Abstract

Narrow bandwidths are a general bottleneck for applications relying on passive, linear, subwavelength resonators. In the past decades, several efforts have been devoted to overcoming this challenge, broadening the bandwidth of small resonators by the means of analog non-Foster matching networks for radiators, antennas and metamaterials. However, most non-Foster approaches present challenges in terms of tunability, stability and power limitations. Here, by tuning a subwavelength acoustic transducer with digital non-Foster-inspired electronics, we demonstrate five-fold bandwidth enhancement compared to conventional analog non-Foster matching. Long-distance transmission over airborne acoustic channels, with approximately three orders of magnitude increase in power level, validates the performance of the proposed approach. We also demonstrate convenient reconfigurability of our non-Foster-inspired electronics. This implementation provides a viable solution to enhance the bandwidth of sub-wavelength resonance-based systems, extendable to the electromagnetic domain, and enables the practical implementation of airborne and underwater acoustic radiators.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Resonance-based systems, including acoustic radiators, electromagnetic antennas, and metamaterials, suffer from a well-known trade-off between bandwidth and size1, because of passivity and causality constraints2,3. A trade-off between efficiency, bandwidth, and electrical size of resonance-based systems plagues the implementation of many devices and technologies. In the context of compact acoustic radiators and electromagnetic antennas, the well-established trade-off between bandwidth and size is known as Chu’s limit4,5. Similarly, a general constraint between the operational bandwidth and the device size exists in acoustic and microwave metamaterials6. These bounds are the key benchmarks for resonance-based system design6,7. Widening the bandwidth beyond these bounds is possible only by breaking one or more of the underlying assumptions on time invariance, passivity, and linearity3,4. Temporal modulations of antenna elements or the connected matching circuitry have been proven to be effective in this context1,8,9. Breaking passivity to achieve a wide bandwidth was recently implemented by loading small antennas with analog non-Foster circuitry10,11, commonly implemented by an analog negative impedance converter that violates Foster’s reactance theorem12,13. Recently, this circuitry was used to enhance acoustic radiation from a piezoelectric transducer, which successfully surpassed the acoustic Chu’s limit4. Similar approaches enable parity-time symmetric electronics12,13 and acoustics14,15. Analog non-Foster circuitry has also been explored for broadband microwave generation16, robust wireless power transfer17,18, nonreciprocal transmission of microwave acoustic waves19, as well as broadband unidirectional acoustic devices20.

However, analog non-Foster circuits are limited in their available parameter space and hence are unable to engineer arbitrary frequency dispersion and provide real-time reconfigurability. They can be configured in a discrete and constrained manner due to the limited choice of available circuit components. Once the circuit structure is fixed, the negative impedance cannot be adjusted in operation or be altered. Delicate manual tuning of variable circuit components may discourage their broad applicability12,18. In addition, power handling21 and stability limitations22,23 of analog non-Foster circuits hinder the implementation of a broad range of metamaterial devices in which bandwidth is important. These shortcomings plague a diverse range of practical applications.

In the past decades, several research prospects have been put forward to overcome these challenges. The concept of digital metamaterials has been introduced to provide metamaterials with robust reconfigurability and modularity24. Active control can add degrees of freedom to tune the metamaterial parameters25,26 and achieve gate-tunable negative refraction27. These features can be successfully used to realize broadband sound absorbers26 or sound barriers28. Recent breakthroughs have also been made in the context of programmable mechanical metamaterials29,30. Virtualized metamaterials allow us to freely reconfigure the frequency dispersion (FD) using a digital representation of tunability solely based on software modifications31. The pioneering digital non-Foster circuits for realizing negative impedance are based on open-loop control, which in fact mimic ordinary analogy non-foster systems by specific functions of digital filters32,33,34,35,36. The concept of using additional sources that simultaneously implement non-Foster cancellation and negative resistance was introduced37,38. A high energy-injection switch-mode amplifier has been shown to realize a negative inductance39 and a nonlinear negative resistance40, showcasing low loss compared to analog operational amplifiers (op-amps)17,41.

