Abstract

Centrosymmetric materials with site inversion asymmetries possess hidden spin polarization, which remains challenging to be converted into spin currents because the global inversion symmetry is still conserved. This study demonstrates the spin-polarized circular photocurrents in centrosymmetric transition metal dichalcogenide semiconductors at normal incidence without applying electric bias. The global inversion symmetry is broken by using a spatially-varying circularly polarized light beam, which could generate spin gradient owing to the hidden spin polarization. The dependence of the circular photocurrents on electrode configuration, illumination position, and beam spot size indicates an emergence of circulating electric current under spatially inhomogeneous light, which is associated with the deflection of spin-polarized current through the inverse spin Hall effect. The circular photocurrents is subsequently utilized to probe the spin polarization and the inverse spin Hall effect under different excitation wavelengths and temperatures. The results of this study demonstrate the feasibility of using centrosymmetric materials with hidden spin polarization and non-vanishing Berry curvature for spintronic device applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spin and valley, as intrinsic degrees of freedom of electrons, are being investigated as new information carriers for next-generation devices1,2. Fundamental challenges in spintronics involve the injection, manipulation, and measurements of spin/valley polarization. A feasible method is to employ the circular photocurrent (CPC), i.e., to apply the circularly polarized light for spin/valley injection and measure the helicity-dependent photocurrent. CPC has been demonstrated in quantum wells3, Weyl semimetals4,5,6,7, and semiconducting transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs)8,9,10. The amplitudes of the such spin/valley-related photocurrents can be utilized to probe spin polarization11,12, fermion chirality4, Berry curvatures6, etc.

Despite emerging in a variety of materials, a common view is that spin- or valley-related CPC of nonmagnetic materials embodies a breaking of spatial inversion symmetry13. An intuitive approach is to use intrinsic non-centrosymmetric crystals or structures, such as Td-phase TMDCs6,14,15,16, monolayer 2H-phase TMDCs9,10, and surfaces of topological insulators17. As for centrosymmetric crystals, researchers develop a series of approaches to break the spatial inversion symmetry, including interlayer twisting, heterostructure construction, strain engineering, and the application of external electric field18. A typical example is 2H-phase TMDCs. Although monolayer and thin 2H-TMDCs with odd number of layers lacks inversion symmetry, the even layers, thick multilayers, and bulk crystals are considered to be centrosymmetric. As expected, the spin or valley-related CPC component in bilayer and thick multilayer TMDCs were non-vanishing only when the structural inversion symmetry is broken by external electric field through ionic gating19,20,21 or constructing Schottky barriers22,23 (Supplementary Table S1).

A decade ago, it was established that hidden spin polarization could exist in centrosymmetric crystals with atomic site inversion asymmetry, including but not limited to bulk silicon24 and bulk 2H-phase TMDCs24,25. A local site inversion asymmetry leads to local Dresselhaus effects, resulting in spin polarization localized on the non-centrosymmetric sector of a centrosymmetric crystal. Each individual non-centrosymmetric sector possesses a nonzero spin polarization spatially localized in real space, while an opposite spin polarization lies in its inversion partner24. The total spin polarization of the centrosymmetric crystal is zero by summing over the spin polarizations of all sectors, hence it is termed hidden24,26. Although bulk 2H-TMDCs, belonging to D6h point group, have zero net spin polarization, opposite spin polarizations arising from local Dresselhaus effect are spatially located at individually non-centrosymmetric α and β sectors belonging to the D3h point group. Subsequently, the hidden spin polarization has been directly observed in 2H-phase WSe2, MoS2, and MoTe2 by spin- and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (spin-ARPES)27,28,29,30 and is used to explain the helicity-dependent photoluminescence26,31 and elliptically polarized terahertz emission25.

The existence of spin/valley polarization is necessary but not sufficient for spintronic devices. Although the helicity-dependent photoluminescence shows the possibility for photoexcitation of the spin-polarized carriers in bilayer or multilayer 2H-TMDCs, it was found that the intrinsic spin or valley-related CPC current and Kerr rotation angle vanish without symmetry breaking19,22,32. This problem limits the spintronic applications of multilayer 2H-TMDCs despite their higher conductivity and stability compared to their monolayer counterparts. The same challenge exists for other centrosymmetric structures with hidden spin polarizations.

