Abstract

Ion selective membranes are fundamental components of biological, energy, and computing systems. The fabrication of solid-state ultrathin membranes that can separate ions of similar size and the same charge with both high selectivity and permeance remains a challenge, however. Here, we present a method, utilizing the application of a remote electric field, to fabricate a high-density of (sub)nm pores in situ. This method takes advantage of the grain boundaries in few-layer polycrystalline MoS2 to enable the synthesis of nanoporous membranes with average pore size tunable from <1 to ~4 nm in diameter (with in situ pore expansion resolution of ~0.2 nm2 s−1). These membranes demonstrate selective transport of monovalent ions (K+, Na+ and Li+) as well as divalent ions (Mg2+ and Ca2+), outperforming existing two-dimensional material nanoporous membranes that display similar total permeance. We investigate the mechanism of selectivity using molecular dynamics simulations and unveil that the interactions between cations and the sluggish water confined to the pore, as well as cation-anion interactions, result in the different transport behaviors observed between ions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The precise fabrication of nm and sub-nm pores in ultrathin films (one to several atomic layers) will enable membranes with both high selectivity and permeance. The transport behavior of ions and small molecules confined to nm-scale pores or channels found in such membranes differs dramatically from that measured in bulk liquids. Under confinement, the discrete nature of molecules and atoms, ionic correlations, and long-range electrostatic interactions as well as specific adsorption play large roles in the overall dynamics1,2,3,4,5, which can be manipulated via the nanopore characteristics to optimize species selectivity. If successfully fabricated on a large scale, nanoporous membranes would be applicable to fuel cells, osmotic power generators, and separation processes6,7,8,9,10,11. They would be especially useful for ion separations, which can enable efficient water decontamination, water softening, and resource recovery from aqueous solutions12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20.

To date, the fabrication of arrays of nm pores on ultrathin membranes made from two-dimensional (2D) materials, such as graphene and transition metal dichalcogenides, has been demonstrated with electron and ion irradiation, as well as oxygen plasma etching21,22,23,24,25,26,27. These methods have been used to create pores in the sub-nm range but have drawbacks including the complexity of the instruments involved and significant pore-size variation within a given device. Nanopores can also be fabricated in ultrathin membranes via bottom-up methods by introducing defects during crystal growth21,28,29. All of these membrane fabrication techniques are based on ex situ methods, which suffer from pore blocking by trapped nanobubbles, the introduction of ambient contaminants, and often display a large degree of variation between devices30,31.

Moreover, the resulting 2D material membranes have yet to demonstrate significant selectivity for different cations, especially of the same charge, even though they are excellent at separating cations from anions2,4,7,14,20,32. Without adding additional active elements, such as conical nanoporous substrates33 or nanobubbles31, the selectivity (the higher permeance of one ion relative to all others) of nanoporous 2D material membranes for monovalent ions (K+, Li+, Na+ and Cs+) has remained around two (after accounting for trends in bulk mobility)21,25,34. Existing methods and starting material design have limited the performance of nanoporous membranes. Furthermore, these methods have been applied to only monolayer (never few-layer) membranes, limiting the intrinsic selectivity. Computational efforts also have mainly focused on the transport properties of ions in monolayer membranes and have identified the effect of ion dehydration as the primary driver of selectivity35,36. There has been little work studying the interplay between ion transport and water dynamics, however, which we find is one of the driving factors for monovalent cation selectivity in our few-layer nanoporous films.

Here we develop an in-situ fabrication method to generate (sub)nm pores with tunable pore size and density by applying a transverse electric field across polycrystalline membranes. This method exploits the electrostatic and electrochemical effects from the strong electric field formed across the 2D semiconductor, molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) with the configuration of electrolyte gating37. The porosity is determined by the strength and duration of the applied electric field, as well as the atomic features of the starting material. Using few-layer mechanically exfoliated MoS2 and vertically aligned MoS2 films for comparison, we pinpoint the critical role of grain boundaries in polycrystalline MoS2 for the generation of nanopores. We demonstrate an all-solid-state membrane with average pore size ranging from <1 nm to ~4 nm in diameter via in situ tuning. Our pore fabrication procedure expands the total pore area at a rate down to ~0.2 nm2 s−1, allowing us to control the pore sizes with sub-nm precision.

Previous work has shown that nm-scale pores can be formed electrochemically in 2D materials, such as MoS2 and graphene38,39. Single pores, as well as porous membranes, can also be formed electrochemically in thin films such as SiN, although the mechanism in this case differs from that in 2D materials such as MoS240,41,42. For SiN, the application of large voltages leads to a sudden controlled dielectric breakdown, resulting in localized heating and subsequent material degradation. In MoS2, the application of order-of-magnitude smaller voltages leads to a gradual localized electrochemical etching at specific hot-spots, likely grain boundaries or sulfur vacancies38.

In all previous accounts with 2D materials, the pores are formed one at a time, which is beneficial for certain sensing applications43, but could be a shortcoming for ion-separation membranes. Here, we demonstrate for the first time that, with the nanoscale features of polycrystalline MoS2, densely porous membranes can be fabricated in situ with sub-nm control. Furthermore, we demonstrate that pores in multi-layer films can be formed electrochemically, whereas in previous studies only monolayers were used. We show that pore creation in single-crystal, few-layer MoS2 is significantly more difficult to control.

Owing to its combination of high surface charge density, tight pore-size distribution, and nm-scale thickness, MoS2 nanoporous membranes demonstrate selective transport of both monovalent and divalent cations. The level of ion selectivity of nanoporous, few-layer MoS2 membranes is among the highest for ultrathin solid-state membranes to date, compared to reported membranes with similar absolute conductance. We use classical molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to elucidate the mechanism of the experimentally measured ion selectivity. We find that the unique interactions between cations and the sluggish water confined to the pore, as well as cation-anion interactions combine to result in qualitatively different transport behavior for KCl, NaCl, LiCl, CaCl2 and MgCl2 through nanoporous MoS2. Such behaviors are suppressed in monolayer films, explaining the high selectivity measured in this study compared to existing literature using monolayer graphene and MoS2 membranes21,25,34.

