Abstract

α-Chiral alkyne is a key structural element of many bioactive compounds, chemical probes, and functional materials, and is a valuable synthon in organic synthesis. Here we report a NiH-catalysed reductive migratory hydroalkynylation of olefins with bromoalkynes that delivers the corresponding benzylic alkynylation products in high yields with excellent regioselectivities. Catalytic enantioselective hydroalkynylation of styrenes has also been realized using a simple chiral PyrOx ligand. The obtained enantioenriched benzylic alkynes are versatile synthetic intermediates and can be readily transformed into synthetically useful chiral synthons.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

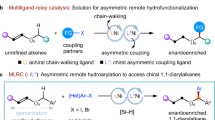

As a key structural element, chiral alkynes motifs bearing an α stereocentre are often found in many bioactive compounds, chemical probes, and functional materials (Fig. 1a). In addition, they are also valuable synthons as the sp3-hybridized carbons could undergo versatile transformations to deliver useful sp2- or sp3-hybridized carbons1. As a result, efficient strategies for catalytic, enantioselective C(sp3)–C(sp) coupling to generate such stereocentres have long been sought (Fig. 1b). For example, Liu2,3 reported an elegant work on Cu-catalyzed asymmetric Sonogashira C(sp3)–C(sp) coupling4,5. Shi6 and Liu7 have demonstrated that Pd- and Cu-catalyzed C(sp3)–H alkynylation could be achieved in an enantioselective fashion. Liu8 has also used an alkene difunctionalization strategy to produce enantioenriched alkynylation product under copper catalyst9. Suginome10 has reported a pioneering work on Ni-catalyzed asymmetric hydroalkynylation of 1,3-dienes based on their previous hydroalkynylation works11,12. As a continued development of general alternatives for asymmetric C(sp3)–C(sp) coupling, here we report an appealing approach via metal-hydride13,14,15 catalyzed asymmetric (remote) hydroalkynylation16 from readily available alkene starting materials.

Owing to its low-cost, facile oxidative addition, and availability of diverse oxidation states, nickel17,18 has emerged as a catalyst complementary to palladium over the past two decades, especially in cross-coupling reaction involving C(sp3) fragments. Reductive migratory hydrofunctionalization19,20,21,22 catalyzed by nickel hydride23,24,25 has recently been recognized as an alternative protocol for selective functionalization of remote C(sp3)–H bonds26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66. Compared to conventional cross-coupling, this process (i) employs readily available, bench-stable alkenes or alkene precursors instead of specially generated organometallic reagents as starting materials and (ii) could also selectively functionalize a remote C(sp3)–H site in addition to the conventional ipso-position. Since its conception, significant progress has been made toward this synthetically useful process26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61, which requires that the cross-coupling partner (e.g., aryl halide or alkyl halide) could selectively capture an alkylnickel species generated through iterative migratory insertion/β-hydride elimination.

To explore this nickel-catalyzed migratory hydrofunctionalization further, we recently investigated if a bromoalkyne, an unsaturated C(sp) cross-coupling partner which is potentially reactive toward NiH, could be used to achieve remote hydroalkynylation (Fig. 1c, i). Successful implementation of this transformation will require (i) a hydrometalation process that can discriminate between alkene and alkyne and (ii) an alkynylation process highly selective for one of the alkylnickel species. A chiral alkyne bearing an α-aryl-substituted stereogenic C(sp3) center2,3,4,5,7,8,9,10,67,68 would be ultimately obtained from styrene through hydronickellation and subsequent enantioconvergent52,53,55,56,69 alkynylation (Fig. 1c, ii). Here, we show the successful execution of this reaction.

