Abstract

Strained cycloalkynes are valuable building blocks in synthetic chemistry due to their high degree of reactivity and ability to form structurally complex scaffolds, common features of many pharmaceuticals and natural products. Alkylidene carbenes provide a pathway to the formation of strained cycloalkynes through Fritsch–Buttenberg–Wiechell rearrangements, but this strategy, like other methods of alkyne generation, is believed to depend upon a thermodynamic equilibrium that favors the alkyne over the carbene. Herein three highly strained, polycyclic alkynes, previously thought to be thermodynamically inaccessible, are generated under mild conditions and intercepted through Diels–Alder cycloaddition with a diene trapping agent. The use of a different trapping agent also allows for the interception of the alkylidene carbene, providing the first instance in which both an exocyclic alkylidene carbene and its cycloalkyne Fritsch–Buttenberg–Wiechell rearrangement product have been trapped.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Strained cyclic alkynes are of both theoretical and practical interest in organic chemistry. Incorporation of alkynes into constricted ring structures forces deviation from their ideal linear geometry, allowing chemists to probe the limits of distortion of these chemical bonds. The reactivity associated with the strain of cyclic alkynes has also been a subject of growing synthetic interest, and has been utilized for the generation of a number of complex molecular scaffolds1,2. Highly strained cycloalkynes are unstable, transient species, however, making their generation and study difficult under normal laboratory conditions3.

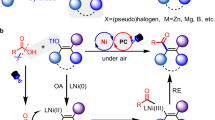

Alkylidene carbenes 1 undergo 1,2-shifts, known as Fritsch–Buttenberg–Wiechell (FBW) rearrangements, to yield alkynes 2 (Fig. 1A)4,5,6. In the case of exocyclic alkylidene carbenes 3, FBW rearrangements can provide access to highly reactive, geometrically strained cyclic alkynes 4 that are difficult to generate through other means (Fig. 1B)7,8. FBW rearrangements of alkylidene carbenes have been used for the generation of monocyclic alkynes9,10 such as cyclopentynes11,12,13 and cyclohexynes13,14,15, as well as a number of polycyclic alkynes16,17,18. Many of these strained alkynes are transient, non-isolable species under ambient temperature, and their formation is inferred through their reaction with various trapping agents3,12.

A Fritsch–Buttenberg–Wiechell (FBW) rearrangement of acyclic and exocyclic alkylidene carbenes 1 and 3, respectively. B Polycyclic alkylidene carbenes for which FBW rearrangements are thermodynamically unfavorable. The relative thermodynamic stabilities of 5 and 619 and 7 and 820 have been reported previously, and are in agreement with computational experiments conducted herein (See Supplementary Fig. 1).

The generation of alkynes via FBW rearrangements of alkylidene carbenes is generally considered to depend upon a thermodynamic equilibrium that favors the target alkyne over the corresponding carbene19,20,21,22,23. While this is the case for most monocyclic alkynes10,11,16, with the exceptions of cyclobutyne20 and cycloheptyne9,24, the additional geometric constriction present in many polycyclic alkynes can potentially tip equilibrium in favor of the carbene. In such cases, even direct synthesis of the strained alkyne will result in rearrangement to the alkylidene carbene through the reverse 1,2-shift, known as the Roger Brown rearrangement20,25,26. Attempts to detect a number of polycyclic alkynes, including 5 and 7, through the FBW rearrangement of their respective alkylidene carbenes have been unsuccessful, purportedly due to unfavorable differences in the relative stabilities of the two chemical species (Fig. 1B)19,21,22,23.

A number of experimental factors affect the successful detection of a cycloalkyne that is in equilibrium with an alkylidene carbene, factors that can confound subsequent interpretations of the relative thermodynamic stabilities of these intermediates. Preparation of alkylidene carbenes for the generation of polycyclic alkynes has primarily involved the deprotonation of bromoethylenecycloalkanes16,17,18,27, or the lithiation of dibromomethylenecycloalkanes19,21,22,23,24, both of which initially generate an alkylidenecarbenoid species. Alkylidenecarbenoids exhibit different patterns of reactivity compared to free alkylidene carbenes28, and can react through unique pathways4 that involve dimerization29, decomposition30,31,32, and FBW rearrangements33,34,35. This potential for alternative pathways of reactivity makes the use of alkylidenecarbenoids problematic for the study of carbene–alkyne equilibria.

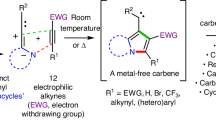

Reaction temperature will also influence the degree to which the carbene–alkyne equilibrium is established. Typical preparations of alkylidene carbenes require either high temperatures in the case of deprotonation of bromoethylenecycloalkenes16,17,18,27, or low temperatures in the case of lithiation of dibromomethylenecycloalkanes19,21,22,23,24. Whereas trapping experiments utilizing high-temperature reactions have typically been successful in detecting the alkyne16,17,18,27, a number of attempts under low temperature conditions have been unsuccessful19,21. This outcome has generally been attributed to thermodynamic favorability of the carbene over the alkyne, but low temperatures may also place the reaction outcome under kinetic control, thereby favoring trapping of the carbene before thermodynamic equilibrium is established between the carbene and alkyne (Fig. 2A).

A Low temperatures may prevent establishment of equilibrium between alkylidene carbene and cycloalkyne, resulting in trapping of the alkylidene carbene. B If the absolute activation energy for trapping of the alkylidene carbene is lower than that for the alkyne, the carbene will be trapped regardless of the thermodynamic relationship of the two intermediates.

An alkyne that is thermodynamically favored over its corresponding carbene can still evade detection, even after establishment of equilibrium, depending on the particular trapping agent in use. The reaction of a carbene or alkyne with a trapping agent may follow a Curtin–Hammett scenario36, in which the distribution of products is determined not by the thermodynamic stability of the intermediates, but by the relative activation free energies for the trapping of these intermediates. If the absolute activation free energies to reaction between carbene and trap is lower than that between alkyne and trap, the carbene will be preferentially selected regardless of the relative thermodynamic stabilities of the two intermediates (Fig. 2B).

Our laboratory has a developed a photolytic approach to the generation of free alkylidene carbenes that proceeds under mild conditions and ambient temperatures13,14,37,38,39. Herein, we demonstrate the utility of this method toward the generation of highly strained polycyclic alkynes bicyclo[2.2.2]oct-2-yne (10), pentacyclo[5.5.0.04,11.05,9.08,12]dodec-2-yne (13), and pentacyclo [6.4.0.03,7.04,12.06,11]dodec-9-yne (6) via the FBW rearrangement of their respective alkylidene carbenes 9, 12, and 5 (Fig. 3). All three alkynes have previously been determined to be inaccessible due to unfavorable thermodynamic relationships with their corresponding carbenes19,21,23. The choice of trapping agent was found to have a decisive effect on reaction outcome, allowing for either carbene or alkyne to be intercepted, which could be predicted through computational experiments.

The results herein demonstrate that trapping experiments are an inadequate method for the elucidation of thermodynamic relationships between intermediates, and that the nature of these relationships is not a limitation to the trapping of unstable intermediates. The use of photolysis moreover allows for the generation of free carbenes under mild conditions that avoid alternative reaction pathways characteristic of alkylidenecarbenoids4, and enables trapping with a variety of reaction partners. To our knowledge, this is the first report in which both an exocyclic alkylidene carbene and its cycloalkyne FBW rearrangement product have been successfully trapped.

Results and discussion

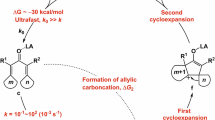

Synthesis of alkylidene carbene precursors

Our investigation into the generation of strained alkynes via FBW rearrangement of their corresponding alkylidene carbenes was prompted by calculations at the DLPNO-CCSD(T)/CPCM(benzene)/def2-TZVPP//M06/CPCM(benzene)/def2-TZVP40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47 level of theory, which predicted bicyclo[2.2.2]oct-2-yne (10) to be lower in energy than 7-norbornylidene carbene (9) by 1.0 kcal/mol (Fig. 4). The activation energy of the rearrangement was predicted to be 8.4 kcal/mol, an activation energy that is comparable to those predicted for previously investigated alkylidene carbenes that undergo FBW rearrangement15. Pentacyclo[5.5.0.04,11.05,9.08,12]dodec-2-yne (13) was also predicted to be more stable than 8-pentacyclo[5.4.0.02,6.03,10.05,9]undecylidene carbene (12) by 2.4 kcal/mol (Fig. 4). The presence of the triple bonds in compounds 10 and 13 is predicted to inflict 51.0 kcal/mol and 41.3 kcal/mol of strain energy, respectively (See Supplementary Fig. 2)48. Both polycyclic alkynes have previously been determined to be less thermodynamically stable than their corresponding alkylidene carbenes 9 and 12 based on trapping experiments, using norbornadiene in the case of 921, and cyclohexene in the case of 1219.

Potential energy surface for the FBW rearrangement of 7-norbornylidene carbene (9) to bicyclo[2.2.2]oct-2-yne (10) and 8-pentacyclo[5.4.0.02,6.03,10.05,9]undecylidene carbene (12) to pentacyclo[5.5.0.04,11.05,9.08,12]dodec-2-yne (13), computed at DLPNO-CCSD(T)/CPCM(benzene)/ def2-TZVPP//M06/CPCM(benzene)/def2-TZVP. See Supplementary Data 1 for the cartesian coordinates of the optimized structures.

Precursor 22, from which 7-norbornylidene carbene (9) can be photochemically generated, was synthesized from 7-norbornanone (21)49,50,51 and dichlorocyclopropyl phenanthrene derivative 2352 by adapting a procedure previously reported by Takeda et al.53 (Fig. 5). The synthesis of 7-norbornanone (21) was achieved in four steps starting from norbornadiene (17) following previously reported procedures49,50,51. Precursor 29 was synthesized using 8-pentacyclo[5.4.0.02,6.03,10.05,9]undecan-8-one (28), made from 8-pentacyclo[5.4.0.02,6.03,10.05,9] undecan-8,11-dione (24) in four steps, and 23.

