Abstract

The family of coinage-metal-based cyclic trinuclear complexes exhibits abundant photophysical properties, promising for diverse applications. However, their utility in biochemistry is often hindered by large particle size and strong hydrophobicity. Meanwhile, the investigation into multi-photon excited luminescence within this family remained undocumented, limiting their potential in bio-imaging. Herein, we unveil the multi-photon excited luminescent properties of pyrazolate-based trinuclear gold(I) clusters, facilitated by excimeric gold(I)···gold(I) interactions, revealing a nonlinear optical phenomenon within this family. Furthermore, to address issues of poor biocompatibility, we employ electrospinning coupled with hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin as the matrix to fabricate a flexible, durable, transparent, and red emissive film with a photoluminescence quantum yield as high as 88.3%. This strategy not only produces the film with sufficient hydrophilicity and stability, but also achieves the downsizing of trinuclear gold(I) clusters from microscale to nanoscale. Following the instantaneous dissolution of the film in the media, the released trinuclear gold(I) nanoparticles have illuminated cells and bacteria through a real-time, non-toxic, multi-photon bio-imaging approach. This achievement offers a fresh approach for utilizing coinage-metal-based cyclic trinuclear complexes in biochemical fields.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coinage-metal-based cyclic trinuclear complexes (CTCs) represent a specific class of metallocycles with metal(I)···metal(I) interactions1. Characterized by Au(I)/Ag(I)/Cu(I) cations at the core and bridged by ditopic cyclo rings as anionic bridging ligands, CTCs benefit from the strategic design of the nine-membered ring and ligand substituents2, allowing for the attainment of diverse luminescent behaviors or charge-transporting properties3. Since the 1970s, many CTCs have been successfully synthesized and characterized4,5,6,7,8. To date, a wide range of applications for CTCs, such as lighting devices9,10,11, sensors12,13, and photocatalysis14,15,16 have been reported. As an important member of the CTCs family, gold cyclic trinuclear compounds (AuCTCs) possess stronger Au(I)···Au(I) bonding energies than Ag(I)···Ag(I) and Cu(I)···Cu(I) interactions17, leading to exceptional one-photon excited luminescence (1PEL) properties. For example, Li’s group presented a pyrazolate AuCTC as a single phase white-phosphorescent emitter by modulating monomeric and excimeric dual emissions18. Omary’s group reported a near-unity photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) of 97.13% achieved by the cupriphication of AuCTCs19. In addition, AuCTCs often serve as aggregation-induced emission (AIE) materials with a large Stokes shift, offering advantages by reducing fluorescence background interference in microscopy imaging. Combined with their non-toxic nature, strong bio-inertness, and excellent photostability derived from their gold-based composition, AuCTCs hold immense potential in bio-imaging applications.

However, challenges such as considerable particle size and strong hydrophobicity across the majority of the family lead to limited reports on their biochemical applications. Compared to conventional 1PEL, multi-photon excited luminescence (MPEL) represents a nonlinear optical phenomenon wherein a material absorbs multiple incident photons of lower energy simultaneously and subsequently emits light of higher energy20. Using materials with up-conversion MPEL characteristics for bio-imaging through a microscope presents distinct advantages including background scattering suppression, improved longitudinal (z-axis) resolution, and extended penetration depth21,22,23, opening alternative perspectives to achieve dynamic in vivo bio-imaging24,25,26,27,28. Nevertheless, to date, the manifestation of MPEL phenomena within AuCTCs or even CTCs remains undocumented.

Herein, we synthesized pyrazolate-based trinuclear gold(I) clusters (denoted as Au3), representing a member of AuCTCs. We elucidated that Au3 delivers intense three-photon excited luminescence under NIR irradiation through the eximeric Au(I)···Au(I) interactions, a distinctive luminescence mechanism distinguishes it from conventional organic dyes. Furthermore, to enhance the luminescent performance of Au3 and address the issue of poor biocompatibility, we employed a synergetic technique combining electrospinning with hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD) as a matrix. This approach successfully fabricated a flexible, large-area, durable, and transparent film (denoted as Au3-CD film), characterized by red phosphorescence with a 14.4% improvement of PLQY over Au3. Moreover, the fabrication strategy significantly improves the biocompatibility by reducing the size of Au3 and enhancing water solubility. An in-depth study was conducted to evaluate the triplet charge transfer states through the analysis of 1PEL, MPEL, excitation dynamics and theoretical simulations, aiming at understanding the underlying reasons for the enhancement of luminescence. As a proof of concept, Au3-CD film was applied for real time, non-toxic, up-conversion multi-photon bio-imaging of live murine macrophage cell line J774A.1 and Escherichia coli (E. coli). Through the instantaneous dissolution of the Au3-CD film in the media, the HPβCD-enveloped Au3 nanopartilces can be released and subsequently actively internalized by the cells, thereby showcasing a capability beyond that of Au3 alone. Drawing from the discovery of Au3’s MPEL properties, this study provides valuable insights into nanoscale fabrication and biocompatibility enhancement, thereby paving the way for the extensive application of CTCs in the biochemical field.

Results

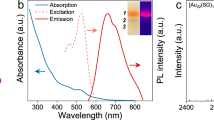

The linear and nonlinear optical properties of Au3

The one-step synthesis of Au3 clusters (structural formula shown in Fig. 1a) using the ligand bis-3,5-(ethoxycarbonyl)−1H-pyrazole is simple, rapid, and delivers a decent yield as reported by Lu et al. 11. The crystal structure of Au3 exhibits a one-dimensional chair-stacking pattern (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1), in which the intermolecular Au(I)···Au(I) distances are 3.273 Å or 3.492 Å29. Under UV light irradiation, Au3 crystalline powder exhibits a broad lower-energy (LE) emission band centered at 670 nm, which partially falls within the near-infrared I region (Supplementary Fig. 2). Coupled with its large Stokes shift, which may reduce biological fluorescence background, Au3 is highly suitable for bio-imaging applications, particularly in vascular or in vivo imaging. The time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) spectrum shows a single-exponential time constant of 15.58 μs for Au3 (Supplementary Fig. 3). It was found that a high concentration (10 g/L) of Au3 in a clear solution of dichloromethane did not yield detectable luminescence. Conversely, when Au3 is suspended in water, it exhibits a luminescence phenomenon consistent with that of a solid (Supplementary Fig. 4). This indicates that Au3 is an AIE material, and the LE band exists in the aggregated state, thereby excluding the possibility of luminescence arising from intramolecular charge transfer or intramolecular Au(I)···Au(I) interaction. The above clues suggest that the LE phosphorescence of Au3 originates from intermolecular Au(I)···Au(I) interaction in excimers. This aligns with the distinctive phosphorescence mechanism known as aurophilicity17,30,31, observed in the majority of AuCTCs1,3. The effect of the spin–orbit coupling arising from the heavy gold atoms results in a high rate constant and efficiency for intersystem crossing (ISC)32. Additionally, the protection provided by surrounding ligands and the support from the rigid and planar structure keep its luminescent center away from oxygen. This, in turn, maintains the possibility of phosphorescence, with a PLQY of 73.9% under room temperature (Supplementary Fig. 5).

a Chemical structure of Au3. b Demonstration of the stacking structure of Au3 dimer. Substituents on the pyrazole ring have been omitted for clarity. c Temperature-dependent PL spectra of Au3 crystalline powder (λex = 300 nm). d CLSM images of Au3 microcrystals under bright-filed mode or various excitation wavelengths. The luminescent images captured at 550–750 nm emission were pseudo-colored (red). e Logarithmic relationship between MPEL intensity and input laser power. f Excitation wavelength-dependent MPEL spectra of Au3 crystalline powder.

A comprehensive exploration of the 1PEL photophysical properties of Au3 was undertaken through temperature-dependent photoluminescence (PL) and time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) characterization. As shown in Fig. 1c, the LE band of Au3 peaked at 275 K and decreased gradually as temperature increased from 275 K to 450 K, accompanied by a red-shift and boarding. This is likely attributed to the variation in the intermolecular Au(I)···Au(I) distances upon heating. Interestingly, when the temperature fell below 150 K, the dominance of the LE band was replaced by a broad and unstructured higher-energy (HE) band centered around 470 nm. This HE band exhibited a nearly identical excitation profile (Supplementary Fig. 6) and showed a reciprocal relationship in the range of 78 K to 150 K with the LE band, implying a common origin between them. Considering the microsecond lifetimes of both the HE and LE emission peaks (Supplementary Fig. 7, and Supplementary Table 1), it is reasonable to infer that these two emission bands originate from alternative excimeric states with different Au(I)···Au(I) distances33,34.

