al. Associations between systolic interarm differences in blood pressure and cardiovascular disease outcomes and mortality: individual participant data meta-analysis, development and validation of a prognostic algorithm: the INTERPRESS-IPD Collaboration. Hypertension. 2021;77:650–61.

Heneghan C, Perera R, Mant D, Glasziou P. Hypertension guideline recommendations in general practice: awareness, agreement, adoption, and adherence. Br J Gen Pr. 2007;57:948–52.

Sun L, Zou T, Wang BZ, Liu F, Yuan QH, Ma YT, et al. Epidemiological investigation into the prevalence of abnormal inter-arm blood pressure differences among different ethnicities in Xinjiang, China. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0188546.

Canepa M, Milaneschi Y, Ameri P, AlGhatrif M, Leoncini G, Spallarossa P, et al. Relationship between inter-arm difference in systolic blood pressure and arterial stiffness in community-dwelling older adults. J Clin Hypertens. 2013;15:880–7.

Gopalakrishnan S, Savitha AK, Rama R. Evaluation of inter-arm difference in blood pressure as predictor of vascular diseases among urban adults in Kancheepuram District of Tamil Nadu. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2018;7:142–46.

Yu Y, Liu L, Lo K, Tang S, Feng Y. Prevalence and associated factors of inter-arm blood pressure difference in Chinese community hypertensive population. Postgrad Med. 2021;133:188–94.

Ena J, Pérez-Martín S, Argente CR, Lozano T. Association between an elevated inter-arm systolic blood pressure difference, the ankle-brachial index, and mortality in patients with diabetes mellitus. Clin Investig Arterioscler. 2020;32:94–100.

Sheng CS, Liu M, Zeng WF, Huang QF, Li Y, Wang JG. Four-limb blood pressure as predictors of mortality in elderly Chinese. Hypertension. 2013;61:1155–60.

Clark CE, Taylor RS, Butcher I, Stewart MC, Price J, Fowkes FG, et al. Inter-arm blood pressure difference and mortality: a cohort study in an asymptomatic primary care population at elevated cardiovascular risk. Br J Gen Pr. 2016;66:e297–308.

Yun C, Xin Q, Zhang S, Chen S, Wang J, Wang C, et al. Combined effect of inter-arm systolic blood pressure difference and carotid artery plaque on cardiovascular diseases and mortality: a prospective cohort study. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:904685.

Clark CE, Taylor RS, Shore AC, Campbell JL. The difference in blood pressure readings between arms and survival: primary care cohort study. BMJ. 2012;344:e1327.

Clark CE, Steele AM, Taylor RS, Shore AC, Ukoumunne OC, Campbell JL. Interarm blood pressure difference in people with diabetes: measurement and vascular and mortality implications: a cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:1613–20.

Aboyans V, Criqui MH, McDermott MM, Allison MA, Denenberg JO, Shadman R, et al. The vital prognosis of subclavian stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1540–5.

Hsu PC, Lee WH, Tsai WC, Chu CY, Lee CS, Yen HW, et al. Usefulness of four-limb blood pressure measurement in prediction of overall and cardiovascular mortality in acute myocardial infarction. Int J Med Sci. 2020;17:1300–06.

Durrand JW, Batterham AM, O’Neill BR, Danjoux GR. Prevalence and implications of a difference in systolic blood pressure between one arm and the other in vascular surgical patients. Anaesthesia. 2013;68:1247–52.

Kranenburg G, Spiering W, de Jong PA, Kappelle LJ, de Borst GJ, Cramer MJ, et al. Inter-arm systolic blood pressure differences, relations with future vascular events and mortality in patients with and without manifest vascular disease. Int J Cardiol. 2017;244:271–76.

Ochoa VM, Yeghiazarians Y. Subclavian artery stenosis: a review for the vascular medicine practitioner. Vasc Med. 2011;16:29–34.

