Abstract

The aqueous interface-rich system has been proposed to act as a trigger and a reservoir for reactive radicals, playing a crucial role in chemical reactions. Although much is known about the redox reactivity of water microdroplets at “droplets-in-gas” interfaces, it remains poorly understood for “bubbles-in-water” interfaces that are created by feeding gas through the porous membrane of the gas diffusion electrode. Here we reveal the spontaneous generation of highly reactive redox radical species detected by using electron paramagnetic resonance under such conditions without applying any bias and loading any catalysts. In combination with ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy, the redox feature has been further verified through several probe molecules. Unexpectedly, introducing crown ether allows to isolate and stabilize both water radical cations and hydrated electrons thus substantially increasing redox reactivity. Our finding suggests a reactive microenvironment at the interface of the gas diffusion electrode owing to the coexistence of oxidative and reductive species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

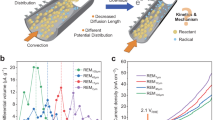

Chemical reactions at gas/water interfaces can be dramatically accelerated relative to the same processes that occurred in the gas phase or bulk water1,2. This intriguing phenomenon is known as “on-water catalysis”3. Indeed, spraying bulk water into microdroplets brings about an aqueous interface-rich system (“droplets-in-gas” in Fig. 1a), where the chemical reaction has been accelerated by 2 to 6 orders of magnitude4, owing to the mass accumulation5, high electric field (~109 V/m)6,7,8 and the resultant presence of highly reactive redox species(i.e., H2O•+/H2O•– and their derivatives)9,10. Since the intriguing finding of spontaneous generation of hydrogen peroxide from aqueous microdroplets11, the interfacial reactivity of water microdroplets inspires the exploitation of chemical conversion reactions by efficiently utilizing the redox radical species derived from water9. The redox condition performing like an electrochemical cell can be produced in situ via spraying mass spectrometry such as ammonia synthesis from nitrogen, urea synthesis from carbon dioxide and nitrogen, and methane oxidation to methane oxygenates12,13,14,15.

It is acknowledged that gas feeds through the porous membrane of the gas diffusion electrode (GDE) can also create gas/water interfaces16,17,18, where the transports of electrons, ions, and gas reactants can be substantially improved19,20, leading to enhanced reaction rates3,21. For example, a gateway for ion transport between oxygen bubble surfaces and supporting solids was reported recently22. Besides, gas cavities adhering to an electrode surface can initiate the oxidation of water-soluble species more effectively relative to the electrode areas free of bubbles23. Despite these advances24,25,26, the microenvironment at the GDE interface remains elusive and requires further in-depth exploitation.

Given that the continuous gas flow enables unhydrated gaseous molecules to produce gaseous bubbles near the GDE (“bubbles-in-water” in Fig.1b), it is urgent to determine whether the redox radicals could be triggered, forming a reactive interfacial microenvironment, like the interfaces of microdroplets2. However, since the spraying system itself can excite radicals through microdroplets10,27, mass spectrometry may not be suitable for the determination of radicals for “bubbles-in-water” systems. To solve this issue, recently, we developed a nontrapping chemical transformation pathway that allows for determining H2O•+ in water28.

In this contribution, we mimic the microenvironment of the GDE by applying a Janus hydrophobic/hydrophilic carbon paper (typical conducting substrate for GDEs without a catalyst layer) as a membrane for separating the gas and water flow channels. The water flow has been circulated through a peristaltic pump to accumulate the content of radicals in the presence of spin-trapping agents, such as 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO). Using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR), we find the spontaneous generation of redox radical species via gas feeds (Ar, or O2) without applying any bias to the GDE. Since water-derived H2O•+/H2O•– pair has been proposed as the primary species6,29, we show the concomitant formation of hydroxyl radical (•OH) via H2O•+ + H2O → •OH + H3O+ process30 and demonstrate the strong reduction ability of H2O•– species. Noteworthy, we further find that 18-crown-6 can efficiently stabilize H2O•+ and increase its reactivity owing to the complexation of 18-crown-6 with positively charged cations31. These results suggest a radical-induced reactive microenvironment at the interface of the GDE.