Excitingly, confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) images (Fig. 1d) demonstrate that Au3 exhibits strong MPEL with the irradiation of near-infrared (NIR) femtosecond laser (the wavelength ranges from 800 to 1000 nm). Note that the absorption band (Supplementary Fig. 8) of Au3 still lies within the UV region (<400 nm). NIR laser irradiation can still effectively induce luminescence, even though it exceeds its absorption wavelength by more than twice. Hence, we attempted to gain more information about the multi-photon absorption nature of Au3 through power-dependent up-conversion spectra (Supplementary Fig. 9). A linear log(I)-log(P) relationship can be established with a slope of 3.2 under an incident light of 840 nm, where I is the MPEL intensity and P is the laser power (Fig. 1e). Also, the MPEL spectra of Au3 under different NIR excitation wavelengths (Fig. 1f) or laser power exhibit a consistent emission band with its 1PEL spectra under UV excitation. This indicates that the relaxation process following both one-photon absorption and multi-photon absorption is consistent. While the luminescence mechanism of conventional MPEL materials, i.e., organic dyes, relies on their intramolecular donor-π-acceptor structure20, it is reasonable to infer that the MPEL behavior of Au3 follows a similar pattern as its 1PEL. This is attributed to the excimeric Au(I)···Au(I) interactions, rendering it an uncommon case among MPEL materials. More specifically, when subjected to incident light at 840 nm, the dimer of Au3 absorbs three photons (3PA) simultaneously to achieve up-conversion emission, known as the three-photon excited luminescence. Based on the MPEL spectra (Fig. 1f), the multi-photon action cross-sections (MPACS) of Au3 were studied using rhodamine B (RhB) as a reference material with known two-photon adsorption cross-sections35,36. The results indicate that Au3 has an MPACS ranging from 0.07-5.7 GM under the excitation of 820–890 nm (Supplementary Table 2), which is comparable to that of RhB (0.27–3.0 GM).

To the best of our knowledge, the evidence of MPEL properties in AuCTCs and the broader CTCs family had not been previously documented. Herein, we confirm that the metal-organic compound Au3 indeed possesses these properties, presenting a promising finding. Given that Au3 is an AIE material with an outstanding PLQY11 and large MPACS, it emerges as an exceptionally compelling candidate for bio-imaging. However, from the CLSM images (Supplementary Fig. 10), it is evident that the sizes of Au3 microcrystals are comparable to those of J774A.1 cells. In the case of E. coli, the sizes of Au3 microcrystals are even ten times larger. The images also demonstrate that E. coli neither aggregates on nor engages in feeding around Au3 microcrystals, suggesting that Au3 exhibits no attraction to them. The considerable size difference poses enormous challenges in the effective utilization of Au3 microcrystals by cells and bacteria. As a direct evidence, CLSM images reveal that the use of Au3 for staining both types of live cells did not induce luminescence under 850 nm excitation. Thus, large particle size and low water solubility of Au3 severely limit its application in the field of chemical biology and there is an urgent need to enhance the biocompatibility of Au3.

Fabrication of Au3-CD film and morphological characterization

To solve the issues of large particle size and low water solubility, electrospinning was utilized as a straightforward, rapid and convenient technique37 to achieve the incorporation and modification of Au3. HPβCD was chosen as the matrix because it features many active hydroxyl groups that allow it to have various kinds of interaction with the guest component, as well as excellent water solubility, non-toxicity, and robust chemical stability. The obtained Au3 crystalline powder can be blended with 45% HPβCD (w/w, according to H2O) in ambient conditions for electrospinning (Fig. 2a, see details in the Methods section). Upon electrospinning, an Au3-CD film measuring 23 cm × 15 cm (Fig. 2b) can be formed, exhibiting uniform bright red emission over the entire film under UV light irradiation (Fig. 2c). Intriguingly, exposure of Au3-CD film to water vapor for 5 min resulted in its transparency. The transparent Au3-CD film exhibited exceptionally high transparency, with a transmittance of 88.1% in the visible region (400–800 nm) (Supplementary Fig. 11). Notably, the fabrication of Au3-CD films via electrospinning is both environment-friendly and cost-effective, while also achieving high material efficiency. A minimal amount of Au3 (5 mg) and organic solvent (0.5 mL dimethyl sulfoxide) is sufficient to produce intense and uniform red luminescence across the entire film. Thus, the overall production cost of Au3-CD film is as low as 0.0024 $/cm2 (Supplementary Table 3). It is in line with sustainable manufacturing principles, providing a practical solution for the production of advanced materials that complies with eco-conscious and economical industrial standard. As a demonstration, a handcrafted red luminescent jellyfish was created from Au3-CD film, which serves as an inspiration for applications in transparent and flexible displays (Fig. 2d, e and Supplementary Fig. 12).

a Schematic illustration of the fabrication process of Au3-CD films. b Demonstration of the as-prepared white Au3-CD film under indoor light. c, d Demonstration of the flexible and red emissive Au3-CD film under 254 nm UV light. e Demonstration of handcrafted jellyfish made of transparent an Au3-CD film under 254 nm UV light. f, g Photos of drop shape analysis for (f) Au3 crystalline powder and (g) Au3-CD film. h, i SEM images of Au3-CD film (h) before water vapor treatment and (i) after water vapor treatment. j STEM images of fibers in Au3-CD film. k Corresponding EDS Mapping of gold in Au3-CD film. l STEM images of dissolved Au3-CD film. Insets display the magnified view of an HPβCD enveloped Au3 NPs.

Sequentially, the hydrophilicity and morphology of the film were characterized. From the drop shape analysis (Fig. 2f), it can be seen that the original Au3 crystalline powder was highly hydrophobic, with a contact angle of 134°. After being prepared into a film, Au3-CD film exhibited outstanding hydrophilicity, to the extent that the contact angle changed to 26° (Fig. 2g). The dramatic improvement in hydrophilicity observed in Au3-CD film is likely attributed to the excellent hydrophilic properties of HPβCD. Consequently, Au3-CD film could be directly dissolved into water while maintaining the luminescent properties of Au3. The morphological changes of the film during the electrospinning and transparency process were recorded by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images. The original white Au3-CD film is composed of numerous fibers with diameters ranging from 0.2 to 0.5 μm and pores with diameters ranging from 1 to 10 μm (Fig. 2h and Supplementary Fig. 13). Under water vapor treatment, the pores were gradually filled, resulting in the formation of a dense and uniform thin film (Fig. 2i and Supplementary Fig. 14). This fact may be ascribed to the promotion of hydrogen bonding interactions between HPβCD oligomers when water molecules filled the surface or pores of the film38. Significantly, the uniform distribution of small-sized Au3 nanoparticles (NPs) on the surface or interior of the electrospun fibers were achieved through electrospinning. Images obtained from scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) revealed numerous bright dots on the interwoven fibers (Fig. 2j), confirmed by energy dispersive X-ray spectra (EDS) mapping to be primarily composed of gold (Fig. 2k). STEM and TEM images revealed a fascinating phenomenon that the dissolved Au3-CD film released Au3 NPs enveloped within HPβCD vesicles, exhibiting diameters ranging from approximately 50 to 500 nm. (Fig. 2l and Supplementary Fig. 15). The Au3 NPs exhibited a predominantly spherical morphology, with 88.7% having a diameter smaller than 20 nm and an average diameter of 11.2 nm (Supplementary Fig. 16). This demonstrates that, through electrospinning, the size of Au3 microcrystals was significantly reduced to about 1/700 of their original size (ca. 8 μm × 0.6 μm, Supplementary Fig. 17). The presence of intriguing HPβCD vesicles in the solution of Au3-CD film further provides steric hindrance that consequently facilitates the dispersion of Au3 NPs. The success in reducing the size of Au3 to nanoscale and enhancing its hydrophilicity has paved the way for the utilization of Au3 in various bio-imaging applications.

