Abstract

The Challenger Deep (CD) is the deepest known hadal trench in the world. Due to challenges in data sampling at extreme ocean depths, the Lower Circumpolar Deep Water (LCDW) transport and ocean circulation structure in the CD remain unclear. By analyzing data from an extra-deep current meter mooring array, here we find a three-layer circulation in the CD, transitioning downward from westward LCDW flow (about −1.866 ± 2.953 Sv, 1 Sv = 106 m3/s) to cyclonic circulation, and then to anticyclonic circulation. The westward flow reverses its direction during summer, giving evidence for bidirectional connectivity of deep-sea basins, while the cyclonic-anticyclonic circulation is relatively steady. The LCDW intrusion, local topography and turbulent mixing are crucial for modulating the three-layer circulation. Turbulent mixing plays a key role in driving the anticyclonic circulation. Our findings provide insights for understanding the hydrodynamic environment in the ocean’s deepest areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

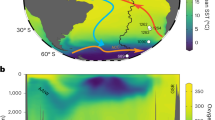

Hadal trenches refer to the deepest regions of the ocean (≥6000 m depth) and have a long, narrow V-shaped topography. Due to topographic constraints, hadal trenches have unique hydrological, geological and biological characteristics, and play an important role in the Earth system1,2,3. These zones remain some of the least explored habitats on Earth due to the technological challenges of sampling in an extremely high-pressure environment. The Challenger Deep (CD) is the deepest hadal trench on Earth, located at the southern end of the Mariana Trench in the western Pacific Ocean (Fig. 1). It is the only channel below 4000 m depth that connects the East Mariana Basin and semi-enclosed basins, such as the West Mariana Basin and West Caroline Basin. Although the isobaths below 6000 m depth are relatively closed, the vertical transport driven by the cyclonic circulation4 and the strong turbulent mixing5 ventilates the enclosed hadal trench, exchanging the abyssal waters over the trench. Therefore, the deep circulation of the CD not only acts as a crucial component of the Pacific deep circulation6 but also dominates the distribution of abyssal and hadal water and impacts the trench environment7,8. Presently, the deep circulation in the CD is still uncertain and its dynamics remain to be understood.

Topographic data is from 1 Arc-Minute Global Relief Model (ETOPO1). The inset provides a closer view of the Challenger Deep, Mariana Trench. Red curves with arrows indicate schematic pathways of Lower Circumpolar Deep Water (LCDW) below about 3500 m (based on ref. 6), and the black stars in the inset denote mooring locations named M1–M4 from south to north. WMB West Mariana Basin, EMB East Mariana Basin, WCB West Caroline Basin, ECB East Caroline Basin, MT Mariana Trench. Source data are provided with this paper.

In the abyssal Pacific Ocean, the Deep Western Boundary Current (DWBC) carries cold, saline, oxygen-rich and nutrient-poor Lower Circumpolar Deep Water (LCDW) along topographically-guided pathways from the Southern Ocean into the North Pacific Ocean (Fig. 1). After a long journey, the DWBC divides into two parts at the entrance of the CD: a small part that turns east and enters the East Caroline Basin and Melanesian Basin, and the main portion that runs west through the CD, arriving at the West Mariana Basin and West Caroline Basin after passing the Yap-Mariana Junction and Yap Trench, respectively9,10,11,12,13.

The LCDW volume transport through the CD is still uncertain. Previous estimates of the LCDW transport were based on geostrophic calculations using conductivity-temperature-depth (CTD) profiles and limited current measurements. The previous estimates based on CTD profiles suggested that roughly −0.3 Sv LCDW entered the trench14, −0.55 Sv LCDW flowed westward at 145°E near the entrance of the trench10, and −1.29 Sv LCDW flowed westward within the trench7. Direct current measurements were used to estimate the LCDW transport in the downstream passage, including the Yap-Mariana Junction (northward 0.36 Sv in ref. 10; 1.27 ± 1.23 Sv in ref. 12; 2.1 ± 1.23 Sv in ref. 13), the Yap Trench (northward 0.42 ± 1.88 Sv in ref. 12) and the sill west of the CD (westward −2.43 ± 2.56 Sv in ref. 12; −2.2 ± 1.0 Sv in ref. 13). These results suggested large uncertainties in the LCDW transport in this region. In addition, previous sparse direct current measurements were incapable of estimating the LCDW transport in the CD15. Unfortunately, there are still no direct and sustained current measurements available to quantify the LCDW transport through the CD.

A cyclonic circulation caused by momentum balance3 has been found in many hadal trenches along the DWBC pathway, including the Yap9, Kermadec16, Izu-Bonin17, Japan18, Kuril-Kamchatka19, and Aleutian Trenches20,21. Geostrophic flows derived from sparse CTD profiles showed a cyclonic circulation at pressures between 3000 and 7000 dbar in the CD4,22. However, high-resolution hydrologic and direct current measurements suggested that a westward flow caused by the LCDW intrusion dominated the deep layer of the CD7,15. Given this, the circulation structures and dynamics in the CD are still under debate.

