Abstract

In response to gradual nanoindentation, the surface of muscovite mica deforms by sudden stochastic nanometer-scale displacement bursts. Here, the statistics of these displacement events are interpreted using a statistical model previously used to model earthquakes to understand how chemically reactive environments alter the surface properties of this material. We show that the statistics of nanoindentation displacement bursts in muscovite mica are tuned by chemomechanical weakening in a manner similar to how the statistics of model events are tuned by a mechanical weakening parameter that describes how easily system-spanning cracks can be nucleated. Because the predictions of this model are independent of any surface defects or structural details, these results suggest this simple model can be universally used to describe chemomechanical weakening in many systems prone to slip avalanches on a wide range of spatio-temporal scales.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The interaction between the surface of a material and its environment defines its behavior in engineering applications. This is because near-surface structure determines local chemical bonding and non-bonding interactions and surface energies, which control bond breaking during material failure1. For example, the surface bonds in CaO, a critical component in common cement, can be attacked by environmental water thereby reducing its contact hardness by several orders of magnitude2. Similarly, chemical reactions at the surface of sandstone rocks can reduce its shear and failure strength3,4.

The effect that an environment has on a material is more pronounced for materials with high surface area-to-volume ratios such as those in the common naturally occurring minerals from the mica group, which comprises cation-bounded crystalline phyllosilicate layers with near-perfect cleavage5,6,7. These interesting physical characteristics make micas impact applications such as geological carbon sequestration8, nuclear waste storage9, efficient gas filtration10 and detection11, and monitoring pathogens in natural water sources12. However, these characteristics also make micas prone to environmental chemomechanical weakening13,14. While previous theoretical work has quantified the effect of chemical interactions on surface mechanical properties, these methods rely on molecular dynamics and as such are limited to small system sizes and short duration and require significant computational resources15,16. Understanding chemo-mechanical effects in mica minerals is especially complicated because these materials are layered, and hence are highly anisotropic5. Simpler models that rely on chemical kinetics to describe the silica-water interactions in quartz have been proposed, but they cannot be generalized because doing so requires measuring kinetic parameters unique to this interaction and, in contrast to mica, quartz is a nearly-isotropic material with no pronounced cleavage planes17.

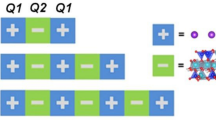

Previous work showed that muscovite mica is weakened when exposed to a basic aqueous solution13. Specifically, the surface Si-O-Si bonds are increasingly hydrolyzed in the presence of increasing hydroxyl anion (OH−) concentration13. When these bonds are hydrolyzed, they leave the material weaker and thus less able to store elastic energy from gradual indentation. In turn, the weakened material is prone to larger fractures at lower load, as demonstrated schematically in Fig. 1. This weakening was shown to influence the occurrence, size, and energy released from observed nanoindentation displacement bursts, suggesting that a physical model that makes explicit predictions about these quantities may apply. Here, we compare the statistics of displacement bursts measured as a function of chemical environment to the predictions for the statistics of discrete relaxation events from a simple, widely-applicable micromechanical model that applies in systems that have the same symmetries and dimensionality and similar interaction ranges18,19,20. Renormalization group calculations predict that the model should be widely applicable. This prediction has been verified – the model has been successfully utilized in many scenarios ranging from the compression and nanoindentation of bulk metallic glasses to the statistics of luminosity bursts in stars18,21,22,23,24,25. In addition to its broad applicability, this model is only tuned by a single “weakening” parameter20. This weakening parameter is higher when a small initial failure can more easily lead to runaway failures throughout the rest of the material20, as may be the case depending on the environmental conditions. In this work, this model for avalanche statistics is utilized as a framework to interpret the effect of chemomechanical weakening on displacement bursts found in nanoindented muscovite mica.

a Muscovite is indented by a Berkovich tip, and its structure is shown in the inset below where Al is gray, O is red, Si is blue, and K is purple. b In the dry condition, the elastic deformation of muscovite proceeds farther prior to brittle failure, when compared to muscovite submerged in aqueous solution. c At failure, the muscovite releases its stored elastic energy via delaminations, fractures, and spalling events, all recorded as displacement bursts in nanoindentation traces. d, e When mica is exposed to a basic solution Si-O-Si bonds are hydrolyzed which weakens the top layer and allows for less energy to be stored elastically prior to brittle failure.

Specifically, we show a rigorous statistical analysis of the nanoindentation displacement bursts detected in nanoindented mica exposed to different aqueous solutions. In order to increase OH− concentration¸ the three environments to which separate mica samples were exposed are deionized (DI) water, a 0.1 M NaCl solution with pH adjusted to pH 9.8 with NaOH , and a 0.1 M NaCl solution with pH adjusted to pH 12 with NaOH. Notably, the muscovite surface is not terminated by pure Si-O-Si sites, but also hexagonal cavities which contain charge-balancing K+ or Na+ ions26,27. Indentations in a “dry” condition in ambient atmosphere ( ~ 30% relative humidity) were performed as a baseline test for each sample prior to being introduced to their chemically reactive environments, shown in detail in Supplementary Discussion 7. Since the tetrahedral silica sheets that comprise mica surfaces are susceptible to hydroxyl attack, we hypothesized that an increased pH will correspond to an increased chemomechanical weakening that will manifest as a decrease in the loads where displacement bursts begin to occur and impact the statistics of displacement burst size and energy release28,29.