Yields reported represent isolated yields. Reagents and conditions: i) TBPB, CuBr, benzene, reflux, ii) Pd(OAc)2/C, H2, MeOH, iii) TMS-I, CHCl3, NaHCO3, MeOH, iv) PCC, CH2Cl2, v) 23, Cp2TiCl2, Mg, P(OEt)3, 4 Å mol. sieves, THF, RT vi) ethylene glycol, pTsOH, benzene vii) LiAlH4, Et2O, reflux, HCl, H2O, viii) NH2NH2 • H2O, diethylene glycol, Δ, KOH, reflux, ix) CrO3, H2O, AcOH, Δ. aMixture of exo and endo diastereomers.

Trapping studies

The strained alkyne bicyclo[2.2.2]oct-2-yne (10) was successfully generated following irradiation of precursor 22 in benzene (280–400 nm, 6 h) and intercepted with cyclopentadienone 16 as the trapping agent (Fig. 6). Photolysis of 22 is expected to initially extrude 7-norbornylidene carbene (9) with the concomitant release of phenanthrene (30, Fig. 6)14,15,54. Subsequent FBW rearrangement of 9 generates bicyclo[2.2.2]oct-2-yne (10), which can then undergo a Diels–Alder cycloaddition with diene 16, yielding the adduct 33. Loss of carbon monoxide from 33 leads to the observed product 11, the structure of which was confirmed by X-ray crystallography (Fig. 6). Compound 32, which likely arises from a 1,5-alkyl shift within precursor 22 followed by electrocyclic ring opening, was also identified as a major product of the photolysis reaction. Similar isomerization reactions have previously been reported in the photochemical generation of carbenes55,56,57. A small amount of allene 31 was also detected, the product of dimerization of alkylidene carbene 9 (Fig. 6). Using the yield of phenanthrene in the unpurified reaction mixture as an indication of the amount of carbene released in the photolysis reaction, approximately 86% of the carbene 11 released from precursor 22 was trapped as alkyne 10 to yield 11.

Photolysis of precursor 22 in the presence of diene 16 resulted in the formation of adduct 11, the expected product of reaction between bicyclo[2.2.2]oct-2-yne (10) and 16. Photolysis of precursor 29 in the presence of 16 resulted in the formation of adduct 14, indicating the reaction of pentacyclo[5.5.0.04,11.05,9.08,12]dodec-2-yne (13) and 16. aIsolated yield. bYield determined by NMR spectroscopy of the unpurified reaction mixture. cMixture of two diastereomers. dIdentity determined by GC/MS analysis of the unpurified reaction mixture.

Photolysis of precursor 29 (280–400 nm, 10 h) proceeded to yield the Diels–Alder adduct 14 as the major product, in addition to a complex mixture of other minor products (Fig. 6). 1H NMR spectroscopy of the unpurified reaction mixture indicated that phenanthrene was released, and likewise 8-pentacyclo[5.4.0.02,6.03,10.05,9]undecylidene carbene (12) was generated, in 61% yield. The remaining precursor likely underwent isomerization to 34, similarly to the photolysis of precursor 22. Although adduct 14 accounts for only 18% of the alkylidene carbene generated, there are no other major products of reaction with diene 16. The peaks corresponding to the methyl ester protons of unreacted diene 16 and adduct 14 are the largest signals within the 3.0–4.0 ppm range in the 1H NMR spectrum of the unpurified reaction mixture, indicating that 14 is the major product of reaction with diene 16 (See Supplementary Fig. 3). A number of much smaller peaks are evident within the 3.0–4.0 ppm range, indicating that much of the diene that is consumed, either in reaction with carbene 12 or alkyne 13, reacts to form a multitude of different products in minor amounts.

The use of cyclopentadienone 16 as a trapping agent was expected to preferentially detect alkynes 10 and 13, which can undergo Diels–Alder cycloaddition, over carbenes 9 and 12, which can only undergo a [1 + 2] cyclopropanation reaction. Irradiation of precursors 22 and 29 in the presence of cyclohexene (35, 280–400 nm, 6 h), which is expected to be capable of trapping both carbene and alkyne11,19,23, yielded the cyclopropanation products 36 and 39 exclusively (Fig. 7). The identities of 36 and 39 were determined by derivatization to spirocyclopropanes 37 and 40, respectively, and subsequent characterization by X-ray crystallography (Fig. 7). Photolysis of 22 yielded 36 selectively both when the reagents were diluted in benzene (0.1 M or 0.01 M), or when cyclohexene (35) was used as solvent, indicating that bicyclo[2.2.2]oct-2-yne (10) could not be intercepted with cyclohexene regardless of the concentration of this trapping agent. Together, the data indicate that the outcome of the trapping experiments are primarily dependent on the identity of the trapping agent, rather than the thermodynamic relationship between the alkyne and alkylidene carbene.

Photolysis of precursor 22 in the presence of cyclohexene (35) resulted in the formation of adduct 36, the expected product of reaction between 7-norbornylidene carbene (9) and 35. Photolysis of precursor 29 in the presence of 35 resulted in the formation of 39, indicating the reaction of 8-pentacyclo[5.4.0.02,6.03,10.05,9]undecylidene carbene (12) and 35. The identities of adducts 36 and 39 were determined by derivatization to spirocyclopropanes 37 and 40, respectively, and characterization by X-ray crystallography.

Computational Studies

The differences in product specificity when cyclopentadienone 16 or cyclohexene 35 are used as trapping agents are consistent with calculations at the DLPNO-CCSD(T)/CPCM(benzene)/def2-TZVPP//M06/CPCM(benzene)/def2-TZVP40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47 level of theory (Fig. 8). [Comparable results were obtained using DLPNO-CCSD(T)/CPCM(benzene)/def2-TZVPP//M06-2X/CPCM(benzene)/def2-TZVP model chemistry. See Supplementary Fig. 7] Upon generation of 7-norbornylidene carbene (9), at least three pathways of reactivity are possible: dimerization, addition to the trapping agent, or FBW rearrangement. Dimerization, a pathway generally associated with carbenoids4,21, has also been observed following the photochemical generation of free 2-adamantylidenecarbene57. In the case of 7-norbornylidene carbene (9), dimerization to triene 31 is predicted to be an energetically barrierless process (Fig. 8), similar to the dimerization of methylenecarbene58,59,60. Dimer 31 was the only product detected besides the isomerization product 32 following photolysis of precursor 22 in the absence of trapping agent (See Supplementary Fig. 4), indicating that this pathway is largely outcompeted by trapping when diene 16 or cyclohexene (35) is present.

A In the presence of cyclopentadiene 16. B In the presence of cyclohexene (35). See Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6 for a comprehensive analysis of the addition of cyclohexene (35) to bicyclo[2.2.2]oct-2-yne (10). Computed at DLPNO-CCSD(T)/CPCM(benzene)/ def2-TZVPP//M06/CPCM(benzene)/def2-TZVP. See Supplementary Data 1 for the cartesian coordinates of the optimized structures.

With the use of diene 16 as a trapping agent, the activation energy for the FBW rearrangement of 7-norbornylidene carbene (9) to bicyclo[2.2.2]oct-2-yne (10) is predicted to be lower than that for trapping of the carbene 9 to form cyclopropylidene 42 (Fig. 8A). The first-order, intramolecular FBW rearrangement of 7-norbornylidene carbene (9) also largely outcompetes the second-order, intermolecular dimerization reaction, as evidenced by the minimal amount of dimer product in the reaction mixture (Fig. 6)61. Bicyclo[2.2.2]oct-2-yne (10) exhibits a lower absolute and relative activation free energy to trapping with diene 16 compared to that of 9, and would thereby be favored in the trapping experiment, resulting in formation of adduct 33, then adduct 11 via decarbonylation.

Generation of 7-norbornylidene carbene (9) in the presence of cyclohexene (35) results in trapping of 9 due to a prohibitively high activation free energy of reaction for the addition of cyclohexene to bicyclo[2.2.2]oct-2-yne (10, Fig. 8B). The FBW rearrangement of carbene 9 to alkyne 10 may be expected to outcompete the addition of 9 to cyclohexene (35) due to a lower activation free energy and a lesser dependence on the concentration of reactants. The strained alkyne 10 faces a substantially larger activation free energy to trapping, however, compared to that of alkylidene carbene 9 (18.9 kcal/mol vs 11.1 kcal/mol). Computational experiments indicate that bicyclo[2.2.2]oct-2-yne (10) does not exhibit a substantial amount of biradical character, and predict similar activation energies for the addition of 10 to cyclohexene via dicarbene and biradical intermediates (See Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 6). Previous investigations into the reactivity of other strained alkynes indicate that cycloaddition reactions typically occur through a dicarbene pathway62,63,64,65. Due to the high activation free energy for reaction between cyclohexene (35) and alkyne 10, and a substantially lower activation energy for the rearrangement of alkyne 10 back to carbene 9 (9.4 vs 18.9 kcal/mol), trapping of 7-norbornylidene carbene (9) will be favored despite its lower concentration at equilibrium. The cyclobutylated product 38, and likewise the presence of bicyclo[2.2.2]oct-2-yne (10), will thus not be detected under these experimental conditions, regardless of the relative thermodynamic stabilities of the two intermediates (Fig. 8B).

Computational experiments indicate that the complex mixture of products observed following generation of 8-pentacyclo[5.4.0.02,6.03,10.05,9]undecylidene carbene (12) is likely due to a relatively high activation free energy for FBW rearrangement (Fig. 9). The activation energies for trapping of carbene 12 and alkyne 13 with diene 16 (10.6 and 6.6 kcal/mol, Fig. 9A) are comparable to those of 7-norbornylidene carbene (9) and bicyclo[2.2.2]oct-2-yne (10, 11.0 and 6.7 kcal/mol, Fig. 8A). Despite these similar activation energies for trapping, the yield of adduct 11 following the photolysis of 22 is significantly higher than that of adduct 14 following the photolysis of 29 (50% and 11%, Fig. 6). This discrepancy in the yields of adducts 11 and 14 may be attributable to a larger activation energy for FBW rearrangement of undecylidene carbene 12 than for that of 7-norbornylidene carbene (9, 10.1 kcal/mol and 8.4 kcal/mol, Fig. 8A and Fig. 9A). The relatively slow rate of both rearrangement and trapping of undecylidene carbene 12 likely leaves this intermediate more susceptible to alternative pathways of reactivity and decomposition, as is indicated by the 1H NMR spectrum of the unpurified reaction mixture (See Supplementary Fig. 3).