Turbulent mixing in the deep ocean is essential for maintaining the present stratification and shaping the global overturning circulation23,24. Much observational evidence indicated that turbulent mixing is enhanced by 2-3 orders of magnitude toward the rough ocean bottom25,26. The bottom intensification of turbulent mixing indicates the divergence of turbulent buoyancy flux in the stratified mixed layer (SML) overlying the ocean bottom boundary layer (BBL), thus driving a sinking of deep water27,28. To satisfy the zero-flux condition at the seafloor, the turbulent flux decrease from a maximum value at the top of the BBL to zero at the seafloor, implying an upwelling motion in the BBL induced by the bottom convergence of turbulent flux29,30,31. Bottom-intensified turbulent mixing has been found in the CD5,22. In the ocean bottom, tidal energy is one of the most important energy sources for turbulent mixing32. A model simulation of internal tides for the Mariana Trench reproduced the bottom-intensified diapycnal mixing well33. Hence, tidal-induced turbulent mixing could drive upwelling (downwelling) motions in (above) the BBL and modulate the deep circulation in the trench.

To better understand the deep circulation in the CD, four extra-deep current meter moorings were deployed in the trench for ~14 months (Fig. 1, mooring array details in Methods section). This study used these mooring observations to investigate the structure of the deep circulation, the LCDW volume transport, and their seasonal variation. Furthermore, two numerical experiments, configured with/without tidal-induced turbulent mixing, were carried out to explore tidal modulations of deep circulation. In this study, we find a three-layer circulation in the CD, transitioning downward from westward LCDW flow to cyclonic circulation, and then to anticyclonic circulation. The structure of three-layer circulation is attributed to the LCDW intrusion, local topography and turbulent mixing.

Results

Three-layer circulation in the CD

The velocity direction at the four moorings is primarily along the trench bathymetry (orientated approximately east/west) due to topographic constraints, therefore the zonal velocity component was used for analysis. To delineate the mean current patterns, the current meter data were interpolated to the entire transect. Before the interpolation, we gridded the transect at a vertical resolution of 10 m and a meridional resolution of 110 m, and assumed that the currents at the bottom and two side walls had zero velocity. The gridded zonal velocity below 3591 m was acquired using natural neighbor interpolation34. Above 6000 m depth, the annual-mean velocity shows a prevailing westward flow (Fig. 2), with a maximum velocity of ~3.1 cm s−1 recorded at 3660 m of M4. This strong current potentially transports organic-matter, other nutrients and oxygen, and marine life into the trench area8,35. Note that a weak countercurrent with a velocity of ~0.3 cm s−1 appeared at 3934 m of M2, and the westward velocities beneath this countercurrent were faint (no more than 0.2 cm s−1). This countercurrent has the largest standard deviation reaching ~7.5 cm s−1 (Fig. 2b), indicating a significant temporal variation of the flow at this position. A hydrologic survey also found this weak backflow within 3000–5000 m depth at the south slope of the CD7.

a–d Vertical profiles of east-west component (u) at the four moorings from M1 to M4. Circles indicate the mean values of the year 2016. Error bars are shown as horizontal lines extending left and right from each data point, representing the standard deviations. e Interpolated deep flow through the mooring transect (142.5°E) and potential temperature distribution below 3600 m. Black dots stand for the observational positions on mooring stations. Color shading indicates the annual mean zonal velocity and the positive (negative) velocity represents the eastward (westward) flow. Black lines represent the isolines of velocity, gray lines show isotherms of potential temperature. The gray region represents the bottom topography. Source data are provided with this paper.

Below 6000 m depth, the currents are weak, with mean speeds everywhere less than 1.0 cm s−1 and standard deviations less than 1.6 cm s−1 (Fig. 2b, c). A cyclonic sense of circulation is found between 6000 and 7500 m depth where a relatively strong eastward flow with a core speed reaching 0.75 cm s−1 appeared over the south slope of the CD (Fig. 2e). Meanwhile, the isotherm of 1.0135 °C clearly indicates a warm center that coincides with the area of eastward flow. Previous direct measurement in the CD15 did not detect this circulation due to unfortunate positioning (Supplementary Fig. 1S). An unexpected result shows up that a westward (about 0.5 cm s−1 at 8001 m of M2) and eastward (about 0.3 cm s−1 at 8313 m of M3) flows occurred at the south and north slopes, implying a weak anticyclonic sense of circulation at the bottom layer of the CD. Remarkably, this phenomenon disobeys the classic theory of circulation in an enclosed basin3, as detailed in the Discussion section.