In this study, intrinsic spin-polarized CPC is demonstrated in centrosymmetric TMDC semiconductors including thick multilayer 2H-phase MoTe2, MoS2 and WSe2 at normal incidence under no external electric bias. Instead of breaking the structural inversion symmetry of the material, the inversion symmetry of the system is broken by adopting a spatially-varying beam profile. The manifestation of hidden spin-polarization by CPC is attributed to the inverse spin Hall effect (ISHE), which converts the light-induced spin gradient to charge current. The induced circulating current is confirmed by the dependence of CPC on the electrode configuration and illumination position. Subsequently, the CPC is utilized to reveal the information on spin polarization of 2H-TMDCs by evaluating its wavelength-dependence and temperature-dependence. The results demonstrate feasibility of using multilayer 2H-TMDCs for practical spintronic applications and contributes to the ongoing exploration of materials for spintronic applications.

Results and discussion

The crystal structure of 2H-TMDCs is depicted in Fig. 1a. The upper and lower layers of the unit cell are respectively represented as α sector and β sector, which are inversion symmetric about the red point in the middle. α and β sectors are also in a 180° rotation relative to each other and thus show reversed K and K’ valleys. The valence band of each layer splits into VB1 and VB2 due to the Ising spin-orbit coupling (SOC). This energy splitting allows one to choose an excitation wavelength for selective excitation of carriers from VB1. In the picture of hidden spin polarization, carriers from K valleys of α sector (Kα) and β sector (Kβ) are locked with spin down state (|↓〉) at VB1 and spin up state (|↑〉) at VB2, while K’α and K’β valleys possess opposite spin polarization. Because the α sector and β sector are separated in real space, carriers from the Kα, Kβ, K’α, and K’β valleys inherit their original optical selection rules under σ+/σ- optical excitation26. The right circular polarized σ + light can excite the Kα and Kβ but not the K’α and K’β valley, as depicted in Fig. 1b. If the excitation wavelength is resonant with VB1-CB transition, |↓〉 are excited due to spin-valley locking. Correspondingly, σ- optical excitation is expected to excite carriers at K’α and K’β valleys and generate opposite spin polarization. Assuming that the α sector and β sector were two independent monolayers, the spin polarization ratio is 100%. For an actual multilayer 2H-TMDC crystal, the spin polarization ratio of K point is 28%–91%, as revealed by spin-ARPES27,28,29,30,33. The reduced spin polarization ratio is correlated with the mixing of |↑〉 and |↓〉 states at K and K’ valleys26,29 (see details in Supplementary Fig. S1).

a Crystal structures of 2H-MoTe2. b The right circular polarized light (σ+) excites spin down states at Kα valleys of α sector and Kβ valleys of β sector. c The spatial distribution of laser intensity for Gaussian beams. d Schematic diagram depicting the creation of a spin current induced by the intensity gradient of the Gaussian beam, subsequently converting into the circulating charge current. The gradient red region represents the distribution of spin polarization. The light blue arrows indicate the direction of pure spin current, while the black arrows represent the direction of charge current.

To obtain spin polarized photocurrent, we propose a method to convert the differences in spin of carriers under σ+/σ- optical excitation into differences in electric currents. Specifically, a focused Gaussian laser beam with its intensity distribution shown in Fig. 1c is normally incident on centrosymmetric TMDCs. The spatially excitation can induce a gradient distribution of spin-polarized charge carriers proportional to the local light intensity16,34,35, leading to a radially diffused spin current (Fig. 1d). The spin current could be converted to a transverse charge current34,36,37,38 if ISHE is applicable in 2H-TMDCs, as we will discuss later. Driven by the ISHE, the moving carriers from the spin current will deviate from their original paths and acquires a velocity component along the circumference (black arrows in Fig. 1d), forming a circulating charge current34. A pair of head-to-head electrodes deviating from center of a circle will collect uncompensated charge current with its sign determined by the charge circulating direction34,39,40. In this way, the angular momentum of photons can be converted into the circular motion of electrons34. The mechanism of the Gaussian beam method is different from that of the electric field gating. Rather than breaking the inherent structural symmetry of the 2H-TMDCs20, the Gaussian beam reduce the system symmetry by patterning the circularly-polarized optical excitation field, which allows the uncovering of the otherwise hidden spin polarization.

