Abstract

Chronological age is a well-established risk factor for Hypertension (HTN), yet while biological ageing markers such as epigenetic age acceleration (EAA), have been associated with HTN, findings are inconsistent. This study aimed to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the association between EAA, HTN and blood pressure (BP) to provide an understanding of the role of EAA in HTN development and progression. Six databases were searched, and studies which reported associations between DNA and HTN, and/or BP were included. Functional enrichment analysis was conducted using DAVID and STRING to elucidate underlying molecular pathways. From 4334 studies, 165 met the inclusion criteria. Qualitative analysis indicated that 17.0% of studies reporting global methylation and 49.1% of studies reporting gene-specific methylation demonstrated significant associations with HTN and/or BP. A random effects meta-analysis of 16,136 participants from 8 studies using three epigenetic clock algorithms demonstrated that HTN was associated with increased EAA (β: 0.29, 95%Cl: 0.15–0.43; P < 0.0001). All three individual epigenetic clocks demonstrated a positive association between clinically measured HTN and EAA (Horvath β: 0.33, 95%Cl: 0.08–0.58, P = 0.010; Hannum β: 0.64, 95%Cl: 0.09–1.20; PhenoAge β: 1.21, 95%Cl: 0.56–1.86), whereas this relationship was not clear when using self-reported HTN. This study is the first to systematically demonstrate that HTN is associated with EAA. We recommend the use of clinically measured over self-reported HTN in appropriately powered studies of epigenetic age to obtain an accurate understanding of BP regulation/HTN on the epigenome, supporting pathways to translation and development of novel therapeutic targets for HTN.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypertension (HTN) is the leading modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD), a highly prevalent worldwide contributor to mortality, responsible for 8.5 million deaths annually [1]. While advancements in diagnosis and treatment have been observed in high- and middle-income countries, HTN remains highly prevalent, affecting 31% of adults worldwide. From 1990 to 2019, the global prevalence of HTN has doubled and more than 50% of HTN cases remain undiagnosed [2, 3]. Despite the availability of medical and lifestyle interventions to improve cardiovascular outcomes, HTN control rates remain poor, with only 24% of women and 20% of men worldwide achieving target BP [3, 4].

Hundreds of common single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been identified for HTN, a heritable complex polygenic trait. Genetic variants, however, do not fully explain HTN heritability suggesting the involvement of additional mechanisms [5,6,7]. Epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation, have been implicated in HTN, BP and stroke [8,9,10]. DNA methylation is responsive to environmental factors, such as diet and nutritional status, and may mediate the interaction between genetic predisposition and development and progression of HTN [11,12,13,14].

Specific subsets of CpG sites undergo programmed methylation changes which have informed the development of biological clock algorithms to provide estimates of epigenetic age [15]. The difference between chronological and epigenetic age provides a measure of EAA where higher epigenetic age than chronological age indicates accelerated epigenetic age, and vice versa. Various epigenetic clocks, including the Horvath and Hannum algorithms, have been developed to predict epigenetic age and its association with disease states [16,17,18]. Second-generation clock algorithms, such as DNAmGrimAge and DNAmPhenoAge, incorporate age-related biomarkers to improve accuracy in assessing biological ageing and estimating all-cause mortality risk [18,19,20]. Recently, epigenetic clocks such as Horvath, Hannum and PhenoAge have demonstrated clinical utility, in patients with chronic kidney disease who exhibited increased EAA, an effect mitigated by transplantation but not dialysis [21].

Despite growing interest in this area, current evidence linking epigenetic age and BP or HTN remains conflicting. Several studies have reported significant associations between epigenetic clock algorithms, such as Horvath and HTN as well as systolic and diastolic BP [22, 23]. In contrast, other studies have reported no such associations [24, 25]. This inconsistency extends to studies investigating HTN and/or BP using more targeted DNA methylation assessment methods, including global, gene-specific and epigenome-wide approaches [26,27,28,29]. Consequently, despite increasing evidence supporting the involvement of DNA methylation in HTN [8, 10], there is are a lack of systematic analysis and evaluation of the existing evidence linking various measures of DNA methylation (global, gene-specific, epigenome-wide), epigenetic age and HTN.

The aim of this study was to conduct a systematic review to investigate the association between DNA methylation and HTN and/or BP in adults. Furthermore, we performed a comprehensive meta-analysis of studies in adults reporting epigenetic age performed using various clock algorithms to determine the association between HTN and EAA. Finally, functional enrichment analysis was conducted to explore the relationship between epigenome-wide DNA methylation and biological pathways in HTN.

Methods

This review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Screening of eligible studies, full-text assessment, data extraction, and quality assessment of studies were independently carried out by two authors. Any discrepancies were discussed and resolved by consensus. Studies were selected in line with the PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, Study Type) criteria outlined in Table S1.

Search strategy and study selection

Systematic searches were performed in 6 bibliographic databases (Medline (Ovid), Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Cochrane Library, Web of Science and Scopus). The search covered the period from January 1st 2000 to 14th October 2024 (date of last search). The search strategy combined terms related to DNA methylation (e.g., global, gene-specific, epigenome-wide) and BP (e.g., systolic, diastolic, HTN, high BP). Medical subject headings and keyword searches were conducted in databases where a thesaurus was available (Embase, Medline, CINAHL, Cochrane Library), while keyword searches were performed in other databases (Web of Science, Scopus). Only full text studies involving humans, published in English were included. Detailed search terms and search strategies are provided in Table S2. Retrieved records from databases were exported to the systematic review manager Rayyan [30] for the removal of duplicates. Full-text studies selected for inclusion were further imported into an additional systematic review manager, Covidence (www.covidence.org), where studies were further assessed for full-text eligibility and data extraction.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were deemed eligible for inclusion in this review if they were original, peer-reviewed, full-text articles published in English and met all defined inclusion criteria. These criteria included studies that: (1) assessed DNA methylation, specifically 5-methylcytosine (5mC) (global, gene-specific and epigenome-wide); (2) measured or recorded data on HTN and/or BP; (3) were conducted in adult humans aged >18 years; and (4) investigated an association between DNA methylation and HTN and/or BP. HTN status was defined to the European Society of Hypertension/European Society of Cardiology guidelines (HTN defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥90 mmHg and/or anti-HTN usage) [31] and the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force guidelines (HTN defined as SBP ≥ 130 mmHg and/or DBP ≥ 80 mmHg and/or anti-HTN usage [32]. Additionally, we included studies that defined HTN as self-reported and studies which provided a diagnosis of HTN from medical history. No restrictions were imposed regarding the tissue in which DNA methylation was assessed allowing for a comprehensive analysis of the current landscape of studies. Animal studies, studies involving pregnant women and children, or in vitro studies using human or animal cell lines were excluded from this review (Table S1).

Risk of bias assessment

Bias within each included study was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale [33] a semi-quantitative scale designed to evaluate the quality of non-randomised studies. Study quality was assessed based on the selection criteria of participants, comparability and exposure and outcome assessment. Studies that received a score of 9 stars were considered to have a low risk of bias, and those that scored 7–8 stars were considered to have a medium risk of bias; and those that scored less than 7 were considered to have a high risk of bias.

Data extraction and analysis

A predesigned data collection form was created within Covidence to extract the relevant information from the included studies, including the first author, study design, percentage of male participants, age range, sample size and location where possible. Additionally, a description of the cohorts, such as the names of large prospective cohorts or the diseased population (e.g., patients with HTN), was included. Furthermore, information regarding the type of tissue, molecular technique and outcomes related to DNA methylation was extracted.

A qualitative analysis was presented for associations between DNA methylation (global methylation, gene-specific, and epigenome-wide) and HTN and/or BP, however, due to considerable heterogeneity in study aims, meta-analysis was not appropriate for these measures. Instead, a meta-analysis was conducted to examine the association between HTN and EAA which employed 3 different epigenetic clock algorithms; Horvath, Hannum and PhenoAge.

Meta-analysis

We conducted a random-effects meta-analysis to examine the effect of HTN on EAA. The meta-analysis included studies that investigated the association between HTN and EAA, where EAA was reported as an outcome. Studies eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis measured at least one of the definitions of EAA. Only studies reporting HTN were included rather than other measures of BP due to the low number of studies reporting statistically comparable outcomes for BP. All eligible studies for meta-analysis, defined HTN as SBP > 140 or DBP > 90 and/or use of antihypertensive medication or separately as self-reported HTN.

Subgroup analysis was performed to determine the effect of HTN on each epigenetic clock algorithm, both independently and as a combined effect of the 3 algorithms. While first-generation epigenetic clocks are derived by a linear regression algorithm that trains chronological age against a select set of CpGs [16,17,18] more recent clocks have included additional parameters, such as the inclusion of 9 biomarkers in PhenoAge [18]. Studies using GrimAge [19] were ineligible for inclusion in meta-analysis due to incompatible statistical reporting, such as reporting EAA as a predictor variable, which limited comparability with other studies included for meta-analysis. Furthermore to account for variability in HTN definitions, subgroup analysis was utilised to examine the association between HTN and EAA based on whether HTN was defined by European clinical guidelines [31] or by self-report.

