Abstract

Amyloids are associated with over 50 human diseases and have inspired significant effort to identify small molecule remedies. Here, we present an in vivo platform that efficiently yields small molecule inhibitors of amyloid formation. We previously identified small molecules that kill the nematode C. elegans by forming membrane-piercing crystals in the pharynx cuticle, which is rich in amyloid-like material. We show here that many of these molecules are known amyloid-binders whose crystal-formation in the pharynx can be blocked by amyloid-binding dyes. We asked whether this phenomenon could be exploited to identify molecules that interfere with the ability of amyloids to seed higher-order structures. We therefore screened 2560 compounds and found 85 crystal suppressors, 47% of which inhibit amyloid formation. This hit rate far exceeds other screening methodologies. Hence, in vivo screens for suppressors of crystal formation in C. elegans can efficiently reveal small molecules with amyloid-inhibiting potential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Previous small molecule screens with the free-living nematode C. elegans serendipitously revealed compounds that visibly accumulate within the heads of worms1,2,3,4. This accumulation can be observed using a low-magnification dissection light microscope5. We demonstrated that the accumulated small molecules form either birefringent irregular objects, globular non-birefringent spheres, or a mixture of the two, depending on the structure of the compound5. Birefringence is an optical property that reveals the subject to harbour repeating units that uniformly alter the angle of incidence of polarized transmitted light. We showed that these birefringent objects: i) are observable within minutes of exposure of the worms to the small molecule; ii) contain the exogenous small molecule; iii) grow over time; iv) are formed exclusively in association with the pharynx cuticle; and v) are not due to the consumption of precipitate in the media by the worm5,6. Given their birefringent nature and growth over time, we refer to the birefringent objects as crystals for simplicity’s sake, although their exact biophysical nature remains to be determined. The crystals are coincident with lethality (R2 > +0.96) and likely kill younger animals because they perforate the plasma membrane of surrounding cells and rapidly grow to occlude the pharynx lumen5.

More recently, we described how the crystals form in tight association with the non-luminal face of the C. elegans pharyngeal cuticle6. This cuticle is a flexible non-collagenous chitin-rich matrix that is repeatedly shed and rebuilt at each larval stage7,8. We also constructed a spatiotemporal map for the development of the pharyngeal cuticle of C. elegans9. That study revealed the pharynx cuticle to be highly enriched with intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) and proteins with intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs)9. Many of these IDP and IDR-rich proteins have amyloidogenic features that include an enrichment in π-bonding and hydrogen-bonding capabilities, and have protofilament formation propensity9. Furthermore, we and others showed that amyloid-binding dyes specifically stain the pharyngeal cuticle9,10. Despite these findings, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and other diagnostic tests for amyloid fibrils within pharynx cuticle have failed to reveal amyloid fibrils9,11,12,13, which is consistent with the flexible nature of the cuticle14,15. Taken together, these observations indicate that the pharynx cuticle is unlikely to harbour extensive amyloid fibrils, but still has non-fibrillar material with amyloid properties given its specific staining by multiple amyloid-binding dyes and its abundance of IDPs. We refer to this amyloid-dye staining material as amyloid-like and infer that it lacks the highly ordered nature of amyloid fibrils.

Here, we show that molecules that form crystals in vivo can indeed form a crystalline lattice in vitro through π-bond interactions. We go on to show that over 50% of the 29 distinct structural scaffolds that form crystals in vivo are scaffolds of molecules that physically interact with amyloids, which we will refer to here as amyloid binders. Of note, a scaffold of a small molecule is its core structure after halogens, hydroxyls and other very small groups are removed from the molecule. Consistent with the aforementioned observations, we find that, i) nascent crystals distort the amyloid-like material within the cuticle without a concomitant effect on the chitin matrix; ii) Aβ42 fibrils can seed the formation of objects in vitro from a small molecule that forms crystals in vivo; and iii) worms incubated with the amyloid-binders Congo Red and Thioflavin S can block crystal formation. Collectively, these results suggest that the amyloid-like material in the pharynx cuticle can seed the formation of small molecule crystals. Given that well-characterized amyloid binders can block the seeding of crystals in the pharynx, we wondered whether the crystallization phenomenon could be exploited to identify other small molecules that block the ability of amyloids to seed higher-order structures such as amyloid fibrils. We therefore screened 2560 drugs and natural products for those that could suppress crystal formation in the C. elegans pharynx. The screen yielded 85 reproducible crystal suppressors, several of which are fluorescent and specifically localize to the cuticle, which is consistent with their expected site of action. The 85 crystal suppressors can be grouped into 45 distinct scaffolds. Of these 45, one third are previously characterized amyloid inhibitors. We tested 44 of the crystal suppressors that have not been previously implicated in amyloid inhibition and found that 11 (25%) inhibit Aβ42 aggregation. Together with the 29 crystal suppressors that were previously shown to inhibit amyloids, 40 of the 85 crystal suppressors (47%) inhibit amyloids, which is a hit rate far higher than most previously reported screening methodologies16,17,18. We conclude that screens for suppressors of crystal formation within the C. elegans pharynx cuticle can enrich for small molecules that inhibit amyloid formation. See Fig. 1 for a guide through our discovery approach.

A A schematic of C. elegans anatomy (from WormAtlas; used with permission). The pharynx is green. The area schematized in panels (B, D) is indicated with a black box. The area of the worms photographed in Figs. 2, 5, 6 and 8 is boxed in red. B A schematic that illustrates the anatomy of the pharynx cuticle relative to the lumen and the underlying myoepithelium. C Upon addition of a crystalizing molecule (wact-190 in this example (coloured blue)), the molecule concentrates within minutes in the pharynx cuticle where it forms birefringent objects that grow over time (i.e. crystals). The crystals kill the animals likely through perforation of the underlying myoepithelium and by growing to such an extent that prevents the animal from feeding. Through multiple screening campaigns, we identified 64 crystalizing molecules. A screen of ~2000 molecules for lethality followed by investigation of crystal formation in duplicate requires about 30 days of work. D We screened 2560 molecules for their ability to suppress the lethality associated with crystal formation (and later verified that crystal formation was suppressed), resulting in 85 crystal suppressors identified (depicted in pink). 29 of these molecules (representing 15 of the 45 distinct structural scaffolds among the 85 crystal suppressors) were known amyloid inhibitors. We speculate that amyloid inhibitors can block the ability of amyloid-like material to seed crystal formation. A screen of ~2500 molecules for suppression of crystal-induced lethality followed by detailed investigation of the suppression of crystal formation in duplicate requires about 30 days of work. E We screened a select set of crystal suppressors for their ability to inhibit Aβ42 fibril formation in vitro. We used 8 known amyloid inhibitors and 44 molecules unknown to us to inhibit amyloid formation, revealing 11 (25%) amyloid inhibitors from the latter set. In total, 47% of the crystal suppressors have evidence for their ability to inhibit amyloid formation. A survey of ~80 molecules for their ability to inhibit Aβ42 fibril formation requires about 21 days of work.

Results

Crystallizing molecules are aromatic, compact, and crystalize via π bond Interactions

We have identified a total of 48 compounds that form crystals in association with the C. elegans pharynx cuticle from our custom library of worm-active (wactive or wact) small molecules2,5 (Supplementary Fig. 1). See Fig. 2A–H for an example of small molecule crystal formation in the pharynx cuticle. To better understand how these 48 crystallizing molecules differ from the 149 true negatives that fail to crystalize, we extended our previous limited physicochemical analysis to analyze a total of 72 common physicochemical features. Each molecule was scored for each of these 72 features using either the OpenBabel tool (http://openbabel.org) and/or the SwissADME tool19 (Supplementary Data 1, Source Data file). Most features, including molecular weight and hydrophobicity (i.e., cLogP), were not significantly different between the group of 48 true positives and the group of 149 true negatives (p > 0.05). We did find that the crystallizing molecules have fewer rotatable bonds (p = 4.3E-05) and fewer hydrogen-bond donors (p = 2.4E-06) compared to the non-crystalizing wactives as previously reported5 (Fig. 2I). In addition, our more in-depth analysis revealed that the crystallizing wactives are highly aromatic (p = 2.6E-10) and more compact (i.e., smaller van der Waals volume, p = 7.3E-04). A measure that combines these features, called fraction Csp3, reports the ratio of sp3 hybridized carbon atoms over the total carbon atom count of the small molecule19 and reveals the compactness of the crystallizing molecules (p = 5.5E-09).

