Abstract

Pythium sensu lato (s.l.) is a genus of parasitic oomycetes that poses a serious threat to agricultural production worldwide, but their severity is often neglected because little knowledge about them is available. Using an internal transcribed spacer (ITS) amplicon-based-metagenomics approach, we investigate the occurrence, abundance, and diversity of Pythium spp. s.l. in 127 corn fields of 11 European countries from the years 2019 to 2021. We also identify 73 species, with up to 20 species in a single soil sample, and the prevalent species, which show high species diversity, varying disease potential, and are widespread in most countries. Further, we show species-species co-occurrence patterns considering all detected species and link species abundance to soil parameter using the LUCAS topsoil dataset. Infection experiments with recovered isolates show that Pythium s.l. differ in disease potential, and that effective interference with plant hormone networks suppressing JA (jasmonate)-mediated defenses is an essential component of the virulence mechanism of Pythium s.l. species. This study provides a valuable dataset that enables deep insights into the structure and species diversity of Pythium s.l. communities in European corn fields and knowledge for better understanding plant-Pythium interactions, facilitating the development of an effective strategy to cope with this pathogen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pythium (nom. cons.) sensu lato (s.l.) is a genus that includes many important species, of which more than 300 species are soil-borne plant pathogens1,2. Taxonomically, Pythium s.l. is classified in the domain Eukarya, the kingdom Chromista, the phylum Oomycota, the class Oomycetes, the order Pythiales and the family Pythiaceae. As an opportunistic phytopathogen, Pythium s.l. infects its hosts mainly in times of stress and susceptibility, such as during germination3,4,5,6. Molecular phylogenetic studies suggested a paraphyly of Pythium s.l., which lead to a proposal by Uzuhashi’s group in 2010 to distinguish the genus more precisely. Based on morphological characteristics and phylogenies of the mt-cytochrome c oxidase subunit 2 (cox2) and the D1-D2 domains of the nuc-28S rDNA7, subdivided Pythium s.l. into five genera: Pythium sensu stricto (s.s.) (clades A-D), Globisporangium (clades E-G, I and J), Elongisporangium (clade H), Ovatisporangium (clade K, synonym Phytopythium) and Pilasporangium (differs from the 11 lettered clades). The infection can occur at various plant development stages, with infection of seeds during or before germination being the most important8. The wide host range of Pythium s.l. causes severe yield and quality losses of crops and agricultural products. Among the ten most destructive corn diseases in 2012, the genus Pythium s.l. accounted for about 11% yield loss in the northern US9, with root rot and damping-off being the major plant diseases10,11,12. The dilemma is that in most cases, the Pythium s.l. infection goes unnoticed as it occurs below ground, and the symptoms are often misdiagnosed as nutrient deficiencies. The disease potential of Pythium s.l. is therefore greatly underestimated or completely neglected12.

Although infection usually causes only minor damage to plants, it can lead to significant yield and quality losses8. Among crops, corn and soybeans are highly susceptible to Pythium s.l., with e.g. G. irregulare and G. ultimum being particularly infectious in the United States3,13. Pythium s.l. differ in their pathogenicity and disease potential14. For instance, G. ultimum is particularly aggressive with a broad host range, while G. sylvaticum is a highly pathogenic species for soybeans but has moderate virulence in corn as observed in the US3. Infection and damage from G. ultimum occur in Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Japan, Korea, South Africa, and many others14. In Europe, intense corn cultivation increases the risk of diseases15, such as damping off4 and root rot16,17,18. Several pathogenic species of Pythium s.l. affect the growth of corn seedlings at varying initial temperatures5,19. However, there is currently very limited information about the disease potential, the occurrence, distribution, and species diversity of Pythium s.l. communities in Europe.

Meta-barcoding, aided by next-generation sequencing (NGS), revolutionizes microbiome survey research, enabling the comprehensive identification of different organisms, or species even within an environment. The most commonly used genomic markers in soil microbiome research are the Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) region and the 16S-rRNA marker. Both genetic regions contain highly conserved and variable regions, allowing the development of primers that bind to the conserved regions, while the variable regions in between are used for taxonomic determination and phylogenetic analysis20,21,22,23. In addition to ITS region24,25,26, the Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (CO1, COX1) is frequently used for the taxonomic identification of oomycetes27,28 and Pythium spp. s.l.29 Also, the divergent regions D1-D3 of the large subunit (LSU) of ribosomal DNA are suitable for the taxonomic identification of oomycetes25,30. Nevertheless, due to the highly conserved nature of LSU, some closely related species could not be taxonomically differentiated using LSU, and also ITS and CO1 often fails to distinguish certain species because of barcoding gaps25.

Efforts are underway worldwide to identify host resistance and genes against Pythium spp. s.l.31,32. Recently, more than 60 potential resistance loci against corn stalk rot, caused by P. aristosporum, were reported from a genome-wide association study in corn33. However, the high species diversity of Pythium s.l. communities and the complex pathogenicity of the different species hamper resistance breeding32. No effective resistance genes and hybrids are available for corn34, and also, the molecular interactions between corn and Pythium s.l. are not fully understood. Transcriptional regulation is a critical process in plant response to pathogen attacks, often controlled by hormone signaling networks, in which SA and JA are key players35,36. Both JA biosynthesis and JA-controlled resistance responses are essential for corn immunity to Pythium s.l.37. In addition to transcriptional regulation, miRNAs form an additional regulatory layer controlling the defense response to G. ultimum infection in a post-transcriptional manner38. A deep understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the plant-Pythium interactions may help develop novel strategies to manage Pythium s.l.

In this study, we investigate the occurrence, abundance, and species diversity of Pythium s.l. in corn fields across Europe using a meta-barcoding approach. Over a period from 2019−2021, soil samples from 127 sites across 11 countries were collected for this study. In total, we identify 73 species of Pythium s.l. including Pythium s.s., Globisporangium and Ovatisporangium (Phytopythium), with soil samples containing up to 20 species. We identify and characterize several species prevalent in European corn fields, showing high species diversity and differences in their disease potential. We demonstrate that an effective interference with plant hormone networks to suppress JA (jasmonate)-mediated defenses may be a crucial part of the virulence mechanism of pathogenic Pythium spp. s.l.

