Abstract

We aimed to evaluate the relationship between serum testosterone levels and kidney stone prevalence in men. We examined cross-sectional data from 3234 men who participated in a health examination (2010–2020). A full metabolic work-up, including serum testosterone levels, was performed. Combined ultrasonography with KUB radiography was used for stone detection. The participants’ median age and testosterone concentration were 53.0 years and 4.7 ng/mL, respectively. A total of 178 men had kidney stones. A cutoff value for determining the presence of kidney stones was a testosterone concentration <3.33 ng/mL ng/mL. After adjusting for confounders, only age and a testosterone concentration <3.33 ng/mL were significantly related to the presence of kidney stones. However, body mass index, blood pressure, triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, HbA1c, uric acid, hs-CRP, calcium, aspartate transaminase, alanine aminotransferase, and albumin were not significantly and independently related to kidney stones. The odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for kidney stones according to age and testosterone concentration <3.33 ng/mL were 1.029 (1.010–1.04) and 1.655 (1.071–2.556), respectively. Our study revealed that the prevalence of kidney stones significantly and independently increased when the serum testosterone was less than 3.33 ng/mL in men.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The prevalence of nephrolithiasis is increasing worldwide [1, 2], and the recurrence rate is close to 50% [3]. Additionally, urinary stones have a negative impact on quality of life and impose a significant economic burden on patients and health care systems. Considering the high prevalence, high recurrence rate, and economic burden of urinary stone disease, it is important to identify risk factors to understand the underlying pathophysiology and help prevent this disease.

Testosterone has been postulated to be a risk factor for urinary stones since the prevalence of stones is two to three times greater in men than in women [4, 5]. A previous clinical study showed that testosterone was greater in men with kidney stones than in healthy control participants [6] and that testosterone receptors were upregulated in the kidneys of patients with nephrolithiasis [6]. Recent laboratory data from rats also revealed that finasteride interferes with the crystal formation of calcium oxalate, the most common stone component [7].

However, data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) revealed no significant relationship between serum testosterone levels and a history of urinary stones [8]. Furthermore, serum testosterone levels were significantly inversely associated with the prevalence of nephrolithiasis in men over 40 years of age in another clinical study [9]. Therefore, there is still controversy concerning this issue.

Previous clinical studies are limited by small sample sizes (low statistical power) [6], the reliance on patient medical history information to define kidney stones (recall bias) [8, 9], and the inability to fully adjust for basic confounders such as age and obesity [6]. These limitations hamper the ability to elucidate the exact role of testosterone in urinary stones. Therefore, we conducted this study to address some of these limitations and to investigate whether serum testosterone levels vary according to the presence of nephrolithiasis.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Data on men who participated in health checkups at one university hospital in Seoul, South Korea, during the period from 2010 to 2020 were collected.

Anthropometric measurements (height and weight), blood pressure measurements, basic blood chemistry, and lipid profile analyses were included in the basic health screening. Serum uric acid, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), high-sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP), and testosterone were measured, and plain-film kidney–ureter–bladder radiography (KUB) and abdominal ultrasonography were performed. Serum was drawn between 7:00 and 9:00 AM after overnight fasting. Medical histories were collected by trained nurses.

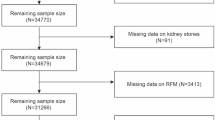

This study included men (aged ≥20 years) who simultaneously underwent blood collection, KUB testing, and ultrasound examination on the day of the basic health checkup. The exclusion criteria were as follows: patients who were receiving androgen replacement therapy (n = 15); participants who had any congenital renal deformities, polycystic kidney disease, dysgenesis or hypoplasia, renal cancer or renal tumor; or a kidney transplant (n = 2); and patients who were taking diuretics (n = 3). Finally, 3234 males were enrolled.

To evaluate the associations between serum testosterone levels and kidney stones, we examined the following variables: age, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, triglyceride (TG), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), creatinine (Cr), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), HbA1c, uric acid, hs-CRP, calcium, aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), albumin, testosterone and medical history.