Results

Reaction design and optimization

Our initial studies involved the migratory hydroalkynylation of 4-phenyl-1-butene (1a) using 1-bromo-2-(triisopropylsilyl)acetylene (2a) as an alkynylation reagent (Fig. 2). It was determined that NiI2·xH2O and the bathocuproine ligand (L) could generate the desired migratory alkynylation product as a single regioisomer [rr (benzylic product: all other isomers) > 99:1] in 82% yield (entry 1). Other nickel sources such as NiBr2 led to lower yields and a moderate rr (entry 2). Ligand screening revealed that the previously used ligand29, 6,6′-dimethyl-2,2′-bipyridine (L1) resulted in significantly lower yield and rr (entry 3) while a similar ligand neocuproine (L2) led to a similar regioselectivity but a lower yield (entry 4). Other silanes such as trimethoxysilane and diethoxymethylsilane gave diminished yields (entries 5 and 6), and marginally lower yield was obtained when reducing the amount of PMHS to 2.5 equiv (entry 7). K3PO4·H2O was shown to be an unsuitable base (entry 8). The addition of NaI as an additive improves both the yield and rr, presumably by promoting the regeneration of NiH species (entry 9). An evaluation of solvents revealed that THF was less effective than DME (entry 10), and conducting the reaction at 40 °C gave inferior results (entry 11).

*Yields determined by GC using n-dodecane as the internal standard, the yield in parentheses is the isolated yield. †rr refers to regioisomeric ratio, representing the ratio of the major product to the sum of all other isomers as determined by GC analysis. PMHS polymethylhydrosiloxane, DME dimethoxyethane, TIPS triisopropylsilyl.

Substrate scope

With these optimal reaction conditions, we examined the generality of the reaction. As shown in Fig. 3a, unactivated terminal alkenes bearing electron-donating (3c) or electron-withdrawing (3d–3g) substituents on the remote aryl ring are tolerated. A variety of functional groups are readily accommodated, including ethers (3c, 3h–3k, 3m), a trifluoromethyl group (3d), and esters (3g, 3i). Importantly, tosylates (3j) and triflate (3k) commonly used for further cross-coupling, all remained intact. The reaction could also proceed with olefin substrate having longer chain length between the starting C=C bond and the remote aryl group, producing the benzylic alkynylation product exclusively although with a lower yield (3l). Remarkably, both silyl and sterically hindered alkyl substituted ethynyl bromides work well in this reaction (3m, 3n). Moreover, a variety of unactivated internal alkenes also proved to be competent coupling partners, regardless of the E/Z configuration or the position of the C=C bond (Fig. 3b, 3o–3w). As expected, styrenes themselves smoothly undergo hydroalkynylation to produce the benzylic alkynylation product exclusively (Fig. 3c, 3x–3k′). Under these exceptionally mild reaction conditions, various substituents on the aryl ring (3z–3e′) as well as heteroaromatic styrenes (3f′, 3g′) were also suitable for this reaction.

Yield under each product refers to the isolated yield of purified product (0.20 mmol scale, average of two runs), rr refers to regioisomeric ratio, representing the ratio of the major product to the sum of all other isomers as determined by GC analysis. *Diglyme was used as solvent. †10 mol% NiI2·xH2O, 12 mol% L, and 20 mol% NaI were used. ‡DME (0.10 M) was used. TBS tert-butyldimethylsilyl, TBDPS tert-butyldiphenylsilyl; Tr trityl (triphenylmethyl).

In an effort to obtain enantioenriched benzylic alkynylation products, the asymmetric version of NiH-catalyzed hydroalkynylation of styrenes was explored and the results are in Fig. 4. It was found that a chiral PyrOx ligand (S)-L* under modified reaction conditions could produce the desired hydroalkynylation products in good yields and excellent ee. Styrenes with a variety of substituents on the aromatic ring underwent asymmetric hydroalkynylation smoothly (5a–5q), including ethers (5d–5i), an easily reduced aldehyde (5l), a nitrile (5m, 5n), and esters (5o–5q). Substituents commonly used for further cross-coupling such as aryl chloride (5c), aryl bromide (5k), and boronic acid pinacol ester (5j) all emerged unchanged. The substituents at β-position could also be varied (5r–5c′). Alkyl bromides were compatible with the current reaction, providing a synthetic handle for further derivatization (5y, 5z). β-Unsubstituted styrenes were also compatible (5d′, 5j′, 5k′). The scope of bromoalkynes was also explored and a range of different sterically hindered substituents at the β-position, including silyl and alkyl-substituted ethynyl bromides were shown to be viable substrates (5e′–5i′). However, it should also be noted that the less steric hindered alkyl-substituted ethynyl bromide (2l′) and aryl-substituted ethynyl bromide (2m′) were unsuccessful substrates70 and could easily undergo decomposition under the current conditions.