Statistical analysis

Review Manager Version 5.3 software was used to perform a random-effects meta-analysis [34]. We employed a random-effects model to account for expected heterogeneity in effect sizes across clocks and studies. The random-effects model estimates between-study variance, allowing for the assignment of weight to individual studies when calculating an overall pooled effect that reflects this variability. Beta effect estimations and standard errors were extracted from included studies that investigated epigenetic age as an outcome. In studies where standard errors were absent, the standard error was estimated from 95% confidence intervals using Cochrane formulas. Results were expressed as beta effect estimates and 95% confidence intervals, in addition to the overall effect Z value. Pre-specified subgroup analysis, grouped by epigenetic clock and by clinically measured vs self-reported HTN was performed.

Publication bias for studies included in the meta-analysis was assessed through visual inspection of funnel plots, Egger’s regression test and the trim-and-fill procedure using the metafor package within the statistical software platform R (Version 4.1.2) [35, 36].

Heterogeneity was assessed using chi-squared testing (χ value), heterogeneity index (I2) statistics and corresponding P value. Heterogeneity thresholds were predefined according to Cochrane guidelines, which stated that an I2 value between 0% and 40% indicates low heterogeneity, between 30% and 60% represents moderate heterogeneity, between 50% and 90% represents substantial heterogeneity, and between 75% and 100% indicates considerable heterogeneity. Sensitivity analysis was performed by conducting the meta-analysis excluding one study at a time to determine stability of the overall pooled effect across the 3 clock algorithms.

Functional analysis

Functional analysis was conducted separately for previously identified CpG sites associated with BP and/or HTN within epigenome-wide association studies using the DAVID Bioinformatics Resource and the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING), which allowed for the formation of protein-protein interaction networks [37, 38]. Clustering within STRING analysis was performed using the Markov Clustering Algorithm. Overlapping differentially methylated regions (DMR) were determined using the GenomicRanges package (Version 1.46.1) with R (Version 4.1.2) to identify DMRs with the same genomic region prior to visualisation. CpG sites and DMRs associated with BP traits were visualised individually using the InteractiVenn software [39].

Results

Overall, 4334 potentially relevant records were identified through a systematic search of 6 databases. Based on the title and abstract, 584 articles were identified for detailed evaluation. After full-text assessment, 165 studies met the predefined eligibility criteria and were included in this review. Detailed screening, eligibility and selection processes are outlined in Fig. 1.

Characteristics of included studies

Overall, 165 studies were included that involved adults aged 18–99 years, ranging in size from 6 to 17,010 participants. Individuals were recruited from 34 different countries, with the most prevalent being China (29.1%), the USA (24.2%) and Spain (6.1%). DNA methylation was assessed in a gene-specific manner in 45.8% of studies, while 20.9% investigated epigenetic age, 19.8% of studies investigated epigenome-wide methylation, and 14.1% investigated global methylation (Fig. 2A). DNA methylation was predominantly examined in blood (91.1% of studies), followed by tissue (7.1%), saliva (1.8%), plasma (1.2%), and serum (0.6%). DNA methylation was examined in multiple tissues within 2.4% of studies. A total of 24 different techniques were used for DNA methylation analysis, with the majority employing Infinium HumanMethylation 450 K BeadChip microarray (Illumina, San Diego, CA) (23.6%), pyrosequencing (22.4%), Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip microarray (Illumina, San Diego, CA) (18.8%) and methylation-specific PCR (10.9%). Seven studies reported the use of more than one method. Detailed participant characteristics for each of the 165 studies within this review were stratified by global methylation (Table 1), gene-specific methylation (Table 2), epigenome-wide methylation (Table 3) and epigenetic age (Table 4).

A Study characteristics stratified by methylation assessment method, tissue and technique (B) Studies reporting significant associations between BP traits and global DNA methylation stratified by global DNA methylation marker; (C) Assessment of studies reporting significant associations between BP traits and gene-specific DNA methylation

Outcome assessment

Studies were included if they investigated an association between DNA methylation and either HTN or BP, resulting in outcomes being reported separately as either a diagnosis of HTN (38.8%), a measure of BP (34.8%), or both (26.4%) (Tables 1–4). HTN was defined by European guidelines in 64.7% of 116 studies reporting HTN, while 9.5% of studies defined HTN according to American guidelines. In addition, 8.6% of studies reported HTN based on medical history, a further 9.5% based on self-reported HTN, and 0.9% defined HTN as SBP ≥ 160 mmHg and/or DBP ≥ 100 mmHg. Furthermore, 0.9% of studies reported HTN as a binary yes/no answer without further definition, while another 0.9% of studies did not indicate HTN definition and 1.7% of studies reported HTN as solely antihypertensive medication usage. Additionally, 3.4% of studies reported multiple definitions of HTN. Regarding BP measurement, 61.5% of 109 studies reporting BP measured BP in a standardised manner (after a period of rest, seated with multiple measurements taken), 6.4% of studies reported BP levels from medical history, 0.9% measured BP over a 24 h period, 2.8% report multiple BP measurement methods and 28.4% provided an indication of BP measurement without further definition.

Risk of Bias assessment

A case-control design was used in 32.1% of studies, while the majority of studies (55.8%) used a cross-sectional approach. Most of the included studies (54.5%) achieved a moderate rating of 5-6 stars, suggesting moderate methodological quality. A substantial number of studies (43.0%) attained a higher rating of 7-9 stars, indicating good methodological quality, while only 2.4% of studies were rated below 4 stars, indicating lower quality (Table S3).

Global methylation

Global DNA methylation was investigated in 25 publications, including 4 studies within large prospective cohorts and 21 original study cohorts (Table 1). Global DNA methylation analysis was performed in healthy individuals in 16.0% of studies and was investigated in several disease state cohorts, such as HTN (20.0% of studies) and diabetes (16.0% of studies). The majority of studies investigating global methylation, focused on repeat sequences and transposable elements as a proxy, which have been shown to correlate with total genomic content [40, 41]. The remaining studies investigating global methylation assessed DNA methylation as a level of 5 mC or as a percentage of total cytosine (MC/C ratio).

Several studies report conflicting findings in regard to the association between SBP and LINE-1 methylation, with varying directions of association (Fig. 2B) [42, 43]. Three studies report a negative association between DBP and LINE-1 methylation [26, 43, 44]. Furthermore, a single study also reports a negative association between HTN and LINE-1 methylation [45].

Alu methylation was associated with both SBP and DBP with negative and positive associations [26, 46, 47]. Alu methylation was negatively associated with HTN [47] and positively associated with pre-HTN [48]. Additionally, 5mC was negatively associated with HTN [49, 50]. No significant associations were reported between BP traits and MC/C ratio.

Gene-specific DNA methylation

Gene-specific DNA methylation of 138 candidate genes was examined utilising data from 81 distinct studies (Table 2). Significant associations with either BP or HTN were reported for a total of 88 candidate genes. Most studies were conducted in original cohorts comprising individuals with diverse characteristics, including healthy individuals (9.9% of studies), those with HTN (38.3%), and obese individuals (6.2%), in addition to other disease states.

Twenty-five studies reported associations between SBP and DNA methylation examining a total of 45 genes. The most commonly reported genes included Tumour Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-a), Glucocorticoid receptor gene (GR) and Interleukin-6 (IL-6), all of which demonstrated conflicting directions of association between methylation and SBP (Fig. 2C) [51,52,53,54]. Similarly, among the 26 studies reporting an association between DNA methylation and DBP, the most commonly reported genes also included TNF-a, GR and IL-6, along with Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) methylation, which exhibited both positive and negative associations with DBP (Fig. 2b) [54, 55].

Angiotensin II Receptor Type 1 (AGTR1) methylation was the most frequently studied gene in relation to HTN, with studies again reporting both positive and negative associations (Fig. 2C) [56,57,58]. Cystathionine Beta Synthase (CBS) methylation was positively associated with HTN [59, 60], while ADD1 methylation was negatively associated with HTN [61, 62]. MTHFR methylation was positively associated with HTN, in addition to other genes involved in folate and one-carbon metabolism, such as dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) and methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase (MTHFD1) [29, 63, 64].

Epigenome-wide methylation

Epigenome-wide methylation was investigated in 35 studies, resulting in the identification of 1003 CpG sites associated with various BP traits (Fig. 3A). The most commonly reported CpG sites included cg19693031 and cg18120259 which were reported in 5 publications (Table S4). The top genes annotated to these CpGs included Thioredoxin Interaction Protein (TXNIP) and a long intergenic non-protein coding RNA (LOC100132354). In total, CpG sites were annotated to 569 genes, with 61 genes reported in >1 publication. 1391 DMRs were associated with various BP traits (Fig. 3B). Eight DMRs were reported in >1 publication (Table S5).

