Abstract

Electrochemical water oxidation enables the conversion of H2O to H2O2. It holds distinct advantages to the O2 reduction reaction, which is restricted by the inefficient mass transfer and limited solubility of O2 in aqueous media. Nonetheless, most reported anodes suffer from high overpotentials (usually >1000 mV) and low selectivity. Electrolysis at high overpotentials often causes serious decomposition of peroxides and leads to declined selectivity. Herein, we report a ZnGa2O4 anode with dual active sites to improve the selectivity and resist the decomposition of peroxides. Its faradaic efficiency reaches 82% at 2.3 V versus RHE for H2O2 generation through both direct (via OH−) and indirect (via HCO3−) pathways. The percarbonate is the critical species generated through the conversion of bicarbonate at Ga-Ga dual sites. The peroxy bond is stable on the surface of the ZnGa2O4 anode, significantly improving faradaic efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is a clean and valuable oxidant with wide applications in chemical synthesis1,2, energy technology3,4,5, and environmental remediation6,7,8. Currently, most H2O2 is produced by an anthraquinone process9, which requires expensive Pd catalysts and produces a huge volume of organic waste10. Considerable efforts have been dedicated to producing H2O2 in small-scale and more sustainable ways11,12,13,14. For example, the direct synthesis method (Eq. (1)) has been developed using H2, O2, and noble metal catalysts in a liquid medium15,16,17. However, inert gases (N2 or CO2) are needed to dilute the reactant gases to eliminate the explosive risk.

The inherent limitations of Eq. (1), including the low solubility and inefficient mass transfer of gas reactants, the requirement for high-valued H2, and the safety concerns, have motivated researchers toward more feasible production routes. Alternatively, H2O2 generation can start with abundant feedstocks such as water and oxygen. The main-stream O2 reduction reaction (ORR, Eq. (2)) has been demonstrated on some noble metals or carbon-based catalysts12,18,19,20.

However, 2 electron-ORR is subjected to low solubility (8 mg L−1, 1 atm, 25 °C) and low diffusion coefficient of O2 in water (2.1 × 10−5 cm−2 s−1)21. The O2 reduction way requires continuous feeding of O2 or air to the cathode surface, which brings extra production costs. Though these mass transfer problems can be overcome by gas diffusion electrodes (GDEs), it has been widely recognized that the effectiveness of GDEs suffers from a common flooding effect22,23, i.e. electrolyte penetration into the porous GDE. By contrast, the kinetics of the water oxidation reaction (WOR, Eq. (3)) would not be limited by the mass transfers of reactants. A high faradaic current density can therefore be attained. 2e-WOR can meet the onsite demand for H2O2 in O2-deficient environments, such as bacteria-contaminated water bodies8, which represents an obvious advantage over other production methods that require O2. Besides, the WOR reaction can be coupled with reduction reactions at the cathode, including hydrogen evolution, ORR, and CO2 reduction reaction, to fully utilize the half-cell reactions.

There are still several challenges to use the 2e-WOR technique effectively. First, the faradaic efficiency (FE) of H2O2 is low, especially at low overpotentials. Though some metal oxides and carbon-based catalysts have been reported for 2e-WOR7,24,25,26, most of these catalysts usually require overpotentials larger than 1000 mV to achieve a satisfactory FE. High overpotentials required for anodes will reduce the overall energy efficiency of the electrocatalytic cells. Recently, progress has been made in lowering the overpotential by fabricating new anodes, for example, H2O2 FE reaching 66% on CP/PTFE with an overpotential of 640 mV27, and reaching 72% on CuWO4 with an overpotential of 740 mV28. Moreover, the electrochemical stability (including stable generation rate and FE) and the structural stability are also challenging because of the highly oxidative environment. Nevertheless, the main goal of 2e-WOR research is still to develop efficient and stable anodes with high selectivity at low overpotentials. For the studies of anodic H2O2 production, the performance of anodes is usually evaluated in bicarbonate electrolytes (usually 2 M KHCO3) since many studies have demonstrated the promotion effect7,29,30,31 and the stabilizing effect32 of bicarbonate toward anodic H2O2 production. A critical but often ignored issue is the decomposition of H2O2 during long-time water oxidation. For example, the H2O2 generation rate declines after passing 100 C for FTO/BiVO429, after 3 h-electrolysis for FTO/CaSnO324, after 3 h-reaction for FTO/Sb2O326, after for 1000 s for boron-doped diamond33, and after 150 min-electrolysis for CaSnO3@CF34. A similar observation was also reported on C, N-codoped TiO2 in 0.05 M Na2SO4 after 2 h-electrolysis35. In these reports (details in Table S1), the H2O2 concentration reaches a saturation level and does not increase further. Factors associated with the concentration plateau are considered inseparable from the instability of H2O2 during electrolysis but await in-depth investigation. Typically, the decomposition of H2O2 can occur either on the anode surface or in the bulk electrolyte. Firstly, the oxidation of H2O2 occurs thermodynamically at a relatively low potential of 0.68 V versus RHE (reverse of Eq. (2)). Therefore, there is a need to develop anode materials with sluggish H2O2 oxidation kinetics. Otherwise, electrolysis at high potentials would cause severe H2O2 electro decomposition on the anode surface. Secondly, anode material may induce H2O2 decomposition, and the decomposition rate is material-dependent26,30,36. For instance, the current density associated with the electro decomposition of H2O2 on BiVO4 is estimated to be ~11 μA cm−2 mM H2O2 in 0.5 M KHCO3 electrolyte30, which is an order of magnitude smaller than that on Pt surface in phosphate buffer36. Thirdly, H2O2 can undergo disproportionation (Eq. (4)) to give rise to O2 and water with the release of heat.

Based on these considerations, one can anticipate that developing anodes with a high tolerance and low decomposition rate of H2O2 are prerequisites for achieving high FE.

Here, we develop a ZnGa2O4 anode featuring dual active site for H2O2 generation through WOR. At 2.3 V versus RHE, this ZnGa2O4 shows its highest FE of ~82%. Significantly, by combining the in situ spectral evidence and theoretical calculations, it is identified that the generation of H2O2 follows both the direct (OH--mediated) and indirect (HCO3--mediated) pathway at the ZnGa2O4 anode. Theoretical studies indicate that bicarbonate species can bind with Ga-Ga dual sites and then be oxidized to percarbonate species. The O–O bond in peroxide species is stable on the surface of ZnGa2O4, which helps to maintain high FE and high H2O2 concentration levels.

Results

Anode material characterizations

The nanoflower-like ZnGa2O4 was synthesized by the solvothermal method modified from a reported procedure37. The X-ray diffraction pattern of as-prepared sample is in accordance with that of spinel ZnGa2O4 (PDF#38-1240) (Fig. 1a), indicating a pure ZnGa2O4 phase with high crystallinity. SEM image reveals the ZnGa2O4 catalyst has a monodisperse microsphere with a uniform diameter of ~5 μm (Fig. 1b). It is clearly shown a flower-like structure consisting of self-assembly nanosheets. From the transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images (Fig. 1c, d), the nanosheets show irregular shape and clear lattice fringes were observed in the high-resolution TEM image (Fig. 1d and Figure S1), indicating the high crystallinity of the catalysts. The lattice fringes in Fig. 1d spaced 0.294 nm apart can be well assigned to the (220) facet of ZnGa2O4, and the lattice fringes spaced 0.25 nm apart (Figure S1c, d) can be assigned to (311) facet. From the polycrystalline electron diffraction pattern (Fig. 1e), it is found that the main diffraction spots correspond to the (440) facet (the secondary diffraction of the (220) facet) and the (311) facet. And in the selected area electron diffraction pattern (Figure S1b), the diffraction spots corresponding to the (311) and (220) facets are clearly observed. Then using the scanning transmission electron microscopy electron energy loss spectroscopy (STEM-EELS) technique, as shown in Fig. 1f, a uniform elemental distribution is evidenced for the catalyst particles.