Results

Pythium s.l. communities are highly diverse across Europe

A set of 127 soil samples collected from France, Italy, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Spain, Romania, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Switzerland, and Austria (Fig. 1) were deployed for ITS amplicon sequencing. ITS-sequence analysis revealed a high diversity of Pythium s.l. (Fig. 2) in soil samples across Europe. In total, 73 different species of Pythium s.l. were detected, from which 3 were annotated as Phytopythium, 30 as Pythium s.s. and 40 as Globisporangium. Noticeably, a single soil sample (P20_L27) contained up to 20 species, while no Pythium s.l. was detectable in two samples (P20_L07 and P20_L37, Fig. 2). As illustrated by the heatmaps and the annotation of the data from three sampling years (Fig. 2), multiple species were profoundly dominant; 46 different species were detected in 2019, from which the ten most common species were G. attrantheridium (33), G. heterothallicum (31), G. sylvaticum (31), P. monospermum (30), P. aff. hydnosporum (25), P. arrhenomanes (21), G. ultimum var. ultimum (21), G. rostratifingens (20), G. intermedium (18) and G. apiculatum (12). In 2019, the highest diversity was observed at site P19_L15 with 15 different species of Pythium s.l., while the lowest was at site P19_43 with 3 species. Similar results were given for 2020 and 2021 (Fig. 2). Although sampling sites decreased to 38 locations in 2020, the number of species increased to 56. The most frequent species include G. attrantheridium (27), P. aff. hydnosporum (26), G. sylvaticum (26), G. heterothallicum (24), P. arrhenomanes (21), G. rostratifingens (20), P. monospermum (13), G. intermedium (12), G. ultimum var. ultimum (12) and G. apiculatum (8). In 2021, the high species diversity of 57 Pythium s.l. species were detected at 44 sampled locations, represented primarily by G. attrantheridium (32), G. heterothallicum (30), P. aff. hydnosporum (26), G. sylvaticum (23), G. ultimum var. ultimum (18), P. monospermum (16), P. arrhenomanes (12), G. intermedium (12), G. rostratifingens (12) and G. apiculatum (9). The highest diversity was detected at site P21_L19 with 12 species, whereas P21_L48 had the lowest diversity with only one detected species (Fig. 2). Several species were frequently found at many sampled sites, which are G. attrantheridium (92 sites), G. heterothallicum (85), G. sylvaticum (80), and P. aff. hydnosporum (77), respectively. Six other species were identified at different sites (P. monospermum at 59 sites, P. arrhenomanes at 54 sites, G. rostratifingens at 52 sites, G. ultimum var. ultimum at 51 sites, G. intermedium at 42 sites, and G. apiculatum. at 29 sites), these constitute the ten most abundant Pythium s.l. species in all European soils investigated.

Geographic distribution of all 127 sampled locations from 11 countries including France, Italy, Germany, Belgium, Netherlands, Spain, Romania, Hungary, Austria, Switzerland and Czech Republic. Sampling was conducted at 45 sites in 10 countries in 2019, 38 in 9 countries in 2020, and 44 in 11 countries in 2021.

The use of bait samples allows an additional assessment of Pythium s.l. distribution in Europe. Fewer species were detected from the bait samples than in the soil samples (Fig. 3). Of the ten predominant species in the soil samples, eight can also be classified as predominant in the bait samples, which underlines their dominant role in Europe. They are G. sylvaticum (76 sites), G. attrantheridium (66), G. ultimum var. ultimum (56), G. heterothallicum (54), G. intermedium (40), G. apiculatum (33), P. aff. hydnosporum (23), and G. rostratifingens (17) were very common at most sampled sites (Fig. 3). In addition, the two species P. aff. torulosum (22) and Phytopythium boreale (15) were among the ten most abundant species in the bait samples.

The relative abundance of Pythium s.l. is similar in all years

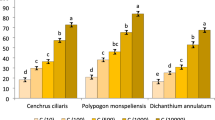

The relative abundance of the ten most prevalent species of Pythium s.l. identified in each sampling year were calculated. As shown in the bar- and boxplots (Fig. 4), the occurrence and abundance of these were, for the most part, consistent over the years. The abundance of the ten species was similar yearly, whereas the abundance of G. sylvaticum and P. monospermum varied considerably among the three sampling years. In 2020, G. sylvaticum was more abundant than in 2019 and 2021. Furthermore, the corresponding boxplot illustrates that relative abundance variation was greater in 2020 than in the other two years. In contrast P. monospermum was more abundant in 2019 compared with 2020 and 2021. These data indicate that the relative abundance of Pythium s.l. fluctuated to some extent over the three years, but significant changes were observed only for G. sylvaticum and P. monospermum.

Barplot (A) and Boxplot (B) of relative abundance pooled for the three sampling years 2019, 2020, 2021 of the ten most abundant Pythium s.l. species G. apiculatum, G. attrantheridium, G. heterothallicum, G. intermedium, G. rostratifingens, G. sylvaticum and G. ultimum var. ultimum, P. aff. hydnosporum, P. arrhenomanes and P. monospermum. Crossed circles represent the mean values of relative abundance of the respective species. Significant differences were tested two-sided against the mean (grand mean) of all samples for ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 (degrees of freedom = 112), N = 127.

The occurrence and frequency of Pythium s.l. varied in European countries

To assess the occurrence and abundance of Pythium s.l. in European countries, we compared the relative abundance of the ten most common species with the grand mean of all countries. As shown in Fig. 5A and Table S7, G. ultimum var. ultimum was significantly (p < 0.05) more abundant in Belgium and tended (p < 0.1) to be more abundant in the Netherlands. While G. heterothallicum is significantly more abundant in France and Romania compared with the mean of all countries, G. apiculatum tended to be more abundant in Germany and P. monospermum more in Italy. There are very few statistically significant differences between the various countries. The diversity of all Pythium s.l. was additionally investigated under consideration of the influencing factor of soil texture class. Depending on their clay content (Table S8), the investigated soils were divided into three classes: light ( < 15%), medium (15–25%) and heavy ( > 25%). We defined Pythium s.l. density by the total number of reads detected in the soil sample of a respective site. Interestingly, the light soils showed the highest Pythium s.l. density, followed by the medium and heavy soils. None of these soil texture classes differ significantly from the mean value of all classes (Table S9). In addition to the lower inoculum density, a lower dispersion of Pythium s.l. abundance in the heavy soils was observed, while the highest dispersion occurred in the light soils (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, the species diversity was examined to assess the impacts of the soils. The highest diversity of different species was found in the medium soils and differed tendentially (p = 0.08903) from the mean of all soil texture classes (Table S10), while the light soils, even with a similar median level as the medium soils, did not show any difference from the mean. For the heavier soils, this difference is lower than the mean of all soil texture classes but not significant (Fig. 5C).

Relative abundance of the ten most abundant Pythium s.l. species G. apiculatum, G. attrantheridium, G. heterothallicum, G. intermedium, G. rostratifingens, G. sylvaticum and G. ultimum var. ultimum, P. aff. hydnosporum, P. arrhenomanes and P. monospermum, pooled for the sampled countries Netherlands, Belgium, Hungary, Germany, Spain, Romania, Switzerland, France, Austria and Italy (Czech Republic excluded). Significant differences were tested two-sided against the mean of all countries (grand mean) for ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 (degrees of freedom = 112), N = 126 (A). Pythium s.l. abundance of the sites classified into light, medium and heavy soil texture compared to the mean of Pythium s.l. abundance of all sites (grand mean). Significant differences were tested two-sided against the mean of all samples for ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 (degrees of freedom = 110), N = 127 (B). Number of different species of Pythium s.l. for sites with the three soil texture classes light, medium and heavy compared to the mean of all sites (grand mean). Significant differences were tested two-sided for ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 (degrees of freedom = 110), N = 127 (C).

ASV-based diversity varies greatly between species of Pythium s.l

The ASVs were used to evaluate the diversity of Pythium s.l. between years as well as among Pythium s.l. species. Figure 6 summarizes the numbers of different ASVs identified in each of the three individual sample years and in all three combined years. For this purpose, the sequenced ITS region and the resulting ASVs were used to compare the abundance of the ten most abundant species of Pythium s.l., P. aff. hydnosporum, G. attrantheridium, G. rostratifingens, P. sp. nov, G. sylvaticum, and G. ultimum var. ultimum showed a higher diversity in 2020 than in 2019 and 2021 (Fig. 6), while the ASV counts for P. arrhenomanes and G. intermedium were same in 2019 and 2020. The diversity of ASVs for G. heterothallicum and P. monospermum was the highest in 2019, from which G. heterothallicum had the highest ASV count in 2019, while P. monospermum remains stable between years. It was noticeable that G. heterothallicum had the highest diversity in all three years, followed by G. attrantheridium, P. monospermum, and G. sylvaticum. Similarly, most ASVs for G. sylvaticum were identified in 2020 (16) and only 4 in 2019 and 2 in 2021, respectively.

