Abstract

Lynch Syndrome (LS) is a common genetic cancer condition that allows for personalized cancer prevention and early cancer detection in identified gene carriers. We used data from the All of Us (AOU) Research Initiative to assess the prevalence of LS in the general U.S. population, and analyzed demographic, personal, and family cancer history, stratified by LS genotype to compare LS and non-LS carriers. The results suggest that population-based germline testing for LS may identify up to 63.2% of carriers who might remain undetected due to lack of personal or family cancer history. LS affects about 1 in 354 individuals in this U.S. cohort, where pathogenic variants in the genes MSH6 and PMS2 account for the majority of cases. These results underscore the need to optimize the identification of LS across diverse populations and population-based germline testing may capture the most individuals who can benefit from precision cancer screening and prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lynch Syndrome (LS) is a common inherited cancer syndrome most often associated with colorectal and endometrial cancer and caused by pathogenic variants in the mismatch repair (MMR) genes, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2. A previous study estimated that LS affects approximately 1 in 279 individuals1, yet in the United States (U.S.), about 1 million individuals have LS but are unaware of their diagnosis. It is critical to identify individuals with LS, including those who are unaffected by cancer, because optimal identification of carriers allows for personalized cancer screening and risk reducing interventions.

A diagnosis of LS is often made at the time of a cancer diagnosis, where universal screening for LS is recommended with either tumor testing of the cancer for MMR deficiency or through germline genetic testing2,3. The results also have implications for family members, where at-risk relatives are eligible for germline genetic testing through “cascade testing” when a pathogenic germline MMR gene variant is identified. However, implementing cascade testing presents challenges with uptake as low as 20–40% in eligible family members4.

To optimize the identification of LS, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has classified LS, as well as Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer syndrome (HBOC) associated with pathogenic variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, and Familial Hypercholesterolemia (FH), as Tier 1 conditions5; this classification supports genetic testing in the general population given the substantial public health impact associated with adherence to preventive and risk-reducing strategies as per existing guidelines and evidence-based recommendations. Population screening for LS, regardless of personal or family cancer history, offers a promising approach for the prevention and/or early detection of multiple cancers through intensive screening and the implementation of risk-reducing strategies, including prophylactic surgeries, chemoprevention, and the prospect of immunoprevention with vaccine trials currently underway.

The All of Us (AOU) Research Initiative is a population-based cohort study designed to advance precision medicine and promote human health through the recruitment of over a million participants from various regions and backgrounds across the U.S. A goal of the Initiative is to provide insights into a wide range of health conditions and their variations across different demographic groups and to collected data, including genomic information, to personalize healthcare and offer precision prevention6,7.

Our goal was to assess the prevalence and clinical manifestations of LS in a subset of the general population enrolled in the AOU Research Initiative. Results from this study provide an opportunity to assess the penetrance of LS compared to existing studies, which are predominantly based on European populations and most often limited to aggregate data from family cancer registries, and not representative of the general population8,9. Our focus was to identify carriers with pathogenic variants in the MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2 genes associated with LS. In this work, we show that LS is common in the U.S. population, affecting 1 in 354 individuals, with a higher prevalence of pathogenic variants in the MSH6 and PMS2 genes compared to MLH1 and MSH2. Up to 63.2% of carriers in this cohort lack personal or family cancer history and a diagnosis of LS may have potentially been missed. These results support population-based germline genetic testing as a potential strategy to identify individuals with LS, particularly those unaffected by cancer. These findings also underscore the importance for future collaborative studies to evaluate optimal screening strategies for LS carriers in the U.S.

Results

LS carrier identification

Among 217,824 participants, 615 (0.3%) carriers of MMR pathogenic or likely pathogenic (P/LP) variants were identified through the ClinVar database, representing 1 in 354 individuals (Supplementary Fig. 1, 2). To evaluate the phenotypic expression of LS carriers, the analyses were limited to individuals with available medical records (n = 162,970); among these individuals, 457 carried P/LP variants: 10.9% (50/457) in MLH1, 8.7% (40/457) in MSH2, 35.4% (162/457) in MSH6, and 44.8% (205/457) in PMS2.