Kidney stones

For stone detection, combined ultrasonography and KUB radiography was used. A comprehensive review of the literature showed that combining KUB with ultrasound improves the sensitivity compared to that of ultrasound alone, with estimates of sensitivity and specificity ranging from 58% to 100% and 37% to 100%, respectively [10].

KUB was taken immediately prior to ultrasonography, and investigators reviewed the KUB before performing ultrasonography. Nephrolithiasis was suspected when calcifications were identified along the anatomic course of the kidney on the KUB. The KUB was used to guide the radiologist to the area of suspected urinary calculi.

All of the ultrasonography examinations were performed by attending radiologists using an iU22 system (Philips Medical Systems, Amsterdam, Netherlands). B-mode ultrasonography was used to detect the stones by physically differentiating between stones and surrounding tissues. Bright echogenic structures with a nonechogenic shadow in the ultrasonographic image were considered to indicate nephrolithiasis. Small calculi (<3 mm) might not show acoustic shadowing. However, we did not include bright echogenic structures without a nonechogenic shadow in our definition of nephrolithiasis to ensure the inclusion of more clinically important renal stones [11]; this decision was made because in long-term follow-up studies, it has been reported that larger asymptomatic renal stones (>5 mm) are more likely to become symptomatic [12, 13].

Confounders

In previous studies, age [14], hypertension [14], BMI [14], dyslipidemia [15], renal function [16], uric acid [17], hs-CRP [18], HbA1c [19], and serum calcium [20, 21] were associated with urinary stones. Therefore, we adjusted for the aforementioned factors to elucidate the association between testosterone and nephrolithiasis.

Fatty liver disease is also a risk factor for nephrolithiasis. Accordingly, AST and ALT were adjusted as parameters of fatty liver disease in this analysis [22]. Additionally, high protein intake, which in turn increases serum albumin [23], is related to the development of nephrolithiasis [24]. Hence, the serum albumin level was adjusted as a parameter of high protein intake to elucidate the association between testosterone and nephrolithiasis.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Review Board of Nowon Eulji University Hospital reviewed and approved the study protocol (approval number: 2024-05-006). Participants voluntarily underwent health examinations at the health examination center and gave informed consent to the study. All authors confirmed that research involving human participants has been conducted ethically according to the principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsink.

Statistical analysis

The primary aim of our study was to elucidate the relationship between serum testosterone levels and nephrolithiasis. The demographics were assessed using descriptive statistics. The cutoff point for testosterone as a discriminator of the presence of kidney stones was determined using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, which enabled the calculation of the total area under the ROC curve and cutoff points with better sensitivity and specificity.

We used binary logistic regression to determine the associations between testosterone and nephrolithiasis before and after adjusting for all other variables. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated before and after adjusting for all confounders. All tests were 2-sided, with statistical significance set at P < 0.05. The R statistical package v.2.13.1 was used for analysis.

Results

A total of 178 men had kidney stones. The demographic data of the study participants are given in Table 1. The participants’ median age and testosterone concentration were 53.0 years (interquartile range: 45.0–62.0) and 4.7 ng/mL (interquartile range: 3.6–5.9), respectively. Table 2 lists the area under the ROC curve, significance levels (p values), cutoff values, sensitivity and specificity for testosterone as a discriminator of the presence of kidney stones. Testosterone showed a sensitivity of 24.7% and a specificity of 80.6% for determining the presence of kidney stones, with a cutoff value of 3.33 ng/mL.

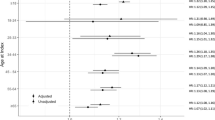

Before adjusting for confounders (Table 3), testosterone <3.33 ng/mL was not related to kidney stones, but age and LDL level were significantly related to kidney stones. However, after adjusting for confounders (Table 4), only age and testosterone concentration <3.33 ng/mL were significantly related to kidney stones. The OR (95% CI) for kidney stones with a testosterone concentration <3.33 ng/mL was 1.655 (1.071–2.556), which was greater than that for age (OR (95% CI): 1.029 (1.010–1.048)).