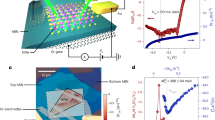

Based on the above mechanism, an experimental set-up is constructed for measuring the CPC of centrosymmetric 2H-TMDCs, as schematically shown in Fig. 2a. Multilayer 2H-phase MoTe2 (>20 nm) flakes were adopted as a representative centrosymmetric semiconductor due to a high hidden spin polarization ratio33 and large SOC splitting41. The 2H-phase is confirmed by XRD, Raman spectroscopy and electrical characteristics of the MoTe2 transistors (Supplementary Fig. S2–S4). A circular Gaussian laser spot is normally incident on MoTe2 through an objective lens. A band-pass filter of 1100 ± 10 nm is applied for the selectively exciting the A exciton at K and K′ point and the light polarization is modulated by rotating a quarter-wave plate.

a Schematic experimental set-up for measuring helicity-dependent photocurrents. b, c Optical photographs of multilayer devices with different electrode configurations. d, e Photocurrents respectively measured from device in 2b/2c as rotation angle of the quarter wave plate is adjusted and spot a/b is illuminated. The error bars of Ipc represent the standard deviation. No bias or gate voltages is applied. Red curves were fitted by using Eq. (1).

All of the measurements are carried out at room temperature under vacuum conditions. Two types of devices made of multilayer MoTe2 with different electrode configurations, namely A and B, are shown in Fig. 2b, c. Device A adopts two head-to-head electrodes contacting opposite edges of the channel for the observation of CPC. Device B, as a control, uses a pair of parallel electrodes across the width of the MoTe2 channel. Spot a and spot b of two devices are respectively illuminated for obtaining polarization-dependent photocurrents, as shown in Fig. 2d, e. Upon illumination on spot a, the periodic modulation with a period of π correspond to a circular polarization dependence, while the differences between the photocurrents under σ- light (45°, 225°) and those under σ + light (135°, 315°) indicate the emergence of CPC. In our experiment, the power of σ- and σ + light showed a difference of <0.1%, while the CPC of multiple devices can account for 7.4% to even >100% of the total photoelectric current (Supplementary Fig. S5), ruling out the possibility of photo-thermoelectric effect. Moreover, the thermoelectric current is minimized when the laser spot is at the mid-point between the two electrodes (Supplementary Fig. S4b). Circular photon drag effect (CPDE) is suggested as a dominant source of CPC in monolayer TMDCs when the obliquely incident light is applied8. In this study, the possibility of CPDE-induced CPC is naturally ruled out at an incidence normal to the crystal plane42,43. Here, the effects from extrinsic factors should be evaluated. First is the interface effect. Although weak spatial symmetry breaking can be extrinsically introduced into thin layers via spontaneous doping from substrate or external gating, this interface effect is estimated to be negligible in thick multilayers spanning tens of nanometers. Even for bilayer 2H-TMDC, a potential difference between the top and bottom layers is estimated to be only on the order of ~meV by using solid gating, which is too low to induce spin/valley Hall effect44. Second, no external electric bias or gating voltages is applied and the possibility of phase transition in MoTe2 induced by laser irradiation45,46 has been eliminated (Supplementary Fig. S3). Therefore, the CPC arises from the intrinsic properties of 2H-MoTe2. The phenomena observed in Fig. 2d is applicable to other multilayer 2H-TMDCs. Non-vanishing CPC is also observed in thick multilayer 2H-MoS2 and 2H-WSe2 (see Supplementary Fig. S6). When spot b of device B is illuminated, the photocurrent shows almost no CPC but only a linear polarization dependence, as shown in Fig. 2e. This result is consistent with previous studies on multilayer 2H-phase TMDC devices using an electrode configuration same with B, where CPC diminishes under normal incidence or without ionic gating19,20,21. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S7b, CPC at oblique incidence is non-vanishing for device B under the focused laser beam, consistent with the observation in bilayer MoS247 with same electrode configuration. But the magnitude of CPC at oblique incidence decreases when the light intensity gradient is reduced by increasing the off-focus amount (see Supplementary Fig. S7c).

The mechanism of CPC in device A is investigated by analyzing its dependence on illumination position and spot size. Figure 3a demonstrates a series of polarization-dependent photocurrent (Ipc) curves when moving the laser spot along the vertical bisector line on device A (X position). The total photocurrent (Ipc) can be described as3,21,