H2O2 generation performance through selective water oxidation

The ZnGa2O4 anode was designed for anodic H2O2 production (design principle can be found in Method part). As shown in Figure S2, most ZnGa2O4 particles are in single-particle dispersion on the anode surface rather than in agglomerates. For the electrochemical water oxidation reaction, as shown in Fig. 2a, the generation of H2O2 is accompanied by the decomposition of H2O2 on the anode surface (oxidation of H2O2 to O2) or in the bulk solution (Eq. (4)). The H2O2 generation performance evaluation is based on the accumulated H2O2 concentration in the anolyte. From the LSV curves in Fig. 2b, the overpotential at 10 mA cm−2 of the ZnGa2O4 anode was about 270 mV, suggesting a good water oxidation activity of the ZnGa2O4 anode. Next, the FE of H2O2 was evaluated in a potential range from 2.0 to 3.5 V versus RHE (details can be found in Table S2), and the corresponding current density was shown in Figure S3a. From Fig. 2c, the ZnGa2O4 anode shows a FE as high as 38% at 2.0 V versus RHE. Significantly, the peak FE reaches 82% at 2.3 V versus RHE (overpotential of 540 mV), representing a high selectivity of ZnGa2O4 towards H2O2 formation. As shown in Fig. 2d, for example, maximum FE of 71% at 3.1 V versus RHE on BiVO438, 76% at 3.2 V versus RHE on CaSnO324, 81% at 3.1 V versus RHE on ZnO25, 28% at 3.17 V versus RHE on boron-doped diamond (BDD)33, 87% at 2.85 V versus RHE on BDD (B/D ratio = 0.012)39, 22% at 3.08 V versus RHE on Sb2O340, 79% at 3.2 V versus RHE on Bi2WO6:5%Mo7, 8% at 2.9 V versus Ag/AgCl on C,N codoped-TiO2 in an electrolyte of pH = 335. In comparison to these reported anodic materials that usually require overpotentials larger than 1000 mV to afford a high selectivity, the developed ZnGa2O4 anode shows competitive FE at a low overpotential of 540 mV. Meanwhile, as shown in Table S3, the current density of the ZnGa2O4 anode is comparable to the reported performance at similar potentials. And the H2O-to-H2O2 partial current density (Figure S3b) is higher than that of previous oxide anodes26,28,38. At a potential equal to or higher than 2.3 V versus RHE, O2 bubbles were observed on the anode surface, which is considered from the O2 evolution reaction (OER).

a Scheme of the electrochemical H2O2 production on anodes through a water oxidation reaction. b LSV curves recorded in 2 M KHCO3 before and after a stability test. The scan rate is 5 mV s−1. c H2O2 FE of the prepared ZnGa2O4 anode at different potentials in 2 M KHCO3 electrolyte (Error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent measurements). d The FE of typically reported anodes including ZnO25, boron-doped diamond (BDD)33, BDD (B/D ratio = 0.012)39 BiVO438, CaSnO324, Bi2WO6:Mo7, and Sb2O326 for H2O2 generation in bicarbonate/carbonate electrolyte for comparison. The orange star represents the thermodynamic potential of 2e-WOR. e The H2O2 generation rate on the ZnGa2O4 anode at different potentials. f The accumulated amount of H2O2 in 60 min-electrolysis under different applied potentials, (50 mL electrolyte, electrode area = 0.5 cm2). g The FE and generation rate of H2O2 on ZnGa2O4 anode with an applied bias of 2.3 V versus RHE in 700 minutes. The electrolyte was periodically replaced.

The generation rate is another important parameter in evaluating the performance of catalysts. The H2O2 generation rate of the ZnGa2O4 anode at different potentials was measured (Fig. 2e). The generation rate exceeds 10 μmol cm−2 min−1 at potentials higher than 2.7 V versus RHE. Such a high generation rate can meet the requirement of H2O2 for many applications, including water disinfection (>1 mM)41, and Fenton reaction (>1 mM)42,43,44. In addition, it is found that higher concentrations of KHCO3 lead to higher FE and generation rates for H2O2 production (Figure S4). Then the accumulated amounts of H2O2 in 60 minutes under different potentials (2.3, 2.5, and 2.7 V versus RHE) were recorded. The product formed on the anode would be desorbed into bulk solution and accumulates to high concentrations over time. As shown in Fig. 2f, the real-time concentration of H2O2 increases almost linearly in 60 minutes, which indicates that the decomposition rate is not notable compared to the generation rate of H2O2. Finally, the cycle water oxidation tests were conducted at 2.3 V versus RHE (Figure S5 and Fig. 2g). The electrolyte was periodically replaced to minimize the effect of changes in electrolyte composition. The H2O2 FE was measured for each test cycle (Fig. 2g), and a FE of ~78% was maintained after 700 min of continuous electrolysis. It also reveals that the generation rate decreased from 6.27 to 5.95 μmol cm−2 min−1 after 700 minutes of stability test. The LSV curve (Fig. 2b) was also recorded after the stability test and no apparent changes were observed in the comparison. The flower-like morphology of the ZnGa2O4 catalyst on the anode surface was retained after the stability test (Figure S6). By comparing the high-resolution X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy spectra of Zn 2p and Ga 3d obtained before and after the stability test, it can be inferred that the valence state of metal ions in this spinel structure is stable after the electrolysis test (Figure S7). The nearly unchanged LSV curves before and after the stability test, the slightly decreased FE after the 700-min electrolysis, and the unchanged morphology indicate the excellent durability of ZnGa2O4 catalyst under water oxidation conditions.

According to recent progress, anodic H2O2 production was also achieved in carbonate-based electrolytes45,46,47. Here, the H2O2 production performance of ZnGa2O4 anode in 2 M K2CO3 solution was then investigated (Figure S8). The ZnGa2O4 can afford a much higher current density in 2 M K2CO3 (Figure S8a) than in 2 M KHCO3 (Fig. 2b). The highest FE reaches 77%, but the corresponding potential is as high as 2.9 V versus RHE (Figure S8b). Figure S8c shows that the highest H2O2 generation rate of ~69 μmol cm−2 min−1 was achieved at 3.1 V versus RHE, which is much higher than that in 2 M KHCO3 electrolyte (21 μmol cm−2 min−1 at 3.1 V versus RHE). Next, at 2.9 V versus RHE, H2O2 concentration reaches 54 mM after 150 minutes (Figure S8d).

Decomposition of H2O2 during electrolysis

The real-time concentration of H2O2 in the anolyte over several hours is essential for realistic applications. Herein, the H2O2 concentration in 300 minutes was recorded under potentials of 2.3, 2.5, and 2.7 V versus RHE (Fig. 3a), and the corresponding current density can be found in Figure S9. Figure 3a reveals that the H2O2 concentration curves deviate obviously from the linear growth trend after 60 minutes-electrolysis and then reach a plateau after 240 min-electrolysis. The declining growth rate should be related to the decomposition of high concentrations of H2O2 in the electrolyte. At constant potential, the formation rate of H2O2 can be described as zero-order kinetics, and the decomposition of H2O2 follows the first-order kinetics related to the H2O2 concentration ([H2O2])48,49,50. The formation rate (rf) equals to Kf (Kf: formation rate constant); the decomposition rate (rd) equals Kd[H2O2], (Kd: decomposition rate constant). Thus, the real-time H2O2 concentration can be expressed as:

a The real-time H2O2 concentration as a function of time at 2.3, 2.5, and 2.7 V versus RHE. (60 mL electrolyte, electrode area = 0.5 cm2). The solid lines are the fitting curves. b The formation rate constant and decomposition rate constant of H2O2 on ZnGa2O4 anode at different potentials. c Electrodecomposition rate of H2O2 on ZnGa2O4 anode at different potentials in 2 M KHCO3. d Structure of H2O2-ZnGa2O4 before and after relaxation in the absence of bicarbonate (left) and the presence of bicarbonate (right). e Self-decomposition rate constants of H2O2 with different initial concentrations in 2 M KHCO3 solution. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent measurements.