LCDW transport through the CD

The 1.2 °C (potential temperature, θ1.2) isotherm is conventionally used as the upper interface of the LCDW36. Its depth varied from 3600 m to 3900 m during our observational period (thin magenta line in Fig. 3), indicating high variability in LCDW transport. The LCDW transport was calculated by integrating zonal velocity from the isotherm of θ1.2 to the bottom along the transect. The annual-mean LCDW transport reached −1.866 ± 2.953 Sv (negative sign represents westward direction), which is comparable with recent observations7,12,13. The daily LCDW transport shows large fluctuations in the annual cycle, ranging from −10.0 to 6.0 Sv. It decreases from a large (winter) to small (spring) westward transport, then converts to eastward transport (summer), and finally returns to westward transport (autumn and winter). This seasonal variation is consistent with the LCDW transport observed in the Yap-Mariana Junction and the sill west of the trench12,13. Besides the seasonal variation, intra-seasonal (peak at 61 days) and sub-seasonal (peaks at 6, 8, 10, 16, 22 days) variations were found in the power spectra of daily LCDW transport (Supplementary Fig. S2). Previous observations also captured intra-seasonal and sub-seasonal variations in the trench15 and the Yap-Mariana Junction37. By bandpass filtering the daily LCDW transport, we found that the variance contributions of the seasonal (>90 days), intra-seasonal (30–90 days) and sub-seasonal (4 to 30 days) bands were 64.53%, 11.51% and 10.99%, respectively.

Time series of volume transport below isotherm θ = 1.2 °C across the mooring transect (blue lines), dissolved oxygen at depth 3597 m of M1 (purple lines), and depth of the isotherm θ = 1.2 °C (pink lines). The thin lines represent daily series, thick lines are 24-day Butterworth lowpass filtered series. Light blue background indicates the period with eastward transport. Unshaded background indicates the period with westward transport. The positive (negative) value of transport stands for eastward (westward) transport. Source data are provided with this paper.

The 24-day lowpass filtered series were used to further analyze the seasonal variation (thick lines in Fig. 3). The depth of the θ1.2 isotherm, and the dissolved oxygen (DO) values at 3591 m of M1, show significant correlation with the LCDW transport. The variation of θ1.2 depth is well correlated with the DO. The correlation coefficients are 0.5419 (θ1.2 depth and LCDW transport), −0.6899 (DO and LCDW transport), and −0.8621 (DO and θ1.2 depth). This matching relationship is explained by the LCDW intrusion carrying high-DO and low-temperature water into the CD that oxygenates and cools the local deep water10. On the contrary, when LCDW intrusion weakens or even reverses its direction, the local deep water recovers low DO and high temperature. Corresponding to the seasonal variation of the LCDW transport, the structure of the deep circulation varied significantly from January to December (Supplementary Fig. S3).

To compare circulation structures during different LCDW intrusion conditions in the CD, time-averaged velocities under net westward/eastward (unshaded/shaded background in Fig. 3) transport periods were calculated and plotted in Fig. 4. Above 6000 m depth, the LCDW transport dominated the circulation structure and flow intensity. The periods of westward transport showed an almost complete westward flow, enhanced toward the north slope of the CD. The period of eastward transport showed a mixture of eastward and westward flows, with strong eastward flows over the lower south slope and weak westward flows elsewhere. Below 6000 m depth, the LCDW intrusion had weak effects on the circulation structure; the cyclonic-anticyclonic circulation structure was maintained steadily at each depth layer.

a Fields averaged over the periods with westward transport (shown in Fig. 3). b As in a, but over the peirods with eastward transports. Black dots stand for the observational positions on mooring stations, black lines represent the isolines of velocity gray lines show isotherms. The positive (negative) velocity represents the eastward (westward) flow, and the gray region shows the bottom topography. Source data are provided with this paper.

Discussion

Our estimate of LCDW transport (annual-mean −1.866 ± 2.953 Sv) is larger than most previous estimates. For example, the geostrophic transports of approximately −0.3 Sv LCDW passed through the trench14, −0.55 Sv LCDW appeared at the entrance of the trench10, and a geostrophic transport of −1.29 Sv LCDW crossed a transect at the CD7. Given the large uncertainties related to the choice of reference level used for the geostrophic current and the choice of the observation moment, differences in momentary estimated geostrophic transports in these studies are expected. Recent mooring observations from November 2017 to March 2019 revealed a transport of −2.2 ± 1 Sv LCDW through the sill at the exit of the trench13. Additionally, mooring observations from December 2018 to December 2019 revealed a transport of −2.43 ± 2.56 Sv LCDW through the sill12. The choice of the observation period will also result in different estimates.

