Abstract

Fluoroform (CF3H) is the simplest reagent for nucleophilic trifluoromethylation intermediated by trifluoromethyl anion (CF3–). However, it has been well-known that CF3– should be generated in presence of a stabilizer or reaction partner (in-situ method) due to its short lifetime, which results in the fundamental limitation on its synthetic utilization. We herein report a bare CF3– can be ex-situ generated and directly used for the synthesis of diverse trifluoromethylated compounds in a devised flow dissolver for rapid biphasic mixing of gaseous CF3H and liquid reagents that was designed and structurally optimized by computational fluid dynamics (CFD). In flow, various substrates including multi-functional compounds were chemoselectively reacted with CF3–, extending to the multi-gram-scale synthesis of valuable compounds by 1-hour operation of the integrated flow system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The trifluoromethyl (CF3) group has been recognized as an important functional group in medicinal chemistry because it can improve the therapeutic efficacy, permeability, metabolic stability of drug molecules, and the binding affinity against proteins1,2. Among the extensive synthetic strategies for introducing the CF3 group, various synthetic methodologies for nucleophilic trifluoromethylation have been developed3,4,5,6 but there is no better way to directly use fluoroform (CF3H) as the simplest precursor of the CF3 group in the viewpoint of atom- and step-economy7. Also, the utilization of CF3H has attracted from the standpoint of green-sustainable synthesis because CF3H is designated as a greenhouse gas (a lifetime of 270 years)8. Although pioneer works to directly exploit CF3H for the nucleophilic trifluoromethylation were achieved by Prakash’s group and several research groups9,10,11,12, the synthetic utility of CF3H still remains limited because of difficult handling the gaseous CF3H and its low reactivity. Above all, the reaction intermediate of the nucleophilic trifluoromethylation, CF3 anion (CF3−) rapidly decomposes into difluorocarbene (:CF2) and fluorine ion, as well-documented (Fig. 1a). To avoid these issues on directly using CF3H gas with vulnerable decomposition of CF3− intermediate even at cryogenic temperatures, the researchers have chosen indirect methods by using the stabilizing additives of CF3 anion13,14,15,16,17,18,19 such as Ruppert-Prakash reagent20, or by generating the hemiaminolate adduct [Me2NCH(O)CF3]K9 or coordinate metal cation21,22 in DMF or glyme solvent. However, the stabilization method cannot guarantee the use of unstable CF3− intermediate, because (1) the stabilized CF3- narrowed down their reaction scope due to the less reactivity; (2) its lifetime is still too short to secure the availability. Although CF3 anion is also found to be not a transient species but possess a lifetime by using additive, 18-crown-623, this reaction performance cannot be easily utilized in synthetic method due to too low reaction yield and the productivity. To redeem the problems, another indirect method to generate the unstable intermediate in the co-existence of reaction partner (i.e., in situ quenching method or in situ method)24,25 is applied as an only alternative to utilize short-lived CF3− from CF3H prior to the undesired decomposition (Fig. 1b)12. Nevertheless, this in situ quenching method approaches could not be completely evitable even in the use of additional reagents for stabilization of CF3−9,21,26 and/or the utilization of flow reaction setup for easy handling the gas with high pressure to prevent gas volatilization27,28,29,30,31. This method, however, has fatal problems of not only narrowing down the scope of reaction and the selectivity when the reaction partner is irreconcilable with reaction condition for generating the desired intermediate but also completely depriving the opportunity to explore the nature of a given intermediate for fully understanding a synthetic pathway because the intermediate cannot be solely existed (Fig. 1b)32. The large-scale synthesis including gas-liquid reaction is not easily achieved through in situ quenching method as well, because a large quantity of gas should be dissolved in the same solvent with other reactants. Also, most reported works of in situ quenching method required a long reaction time of as few minutes or as many hours as possible even at above room temperature. To overcome the critical limitation and preserve an original strong reactivity of the unstable intermediate, CF3− should be formed in the absence of any reaction partner or stabilizing reagent, prior to its following reaction (ex situ quenching method or ex situ method). However, this approach has not been applicable in the generation of CF3− from CF3H because it is challenging to achieve both fast biphasic mixing of gaseous CF3H with liquid deprotonating reagent within the short lifetime of CF3− and precise time control for external trapping reaction with generated CF3− even using flow-type reactors that is well-known to afford rapid mixing efficacy unachievable in flask33,34,35. We envisaged that this longstanding fundamental problem can be solved by a precise screening of reagents and reaction conditions using a well-designed flow dissolver based on the computer simulation.