Results

Pore creation in polycrystalline MoS2 films

We choose MoS2 as our starting material due to its nm-scale thickness, its electrochemical activity and tunability via the material synthesis parameters. The crystallinity of the pristine membrane determines its response under an applied electric field. Grain boundaries and edge sites, with dangling bonds and defects, are well-known chemically active sites in MoS2, whereas the basal plane of MoS2 is relatively inert44,45. We hypothesize that the boundaries between MoS2 crystallites act as seeding points where, upon partial degradation, pores are formed. Therefore, chemical vapor deposition (CVD) grown few-layer MoS2 films (CVD-MoS2) with a high-density of grain boundaries and mechanically exfoliated MoS2 (ME-MoS2), which are single-crystalline, are chosen for direct comparison.

Few-layer (~8 nm) MoS2 films are grown via molybdenum sputtering and subsequent sulfurization46,47,48. Both ME- and CVD-MoS2 are transferred to a silicon nitride (SiN) chip with a single 300–500 nm diameter pore, over which the film is freely suspended (Supplementary Fig. 1). Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) images show that the CVD-MoS2 films have nanoscale surface topography due to the polycrystalline nature of the thin film, in contrast to ME-MoS2, which is atomically smooth, absent blisters and wrinkles (Supplementary Fig. 2). We choose sub-micron apertures for all experiments below, but we note that the transfer method and pore fabrication methods reported here are scalable to significantly larger areas. The CVD-MoS2 films, despite the large density of grain boundaries, can be suspended over micron-scale apertures (Supplementary Fig. 3). High-resolution scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) imaging is conducted on both CVD- and ME-MoS2. Real-space images and selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) of ME-MoS2 confirms the single crystalline nature of the thin film (Fig. 1a, b). In stark contrast, CVD-MoS2 is highly polycrystalline with nm-scale domains as shown in the scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) image and SAED (Fig. 1c, d). The grain boundaries in CVD-MoS2 can extend entirely through the membrane, as evidenced by cross-section transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Fig. 1e). Although chemically active sulfur vacancies exist in ME-MoS2, they are unlikely to stack vertically from layer to layer and thus cannot enable pore formation in multilayer films49,50. CVD-grown monolayer MoS2, tested in a previous work38, has similar behavior to CVD-grown polycrystalline MoS2, likely because S vacancies accelerate the electrochemical formation of single isolated pores.

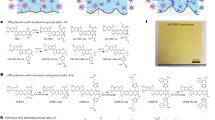

STEM images and cartoons of few-layer single crystal ME-MoS2 (a, b) and polycrystalline CVD-MoS2 (c, d) with diffraction patterns inset. Continuous rings evident in the CVD-MoS2 diffraction pattern indicate that the grains are randomly rotated in-plane with respect to each other, and Moiré patterns evident in real-space images indicate that grains are partially overlapping. e Cross-section TEM image of polycrystalline MoS2, with a grain-boundary marked in red. f Change in ionic current for a given (constant) bias voltage applied across the membrane. A rapid, but controllable, increase in current is apparent for CVD-MoS2 at 0.4–0.5 V (inset), whereas a significantly more rapid, and difficult-to-control breakdown occurs for ME-MoS2 at 1.75-2 V. Partial oxidation of the film does not have a significant effect on the breakdown voltage. Device schematic is inset, showing ion accumulation leading to large electric fields across the membrane. g Polycrystalline MoS2, after electrochemical etching, showing a single (out of many) ~1 nm diameter pore. Scale bars are 5 nm in a, c and g; 2 nm-1 in (a) and (c) inset; and 10 nm in e. Source data for (f) are provided as a Source Data file.

The SiN chips with MoS2 films are mounted in a custom flow cell and separate two reservoirs with 1 M KCl electrolyte, electrically connected with Ag/AgCl electrodes (Fig. 1f, inset). The as-transferred MoS2 films are impermeable to K+ and Cl- ions, in agreement with previous work7,25,38 (Supplementary Fig. 4). Nanopores are created by the application of a remote electric field across the membrane (the membrane itself is not connected to the electrical circuit). The bias across the membrane leads to charge accumulation and corresponding membrane polarization51. Past a threshold voltage, the large interfacial electric field across the membrane induces the removal of atoms from the MoS2 films resulting in the formation of (sub)nm pores.

For CVD-MoS2, as the bias voltage exceeds the threshold value of 0.4–0.5 V, the ionic current through polycrystalline MoS2 increases rapidly and irreversibly (Fig. 1f, Supplementary Fig. 4). With increasing voltage, the rate of increase rises. The breakdown voltage of ME-MoS2 is significantly larger than that of CVD-MoS2 and the high threshold voltage required for ME-MoS2, results in rapid and unpredictable etching. The minimum rate of current change for ME-MoS2 (~2 nA s-1 at 1.7 V) is ~20 times that of CVD-MoS2 (~0.1 nA s-1 at 0.4 V), making the process much less controllable. To isolate the role of film morphology over surface chemistry or wettability, we subject both CVD and ME-MoS2 films to remote O2 plasma treatment. The O2 plasma partially oxidizes the top-surface of the MoS2 films, without destroying the overall integrity (Supplementary Fig. 1)52. After plasma treatment, the voltage gap between the threshold of CVD and ME-MoS2 remains. As shown in Fig. 1g, we find that the polycrystalline MoS2 films are amenable to the controllable fabrication of ~1 nm diameter pores. Using a simple one-pore model (Supplementary Methods), we determine that, at a threshold voltage of 0.4–0.5 V, the total pore area increases at a rate of ~0.2 nm2 s-1.

The importance of grain boundaries is also confirmed with vertically aligned CVD-MoS2 films, which are grown using a thicker Mo seed layer (in this case 15 nm)47. In the vertically aligned CVD-MoS2 films, the MoS2 layers are easily identifiable via TEM imaging (Supplementary Fig. 5). The relative orientations of these layers can then be used to distinguish neighboring grains. After electric field driven pore creation, we find that the MoS2 degrades predominantly at grain boundaries, further confirming our hypothesis that the exposed atoms at the grain boundaries are more electrochemically active (Supplementary Fig. 5). We conclude that, in contrast to isotropic etching, our technique leaves the CVD-MoS2 lattice mostly intact, with pores forming preferentially at grain boundaries.