where θ is the rotation angle of quarter-wave plate, C and L account for helicity-dependent and linear polarization-dependent components, and I0 is the polarization-independent background current. After fitting the Ipc curves by using Eq. (1), the C values are illustrated as a function of X position in Fig. 3b. Along X, the C value shows a positive peak and a negative peak on opposite sides of the midpoint. Near the midpoint or away from the electrode pair, the C value diminishes. Same results have been observed for a series of 2H-MoTe2 devices made from 20-65 nm flakes. This distinctive spatial pattern of C component indicated a circulating charge current round the laser spot, which has been recognized as the characteristic of the ISHE. Previously, similar CPC have been observed from quantum well34,39, topological insulator Bi2Se340, InN48, Td-MoTe235, and ReS249 by using the same electrode configuration. Herein, the emergence of ISHE in multilayer 2H-MoTe2 indicate the existence of non-vanishing Berry curvature, which could arise from SOC or hidden Berry curvatures50. Previously, the SOC induced ISHE has been observed in multilayer 2H-WS237. In TMDC systems with weak Rashba SOC, the spin Hall effect was attributed to Ising SOC51, which is also suggested as a possible origin of the ISHE observed in this study. The out-of-plane spin polarization is orthogonal to both the radial spin current and the local electric current, which fulfills the requirement for spin-to-charge conversion in crystals with more than one mirror planes of symmetry52,53. On the other hand, hidden Berry curvature has recently been observed in bulk 2H-WSe2 by ARPES54, which may theoretically cause a Hall effect due to the same sign of Berry-curvatures for valleys selected by circularly polarized light50,55. However, this mechanism contradicts the observations in previous literatures, which show no valley Hall effect on centrosymmetric 2H-TMDCs22,32,44. Further study is required to determine the origin of the non-vanishing Berry curvatures. The focusing spot and electrode configuration allows the hidden spin polarization of the centrosymmetric TMDCs to be manifested by the electrical signal. This is an important step forward from previous optical characterization methods (PL and spin-APARS) and demonstrates the possibility of using such hidden degree of freedom in practical electronic devices.

a Photocurrent for different illumination location as a function of the quarter-wave plate angle. The circular dots represent experimental data, while the solid line represents the curve fitted using Eq. (1). The error bars of Ipc represent the standard deviation. b Fitted C as a function of X position along the perpendicular bisector of channel. c Fitted C as a function of Y position along the channel. The insets in (b) and (c) depict the relative displacement of laser spot with respect to the device. The yellow and gray areas represent the metal electrode and the MoTe2 sample, respectively. d The spot size dependence of fitted C under 1100 nm illumination at a fixed position. The w is standard deviation of Gaussian distribution correlated with the spot size. The solid curve is guideline for eyes. e The power dependence of fitted C at minimum spot size under 1100 nm illumination. The measurements were carried out without applying bias or gate voltage. The error bars of fitted C represent the standard error.

An interesting comparison to our results is from a previous study on MoTe2 of other crystal phases. Under the excitation of focused Gaussian beam profiles, a same condition with our study, Zhurun Ji et al.16 observed no CPC in 1 T’-MoTe2 and circulating CPC in Td-MoTe2 and Mo0.9W0.1Te2. They attribute the CPC to circular photogalvanic effect (CPGE) arising from antisymmetric terms in the nonlinear conductivity tensor under broken inversion symmetry, while the terms vanish in the inversion symmetric 1 T’-MoTe2. For 2H-MoTe2 used in this study, the CPC is unlikely to originate from the antisymmetric conductivity terms because the CPGE tensor for 2H-TMDCs is zero56. Different from 1T’-MoTe2 exhibiting inversion symmetry for both global crystal and each single layer, multilayer 2H-MoTe2 crystals is centrosymmetric but shows site inversion asymmetry, which allows the generation of spin-polarized CPC.

The CPC observed along laser scan of the channel (Y position) exhibits a peak at both ends near the electrode, shown in Fig. 3c, which is due to the establishment of a Schottky barrier at the sample-electrode interface. The generation of CPC due to the existence of Schottky barrier has been observed in MoSe223, Si nanowire57, and semimetal Cd3As258, which is considered a third-order nonlinear effect15. The photocurrent profile is not perfectly symmetrical, showing a non-zero photocurrent at the midpoint during scan along X and Y directions. This could potentially be due to irregularities of the sample and the imperfect spot shape of the laser beam. The focusing spot and the electrode position-dependent CPC provides flexibility for tuning the CPC signal through the design of optical field distributions.

The effect of light intensity gradient is demonstrated by examining how Gaussian spot size influences the CPC. As illustrated in Fig. 3d, the enlargement of the spot size with fixed illumination intensity leads to a gradual decline in CPC until its eventual dissipation (Supplementary Fig. S8). The w is standard deviation of Gaussian distribution correlated with the spot size. This observation indicated the pivotal role of the intensity gradient of the Gaussian light spot. When increasing the light intensity, as shown in Fig. 3e, C firstly increase and then reach a saturation. The saturation is attributed to the gradual enlargement of the absorption saturation region in the Gaussian spot center as light intensity increases, limiting the spin gradient.