a A challenge of direct trifluoromethylation using CF3− from CF3H. b An in situ quenching method with less-reactive substrates (reported work) and limitations the of in situ quenching method. c An ex situ generation of bare CF3− from CF3H using LICKOR type of superbase via fast gas-liquid mixing in flow (this work).

Here, we report a strategy to generate and utilize the short-lived CF3− intermediate from stable CF3H gas under ex situ method using LICKOR type superbase via fast biphasic mixing in precisely customized flow dissolvers (Fig. 1c). The method allows us not only to reveal accurate information on the lifetime and stability of CF3− but also to conduct the chemoselective reaction with various substrates by addressing a fundamental obstacle with the in situ method.

Results and discussion

Gas-liquid flow devices for rapid biphasic mixing

We initially considered using a simple tubing flow reactor or a tube-in-tube microfluidic reactor well used for gas-liquid flow reactions earlier36,37,38. However, both are not appropriate for rapid gas-liquid biphasic mixing and generation/reaction time control of CF3− due to low mixing efficiency, which makes it difficult to precisely control the residence time for CF3−. Therefore, it was necessary to devise a new flow dissolver that satisfies the purpose to handle the bare CF3− at our will. Based on the fact that efficient biphasic mixing for rapid dissolution can be achieved by a large contact area between gas and liquid with a smaller size gas bubble39, we conceptually designed various flow channel structured dissolvers composed of highly permeable nano-porous membrane sandwiched between upper and lower channels with staggered baffle structure. The baffle structured channels induced chaotic advection involving rapid distortion of the fluid interface35 when the gas-liquid mixture flows over the upper and the lower channels, while the nano-porous membrane in the middle acted as a static mixer and bubble breaker by preventing coalescence of gas segments which must severely reduce the contact area (Fig. 2a)40,41. On the basis of computational fluid dynamics (CFD)42, these structures were evaluated by monitoring the interfacial contact areas as iso-surface between gas and liquid in the vortex mixing space with excluding dead volume area (see description of definition of contact area between gas and liquid in the Supplementary Information for details). First of all, upon investigating the geometrical effect of baffle structure (see description of BS-1 to BS-7 in the Supplementary Information), the iso-surface was generally increased as the distance of the structure becomes smaller with the increased number of baffles but decreased for the structures smaller than 2.0 mm due to the increased effect of dead volume43. In addition, the height of the baffle also largely affected the iso-surface, indicating that the asymmetrically staggered structure in different heights (1000 and 300 μm of BS-4) gave the superior iso-surface to the others (Supplementary Tables 2 and 4). Consecutively, the effect of membrane porosity and thickness on the BS-4 structure was further tuned (see description of PM-1 to PM-6 in the Supplementary Information) to maximize the interfacial contact area between gas and liquid, over the absence of membrane (Supplementary Tables 3 and 5). In general, the thicker membrane, the smaller pore size, and the more decreased overall porosity lowered the iso-surface, presumably due to the decreased permeability of the gas and liquid. Eventually, the numerical simulation results showed that the asymmetrically staggered baffle structure BS-4 (1000 and 300 μm height, 2.0 mm distance), including 50 μm thickness of the membrane (PM-1) with appropriate pore characteristics (77% porosity and 820 nm pore size), is the most suitable to provide the higher iso-surface (0.266 and 0.286 cm2) at flow rates of 14.6 ml/min for gas, 3.0 and 7.8 ml/min for two different liquids, respectively. With the simulation results in hand, we carefully considered the choice of material for the fabrication of the flow dissolver. Our experience with diverse materials based microreactors pointed us to stainless steel for the staggered baffle channel patterned plate and perfluorinated polyether (PFPE) for the nano-porous membrane. These materials offer sufficient physical toughness at high flow rates of pressure and low temperature (−95 °C) as well as chemical inertness at a strong base such as organolithiums (Supplementary Fig. 2)44. Next, we fabricated two types of gas-liquid flow devices (GLDs) in which the PFPE nano-porous membrane is sandwiched and clamped by two stainless steel plates patterned with the baffle structures. The internal volume for the gas-liquid mixing space can be changed by controlling the length of the staggered baffle channels.