The demographics, cancer diagnoses, and family history of eligible participants are shown in Table 1. In accordance with the AOU data dissemination policy, we have denoted counts of 1 to 20 with an asterisk (*) to ensure that no data or statistics can be directly inferred. The median age of LS carriers and non-LS carriers was similar (58 vs. 59 years, respectively), as was gender distribution (58.6% female LS carriers vs. 61.8% among non-LS). However, LS carriers were more often White (66.3% vs. 59.8%, p < 0.05) and less often Black (13.8% vs. 18.5%, p < 0.05) than non-LS carriers.

Prevalence of cancers

Of the 457 LS carriers, 127 (27.8%) had at least one cancer, with the majority (90/127 (70.9%)) reporting history of a LS-associated cancer (colorectal, endometrial, and other (stomach, small intestine, ovaries, hepatobiliary tract, urothelial (renal pelvis, ureter, and/or bladder), prostate, and pancreas); Table 1).The prevalence of LS-associated cancers among all LS carriers was 19.7% (n = 90), compared to 5.7% in non-LS carriers (n = 9278), with odds ratio (OR) of 4.05 (95% CI: 3.21–5.11, p < 0.05). When considering all cancers, including non-LS-associated types, the prevalence among LS carriers was 27.8% (n = 127), compared to 15.5% in non-LS carriers (n = 25,200), with OR of 2.10 (95% CI: 1.71–2.57, p < 0.05). Colorectal cancer was most frequent in 10.3% (n = 47) of LS carriers, versus 1.2% in non-LS carriers (n = 2009), with OR of 9.16 (95% CI: 6.75–12.42, p < 0.05). Endometrial cancer was also common, affecting 9.3% (n = 25/268) of LS carriers, compared to 0.9% of non-LS carriers (n = 957/100408), and OR of 10.7 (95% CI: 7.05–16.2, p < 0.05). Other LS-associated cancers, had a combined prevalence of 11.4% (n = 52) in LS carriers versus 4.6% in non-LS carriers (n = 7457), with OR of 2.66 (95% CI: 2.00–3.57, p < 0.05).

Age of initial cancer diagnosis

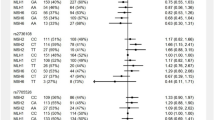

When evaluating the effect of carrier status on the age of initial cancer diagnosis (Fig. 1A), both LS carriers and non-LS carriers had a comparable median age (59.6 versus 60.5 years for LS carriers and non-LS carriers). Among LS carriers, 27.8% (127/457) developed any type of cancer, compared to 15.5% (25,200/162,513) of non-LS carriers. Among these individuals, 23.6% of LS carriers and 22.8% of non-LS carriers experienced their first cancer by the age of 50. However, when considering only LS-associated cancers, the median diagnosis age for LS carriers was 58 years, with 25.6% diagnosed before age 50; in contrast, for non-LS carriers, the median age increased to 63 years, with only 13.9% diagnosed before age 50. MLH1 carriers had a 42.1% cumulative probability of developing any cancer by age 50, which increased to 44.4% for LS-associated cancers. For MSH2 and MSH6 carriers, the probability of any cancer was 25.0% and 20.5% respectively, which increased to 27.8% and 24.1% for LS-associated malignancies. However, PMS2 carriers were more likely to have any cancer than LS-associated cancers by 50 years, with 18.2% affected versus 12.0%, respectively.

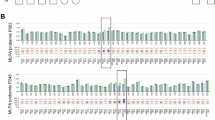

A Cumulative probability of cancer by age at initial diagnosis. B Probability of cancer development estimated using Disease-Free Survival (DFS) analysis. The exact p values based on a two-sided log-rank test are 3.547e-13 for all cancer types; 2.820e-39 for LS-associated cancers; 7.286e-29 for MLH1; 2.907e-46 for MSH2; 2.546e-11 for MSH6; 2.710e-04 for PSM2. C Impact of family cancer history on cancer risk estimated using DFS. The exact p values based on a two-sided log-rank test are 8.326e-50 for all cancer types; 3.329e-22 for LS-associated cancers; 3.277e-19 for MLH1; 9.828e-34 for MSH2; 7.430e-08 for MSH6; 2.483e-02 for PSM2. Each panel (A, B, and C) displays results in three distinct categories: the first column represents all cancer types, the second column focuses on LS-associated cancers, and the third column provides a detailed subgroup analysis by specific genotypes. The plot in blue denotes LS carriers, while black denotes non-LS carriers. For the analysis by genotype, red denotes MLH1, green denotes MSH2, sky blue denotes MSH6, and yellow denotes PMS2. The DFS analysis, utilizing reported ages at initial cancer diagnosis, defines an “event” as the occurrence of any type of cancer. Data are presented as median survival times with 95% confidence intervals.