A In the presence of diene 16. B In the presence of cyclohexene (35). See Supplementary Fig. 8 for a comprehensive analysis of the addition of diene 16 to alkylidene carbene 11 and alkyne 13, and Supplementary Fig. 9–13 for the addition of cyclohexene (35) to alkylidene carbene 11 and alkyne 13. Computed at DLPNO-CCSD(T)/CPCM(benzene)/def2-TZVPP//M06/CPCM(benzene)/def2-TZVP. See Supplementary Data 1 for the cartesian coordinates of the optimized structures.

Generation of undecylidene carbene 12 in the presence of cyclohexene (35) results in a Curtin–Hammett scenario in which trapping of the carbene is favored over that of the alkyne (Fig. 9B). While equilibration of undecylidene carbene 12 and pentacyclo[5.5.0.04,11.05,9.08,12]dodec-2-yne (13) via FBW rearrangement is expected to result in a substantially higher concentration of alkyne 13, the free activation energy for reaction of 13 with cyclohexene is prohibitively high (23.3 kcal/mol). Thus, cyclohexene will react with carbene 12 selectively, driving the rearrangement of alkyne 13 back to carbene 12. Similarly to alkyne 10, the addition of pentacyclo[5.5.0.04,11.05,9.08,12]dodec-2-yne (13) to cyclohexene (35) is predicted to proceed through a dicarbene, rather than biradical, intermediate (See Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13).

Alkynes that are less thermodynamically stable than their corresponding alkylidene carbenes can also be trapped with the use of an appropriate reaction partner. Calculations at the DLPNO-CCSD(T)/CPCM(benzene)/def2-TZVPP//M06/CPCM(benzene)/def2-TZVP40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47 level of theory predict pentacyclo[6.4.0.03,7.04,12.06,11]dodec-9-yne (6) to be less stable than 2-pentacyclo[6.3.0.03,7.04,11.06,10]undecylidene carbene (5) by 4.5 kcal/mol, with a free activation energy of rearrangement of 12.3 kcal/mol (Fig. 10A). The presence of the triple bond is moreover predicted to incur 52.1 kcal/mol of strain energy to alkyne 6 (See Supplementary Fig. 2). Nevertheless, the intramolecular rearrangement of alkylidene carbene 5 to alkyne 6 may potentially outcompete the intermolecular trapping of the carbene, processes which have similar activation energies (10.5 and 12.3 kcal/mol, Fig. 10A). Once alkyne 6 is formed, its reaction with diene 16 becomes the energetically favorable pathway. Precursor 50 was therefore synthesized, using methods similar to those employed for the synthesis of 22 and 29 (See Synthetic Procedures), with the aim of trapping pentacyclo[6.4.0.03,7.04,12.06,11]dodec-9-yne (6).

A Potential energy surface for the reactions of 2-pentacyclo[6.3.0.03,7.04,11.06,10]undecylidene carbene (5) and pentacyclo[6.4.0.03,7.04,12.06,11]dodec-9-yne (6) with diene 16, computed at DLPNO-CCSD(T)/CPCM(benzene)/def2-TZVPP//M06/CPCM(benzene)/def2-TZVP. See Supplementary Data 1 for the cartesian coordinates of the optimized structures. B Photolysis of precursor 50 in the presence of diene 16 resulted in the formation of adduct 15, the expected product of reaction between 6 and 16.

Despite the large free activation energy for the formation of pentacyclo[6.4.0.03,7.04,12.06,11]dodec-9-yne (6), and an equilibrium that predicts 6 to exist at a concentration less than 0.05% that of undecylidene carbene 5, the cycloalkyne 6 was successfully trapped with diene 16 following the photolysis of precursor 50 (Fig. 10B). Based on the yields of phenanthrene (30) and rearrangement product 51, 18% of the undecylidene carbene 5 generated during photolysis was trapped as cycloalkyne 6 via reaction with diene 16. The yield of Diels–Alder adduct 15 is comparable to that of 14 following the photolysis of 29 (Fig. 6), despite the different thermodynamic relationships between alkylidene carbene and alkyne within the two reactions (Fig. 9A, Fig. 10A). The comparable yields of 14 and 15 indicate that the activation energies for FBW rearrangement, which are similarly high for undecylidene carbenes 12 and 5, may be a large determinant of yield in these reactions.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the photochemical generation of exocyclic alkylidene carbenes provides a useful strategy for generating highly strained caged alkynes, and have employed this method for the generation of bicyclo[2.2.2]oct-2-yne (10), pentacyclo[5.5.0.04,11.05,9.08,12]dodec-2-yne (13), and pentacyclo[6.4.0.03,7.04,12.06,11]dodec-9-yne (6) all of which were previously considered to be thermodynamically inaccessible21. While computational experiments predicted 10 and 13 to be more stable than their corresponding alkylidene carbenes, 6 is expected to be less stable than undecylidene carbene 5. Alkyne 6 can still be trapped, however, with an appropriate reaction partner. The results herein demonstrate that the use of chemical trapping experiments for the investigation of alkyne–carbene equilibria in FBW rearrangements is a problematic approach. The results of trapping experiments reflect the differences in the absolute free activation energies for the trapping of the two intermediates, in addition to the activation energies of FBW rearrangement, rather than the thermodynamic relationships of the intermediates themselves. With the use of different trapping agents, alkylidene carbenes 9 and 12 as well as their corresponding cycloalkynes 10 and 13 could all be intercepted in the present work. The relative stabilities of the alkylidene carbene and alkyne is less consequential, in regards both to their trapping and their potential synthetic utility, than the reactive partner used and the activation energy for FBW rearrangement.

Methods

General notes

Tetrahydrofuran was degassed by purging with nitrogen, and dried by passage through two activated alumina columns (2 ft × 4 in). Other solvents and reagents were used as obtained from commercial sources. Medium-pressure flash chromatography was performed on an automated system using prepacked silica gel columns (70−230 mesh), or by hand using Sorbtech silica gel 60 A (35 × 70 mesh) with the indicated eluents. AgNO3-treated silica gel was prepared as follows: To a solution of AgNO3 (12.0 g) in acetonitrile (100 mL) was added silica gel (40 g). The mixture was stirred, and the resulting slurry was heated at 80 °C in vacuo on a rotary evaporator for 2 h, then allowed to cool to room temperature and stored in a foil-covered flask. Proton (1H) and proton-decoupled carbon 13C{1H} NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 and C6D6 at 500 and 126 MHz, respectively. The data are reported as follows: chemical shift in ppm referenced to residual solvent (1H NMR: CDCl3 δ 7.26; 13C NMR: CDCl3 δ 77.2, multiplicity, coupling constants (Hz), and integration. Structures were determined using COSY, HSQC, and HMBC experiments. Overlapping carbon peaks were identified using HSQC experiments and the integration of 13C NMR spectra. Product yields in unpurified reaction mixtures were determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy using 1,3-benzodioxole and p-xylene as internal standards. High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) data were obtained on an Agilent 6230 TOF Mass Spectrometer. Infrared spectra (resolution 4.0 cm−1) were acquired on solid samples with an FTIR instrument equipped with an attenuated total reflectance (ATR) accessory. Photolysis experiments were conducted with a Newport 200 W Xe-Hg arc lamp (model # 6290; horizontal intensity 600 cd) with a Newport 280–400 dichroic mirror (model # 66245) fitted in a Newport 67005 Housing with a Newport 69907 Universal Arc Lamp Power Supply. All photolysis reactions were conducted in quartz glassware positioned 30 cm away from the light source. All reactions were performed under an atmosphere of argon in glassware that had been dried in an oven at 120 °C unless otherwise stated.

Synthetic procedures

7-tert-butoxynorbornadiene (18)

Following the procedure of Kozel et al.50, to a refluxing mixture of norbornadiene (17, 45.3 g, 492 mmol) and cuprous bromide (0.109 g, 0.756 mmol) in benzene (150 mL) under argon atmosphere was added a solution of tert-butylperoxybenzoate (36.0 mL, 189 mmol) in benzene (30 mL) over 20 min. The reaction mixture was stirred an additional 30 min, then cooled to room temperature and washed with 10% aqueous sodium carbonate (3 × 100 mL), followed by H2O (2 ×100 mL). The organic phase was then dried (Na2SO4), and the benzene was removed in vacuo. Distillation under reduced pressure afforded 7-tert-butoxynorbornadiene (18) as a colorless oil (10.5 g, 34%). The spectroscopic data are in agreement with those previously reported66: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.54 (t, J = 2.2 Hz, 2H), 6.49 (t, J = 2.2 Hz, 2H), 6.50–6.48 (m, 2H), 3.68 (s, 1H), 3.32–3.28 (m, 2H), 1.04 (s, 9H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 139.9, 137.4, 104.4, 73.7, 55.6, 28.4. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M• – t-Bu]+ Calcd for C11H16O 107.0497; Found 107.0499.

7-(tert-butoxy)bicyclo[2.2.1]heptane (19)

Following the procedure of Felpin and Fouquet49, to a stirring solution of 7-tert-butoxynorbornadiene (18, 9.50 g, 58.0 mmol) in methanol (75 mL) was added a mixture of palladium acetate (0.013 g, 0.058 mmol) and charcoal (0.117 g). The reaction mixture was flushed with hydrogen gas, then stirred under an atmosphere of hydrogen until diene 18 was fully consumed, as determined by GC-MS. The reaction mixture was then filtered through a plug of Celite, and the solvent was removed in vacuo. Purification by flash column chromatography (3:97 Et2O:pentane) afforded 7-(tert-butoxy)bicyclo[2.2.1]heptane (19) as a colorless oil (4.09 g, 43%). The spectroscopic data are in agreement with those previously reported49: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.69 (s, 1H), 1.89–1.80 (m, 4H), 1.56–1.49 (m, 2H), 1.21–1.15 (m, 11H), 1.13–1.09 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 79.4, 72.8, 40.2, 28.6, 27.4, 26.5. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M• – t-Bu]+ Calcd for C11H20O 111.0810; Found 111.0808.