Results

Radical-induced redox properties of GDE microenvironments

To model the microenvironment of GDE while simplifying the interface at room temperature (Supplementary Fig. 1), a Janus hydrophobic/hydrophilic porous carbon paper has been prepared as a GDE by one-side hydrophilic treatment (Fig. 2a–c and Supplementary Movies 1, 2). The hydrophobic side ensures the gas flow while the hydrophilic side circulates water, leading to the formation of a large number of gas/water interfaces for gas transport and dissolution16. As shown in Fig. 2d, relative to the pure water before Ar feed, after feeding Ar, a large number of bubbles were generated and tracked by nanoparticle tracking analyzer (NTA) (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Movies 3, 4), the cumulative concentration of nanobubbles in different sizes is 5.7 × 107/mL, with a broad size distribution yet ~2 × 106/mL of nanobubbles centered at 175 nm (Fig. 2f). It was reported that ions such as hydrated protons/hydroxide (H+/OH–) and hydrated halide ions can be accommodated at the gas/water interfaces5,32,33. Meanwhile, the resultant hydrated electrons (e–aq), hydroxyl radicals (•OH), and water radical cation-anion pairs (H2O•+/H2O•–) preferentially bind to the water surface as well10,34,35. Thus, there seems to be a sort of affinity between ions and radicals. For example, Zhang and coworkers found that the H3O+ cations in water microdroplets can capture •OH radicals36. Recently, we demonstrated that alkali metal chlorides can stabilize hydrogen radicals (•H)37. It means that the gas/water interfaces for microdroplets act as a trigger and a reservoir for reactive radicals5. Could a similar phenomenon occur in the aqueous interface-rich system in GDEs?

a, b SEM images of the hydrophobic side. c Digital images of hydrophobic and hydrophilic surfaces upon dropping droplets. d NTA image of pure water before Ar feed. Size statistics are nugatory owing to too few nanobubbles. e NTA image of pure water after Ar feed. f Bubble concentration (106/mL) at different sizes. The cumulative concentration of nanobubbles is the sum of different-sized nanobubbles. The zeta potential ζ of nanobubbles is about −39.08 mV.

Using 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) as a highly efficient spin-trapping agent in water38, we applied EPR to track any possible radicals upon feeding different gases, consisting of Ar or O2, through GDE. Without gas feed, no EPR signals from radical adducts were detected, which was considered as the initial state. Upon gas feed, the gas flow rate of 40 mL/min was controlled by a gas flowmeter while water was circulated through the internal flow channel by a peristaltic pump, with a flow rate of 2 mL/min. After 20 min of operation, both DMPO-H2O+ (AN = 15.8 G, AHβ = 22.5 G)28 and DMPO-OH (AN = AHβ = 15 G)39 were detected regardless of gas type (Fig. 3). A slight increase in signal density was observed when the running time increased to 40 min and then tended to saturate. Similar to the O2/water interface with enhanced H2O2 yield for microdroplets, which was explained by one electron transfer for the formation of O2– intermediate40, here we exhibited that O2 feed also induces a little higher content of DMPO-H2O+ and much higher content of DMPO-OH (Fig. 3b). This seems to be caused by the consumption of counter-charged H2O•– (e–aq) species6. After 40 min of operation, the gas feed was stopped and left for 2 h. The increased content in DMPO-OH intensity should be mainly due to the proton transfer via H2O•+ + H2O → •OH + H3O+ process30. For comparison, if both sides of the carbon paper were hydrophobic, the EPR signal of DMPO-OH was still weak within 40 min (Supplementary Fig. 3). This may be due to the decreased gas/water interface.

It should be noted that the standard potential of the H2O•+/H2O couple is higher than 3 V and that of •OH/OH– is 1.9 V28,41. To further prove the existence of oxidative radicals, K2SO3 was added into the aqueous solution for the oxidation conversion from SO32– to SO3•– species42. As expected, DMPO-SO3– adduct (AN = 14.7 G, AH = 16.0 G) was detected, and its intensity increased with increasing the operating time (Fig. 4a). Predictably, this result can be a reference for the formation of SO3•– from soluble SO2/SO32– species at the air/water interfaces of aerosol microdroplets43,44. This is because the H2O•+ and/or •OH radicals can oxidize SO2/SO32– to SO3•– or SO42– species37. In addition, oxidative radical species can oxidize I– to I3•– and Fe(CN)64– to Fe(CN)63–, respectively. Both reactions can be tracked by ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy45,46,47. As shown in Fig. 4b, the continuous oxidation of I– to I3•– leads to the stepwise increase in absorbance, with increasing the feeding time. By using Fe(CN)64– and Fe(CN)63– as controls (Supplementary Fig. 4), gas-feeding aqueous solution in the presence of Fe(CN)64– causes the oxidation of Fe(CN)64– to Fe(CN)63– thus higher UV-Vis absorption intensity (Fig. 4c). In contrast, a strong reducing reagent, ascorbic acid (VC)39, was utilized to scavenge oxidative radicals leading to the decrease of oxidative radicals and the formation of ascorbyl radical (AH = 1.8 G) (Supplementary Fig. 5).