a A schematic concept and fabrication of gas-liquid flow device (GLD) via highly permeable membrane and staggered baffle channels. b A schematic concept of GLD-1 and GLD-2. c A detailed scheme in a fast gas-liquid reaction space in the GLD-2 device with three inlets. d An optical SEM image of the 800 nm of pore size of nano-porous membrane (scale bar, 100 nm). e An optical image of GLD-2 assembly with in- and outlet tubes.

The GLD type-1 (GLD-1) was designed for fast gas-liquid dissolution under the mild condition and stable feeding of the resulting CF3H solution to our total flow set-up (Fig. 2b upside and Supplementary Fig. 3). One important point for the generation of CF3− using the continuous flow system is the solubility of gaseous CF3H into the liquid phase involving reactants. In case CF3H is not or partially dissolved prior to its reaction start, it is difficult to interpret the experimental outcome regarding the generation, reaction, or decomposition of CF3− in flow. Thus, we first decided to explore reaction conditions by feeding a solvent for the rapid and complete dissolution at −20 °C through the GLD-1, before the direct use of gaseous CF3H without the additional solvent. The achievement of rapid gas dissolution is also crucial to minimize the total time of the flow process as well as to simplify the flow set-up for green and sustainable chemistry in terms of safety enhancement and cost-reduction45,46,47,48,49,50. The GLD-1 has a precisely optimized BS-4 structure with a 5 cm long channel and two inlets for liquid THF and gaseous CF3H and one outlet for the resulting CF3H solution which is supplied for the reaction. We tested the GLD-1 and could successfully know that CF3H was dissolved in THF solution over 98% even within 1.3 s at flow rates of 3.0 ml/min for THF and 14.6 ml/min for CF3H with a stable feeding of CF3H solution (pressure drop: 1.6 kPa). This result showed that GLD-1 has a much superior dissolution rate to the same volume of the general T-junction capillary tubing system. Also, the tendency of the quantitative experimental test in different baffle structures is correctly matched with the CFD simulation result (Supplementary Table 6 and Supplementary Fig. 5).

On the other hand, the GLD type-2 (GLD-2) was fabricated for the fast gas-liquid reaction for direct use of gaseous CF3H and liquid reactant with precise time control (Fig. 2b downside). After exploration and optimization of proper reaction conditions for the generation of CF3− by our complete set-up, the GLD-2 can be applied to the rapid biphasic reaction with the achievement of a more simplified reaction system. Furthermore, in the viewpoint of an atom- and step-economy, the direct reaction between gaseous CF3H and liquid base for metalation is considerably economical. Figure 2c describes the conceptual design for the channel structure, which has the 5 cm length of BS-4 structure providing maximized contact area at flow rates of 7.8 ml/min for a mixture of THF/Et2O and 14.6 ml/min for CF3H, respectively (pressure drop: 9.1 kPa and Supplementary Table 4). An optical SEM image of nano-porous membrane and an optical image of GLD-2 assembled with inlet and outlet tubes are also shown in Fig. 2d, e, respectively.