Yield under each product refers to the isolated yield of purified product (0.20 mmol scale, average of two runs), single regioisomer was obtained unless otherwise noted. Enantioselectivities were determined by chiral HPLC analysis. *NiBr2·diglyme used as catalyst, 1,2-dichloroethane used as solvent, 3.0 equiv NaI used. TES triethylsilyl.

Discussion

The asymmetric migratory hydroalkynylation could also be realized. In a preliminary experiment with 3-aryl-1-propene (1i) as substrate (Fig. 5a), chain-walking and subsequent asymmetric alkynylation at benzylic position product ((S)-3i) was obtained with excellent ee (90% ee) as major isomer (90:10 rr). When the reaction was conducted on a 5 mmol scale, the functionalized chiral benzylic alkyne (5e) was obtained in high yield and with excellent enantioselectivity (Fig. 5b). To highlight the synthetic utility of the method, subsequent derivatizations were carried out (Fig. 5c). Desilylation of 5e yielded the enantioenriched terminal alkyne (6), which could further undergo a click reaction to form 7 or a hydration reaction to form 8. The semi-hydrogenation of alkyne (5a) by DIBAL-H (diisobutylaluminum hydride) could be highly stereoselective, giving the Z-alkene (9). In addition, oxidative cleavage of the triple bond in 5e could afford the corresponding chiral carboxylic acid (10).

To gain further insight into the mechanism of the hydrometallation process, isotope labeling experiments were conducted. As shown in Fig. 5d, the use of the deuterated trans-alkene (E-4h-D) led to the formation of both diastereomers in approximately equal amounts (0.55:0.45 dr), which indicated that the syn-hydrometallation is not the enantio-determining step because if it was, a diastereomerically pure 5h-D should be formed. This observation is consistent with our initial mechanistic proposal that the benzylic stereocentre is formed through rapid homolysis of the alkyl-Ni(III) bond and subsequently enantioconvergent process, reforming only one Ni(III) enantiomer from Ni(II) and benzylic radical (see Fig. 1c, ii). Furthermore, no intermolecular H/D scrambled crossover products were obtained in both migratory and asymmetric hydroalkynylation conditions, revealing that hydrometallation of NiH/NiD species to styrene is irreversible (Fig. 5e).

In conclusion, we report a NiH-catalyzed strategy to form functionalized benzylic alkynylation products, which are versatile synthetic intermediates. Both migratory hydroalkynylation and asymmetric hydroalkynylation can be realized. These two mild, efficient, and straightforward processes tolerate a wide range of functional groups on both the alkene and bromoalkyne components. A broad substrate scope as well as synthetic utility of this protocol have been demonstrated. An investigation of the mechanism and the development of a migratory enantioselective version of this transformation are currently in progress.

Methods

NiH-catalyzed migratory hydroalkynylation of alkenes

In a nitrogen-filled glove box, to an oven-dried 8 mL screw-cap vial equipped with a magnetic stir bar were added NiI2·xH2O (3.8 mg, 5.0 mol%), L (4.3 mg, 6.0 mol%), Na2CO3 (42.4 mg, 2.0 equiv), NaI (3.0 mg, 10.0 mol%) and anhydrous DME (1.0 mL). The mixture was stirred for 20 min at room temperature (stirred at 800 rpm) before the addition of PMHS (60 μL, 1.0 mmol, 5.0 equiv). Stirring was continued for an additional 5 min before the addition of olefin 1 (0.20 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and bromoalkyne 2 (0.30 mmol, 1.5 equiv). The tube was sealed with a teflon-lined screw cap, removed from the glove box and the reaction was stirred at 25 °C for up to 16 h (the mixture was stirred at 1000 rpm). After the reaction was complete, the reaction was quenched upon the addition of H2O, and the mixture was extracted with EtOAc. The organic layer was concentrated to give the crude product. n-Dodecane (20 μL) was added as an internal standard for GC analysis. The product was purified by flash column chromatography (petroleum ether/EtOAc) for each substrate. See Supplementary Information for more detailed experimental procedures and characterization data for all products.