Probability of cancer diagnosis

We assessed the probability of cancer development by conducting a survival analysis using the age at initial cancer and estimated disease-free survival (DFS) by genotype (Fig. 1B). In this context, the ‘event’ is the initial cancer occurrence and ‘time to event’ is the age at first cancer; using DFS effectively measures cancer risk from birth. LS carriers have a higher probability of developing any cancer with increasing age compared to non-LS carriers, with a more pronounced probability for LS-associated cancers (Fig. 1B). Specifically, MLH1 and MSH2 carriers had a higher probability of LS-associated cancers (with lower DFS) compared to MSH6 and PMS2 carriers; PMS2 carriers did not exhibit a significantly higher probability of developing any cancer (p = 0.048), compared to MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6 carriers (P < 0.05).

Results from the DFS analysis by gene for specific LS-associated cancers (colorectal, endometrial, and other LS associated) are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3 and reveal that (1) LS carriers exhibited a reduced DFS for all LS-associated cancers, with a more pronounced reduction for colorectal and endometrial cancers; (2) Among “Other LS cancers”, carriers of MLH1 and MSH2 genes showed a noticeable decrease in DFS compared to non-LS carriers, with more pronounced effect in MSH2 carriers. However, MSH6 and PMS2 carriers did not show significant differences from non-LS carriers.

Family history of cancer

To assess family cancer history, we examined subjects’ responses to a standardized questionnaire provided to all participants which included ‘Personal and Family Health History.’ Among respondents who provided personal and family health history data on parents, siblings, children, and grandparents (n = 81,458), an association was found between LS carrier status and family history of LS-associated cancers; 47.3% (112/237) of carriers reported such a family history compared to 33.9% (27,530/81,221) of non-LS carriers, OR of 1.75 (95% CI: 1.35–2.26, p < 0.05). When evaluating family cancer history among carriers with a personal history of a LS-associated cancer, the OR increased to 5.26 (95% CI: 3.51–7.89, p < 0.05). A family history of either any cancer or LS-associated cancers significantly increased overall risk of cancer development (p < 0.05, two-sided log-rank test; Fig. 1C). When stratified by genotype, presence of family history of LS-associated cancers showed a higher cancer risk for each specific MMR gene (p < 0.05); this risk was more pronounced for MLH1 and MSH2 compared to MSH6 and PMS2 (Fig. 1C).

Discussion

Our study uses unique clinical and genomic data from a subset of the U.S. general population enrolled in the AOU Research Initiative to report on the prevalence and phenotypic manifestations of LS. We find that LS is common, affecting about 1 in 354 individuals in the U.S. population, and that pathogenic variants in the MSH6 and PMS2 genes account for the majority of carriers. The previous estimate of LS affected 1 in 279 individuals was derived from population-based cancer registry data and modeling studies rather than a “real world” cohort available through the AOU Research Initiative1.

Two recent population-based studies evaluating germline testing data for LS from the Healthy Nevada Project and the United Kingdom (UK) Biobank, report similar prevalence of LS at 0.3% (66/20,463) and 0.2% (76/49,738), respectively10,11; however, both studies were limited by their small sample of LS carriers, with only 66 and 76 LS carriers with accessible medical records, compared to our analyses of 457 LS carriers through AOU. The prevalence of LS associated cancers among carriers was 28.8% (19/66) for the Healthy Nevada Project and 22.4% (17/76) for the UK Biobank, and lowest at 19.7% (90/457) for AOU. The rate of family history reporting of LS-associated cancers among LS carriers was 24.5% (112/457) in the AOU, similar to 22.7% (15/66) in the Healthy Nevada Project, but higher at 36.8% (28/76) in the UK Biobank. Although cancer diagnoses in the AOU data are based on medical records, which may raise reliability issues, the large sample size and diversity of the AOU cohort enhance the robustness of our findings; this limitation however highlights the importance of incorporating clinical data in the future.