Then according to the fitting results (Fig. 3a), the Kf under 2.3, 2.5 and 2.7 V versus RHE were calculated to be 0.06, 0.088, and 0.123 mM min−1, respectively. The corresponding Kd under 2.3, 2.5, and 2.7 V versus RHE was calculated to be 0.008, 0.01, and 0.013 min−1 (Fig. 3b). These results indicate that the formation and decomposition rate constants (i.e., Kf, Kd) are increased at higher potentials. In consequence, the decomposition rate (rd) increases at more positive potentials.

As shown in Figure S10, the apparent generation rates of H2O2 in 300 min-electrolysis gradually decrease over time because of H2O2 decomposition, which can be caused by the anode materials (electrodecomposition and chemical decomposition on anode surface), H2O2 disproportionation in the electrolyte, and the changes of the anolyte composition46 during electrolysis. To evaluate the electrodecomposition of H2O2 on the ZnGa2O4 anode, a current integration method (details can be found in the Method) was used51. As shown in Figure S11, at 2.3 and 2.5 V versus RHE, there is no significant increase in the current when adding 10 mM H2O2 to the electrolyte. The corresponding electrodecomposition rates are calculated to be 0.26, 0.42, and 0.77 μmol cm−2 min−1 at 2.3, 2.5, and 2.7 V versus RHE (in Fig. 3c), suggesting the higher electrodecomposition rates of H2O2 at more positive potentials. Therefore, the ZnGa2O4 anode affording high FE at a low potential can help to suppress the electrodecomposition of H2O2. Meanwhile, it has been reported that catalysts themselves can also induce the chemical decomposition of H2O252. Figure S12 shows a negligible difference in H2O2 stability between the control experiments, indicating that ZnGa2O4 would not decompose the generated H2O2. The influence of bicarbonate on H2O2 stability was then also explored, as adsorbed bicarbonate species have been reported to decompose the formed H2O253. The stability of the peroxy bond of H2O2 on ZnGa2O4 surface with and without bicarbonate anions was also examined by theoretical calculations. The bond length of O-O almost maintains its initial value after structure relaxation (Fig. 3d left). This indicates that the peroxy bond is less likely to decompose on the surface of ZnGa2O4. Similarly, on the surface of ZnGa2O4 with bicarbonate adsorbed, the bond length of O-O does not increase and the structure of H2O2 does not change greatly (Fig. 3d right). As a result, two hydrogen bonds are formed with one linked to the bicarbonate and another one linked to the oxygen atom from the ZnGa2O4 substrate, suggesting the H2O2 is less likely to decompose on the surface of ZnGa2O4 with adsorbed bicarbonate.

In addition to the decomposition on the anode, H2O2 would undergo disproportionation (Eq. (4)) in weak alkaline solutions or with the presence of metal impurities (usually transition-metal ions)54. Figure S13 records the remaining ratio of H2O2 with different initial concentrations ([H2O2]0) as a function of time. More than 60% of H2O2 self-decomposed after 360 minutes at room temperature when [H2O2]0 is in the range of 2–30 mM, indicating that the disproportionation can cause severe loss of H2O2. Similarly, a decrease of 19% in H2O2 concentration (from 1.1 to 0.89 mM) at an open circuit after 150 minutes was reported by Pangotra et al.46. The linear fitting curves in Figure S13 indicate that the disproportionation of H2O2 in 2 M KHCO3 solution is a zero-order reaction. Accordingly, the decomposition rate constants are determined to be 0.10 ~ 0.12 h−1 (Fig. 3e, details can be found in Figure S13). At last, the changes in conductivity and pH of anolyte were explored. In Figure S14, a decrease in conductivity (~ 3%) and an increase in pH (from 8.31 to 8.68) were recorded at 2.3 V versus RHE during the 300 minutes-electrolysis. It is considered that such slight changes in the electrolyte were not the main factors for the declined H2O2 generation rate. Therefore, for the anodic H2O2 production in the absence of a stabilizer, an integrated effect of H2O2 decomposition (in the bulk solution and at the anode surface) as well as the changes in electrolytes leads to the concentration plateau during continuous electrolysis. For the ZnGa2O4 anode, the above evidence reveals that disproportionation instead of the electrode composition is mainly responsible for the H2O2 concentration plateau.

Proposed reaction pathways

Then the reaction pathway is further investigated. First, the ZnGa2O4 anode was tested in other electrolytes including K2SO4, K2HPO4, KH2PO4, K2CO3, and KOH to study the effect of electrolyte composition on H2O2 generation. Considering that the above electrolytes have different oxidation potentials, the FE of H2O2 in different electrolytes was also tested at a constant current density (8 mA cm−2) by the chronopotentiometry method. The results are shown in Fig. 4a and Figure S15, it is found that the FE of H2O2 in 0.5 M KHCO3, 0.5 M K2SO4, 0.5 M KH2PO4, 0.5 M K2HPO4, 0.5 M K2CO3, and 0.5 M KOH are 32.5%, 2%, 0.3%, 0.8%, 3%, 2.3%, respectively. These observations indicate that HCO3− anions play an indispensable role in tailoring the selectivity of water oxidative reaction on the ZnGa2O4 anode. At potentials above 1.9 V versus RHE, it is accepted that the reaction mainly follows a direct water oxidation pathway (H2O/OH− to H2O2) in K2SO4, K2HPO4, and KH2PO4. However, in the presence of HCO3-, competing reactions involving the oxidation of HCO3− may occur on the anode surface (E(HCO4−/HCO3−) = 1.8 ± 0.1 V versus NHE)29. To gain insight into the evolution of HCO3− on the anode, experimental and theoretical investigations were conducted to explore the adsorption properties of these species.

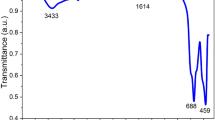

a The H2O2 FE of ZnGa2O4 anode in different electrolytes (0.5 M) at a constant current of 8 mA cm−2. b In situ Fourier transform infrared spectra of ZnGa2O4 at different potentials in 2 M KHCO3. c Two possible decomposition ways of HCO4 on the catalyst surface. Models of d HCO3-ZnGa2O4 and HCO4-ZnGa2O4 at (311) facet, e HCO3-ZnO and HCO4-ZnO, f HCO3-Ga2O3 and HCO4-Ga2O3 before and after structure relaxation.

The \({{HCO}}_{3}^{-}\)-mediated water oxidation pathway

The effect of bicarbonate on boosting FE of water oxidation towards H2O2 has ever been observed by our group8 and others29,55. However, this proposed reaction pathway needs more solid evidence and in-depth investigation. Here, in situ attenuated total reflectance Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR) technique was used to probe the reaction intermediates. A schematic representation of the electrochemical cell used for ATR-FTIR test can be found in Figure S16. In Fig. 4b, above 1.8 V versus RHE, the FTIR peaks at 1635 cm−1 and 1350 cm−1 are related to the symmetric C-O stretch of the adsorbed HCO3−56. When the applied potential increased to 2.2 V versus RHE, new FTIR bands were observed, and the intensity of bands become stronger at 2.4 V versus RHE. Specifically, the FTIR bands at 1286 cm−1 (valence C=O sym.) and 1265 cm−1 (C=O) can be matched to the symmetric C=O stretch of HCO4−/C2O62-57,58, indicating the formation of percarbonate species on the surface of ZnGa2O4. Therefore, the in situ spectral identifications prove the indirect reaction pathway for H2O2 generation via the transformation of bicarbonate to percarbonate species.