The dimension of the pores can be controlled via external field strength and application time. In the following, we tune the porosity by applying discrete pulses above the threshold voltage. The morphology of the films after a single 5 ms, 1.5 V pulse and after many 10 ms, 1.5 V pulses differ dramatically, which we characterize with ex situ STEM (Fig. 2a–f). By applying a series of voltage pulses, we increase the porosity, and therefore the conductance, of the film (Fig. 2g–i). We determine the upper limit of the pore diameter by identifying and then imaging the few largest pores in a given membrane. In Fig. 2a, the largest pores of a film subjected to a single etching step are outlined, and their corresponding high-resolution images shown in Fig. 2b, c, where none exceed 1.5 nm in diameter. This pore size is suitable for the separation of small ions, which we demonstrate in the following section. A film subjected to 10 pulses is shown in Fig. 2d–f, where the largest pore is ~4 nm in diameter, which could be suitable for the separation and detection of macromolecules (such as proteins or nucleotides)43,53.

STEM images of porous MoS2 after (a–c) a single electrical pulse of 5 ms at 1.5 V and after (d–f) ten electrical pulses of 10 ms each at 1.5 V. Only the few largest pores are identified, and images taken, as these pores dominate the ionic current through the membrane. g IV traces and their corresponding conductance values (h) taken after each pulse for the film shown in (d–f). i Pore size distributions for four different membranes, with different conductance values (G) after different numbers (N) of 1.5 V, 5–10 ms voltage pulses. Error bars for the pore sizes in (i) are determined by the pixel size of the corresponding STEM images. Scale bars are 100 nm in (a) and (d) and 5 nm in (b, c) (e, f). Source data for (g–i) are provided as a Source Data file.

We calculate pore size distributions for four different membranes via segmentation and thresholding of images of the entire free-standing MoS2 area (Supplementary Fig. 6). The pore-size distributions (Fig. 2i) for membranes with larger conductance values have more (going from ~100 – ~2000 pores µm-2 for 1 – 10 pulses) and larger (from ~5 Å to 4 nm) pores, indicating that the applied electric field simultaneously forms new pores and expands existing pores. The measured conductance of KCl through the membranes is in approximate agreement with the expected conductance for a given size distribution (Supplementary Fig. 7), indicating that the membrane is mostly unobstructed, and the ionic current is determined by the porosity of the membrane as opposed to trapped contaminants or bubbles.

Ion transport characterization

The size of the MoS2 nanopores ( ~ 5 Å - 4 nm) fabricated here are commensurate with the diameter of hydrated ions ( ~ 7-9 Å). As such, the unique solvation characteristics of ions are paramount in determining their dynamics confined in the MoS2 membrane54. The transport behaviors of five different salts (1 M KCl, NaCl, LiCl, MgCl2 and CaCl2) are probed by measuring current-voltage traces for a given membrane. We find that, across all 15 devices tested for KCl/MgCl2 selectivity, the conductivity ratio between KCl and MgCl2 increases dramatically with membrane resistance to KCl (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Table 1), and correspondingly with respect to decreasing pore size. By comparing the conductance values of the 15 (horizontally aligned) devices tested for KCl/MgCl2 selectivity to the corresponding pore size distributions calculated separately in Fig. 2, we determine that past a maximum pore size of ~3 nm, the selectivity approaches unity. This trend holds for thicker, vertically aligned MoS2 films (Supplementary Fig. 9). Variation between devices generally can be ascribed to differences in pore size distributions as a result of the electrochemical etching process, which could be improved by controlling the domain uniformity of the CVD grown MoS2 film. After pore generation, smaller pore sizes lead to both lower conductivities and higher selectivity, as discussed above in Fig. 2. Each device tested has a slightly different pore size distribution, and thus slightly different ion transport characteristics. I–V curves for all devices can be found in Supplementary Fig. 8, Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Fig. 11.

a KCl/MgCl2 selectivity for all 15 horizontally aligned CVD-MoS2 devices tested, plotted against membrane resistance to KCl. The dotted red curve is a guideline. The MgCl2 conductance for the datapoint with the highest KCl/MgCl2 selectivity is below our detection limit, and thus we can only establish a lower bound. b Representative IV curves used to determine the membrane conductance values (this set corresponds to Device 12). c Ion conductance values for three devices, showing enhanced conductance of KCl relative to all other salts even after (d) scaling using bulk conductance values. e Unnormalized conductance ratio of KCl and LiCl plotted against conductance of 1 M KCl through existing nanoporous 2D material membranes (see Supplementary Table 3). f Interactions between KCl and MgCl2. Blue curve shows measured conductance values as a function of K+ to Mg2+ molar ratio. Black curve shows the predicted values, assuming KCl and MgCl2 do not interact with the other cation or the membrane, calculated using the pure KCl and pure MgCl2 conductance measurements. Red markers show that the bulk conductance changes <5% as a function of the K+ to Mg2+ molar ratio. Error bars in (b) are given by trace-retrace (N ≥ 3) for all curves. Error bars in (c, d) (f) are determined by cycling through electrolytes (N ≥ 2), with multiple (N ≥3) IV curves measured for each electrolyte. Source data for (b–d) and (f) are provided as Source Data files. Source data for (a) and (e) are provided in Supplementary Information.

We test the conductance of the entire suite of salts in a smaller subset of three membranes, measuring multiple current-voltage traces for each salt (Fig. 3b). Again using Fig. 2 as a reference, we conclude that the pores in these devices are in the 5 Å-2 nm range. For each membrane, we measure the conductance going from small to large hydration enthalpy (K+ to Mg2+), then back from large to small (Mg2+ to K+) to avoid artifacts from slow changes in conductance due to pore fouling (Supplementary Fig. 10). We find that the conductance of all salts through the MoS2 nanopores is suppressed relative to KCl (Fig. 3c). We also test the relative conductance Cs+ and Rb+ in a separate device and find that the trend (reduced conductance for increased hydration radius) continues for Rb+ and matches previous work32,35 for Cs+ (Supplementary Fig. 11).