To determine the energy band origin of the spin photocurrent, the spectral response of CPC was acquired. Photocurrents Ipc as a function of the quarter-wave plate angle were recorded at a fixed illumination position and different the incident wavelengths ranging from 700 nm–1400 nm, as illustrated in Fig. 4a. Extracted from these photocurrent curves, the coefficient C as a function of incident wavelengths is depicted in Fig. 4b. Either when left or right side of the channel is illuminated, the magnitude of C attains its maximum value at a wavelength of 1100 nm, which is near resonance with A exciton at the K point of ∼1.1 eV59,60. When the incident wavelength deviates from 1100 nm to a longer wavelength, the magnitude of C wanes as a result of the attenuated absorbance. Shorter incident wavelengths also correspond to smaller magnitudes of C which is attributed to a lowering of the spin polarization. As the center wavelength is tuned from 1100 nm to 700 nm by using a filter with FWHM of 10 nm, the total net spin contains differently weighted contributions from A exciton, B exciton, indirect bandgap transition at 0.52 Γ-Κ point, and direct bandgap transition at K point. Among them, B exciton contributes an opposite spin relative to that of A exciton, 0.52 Γ-Κ transition has zero spin polarization, bandgap transition at K point contributes a spin polarization same with that of A exciton at the absorption edge and zero spin at shorter wavelengths. This could explain the vanishing of C at 800 nm and shorter wavelength. The 800 ∼ 850 nm excitation wavelength corresponding to B excitons result in less pronounced CPC although A and B exciton theoretically contribute opposite spin polarization. The smaller absorption cross section at B exciton and the absorption overlap from bandgap transition at K point may result in such a difference. Similar observations have been demonstrated in PL polarization61 and CPC8 for monolayer TMDCs. Nevertheless, the wavelength dependence of C indicates that A excitons emerge as the pivotal player in the generation of CPC8,19.

a Photocurrent as a function of the waveplate angle at different incident wavelengths from 700 nm to 1400 nm. The error bars of Ipc represent the standard deviation. b The incident wavelength dependence of the fitted coefficient C. Red line and blue line represent C values when the laser spot illuminated at X = −11 μm and X = 11 μm respectively, as labeled in the inset figure. The error bars of fitted C represent the standard error. Gray curve is the absorbance of thick 2H-MoTe2 extracted from the reflection spectrum and fitted by Lorentz and Tauc–Lorentz models59.

Next, the temperature dependence of CPC is investigated. As depicted in Fig. 5a, the magnitudes of C for different illumination spots diminish with a reduction in temperature. Different from 1Td-MoTe2 device, in which the CPC decreases with temperature due to the Lifshitz transition14, a different mechanism is expected for 2H-phase MoTe2. To examine the influences from mobility and contact resistance, the temperature dependence of the conductance G derived from I-V curves (see Supplementary Fig. S9) was examined. As shown in Fig. 5b, G declines more rapidly with decreasing temperature than the magnitude of C. To eliminate the influences of conductance, we extracted C/G ratios to represent the electrical potential that drives the swirling current. As shown in Fig. 5c, the magnitude of C/G rises when the temperature is decreased from 293 K to 103 K. The temperature evolution of C/G can be driven by the combined effects of temperature on spin Hall angle, spin/valley lifetime, spin diffusion length and spin polarization ratio37,38. As the temperature decreases, the blue shift in exciton energy59,62 and the narrowing of the absorption peak may cause a slight detuning from the fixed incident light wavelength. This could potentially introduce disturbances in the measured C and C/G data. In TMDCs, the spin polarization ratio reduces at lower temperatures due to the increase in interlayer coupling and almost unchanged SOC26,29. Given the positive correlation between temperature and C/G, we infer that the temperature effect on spin/valley scattering and relaxation prevails that on spin polarization ratio.

In summary, spatially-dispersive CPC has been observed in multilayer 2H-MoTe2 device without applying any external electric bias. In order to achieve the spin-polarized CPC, it was found necessary to use unevenly-distributed light beam to break the global inversion symmetry. The maximum amplitude of CPC is located at 1100 nm, suggesting the A excitons at K and K′ valley as the primary source of the photocurrent. Accordingly, the CPC is identified as intrinsic spin photocurrent originating from the hidden spin polarization and ISHE. Moreover, CPC under inhomogeneous light is also observed in multilayer 2H-MoS2 and 2H-WSe2. The same method could be extended to other centrosymmetric materials with hidden spin polarization and non-vanishing Berry curvature, demonstrating the feasibility of using a new library of materials for valleytronics and spintronics devices.