In this work, inspired by these works, we demonstrate the realization of digital non-Foster electronics with tailored and reconfigurable FD. Our digital non-Foster-inspired circuitry enables a broad control over the amplitude-phase relation between the terminal voltage and current, which can be set arbitrarily, hence synthesizing in real-time an equivalent negative resistance, negative inductance or negative capacitance with on-demand FD. A self-adaptive proportional-resonant (PR) controller42,43, which is pre-programed in a digital microprocessor, can actively select the optimal control characteristics based on the operating frequency to ensure excellent transient response and real-time tunability. More importantly, this solution successfully circumvents inherent instabilities of non-Foster circuits by ensuring that the poles of the characteristic equation remain in the stable portion of the complex plane for a wide range of control parameters. As an additional advantage, the op-amps used in analog non-Foster circuits have a limited range of power handling, while the use of switch-mode electronics may provide a leap forward also in power levels. Based on this platform, we demonstrate that loading a low-resonance-frequency electroacoustic transmitter with our digital non-Foster-inspired electronics supports broadband high-power acoustic radiation. Our simulation and experimental results show that the proposed digital non-Foster electronics offer flexibly engineered FD, enhancing the operation bandwidth by over five times compared to a matching network based on analog non-Foster electronics. In experiments, we apply the digital non-Foster electronic network to demonstrate long-haul image transmission over airborne acoustic channels, validating the stability of the proposed system, and demonstrating its flexibility, reconfigurability, and real-time tunability.

Results

Digital non-Foster-inspired electronics

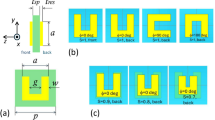

The key element of conventional analog non-Foster circuitry (Fig. 1a) is the op-amp. Since the supply voltage is limited to tens of volts in analog devices, this topology is impractical for high-voltage scenarios. The op-amp realizes a negative impedance, crucial for the classic implementation of non-Foster matching circuitry9 (Fig. 1b). However, constrained by the commercially available component values and tolerances of passive analog RLC elements, the negative impedance attainable with analog non-Foster circuits cannot span a continuous range, and their tuning often depends on tedious circuit component replacements. For example, capacitance specifications for common passive capacitor packages only include 100 pF, 220 pF, 3.3nF, 6.8nF, etc., with the tolerances of up to ±20%44. Therefore, analog non-Foster matching networks cannot synthesize arbitrary FD, facing challenges with discretized parameter space and complicated manual tuning by tedious circuit component replacements. Power limitations and limited dispersion engineering leaves the full bandwidth-enhancement potential of non-Foster matching untapped.

a Analog non-Foster circuitry using op-amps. By changing the passive analog loads Z, the negative impedance ZA can be realized. b Diagram of negative impedances with the analogue non-Foster circuit by varying discrete analog components -Z (-L or -C). c The proposed digital non-Foster-inspired electronics composed of a digital controller and switch-mode circuit adopts a current closed-loop feedback control where iref is calculated by a reference negative impedance. The software-defined implementation circumvents the inherent limited selection of analog passive elements in analog non-Foster circuits, and enables arbitrary FD and real-time tunability. d Actively regulated amplitude-phase relation between \({{{{{{\rm{U}}}}}}}_{{{{{{\rm{o}}}}}}}\) and \({{{{{{\rm{I}}}}}}}_{{{{{{\rm{o}}}}}}}\), which can continuously realize an equivalent negative resistance RD(ω), negative inductance LD(ω), or negative capacitance CD(ω).

Several efforts have been devoted to overcome these obstacles. Digital non-Foster electronics (Fig. 1c) enables opportunities in this context. The transition from analog to digital circuits provides more degrees of freedom in the reconfiguration and tunability of equivalent negative impedance over a wide parameter range31. Digital microprocessors allow operations exempt from delicate manual tuning (i.e. change the circuit RLC elements to tune the negative impedance set by analogue nonfoster circuits), altering the negative impedance reference and controller parameters on-demand through software-defined programming. Meanwhile, switch-mode electronics can lead to a leap in available power levels40,41. In stark contrast with op-amp-based analog non-Foster electronics, the proposed digital non-Foster-inspired electronics is characterized by arbitrary FD with equivalent negative resistance and inductance/capacitance, exploiting a feedback control to actively configure the amplitude-phase relation of the terminal output voltage uo and current io (Fig. 1d) as necessary.

Theoretical analysis of digital non-Foster-inspired electronics

A common electroacoustic transmitter, typically operating near a resonance, supports a high-quality factor with limited operational bandwidth45. Here, we consider a transducer whose input terminal impedance shows a strong frequency dependence due to eddy currents. By loading it with the proposed digital non-Foster circuit, we demonstrate high-power acoustic broadband radiation. The transducer bandwidth is defined by the half-power level of the acoustic radiation46. The acoustic power Par can be calculated using47

where VD is volume velocity varying with the transducer input voltage, and Zrad is the acoustic radiation impedance. The frequencies fl and fh are the half-power frequencies, thereby determining the bandwidth ∆f. According to the overall system impedance model (Fig. 2a), when the transducer is loaded with the digital non-Foster circuit, VD can be derived as

where the total impedance ZD (ω) consists of an inductive component LD(ω) and a resistive component RD(ω) (see Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). The eddy current impedance \({{{\mbox{Z}}}}_{{{\mbox{E}}}} ^{{\prime}}(\omega )\) comprises the frequency-dependent elements \({R}_{{{\mbox{E}}}}^{\hbox{'}}(\omega )\) and LE(ω), which can be modeled as

where Lex, p and q are model parameters48.