Enantioselective NiH-catalyzed hydroalkynylation of styenes

In a nitrogen-filled glove box, to an oven-dried 8 mL screw-cap vial equipped with a magnetic stir bar were added NiI2·xH2O (3.8 mg, 5.0 mol%), (S)-L* (3.3 mg, 6.0 mol%), K3PO4·H2O (115.1 mg, 2.5 equiv), NaI (60.0 mg, 2.0 equiv) and anhydrous PhCF3 (1.0 mL). The mixture was stirred for 20 min at room temperature (stirred at 800 rpm) before the addition of (MeO)3SiH (64 μL, 0.50 mmol, 2.5 equiv). Stirring was continued for an additional 5 min before the addition of olefin 4 (0.20 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and bromoalkyne 2 (0.30 mmol, 1.5 equiv). The tube was sealed with a teflon-lined screw cap, removed from the glove box and the reaction was stirred at 0 °C for up to 12 h (the mixture was stirred at 800 rpm). After the reaction was complete, the reaction was quenched upon the addition of H2O, and the mixture was extracted with EtOAc. The organic layer was concentrated to give the crude product. n-Dodecane (20 μL) was added as an internal standard for GC analysis. The product was purified by flash column chromatography (petroleum ether/EtOAc) for each substrate. The enantiomeric excesses (% ee) were determined by HPLC analysis using chiral stationary phases. See Supplementary Information for more detailed experimental procedures and characterization data for all products.

Data availability

The authors declare that the main data supporting the findings of this study, including experimental procedures and compound characterization, are available within the article and its supplementary information files, or from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Trost, B. M. & Li, C.-J. Modern Alkyne Chemistry: Catalytic and Atom-Economic Transformations (Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2015).

Dong, X.-Y. et al. A general asymmetric copper-catalysed Sonogashira C(sp3)–C(sp) coupling. Nat. Chem. 11, 1158–1166 (2019).

Xia, H.-D. et al. Photoinduced copper-catalyzed asymmetric decarboxylative alkynylation with terminal alkynes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 16926–16932 (2020).

Caeiro, J., Sestelo, J. P. & Sarandeses, L. A. Enantioselective nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of trialkynylindium reagents with racemic secondary benzyl bromides. Chemistry 14, 741–746 (2008).

Fang, H. et al. Transmetal-catalyzed enantioselective cross-coupling reaction of racemic secondary benzylic bromides with organoaluminum reagents. Org. Lett. 18, 6022–6025 (2016).

Han, Y.-Q. et al. Pd(II)-catalyzed enantioselective alkynylation of unbiased methylene C(sp3)–H bonds using 3,3′-fluorinated-BINOL as a chiral ligand. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 4558–4563 (2019).

Fu, L., Zhang, Z., Chen, P., Lin, Z. & Liu, G. Enantioselective copper-catalyzed alkynylation of benzylic C−H bonds via radical relay. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 12493–12500 (2020).

Fu, L., Zhou, S., Wan, X., Chen, P. & Liu, G. Enantioselective trifluoromethylalkynylation of alkenes via copper-catalyzed radical relay. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 10965–10969 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Copper-catalyzed photoinduced enantioselective dual carbofunctionalization of alkenes. Org. Lett. 22, 1490–1494 (2020).

Shirakura, M. & Suginome, M. Nickel-catalyzed asymmetric addition of alkyne C–H bonds across 1,3-dienes using taddol-based chiral phosphoramidite ligands. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 3827–3829 (2010).

Shirakura, M. & Suginome, M. Nickel-catalyzed regioselective hydroalkynylation of styrenes: improved catalyst system, reaction scope, and mechanism. Org. Lett. 11, 523–526 (2009).

Shirakura, M. & Suginome, M. Nickel-catalyzed, regio- and stereoselective hydroalkynylation of methylenecyclopropanes with retention of the cyclopropane ring, leading to the synthesis of 1-methyl-1-alkynylcyclopropanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 5060–5061 (2009).

Liu, R. Y. & Buchwald, S. L. CuH-Catalyzed olefin functionalization: from hydroamination to carbonyl addition. Acc. Chem. Res. 53, 1229–1243 (2020).

Eberhardt, N. A. & Guan, H. Nickel hydride complexes. Chem. Rev. 116, 8373–8426 (2016).