While previous work13 identified the weakening of mica and found evidence for both chemically-assisted and purely mechanical displacement burst events, our current analysis tests the hypotheses that these bursts can be described by the statistics of sudden failures, or slips, in response to gradual changes in stress. We report that the statistics of the released energy from smaller bursts in each condition are ordered from less- to more-concentrated hydroxyl ions in solution, as predicted by the model20,30. We see that the average size of lower energy bursts follows the same ordering according to the chemical forcing (OH− concentration) and the corresponding chemomechanical weakening. We also show that this ordering in burst size occurs primarily at low load conditions, suggesting that this ordering is most prevalent at the near interfacial region in muscovite and is driven by the behavior of delamination events. Finally, we show that burst event energy histograms at critical load levels follow the expected mean-field scaling form predicted by avalanche statistics20. Here, we show that previously reported chemomechanical behavior of muscovite mica13, namely the displacement bursts, can be interpreted as slip events in the framework of avalanche statistics. These findings imply that the model can be used to broadly quantify chemomechanical weakening in highly anisotropic materials prone to displacement bursts.

Results

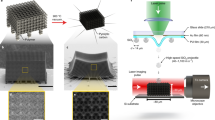

Example indents for each of the four conditions are shown in Fig. 2a, with an inset showing the behavior of each indent during initial loading. Load-displacement curves for all indents analyzed are shown in Supplementary Discussion 6. An example tip velocity profile, with displacement bursts highlighted, and an example profile magnification are shown in Fig. 2b.

a An example load-depth curve for the four conditions tested. In order of increasing chemomechanical weakening, the dry condition, muscovite submerged in deionized water (DI water), pH 9.8 water, and pH 12 water are shown, with an inset showing the same at low loads. The largest events at intermediate load occur in the dry condition, and the largest events at low load occur in the pH 12 condition. b An example indent in the dry condition with detected bursts highlighted and the profile of a single example burst in the inset. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Displacement bursts are identified as parts of the loading curve where pop-in displacement is greater than 1.0 \(\, {nm}\), the thickness of a single 2:1 layer of muscovite7,31,32. Event sizes are quantified in terms of the displacement burst energy, \(E={P}_{b}\Delta x\) for event initiation load \({P}_{b}\) and pop-in displacement \(\Delta x\), though similar results are obtained if the event size is defined by the pop-in displacement alone, as shown in Supplementary Discussion 2 and 3. These burst events occur over far fewer than ten timesteps, the minimum required to obtain accurate event duration statistics33. As such, only the event sizes are compared to the avalanche model predictions, though detailed duration analysis is shown in Supplementary Discussion 4. Namely, the model predicts that the avalanche event size \(S\) should follow a power-law distributed complementary cumulative distribution function (CCDF) \(C\left(S\right) \sim {S}^{1-\tau }\), where the value of the power-law scaling exponent \(\tau\) depends solely on system symmetries, interaction range, and dimensionality34,35,36. The simplest mean-field model of slip statistics can be shown to apply in three-dimensional systems where the slip has localized in shear bands and the range of interaction is large compared to the system scale; in this case, the model predicts \(\tau=3/2\)20. The model also predicts that \(C\left(S\right) \sim {S}^{1-(\tau+\sigma )}\) where \(\tau+\sigma=2\) if events are integrated over a large range of stresses below the critical stress37,38. The width of the scaling regime is tuned by the model weakening \(\varepsilon\)20. Namely, for small events larger than the system noise, \(C\left(S\right)\) obeys its power-law scaling up to a cutoff \({S}_{\max }\, \sim \,1/{\varepsilon }^{2}\)20,25. For sizes \(S > {S}_{\max }\), the avalanche size distribution is predicted to decay exponentially20. Finally, the average size of large events \(\left\langle {S}^{3}\right\rangle /\left\langle {S}^{2}\right\rangle\) is predicted to scale with the weakening \(\varepsilon\) linearly20,30. The statistics of burst events are compared to a simulation of mean-field avalanche statistics, described in detail in Methods.

Mean pop-in energy versus load

In the nanoindentation experiments, a total of 1283 bursts with displacements greater than 1.0 nm are identified in the dry condition, 1872 in the DI water, 2499 in the pH 9.8 solution, and 2396 in the pH 12 solution. Figure 3 shows the average energy \(\left\langle E\right\rangle\) versus the load \({P}_{b}\), where 95% confidence intervals generated by bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrapping are shown as shaded regions for each condition. Each indent is split into 20 evenly-spaced bins in load, then all events in each given load bin are collected together to calculate \(\langle E\rangle\) for that bin.

The shaded regions show the 95% confidence intervals of \(\langle E\rangle\) in each bin generated by bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrapping. Data at low loads are highlighted in the inset for each condition. The average burst energy spikes at intermediate load \(3\, {mN}\le {P}_{b}\le 5.5\, {mN}\) in the dry condition and \(1.5\, {mN}\le {P}_{b}\le 3\, {mN}\) in the DI conditions. The average event energy is ordered by environmental pH within the load range \(0\le {P}_{b}\le 1\, {mN}\) (inset) in the order predicted by increasing model weakening in avalanche statistics20. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Figure 3 shows that the average energy of events increases with the load for muscovite in each condition, agreeing with our previous findings13. The average energy of pop-ins tends to fall along the same trendline for all conditions aside from several notable excursions at intermediate load levels. For example, the dry condition average pop-in energy is significantly higher than the trend line followed by the other conditions for loads \(3\, {mN}\le {P}_{b}\le 5.5\, {mN}\), reaching a maximum of \({\left\langle E\right\rangle }_{\max }=128.5\, {pJ}\) with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) calculated via bootstrapping between \(95.1\, {pJ}\) and \(168.5\, {pJ}\) at \({P}_{b}=4.00\pm 0.25\, {mN}\). This excursion would be expected in the case that the muscovite under a Berkovich probe tends to bend elastically until a large fracture in that load range with an energy between \(95.1\, {pJ}\) and \(168.5\, {pJ}\).