Functional enrichment analysis of genes annotated from CpG sites significantly associated with any BP trait indicated several highly enriched disease terms, including systemic lupus erythematosus (PFDR = 1.84E-17), schizophrenia (PFDR = 0.001), HTN (PFDR = 0.002), and SBP (PFDR = 0.005) (Table S6). Functional enrichment of the genes annotated from DMRs significantly associated with any BP trait identified biological processes such as regulation of transcription by RNA polymerase II (PFDR = 0.0003), cartilage development (PFDR = 0.0004) and intracellular signal transduction (PFDR = 0.009) (Table S7). Regarding cellular components, significantly associated terms included chromatin (PFDR = 1.59E-07), nucleoplasm (PFDR = 0.0002), post synaptic density (PFDR = 0.003), cell surface (PFDR = 0.032), focal adhesion (PFDR = 0.032), synapse (PFDR = 0.049), and axon (PFDR = 0.049). (Table S7). In terms of molecular function, protein binding was found to be statistically significant (PFDR = 0.0001), in addition to RNA polymerase II-specific DNA-binding transcription factor activity (PFDR = 0.0003), metal ion binding (PFDR = 0.0003), zinc ion binding (PFDR = 0.011), sequence-specific double-stranded DNA binding (PFDR = 0.013), and identical protein binding (PFDR = 0.034) (Table S7). STRING analysis with the confidence setting ‘high’ revealed significant evidence for protein-protein interactions between the products of genes annotated to CpG sites associated with BP (P = 1.46E-07) (Fig. 4). The average node degree was 0.83, while the average local clustering coefficient was 0.27.

Epigenetic age

Fourteen DNA methylation algorithms were implemented across 37 studies investigating epigenetic age (Table 4). Most studies calculated epigenetic age using more than one algorithm, with the Horvath (Pan-tissue) clock being the most frequently used (73.0% of studies). Epigenetic age was most commonly reported as EAA; however, 6 studies additionally reported Delta Age (ΔAge), DiffAge, PCAge, changing rate of age acceleration (ΔAA), and ageing rate [20, 65,66,67,68,69]. The majority of studies within this review demonstrate a very high correlation between epigenetic age and chronological age (r = 0.7–0.9), which is representative of the function of these algorithms, however, some individual studies did report lower correlations between epigenetic and chronological age [70].

Six studies reported positive associations between AgeAccelHorvath and SBP [22, 69,70,71]. Four studies reported positive associations between AgeAccelHannum and SBP [22, 70, 72, 73]. Similarly, 4 studies reported a positive association between PhenoAgeAccel and SBP [18, 22, 72, 73]. GrimAgeAccel was positively associated with SBP in 4 separate studies, while a further study reported a negative association [19, 20, 72, 74, 75].

Four studies reported a positive association between AgeAccelHorvath and DBP [20, 70, 75, 76]. AgeAccelHannum was associated with DBP in 1 study [70], while a positive association between GrimAgeAccel and DBP was reported in 2 studies [72, 74]. No significant associations were reported between DBP and PhenoAgeAccel.

Meta-analysis

A meta-analysis was conducted to examine the association between HTN and EAA. Data from a total of 16,136 individuals across 8 studies were included in the analysis. Beta coefficients and standard errors (or calculated standard errors from published 95% confidence intervals) were obtained from each study. The majority of studies assessed DNA methylation in blood, while 1 study used saliva.

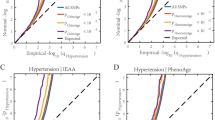

The meta-analysis, using a random-effects model (Fig. 5), demonstrated a significant positive association between HTN and EAA across the three epigenetic clock algorithms (β = 0.29, P < 0.001; 95% Cl: 0.15–0.43, P < 0.0001). Subgroup analysis further revealed that clinically measured HTN as determined by European guidelines [31], was associated with each epigenetic clock individually (Horvath: β = 0.33, 95% Cl: 0.08–0.58, P = 0.010; Hannum: β = 0.64, 95% Cl: 0.09–1.20, P = 0.02; PhenoAge: β = 1.21, 95% Cl: 0.56–1.86, P = 0.0003). Further subgroup analysis based on self-reported HTN status demonstrated no significant association with AgeAccelHorvath (β = 0.09, P = 0.09, 95% Cl: −0.01 to 0.20); however, a significant association with AgeAccelHannum (β = 0.17, P = 0.003, 95% Cl: 0.06–0.28) was observed. Heterogeneity was observed in the overall meta-analysis across the three epigenetic clock algorithms (I2 = 64%, P = 0.001) and for AgeAccelHannum in individuals who reported HTN according to European guidelines (I2 = 78%, P = 0.001). No significant heterogeneity was observed in either the AgeAccelHorvath subgroup, when HTN was either clinically measured or self-reported (I2 = 0%, P = 0.87; I2 = 32%, P = 0.22), or the AgeAccelHannum subgroup when HTN was self-reported (I2 = 0%, P = 0.48), or PhenoAgeAccel (I2 = 0%, P = 0.61) when HTN was clinically measured.

Random effects meta-analysis of the association of HTN with epigenetic age acceleration subgrouped by epigenetic clock algorithm and clinically-defined v self-report of hypertension. Horizontal lines represent the 95% confidence interval (CI) for each study. Diamonds indicate pooled effect and 95%CI for each subgroup and overall effect (Z). χ 2 chi-squared test assesses whether observed difference in results are compatible with chance alone; I2 heterogeneity index (0%–100%); SD, standard deviation; IV, Random, a random effects meta-analysis is applied with weights based on inverse variances

Publication bias and Sensitivity analysis

Visual assessment of publication bias by funnel plot (Figure S1) determined significant asymmetry which was further confirmed by a significant Egger’s regression test (P = 0.0002). The small number of studies included in the meta-analysis or heterogeneity among these studies may have influenced the results of Egger’s regression test and observed asymmetry, introducing potential variability and making limiting the ability to draw definitive conclusions regarding publication bias. Trim-and-fill analysis estimated three missing studies (Figure S2), with the overall association measure based on this analysis remaining significant (β = 0.260, P = 0.0005; I2 = 65.18%, P < 0.0001). Given the observed heterogeneity, we performed a sensitivity analysis of the eight included studies. The overall effect remained consistent overall effect after sequential exclusion of each individual study, (Figure S3) indicating that the findings are stable and not driven by one particular study.

Discussion

This study is the first to demonstrate that HTN is significantly associated with accelerated epigenetic age by systematically evaluating current evidence, highlighting an important role for DNA methylation in the development and pathophysiology of HTN in adults. Furthermore, each epigenetic clock algorithm individually demonstrated that clinically measured HTN was significantly associated with increased EAA.

In our meta-analysis of 16,136 individuals, we demonstrated a significant association between HTN and increased EAA combining three main epigenetic clock algorithms. Accelerated epigenetic ageing was observed in individuals with clinically measured HTN in subgroup analysis using the Horvath clock, despite none of the included studies individually reaching statistical significance [17, 18, 68, 77, 78], perhaps due to a lack of statistical power within individual studies. Similarly, a small meta-analysis using the Horvath clock previously reported accelerated biological ageing in >5600 participants with clinically defined HTN across three pooled studies in which no significant effect was observed in each individual cohort [72]. While results are generally consistent for clinically measured hypertension, there appears to be a disparity in using self-reported HTN which may prevent identification of positive associations between epigenetic age and HTN, introducing potential misclassification bias. Self-reporting is considerably reliable for ruling out HTN, however, the probability of correctly identifying patients with HTN through self-reporting is only mildly sensitive, correctly identifying individuals with HTN in approximately 37% of cases, indicating that a large number of hypertensive individuals remain undiagnosed [79]. In accordance, one well-powered study within our meta-analysis reported no significant association between Horvath EAA and self-reported HTN in >5100 participants; perhaps attributable to the use of self-reported HTN rather than more discriminatory clinical measurement [80]. Subgroup analysis, employing Hannum and PhenoAge clocks, also demonstrated accelerated epigenetic ageing in individuals with both clinically and self-reported HTN despite a lack of consistent evidence across individual studies. Increased EAA was also consistently associated with BP traits, such as SBP and DBP, within studies that were ineligible for meta-analysis (Table 4).

The overall association between HTN and EAA was observed despite each clock using different CpG sites and parameters in the algorithms used to calculate epigenetic age, therefore, it is not surprising that heterogeneity was observed in the meta-analysis. The heterogeneity observed in the overall meta-analysis may reflect differences in study design across the limited number of studies, including variation in study design, epigenetic clock algorithm, participant characteristics and levels of covariate adjustment. The observed heterogeneity likely reflects the biological and methodological diversity inherent to epigenetic ageing measures. The pooled estimate is therefore interpreted with caution, as an overall summary of the association between EAA and HTN rather than a precise effect size. Although the meta-analysis was limited by the small number of studies, the overall positive effect of the meta-analysis remained robust following sensitivity analysis indicating that the pooled result is not driven by one study (Figure S3). Lack of overlap in genomic locations used in epigenetic clock algorithms suggests that each clock investigates a separate measure of biological age, drawing methylation markers from entirely different regions of the genome [81]. Notably GrimAgeAccel was not represented among eligible studies for meta-analysis, however, the overall association of HTN and EAA using three first- and second- generation clocks, suggests wide-ranging perturbations across the epigenome.

