Abstract

The Human Silencing Hub (HuSH) complex silences retrotransposable elements in vertebrates. Here, we identify a second HuSH complex, designated HuSH2, which is centered around TASOR2, a paralog of the core TASOR protein in HuSH. Our findings reveal that HuSH and HuSH2 localize to distinct and non-overlapping genomic loci. Specifically, HuSH localizes to and represses LINE-1 retrotransposons, whereas HuSH2 targets and represses KRAB-ZNFs and interferon signaling and response genes. We use in silico protein structure predictions to simulate MPP8 interactions with TASOR paralogs, guiding amino acid substitutions that disrupted binding to HuSH complexes. These MPP8 transgenes and other constructs reveal the importance of HuSH complex quantities in regulating LINE-1 activity. Furthermore, our results suggest that dynamic changes in TASOR and TASOR2 expression enable cells to finely tune HuSH-mediated silencing. This study offers insights into the interplay of HuSH complexes, highlighting their vital role in retrotransposon regulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Retrotransposable elements constitute a substantial portion of the vertebrate genome, with sequences derived from retroelements representing approximately 42% of the human genome. This observation underscores the transformative role of reverse transcription products and the reverse transcriptase enzyme in shaping genome composition and regulation. To mitigate potential genomic instability induced by transposons, cells have evolved intricate silencing mechanisms involving covalent modifications to histones and DNA, thereby effectively suppressing the activity of these parasitic genetic elements.

The HuSH complex plays a central role in the epigenetic regulation of retrotransposons through its association with chromatin and RNA-modifying proteins. For instance, HuSH interacts with SETDB1, facilitating the deposition of histone H3 lysine 9 trimethylation (H3K9me3), and MORC2, an ATP-dependent chromatin remodeler crucial for transcriptional repression1,2. The recruitment of these effectors stimulates the catalysis of H3K9me3 and the formation of heterochromatin1,3. The targets of the HuSH complex include endogenous retroviruses (ERVs), LINE-1 (L1) retrotransposons, pseudogenes, and intron-less mRNAs transcribed by RNA polymerase II that exceed a length of approximately 1.5 kilobases1,4,5,6.

While a comprehensive understanding of HuSH recruitment to genomic loci is not complete, previous work suggests that engagement with RNA is essential for effective transposable element repression by the complex6,7. Additionally, the presence of introns appears to confer protection against HuSH-mediated silencing of transgenes6. Through genome-wide analyses, two categories of HuSH targets have been identified. The first category consists of evolutionarily young transposable elements that exhibit a high abundance of repressive histone modifications8. The second category comprises expressed coding and non-coding pseudogenes that lack repressive histone modifications and transposons6,9. Although the role of HuSH in silencing is well-documented, the precise regulatory mechanisms governing HuSH localization and function are not fully understood.

In this study, we report the discovery of a HuSH complex variant, HuSH2, which includes canonical members MPP8 and PPHLN1 centering around TASOR2. We find that HuSH2 localizes to and represses the expression of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs). Additionally, the abundance of HuSH and HuSH2 complexes is influenced by alterations in TASOR and TASOR2 levels, due to competition between TASOR proteins for a limited amount of MPP8 and PPHLN1. Modifying the balance of the two HuSH complexes within cells informs the regulation of transposable elements, such as LINE-1 in human lymphoblast cells.

Furthermore, the intricate interplay between HuSH and HuSH2 complexes involves their specific binding to distinct loci on human chromosomes. Notably, variations in the levels of core TASOR proteins disrupt the precise localization of these complexes, highlighting the critical role of this core subunit in maintaining proper genomic organization. By introducing targeted residue substitutions that disrupt the interactions between MPP8 and TASOR or TASOR2, we provide compelling evidence that these interactions are crucial for the localization and silencing mechanisms of HuSH. This study highlights the impact of altering the levels of HuSH complexes, emphasizing their essential role in regulating silencing mechanisms and linking the recognition and silencing of retrotransposon elements with the induction of an immune response.

Results

Identification of TASOR2 as the core subunit of the HuSH2 Complex

The mechanisms responsible for the recruitment of the HuSH complex to specific genomic regions are not yet fully understood, leaving important questions about how this complex is recruited to silence retrotransposable elements and pseudogenes. Additionally, the subunits that constitute the HuSH complex lack apparent enzymatic activity; instead, the prevailing model proposes that the complex primarily functions as a central hub, enabling essential protein-protein interactions necessary for its silencing activities7. To identify proteins associated with the HuSH complex that may contribute to its recruitment and silencing functions, and potentially uncover undescribed core members, we conducted an extensive study utilizing a rigorous immunoprecipitation (IP) approach coupled with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis (Fig. 1B-D). Specifically, we employed stably expressed epitope-tagged transgenes of the known HuSH core complex members, TASOR, MPP8, and PPHLN1, in HEK293 cells.