Discussion

In this study, low serum testosterone levels (<3.33 ng/mL) were significantly and independently related to kidney stones in men.

A retrospective cohort study from the U.S. showed that testosterone replacement in men with hypogonadism significantly increased the risk of urolithiasis [25]. In another retrospective case‒control study from Taiwan, androgen deprivation in prostate cancer patients reduced the subsequent development of kidney stones [26]. These two retrospective studies suggest that testosterone might induce urinary stones. However, these results are limited because the data are derived from military service members and individuals with pathological conditions such as prostate cancer. Therefore, these retrospective results might lack some degree of generalizability beyond former service members and patients with prostate cancer.

A small case‒control study from China [6] reported that total (13.29 ng/mL vs. 7.30 ng/mL; p<0.001) and free testosterone levels (63.23 ng/mL vs. 35.59 ng/mL; p<0.001) were greater in men with kidney stones (n = 37) than in healthy control participants (n = 31) (Table 5). Another small study from Iran showed that total testosterone (2.41 ng/mL vs. 3.30 ng/mL; p = 0.03) was greater in men with kidney stones (n = 40) than in healthy control participants (n = 46) (Table 5) [27]. Another small case–control study from India also revealed that serum testosterone levels were greater in men with kidney stones (n = 78) than in healthy control participants (n = 30) (4.36 vs. 5.52 ng/mL; p = 0.02) (Table 5) [28]. Another small case‒control study from the U.S., which included 30 patients and 25 control participants, reported that the total concentration (384 vs. 346 ng/dL, p = 0.112) was greater in men with kidney disease than in healthy control participants [29], although the difference was not statistically significant (Table 5). These data have shown that high serum testosterone levels may be a risk factor for urinary stones, but the results are limited by the small sample sizes of those studies.

In contrast to the aforementioned small case‒control series, the results from larger case‒control studies showed that low serum testosterone levels are a risk factor for urinary stones. A case‒control study in Turkey involving 313 men with urinary stones and 200 healthy control participants reported that [30] the serum testosterone level was lower in stone-forming patients than in control subjects, and the percentage of men with low serum testosterone (<285 ng/dL) was greater in men with urinary stones than in normal control participants (35.7% vs. 16.0%; p<00.1) (Table 5). In another case–control study in Turkey (200 patients and 168 control participants), testosterone deficiency was also more frequent in patients with urinary stone disease (OR = 2.38, p = 0.041) (Table 5) [31]. These results are in accordance with our results.

In terms of the use of big data from the NHANES, three articles were included, and the results were inconsistent across the studies. NHANES (2011–2012) [32] reported that men with lower testosterone levels (<3.0 ng/mL) were less likely to have kidney stones than men with normal testosterone levels (≥3.0 ng/mL) (OR: 0.59, 95% CI 0.40–0.86) (Table 5). However, according to other data from the NHANES (2013–2016) [8], low testosterone, defined as ≤300 ng/dL, was not associated with a history of kidney stones (Table 5). The most recent data from the NHANES (2011–2016) [9] revealed that serum testosterone levels were inversely associated with the prevalence of kidney stones in men older than 40 years, which is similar to our results (Table 5). The aforementioned three NHANES results are limited by sampling bias caused by incomplete response rates and recall bias resulting from defining urinary stones based on patient memory. Additionally, the authors used different criteria to classify participants according to testosterone level. We think that these factors underlie the inconsistency in the association between testosterone and nephrolithiasis in the literature.

LDL was significantly related to kidney stones according to the univariate model but was not related to the multivariate model in our study, which suggested the potential influence of other variables that may confound or interact with the relationship between LDL and kidney stones and indicated that the initial significant relationship observed in the bivariate analysis may be explained by the influence of other variables.