a The overall system impedance model diagram. LD(ω) and RD(ω) at the output terminal impedance of non-Foster circuit. In the ideal lossless analog non-Foster circuit, LD(ω) is independent of frequency and RD(ω) is equal to zero. In our digital non-Foster-inspired circuit, LD(ω) or RD(ω) vary with frequency, tracking the transducer dispersion. The rest of the circuit model shows the electroacoustic transducer, with its electrical part, mechanical part and acoustic part. b Transducer bandwidth analysis by the analog circuit model after impedance matching using different configurations of LD(ω) and RD(ω). The entire curved surface represents the bandwidth enhancement without FD. The outlined black curve represents the bandwidth enhancement when RD(ω) is equal to zero. Herein, p4 is the maximum bandwidth enhancement that could be achieved4. p2 is the maximum bandwidth enhancement on the black surface. p1 is the bandwidth improvement when RD(ω) and LD(ω) completely offset \({R}_{{{\mbox{E}}}}^{\hbox{`}}(\omega )\) and LE(ω), respectively. p3 is the bandwidth improvement when only LD(ω) is offset by LE(ω) and RD(ω) is equal to zero. c Negative impedance characteristics of analog non-Foster and digital non-Foster-inspired electronics and the overall system impedance after impedance matching. d Acoustic power curves derived by loading the transducer with analog non-Foster and digital non-Foster-inspired electronics, respectively.

For a low-frequency transducer, the impedance of the mechanical part is much smaller than the electrical clamped impedance at frequencies far from the resonance45. Moreover, as the frequency ω goes up, the eddy current impedance \({Z}_{{{\mbox{E}}}}^{\hbox{'}}(\omega )\) significantly increases and it becomes the main component of the transducer impedance. More eddy losses will further reduce the acoustic power. This results in a reduction in radiation efficiency and considerably limits the operational bandwidth.

We now explore the relationship between ZD(ω) and ∆f to demonstrate the necessity of utilizing digital non-Foster electronics with arbitrary FD to broaden the high-power transducer bandwidth (Fig. 2b). The outlined black curve shows the limited improvement of conventional analog non-Foster electronics without FD engineering on the bandwidth when RD is equal to zero. Under this circumstance, the realizable bandwidth enhancement is represented by p44. Complete cancellation of LE(ω) (p3 in Fig. 2b) using the proposed negative impedance achieves a bandwidth enhancement. However, it is still limited by the eddy current loss resistance \({R}_{{{\mbox{E}}}}^{\hbox{'}}(\omega )\), which can be seen by the significant difference in bandwidth enhancement between p2 and p4 in Fig. 2b. Both \({R}_{{{\mbox{E}}}}^{\hbox{'}}(\omega )\) and LE(ω) vary significantly with frequency. Cancelling out \({R}_{{{\mbox{E}}}}^{\hbox{'}}(\omega )\) and LE(ω) over a broad frequency range, p1 further broadens the bandwidth based on the configuration p2. Accordingly, the proposed digital non-Foster element can overcome the performance challenges of conventional analog non-Foster circuits and broaden the operational bandwidth.

Figure 2c highlights the difference between non-Foster electronics with and without FD. The proposed digital non-Foster-inspired electronics can offset \({R}_{{{\mbox{E}}}}^{\hbox{'}}(\omega )\) and LE(ω) across a much larger bandwidth than the analog circuitry. The total resistance of the circuit is almost constant, while the reactance is almost eliminated across a wide bandwidth. The acoustic radiated power for both the proposed non-Foster electronics with and without FD are shown in Fig. 2d. Similar to our analytical calculations (p1 and p4) in Fig. 2b, the bandwidth expansion of the proposed digital non-Foster electronics with FD is over five times larger than the analog scenario.