Next, models with \({{{{{{\rm{HCO}}}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) or \({{{{{{\rm{HCO}}}}}}}_{4}^{-}\) on the anode surface are constructed to explore the adsorption properties of bicarbonate species. The oxygen atoms of HCO4- are labeled for convenient discussion (Fig. 4c). As shown in Fig. 4d, after structure relaxation, the HCO3− could be adsorbed stably on the (311) facet of ZnGa2O4 by forming a bridged adsorption configuration (the O1 atom of *HCO3 binding with two Ga atoms). The adsorption energy is calculated to be −1.9 eV according to the following equation:

Where Ead is the adsorption energy, Etot is the total energy of the system, Esub is the energy of the substrate and Einter is the energy of HCO3− intermediate. The negative value of Ead confirms that the HCO3− adsorption on the (311) facet of ZnGa2O4 is favorable. As revealed by the in situ ATR-FTIR spectra, the adsorbed bicarbonate (*HCO3) can be oxidized to percarbonate species (*HCO4) on the surface of ZnGa2O4. Meanwhile, we also used theoretical calculations to study the energy change of the system (Theoretical calculations can be found in Method). In the theoretical calculations, (311), (220) and (\(\bar{1}\)12) facets were all considered. On (311) facet, the energy of the HCO4-ZnGa2O4 system decreases by 1.82 eV compared to that of HCO3-ZnGa2O4 at 2.3 V versus RHE at 298 K (Fig. 4d). The energy decreases by 0.16 eV on the (220) facet and decreases by 0.39 eV on the (\(\bar{1}\)12) facet at 2.3 V versus RHE at 298 K (Figure S17, S18, the energy changes are summarized in Table S4). These results indicate that the conversion of *HCO3 to *HCO4 on (311), (220), and (\(\bar{1}\)12) facets of ZnGa2O4 is thermodynamically favorable. It is inferred that the conversion of *HCO3 to *HCO4 originates from the special dual adsorption sites of *HCO3 on ZnGa2O4.

Then to gain insight into the HCO3− mediated pathway on the ZnGa2O4 anode, the adsorption properties of bicarbonate and percarbonate on ZnO and Ga2O3 were also investigated for comparison. For the model of ZnO-*HCO3, two oxygen atoms (O1 and O2) of *HCO3 adsorb with two Zn atoms (Fig. 4e top) separately, suggesting ZnO is favorable for *HCO3 adsorption. In the case of Ga2O3, the *HCO3 adsorbs on the surface of Ga2O3 by forming a single adsorption site of Ga (Fig. 4f). The formed HCO4- species on the anode surface can be desorbed into the bulk electrolyte, followed by a hydrolysis process to give H2O255. Alternatively, as a highly reactive species, the HCO4- may also undergo decomposition on the anode surface. According to DFT results, in the models of HCO4-ZnGa2O4 (Fig. 4d bottom, S17b, and S18b), the *HCO4 will decompose into *CO2 and *O2H by cleaving the -C-O3- bond after structure relaxation. Then the *CO2 will dissolve into the solution and form HCO3- by combing OH- anions, while *O2H, containing the -O-O- bond, would transform to H2O2. In such transformation, the peroxy bond keeps intact, representing one of the advantages of the ZnGaO4 anode. However, on the surface of ZnO, the *HCO4 would decompose to *CO3 and *OH by breaking the –O3–O4- bond (Fig. 4e). This may be caused by the strong interaction between the O atoms of percarbonates and the Zn sites. This decomposition may also be affected by the initial adsorption states. As shown in Fig. 4e, the O1 and O2 atoms of the *HCO3 form two Zn-O bonds with the ZnO substrate. This is different from the situation on ZnGa2O4, where two Ga are bonded with only one oxygen atom of *HCO3. Although both cases are dual-site adsorption, the –C–O3- bond of *HCO4 is less likely to be cleaved on the ZnO model. Instead, the *HCO4 will decompose to *CO3 and *OH by breaking the peroxy bond on ZnO. Then three O atoms of the *CO3 are bonded with Zn atoms as shown in Fig. 4e. In the case of Ga2O3, the *HCO4 is just stably adsorbed on the anode surface (Fig. 4f), where the O1 or O2 atom of *HCO4 is bonded with a Ga site. Such adsorption configuration avoids the decomposition of *HCO4.

The OH--mediated water oxidation pathway

The generation of H2O2 in electrolytes without bicarbonate (Fig. 4a) indicates the direct water oxidation reaction on ZnGa2O4 anode. Prior studies have proposed that the adsorption energy of *OH (ΔG*OH) on the surface of the catalyst determines the selectivity of WOR38,59. Small ΔG*OH often causes the evolution of O2 while large ΔG*OH leads to the formation of ·OH radicals. To produce H2O2, a suitable ΔG*OH should be smaller than 2.4 eV and larger than 1.6 eV. According to DFT results, after relaxation, it is discovered that *OH can adsorb on the surface of ZnGa2O4 with an energy of 1.63 eV, which is within the optimum range for H2O2 generation. Interestingly, the O atom in *OH is bonded with Zn and Ga atoms (Fig. 5a). The bond length of Zn-O is 1.97 Å, and the bond length of Ga-O is 2.04 Å. The similar bond length confirms the formation of a dual-site (Zn-Ga) adsorption configuration. As a result, the water oxidation to H2O2 molecules is reasonably inferred at this Zn-Ga region with a dual-adsorption site. A detailed energy diagram of the reaction steps involved in the OH--mediated water oxidation pathway was shown in Figure S19. In addition, as shown in Figure S20, the distinct advantage of the HCO3-mediated pathway in promoting anodic H2O2 generation was also observed on some other anodes including F-doped tin oxide (FTO), FTO/WO3, and Toray TGP-H-060 carbon fiber paper (CFP). For example, the H2O2 FE of FTO, FTO/WO3, and CFP are 5%, 13%, and 9% in 0.5 M KHCO3. However, the H2O2 FE is below 0.5% for all three anodes in 0.5 M KOH.

Overall, on this ZnGa2O4 anode, H2O2 can be generated through either the HCO3--mediated reaction pathway or the OH--mediated reaction pathway (Fig. 5b). The former plays a critical role in boosting H2O2 FE. Meanwhile, DFT results indicate that the conversion of *HCO3 to *HCO4 relies on the dual-adsorption site (Ga-Ga) of ZnGa2O4. Furthermore, percarbonate species may undergo decomposition on the electrode surface, giving rise to *CO2 and*HO2 by breaking the –C–O– bond or *CO3 and *HO by breaking the -–O–O– bond (Fig. 5b). The latter causes a decrease in FE because the crucial intermediate HCO4- was eliminated. The theoretical studies indicate that the high H2O2 FE of ZnGa2O4 is related to the conversion of *HCO3 to *HCO4 at the dual-site, and to the intact peroxides on the surface of ZnGa2O4. Therefore, the FE is not only determined by the reaction selectivity but also influenced by the stability of the peroxy bond on the anode surface.

Next, the real-time H2O2 concentration was recorded when applying a potential of 2.7 V versus RHE to the anode (Figure S21). It is found that the H2O2 concentration increases linearly in the first 60 minutes and then the growth slows down. The H2O2 concentration reaches a plateau after 200 minutes owing to H2O2 disproportionation and electrodecomposition. After 300 min-electrolysis, the H2O2 concentration reaches ~22 mM. It is worth noting that such a concentration has met the requirement of applications such as the Fenton reaction (> 1 mM)42,60,61, water disinfection (>1 mM)41.

Discussion

In conclusion, a highly selective ZnGa2O4 anode was developed for H2O2 production by oxidizing water, delivering a high FE of 82% at a low overpotential of 540 mV, along with good stability. In this case, it is revealed that the H2O2 concentration plateau during continuous electrolysis up to 5 h is largely realted to homogeneous decomposition (disproportionation) instead of electro decomposition. Based on our experimental observations and the theoretical calculations, the H2O2 is formed on ZnGa2O4 through both the indirect and direct reaction routes. More importantly, the indirect route, mediated by the HCO3-/HCO4-, is the critical route for H2O2 production. ZnGa2O4 favors the adsorption of HCO3- at the dual Ga-Ga sites. The conversion of *HCO3 to *HCO4 on ZnGa2O4 is confirmed by the in situ ATR-FTIR spectra and the energy change in DFT results. Significantly, adsorbed *HCO4 was found to decompose into *CO2 and *O2H, and the latter would transform into H2O2. Additionally, the peroxy bond in H2O2 and HCO4- is stable on the ZnGa2O4 surface with and without HCO3- anions.

As well-known, the anodic H2O2 generation performance can be affected by the supporting electrolyte27,45,46,62. For this ZnGa2O4 anode, given the high FE in bicarbonate as well as the large current density in carbonate solution for anodic H2O2 generation, further study can be focused on optimizing the composition of electrolytes further to improve the FE of ZnGa2O4 for H2O2 production and to elucidate the reaction mechanism behind it.