The probability of cancer development by genotype was consistent with existing reports. LS carriers exhibited a reduced DFS in all three categories of LS-associated cancers (colorectal, endometrial, and other LS-associated), with a more pronounced reduction for colorectal and endometrial cancers. This aligns with well-established evidence that LS significantly increases the risks for these cancers12,13. Furthermore, among the four genes, MLH1 and MSH2 carriers experienced a more substantial decline in DFS compared to those with MSH6 and PMS2, consistent with studies indicating colorectal cancer risks of approximately 40–50% for MLH1 and MSH2, versus 10–20% for MSH6 and PMS214. These findings reinforce that pathogenic variants in MLH1 and MSH2 genes are often associated with a higher lifetime cancer risk compared to MSH6 and PMS2. However, the gene-specific risk estimates across different cancer types may be limited by small sample sizes in this study; in compliance with the AOU data dissemination policy which limits reporting of any frequencies less than 20, we aggregated smaller counts of LS-associated cancers into an ‘other’ category (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 3).

Our analysis on family history of cancer indicates that cancer risk further escalates for LS carriers who also have a family history of cancer. Family history was limited to first-degree relatives (FDRs) and grandparents to ensure more accurate reporting, since previous studies have shown high accuracy of self-reported family history of cancer among FDRs, regardless of educational level15,16. While the percent of participants who reported a family history of LS-associated cancer was significantly higher among LS carriers than non-carriers, we acknowledge the potential impact of reporting bias which may lead to an underestimation of cancer incidence in individuals without a known family history, as these individuals might be less likely to be aware of or report familial cancer occurrences. It is also possible that the interaction of family history on disease penetrance can impact estimated risks, which may include (but are not limited to) biological interactions, confounding variables, and potential resulting surveillance bias. Future longitudinal analyses that track carriers over time are needed to improve cancer risk estimates, which would also reduce the aforementioned limitations related to family cancer history. Our findings however underscore the significance of family history in assessing cancer risk among LS carriers, which currently impact recommendations for more personalized LS cancer screening and other risk reducing interventions.

In addition, results from this study suggest that a significant number of Americans have LS but may be unaware of their diagnosis. Up to 63.2% of LS carriers (MLH1: 23, MSH2: 21, MSH6: 96, PMS2: 149) in this study had no medical records indicating LS and were presumably unaware of their LS status until undergoing genetic testing through the AOU Research Initiative. These individuals identified as LS carriers lacked a personal and family history of any LS-associated cancer diagnosis and therefore did not meet clinical criteria for genetic testing; the majority of these carriers had pathogenic variants in PMS2, which is known to be associated with a weaker LS phenotype8. However, this data may not reliably capture how many individuals may have had an existing LS diagnosis prior to being identified through the genetic analyses provided by the AOU Research Initiative. We therefore were unable to provide accurate results on the incremental gain provided by population-based genetic testing in the identification of LS. An additional potential limitation may be related to self-selection bias, where those individuals with personal and/or family cancer history may have been more inclined to participate in the AOU Research Initiative, and therefore represent an enriched population for LS. Conversely, if less enthusiastic individuals participated, this figure might also be an underestimate. Survivor bias, where individuals with the most severe early-onset disease are not included as they would have died prior to recruitment, can also impact risk estimates; this bias is more likely to remove very highly penetrant variants from the cohort, which is likely to deflate penetrance estimates. However, given the AOU recruitment criteria—which aims to include participants from all walks of life, with no specific exclusion criteria related to health status, age, or other demographic factors, except for a minimum age requirement of 18 years old (see Methods)6,7—we believe that these study participants are more representative of the general population. Compared to the Healthy Nevada study, which reported an under-diagnosis rate of 77.3%10, our estimate is lower at 63.2%.