The causal relationship between EAA and hypertension remains an area of active investigation. Longitudinal studies have suggested that individuals with higher baseline EAA are at increased risk of developing incident hypertension [82], supporting the hypothesis that accelerated epigenetic aging may predispose to hypertension. Conversely, other evidence indicates that established hypertension may itself contribute to EAA through mechanisms such as vascular remodelling, chronic low-grade inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial injury, which are known to influence DNA methylation patterns [68, 78]. These mechanisms highlight the potential for a feedback loop where increasing EAA and HTN mutually reinforce each other, and it currently remains unclear whether epigenetic alterations precede adverse cardiovascular remodelling events in HTN [83]. It is plausible that epigenetic age acceleration is correlated with HTN but may not lie along the causal pathway of incident HTN. Future research directed towards dissecting molecular mechanisms connecting EAA and HTN may help elucidate the mechanism underlying hypertension physiology. Furthermore, studies investigating whether epigenetic aging influences gene expression at the transcriptomic or proteomic level and development of models to identify key physiological pathways in HTN will be valuable in answering these important questions.

There is currently immense interest in epigenome-wide methylation and epigenetic age investigations. In the systematic review a diverse range of experimental design was observed in included studies (Fig. 2A). Large cohorts such as the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) have employed the 450 K array which has proved very useful and has been extensively used over the past decade [18, 19, 23, 70, 84, 85]. Moving forward studies should take advantage of assays providing more epigenomic coverage e.g., the Generation Scotland Family Health Study utilises the IlluminaMethylationEPIC array which covers over 850 CpG sites [80, 86, 87]. DNA repetitive element methylation, however, is not directly analysed in commonly used methylation arrays and are therefore reported separately. Repeat elements LINE-1 and Alu were the most commonly reported markers of global methylation within this review (Table 1). Global methylation is inversely associated with BP traits in the majority of studies reporting significant outcomes (Fig. 2B) consistent with previous findings [8, 10].

The most frequently reported candidate gene was AGTR1 (Fig. 2C), methylation of which has been inversely associated with HTN [88], while SNPs in AGTR1 result in decreased expression and increased HTN risk [89]. MTHFR methylation was also reported to be associated with HTN (Fig. 2C). Common polymorphisms in MTHFR, resulting in the 677TT genotype yields an increased risk of HTN [90]. Hypermethylation of MTHFR is observed in individuals with the TT genotype, blood pressure is also higher compared to CC counterparts. Significant reduction in MTHFR methylation was observed in TT adults following intervention with the enzyme co-factor riboflavin [11].

We identified 246 differentially methylated CpG sites which were associated with both SBP and DBP (Fig. 3A). Only three CpG sites were identified to be associated with SBP, DBP and HTN, which may be due to the paucity of epigenome-wide methylation studies investigating HTN as an outcome. Three additional CpG sites were reported in five publications (Table S4), including cg19693031 annotated to the gene TXNIP [23, 28, 91,92,93]. Overexpression of TXNIP has been associated with increased oxidative stress and excessive ROS [94]. Seven studies report 1,391 DMRs to be significantly associated with various BP traits, with 56 of these common to both SBP and DBP (Fig. 3B). Eight DMRs were reported in more than one publication (Table S5).

Network analysis of genes annotated from CpG sites highlighted a protein cluster significantly enriched in biological processes associated with circadian rhythm (Fig. 4). Variations in BP occur naturally with circadian rhythm, and polymorphisms in genes associated with these proteins have been associated with both circadian phenotype and myocardial infarction [95,96,97]. Interestingly, functional analysis of all CpGs associated with BP traits highlights chromatin as the most significantly enriched cellular component (PFDR = 1.59E-07) (Table S6) strengthening the evidence for the role of epigenetic modifications in HTN [97, 98].

Taken together, our results demonstrate that HTN is associated with accelerated epigenetic ageing indicating that EAA is higher in hypertensive individuals compared to normotensive individuals. The identification of robust biomarkers for accelerated epigenetic age in HTN patients may help cardiologists identify patients at greatest risk of complications and encourage lifestyle modifications such as exercise and targeted nutritional interventions. Further research is required to determine if EAA may be predictive of HTN outcomes or if measures to reduce EAA are useful in management of HTN.

Strengths and Limitations

This review critically investigates the association between epigenetic age and HTN and importantly, is the first to employ a systematic approach to identify the studies subjected to meta-analysis to ensure a robust overview of current evidence. The analysis was conducted in line with PRISMA guidelines with defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. We have outlined a comprehensive summary using a combination of quantitative and qualitative evidence for the role of DNA methylation in HTN and BP. Limitations of this study include any fixed exposures that may influence epigenetic age, such as age, sex or race, which were not considered due to the small number of studies available for meta-analysis, however, all included studies bar one, cofounded for age and sex as appropriate [83, 99]. Studies included within the meta-analysis were considered to be sufficiently homogenous for analysis, however due to the exploratory nature of combining multiple epigenetic clocks studies, heterogeneity was introduced in the combined estimate limiting the generalisability of findings and we suggest caution in the interpretation of the pooled estimate broad summary of the overall association between EAA and HTN rather than a definitive result. A further limitation is that most studies included within the meta-analysis were conducted in the USA, while the remaining studies were conducted in other predominantly white Caucasian populations such as the UK and Australia. Although, 5/8 of included studies cofounded for ethnicity as a covariate, only one cohort included only African American participants (n = 227), introducing potential population bias and limiting generalisation of findings to non-European populations. The majority of studies assessed DNA methylation in blood due to sample accessibility with lack of readily available cardiac tissue studies remaining a constraint. DNA methylation exhibits tissue-specificity, influenced by leukocyte composition [100,101,102,103,104,105]. A recently defined cardiac-specific epigenetic clock indicated, however, that both blood and cardiac tissue reflect chronological age, suggesting that blood is a suitable proxy for cardiac epigenetic age studies [106, 107]. Moreover, the epigenetic clock algorithms applied in included studies were trained on multiple tissue types, including blood, and have been demonstrated robust performance across different tissues [16,17,18,19].

Conclusion

This study is the first to demonstrate that HTN is associated with accelerated epigenetic ageing, by systematically evaluating the current evidence. There is need for further epigenome-wide approaches, and we recommend the use of clinically measured HTN over self-reported HTN in appropriately powered studies of epigenetic age to provide clarity on the relationship between environment, epigenome and HTN. The identification of robust biomarkers for accelerated epigenetic age in HTN patients may help clinicians identify patients at greatest risk of complications and encourage lifestyle modifications such as exercise and targeted nutritional interventions. In conclusion, accelerated epigenetic ageing as an underlying mechanism for hypertension holds much promise through the potential to impact development of novel therapeutic targets for HTN.

Data availability

All data used within this study were obtained from previously published articles and publicly available sources. Full details of data sources, including citations are available in the main text tables and supplementary materials. Readers may access the original datasets by referring to the cited publications.

Change history

20 January 2026

Author’s affiliation and Grant number have been updated.

References

Zhou B, Perel P, Mensah GA, Ezzati M. Global epidemiology, health burden and effective interventions for elevated blood pressure and hypertension. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021;18:785–802.

Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, Reed JE, Kearney PM, Reynolds K, et al. Global Disparities of Hypertension Prevalence and Control: A Systematic Analysis of Population-Based Studies From 90 Countries. Circulation. 2016;134:441–50.

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet 2021; 398(10304):957–80.

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Long-term and recent trends in hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in 12 high-income countries: an analysis of 123 nationally representative surveys. Lancet 2019; 394(10199):639–51.

Evangelou E, Warren HR, Mosen-Ansorena D, Mifsud B, Pazoki R, Gao H, et al. Genetic analysis of over 1 million people identifies 535 new loci associated with blood pressure traits. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1412–25.

Keaton JM, Kamali Z, Xie T, Vaez A, Williams A, Goleva SB, et al. Genome-wide analysis in over 1 million individuals of European ancestry yields improved polygenic risk scores for blood pressure traits. Nat Genet. 2024;56:778–91.

Warren HR, Evangelou E, Cabrera CP, Gao H, Ren M, Mifsud B, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies novel blood pressure loci and offers biological insights into cardiovascular risk. Nat Genet. 2017;49:403–15.

Gonzalez-Jaramillo V, Portilla-Fernandez E, Glisic M, Voortman T, Bramer W, Chowdhury R, et al. The role of DNA methylation and histone modifications in blood pressure: a systematic review. J Hum Hypertens. 2019;33:703–15.

Krolevets M, Cate VT, Prochaska JH, Schulz A, Rapp S, Tenzer S, et al. DNA methylation and cardiovascular disease in humans: a systematic review and database of known CpG methylation sites. Clin Epigenetics. 2023;15:56.

Muka T, Koromani F, Portilla E, O’Connor A, Bramer WM, Troup J, et al. The role of epigenetic modifications in cardiovascular disease: A systematic review. Int J Cardiol. 2016;212:174–83.

Amenyah SD, McMahon A, Ward M, Deane J, McNulty H, Hughes CF, et al. Riboflavin supplementation alters global and gene-specific DNA methylation in adults with the MTHFR 677 TT genotype. Biochimie. 2020;173:17–26.

Amenyah SD, Hughes CF, Ward M, Rosborough S, Deane J, Thursby SJ, et al. Influence of nutrients involved in one-carbon metabolism on DNA methylation in adults-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev. 2020;78:647–66.

Amenyah SD, Ward M, Strain JJ, McNulty H, Hughes CF, Dollin C, et al. Nutritional Epigenomics and Age-Related Disease. Curr Dev Nutr. 2020;4:nzaa097.