7-norbornol (20)

Following the procedure of Rosenkoetter et al.51, iodotrimethylsilane (3.7 mL, 26 mmol) was added to a solution of 7-(tert-butoxy)bicyclo[2.2.1]heptane (19, 5.2 g, 26 mmol) in chloroform (45 mL).The reaction mixture was stirred 20 min at room temperature, then poured into a slurry of sodium carbonate (7.4 g) in methanol (150 mL) and stirred an additional 10 min. The suspension was then filtered, and the filtered solid was washed with methanol (150 mL). The combined filtrates were concentrated in vacuo, then suspended in 10% aqueous sodium thiosulfate (185 mL) and stirred 1 h. The mixture was then extracted with diethyl ether (3 ×100 mL), and the combined organic phases were dried (Na2SO4), filtered, and concentrated in vacuo to afford 7-norbornol (20) as an orange waxy solid (2.20 g, 98%). The spectroscopic data are in agreement with those previously reported51: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.99 (s, 1H), 3.75–3.67 (m, 1H), 1.96–1.93 (m, 2H), 1.88–1.83 (m, 2H), 1.58–1.53 (m, 2H), 1.30–1.25 (m, 2H), 1.19–1.14 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 79.9, 40.4, 26.9, 26.7. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M• – H]+ Calcd for C7H12O 111.0810; Found 111.0810.

7-norbornone (21)

Following the procedure of Rosenkoetter et al.51, to a suspension of pyridinium chlorochromate (5.39 g, 25.0 mmol) in dichloromethane (300 mL) was added a solution of 7-norbornol (20, 1.12 g, 10.0 mmol) in dichloromethane (150 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred until 7-norbornol (20) was completely consumed, as determined by GC-MS. Diethyl ether (150 mL) was then added and the mixture was stirred 30 min, then transferred to a separatory funnel and extracted with diethyl ether (150 mL). The organic phase was washed with H2O (3 ×400 mL), dried (Na2SO4), filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. Purification by column chromatography (Et2O) yielded 7-norbornone (21) as a pale oil (0.588 g, 53%). The spectroscopic data are in agreement with those previously reported51: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.96–1.89 (m, 4H), 1.87–1.84 (m, 2H), 1.60–1.54 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 217.9, 38.1, 24.3. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M• – H]+ Calcd for C7H10O 109.0653, Found 109.0652.

Precursor 22

Following the procedure of Takeda et al.53, to a round-bottom flask charged with magnesium turnings (0.729 g, 30.0 mmol) and 4 Å molecular sieves (1.50 g) was added bis(cyclopentadienyl)titanium(IV) dichloride (7.47 g, 30.0 mmol) followed by anhydrous THF (60 mL). Triethyl phosphite (10.3 mL, 60.0 mmol) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred for 3 h, during which the color of the mixture turned from red to dark green. A solution of dichlorocyclopropyl phenanthrene 23 (2.62 g, 10.0 mmol) dissolved in THF (20 mL) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred for an additional 30 min. 7-Norbornone (21, 0.55 g, 5.0 mmol) in THF (5 mL) was then added, and the reaction mixture was stirred for an additional 16 h. Hexanes (200 mL) was added, and the resulting suspension was transferred to a plug of silica and eluted with hexanes (100 mL) followed by a solution of hexanes and ethyl acetate (10:90, 100 mL). The elution was concentrated in vacuo. Purification of the resulting residue by flash chromatography with silica gel (hexanes) followed by flash column chromatography with AgNO3-treated silica gel (30% AgNO3, 2:98→20:80 ethyl acetate:hexanes) afforded precursor 22 (0.330 g, 23%) as a white solid: mp = 130–133 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.97–7.90 (m, 2H), 7.41–7.35 (m, 2H), 7.26–7.19 (m, 4H), 3.16 (s, 2H), 2.41 (s, 2H), 1.73–1.65 (m, 2H), 1.37–1.30 (m, 2H), 1.11–0.97 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 139.2, 134.8, 129.2, 128.6, 127.7, 125.8, 123.3, 108.1, 38.4, 29.3, 28.7, 22.3. IR (ATR) 2954, 2862, 1486, 1441, 763, 730, 615 cm−1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M• – H]+ Calcd for C22H20 283.1487; Found 283.1499.

8-pentacyclo[5.4.0.02,6.03,10.05,9]undecan-8,11-dione (24)

Following the procedure of Gaidai et al.67, racemic (1R,4S,4aR,8aS)-1,4,4a,8a-tetrahydro-1,4-methanonaphthalene-5,8-dione (54, 7.05 g, 40.5 mmol) was dissolved in ethyl acetate (50 mL) in a quartz cuvette, positioned in front of a mercury-xenon lamp and irradiated for 36 h. The solvent was then removed in vacuo, and purification of the resulting solid by flash chromatography (1:1 ethyl acetate:hexanes) afforded 8-pentacyclo[5.4.0.02,6.03,10.05,9]undecan-8,11-dione (24) as white crystals (6.29 g, 89%). The spectroscopic data are in agreement with those previously reported67: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.20–3.15 (m, 2H), 2.96–2.92 (m, 2H), 2.84–2.80 (m, 2H), 2.71 (s, 2H), 2.07–2.03 (m, 1H), 1.91–1.87 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 212.3, 54.9, 44.8, 43.9, 40.6, 38.9. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + Na]+ Calcd for C11H10O2 197.0573; Found 197.0575.

Caged acetal 25

Following the procedure of Eaton et al.68, a mixture of 8-pentacyclo[5.4.0.02,6.03,10.05,9]undecan-8,11-dione (24, 10.0 g, 57.5 mmol), ethylene glycol (3.95 g, 63.6 mmol), and p-toluene sulfonic acid (0.125 g, 0.726 mmol) in benzene (50 mL) was heated under reflux (85 °C) in a heating mantle for 14 h. The reaction mixture was then cooled to room temperature and slowly poured into ice-cold 10% aqueous sodium bicarbonate (50 mL). The organic phase was separated and the aqueous phase was extracted with dichloromethane (2 ×50 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. Recrystallization of the resulting solid from ether-hexane (1:1) afforded caged acetal 25 as a white solid (11.18 g, 89%). The spectroscopic data are in agreement with those previously reported68: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.97–3.82 (m, 4H), 3.00–2.93 (m, 1H), 2.84–2.78 (m, 2H), 2.69–2.52 (m, 3H), 2.53–2.41 (m, 2H), 1.87 (d, J = 11.0 Hz, 1H), 1.58 (d, J = 11.0 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 215.4, 114.1, 65.9, 64.8, 53.2, 50.9, 46.0, 43.0, 42.5, 41.6, 41.5, 38.9, 36.5. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C13H14O3 219.1016; Found 219.1006.

Caged hydroxy-ketone 26

Following the procedure of Dekker and Oliver69, caged acetal 25 (9.00 g, 41.3 mmol) was added via solid addition funnel to a suspension of lithium aluminum hydride (0.788 g, 20.8 mmol) in dry diethyl ether (50 mL) over 10 min. The reaction mixture was heated under reflux (35 °C) for 2 h, then cooled to 0 °C in an ice bath. Saturated aqueous ammonium chloride (20 mL) was added slowly, then the organic layer was separated and concentrated in vacuo. 6% Aqueous HCl (180 mL) was added to the resulting solid, and the mixture was stirred for 2 h. The solution was then neutralized with 10% aqueous NaOH, then extracted with dichloromethane (3 ×100 mL). The combined organic phases were dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo to afford caged hydroxy-ketone 26 as a white solid (6.11 g, 84%). The spectroscopic data are in agreement with those previously reported69: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.64 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 0.5 H, HA), 4.15–4.01 (m, 0.5 H, HA), 3.82–3.68 (m, 0.5 H, HB), 3.05–2.36 (m, 8H), 2.32–2.19 (m, 0.5 H, HB), 1.89 (t, J = 12.2 Hz, 1H), 1.56 (d, J = 10.5 Hz, 0.5 H), 1.50 (d, J = 11.0 Hz, 0.5 H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 219.3, 119.4, 81.8, 72.4, 56.4, 55.1, 54.3, 50.0, 46.1, 45.4, 45.0, 44.8, 43.6, 43.4, 43.2, 42.2, 42.0, 41.8, 41.7, 40.8, 38.5, 37.0. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C11H12O2 177.0910; Found 177.0902.

8-pentacyclo[5.4.0.02,6.03,10.05,9]undecan-8-ol (27)

Following the procedure of Dekker and Oliver69, a mixture of caged hydroxy-ketone 26 (3.00 g, 17.0 mmol) and hydrazine monohydrate (4.97 mL, 102 mmol) in diethylene glycol (60 mL) was heated at 120 °C in a heating mantle for 1.5 h. Potassium hydroxide (2.34 g, 41.7 mmol) was then added and the excess hydrazine and H2O were distilled off until the temperature reached 190 °C. The reaction mixture was heated under reflux at 190 °C for 3 h and then steam distilled. Extraction of the distillate with dichloromethane afforded caged 8-pentacyclo[5.4.0.02,6.03,10.05,9]undecan-8-ol (27, 1.68 g, 61%) as a white solid. The spectroscopic data are in agreement with those previously reported69: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.96–3.91 (m, 1H), 2.76–2.70 (m, 1H), 2.65–2.59 (m, 1H), 2.58–2.52 (m, 1H), 2.46–2.38 (m, 2H), 2.31–2.19 (m, 4H), 1.72–1.67 (m, 1H), 1.44–1.41 (m, 1H), 1.19–1.14 (m, 1H), 1.08 (dt, J = 11.9, 3.9 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 74.5, 47.2, 45.9, 43.2, 42.15, 42.14, 40.0, 39.0, 36.0, 35.3, 28.9. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H – H2O]+ Calcd for C11H14O 145.1017; found 145.1015.