Methods

Preparation of catalyst and electrodes

The ZnGa2O4 anode was designed for anodic H2O2 formation because of the following reasons. Firstly, it is important to avoid the decomposition effect of the catalyst itself on H2O2. Thus, some metal cations cannot be chosen. For example, catalysts that can decompose H2O2 into O229,52 (MnO2 and CoO) or catalysts containing Fe or Mn elements that can activate H2O2 into hydroxide radicals63 should be excluded. Secondly, to improve the selectivity of H2O2, competitive reactions such as oxygen evolution and the formation of hydroxyl radicals should be suppressed on the anode surface. The strength of oxygen chemisorption on transition metal (TM) ions should be taken into consideration when designing the catalysts for electrochemical water oxidation. Numerous efforts have revealed that the oxygen chemisorption strength on a metal surface is related to its electronic structure, i.e. the position of the metal’s d-band center relative to its Fermi level64,65,66,67. Those TM atoms such as Co, Ni, Fe, Mn featuring suitable chemisorption of oxygen on the catalyst surface were excluded because *OH can be easily dissociated into *O and finish the 4e-water oxidation pathway. Thirdly, according to the previous researches, the most reported anode materials for H2O2 production are those TM oxides containing cationic ions with closed electronic shell configurations, such as W6+ (5d0), Bi3+ (6s2), Zn2+ (3d10), Sn4+ (4d10). It is possible that the dominance of this configuration is related to the inert oxygen evolution activity of these metal oxides. Therefore, we designed ZnGa2O4 anode in which Zn and Ga have closed electronic shell configurations to investigate the anodic H2O2 generation performance. Besides, the good chemical stability of ZnGa2O4 in oxidative condition is also beneficial to 2e-WOR, which has been demonstrated in previous studies37,68,69,70.

The ZnGa2O4 microsphere was prepared according to a previous report with minor modifications37. Gallium nitrate hydrate and zinc acetate were dissolved in pure water (10 mL) with a molar ratio of 2:1. To obtain the flower-like structure consisting of nanosheets, the concentration of zinc precursor was optimized to 25 mM. Then 5 mL of ethylenediamine was added to the above solution and stirred at room temperature for 20 min. Next, the mixture was transferred to a 25 mL autoclave and heated at 200 °C for 16 h. After cooling down to room temperature, the sample was obtained by centrifugation and washed with deionized water and ethanol several times in sequence. Then the sample was dried at 60 °C overnight. After cleaning with ethanol three times, the carbon fiber cloth (Taiwan Tanneng, WOS1009) was dried at room temperature. Next, 300 mg ZnGa2O4 catalyst and 30 mg polytetrafluoroethylene were dispersed in 10 mL ethanol, followed by a sonication treatment for 20 min to form a highly dispersed mixture. Then the cleaned CC was placed on a hot plate (150 °C), and the ZnGa2O4 catalyst mixture was painted onto the CC by brushing, followed by a heat treatment at 350 °C for 30 min in Argon flow. The loading amount of ZnGa2O4 was about 20 mg cm−2.

Characterizations

Phase identification was conducted on a Rigaku SmartLab X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα irradiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) operation at 40 kV and 40 mA. X-Ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) characterizations of samples before and after electrolysis or Fenton reaction were obtained on a Thermo ESCALAB 250Xi spectrometer equipped with an anode of Al Kα radiation (1486.6 eV) X-ray sources. The obtained XPS data were calibrated by the C1s position (284.8 eV) before the data process. For the quantification of the formed H2O2 from anode under different biases, the concentration of H2O2 was quantified based on the spectrophotometric determination of I3−71. Firstly, solutions A and B were prepared for the quantification of H2O2 by I3− method. To prepare solution A, 33 g KI, 1.4 g KOH, and 0.1 g (NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O were dissolved in 500 mL distilled water. 10 g potassium hydrogen phthalate was dissolved in 500 mL distilled water as solution B. Solution A should be kept in the dark to inhibit the oxidation of I−. The pH of the sample solution was adjusted to 7 before the test. Then the sample solution, solutions A and B were mixed in equal volumes. After 5 min, the UV absorption spectrum of the mixture solution was recorded on Cary Series UV-Vis Spectrometer (Agilent Technologies). The accumulated concentration of H2O2 in the anolyte was quantified, based on which the faradaic efficiency and production rate are calculated. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) characterizations were performed on an FEI Quanta 400 microscope. The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and high-resolution TEM were conducted on a Philips Tecnai F20 instrument and a CM-120 microscope (Philips, 120 kV).

ATR-FTIR measurement

For the attenuated total reflectance Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR) test, a single Si crystal (diameter: 20 mm) was used as an ATR crystal. A high-sensitivity mercury calcium telluride (MCT) detector and optical path accessories with high luminous flux were required to detect the adsorption vibration signals. The spectral signal was collected by a Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS50). A rough Au film with good conductivity was deposited onto the ATR crystal to enhance the infrared absorption by means of the local electric field of the surface plasmon. In the three-electrode system, Pt wire was used as the counter electrode, and catalyst film on the Si crystal (coated with Au film) acts as the working electrode connected to the external circuit through a copper foil. A schematic representation of the in situ electrochemical cell for the ATR-FTIR test is shown in Figure S16. The data recorded at open circuit potential was used as the background. All the spectra were recorded in the range of 4000 ~900 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm–1 and averaged with 32 scans.

Electrochemical measurements

Electrochemical experiments in a three-electrode set-up were performed on a CHI 760E electrochemical station (CH Instruments, Inc., Shanghai). Potentials set against Ag/AgCl were converted to the RHE scale according to ERHE = EAg/AgCl + 0.197 + 0.059 × pH, and the pH values of electrolytes value were tested by a pH meter (FE28, Mettler Toledo, Switzerland). The conductivity of the electrolyte was measured with a conductivity meter (DDS-307A, Shanghai INESAScientific Instrument Co., Ltd., China). The water oxidation performance of anodes was evaluated in a two-compartment cell divided by a Nafion 117 membrane (DuPond Co.). A Pt foil and a Ag/AgCl electrode (in a Luggin capillary) were used as the counter, and reference electrode, respectively. The electrochemical tests were performed without iR-compensation. Both of the compartments of the H-cell were full with 2 M KHCO3 solution, and the electrolyte was stirred at a rate of 600 r.p.m. during the electrochemical test. After passing a particular amount of coulombs (depending on the applied potentials), 0.5 mL anolyte was taken out and the H2O2 concentration in it was quantified by the I3- method. For the cyclic electrochemical tests, the electrolyte was periodically replaced.

The overpotential is calculated as follows:

Eapplied is the potential applied to the anode during tests.

Evaluation on the electrodecomposition of H2O2 on the ZnGa2O4 anode

The standardized method for measuring the electrodecomposition (ED) of H2O2 on anodes during anodic H2O2 production has yet to be well established. Here, a current integration method, i.e. to compare the faradaic charge with and without H2O2 (known concentration) at the same applied potential, was used to evaluate the electrodecomposition of H2O2 on ZnGa2O4 anode51. Specifically, chronoamperometric courses of ZnGa2O4 anode at potentials (2.3, 2.5, 2.7 V vs. RHE) in 2 M KHCO3 solution with and without H2O2 (10 mM) were recorded (Figure S10). Then the total faradaic charge passed in solution with and without H2O2 addition was compared, and the difference between the two tests is assumed to be the charge corresponding to the oxidation of H2O2. Taking the analysis at 2.3 V vs. RHE as an example, the calculation details are shown below.

\({{H}_{2}{O}_{2}}_{{{{{{\rm{Accumulated}}}}}}}\) means the measured H2O2 generation rate (6.27 μmol cm−2 min−1 at 2.3 V vs. RHE in Fig. 2e). \({{FE}}_{{ED},{current\; intergration}}\) at 2.5 and 2.7 V vs. RHE are 0.047 and 0.059. The electro decomposition rate of H2O2 at 2.5 and 2.7 V vs. RHE in 2 M KHCO3 are calculated to be 0.42 and 0.77 μmol cm-2 min-1.