Methods

Fabrication of MoTe 2 devices

MoTe2 nanoflakes were prepared by mechanical exfoliation from commercial bulk crystals (hq graphene) on 300 nm SiO2/Si substrates. The electrodes were predefined by e-beam lithography and then deposited with 5/60 nm Ti/Au by electron beam evaporation.

Characterizations of MoTe2

Raman spectra were obtained by using a lab-equipped Raman spectrometer consisting of a 488 nm laser, a 100× lens, a Princeton Instruments SP-2500 spectrometer and a Pixis 100 CCD camera. The reflection spectrum of MoTe2 crystal was measured using a UV-Vis-NIR spectrophotometer (SolidSpec-3700). Absorbance is derived from the reflection spectrum by A = log(1/R). The thickness of MoTe2, WSe2, and MoS2 was measured by an atomic force microscope (AFM, Bruker Dimension Edge).

Photocurrent measurements

The incident light from a supercontinuum laser (YSL photonics. SC-5) went through a single bandpass filter (Andover Corp. FS20-25), a linear polarizer, and a rotatable quarter-waveplate (Union Optic. WPA4420-900-2100, WPA4420-650-900) from 0° – 360° to modulate its polarization. Band-pass filters with a FWHM of 10 nm are used to select the desired wavelengths. The laser was focused using a plan semi-apochromatic objective. During measurement, the laser spot for each wavelength was refocused and readjusted to the same position on the device to ensure accuracy. The 1100 nm laser was focused by a 50 × objective lens to an FWHM ~ 12 μm spot. The intensity distribution of the beam spot was measured using a CMOS beam profiler (WinCamD-LCM). The power of the left- and right- circularly-polarized light measured by a power meter showed a difference of <0.1%. Scanning photocurrent image was collected with a motorized two-dimensional displacement stage (S&I GmbH). Electrical measurements were carried out on the probe stage (Instec Inc. HCP421V-PM) in vacuum at room temperature with an Keysight B1500A semiconductor parameter analyzer. The temperature controller (Instec Inc. mK2000) and chiller (Instec Inc. C100W) were used to perform the experiments under cooling conditions.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Mak, K. F., Xiao, D. & Shan, J. Light–valley interactions in 2D semiconductors. Nat. Photonics 12, 451–460 (2018).

Li, L. et al. Room-temperature valleytronic transistor. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 743–749 (2020).

Ganichev, S. D. & Prettl, W. Spin photocurrents in quantum wells. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 15, R935–R983 (2003).

Ma, Q. et al. Direct optical detection of Weyl fermion chirality in a topological semimetal. Nat. Phys. 13, 842–847 (2017).

Rees, D. et al. Helicity-dependent photocurrents in the chiral Weyl semimetal RhSi. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba0509 (2020).

Xu, S.-Y. et al. Electrically switchable Berry curvature dipole in the monolayer topological insulator WTe2. Nat. Phys. 14, 900–906 (2018).

De Juan, F., Grushin, A. G., Morimoto, T. & Moore, J. E. Quantized circular photogalvanic effect in Weyl semimetals. Nat. Commun. 8, 15995 (2017).

Quereda, J. et al. Symmetry regimes for circular photocurrents in monolayer MoSe2. Nat. Commun. 9, 3346 (2018).

Liu, L. et al. Electrical control of circular photogalvanic spin-valley photocurrent in a monolayer semiconductor. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 3334–3341 (2019).

Eginligil, M. et al. Dichroic spin–valley photocurrent in monolayer molybdenum disulphide. Nat. Commun. 6, 7636 (2015).

Yu, J. et al. Observation of current-induced spin polarization in the topological insulator Bi2Te3 via circularly polarized photoconductive differential current. Phys. Rev. B 104, 045428 (2021).

Ma, Q., Krishna Kumar, R., Xu, S.-Y., Koppens, F. H. L. & Song, J. C. W. Photocurrent as a multiphysics diagnostic of quantum materials. Nat. Rev. Phys. 5, 170–184 (2023).