Amenyah SD, Ward M, McMahon A, Deane J, McNulty H, Hughes C, et al. DNA methylation of hypertension-related genes and effect of riboflavin supplementation in adults stratified by genotype for the MTHFR C677T polymorphism. Int J Cardiol. 2021;322:233–9.

Moqri M, Herzog C, Poganik JR. Biomarkers of aging for the identification and evaluation of longevity interventions. Cell. 2023;186:3758–75.

Hannum G, Guinney J, Zhao L, Zhang L, Hughes G, Sadda S, et al. Genome-wide methylation profiles reveal quantitative views of human aging rates. Mol Cell. 2013;49:359–67.

Horvath S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R115.

Levine ME, Lu AT, Quach A, Chen BH, Assimes TL, Bandinelli S, et al. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging (Albany NY). 2018;10:573–91.

Lu AT, Quach A, Wilson JG, Reiner AP, Aviv A, Raj K, et al. DNA methylation GrimAge strongly predicts lifespan and healthspan. Aging (Albany NY). 2019;11:303–27.

Marioni RE, Shah S, McRae AF, Chen BH, Colicino E, Harris SE, et al. DNA methylation age of blood predicts all-cause mortality in later life. Genome Biol. 2015;16:25.

Neytchev O, Erlandsson H, Witasp A, Nordfors L, Qureshi AR, Iseri K, et al. Epigenetic clocks indicate that kidney transplantation and not dialysis mitigate the effects of renal ageing. J Intern Med. 2024;295:79–90.

Ammous F, Zhao W, Ratliff SM, Mosley TH, Bielak LF, Zhou X, et al. Epigenetic age acceleration is associated with cardiometabolic risk factors and clinical cardiovascular disease risk scores in African Americans. Clin Epigenetics. 2021;13:55.

Horvath S, Gurven M, Levine ME, Trumble BC, Kaplan H, Allayee H, et al. An epigenetic clock analysis of race/ethnicity, sex, and coronary heart disease. Genome Biol. 2016;17:171.

Chilunga FP, Henneman P, Elliott HR, Cronjé HT, Walia GK, Meeks KAC, et al. Epigenetic-age acceleration in the emerging burden of cardiometabolic diseases among migrant and non-migrant African populations: a population-based cross-sectional RODAM study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021;2:e327–39.

Irvin MR, Aslibekyan S, Do A, Zhi D, Hidalgo B, Claas SA, et al. Metabolic and inflammatory biomarkers are associated with epigenetic aging acceleration estimates in the GOLDN study. Clin Epigenetics. 2018;10:56.

Alexeeff SE, Baccarelli AA, Halonen J, Coull BA, Wright RO, Tarantini L, et al. Association between blood pressure and DNA methylation of retrotransposons and pro-inflammatory genes. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:270–80.

Fernández-Sanlés A, Sayols-Baixeras S, Curcio S, Subirana I, Marrugat J, Elosua R. DNA Methylation and Age-Independent Cardiovascular Risk, an Epigenome-Wide Approach: The REGICOR Study (REgistre GIroní del COR). Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38:645–52.

Hong X, Miao K, Cao W, Lv J, Yu C, Huang T, et al. Association Between DNA Methylation and Blood Pressure: A 5-Year Longitudinal Twin Study. Hypertension. 2023;80:169–81.

Xu G, Wang Z, Li L, Li W, Hu J, Wang S, et al. Hypermethylation of dihydrofolate reductase promoter increases the risk of hypertension in Chinese. J Res Med Sci. 2020;25:117.

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:210.

Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3021–104.

Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71:1269–324.

Wells, G., Shea, B., Peterson, J., Welch, V., Losos, M., Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of non-randomised studies in meta-analyses. (2013) http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 30 October 2024.

Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer Program]. Version 5.4, The Cochrane Collaboration, (2020). Available at https://test-training.cochrane.org/online-learning/core-software-cochrane-reviews/review-manager-revman/download-revman-5.

Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor. J Stat Softw. 2010;36:1–48.

Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455–63.

Jensen LJ, Kuhn M, Stark M, Chaffron S, Creevey C, Muller J, et al. STRING 8-a global view on proteins and their functional interactions in 630 organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D412–6.

Sherman BT, Hao M, Qiu J, Jiao X, Baseler MW, Lane HC, et al. DAVID: a web server for functional enrichment analysis and functional annotation of gene lists (2021 update). Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50:W216–21.

Heberle H, Meirelles VG, da Silva FR, Telles GP, Minghim R. InteractiVenn: A web-based tool for the analysis of sets through Venn diagrams. BMC Bioinformatics. 2015;16:169.

Ehrlich M, Gama-Sosa MA, Huang LH, Midgett RM, Kuo KC, McCune RA, et al. Amount and distribution of 5-methylcytosine in human DNA from different types of tissues of cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;10:2709–21.

Weisenberger DJ, Campan M, Long TI, Kim M, Woods C, Fiala E, et al. Analysis of repetitive element DNA methylation by MethyLight. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:6823–36.

Ferrari L, Vicenzi M, Tarantini L, Barretta F, Sironi S, Baccarelli AA, et al. Effects of Physical Exercise on Endothelial Function and DNA Methylation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:2530.

Hossain K, Suzuki T, Hasibuzzaman MM, Islam MS, Rahman A, Paul SK, et al. Chronic exposure to arsenic, LINE-1 hypomethylation, and blood pressure: a cross-sectional study in Bangladesh. Environ Health. 2017;16:20.

Turcot V, Tchernof A, Deshaies Y, Pérusse L, Bélisle A, Marceau S, et al. LINE-1 methylation in visceral adipose tissue of severely obese individuals is associated with metabolic syndrome status and related phenotypes. Clin Epigenetics. 2012;4:10.

Baccarelli A, Wright R, Bollati V, Litonjua A, Zanobetti A, Tarantini L, et al. Ischemic heart disease and stroke in relation to blood DNA methylation. Epidemiology. 2010;21:819–28.

Thongsroy J, Patchsung M, Mutirangura A. The association between Alu hypomethylation and severity of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Epigenet. 2017;9:93.

Thongsroy J, Mutirangura A. The association between Alu hypomethylation and the severity of hypertension. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0270004.

Jiraboonsri S, Hemvipat P, Kamolratanakul S, Bhummaphan N, Siritientong T, Kitkumthorn N, et al. CpG methylation changes in Alu repetitive sequences in normal aging due to diastolic hypertension in human dermal fibroblasts from the facial area. Biomed Rep. 2023;20:5.

Smolarek I, Wyszko E, Barciszewska AM, Nowak S, Gawronska I, Jablecka A, et al. Global DNA methylation changes in blood of patients with essential hypertension. Med Sci Monit. 2010;16:CR149–155.

Yadav S, Longkumer I, Joshi S, Saraswathy KN. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene polymorphism, global DNA methylation and blood pressure: a population based study from North India. BMC Med Genomics. 2021;14:59.

Bellavia A, Urch B, Speck M, Brook RD, Scott JA, Albetti B, et al. DNA hypomethylation, ambient particulate matter, and increased blood pressure: findings from controlled human exposure experiments. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000212.

Carraro JC, Mansego ML, Milagro FI, Chaves LO, Vidigal FC, Bressan J, et al. LINE-1 and inflammatory gene methylation levels are early biomarkers of metabolic changes: association with adiposity. Biomarkers. 2016;21:625–32.

Li-Tempel T, Larra MF, Sandt E, Mériaux SB, Schote AB, Schächinger H, et al. The cardiovascular and hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis response to stress is controlled by glucocorticoid receptor sequence variants and promoter methylation. Clin Epigenetics. 2016;8:12.

Omar WFNW, Abdullah A, Talib NA, Shah ASM, Rahman JA. Leucocytic DNA Methylation of Interleukin-6 Promoter Reduction in Pre-Hypertensive Young Adults. Malays J Med Sci. 2019;26:46–54.

Huang JY, Gavin AR, Richardson TS, Rowhani-Rahbar A, Siscovick DS, Hochner H, et al. Accounting for Life-Course Exposures in Epigenetic Biomarker Association Studies: Early Life Socioeconomic Position, Candidate Gene DNA Methylation, and Adult Cardiometabolic Risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;184:520–31.

Fan R, Mao S, Zhong F, Gong M, Yin F, Hao L, et al. Association of AGTR1 Promoter Methylation Levels with Essential Hypertension Risk: A Matched Case-Control Study. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2015;147:95–102.

Li ZY, Ma Q, Li X, Yu SY, Zuo J, Wang CJ, et al. Association of AGTR1 gene methylation and its genetic variant in Chinese farmer with hypertension: A case-control study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e29712.

Lin J, Lin S, Wu Y, Wang X, Wu S, Li H. Hypomethylation of the Angiotensin II Type I Receptor (AGTR1) Gene Along with Environmental Factors Increases the Risk for Essential Hypertension. Cardiology. 2017;137:126–35.

Koochakkhani S, Nabizadeh F, Nejatizadeh A, Eftekhar E. Association of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) and cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) genes promoter methylation pattern with the risk of essential hypertension. Meta Gene. 2021;29:100914.

Wang C, Xu G, Wen Q, Peng X, Chen H, Zhang J, et al. CBS promoter hypermethylation increases the risk of hypertension and stroke. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2019;74:e630.