Similarly, the pop-in event energy for mica submerged in DI water peaks above the trendline shared by the other conditions for loads in the range \(1.5\, {mN}\le {P}_{b}\le 3.0\, {mN}\). This excursion reaches a maximum of \({\left\langle E\right\rangle }_{\max }=29.3\, {pJ}\), 95% CI = (\(23.4\, {pJ},\,36.5\, {pJ}\)) at \({P}_{b}=2.00\pm 0.25\, {mN}\). The peak appears at a lower load and has smaller energy for the sample submerged in DI water because Si-O-Si bonds at the muscovite surface (or at the interface between the Berkovich probe and muscovite) are experiencing hydroxylation in water, while also becoming more soluble due to stress17. As such, the muscovite exposed to the DI water cannot store as much elastic energy on average before the surface slips or cracks. The peak energy therefore occurs at a lower load in the DI water condition than for the dry condition, similar to the buildup followed by sudden failure that precedes large avalanches in other contexts30. The pH 9.8 and pH 12 conditions do not have apparent peaks, which would be expected if the material became too weakened due to hydrolysis reactions to store more than a nominal amount of elastic energy before the first plastic event. Because the events at low loads are generally among the first plastic events in each indent (see Supplementary Fig. 12), these pop-ins are likely to be the most sensitive to environmental effects.

Load at largest event for each condition

This intuitive ordering in chemomechanical weakening is bolstered by analysis of the average load at which the largest event occurs. Representative example plots of contact pressure \({\sigma }_{c}={P}_{b}/{A}_{c}\) for contact area \({A}_{c}\) versus load are shown in Fig. 4, where the largest failure for the sample indent in each condition is bolded. See Supplementary Fig. 18 for equivalent plots for the indents exposed to each condition.

In each curve, the largest relaxation is shown bolded. The largest relaxation occurs at the highest load in the dry condition and the load at the largest event decreases monotonically with increasing environmental concentration of OH−. Furthermore, the highest average contact pressure is attained at loads less than 1 \({mN}\) for each condition. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In each condition, the contact pressure remains at a high value until a single large failure is nucleated. The load remains at a high value to the largest load in the dry condition, and the largest event is nucleated at lower load with increasing environmental hydroxyl concentration. For the dry condition trials, the load at which the largest event occurs is \(\left\langle {P}_{b}\right\rangle=4.12\, {mN},\,95\%{CI}=(3.91\, {mN},\,4.36\, {mN})\) calculated via bootstrapping over all dry condition indents on Sample 1. The largest event occurs at similar \(\langle {P}_{b}\rangle\) for the other samples’ dry conditions; see Supplementary Fig. 14 and Supplementary Discussion 7 for detailed analysis of these other dry conditions. The largest events in the DI water occurred at \(\left\langle {P}_{b}\right\rangle=2.20\, {mN},\,95\%{CI}=(2.00\, {mN},2.47\, {mN})\), i.e. lower than for the dry condition. Finally, the largest pH 9.8 condition events occurred at \(\left\langle {P}_{b}\right\rangle=1.18\, {mN},\,95\%{CI}=(1.04\, {mN},\,1.45\, {mN})\) and in the pH 12 condition at \(0.96\, {mN},\,95\%{CI}=(0.90\, {mN},\,1.08\, {mN})\). The load at the largest event decreases because the surface is weaker in the environments with higher OH− ion concentrations17; see Supplementary Discussion 8 and Supplementary Fig. 18 for similar plots for all indents.

The Si-O-Si bonds in muscovite are most stressed (and, therefore most prone to hydrolysis) when the contact pressure is highest and the effect of the environment on the muscovite is most pronounced. As seen in Fig. 4, the highest contact pressure is observed at low load in all conditions. For the dry condition, the highest contact pressure is observed at a median of \(0.411\, {mN},\,95\%{CI}=(0.312\, {mN},0.483\, {mN})\) across all indents, where the 95% confidence intervals obtained by bias corrected and accelerated bootstrapping. In the DI condition, the maximum contact pressure is observed at \(0.223 \, mN,\,95\%{CI}=(0.207\, {mN},0.238\, {mN})\), lower than the dry condition. The load at which maximum contact pressure is achieved is lower for the pH 9.8 and pH 12 conditions at \(0.212 \, mN,\,95\%{CI}=(0.209\, {mN},0.217\, {mN})\) and \(0.193 \, mN,95\%{CI}=(0.187\, {mN},0.205\, {mN})\), respectively. The highest contact pressures are maintained for nearly all indents at loads less than 1 \(\, {mN}\); thus, the effect of environmental hydroxyl can be best quantified in this lower load range. As further evidence for this claim, the most significant impact on the event energy statistics is also observed for pop-ins that initiate at displacements less than roughly 80 nm, as detailed in Supplementary Discussion 10.

In all conditions, the total indentation depth exceeds 70 nm (and thus around that many 2:1 layers) at loads beyond roughly 1 mN; thus, the expected effect from the weakening if only the surficial layers were impacted should be minimal. However, our results suggest a systematic effect on the load at which the largest pop-in occurs. There are two likely scenarios for where these first large fracture events are occurring: either at the muscovite surface propagating from the corners of the Berkovich indent, or in the subsurface just under the probe. Large fractures could emerge at the surface because, despite lower stress at the surface, the chemomechanical weakening of the Si-O-Si bonds could be significant enough to facilitate large fractures. In contrast, these events could emerge in the sample subsurface as well, because we anticipate that a liquid layer can be trapped in-between the tip and the surface (or liquid can diffuse with increasing indentation depth), so the deeper indented layers can also experience chemical attack by the hydroxyl ions.