As the AOU program continues to expand its participant base and data collection, with the inclusion of additional environmental and lifestyle factors, we anticipate gaining even deeper insights into the benefits of germline genetic testing and the associated cancer risks, most notable among diverse racial and ethnic populations. Furthermore, as a potential shift towards population-wide screening for conditions such as LS, HBOC, and familial hypercholesterolemia is contemplated, the need for more accurate cancer risk estimates becomes apparent. These estimates are crucial as they will influence screening and risk-reducing recommendations with implications on costs, interpretation and perception of risks, and an array of ethical and societal concerns. The data from the AOU Research Initiative has the potential to address a number of uncertainties that relate to population-wide genetic screening for LS and the impact on cancer prevention.

Methods

AOU recruitment and enrollment

Initiated in May 2018, the AOU project expands across a network of over 340 engagement sites. The initiative is primarily focused on recruiting adults aged 18 and older and capable of providing informed consent. Integral components of data collection involve health surveys, electronic health records (EHRs), physical measurements, adoption of digital health tools, and analysis of biospecimens. By June 2021, the program had enrolled ~387,000 individuals, with around 295,000 contributing both biospecimens and survey responses; as of May 2021 over three-quarters of participants were from historically underrepresented backgrounds in medical research. At the time of our analysis, version 7 (v7) Curated Data Repository (CDR) was available which included participant data between May 2018 and July 2022 with a cutoff date of 7/1/20226,7.

AOU EHR data

The EHR data from AOU adheres to the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (OMOP) Common Data Model (CDM). In this model, “condition concepts” represent standardized clinical findings or observations documented during healthcare encounters. These findings can range from diseases and injuries to other health-related issues identified for a patient17,18. To identify cancer cases in our cohort, we extracted all “condition concepts” and their corresponding concept names for each subject. Based on a string-matching approach, we identified cancer-related disease concept names containing terms like “canc”, “malig”, “adenoc’, or ‘tumo”. These concept names were reviewed for accuracy (FK, SDR) and the excluded diagnoses included secondary cancers (e.g., secondary malignant neoplasm of trunk) or those that did not directly signify a cancer diagnosis (e.g., cancer-related fatigue). As a result, the total of 771 unique cancer related diagnosis codes were identified in the AOU database, which we categorized into 30 distinct cancer types at the organ level. From these cancers, we identified eight LS-associated cancers: colon/rectal, stomach, small intestine, endometrial, ovarian, hepatobiliary, urothelial/bladder, prostate, and pancreas; We classified all remaining cancers as non-LS-associated. For more detailed information on “condition concepts”, refer to the Athena website (https://athena.ohdsi.org/search-terms/start). We gathered self-reported demographic information, including race, gender, sex, ethnicity, and age, from data within individuals’ EHRs. We provided both sex and gender information about our analysis cohort in Table 1.

AOU genomic data

In the v7 CDR, we used file with short read whole genome sequencing (WGS) single nucleotide variant and indel variants of four LS genes from AOU researcher workbench, specifically the one annotated as ‘Hail MT multiallelic split’. This file includes a total of 1,281,259 genomic variants for 245,394 individuals, with multiallelic sites split into separate records. After removing related samples using auxiliary files indicating relatedness, the dataset was refined to 1,281,289 variants for 230,019 individuals. To narrow our focus on rare variants, we filtered for those with a population-specific allele frequency less than 1%; this yielded 1,137,955 variants for the same 230,019 individuals. We applied further quality controls, including a minimum depth of coverage (DP) of 10, a variant allele frequency of at least 0.25, and a genotype quality score of 20 or higher; these parameters did not impact the variant number nor subject number. When combined with existing demographic data, our final refined dataset encompassed information for 217,872 participants, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. Later in the analysis, we identified and excluded 5 patients who had inconsistencies in their data, specifically those who were recorded as male but reported having endometrial cancer. This adjustment led to a revised total of 217,867 eligible subjects (Table 1).