Implementation of digital non-Foster-inspired electronics

The general structure diagram (Fig. 3a) and software control (Fig. 3b) jointly ensure the functionality of the digital non-Foster-inspired electronics. Its features are rooted in the fact that the amplitude-phase relation between the terminal output voltage of our non-Foster-inspired circuit uo and the terminal current io can be flexibly adjusted according to the negative impedance reference Zref through a current closed-loop feedback control, ultimately providing the desired dispersion of the terminal impedance ZD.

a General structure diagram of the digital non-Foster-inspired electronics. The proposed electronics consists of the signal stage and the power stage. The signal stage contains the signal conditioning (sensors), signal sampling (ADC), DSP, signal output (gate driver). The amplitude-phase relation of the reference current iref and the reference output voltage uref of the proposed circuit is determined by setting the negative impedance reference Zref into the DSP. The power stage includes a DC source, a H-bridge with four SiC MOSFETs (S1 ~ S4), and a LC filter formed by inductor Ls and capacitor Cs. b The control program flowchart in DSP, including initializing peripherals, eCAP ISR for the operating frequency fs calculation and timer ISR for control signal generation. c Waveform schematic of the reference voltage uref, the reference current iref, and the output current io before the usage of self-adaptive PR closed-loop feedback control. d The output signal uS1 ~ uS4 of DSP, which is used to drive the behavior of the switch-mode electronics S1 ~ S4. e Output voltage waveform schematic of H-bridge uAB and LC filter uo. f Waveform schematic of uref, iref, and io after closed-loop control.

By loading the electroacoustic transducer with the proposed digital non-Foster-inspired electronics (Fig. 3a), the power amplifier output voltage us and current io are first converted by the sensors-based signal conditioning circuit into the voltage signals, which meet the input voltage range of the analog-digital conversion (ADC) sampling, and ultimately are supplied to the digital signal processor (DSP).

After initializing peripherals, the DSP remains in a waiting state until the eCAP interrupt service routine (ISR) or the timer ISR occurs (Fig. 3b). The eCAP ISR completes the calculation of operating frequency fs by detecting the rising edges and falling edges. In the timer ISR, the reference current iref is first calculated, which is equal to the power amplifier voltage us divided by a target negative impedance Zref plus the transducer impedance ZT. Before the self-adaptive PR controller is introduced, the measured current io has a significant deviation from iref (Fig. 3c). Thereafter, the adaptive PR controller is used to minimize the sinusoidal steady-state errors by a large gain, so that the target negative impedance can be realized. This is achieved by comparing the controller output signal with the triangular carrier wave to generate the pulse width modulation (PWM) signals to control S1 ~ S4 (Fig. 3d)49. By setting the negative impedance reference Zref into the DSP, the output behavior of the DSP is then established through the current closed-loop feedback control.

The gate driver amplifies the DSP output signal and drives the action of H-bridge converter (Fig. 3e). By the self-adaptive PR approach, our proposed digital non-Foster-inspired circuit provides feedback control on the voltage-current output characteristics (Fig. 3f), which can stably exhibit an equivalent negative impedance at an arbitrary operating frequency fs, but also has a fast dynamic performance. Compared with analog non-Foster circuits that are prone to instabilities4,50, the proposed digital non-Foster circuit has a wider stability range (see Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2), because of the adaptive PR controller, which can only be implemented digitally51 (see Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Fig. 3). The desired amplitude-phase relationship between uo and io can be then achieved to match the required FD to broaden the operational bandwidth.

Experimental verification

Based on the general structure diagram (Fig. 3a), Fig. 4a illustrates the hardware implementation of digital non-Foster-inspired electronics. The part numbers or values of the main components is shown (Supplementary Tables 1-3). We connected the digital non-Foster-inspired circuit to the electroacoustic transducer to verify the bandwidth-enhancement performance (Fig. 4b). Here, a laser sensor was used to measure the vibration speed of the transducer, which is then converted into the corresponding SPL (see Supplementary Note 4 and Supplementary Fig. 4). An oscilloscope was used to measure the voltage and current waveforms in real time, while the power analyzer quantified the equivalent frequency-dependent negative resistance and inductance, e.g., RD(ω) and LD(ω).

a Photograph of the proposed digital non-Foster-inspired circuitry, which consists of four SiC MOSFETs (S1 ~ S4), passive elements (capacitors CDC and CAC, LC filter Ls and Cs), and the signal processing setup, which includes gate drivers, a DSP, a DC/DC module, ADC, V (voltage) and I (current) sensors. b Photograph of the experimental setup. The laser sensor, oscilloscope and power analyzer are used for measurement and recording of experimental data. The power amplifier voltage us is generated by a power amplifier and controlled by a signal generator. UDC is provided by a DC source. The rest include an auxiliary power supplier (APS), a personal computer (PC) and an electrical insulation transformer. c Negative resistance and inductance with or without FD synthesized by the designed digital non-Foster-inspired circuit, with their respective negative impedance characteristics characterized by the power analyzer. d Comparison of the sound pressure level (SPL) curves under different impedance matching approaches.