Comparisons to avalanche scaling theory

The average size of events at low loads, \(0\, {mN}\le {P}_{b}\le 1\, {mN}\), is ordered according to chemomechanical weakening, as shown in Fig. 5. This ordering is driven primarily by the size of the largest events, quantified in the model by the ratio between the third moment of avalanche size and its second moment20,30. The pH 12 environment has the largest value of \(\left\langle {E}^{3}\right\rangle /\left\langle {E}^{2}\right\rangle\) in the load range \(0\, {mN}\le {P}_{b}\le 1\, {mN}\) at \(16.03\, {pJ},\,\)95% CI = \((14.58\, {pJ},\,17.48\, {pJ})\), followed by the pH 9.8 at \(13.42\, {pJ}\), 95% CI = \((11.48\, {pJ},\,15.37\, {pJ})\), the DI water at 4.87 pJ, 95% CI = \((3.24\, {pJ},\,6.49\, {pJ})\), then finally the dry condition at 1.42 pJ, 95% CI = \((1.32\, {pJ},\,1.53\, {pJ})\). All differences in the large event size are statistically significant with \(p\le 0.05\), with further details shown in Supplementary Discussion 5. As shown in Fig. 5a, the average size of events in the mean-field simulation is also ordered by model weakening, where the sizes of simulated stress drop avalanches are reported in units of the single-cell failure stress \({\tau }_{f}\).

The large avalanche size is represented by the third moment of event size divided by the second moment of event size for (a) the simulations with increasing model weakening compared to (b) the experiments for the dry, DI water, pH 9.8 and pH 12 experimental conditions for events that occur at \({P}_{b}\le 1\, {mN}\). The average displacement burst energy trends with environmental hydroxyl concentration in the same way that the average avalanche size does with model weakening. Confidence intervals are generated using bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrapping. See Supplementary Discussion 5 for more details on the statistical significance of these differences. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In order of increasing simulation weakening, the average large event size is \(\left\langle {S}^{3}\right\rangle /\left\langle {S}^{2}\right\rangle=142.2\,{\tau }_{f}\) with 95% CI = \((118.6\,{\tau }_{f},\,179.6\,{\tau }_{f})\), \(693.9\,{\tau }_{f}\) with 95% CI = \((595.4\,{\tau }_{f},\,784.8\,{\tau }_{f})\), \(963.2\) \({\tau }_{f}\) with 95% CI = \((910.7\,{\tau }_{f},\,1025\,{\tau }_{f})\), and \(1066\,{\tau }_{f}\) with 95% CI = \((1025\,{\tau }_{f},\,1119\,{\tau }_{f})\), respectively, generated via bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrapping. This ordering in average energy is explicitly expected to be the case if the muscovite displacement bursts follow avalanche scaling theory and the chemomechanical weakening experienced by the muscovite is directly comparable to the weakening in the avalanche model13,20.

The theory also predicts that the CCDF of event sizes \(C(S)\) should follow a power-law until a cutoff size \({S}_{\max }\) that depends on the system weakening. For sizes larger than this cutoff, the CCDF drops off faster20. Figure 6 shows the size CCDFs of released energy from the nanoindentation bursts compared to the tails of size CCDFs from the simulation.

a The tails of the simulated avalanche size CCDF \(C(S)\) are ordered by model weakening. Smaller events follow the mean-field \(C\left(S\right) \sim {S}^{-1/2}\) scaling20. b The dry condition has primarily small events and is far from its critical point in this load range. The DI condition has pop-in energy CCDF \(C\left(E\right) \sim {E}^{-1}\) scaling in this load range, as would be expected in a stress-integrated version of the avalanche model37,38. The pH 9.8 condition has the same scaling, but a cutoff at \(13\, {pJ}\). The pH 12 condition trends exponentially, as would be expected in an avalanching system far beyond the scaling regime. In (a) and (b), the maximum size or energy, respectively, at which scaling is observed is shown with a star (✰), and a right-facing triangle (▷) if the CCDF represents a condition far from the critical point. See the Supplementary Discussion 9 for more details. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In the mean-field simulation, the size CCDF follows \(C\left(S\right) \sim {S}^{-1/2}\) until a cutoff size \({S}_{\max }\), which decreases for increased model weakening20 and is determined by inspection as the value of \(S\) at which a decay faster than a power law dominates. In order of increasing simulation weakening, \({S}_{\max }=107.3\,{\tau }_{f},41.7\,{\tau }_{f},27.8\,{\tau }_{f},\) and \(1.36\,{\tau }_{f}\) respectively. Furthermore, the tails of the distribution in the simulation occur at increasing values of \(S\) with increasing weakening. In other words, the largest avalanches get larger as weakening increases20,30. Similar behavior is noted in the nanoindentation energy CCDF \(C(E)\) for events in the load range \(0\le {P}_{b}\le 1\, {mN}\), but instead ordered by the hydroxyl ion concentration. The dry condition follows a sharp exponential drop with primarily very small events. This sharp exponential decay would be expected for a model avalanche system far from its critical stress20,38,39. That is, because there is no power law behavior for the system far from its critical point, \({S}_{\max }\) in the full load range must be much larger than the pop-ins that occur in this load range; this is denoted in Fig. 6 with a right-facing arrow. Furthermore, these events are very small with event energy \(E < 3\, {pJ}\) and indenter displacements \(x < 1.2\, {nm}\) (see Supplementary Discussion 2 and Supplementary Discussion 3), suggesting these events are primarily caused by delaminations from the first surface layer of the muscovite, assuming that layers of muscovite are roughly 1 nm thick7,31,32.

The muscovite submerged in DI water \(C(E)\) has a larger tail than for the dry condition and follows closely to \(C\left(E\right) \sim {E}^{-1}\) with no obvious exponential tail. The graph would not be expected by the model to have a cutoff size \({S}_{\max }\) if this size was much larger than those observed in the load range, and would be expected to have an exponent of –1 if the events are integrated over stress20,40. In other words, because there appears to be no exponential tail, the true value of \({S}_{\max }\) must be larger than the largest pop-in detected in the sample set20,36; this is denoted in Fig. 6 with a right-facing triangle. The events that scale with exponent –1 are primarily larger than ~1 \(\, {pJ}\), but smaller than 10 \(\, {pJ}\), which fall in the range of energies expected for delamination or kinking events13,31,32,41. The associated tip displacements for these events are between 1 nm and 6 nm, suggesting that these low-energy events push through one and up to six muscovite layers at once7,31. The energies of most scaling events in the DI condition are too small to represent surface fracture events, though they propagate through more layers of muscovite than indicated for the dry condition13.