8-pentacyclo[5.4.0.02,6.03,10.05,9]undecan-8-one (28)

Following the procedure of Dekker and Oliver69, chromium trioxide (1.60 g, 16.0 mmol) in H2O (2.4 mL) was added to caged alcohol 28 (1.30 g, 8.00 mmol) in 94% aqueous acetic acid (26 mL). The suspension was heated at 90 °C for 4 h, then cooled to room temperature and diluted with H2O (120 mL). The mixture was extracted with dichloromethane (3 ×20 mL), and the combined organic phases were washed with H2O (2 ×40 mL, saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (2 ×40 mL), and again with H2O (40 mL). The organic layer was then dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo to yield 8-pentacyclo[5.4.0.02,6.03,10.05,9]undecan-8-one (28, 1.13 g, 88%) as a white solid. The spectroscopic data are in agreement with those previously reported69: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.02–2.89 (m, 2H), 2.82–2.67 (m, 2H), 2.61–2.47 (m, 3H), 2.35–2.27 (m, 1H), 1.91–1.84 (m, 1H), 1.56–1.38 (m, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 221.8, 53.2, 48.8, 48.5, 44.7, 43.9, 43.5, 39.7, 37.8, 36.9, 31.3. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C11H12O 161.0961; Found 161.0967.

Precursor 29

Following the procedure for the synthesis of 22, magnesium turnings (0.365 g, 15.0 mmol), 4 Å molecular sieves (0.750 g), bis(cyclopentadienyl)titanium(IV) dichloride (3.73 g, 15.0 mmol), triethyl phosphite (5.14 mL, 30.0 mmol), dichlorocyclopropyl phenanthrene 23 (1.31 g, 5.00 mmol, in 10 mL THF), and caged ketone 28 (0.400 mL, 2.50 mmol, in 10 mL THF) were combined in THF (30 mL) to yield 29 as a mixture of diastereomers in a 1.0:0.8 ratio. Purification of the resulting residue by flash chromatography with silica gel (hexanes) followed by flash column chromatography with AgNO3-treated silica gel (30% AgNO3, 2:98→20:80 ethyl acetate:hexanes) afforded precursor 29 (0.213 g, 25%) as a mixture of diastereomers in a 1.0:1.0 ratio as a white solid: mp = 104–110 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.96–7.89 (m, 4H), 7.41–7.31 (m, 4H), 7.27–7.19 (m, 8H), 3.17–3.13 (m, 2H), 3.13–3.09 (m, 2H), 2.95–2.90 (m, 1H), 2.85–2.80 (m, 1H), 2.78–2.61 (m, 4H), 2.56–2.42 (m, 3H), 2.42–2.35 (m, 2H), 2.35–2.30 (m, 1H), 2.28–2.24 (m, 1H), 2.16–2.11 (m, 1H), 2.11–2.05 (m, 1H), 1.81–1.78 (m, 1H), 1.64 (d, J = 10.5 Hz, 1H), 1.56 (d, J = 10.5 Hz, 1H), 1.35 (d, J = 11.8 Hz, 1H), 1.25 (d, J = 10.5 Hz, 1H), 1.20–1.12 (m, 2H), 0.62 (dt, J = 11.9, 3.8 Hz, 1H), 0.45 (d, J = 11.9 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 135.6, 135.1, 135.0, 134.9, 134.53, 134.52, 129.33, 129.32, 129.30, 129.2, 128.9, 128.8, 128.58, 128.55, 127.74, 127.73, 127.71, 127.66, 125.80, 125.78 (2 C), 125.75, 123.4, 123.31, 123.30, 123.29, 114.1, 113.6, 48.3, 48.0, 46.93, 46.91, 46.86, 46.15, 45.8, 45.4, 43.1, 42.9 (2 C), 42.8, 41.1, 40.8, 39.3, 38.8, 35.3, 35.2, 30.4, 29.4, 22.29, 22.26, 22.1, 22.0. IR (ATR) 2954, 1485, 1440, 768, 730, 616 cm−1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C26H22 335.1794; Found 335.1802.

Photolysis of precursor 22 with diene 16

Precursor 22 (0.135 g, 0.475 mmol) and 2-oxo-4,5-diphenyl-cyclopenta-3,5-diene-1,3-dicarboxylic acid dimethylester (16, 0.188 g, 0.540 mmol) were combined in deuterated benzene (5 mL) in a quartz cuvette. The reaction mixture was placed in front of a mercury-xenon lamp and irradiated for 6 h, at which point precursor 22 had been consumed, as determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy. The solvent was removed in vacuo, and purification by flash column chromatography (0:100→10:90 ethyl acetate:hexanes) afforded adduct 11 as a white solid (0.065 g, 32%): mp = 193–195 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.14–7.07 (m, 6H), 7.04–6.99 (m, 4H), 3.49 (s, 6H), 3.14 (s, 2H), 1.90–1.77 (m, 4H), 1.57–1.48 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 169.5, 140.9, 138.9, 136.2, 131.5, 130.2, 127.5, 126.8, 52.0, 31.8, 25.7. IR (ATR) 2948, 1726, 1233, 1197, 1077, 699 cm−1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C28H26O4 427.1904; Found 427.1911

Photolysis of precursor 22

Precursor 22 (0.114 g, 0.40 mmol) was dissolved in benzene (4 mL) in a quartz cuvette, positioned in front of a mercury–xenon lamp, and irradiated for 16 h. The solvent was removed in vacuo, and purification of the resulting residue by flash chromatography with silica gel (hexanes) followed by flash column chromatography with AgNO3-treated silica gel (30% AgNO3, 1:99→10:90 ethyl acetate: hexanes) afforded allene 31 as a white solid (0.023 g, 54%) and rearrangement product 32 as a colorless oil (0.047 g, 41%): Allene 31: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 2.67–2.62 (m, 4H), 1.81–1.74 (m, 8H), 1.47–1.41 (m, 8H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 147.1, 152.4, 42.5, 29.5. IR (ATR) 2945, 2862, 1450, 1297, 1120, 733 cm−1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [2 M + H]+ Calcd for C16H20 425.3203; Found 425.3202. Rearrangement product 32: 7.65–7.60 (m, 1H), 7.53–7.48 (m, 1H), 7.37–7.29 (m, 4H), 7.25–7.20 (m, 1H), 7.13–7.09 (m, 1H), 6.60 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, 1H), 6.48 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, 1H), 2.73 (t, J = 4.0 Hz, 1H), 2.60 (t, J = 4.0 Hz, 1H), 1.92–1.78 (m, 2H), 1.53–1.23 (m, 6H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 151.9, 143.7, 139.9, 138.5, 136.6, 134.6, 130.5, 130.4, 129.5, 129.4, 128.9, 127.5, 127.0, 126.9, 126.7, 121.5, 36.8, 36.3, 29.8, 29.3, 28.9, 28.2. IR (ATR) 2947, 2864, 1482, 1436, 907, 760, 728 cm−1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C22H20 285.1638; Found 285.1617.

Photolysis of precursor 29 with diene 16

Following the procedure for the photolysis of 22, Precursor 29 (0.167 g, 0.500 mmol) and 2-oxo-4,5-diphenyl-cyclopenta-3,5-diene-1,3-dicarboxylic acid dimethylester (16, 0.174 g, 0.500 mmol) in deuterated benzene (5 mL) were irradiated for 10 h, at which point precursor 29 had been consumed, as determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Purification of the resulting residue by flash chromatography (0:100→10:90 ethyl acetate:hexanes) afforded adduct 14 as a white solid (0.241 g, 10%): Upon heating for melting point analysis, 29 turned from a white crystalline solid to a waxy yellow solid at 70–76 °C. The waxy solid melted at 181–184 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.18–6.87 (m, 10H), 3.69 (t, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 3.49–3.46 (m, 6H), 3.12 (ddd, J = 10.1, 3.4, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 2.91–2.80 (m, 2H), 2.74–2.66 (m, 1H), 2.62–2.57 (m, 1H), 2.47 (dt, J = 10.1, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 2.09–2.04 (m, 1H), 1.74 (d, J = 10.1 Hz, 1H), 1.47 (d, J = 10.1 Hz, 1H), 1.40 (dt. J = 13.2, 5.4 Hz, 1H), 0.97 (d, J = 13.2 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 169.9, 169.7, 138.69, 138.65, 137.5, 136.8, 136.6, 134.6, 134.4, 133.3, 130.2, 129.9, 127.5 (2 C), 126.83, 126.82, 51.97, 51.96, 48.9, 45.6, 44.7, 43.1, 40.2, 39.1, 37.0, 36.2, 34.6, 31.4. IR (ATR) 2948, 1727, 1339, 1200, 1141, 699 cm−1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C32H28O4 477.2060; Found 477.2074.

Photolysis of precursor 22 in cyclohexene (35)

Precursor 22 (0.172 g, 0.605 mmol) was dissolved in cyclohexene (6 mL) and transferred to a quartz cuvette. The reaction mixture was placed in front of a mercury-xenon lamp and irradiated until the starting material was consumed, as determined by H1 NMR spectroscopy (4 h). The reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo, and purification by flash chromatography (1:99 ethyl acetate:hexanes) afforded adduct 36 as a colorless oil (0.040 g, 35%): 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 2.54–2.49, (m, 2H), 1.80–1.72 (m, 2H), 1.70–1.60 (m, 6H), 1.59–1.53 (m, 2H), 1.40–1.34 (m, 4H), 1.24–1.17 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 137.3, 113.4, 38.4, 29.5, 29.4, 23.4, 21.6, 12.8. IR (ATR) 2924, 2856, 1490, 1546, 745, 720 cm−1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M• – H]+ Calcd for C14H20 187.1487; Found 187.1459.