Exploring reaction condition using GLD-1

We began our experimental investigation into exploring the type of bases for rapid metalation of CF3H followed by trapping with a stoichiometric amount of benzophenone using GLD-1 and flow reactors (Supplementary Table 7). We found that potassium tert-butoxide (t-BuOK) and potassium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide (KHMDS) were not efficient to obtain the desired product, 2,2,2-trifluoro-1,1-diphenylmethanol (1a) due to their insufficient reactivity within short residence time at a cryogenic temperature, although they were suitable in the in situ method as previously reported12. Various organolithium reagents such as lithium diisopropylamide, lithium tetramethylpiperidine, phenyllithium (PhLi), and alkyllithiums (MeLi, n-BuLi, s-BuLi, and t-BuLi) also did not give the product 1a at all. The latter gave over 71% yield of byproduct 2 via the reaction of t-BuLi with benzophenone. These results indicate that organolithium reagents are also inefficient in the metalation of CF3H. Subsequently, we attempted to achieve much faster C–H metalation of CF3H via a mixture of organolithium and potassium alkoxide called Schlosser’s base or superbase51. The reaction was conducted in the flow reaction system consisting of three T-shaped mixers (M1, M2, and M3) and tube reactors (R1, R2, and R3) and GLD-1 (Fig. 3a). Organolithium and t-BuOK were mixed in M1 and R1 for 6.0 s of residence time and sequentially reacted with CF3H solution in M2 and R2. Three types of organolithiums (PhLi, n-BuLi, and s-BuLi) with 3 equivalents of t-BuOK were used and residence time in R2 (tR2) was changed from 0.04 to 6.5 s by changing the diameter and length of the R2 at −78 °C (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 8). Surprisingly, these combinations allowed obtaining the desired product 1a. The less-reactive organolithium gave the better yield of the product 1a in the order of PhLi > n-BuLi > s-BuLi, probably because of the competitive side reaction of superbase with THF solvent52 or nucleophilic attack of organolithium to CF3H53. We obtained product 1a in 81% yield using PhLi with t-BuOK when tR2 was 0.15 s at −78 °C, but a small amount of byproduct 2 was detected (4%), which indicates that CF3− was not completely generated in R2. For better yield without the formation of byproduct 2, a variety of reaction conditions were explored (T = −20 °C to −95 °C, tR2 = 0.04–6.5 s) to obtain a contour plot (Fig. 3c), which gave exact information on the stability and the lifetime of CF3− in various temperatures. The contour plot divulged that the yield of 1a was not sufficient in the range of short residence time below 0.15 s for tR2 at −78 and −95 °C due to incomplete metalation of CF3H and CF3− has an short lifetime which is largely sensitive to the temperature. We eventually found the proper time and cryogenic zone for the existence of bare CF3− in the flow reactor at 0.4 s for tR2 under −95 °C, which gave an opportunity to solely utilize CF3− in absence of the stabilizer and the reaction partner. Under the optimized condition, product 1a was obtained in 93% yield without the detectable byproduct. Then, the effect of the amount of t-BuOK on the yield of product 1a was investigated (Fig. 3d). The product 1a was gradually increased from 0 to 93% yield and the byproduct 2 was oppositely decreased from 98 to 0% with increasing the amount of t-BuOK, probably because the excess amount of t-BuOK provide a solubilizing adduct of superbase with stabilization, which has a positive effect on the reactivity54.

Direct use of gaseous CF3H for ex situ reaction using GLD-2

Based on the information obtained using the flow system involving GLD-1, we next utilized the integrated device, GLD-2 that enabled a direct mixing of CF3H and superbase, and following reactions. In the GLD-2, product 1a was obtained in 66% yield with 28% of the byproduct 2. To accomplish the rapid metalation, the equivalent of the PhLi was slightly increased to 1.3 keeping the ratio of PhLi and t-BuOK (1:3), which raised the yield of 1a to 84% without any byproduct 2. This result indicates that the generation of CF3− through direct biphasic reaction and subsequent bimolecular trapping reaction with benzophenone was successfully accomplished in the GLD-2 under cryogenic temperature.