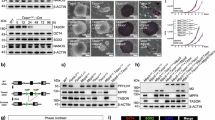

A Molecular representation of each HuSH complex member and TASOR2, with position of FLAG epitope tag and each known domain named. BD= Binding Domain, AA=amino acid. B Immunoprecipitation-mass spectrometry (IP/MS) analysis performed in HEK293T cells expressing FLAG-tagged transgenes (x-axis). This analysis revealed the association of TASOR2 with PPHLN1 and MPP8 (y-axis). The data is presented as the Normalized Spectral Abundance Factor (NSAF), normalized to the length of prey targets and compared to a wild-type HEK293T immunoprecipitation negative control. Immunoprecipitation-mass spectrometry was conducted in biological duplicates and a standard student’s t-test was performed to calculate p-values for statistical significance. C Immunoblots of FLAG immunoprecipitation (IP) in K-562 cell-line expressing no transgene (wild type; WT -), FLAG-TASOR, or FLAG-TASOR2. This experiment was repeated at least twice independently with similar results. D Silver stain of FLAG-PPHLN1 immunoprecipitation (IP) from ammonium sulfate nuclear extract of 293 F cells. This experiment was repeated three independent times with similar results. E Immunoblots of MPP8 and TASOR immunoprecipitation (IP) in parental wild-type cells or MPP8 knockouts (KO) or TASOR KOs expressing FLAG-TASOR2. This experiment was repeated at least twice independently with similar results. F Immunoblots of FLAG immunoprecipitation (IP) performed in stable genome edited HuSH knockout K-562 cells, expressing no transgene (Neg. Control) or FLAG-PPHLN1 (isoform 3). This experiment was repeated at least twice independently with similar results.

As anticipated, our analyses employing LC-MS/MS, immunoblotting, and silver staining techniques validated the associations between MPP8, PPHLN1, and TASOR. However, we made an intriguing and unexpected discovery of an association between MPP8 and PPHLN1 with an uncharacterized protein, fam208b, also known as TASOR2, a paralog of TASOR (Fig. 1B). Utilizing mass spectrometry analysis on samples obtained from FLAG-PPHLN1 and FLAG-MPP8 immunoprecipitation, we achieved comprehensive peptide coverage across TASOR2 (Supplementary Fig. 1C, D). Although human TASOR and TASOR2 paralogs are predicted to possess N-terminal pseudo-PARP domains, our mass spectrometry data did not reveal any peptides originating from the TASOR2 pseudo-PARP domain in our immunoprecipitation experiments. Notably, the TASOR2 isoforms that lack the exons encompassing the N-terminal pseudo-PARP domain, are found expressed in most if not all human tissues (exons 2–4; Supplementary Fig. 1A). These findings suggest that the TASOR2 isoform lacking the pseudo-PARP domain is predominant in HEK293 and K-562 cells and we have confirmed that this isoform associates with PPHLN1 and MPP8 (Fig. 1B–E and Supplementary Fig. 1C, D).

Mutually Exclusive Assembly of HuSH and HuSH2 Complexes

To validate and further explore the association of TASOR2 with the HuSH subunits, we generated stable K-562 cell lines expressing FLAG epitope-tagged TASOR and TASOR2 transgenes, followed by FLAG immunoprecipitation. Our findings revealed that TASOR2 specifically associated with PPHLN1 and MPP8 but did not co-immunoprecipitate with TASOR (Fig. 1B, C). Conversely, TASOR co-IP experiments clearly demonstrated an association with PPHLN1 and MPP8, whereas no such association was observed with TASOR2 (Fig. 1B, C). Additionally, an anti-MPP8 antibody efficiently co-immunoprecipitated TASOR2 in a manner dependent on MPP8 (Table 1). Similarly, co-immunoprecipitation experiments using an anti-TASOR antibody demonstrated the TASOR-dependent association with MPP8; however, no interaction with TASOR2 was detected (Fig. 1E). These experiments collectively illustrate the existence of mutually exclusive HuSH assemblies for TASOR and TASOR2, suggesting the potential for distinct roles of these proteins within HuSH complexes.