We define the pore-induced selectivity, accounting for differences in bulk conductivity, as

where \({{{{\rm{G}}}}}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}\) and \({G}_{{kcl}}\) are the measured conductance of a given salt and of KCl, respectively; and \({k}_{i}\) and \({k}_{{kcl}}\) are the bulk conductance of a given salt and of KCl, respectively. Even after accounting for the contribution of the bulk conductance, the selectivity remains (Fig. 3d). We emphasize in particular the selectivity between the monovalent salts KCl, NaCl and LiCl, which is among the highest in ultrathin 2D material membranes to date. The ion selectivity of thicker, layered membranes with angstrom-scale 2D channels, such as those made from liquid-phase exfoliation of graphene and MoS2, tends to be higher (Supplementary Fig. 13). Due to the high density of nanopores in the polycrystalline MoS2 films, the absolute conductance is a factor of >2 higher than nanoporous membranes with the same selectivity (Fig. 3e). This enhancement may also be a result of the fact that, because we test few-layer as opposed to monolayer 2D material membranes, a similar selectivity can be achieved with larger pore diameters, a point which we corroborate using MD simulations in the following section.

It is well-established that under nm-scale confinement, ion-ion correlations play a large role in the transport behavior of charged species55. We cannot assume, therefore, that the difference in conductance between salts is a function of the cation mobilities alone. To isolate the relative contributions of cation and anion to the total current, we measure the membrane potential with 1 M and 0.1 M electrolytes in the two reservoirs, which is easily translated into the transference number, \({t}_{+}\)(Supplementary Methods). For monovalent ions, the current is dominated by the cation (\({t}_{+} \sim\) 0.8) and to similar degrees for KCl, NaCl and LiCl (Supplementary Fig. 15). It is surprising that the cation/anion selectivity is similar for LiCl and KCl, given the lower overall conductance of LiCl. The puzzle is resolved however, when considering that as the nanopore is occupied by cations the negative surface charge is partially screened, reducing the energy barrier for anions: a higher concentration for K+ inside the nanopore results in a higher concentration of Cl-. This theory is verified in the following section using MD simulations. The transference number for the divalent ions (\({t}_{+} \sim\) 0.3) is suppressed relative to the monovalent ions. The mechanism of this qualitative shift is elucidated by observing that the presence of Mg2+ in a mixed KCl/MgCl2 solution suppresses the conductance of K+ (Fig. 3f), indicating that Mg2+ is adsorbed on or is stuck inside the MoS2 membrane. The adsorbed cation reduces the magnitude of, or possibly inverts, the intrinsically negative surface charge, creating a more (less) favorable environment for the anion (cation).

Molecular dynamics simulations: mechanisms of selective ion transport

To further understand the dynamics of ions and unveil the origin of ion selectivity in the MoS2 nanopores, we carry out classical MD simulations. In the simulations discussed below, two reservoirs with equal concentration of 1 M KCl, NaCl, LiCl or MgCl2 are separated by a single (1L) or six-layer (6L) MoS2 film through which a 1 or 2 nm pore is drilled (Fig. 4a–c). The pore is terminated by both Mo and S atoms to approximate the most likely pore configuration, as was recently measured experimentally23, and a negative partial charge is added to all terminating atoms to fix the surface charge at -50 mC m-2 7. A constant electric field is applied perpendicular to the membrane to generate net ion flux through the film. Further simulation details can be found Supplementary Information Methods.

MD simulation snapshots of a (a) 6L-1 nm MoS2 film and (b) 1L-1 nm film separating two 1 M KCl reservoirs. Dotted black lines indicate locations of the first and second solvation shell of a Mg2+ ion. A single pore (c) is drilled in the center of all MoS2 films. d Ion selectivity for KCl, NaCl, LiCl and MgCl2 for 6L-1 nm, 6L-2 nm and 1L-1 nm MoS2. Decomposition of the total current into its (e) cationic and (f) anion components. Cations are normalized to their bulk mobility values, and anions scaled by their total concentration (a factor of two higher for MgCl2). g Probability density functions, normalized to K+, for each cation inside the 6L-1 nm pore. Three distinct regions are apparent, corresponding to different hydration levels. h Cationic current as a function of radial position for all four cations. The current is dominated by the ions in the one-layer water region, even though a higher concentration of cations for K+ can be found directly adjacent to the pore. i Radial profiles of the water diffusion coefficient in the 6L-1 nm and 6L-2 nm pores (without the presence of an applied bias or ions) as compared to the diffusion of water in the bulk reservoir. The diffusion of water in both pores is suppressed, especially near the pore edges, but is significantly more suppressed for the 6L-1 nm pore. Error bars in (d–f) are given by the standard error of the given parameter measured over the entire simulation trajectory. Ion trajectory data for (d–h) and full trajectories for (i) are provided as Source Data files.

We first calculate the total ionic current for each salt through 6L-1 nm, 6L-2 nm and 1L-1 nm MoS2. After accounting for the bulk conductivity using Eq. (1), the transport of KCl through 6L-1 nm MoS2 is significantly enhanced over LiCl (\({S}_{p}=0.67\)) and MgCl2 (\({{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}=0.54\)) and is slightly higher than NaCl (\({{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}=0.92\)), in qualitative agreement with our experimental results (Fig. 4d). We see no such selectivity for either 6L-2 nm MoS2 or, surprisingly, 1L-1 nm MoS2.

The ionic current is proportional to the average drift velocity of the ions and the total ion concentration (Supplementary Methods). Analyzing 6L-1 nm MoS2, we observe that the average velocities of Li+ and Na+, relative to that of K+ after accounting for bulk mobility, are undiminished and the velocity of Mg2+ only marginally so; at first glance, it appears that the selectivity between cations (Fig. 4e) derives from number of charge carriers (ion concentration), which we find varies significantly (Supplementary Table 4). The variation in the number of charge carriers is explained by the ability of each ion to enter the pore, which in turn is based on the ease with which it sheds its first and second hydration shells. This mechanism is the common explanation for various exotic effects in ion transport21,35,36. As we explain below, however, concentration inside the pore is not the ultimate cause of cation selectivity.

The probability density function (PDF) of ions inside 6L-1 nm MoS2 has three distinct regions, corresponding to three discrete ion hydration levels: ions in direct contact with the pore wall (region I), ions separated from the wall by a single water layer (region II) and ions separated from the wall by two water layers (region III) as shown in Fig. 4g. The distance between peaks in the PDF and the location of the first water (Ow) layer correlates with the associated Mx+-OW coordination distance in the bulk (Supplementary Fig. 16). As determined by the PDFs displayed in Fig. 4g, only K+ (and Na+ but to a significantly reduced degree) occupies region I, corresponding to direct ion-wall contact. Na+, Li+ and K+ all show significant density in region II, whereas Mg2+ is only able to occupy region III, corresponding to two water layers between the ion and the pore wall. We also perform simulations with CaCl2 and find that the behavior of this salt is nearly identical to that of MgCl2 (Supplementary Fig. 18). These results match expectations, given the relative hydration energies of the different cations56. The concentration of K+ is higher because it occupies a larger fraction of the pore.