Chen, J., Guo, J. & Lu, Z. Recent advances in hydrometallation of alkenes and alkynes via the first row transition metal catalysis. Chin. J. Chem. 36, 1075–1109 (2018).

Zhang, W., Wang, Z., Bai, X. & Li, B. Substrate-directed catalytic asymmetric hydroalkynylation of alkenes. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 40, 1087–1095 (2020).

Tasker, S. Z., Standley, E. A. & Jamison, T. F. Recent advances in homogeneous nickel catalysis. Nature 509, 299–309 (2014).

Ogoshi, S. Nickel Catalysis in Organic Synthesis (Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2020).

Larionov, E., Li, H. & Mazet, C. Well-defined transition metal hydrides in catalytic isomerizations. Chem. Commun. 50, 9816–9826 (2014).

Vasseur, A., Bruffaerts, J. & Marek, I. Remote functionalization through alkene isomerization. Nat. Chem. 8, 209–219 (2016).

Sommer, H., Juliá-Hernández, F., Martin, R. & Marek, I. Walking metals for remote functionalization. ACS Cent. Sci. 4, 153–165 (2018).

Janssen-Müller, D., Sahoo, B., Sun, S.-Z. & Martin, R. Tackling remote sp3 C−H functionalization via Ni-catalyzed “chain-walking” reactions. Isr. J. Chem. 60, 195–206 (2020).

Cornella, J., Gómez-Bengoa, E. & Martin, R. Combined experimental and theoretical study on the reductive cleavage of inert C–O bonds with silanes: ruling out a classical Ni(0)/Ni(II) catalytic couple and evidence for Ni(I) intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 1997–2009 (2013).

Pappas, I., Treacy, S. & Chirik, P. J. Alkene hydrosilylation using tertiary silanes with α-diimine nickel catalysts redox-active ligands promote a distinct mechanistic pathway from platinum catalysts. ACS Catal. 6, 4105–4109 (2016).

Kuang, Y. et al. Ni(I)-catalyzed reductive cyclization of 1,6-dienes: mechanism-controlled trans selectivity. Chem 3, 268–280 (2017).

Busolv, I., Becouse, J., Mazza, S., Montandon-Clerc, M. & Hu, X. Chemoselective alkene hydrosilylation catalyzed by nickel pincer complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 14523–14526 (2015).

Lu, X. et al. Practical carbon–carbon bond formation from olefins through nickel-catalyzed reductive olefin hydrocarbonation. Nat. Commun. 7, 11129–11136 (2016).

Green, S. A., Matos, J. L. M., Yagi, A. & Shenvi, R. A. Branch-selective hydroarylation: iodoarene-olefin cross-coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 12779–12782 (2016).

He, Y., Cai, Y. & Zhu, S. Mild and regioselective benzylic C–H functionalization: Ni-catalyzed reductive arylation of remote and proximal olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 1061–1064 (2017).

Juliá-Hernández, F., Moragas, T., Cornella, J. & Martin, R. Remote carboxylation of halogenated aliphatic hydrocarbons with carbon dioxide. Nature 545, 84–88 (2017).

Gaydou, M., Moragas, T., Juliá-Hernández, F. & Martin, R. Site-selective catalytic carboxylation of unsaturated hydrocarbons with CO2 and water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 12161–12164 (2017).

Chen, F. et al. Remote migratory cross-electrophile coupling and olefin hydroarylation reactions enabled by in situ generation of NiH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 13929–13935 (2017).

Zhou, F., Zhu, J., Zhang, Y. & Zhu, S. NiH-catalyzed reductive relay hydroalkylation: a strategy for the remote C(sp3)–H alkylation of alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 4058–4062 (2018).

Xiao, J., He, Y., Ye, F. & Zhu, S. Remote sp3 C–H amination of alkenes with nitroarenes. Chem 4, 1645–1657 (2018).

Sun, S.-Z., Börjesson, M., Martin-Montero, R. & Martin, R. Site-selective Ni-catalyzed reductive coupling of α-haloboranes with unactivated olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 12765–12769 (2018).

Zhang, Y., Xu, X. & Zhu, S. Nickel-catalysed selective migratory hydrothiolation of alkenes and alkynes with thiols. Nat. Commun. 10, 1752 (2019).