In addition to TASOR2, our immunoprecipitation experiments identified both previously described and undescribed associations with HuSH assemblies. Notably, we detected subunits of the human nuclear exosome targeting (NEXT) complex, the zinc finger protein NP220 (also known as ZNF638)10, components of the EHMT1/2 complex11, and proteins involved in DNA damage response12 as HuSH-associating proteins. Additionally, we observed previously undescribed associations between HuSH and RNA-binding proteins, as well as chromatin-binding proteins (Supplementary Fig. 2A, B). Some proteins involved in gene repression showed distinct associations with either TASOR or TASOR2. For instance, NP220 and EHMT1/2 complex associated with HuSH, while HCFC-1 and SIN3A were associated with HuSH2. However, most associated proteins did not exhibit a distinct preference between the two HuSH complexes.

Prior work has proposed that TASOR serves as the core subunit for the HuSH complex, primarily based on the inability of MPP8 to co-immunoprecipitate PPHLN1 in overexpression experiments in cells7,13,14. Our immunoprecipitation experiments demonstrated that TASOR and TASOR2 exhibit mutual exclusivity in their associations with MPP8 and PPHLN1. To investigate the function of TASOR2 and other HuSH subunits, we employed CRISPR/Cas-9 technology to create knockout cell lines for MPP8, PPHLN1, TASOR, and TASOR2, as well as a dual knockout of TASOR/2. We observed that epitope-tagged PPHLN1 can associate with MPP8 in cell lines where either TASOR or TASOR2 has been knocked out. However, the association between PPHLN1 and MPP8 was completely abrogated in the double TASOR/2 knockout cells (Fig. 1F). These findings indicate that TASOR and TASOR2 facilitate the association between MPP8 and PPHLN1 and suggest that TASOR2 may serve as the core protein for a second HuSH complex. Notably, we observed a discernible reduction in the amount of MPP8 associating with PPHLN1 in co-immunoprecipitation experiments from TASOR knockout cells compared to TASOR2 knockout cells. This observation suggests that HuSH is more abundant than HuSH2 within K562 cells, as corroborated by the stoichiometry observed in a silver stain of both complexes (Fig. 1D). The results obtained from the immunoprecipitation experiments provide robust evidence for the existence of two distinct HuSH complexes, each organized around one of the two TASOR paralogs. Prior research on HuSH has revealed its association with both pseudogenes and retrotransposable elements2,4,6,8.

Genomic localization and targeting of HuSH and HuSH2

To address the question of whether the two HuSH complexes associate with overlapping or distinct genomic loci, we generated knockout cell lines for each HuSH subunit and conducted ChIP-seq experiments using antibodies specific for TASOR, TASOR2, MPP8, and PPHLN1. We selected the human K-562 chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) cell line for our studies due to its high levels of TASOR2 expression and average levels of TASOR expression relative to other commonly used cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 2C, D). This approach enabled us to identify the genomic binding sites of the HuSH complexes and evaluate the influence of individual subunits on their localization (Fig. 2A, B, E and Supplementary Fig. 3).

A IGV genome browser tracks of MPP8, PPHLN1, TASOR, and TASOR2 ChIP-seq in parental wild type (WT) and knockout (KO) cell lines. One HuSH site is shown (left) at an L1PA7 element within MBNL1. One HuSH2 site is shown (right) at LTR elements. B Average profile of PPHLN1, MPP8, TASOR, and TASOR2 ChIP-seq across HuSH and HuSH2 sites created using Deeptools. C Heatmap and peak profiles illustrating MPP8 ChIP-seq results, performed in K-562 cells in HuSH knockout backgrounds. Peaks were called using MACS2 in biological replicates (n = 2) of TASOR knockout and TASOR2 knockout, generating two non-overlapping regions, corresponding to HuSH2 and HuSH sites, respectively. D Bar chart showing MPP8 ChIP-qPCR results, performed in technical replicates (n = 2) of knockout cell lines at HuSH and HuSH2 sites. Enrichment was measured as the percent input over the average percent input at negative control sites (GNG and RABL3). Each replicate is plotted as a dot and bars are graphed to depict the mean of each measurement. E Bar chart showing TASOR (blue) and PPHLN1 (peach) ChIP-qPCR results, performed in technical replicates (n = 2) of WT and knockout cell lines at HuSH and HuSH2 sites. Enrichment was measured as the percent input over the average percent input at negative control sites (GNG and RABL3). Each replicate is plotted as a dot and bars are graphed to depict the mean of each measurement.