Chemical interactions

To gain a deeper understanding of the interaction mechanism between HPβCD and Au3, we employed a variety of characterization techniques for analysis. First of all, a suitable polymer matrix that could enhance photoluminescence (PL) performances and fulfill the requirements of biochemical applications is crucial. We evaluated the PL intensity of Au3 in HPβCD and four commonly used polymers, namely, polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP), polyurethane (PU), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and polystyrene (PS). It can be observed that the combination of Au3 with HPβCD resulted in a 49% enhancement of PL intensity (Supplementary Fig. 18). In contrast, other polymers like PVP, PU, and PS resulted in varying degrees of quenching, while PVA induced a slight enhancement in PL intensity. According to this, we investigated the interaction between Au3 and HPβCD with nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra. We found that all the 1H chemical shifts of HPβCD, showed negligible change after mixing Au3 with HPβCD (Supplementary Table 4 and Fig. 19). Therefore, Au3 was not encapsulated by the inner cavity of HPβCD. On the other hand, 1H NMR spectra observed a 0.019 ppm downfield variation in the chemical shift of Au3’s H1 protons which are around the C=O group (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 5). Also, the 13C NMR spectra delivered a downfield shift of the carbonyl carbons (C3) in Au3 upon the addition of HPβCD (Supplementary Fig. 20). These observations suggest a change in the chemical environment around the C=O groups of Au339,40. Further clues were found with Fourier transform infrared spectra (FTIR) (Fig. 3b). For Au3, the characteristic peak around 1741 cm−1 could be assigned to the vibration of carbonyl (C=O) group, which was shifted to 1729 cm−1 in Au3-CD film. After processing the FTIR spectra using second-order derivatives, it is clear that all the wavenumbers of C=O vibration peaks associated with Au3 decreased in the Au3-CD film. (Fig. 3c). More importantly, the broad band in the range of 3100 ~ 3600 cm−1, which was attributed to the stretching vibration of hydroxyl (O–H) groups, showed a significant shift from 3403 cm−1 in HPβCD to 3363 cm−1 in Au3-CD film. This shift was accompanied by broadening and a decrease in intensity. In combination with the above observation, it can be inferred that hydrogen bonds may formed between the C=O groups of Au3 and the -OH groups of HPβCD. The Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns of Au3-CD film still retained the characteristic diffraction peaks of Au3 crystalline powder (Supplementary Fig. 21), confirming that the composition and crystal structure of Au3 were maintained in Au3-CD film. As the gold atoms are the core for Au3’s luminescence, we utilized X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) to investigate the changes in binding energy of gold in both Au3 and Au3-CD film. Compared to Au3, the binding energy of Au 4f2/5 characteristic peak in Au3-CD film increased by 0.7 eV (Fig. 3d). The rise in binding energy suggests a decrease in the electron density of the trinuclear gold core in Au3 following its complexation with HPβCD. The result of XPS also revealed that the change in the binding energy was accompanied with the broadening of the peak, which further confirmed the size decrease of Au341. This is consistent with the observations by TEM.

a 600 MHz 1H NMR spectra of Au3, HPβCD and Au3-CD mixed solution (Au3:HPβCD = 1:9, molar ratio). Inset: enlargement of the 1H chemical shift for H1. b FTIR spectra of Au3, Au3-CD film and HPβCD. c FTIR spectra processed with second-order derivatives (top) and enlarged view of C=O vibration regions (bottom) d XPS spectra of Au3 and Au3-CD film. e ESP distribution maps of Au3 (left) and Au3-CD complex (right).

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations42,43,44,45,46,47 of the frontier molecular orbitals were conducted for Au3 molecule and Au3-CD complex in water, utilizing the crystal structure obtained from Au3. In the optimized geometry of Au3-CD complex at ground state, the hydroxyl group on the outer surface of HPβCD was exposed to the carboxyl group of adjacent Au3 (Supplementary Fig. 22). The distance between the hydroxyl hydrogen atom of the hydroxyl group and the carboxyl oxygen atom of the carboxyl group measured approximately 1.8 Å, affirming the establishment of hydrogen bonds. The visualized electrostatic potential (ESP) maps48,49,50,51 (Fig. 3e) revealed the high electron density (shown as the blue region) in the trinuclear gold region of Au3 molecule. Upon the complexation of Au3 with HPβCD, a noticeable reduction in electron density around the trinuclear gold region occurred, which is in line with the XPS characterization. Both computational results and experimental characterization infer that the abundant hydroxyl groups of HPβCD may form a continuous network of intermolecular hydrogen bonds in Au3-CD film. This network can serve as a conduit for effective intermolecular charge transfer and exciton delocalization for Au352. The established hydrogen bond network plays a crucial role in facilitating these processes, enhancing the pull-push effects on electrons.

1PEL properties of Au3-CD film

The 1PEL spectrum of Au3-CD film closely resembles that of Au3, with both materials showing a broad emission band centered at 670 nm (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 23). TRPL spectra show an identical single-exponential time constant that can be fitted for both samples. The lifetime of Au3-CD film (15.19 μs) is slightly shortened compared to that of Au3 (15.58 μs) at room temperature (295 K) (Supplementary Fig. 24). Since the Au3 NPs in Au3-CD film preserves the AIE luminescent properties of Au3, it can be inferred that each Au3 NP contains multiple Au3 molecules29 in an aggregated state. Hence, the transformation by electrospinning effectively increases the number of luminescent units. Furthermore, Au3-CD film demonstrates outstanding luminescent efficiency, thermal stability, and long-term stability. Its PLQY reached 88.3%, which represented a 14.4% improvement over that of Au3 (Supplementary Fig. 25). Continuously monitoring of the PLQY performances of Au3-CD film has proved that its luminescent efficiency remained stable over 210 days, without any noticeable deterioration (Fig. 4b). Compared to Au3, the radiative decay rate (knr) increased by 7%, while the non-radiative decay rate (knr) decreased by 54% (Supplementary Table 6). These results imply a significant suppression of the non-radiative relaxation pathways in Au3-CD film. Further investigation on the 1PEL properties of Au3 with the complexation of HPβCD in water showed that the presence of concentrated HPβCD resulted in enhanced luminescence stability and intensity for Au3. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 26a, the PL intensity increased proportionally to the concentration of HPβCD. At the same time, normalized photoluminescence excitation (PLE) spectra demonstrate that increasing the concentration of HPβCD can effectively enhance the excitation efficiency in the region of 280-370 nm (Supplementary Fig. 26b). Due to Au3’s large crystal size and strong hydrophobicity, suspended Au3 in water tends to aggregate and precipitate rapidly, leading to poor luminescence stability. Experimental results showed that the PL intensity of the Au3 suspension decreased by 48% after 90 minutes (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 27a). In contrast, the PL intensity of Au3-CD film in water showed minimal decline over the same period (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 27b). As direct evidence that reflects the stabilizing effect of HPβCD on Au3 in water, zeta potential measurements revealed that the surface charge of Au3 in water changed from −21.2 ± 1.7 mV to −29.6 ± 3.0 mV (data are presented as mean values ± S.D.), following the introduction of HPβCD. The improved stability in PL intensity is due to the prevention of Au3 precipitation in the aqueous solution, facilitated by the increased viscosity from the high concentration of HPβCD.

a PL and PLE spectra of Au3-CD film. b Monitoring of the PLQY performances of Au3-CD film over time. Data are presented as mean values and standard deviations indicated by error bars, with n = 3. c Time-dependent PL intensity plotting of Au3 (10 mg/L) versus Au3-CD film (120 mg/L) in water. d Temperature-dependent steady-state PL mapping of Au3-CD film (λex = 300 nm). e Arrhenius plots of the integrated area of the PL emission band (centered at 670 nm) as a function of the reciprocal temperature (1/T) for Au3-CD film. f CIE coordinates for varied emission scans of Au3-CD film (78-450 K, λex = 300 nm).