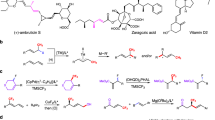

The reactions were conducted using various electrophilic substrates such as ketones, aldehydes, an ester, isocyanates, isothiocyanates, and chalcones in the GLD-2 (Fig. 4). We obtained the desired products (1a–1j) through the reactions with benzophenones and benzaldehydes bearing electron-donating (-OMe and -Me) or withdrawing group (-F, and -Cl) in good yields of 62–83%. The reactions with 9-anthracenecarboxaldehyde and 2-thiophenecarboxaldehyde gave the desired products 1k and 1l in 72% and 51% yield, respectively. The reaction of methyl benzoate represented the remarkable advantage of our system by affording the corresponding product 1m in 68% yield without a significant loss caused by the sequential addition to the acyl group or unwanted esterification by t-BuOK55. For this reason, the yield was more than twice as high as the reported in situ quenching method12. Aryl compounds bearing isocyanate and isothiocyanate group effectively reacted as well with flow-generated CF3− to give the corresponding products (1n–1q) in 60–92% good yields. We also accomplished the reactions with chalcones to give the desired products (1r–1u) in 78–94% yields. We conducted the silylation for the synthesis of Ruppert-Prakash-type reagents as well. Pleasingly, ex situ generated CF3− was successfully reacted with triethylsilyl chloride and triisopropylsilyl chloride and gave product 1v in 79% and 1w in 87% yield, respectively. Potassium (trifluoromethyl)trifluoroborate (CF3BF3K) 1x was also prepared by borylation with trimethoxyborane, B(OMe)3 followed by sequential reaction with potassium bifluoride in 80% yield.

We next sought to strengthen the powerful advantage of our synthetic methodology by the accomplishment of chemoselective reactions with substrates bearing two electron-withdrawing groups. The selective nucleophilic addition with electrophiles bearing two same functional groups (acyl or formyl group) such as 1,4-cyclohexanedione, benzoquinone, and terephthalaldehyde gave the corresponding products (3a–3c) in 54–75% yields without over-reacted byproduct. We also conducted the reaction with benzaldehyde bearing an additional functional group (cyano, nitro, or methoxycarbonyl group) and chalcone bearing a nitro group, which provided the desired products 3d–3g over 55% yield. It is highly noteworthy that we cannot obtain the desired products at all by the in situ quenching method in the flask. The results clearly show that our methodology is highly valuable for accomplishing protecting-group-free synthesis of multi-functionalized molecules.

Continuous multi-gram-scale synthesis using one-flow system

Lastly, we carried out the multi-gram-scale synthesis of three important chemical reagents which are used for nucleophilic trifluoromethylation using the GLD-2 device (Fig. 5). An integrated flow system to achieve one-flow CF3H supply, the formation of superbase, CF3− generation, and trifluoromethylation of silanes or borane continuously operated for 1 h, to result in the successful preparation of target compounds, trifluoromethyl silanes (1v and 1w), and CF3BF3K (1x) in good isolated yields and remarkable productivity (71–83%, 4.7–6.8 g/h). Although the GLD-2 is quite small enough to fit on one hand, a high total flow rate (13.8 ml/min) enables large-scale production, unlike the ordinary microfluidic system.

Methods

Reaction with various electrophiles in flow

A solution of PhLi (0.13 M in Et2O, 6.0 ml/min) and a solution of t-BuOK (1.3 M in THF, 1.8 ml/min) were introduced to M (inner tube ϕ = 250 μm) by syringe pumps and passed through tube reactor (ϕ = 1000 μm, L = 100 cm). The resulting solution and CF3H (flow rate: 14.6 ml/min) were introduced to two inlets of the GLD-2 device and CF3H was introduced by MFC. The resulting solution was passed through a nano-porous membrane sandwiched by a staggered baffle structure and was mixed with a solution of various electrophiles (0.3 M in THF, 3.0 ml/min). The resulting solution was passed through tube reactor (ϕ = 1000 μm, L = 50 cm). After a steady-state was reached (90 s), the product solution was collected for 30 s while being quenched with saturated NH4Cl aqueous solution (2 ml). For the isolation of the product, the resulting solution was extracted with Et2O (3 × 10 ml), then the organic phase was extracted with brine (10 ml), dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated. The crude product was purified by column chromatography to give the desired product.