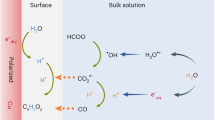

According to previous studies28,48, HCOO– can be oxidized to carbon dioxide anion radicals (CO2•−). When a low concentration of 0.1 M HCOOK was introduced, an overlay of radical signals can be detected (Fig. 5a), consisting of DMPO-H2O+, DMPO-OH, and DMPO-CO2− (AN = 15.6 G, AH = 19.0 G)48. This result was confirmed by the deconvoluted EPR spectra in Fig. 5b. The EPR signals of DMPO-H2O+ and DMPO-OH adducts still exist over time, meaning that the concentration of HCOO– is not high enough to scavenge and take them to below the detection limit. When 1.0 M HCOOK was applied, mostly DMPO-CO2− signal could be detected, and no signals were from DMPO-H2O+ and DMPO-OH anymore (Fig. 5c), indicating an efficient reduction-removal of H2O•+ and •OH radical species.

However, one order of magnitude higher HCOOK concentration did not induce higher content of CO2•− species in Fig. 5c. We hypothesize that a further conversion of CO2•− should take place, thus lowering the accumulation of CO2•− species. To confirm that, online gas chromatography (GC) has been used to detect any possible gaseous products in the absence of DMPO. Relative to the HCOOK-free aqueous solution, surprisingly, CO gas can be detected by GC in Fig. 5d. We previously demonstrated the electrochemical redox conversion of HCOO– to CO via CO2•− on coupled anode and cathode48. In this case, the result indicates the reduction of CO2•− to CO by a reductive species, for instance, e–aq, via CO2•− + 2H+ + e–aq → CO + H2O.

Indeed, as the counter species of primary oxidizing H2O•+ species6, the standard potential of H2O•− (also known as the hydrated electron e–aq) is about –2.88 V41 and thus highly reductive. It can convert a stable 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy radical (TEMPO•) into a non-electron-paramagnetic 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine (TEMP)49. As a result, the EPR signal of TEMPO• (AN = 17.3 G, a triple peak with an intensity of 1:1:1) gradually decays over time (Fig. 6a). Further evidence on H2O•− can be found below (Fig. 6b, c). In short, owing to the coexistence of both oxidative and reductive radical species, the spontaneous oxidation-reduction reactions can proceed, like a micro-electrochemical cell with an anode and cathode15, even though the content of redox radical species may not be quite high.

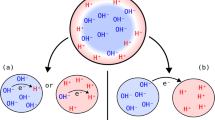

Stabilization of H2O•+/H2O•‒ radicals

It was proposed that the H2O•+/H2O•− radical pair is blinking through electron delocalization in bulk water29, yet the conversion of H2O•+ to •OH via the transfer of one proton is the fastest chemical process30. Although sustaining the equilibrium of the formula, namely H2O ↔ H2O•− + H2O•+, may be possible, a great challenge lies in how to isolate and stabilize H2O•+ and increase its reactivity. Inspired by the previous report that positively charged H2O•+ can be encapsulated in crown ether31, we hypothesize that crown ether may be able to stabilize H2O•+ in aqueous solution. To prove it, 18-crown-6 was selected for the purpose. When 18-crown-6 was added to pure water solution (Supplementary Fig. 6), the signal of DMPO-OH and DMPO- H2O+ increased. Upon increasing the concentration of 18-crown-6 in aqueous solution, a stepwise increase in EPR signal intensity of both DMPO-H2O+ and DMPO-OH adducts was observed in Fig. 7a. With 0.2 M 18-Crown-6 in aqueous solution, a few times higher content of H2O•+ and •OH could be achieved within 20 min (Fig. 7b).