Previous results have shown that the cutoff values of testosterone for identifying hypogonadism vary according to symptoms, such as low libido (<2.30 ng/mL), erectile dysfunction (<2.45 ng/mL), and decreased morning erections (<3.17 ng/mL) [33, 34]. According to our statistical results, the cutoff value for indicating the presence of kidney stones was 3.33 ng/mL, with a testosterone concentration <3.33 ng/mL indicating a significantly greater risk of kidney stones. A testosterone concentration <3.33 ng/mL was associated with the highest OR in the multivariate model, indicating that it was the most powerful predictor in our data. Further research in other populations is needed to establish exact testosterone cutoff values for assessing the risk of urinary stone disease.

It is unclear why low testosterone levels are associated with the prevalence of kidney stones. It is difficult to investigate underlying mechanisms in cross-sectional studies. However, hypogonadism and urinary stones share the same risk behaviors, such as low water intake, low physical activity, and high protein intake (Fig. 1). It has been reported that those with inadequate water intake (less than 1000 mL a day) have a greater risk of developing urinary tract stones [35]. Additionally, plasma osmolarity was significantly and inversely associated with serum testosterone levels [36, 37]. Lower physical activity is associated with upper urinary tract calculi [38], and physical inactivity is also associated with low testosterone levels [39]. A high-protein diet increases the risk of both low testosterone and kidney stones [40].

A limitation of our study is that we used data from a single clinical health examination center in a single region. Additionally, we could not use the serum estrogen level as a variable due to a lack of data. However, we identified nephrolithiasis using imaging (no recall bias) and used a relatively large cohort; in addition, we adjusted for multiple confounders, including dyslipidemia, systemic inflammation, average blood sugar in the previous 3 months, uric acid level, age and obesity. Therefore, we believe that our data provide the most concrete evidence among the studies that attempted to elucidate the relationship between testosterone levels and nephrolithiasis.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study revealed that in males, the prevalence of kidney stones was significantly greater when the serum testosterone concentration was less than 3.33 ng/ml. We believe that further follow-up studies are warranted to determine whether low serum testosterone can cause urinary stones in long-term prospective cohort studies or whether testosterone replacement could reduce kidney stone risk in prospective observational studies or clinical trials.

Data availability

The raw/processed data required to reproduce the above findings cannot be shared at this time due to legal/ ethical reasons.

References

Romero V, Akpinar H, Assimos DG. Kidney stones: a global picture of prevalence, incidence, and associated risk factors. Rev Urol. 2010;12:e86–96.

Tae BS, Balpukov U, Cho SY, Jeong CW. Eleven-year cumulative incidence and estimated lifetime prevalence of urolithiasis in Korea: a national health insurance service-national sample cohort based study. J Korean Med Sci. 2018;33:e13. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2018.33.e13

Fink HA, Wilt TJ, Eidman KE, Garimella PS, MacDonald R, Rutks IR, et al. Medical management to prevent recurrent nephrolithiasis in adults: a systematic review for an American College of Physicians Clinical Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:535–43. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-7-201304020-00005

Alelign T, Petros B. Kidney stone disease: an update on current concepts. Adv Urol 2018;. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/3068365.

Scales CD Jr., Smith AC, Hanley JM, Saiga CS. Prevalence of kidney stones in the United States. Eur Urol. 2012;62:160–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2012.03.052

Li J-Y, Zhou T, Gao X, Xu C, Sun Y, Peng Y, et al. Testosterone and androgen receptor in human nephrolithiasis. J Urol. 2010;184:2360–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2010.08.009

Sueksakit K, Thongboonkerd V. Protective effects of finasteride against testosterone-induced calcium oxalate crystallization and crystal-cell adhesion. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2019;24:973–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00775-019-01692-z

Nackeeran S, Katz J, Ramasamy R, Marcovich R. Association between sex hormones and kidney stones: analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. World J Urol. 2021;39:1269–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-020-03286-w