Zhou, L., Zhu, C., Bi, P. & Feng, C. Ni-catalyzed migratory fluoro-alkenylation of unactivated alkyl bromides with gem-difluoroalkenes. Chem. Sci. 10, 1144–1149 (2019).

Bera, S. & Hu, X. Nickel-catalyzed Regioselective hydroalkylation and hydroarylation of alkenyl boronic esters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 13854–13859 (2019).

Zhang, Y., Han, B. & Zhu, S. Rapid access to highly functionalized alkylboronates via NiH-catalyzed remote hydroarylation of boron-containing alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 13860–13864 (2019).

Sun, S.-Z., Romano, C. & Martin, R. Site-selective catalytic deaminative alkylation of unactivated olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 16197–16201 (2019).

Qian, C. & Tang, W. NiH-catalyzed migratory defluorinative olefin cross-coupling: trifluoromethyl-substituted alkenes as acceptor olefins to form gem-difluoroalkenes. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 40, 1076–1077 (2020).

Gao, Y. et al. Visible-light-induced nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling with alkylzirconocenes from unactivated alkenes. Chem 6, 675–688 (2020).

Kumar, G. S. et al. Nickel-catalyzed chain-walking cross-electrophile coupling of alkyl and aryl halides and olefin hydroarylation enabled by electrochemical reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 6513–6519 (2020).

Jiao, K.-J. et al. Nickel-catalyzed electrochemical reductive relay cross-coupling of alkyl halides to aryl halides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 6520–6524 (2020).

Zhang, Y., He, J., Song, P., Wang, Y. & Zhu, S. Ligand-enabled NiH-catalyzed migratory hydroamination: chain walking as a strategy for regiodivergent/regioconvergent remote sp3 C–H amination. CCS Chem. 2, 2259–2268 (2020).

Jeon, J., Lee, C., Seo, H. & Hong, S. NiH-Catalyzed proximal-selective hydroamination of unactivated alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 20470–20480 (2020).

Wang, Z., Yin, H. & Fu, G. C. Catalytic enantioconvergent coupling of secondary and tertiary electrophiles with olefins. Nature 563, 379–383 (2018).

Zhou, F., Zhang, Y., Xu, X. & Zhu, S. NiH-catalyzed remote asymmetric hydroalkylation of alkenes with racemic α-bromo amides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 1754–1758 (2019).

He, S.-J. et al. Nickel-catalyzed enantioconvergent reductive hydroalkylation of olefins with α-heteroatom phosphorus or sulfur alkyl electrophiles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 214–221 (2020).

Yang, Z.-P. & Fu, G. C. Convergent catalytic asymmetric synthesis of esters of chiral dialkyl carbinols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 5870–5875 (2020).

Bera, S., Mao, R. & Hu, X. Enantioselective C(sp3)–C(sp3) cross-coupling of non-activated alkyl electrophiles via nickel hydride catalysis. Nat. Chem. 13, 270–277 (2021).

He, Y., Liu, C., Yu, L. & Zhu, S. Enantio- and regioselective NiH-catalyzed reductive hydroarylation of vinylarenes with aryl iodides Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 21530–21534 (2020).

Liu, J., Gong, H. & Zhu, S. Nickel-catalyzed, regio- and enantioselective benzylic alkenylation of olefins with alkenyl bromide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 4060–4064 (2021).

Shi, L., Xing, L.-L., Hu, W.-B. & Shu, W. Regio- and enantioselective Ni-catalyzed formal hydroalkylation, hydrobenzylation and hydropropargylation of acrylamides to α-tertiary amides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 1599–1604 (2021).

Cuesta-Galisteo, S., Schörgenhumer, J., Wei, X., Merino, E. & Nevado, C. Nickel-catalyzed asymmetric synthesis of α-arylbenzamides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 1605–1609 (2021).

He, Y., Song, H. & Zhu, S. NiH-Catalyzed asymmetric hydroarylation of N-acyl enamines: Practical access to chiral benzylamines. Nat. Commun. 12, 638 (2021).

Qian, D., Bera, S. & Hu, X. Chiral alkyl amine synthesis via catalytic enantioselective hydroalkylation of enecarbamates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 1959–1967 (2021).