Since H2O•+ is always paired with H2O•− species29, we then evaluated the variation in H2O•− content. As shown in Fig.6b, the presence of 18-crown-6 substantially accelerates the reduction of TEMPO• to TEMP by H2O•− within 20 min, meaning that 18-crown-6 can prevent the fast recombination of H2O•+ and H2O•− species. This interesting finding can be applied to other reaction systems involving H2O•+ and H2O•− radicals. To further strengthen the argument of enhanced H2O•− content, we introduce another monochloroacetic acid (CH2ClCOO−, abbr. Cl-Ac) probe molecule. An H2O•−-induced dechlorination reaction leads to the formation of Cl– anions via Cl-Ac + e–aq/H2O•− → •Ac + Cl– process47, while the amount of Cl– anions in aqueous solution can be quantified by ion chromatography (IC) (Supplementary Fig. 7), with the concentration of Cl– anions calibrated by standard Cl– solution (Supplementary Fig. 8). As shown in Fig. 6c, gas feed can significantly promote the dechlorination reaction and increase the amount of Cl–. Again, when 18-crown-6 has been introduced, 10-fold more Cl– yield has been acquired, indicating one order of magnitude higher concentration of H2O•− species.

Discussion

The aqueous interface-rich systems, such as “droplets-in-gas” and “bubbles-in-water” (Fig. 1), contribute to the development of redox chemistry. In this work, Ar has been selected to create the gas/water interface for the generation of redox radical species. Because Ar is a relatively inert molecule, it does not consume oxidative or reductive radicals. However, upon feeding O2, the EPR density of the oxidative radicals has been raised. This is due to the consumption of reductive radicals. In the case of HCOO−, the oxidation of HCOO− to CO2•− radicals requires oxidative radicals, while the subsequent reduction of CO2•− radicals to detectable CO uses reductive radicals. This process simultaneously consumes both kinds of radicals, making the chemical reaction continuous, which has been a very promising attempt for a relevant extension. For example, the continuous removal and conversion of flue gas, which consists of both oxidative and reductive gaseous feedstock50, should be favorable. In the field of GDE, the gas itself can be either directly hydrated as a high-concentration reactant or unhydrated for forming gas/water interfaces. Although, to simplify the system, a catalyst has not been introduced, further tuning the product selectivity with a catalyst might be possible. In addition, the “bubbles-in-water” system remains as bulk water, which is suitable for electrochemical reactions.

The H2O•+/H2O•− pair should be isolated to improve their chemical reactivity. Even so, both radicals tend to either neutralize or downgrade to •OH/•H radicals. Thereby, the great challenge is to enhance the steady-state concentration of the H2O•+/H2O•− radicals. Further increase of H2O•+/H2O•− content is essential for further potential applications, as demonstrated by introducing 18-Crown-6. The complexation seems to play a crucial role in stabilizing the H2O•+ cations through isolation from H2O•− anions. We thus should pay attention to other ligands or interface parameters that could strengthen this effect. Decoupling the complicated interfacial microenvironment in electrochemistry, GDE for instance, is a reliable way to move forward. Further investigation of the “bubbles-in-water” system and their uses in relevant fields will provide an in-depth understanding of the roles of water-derived redox radical species.

Methods

Reagents

KI (≥99.99%, metals basis), Vitamin C (>99.9%), K4Fe(CN)6 (>99.9%), K3Fe(CN)6 (>99.9%) and 18-Crown-6 (>99.9%) were purchased from Aladdin. HCOOK (≥99.9%), and K2SO3 (≥99.9%) were purchased from Adamas. Monochloroacetic acid (>99%, Alfa Aesar). 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy (TEMPO, >99%, Meryer). All the used aqueous solutions were commercially available (HPLC Plus, Sigma-Aldrich), Ar (6.0 purity, Linde), and O2 (4.5 purity, Linde) were used for gas feeds. The hydrophobic carbon paper (SGL-28BC) was purchased from Toray Industries.

Preparation of Janus hydrophobic/hydrophilic porous carbon paper

Soaking one side of the hydrophobic carbon paper in concentrated nitric acid at 100 °C for 5 h and then ultrasonic cleaned with ethanol and deionized water several times for further use51.