We examined the phenotypical manifestations associated with LS by genotype, focusing on the genes MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2. To identify P/LP variants in LS genes, we employed a stringent classification based on multiple submissions or expert panel reviews19 in ClinVar. We excluded variants with uncertain or ambiguous annotations. From this refined data in ClinVar, we identified 2477 unique P/LP variants distributed as follows: 776 for MLH1, 760 for MSH2, 654 for MSH6, and 287 for PMS2. To address the potential impact of PMS2CL, a pseudogene containing a ~ 11 kb region highly homologous to exons 12–15 of PMS220,21, which can lead to false variant calls, we analyzed the P/LP variants of PMS2 within these exons. Among the 287 PMS2 P/LP variants listed in the ClinVar database, 40 were located within exons 12–15. Of these, five variants were identified 47 times, affecting 43 individuals, demonstrating high coverage and mapping accuracy. Although the AOU genomic initiatives employ joint calling to enhance sensitivity and whole-genome sequencing with mean coverage greater than 70×, coupled with stringent mapping scores and excellent Phred Q30, recent guidelines from the AOU research program still recommend against reporting P/LP variants in the PMS2 exons 12–15 region21, despite these improvements. Consequently, we excluded these five variants in PMS2 exons 12–15 from our analysis. The difference in results before and after this exclusion was minimal.

Family history survey

In the survey questionnaire, we focused on cancer-specific questions found under the “Personal and Family Health History” section. Participants indicate whether a cancer diagnosis pertained to “Self”, “Sibling”, “Mother”, “Father”, “Son”, “Daughter”, or “Grandparent.” The associated LS cancers included in the study were colon/rectal, ovarian, stomach, pancreatic, kidney, bladder, and endometrial cancers.

Statistical analysis

Analyses and statistical comparisons were conducted using the Python 3 programming language in the AOU Researcher Workbench, a cloud-based platform. We used Z-test to compare the proportion of each demographic category (e.g., gender, race, ethnicity) between LS carriers and non-LS carriers. We performed Mann-Whitney U Test for comparing age between the two groups. Regarding personal and family cancer history, we used Chi-square test to assess association between LS carrier status and the occurrence of cancers or LS carrier status and having a family history of cancer. Survival analysis was conducted with the lifelines library in Python, which was used to create a Kaplan-Meier survival plot for disease-free survival. The results were reported with 95% CI.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data generated in this study have been deposited in the All of Us Researcher Workbench within the Controlled Tier. Currently, academic, not-for-profit, and healthcare organizations are eligible to apply for an All of Us Data Use and Registration Agreement. This agreement is a prerequisite for accessing the data available through the All of Us Researcher Workbench. To gain access to the data, users must complete the following steps: 1) Apply for Researcher Workbench access at https://workbench.researchallofus.org/login. 2) Complete access requirements for Registered Tier data. 3) Complete the Controlled Tier Training. The raw data are protected and are not available due to data privacy laws. We have provided sample data along with our code. When this code is run following the instructions provided in the All of Us Researcher Workbench, it generates all the data necessary to reproduce the study results. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code used in the All of Us Research Workbench, along with sample data, has been deposited in Code Ocean and can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.6608437.v1.

References

Win, A. K. et al. Prevalence and penetrance of major genes and polygenes for colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 26, 404–412 (2017).

Gupta, S. et al. NCCN guidelines insights: genetic/familial high-risk assessment: colorectal, version 2.2019: featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. J. Natl Compr. Cancer Netw. 17, 1032–1041 (2019).

Yurgelun, M. B. & Kastrinos, F. Tumor Testing for Microsatellite Instability to Identify Lynch Syndrome: New Insights into an Old Diagnostic Strategy. Vol. 37, 263–265 (American Society of Clinical Oncology, 2019).

Stone, J. K. et al. A Canadian provincial screening program for Lynch Syndrome. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 118, 345–353 (2023).

Abul-Husn, N. S. et al. Implementing genomic screening in diverse populations. Genome Med. 13, 17 (2021).

Sullivan, F., McKinstry, B. & Vasishta, S. The “All of Us” research program. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 1883–1884 (2019).

Ramirez, A. H. et al. The all of us research program: data quality, utility, and diversity. Patterns 3, 100570 (2022).

Moller, P. The Prospective Lynch Syndrome Database reports enable evidence-based personal precision health care. Hered. Cancer Clin. Pract. 18, 6 (2020).

Lee, G. et al. Multi-syndrome, multi-gene risk modeling for individuals with a family history of cancer with the novel R package PanelPRO. Elife 10, e68699 (2021).