The K+ ions in direct contact with the pore wall do not, however, contribute significantly to the current, as they are trapped at the surface and their mobility approaches zero (Supplementary Fig. 19b). Instead, the vast majority of the current for all ions is from the second and third regions, where ions are separated from the pore wall by one to two layers of water (Fig. 4h). Looking at these regions alone, we see that even though the monovalent ions have similar concentrations, the K+ current outstrips that of Na+ and especially Li+. After normalizing by bulk mobility, the average velocity of monovalent cations goes as K+ > Na+ > Li+ (Supplementary Fig. 17) for this region. The observed selectivity between ions is not a function of the equilibrium concentration inside the pore, as was hypothesized previously, but is a dynamical process wherein the hydration energy of a given cation affects its mobility in the one- and two-layer of water region of the pore.

This dynamical effect is based on the relative ease with which a given cation exchanges its inner hydration shell and is impacted by the position the ion occupies inside the pore. We find that water molecules inside the 6L-1 nm MoS2 pore have a significantly reduced diffusion coefficient relative to that measured in the 6L-2nm MoS2 or the bulk reservoir (Fig. 4i, Supplementary Fig. 20). Water molecules, due to their interaction with the pore wall, are nearly trapped in place and are unable to travel with the transporting ion (Supplementary Fig. 21). This has two effects: first, ions closer to the wall move more slowly. The selectivity between K+ and Na+ is a result of their relative preferred positions in the pore: K+ is closer to the center, where the water moves more freely and enables the ion to move faster (Fig. 4i). Second, the sluggish water makes the rapid exchange of the inner hydration shell a larger component of ion mobility compared to the bulk case, where the inner hydration shell is partially carried along with the ion57. We calculate the energy penalty for the exchange of the inner hydration shell for each cation by performing a Boltzmann-inversion on the cation-oxygen radial distribution functions; matching the drift velocity results, the order goes as K+ ~ Na+ < Li+ < Mg2+ (Supplementary Fig. 22). We conclude that inter-cation selectivity is determined by the preferred ion position and the rate of hydration shell exchange in the uniquely sluggish water inside the pore. This result highlights the role of the confining material, mediated through water friction, on ion transport. For example, we expect dramatically lower selectivity in hydrophobic nanochannels, such as carbon nanotubes58, due to the reduced friction experienced by confined water. We note that the transport dynamics of MgCl2 are significantly different than the monovalent ions and underestimate the experimentally recorded selectivity. This is likely because our simulations are strictly classical and thus do not incorporate the effects of ion adsorption.

No cationic selectivity is observed for the monolayer film, in agreement with existing literature for sub-nm pores in monolayer MoS234,59. Examining the velocity profiles of cations in the monolayer pore we find, after normalizing to their bulk values, little difference between ions. The thickness of the monolayer membrane (0.63 nm) is only slightly larger than the inner hydrated diameter of the cations, 0.4–0.54 nm, and smaller than the second hydration shell, 0.83–0.96 (Supplementary Fig. 16). We infer that ions are partially hydrated by water molecules located outside the membrane, reducing the effect of confinement as shown in the snapshot image in Fig. 4b. Supporting this claim, we find that the peaks in the radial ion PDF for the monolayer pore are shifted to the right (the ions more easily occupy the edge of the pore) and the mobility of ions adjacent to the pore edge is not reduced (Supplementary Fig. 23) indicating that the pore wall hardly affects ion transport. We also note that two factors influence the total resistance felt by ionic species traveling through a single nanopore, the access resistance, \({R}_{{access}} \sim \frac{1}{d}\), and the pore resistance, \({R}_{{pore}} \sim \frac{4L}{{{{\rm{\pi }}}}{d}^{2}}\), where \(L\) is the pore length and \(d\) the pore diameter60. For monolayer membranes with pore diameter ~1 nm, the access resistance dominates, and any selectivity induced by the pore itself is reduced.

Now we turn to the role of the anion in the selectivity between different salts. As in our experiments, the transference number in our simulations with monolayer salts remains relatively constant (Supplementary Fig. 24): the flux of K+ is higher than that of Na+ or Li+, but so is the flux of (K+)Cl- relative to (Na+)Cl- and (Li+)Cl- (Fig. 4f). For anions, this variation is a function of both velocity and total concentration. There are more chloride anions in the center of the pore for K+ and Na+ compared to Li+ or Mg2+, and the total concentration varies significantly (Supplementary Table 4 and Supplementary Fig. 17). Although the anion velocity profiles are identical for each salt, the concentration distributions vary. The velocity of ions increases near the pore center, leading to higher average mobilities for (K+)Cl- and (Na+)Cl- (Supplementary Fig. 17). The variation in concentration can be understood by observing that the 1 nm pore induces a high degree of ion-ion interactions between cation and anion. Two oppositely charged ions are strongly coupled when their internuclear distance \({{d}}_{{ij}}\) is less than the Bjerrum length \({{{{\rm{l}}}}}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}=\frac{{{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{2}}{4{{{\rm{\pi }}}}{{{{\rm{\epsilon }}}}}_{0}{{{{\rm{\epsilon }}}}}_{{{{\rm{r}}}}}{{{{\rm{k}}}}}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}{{{\rm{T}}}}} \sim 0.7\) nm61. For 6L-1 nm MoS2, independent of the salt, chloride ions are paired with an adjacent cation for nearly half the total time it takes to permeate through the pore. Ion-ion interactions are effectively non-existent for 1L-1 nm and are reduced in the 6L-2 nm MoS2 (Supplementary Fig. 25). We conclude that, for long and narrow (<2 nm) negatively charged pores, a high degree of ion coupling takes place. This coupling results in a higher concentration of anions (near the center of the pore) due to the strong electrostatic attraction between cation and anion. Finally, we note that a marginal degree of selectivity between divalent and monovalent salts exists in ~1 nm pores in multilayer membranes with sufficient surface charge, even if only electrostatic effects (Supplementary Section 7) are considered. No selectivity between monovalent ions can exist in this simplified system, however.