Wang, J.-W. et al. Catalytic asymmetric reductive hydroalkylation of enamides and enecarbamates to chiral aliphatic amines. Nat. Commun. 12, 1313 (2021).

Wang, X.-X. et al. NiH-Catalyzed reductive hydrocarbonation of enol esters and ethers. CCS Chem. 3, 727–737 (2021).

Wang, S. et al. Enantioselective access to chiral aliphatic amines and alcohols via Ni-catalyzed hydroalkylations. Nat. Commun. 12, 2771 (2021).

Zhou, F. & Zhu, S. Enantioselective hydroalkylation of α,β-unsaturated amides through reversed syn-hydrometallation of NiH. ChemRxiv https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv.13681579.v1 (2021).

Lv, X.-Y., Fan, C., Xiao, L.-J., Xie, J.-H. & Zhou, Q.-L. Ligand-enabled Ni-catalyzed enantioselective hydroarylation of styrenes and 1,3-dienes with arylboronic acids. CCS Chem. 1, 328–334 (2019).

Chen, Y.-G. et al. Nickel-catalyzed enantioselective hydroarylation and hydroalkenylation of styrenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 3395–3399 (2019).

Zhang, W.-B., Yang, X.-T., Ma, J.-B., Su, Z.-M. & Shi, S.-L. Regio- and enantioselective C–H cyclization of pyridines with alkenes enabled by a nickel/N-heterocyclic carbene catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 5628–5634 (2019).

He, Y., Liu, C., Yu, L. & Zhu, S. Ligand-enabled nickel-catalyzed redox-relay migratory hydroarylation of alkenes with arylborons. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 9186–9191 (2020).

Yu, R., Rajasekar, S. & Fang, X. Enantioselective nickel-catalyzed migratory hydrocyanation of nonconjugated dienes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 21436–21441 (2020).

Schley, N. D. & Fu, G. C. Nickel-catalyzed Negishi arylations of propargylic bromides: a mechanistic investigation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 16588–16593 (2014).

Zhu, F.-L. et al. Enantioselective copper-catalyzed decarboxylative propargylic alkylation of propargyl β-ketoesters with a chiral ketimine P,N,N-ligand. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 1410–1414 (2014).

Gutierrez, O., Tellis, J. C., Primer, D. N., Molander, G. A. & Kozlowski, M. C. Nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling of photoredox-generated radicals: uncovering a general manifold for stereoconvergence in nickel-catalyzed cross-couplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 4896–4899 (2015).

Ziadi, A., Correa, A. & Martin, R. Formal γ-alkynylation of ketones via Pd-catalyzed C–C cleavage. Chem. Commun. 49, 4286–4288 (2013).

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by NSFC (21822105, 21772087), NSF of Jiangsu Province (BK20190281, BK20201245), Six Kinds of Talents Project of Jiangsu Province (JNHB-003), programs for high-level entrepreneurial and innovative talents introduction of Jiangsu Province (group program), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (020514380263).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.J., Y.W., and S.Z. designed the project. X.J., B.H., Y.X., M.D., Z.G., Y.W., and S.Z. co-wrote the manuscript, analyzed the data, discussed the results, and commented on the manuscript. X.J., B.H., Y.X., M.D., and Z.G. performed the experiments. All authors contributed to discussions.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare the following competing interest(s): a patent for the synthesis of AMG 837 using this method has been filed.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, X., Han, B., Xue, Y. et al. Nickel-catalysed migratory hydroalkynylation and enantioselective hydroalkynylation of olefins with bromoalkynes. Nat Commun 12, 3792 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24094-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24094-9

This article is cited by

-

Stereodivergent construction of non-adjacent stereocentres via migratory functionalization of alkenes

Nature Chemistry (2025)

-

Rapid assembly of enantioenriched α-arylated ketones via Ni-catalyzed asymmetric cross-hydrocarbonylation enabled by alkene sorting

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Recent Progress in NiH-Catalyzed Linear or Branch Hydrofunctionalization of Terminal or Internal Alkenes

Topics in Current Chemistry (2023)

-

Enantioselective synthesis of α-aminoboronates by NiH-catalysed asymmetric hydroamidation of alkenyl boronates

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Stereoselective synthesis through remote functionalization

Nature Synthesis (2022)