Continuing the expected trend with increasing chemomechanical weakening, the pH 9.8 condition \(C(E)\) has a larger tail than both the DI and dry conditions. The scaling portion of the pH 9.8 condition CCDF follows \(C\left(E\right) \sim {E}^{-1}\) similar to the DI water condition, though unlike the DI water condition, it appears to have a cutoff at around \(E\approx 12.3\, {pJ}\), denoted in Fig. 6 with a star. In addition, the events also displace the tip more than in the DI condition, with the largest scaling events displacing up to about 12 nm of material, i.e., more than ten layers. As such, it is reasonable to label the average events here as surface fracture events13,32,42. Finally, the muscovite exposed to the pH 12 water appears to have a \(C(E)\) almost entirely dominated by an exponential tail that rests above all the other conditions. This behavior is expected by the model when the weakening is large and the cutoff size is expected to be much smaller than for lower weakenings20,30. That is, \({E}_{\max }=3 \, pJ\) for this condition is only slightly larger than the noise floor at ~0.6 \(\, {pJ}\)20,36 and is denoted in Fig. 6 with a star. The events also correspond to larger tip displacements, up to 30 layers, which would be expected for fracture events13,42. Because the \({E}_{\max }\) is on the order of the energy expected for the movement of a single layer13, it is reasonable to suggest that pH 12 saturates the weakening effect in this system20. That is, increasing the pH to values more than 12 would likely result in similar pop-in behaviors because the bonds are already mostly weakened when combined with the mechanical forcing from the indenter tip. This effect may also be reflected in Fig. 5, where it appears that the difference in \(\left\langle {E}^{3}\right\rangle /\left\langle {E}^{2}\right\rangle\) is more significant between the DI water and pH 9.8 conditions than between pH 9.8 and pH 12.

Figure 3 shows that when large fracture events dominate the muscovite mica dynamics as is the case for the dry and DI water conditions, events leading up to those failures are expected to follow mean field avalanche statistics. The dry condition critical load range is \(3\, {mN}\le {P}_{b}\le 5.5\, {mN}\), observed as the portion of its \(\langle E\rangle\) versus \({P}_{b}\) curve that trends above the other conditions in Fig. 3. The DI condition \(\langle E\rangle\) versus \({P}_{b}\) similarly trends above other conditions for its critical load range of \(1.5\, {mN}\le {P}_{b}\le 3\, {mN}\). A graph of the event size CCDFs for all four conditions in their respective load ranges are shown in Fig. 7.

The events that scale closest to the mean-field prediction are shown bolded for each condition. Increasing the environmental pH leads to mean-field scaling in the size CCDF at lower loads. These findings are consistent with the interpretation that the large events that make up the local maxima in \(\langle E\rangle\) versus \({P}_{b}\) can be interpreted as critical system-spanning avalanche events and the mean-field scaling emerges because there is a broad range of events that occur close to criticality. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Figure 7 shows \(C(E)\) for all conditions in their respective critical load ranges. In the load range \(3.00\, {mN}\le {P}_{b}\le 5.50\, {mN}\), the dry condition follows the mean-field expected \(C\left(E\right) \sim {E}^{-1/2}\) for events with energies between 10.9 \(\, {pJ}\) and 201 \(\, {pJ}\). In the lower load range \(1.50\, {mN}\le {P}_{b}\le 3.00\, {mN}\), the DI water now instead follows \(C\left(E\right) \sim {E}^{-1/2}\) for event energies between 5.9 \(\, {pJ}\) and 31.6 \(\, {pJ}\). The event energy scaling regime occurs for smaller events in the DI water, which would be expected since the surface was weakened by hydroxyl ion attack compared to the dry condition. Scaling close to the mean-field prediction at decreased event energies is observed at lower load ranges for the pH 9.8 and pH 12 conditions, despite no obvious maxima appearing for those conditions in Fig. 3. Scaling emerges for events in the pH 9.8 condition in the load range \(0.40\, {mN}\le {P}_{b}\le 1.30\, {mN}\) for event energies between 2.52 \(\, {pJ}\) and 12.5 \(\, {pJ}\). For pH 12, the critical load range is \(0.05\, {mN}\le {P}_{b}\le 0.8\, {mN}\) and scaling is observed for events between 0.93 \(\, {pJ}\) and 3.33 \(\, {pJ}\). Analysis of the other conditions in each of these load ranges is shown in Supplementary Discussion 9.

Discussion

For completeness, alternative hypotheses are first discussed. One reasonable alternative hypothesis that could explain our results would be that a significant portion of the muscovite surface was dissolved during the preparation of each sample. In ambient conditions, the dissolution rate of muscovite is on the order of \(2.4\times {10}^{-17}{mol\; c}{m}^{-2}\,{s}^{-1}\); assuming each sample was exposed for the maximum of 12 hours, at most \(2.6\times {10}^{-12}\) moles, or \(5.9\times {10}^{-8}\,\%\) of the sample mass, could have dissolved while each sample was submerged28. Because such an insignificant volume of the sample was dissolved during our testing, it is unlikely that ambient dissolution could explain the results. Rather, our results may be interpreted as the consequence of a pressure solution phenomenon – that is, the chemical bonds in the mica are stressed by mechanical forces from the indenter tip, making them more susceptible to hydroxyl attack as the pH increases. This phenomenon has been shown to increase the dissolution rate of silica by over 5 orders of magnitude when its surface is under pressure from a diamond tip43. Our results show a statistically significant and monotonic effect on the pop-ins as a function of increasing [OH−], consistent with the expected behavior for the pressure solution effect.