Number of amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) of the ten most abundant species of Pythium s.l. (G. apiculatum, G. attrantheridium, G. heterothallicum, G. intermedium, G. rostratifingens, G. sylvaticum and G. ultimum var. ultimum, P. aff. hydnosporum, P. arrhenomanes and P. monospermum) for the years 2019, 2020, 2021, separately and pooled (A). Number of locations of the ten most abundant amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) of the ten most abundant species of Pythium s.l. (P. aff. hydnosporum, G. apiculatum, P. arrhenomanes, G. attrantheridium, G. heterothallicum, G. intermedium, P. monospermum, G. rostratifingens, G. sylvaticum and G. ultimum var. ultimum) (B).

Similarly, 13 ASVs were taxonomically assigned to G. rostratifingens in 2020, and only 3 in 2019 and 2021. The same trend was observed for G. ultimum var. ultimum, although the differences were slightly smaller with 7 ASVs in 2020 and 4 and 2 ASVs in 2019 and 2021. While P. arrhenomanes showed a higher ASV count in 2019 and 2020 than in 2021, in contrast to P. aff. hydnosporum, which exhibits a lower ASV count in 2019 and 2020. A total of 19 and 18 ASVs were taxonomically assigned to G. sylvaticum and P. monospermum. We identified 22 ASVs for P. sp. nov, 15 for G. rostratifingens, 13 for G. intermedium, and 8 for G. ultimum var. ultimum. Therefore, the lowest ASV number was observed for G. ultimum var. ultimum (Fig. 6A). In addition to the number of different ASVs, we analyzed their corresponding occurrence.

Figure 6B shows the number of locations for the ten most abundant ASVs of the ten most abundant species of Pythium s.l. For P. aff. hydnosporum, G. apiculatum, G. attrantheridium, G. intermedium, G. rostratifingens, G. sylvaticum, and G. ultimum var. ultimum, only one ASV was detected at each of almost all locations where the respective species was detected. This was for P. aff. hydnosporum at 75 of 77, for G. apiculatum at 25 of 36, for G. attrantheridiumat 88 of 92, for G. intermedium at 28 of 42, for G. rostratifingens at 46 of 50, for G. sylvaticum at 79 of 80 and for G. ultimum var. ultimum at 50 of 51 locations, respectively. This effect was particularly pronounced for P. aff. hydnosporum, G. sylvaticum, G. rostratifingens and G. ultimum var. ultimum. The dominance of a single ASV is also evident for G. apiculatum, G. attrantheridium, and G. intermedium, although this effect is somehow less pronounced for these species. Notably, only 7 and 8 different ASVs were identified for G. apiculatum and G. ultimum var. ultimum, respectively. It is also important to consider that G. apiculatum and G. intermedium were detected at fewer locations overall compared to species such as G. attrantheridium or G. sylvaticum. However, for other species, such as P. arrhenomanes, G. heterothallicum, and P. monospermum, this was not the case. Multiple ASVs were frequently detected for each of these three species.

Co-occurrence between Pythium s.l. and their linkage with soil parameters

To investigate co-occurrence patterns between Pythium s.l. species, Pearson correlations were calculated (Fig. 7A). Overall, negative correlations were predominant for all 73 identified species (1853 negative, 848 positive). While G. camurandrum showed the highest number of significant correlations (73), P. acanthium exhibits the lowest (Fig. 7B). The highest number of negative correlations was observed for G. myriotylum. Interestingly, the top ten most abundant Pythium s.l. showed predominantly positive correlations. The strongest negative correlation was given between P. monospermum and G. ultimum var. ultimum.

Only a fraction of Pythium s.l. species showed a significant correlation with the pH value and the organic content of the soil. G. debaryanum is solely negatively correlated with soil pH. Regarding the organic matter content in the soil, positive correlations were found to be related to P. inflatum and P. sp. nov. (Fig. 8).

Pearson correlation (two-sided) of soil pH (measured in CaCl2) and organic content (OC) of significantly (***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05) correlated species across Europe (A). Overview of Pythium s.l. linked to soil pH and soil organic content (B). OC = organic content, NEG = negative correlation, POS = positive correlation.

Pythium s.l. differ in their disease potential on corn

In order to evaluate the pathogenicity of the Pythium s.l. species identified in this study, we conducted infection experiments on corn using G. ultimum var. ultimum and G. attrantheridium, and compared the germination rate, shoot fresh, and root dry weight of infected plants with those of non-infected plants. The results showed that both species caused characteristic disease symptoms but differed in severity. Thereby, G. ultimum var. ultimum showed more pronounced disease symptoms than G. attrantheridium (Fig. 9). The germination rate of corn was severely affected by infection with G. ultimum var. ultimum, but not with G. attrantheridium (Fig. 9A, Table S11). Furthermore, a reduction in shoot fresh- and root dry weight was caused by G. ultimum var. ultimum, although this reduction also occurred in G. attrantheridium (Fig. 9A, D, E, F, G, Table S12, and Table S13). In order to understand the underlying mechanisms, we monitored plant response by comparing the expression levels of 4 phytohormone-marker genes involved in plant defense response using RT-qPCR (Fig. 10). They were PR1 (SA marker), PDF1.2 (JA marker), and ETR2 (ET marker) as well as NCED3 (ABA marker). Remarkably, we found that the expression of PR1 was high in roots infected with either G. ultimum var. ultimum or G. attrantheridium compared with the non-infected control. While the expression levels of ETR2 and NCED3 did not alternate substantially, PDF1.2, a marker gene for JA-mediated defense response, was significantly suppressed in roots infected by G. ultimum var. ultimum, but not by G. attrantheridium (Fig. 10, Table S14).

Influence of G. attrantheridium and G. ultimum var. ultimum on corn after infection. Comparison of germination capacity, mean shoot fresh weight, and mean root dry weight of corn plants infected with G. attrantheridium or G. ultimum var. ultimum (A), compared to the non-infected control (NC). Statistical differences were tested two-sided by a multiple contrast test for ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 (degrees of freedom = 110). Error bars indicate the standard deviation (n = 6). Non-infected corn plant (B). Stereomicroscopic image of non-infected corn roots in ½ MS medium (C). Corn plants infected with G. attrantheridium (D). Stereomicroscopic image of corn roots infected with G. attrantheridium in ½ MS medium (E). Corn plants infected with G. ultimum var. ultimum (F). Stereomicroscopic image of corn roots infected with G. ultimum var. ultimum in ½ MS medium (G).

Effects of Pythium s.l. infection on expression levels of main defense-related phytohormone marker genes in corn roots at 7 days past infection quantified by RT-qPCR. PR1 for salicylic acid (SA), PDF1.2 for jasmonate (JA), ETR2 for ethylen (ET) and NCED3 for abscisic acid (ABA). Relative expression (log2) of each marker gene was displayed (non-infected control (NC), G. attrantheridium and G. ultimum var. ultimum). Statistical differences were tested two-sided by a multiple contrast test for ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 (degrees of freedom = 24). Error bars indicate the standard deviation (n = 3).