A–H Anterior-most region of one worm expressing the IDPC-1::GFP cuticle marker9 treated with either 1% DMSO solvent control (A–D) or 30 μM of the crystalizing molecule wact-190 (E–H) for six hours. The area of the worm photographed corresponds to the red boxed area in Fig. 1A. Orange arrows indicate the buccal cavity cuticle, the green arrows highlight the buccal collar, the white arrows indicate the cuticle that lines the channels, and the blue arrowheads highlight the birefringent crystals. Differential interference contrast (DIC), birefringent (BIRE), and the IDPC-1::GFP (cuticle) images are shown. Similar results were obtained over many trials (N ≫ 10). I An analysis of the indicated physicochemical properties of 48 true positive crystalizing molecules from our wactive library (crystal-W), 149 true negative non-crystallizing molecules from the wactive library (wactive), the 16 true positive crystalizing molecules from our RLL1200 library (crystal-R), the non-crystallizing molecules from the RLL1200 library (RLL1200), the one crystallizing molecule from the 2560 Spectrum library (dehydrovariabilin), and the non-crystallizing molecules from the Spectrum library (Spectrum). Source data are provided in the Source Data file. Crystalizing molecules have significantly fewer rotatable bonds and hydrogen-bond donors, but greater aromaticity, and compactness (as measured by van der Waals volume and fraction Csp3) compared to non-crystalizing molecules from the same library. The mean and standard error is shown. Two-sided Student’s t-tests were used to measure the indicated statistical differences between crystallizing wactives and non-crystalizing wactives, and crystallizing RLL1200 and non-crystalizing RLL1200 molecules, respectively. No adjustments for multiple comparisons were made. The p-values are as follows: molecular weight (crystallizers vs non-crystallizers, p = 7.5E-01; RLL1200 crystallizers vs non-crystallizers, p = 2.3E-03); cLogP (crystallizers vs non-crystallizers, p = 5.0E-02; RLL1200 crystallizers vs non-crystallizers, p = 3.2E-01); rotatable bonds (crystallizers vs non-crystallizers, p = 4.3E-05; RLL1200 crystallizers vs non-crystallizers, p = 6.6E-05); H-bond donors (crystallizers vs non-crystallizers, p = 2.5E-06; RLL1200 crystallizers vs non-crystallizers, p = 8.0E-01); aromatic (crystallizers vs non-crystallizers, p = 1.3E-09; RLL1200 crystallizers vs non-crystallizers, p = 1.1E-03); van der Walls volume (crystallizers vs non-crystallizers, p = 7.3E-04; RLL1200 crystallizers vs non-crystallizers, p = 2.6E-07); faction Csp3 (crystallizers vs non-crystallizers, p = 5.5E-09; RLL1200 crystallizers vs non-crystallizers, p = 3.4E-09).

To test whether these features are specific to crystallizing molecules from the wactive library, we screened two other libraries for crystallizing molecules. The first library was a custom collection of 1178 small molecules called RLL1200 (Source Data file). The second was the Spectrum library of 2560 drugs and natural products (Microsource Inc). To identify crystalizing molecules from these libraries, we first screened them for those that kill L1 larvae in our standard 6-day viability assay2, reasoning that crystalizing molecules invariably kill larvae5 and would be among the hits. We identified 70 lethal molecules from the RLL1200 library and 78 from the Spectrum library. To find crystallizing molecules among these hits, we exploited our previous finding that the sms-5(0) null mutant resists crystal-induced death by blocking crystal formation5. Re-screening the lethal hits against the sms-5(0) mutant revealed 16 molecules from RLL1200 and 1 molecule from Spectrum that: i) kill wild type; ii) fail to kill sms-5(0) mutants; and iii) form crystals in association with the pharynx (Source Data file). The physicochemical features of the RLL1200 crystallizing molecules are not significantly different from those of the wactive crystallizing molecules (p > 0.001) (Fig. 2I; Supplementary Data 1; Source Data file). Statistical analysis was not conducted with the one Spectrum hit, but its properties are similar to the means of the other crystalizing molecules. Hence, compact aromatic properties are common to most crystallizing molecules.

Given that aromatic structures are rich in π bonds, we asked whether π bond interactions might play a role in the crystallization of the small molecules in vitro. To investigate, we used crystal powder-X-ray diffraction (PXRD) with two exemplar molecules wact-190 and wact-416. Wact-190 crystallized in the triclinic crystal system with the space group P-1, whereas wact-416 crystallized in the orthorhombic crystal system with the space group Pna21 (Fig. 3A–C, F–H; Supplementary Figs. 2, 3, Supplementary Table 1). The centroids of the aromatic rings for the respective crystalized molecules had distances of 5.0 Å or less, indicating that π-π interactions play a key role in their assembly into higher ordered structures20 (Fig. 3D, I). We compared the crystallization results with their simulated data to validate the bulk phase purity of the crystals. In comparison to the computer-simulated data, the small molecule crystals displayed a similar crystalline nature, peak-pattern matching and single-phase identification, confirming the individual structural purity of the samples (Fig. 3E, J; Supplementary Fig. 3).

A The chemical structure of wact-190. B The unit cell with wact-190 molecules whose centroid lies within the unit cell with the three coordinates shown with white letters and black corresponding arrows. The wact-190 crystal unit cell shows two molecules per asymmetric unit cell in a triclinic and anti-parallel packing arrangement. C The 3D crystal packing arrangement along the b-axis (see Supplementary Fig. 3 for other aspects). D The calculated distance between the indicated centroid (pink sphere) of two adjacent molecules stacked along crystallographic b-axis within the wact-190 crystal is approximately 5.0 Å. E The experimental and simulated PXRD patterns of wact-190 molecule (see Supplementary Fig. 3 for more details). F The chemical structure of wact-416. G The unit cell with wact-416 molecules whose centroid lies within the crystal unit cell. The wact-416 crystal unit cell shows four molecules per asymmetric unit cell in an orthorhombic and parallel packing arrangement. H The 3D crystal packing (view along crystallographic b-axis) shows parallel packing for wac-416 crystals (see Supplementary Fig. 3 for other aspects). I The calculated distance between the indicated centroid (pink sphere) of the 6-membered rings of two adjacent molecules stacked along crystallographic b-axis within the wact-416 crystal is approximately 4.9 Å. J The experimental and simulated PXRD patterns of wact-416 molecule (see Supplementary Fig. 3 for more details). For (E, J), note that the PXRD results from the experimental and simulated data displayed the bulk-phase purity of both (wact-190, and wact-416) the crystals. The finely ground powdered crystals of both (wact-190 and wact-416) molecules confirms the individual structural purity of the samples by demonstrating a similar crystalline nature, peak-pattern matching, and single-phase identification when compared to the obtained simulated data.

Molecules that induce crystal formation in C. elegans are enriched with amyloid-binding scaffolds

We were curious to know the extent of the structural diversity among crystal-forming compounds. The two extremes to consider are that, i) all crystal forming compounds could be minor structural variants of the same core scaffold with different atomic decorations, or, ii) there could be no structural similarities whatsoever among crystal-forming compounds. To investigate, we created a structural-similarity network by first reducing each molecule to its core scaffold. We then linked the scaffolds that had a Tanimoto similarity coefficient of 0.8 or more (see methods). If the molecules were minor variants of one another, a single large network would result; if the molecules have little-to-no structural similarity to one another, all of the nodes in the network would be unconnected. As it is, the resulting network consisted of 6 sub-networks that are unconnected with one another and 15 singletons (Fig. 4A). Visual inspection of the molecules within the network reveals 30 structurally distinct families (Fig. 4A; Supplementary Fig. 1).

A An unsupervised structural similarity network of the 65 crystalizing molecules. Each node represents a small molecule, labelled with a wactive number or DHV (dehydrovariabilin). The link represents a Tanimoto score of structural similarity of the core scaffold of 0.8 or higher. The lower-case labels indicate groups of molecules with the same core scaffolds as indicated in (B). Nodes highlighted in pink indicate a core scaffold known to interact with amyloids (see Supplementary Data 2 and Source Data file for details). The asterisks on the wact-128 node highlights that visual inspection reveals that it is a distinct scaffold despite its connection to wact-381 and represents the 30th distinct family of crystalizing molecules (the 30 being the 12 families represented in (B), plus the 15 singletons in the lower right of the panel, plus the two singletons in the largest network (wact-390 and wact-712-1), plus wact-128). Source data are provided in the Source Data file. B Representations of the distinct core scaffolds that are able to crystalize in the worm. R, X, and Y groups are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

We next investigated whether there were any common biological activities among these crystal-forming molecule scaffolds. We searched the patent and academic literature using the SciFinder search tool21, which revealed that 15 of the 30 scaffolds (50%) are found in molecules that bind amyloids (pink-outlined nodes in Fig. 4A, Supplementary Fig. 1, and Supplementary Data 2). For example, scaffolds (a), (k) and close analogs of wact-102 have been shown to bind Aβ42 amyloid aggregates with low nanomolar affinity22,23,24. Scaffold (i) and close analogs of wact-128 and wact-415 were shown to bind prion amyloid aggregates with low nanomolar affinity25. In another example, wact-498 is a flavonoid, which is an intensively studied class of molecules that have therapeutic potential for treating amyloid-related neurodegeneration (reviewed in ref. 26). In particular, isoflavone analogs of wact-498 can inhibit Aβ42 plaque formation in a C. elegans model of the human disease27 and were shown to directly bind Aβ42 in vitro28. The same analysis was performed on 62 randomly chosen scaffolds from molecules that do not form crystals5. We found only 6 scaffolds (10%) that were previously described to bind amyloids (Supplementary Data 3). These data suggest that the collection of crystal-forming molecules is enriched with amyloid-associating scaffolds.