Dichlorospirocyclopropane 37

To a mixture of adduct 36 (0.40 g, 0.21 mmol) and benzyltriethylammonium chloride (0.001 g, 0.004 mmol) in chloroform (5 mL) was added 50% aqueous sodium hydroxide (5 mL) slowly. The mixture was heated under reflux overnight, then concentrated in vacuo. Purification by flash chromatography (1:99 ethyl acetate:hexanes) afforded dichlorospirocyclopropane 37 as a white solid (0.038 g, 66%): mp = 87–89 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 2.17–2.13 (m, 2H), 2.10–2.05 (m, 2H), 1.98–1.89 (m, 2H), 1.88–1.83 (m, 2H), 1.62–1.54 (m, 4H), 1.49–1.40 (m, 4H), 1.37–1.20 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 70.4, 52.0, 41.0, 37.2, 30.9, 29.0, 21.8, 21.6, 20.4. IR (ATR) 2924, 2851, 1456, 880, 812, 791 cm−1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M – Cl]+ Calcd for C15H20Cl2 235.1253; Found 235.1235.

Photolysis of precursor 29 in cyclohexene (35)

Precursor 29 (0.125 g, 0.370 mmol) was dissolved in cyclohexene (5 mL) and transferred to an argon-flushed quartz cuvette. The reaction mixture was placed in front of a mercury-xenon lamp and irradiated until the starting material was consumed, as determined by GC/MS (8 h). The reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo, and purification by flash chromatography (1:99 ethyl acetate:hexanes) afforded adduct 39 as a mixture of diastereomers in a 1.0:0.5 ratio as a colorless oil (0.035 g, 40%): 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.00–2.92 (m, 1.5H), 2.82–2.58 (m, 6H), 2.50–2.38 (m, 1.5H), 2.35–2.20 (m, 3H), 1.82–1.64 (m, 6H), 1.63–1.54 (m, 2H), 1.53–1.44 (m, 2.5H), 1.41 (d, J = 11.8 Hz, 1H), 1.34–1.09 (m, 9.5H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 132.7, 132.6, 120.9, 120.3, 48.5, 48.3, 47.2, 47.0, 46.6, 46.3, 45.5, 45.1, 43.17, 43.16, 43.08, 43.06, 41.3, 41.0, 39.1, 38.7, 35.3, 35.2, 30.31, 30.28, 23.81, 23.78, 23.1, 23.0, 21.9, 21.8, 21.6, 21.5, 12.7, 12.6, 12.5, 12.4. IR (ATR) 2925, 2850, 1446 cm−1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + K]+ Calcd for C18H22 277.1353; Found 277.1331.

Dichlorospirocyclopropane 40

To a mixture of alkene 39 (0.060 g, 0.252 mmol) and benzyltriethylammonium chloride (0.001 g, 0.004 mmol) in chloroform (5 mL) was added 50% aqueous sodium hydroxide (5 mL) slowly. The mixture was heated under reflux overnight, then concentrated in vacuo. Purification by flash chromatography (1:99 ethyl acetate:hexanes) afforded dichlorospirocyclopropane 40 as a white solid (0.080 g, 99%). 40 was characterized as a single diastereomer 40-endo which was obtained by recrystallization with hexanes: mp = 114–117 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 2.81–2.70 (m, 2H), 2.69–2.54 (m, 3H), 2.41–2.25 (m, 3H), 2.01–1.88 (m, 2H), 1.78–1.69 (m, 2H), 1.55–1.30 (m, 9H), 1.23 (dt, J = 11.8, 3.9 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 73.8, 47.6, 47.3, 45.3, 42.8, 42.7, 42.4, 42.1, 40.8, 39.0, 36.3, 34.3, 29.2, 21.034, 21.026, 21.21, 21.20, 19.9, 19.7. IR (ATR) 2934, 2854, 1446, 1304, 1023, 600 cm−1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M – Cl]+ Calcd for C19H22Cl2 285.1410; Found 285.1417.

Racemic (1 R,4S,4aR,8aS)-1,4,4a,8a-tetrahydro-1,4-methanonaphthalene-5,8-dione 54

Following the procedure of Gaidai et al.67, freshly distilled cyclopentanone (7.50 mL, 91.0 mmol) was added to a suspension of 1,4-benzoquinone (53, 10.8 g, 100 mmol) in ethanol (22 mL) stirring at 0 °C in an ice bath. The mixture was heated to 70 °C for 15 min, then cooled to 0 °C overnight. The resulting precipitate was filtered, washed with cold ethanol, then dried in vacuo to afford adduct 54 as a yellow solid (11.1 g, 70%). The spectroscopic data are in agreement with those previously reported67: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.56 (s, 2H), 6.05 (s, 2H), 3.56–3.51 (m, 2H), 3.23–3.18 (m, 2H), 1.53 (dt, J = 8.8, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 1.44–1.40 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 199.6, 142.2, 135.4, 48.9, 48.8, 48.5. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + Na]+ Calcd for C11H10O2 197.0573; Found 197.0572.

8-pentacyclo[5.4.0.02,6.03,10.05,9]undecan-8,11-diol (55)

Following the procedure of Gaidai et al.67, caged diketone 24 (6.27 g, 36.0 mmol) in THF (30 mL) was added dropwise via an addition funnel to stirred suspension of lithium aluminum hydride (2.05 g, 54.0 mmol) in THF (16 mL). The mixture was heated under reflux for 18 h then cooled to room temperature. H2O (15 mL) was slowly added, then the mixture was neutralized with the addition of 30% aqueous H2SO4. The organic layer was separated, and the aqueous layer was extracted with dichloromethane (3 ×10 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with H2O (2 ×20 mL), dried (Na2SO4), and concentrated in vacuo to yield 8-pentacyclo[5.4.0.02,6.03,10.05,9]undecan-8,11-diol (55) as a white solid, which was used without any further purification (5.32 g, 83%). The spectroscopic data are in agreement with those previously reported67: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.93 (s, 2H), 3.85 (s, 2H), 2.70–2.64 (m, 2H), 2.60–2.54 (m, 2H), 2.38 (s, 2H), 2.35–2.29 (m, 2H), 1.63 (d, J = 10.5 Hz, 1H), 1.05 (d, J = 10.5 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 72.1, 45.7, 43.2, 40.0, 38.5, 34.6. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C11H14O2 179.1067; Found 179.1067.

7-iodo-pentacyclo[6.3.0.02,6.03,10.05,9]undecan-4-ol (56)

Following the procedure of Gaidai et al.67, 8-pentacyclo[5.4.0.02,6.03,10.05,9]undecan-8,11-diol (55, 2.67 g, 15.0 mmol) in hydroiodic acid (20 mL) was heated at 100 °C with stirring for 3 h. The reaction mixture was then cooled to room temperature, poured out into H2O (50 mL), and then extracted with dichloromethane (3 ×20 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with H2O (50 mL), 10% aqueous NaOH (50 mL), and H2O (50 mL), then dried (Na2SO4). Concentration of the organic layer in vacuo afforded 7-iodo-pentacyclo[6.3.0.02,6.03,10.05,9]undecan-4-ol (56) as brown solid, which was used without further purification (3.53 g, 82%). The spectroscopic data are in agreement with those previously reported67: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.29–4.20 (m, 1H), 4.08–3.93 (m, 1H), 3.00–1.99 (m, 9H), 1.43–1.38 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 77.3, 75.7, 57.1, 55.3, 54.7, 54.2, 53.6, 53.5, 51.8, 50.7, 48.8, 45.9, 45.1, 43.2, 41.1, 40.6, 40.3, 40.0, 34.0, 32.5, 32.0, 31.5. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M – I]+ Calcd for C11H13OI 161.0966; Found 161.0962.

4-pentacyclo[6.3.0.02,6.03,10.05,9]undecane acetate (57)

Following the procedure of Gaidai et al.67, zinc dust (7.50 g, 115 mmol) was added in portions to a solution of the unpurified mixture of 7-iodo-pentacyclo[6.3.0.02,6.03,10.05,9]undecan-4-ol (56, 2.20 g, 7.64 mmol) in acetic acid (22 mL) heated at 60 °C. The mixture was heated under reflux for 3 h, cooled to room temperature, then filtered through a plug of celite into a flask with H2O (40 mL). The unreacted zinc was washed with H2O (10 mL) and dichloromethane (10 mL), and the filtrate was extracted with dichloromethane (2 ×20 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with H2O (40 mL) followed by saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (2 ×20 mL), then dried (Na2SO4). Concentration of the organic layer in vacuo afforded 4-pentacyclo[6.3.0.02,6.03,10.05,9]undecane acetate (57) as a pale oil, which was used without further purification (1.42 g, 91%). The spectroscopic data are in agreement with those previously reported67: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.88 (s, 1H), 2.46 (s, 1H), 2.17–1.91 (m, 10H), 1.45 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.38–1.28 (m, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 171.6, 79.8, 50.8, 49.7, 47.5, 47.3, 44.8, 42.7, 41.3, 40.9, 33.7, 33.1, 21.5. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M – OAc]+ Calcd for C13H16O2 145.1017; Found 145.1018.

pentacyclo[6.3.0.02,6.03,10.05,9]undecan-4-ol (58)

Following the procedure of Gaidai et al.67, potassium hydroxide (3.12 g, 55.7 mmol) was added to a suspension of 4-pentacyclo[6.3.0.02,6.03,10.05,9]undecane acetate (57, 1.90 g, 9.30 mmol) in 50% aqueous ethanol (10 mL). The reaction mixture was heated under reflux for 3 h, then cooled to room temperature. 10% Aqueous H2SO4 was then added until the solution became slightly acidic. The mixture was extracted with dichloromethane (3 ×10 mL) and the combined organic layers were dried (Na2SO4) and concentrated in vacuo to afford pentacyclo[6.3.0.02,6.04,11.05,9]undecan-3-ol (58) was a pale solid, which was used without further purification (1.12 g, 74%). The spectroscopic data are in agreement with those previously reported67: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.17 (s, 1H), 2.60–2.56 (m, 1H), 2.18–2.03 (m, 5H), 1.98–1.88 (m, 3H), 1.48 (d, J = 10.3 Hz, 1H), 1.37–1.29 (m, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 77.5, 53.6, 52.4, 47.6, 47.3, 44.3, 43.3, 41.4, 40.8, 33.8, 33.1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + NH4]+ Calcd for C11H14O 180.1383; Found 180.1383.

pentacyclo[6.3.0.02,6.03,10.05,9]undecan-4-one (59)

Following the procedure of Dekker and Oliver69, chromium trioxide (1.20 g, 12.0 mmol) in H2O (2.0 mL) was added to caged pentacyclo[6.3.0.02,6.04,11.05,9]undecan-3-ol (58, 1.00 g, 6.00 mmol) in 94% aqueous acetic acid (20 mL). The suspension was heated at 90 °C for 4 h, then cooled to room temperature and diluted with H2O (100 mL). The mixture was extracted with dichloromethane (3 ×20 mL), and the combined organic phases were washed with H2O (2 ×40 mL, saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (2 ×40 mL), and again with H2O (40 mL). The organic layer was then dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo to yield pentacyclo[6.3.0.02,6.04,11.05,9]undecan-3-one (59, 0.951 g, 99%) as a white solid. The spectroscopic data are in agreement with those previously reported69: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 2.48–2.43 (m, 2H), 2.41–2.35 (m, 4H), 1.80–1.75 (m, 2H), 1.68 (dd, J = 10.5, 1.6 Hz, 2H), 1.42 (d, J = 10.5 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 217.6, 50.3, 47.7, 41.2, 41.1, 35.7. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C11H12O 161.0961; found 161.0957.