Bayoumy NMK, El-Shabrawi MM, Leheta OF, Omar HH. α-Adducin gene promoter DNA methylation and the risk of essential hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2017;39:764–8.

Zhang LN, Liu PP, Wang L, Yuan F, Xu L, Xin Y, et al. Lower ADD1 gene promoter DNA methylation increases the risk of essential hypertension. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63455.

Chiu MH, Chang CH, Tantoh DM, Hsu TW, Hsiao CH, Zhong JH, et al. Susceptibility to hypertension based on MTHFR rs1801133 single nucleotide polymorphism and MTHFR promoter methylation. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023;10:1159764.

Xu M, Li J, Chen X, Han L, Li L, Liu Y. MTHFD1 promoter hypermethylation increases the risk of hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2019;41:422–7.

Wan Z, Chibnik LB, Valeri L, Hughes TM, Blacker D, Ma Y. DNA Methylation Mediates the Association Between Cardiometabolic Risk Factors and Cognition: Findings From the Health and Retirement Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2024;79:glae167.

Tang B, Li X, Wang Y, Sjölander A, Johnell K, Thambisetty M, et al. Longitudinal associations between use of antihypertensive, antidiabetic, and lipid-lowering medications and biological aging. Geroscience. 2023;45:2065–78.

Tamman AJF, Montalvo-Ortiz JL, Southwick SM, Krystal JH, Levy BR, Pietrzak RH. Accelerated DNA Methylation Aging in U.S. Military Veterans: Results From the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27:528–32.

Gao X, Colicino E, Shen J, Just AC, Nwanaji-Enwerem JC, Wang C, et al. Accelerated DNA methylation age and the use of antihypertensive medication among older adults. Aging (Albany NY). 2018;10(11):3210–28.

Lind L, Ingelsson E, Sundström J, Siegbahn A, Lampa E. Methylation-based estimated biological age and cardiovascular disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 2018; 48).

Quach A, Levine ME, Tanaka T, Lu AT, Chen BH, Ferrucci L, et al. Epigenetic clock analysis of diet, exercise, education, and lifestyle factors. Aging (Albany NY). 2017;9:419–46.

Xiao L, Zan G, Liu C, Xu X, Li L, Chen X, et al. Associations Between Blood Pressure and Accelerated DNA Methylation Aging. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11:e022257.

Roberts JD, Vittinghoff E, Lu AT, Alonso A, Wang B, Sitlani CM, et al. Epigenetic Age and the Risk of Incident Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation. 2021;144:1899–911.

Smith JA, Raisky J, Ratliff SM, Liu J, Kardia SLR, Turner ST, et al. Intrinsic and extrinsic epigenetic age acceleration are associated with hypertensive target organ damage in older African Americans. BMC Med Genomics. 2019;12:141.

Föhr T, Hendrix A, Kankaanpää A, Laakkonen EK, Kujala U, Pietiläinen KH, et al. Metabolic syndrome and epigenetic aging: a twin study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2024;48:778–87.

Jiang R, Hauser ER, Kwee LC, Shah SH, Regan JA, Huebner JL, et al. The association of accelerated epigenetic age with all-cause mortality in cardiac catheterization patients as mediated by vascular and cardiometabolic outcomes. Clin Epigenetics. 2022;14:165.

Xia M, Li W, Lin H, Zeng H, Ma S, Wu Q, et al. DNA methylation age acceleration contributes to the development and prediction of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Geroscience. 2024;46:3525–42.

Robinson O, Chadeau Hyam M, Karaman I, Climaco Pinto R, Ala-Korpela M, Handakas E, et al. Determinants of accelerated metabolomic and epigenetic aging in a UK cohort. Aging Cell. 2020;19:e13149.

Roetker NS, Pankow JS, Bressler J, Morrison AC, Boerwinkle E. Prospective Study of Epigenetic Age Acceleration and Incidence of Cardiovascular Disease Outcomes in the ARIC Study (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities). Circ Genom Precis Med. 2018;11:e001937.

Wellman JL, Holmes B, Hill SY. Accuracy of self-reported hypertension: Effect of age, gender, and history of alcohol dependence. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2020;22:842–9.

McCartney DL, Stevenson AJ, Walker RM, Gibson J, Morris SW, Campbell A, et al. Investigating the relationship between DNA methylation age acceleration and risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement (Amst. 2018;10:429–37.

Liu Z, Leung D, Thrush K, Zhao W, Ratliff S, Tanaka T, et al. Underlying features of epigenetic aging clocks in vivo and in vitro. Aging Cell. 2020;19:e13229.

Kresovich JK, Sandler DP, Taylor JA. Methylation-Based Biological Age and Hypertension Prevalence and Incidence. Hypertension. 2023;80:1213–22.

Franceschi C, Garagnani P, Parini P, Giuliani C, Santoro A. Inflammaging: a new immune-metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2018;14:576–90.

Richard, Huan T MA, Ligthart S, Gondalia R, Jhun MA, Brody JA, et al. DNA Methylation Analysis Identifies Loci for Blood Pressure Regulation. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;101:888–902.

Pottinger TD, Khan SS, Zheng Y, Zhang W, Tindle HA, Allison M, et al. Association of cardiovascular health and epigenetic age acceleration. Clin Epigenetics. 2021;13:42.

Smith BH, Campbell H, Blackwood D, Connell J, Connor M, Deary IJ, et al. Generation Scotland: the Scottish Family Health Study; a new resource for researching genes and heritability. BMC Med Genet. 2006;7:74.

Smith BH, Campbell A, Linksted P, Fitzpatrick B, Jackson C, Kerr SM, et al. Cohort Profile: Generation Scotland: Scottish Family Health Study (GS:SFHS). The study, its participants and their potential for genetic research on health and illness. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:689–700.

Li X, Wu N, Ji H, Huang Y, Hu H, Li J, et al. A male-specific association between AGTR1 hypermethylation and coronary heart disease. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2020;20:31–6.

Sethupathy P, Borel C, Gagnebin M, Grant GR, Deutsch S, Elton TS, et al. Human microRNA-155 on chromosome 21 differentially interacts with its polymorphic target in the AGTR1 3’ untranslated region: a mechanism for functional single-nucleotide polymorphisms related to phenotypes. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:405–13.

Ward M, Hughes CF, Strain JJ, Reilly R, Cunningham C, Molloy AM, et al. Impact of the common MTHFR 677C→T polymorphism on blood pressure in adulthood and role of riboflavin in modifying the genetic risk of hypertension: evidence from the JINGO project. BMC Med. 2020;18:318.

Zhang X, Ammous F, Lin L, Ratliff SM, Ware EB, Faul JD, et al. The Interplay of Epigenetic, Genetic, and Traditional Risk Factors on Blood Pressure: Findings from the Health and Retirement Study. Genes (Basel). 2022;13:1959.

Kho M, Zhao W, Ratliff SM, Ammous F, Mosley TH, Shang L, et al. Epigenetic loci for blood pressure are associated with hypertensive target organ damage in older African Americans from the genetic epidemiology network of Arteriopathy (GENOA) study. BMC Med Genomics. 2020;13:131.

Nuotio ML, Pervjakova N, Joensuu A, Karhunen V, Hiekkalinna T, Milani L, et al. An epigenome-wide association study of metabolic syndrome and its components. Sci Rep. 2020;10:20567.

Shah A, Xia L, Goldberg H, Lee KW, Quaggin SE, Fantus IG. Thioredoxin-interacting protein mediates high glucose-induced reactive oxygen species generation by mitochondria and the NADPH oxidase, Nox4, in mesangial cells. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:6835–48.

Škrlec I, Milić J, Steiner R. The Impact of the Circadian Genes CLOCK and ARNTL on Myocardial Infarction. J Clin Med. 2020;9:484.

Škrlec I, Milić J, Heffer M, Wagner J, Peterlin B. Circadian clock genes and circadian phenotypes in patients with myocardial infarction. Adv Med Sci. 2019;64:224–9.

Smolensky MH, Hermida RC, Portaluppi F. Circadian mechanisms of 24-hour blood pressure regulation and patterning. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;33:4–16.

Choi JK. Contrasting chromatin organization of CpG islands and exons in the human genome. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R70.

Kankaanpää A, Tolvanen A, Saikkonen P, Heikkinen A, Laakkonen EK, Kaprio J, et al. Do Epigenetic Clocks Provide Explanations for Sex Differences in Life Span? A Cross-Sectional Twin Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2022;77:1898–906.

Accomando WP, Wiencke JK, Houseman EA, Nelson HH, Kelsey KT. Quantitative reconstruction of leukocyte subsets using DNA methylation. Genome Biol. 2014;15:R50.

Cappozzo A, McCrory C, Robinson O, Freni Sterrantino A, Sacerdote C, Krogh V, et al. A blood DNA methylation biomarker for predicting short-term risk of cardiovascular events. Clin Epigenetics. 2022;14:121.

Houseman EA, Accomando WP, Koestler DC, Christensen BC, Marsit CJ, Nelson HH, et al. DNA methylation arrays as surrogate measures of cell mixture distribution. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13:86.

Mirza-Schreiber N, Zech M, Wilson R, Brunet T, Wagner M, Jech R, et al. Blood DNA methylation provides an accurate biomarker of KMT2B-related dystonia and predicts onset. Brain. 2022;145:644–54.