Discussion

NGS-based identification of Pythium s.l. in Europe

A total of 73 Pythium s.l. including 3 Phytopythium, 30 Pythium s.s. and 40 Globisporangium species, were detected in 127 soil samples. Except for two sample sites (P20_L07 and P20_L37), Pythium s.l. was detected at every sampled site in this study. Although the number of species in individual soil samples varied considerably, up to 20 species were found at one sampling site. This is in line with the report3 that 11 Pythium s.l. species were detected from 42 production fields in Ohio and 27 Pythium s.l. species from 12 sample sites using ITS primers UN-UP18S42 and UNLO28S2239. Similarly, 51 Pythium s.l. species were identified from 64 fields in 2011 and 54 from 61 fields in 2012 from soybean roots by Sanger sequencing-based indentification40. A high number of different Pythium s.l. species from 11 sampling sites in Michigan, USA, were detected by sequencing the cox1 oomycete region41. The higher number of different Pythium s.l. species in our study could reflect that the samples were taken from sites that differ greatly from each other in terms of climatic conditions and agronomic cultivation parameters. Compared with individual studies from the US, the diversity in Europe is even higher.

Taxonomic resolution depends on the used primers and the sequenced marker region. Application of Pythium s.l. specific primers greatly increased the efficiency and specificity of the ITS-PCR amplification as well as the taxonomic resolution of the data. The primers specifically amplified the ITS1 region of Pythium s.l. and reduced fungal amplicons. In addition to the ITS region, the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (CO1, COX1) is frequently used in many studies, as it allows the identification of a variety of species of eukaryotic organisms27,28. Both ITS and COX1 proved to be highly variable marker regions that distinguish Pythium s.l. species25. Both regions provide sufficiently high taxonomic resolution for oomycetes, even though both regions fail to detect some species due to barcoding gaps, thus arguing for the inclusion of the ITS region as an efficient barcode for oomycetes identification25,29.

The cultivation of single species on selective media allows for the generation of individual isolates, which can be used directly for infection experiments and molecular characterization, e.g., by sequencing. However, the selective effects of the medium may influence individual species to a varying degree, causing unequal selection pressure to Pythium s.l. as confirmed by ref. 42. A comparison of the soil and bait samples indicates that the selective medium has a certain effect on the genus Pythium s.l. Nevertheless, most of the dominant species from the soil samples were also detected as dominant in the bait samples. The selective medium is therefore very useful for detecting dominant species.

Co-occurrence analysis and linkage of Pythium s.l. with soil parameter

Assessing co-occurrence patterns of microbial communities provides a great opportunity to get insights into species-specific interactions, like antagonistic or supportive behavior. However, insights on a global scale are still less understood43. Despite no empirical evidence that can be inferred, co-occurrence networks still support the understanding of species-species interactions, like the ability to colonize specific ecological niches44. It is assumed that species that co-occurred often also interact with other taxa more frequently45 indicating overall importance in microbial communities. In our study, G. camurandrum showed the highest number of significant interactions with other species, while negative correlations are dominant (Fig. 7B). Interestingly, G. attrantheridium is classified as the most dominant in our study and shows a high degree of negative correlations, implying highly competitive behavior to gain an advantage in growth in the soil. Contrarily, P. heterothallicum, the second most abundant species, does show a high number of negative correlations but more significant correlations overall. G. attrantheridium is not classified as antagonistic against Pythium s.l., raising the question of how manifold the underlying mechanisms are between species.

To link soil properties and the abundance of Pythium s.l. The LUCAS topsoil dataset was used to calculate mean values of the included parameters of soil pH and soil organic content. Out of 73 species, only 3 were significantly correlated with soil pH or soil organic content, while 70 species showed no direct correlation, implying an overall balance of the communities across European soils with the ability to react to various soil46 conditions. This is contrary to previous findings47 on a large scale, soil pH was the most important bacterial and fungal beta-diversity driver. This discrepancy may reflect the structural stability of Pythium s.l. communities in adaptation to various environments.

High species diversity of Pythium s.l. communities in Europe

In this study, we identified a set of ten Pythium s.l. species representing the most common and abundant species in Europe. In contrast to a study in Ohio, where P. dissotocum and G. sylvaticum were the predominant species3, P. dissotocum was not found in Europe, while G. sylvaticum was very common. Interestingly, in addition to P. aff. dissotocum and G. sylvaticum, G. ultimum var. ultimum, G. heterothallicum, G. attrantheridium and G. sylvaticum were found to be predominant in most soil samples from north America48. The discrepancy of varying occurrences of predominant species in different studies may be due to different geographic preconditions and agricultural practices.

Investigations on Pythium s.l. diversity of infected soybean roots in the US in 2011 and 2012 showed that in 2011 G. sylvaticum, G. heterothallicum, G. ultimum var. ultimum and G. attrantheridium were among the 12 most frequently detected species, while in 2012 in addition G. intermedium and G. rostratifingens were also dominant48. Noticeably, four species from 2011 and six from 2012 belong to the ten most frequently detected species in our study, thus strongly suggesting that these species dominate Pythium s.l. communities on a global scale. However, our study’s relative abundance of G. sylvaticum was significantly higher in 2020 than in the other two years. As no significant year-to-year difference in the abundance for G. attrantheridium, G. heterothallicum, G. apiculatum, G. rostratifingens, P. aff. hydnosporum, P. intermedium, P. arrhenomanes and G. ultimum var. ultimum was observed, G. sylvaticum appeared significantly more abundant in 2020. In addition, P. monospermum was also detected at many sites in this study, while the relative abundance of P. monospermum was higher in 2019 than in the other two years.

Compared to the mean value of all countries, we found only minor differences in the occurrence of the dominant Pythium s.l. species among countries. The average temperatures around sowing time (March to May) vary significantly when comparing countries. Nevertheless, a significantly higher relative abundance of G. ultimum var. ultimum was found in Belgium and statistic trend for the Netherlands. In contrast, significantly more G. heterothallicum was detected in France and Romania, while P. monospermum was significantly more common in Italy. However, it remains open why these differences persist between these countries. A possible scenario could be that the soil samples used in this study tend to represent more of a natural, steady state of Pythium s.l. communities that have not yet been sharpened by infection pressure. This also explains discrepancies between our data and other studies, mainly focusing on infected roots. It’s very likely that the cropping systems of these two countries, which are characterized by a high percentage of vegetables and different crop rotations, for example, could influence the higher G. ultimum var. ultimum abundance.

Nevertheless, our data show an even distribution of predominant Pythium s.l. species in Europe, regardless of their geographic location and agricultural history, implying a high infection potential of Pythium s.l. in Europe. Differences were only observed for soil texture classes. Likewise, the variation of inoculum density in heavy soils is lower than medium and light soils. In general, it should be noted that these soils not only differ in their clay content but are also subject to different cultivation systems due to their characteristics. The reduced tillage, as well as closer crop rotations, could affect soil pathogens by reducing the inoculum of soil-borne pathogens through plowing49,50. Another factor could be soil temperature, as lighter soils warm up faster in spring than heavier soils, and the pathogenicity of species is temperature-dependent48,51,52 and thus can also critically affect inoculum density. Interestingly, soil texture class has an impact on species diversity. For medium soils, diversity tends to be higher compared to the mean of all soil texture classes. This is most likely influenced by the microbial activity of the soil. The presence and activity of certain bacterial and fungal taxa, as well as the activity of specific enzymes or individual compounds, have an impact on pathogens53.

Predominant Pythium s.l. is represented by a large number of ASVs

A high number of ASVs within a given species supports the species diversity of Pythium s.l. communities in Europe. In particular, P. aff. hydnosporum, G. attrantheridium, G. rostratifingens, P. sp. nov, G. sylvaticum, and G. ultimum var. ultimum were found to have many different ASVs in 2020. Most likely, these differences can be explained by overriding influencing factors such as weather, supported by the European weather data54.