Another possibility that should be discussed is if these results could be explained by sample-to-sample variability. Our previous work on these samples showed that the energy distributions for events dominated by purely mechanical effects were drawn from the same distribution for all samples while energy distributions for chemically-assisted events were significantly different and changed monotonically with increasing pH13. If these deviations were caused by sample surface differences, tip misalignment, or some other experimental effect, these differences would not have correlated with environmental pH. While detailed analysis of the control dry tests for each condition indeed show a small ( < 15%) statistically significant sample-to-sample variability (see Supplementary Discussion 7), these differences are not large enough to account for the effects observed here.

An additional potential confounding factor would be if the loading rate was fast enough that each detected displacement burst reflected the behavior of more than one physical pop-in event. Notably, the model would expect different scaling and event behavior in these cases21,30,33,38,44. Detailed analysis of the pop-in duration and inter-event time performed in Supplementary Discussion 4 suggests a one-to-one correspondence between detected bursts and physical pop-in events for over 98% of both large and small pop-in events.

Taken together, these results suggest that the displacement bursts identified during muscovite nanoindentation follow avalanche scaling theory. Using simulations, we show that the average avalanche size increases with the system weakening in the same way that in experiments the aqueous hydroxyl changes the size of the largest displacement burst events at low load20,45. Namely, these results show that higher chemomechanical weakening leads to increased occurrence of larger displacement bursts similar to how avalanche model weakening increases the size of avalanche events from a simple mean-field simulation of avalanche statistics. These results also show power-law scaling of displacement burst energy at lower loads can be explained within the context of this avalanche model. The statistics of muscovite bursts at critical load levels affected by the aqueous hydroxyl concentrations are then shown to follow mean-field avalanche scaling.

These results also suggest avalanche slip statistics may be a promising tool for quantifying and predicting the effects that chemically reactive environments have on the deformation behavior of anisotropic layered materials. While nanoindentation bursts have traditionally been discarded as noise in nanoindentation studies, recent works have used them to identify dynamical properties of the material46,47,48. Because avalanche slip statistics is a scale-free theory and it is expected to apply in all systems that belong to this universality class20, these results may be applicable to understanding how other layered material systems behave when exposed to uncontrolled, potentially chemically hostile environments. As an additional consequence of the model’s scale-free nature, it can extend the toolbox available to analyze displacement bursts in nanoindentation by using insights obtained from other length scales. Furthermore, though previous studies have utilized chemical kinetics to examine fractures in silicates, the analysis methodology of avalanche slip statistics offers a physical, detail-independent framework for examining similar phenomena in layered, anisotropic materials17,28. As such, the results here should be applicable to a wide range of systems, for example in identifying the mechanical properties of a thin-film coating.

Future studies will examine whether the results obtained in this work can be universally applied to other anisotropic layered materials48,49. Additionally, in-situ AFM measurements performed in conjunction with similar tests may reveal how the kinetic parameters of pressurized muscovite dissolution may change with environmental pH and stress under the tip.

Methods

Mica preparation

Lab-manufactured muscovite mica with a lateral area of 1.5 cm2 and a thickness of 270 μm from MTI Corporation was used in these experiments. Indentations were completed with a Hysitron TriboIndenter 900 equipped with a Berkovich tip. Indentation load \(P\), depth \(h\), and time \(t\) were tracked at a data acquisition rate of 200 Hz. The surface of the sample was defined as the position of the tip at which the load increased beyond the software-defined setpoint; for our measurements, this load level was 2 \(\mu N\). We also assume that the surface is defined by the first 2:1 Si-O-Si layer exposed to the environment. All indentation data were manually inspected for false engagements from surface contaminants or hydrodynamic effects. As discussed previously13, the contact area function depends purely on the contact depth as \({A}_{c}\left({h}_{c}\right)={C}_{o}{h}_{c}^{2}+{C}_{1}{h}_{c}^{1}+{C}_{2}{h}_{c}^{1/2}+{C}_{3}{h}_{C}^{1/4}+{C}_{4}{h}_{c}^{1/8}+{C}_{5}{h}_{c}^{1/16}\), where \({C}_{o}\) through \({C}_{5}\) are coefficients related to tip shape and are calibrated using fused silica as a reference material. The values of \({C}_{o}\) through \({C}_{5}\) used are shared in Source Data. Notably, because the contact area function only depends on contact depth and not tip velocity, the size or frequency of pop-ins are not expected to influence its accuracy. Indentation was performed at a fixed nanoindentation strain rate of 0.1 \({s}^{-1}\) by setting the loading rate \({dP}/{dt}=\dot{P}\) to follow \((\dot{P}/P)=0.2\,{s}^{-1}\) 50 to a maximum load of 10 mN. The indenter was then held for 5 seconds at maximum load before a 5 second unload. Different samples were used for each of the three environmental conditions, with dry indents performed on each sample as a control where the environment is controlled to have less than 30% humidity to minimize the effect of environmental moisture29. Analysis of the control tests are shown in Supplementary Discussion 7. Indentations were performed at least 4 mm away from the sample edge to avoid any material edge effects. As discussed in ref. 13, the z-axis tip calibration for the wet condition tests were performed while 99% of the tip was submerged to account for buoyancy and surface tension effects51. Wet condition indentations were all performed within 12 h of submersing the mica into aqueous solutions and were otherwise identical to the dry condition tests. The DI water sample was exposed to deionized water, the pH 9.8 sample to a 0.1 M NaCl solution with pH adjusted to pH 9.8 with NaOH, and the pH 12 sample to a 0.1 M NaCl solution with pH adjusted to pH 12 with NaOH. The results in the main text are generated from 115 indents in the dry condition, 114 in the DI condition, 118 in the pH 9.8, and 117 in the pH 12. Load-displacement traces for all indents used for our analysis are shown in Supplementary Discussion 5.