Crystals disrupt the amyloid-like material of the pharyngeal cuticle

We sought to better understand how crystal growth perturbs the materials of the cuticle. To investigate, we used cuticle-binding dyes and fluorescent reporters. We previously found that the red-fluorescent Congo red (CR) and blue fluorescent Thioflavin S (ThS), both of which are well-established amyloid-binding dyes29,30,31,32, specifically bind the pharyngeal cuticle9. Similarly, the blue-fluorescent Calcofluor white (CFW) and the yellow-red-fluorescent Eosin Y (EY), which bind chitin33 and its deacetylated derivative chitosan34 respectively, specifically bind the pharyngeal cuticle9.

We incubated worms in wact-190 and wact-390 (a second crystalizing molecule) for 3 h followed by 2 h of incubation in the dyes. We found that the amyloid dye patterns are often disrupted by the newly formed crystals compared to control animals without crystals that have a smooth pattern of dye staining (Fig. 5). In animals with newly formed crystals, the amyloid dyes stained displaced material in addition to the material normally stained by the dye (note that Fig. 5A–C show CFW and CR overlap while Fig. 5D–F shows the overlap between EY and ThS). This indicates that the nascent crystals are displacing the amyloid-like material as the crystals grow. We also observe a similar pattern in the background where a single IDR-rich protein (ABU-14) is tagged with GFP10 (Supplementary Fig. 4). By contrast, the chitin and chitosan dyes are relatively unperturbed (Fig. 5; Supplementary Fig. 4). In some instances, the birefringent crystals overlap with amyloid stain (blue arrows, Fig. 5). In other cases, there is little overlap between the birefringent signal and the amyloid stain (orange arrows, Fig. 5).

A–F Images of the anterior-most end of the worm. The imaging channel is indicated in each panel in the lower left as is the wactive treatment (left-hand side of micrograph series). DIC, differential interference contrast imaging; bire, birefringence imaging; CFW, calcofluor white; ThS, thioflavin S; EY, eosin Y. Merge 1 is the merge of the two dye signals. Merge 2 is the merge of the signals from the amyloid-binding dye and birefringence. Blue arrows indicate overlapping signals of the birefringent crystals and the amyloid-binding dye and highlights the staining of abnormally displaced material; orange arrows show a lack of amyloid-binding dye signal associated with birefringence signal. Note that in (A–C), the panels show the overlap between birefringence signal and CWF and CR staining, while in (D–F), the panels show the overlap between birefringence signal and EY and ThS staining. Similar results were obtained with wact-190 over 6+ trials, and with wact-390 over 2 trials. G Control for the ability of dyes to bind wactive crystals. Precipitate of wact-190 or wact-390 was formed in solution (or DMSO solvent control) and was subsequently stained with the dye indicated on the right of each set. The dyes were used at the same concentration as the in vivo staining experiments as described in the methods. Each condition was imaged using DIC, birefringence (bire.) or the appropriate fluorescent (floures.) channel, as indicated on the left of each panel. The dyes were not rinsed from the slide, which accounts for the non-specific signal in the EY fluorescent channel. The scale in the upper left micrograph applies to all images in (G). H, I Controls showing that the crystals themselves fail to fluoresce in the different channels used for imaging; D, differential interference contrast; B, birefringence; D, DAPI; C, CFP; G, GFP; Y, YFP; R, RFP channels. The scale bar in (H) also applies to (I). 60 μM of wact-190 and wact-390 was used in all experiments relevant to panels (A–I). Similar results were obtained for (G–I) over 3 trials.

To control for the possibility that the dyes non-specifically bind the crystals, we asked whether the dyes bind to in vitro precipitated small molecules. None of the dyes fluoresced brightly in association with the in vitro precipitated small molecules (Fig. 5G). We also examined the dye-staining patterns in the presence of much larger 24 h old in vivo crystals. We found many obvious examples where the larger birefringent signals do not overlap with the CR signal (orange arrows, Supplementary Fig. 5). These results suggest that nascent crystals can displace the CR-stained material, which often appears to surround the small crystals. This is consistent with the matrix-like material that surrounds the objects in the TEM images (see Fig. 3H for example in ref. 6). As the crystals grow, their larger mass becomes more distinct from the cuticle and their intimate association with the amyloid-staining material is often lost.

Amyloids likely seed the formation of small molecule crystals

As shown above, crystal-forming small molecules are rich in amyloid-binding scaffolds and crystals can perturb the amyloid-like material in the pharynx cuticle as they grow. These observations raised the possibility that the amyloid-like material in the pharynx cuticle9 might seed the formation of the small molecule crystals. If true, then coating the amyloid-like material with well-characterized amyloid-binding dyes might block crystal formation. We tested this idea by first asking whether wact-190-associated lethality of C. elegans is suppressed by co-incubating the worms with the amyloid-binding dyes CR and ThS in our standard 6-day viability assay5. Indeed, we found that CR and ThS robustly suppress wact-190 lethality whereas the chitin/chitosan-binding dyes do not (Fig. 6A). Second, we asked whether the canonical amyloid-binding dyes can suppress wact-190 crystal formation. We incubated CR and ThS, along with CFW and EY with the animals either for 3 h before incubating the worms with wact-190 for another 3 h (i.e. a pre-incubation) or at the same time as a 3 h incubation with wact-190 (i.e., a co-incubation). We found that both CR and ThS suppress crystal formation in both incubation schemes, but that the CFW and EY dyes do not (Fig. 6B, C). These data suggest that the crystals formed from the exogenous compounds may be seeded by the amyloid-like material in the pharynx cuticle, which can be blocked by other amyloid-interacting compounds.

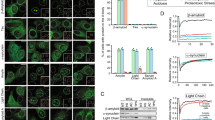

A Six-day C. elegans larval viability assays showing that amyloid binding dyes (CR and ThS) can suppress wact-190-induced lethality, but that chitin/chitosan-binding dyes (CFW and EY) cannot. Synchronized first larval stage worms were added to each well that contained the indicated concentration of dye and crystalizing wact-190 small molecule. Six days later, the viability of worms in each well was assessed (N = 3, n = 4). B Representative birefringence images that show that amyloid-binding dyes, but not chitin/chitosan-binding dyes, can suppress crystal formation. All images show the heads of individual worms similar to Fig. 2B. On the top row, animals were pre-incubated in the indicated dye or solvent control for 3 h. Then, the right-most five samples were incubated in 60 μM wact-190 for three hours without the initial dyes present. On the bottom row, animals were incubated in the indicated dye or solvent control, and for the five right-most five samples, simultaneously incubated with wact-190 (60 μM) for 3 h. The bright signal shows where crystals have formed (the blue arrows highlight a few examples). C The quantification of wact-190 birefringent (crystal) signal from worms either pre-incubated with dyes before adding 60 μM of the crystallizing wact-190 molecule (left panel) or co-incubated with dyes and 60 μM of the crystallizing wact-190 molecule (right panel). In both panels, the grey bars are controls, with the first grey bar having only DMSO solvent added without wact-190 added, which shows the background birefringence signal from worms without crystals. The two other grey control bars show that worms were either preincubated (>) for 3 h with solvent and then wact-190 (w190) was added, or that DMSO and wact-190 were co-incubated (+). The red bars show the results of preincubation (left) or coincubation (right) with Congo Red (CR) and wact-190; the dark blue bars show the same with ThioflavinS (ThS) and wact-190; the light blue bars show the same with Calcofluor White (CFW) and wact-190; and the yellow bars show the same with eosin Y (EY) and wact-190. Nearly all experiments had N = 3 and n ≥ 10) (see the Source Data file for details). Two-sided Student’s t-tests were used to assess differences. No adjustments for multiple comparisons were made. Standard error of the mean is shown. The p-values for the dye pre-incubation experiments are as follows: DMSO > DMSO vs DMSO>w190, 4.5E-19; 60 μM CR>w190 vs DMSO>w190, 4.3E-13; 1.2 mM CR>w190 vs DMSO>w190, 7.7E-14; 60 μM ThS>w190 vs DMSO>w190, 8.1E-02; 1.2 mM ThS>w190 vs DMSO>w190, 1.2E-05; 60 μM CFW>w190 vs DMSO>w190, 8.8E-01; 1.2 mM CFW>w190 vs DMSO>w190, 2.7E-01; 60 μM EY>w190 vs ETOH>w190, 1.0E-01; 1.2 mM EY>w190 vs ETOH>w190, 6.4E-01. The p values for the dye co-incubation experiments are as follows: DMSO > DMSO vs DMSO>w190, 4.5E-05; 60 μM CR>w190 vs DMSO>w190, 9.5E-03; 1.2 mM CR>w190 vs DMSO>w190, 8.7E-12; 60 μM ThS>w190 vs DMSO>w190, 9.1E-01; 1.2 mM ThS>w190 vs DMSO>w190, 1.7E-08; 60 μM CFW>w190 vs DMSO>w190, 5.3E-02; 1.2 mM CFW>w190 vs DMSO>w190, 7.4E-02; 60 μM EY>w190 vs ETOH>w190, 8.4E-01; 1.2 mM EY>w190 vs ETOH>w190, 9.8E-02.