It should be noted that this method provides an overestimation of the role of H2O2 electro decomposition because the concentration of H2O2 added during the tests (10 mM) is higher than the concentration plateau observed in Fig. 3a. Such approximate evaluation of the electro decomposition of H2O2 can help to identify the main factors causing the decomposition of H2O2.

Theoretical calculations

The mechanism for H2O2 generation is studied by using VASP computational package7. Projector-augmented-wave method with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof GGA functional was used72. The electronic convergence limit was set to be 1 × 10−5 eV73. Optimization of atomic coordinates was considered to be converged when Hellmann–Feynman force was smaller than 1× 10−2 eV Å−1. The established slab of ZnGa2O4 is (311) facets with Zn and Ga atoms termination. Besides, the established slab of ZnO is (200) facets with Zn atoms termination. The established Ga2O3 slab is (020) facets with Ga atoms termination. Intermediate including *OH, *HCO3 and *HCO4 is separately placed on the top of the slab surface. The vacuum region is about 10 Å in height.

The surface termination for the DFT studies was determined based on the XRD pattern, the polycrystalline diffraction patterns, and the HRTEM images. We first choose the (311) facet because it is the strongest diffraction peak in the XRD pattern of the ZnGa2O4 catalyst, which indicates that (311) facets should widely exist in the crystals. This approach has been used in previous reports on electrocatalysts with a cubic spinel structure, where the theoretical calculations are based on the observed main peaks in the XRD pattern74,75,76. For example, a previous report (Nat. Catal. 2022, 5, 109-118) studied the Co2MnO4 (space group Fd\(\bar{3}\)m, a = 8.0866 Å), the DFT calculation was conducted based on the (311) surface (the dominant peak in the PXRD)75. Since (311) and (220) facets are also observed in the HRTEM images (Fig. 1d and S1c, d), it can be concluded that (220) and (311) facets widely exist in the prepared ZnGa2O4 catalyst. It is necessary to investigate the adsorption of reaction intermediates on both (311) and (220) facets. Finally, in the selected area electron diffraction pattern (Figure S1b), considering that the zone axis perpendicular to (311) and (220) facets is [\(\bar{1}\)12], (\(\bar{1}\)12) facet is also considered in our calculations.

Next, the conversion of *HCO3 to *HCO4 on these three facets was investigated. Here, by using the computational hydrogen electrode method to identify the conversion of bicarbonate to percarbonate is thermodynamically favorable or not. The influence of applied potential is considered via computational hydrogen electrode (CHE) method77,78. In this method, at standard condition, chemical potential of proton and electron is equals to that of a half of hydrogen gas (μ(H+ + e-) = 1/2 μ(H2)). The potential of the electrons is eU, where e is the elementary charge and U is the potential applied to the electrode.

The catalytic process on the surface is investigated by calculating the energy of intermediates during the process. The transfer of *HCO3 to *HCO4 should involve the following step:

Based on the above step, the computational change of energy of the intermediates adsorbed on the surface can be calculated according to the following method:

Where E*HCO4, E*HCO3, EH2, and EOH is the adsorption energy of HCO3, HCO4, H2, and OH, and U is the applied potential.

The Gibbs free energy changes of intermediates were calculated with zero-point energy, and entropy correction using the equation bellows:

Where, ZPE, T, and S correspond to zero-point energy, temperature, and entropy, respectively.

In the case of the (311) facet, the E*HCO4−E*HCO3 is calculated to be −1.00 eV, EH is −3.39 eV, EOH is −7.34 eV, U is 2.3 V. Therefore, ∆E is calculated to be −1.65 eV (E*HCO4−E*HCO3 + EH - EOH - 2eU).

The ZPE for HCO3 is 0.66 eV; ZPE for HCO4 is 0.80 eV; ZPE for H is 0.16 eV; ZPE for OH is 0.33 eV; ∆ZPE is −0.03 eV (0.80 eV–0.66 eV + 0.16 eV–0.33 eV = 0.03 eV). At 298 K, TS for HCO3 is 0.05 eV; TS for HCO4 is 0.14 eV; TS for H is 0.13 eV; TS for OH is 0.07 eV; therefore, T∆S is calculated to be 0.148 eV (0.14 eV–0.05 eV + 0.13 eV–0.07 eV = 0.15 eV). Therefore, ∆ZPE - T∆S is −0.18 eV.

When the temperature effect of enthalpy is considered, a correction of ΔH should be added79,80:

Where C*HCO4, C*HCO3, C*H2, and COH is the heat capacity with the unit of J K−1 mol−1. C*HCO4, C*HCO3, C*H2, and COH is 39.6, 30.2, 16.6, and 15.9 J K-1 mol-1, respectively, which are obtained by using the phonopy in VASP. The unit of J K-1 mol-1 is converted to eV by dividing 1.6E-19 and NA (6.02E23 mol-1). Finally, the correction of H(298 K) - H(0 K) is calculated to be 0.01 eV.

Therefore, at 298 K, the ∆G is calculated to be −1.82 eV (−1.65 eV − 0.18 eV + 0.01 eV) at the potential of 2.3 V versus RHE at 298 K. This negative value suggests that the transformation of *HCO3 to *HCO4 on the (311) facet is favorable at 2.3 V versus RHE at 298 K.

In the case of the (220) facet, the E*HCO4−E*HCO3 is 0.66 eV; EH is −3.39 eV; EOH is −7.34 eV; U is 2.3 V. Therefore, ∆E is calculated to be 0.01 eV (E*HCO4− E*HCO3 + EH–EOH- 2eU). The ZPE for HCO3 is 0.66 eV; ZPE for HCO4 is 0.80 eV; ZPE for H is 0.16 eV; ZPE for OH is 0.33 eV; ∆ZPE is −0.03 eV (0.80 eV- 0.66 eV + 0.16 eV–0.33 eV = 0.03 eV). At 298 K, TS for HCO3 is 0.05 eV; TS for HCO4 is 0.14 eV; TS for H is 0.13 eV; TS for OH is 0.07 eV; therefore, T∆S is 0.15 eV (0.14 eV–0.05 eV + 0.13 eV - 0.07 eV = 0.15 eV). Therefore, ∆ZPE–T∆S is −0.18 eV.

Therefore, ∆G is calculated to be −0.16 eV at the potential of 2.3 V versus RHE at 298 K. This negative value suggests that at 2.3 V versus RHE the transformation of *HCO3 to *HCO4 on (220) facet is favorable.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary information files. All other relevant data supporting the finding of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Tanev, P. T., Chibwe, M. & Pinnavaia, T. J. Titaniumcontaining mesoporous molecular sieves for catalytic oxidation of aromatic compounds. Nature 368, 321–323 (1994).

Lane, B. S. & Burgess, K. Metal-catalyzed epoxidations of alkenes with hydrogen peroxide. Chem. Rev. 103, 2457–2474 (2003).

McDonnell-Worth, C. J. & MacFarlane, D. R. Progress towards Direct Hydrogen Peroxide Fuel Cells (DHPFCs) as an Energy Storage Concept. Aust. J. Chem. 71, 781–788 (2018).

Ma, J., Choudhury, N. A. & Sahai, Y. A comprehensive review of direct borohydride fuel cells. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 14, 183–199 (2010).

Fan, Z., Kwon, Y.-H., Yang, X., Xu, W. & Wu, Z. In-situ production of hydrogen peroxide as oxidant for direct urea fuel cell. Energy Procedia 105, 1858–1863 (2017).

Kosaka, K. et al. Evaluation of the treatment performance of a multistage ozone/hydrogen peroxide process by decomposition by- products. Water Res. 35, 3587–3594 (2001).

Li, L., Hu, Z. & Yu, J. C. On-demand synthesis of H2O2 by water oxidation for sustainable resource production and organic pollutant degradation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 59, 20538–20544 (2020).

Li, L., Xiao, K., Wong, P. K., Hu, Z. & Yu, J. C. Hydrogen peroxide production from water oxidation on a CuWO4 anode in oxygen-deficient conditions for water decontamination. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 7878–7887 (2022).