Huang F, Li Y, Cui Y, Zhu Z, Chen J, Zeng F, et al. Relationship between serum testosterone levels and kidney stones prevalence in men. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:863675. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.863675

Fulgham PF, Assimos DG, Pearle MS, Preminger GM. Clinical effectiveness protocols for imaging in the management of ureteral calculous disease: AUA technology assessment. J Urol. 2013;189:1203–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2012.10.031

Mitterberger M, Pinggera GM, Pallwein L, Gradl J, Feuchtner G, Plattner R, et al. Plain abdominal radiography with transabdominal native tissue harmonic imaging ultrasonography vs unenhanced computed tomography in renal colic. BJU Int. 2007;100:887–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07048.x

Li X, Zhu W, Lam W, Yue Y, Duan H, Zeng G, et al. Outcomes of long-term follow-up of asymptomatic renal stones and prediction of stone-related events. BJU Int. 2019;123:485–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.14565

Brisbane W, Bailey MR, Sorensen MD. An overview of kidney stone imaging techniques. Nat Rev Urol. 2016;13:654–62. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrurol.2016.154

Khalili P, Jamali Z, Sadeghi T, Esmaeili-Nadimi A, Mohamadi M, Moghadam-Ahmadi A, et al. Risk factors of kidney stone disease: a cross-sectional study in the southeast of Iran. BMC Urol. 2021;21:141. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-021-00905-5

Torricelli FCM, De SK, Gebreselassie S, Li I, Sarkissian C, Monga M. Dyslipidemia and kidney stone risk. J Urol. 2014;191:667–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2013.09.022

Xu J-Z, Li C, Xia Q-D, Lu J-L, Wan Z-C, Hu L, et al. Sex disparities and the risk of urolithiasis: a large cross-sectional study. Ann Med. 2022;54:1627–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2022.2085882

Kim S-K. Interrelationship of uric acid, gout, and metabolic syndrome: Focus on hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and insulin resistance. J Rheum Dis. 2018;25:116–21.

Krolewski AS, Skupien J, Rossing P, Warram JH. Fast renal decline to end-stage renal disease: an unrecognized feature of nephropathy in diabetes. Kidney Int. 2017;91:1300–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2016.10.046

Almuhanna NR, Alhussain AM, Aldamanhori RB, Alabdullah QA. Association of chronic hyperglycemia with the risk of urolithiasis. Cureus. 2023;15:e47385. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.47385

Liu W, Wang M, Liu J, Yan Q, Liu M. Causal effects of modifiable risk factors on kidney stones: a bidirectional mendelian randomization study. BMC Med Genomics. 2023;16:82. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-023-01520-z

Craven BL, Passman C, Assimos DG. Hypercalcemic states associated with nephrolithiasis. Rev Urol. 2008;10:218–26.

Nam IC. Association of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with renal stone disease detected on computed tomography. Eur J Radiol Open. 2016;3:195–9.

Shirazian S, Grant CD, Aina O, Mattana J, Khorassani F, Ricardo AC. Depression in chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease: similarities and differences in diagnosis, epidemiology, and management. Kidney Int Rep. 2016;2:94–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2016.09.005

Remer T, Kalotai N, Amini AM, Lehmann A, Schmidt A, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al. Protein intake and risk of urolithiasis and kidney diseases: an umbrella review of systematic reviews for the evidence-based guideline of the German Nutrition Society. Eur J Nutr. 2023;62:1957–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-023-03143-7

McClintock TR, Valovska M-TI, Kwon NK, Cole AP, Jiang W, Kathrins MN, et al. Testosterone replacement therapy is associated with an increased risk of urolithiasis. World J Urol. 2019;37:2737–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-019-02726-6

Lin C-Y, Liu J-M, Wu C-T, Hsu R-J, Hsu W-L. Decreased risk of renal calculi in patients receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1762. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051762