Although our data do not allow us to conclusively identify the main factor for the different ASVs of the various species, however, soil moisture seems to play a critical role in this process as a prerequisite for zoospore movement in the soil, as initially described by ref. 55. But, based on the biology of Pythium s.l. the presence of a host plant is required, as soil moisture is mainly relevant to the initial infection. Thus, a future long-term survey monitoring of the same locations and sampling time points may shed more light on the driving force of Pythium s.l. community structure across Europe. Strikingly, certain ASVs were detected more frequently within a predominant species than others, implying their relevance in terms of disease potential. We characterized them by comparing the absolute abundance found at specific locations with the occurrence at all locations. The ASVs most frequently detected within the corresponding species were also most frequently detected at the different sites. Noticeably, this is the case for P. aff. hydnosporum, G. apiculatum, G. attrantheridium, G. intermedium, G. rostratifingens, G. sylvaticum and G. ultimum var. ultimum. All of them are primarily represented by a single characteristic ASV. Partially, this is also found for G. heterothallicum, where the number of detections was higher at different sites for ASV_10, although ASV_6 was most abundant in absolute terms for G. heterothallicum. It is noteworthy that individual ASVs of certain species occur at a particularly high number of sites, while for other species, distribution is characterized by multiple ASVs. This suggests varying genetic diversities among the different species. The importance of an ASV depends not only on its frequency at different locations but also on its adaptability to a changing environment and agricultural systems. It is generally accepted that the dominance of single genotypes, represented in our study by ASVs, has a selective advantage within a genus, for example, by increasing their pathogenicity and virulence on their hosts.

Pythium s.l. harbors a high disease potential in Europe

We tested G. attrantheridium and G. ultimum var. ultimum, isolated from this study, in an in vitro-infection experiment for their disease potential in corn. Consistent with previous reports42,56, both species were pathogenic and capable of infecting corn but differed significantly in symptoms and disease progression. The infection of G. ultimum var. ultimum resulted in much more pronounced disease symptoms and severity on corn roots, causing a significant reduction in germination rate, shoot fresh weight, and root dry weight. Interestingly, although G. attrantheridium was the most frequently detected species in this study, the infection with G. attrantheridium induced considerably fewer disease symptoms on corn roots and, consequently, a lower-level reduction of shoot fresh weight and root dry weight as well as germination rate than infection with G. ultimum var. ultimum. These results underline the complexity and importance of corn-Pythium interactions on the disease potential of individual species. Due to climate change, it can be assumed that the distribution and relative abundance of soil-borne pathogens such as Pythium s.l. will increase, with implications for food security worldwide57. Thus, the distribution, abundance, and pathogenic potential of individual Pythium s.l. should be considered as the main factors determining Pythium-disease potential.

So far, little is known about molecular events in plant response to Pythium s.l. Our analyzes highlight transcriptional changes of plant hormone marker genes in response to Pythium s.l. infection. Both G. ultimum var. ultimum and G. attrantheridium infections extremely upregulated the expression of PR1 (SA) while down-regulated PDF1.2 (JA) suggesting enhanced SA- but suppressed JA-signaling pathways. Generally, SA activates resistance against biotrophic pathogens, while JA is critical for activating defenses against necrotrophic pathogens35. SA- and JA-mediated signaling functions are antagonistic and often exploited by pathogens to promote their virulence36. As shown in tomato, Botrytis cinerea activated SA signaling to suppress JA signaling escaping from the JA-mediated defense responses58. JA deficiency in corn and Arabidopsis led to an extreme susceptibility to Pythium s.l.37,59,60,61. It is worth mentioning that the change in transcript levels of PR1 and PDF1.2 in response to both Pythium s.l. infection appeared to correlate with the disease severity observed in this study. Thus, it seems reasonable to conclude that species like G. ultimum var. ultimum, have evolved an effective virulence strategy to overcome JA-mediated plant defense response by interfering with plant hormone-signaling networks. Further studies are needed to identify the relevant effectors and underlying molecular events that can contribute to a better understanding of the interactions between corn and Pythium s.l. and develop new effective control strategies against this pathogen.

Methods

Geographic distribution of sampling locations and sampling procedures

For three consecutive years (2019–2021), soil and bait samples were collected from conventionally farmed agricultural fields. A total of 127 sites were sampled in France, Italy, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Spain, Romania, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Switzerland and Austria. Soil samples were collected four weeks after corn seeding. For each site, eight 50 ml soil samples were taken by pressing the 50 mL falcons (Sarstedt, Nürnbrecht, Germany) into the soil with the opening facing downwards. Soil samples were stored at −20 °C. For bait sampling and species cultivation, Benomyl-Ampicillin-Rifampicin-Pentachlornitrobenzol was (Table S1, Supplementary Information) filled into 15 mL centrifuge tubes (Sarstedt, Nürnbrecht, Germany). After solidification of the medium, 1 mm holes were punctured into the tubes using a hot needle. Eight baits were placed in the soil of a sampling site on the day of seeding. Before inserting the tube into the soil, a hole was drilled with an empty tube with 15 cm apart from the corn row. After four weeks, the baits were collected and stored at 4 °C until further processing. The samples were sent refrigerated by express shipping. All used chemicals, materials and kits in this study are provided separately in a file in the appendix (see Supplementary Data 1). An overview of sampling sites is provided in Table S2.

Isolation of genomic DNA (gDNA) from soil samples

For gDNA isolation from soil, a pooled 5 g sample was used, by mixing the 8 individual samples of one site. For bait samples, 10 ml of eight individual samples of the selective medium were mixed per site. DNA Isolation was performed using a modified CTAB as described by ref. 62 (Table S3). The isolated gDNA was purified using the “NucleoSpin Gel and PCR Clean-up Kit” (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The integrity and quality of the purified DNA were determined by agarose gel electrophoresis, and the DNA concentration was measured semi-quantitatively using lambda DNA of known concentration (10 ng/µL) with ImageLab software (version 4, Bio-Rad Laboratories). Finally, gDNA was stored at −20 °C until further processing.

DNA library preparation for NGS sequencing

DNA library preparation and NGS sequencing were conducted by Planton GmbH (Kiel, Germany). Briefly, the diverse ITS region among oomycetes25,63,64 was used. For this study, the ITS1 region was amplified using the primer pair pyth_f (5ʹ−3ʹ; TGCGGAAGGATCATTACCACAC) and pyth_r2 (5ʹ−3ʹ; GCGTTCAAAATTTCGATGACTC), which were specifically designed by generating a multiple sequence alignment of available ITS sequences (NCBI database). Fungal sequences were included to focus on regions offering high dissimilarity. Further, primer specificity and efficiency were finetuned by qPCR with Pythium s.l. isolates. PCR was performed using “High Fidelity Platinum SuperFi II PCR Master Mix” (Thermo Fisher, Massachusetts, USA). The DNA quantity and quality were measured by photometric measurement using the “Thermo Scientific Multiskan GO” (Thermo Fisher, Massachusetts, USA) and determined by real-time (SYBR Green) monitored PCR. PCR products were purified using the “NucleoSpin Gel and PCR Clean-up Kit” (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). DNA libraries were generated using the “NEB Next Ultra II Q5 Kit” (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, USA) and subsequently sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq (Illumina, San Diego, USA) platform, resulting in 250 bp paired-end reads.