Gas diffusion electrode (GDE) assembly

A Janus hydrophobic/hydrophilic porous carbon paper has been sandwiched between two reaction pond splints with serpentine flow channels (Supplementary Fig. 1). The hydrophobic side ensures the gas flow while the hydrophilic side circulates water, enabling the formation of a large number of gas/water interfaces. The gas flow rate is 40 mL/min, controlled by a gas flowmeter, while the water flow rate is 2 mL/min circulated by a peristaltic pump.

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR)

Electron paramagnetic resonance tests were implemented by a continuous-wave (CW) spectrometer (Bruker EMX micro) operating in X-band mode with a frequency of 9.848 GHz. Each spectrum was recorded with microwave power of 20 mW and modulation amplitude of 1.0 G. EPR simulations were performed based on the hyperfine splitting constants of radicals. The central field is 3355 G, scanning width is 200 G, scanning power is 20 mW, scanning time is 300 s, and modulation amplitude is 1.0 G. DMPO (Dojindo) was utilized as a spin-trapping agent. Before adding DMPO, the water solution has been purged by Ar gas for at least 30 min. Then DMPO-containing water solution was circulated through the Ar-pre-purged GDE at a flow rate of 2 mL/min while the gas feed was performed. After a certain time, a small amount of the solution was transferred to quartz capillary tubes for EPR measurements. Moreover, HCOO– or SO32– was added in DMPO-containing Ar-pre-purged water solution for the redox reactions upon gas feed through GDE. In addition, TEMPO• was added in Ar-pre-purged water solution to scavenge H2O•− radicals upon gas feed for the formation of EPR-silent TEMP.

UV-Vis spectroscopy

UV-Vis spectroscopy was implemented on a QE Pro UV-Visible spectrometer (Ocean Optics) equipped with an HL-2000 light source and a DH-2000-BAL light source (200 to 950 nm). The I– or Fe(CN)64– was added in DMPO-free Ar-pre-purged water solution for the redox reactions upon gas feed through GDE. Then, the resultant solutions were sealed in a Quartz cuvette for UV-Vis measurements. The aqueous solutions were Ar-protected to avoid the influence of air at room temperature.

Ion chromatography (IC) and gas chromatography (GC)

The Cl‒ anions produced by the dechlorination of monochloroacetic acid were evaluated by IC (Analysis Lab). A freshly prepared 4.5 mM K2CO3 and 0.8 mM KHCO3 solution was used as a leachate solution. The testing system has been calibrated with the standard solution. The monochloroacetic acid solution was added in a DMPO-free Ar-pre-purged water solution for dechlorination upon gas feed through GDE. For detecting CO product, HCOO– was added in DMPO-free Ar-pre-purged water solution upon gas feed through GDE and the CO gas was measured by online GC.

Nanoparticle tracking analyzer (NTA)

The pure water without Ar feed was used as a control. Feeding Ar gas through GDE resulted in the formation of nanobubbles in pure water, and this bubbled solution was measured immediately by NTA (Zetaview® from Particle Metrix). The NTA images and size distribution of nanobubbles were acquired.

Data availability

All relevant data are provided in this article and its Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Ruiz-Lopez, M. F., Francisco, J. S., Martins-Costa, M. T. C. & Anglada, J. M. Molecular reactions at aqueous interfaces. Nat. Rev. Chem. 4, 459–475 (2020).

Enami, S., Hoffmann, M. R. & Colussi, A. J. Acidity enhances the formation of a persistent ozonide at aqueous ascorbate/ozone gas interfaces. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 7365–7369 (2008).

Martins-Costa, M. T. C. & Ruiz-López, M. F. Electrostatics and chemical reactivity at the air–water interface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 1400–1406 (2023).

Lee, J. K., Banerjee, S., Nam, H. G. & Zare, R. N. Acceleration of reaction in charged microdroplets. Q. Rev. Biophys. 48, 437–444 (2015).

Davidovits, P., Kolb, C. E., Williams, L. R., Jayne, J. T. & Worsnop, D. R. Mass accommodation and chemical reactions at gas‐liquid interfaces. Chem. Rev. 106, 1323–1354 (2006).

Qiu, L. & Cooks, R. G. Spontaneous oxidation in aqueous microdroplets: water radical cation as primary oxidizing agent. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202400118 (2024).