We further investigated the idea that amyloids might seed the small molecule crystals by asking whether Aβ42 fibrils could seed the formation of wact-190 objects in vitro. We prepared solutions of Aβ42 at 25 μM and wact-190 at 25, 0.5 and 0.1 μM in PBS and incubated them overnight either alone or in combination with each other at different ratios. The next day, we examined the self-assembled structures by TEM (see Methods). We found that unusual objects associated with the Aβ42 fibrils were present in solutions with wact-190 present in either 10-fold more (see mix 1:10, Fig. 7D), 2-fold more (see mix 1:2, Fig. 7C), or 50-fold less than the concentration of Aβ42 (see mix 1:1, Fig. 7G, H), but not 250-fold less (see mix 1:1, Fig. 7K, L) or without wact-190 present (Fig. 7A, E, I, M, Q, U). We repeated this experiment twice more with the 1:10 Aβ42 to wact-190 stoichiometry with similar results (Fig. 7M–P for example). We also performed the experiment over a six-day incubation period with the 1:10 Aβ42 to wact-190 stoichiometry and observed similar results (Fig. 7Q–T) while co-incubation of Aβ42 and a non-crystalizing molecule wact-112,5 failed to yield fibrils associated with unusual objects (Fig. 7U–X). We infer that the unusual objects are self-assemblies of wact-190.

A–D Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of solutions allowed to self-assemble overnight. A–D Mixing solutions of 25 μM Aβ42 (A) and 25 μM wact-190 (B) in PBS in either a 1:2 (C) or 1:10 (D) ratio, respectively. E–H Mixing solutions of 25 μM Aβ42 (E) and 0.5 μM wact-190 (F) in PBS in a 1:1 ratio (G, H). I–L Mixing solutions of 25 μM Aβ42 (I) and 0.1 μM wact-190 (J) in PBS in a 1:1 ratio (K, L). Three independent trials of experiments shown in (A–L) were performed with similar results. M–P A second trial of mixing solutions of 25 μM Aβ42 (M) and 25 μM wact-190 (N) in PBS in a 1:1 ratio (O, P). A total of 3 trials (N = 3) of this type were performed. Q–X Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of solutions allowed to self-assemble over 6 days. Only one independent trial of the 6-day assays were performed (N = 1), but it is corroborated by the overnight assays. Q–S Mixing solutions of 25 μM Aβ42 (Q) and 25 μM wact-190 (B) in PBS in a 1:10 ratio (S). U–W Mixing solutions of 25 μM Aβ42 (U) and 25 μM wact-11 (V) in PBS in a 1:10 ratio (W) shows a lack of objects associated with amyloid fibrils. T, X show PBS-only mock samples. In all panels, examples of Aβ42 amyloid fibrils are indicated with blue arrows and examples of presumptive wact-190 objects that are associated with Aβ42 fibrils are indicated with red arrows.

Next, we used electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) to ask whether the co-assembled material contained Aβ42 and wact-190 in a stoichiometry that would be indicative of co-assembly. Indeed, we were able to detect a single peak of a mass of 4844.0 Da that is consistent with Aβ42 and wact-190 in a one-to-one molar ratio (Supplementary Fig. 6). Together with the in vivo data presented above, these data suggest that amyloids are capable of seeding wact-190 self-assembly into higher order structures.

Amyloid inhibitors are revealed in a screen for small molecule suppressors of crystal formation

Above, we show that amyloid-binding probes can block crystal formation. This raised the possibility that screens for small molecules that disrupt crystal formation might yield amyloid-inhibiting molecules. To investigate, we screened Microsource’s Spectrum library of 2560 drugs and natural products for those that might suppress crystal formation. We screened the Spectrum library in our standard six-day liquid viability assay whereby multi-well plates are seeded with first larval stage animals (see methods and ref. 2). We previously established that wact-190’s lethality in young larvae is dependent on crystal formation5. Control (solvent-only) wells are overgrown with worms after six days (Supplementary Data 4). By contrast, wells with wact-190 (3.75 μM) contain either arrested or dead L1s at the assay endpoint (Supplementary Data 4 and ref. 5). Screening the Spectrum library molecules at 60 μM yielded 85 hits that: i) suppress wact-190-induced lethality; ii) suppress wact-190 crystal formation (p < 0.05); and iii) fail to suppress lethality induced by a counter-screen control that does not form crystals (the succinate dehydrogenase inhibitor wact-112) (Supplementary Data 4).

To assess the structural diversity of the crystal suppressors, we built a structural similarity network of the molecules (Fig. 8A). A Tanimoto coefficient cut-off of 0.8 and manual inspection revealed 45 distinct core scaffolds, 17 of which are represented by multiple molecules (Fig. 8A, B).

A A structural similarity network of the 85 Spectrum library hits that suppress wact-190 lethality and crystal formation. The nodes (circles) represent a drug or natural product. The links (straight lines) represent a Tanimoto score of structural similarity of 0.8 or more (see Methods). A bold red outline indicates known amyloid inhibitors. The screen was done in duplicate with approximately 20 animals per well per molecule (N = 2, n = 20). All hits were followed up to determine whether the hits also suppressed crystal formation (p < 0.05, Student’s T-test) with at least two independent trials counting the crystals within at least 10 animals per sample (N ≥ 2, n ≥ 10) (see the Source Data file for details). Supplementary Data 4 shows the names of the compounds. B The core scaffolds among the drug suppressors of crystal formation. The small case letter preceding the scaffold name corresponds to the nodes indicated in (A). The number (n) of individual molecules within the network is indicated, as is the enrichment of that scaffold within the network relative to the entire Spectrum library (the hypergeometric enrichment p-value is shown). The benzaldehyde substructure is highlighted in blue. C Examples of the localization of fluorescent crystal suppressors (60 μM) within the pharynx cuticle of wild type animals. Calcofluor white (CFW) is used as a counter-stain control; curcu., curcumin; harmal., harmaline; erythro., erythrosine. At least 10 animals per sample were examined in detail. See Supplementary Fig. 7 for additional examples and controls. D–H In vitro assays reveal the ability of the indicated molecule to inhibit Aβ42 fibril formation in secondary nucleation assays. Adapalene (D) had a total of 8 independent trials (N = 8); Dichlorophen (E) had a total of 4 independent trials (N = 4); Closantel (F) had a total of 3 independent trials (N = 3); Candesartan (G) had a total of 3 independent trials (N = 3); Gossypol (H) had a total of 3 independent trials (N = 3). In D–H, each biological replicate (N) consisted of two technical replicates (n) and the kinetics shown are a representative example from one of these. The standard deviation is shown in all graphs. Adapalene is a known standard inhibitor of Aβ42 fibril formation61. See Supplementary Data 4 and Supplementary Fig. 9 for additional details.

We next asked whether the scaffolds of the crystal suppressors had any common known biological activities through a systematic investigation using the Scifinder Tool and PubMed (see methods). The informatic analyses of the 85 crystal suppressors revealed that 15 of the 45 scaffold groups (33%) contained at least one molecule known to play a direct role in inhibiting amyloid fibril formation (bold outline in Fig. 8A; Supplementary Data 4). Most of these scaffolds are enriched among the crystal suppressors relative to the entire Spectrum library (see Fig. 8B for p-values). Of note, a benzaldehyde substructure is significantly enriched among the crystal suppressors (2.8-fold enrichment, p = 2.3E-14; blue highlight in Fig. 8B). Importantly, we found that several of the crystal suppressors are fluorescent and of these, all specifically stain the pharyngeal cuticle (Fig. 8C and Supplementary Fig. 7).

We investigated whether the set of 85 crystal suppressors is enriched for amyloid inhibitors relative to the molecules within the Spectrum library. The lack of a comprehensive database of previously characterized small molecule amyloid inhibitors precluded a systematic analysis. We therefore randomly selected 100 molecules from the remaining Spectrum molecules to further investigate. We used the same analytical approach that we employed for the 85 crystal suppressors. We first assembled the random molecules into a structural similarity network, revealing 75 structurally-distinct scaffolds (11 clusters plus 64 singletons) (Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Data 5). We then investigated the literature for evidence of amyloid inhibition by each of the 100 random molecules (see methods). Two of the 75 scaffolds (3%) had one molecule shown to inhibit amyloids (Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Data 5). From this limited analysis, we found that the 85 crystal suppressors are over 10-fold enriched in amyloid inhibitors relative to the randomly selected set.