Precursor 50

Following the procedure for the synthesis of 22, magnesium turnings (0.365 g, 15.0 mmol), 4 Å molecular sieves (0.750 g), bis(cyclopentadienyl)titanium(IV) dichloride (3.73 g, 15.0 mmol), triethyl phosphite (5.14 mL, 30.0 mmol), dichlorocyclopropyl phenanthrene 23 (1.31 g, 5.0 mmol, in 10 mL THF), and caged pentacyclo[6.3.0.02,6.04,11.05,9]undecan-3-one (59, 0.400 g, 2.50 mmol, in 5 mL THF) were combined in THF (30 mL). Purification by flash column chromatography with silica gel (2:98 ethyl acetate:hexanes) followed by flash column chromatography with AgNO3-treated silica gel (30% AgNO3, 1:99→20:80 ethyl acetate:hexanes) afforded precursor 50 (0.289 g, 37%) as a white solid: mp = 155–157 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.97–7.91 (m, 2H), 7.41–7.34 (m, 2H), 7.26–7.19 (m, 4H), 3.17–3.12 (m, 2H), 2.28–2.16 (m, 3H), 2.10–2.04 (m, 2H), 2.03–1.98 (m, 1H), 1.74–1.67 (q, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 1.54–1.52 (m, 1H), 1.42 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.31 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.27–1.24 (m, 1H), 1.19 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 137.9, 134.92, 134.88, 129.4, 129.3, 128.8, 128.7, 127.8, 127.7, 125.79, 125.76, 123.4, 123.3, 108.3, 50.0, 49.8, 47.4, 47.3, 47.0, 46.2, 42.9, 42.7, 34.2, 34.1, 22.3, 22.2. IR (ATR) 2947, 2865, 1485, 1440, 758, 728, 610 cm−1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C26H22O 335.1794; Found 335.1800.

Photolysis of precursor 50 with diene 16

Following the procedure for the photolysis of 22, Precursor 50 (0.310 g, 0.927 mmol) and 2-oxo-4,5-diphenyl-cyclopenta-3,5-diene-1,3-dicarboxylic acid dimethylester (16, 0.323 g, 0.927 mmol) in deuterated benzene (10 mL) were irradiated for 8 h. Purification of the resulting residue by flash chromatography (0:100→10:90 ethyl acetate:hexanes) afford rearrangement product 51 as a colorless oil (0.111 g, 36%). Subsequent flash column chromatography with AgNO3-treated silica gel (30% AgNO3, 1:99→20:80 ethyl acetate:hexanes) afforded adduct 15 as a white solid (0.003 g, 1%): Rearrangement product 51: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.65–7.60 (m, 1H), 7.53–7.48 (m, 1H), 7.37–7.29 (m, 4H), 7.25–7.07 (m, 2H), 6.70–6.60 (m, 1H), 6.51–6.43 (m, 1H), 2.61–2.52 (m, 1H), 2.49–2.31 (m, 2H), 2.26–2.10 (m, 3H), 1.98–1.86 (m, 2H), 1.56–1.50 (m, 1H), 1.45–1.26 (m, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 150.9, 150.8, 143.9, 143.7, 139.99, 139.96, 138.7, 138.6, 136.9, 136.8, 135.17, 135.15, 130.6 (2 C), 130.5 (2 C), 130.1, 129.6, 129.53, 129.47, 128.63, 128.57, 127.44, 127.40, 127.04, 126.97, 126.81, 126.80, 126.64, 126.62, 122.7, 122.6, 48.8, 48.7, 48.13, 48.08, 47.7, 47.6, 47.53, 47.46, 47.4, 46.5, 46.0, 45.6, 43.9, 43.6, 42.5, 42.1, 34.6, 34.34, 34.24, 34.14. IR (ATR) 2950, 2867, 1482, 1435, 1279, 906, 757, 727 cm−1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C26H22O 335.1794; Found 335.1800. Adduct 15: mp = 62–65 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.17–7.02 (m, 8H), 7.00–6.90 (m, 2H), 3.46 (s, 6H), 2.80 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 2.45–2.40 (m, 2H), 2.00–2.91 (m, 4H), 1.65–1.62 (m, 2H), 1.49–1.45 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 169.6, 139.0, 137.4, 136.2, 132.2, 129.9, 127.5, 126.7, 52.0, 49.8, 45.9, 45.3, 37.4, 34.3. IR (ATR) 2951, 1723, 1341, 1198, 1174, 1153, 699 cm−1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C32H28O4 477.2060; Found 447.2028

Data availability

All data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information files. The X-ray crystallographic data generated in this study have been deposited in the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) database under the deposition numbers 2301554, 2301553, and 2344429. Data supporting the findings of this manuscript are also available from the authors upon request.

References

Anthony, S. M., Wonilowicz, L. G., McVeigh, M. S. & Garg, N. K. Leveraging fleeting strained intermediates to access complex scaffolds. JACS Au 1, 897–912 (2021).

Medina, J. M., McMahon, T. C., Jiménez-Osés, G., Houk, K. N. & Garg, N. K. Cycloadditions of cyclohexynes and cyclopentyne. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 14706–14709 (2014).

Hopf, H. & Grunenberg, J. in Strained Hydrocarbons. (ed. Dodziuk, H.). 375–397 (Wiley-VCH, 2009).

Knorr, R. Alkylidene carbenes, alkylidenecarbenoids, and competing species: which is responsible for vinylic nucleophilic substitution, [1 + 2] cycloadditions, 1,5-CH insertions, and the Fritsch−Buttenberg−Wiechell rearrangement? Chem. Rev. 104, 3795–3850 (2004).

Jahnke, E. & Tykwinski, R. R. The Fritsch–Buttenberg–Wiechell rearrangement: modern applications for an old reaction. ChemComm 46, 3235–3249 (2010).

Roth, A. D. & Thamattoor, D. M. Carbenes from cyclopropanated aromatics. Org. Biomol. Chem. 21, 9482–9506 (2023).

Gassman, P. G. & Gennick, I. Synthesis and reactions of 2-lithio-3-chlorobicyclo [2.2.1] hept-2-ene. Generation of the trimer of bicyclo [2.2.1] hept-2-yne. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 102, 6863–6864 (1980).

Guin, A., Bhattacharjee, S. & Biju, A. T. in Modern Aryne Chemistry. (ed. Biju, A. T.). 359–406 (Wiley-VCH, 2021).

Baxter, G. & Brown, R. Methyleneketenes and methylenecarbenes. XI. Rearrangements of cycloalkylidene carbenes. Aust. J. Chem. 31, 327–339 (1978).

Johnson, R. P. & Daoust, K. J. Interconversions of cyclobutyne, cyclopentyne, cyclohexyne, and their corresponding cycloalkylidene carbenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 362–367 (1995).

Fitjer, L., Kliebisch, U., Wehle, D. & Modaressi, S. 2+2]-cycloadditions of cyclopentyne. Tetrahedron Lett. 23, 1661–1664 (1982).

Gilbert, J. C. & Baze, M. E. Symmetry of a reactive intermediate from ring expansion of cyclobutylidenecarbene. Cyclopentyne. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 105, 664–665 (1983).

Maurer, D. P., Fan, R. & Thamattoor, D. M. Photochemical generation of strained cycloalkynes from methylenecyclopropanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 56, 4499–4501 (2017).

Fan, R., Wen, Y. & Thamattoor, D. M. Photochemical generation and trapping of 3-oxacyclohexyne. Org. Biomol. Chem. 15, 8270–8275 (2017).

Anderson, T. E., Thamattoor, D. M. & Phillips, D. L. Formation of 3-oxa- and 3-thiacyclohexyne from ring expansion of heterocyclic alkylidene carbenes: a mechanistic study. Org. Lett. 25, 1364–1369 (2023).

Erickson, K. L. & Wolinsky, J. Rearrangement of bromomethylenecycloalkanes with potassium t-butoxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 87, 1142–1143 (1965).

Mehta, G. Base-catalyzed rearrangement of. omega.-bromolongifolene. J. Org. Chem. 36, 3455–3456 (1971).

Balci, M., Krawiec, M., Ta§kesenligil, Y. & Watson, W. H. Structure of a ring enlarged product from the base induced rearrangement of dibromomethylenebenzonorbornene. J. Chem. Crystallogr. 26, 413–418 (1996).

Marchand, A. P., Kumar, K. A., Rajagopal, D., Eckrich, R. & Bott, S. G. Generation and trapping of a caged cyclopentylidenecarbene. Tetrahedron Lett. 37, 467–470 (1996).

Baumgart, K.-D. & Szeimies, G. On the intermediacy of bicyclo[3.2.O]hept-6-yne, a cyclobutyne derivative. Tetrahedron Lett. 25, 737–740 (1984).

Marchand, A. P. et al. Generation and trapping of 7-norbornylidenecarbene and a heptacyclic analog of this alkylidene carbene. Tetrahedron 54, 13427–13434 (1998).

Marchand, A. P., Namboothiri, I. N. N., Ganguly, B. & Bott, S. G. Study of a vinylidenecarbene−cycloalkyne equilibrium in the d3-trishomocubyl ring system. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 6871–6876 (1998).