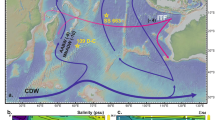

The seasonal reversal of the LCDW has been found in many recent observations at passages adjacent to the trench11,12,13. This reversal was attributed to the seasonal intrusion of upstream LCDW and the pressure gradient between the East Mariana Basin and the West Caroline Basin11,12. To elucidate the drivers behind this reversal, we analyzed the GLORYS12V1 reanalysis dataset from the European Union Copernicus Marine Service (Supplementary Fig. S4). GLORYS12V1 reproduced the seasonal variation of LCDW transport well, with a correlation coefficient of 0.67 between GLORYS12V1 and observations, and a variance contribution of the annual cycle at 49%. Monthly LCDW transports at the entrance, center and exit of the trench showed a consistent seasonal variation, with reversals occurring from May to October between 1993 and 2023. The pressure difference in deep layers between the entrance and exit of the trench matches the reversal of LCDW transports well, with a correlation coefficient of −0.60 between the LCDW transport at the exit and the pressure difference at 3993 m depth. Seasonal reversals in the pressure difference were observed at depths ranging from 3000 m to 4500 m (Supplementary Fig. S4f). Similarly, the numerical experiment TMCD-MBF (see the Methods section) was conducted to examine the influence of seasonal intrusions of upstream LCDW. The modeled LCDW transport exhibited a significant annual cycle and a small reversal (Supplementary Fig. S5), suggesting importance of the seasonal intrusion of upstream LCDW. Observed reversal times were from June to November during 2014–2018 and from July to October in 2019 at the Yap-Mariana Junction, from June to October during 2018–2019 at the exit of the trench11,12,13, and from June to August in 2016 at the center of the trench (result in this paper). The differing reversal times observed may be attributed to intraseasonal variability superimposed on seasonal variations, or to the interannual variability of the LCDW transport.

Above 6000 m depth, the intensified westward flow to the north and the weak backflow (eastward flow) over the south slope of the trench could be attributed to the superimposition of the westward LCDW flow and the counterclockwise circulation driven by the PV (potential vorticity) balance. The PV balance is between the PV inflow across the open boundaries and the PV dissipation along the inner topography boundaries38,39. The net PV inflow is due to the inflow at the entrance of the trench having a larger planetary vorticity than the outflow at the exit. The PV integral constraint was also used to elucidate the LCDW flows toward the Philippine Sea on the western side of the Yap-Mariana Junction13. Additionally, a similar flow pattern was found at the northern boundary of the North Pacific, which was attributed to the bottom slope increasing northward20. The similar meridional variation of bottom slope in the trench may also contribute to the flow pattern above 6000 m depth.

Bounded by a closed geostrophic contour, trench circulation is usually diagnosed as a cyclonic circulation following a simple integration of momentum balance over the region3,40. This simple integration neglects one crucial dynamic factor, i.e., turbulent mixing near the ocean bottom layer. Recent studies have found intensified turbulent mixing above rough topography in the trench5,22. In the steep and enclosed topography, the turbulent mixing could affect the circulation system by driving benthic vertical motions29,30. Presently, the dynamic mechanism for modulating the deep circulation in the trench is still unclear. In this section, we discuss the impact of tidal-induced turbulent mixing on modulating deep circulation in the CD based on numerical model experiments NoTM and TMCD (see the Methods section).

In the NoTM case, the westward LCDW flow dominated the CD above 6000 m depth, with a backflow over the south slope (Fig. 5a). Below that, a weak cyclonic sense of circulation occupied the whole deep CD (Figs. 5b and 6c, f, i, l). Anticyclonic circulation was not found under this case. Meanwhile, water-mass properties showed an east-west structure (Fig. 6a, b, d, e, g, h, j, k), which was caused by weak advection at these depths7. At a depth of 6500 m, the cold and salty water appearing in the western part of the trench could be attributed to the LCDW uplift after impinging on the western boundary. Therefore, the experiment NoTM, considering background circulation and topography without tidal-induced turbulent mixing, can reproduce a westward flow and a faint cyclonic sense of circulation in the trench.

a Annual mean zonal velcotiy resulting from experiment NoTM. b As in a, but from experiment TMCD. Black lines represent the isolines of velocity and the positive (negative) velocity represents the eastward (westward) flow. The gray region shows the bottom topography. NoTM the numerical experiment without tidal-induced turbulent mixing, TMCD the numerical experiment with tidal-induced turbulent mixing in the Challenger Deep. Source data are provided with this paper.

Horizontal distributions of potential temperature (θ), salinity (S), potential density (σ0) and flow (vector arrows) at depth 6500 (a–c), 7500 (d–f), 8000 (g–i) and 9000 (j–l) m. Gray lines indicate 6000 m isobaths. NoTM: the numerical experiment without tidal-induced turbulent mixing. Source data are provided with this paper.

With tidal-induced turbulent mixing in the TMCD case, the trench circulation was enhanced (Fig. 5b), and its magnitude was comparable to observations in Fig. 2e. The cyclonic-anticyclonic circulation was reproduced well in the deep CD (Fig. 7c, f, i, l) under the TMCD condition. And water mass with cold-salty-dense (Fig. 7a, b) and warm-fresh-light (Fig. 7g, h, j, k) cores following the thermal wind relation displayed the cyclonic and anticyclonic senses of circulation. The area-averaged vertical velocity and vorticity profiles (Fig. 7m) indicated that the upwelling/downwelling corresponded well to cyclonic/anticyclonic circulations in the CD due to the conservation law of potential vorticity. The upwelling shifted to downwelling at ~6700 m depth, which matches well with the transition depth of cyclonic circulation shifting to anticyclonic circulation (Fig. 5b). Above 6000 m depth, the vertical velocity was not coupled with the vorticity, suggesting more complicated dynamics in the westward flow. At 7500 m depth, the distribution of temperature, salinity and density did not conform to the thermal wind relation (Fig. 7d, e), which may be attributed to complicated dynamics near the transition depth, such as the vertical shear, baroclinic instability and enhanced mixing.