Due to the programmable control, the designed circuit can synthesize a wide range of equivalent impedance values. The steady-state impedance of both scenarios, with and without FD, are shown in Fig. 4c. As expected, the negative impedance provided by the digital non-Foster-inspired circuit is able to offset \({R}_{{{\mbox{E}}}}^{\hbox{`}}(\omega )\) and LE(ω) over a broad bandwidth. When the designed circuit presents a frequency-independent resistance and inductance like in conventional analog non-Foster electronics, RD(ω) and LD(ω) are constant and the corresponding bandwidth shrinks. Please note that conventional analog non-Foster circuits cannot realize the presented negative impedance characteristics here, due to limited power handling of the op-amps. Therefore, the designed circuit has great versatility, even without considering its FD engineering features. The impedance error between theoretical analysis and practical implementation is shown (Supplementary Note 5 and Supplementary Fig. 5).

Figure 4d shows the bandwidth expansion of the transducer under different negative impedance matching approaches. In Fig. 4d, the passive matching using conventional Foster components is shown4,45. Here, the total capacitance value is equal to 1000 μF, which is used to compensate the eddy current inductance of the acoustic radiator. The achieved resonant frequency is 50.98 Hz with a bandwidth of approximately 137 Hz. After offsetting the eddy current impedance \({Z}_{{{\mbox{E}}}}^{\hbox{`}}(\omega )\) via the proposed digital non-Foster circuit, the system bandwidth is more than five times larger than the one of conventional analog non-Foster matching, and about eight times the one of passive matching.

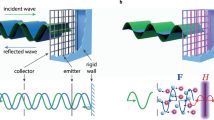

Scenarios for high-power broadband acoustic radiation

The bandwidth expansion realized by the digital non-Foster electronics can synthesize negative resistance and inductance with engineered FD. Its enhanced performance benefits from self-adaptive reconfigurability and real-time control. In order to enhance the tunability to different frequency regimes, the amplitude- and phase- frequency characteristics of the PR controller are divided into several intervals (Fig. 5a). The controller can automatically capture fs and alter the controller parameters.

a Amplitude-frequency and phase-frequency curves of the self-adaptive PR controller. b Transient response of the digital non-Foster-inspired circuit during frequency transition. The yellow curve indicates terminal voltage uo of the digital non-Foster circuit, while the blue one is the output current io. Here, uo and io are set to associated reference directions. The control signals of the switch devices S1, S3 are shown at the bottom. c Image transmission experiment over airborne acoustic channels. Transmitted image of the self-made Hunan University photo with a spatial resolution of 62 × 175 pixels. The transmitter is completed by the electroacoustic transducer fed through the designed digital non-Foster-inspired circuit, while the receiver is an acoustic sensor. The receiver node is installed to an open playground at a distance of approximately 60 meters from the transmission node, which minimized the effect of sound reflection, as well as environmental noises in reception. The transmitted and received images under different matching approaches are shown for comparison.

Figure 5b shows the transient characteristics for different frequency spans. When fs changes, the proposed digital non-Foster circuit can be quickly stabilized and the transient process lasts only two or three cycles, which can be further optimized to approximately within one cycle by improvement of the control algorithm (see Supplementary Note 7 and Supplementary Fig. 7). The distinct phase relation of io being ahead of uo shows a negative-inductance behavior. Since the phase difference is not exactly 90 degrees, the terminal impedance of the circuit also supports an equivalent negative resistance. Moreover, the power analyzer displays the values of RD(ω) (UDF5) and ωLD(ω) (UDF3), which exhibit tailored frequency dependence.

It can also be seen in Fig. 5b that the digital non-Foster circuit can handle large voltages and currents (see Supplementary Note 6 and Supplementary Fig. 6). These performance metrics broaden the application scenario of digital non-Foster electronics. Here we apply this technique to transmit an image via airborne acoustic channels, to realize broadband and long-haul communication based on high-power acoustic radiation (Fig. 5c). Due to rapid tracking of different tone frequencies with optimal control characteristics, audio signals encoded via the frequency shift keying (FSK) modulation52 can be loaded continuously and stably onto the electroacoustic transmitter matched through the designed digital non-Foster circuit. To distinguish the bandwidths of the electroacoustic transmitter under different impedance matching approaches, here yellow, red, blue, black, and white are represented by 200 Hz tone, 300 Hz tone, 600 Hz tone, 1000 Hz tone, and 1200 Hz tone, respectively (see Supplementary Note 8 and Supplementary Figs. 8-9). Since the electroacoustic transmitter connected with a synthetic negative resistance and inductance with FD was significantly enhanced by bandwidth expansion, each color of the self-made Hunan University photo (four Chinese characters), represented by different frequency tones, can be received. By comparison, since the system bandwidths under synthetic negative resistance and inductance without FD and passive matching are relatively narrow, the pixels of the Hunan University photo at higher tone frequencies are lost (See Supplementary Movie 1).