Discussion

In summary, we present an in situ electrochemical method for the fabrication of nanoporous membranes using polycrystalline MoS2. The method builds upon previous electroporation techniques, such as dielectric breakdown in SiN thin films and electrochemical etching of monolayer single crystals. We exploit the high density of grain boundaries in few-layer polycrystalline MoS2 to create thin films with a correspondingly high density of nanopores. These membranes exhibit selectivity for small monovalent and divalent cations, showcasing their potential for ion separation applications. As a result of the dense array of nanopores in the MoS2 membranes, the absolute flux outstrips existing devices that display similar levels of selectivity. This feature makes these membranes a more practical device for ion separations. MD simulations provide insights into the underlying mechanisms responsible for observed selectivity. We find that a combination of the role of the sluggish water confined to the pore combined with cation-anion pairing drives the selectivity between ions.

Methods

MoS2 synthesis

We follow a standard synthesis procedure for CVD-MoS247. A Si/SiO2 wafer is diced into pieces, solvent-cleaned, baked at 120 deg. C and plasma treated (YES-G1000) to remove residual organics and render the chips hydrophilic. A thin Mo film is deposited using magnetron sputtering (AJA ATC Orion 8 UHV Sputtering System) at 30 W and 1 mTorr with 30 s.c.c.m Ar flow. The deposition rate is determined to be 4 nm min-1 under these conditions. The Mo film is then sulfurized via chemical vapor deposition. A quartz boat with excess sulfur powder is loaded immediately upstream of the oven with the Mo film in the center; a separate heat belt is used to control the sulfur temperature. The one-inch tube furnace is pumped down and purged multiple times with Ar gas. The Ar flow rate is then held at 50 s.c.c.m. and the pressure is ~1 Torr. The furnace is heated to 300 deg. C and held for 1 h, after which it is ramped to 750 deg. C at 15 deg. C min-1. The heating belt upstream of the furnace is ramped quickly to 140 deg. C. to vaporize the sulfur. After 10 min, the oven and heating belt are cooled naturally.

MoS2 transfer onto SiN chips

A thin layer of PMMA (Nano 495) is spin-coated (3000 rpm for 1 min) on a freshly synthesized MoS2 thin film then baked on a hot plate set at 150 deg. C. A diamond-tipped scribe is used to etch ~1 mm squares in the polymer coated film. A portion of the chip is then submerged slowly in water, at which point the MoS2 film easily delaminates from the SiO2 chip. We transfer 1:1 EtOH:H2O into the water containing the floating MoS2 films, then scoop the film with a 3 mm SiN TEM grid (Norcada) with a single 300–500 nm diameter hole drilled via focused ion beam (TESCAN LYRA3, or ThermoFisher Scientific Helios 5CX) in the center. The chip is left to dry, then cleaned in acetone held at 60 deg. C for 12 h, then IPA and ultrapure water and blow dried with N2.

Mechanical exfoliation and transfer onto SiN chips

We follow a hybrid of procedures outlined in previous work to transfer to mechanically exfoliated MoS262,63. Few-layer MoS2 crystals (SPI supplies) are thinned using Nitto blue tape. PDMS (Sylgard 184 elastomer), stamps are prepared on clean Si wafers, then peeled off and transferred to a glass slide, with the side facing the Si facing up. The flakes are transferred to the PDMS and imaged. Using a micrometer, we adjust the position of the stamp to align with the SiN window while imaging using an optical microscope (Olympus DSX1000). The PDMS is brought down to contact the SiN chip, then very slowly raised, leaving the target flake covering the SiN pore.

Pore creation and ion conductance tests

All buffers and electrolytes are degassed and <20 nm filtered with Whatman Anotop syringe filters (Millipore Sigma). The SiN chip is loaded into a custom-built flow cell with reservoirs bridged by freshly chlorinated Ag/AgCl electrodes and is wetted with EtOH. We then exchange the buffers with 4:1, 1:1, 1:4, and 0:1 EtOH:H2O. After 20 min, we slowly run 1 M KCl through both sides of the reservoir until the solution is entirely exchanged. The electrodes are connected to a home-built amplifier with which we record current-voltage traces. To open pores, the voltage is ramped with 15–50 mV steps, brief 5–10 ms, 1.5 V pulses are applied across the film. After testing, the chip is rinsed with water, then solvent-cleaned again to remove adsorbed organics.

Characterization of MoS2 film

Raman spectroscopy is carried out using a HORIBA LabRAM HR Evolution Confocal Raman Microscope. Scanning electron microscopy is performed using a Carl Zeiss Merlin SEM. To perform STEM measurements, we use a JEOL JEM-ARM200CF at 80 kV; and for TEM measurements, a Tecnai F30 microscope at 300 kV. AFM is carried out using an Asylum Research Oxford Instruments Cypher ES AFM.

MD and finite element simulations

Full details of the MD simulations are detailed in Supplementary Methods. We construct the electrolyte (1 M KCl, NaCl, LiCl, MgCl2) reservoirs in packmol64 and Visual MD (VMD version 1.9.4a53) with TopoTools65, and run the simulations in LAMMPS (2017)66. We first equilibrate the simulation using an NPzT ensemble, then run an NVT ensemble for 5–20 ns, depending on the speed of convergence. We use MDAnalysis67 to parse the resulting trajectories. Finite element simulations are detailed in Supplementary Notes. They are performed using COMSOL Multiphysics version 6.0.0.354 with the Transport of Diluted Species and Electrostatics modules.

Materials and reagents

Acetone: Fisher Chemicals, 99.5%. Ethanol: Fisher Chemicals, certified denatured, 83.8–87.2%. Isopropanol: Fisher Chemicals, 99.9%. KCl: Sigma Aldrich, 99.0-100.5%. NaCl: Sigma Aldrich, 99.5%. LiCl: Oakwood Chemicals, >99%. MgCl2·6H20: Chem Impex, 99–102%. CaCl2: Acros Organics, 96%. RbCl: Thermo Scientific, 99%. CsCl: Sigma Aldrich, 99.0%. Sulfur: Sigma Aldrich, 99.98% trace metals basis.