Horizontal distributions of potential temperature (θ), salinity (S), potential density (σ0) and flow (vector arrows) at depths 6500 (a–c), 7500 (d–f), 8000 (g–i) and 9000 (j–l) m. Gray lines indicate 6000 m isobaths. In m, the w and ζ represents area averaged vertical velocity and vorticity over the trench, respectivity. The area ranges from 142° to 143° in longitude and from 10.5° to 12° in latitude. TMCD: the numerical experiment with tidal-induced turbulent mixing in the Challenger Deep. Source data are provided with this paper.

Our observations suggest a three-layer circulation in the CD, which can be reproduced well by numerical experiment once the LCDW intrusion, topography and tidal-induced mixing are considered. Figure 8 is a schematic map of the deep circulation mechanism in the CD. The strong westward flow above 6000 m is driven by the LCDW intrusion. The cyclonic-anticyclonic circulation below 6000 m is mainly forced by topography and tidal-induced turbulent mixing. The bottom-intensified mixing can drive upslope (downslope) flow in the BBL (SML). The vertical motion in the inner zone compensates for the net vertical transport near the bottom boundary. Based on the conservation of potential vorticity, the upwelling (downwelling) of the inner zone will force the cyclonic (anticyclonic) circulation in the enclosed trench. Therefore, tidal-induced turbulent mixing is important for driving the anticyclonic circulation at the bottom of the trench.

It shows westward flow driven by LCDW intrusion (from 3600 to 6000 m), cyclonic circulation driven by upwelling and topography (6000–6700 m), and anticyclonic circulation driven by downwelling and topography (below 6700 m). The anticlockwise (clockwise) white curve with an arrow indicates the cyclonic (anticyclonic) circulation. The white solid arrows display downwelling and upwelling in the inner area. The shaking red (blue) curves with arrows show the net upslope (downslope) motion driven by tidal-induced mixing. The dotted white arrows show the attendant transport, closing the vertical circulation loop. Black spirals indicate the vertical mixing process near the bottom. The shaking yellow curves with arrows show the internal tides near the bottom. The upwelling and downwelling are modulated by bottom intensified mixing. LCDW: Lower Circumpolar Deep Water. Source data are provided with this paper.

Methods

Mooring dataset

Four current meter moorings named M1–M4 were deployed in January 2016 to directly observe the deep flow at the CD (Fig. 1). The moorings along the transect at 142.5°E formed a meridional array across the CD from the south slope (M1 and M2) to north slope (M3 and M4). The bottom depths at M1–M4 are 5690, 8226, 8599, and 5842 m, respectively. These moorings were equipped with single-point acoustic current meters (Seaguard RCM DW and Nortek Aquadopp 6000 m) and CTDs (SBE 37-SM and SBE 16plus) from a depth of about 3600 m to near the seafloor with a vertical interval of ~1000 m. The detailed configuration of these moorings is listed in Supplementary Table S1 and the diagram of moorings is shown in Supplementary Fig. S1. Current meters recorded point velocity with a sample interval of 30 min. On the Mooring M1, the current meter at depth 3591 m contained a DO sensor and sampled oxygen concentration every 30 min as well. CTDs measured temperature, salinity and pressure every 10 min. The accuracy of velocity and DO are ±1% and ±5% of measured value, respectively. The data accuracy of the SBE 37-SM (SBE 16plus) is 0.002 °C (0.005 °C) for temperature and 0.0003 S m−1 (0.0005 S m−1) for conductivity. The bias of temperature and salinity is not negligible in comparison with the minor spatiotemporal variation magnitude of water mass in the hadal trench. We referred to the correction method proposed in previous studies41,42,43,44 to address temperature and salinity correction in our mooring observations. Detailed steps for the correction are in the Supplementary Note S1. All observed variables are averaged to daily means. The mooring array was recovered in February 2017, obtaining current, temperature, salinity and DO records for ~14 months. One-year mooring data from January 5, 2016 to January 4, 2017 were selected to analyze the deep flow and water properties below ~3600 m in the CD.

Numerical experiment configurations

A regional circulation model applied in this study is based on the Massachusetts Institute of Technology General Circulation Model (MITgcm)45. The model domain ranges from 9° to 16°N in latitude and from 138° to 149°E in longitude, covering the southern part of the Mariana Trench, northern part of the Yap Trench and part of the West Mariana Basin and East Mariana Basin (Supplementary Fig. S6a). The model uses spherical polar coordinates and sets the horizontal resolution as 1/24° × 1/24°. The water column is divided vertically into 112 levels, with thickness gradually increasing from 10 to 50 m in the upper 100 m and a constant thickness of 100 m from 100-10,800 m water depth (Supplementary Fig. S6b).