Discussion

In conclusion, we have demonstrated digital non-Foster-inspired electronics by leveraging digital control techniques and switch-mode electronics. Distinct from op-amp-based analog non-Foster circuits, the proposed circuit enhances the implementation of non-Foster impedance matching. The transition from analog to digital implementation provides an opportunity to synthesize equivalent negative R and C/L with desired FD, ensuring stability and good transient performance. Furthermore, the implementation of programmable control evades tedious manual operation, which ensures active circuits with the real-time tunability. From the hardware design standpoint, the utilization of switch-mode electronics results in a leap forward in terms of power handling. Long-range image transmission experiments have validated the superiority of the proposed digital non-Foster electronics in terms of real-time tunability and high-power handling. Breaking through the limitations in operating frequency range of 4 kHz, the proposed digital non-Foster-inspired electronics may offer new opportunities for enhancing the bandwidth, power and agility of sub-wavelength resonance-based systems, also beyond acoustics, and promote practical implementation of broadband metamaterials.

Methods

Stability analysis

To analyze the stability of loading the electroacoustic transducer with the digital non-Foster-inspired electronics, the general circuit structure shown in Fig. 3a is simplified as its transfer function block diagram in Supplementary Fig. 2a. According to Mason’s gain formula, the block function diagram can be simplified as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2b. The corresponding open-loop transfer function block diagram is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 2c. By evaluating the pole locations of the transfer function as the four key control parameters, including Kp, Kr, Kf, and wc, varied, we can observe the parameter ranges that are capable to assure the system stable operation. The root locus can be plotted as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2d, e. The open-loop gain/phase margins can be plotted as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2f. Consequently, the parameter design of PR controller for stability is easy to achieve as elaborated in Supplementary Note 2.

Software design for the digital non-Foster-inspired electronics

The software design primarily consists of the main program and interrupt service routines (ISRs). A DSP (TMS320F28335, Texas Instruments) is used to execute programs here. In the main program (Supplementary Fig. 3a), initialization of peripherals and PR controller, as well as the relevant interrupt configuration, is complete. Afterwards, the DSP remains in a waiting state until interrupts occur. The purpose of the timer interrupt is to generate the PWM output pulses, and the period of the pulse is equal to the timer period. Whenever the counter overflows, an interrupt will be generated by the timer. Then, an interrupt request will be sent to the CPU where the ISR is handled, once it is idle. Meanwhile, the program pointer will be automatically located to the starting address of the ISR function. The primary work of the timer ISR, shown in Supplementary Fig. 3b. The detailed steps are elaborated in Supplementary Note 3.

The experimental design of image transmission over airborne acoustic channels

The image transmission experiments over airborne acoustic channels are carried out with the frequency shift keying (FSK) technique52. The receiver node is installed to an open playground at a distance of approximately 60 meters from the transmission node, which minimized the impact of acoustic reflection and environmental noises on reception, as illustrated in Fig. 4c of the main text. The operation of the complete experiment is introduced in Supplementary Note 8.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code to implement the DSP control of our digital non-Foster-inspired circuit as well as all the Matlab codes for the experiment of image transmission over airborne acoustic channels is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11120641.

References

Kemp, M. A. et al. A high Q piezoelectric resonator as a portable VLF transmitter. Nat. Commun. 10, 1715 (2019).

Ma, G. & Sheng, P. Acoustic metamaterials: From local resonances to broad horizons. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501595 (2016).

Cummer, S. A., Christensen, J. & Alù, A. Controlling sound with acoustic metamaterials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 1–13 (2016).

Rasmussen, C. & Alù, A. Non-Foster acoustic radiation from an active piezoelectric transducer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 118, e2024984118 (2021).

Chu, L. J. Physical limitations of omni-directional antennas. J. Appl. Phys. 19, 1163–1175 (1948).

Qu, S. & Sheng, P. Microwave and acoustic absorption metamaterials. Phys. Rev. Appl. 17, 047001 (2022).