Data availability

All other data that support the findings of this study, which include experimental procedures and compound characterization, are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information.

References

Muller, K., Faeh, C. & Diederich, F. Fluorine in pharmaceuticals: looking beyond intuition. Science 317, 1881–1886 (2007).

Meanwell, N. A. Fluorine and fluorinated motifs in the design and application of bioisosteres for drug design. J. Med. Chem. 61, 5822–5880 (2018).

Liu, X., Xu, C., Wang, M. & Liu, Q. Trifluoromethyltrimethylsilane: nucleophilic trifluoromethylation and beyond. Chem. Rev. 115, 683–730 (2015).

Okusu, S., Hirano, K., Yasuda, Y., Tokunaga, E. & Shibata, N. Flow trifluoromethylation of carbonyl compounds by Ruppert–Prakash reagent and its application for pharmaceuticals, efavirenz and HSD-016. RSC Adv. 6, 82716–82720 (2016).

Geri, J. B. & Szymczak, N. K. Recyclable trifluoromethylation reagents from fluoroform. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 9811–9814 (2017).

Mitobe, K. et al. Preparation and reactions of CF3‐containing phthalides. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 6944–6951 (2018).

Trost, B. M. The atom economy—a search for synthetic efficiency. Science 254, 1471–1477 (1991).

Han, W., Li, Y., Tang, H. & Liu, H. Treatment of the potent greenhouse gas, CHF3—an overview. J. Fluor. Chem. 140, 7–16 (2012).

Shono, T., Ishifune, M., Okada, T. & Kashimura, S. Electroorganic chemistry. 130. A novel trifluoromethylation of aldehydes and ketones promoted by an electrogenerated base. J. Org. Chem. 56, 2–4 (1991).

Folléas, B., Marek, I., Normant, J.-F. & Jalmes, L. S. Fluoroform: an efficient precursor for the trifluoromethylation of aldehydes. Tetrahedron Lett. 39, 2973–2976 (1998).

Large, S., Roques, N. & Langlois, B. R. Nucleophilic trifluoromethylation of carbonyl compounds and disulfides with trifluoromethane and silicon-containing bases. J. Org. Chem. 65, 8848–8856 (2000).

Prakash, G. S., Jog, P. V., Batamack, P. T. & Olah, G. A. Taming of fluoroform: direct nucleophilic trifluoromethylation of Si, B, S, and C centers. Science 338, 1324–1327 (2012).

Shono, T., Ishifune, M., Okada, T. & Kashimura, S. Electroorganic chemistry. 130. A novel trifluoromethylation of aldehydes and ketones promoted by an electrogenerated base. J. Org. Chem. 56, 2–4 (1991).

Kawai, H., Yuan, Z., Tokunaga, E. & Shibata, N. A sterically demanding organo-superbase avoids decomposition of a naked trifluoromethyl carbanion directly generated from fluoroform. Org. Biomol. Chem. 11, 1446–1450 (2013).

Okusu, S., Hirano, K., Tokunaga, E. & Shibata, N. Organocatalyzed trifluoromethylation of ketones and sulfonyl fluorides by fluoroform under a superbase system. ChemistryOpen 4, 581–585 (2015).

Punna, N. et al. Stereodivergent trifluoromethylation of N-sulfinylimines by fluoroform with either organic-superbase or organometallic-base. Chem. Commun. 54, 4294–4297 (2018).

Lishchynskyi, A. et al. The trifluoromethyl anion. Angew. Chem. 127, 15504–15508 (2015).

Miloserdov, F. M. et al. The trifluoromethyl anion: evidence for [K (crypt‐222)]+. Helv. Chim. Acta 100, e1700032 (2017).

Harlow, R. L. et al. On the structure of [K (crypt‐222)]+. Helv. Chim. Acta 101, e1800015 (2018).

Prakash, G. S., Krishnamurti, R. & Olah, G. A. Synthetic methods and reactions. 141. Fluoride-induced trifluoromethylation of carbonyl compounds with trifluoromethyltrimethylsilane (TMS-CF3). A trifluoromethide equivalent. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 111, 393–395 (1989).