Small molecule suppressors of crystal formation inhibit Aβ42 fibril formation

The above results suggest that the mechanism by which molecules suppress crystal formation is intimately related to amyloid inhibition. We therefore asked whether any of the molecules for which we could not find literature-based evidence for amyloid inhibition have such capability. While different crystal suppressors have been shown to inhibit different types of amyloids (Supplementary Data 4), we focused on Aβ42 for reasons of convenience35,36. We measured the incubation time by which Aβ42 fibril formation reaches saturation and asked which molecules are capable of significantly (p < 0.05) extending the half-time of saturation by at least 50% in a standard assay35. Of the eight molecules previously shown to inhibit amyloids, 3 inhibited Aβ42 fibril formation in our assay (Fig. 8A, Supplementary Data 4), indicating that not all published results translate to this specific in vitro assay. Of the 44 unknowns tested, 11 (25%) inhibited Aβ42 fibril formation (Fig. 8A, D–H, Supplementary Data 4). Follow up analyses on the hits shown in Fig. 8E–H shows that Candesartan is a specific nucleation inhibitor while the other molecules inhibit either nucleation and/or elongation. Importantly, all of these inhibitory mechanisms require fibril binding (Supplementary Fig. 9). Hence, the ability of a small molecule to suppress crystal formation in vivo is predictive of its ability to inhibit amyloid fibril growth in vitro.

A scaffold’s ability to crystalize or suppress crystallization is interchangeable

A fortuitous comparison of the structures of crystallizers and crystal suppressors revealed that the former have fewer hydrogen-bond donors than the latter and completely lacked hydroxyl groups (p < 1E-10) (Fig. 9A, B). The crystallizers are also more halogenated than the crystal suppressors (Fig. 9C). We also found that some crystallizers share the identical scaffold as some crystal suppressors. For example, the scaffolds of the wact-128 and wact-498 crystallizers are identical to that of oxyclozanide and koparin crystal suppressors, respectively (Fig. 9D). In addition, the scaffold of the wact-415 crystallizer is similar to that of ThS, which also suppresses crystal formation (Fig. 9D). These observations raised the possibility that both classes of molecules (crystallizers and crystal suppressors) compete for the same environment within the cuticle.

A–C Physicochemical features of the 65 crystallizers and 85 crystal suppressors. A single and double asterisk indicate p < 0.001 and p < 1.0E-10, respectively, using two-sided Student’s t-tests (see the Source Data file for details). No adjustments for multiple comparisons were made. The standard error of the mean is shown. The p values are: (A), p = 1.0E-11; (B), p = 4.5E-16; (C), p = 3.2E-04. D Examples of crystallizing molecules and crystal suppressor molecules that share an identical or similar core structure. E Core scaffolds of crystal-suppressor molecules that can be turned into crystallizers (see Supplementary Data 6 for additional details). F Core scaffolds of crystallizing molecules that can be turned into crystal suppressors (see Supplementary Data 7 for additional details). G In vitro assays to characterize the ability of the indicated suppressor molecule to inhibit Aβ42 fibril formation in secondary nucleation assays (see methods). Four independent trials were performed (see Supplementary Fig. 9 for additional graphs). Each independent replicate consisted of two technical replicates and the kinetics shown are a representative example from one of these. The standard deviation is shown.

Given the structural similarities between some of the crystallizers and suppressors, we tested whether we could convert a crystalizing molecule into a crystal suppressor, and a suppressor into a crystallizer, by altering the abundance of hydroxyl and halogen decorations on the respective core structures. To do this, we searched the ZINC database of the world’s commercially available molecules37 for close structural analogs of the 85 crystal suppressors that lacked hydroxyl groups and are halogenated. We screened 33 available analogs of 6 different crystal suppressors. We found that 11 (33%) of these molecules induced object formation within the pharynx in at least 25% of the population (Supplementary Data 6; Fig. 9E). This percentage is comparable to the 36% of molecules that induce object formation from our heavily biased collection of worm bioactive small molecules5. Second, we tested 25 hydroxylated analogs of 10 different crystalizing small molecules for their ability to suppress the lethality associated with crystal-forming wact-190. Five of the 25 hydroxylated crystallizers (20%) suppress wact-190 lethality, and all of these suppress wact-190 crystal formation (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Data 7; Fig. 9F). We conclude that select core small molecule structures can be pushed towards crystal formation or its suppression by changing the relative abundance of halogens and hydroxyls that decorate the molecule. These data further support the model that crystallizers and crystal suppressors likely compete for the same niche.

Finally, we asked whether any of the five converted suppressor molecules behaved like many of the 85 Spectrum suppressors with respect to their ability to suppress amyloid fibril formation. We found that the most robust crystal suppressor (OC-17) robustly inhibited Aβ42 fibril formation (Fig. 9G; Supplementary Data 7; Supplementary Fig. 9I–J). Hence, converting crystallizers into crystal suppressors is another route with which to identify amyloid inhibitors.

Discussion

Insights into crystal formation within the C. elegans pharynx cuticle

Here, we have described our investigation into why some small molecules crystalize within the cuticle of the C. elegans pharynx. We found that: i) many crystal-forming molecules have a core scaffold known to bind amyloid; ii) crystals can displace amyloid-like material within the pharyngeal cuticle; iii) other molecules that are known to bind amyloids can block crystal formation; iv) molecules that block crystal formation specifically localize to the tissue where crystals form; and v) Aβ42 fibrils can seed the formation of wact-190 objects in vitro. Together with our previous work that shows the pharynx cuticle to be rich in amyloid-like material9, these observations suggest that the amyloid-like material within the pharynx cuticle seeds the formation of crystals.

We can speculate in general terms as to how the amyloid-like material in the pharynx cuticle might seed small molecule crystals. Our physicochemical analyses of crystalizing compounds show that they are rich with π bonding capability, hydrogen bond acceptors, and polar surface areas (this work and5). Indeed, our in vitro analysis also shows that π bond interactions likely play a key role in the ability of these molecules to crystalize within the pharynx. Concomitant with its amyloid-like nature38,39, pharynx cuticle proteins are highly enriched in π-bonding capability relative to other tissue proteomes in C. elegans and is only surpassed by the collagens9. Furthermore, the pharynx secretome is uniquely rich with polar uncharged residues with hydrogen bond donor capability (i.e., Ns, Qs, Ss, Ts, and Ys) ((p < 1E-11)9). Hence, the unique complementarity between the proteins within the pharyngeal cuticle and the crystal-forming compounds likely facilitates the seeding of small molecule crystals.

Small molecule crystallization is restricted to the pharyngeal cuticle5, yet the collagens (which are highly abundant within the body cuticle) are also rich in π-bonding capability9. Hence, there are likely additional properties of the pharynx cuticle beyond its amyloid-like nature that creates the unique niche that facilitates crystal formation. Indeed, our recent work shows that polar lipids within the pharynx cuticle likely act as a sink to concentrate the hydrophobic molecules that go on to crystallize6.

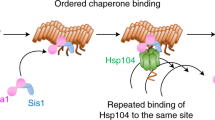

A model of crystal formation emerges upon considering these and other observations. First, polar lipids within the pharynx cuticle likely act as a sink to concentrate hydrophobic small molecules, including those that go on to crystallize6. Once concentrated, the amyloid-like material within the pharynx cuticle seeds the crystallization of small molecules that are capable of interacting with the amyloid-like material. Many of the molecules that suppress crystal formation have similar properties to the crystallizing molecules except that they are rich in hydroxyl groups and therefore cannot crystalize themselves. Instead, they mask the niche to prevent the seeding of crystals from small molecules that would otherwise do so.

Crystal formation can be exploited to identify candidate amyloid inhibitors

Through this investigation, we discovered that the phenomenon of small molecule crystal formation can be readily exploited to identify candidate inhibitors of amyloid growth. Our screen of just over 2500 small molecules for those that can suppress crystal formation yielded 85 reproducible hits. One third of these were previously known inhibitors of amyloid formation. For example, the heme and chlorophyl precursor protoporphyrin IX, its synthetic derivative haematoporphyrin, and chlorophyllide-Cu are the only porphyrins contained within the Spectrum library, and all three were found to suppress crystal formation. Multiple studies have shown that porphyrins suppress amyloid formation both in vivo and in vitro and act through direct interaction with amyloidogenic proteins40,41,42. The porphyrin ring is thought to disrupt the intrapeptide π-π interactions of the amyloidogenic peptide that is necessary to achieve superstructure42. The porphyrins may suppress crystal formation by blocking the ability of the amyloid-like material to seed crystals or may inhibit the small molecule crystallization itself.

A second common suppressor class are the flavonoids, which are a large class of polyphenolic secondary metabolites synthesized by plants43. Many flavonoid structures have been shown to antagonize amyloid formation in vitro44,45,46, in culture47, and in vivo48,49,50. Poor bioavailability may contribute to a lack of flavonoid-based therapies in the clinic, although converting anti-amyloid flavonoids into prodrugs may circumvent absorption barriers51. Flavonoid interaction with Aβ42 is driven by hydrophobic and hydrogen bond interactions that antagonize the ability of Aβ42 to adopt a β-sheet secondary structure52. Whether the flavonoids interact with amyloidogenic proteins within the cuticle in a similar way to suppress crystallization remains to be determined.