Sievenpiper, D. F. et al. Experimental validation of performance limits and design guidelines for small antennas. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 60, 8–19 (2011).

Li, H., Mekawy, A. & Alù, A. Beyond Chu’s limit with Floquet impedance matching. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 164102 (2019).

Shlivinski, A. & Hadad, Y. Beyond the Bode-Fano bound: Wideband impedance matching for short pulses using temporal switching of transmission-line parameters. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 204301 (2018).

Shi, T. et al. Improved signal-to-noise ratio, bandwidth-enhanced electrically small antenna augmented with internal non-Foster elements. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 67, 2763–2768 (2019).

Chen, H. C., Yang, H. Y., Kao, C. C. & Ma, T. G. Slot antenna with non-Foster and negative conductance matching in consecutive bands. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 18, 1203–1207 (2019).

Dong, Z. et al. Sensitive readout of implantable microsensors using a wireless system locked to an exceptional point. Nat. Electron. 2, 335–342 (2019).

Chen, P. Y. et al. Generalized parity-time symmetry condition for enhanced sensor telemetry. Nat. Electron. 1, 297–304 (2018).

Fleury, R., Sounas, D. & Alù, A. An invisible acoustic sensor based on parity-time symmetry. Nat. Commun. 6, 5905 (2015).

Zhu, X., Ramezani, H., Shi, C., Zhu, J. & Zhang, X. PT-symmetric acoustics. Phys. Rev. X 4, 031042 (2014).

Cao, W. et al. Fully integrated parity-time-symmetric electronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 262–268 (2022).

Assawaworrarit, S. & Fan, S. Robust and efficient wireless power transfer using a switch-mode implementation of a nonlinear parity-time symmetric circuit. Nat. Electron. 3, 273–279 (2020).

Assawaworrarit, S., Yu, X. & Fan, S. Robust wireless power transfer using a nonlinear parity-time-symmetric circuit. Nature 546, 387–390 (2017).

Shao, L. et al. Non-reciprocal transmission of microwave acoustic waves in nonlinear parity-time symmetric resonators. Nat. Electron. 3, 267–272 (2020).

Popa, B. I. & Cummer, S. A. Non-reciprocal and highly nonlinear active acoustic metamaterials. Nat. Commun. 5, 3398 (2014).

Jacob, M. M. & Sievenpiper, D. F. Non-Foster matched antennas for high-power applications. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 65, 4461–4469 (2017).

Hrabar, S., Krois, I. & Zanic, D. Improving stability of negative capacitors for use in active metamaterials and antennas. In 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Antennas and Propagation and USNC-URSI Radio Science Meeting (AP-S/URSI), 1901-1902 (2018).

Ugarte-Munoz, E., Hrabar, S., Segovia-Vargas, D. & Kiricenko, A. Stability of non-Foster reactive elements for use in active metamaterials and antennas. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 60, 3490–3494 (2012).

Della Giovampaola, C. & Engheta, N. Digital metamaterials. Nat. Mater. 13, 1115–1121 (2014).

Rivet, E. et al. Constant-pressure sound waves in non-Hermitian disordered media. Nat. Phys. 14, 942–947 (2018).

Guo, X., Lissek, H. & Fleury, R. Improving sound absorption through nonlinear active electroacoustic resonators. Phys. Rev. Appl. 13, 014018 (2020).

Hu, H. et al. Gate-tunable negative refraction of mid-infrared polaritons. Science. 379, 558–561 (2023).

Popa, B. I., Zhai, Y. & Kwon, H. S. Broadband sound barriers with bianisotropic metasurfaces. Nat. Commun. 9, 5299 (2018).

Fang, X. et al. Programmable gear-based mechanical metamaterials. Nat. Mater. 21, 869–876 (2022).

Chen, T., Pauly, M. & Reis, P. M. A reprogrammable mechanical metamaterial with stable memory. Nature 589, 386–390 (2021).

Cho, C., Wen, X., Park, N. & Li, J. Digitally virtualized atoms for acoustic metamaterials. Nat. Commun. 11, 251 (2020).

Weldon, T. P., Covington, J. M., Smith, K. L. & Adams, R. S. Performance of digital discrete-time implementations of non-Foster circuit elements. In 2015 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), 2169–2172 (2015).

Weldon, T. P., Covington, J. M., Smith, K. L. & Adams, R. S. Stability conditions for a digital discrete-time non-Foster circuit element. In 2015 IEEE Antennas and Propagation Society International Symposium (APSURSI), 71-72 (2015).