Saito, T., Wang, J., Tokunaga, E., Tsuzuki, S. & Shibata, N. Direct nucleophilic trifluoromethylation of carbonyl compounds by potent greenhouse gas, fluoroform: Improving the reactivity of anionoid trifluoromethyl species in glymes. Sci. Rep. 8, 11501 (2018).

Fujihira, Y. et al. Synthesis of trifluoromethyl ketones by nucleophilic trifluoromethylation of esters under a fluoroform/KHMDS/triglyme system. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 17, 431–438 (2021).

Prakash, G. S. et al. Long‐lived trifluoromethanide anion: a key intermediate in nucleophilic trifluoromethylations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 126, 11759–11762 (2014).

Pace, V. et al. Efficient access to all‐carbon quaternary and tertiary α‐functionalized homoallyl‐type aldehydes from ketones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 12677–12682 (2017).

Parisi, G. et al. Exploiting a “Beast” in carbenoid chemistry: development of a straightforward direct nucleophilic fluoromethylation strategy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 13648–13651 (2017).

Zanardi, A., Novikov, M. A., Martin, E., Benet-Buchholz, J. & Grushin, V. V. Direct cupration of fluoroform. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 20901–20913 (2011).

Fu, W. C., MacQueen, P. M. & Jamison, T. F. Continuous flow strategies for using fluorinated greenhouse gases in fluoroalkylations. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 7378–7394 (2021).

Köckinger, M. et al. Utilization of fluoroform for difluoromethylation in continuous flow: a concise synthesis of α-difluoromethyl-amino acids. Green. Chem. 20, 108–112 (2018).

Musio, B., Gala, E. & Ley, S. V. Real-time spectroscopic analysis enabling quantitative and safe consumption of fluoroform during nucleophilic trifluoromethylation in flow. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 6, 1489–1495 (2018).

Hirano, K., Gondo, S., Punna, N., Tokunaga, E. & Shibata, N. Gas/liquid‐phase micro‐flow trifluoromethylation using fluoroform: trifluoromethylation of aldehydes, ketones, chalcones, and N‐sulfinylimines. ChemistryOpen 8, 406–410 (2019).

Ono, M. et al. Pentafluoroethylation of carbonyl compounds using HFC-125 in a flow microreactor system. J. Org. Chem. 86, 14044–14053 (2021).

Colella, M. et al. Fluoro‐substituted methyllithium chemistry: external quenching method using flow microreactors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 10924–10928 (2020).

Kim, H., Nagaki, A. & Yoshida, J.-I. A flow-microreactor approach to protecting-group-free synthesis using organolithium compounds. Nat. Commun. 2, 264 (2011).

Yoshida, J.-I., Takahashi, Y. & Nagaki, A. Flash chemistry: flow chemistry that cannot be done in batch. Chem. Commun. 49, 9896–9904 (2013).

Kim, H. et al. Submillisecond organic synthesis: outpacing fries rearrangement through microfluidic rapid mixing. Science 352, 691–694 (2016).

Yen, B. K., Günther, A., Schmidt, M. A., Jensen, K. F. & Bawendi, M. G. A microfabricated gas–liquid segmented flow reactor for high‐temperature synthesis: the case of CdSe quantum dots. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 5447–5451 (2005).

Han, S., Kashfipour, M. A., Ramezani, M. & Abolhasani, M. Accelerating gas–liquid chemical reactions in flow. Chem. Commun. 56, 10593–10606 (2020).

Yang, L. & Jensen, K. F. Mass transport and reactions in the tube-in-tube reactor. Org. Process Res. Dev. 17, 927–933 (2013).

Wang, Z. et al. Effects of bubble size on the gas–liquid mass transfer of bubble swarms with Sauter mean diameters of 0.38–4.88 mm in a co‐current upflow bubble column. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 95, 2853–2867 (2020).