Upon testing 44 small molecules that suppress crystal formation in vivo and were not known to us at the time to inhibit amyloid formation, we found that 25% inhibit Aβ42 aggregation in our in vitro assay. This high hit rate suggests that the same property that enables a small molecule to inhibit amyloid formation allows it to block small molecule crystal formation in C. elegans. We provide evidence above that supports the idea that crystals are seeded by the amyloid-like material of the pharynx cuticle. We further speculate here that the same mechanism by which an amyloid inhibitor interacts with amyloid oligomers to disrupt polymerization allows that molecule to interact with the amyloid-like material of the pharynx cuticle. In doing so, the small molecule masks the ability of the cuticle to seed crystal formation. Future studies may elucidate the precise mechanism by which this can occur. Of course, some suppressors may suppress crystal formation via other mechanisms and may be unable to disrupt amyloid formation in other assays.

Starting with a set of molecules that inhibit crystal formation in C. elegans, we find a hit rate (25%) that is far higher than that previously reported for small molecule inhibitors of α-synuclein aggregation (<0.4%)17 using methodologies similar to ours, and inhibitors of Aβ42 (0.4%)16 or α-synuclein aggregation (<0.01%)18 using methodologies that differ from ours. Notably, C. elegans screens for suppressors of crystal-induced death are inexpensive and high-throughput, taking about a week to conduct the initial screen. Furthermore, the in vivo environment in which crystal suppressors must act is complex and, relative to other in vitro assays, may better approximate the environment in which anti-amyloid compounds must act. Hence, screens for molecules that suppress crystal-induced lethality in C. elegans represent an efficient approach to enrich for molecules that might have utility against human amyloid formation.

Methods

C. elegans culture, strains and microscopy

C. elegans strains were cultured and synchronized as previously described in ref. 5. Briefly, large populations of worms with lots of gravid adults were washed off OP50-seeded plates with M9 buffer and centrifuged at 800 × g to remove supernatant. Washes were repeated to remove as much bacteria as possible, after which worms were collected as a 1.5 mL pellet in a 15 mL conical tube. Next, the worm pellet was bleached by sequentially adding 1 mL of 10% hypochlorite solution (Sigma), 2.5 mL of 1 M sodium hydroxide solution and 1 mL double-distilled water to bring the total volume to 6 mL. The mixture was incubated on a nutator for 5 min. With 1.5 min remaining, the tube was vortexed for 10 s with two 5 s pulses after which the resulting eggs were pelleted, washed with 12 mL M9 buffer and vortexed vigorously. This was repeated three more times. After the final wash, the tube was left on a nutator at 20 °C to allow egg-hatching and checked the next day for synchronized L1s.

Six day viability assays were conducted as previously described in ref. 2. Briefly, 50 mL overnight culture of E. coli HB101 bacteria was centrifuged to pellet the bacteria and LB media was replaced with 25 mL of liquid NGM (regular NGM recipe minus agar). 40 μL of the bacterial + NGM solution was dispensed into each well of a flat-bottom 96-well plate. Compounds/dyes and appropriate solvent controls (dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or double-distilled water) controls were pinned into the 96-well plates using a 96-pin replicator with a 300 nL slot volume (V&P Scientific). Next, 20 synchronized L1s in 10 μL of M9 buffer (2 L1s/μL) obtained from overnight egg-hatching were added to each well in M9, totalling the volume/well to 50 μL. The plates were then sealed with Parafilm, wrapped in wetted paper towels, placed in a moist plastic box and incubated for 6 days at 20 °C with shaking at 200 in a New Brunswick scientific I26 incubator shaker (Day 0). On Day 6, the plate lids were removed and observed under a dissection microscope and the wells were scored for viable adult and larval stage worms/well. All 6-day viability assays were completed in four technical replicates.

The wild type N2 Bristol strain was used (obtained from the C. elegans Genetics Centre (CGC)); NQ824 qnEx443[Pabu-14:abu-14:sfGFP; rol-6(d); unc-119(+)], which was a kind gift from David Raizen10, was integrated into the genome in our lab as trIs113. For all imaging, a Leica DMRA compound microscope with a Qimaging Retiga 1300 monochrome camera was used. Before mounting worms on a 3% agarose pad for imaging, worms are washed 3X with M9 buffer and paralyzed with 50 mM levamisole or 30 mM NaN3.

Dye staining experiments were performed as previously described in ref. 9. Briefly, for Eosin Y (EY) staining, synchronized wildtype adult/L4-stage worms were washed and incubated with 0.15 mg/mL Eosin Y (EY) from a 5 mg/mL stock (dissolved in 70% ethanol; Eosin Y; Sigma-Aldrich, E4009) in 500 µL of liquid NGM for 3 hr in the dark. Worms were then paralyzed with 100 mM sodium azide (dissolved in M9 buffer) and mounted on a 10 μL 3% agarose pad on a glass slide. The above procedure was followed for incubation with 0.02% Congo Red from a 1% stock (w/v, dissolved in DMSO; Fisher chemical C580-25; CAS 573-58-0); 0.005% Calcofluor White from a 1% stock (w/v, dissolved in DMSO; Fluorescent Brightener 28, Sigma-Aldrich, CAS 4404-43-7), and 0.1% Thioflavin S (ThS) from a 10% stock (w/v, dissolved in DMSO; ThS; SIGMA, T1892-25G). ThS consists of a mixture of molecules, the two major species being of 377.1 and 510.1 MW (Enthammer et al. 2013). Since the ratio of molecules is unknown, we used an average MW of 443.6 for ThS in our calculations.

Of note, we (the authors) affirm that we have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal testing and research. Given that our experiments focused exclusively on the invertebrate nematode worm C. elegans, no ethical approval was required for any of the presented work.

Identification of crystallizing small molecules and crystal counts

The RLL1200 library of 1178 commercially available analogs of C. elegans-lethal molecules were assembled and purchased from ChemBridge (Source Data file). This library was screened at 30 µM in liquid NGM media against synchronized C. elegans L1 larvae and Rhabditophanes diutinus53 as previously described2. Briefly, E. coli strain HB101 grown overnight in LB was resuspended in an equal volume of liquid NGM. 80 µL of bacterial suspension was dispensed into each well of a flat-bottomed 96-well culture plate and 0.3 µL of the small molecules or DMSO solvent control was pinned into the wells using a 96-well pinning tool (V&P Scientific). Approximately 20 synchronized first-stage larvae (L1s) obtained from an embryo preparation on the previous day were then added to each well in 20 µL of M9. The final volume in each well was 100 µL and the DMSO concentration was 0.3% v/v. After 6 days of incubation at 25 °C the number of living worms in each well was quantified. Molecules that killed C. elegans N2 and Rhabditophanes were tested for resistance in C. elegans sms-5(ok2498) mutants at 1.9, 7.5, and 30 µM.

Crystal counts were performed as previously described in ref. 5. Briefly, fifty Synchronized L1-stage, L4-stage or young adult worms in 20 μL (2.5 L1s/μL) M9 buffer were added to wells of a 96-well plate (50 L1s/well) containing 80 μL of liquid Nematode Growth Medium (NGM) mixed with E. coli (HB101) (OD600 = 2.0–322.3) and 30 μM or 60 μM of crystal-forming compounds in duplicate wells. Depending on the experiment, three or forty-eight hours later, worms were transferred to Eppendorf tubes and washed with M9 buffer and spun down at 1800 × g for 1 min to form a ∼10 μL worm pellet. Next, worms were paralyzed by adding 10 μL of 200 mM sodium azide dissolved in M9 (to a final concentration of ~100 mM). Worms were then mounted on a 3% agarose pad on a glass slide. Live worms were then observed and scored for the presence/absence of visible birefringent crystals in the pharynx using ×40 objective of a Leica DMRA microscope. For imaging, 63X or 100X oil immersion objective lenses were used.

Characterization of the structure of wact-190 and wact-416 in vitro crystals

Both wact-190 and wact-416 crystal powder samples were loaded in a quartz zero-background sample holder. The sample was loaded in a 0.7 mm diameter capillary, to avoid preferment orientation. The powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) pattern was collected using a Bruker D8 Discover diffractometer (Bruker, Germany) equipped with Goebel’s mirrors to create a θ:θ parallel beam geometry with a sealed X-ray tube source with a copper anode (40 Kv, 40 mA) and a LYNXEYE XE linear detector. The diffraction patterns were collected between 5 and 60° 2θ with step 0.02° 2θ for 4 s per step54. The cell indexing was performed by TOPAS 5.0 software, using the LSI-Index algorithm55. The structure resolution was obtained by using the simulated annealing method in EXPO201456. The founded structure was refined by the Rietveld Method using GSAS-IIin order to precisely refine the atomic positions57. The CIF files obtained from the above method and structures were solved using Mercury software (version 2020.2.0).