Avalanche simulation details

The simulation system comprises many cells gradually loaded at a fixed loading rate. Cells build stress until they reach a critical stress level, at which point that cell’s stress is uniformly distributed to the rest of the system. A fraction of each relaxed stress is distributed to the boundaries of the system to account for stress relaxation via system deformation20,52. The distributed stress can cause other cells to fail on the next timestep, resulting in avalanches. The system weakening \(\varepsilon\) is varied between 0 and 1 and controls how easily a failed cell fails again during the same avalanche20,52. As such, systems with high weakening are more prone to runaway avalanches that span the entirety of the system20,45. The total stress in the system is tracked and saved to a time trace. Avalanches begin when a single cell fails and end when no further failures occur. Further details of the simulation can be found in Supplementary Discussion 1.

Statistical analysis and plot generation

Unless otherwise specified in the text, all reported confidence intervals are 95% confidence intervals generated using bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrapping from SciPy’s built-in bootstrapping function53. All plots are generated in Python using Matplotlib54. Data vectors are manipulated using Numpy55.

Data availability

The nanoindentation data used to generate these results can be found at https://foundry.openei.org/268. The source data necessary to generate these plots and those in the Supplementary Information are included in Source Data.

References

Westwood, A. R. C., Ahearn, J. S. & Mills, J. J. Developments in the theory and application of chemomechanical effects. Colloids Surf. 2, 1–35 (1981).

Rimsza, J. & Ilgen, A. Water weakening of calcium oxide. J. Phys. Chem. C. 126, 9493–9501 (2022).

Feucht, L. J. & Logan, J. M. Effects of chemically active solutions on shearing behavior of a sandstone. Tectonophysics 175, 159–176 (1990).

Duda, M. & Renner, J. The weakening effect of water on the brittle failure strength of sandstone. Geophys. J. Int. 192, 1091–1108 (2013).

Mares, V. M. & Kronenberg, A. K. Experimental deformation of muscovite. J. Struct. Geol. 15, 1061–1075 (1993).

Nesbitt, H. W. & Young, G. M. Prediction of some weathering trends of plutonic and volcanic rocks based on thermodynamic and kinetic considerations. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 48, 1523–1534 (1984).

De Poel, W. et al. Muscovite mica: Flatter than a pancake. Surf. Sci. 619, 19–24 (2014).

Arif, M., Al-Yaseri, A. Z., Barifcani, A., Lebedev, M. & Iglauer, S. Impact of pressure and temperature on CO2–brine–mica contact angles and CO2–brine interfacial tension: Implications for carbon geo-sequestration. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 462, 208–215 (2016).

Vater, P., Tress, G., Brandt, R., Genswürger, B. & Spohr, R. Nuclear track microfilters made of mica. Nucl. Instrum. Methods 173, 205–210 (1980).

Armbruster, M. H. & Austin, J. B. The adsorption of gases on plane surfaces of mica. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 60, 467–475 (1938).

Ben Aziza, Z., Zhang, Q. & Baillargeat, D. Graphene/mica based ammonia gas sensors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 254102 (2014).

Wang, D. et al. A mica filter enables bacterial enrichment from large volumes of natural water for sensitive monitoring of pathogens by nanopore sequencing. J. Hazard. Mater. 472, 134495 (2024).

Mook, W. M., Ilgen, A. G., Jungjohann, K. L. & DelRio, F. W. Chemomechanical weakening of muscovite quantified with in situ liquid nanoindentation. J. Mater. Sci. 57, 10059–10071 (2022).

Maslova, M. V., Gerasimova, L. G. & Forsling, W. Surface properties of cleaved mica. Colloid J. 66, 322–328 (2004).

Rimsza, J. M., Jones, R. E. & Criscenti, L. J. Chemical effects on subcritical fracture in silica from molecular dynamics simulations. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 123, 9341–9354 (2018).

Van Vliet, K. J. Chemomechanics of complex materials: challenges and opportunities in predictive kinetic timescales. in Scientific Modeling and Simulations (eds. Yip, S. & de la Rubia, T. D.) 67–80 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-9741-6_7.

Dove, P. M. Geochemical controls on the kinetics of quartz fracture at subcritical tensile stresses. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 100, 22349–22359 (1995).

Sethna, J. P., Dahmen, K. A. & Myers, C. R. Crackling noise. Nature 410, 242–250 (2001).

Dahmen, K. A. Mean field theory of slip statistics. in Avalanches in Functional Materials and Geophysics (eds. Salje, E. K. H., Saxena, A. & Planes, A.) 19–30 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-45612-6_2.

Dahmen, K. A., Ben-Zion, Y. & Uhl, J. T. Micromechanical model for deformation in solids with universal predictions for stress-strain curves and slip avalanches. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 175501 (2009).

Coleman, J. P. et al. Effect of annealing on nanoindentation slips in a bulk metallic glass. Phys. Rev. B 96, 134117 (2017).

Antonaglia, J. et al. Bulk metallic glasses deform via slip avalanches. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 155501 (2014).

Sheikh, M. A., Weaver, R. L. & Dahmen, K. A. Avalanche statistics identify intrinsic stellar processes near criticality in KIC 8462852. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 261101 (2016).

Friedman, N. et al. Universal critical dynamics in high resolution neuronal avalanche data. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 208102 (2012).

Uhl, J. T. et al. Universal quake statistics: From compressed nanocrystals to earthquakes. Sci. Rep. 5, 16493 (2015).

Ferraris, G. & Ivaldi, G. Structural features of micas. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 46, 117–153 (2002).

Richardson, S. M. & Richardson, J. W. Crystal structure of a pink muscovite from Archer’s Post, Kenya: Implications for reverse pleochroism in dioctahedral micas. Am. Mineral. 67, 69–75 (1982).

Knauss, K. G. & Thomas J, W. Muscovite dissolution kinetics as a function of pH and time at 70 °C. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 53, 1493–1501 (1989).