Campos-Martin, J. M., Blanco-Brieva, G. & Fierro, J. L. Hydrogen peroxide synthesis: an outlook beyond the anthraquinone process. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 45, 6962–6984 (2006).

Ciriminna, R. et al. Hydrogen peroxide: a key chemical for today’s sustainable development. Chemsuschem 9, 3374–3381 (2016).

Siahrostami, S. et al. Enabling direct H2O2 production through rational electrocatalyst design. Nat. Mater. 12, 1137–1143 (2013).

Yang, S. et al. Toward the decentralized electrochemical production of H2O2: A focus on the catalysis. ACS Catal. 8, 4064–4081 (2018).

Jung, E., Shin, H., Hooch Antink, W., Sung, Y.-E. & Hyeon, T. Recent advances on electrochemical oxygen reduction to H2O2: Catalyst and cell design. ACS Energy Lett. 5, 1881–1892 (2020).

Shi, X., Back, S., Gill, T. M., Siahrostami, S. & Zheng, X. Electrochemical synthesis of H2O2 by two-electron water oxidation reaction. Chem 7, 38–63 (2020).

Samanta, C. Direct synthesis of hydrogen peroxide from hydrogen and oxygen: An overview of recent developments in the process. Appl. Catal., A 350, 133–149 (2008).

Li, F., Shao, Q., Hu, M., Chen, Y. & Huang, X. Hollow Pd−Sn nanocrystals for efficient direct H2O2 synthesis: The critical role of Sn on structure evolution and catalytic performance. ACS Catal. 8, 3418–3423 (2018).

Wilson, N. M. & Flaherty, D. W. Mechanism for the direct synthesis of H2O2 on Pd clusters: Heterolytic reaction pathways at the liquid-solid interface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 574–586 (2016).

Melchionna, M., Fornasiero, P. & Prato, M. The rise of hydrogen peroxide as the main product by metal-free catalysis in oxygen reductions. Adv. Mater. 31, e1802920 (2019).

Zhang, J., Zhang, H., Cheng, M. J. & Lu, Q. Tailoring the electrochemical production of H2O2: Strategies for the rational design of high-performance electrocatalysts. Small 16, 1902845 (2020).

Li, L. et al. Tailoring selectivity of electrochemical hydrogen peroxide generation by tunable pyrrolic‐nitrogen‐carbon. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 2000789 (2020).

Zhang, Q. et al. Highly efficient electrosynthesis of hydrogen peroxide on a superhydrophobic three-phase interface by natural air diffusion. Nat. Commun. 11, 1731 (2020).

Pérez, J. F. et al. Improving the efficiency of carbon cloth for the electrogeneration of H2O2: Role of polytetrafluoroethylene and carbon black loading. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 56, 12588–12595 (2017).

Cao, P. et al. Durable and selective electrochemical H2O2 synthesis under a large current enabled by the cathode with highly hydrophobic three-phase architecture. ACS Catal. 11, 13797–13808 (2021).

Park, S. Y. et al. CaSnO3: An electrocatalyst for two-electron water oxidation reaction to form H2O2. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 352–357 (2018).

Kelly, S. et al. ZnO as an active and selective catalyst for electrochemical water oxidation to hydrogen peroxide. ACS Catal. 9, 4593–4599 (2019).

Miyase, Y., Miseki, Y., Gunji, T. & Sayama, K. Efficient H2O2 production via H2O oxidation on an anode modified with sb‐containing mixed metal oxides. ChemElectroChem 7, 2448–2455 (2020).

Xia, C. et al. Confined local oxygen gas promotes electrochemical water oxidation to hydrogen peroxide. Nat. Catal. 3, 125–134 (2020).

Li, L. et al. Direct hydrogen peroxide synthesis on a Sn-doped CuWO4/Sn anode and an air-breathing cathode. Chem. Mater. 34, 63–71 (2022).

Fuku, K., Miyase, Y., Miseki, Y., Gunji, T. & Sayama, K. Enhanced oxidative hydrogen peroxide production on conducting glass anodes modified with metal oxides. Chemistryselect 1, 5721–5726 (2016).

Gill, T. M., Vallez, L. & Zheng, X. The role of bicarbonate-based electrolytes in H2O2 production through two-electron water oxidation. ACS Energy Lett., 2854–2862, (2021).

Mavrikis, S., Perry, S. C., Leung, P. K., Wang, L. & Ponce de León, C. Recent advances in electrochemical water oxidation to produce hydrogen peroxide: a mechanistic perspective. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 9, 76–91 (2021).

Kuttassery, F., Sebastian, A., Mathew, S., Tachibana, H. & Inoue, H. Promotive effect of bicarbonate ion on two-electron water oxidation to form H2O2 catalyzed by aluminum porphyrins. ChemSusChem 12, 1939–1948 (2019).

Mavrikis, S., Göltz, M., Rosiwal, S., Wang, L., & Ponce de León, C. Boron-doped diamond electrocatalyst for enhanced anodic H2O2 production. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 3, 3169–3173 (2020).

Zhang, C. et al. High yield electrosynthesis of hydrogen peroxide from water using electrospun CaSnO3@Carbon fiber membrane catalysts with abundant oxygen vacancy. Adv. Func. Mater. 31, 2100099 (2021).

Xue, S. G. et al. Selective electrocatalytic water oxidation to produce H2O2 using a C,N codoped TiO2 electrode in an acidic electrolyte. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 4423–4431 (2020).

Hall, S. B., Khudaisha, E. A. & Hartb, A. L. Electrochemical oxidation of hydrogen peroxide at platinum electrodes. Part 1. An adsorption-controlled mechanism. Electrochim. Acta 43, 579–588 (1998).

Liu, Q. et al. Single-crystalline, ultrathin ZnGa2O4 nanosheet scaffolds to promote photocatalytic activity in CO2 reduction into methane. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6, 2356–2361 (2014).

Shi, X. J. et al. Understanding activity trends in electrochemical water oxidation to form hydrogen peroxide. Nat. Commun. 8, 701 (2017).

Mavrikis, S. et al. Effective hydrogen peroxide production from electrochemical water oxidation. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 2369–2377 (2021).

Wang, Y., Lian, X., Zhou, Y., Guo, W. & He, H. Synthesis and characterization of Sb2O3: a stable electrocatalyst for efficient H2O2 production and accumulation and effective degradation of dyes. New J. Chem. 45, 8958–8964 (2021).

Imlay, J. A. & Linn, S. Bimodal pattern of killing of DNA-repair-defective or anoxically grown Escherichia coli by hydrogen peroxide. J. Bacteriol. 166, 519–527 (1986).

Li, H. et al. Oxygen vacancy associated surface fenton chemistry: surface structure dependent hydroxyl radicals generation and substrate-dependent reactivity. Environ. Sci Technol. 51, 5685–5694 (2017).

Zeng, H. et al. pH-independent production of hydroxyl radical from atomic H*-mediated electrocatalytic H2O2 reduction: a green fenton process without byproducts. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 14725–14731 (2020).

Hou, X. et al. Hydroxylamine promoted goethite surface fenton degradation of organic pollutants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 5118–5126 (2017).

Mavrikis, S., Goltz, M., Rosiwal, S., Wang, L. & Ponce de Leon, C. Carbonate-induced electrosynthesis of hydrogen peroxide via two-electron water oxidation. ChemSusChem 15, e202102137 (2022).

Pangotra, D. et al. Anodic production of hydrogen peroxide using commercial carbon materials. Appl. Catal. B 303, 120848 (2022).

Fuku, K. & Sayama, K. Efficient oxidative hydrogen peroxide production and accumulation in photoelectrochemical water splitting using a tungsten trioxide/bismuth vanadate photoanode. Chem. Commun. 52, 5406–5409 (2016).

Kormann, C., Bahnemann, D. W. & Hoffmann, M. R. Photocatalytic production of H2O2 and organic peroxides in aqueous suspensions of TiO2, ZnO, and desert sand. Environ. Sel. Technol. 22, 798–806 (1988).