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of the study are included in the main text and supplementary information files. Raw data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request. Source Data file has been deposited in Zenodo under the DOI link https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13117482.

Code availability

Code for processing current-voltage traces and generating and processing molecular dynamics trajectories are available upon request.

References

Bocquet, L. & Charlaix, E. Nanofluidics, from bulk to interfaces. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 1073–1095 (2010).

Faucher, S. et al. Critical knowledge gaps in mass transport through single-digit nanopores: a review and perspective. J. Phys. Chem. C. 123, 21309–21326 (2019).

Bocquet, L. Nanofluidics coming of age. Nat. Mater. 19, 254–256 (2020).

Aluru, N. R. et al. Fluids and electrolytes under confinement in single-digit nanopores. Chem. Rev. 123, 2737–2831 (2023).

Kavokine, N., Netz, R. R. & Bocquet, L. Fluids at the nanoscale: from continuum to subcontinuum transport. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 53, 377–410 (2021).

Mogg, L. et al. Atomically thin micas as proton-conducting membranes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 962–966 (2019).

Feng, J. et al. Single-layer MoS2 nanopores as nanopower generators. Nature 536, 197–200 (2016).

Li, F. et al. Highly efficient and selective extraction of gold by reduced graphene oxide. Nat. Commun. 13, 4472 (2022).

Cai, J. et al. Wien effect in interfacial water dissociation through proton-permeable graphene electrodes. Nat. Commun. 13, 5776 (2022).

Cheng, C., Iyengar, S. A. & Karnik, R. Molecular size-dependent subcontinuum solvent permeation and ultrafast nanofiltration across nanoporous graphene membranes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 989–995 (2021).

Razmjou, A., Asadnia, M., Hosseini, E., Habibnejad Korayem, A. & Chen, V. Design principles of ion selective nanostructured membranes for the extraction of lithium ions. Nat. Commun. 10, 5793 (2019).

Yan, G., Wang, M., Hill, G. T., Zou, S. & Liu, C. Defining the challenges of Li extraction with olivine host: the roles of competitor and spectator ions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2200751119 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Superselective removal of lead from water by two-dimensional MoS2 nanosheets and layer-stacked membranes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 12602–12611 (2020).

Zhang, H., Li, X., Hou, J., Jiang, L. & Wang, H. Angstrom-scale ion channels towards single-ion selectivity. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 2224–2254 (2022).

Zhao, Y. et al. Differentiating solutes with precise nanofiltration for next generation environmental separations: a review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 1359–1376 (2021).

Epsztein, R., DuChanois, R. M., Ritt, C. L., Noy, A. & Elimelech, M. Towards single-species selectivity of membranes with subnanometre pores. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 426–436 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Bioinspired solid-state ion nanochannels: insight from channel fabrication and ion transport. Adv. Mater. Technol. 8, 2202014 (2023).

Zarei, F. et al. Preparation of thin film composite nano-filtration membranes for brackish water softening based on the reaction between functionalized UF membranes and polyethyleneimine. J. Membr. Sci. 588, 117207 (2019).

Zhao, Y., Tong, X. & Chen, Y. Fit-for-purpose design of nanofiltration membranes for simultaneous nutrient recovery and micropollutant removal. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 3352–3361 (2021).

DuChanois, R. M., Porter, C. J., Violet, C., Verduzco, R. & Elimelech, M. Membrane materials for selective ion separations at the water–energy nexus. Adv. Mater. 33, 2101312 (2021).

Jain, T. et al. Heterogeneous sub-continuum ionic transport in statistically isolated graphene nanopores. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 1053–1057 (2015).

Sun, P. Z. et al. Exponentially selective molecular sieving through angstrom pores. Nat. Commun. 12, 7170 (2021).

Macha, M. et al. High-throughput nanopore fabrication and classification using Xe-ion irradiation and automated pore-edge analysis. ACS Nano 16, 16249–16259 (2022).

Thiruraman, J. P., Masih Das, P. & Drndić, M. Irradiation of transition metal dichalcogenides using a focused ion beam: controlled single-atom defect creation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1904668 (2019).

Thiruraman, J. P. et al. Angstrom-size defect creation and ionic transport through pores in single-layer MoS2. Nano Lett. 18, 1651–1659 (2018).

Surwade, S. P. et al. Water desalination using nanoporous single-layer graphene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 459–464 (2015).

Koenig, S. P., Wang, L., Pellegrino, J. & Bunch, J. S. Selective molecular sieving through porous graphene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 728–732 (2012).

Griffin, E. et al. Proton and Li-ion permeation through graphene with eight-atom-ring defects. ACS Nano 14, 7280–7286 (2020).

Kidambi, P. R. et al. Facile fabrication of large-area atomically thin membranes by direct synthesis of graphene with nanoscale porosity. Adv. Mater. 30, 1804977 (2018).

Marion, S., Macha, M., Davis, S. J., Chernev, A. & Radenovic, A. Wetting of nanopores probed with pressure. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 23, 4975–4987 (2021).

Cantley, L. et al. Voltage gated inter-cation selective ion channels from graphene nanopores. Nanoscale 11, 9856–9861 (2019).

Rollings, R. C., Kuan, A. T. & Golovchenko, J. A. Ion selectivity of graphene nanopores. Nat. Commun. 7, 11408 (2016).

Su, S. et al. Multifunctional graphene heterogeneous nanochannel with voltage-tunable ion selectivity. Nat. Commun. 13, 4894 (2022).

Feng, J. et al. Observation of ionic Coulomb blockade in nanopores. Nat. Mater. 15, 850–855 (2016).

Fu, Y. et al. Dehydration-determined ion selectivity of graphene subnanopores. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 24281–24288 (2020).

Sahu, S., Di Ventra, M. & Zwolak, M. Dehydration as a universal mechanism for ion selectivity in graphene and other atomically thin pores. Nano Lett. 17, 4719–4724 (2017).

Velický, M. Electrolyte versus dielectric gating of two-dimensional materials. J. Phys. Chem. C. 125, 21803–21809 (2021).

Feng, J. et al. Electrochemical reaction in single layer MoS2: nanopores opened atom by atom. Nano Lett. 15, 3431–3438 (2015).