Mongelli A, Panunzi S, Nesta M, Gottardi Zamperla M, Atlante S, Barbi V, et al. Distinguishable DNA methylation defines a cardiac-specific epigenetic clock. Clin Epigenetics. 2023;15:53.

Reinius LE, Acevedo N, Joerink M, Pershagen G, Dahlén SE, Greco D, et al. Differential DNA methylation in purified human blood cells: implications for cell lineage and studies on disease susceptibility. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41361.

Burghardt KJ, Pilsner JR, Bly MJ, Ellingrod VL. DNA methylation in schizophrenia subjects: gender and MTHFR 677C/T genotype differences. Epigenomics. 2012;4:261–8.

Moore LD, Le T, Fan G. DNA methylation and its basic function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:23–38.

Castellano-Castillo D, Moreno-Indias I, Sanchez-Alcoholado L, Ramos-Molina B, Alcaide-Torres J, Morcillo S, et al. Altered Adipose Tissue DNA Methylation Status in Metabolic Syndrome: Relationships Between Global DNA Methylation and Specific Methylation at Adipogenic, Lipid Metabolism and Inflammatory Candidate Genes and Metabolic Variables. J Clin Med. 2019;8:87.

Chen C, Zhou X, Jing J, Cheng J, Luo Y, Chen J, et al. Decreased LINE-1 methylation levels in aldosterone-producing adenoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:4104–11.

Childebayeva A, Harman T, Weinstein J, Goodrich JM, Dolinoy DC, Day TA, et al. DNA Methylation Changes Are Associated With an Incremental Ascent to High Altitude. Front Genet. 2019;10:1062.

Deng Q, Huang W, Peng C, Gao J, Li Z, Qiu X, et al. Genomic 5-mC contents in peripheral blood leukocytes were independent protective factors for coronary artery disease with a specific profile in different leukocyte subtypes. Clin Epigenetics. 2018;10:9.

Kim M, Long TI, Arakawa K, Wang R, Yu MC, Laird PW. DNA methylation as a biomarker for cardiovascular disease risk. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9692.

Luttmer R, Spijkerman AM, Kok RM, Jakobs C, Blom HJ, Serne EH, et al. Metabolic syndrome components are associated with DNA hypomethylation. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2013;7:e106–15.

Maghbooli Z, Larijani B, Emamgholipour S, Amini M, Keshtkar A, Pasalar P. Aberrant DNA methylation patterns in diabetic nephropathy. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2014;13:69.

Maghbooli Z, Hossein-nezhad A, Larijani B, Amini M, Keshtkar A. Global DNA methylation as a possible biomarker for diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2015;31:183–9.

Marques-Rocha JL, Milagro FI, Mansego ML, Mourão DM, Martínez JA, Bressan J. LINE-1 methylation is positively associated with healthier lifestyle but inversely related to body fat mass in healthy young individuals. Epigenetics. 2016;11:49–60.

Wei L, Liu S, Su Z, Cheng R, Bai X, Li X. LINE-1 hypomethylation is associated with the risk of coronary heart disease in Chinese population. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2014;102:481–8.

Wu Y, Cui W, Zhang D, Wu W, Yang Z. The shortening of leukocyte telomere length relates to DNA hypermethylation of LINE-1 in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Oncotarget. 2017;8:73964–73.

Abula G, Li J, Ma R, Zhang T, Aji A, Zhang Y. Serum Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Methylation Level and Its Significance in Patients With Comorbid Major Depressive Disorder and Hypertension. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2023. (e-pub ahead of print).

Ali MM, Naquiallah D, Qureshi M, Mirza MI, Hassan C, Masrur M, et al. DNA methylation profile of genes involved in inflammation and autoimmunity correlates with vascular function in morbidly obese adults. Epigenetics. 2022;17:93–109.

Baccarelli AA, Byun HM. Platelet mitochondrial DNA methylation: a potential new marker of cardiovascular disease. Clin Epigenetics. 2015;7:44.

Bai C, Su M, Zhang Y, Lin Y, Sun Y, Song L, et al. Oviductal Glycoprotein 1 Promotes Hypertension by Inducing Vascular Remodeling Through an Interaction With MYH9. Circulation. 2022;146:1367–82.

Bao XJ, Mao SQ, Gu TL, Zheng SY, Zhao JS, Zhang LN. Hypomethylation of the Interferon γ Gene as a Potential Risk Factor for Essential Hypertension: A Case-Control Study. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2018;244:283–90.

Bi L, Jin J, Fan Y, Liu Y, Xu H, Li M, et al. Blood-based HYAL2 methylation as a potential marker for the preclinical detection of coronary heart disease and stroke. Clin Epigenetics. 2024;16:130.

Breitling LP, Salzmann K, Rothenbacher D, Burwinkel B, Brenner H. Smoking, F2RL3 methylation, and prognosis in stable coronary heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2841–8.

Bushueva O, Barysheva E, Markov A, Belykh A, Koroleva I, Churkin E, et al. DNA Hypomethylation of the MPO Gene in Peripheral Blood Leukocytes Is Associated with Cerebral Stroke in the Acute Phase. J Mol Neurosci. 2021;71:1914–32.

Carraro JC, Hermsdorff HH, Mansego ML, Zulet MÁ, Milagro FI, Bressan J, et al. Higher Fruit Intake Is Related to TNF-α Hypomethylation and Better Glucose Tolerance in Healthy Subjects. J Nutrigenet Nutrigenomics. 2016;9:95–105.

Castellano-Castillo D, Moreno-Indias I, Fernández-García JC, Alcaide-Torres J, Moreno-Santos I, Ocaña L, et al. Adipose Tissue LPL Methylation is Associated with Triglyceride Concentrations in the Metabolic Syndrome. Clin Chem. 2018;64:210–8.

Chen YC, Huang KT, Su MC, Hsu PY, Chin CH, Lin IC, et al. Aberrant DNA methylation levels of the formyl peptide receptor 1/2/3 genes are associated with obstructive sleep apnea and its clinical phenotypes. Am J Transl Res. 2020;12:2521–37.

Chen YC, Liaw YC, Nfor ON, Hsiao CH, Zhong JH, Wu SL, et al. Epigenetic regulation of Parkinson’s disease risk variant GPNMB cg17274742 methylation by sex and exercise from Taiwan Biobank. Front Aging Neurosci. 2023;15:1235840.

Cordero P, Campion J, Milagro FI, Goyenechea E, Steemburgo T, Javierre BM, et al. Leptin and TNF-alpha promoter methylation levels measured by MSP could predict the response to a low-calorie diet. J Physiol Biochem. 2011;67:463–70.

Corsi S, Iodice S, Vigna L, Cayir A, Mathers JC, Bollati V, et al. Platelet mitochondrial DNA methylation predicts future cardiovascular outcome in adults with overweight and obesity. Clin Epigenetics. 2020;12:29.

Cortese R, Zhang C, Bao R, Andrade J, Khalyfa A, Mokhlesi B, et al. DNA Methylation Profiling of Blood Monocytes in Patients With Obesity Hypoventilation Syndrome: Effect of Positive Airway Pressure Treatment. Chest. 2016;150:91–101.

Diniz TG, Silva AS, Dos Santos Nunes MK, Ribeiro MD, Filho JM, do Nascimento RAF, et al. Physical Activity Level Influences MTHFR Gene Methylation Profile in Diabetic Patients. Front Physiol. 2021;11:618672.

Drake AJ, McPherson RC, Godfrey KM, Cooper C, Lillycrop KA, Hanson MA, et al. An unbalanced maternal diet in pregnancy associates with offspring epigenetic changes in genes controlling glucocorticoid action and foetal growth. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2012;77:808–15.

El Alami H, Ghazal H, Abidi O, Al Idrissi N, Allali M, Wakrim L, et al. Lack of association between methylation status of CpG in the MCP-1 promoter and type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications in a Moroccan population. Gene Reports. 2022;26:101523.

Fan R, Wang WJ, Zhong QL, Duan SW, Xu XT, Hao LM, et al. Aberrant methylation of the GCK gene body is associated with the risk of essential hypertension. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:2390–4.

Fan R, Mao SQ, Gu TL, Zhong FD, Gong ML, Hao LM, et al. Preliminary analysis of the association between methylation of the ACE2 promoter and essential hypertension. Mol Med Rep. 2017;15:3905–11.

Friso S, Pizzolo F, Choi SW, Guarini P, Castagna A, Ravagnani V, et al. Epigenetic control of 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 2 gene promoter is related to human hypertension. Atherosclerosis. 2008;199:323–7.

Gao J, Qiu X, Wang X, Peng C, Zheng F. Associations of ChREBP and Global DNA Methylation with Genetic and Environmental Factors in Chinese Healthy Adults. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157128.

Giannakopoulou E, Konstantinou F, Ragia G, Tavridou A, Karaglani M, Chatzaki E, et al. Epigenetics-by-Sex Interaction for Coronary Artery Disease Risk Conferred by the Cystathionine γ-Lyase Gene Promoter Methylation. OMICS. 2017;21:741–8.