Lin, S., Cao, L. N. Y., Tang, Z. & Wang, Z. L. Size-dependent charge transfer between water microdroplets. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2307977120 (2023).

Hao, H. X., Leven, I. & Head-Gordon, T. Can electric fields drive chemistry for an aqueous microdroplet? Nat. Commun. 13, 280 (2022).

Jin, S. et al. The spontaneous electron-mediated redox processes on sprayed water microdroplets. JACS Au 3, 1563–1571 (2023).

Qiu, L. Q. & Cooks, R. G. Simultaneous and spontaneous oxidation and reduction in microdroplets by the water radical cation/anion pair. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202210765 (2022).

Lee, J. K. et al. Spontaneous generation of hydrogen peroxide from aqueous microdroplets. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 19294–19298 (2019).

Song, X., Basheer, C. & Zare, R. N. Water microdroplets-initiated methane oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 27198–27204 (2023).

Song, X. et al. One-step formation of urea from carbon dioxide and nitrogen using water microdroplets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 25910–25916 (2023).

Song, X., Basheer, C. & Zare, R. N. Making ammonia from nitrogen and water microdroplets. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2301206120 (2023).

Chamberlayne, C. F. & Zare, R. N. Microdroplets can act as electrochemical cells. J. Chem. Phys. 156, 054705 (2022).

Wakerley, D. et al. Gas diffusion electrodes, reactor designs and key metrics of low-temperature CO2 electrolysers. Nat. Energy 7, 130–143 (2022).

Lees, E. W., Mowbray, B. A. W., Parlane, F. G. L. & Berlinguette, C. P. Gas diffusion electrodes and membranes for CO2 reduction electrolysers. Nat. Rev. Mater. 7, 55–64 (2021).

Angulo, A., van der Linde, P., Gardeniers, H., Modestino, M. & Fernández Rivas, D. Influence of bubbles on the energy conversion efficiency of electrochemical reactors. Joule 4, 555–579 (2020).

Nguyen, T. N. & Dinh, C. T. Gas diffusion electrode design for electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 7488–7504 (2020).

Higgins, D., Hahn, C., Xiang, C., Jaramillo, T. F. & Weber, A. Z. Gas-diffusion electrodes for carbon dioxide reduction: a new paradigm. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 317–324 (2019).

Li, K. et al. Significantly accelerated photochemical and photocatalytic reactions in microdroplets. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 3, 100917 (2022).

Haziri, V., Nha, T. P. T., Berisha, A. & Boily, J.-F. A gateway for ion transport on gas bubbles pinned onto solids. Commun. Chem. 4, 43 (2021).

Vogel, Y. B. et al. The corona of a surface bubble promotes electrochemical reactions. Nat. Commun. 11, 6323 (2020).

Kim, C. et al. Tailored catalyst microenvironments for CO2 electroreduction to multicarbon products on copper using bilayer ionomer coatings. Nat. Energy 6, 1026–1034 (2021).

Lv, X., Liu, Z., Yang, C., Ji, Y. & Zheng, G. Tuning structures and microenvironments of Cu-based catalysts for sustainable CO2 and CO electroreduction. Acc. Mater. Res. 4, 264–274 (2023).

Li, M., Xie, P., Yu, L., Luo, L. & Sun, X. Bubble engineering on micro-/nanostructured electrodes for water splitting. ACS Nano 17, 23299–23316 (2023).

Qiu, L., Morato, N. M., Huang, K.-H. & Cooks, R. G. Spontaneous water radical cation oxidation at double bonds in microdroplets. Front. Chem. 10, 903774 (2022).

Li, L. et al. Electron paramagnetic resonance tracks condition-sensitive water radical cation. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 14, 9183–9191 (2023).

Ben-Amotz, D. Electric buzz in a glass of pure water. Science 376, 800–801 (2022).

Loh, Z. H. et al. Observation of the fastest chemical processes in the radiolysis of water. Science 367, 179–182 (2020).

Inokuchi, Y., Ebata, T. & Rizzo, T. R. UV and IR spectroscopy of cold H2O+–benzo-crown ether complexes. J. Phys. Chem. A 119, 11113–11118 (2015).

Jungwirth, P. & Tobias, D. J. Specific ion effects at the air/water interface. Chem. Rev. 106, 1259–1281 (2006).