Kuan, A. T., Lu, B., Xie, P., Szalay, T. & Golovchenko, J. A. Electrical pulse fabrication of graphene nanopores in electrolyte solution. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 203109 (2015).

Kwok, H., Briggs, K. & Tabard-Cossa, V. Nanopore fabrication by controlled dielectric breakdown. PloS one 9, e92880 (2014).

Wang, Y. et al. Fabrication of multiple nanopores in a SiNx membrane via controlled breakdown. Sci. Rep. 8, 1234 (2018).

Yanagi, I., Ishida, T., Fujisaki, K. & Takeda, K. Fabrication of 3-nm-thick Si3N4 membranes for solid-state nanopores using the poly-Si sacrificial layer process. Sci. Rep. 5, 14656 (2015).

Feng, J. et al. Identification of single nucleotides in MoS2 nanopores. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 1070–1076 (2015).

He, Y. et al. Engineering grain boundaries at the 2D limit for the hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 11, 57 (2020).

Ouyang, Y. et al. Activating inert basal planes of MoS2 for hydrogen evolution reaction through the formation of different intrinsic defects. Chem. Mater. 28, 4390–4396 (2016).

Kong, D. et al. Synthesis of MoS2 and MoSe2 films with vertically aligned layers. Nano Lett. 13, 1341–1347 (2013).

Jung, Y. et al. Metal seed layer thickness-induced transition from vertical to horizontal growth of MoS2 and WS2. Nano Lett. 14, 6842–6849 (2014).

Stern, C. et al. growth mechanisms and electronic properties of vertically aligned MoS2. Sci. Rep. 8, 16480 (2018).

Qiu, H. et al. Hopping transport through defect-induced localized states in molybdenum disulphide. Nat. Commun. 4, 2642 (2013).

Hu, S. et al. Proton transport through one-atom-thick crystals. Nature 516, 227–230 (2014).

de Souza, J. P., Chow, C.-M., Karnik, R. & Bazant, M. Z. Nonlinear ion transport mediated by induced charge in ultrathin nanoporous membranes. Phys. Rev. E 104, 044802 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Layer-by-layer thinning of MoS2 by plasma. ACS Nano 7, 4202–4209 (2013).

Qiu, X. et al. Selective separation of similarly sized proteins with tunable nanoporous block copolymer membranes. ACS Nano 7, 768–776 (2013).

Goutham, S. et al. Beyond steric selectivity of ions using ångström-scale capillaries. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 596–601 (2023).

Storey, B. D. & Bazant, M. Z. Effects of electrostatic correlations on electrokinetic phenomena. Phys. Rev. E 86, 056303 (2012).

Marcus, Y. Ionic radii in aqueous solutions. Chem. Rev. 88, 1475–1498 (1988).

YiHeng, L., YanZi, Y., JianHao, Q., HengAn, W. & FengChao, W. Anomalous ion transport through angstrom-scale pores: Effect of hydration shell exchange on ion mobility. Applied Surface Science. 560, 150022 (2021).

Li, Z. et al. Breakdown of the Nernst–Einstein relation in carbon nanotube porins. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 177–183 (2023).

Thiruraman, J. P., Masih Das, P. & Drndić, M. Stochastic ionic transport in single atomic zero-dimensional pores. ACS Nano 14, 11831–11845 (2020).

Gadaleta, A. et al. Sub-additive ionic transport across arrays of solid-state nanopores. Phys. Fluids 26, 012005 (2014).

Kavokine, N., Marbach, S., Siria, A. & Bocquet, L. Ionic coulomb blockade as a fractional Wien effect. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 573–578 (2019).

Castellanos-Gomez, A. et al. Deterministic transfer of two-dimensional materials by all-dry viscoelastic stamping. 2D Mater. 1, 011002 (2014).

Graf, M. et al. Fabrication and practical applications of molybdenum disulfide nanopores. Nat. Protoc. 14, 1130–1168 (2019).

Martínez, L., Andrade, R., Birgin, E. G. & Martínez, J. M. PACKMOL: A package for building initial configurations for molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 2157–2164 (2009).

Kohlmeyer, A. & Vermaas, J. TopoTools: Release 1.9. https://zenodo.org/records/7071898 (2022).

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

Michaud-Agrawal, N., Denning, E. J., Woolf, T. B. & Beckstein, O. MDAnalysis: A toolkit for the analysis of molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput.Chem. 32, 2319–2327 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank Adarsh Suresh and Dongchen Ying for discussion about experiments, Joan Manuel Montes De Oca for his valued insight into the MD simulations, and the AMEWS team for valued input. This work is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under award DE-SC0023317 (CL). The MD simulations were supported by the Advanced Materials for Energy-Water Systems (AMEWS) Center, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the US Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Basic Energy Sciences (CL). E. Hoenig thanks the support, through the Graduate Student Fellowship, of the University of Chicago Materials Research Science and Engineering Center, which is funded by the National Science Foundation under award number DMR-2011854. This work made use of instruments in the Materials Research Science and Engineering Center under award number DMR-2011854 at the University of Chicago; the Pritzker Nanofabrication Facility of the Pritzker School for Molecular Engineering at the University of Chicago, which receives support from Soft and Hybrid Nanotechnology Experimental (SHyNE) Resource (NSF ECCS-2025633), a node of the National Science Foundation’s National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure (RRID: SCR_022955); the Advanced Electron Microscopy Core Facility (RRID:SCR_019198) at the University of Chicago; and the Electron Microscopy Core, Research Resources Center at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.H and C.L designed the project. E.H. designed and built electrochemical instrumentation, fabricated devices, and performed material and electrochemical characterization. E.H. designed and carried out simulations and performed data analysis. E.H. and Y.H. carried out the STEM and TEM measurements. M.W., E.H. and C.L. interpreted data. K.X. and J.L. performed measurements for revisions. E.H. wrote the manuscript, with all the authors’ input. C.L. supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks James Yates and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information is available, which includes material characterization, additional electrochemical data, calculations of key parameters, and details of MD and finite element simulations.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hoenig, E., Han, Y., Xu, K. et al. In situ generation of (sub) nanometer pores in MoS2 membranes for ion-selective transport. Nat Commun 15, 7911 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52109-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52109-8

This article is cited by

-

Tuneable ion selectivity in vermiculite membranes intercalated with unexchangeable ions

Nature Communications (2025)