Femmer, T., Eggersdorfer, M. L., Kuehne, A. J. & Wessling, M. Efficient gas–liquid contact using microfluidic membrane devices with staggered herringbone mixers. Lab Chip 15, 3132–3137 (2015).

Ahmed, A. K. A. et al. Generation of nanobubbles by ceramic membrane filters: the dependence of bubble size and zeta potential on surface coating, pore size and injected gas pressure. Chemosphere 203, 327–335 (2018).

Ataki, A. & Bart, H. J. Experimental and CFD simulation study for the wetting of a structured packing element with liquids. Chem. Eng. Technol. 29, 336–347 (2006).

Zhang, J., Tejada-Martínez, A. E. & Zhang, Q. Developments in computational fluid dynamics-based modeling for disinfection technologies over the last two decades: a review. Environ. Model. Softw. 58, 71–85 (2014).

Kim, J.-O. et al. A monolithic and flexible fluoropolymer film microreactor for organic synthesis applications. Lab Chip 14, 4270–4276 (2014).

Ley, S. V., Fitzpatrick, D. E., Myers, R. M., Battilocchio, C. & Ingham, R. J. Machine‐assisted organic synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 10122–10136 (2015).

Tsubogo, T., Oyamada, H. & Kobayashi, S. Multistep continuous-flow synthesis of (R)-and (S)-rolipram using heterogeneous catalysts. Nature 520, 329–332 (2015).

Cambie, D., Bottecchia, C., Straathof, N. J., Hessel, V. & Noel, T. Applications of continuous-flow photochemistry in organic synthesis, material science, and water treatment. Chem. Rev. 116, 10276–10341 (2016).

Plutschack, M. B., Pieber, B. U., Gilmore, K. & Seeberger, P. H. The hitchhiker’s guide to flow chemistry. Chem. Rev. 117, 11796–11893 (2017).

Coley, C. W. et al. A robotic platform for flow synthesis of organic compounds informed by AI planning. Science 365, eaax1566 (2019).

Dallinger, D., Gutmann, B. & Kappe, C. O. The concept of chemical generators: on-site on-demand production of hazardous reagents in continuous flow. Acc. Chem. Res. 53, 1330–1341 (2020).

Schlosser, M., Jung, H. C. & Takagishi, S. Selective mono-or dimetalation of arenes by means of superbasic reagents. Tetrahedron 46, 5633–5648 (1990).

Clayden, J. & Yasin, S. A. Pathways for decomposition of THF by organolithiums: the role of HMPA. N. J. Chem. 26, 191–192 (2002).

Maruyama, K., Saito, D. & Mikami, K. (Sila) Difluoromethylation of Fluorenyllithium with CF3H and CF3TMS. SynOpen 2, 0234–0239 (2018).

Klett, J. Structural motifs of alkali metal superbases in non‐coordinating solvents. Chem. Eur. J. 27, 888–904 (2021).

Yang, H. S., Macha, L., Ha, H.-J. & Yang, J. W. Functionalisation of esters via 1, 3-chelation using NaO t Bu: mechanistic investigations and synthetic applications. Org. Chem. Front. 8, 53–60 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledgment the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIP). National Research Foundation of Korea grant No. 2017R1A3B1023598, National Research Foundation of Korea grant No. 2020R1C1C1014408.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.K. and H.-J.L. designed and directed the project. H.K. and H.-J.L. conceived and designed the experiments. J.-U.J. and S.-J.Y. fabricated the device and J.-U.J. tested devices at POSTECH. S.-J.Y. conducted a CFD simulation at POSTECH. H.-J.L. conducted synthetic experiments at Korea University. H.-J.L., D.-P.K. and H.K. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. All authors contributed to discussions.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, HJ., Joo, JU., Yim, SJ. et al. Ex-situ generation and synthetic utilization of bare trifluoromethyl anion in flow via rapid biphasic mixing. Nat Commun 14, 1231 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-35611-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-35611-9

This article is cited by

-

Continuous Flow Generation of Highly Reactive Organometallic Intermediates: A Recent Update

Journal of Flow Chemistry (2024)