Fan F, Qi L, Jia J, Xu X, Liu Y, Yang Y, et al. Noninvasive central systolic blood pressure is more strongly related to kidney function decline than peripheral systolic blood pressure in a chinese community-based population. Hypertension. 2016;67:1166–72.

Ma YC, Zuo L, Chen JH, Luo Q, Yu XQ, Li Y, et al. Modified glomerular filtration rate estimating equation for Chinese patients with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2937–44.

Zheng M, Xu X, Wang X, Huo Y, Xu X, Qin X, et al. Age, arterial stiffness, and components of blood pressure in Chinese adults. Medicine. 2014;93:e262.

Kreutz R, Brunström M, Burnier M, Grassi G, Januszewicz A, Muiesan ML, et al. 2024 European Society of Hypertension clinical practice guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur J Intern Med. 2024;126:1–15.

Liu S, Wu X, Lopez AD, Wang L, Cai Y, Page A, et al. An integrated national mortality surveillance system for death registration and mortality surveillance, China. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94:46–57.

Berezovsky DR, Bordoni B. Anatomy, shoulder and upper limb, forearm arteries. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

Aune D, Huang W, Nie J, Wang Y. Hypertension and the risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality: an outcome-wide association study of 67 causes of death in the National Health Interview Survey. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021:9376134.

Ma W, Zhang B, Yang Y, Qi L, Meng L, Zhang Y, et al. Correlating the relationship between interarm systolic blood pressure and cardiovascular disease risk factors. J Clin Hypertens. 2017;19:466–71.

Lee SJ, Kim H, Oh BK, Choi HI, Lee JY, Lee SH, et al. Association of inter-arm systolic blood pressure differences with arteriosclerosis and atherosclerosis: a cohort study of 117,407 people. Atherosclerosis. 2022;342:19–24.

Su HM, Lin TH, Hsu PC, Chu CY, Lee WH, Chen SC, et al. Association of interarm systolic blood pressure difference with atherosclerosis and left ventricular hypertrophy. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41173.

Clark CE. The interarm blood pressure difference: do we know enough yet?. J Clin Hypertens. 2017;19:462–65.

Weinberg I, Gona P, O’Donnell CJ, Jaff MR, Murabito JM. The systolic blood pressure difference between arms and cardiovascular disease in the Framingham Heart Study. Am J Med. 2014;127:209–15.

Li M, Fan F, Qiu L, Ma W, Zhang Y. Association of an inter-arm systolic blood pressure difference with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Clin Hypertens. 2023;25:1069–78.

White J, Mortensen LH, Kivimäki M, Gale CR, Batty GD. Interarm differences in systolic blood pressure and mortality among US army veterans: aetiological associations and risk prediction in the Vietnam Experience Study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21:1394–400.

Mohamadi MH, Rai A, Rezaei M, Khatony A. Lack of association between interarm systolic blood pressure difference and coronary artery disease in patients undergoing elective coronary angiography. Int J Hypertens. 2021;2021:6665039.

Pan CR, Staessen JA, Li Y, Wang JG. Comparison of three measures of the ankle-brachial blood pressure index in a general population. Hypertens Res. 2007;30:555–61.

Park SJ, Son JW, Hong KS, Choi HH. Effect of inter-arm blood pressure differences on outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention. J Cardiol. 2020;75:648–53.

Tanaka Y, Fukui M, Tanaka M, Fukuda Y, Mitsuhashi K, Okada H, et al. The inter-arm difference in systolic blood pressure is a novel risk marker for subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with type 2 diabetes. Hypertension Res. 2014;37:548–52.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFC2500503), National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (High Quality Clinical Research Project of Peking University First Hospital) (2022CR71), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82170452, 81703288).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, M., Fan, F., Jia, J. et al. Higher systolic blood pressure difference in left not right upper limb is associated with all-cause mortality risk in a community-based population. Hypertens Res 48, 3187–3197 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-025-02361-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-025-02361-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Measuring both arms: a simple step to gain valuable insights

Hypertension Research (2025)