The model topography is extracted from the General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO_08) bathymetry data (http://www.gebco.net/) with a resolution of 30 arc-seconds. The initial temperature and salinity fields are derived from a combination of the World Ocean Atlas 2018 (WOA18) climatology and a CTD profile at the CD46. The WOA18 climatological temperature and salinity with 1/4° × 1/4° resolution have 102 levels within 0–5500 m water depth. The CTD profile was measured by the German R/V Sonne near the world’s deepest point, with the deepest measurement at 10,851 m (Supplementary Fig. S6c–e). The two datasets are coupled and interpolated by using linear interpolation into the 112 levels of the model to obtain the initial temperature and salinity fields. The initial temperature and salinity fields are horizontally homogeneous in the lower 5500 m. The model forcing is the horizontal flow across the four open boundaries, with the current data taken from the climatological HYCOM reanalysis47. Inside the four open boundaries, the model thermodynamic variables are relaxed to the climatology across a sponge layer of 5 grid points. The net flow across the boundaries is computed and all normal velocities on boundaries are adjusted to obtain zero net inflow.

Our mixing parameterization configurations follow ref. 48. We apply the Smagorinsky’s scheme for horizontal eddy viscosity49. To investigate the mechanism of trench circulation and the role of tidal-induced turbulent mixing in it, two numerical experiments with different vertical eddy viscosity schemes, were conducted in the regional circulation model. The experiment named NoTM is configured with the KPP scheme50, which uses a constant background diffusivity of 1 × 10−5 m2 s−1, without considering tidal mixing. Another experiment named TMCD configured with modified KPP schemes, replacing the constant background diffusivity with tidal-induced diffusivity based on the tidal mixing scheme described below.

The tidal mixing scheme used for the regional circulation model in this study follows the work of ref. 33. A three-dimensional, high-resolution internal tide model is used to reproduce diapycnal mixing induced by the dissipation of internal tides generated both locally and remotely. To depict details of the deep ocean, here we set a layer thickness of 100 m below 5500 m depth. The internal tide model is forced by eight primary tidal constituents (M2, S2, N2, K2, K1, O1, P1 and Q1) at the open boundaries. Their amplitudes and phases are extracted from the Oregon State Tidal Inversion Software (OTIS) dataset with 1/12° horizontal resolution (https://www.tpxo.net/regional, Pacific Ocean 1/12°). From an initial state, the internal tide model is integrated with time steps of 90 s for 120 model days, reaching an equilibrium state after 30 model days. The time series from days 106 to 120 are used for analyzing the tidal mixing. The baroclinic energy budget analysis method is applied for the estimation of diapycnal diffusivity51,52. Supplementary Fig. S7 displays the vertical distribution of the tidal-induced diapycnal diffusivity along transect 142.5°E. The diapycnal diffusivity increases toward the bottom and is of O(10−3 to 10−2) near the bottom. This result is generally consistent with diapycnal diffusivity estimates from CTD profiles in the trench5,22,44. Hence, this tidal mixing scheme is suitable for examining the effect of tidal mixing on the deep circulation at the CD.

From an initial state, both numerical experiments were integrated with time steps of 600 s for 100 model years. They reached an equilibrium state after 20 model years. The averaged results of the 100th model year were used for analyzing the deep circulation. Building on the TMCD, we conducted an experiment named TMCD-MBF with monthly horizontal flows as the open boundary forcing. Starting from the TMCD results of the 100th model year as the initial state, the TMCD-MBF was integrated for 20 model years, reaching equilibrium after 4 model years.

Data availability

The bathymetric data is from GEBCO Gridded Bathymetry Data (http://www.gebco.net). WOA18 dataset is available at https://www.nodc.noaa.gov/OC5/woa18. HYCOM reanalysis dataset is available at http://apdrc.soest.hawaii.edu/dods/public_ofes/HYCOM/GLBu0.08/daily_snapshot.info. GLORYS12V1 reanalysis dataset is available at https://resources.marine.copernicus.eu. The OTIS dataset is freely available at https://www.tpxo.net/regional. The data used for plotting the figures in the paper are available from https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13870930. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The codes used for generating the figures in the paper can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13870930.

References

Du, M. et al. Geology, environment, and life in the deepest part of the world’s oceans. Innovation 2, 100109 (2021).

Jamieson, A. J., Fujii, T., Mayor, D. J., Solan, M. & Priede, I. G. Hadal trenches: the ecology of the deepest places on Earth. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 190–197 (2010).

Johnson, G. C. Deep water properties, velocities, and dynamics over ocean trenches. J. Mar. Res. 56, 329–347 (1998).