Xu, H., Wang, H., Zhou, J. & Li, J. Pure spin photocurrent in non-centrosymmetric crystals: bulk spin photovoltaic effect. Nat. Commun. 12, 4330 (2021).

Lim, S., Rajamathi, C. R., Süß, V., Felser, C. & Kapitulnik, A. Temperature-induced inversion of the spin-photogalvanic effect in WTe2 and MoTe2. Phys. Rev. B 98, 121301 (2018).

Ma, J. et al. Circular photogalvanic effect from third-order nonlinear effect in 1T’-MoTe2. 2D Mater. 8, 025016 (2021).

Ji, Z. et al. Spatially dispersive circular photogalvanic effect in a Weyl semimetal. Nat. Mater. 18, 955–962 (2019).

McIver, J. W., Hsieh, D., Steinberg, H., Jarillo-Herrero, P. & Gedik, N. Control over topological insulator photocurrents with light polarization. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 96–100 (2012).

Du, L. et al. Engineering symmetry breaking in 2D layered materials. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3, 193–206 (2021).

Guan, H. et al. Photon wavelength dependent valley photocurrent in multilayer MoS2. Phys. Rev. B 96, 241304 (2017).

Yuan, H. et al. Generation and electric control of spin–valley-coupled circular photogalvanic current in WSe2. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 851–857 (2014).

Guan, H. et al. Inversion symmetry breaking induced valley Hall effect in multilayer WSe2. ACS Nano 13, 9325–9331 (2019).

Lee, J., Mak, K. F. & Shan, J. Electrical control of the valley Hall effect in bilayer MoS2 transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 421–425 (2016).

Quereda, J. et al. The role of device asymmetries and Schottky barriers on the helicity-dependent photoresponse of 2D phototransistors. Npj 2D Mater. Appl 5, 13 (2021).

Zhang, X., Liu, Q., Luo, J.-W., Freeman, A. J. & Zunger, A. Hidden spin polarization in inversion-symmetric bulk crystals. Nat. Phys. 10, 387–393 (2014).

Huang, Y. et al. Hidden spin polarization in the centrosymmetric MoS2 crystal revealed via elliptically polarized terahertz emission. Phys. Rev. B 102, 085205 (2020).

Liu, Q., Zhang, X. & Zunger, A. Intrinsic circular polarization in centrosymmetric stacks of transition-metal dichalcogenide compounds. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 087402 (2015).

Riley, J. M. et al. Direct observation of spin-polarized bulk bands in an inversion-symmetric semiconductor. Nat. Phys. 10, 835–839 (2014).

Razzoli, E. et al. Selective probing of hidden spin-polarized states in inversion-symmetric bulk MoS2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 086402 (2017).

Zhang, Y. et al. The origin of the band-splitting and the spin polarization in bulk 2H-WSe2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 122, 142402 (2023).

Bussolotti, F., Maddumapatabandi, T. D. & Goh, K. E. J. Band structure and spin texture of 2D materials for valleytronics: insights from spin and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Mater. Quantum Technol. 3, 032001 (2023).

Jones, A. M. et al. Spin–layer locking effects in optical orientation of exciton spin in bilayer WSe2. Nat. Phys. 10, 130–134 (2014).

Mak, K. F., McGill, K. L., Park, J. & McEuen, P. L. The valley Hall effect in MoS2 transistors. Science 344, 1489–1492 (2014).

Tu, J. et al. Direct observation of hidden spin polarization in 2H-MoTe2. Phys. Rev. B 101, 035102 (2020).

He, X. W. et al. Anomalous photogalvanic effect of circularly polarized light incident on the two-dimensional electron gas in AlxGa1−xN/GaN heterostructures at room temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 147402 (2008).

Zhang, Y. et al. Inverse spin Hall photocurrent in thin-film MoTe2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116, 222103 (2020).

Sinova, J., Valenzuela, S. O., Wunderlich, J., Back, C. H. & Jungwirth, T. Spin hall effects. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 1213–1260 (2015).

Dastgeer, G. et al. Surface spin accumulation due to the inverse spin hall effect in WS2 crystals. 2D Mater. 6, 011007 (2018).

Safeer, C. K. et al. Room-temperature spin hall effect in graphene/MoS2 van der Waals heterostructures. Nano Lett. 19, 1074–1082 (2019).

Tang, C. G., Chen, Y. H., Liu, Y. & Wang, Z. G. Anomalous-circular photogalvanic effect in a GaAs/AlGaAs two-dimensional electron gas. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 375802 (2009).