Grzymski, J. J. et al. Population genetic screening efficiently identifies carriers of autosomal dominant diseases. Nat. Med 26, 1235–1239 (2020).

Patel, A. P. et al. Association of rare pathogenic DNA variants for familial hypercholesterolemia, hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome, and lynch syndrome with disease risk in adults according to family history. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e203959 (2020).

Meyer, L. A., Broaddus, R. R. & Lu, K. H. Endometrial cancer and Lynch syndrome: clinical and pathologic considerations. Cancer Control 16, 14–22 (2009).

Yurgelun, M. B. & Hampel, H. Recent advances in lynch syndrome: diagnosis, treatment, and cancer prevention. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 38, 101–109 (2018).

Seppala, T. T., Burkhart, R. A. & Katona, B. W. Hereditary colorectal, gastric, and pancreatic cancer: comprehensive review. BJS Open 7, zrad023 (2023).

Roth, F. L. et al. Consistency of self-reported first-degree family history of cancer in a population-based study. Fam. Cancer 8, 195–202 (2009).

Murff, H. J., Spigel, D. R. & Syngal, S. Does this patient have a family history of cancer?: an evidence-based analysis of the accuracy of family cancer history. JAMA 292, 1480–1489 (2004).

Ahmadi, N., Peng, Y., Wolfien, M., Zoch, M. & Sedlmayr, M. OMOP CDM can facilitate data-driven studies for cancer prediction: a systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 11834 (2022).

Park, K. et al. Exploring the potential of OMOP common data model for process mining in healthcare. Plos One 18, e0279641 (2023).

Richards, S. et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 17, 405–424 (2015).

Gould, G. M. et al. Detecting clinically actionable variants in the 3’ exons of PMS2 via a reflex workflow based on equivalent hybrid capture of the gene and its pseudogene. BMC Med. Genet. 19, 176 (2018).

Venner, E. et al. Whole-genome sequencing as an investigational device for return of hereditary disease risk and pharmacogenomic results as part of the Research Program. Genome Med. 14, 34 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under K25CA267052 (J.P.), R01CA257333 (F.K., C.H.) and funding from the Full Life Foundation. The All of Us Research Program is supported by the National Institutes of Health, Office of the Director: Regional Medical Centers: 1 OT2 OD026549; 1 OT2 OD026554; 1 OT2 OD026557; 1 OT2 OD026556; 1 OT2 OD026550; 1 OT2 OD 026552; 1 OT2 OD026553; 1 OT2 OD026548; 1 OT2 OD026551; 1 OT2 OD026555; IAA #: AOD 16037; Federally Qualified Health Centers: HHSN 263201600085U; Data and Research Center: 5 U2C OD023196; Biobank: 1 U24 OD023121; The Participant Center: U24 OD023176; Participant Technology Systems Center: 1 U24 OD023163; Communications and Engagement: 3 OT2 OD023205; 3 OT2 OD023206; and Community Partners: 1 OT2 OD025277; 3 OT2 OD025315; 1 OT2 OD025337; 1 OT2 OD025276. In addition, the All of Us Research Program would not be possible without the partnership of its participants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.K., C.H., S.D.R., X.K., H.K., and J.P. conceived the presented idea, contributing to both the analysis and manuscript writing. H.K. and X.K. collected P/LP variants from ClinVar and helped to organize genomic data, ensuring efficient execution of the study. F.K., S.D.R. and J.P. reviewed and refined the cancer types that were mined via string match search from participants’ EHR data. F.K., C.H., S.D.R., and X.K. provided clinical oversight and assisted in the interpretation of the results. All authors gave critical feedback, shaping the research, analysis, and final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Xiao Fan, Kevin Monahan and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, J., Karnati, H., Rustgi, S.D. et al. Impact of population screening for Lynch syndrome insights from the All of Us data. Nat Commun 16, 523 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52562-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52562-5

This article is cited by

-

Physician-mediated genetic testing is direct to consumer in all but name

Nature Medicine (2025)

-

Germline variants in patients from the Iranian hereditary colorectal cancer registry

Cancer Cell International (2025)