Taira, K., Yanagimoto, D. & Kitagawa, S. Deep CTD Casts in the Challenger Deep, Mariana Trench. J. Oceanogr. 61, 447–454 (2005).

van Haren, H., Berndt, C. & Klaucke, I. Ocean Mixing in Deep-Sea Trenches: New Insights from the Challenger Deep, Mariana Trench. Deep Sea Res. Part I 129, 1–9 (2017).

Kawabe, M. & Fujio, S. Pacific ocean circulation based on observation. J. Oceanogr. 66, 389–403 (2010).

Jiang, H. et al. Ocean Circulation in the Challenger Deep Derived From Super-Deep Underwater Glider Observation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL093169 (2021).

Tian, J. et al. A nearly uniform distributional pattern of heterotrophic bacteria in the Mariana Trench interior. Deep Sea Res. Part I 142, 116–126 (2018).

Liu, X., Liu, Y., Cao, W. & Sun, C. Water characteristics of abyssal and hadal zones in the southern Yap Trench observed with the submersible Jiaolong. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 38, 593–605 (2020).

Siedler, G., Holfort, J., Zenk, W., Müller, T. J. & Csernok, T. Deep-Water Flow in the Mariana and Caroline Basins. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 34, 566–581 (2004).

Wang, J., Ma, Q., Wang, F., Lu, Y. & Pratt, L. J. Seasonal Variation of the Deep Limb of the Pacific Meridional Overturning Circulation at Yap-Mariana Junction. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 125, e2019JC016017 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Pathways, Volume Transport, and Seasonal Variability of the Lower Deep Limb of the Pacific Meridional Overturning Circulation at the Yap-Mariana Junction. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 579 (2021).

Zhou, C. et al. Intense Abyssal Flow Through the Yap‐Mariana Junction in the Western North Pacific. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL096530 (2022).

Kawabe, M., Fujio, S. & Yanagimoto, D. Deep-water circulation at low latitudes in the western North Pacific. Deep Sea Res. Part I 50, 631–656 (2003).

Taira, K., Kitagawa, S., Yamashiro, T. & Yanagimoto, D. Deep and Bottom Currents in the Challenger Deep, Mariana Trench, Measured with Super-Deep Current Meters. J. Oceanogr. 60, 919–926 (2004).

Whitworth, T. III et al. On the deep western-boundary current in the Southwest Pacific Basin. Prog. Oceanogr. 43, 1–54 (1999).

Fujio, S., Yanagimoto, D. & Taira, K. Deep current structure above the Izu-Ogasawara Trench. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 105, 6377–6386 (2000).

Hallock, Z. R. & Teague, W. J. Evidence for a North Pacific Deep Western Boundary Current. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 101, 6617–6624 (1996).

Owens, W. B. & Warren, B. A. Deep circulation in the northwest corner of the Pacific Ocean. Deep Sea Res. Part I 48, 959–993 (2001).

Warren, B. A. & Owens, W. B. Some preliminary results concerning deep Northern-Boundary currents in the North Pacific. Prog. Oceanogr. 14, 537–551 (1985).

Warren, B. A. & Owens, W. B. Deep Currents in the Central Subarctic Pacific Ocean. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 18, 529–551 (1988).

Huang, C. et al. Seasonal Variability of Water Characteristics in the Challenger Deep Observed by Four Cruises. Sci. Rep. 8, 11791 (2018).

Munk, W. & Wunsch, C. Abyssal recipes II: energetics of tidal and wind mixing. Deep Sea Res. Part I 45, 1977–2010 (1998).

Wunsch, C. & Ferrari, R. Vertical Mixing, Energy, and the General Circulation of the Oceans. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 36, 281–314 (2004).

Polzin, K. L., Toole, J. M., Ledwell, J. R. & Schmitt, R. W. Spatial variability of turbulent mixing in the abyssal ocean. Science 276, 93–96 (1997).

Tian, J., Yang, Q. & Zhao, W. Enhanced Diapycnal Mixing in the South China Sea. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 39, 3191–3203 (2009).

Ledwell, J. R. et al. Evidence for enhanced mixing over rough topography in the abyssal ocean. Nature 403, 179–182 (2000).

St Laurent, L. C., Toole, J. M. & Schmitt, R. W. Buoyancy Forcing by Turbulence above Rough Topography in the Abyssal Brazil Basin. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 31, 3476–3495 (2001).

Ferrari, R., Mashayek, A., McDougall, T. J., Nikurashin, M. & Campin, J.-M. Turning Ocean Mixing Upside Down. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 46, 2239–2261 (2016).

McDougall, T. J. & Ferrari, R. Abyssal Upwelling and Downwelling Driven by Near-Boundary Mixing. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 47, 261–283 (2017).

Wynne-Cattanach, B. L. et al. Observations of diapycnal upwelling within a sloping submarine canyon. Nature 630, 884–890 (2024).

Garrett, C. & Kunze, E. Internal Tide Generation in the Deep Ocean. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 39, 57–87 (2007).