Sahu, B. et al. Generation and trapping of a cage annulated vinylidenecarbene and approaches to its cycloalkyne isomer. J. Org. Chem. 77, 6998–7004 (2012).

Xu, L., Lin, G., Tao, F. & Brinker, U. Efficient syntheses of multisubstituted methylenecyclopropanes via novel ultrasonicated reactions of 1,1-dihaloolefins and metals. Acta Chem. Scand. 46, 650–653 (1992).

C. Brown, R. F. Some developments in the high temperature gas phase chemistry of alkynes, arynes and aryl radicals. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 12, 3211-3222 (1999).

Mabry, J. & Johnson, R. P. Beyond the Roger Brown rearrangement: long-range atom topomerization in conjugated polyynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 6497–6501 (2002).

Taskesenligil, Y., Kashyap, R. P., Watson, W. H. & Balci, M. Is the intermediate in the reaction of 3-bromo-6,7-benzobicyclo[3.2.1]octa-2,6-diene with potassium tert-butoxide an allene or an alkyne? J. Org. Chem. 58, 3216–3218 (1993).

Gilbert, J. C., Hou, D.-R. & Grimme, J. W. Pericyclic reactions of free and complexed cyclopentyne. J. Org. Chem. 64, 1529–1534 (1999).

Köbrich, G., Heinemann, H. & Zündorf, W. Stabile carbenoide—XXI: oligomere des “isopropylidencarbens”. Tetrahedron 23, 565–584 (1967).

Hartzler, H. The synthesis of methylenecyclopropanes via an α-elimination reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 86, 526–527 (1964).

Köbrich, G. & Drischel, W. Stabile carbenoide—XX: Über die bildung von tetrabenzylbutatrien aus 1-Chlor-2,2-dibenzylvinyllithium. Tetrahedron 22, 2621–2636 (1966).

Köbrich, G. & Ansari, F. Carbenoide reaktionen des α‐Chlor‐β‐methyl‐styryllithiums. Chem. Ber. 100, 2011–2020 (1967).

Erickson, K. L., Markstein, J. & Kim, K. Base-induced reactions of methylenecyclobutane derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 36, 1024–1030 (1971).

Erickson, K. L. Base-induced ring enlargement of halomethylenecyclobutanes. A carbon analog of the Beckmann rearrangement. J. Org. Chem. 38, 1463–1469 (1973).

Samuel, S. P., Niu, T. Q. & Erickson, K. L. Carbanionic rearrangements of halomethylenecycloalkanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 111, 1429–1436 (1989).

Seeman, J. I. Effect of conformational change on reactivity in organic chemistry. Evaluations, applications, and extensions of Curtin-Hammett Winstein-Holness kinetics. Chem. Rev. 83, 83–134 (1983).

Yang, X., Languet, K. & Thamattoor, D. M. An experimental and computational investigation of (α-methylbenzylidene)carbene. J. Org. Chem. 81, 8194–8198 (2016).

Moore, K. A., Vidaurri-Martinez, J. S. & Thamattoor, D. M. The benzylidenecarbene–phenylacetylene rearrangement: an experimental and computational study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 20037–20040 (2012).

Du, L. et al. Direct observation of an alkylidene carbene by ultrafast transient absorption spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. A 122, 6852–6855 (2018).

Zhao, Y. & Truhlar, D. G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 120, 215–241 (2007).

Weigend, F. & Ahlrichs, R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 7, 3297–3305 (2005).

Weigend, F. Accurate Coulomb-fitting basis sets for H to Rn. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 8, 1057–1065 (2006).

Hellweg, A., Hättig, C., Höfener, S. & Klopper, W. Optimized accurate auxiliary basis sets for RI-MP2 and RI-CC2 calculations for the atoms Rb to Rn. Theor. Chem. Acc. 117, 587–597 (2007).

Riplinger, C. & Neese, F. An efficient and near linear scaling pair natural orbital based local coupled cluster method. J. Chem. Phys. 138, 034106 (2013).

Riplinger, C., Sandhoefer, B., Hansen, A. & Neese, F. Natural triple excitations in local coupled cluster calculations with pair natural orbitals. J. Chem. Phys. 139, 134101 (2013).

Riplinger, C., Pinski, P., Becker, U., Valeev, E. F. & Neese, F. Sparse maps–A systematic infrastructure for reduced-scaling electronic structure methods. II. Linear scaling domain based pair natural orbital coupled cluster theory. J. Chem. Phys. 144, 024109 (2016).

Chmela, J. & Harding, M. E. Optimized auxiliary basis sets for density fitted post-Hartree–Fock calculations of lanthanide containing molecules. Mol. Phys. 116, 1523–1538 (2018).

Bach, R. D. Ring strain energy in the cyclooctyl system. the effect of strain energy on [3 + 2] cycloaddition reactions with azides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 5233–5243 (2009).

Felpin, F.-X. & Fouquet, E. A useful, reliable and safer protocol for hydrogenation and the hydrogenolysis of o-benzyl groups: the in situ preparation of an active Pd0/C catalyst with well-defined properties. Chem. Eur. J. 16, 12440–12445 (2010).

Kozel, V., Daniliuc, C.-G., Kirsch, P. & Haufe, G. C3-symmetric tricyclo[2.2.1.02,6]heptane-3,5,7-triol. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 15456–15460 (2017).

Rosenkoetter, K. E., Garrison, M. D., Quintana, R. L. & Harvey, B. G. Synthesis and characterization of a high-temperature thermoset network derived from a multicyclic cage compound functionalized with exocyclic allylidene groups. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 1, 2627–2637 (2019).

Takeuchi, D., Okada, T., Kuwabara, J. & Osakada, K. Living alternating copolymerization of a methylenecyclopropane derivative with co to afford polyketone with dihydrophenanthrene-1,10-diyl groups. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 207, 1546–1555 (2006).

Takeda, T., Sasaki, R. & Fujiwara, T. Carbonyl olefination by means of a gem-dichloride−Cp2Ti[P(OEt)3]2 system. J. Org. Chem. 63, 7286–7288 (1998).

Sarkar, S. K. et al. Detection of ylide formation between an alkylidene carbene and acetonitrile by femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 17090–17096 (2021).

Tobe, Y., Iwasa, N., Umeda, R. & Sonoda, M. Vinylidene to alkyne rearrangement to form polyynes: synthesis and photolysis of dialkynylmethylenebicyclo[4.3.1]deca-1,3,5-triene derivatives. Tetrahedron Lett. 42, 5485–5488 (2001).

Hardikar, T. S., Warren, M. A. & Thamattoor, D. M. Photochemistry of 1-(propan-2-ylidene)-1a,9b-dihydro-1H-cyclopropa[l]phenanthrene. Tetrahedron Lett. 56, 6751–6753 (2015).

Roth, A. D., Wamsley, C. E., Haynes, S. M. & Thamattoor, D. M. Adamantylidenecarbene: photochemical generation, trapping, and theoretical studies. J. Org. Chem. 88, 14413–14422 (2023).

Hoffmann, R., Gleiter, R. & Mallory, F. B. Non-least-motion potential surfaces. Dimerization of methylenes and nitroso compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 92, 1460–1466 (1970).

Cheung, L. M., Sundberg, K. R. & Ruedenberg, K. Dimerization of carbene to ethylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 100, 8024–8025 (1978).

Ohta, K., Davidson, E. R. & Morokuma, K. Dimerization paths of CH2 and SiH2 fragments to ethylene, disilene, and silaethylene: MCSCF and MRCI study of least- and non-least-motion paths. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 107, 3466–3471 (1985).

Atkins, P. & de Paula, J. in Physical Chemistry 10th edn. 827–832 (Oxford University Press, 2014).

Bachrach, S. M., Gilbert, J. C. & Laird, D. W. DFT study of the cycloaddition reactions of strained alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 6706–6707 (2001).

Laird, D. W. & Gilbert, J. C. Norbornyne: a cycloalkyne reacting like a dicarbene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 6704–6705 (2001).

Su, M.-D. The cycloaddition reactions of angle strained cycloalkynes. a theoretical study. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 52, 599–624 (2005).

Kınal, A. & Piecuch, P. Is the mechanism of the [2+2] cycloaddition of cyclopentyne to ethylene concerted or biradical? a completely renormalized coupled cluster study. J. Phys. Chem. A 110, 367–378 (2006).

Nagarkar, A. A., Yasir, M., Crochet, A., Fromm, K. M. & Kilbinger, A. F. M. Tandem ring-opening–ring-closing metathesis for functional metathesis catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 12343–12346 (2016).

Gaidai, A. V. et al. D3-trishomocubane-4-carboxylic acid as a new chiral building block: synthesis and absolute configuration. Synthesis 44, 810–816 (2012).

Eaton, P. E., Cassar, L., Hudson, R. A. & Hwang, D. R. Synthesis of homopentaprismane and homohypostrophene and some comments on the mechanism of metal ion catalyzed rearrangements of polycyclic compounds. J. Org. Chem. 41, 1445–1448 (1976).

Dekker, T. G. & Olivier, D. W. Synthesis of (D3)-trishomocuban-4-ol via carbenium ion rearrangement of pentacyclo[5.4.0.02,6.03,10.05,9]undecan-8-ol. S. Afr. J. Chem. 32, 45–48 (1979).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the NSF (Award # CHE-1955874 to D.M.T.), and the David Lee Phillips Postdoctoral Fellowship (to T.E.A.) for funding this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors, who have given approval to the final version of the manuscript. T.E.A. and D.M.T. designed the project, and D.M.T. and D.L.P. supervised the project. T.E.A. carried out the chemical reactions and computational experiments, and analyzed the data. T.E.A. wrote the manuscript and D.M.T. revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Igor Alabugin, Xiao Xiao, and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Anderson, T.E., Thamattoor, D.M. & Phillips, D.L. Probing the alkylidene carbene–strained alkyne equilibrium in polycyclic systems via the Fritsch–Buttenberg–Wiechell rearrangement. Nat Commun 15, 8313 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52390-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52390-7