Cantrell & Ewing, G. E. Thin film water on muscovite mica. J. Phys. Chem. B 105, 5434–5439 (2001).

Long, A. A. et al. From critical behavior to catastrophic runaways: Comparing sheared granular materials with bulk metallic glasses. Granul. Matter 21, 99 (2019).

Meike, A. In situ deformation of micas: a high-voltage electron-microscope study. Am. Mineral. 74, 780–796 (1989).

Zhang, J. et al. Effects of interlayer interactions on the nanoindentation behavior and hardness of 2:1 phyllosilicates. Appl. Clay Sci. 80–81, 267–280 (2013).

LeBlanc, M. et al. Avalanche statistics from data with low time resolution. Phys. Rev. E 94, 052135 (2016).

LeBlanc, M., Angheluta, L., Dahmen, K. & Goldenfeld, N. Universal fluctuations and extreme statistics of avalanches near the depinning transition. Phys. Rev. E 87, 022126 (2013).

Zapperi, S., Cizeau, P., Durin, G. & Stanley, H. E. Dynamics of a ferromagnetic domain wall: Avalanches, depinning transition and the Barkhausen effect. Phys. Rev. B 58, 6353–6366 (1998).

Dahmen, K., Ertaş, D. & Ben-Zion, Y. Gutenberg-Richter and characteristic earthquake behavior in simple mean-field models of heterogeneous faults. Phys. Rev. E 58, 1494–1501 (1998).

Sparks, G. & Maaß, R. Nontrivial scaling exponents of dislocation avalanches in microplasticity. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2, 120601 (2018).

Antonaglia, J. et al. Tuned critical avalanche scaling in bulk metallic glasses. Sci. Rep. 4, 4382 (2014).

Wright, W. J. et al. Experimental evidence for both progressive and simultaneous shear during quasistatic compression of a bulk metallic glass. J. Appl. Phys. 119, 084908 (2016).

Friedman, N. et al. Statistics of dislocation slip avalanches in nanosized single crystals show tuned critical behavior predicted by a simple mean field model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 095507 (2012).

Barsoum, M. W., Murugaiah, A., Kalidindi, S. R. & Zhen, T. Kinking nonlinear elastic solids, nanoindentations, and geology. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 255508 (2004).

Zhang, G., Wei, Z. & Ferrell, R. E. Elastic modulus and hardness of muscovite and rectorite determined by nanoindentation. Appl. Clay Sci. 43, 271–281 (2009).

Fraysse, K. S. et al. Frequency dependent silica dissolution rate enhancement under oscillating pressure via an electrochemical pressure solution-like, surface resonance mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 3875–3891 (2022).

White, R. A. & Dahmen, K. A. Driving rate effects on crackling noise. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 085702 (2003).

Wright, W. J. et al. Slip statistics for a bulk metallic glass composite reflect its ductility. J. Appl. Phys. 124, 185101 (2018).

Meng, L., Qiu, J., Wang, Z., Liu, E. & Shu, X. Indentation pop-in behavior of CoCrFeNiAl0.3 high-entropy alloy. Mater. Res. Expr. 6, 1265d4 (2019).

Shim, S., Bei, H., George, E. P. & Pharr, G. M. A different type of indentation size effect. Scr. Mater. 59, 1095–1098 (2008).

Ohmura, T. & Wakeda, M. Pop-in phenomenon as a fundamental plasticity probed by nanoindentation technique. Materials 14, 1879 (2021).

Liang, D. D. et al. Sliding tribocorrosion behavior of Fe-based bulk metallic glass under corrosive environments. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 510, 62–70 (2019).

Lucas, B. N., Oliver, W. C., Pharr, G. M. & Loubet, J. L. Time dependent deformation during indentation testing. MRS Online Proc. Libr. OPL 436, 233 (1996).

Gauthier, M. & Nourine, M. Capillary force disturbances on a partially submerged cylindrical micromanipulator. IEEE Trans. Robot. 23, 600–604 (2007).

Mehta, A. P., Dahmen, K. A. & Ben-Zion, Y. Universal mean moment rate profiles of earthquake ruptures. Phys. Rev. E 73, 056104 (2006).

Virtanen, P. et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 17, 261–272 (2020).

Hunter, J. D. Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 9, 90–95 (2007).

Harris et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 585, 357–362 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank Manny Rubio who helped draft Fig. 1. We also thank Scott Cilke and Brenda Wilson for their support through the Sandia University Partnerships network connection with the University of Illinois. This work was supported by the Laboratory Directed Research and Development program at Sandia National Laboratories (Project # 233080). This article has been co-authored by the employees of National Technology & Engineering Solutions of Sandia, LLC under Contract No. DE-NA0003525 with the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). The employees own all rights, title and interest in and to the article and are responsible for its contents. The United States Government retains and the publisher, by accepting the article for publication, acknowledges that the United States Government retains a non-exclusive, paid-up, irrevocable, world-wide license to publish or reproduce the published form of this article or allow others to do so, for United States Government purposes. The DOE will provide public access to these results of federally sponsored research in accordance with the DOE Public Access Plan https://www.energy.gov/downloads/doe-public-access-plan. This paper describes objective technical results and analysis. Any subjective views or opinions that might be expressed in the paper do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Energy or the United States Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.J.S. performed the statistical analysis, created the figures, and drafted the manuscript. K.A.D. oversaw the statistical analysis and assisted with manuscript preparation. A.G.I. assisted with manuscript preparation and oversaw the manufacture and indentation of the mica samples. W.M.M. performed the indentations and assisted with manuscript preparation. F.W.D. assisted with manuscript preparation and interpretation of results W.J.W. assisted with manuscript preparation and the statistical analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Barton Prorok, Guoping Zhang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sickle, J.J., Mook, W.M., DelRio, F.W. et al. Quantifying chemomechanical weakening in muscovite mica with a simple micromechanical model. Nat Commun 15, 9552 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53213-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53213-5