Bioinformatic analysis

The resulting paired-end reads were demultiplexed based on their barcodes and primer sequences were trimmed using Cutadapt40. The length of the filtered reads was truncated to 200 bp. Sequencing quality was checked using FastQC41 and further visually inspected using MultiQC65. The remaining reads were analyzed according to the DADA266 pipeline including the steps: quality filtering and trimming, learning error rates, identifying sample inference, merging paired-end reads, constructing sequence table, and removing of chimeras. Taxonomic annotation of identified amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) was performed running Blast locally in megablast mode67. ASVs were aligned to a curated oomycete ITS database25 using the best bit score and an identity of higher than 95%. Sequences assigned to Pythium sp. nov. are a new unknown species in the biological taxonomy. Accordingly, all unknown species were merged under P. sp. nov. Further, the taxonomically assigned species were annotated to the current genus and clade68. The R package “phyloseq” v1.47.069 and R (4.4.0)46 were used for further analysis.

Linkage analysis between soil properties and the co-occurrence of Pythium s.l

The linkage between soil properties and the co-occurrence of Pythium spp. s.l. was analyzed using the harmonized open-access topsoil dataset, LUCAS70. The European Commission made the dataset available through the European Soil Data Centre and managed by the Joint Research Centre (JRC, http://esdac.jrc.ec.europa.eu/). Based on the locations of our samples, we selected the 5 closest sites from the LUCAS dataset and calculated the mean values of respective soil properties (pH, OC). After merging Pythium s.l. species diversity and soil properties, Pearson correlations (two-sided) for each species were calculated based on relative abundance. To determine the co-occurrence patterns of all species in soil, the software FastSpar71,72 was applied using a generated count matrix and taxonomy annotation as input. First, correlation and covariance measures were calculated using 100 iterations, followed by the calculation of exact p-values using 10,000 bootstraps.

Isolation, cultivation, and characterization of Pythium s.l

For isolation of single Pythium s.l. species, a piece of selective BARP medium from a single bait was transferred to a Petri dish containing BARP medium. A single hypha was excised under a binocular microscope and transferred onto a fresh BARP medium. This process of hypha excision was repeated five times to ensure isolation. Genomic DNA isolation was carried out using the CTAB method (Table S4). The ITS region was amplified by PCR using the primer pyth_f and pyth_r2. The PCR Amplicon was cloned into the pGEM®-T vector (Promega, Fitchburg, United States) for Sanger sequencing73 (Eurofins Genomics GmbH, Ebersberg, Germany).

Infection experiments on corn

Pythium s.l. isolates were cultured on BARP medium at 25 °C for 5 days and stored at 4 °C. Before the infection experiments, freshly grown mycelial plugs of each isolate were transferred to PDA medium and cultivated for 5 days at 25 °C. For each inoculum, 250 g of millet (Bio Gold Hirse, Rewe, Germany) was autoclaved in an Erlenmeyer flask, and then 125 ml of sterile deionized water and thirty plugs (5 mm diameter) of Pythium s.l. were added, in which plugs of pure PDA medium served as the non-inoculated control. The Pythium-millet suspension was incubated in the dark at 25 °C for 5 days. The soil for the infection experiments was a mixture of unit soil (Einheitserdewerk ED73, Uetersen, Germany) and sand (Kinderspielsand, Bauhaus, Germany) in a weight ratio of 60 to 40. The Pythium-millet suspension was added to the soil and homogenized. Corn seeds (Benedictio, KWS) were sterilized in 5 % sodium hypochlorite (3 min) followed by 10 % ethanol (1 min). In each pot (9 × 9 cm), 3 corn seeds were planted (3 cm depth) in the inoculated soil. The plants were cultivated for 4 weeks under greenhouse conditions (with a simulated day length of 16 h and temperatures of 20 °C during the day and 18 °C at night. Plants were continuously watered. Shoot fresh and root dry weight (at 65 °C for 2 days) were determined. To visualize the infection of corn roots with species of Pythium s.l., sterile glass tubes with open ends (30 cm height × 3 cm diameter) were used, which could be sealed with silicone plugs. Glass tubes were filled with 50 mL of 1/2 MS medium. Sterilized corn seeds were pre-germinated on 1/2 MS medium for 3 days and transferred to the top surface of the MS medium inside glass tubes. Corn seeds were grown for 4 days under short-day conditions (8 h light, 25 °C), and then 2.5 cm diameter mycelial plugs were placed on the bottom side of the MS medium facing towards the roots. The section of the glass tubes containing MS medium was protected from light by covering it with aluminum foil. Seven days post-infection (dpi), the aluminum foil was removed, and photos of the roots were taken with a microscope (ZEISS SteREO Discovery.V20, Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

Gene expression analysis by RT-qPCR

Corn was cultivated on 1/2 MS medium under short-day conditions (8 h, 25 °C). Mycelial plugs of the isolates G. ultimum var. ultimum and G. attrantheridium were placed adjacent to the roots for infection. Seven days past infection (7 dpi), the roots were harvested. Total RNA from roots of corn was extracted by TRIzol® (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A total of 1 µg RNA was treated with RNase-free DNase I (Fermentas, Massachusetts, USA) and further transcribed in a volume of 20 µl with the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) into first strand cDNA according to supplier’s instructions. 2 µl of a 1:10 diluted cDNA preparation was mixed with an 18 µl master mix as described in the manual of the Maxima SYBR Green/ROX qPCR Master Mix (Thermo Scientific, Massachusetts, USA). RT-qPCR was performed on a CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA) using the following conditions: 3 min 95 °C; 45 × 10 sec 95 °C, 10 sec 59 °C, 10 sec 72 °C; 10 sec 95 °C, melting curve from 65 °C to 95 °C. Primers used are listed in Table S5. The gene expression level was determined using the delta CT Method74 and calculated in relation to the reference gene actin that is stably expressed independent of Pythium s.l. infection. The resulting CT values were normalized by primer efficiency. Each measurement consists of three independent biological replicates incorporating three technical replicates each. The relative expression was log2 transformed, and the induction was calculated as the difference between Pythium s.l. and mock-treated samples.

Statistical analysis

The statistical software R (4.4.0)46 was used to evaluate the survey data, and infection- and gene expression trials. The data evaluation started with the definition of an appropriate statistical model75 with the factors “Year,” “Country,” and “Soil texture class.” A model comparison (main effects model vs. pseudo factor model) proved the interaction effect. The residuals were assumed to be approximately normally distributed and heteroscedastic. For the measurement variable germination rate, the data evaluation started with the definition of a Bayesian generalized linear model76. A usual linear model was used for the measurement variables shoot fresh- and root-dry weight per plant. These models included the factor “Species”. The residuals followed a binomial distribution for germination rate and a normal distribution for shoot fresh- and root dry weight per plant. The normal distributions of the data evaluations were checked by a graphical residual analysis. For the log-values of the relative gene expression, a statistical model based on generalized least squares77 was used. The model included the factors “Species” and “Gene” and the interaction term. The residuals were assumed to be approximately normally distributed and homoscedastic. Based on all these models, an analysis of variances (ANOVA) was conducted, followed by multiple contrast tests78,79 as well as a pseudo R2 was calculated80 for gene expression (see Supplementary Data 2).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The raw sequencing data generated in this study have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession code PRJNA1008090. Data belonging to the infection experiment (germination rate, shoot fresh weight, root dry weight and gene expression levels) are available in GitHub: https://github.com/Wilken-Christian-Boie/An-assessment-of-the-species-diversity-and-disease-potential-of-Pythium-communities-in-Europe. The LUCAS topsoil 2018 dataset is freely available and can be downloaded after prior registration at the General-Joint Research Centre (JRC) of the European Commission: https://esdac.jrc.ec.europa.eu/content/lucas-2018-topsoil-data.

Code availability

All code and source data files are available in GitHub: https://github.com/Wilken-Christian-Boie/An-assessment-of-the-species-diversity-and-disease-potential-of-Pythium-communities-in-Europe.