Naghii MR, Babaei M, Hedayati M. Androgens involvement in the pathogenesis of renal stones formation. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93790. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0093790

Gupta K, Gill GS, Mahajan R. Possible role of elevated serum testosterone in pathogenesis of renal stone formation. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2016;6:241–4. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-516X.192593

Justin MW, Adam BS, Shaya T, Michael G, John GP, Chad WMR, et al. Serum testosterone may be associated with calcium oxalate urolithogenesis. J Endourol. 2010;24:1183–7. https://doi.org/10.1089/end.2010.0113

Alper O, Emin O, Suleyman SC, Murat D, Emre CP, Levent O, et al. Urolithiasis is associated with low serum testosterone levels in men. Arch Ital Urol Androl. 2015;87:83–86. https://doi.org/10.4081/aiua.2015.1.83

Emre CP, Oczan L, Octurntemur A, Ozbek E. Relation of urinary stone disease with androgenetic alopecia and serum testosterone levels. Urolithiasis. 2016;44:409–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00240-016-0888-3

Yucel E, DeSantis S, Smith MA, Lopez DS. Association between low-testosterone and kidney stones in US men: the national health and nutrition examination survey 2011–2012. Prev Med Rep. 2018;10:248.

Hackett G, Kirby M, Rees RW, Jones TH, Muneer A, Livingston M, et al. The British society for sexual medicine guidelines on male adult testosterone deficiency, with statements for practice. World J Mens Health. 2023;41:508–37.

Wu FCW, Tajar A, Beynon JM, Pye SR, Silman AJ, Finn JD, et al. Identification of late-onset hypogonadism in middle-aged and elderly men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:123–35.

Wu Y-C, Hou C-P, Weng S-C. Lifestyle and diet as risk factors for urinary stone formation: a study in a Taiwanese population. Medicina. 2023;59:1895.

Yildirim I. Associations among dehydration, testosterone and stress hormones in terms of body weight loss before competition. Am J Med Sci. 2015;350:103–8.

Hackett G, Mann A, Haider A, Haider KS, Desnerck P, König CS, et al. Testosterone replacement therapy: effects on blood pressure in hypogonadal men. World J Men Health. 2024;42:749–61.

Chen J-X, Yu X-X, Ye Y, Yang X-B, Tan A-H, Xian X-Y, et al. Association between recreational physical activity and the risk of upper urinary calculi. Urol Int. 2017;98:403–10. https://doi.org/10.1159/000452252

Cobo G, Gallar P, Gioia CD, Lacalle CG, Camacho R, Rodriguez I, et al. Hypogonadism associated with muscle atrophy, physical inactivity and ESA hyporesponsiveness in men undergoing haemodialysis. Nefrologia. 2017;37:54–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nefro.2016.04.009

Whittaker J. High-protein diets and testosterone. Nutr Health. 2023;29:185–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/02601060221132922

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our deepest appreciation to Seyoung Alexandra Lee from Rumsey Hall School for her contributions to the research.

Funding

This research was supported by EMBRI Grants 2022EMBRISN0005 from Eulji University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JHL, JYK, JDC and JBP were responsible for conceiving and designing the study, as well as writing the initial draft of the manuscript. JHL, JYK, JDC and JBP contributed to the study design and provided critical revisions to the manuscript. JYK, JHL, YK, ICC, JDC, TKY, DGL and JBP conducted the statistical analyses, created figures and tables, and contributed to the interpretation of the results. JHL, JYK, JDC and JBP offered valuable insights to the idea and project administration. JHL, JYK, JDC and JBP supervised the study, provided guidance throughout the research process, and approved the manuscript for publication. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kang, J.Y., Lee, J.H., Kwon, Y. et al. Older age and low testosterone levels are independently associated with kidney stone prevalence in men: results from a large cross-sectional study. Int J Impot Res 37, 668–673 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-025-01081-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-025-01081-y