In comparison with Au3, temperature-dependent PL and TRPL spectra of Au3-CD film exhibited consistent trends (Fig. 4d). Both exhibit a phenomenon where, below 150 K, the HE band (centered around 470 nm) predominates, while above 150 K, the LE band (centered around 670 nm) takes dominance. The HE band and LE band of Au3-CD film exhibit shortened lifetimes with increasing temperature (Supplementary Fig. 28). At each temperature point, the fitted lifetimes of Au3-CD film were slightly shorter than those of Au3 (Supplementary Table 7). The temperature-dependent results across various conditions provide additional evidence that the luminescence mechanism originates from the same source as Au3. The correlation between the integrated area of LE band and temperature can be graphically represented to calculate the exciton binding energy (Eb)53, quantifying the forces that binds an electron-hole pair54. The results showed that Au3-CD film had a larger Eb value (476.5 meV) than Au3 (315.6 meV) (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Fig. 29). This suggests the effective inhibition of exciton dissociation, which corresponds to a facilitated radiative recombination rate and improved PLQY55. In addition, Au3-CD film exhibits luminescence even at elevated temperatures (450 K), indicating excellent thermal stability. This was confirmed by PXRD analysis that both Au3 and Au3-CD film retained their characteristic peaks following the 450 K experiment (Supplementary Fig. 30). This retention signifies their capacity to maintain their crystalline phases under high temperature conditions. The temperature-induced ratiometric change in multiple emission bands leads to a gradual shift in the CIE color coordinates. This characteristic makes Au3-CD film a promising candidate for a flexible temperature sensor with a broad sensing range (78–450 K) (Fig. 4f). Thus, comprehensive characterization results indicate that Au3-CD film produced by electrospinning exhibits prominent advantages of luminescent performance, large-area, flexibility, hydrophilicity, long-term stability and thermotolerance.

Excitation dynamics analysis and theoretical simulations

To confirm the hypothesized impact of Au3-CD complex on the excitation dynamics, and to further elucidate the potential factors for improved luminescence efficiency, femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy (fs-TA) was employed in this study. With a pumping wavelength of 300 nm, the fs-TA matrix mapping of Au3 could be plotted out (Fig. 5a). It revealed three absorption bands, namely Band-A (440–500 nm), Band-B (510–560 nm), and Band-C (750–770 nm). The negative band, Band-B, appeared with a central wavelength of 524 nm. It corresponded to a minor absorption in the ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) absorption spectrum of Au3 (Supplementary Fig. 8), so it could be attributed to ground state bleaching (GSB)56. The positive Band-A exhibited rapid formation with a 200 fs rising time following the excitation (Supplementary Fig. 31a, c). It displayed a very short decay of 0.63 ps accompanied by weak intensity (Supplementary Fig. 32). In accordance with previous reports, intersystem crossing (ISC) or excited state absorption (ESA) processes linked to the triplet state are expected to unfold on a picosecond or longer timescale57,58. Hence, attributing Band-A to the ESA of the singlet state (S1→Sn) is justifiable, rather than associating it with the long-lived triplet ESA. As Band-A returned to the baseline, the positive Band-C arose gradually within the first 1 ns and then did not return to the baseline within the upper limit of delay time in fs-TA (Supplementary Figs. 33a and 34). The long duration (>7 ns) and significant intensity of Band-C strongly suggest its association with ESA of the triplet state (T1→Tn), which also indicates the occurrence of ISC. After the complexation of Au3 with HPβCD, the above adsorption bands were also observed (Fig. 5b), with the most notable change being the weakening of the positive Band-A and Band-C, representing ESA (Supplementary Fig. 31b, d and Fig. 33b). Specifically, the complexation with HPβCD, led to a 24% decrease in the rising time of Band-C (Fig. 5c), signifying an accelerated ISC rate59.

a, b Fs-TA data maps of (a) Au3 and (b) Au3-CD complexes. c Kinetic traces of Band-C and the corresponding fits of Au3 and Au3-CD complexes (λpump = 300 nm). d, e Ns-TA data maps of (d) Au3 and (e) Au3-CD complexes (λpump = 266 nm). f Diagram of energy levels for Au3 and Au3-CD complexes based on simulated vertical transition energy and time-resolved experimental results.

Nevertheless, the nanosecond delay range of fs-TA is insufficient for fully analyzing Au3’s luminescence dynamics, because Au3 exhibits long-lived phosphorescence associated with the triplet state. Therefore, nanosecond transient absorption (ns-TA) spectroscopy, as a powerful complementary technique for studying the triplet excited state dynamics in a larger time scale (e.g., ns-μs), has been utilized. For Au3, the ns-TA matrix mapping showed a distinct, positive and broad absorption band (Band-D) ranging from 700 nm to 900 nm (Fig. 5d). This band became noticeable in 52 ns post-pumping (Supplementary Fig. 35a). The kinetic spectra of Band-D exhibited a relative long lifetime, with a fitted lifetime of 5.88 μs at 760 nm (Supplementary Fig. 36). The lifetime of Band-D is comparable to the PL lifetime of Au3, once again providing offering strong evidence for ESA in the triplet state (T1→Tn)60. In addition, Band-D encompassed a broad spectral range, indicative of the densely packed energy levels associated with the higher triplet excited states61. The wavelength position of Band-D overlapped with the long-lived Band-C observed in fs-TA spectra, suggesting a correspondence between them. Upon the complexation with HPβCD, the positive Band-D weakened to nearly undetectable (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 35b). Based on the results from two transient absorption characterizations, it can be inferred that the complexation of HPβCD accelerates the ISC rate and suppresses the ESA of Au3.

To further verify the above observation, we performed time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) simulations to calculate the vertical transition energies. As illustrated in the energy level diagram (Fig. 5f), the computational results indicate that the singlet and triplet energy level distributions in Au3-CD complex have undergone varying degrees of changes compared to the Au3 molecule (Supplementary Tables 8 and 9). Firstly, the distribution of singlet excited state energy levels in Au3-CD complex has changed. Computational results indicated a reduction in the S1 energy level within Au3-CD complex, a finding consistent with the observed red shift in the absorption band in the UV-Vis spectra following the incorporation of Au3 with HPβCD (Supplementary Figs. 8 and 37). Furthermore, the enlarged energy gap between S1 and the higher singlet excited state Sn has similarly reduced the probability of singlet state ESA occurring, which aligns with the experimental phenomenon of Band-A obtained in fs-TA. Secondly, the energy levels at which ISC occurs differ in these two systems, taking place between S1 → T7 (Au3) and S1 → T3 (Au3-CD), respectively. Hence, Au3-CD complex undergoes less internal conversion and vibrational relaxation during the excitation process. Note that the internal conversion and vibrational relaxation events experienced during Sn → S1 or Tn → T1 transitions contribute to the loss of absorbed energy. Thirdly, the energy gap between T1 and the higher triple excited states Tn in Au3-CD complex has been enlarged, which could increase the difficulty for ESA to occur, thereby reducing the probability of ESA. This computational result is consistent with the experimental phenomenon of Band-D obtained in ns-TA. In summary, the experimental data and theoretical simulation collectively demonstrate that the modulation of energy levels of Au3 has been induced by the complexation with HPβCD. Such complexation effectively accelerates the ISC rate and suppresses the non-radiative transitions such as internal conversion and vibrational relaxation, leading to the enhanced PLQY. A potential explanation for the observed phenomenon is that the formation of hydrogen bonds between Au3 and HPβCD induces an electron push-pull effect. This, in turn, modulates the interaction between Au3 excimers and consequently alters the energy gap between the first excited state (S1/T1) and the higher excited state (Sn/Tn) energy levels. Noted the above simulation was based on the optimized model using a single HPβCD molecule and an Au3 molecule in water. In a real case, the physical form (whether aggregates or monomers), the environmental effects (solvents, temperature, atmosphere, etc.) and other complicated factors would greatly affect the photophysical properties of the system.