Yu, J. et al. Photoinduced inverse spin Hall effect of surface states in the topological insulator Bi2Se3. Nano Lett. 17, 7878–7885 (2017).

Liu, G.-B., Shan, W.-Y., Yao, Y., Yao, W. & Xiao, D. Three-band tight-binding model for monolayers of group-VIB transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 88, 085433 (2013).

Jiang, C. et al. Helicity-dependent photocurrents in graphene layers excited by midinfrared radiation of a CO2 laser. Phys. Rev. B 84, 125429 (2011).

Shalygin, V. A., Moldavskaya, M. D., Danilov, S. N., Farbshtein, I. I. & Golub, L. E. Circular photon drag effect in bulk tellurium. Phys. Rev. B 93, 045207 (2016).

Wu, Z. et al. Intrinsic valley hall transport in atomically thin MoS2. Nat. Commun. 10, 611 (2019).

Fukuda, T. et al. Photoinduced structural dynamics of 2H-MoTe2 under extremely high-density excitation conditions. J. Phys. Chem. C. 127, 13149–13156 (2023).

Cho, S. et al. Phase patterning for ohmic homojunction contact in MoTe2. Science 349, 625–628 (2015).

Zhao, Y. et al. Spin-Layer Locking Induced Second-Order Nonlinear Effect in Centrosymmetric Crystals. https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-126567/v1 (2020).

Mei, F. H. et al. Detection of spin-orbit coupling of surface electron layer via reciprocal spin hall effect in InN films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 132404 (2012).

Zhang, Y. et al. Local electric-field-induced spin photocurrent in ReS2. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 13, 11689–11695 (2022).

Du, L. Comment on “disentangling orbital and valley hall effects in bilayers of transition metal dichalcogenides”. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 149701 (2021).

Tao, Z. et al. Giant spin hall effect in AB-stacked MoTe2/WSe2 bilayers. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 28–33 (2024).

Roy, A., Guimarães, M. H. D. & Sławińska, J. Unconventional spin hall effects in nonmagnetic solids. Phys. Rev. Mater. 6, 045004 (2022).

Safeer, C. K. et al. Large multidirectional spin-to-charge conversion in low-symmetry semimetal MoTe2 at room temperature. Nano Lett. 19, 8758–8766 (2019).

Cho, S. et al. Experimental observation of hidden Berry curvature in inversion-symmetric bulk 2H−WSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 186401 (2018).

Kormányos, A., Zólyomi, V., Fal’ko, V. I. & Burkard, G. Tunable berry curvature and valley and spin hall effect in bilayer MoS2. Phys. Rev. B 98, 035408 (2018).

Le, C. & Sun, Y. Topology and symmetry of circular photogalvanic effect in the chiral multifold semimetals: a review. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 33, 503003 (2021).

Dhara, S., Mele, E. J. & Agarwal, R. Voltage-tunable circular photogalvanic effect in silicon nanowires. Science 349, 726–729 (2015).

Wang, B. M. et al. Spatially dispersive helicity-dependent photocurrent in Dirac semimetal Cd3As2 nanobelts. Phys. Rev. B 108, 165405 (2023).

Jung, E. et al. Unusually large exciton binding energy in multilayered 2H-MoTe2. Sci. Rep. 12, 4543 (2022).

Ruppert, C., Aslan, B. & Heinz, T. F. Optical properties and band gap of single- and few-layer MoTe2 crystals. Nano Lett. 14, 6231–6236 (2014).

Mak, K. F., He, K., Shan, J. & Heinz, T. F. Control of valley polarization in monolayer MoS2 by optical helicity. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 494–498 (2012).

Du, L. et al. Temperature-driven evolution of critical points, interlayer coupling, and layer polarization in bilayer MoS2. Phys. Rev. B 97, 165410 (2018).

Acknowledgements

S.W. acknowledges the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (12074134). C.Y. acknowledges National Natural Science Foundation of China (12204184). L.D. acknowledges National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 12274447, 12422402). We acknowledge the Analysis and Testing Center of Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.Z. and S.W. initiated the project. K.W. conceived and carried out the sample fabrication and experiments. B.Z. developed the experiment technique and assisted in measurements. K.W. and B. Z. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript with the help from C.Y., L.D., and S.W.. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Shasha Guo, Zeyu Zhang and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, K., Zhang, B., Yan, C. et al. Circular photocurrents in centrosymmetric semiconductors with hidden spin polarization. Nat Commun 15, 9036 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53425-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53425-9