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) of Aβ42 and wact-190 in vitro crystals

5 mM of each of Aβ42 and wact-190 were dissolved in pure DMSO and heated at 55 °C for 2 min for complete dissolution. Thereafter, all molecules were further diluted in 1X PBS to prepare a final concentration of 25 μM. This solution mixture was further heated at 90 °C for 3 h, followed by a vortex and the mixture was then allowed to gradually cool down overnight that resulted in self-assembled structures in some cases. The combinations used for Aβ42 plus wact-190 were 1:1, 1:2, 1:5, and 1:10 ratios. Uncombined Aβ42 and wact-190 were used as controls (25 μM in 1X PBS). The self-assembled samples of all three (5 μL, 25 μM in 1X PBS) were drop cast on a 400-mesh carbon-stabilized Formvar-coated Cu grid (Ted Pella, California, USA). The sample was allowed to bind the surface for 2 min and then the excess sample was removed using a lint-free tissue, dried at room temperature, and imaged. Sample morphology was visualized using a JEM-1400 TEM (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) accelerating at 80 kV54.

Identification of chemical suppressors of crystal-induced death and crystal formation

To identify chemical suppressors of crystal-induced death, the Spectrum Collection (MicroSource Discovery Systems Inc.) of 2560 approved drugs and natural products was screened at a concentration of 60 µM in the background of 3.75 µM wact-190. This concentration of wact-190 results in crystal formation in the pharynx causing C. elegans N2 to arrest at the L1 stage. This screen was performed in liquid NGM media as previously described2. Briefly, E. coli strain HB101 grown overnight in LB was resuspended in an equal volume of liquid NGM containing wact-190. 40 µL of bacterial suspension was dispensed into each well of a flat-bottomed 96-well culture plate and 0.3 µL of the small molecules or DMSO solvent control was pinned into the wells using a 96-well pinning tool (V&P Scientific). Approximately 20 synchronized L1s obtained from an embryo preparation on the previous day were then added to each well in 10 µL of M9. The final volume in each well was 50 µL and the DMSO concentration was 0.8% v/v. After 6 days of incubation at 20 °C the number of adult and larval worms that have progressed from arrested L1 stage was quantified. Hits that suppressed the wact-190 crystal-induced L1 arrest were retested against solvent control, wact-190, and the non-crystal forming lethal molecule wact-11 at 10 µM (see ref. 2) using the same method described above. Hits were further investigated for their ability to suppress crystal formation by co-incubating 3.75 μM of wact-190 and 60 μM of the suppressor with wild type animals in 96-well plate format. The fraction of animals with birefringent crystals was then counted at 100X magnification 48 h later, counting 20 animals per sample per trial on average.

Chemoinformatic network analysis, network display, small molecule art, and informatic analyses

Structural similarity networks were constructed based on pairwise similarity scores calculated as the Tanimoto coefficient of shared FP2 fingerprints. Pairwise similarity scores were calculated using OpenBabel (http://openbabel.org) version 3.1.0 and the networks were visualized using Cytoscape58 (version 3.8.2) as previously described2.

For each network generated, a range of Tanimoto coefficient cut-offs were tested to determine which cut-off yielded a network that clustered obvious structural analogs together as determined by manual inspection. Crystal suppressors were analysed for the presence of common scaffolds (Fig. 8b) using Filter-it version 1.0.2 from Silicos-it. Structures were drawn using ChemDraw (PerkinElmer Informatics, version 22.0). A random Spectrum network (Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Data 5) was generated by assigning all molecules within the Spectrum library a random number using excel, then sorting the molecules in order of the random number, then choosing the top 100 molecules that did not include any of the 85 crystal suppressors.

We investigated whether the crystalizing molecules and a randomly selected set of true negatives (that fail to robustly form crystals5) were previously characterized to interact with amyloids using the SciFinder Scholar tool (circa 2021–2023)21. To do this, we first assembled the crystalizing molecules into 29 groups based on distinct scaffolds and ensured that our set of 62 true negatives represented 62 distinct core scaffolds (within the set of true negatives). We then reduced each group (or single molecule if it was not part of a group) to its core scaffold structure by removing hydroxyl groups, halogens, or other very small substructures that were not in common to all members of the group. With the resulting core scaffold structures, we first searched SciFinder for any molecule that contained that core scaffold. With these resulting molecules, we then searched the associated biological literature abstracts within SciFinder for the term amyloid. Because of the simplicity of some core scaffolds, the number of respective analogs and associated abstracts numbered in the tens of thousands. In these cases, we instead first chose one molecule from the group (or the single molecule if it was not part of a group) and searched SciFinder for analogs with >80% identity. This reduced the number of relevant structures and associated literature to search and kept the focus on closely related structures. Which of the two tactics was employed is indicated in the relevant Supplementary Data file and Source Data file for each scaffold group (or single molecule). Abstracts containing the term amyloid were read (and where unclear, the associated literature was read) to ensure that evidence of either direct amyloid interaction in vitro was being measured or that if in vivo samples were being analyzed, staining that was coincident with amyloid structures was being measured. Evidence relying solely on the reduction of amyloids in vivo were not considered hits because of potential indirect mechanisms. The PubMed IDentification numbers (PMIDs) and/or patent numbers of the hits are reported in the associated Supplementary Data files and Source Data file.

We analyzed both the list of 85 crystal suppressors of crystal formation and the 100 randomly chosen molecules by searching that compound and the word amyloid in both a PubMed search and a Google search. We inspected the search results for evidence that the molecule of interest had a demonstratable inhibitory effect on amyloid formation in vitro, with or without supporting in vivo evidence. In vivo or in silico evidence of a decrease in fibril abundance without evidence of a direct effect was excluded from consideration. Molecules that lacked evidence for a direct effect, but had close structural analogs that have a demonstratable inhibitory effect on fibral formation were also excluded from further consideration.

To identify hydroxylated analogs of the crystallizing molecules and reduced analogs of the crystal suppressors, Open Babel59 (v 3.1.0) was used for the analog searches. Using SmiLib v2.060, a virtual library of approximately 55,000 variably hydroxylated analogs of 161 distinct crystallizing molecules was generated, as well as a virtual library of approximately 950,000 de-hydroxylated and variably halogenated analogs of 12 distinct crystal suppressor molecules. The 55 K and 950 K virtual libraries were de-duplicated and independently combined with de-duplicated and de-salted versions of MolPort’s All Stock Compounds Database and the ZINC In-Stock Database37. A duplicate search of these combined datasets revealed 34 crystallizer analogs and 88 crystal suppressor analogs that were available for purchase from MolPort. These analogs were further filtered by price, real availability, redundancy among parent crystal suppressors, and aqueous solubility, leaving 26 crystallizer analogs and 33 crystal suppressor analogs to be assayed.

Dye suppression assays

To test for the ability of dyes to suppress wact-190-induced worm lethality, 80 μL of NGM containing HB101 bacteria (OD600 = 1.8-2.2) and 3.75 µM wact-190 was added to each well of a 96-well plate, to which each dye was pinned (pinner model VP381N, V & P Scientific, Inc) to a final concentration of 0, 0.94, 1.88, 3.75, 7.5, 15, 30, 60, 120, 240, 480 and 960 µM, in quadruplicates. 20 µL of M9 containing synchronized wildtype L1s were then added to each well at ~50 L1/well. Three sets of controls were simultaneously set up: wact-190 + DMSO (or 70% ethanol) (no dye), DMSO + dye (no wact-190) and DMSO + DMSO (or 70% ethanol) (no wact-190, no dye). All samples were set up in quadruplets (Day 0) and incubated at 20 °C in a shaker at 200 rpm. Worm viability was scored on Day 6.

To test for the ability of dyes to suppress wact-190-induced crystal formation, synchronized wildtype young adults were added ( ~ 1000 worms in 50 µL) to a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube containing 500 µL NGM buffer and bacteria. Adult worms were either (i) pre-incubated for 3 h with 60 µM or 1200 µM of each dye or solvent (DMSO) only, rinsed 3X with M9 buffer then incubated with 60 µM wact-190 in a fresh Eppendorf tube, or (ii) co-incubated for 3 h with 60 µM or 1200 µM of each dye (or solvent) and 60 µM wact-190. Crystal formation was recorded by observing the birefringence of the wact-190 crystals both in the presence and absence of the dye. wact-190 crystal formation was compared with a negative control (no wact-190), that yielded no such birefringence. All observations and imaging were carried out using 40X objective lens of Leica DMRA2 compound microscope. The amount of birefringence was quantified using Fiji/ImageJ software. 10–20 worms per sample were analyzed in 3 biological trials.

In vitro crystal signal emission controls with and without dye staining

To test for signal emission of wact-190 or wact-390 crystals, as detected with our fluorescent microscopy filter sets, 3 µL of a 10 mM wactive stock was first added to 7 µL of water and mixed in a microcentrifuge tube, then directly added to a microscope glass slide and coverslip applied. The appearance and birefringence of the formed crystals were observed under differential interference contrast (DIC), birefringence, and fluorescence filter sets.