Light up cellular landscapes with Au3-CD film

Beyond its single-photon luminescent properties, Au3-CD film also exhibits excellent MPEL performance. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 38, where both Au3 microcrystals before fabrication and the fabricated Au3-CD film exhibit robust MPEL characteristics. More impressively, the MPACS of Au3-CD film has boosted to 71.3 GM (860 nm excitation) which is 65 times that of 2PACS observed in RhB (Supplementary Fig. 39 and Table 2). Prior research emphasizes the significance of enhancing the push-pull character to improve MPEL performances20,62. In this context, the hydrogen bonding interaction between Au3 and HPβCD may alter the electron density of the gold trinuclear core, thereby amplifying its push-pull effects. Due to the striking PLQY and MPACS of Au3-CD film, it is highly suitable for achieving visible red light emission within a wide excitation window (from UV to NIR regions), which makes it indeed an outstanding material for both 1PEL and MPEL luminescence. As a proof of concept, we used Au3-CD film to facilitate dynamic bio-imaging of live cells. E. coli and J774A.1 cell line were chosen as the representatives of microbial and mammalian cells, respectively. The staining process, as illustrated in Fig. 6a, is straightforward, rapid, and cost-effective (see details in the Methods section), making the Au3-CD film stand out among state-of-the-art MPEL materials (Supplementary Table 10). As an exceptional hydrophilic material, the Au3-CD film can be instantly dissolved in media and release abundant HPβCD-enveloped Au3 NPs. Hence, only a small quantity of Au3-CD film is required, for example, 1 cm2/0.5 mg of Au3-CD film in a 2 mL cell culture medium, which significantly reduces the costs associated with the use of precious metals. Moreover, using Au3-CD film for staining offers the distinct advantage of eliminating the need for rinsing steps, centrifugation or slide sealing procedures. This is attributed to the fact that Au3 functions as an AIE material, with luminescence occurring only when the material accumulates within the cells. Low concentrations of Au3 NPs in the culture medium do not induce significant MPEL. Significantly, the active uptake of Au3 NPs by cells has been visualized using low-voltage TEM. Figure 6b, 6c provide clear evidence, suggesting that J774A.1 cells actively undergo endocytosis of HPβCD-enveloped Au3 NPs through pseudopodia on their cell membranes. TEM images show the successful internalization of Au3 NPs within 2 h of feeding, and the accumulation of Au3 NPs within the cells became apparent with an increasing feeding time (Supplementary Fig. 40). These Au3 NPs maintained their original size (<40 nm) and were evenly distributed throughout the cytoplasm, showing no specificity towards particular cellular organelles. Furthermore, EDS analysis revealed the existence of gold element (mass fraction >0.1%) in cytoplasm, confirming the successful enrichment of Au3 NPs within the cells (Supplementary Fig. 41). Interestingly, the presence of Au3 NPs within some cell nuclei suggests the potential of small-sized Au3 NPs to penetrate nuclear pores (Supplementary Fig. 42). The above observation implies that Au3 NPs can internalize and accumulate in J774A.1 through active endocytosis, rather than non-specific passive diffusion. CLSM images showcase the pronounced MPEL of J774A.1 under 850 nm near-infrared laser irradiation (Fig. 6d), providing compelling evidence for the successful illumination of cells by Au3-CD film.

a Schematic illustration of multi-photon bio-imaging of J774A.1 by employing Au3-CD film. b TEM images for the cellular active uptake process of Au3 NPs by J774A.1 macrophage. The black arrows and yellow arrows indicate the HPβCD enveloped Au3 NPs and pseudopodia, respectively. c Enlarged TEM image for Au3 NPs in the cytoplasm of J774A.1. The red arrows indicate representative Au3 NPs. d CLSM images of J774A.1 incubated with Au3-CD film for 2.5 h. e CLSM images of E. coli incubated with Au3-CD film for 12 h. CLSM images were captured under bright-field (left), 850 nm laser irradiation (middle) and merged mode (right). The MPEL images captured at 850 nm excitation and 550–750 nm emission are pseudo-colored for better distinction.

Compared to mammalian cells, E. coli possesses a rigid multilayer cell wall, making the uptake of Au3 NPs as well as the realization of MPEL more challenging. This challenge arises from the very small pore size of E. coli’s cell wall (ca. 4 nm in diameter63). Only NPs with a sufficiently small size have the potential to penetrate this barrier, thereby facilitating subsequent intracellular uptake. Impressively, luminescent photos of live E. coli have been successfully captured under 850 nm excitation (Fig. 6e). This evidence indicates that the size of Au3 NPs from the dissolved Au3-CD film was sufficiently small to penetrate the cell wall of E. coli, achieving successful internalization. Given that HPβCD is a cyclic oligosaccharide capable of serving as a nutrient source for cells, this state can prompt cells to actively internalize the HPβCD enveloped Au3 NPs, resulting in the accumulation of Au3 NPs in the cellular interior. Thus, the internalization and accumulation of Au3, can effectively illuminate live cells. Because of the short life cycle and rapid metabolism of E. coli, it is highly conducive to study the metabolic fate of Au3 NPs within this microbe. We used Au3-CD film as a biological stain to observe differences in CLSM imaging after varying feeding durations. The results demonstrate that the bacteria maintained red luminescence even after 24 h of feeding (Supplementary Fig. 43). This suggests that after the internalization of Au3 NPs, the metabolic activities within E. coli did not completely degrade Au3. Even after multiple generations, Au3 NPs continued to accumulate within the cells, retaining their luminescent properties. The cytotoxicity of Au3 and Au3-CD film under various concentrations was assessed on both types of cells. For E. coli, the impact on its growth of E. coli was monitored using the characteristic absorbance at a wavelength of 600 nm (Supplementary Fig. 44). In the case of J774A.1, we used CCK8 validation to study absorbance changes at 450 nm (Supplementary Fig. 45). Both cell viability assays indicate that the presence of Au3 or Au3-CD has no negative impact on the growth of cells within the monitored periods. These findings affirm the low cytotoxicity of Au3-CD film, positioning it as a promising candidate for use as a biological luminescent labeling reagent. Based on the numerous advantages of Au3-CD film, such as outstanding MPEL properties, low cytotoxicity, and the potential for real-time, non-invasive and in vivo bio-imaging, it stands out as an exceptionally promising material for applications in biochemical field.

Discussion

In summary, our study elucidated the MPEL properties of the pyrazolate-based trinuclear gold(I) clusters. The observed luminescent mechanism under 840 nm NIR excitation is attributed to a three-photon excited up-conversion luminescence which arises from excimeric Au(I)···Au(I) interactions. Furthermore, a flexible, large-area (minimum unit size of 345 cm2), durable, transparent (transmittance of 88.1%) and red emissive (PLQY of 88.3%) film has been successfully fabricated via electrospinning. This Au3-CD film exhibits exceptional MPEL properties, marked by a 65-fold enhancement in MPACS compared to RhB. It also demonstrates excellent thermotolerance (>450 K) and long-term stability (>210 days). The enhancement of both 1PEL and MPEL performances is attributed to the modulation of excited state energy levels induced by the hydrogen bonding interactions between Au3 and HPβCD. Leveraging the technique of electrospinning, Au3 has been reduced to nanoscale, accompanied by a significant improvement in water solubility, which is a prerequisite and critical step towards biochemical applications. Finally, under the excitation of NIR laser, multi-photon bio-imaging of live cells (J774A.1 and E. coli) has been achieved with Au3 NPs released from the dissolution of Au3-CD film. Building upon the discovery of Au3’s MPEL properties, this study successfully translates and applies it to bio-imaging. This advancement not only enriches our understanding of the photophysical characteristics of AuCTCs but also provides valuable insights for nanoscale fabrication and biocompatibility enhancement strategies within the broader family of CTCs. Consequently, it has opened up diverse avenues for the application of the CTCs family in biochemical fields such as targeted in vivo bio-imaging and bio-sensing.

Methods

We confirmed that our research complies with all relevant ethical regulations, and the School of Chemical Engineering and Technology/Instrumental Analysis & Research Center/School of Chemistry, Sun Yat-sen University, approved the study protocol.

Materials

Hydroxypropyl β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD), polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP), triethylamine (Et3N), bis-3,5-(ethoxycarbonyl)−1H-pyrazole (HL), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) were purchased from Macklin Inc. Gold (tetrahydrothiophene) chloride (THT) was purchased from Shanghai Acmec Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Solvents such as ethanol, acetone and ether were purchased Guangzhou Chemical Reagent Factory.

Synthesis of cyclo-trimer Au(I) bis-3,5-(ethoxycarbonyl)−1H-pyrazolate (Au3)11

Firstly, a solution of HL (0.212 g, 1 mmol) in 30 mL of ethanol was prepared. Subsequently, a 30 mL acetone solution containing Au(THT)Cl (0.320 g, 1 mmol) was mixed with the ethanol solution. Following the addition of a few drops of anhydrous Et3N, white precipitates were formed immediately. The resulting suspension was stirred for an additional 30 minutes to ensure complete reaction. The white precipitate was collected by filtration and washed with 10 mL ethanol in a high yield (0.286 g, yield 46%). The as-prepared Au3 crystals showed bright red emission under the excitation of 254 nm UV light.