Tarbuck, T. L., Ota, S. T. & Richmond, G. L. Spectroscopic studies of solvated hydrogen and hydroxide ions at aqueous surfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 14519–14527 (2006).

Sagar, D. M., Bain, C. D. & Verlet, J. R. R. Hydrated electrons at the water/air interface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 6917–6919 (2010).

Roeselová, M., Vieceli, J., Dang, L. X., Garrett, B. C. & Tobias, D. J. Hydroxyl radical at the air−water interface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 16308–16309 (2004).

Xing, D. et al. Capture of hydroxyl radicals by hydronium cations in water microdroplets. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202207587 (2022).

Zhao, R., Li, L., Wu, Q., Li, Q. & Cui, C. Key role of cations in stabilizing hydrogen radicals for CO2-to-CO conversion via a reverse water-gas shift reaction. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 15, 1914–1920 (2024).

Villamena, F. A., Hadad, C. M. & Zweier, J. L. Theoretical study of the spin trapping of hydroxyl radical by cyclic nitrones: a density functional theory approach. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 1816–1829 (2004).

Mu, S. et al. Hydroxyl radicals dominate reoxidation of oxide-derived Cu in electrochemical CO2 reduction. Nat. Commun. 13, 3694 (2022).

Mehrgardi, M. A., Mofidfar, M. & Zare, R. N. Sprayed water microdroplets are able to generate hydrogen peroxide spontaneously. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 7606–7609 (2022).

Armstrong, D. A. et al. Standard electrode potentials involving radicals in aqueous solution: inorganic radicals (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 87, 1139–1150 (2015).

Gong, C. et al. Fast sulfate formation initiated by the spin-forbidden excitation of SO2 at the air-water interface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 22302–22308 (2022).

Chen, Z. et al. Rapid sulfate formation via uncatalyzed autoxidation of sulfur dioxide in aerosol microdroplets. Environ. Sci. Tech. 56, 7637–7646 (2022).

Yang, J. et al. Unraveling a new chemical mechanism of missing sulfate formation in aerosol haze: gaseous NO2 with aqueous HSO3–/SO32–. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 19312–19320 (2019).

Zhang, X.-P., Li, Y.-N., Sun, Y.-Y. & Zhang, T. Inverting the triiodide formation reaction by the synergy between strong electrolyte solvation and cathode adsorption for lithium–oxygen batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 18394–18398 (2019).

Ibañez, D., Garoz-Ruiz, J., Heras, A. & Colina, A. Simultaneous UV–visible absorption and Raman spectroelectrochemistry. Anal. Chem. 88, 8210–8217 (2016).

Yu, K. et al. Mechanism and efficiency of contaminant reduction by hydrated electron in the sulfite/iodide/UV process. Water Res. 129, 357–364 (2018).

Zheng, X. et al. Electrochemical redox conversion of formate to CO via coupling Fe‐Co layered double hydroxides and Au catalysts. Chem. Eur. J. 30, e202303383 (2024).

Chen, L. et al. Accurate identification of radicals by in-situ electron paramagnetic resonance in ultraviolet-based homogenous advanced oxidation processes. Water Res. 221, 118747 (2022).

Kong, C. J., Prabhakar, R. R. & Ager, J. W. Electrochemical conversion of carbon dioxide to methyl formate with flue gas as a feedstock. Chem. Catal. 2, 2124–2126 (2022).

Guo, D. et al. Achieving high mass loading of Na3V2(PO4)3@carbon on carbon cloth by constructing three-dimensional network between carbon fibers for ultralong cycle-life and ultrahigh rate sodium-ion batteries. Nano Energy 45, 136–147 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (22372027, 22202034, and 22272020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.C. proposed the idea and led the project. R.Z. carried out the experiments. L.L., Q.W., W.L., and Q.Z. implemented part of the characterizations. R.Z. and C.C. wrote the manuscript. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Xuzhong Gong, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, R., Li, L., Wu, Q. et al. Spontaneous formation of reactive redox radical species at the interface of gas diffusion electrode. Nat Commun 15, 8367 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52790-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52790-9

This article is cited by

-

Bulk water redox chemistry enables radical-mediated C–C coupling in CO2 electroreduction

Nature Chemistry (2025)