Hoffman, A. J., Carraway, E. R. & Hoffmann, M. R. Photocatalytic production of H202 and organic peroxides on quantum-sized semiconductor colloids. Environ. Sci. Technol. 28, 776–785 (1994).

Moon, G.-h, Kim, W., Bokare, A. D., Sung, N.-e & Choi, W. Solar production of H2O2 on reduced graphene oxide–TiO2 hybrid photocatalysts consisting of earth-abundant elements only. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 4023–4028 (2014).

Gill, T. M., Vallez, L. & Zheng, X. The role of bicarbonate-based electrolytes in H2O2 production through two-electron water oxidation. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 2854–2862 (2021).

Izgorodin, A., Izgorodina, E. & MacFarlane, D. R. Low overpotential water oxidation to hydrogen peroxide on a MnOx catalyst. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 9496–9501 (2012).

Nadar, A. et al. Evaluating the reactivity of BiVO4 surfaces for efficient electrocatalytic H2O2 production: a combined experimental and computational study. J. Phys. Chem. C 124, 4152–4161 (2020).

Lee, W. T., Xu, S., Dickie, D. A. & Smith, J. M. A robust Mn catalyst for H2O2 disproportionation in aqueous solution. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 3867–3873 (2013).

Richardson, D. E., Yao, H., Frank, K. M. & Bennett, D. A. Equilibria, kinetics, and mechanism in the bicarbonate activation of hydrogen peroxide: oxidation of sulfides by peroxymonocarbonate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 1729–1739 (2000).

Davis, A. R. & Oliver, B. G. A vibrational-spectroscopic study of the species present in the CO2-H2O system. J. Solution Chem. 1, 329–339 (1972).

GiguPrc, P. A. & Lemaire, D. Spectroscopic study of the hydrogen peroxide derivatives and percarbonates KHCO4 and K2C2O6. Canad. J. Chem. 50, 1472 (1972).

Jones, D. P. & William P. Griffith. Alkali-metal Peroxocarbonates, M2[CO3]·nH2O2, M2[C2O6], M[HCO4]·nH2O, and Li2[CO4]H2O. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans., 2526–2532, (1980).

Siahrostami, S., Li, G. L., Viswanathan, V. & Norskov, J. K. One- or two-electron water oxidation, hydroxyl radical, or H2O2 evolution. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 1157–1160 (2017).

Zhan, S. et al. Efficient Fenton-like process for pollutant removal in electron-rich/poor reaction sites induced by surface oxygen vacancy over cobalt-zinc oxides. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 8333–8343 (2020).

Hou, X. et al. Hydroxylamine promoted goethite surface fenton degradation of organic pollutants. Environ. Sci Technol. 51, 5118–5126 (2017).

Gill, T. M., Vallez, L. & Zheng, X. Enhancing electrochemical water oxidation toward H2O2 via carbonaceous electrolyte engineering. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 4, 12429–12435 (2021).

Wang, G. et al. Removal of norfloxacin by surface Fenton system (MnFe2O4/H2O2): Kinetics, mechanism and degradation pathway. Chem. Eng. J. 351, 747–755 (2018).

Rossmeisl, J., Qu, Z. W., Zhu, H., Kroes, G. J. & Nørskov, J. K. Electrolysis of water on oxide surfaces. J. Electroanal. Chem. 607, 83–89 (2007).

Burke, M. S., Enman, L. J., Batchellor, A. S., Zou, S. & Boettcher, S. W. Oxygen evolution reaction electrocatalysis on transition metal oxides and (Oxy)hydroxides: Activity trends and design principles. Chem. Mater. 27, 7549–7558 (2015).

Man, I. C. et al. Universality in oxygen evolution electrocatalysis on oxide surfaces. ChemCatChem 3, 1159–1165 (2011).

Hong, W. T. et al. Toward the rational design of non-precious transition metal oxides for oxygen electrocatalysis. Energy Environ. Sci. 8, 1404–1427 (2015).

Xinnian, Z. et al. Photocatalytic decomposition of benzene by porous nanocrystalline ZnGa2O4 with a high surface area. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 5947–5951 (2009).

Yan, S. C. et al. A room-temperature reactive-template route to mesoporous ZnGa2O4 with improved photocatalytic activity in reduction of CO2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 49, 6400–6404 (2010).

Kumagai, N., Ni, L. & Irie, H. A visible-light-sensitive water splitting photocatalyst composed of Rh3+ in a 4d6 electronic configuration, Rh3+-doped ZnGa2O4. Chem. Commun. 47, 1884–1886 (2011).

Klassen, N. V., Marchlngton, D. & McGowan, H. C. E. H2O2 determination by the I3- method and by KMnO4 titration. Anal. Chem. 66, 2921–2925 (1994).

Hu, Z. et al. Cu(In,Ga)Se2 for selective and efficient photoelectrochemical conversion of CO2 into CO. J. Catal. 384, 88–95 (2020).

Bachhuber, F. et al. Van der Waals interactions in selected allotropes of phosphorus. Z. Kristallogr. - Cryst. Mater. 230, 107–115 (2015).

Lee, J. et al. Electrochemical behavior of the flower-shaped CoMn2O4 spinel structure assembled for effective HER from water splitting. Electrochim. Acta 379, 138168 (2021).

Li, A. et al. Enhancing the stability of cobalt spinel oxide towards sustainable oxygen evolution in acid. Nat. Catal. 5, 109–118 (2022).

Liu, Q. et al. Ambient ammonia synthesis via electrochemical reduction of nitrate enabled by NiCo2O4 nanowire array. Small 18, e2106961 (2022).

Jiao, Y., Zheng, Y., Jaroniec, M. & Qiao, S. Z. Origin of the electrocatalytic oxygen reduction activity of graphene-based catalysts: a roadmap to achieve the best performance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 4394–4403 (2014).

Gu, Y. et al. Electronic structure tuning in Ni3FeN/r-GO aerogel toward bifunctional electrocatalyst for overall water splitting. ACS Nano 12, 245–253 (2018).

Duan, H. et al. High-performance Rh2P electrocatalyst for efficient water splitting. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 5494–5502 (2017).

Zhang, W. & Xiao, Y. Mechanism of electrocatalytically active precious metal (Ni, Pd, Pt, and Ru) complexes in the graphene basal plane for ORR applications in novel fuel cells. Energy Fuels 34, 2425–2434 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, Sun Yat-sen University, China (22lgqb23, Z.H.), the Guangzhou Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation, China (202201011695, Z.H.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51902357, Z.H.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U22A20402, 21936003, L.Z.), the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (14304019, J.C.Y.). The Hong Kong Ph.D. Fellowship Scheme (PF17−10186, L.L.). Theoretical calculations were supported by the National Supercomputer Center in Guangzhou and National Supercomputing Center in Shenzhen (Shenzhen Cloud Computing Center).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.L., Z.H., and J.C.Y. conceived the project and designed the experiments. L.L. prepared the anode and tested the performance. Y.K. and S.C. conducted the ATR-FTIR experiments. Z.H. performed the theoretical study. L.L., Z.H., L.Y., and L.X. analyzed the data. L.L., Z.H., Y.K., L.Z., and J.C.Y. wrote the manuscript. J.C.Y., Z.H., and L.Z. supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Sotirios Mavrikis, Luciana Vieira, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, L., Hu, Z., Kang, Y. et al. Electrochemical generation of hydrogen peroxide from a zinc gallium oxide anode with dual active sites. Nat Commun 14, 1890 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-37007-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-37007-9

This article is cited by

-

Internal hydrogen-bond enhanced two-electron oxygen reduction reaction for π-d conjugated metal-organic framework to H2O2 synthesis

Nature Communications (2025)

-

High H2O2 production in membrane-free electrolyzer via anodic bubble shielding towards robust rural disinfection

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Electro-driven residual-free approach for removal of antibiotic resistance genes

Nature Water (2024)

-

Crystal OH mediating pathway for hydrogen peroxide production via two-electron water oxidation in non-carbonate electrolytes

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Host-guest-induced electronic state triggers two-electron oxygen reduction electrocatalysis

Nature Communications (2024)