Kehoe, P. J., Steer, K. K. & Weldon, T. P. Thevenin forms of digital discrete-time non-Foster RC and RL circuits. In 2016 IEEE Antennas and Propagation Society International Symposium (APSURSI), 191–192 (2016).

Kehoe, P. J., Steer, K. K. & Weldon, T. P. Stability analysis and measurement of RC and RL digital non-Foster circuits with latency. In SoutheastCon 2017, 1-4 (2017).

Daniel, C. G. & Weldon, T. P. A stable digital impedance circuit design method for resistive source impedances. IEEE Open J. Circuits Syst. 3, 109–114 (2022).

Hrabar, S., Cavlek, I., Mikulic, D., Milic, S. & Sopp, E. Extension of Non-Foster-inspired Two-transmitter Matching to Arbitrary Antenna Impedance. 2021 International Symposium ELMAR, 49-52 (2021).

Kiricenko, A. & Hrabar, S. Non-Foster-inspired Two-transmitter System based on Coherent Current/voltage Sources. In 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Antennas and Propagation and USNC-URSI Radio Science Meeting (AP-S/URSI), 1308–1309 (Denver, CO, USA, 2022) https://doi.org/10.1109/AP-S/USNCURSI47032.2022.9886333.

White et al. Switched Mode Negative Inductor, US patent 9923548. 1–13 (2018).

Zhou, J., Zhang, B., Xiao, W., Qiu, D. & Chen, Y. Nonlinear parity-time-symmetric model for constant efficiency wireless power transfer: Application to a drone-in-flight wireless charging platform. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 66, 4097–4107 (2018).

Yang, X. et al. Observation of transient parity-time symmetry in electronic systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 065701 (2022).

Seifi, K. & Moallem, M. An adaptive PR controller for synchronizing grid-connected inverters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 66, 2034–2043 (2018).

Teodorescu, R., Blaabjerg, F., Liserre, M. & Loh, P. C. Proportional-resonant controllers and filters for grid-connected voltage-source converters. IEE Proc.-Electr. Power Appl. 153, 750–762 (2006).

KYOCERA AVX. Surface Mount Ceramic Capacitor Products. 1–135. https://catalogs.kyocera-avx.com/SurfaceMount.pdf.

Butler, J. L. & Sherman, C. H. Transducers and arrays for underwater sound. 517–553 (Springer, Cham, 2016).

Mojahed, A., Bergman, L. A. & Vakakis, A. F. Generalization of the concept of bandwidth. J. Sound Vib. 533, 117010 (2022).

Leach, W. M. Introduction to electroacoustics and audio amplifier design. 85–105 (Kendall Hunt, Dubuque, IA, 2010).

Wright, J. R. An empirical model for loudspeaker motor impedance. J. Audio Eng. Soc. 38, 749–754 (1990).

Holmes, D. G. & Lipo, T. A. Pulse width modulation for power converters: principles and practice (John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ, 2003).

Loncar, J., Hrabar, S. & Muha, D. Stability of simple lumped-distributed networks with negative capacitors. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 65, 390–395 (2016).

Yepes, A. G. et al. Effects of discretization methods on the performance of resonant controllers. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 25, 1692–1712 (2010).

Hahn, P. Theoretical diversity improvement in multiple frequency shift keying. IEEE Trans. Commun. 10, 177–184 (1962).

Acknowledgements

X.Y. would like to thank the support given by a National Natural Science Foundation of China grant (52077071) and a grant (2019RS1028) from Department of Science and Technology of Hunan Province, China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Y., X.Z., X.O. and A.A. conceived and developed the concept. X.Y., Z.Z. and M.X. designed and built the non-Foster-inspired circuit. X.Y. planned and directed the experiments. X.Y., Z.Z., M.X., X.Z., S.L. and Y.Z. performed the experiments. X.Y., Z.Z., and S.L. performed the simulation and theoretical analysis. X.Y., Z.Z. and M.X. wrote the initial draft of the paper. X.Y., Z.Z., Y.Z. and A.A. contributed to interpreting the results, editing, and revising the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Maria Guadalupe Ortiz-Lopez and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, X., Zhang, Z., Xu, M. et al. Digital non-Foster-inspired electronics for broadband impedance matching. Nat Commun 15, 4346 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-48861-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-48861-6

This article is cited by

-

Active control of electroacoustic resonators in the audible regime: control strategies and airborne applications

npj Acoustics (2025)

-

Anomalous quality factor evolution of induced transparency in a virtualized coupled-oscillator system

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2025)