Fabrication of flexible Au3-CD film (15 cm × 23 cm in size)

Firstly, HPβCD was dissolved in 2 mL water at a mass ratio of 45%. PVP can be used as an additive at a mass ratio of 5% to the aforementioned solution to increase the viscosity. Subsequently, 8 mg of Au3 powder was dispersed in 0.5 mL of DMSO, achieving a uniform suspension through ultrasonication. The electrospinning ink is obtained by mixing the above HPβCD solution and Au3 suspension with stirring at room temperature. Moving on to the electrospinning process, the prepared electrospinning ink was loaded into a syringe equipped with a metallic needle. The syringe was positioned horizontally on a syringe pump in the electrospinning apparatus (E02, Foshan Qingzi Precision Measurement and Control Technology Co., Ltd) which was enclosed in a plexiglass box. The tip-to-collector distance was set as 10 cm. Subsequently, a high voltage (10 kV) was applied to the conductive needle using an electrospinning apparatus, while grounding the aluminum foil collector. Electrospinning was then carried out at a flow rate of 0.1 mL/h and a rotation speed of 600 rpm/min for 2 hours. The electrospinning process was conducted at a temperature range of 20–26 °C and a relative humidity between 40 and 70%. To prepare a transparent Au3-CD film, the resulting white Au3-CD film was placed over water vapor for uniform vapor deposition. The fibers in the film underwent rapid cross-linking, and after 5 min, a transparent Au3-CD film was obtained.

Characterization

An FLS1000 Fluorescence Spectrometer (Edinburgh Instruments) was used to test the steady-state photoluminescence (PL), time-resolved photoluminescence lifetime (TRPL) and photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY). The temperature-dependent measurement was conducted with DN Optical Cryostats (Oxford Instruments) as an apparatus on FLS1000. Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) analysis was performed on Empyrean (Malvern Panalytical). Detailed PXRD settings were as follows: a 2θ range of 5–50°, a step size of 0.026° and a step rate of 0.7 s. The UV-Vis absorption spectra were conducted on Lambda950 (Perkin Elmer) with an integrating sphere. The transmittance evaluation was conducted on Lambda950 by fixing the transparent Au3-CD film on a quartz plate. The morphological features of the Au3 and Au3-CD film were characterized using a Regulus 8230 (Hitachi) cold-field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM). The scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) images and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images for observing the microstructures of the film and the dissolved solution were captured with a Tecnai G2 F30 (FEI) transmission electron microscope at an accelerating voltage of 300 kV. Energy dispersive X-ray spectra and mapping (EDS) was obtained by the X Flash (Bruker) detector which was equipped on the Tecnai G2 F30 TEM. Photos of the contact angle were obtained on a DAS100 drop shape analysis system (Krüss). Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were obtained by Nicolet 6700-Continuμm (Thermo Fisher). For FTIR characterization, the Au3-CD film sample was prepared without PVP. The nuclear magnetic resonance (1H and 13C NMR) spectroscopy was performed on AVANCE III HD 600 (Bruker). All the samples were dissolved in a mixed solvent of deuterated dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO-d6) (Merck) and deuterated chloroform (CDCl3) (Merck) in a volume ratio of 3:7 in order to obtain a clear solution for NMR testing. The binding energy of gold on the surface of Au3 and Au3-CD film were characterized on an ESCALAB Xi+ (Thermo Fischer) X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy. Zeta potential measurement were performed on a zeta sizer EliteSizer (Malvern Instruments). For Zeta potential tests, fresh samples were prepared by suspending Au3 at a concentration of 100 mg/L in water. In the compared sample with the addition of HPβCD, the mass ratio between Au3 and HPβCD was 1:100. The confocal laser scanning microscopy images were taken using LSM 880 NLO confocal microscope (Zeiss), in which λex = 850 nm, λem = 550–750 nm, 140 fs/pulse, 80 MHz repetition. The images captured at 850 nm excitation were pseudo-colored (red) for better distinction.

Calculation of multi-photon action cross-section (MPACS)

The following formula was used to estimate the MPACS of Au3 and Au3-CD film using Rhoadamin B (RhB) as the reference,

where F(reference) is the measured MPEL peak intensity of the reference material, RhB. F(sample) is the measured MPEL peak intensity of Au3 or Au3-CD film. η is the PLQY, σ is the multi-photon absorption cross-section, ησ is the multi-photon action cross-section, ρ is the molar concentration, and I00 is the peak intensity of the input laser pulse. Typically, I = 25.1 mW (for both the sample and the reference); The data of σ(reference) of RhB varies depending on the excitation wavelength; η(reference) = 0.01 (RhB powder); η(sample) = 0.739 (Au3) or 0.883 (Au3-CD film); ρ(RhB) = 1.04 × 10−5 and ρ(sample) = 3.35 × 10−6 (Au3) or 3.24 × 10−7 (Au3-CD film).

Calculation of the exciton binding energy (E b)

The exciton binding energy (Eb) was calculated from the Arrhenius plot, according to the following Eq. (2):

where I0 is the integrated PL intensity at 0 K, KB is the Boltzmann constant and A is the Arrhenius coefficient.

Transient absorption spectroscopy characterization

Femtosecond transient absorption (fs-TA) spectroscopy measurement was performed on a pump/probe system by equipping a regeneratively amplified Ti: Sapphire laser source (Coherent Legend, 800 nm, 150 fs, 5 mJ·pulse−1, and 1 kHz repetition rate) and Helios (Ultrafast Systems LLC) spectrometers. A 75% portion of the 800 nm output pulse was frequency-doubled in a BaB2O4 (BBO) crystal, which could generate 300 nm pump light. Meanwhile, the remaining portion of the output was concentrated into a sapphire window to produce a white light continuum (400–780 nm) probe light. Time-resolved kinetic spectra were recorded with a delayed time ranging from 0 fs to 7.5 ns. For fs-TA measurements, fresh samples were prepared by suspending Au3 at a concentration of 1000 mg/L in ethanol. In the samples where HPβCD was added, the mass ratio between Au3 and the added HPβCD was 1:50.

Nanosecond transient absorption (ns-TA) spectroscopy measurement was performed on an LKS80 laser flash photolysis system (Applied Photophysics Ltd.). The fourth harmonic mode of the Nd:YAG laser (266 nm) was used as the pump light source. A xenon lamp (150 W) was used as the probe light source. The pump light from the pulsed laser was directed onto a sample cuvette at a right angle to a probe light. The variation of optical signal upon irradiation was recorded by a Philips PM3323B digital oscilloscope. The absorption spectra were recorded with a probing range of 600–900 nm at 5 nm step. Time-resolved kinetic spectra were recorded with a delayed time ranging from −4 μs to 36 μs. For ns-TA measurements, fresh samples were prepared by suspending Au3 at a concentration of 25 mg/L in ethanol. In the samples where HPβCD was added, the mass ratio between Au3 and the added HPβCD was 1:50.

Multi-photon bio-imaging tests

E. coli and J774A.1 were chosen as the typical cells for bio-imaging tests. J774A.1 cell line was bought from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). By maintenance of J774A.1, RPMI1640 media (Merck) was used and supplied with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Gibco) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. And cells were cultured in a T75 flask in an incubator with 5% CO2 supplement. After 24 h incubation, 1 × 1 cm2 Au3-CD film was introduced to each portion (2 mL) to label J774A.1 for 2 hours or more. The stained J774A.1 cells were then transferred to a confocal dish for assessing the staining performance using confocal laser scanning microscopy. E. coli (BNCC133264) was bought from BeNa Culture Collection. For the growth of E. coli, the Luria-Bertani medium consisting of 10 g/L tryptone, 10 g/L NaCl, and 5 g/L yeast extract was prepared. Following autoclaving (0.5 MPa, 121 °C, 15 min), the medium’s pH was adjusted to 7.4 ± 0.1. The bacteria were initially cultured for 24 hours and subsequently subcultured in closed serum bottles in triplicate, with an inoculum size of 10%. The bottles were agitated at 100 rpm in an incubator, maintaining the temperature at 37 ± 0.5 °C. After 24 h incubation, 2 × 2 cm2 Au3-CD film was added to each bottle (10 mL) to stain the E. coli. The E. coli (0.2 mL of the supernatant) were collected for evaluating the stain performance using a confocal laser scanning microscopy.