References

Rossman, D. R. et al. Pathogenicity and virulence of soilborne oomycetes on Phaseolus vulgaris. Plant Dis. 101, 1851–1859 (2017).

Schroeder, K. L. et al. Molecular detection and quantification of pythium species. evolving taxonomy, new tools, and challenges. Plant Dis. 97, 4–20 (2013).

Broders, K. D., Lipps, P. E., Paul, P. A. & Dorrance, A. E. Characterization of Pythium spp. associated with corn and soybean seed and seedling disease in Ohio. Plant Dis. 91, 727–735 (2007).

Matthiesen, R. L., Ahmad, A. A. & Robertson, A. E. Temperature affects aggressiveness and fungicide sensitivity of four Pythium spp. that cause soybean and corn damping off in Iowa. Plant Dis. 100, 583–591 (2016).

Bickel, J. T. & Koehler, A. M. Review of Pythium species causing damping-off in corn. Plant Health Prog. 22, 219–225 (2021).

Lévesque, C. A. et al. Genome sequence of the necrotrophic plant pathogen Pythium ultimum reveals original pathogenicity mechanisms and effector repertoire. Genome Biol. 11, R73 (2010).

Uzuhashi, S., Kakishima, M. & Tojo, M. Phylogeny of the genus Pythium and description of new genera. Mycoscience 51, 337–365 (2010).

McKellar, M. E. & Nelson, E. B. Compost-induced suppression of Pythium damping-off is mediated by fatty-acid-metabolizing seed-colonizing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 452–460 (2003).

Mueller, D. S. et al. Corn yield loss estimates due to diseases in the United States and Ontario, Canada from 2012 to 2015. Plant Health Prog. 17, 211–222 (2016).

van Buyten, E., Banaay, C. G. B., Vera Cruz, C. & Höfte, M. Identity and variability of Pythium species associated with yield decline in aerobic rice cultivation in the Philippines. Plant Pathol. 62, 139–153 (2013).

Rai, M. et al. Effective management of soft rot of ginger caused by Pythium spp. and Fusarium spp. Emerging role of nanotechnology. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 102, 6827–6839 (2018).

Rai, M., Abd-Elsalam, K. & Ingle, A. P. (eds.). Pythium. Diagnosis, diseases and management (CRC Press, Boca Raton FL, 2020).

Dodd, J. L. & and White, D. G. Seed rot, seedling blight, and damping-off. In Compendium of Corn Diseases. American Phytopathological Society (1999).

Kirk, P. M., Cannon, P. F., David, J. C. & Stalpers, J. A. Ainsworth and Bisby’s dictionary of the fungi (CABI, 2008).

DMK. EU-Anbauflächen Körnermais. (inkl. CCM) in 1.000 ha, 2017 bis 2021. Available at https://www.maiskomitee.de/Fakten/Statistik/Europ%C3%A4ische_Union (2023).

Chamswarng, C. Identification and comparative pathogenicity of Pythium species from wheat roots and wheat-field soils in the Pacific Northwest. Phytopathology 75, 821 (1985).

Deep, I. W. & Lipps, P. E. Recovery of Pythium arrhenomanes and its virulence to corn. Crop Prot. 15, 85–90 (1996).

Ingram, D. M. & Cook, R. J. Pathogenicity of four Pythium species to wheat, barley, peas and lentils. Plant Pathol. 39, 110–117 (1990).

Schmidt, C. S. et al. Pathogenicity of Pythium species to maize. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 158, 335–347 (2020).

Bachy, C., Dolan, J. R., López-García, P., Deschamps, P. & Moreira, D. Accuracy of protist diversity assessments. Morphology compared with cloning and direct pyrosequencing of 18S rRNA genes and ITS regions using the conspicuous tintinnid ciliates as a case study. ISME J. 7, 244–255 (2013).

Bengtsson-Palme, J. et al. Improved software detection and extraction of ITS1 and ITS2 from ribosomal ITS sequences of fungi and other eukaryotes for analysis of environmental sequencing data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 25, n/a-n/a (2013).

Findley, K. et al. Topographic diversity of fungal and bacterial communities in human skin. Nature 498, 367–370 (2013).

Luo, C., Tsementzi, D., Kyrpides, N., Read, T. & Konstantinidis, K. T. Direct comparisons of Illumina vs. Roche 454 sequencing technologies on the same microbial community DNA sample. PloS one 7, e30087 (2012).

Rai, M. K., Tiwari, V. V., Irinyi, L. & Kövics, G. J. Advances in taxonomy of genus phoma. Polyphyletic nature and role of phenotypic traits and molecular systematics. Indian J. Microbiol. 54, 123–128 (2014).

Robideau, G. P. et al. DNA barcoding of oomycetes with cytochrome c oxidase subunit I and internal transcribed spacer. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 11, 1002–1011 (2011).

Salmaninezhad, F. & Mostowfizadeh-Ghalamfarsa, R. Three new Pythium species from rice paddy fields. Mycologia 111, 274–290 (2019).

Hajibabaei, M., Janzen, D. H., Burns, J. M., Hallwachs, W. & Hebert, P. D. N. DNA barcodes distinguish species of tropical Lepidoptera. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. Usa. 103, 968–971 (2006).

Seifert, K. A. et al. Prospects for fungus identification using CO1 DNA barcodes, with Penicillium as a test case. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. Usa. 104, 3901–3906 (2007).

Bala, K., Robideau, G. P., Désaulniers, N., Cock, A. W. A. Mde & Lévesque, C. A. Taxonomy, DNA barcoding and phylogeny of three new species of Pythium from Canada. Persoonia 25, 22–31 (2010).

Lévesque, C. A., Cock, A. W. A. M. & de Molecular phylogeny and taxonomy of the genus Pythium. Mycological Res. 108, 1363–1383 (2004).

Duan, C. et al. Characterization and molecular mapping of two novel genes resistant to Pythium stalk rot in maize. Phytopathology 109, 804–809 (2019).

Song, F.-J. et al. Two genes conferring resistance to Pythium stalk rot in maize inbred line Qi319. Mol. Genet. genomics: MGG 290, 1543–1549 (2015).

Hou, M. et al. Genome-wide association study of maize resistance to Pythium aristosporum stalk rot. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 521 (2023).

White, D. G. (ed.). Compendium of Corn Diseases. 3rd ed. (APS Pr, St. Paul, 1999).

Li, N., Han, X., Feng, D., Yuan, D. & Huang, L.-J. Signaling crosstalk between salicylic acid and ethylene/jasmonate in plant defense. do we understand what they are whispering? IJMS 20, 671 (2019).

Liu, L. et al. Salicylic acid receptors activate jasmonic acid signalling through a non-canonical pathway to promote effector-triggered immunity. Nat. Commun. 7, 1583 (2016).

Yan, Y. et al. Disruption of OPR7 and OPR8 reveals the versatile functions of jasmonic acid in maize development and defense. Plant Cell 24, 1420–1436 (2012).

Zhu, Y. et al. Laccase directed lignification is one of the major processes associated with the defense response against Pythium ultimum infection in apple roots. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 130 (2021).

Jiang, Y. N., Haudenshield, J. S. & Hartman, G. L. Characterization of Pythium spp. from soil samples in Illinois. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 34, 448–454 (2012).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet j. 17, 10 (2011).

Andrews, S. FastQC. A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. Version 0.11.9 (2010).

Rojas, J. A., Witte, A., Noel, Z. A., Jacobs, J. L. & Chilvers, M. I. Diversity and characterization of oomycetes associated with corn seedlings in Michigan. Phytobiomes J. 3, 224–234 (2019).