To test for whether the dyes specifically bind the in vitro precipitated crystals, the same procedure was followed as above, but each dye was added at a final concentration that was used in the dye staining experiments after the wactive precipitated in water. Correlation between crystal birefringence (bright white dots in a dark background) and dye fluorescence in their respective fluorescence channels was examined. All observations were made using the 10X objective lens of the Leica DMRA2 compound microscope.

Aβ42 aggregation assay

Recombinant Aβ42 expression

The recombinant peptide MDAEFRHDSGY EVHHQKLVFF AEDVGSNKGA IIGLMVGGVV IA, here called Aβ42, was expressed in the E. coli BL21 Gold (DE3) strain (Stratagene, CA, U.S.A.) and purified as described previously35. Briefly, the purification procedure involved sonication of E. coli cells, dissolution of inclusion bodies in 8 M urea, and ion exchange in batch mode on diethylaminoethyl cellulose resin followed by lyophilisation. The lyophilised fractions were further purified using Superdex 75 HR 26/60 column (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, U.K.) and eluates were analysed using SDS-PAGE for the presence of the desired peptide product. The fractions containing the recombinant peptide were combined, frozen using liquid nitrogen, and lyophilised again.

Aβ42 aggregation kinetics and fibril preparation

Solutions of monomeric Aβ42 were prepared by dissolving the lyophilized Aβ42 peptide in 6 M guanidinium hydrocholoride (GuHCl). Monomeric forms were purified from potential oligomeric species and salt using a Superdex 75 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) at a flowrate of 0.5 mL/min, and were eluted in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 8 supplemented with 200 µM EDTA and 0.02% NaN3. The centre of the peak was collected and the peptide concentration was determined from the absorbance of the integrated peak area using extinction coefficient ε280 = 1490 l Mol−1 cm−1. The obtained monomer was diluted with buffer to the desired concentration and supplemented with 20 μM Thioflavin T (ThT) from a 2 mM stock. Each sample was then pipetted into multiple wells of a 96- well half-area, low-binding, clear bottom and PEG-coated plate (Corning 3881), 80 µL per well, in the absence and the presence of different molar-equivalents of small molecules (1% DMSO). Assays were initiated by placing the 96-well plate at 37 °C under quiescent conditions in a plate reader (Fluostar Omega, Fluostar Optima or Fluostar Galaxy, BMGLabtech, Offenburg, Germany). The ThT fluorescence was measured through the bottom of the plate using a 440 nm excitation filter and a 480 nm emission filter.

Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS)

Co-assembly samples were prepared for ESI mass spectrometry by dissolving 5 mM of both Aβ42, and wact-190 in pure DMSO followed by heating at 55 °C for 2 min for complete dissolution. Thereafter, both samples are further diluted in 1X PBS to prepare the final concentration of 25 μM. This solution mixture was further heated at 90 °C for 3 h, followed by vortexing, and then the mixture was allowed to cool down slowly overnight leading to obtain the self-assembled structures. The combinations used for Aβ42 with wact-190 were a 1:10 ratio, respectively, for the mass spectrometry studies. The spectra were recorded using Liquid Chromatography (LC) coupled with a photodiode array (PDA) detector (Waters, Inc. USA) and mass spectrometer (Xevo G2-XS QToF). The stationary phase consisted of a C18 (1.7 µm, 2.1 × 100 mm) column. The mobile phase compositions were A (100% H2O + 0.1% Formic acid) and B (100% Acetonitrile + 0.1% Formic acid). The elution gradient was as follows: Linear increase to 100 % B over 10 min, then hold for 2 min and return to the starting conditions. The interpretation of data was conducted on the positive ionization in the continuum mode with MassLynx (v4.2 SCN1027, Waters Laboratory Informatics, Waters Inc. USA).

Statistics and graphs

Except where indicated, statistical differences were measured using a two-tailed Students T-test. Dot plots were generated using Prism (v8) graphing software.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data are available in the main text, the Supplementary Information and/or in the Source Data file. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers 2281946 (wact-190), and 2282440 (wact-416). These data can be obtained free of charge from www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Kwok, T. C. et al. A small-molecule screen in C. elegans yields a new calcium channel antagonist. Nature 441, 91–95 (2006).

Burns, A. R. et al. Caenorhabditis elegans is a useful model for anthelmintic discovery. Nat. Commun. 6, 7485 (2015).

Risi, G. et al. Caenorhabditis elegans Infrared-Based Motility Assay Identified New Hits for Nematicide Drug Development. Vet. Sci. 6, https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci6010029 (2019).

Galford, K. F. & Jose, A. M. The FDA-approved drugs ticlopidine, sertaconazole, and dexlansoprazole can cause morphological changes in C. elegans. Chemosphere 261, 127756 (2020).

Kamal, M. et al. The marginal cells of the Caenorhabditis elegans pharynx scavenge cholesterol and other hydrophobic small molecules. Nat. Commun. 10, 3938 (2019).

Kamal, M. et al. PGP-14 Establishes a Polar Lipid Permeability Barrier within the C. elegans Pharyngeal Cuticle. PLoS Genet. 19, e1011008 (2023).

Cox, G. N., Kusch, M. & Edgar, R. S. Cuticle of Caenorhabditis elegans: its isolation and partial characterization. J. Cell Biol. 90, 7–17 (1981).

Altun, Z. F. & Hall, D. H. in WormAtlas (2020).

Kamal, M. et al. A spatiotemporal reconstruction of the C. elegans pharyngeal cuticle reveals a structure rich in phase-separating proteins. Elife 11, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.79396 (2022).

George-Raizen, J. B., Shockley, K. R., Trojanowski, N. F., Lamb, A. L. & Raizen, D. M. Dynamically-expressed prion-like proteins form a cuticle in the pharynx of Caenorhabditis elegans. Biol. Open 3, 1139–1149 (2014).

Wright, K. A. & Thomson, J. N. The buccal capsule of Caenorhabditis elegans (Nematodea:Rhabditoidea): an ultrastructural study. Can. J. Zool. 59, 1952–1961 (1981).

White, J. G., Southgate, E., Thomson, J. N. & Brenner, S. The structure of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 314, 1–340 (1986).

Sparacio, A. P., Trojanowski, N. F., Snetselaar, K., Nelson, M. D. & Raizen, D. M. Teething during sleep: Ultrastructural analysis of pharyngeal muscle and cuticular grinder during the molt in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS One 15, e0233059 (2020).

Huang, K. M., Cosman, P. & Schafer, W. R. Automated detection and analysis of foraging behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Neurosci. Methods 171, 153–164 (2008).

Avery, L. Motor neuron M3 controls pharyngeal muscle relaxation timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Exp. Biol. 175, 283–297 (1993).

McKoy, A. F., Chen, J., Schupbach, T. & Hecht, M. H. A novel inhibitor of amyloid beta (Abeta) peptide aggregation: from high throughput screening to efficacy in an animal model of Alzheimer disease. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 38992–39000 (2012).

Pujols, J. et al. High-Throughput Screening Methodology to Identify Alpha-Synuclein Aggregation Inhibitors. Int J Mol Sci 18, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18030478 (2017).

Kurnik, M. et al. Potent alpha-Synuclein Aggregation Inhibitors, Identified by High-Throughput Screening, Mainly Target the Monomeric State. Cell Chem. Biol. 25, 1389–1402.e1389 (2018).

Daina, A., Michielin, O. & Zoete, V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 7, 42717 (2017).

Burley, S. K. & Petsko, G. A. Aromatic-aromatic interaction: a mechanism of protein structure stabilization. Science 229, 23–28 (1985).

Somerville, A. N. SciFinder Scholar. J. Chem. Educ. 75, 959–960 (1998).

Ono, M., Haratake, M., Saji, H. & Nakayama, M. Development of novel beta-amyloid probes based on 3,5-diphenyl-1,2,4-oxadiazole. Bioorg. Med Chem. 16, 6867–6872 (2008).

Watanabe, H. et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of radioiodinated 2,5-diphenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazoles for detecting beta-amyloid plaques in the brain. Bioorg. Med Chem. 17, 6402–6406 (2009).

Yang, Y. et al. Radioiodinated benzyloxybenzene derivatives: a class of flexible ligands target to beta-amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s brains. J. Med Chem. 57, 6030–6042 (2014).

Geissen, M. et al. From high-throughput cell culture screening to mouse model: identification of new inhibitor classes against prion disease. Chem. Med. Chem. 6, 1928–1937 (2011).

Ayaz, M. et al. Flavonoids as Prospective Neuroprotectants and Their Therapeutic Propensity in Aging Associated Neurological Disorders. Front. Aging Neurosci. 11, 155 (2019).

Gutierrez-Zepeda, A. et al. Soy isoflavone glycitein protects against beta amyloid-induced toxicity and oxidative stress in transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans. BMC Neurosci. 6, 54 (2005).

Hirohata, M. et al. Anti-amyloidogenic effects of soybean isoflavones in vitro: Fluorescence spectroscopy demonstrating direct binding to Abeta monomers, oligomers and fibrils. Biochim Biophys. Acta 1822, 1316–1324 (2012).