TEM imaging of cells

Cell ultrastructure imaging was conducted using a HT7800 TEM (Hitachi), operating at an accelerating voltage of 60–80 kV. The quantitative EDS measurement was performed by the 120 kV Tecnai G2 Spirit TEM (FEI) with X Flash (Bruker) detector. To ensure optimal specimen preparation, a systematic procedure was followed. Firstly, J774A.1 cells were treated with Au3-CD film (500 mg/L). After incubation periods of 2, 4 and 12 h, the culture medium of each specimen was discarded, and glutaraldehyde was rapidly added. Cells were gently scraped, collected into centrifuge tubes, and the glutaraldehyde was then replaced, allowing for a 2 hour fixation period. The specimens were rinsed three times with a 1% osmium tetroxide solution, followed by dehydration in a gradient series of ethanol (50%–70%–80%–90%–95%–100%). Following dehydration, the solvent was substituted with epoxy resin in a gradually increasing concentration. The specimens were infiltrated, embedded and polymerized at 37 °C for 12 h and 60 °C for 48 h. The hardened resin, along with the embedded specimens, was sectioned to a thickness of 60 nm using an ultramicrotome and mounted on copper grids. Subsequently, the sections were post-stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, which were finally ready for TEM imaging.

Cell viability assay

The impact on the growth of E. coli with Au3 or Au3-CD films in a concentration of 0.5–2.0 g/L was monitored at different feeding time using the characteristic absorption peak at a wavelength of 600 nm. The impact on the growth of J774A.1 with Au3 or Au3-CD film was assessed with the CCK8 assay. Before treatment, J774A.1 was digested into single cells by using trypsin-EDTA. Cells were counted and pipetted into 96-well plates at a density of 5,000 cells per well. After 24 h, cells were treated with the following concentrations: 0.5 g/L Au3, 0.5 g/L Au3-CD film, 1.0 g/L Au3-CD film and 2.0 g/L Au3-CD film. On the day of the CCK8 assay, 20 µL of CCK8 solution was added to each well and incubated for 2 h. Subsequently, the absorbance of 96-well plate was monitored with a microplate reader at a wavelength of 450 nm.

Computational details

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were carried out using Gaussian 16 programs43 throughout this manuscript. Geometric optimizations of the reactants, transition states, and products were performed using PBE0 functional42. The standard def2-SVP basis set44,45 for all atoms. An effective core potential associated with the def2-SVP basis set46 was used on Au atoms. Harmonic vibration frequency calculations were performed for all stationary points to confirm them as local minima. Approximate solvent (water) effects were taken into consideration based on the IEFPCM continuum solvation model47 in all calculations. Time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) calculations were performed on the optimized structures at the same theoretical level. The first 30 S0 → Sn and S0 → Tn vertical transitions were calculated for each model. The analyses of electrostatic potential (ESP) on molecular vdW surface were finished by Multiwfn49,50,51. The above isosurfaces were rendered by VMD program48 based on the outputs of Multiwfn. Abbreviations in this section: LUMO or L, lowest unoccupied molecular orbital; HOMO or H, highest occupied molecular orbital; f, oscillator strength; vdW, van der Waals.

Statistics and reproducibility

The morphological images of different samples were repeated independently at least three times, which all showed similar morphological features of the samples as shown in Fig. 2h–l, 6b, c and Supplementary Figs. 13–15, 17, 40–42. The confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) images of different samples were repeatedly independently at least three times, which all showed similar results as demonstrated in Figs. 1d, 6d, e and Supplementary Figs. 10, 38, 43.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data are available from the authors on request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Zheng, J., Yang, H., Xie, M. & Li, D. The π-acidity/basicity of cyclic trinuclear units (CTUs): from a theoretical perspective to potential applications. Chem. Commun. 55, 7134–7146 (2019).

Tekarli, S. M., Cundari, T. R. & Omary, M. A. Rational Design of Macrometallocyclic trinuclear complexes with superior π-acidity and π-basicity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 1669–1675 (2008).

Zheng, J., Lu, Z., Wu, K., Ning, G.-H. & Li, D. Coinage-metal-based cyclic trinuclear complexes with metal–metal interactions: theories to experiments and structures to functions. Chem. Rev. 120, 9675–9742 (2020).

Vaughan, L. G. Organogold chemistry. III. 2-Pyridylgold(I). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 92, 730–731 (1970).

Banditelli, G., Bandini, A. L., Minghetti, G. & Bonati, F. Metal derivatives of azoles. Part VII. Gold(I) derivatives of pyrazoles. Can. J. Chem. 59, 1241–1246 (1981).

Bovio, B., Bonati, F. & Banditelli, G. X-ray crystal structure of tris[μ−3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)pyrazolato-N,N′]trigold(I), a compound containing an inorganic nine-membered ring. Inorg. Chim. Acta 87, 25–33 (1984).

Raptis, R. G., Murray, H. H. & Fackler, J. P. The structure of [Au-μ-{3,5-(C6H5)2C3HN2}]3Cl2: a trinuclear mixed-valence gold pyrazolate complex. Acta Crystallogr. C Struct. Chem 44, 970–973 (1988).

Dias, H. V. R., Polach, S. A. & Wang, Z. Coinage metal complexes of 3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)pyrazolate ligand Synthesis and characterization of {[3,5-(CF3)2Pz]Cu}3 and {[3,5-(CF3)2Pz]Ag}3. J. Fluor. Chem. 103, 163–169 (2000).

Ni, W.-X. et al. Metallophilicity-driven dynamic aggregation of a phosphorescent gold(I)–silver(I) cluster prepared by solution-based and mechanochemical approaches. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 9532–9535 (2014).

Cored, J., Crespo, O., Serrano, J. L., Elduque, A. & Giménez, R. Decisive influence of the metal in multifunctional gold, silver, and copper metallacycles: high quantum yield phosphorescence, color switching, and liquid crystalline behavior. Inorg. Chem. 57, 12632–12640 (2018).

Lu, Z. et al. Aggregation-induced phosphorescence sensitization in two heptanuclear and decanuclear gold–silver sandwich clusters. Chem. Sci. 12, 702–708 (2021).

Upadhyay, P. K. et al. A phosphorescent trinuclear gold(I) pyrazolate chemosensor for silver ion detection and remediation in aqueous eedia. Anal. Chem. 90, 4999–5006 (2018).

Wang, H.-Y. et al. An Au(I)-based coordination/hydrogen-bond hybrid open framework for luminescence sensing of temperature and benzene. Sci. Bul. 67, 1229–1232 (2022).

Wei, R.-J. et al. Gold(I)-organic frameworks as catalysts for carboxylation of alkynes with CO. 2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 22720–22727 (2023).

Luo, J. et al. Selective and rapid extraction of trace amount of gold from complex liquids with silver(I)-organic frameworks. Nat. Commun. 13, 7771 (2022).

You, P.-Y. et al. Reversible modulation of interlayer stacking in 2D copper-organic frameworks for tailoring porosity and photocatalytic activity. Nat. Commun. 15, 194 (2024).

Schmidbaur, H. & Schier, A. A briefing on aurophilicity. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37, 1931 (2008).

Ni, W. et al. Approaching white‐light emission from a phosphorescent trinuclear gold(I) cluster by modulating its aggregation behavior. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 13472–13476 (2013).

Galassi, R. et al. Cupriphication of gold to sensitize d10–d10 metal–metal bonds and near-unity phosphorescence quantum yields. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 114, E5042–E5051 (2017).

He, G. S., Tan, L.-S., Zheng, Q. & Prasad, P. N. Multiphoton absorbing eaterials: eolecular designs, characterizations, and applications. Chem. Rev. 108, 1245–1330 (2008).

Denk, W., Strickler, J. H. & Webb, W. W. Two-photon laser scanning fluorescence microscopy. Science 248, 73–76 (1990).

Piston, D. Imaging living cells and tissues by two-photon excitation microscopy. Trends Cell Bio 9, 66–69 (1999).