Ma, B. et al. Earth microbial co-occurrence network reveals interconnection pattern across microbiomes. Microbiome 8, 82 (2020).

Yang, Y., Shi, Y., Fang, J., Chu, H. & Adams, J. M. Soil Microbial Network Complexity Varies With pH as a Continuum, Not a Threshold, Across the North China Plain. Frontiers in microbiology 13 (2022).

van der Heijden, M. G. A. & Hartmann, M. Networking in the plant microbiome. PLoS Biol. 14, e1002378 (2016).

R Core Team. R Core Team. A language and environment for statistical computing: reference index (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, [Vienna], 2023).

Labouyrie, M. et al. Patterns in soil microbial diversity across Europe. Nat. Commun. 14, 3311 (2023).

Rojas, J. A. et al. Oomycete species associated with soybean seedlings in North America-Part I. identification and pathogenicity characterization. Phytopathology 107, 280–292 (2017).

Feng, H. et al. Pathogenicity and fungicide sensitivity of Pythium and Phytopythium spp. associated with soybean in the Huang‐Huai region of China. Plant Pathol. 69, 1083–1092 (2020).

Paulitz, T. C., Schroeder, K. L. & Schillinger, W. F. Soilborne pathogens of cereals in an irrigated cropping system. effects of tillage, residue management, and crop rotation. Plant Dis. 94, 61–68 (2010).

Molin, C. et al. Damping‐off of soybean in southern Brazil can be associated with different species of Globisporangium spp. and Pythium spp. Plant Pathol. 70, 1686–1694 (2021).

Rojas, J. A. et al. Oomycete species associated with soybean seedlings in North America—Part II. diversity and ecology in relation to environmental and edaphic factors. Phytopathology® 107, 293–304 (2017).

Bongiorno, G. et al. Soil suppressiveness to Pythium ultimum in ten European long-term field experiments and its relation with soil parameters. Soil Biol. Biochem. 133, 174–187 (2019).

DWD. Deutscher Wetterdienst; RCC-CM (WMO RA-VI). Wetter und Klima aus einer Hand. Climate & environment. Available at https://www.dwd.de/EN/ourservices/rcccm/int/rcccm_int_ttt.html?nn=519122 (2023).

Kerr, A. The influence of soil moisture on infection of peas by Pythium Ultimum. Aust. Jnl. Bio. Sci. 17, 676 (1964).

Zhang, B. Q. & Yang, X. B. Pathogenicity of Pythium populations from corn-soybean rotation fields. Plant Dis. 84, 94–99 (2000).

Singh, B. K. et al. Climate change impacts on plant pathogens, food security and paths forward. Nature reviews. Microbiology, 1–17; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-023-00900-7 (2023).

El Oirdi, M. et al. Botrytis cinerea manipulates the antagonistic effects between immune pathways to promote disease development in tomato. Plant Cell 23, 2405–2421 (2011).

Staswick, P. E., Yuen, G. Y. & Lehman, C. C. Jasmonate signaling mutants of Arabidopsis are susceptible to the soil fungus Pythium irregulare. Plant J.: cell Mol. Biol. 15, 747–754 (1998).

van Baarlen, P., Woltering, E. J., Staats, M. & van Kan, J. A. L. Histochemical and genetic analysis of host and non-host interactions of Arabidopsis with three Botrytis species. An important role for cell death control. Mol. plant Pathol. 8, 41–54 (2007).

Vijayan, P., Shockey, J., Lévesque, C. A., Cook, R. J. & Browse, J. A role for jasmonate in pathogen defense of Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. Usa. 95, 7209–7214 (1998).

Rogers, S. O. & Bendich, A. J. Extraction of DNA from milligram amounts of fresh, herbarium and mummified plant tissues. Plant Mol. Biol. 5, 69–76 (1985).

Hershkovitz, M. A. & Lewis, L. A. Deep-level diagnostic value of the rDNA-ITS region. Mol. Biol. evolution 13, 1276–1295 (1996).

Wielgoss, A. M. Dynamik der schilfassoziierten Oomycetengemeinschaft im Litoral des Bodensees unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des Schilfpathogens Pythium phragmitis (2009).

Ewels, P., Magnusson, M., Lundin, S. & Käller, M. MultiQC. summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinforma. (Oxf., Engl.) 32, 3047–3048 (2016).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2. High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. methods 13, 581–583 (2016).

Morgulis, A. et al. Database indexing for production MegaBLAST searches. Bioinforma. (Oxf., Engl.) 24, 1757–1764 (2008).

Nguyen, H. D. T. et al. Whole genome sequencing and phylogenomic analysis show support for the splitting of genus Pythium. Mycologia 114, 501–515 (2022).

McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. Phyloseq. an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PloS one 8, e61217 (2013).

Orgiazzi, A., Ballabio, C., Panagos, P., Jones, A. & Fernández‐Ugalde, O. LUCAS Soil, the largest expandable soil dataset for Europe. A review. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 69, 140–153 (2018).

Friedman, J., Alm, E. J. & Mering, C. Inferring correlation networks from genomic survey data. PLoS Comput Biol. 8, e1002687 (2012).

Watts, S. C., Ritchie, S. C., Inouye, M., Holt, K. E. & Stegle, O. FastSpar. rapid and scalable correlation estimation for compositional data. Bioinformatics 35, 1064–1066 (2019).

Sanger, F. et al. Nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage phi X174 DNA. Nature 265, 687–695 (1977).

Pfaffl, M. W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic acids Res. 29, e45 (2001).

Carroll, R. J. & Ruppert, D. Transformation and Weighting in Regression. 1st ed. (CRC Press, London, 1988).

Gelman, A., Jakulin, A., Pittau, M. G. & Su, Y.-S. A weakly informative default prior distribution for logistic and other regression models. Ann. Appl. Stat. 2; https://doi.org/10.1214/08-AOAS191 (2008).

Box, G. E. P., Jenkins, G. M. & Reinsel, G. C. Time series analysis. Forecasting and control. 3rd ed. (Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1994).

Bretz, F., Hothorn, T. & Westfall, P. H. Multiple comparisons using R (Chapman & Hall/CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla., 2011).

Hothorn, T., Bretz, F. & Westfall, P. Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biom. J. 50, 346–363 (2008).

Nakagawa, S., Schielzeth, H. & O’Hara, R. B. A general and simple method for obtaining Rfrom generalized linear mixed-effects models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 4, 133–142 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank Bettina Bastian for preparing the sampling material and Sören Schneider for DNA isolation. We thank Syngenta staff and farmers for soil sampling and the Institute of Phytopathology at Kiel University for providing PhD scholarship to Wilken Boie. This project was financially supported by Syngenta Crop Protection AG, the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, Germany (Grant no. 031B0910-A), and the Fachagentur für Nachwachsende Rohstoffe. Germany (Grant no. 221NR-058B).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.B. Performed experiments, data generation, and analysis and wrote the first draft of the paper. M.S. conducted data processing and bioinformatic analysis. W.Y. Performed infection experiments and molecular analysis. M.H. supported for statistical analysis. M.G. developed and supervised the project. JV: developed and supervised the project, and D.C.: designed and supervised experiments and finalized the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Kirk Broders and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Boie, W., Schemmel, M., Ye, W. et al. An assessment of the species diversity and disease potential of Pythium communities in Europe. Nat Commun 15, 8369 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52761-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52761-0

This article is cited by

-

A comparative study: impact of chemical and biological fungicides on soil bacterial communities

Environmental Microbiome (2025)