Chen, Q. A. et al. Model Simulation of M2 Internal Tide at the Mariana Double Ridges. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 9, 592 (2021).

Sibson, R. Ch. A Brief Description of Natural Neighbor Interpolation. In Interpreting Multivariate Data, 21–36 (John Wiley & Sons, 1981).

Shan, S. et al. Carbon cycling in the deep Mariana Trench in the western north Pacific Ocean: Insights from radiocarbon proxy data. Deep Sea Res. Part I 164, 103370 (2020).

Johnson, G. C. & Toole, J. M. Flow of deep and bottom waters in the Pacific at 10°N. Deep Sea Res. Part I 40, 371–394 (1993).

Ma, Q., Wang, F., Wang, J. & Lyu, Y. Intensified Deep Ocean Variability Induced by Topographic Rossby Waves at the Pacific Yap-Mariana Junction. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 124, 8360–8374 (2019).

Yang, J. & Price, J. F. Water-mass formation and potential vorticity balance in an abyssal ocean circulation. J. Mar. Res. 58, 789–808 (2000).

Yang, J. & Price, J. F. Potential Vorticity Constraint on the Flow between Two Basins. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 37, 2251–2266 (2007).

Kawase, M. Effects of a Concave Bottom Geometry on the Upwelling-driven Circulation in an Abyssal Ocean Basin. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 23, 400–405 (1993).

Cimatoribus, A. A., van Haren, H. & Gostiaux, L. A Procedure to Compensate for the Response Drift of a Large Set of Thermistors. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 33, 1495–1508 (2016).

Matsumoto, H. & Araki, E. Drift Characteristics of DONET Pressure Sensors Determined From In-Situ and Experimental Measurements. Front. Earth Sci. 8 (2021).

van Haren, H. Philosophy and Application of High-Resolution Temperature Sensors for Stratified Waters. Sensors 18, 3184 (2018).

van Haren, H. Challenger Deep Internal Wave Turbulence Events. Deep Sea Res. Part I 165, 103400 (2020).

Marshall, J., Adcroft, A., Hill, C., Perelman, L. & Heisey, C. A finite-volume, incompressible Navier Stokes model for studies of the ocean on parallel computers. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 102, 5753–5766 (1997).

van Haren, H., Uchida, H. & Yanagimoto, D. Further correcting pressure effects on SBE911 CTD-conductivity data from hadal depths. J. Oceanogr. 77, 137–144 (2021).

Thoppil, P. G., Richman, J. G. & Hogan, P. J. Energetics of a global ocean circulation model compared to observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L15607 (2011).

Wang, X., Liu, Z. & Peng, S. Impact of Tidal Mixing on Water Mass Transformation and Circulation in the South China Sea. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 47, 419–432 (2017).

Smagorinsky, J. Ch. Large Eddy Simulation of Complex Engineering and Geophysical Flows. In Evolution of Physical Oceanography (eds Galperin, B. & Orszag, S. A.) 3–36 (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

Large, W. G., Mcwilliams, J. C. & Doney, S. C. J. Ro. G. Oceanic vertical mixing: A review and a model with a nonlocal boundary layer parameterization. Rev. Geophys. 32, 363–403 (1994).

Niwa, Y. & Hibiya, T. Three‐Dimensional Numerical Simulation of M2 Internal Tides in the East China Sea. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 109, 1–14 (2004).

Wang, X. et al. Tidal Mixing in the South China Sea: An Estimate Based on the Internal Tide Energetics. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 46, 107–124 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no.42176033, 42176021, 92258301, 42076027 and 91958205), the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant no. 2018YFC0309800), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant no. 2023M733640) and Innovational Fund for Scientific and Technological Personnel of Hainan Province (Grant no. KJRC2023D39). We thank Dr. Hans van Haren from the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research and Utrecht University for providing CTD profile data. We thank the crew of the R/V ‘Dongfanghong 2’ and ‘Tansuoyihao’ for the deployment and recovery of the moorings. We would like to thank the Institutional Center for Shared Technologies and Facilities of IDSSE, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for the use of their computing resources. We deeply cherish the memory of Professor Qiang Xie and thank him for his contribution to this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.X., C.Z. and H.J. conceived the central idea. H.J. and X.X. conducted most of the analyses and generated the figures. H.J., H.X., C.Z., X.X. and P.A.V. wrote the main manuscript. J.T., H.X. and C.Z. designed and conducted observations of the Mooring Array in the Challenger Deep, collected the mooring data and participated in data analysis with H.J., X.X., L.Y., T.L. Then, H.J., X.X., L.Y. and Q.C. performed the MITgcm model experiments and analyzed the model outputs. P.A.V., L.Y., T.L. and Q.C. contributed to the discussion of the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Robin Robertson, Jiayan Yang, and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, H., Xin, X., Xu, H. et al. Three-layer circulation in the world deepest hadal trench. Nat Commun 15, 8949 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53370-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53370-7