Guay SP, Brisson D, Lamarche B, Biron S, Lescelleur O, Biertho L, et al. ADRB3 gene promoter DNA methylation in blood and visceral adipose tissue is associated with metabolic disturbances in men. Epigenomics. 2014;6:33–43.

Gu T, Mao S, Fan R, Zhong F, Zhu F, Hao L, et al. Interactions between CYP11B2 promoter methylation and smoking increase risk of essential hypertension. Biomed Research International. 2016;2016:1454186.

Jin F, Li X, Wang Z, Liu Y, Liu J, Sun D, et al. Association of mitofusin 2 methylation and essential hypertension: a case-control study in a Chinese population. Hypertens Res. 2018;41:605–13.

Jin J, Zhu C, Wang J, Zhao X, Yang R. The association between ACTB methylation in peripheral blood and coronary heart disease in a case-control study. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:972566.

Krishnan R, Mani P, Sivakumar P, Gopinath V, Sekar D. Expression and methylation of circulating microRNA-510 in essential hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2017;40:361–3.

Kou M, Li X, Shao X, Grundberg E, Wang X, Ma H, et al. DNA Methylation of Birthweight-Blood Pressure Genes and Changes of Blood Pressure in Response to Weight-Loss Diets in the POUNDS Lost Trial. Hypertension. 2023;80:1223–30.

Li J, Zhu J, Ren L, Ma S, Shen B, Yu J, et al. Association between NPPA promoter methylation and hypertension: results from Gusu cohort and replication in an independent sample. Clin Epigenetics. 2020;12:133.

Li, Zhang Y, Di Zhang Q, Cai Q, Fan J, Venners SA, et al. The effect of ABCA1 gene DNA methylation on blood pressure levels in a Chinese hyperlipidemic population. J Hum Hypertens. 2021;35:1139–48.

Li R, Song J, Zhao A, Diao X, Zhang T, Qi X, et al. Association of APP gene polymorphisms and promoter methylation with essential hypertension in Guizhou: a case-control study. Hum Genomics. 2023;17:25.

Lopez-Legarrea P, Mansego ML, Zulet MA, Martinez JA. SERPINE1, PAI-1 protein coding gene, methylation levels and epigenetic relationships with adiposity changes in obese subjects with metabolic syndrome features under dietary restriction. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2013;53:139–44.

Macías-González M, Martín-Núñez GM, Garrido-Sánchez L, García-Fuentes E, Tinahones FJ, Morcillo S. Decreased blood pressure is related to changes in NF-kB promoter methylation levels after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14:1327–34.

Mansouri E, Esmaeili F, Montaseri M, Emami MA, Koochakkhani S, Khayatian M, et al. Association of methylation status of ABCA1/G1 genes with the risk of coronary artery disease. Egypt. J. Med Hum Genet. 2022;23:167.

Mao S, Fan R, Gu T, Zhong Q, Gong M, Dong C, et al. Hypermethylation of SCNN1A gene-body increases the risk of essential hypertension. Int J Clin and Exp Pathol. 2016;9:8047–56.

Mao S, Gu T, Zhong F, Fan R, Zhu F, Ren P, et al. Hypomethylation of the Toll-like receptor-2 gene increases the risk of essential hypertension. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:964–70.

Mao SQ, Sun JH, Gu TL, Zhu FB, Yin FY, Zhang LN. Hypomethylation of interleukin-6 (IL-6) gene increases the risk of essential hypertension: a matched case-control study. J Hum Hypertens. 2017;31:530–6.

Marotta A, Noro F, Parisi R, Gialluisi A, Tirozzi A, De Curtis A, et al. NMU DNA methylation in blood is associated with metabolic and inflammatory indices: results from the Moli-sani study. Epigenetics. 2021;16:1347–60.

Meng L, Chen D, Pei F, Hui R, Zheng Y, Chen J. DNA methylation in the norepinephrine transporter gene promoter region is not associated with depression and hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2017;39:539–45.

Milagro FI, Campión J, Cordero P, Goyenechea E, Gómez-Uriz AM, Abete I, et al. A dual epigenomic approach for the search of obesity biomarkers: DNA methylation in relation to diet-induced weight loss. FASEB J. 2011;25:1378–89.

Milagro FI, Gómez-Abellán P, Campión J, Martínez JA, Ordovás JM, Garaulet M. CLOCK, PER2 and BMAL1 DNA methylation: association with obesity and metabolic syndrome characteristics and monounsaturated fat intake. Chronobiol Int. 2012;29:1180–94.

Mo XB, Zhang H, Wang AL, Xu T, Zhang YH. Integrative analysis identifies the association between CASZ1 methylation and ischemic stroke. Neurol Genet. 2020;6:e509.

Osum M, Tosun O, Birtan H, Kalkan R. Determination of the Relationship Between DNA Methylation Status of KLOTHO and ARNTL Genes With Hypertension. Balkan J Med Genet. 2024;26:41–50.

Peng P, Wang L, Yang X, Huang X, Ba Y, Chen X, et al. A preliminary study of the relationship between promoter methylation of the ABCG1, GALNT2 and HMGCR genes and coronary heart disease. PLoS One. 2014;9:e102265.

Roberts ML, Kotchen TA, Pan X, Li Y, Yang C, Liu P, et al. Unique Associations of DNA Methylation Regions With 24-Hour Blood Pressure Phenotypes in Black Participants. Hypertension. 2022;79:761–72.

Shi J, Wu L, Chen Y, Zhang M, Yu J, Ren L, et al. Association between CORIN methylation and hypertension in Chinese adults. Postgrad Med J. 2022; pmj-2022-141802.

Turcot V, Tchernof A, Deshaies Y, Pérusse L, Bélisle A, Marceau P, et al. Comparison of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 gene methylation levels between severely obese subjects with and without the metabolic syndrome. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2013;5:4.

Wang X, Chang X, Li J, Yin L, Sun K. DNA methylation of microRNA-375 in impaired glucose tolerance. Exp Ther Med. 2014;8:775–80.

Wang C, Xu G, Wen Q, Peng X, Chen H, Zhang J, et al. Significant Association of Methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 1 Promoter Hypomethylation with Stroke in a Chinese Population with Primary Hypertension. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2019;49:112–8.

Wang W, Yao J, Li W, Wu Y, Duan H, Xu C, et al. Epigenome-wide association study in Chinese monozygotic twins identifies DNA methylation loci associated with blood pressure. Clin Epigenetics. 2023;15:38.

Wei L, Xia H, Zhao Y, Zhang Z, Chen J. Predictors of white blood cell interleukin-6 DNA methylation levels in healthy subjects. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2016;9:22162–8.

Xu G, Wang C, Ying X, Kong F, Ji H, Zhao J, et al. Serine hydroxymethyltransferase 1 promoter hypermethylation increases the risk of essential hypertension. J Clin Lab Anal. 2019;33:e22712.

Xu S, Shi Q, Li B, Han L, Xu G, Peng X, et al. High MTHFR promoter methylation levels in men confer protection against ischemic stroke. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2020;20:477–86.

Xu B, Xu Z, Chen Y, Lu N, Shu Z, Tan X. Genetic and epigenetic associations of ANRIL with coronary artery disease and risk factors. BMC Med Genomics. 2021;14:240.

Xu Y, Wang Y, Jiang Y, Liu M, Zhong W, Ge Z, et al. Relationship between cognitive dysfunction and the promoter methylation of PER1 and CRY1 in patients with cerebral small vessel disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2023;15:1174541.

Yang XH, Cao RF, Yu Y, Sui M, Zhang T, Xu JY, et al. A study on the correlation between MTHFR promoter methylation and diabetic nephropathy. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8:4960–7.

Zhang Y, Kent JW 2nd, Lee A, Cerjak D, Ali O, et al. Fatty acid binding protein 3 (fabp3) is associated with insulin, lipids and cardiovascular phenotypes of the metabolic syndrome through epigenetic modifications in a Northern European family population. BMC Med Genomics. 2013;6:9.

Zhang H, Wang A, Xu T, Mo X, Zhang Y. Promoter DNA Methylation in GWAS-Identified Genes as Potential Functional Elements for Blood Pressure: An Observational and Mendelian Randomization Study. Front Genet. 2022;12:791146.

Zhong Q, Liu C, Fan R, Duan S, Xu X, Zhao J, et al. Association of SCNN1B promoter methylation with essential hypertension. Mol Med Rep. 2016;14:5422–8.

Boström AE, Mwinyi J, Voisin S, Wu W, Schultes B, Zhang K, et al. Longitudinal genome-wide methylation study of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients reveals novel CpG sites associated with essential hypertension. BMC Med Genomics. 2016;9:20.

Caspers M, Blocquiaux S, Charlier R, Lefevre J, De Bock K, Thomis M. Metabolic fitness in relation to genetic variation and leukocyte DNA methylation. Physiol Genomics. 2019;51:12–26.

Ciantar J, Marttila S, Rajić S, Kostiniuk D, Mishra PP, Lyytikäinen LP, et al. Identification and functional characterisation of DNA methylation differences between East- and West-originating Finns. Epigenetics. 2024;19:2397297.

Cronjé HT, Elliott HR, Nienaber-Rousseau C, Green FR, Schutte AE, Pieters M. Methylation vs. Protein Inflammatory Biomarkers and Their Associations With Cardiovascular Function. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1577.