Qin, Z. et al. Deep tissue multi-photon imaging using adaptive optics with direct focus sensing and shaping. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 1663–1671 (2022).

Kwon, J. et al. FeSe quantum dots for in vivo multiphoton biomedical imaging. Sci. Adv. 5, eaay0044 (2019).

Yu, J. H. et al. High-resolution three-photon biomedical imaging using doped ZnS nanocrystals. Nat. Mater. 12, 359–366 (2013).

Wang, H. et al. In vitro and in vivo two-photon luminescence imaging of single gold nanorods. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 102, 15752–15756 (2005).

Surender, E. M. et al. Two-photon luminescent bone imaging using europium nanoagents. Chem 1, 438–455 (2016).

Gao, N. et al. Shape-dependent two-photon photoluminescence of single gold nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C. 118, 13904–13911 (2014).

Chilukuri, B. et al. Polymorphic, porous, and host–guest nanostructures directed by monolayer–substrate interactions: epitaxial self-assembly study of cyclic trinuclear Au(I) complexes on HOPG at the solution–solid interface. J. Phys. Chem. C. 119, 24844–24858 (2015).

Schmidbaur, H. & Schier, A. Aurophilic interactions as a subject of current research: an up-date. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 370–412 (2012).

Grimes, T., Omary, M. A., Dias, H. V. R. & Cundari, T. R. Intertrimer and intratrimer netallophilic and excimeric bonding in the ground and phosphorescent states of trinuclear coinage metal pyrazolates: a computational study. J. Phys. Chem. A 110, 5823–5830 (2006).

Koshevoy, I. O. et al. Modulation of metallophilic bonds: solvent-induced isomerization and luminescence vapochromism of a polymorphic Au–Cu cluster. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 6564–6567 (2012).

Ghimire, M. M., Nesterov, V. N. & Omary, M. A. Remarkable Aurophilicity and photoluminescence thermochromism in a homoleptic cyclic trinuclear Gold(I) imidazolate complex. Inorg. Chem. 56, 12086–12089 (2017).

Omary, M. A. et al. Metal effect on the supramolecular structure, photophysics, and acid−base character of trinuclear pyrazolato coinage metal complexes. Inorg. Chem. 44, 8200–8210 (2005).

Wang, Z. et al. White‐light emission from dual‐way photon energy conversion in a dye‐encapsulated metal–organic framework. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 9752–9757 (2019).

Makarov, N. S., Drobizhev, M. & Rebane, A. Two-photon absorption standards in the 550-1600 nm excitation wavelength range. Opt. Express 16, 4029 (2008).

Xue, J., Wu, T., Dai, Y. & Xia, Y. Electrospinning and electrospun nanofibers: methods, materials, and applications. Chem. Rev. 119, 5298–5415 (2019).

Tian, T. et al. Durable organic nonlinear optical membranes for thermotolerant lightings and in vivo bioimaging. Nat. Commun. 14, 4429 (2023).

Topuz, F. & Uyar, T. Influence of hydrogen-bonding additives on electrospinning of cyclodextrin nanofibers. ACS Omega 3, 18311–18322 (2018).

Li, S. et al. Investigations of bisacodyl with modified β-cyclodextrins: Characterization, molecular modeling, and effect of PEG. Carbohydr. Polym. 134, 82–91 (2015).

Lim, D. C., Lopez‐Salido, I., Dietsche, R., Bubek, M. & Kim, Y. D. Size‐selectivity in the oxidation behaviors of Au nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 2413–2415 (2006).

Adamo, C. & Barone, V. Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: The PBE0. model. J. Chem. Phys. 110, 6158–6170 (1999).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 16, Revision C.01. Gaussian, Inc (2016).

Weigend, F. & Ahlrichs, R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 7, 3297 (2005).

Weigend, F. Accurate Coulomb-fitting basis sets for H to Rn. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 8, 1057 (2006).

Andrae, D., Häußermann, U., Dolg, M., Stoll, H. & Preuß, H. Energy-adjustedab initio pseudopotentials for the second and third row transition elements. Theor. Chim. Acta 77, 123–141 (1990).

Tomasi, J., Mennucci, B. & Cammi, R. Quantum mechanical continuum solvation models. Chem. Rev. 105, 2999–3094 (2005).

Humphrey, W., Dalke, A. & Schulten, K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–38 (1996).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Zhang, J. & Lu, T. Efficient evaluation of electrostatic potential with computerized optimized code. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 23, 20323–20328 (2021).

Liu, Z., Lu, T. & Chen, Q. An sp-hybridized all-carboatomic ring, cyclo[18]carbon: Electronic structure, electronic spectrum, and optical nonlinearity. Carbon 165, 461–467 (2020).

Sun, J. et al. Charge‐transfer exciton manipulation based on hydrogen bond for efficient white thermally activated delayed fluorescence. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1908568 (2020).

Hansen, K. R., Colton, J. S. & Whittaker‐Brooks, L. Measuring the exciton binding energy: learning from a decade of measurements on halide perovskites and transition metal dichalcogenides. Adv. Opt. Mater. 12, 2301659 (2024).

Passarelli, J. V. et al. Tunable exciton binding energy in 2D hybrid layered perovskites through donor–acceptor interactions within the organic layer. Nat. Chem. 12, 672–682 (2020).

Tian, T. et al. Large-area waterproof and durable perovskite luminescent textiles. Nat. Commun. 14, 234 (2023).

Wang, J.-Q. et al. Total structure determination of the largest alkynyl-protected fcc gold nanocluster Au110 and the study on its ultrafast excited-state dynamics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 18086–18092 (2020).

Fu, P. et al. One/two‐photon‐excited ESIPT‐attributed coordination polymers with wide temperature range and color‐tunable long persistent luminescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202309172 (2023).

Wei, J., Luo, J., He, Z., Zhang, Z. & Kuang, D. A new class of donor‐ π ‐acceptor phosphonium salt exhibiting intriguing thermally activated delayed fluorescence. Adv. Opt. Mater. 11, 2300328 (2023).

Shi, W.-Q. et al. Near-unity NIR phosphorescent quantum yield from a room-temperature solvated metal nanocluster. Science 383, 326–330 (2024).

Xia, R.-Q. et al. Strong visible light-absorbing BODIPY-based Cu(I) cyclic trinuclear sensitizer for photocatalysis. Inorg. Chem. Front. 9, 2928–2937 (2022).

Hu, F. et al. Molecular gold nanocluster Au156 showing metallic electron dynamics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 17059–17067 (2021).

Yuan, L., Lin, W., Chen, H., Zhu, S. & He, L. A unique family of rigid analogues of the GFP chromophore with tunable two-photon action cross-sections for biological imaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 10018–10022 (2013).

Demchick, P. & Koch, A. L. The permeability of the wall fabric of Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 178, 768–773 (1996).

Acknowledgements

This work is financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant 22336007 (G.O.), 22122612 (J.X.), 22305215 (T.T.), 22293050 (C.W.), 22293053 (C.W.) and GBRCE for Functional Molecular Engineering. The authors appreciate Professor Mei Pan’s help with MPEL spectra testing from the School of Chemistry at Sun Yat-sen University. Special thanks to the division of Materials & Micro-analysis and Organic & Pharmaceutical Analysis from the Instrumental Analysis and Research Center at Sun Yat-sen University, for the support in TEM, SEM and NMR analysis. Yu-Xin Chen extends her gratitude to Ms. Jiawen Ren for her generous contribution in creating the featured image for this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y-X.C., T.T., H.P., C.W., and G.O. designed the experiments. Y-X.C. and L.W. carried out the synthesis of Au3. T. T. and Y-X.C. carried out the fabrication of Au3-CD films. T.T. and H.P. carried out DFT and TDDFT calculations. The characterizations were carried out by Y-X.C., L.W., Y-J.T., T.T. and G.O. Y-X.C., C.W. and H.Y. completed multi-photon bio-imaging tests and cell validation assays. Y-X.C., T. T., J.X., C.W. and G.O. wrote the manuscript. All the authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Rossana Galassi and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, YX., Yu, H., Wu, L. et al. Unlocking multi-photon excited luminescence in pyrazolate trinuclear gold clusters for dynamic cell imaging. Nat Commun 15, 7356 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51753-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51753-4