Our ChIP-seq data revealed a notable correlation between the localization of MPP8 and PPHLN1 in the presence of either TASOR or TASOR2. By examining MPP8 and PPHLN1 ChIP-seq peaks in TASOR and TASOR2 knockout cell lines, we identified specific genomic regions bound by either the HuSH or HuSH2 complex (Fig. 2C and Supplementary Fig. 4A). HuSH peaks were defined as genomic regions where MPP8 and PPHLN1, co-localize, and which are dependent on TASOR but not on TASOR2. Conversely, HuSH2 peaks were defined as genomic regions where MPP8 and PPHLN1 co-localize in the absence of TASOR, and which are dependent on TASOR2. We observed the co-localization of MPP8, TASOR, and PPHLN1 in the HuSH complex at 264 genomic sites. Notably, HuSH and HuSH2 exhibited no overlap in their designated genomic regions (Supplementary Fig. 4A). Our ChIP-seq analyses further revealed a strong correlation between HuSH peaks and LINE-1 elements, with nearly 40% of HuSH ChIP peaks located near LINE-1 elements, particularly within the L1HS and L1PA families of primate LINE-1 elements (Supplementary Fig. 4C, D). In contrast, HuSH2 peaks showed minimal overlap with LINE-1 elements and were predominantly located near gene promoters and enhancers (Supplementary Fig. 4B, C). This distinct localization pattern suggests different genomic targeting mechanisms for the HuSH and HuSH2 complexes.

Functional implications of TASOR2 in LINE-1 silencing

We observed a notable increase in the enrichment of MPP8 and PPHLN1 at HuSH2 sites in TASOR knockout cells. In contrast, there was minimal change in the enrichment of TASOR, MPP8, and PPHLN1 at HuSH sites in TASOR2 knockout cells (Fig. 2C, D and Supplementary Fig. 3). These findings corroborate our co-immunoprecipitation results, which suggest higher amounts of HuSH compared to HuSH2 in K-562 cells (Fig. 1D, F). Based on insights from our co-immunoprecipitation and ChIP-seq experiments, we propose a model wherein MPP8 and/or PPHLN1 serve as critical and limiting factors, influencing the formation of the HuSH complex around either TASOR or TASOR2.

To evaluate our hypothesis concerning the competitive interaction between TASOR proteins and their influence on the localization of the two complexes, we conducted MPP8 ChIP experiments in cell lines overexpressing epitope-tagged TASOR or TASOR2 proteins (Fig. 3A–C). Notably, the overexpression of either TASOR or TASOR2 in wild-type parental cells led to a reduction in MPP8 levels at the opposing genomic sites. These data support the proposed model, suggesting that MPP8, and potentially PPHLN1, play pivotal roles as limiting members in the assembly of functionally competent HuSH complexes. Building upon these ChIP-seq results, we hypothesized that MPP8 and PPHLN1 may be limiting components of the HuSH complexes. To further test this hypothesis, we generated RNA-seq data from TASOR knockout cells and identified differentially expressed genes upon the loss of TASOR, which could be restored upon complementation with a TASOR transgene (Fig. 3E and Supplementary Fig. 5B). We observed that overexpression of TASOR2 could partially phenocopy the differential gene expression caused by the loss of TASOR (Fig. 3D, E). This finding suggests that although TASOR and TASOR2 occupy distinct genomic regions, their functional interplay appears to be modulated by the concentrations of the other paralog, thereby highlighting the critical roles of MPP8 and PPHLN1 as limiting factors within this regulatory pathway.

A IGV genome browser tracks of MPP8 ChIP-seq in parental wild-type (WT), knockout (KO) cell lines, and FLAG-TASOR or FLAG-TASOR2 overexpression systems. One HuSH site is shown on the left at the exon of BOD1L1, and one HuSH2 site is shown on the right at an LTR element. B Heatmap and peak profiles displaying MPP8 ChIP-seq results, performed in K-562 cells with FLAG-TASOR or FLAG-TASOR2 overexpression. The results are sorted into either HuSH or HuSH2 dependent peaks. C Bar chart illustrating MPP8 ChIP-qPCR conducted in technical replicates (n = 2) of FLAG-TASOR or FLAG-TASOR2 overexpressing cell lines at HuSH and HuSH2 sites. Enrichment is measured as a percentage of input over the average percentage input at negative control sites (GNG and RABL3). Each replicate is plotted as a dot and bars are graphed to depict the mean of each measurement. D Volcano plot presenting total RNA-seq (ribo-depleted) differential expression analysis of genes in K-562 TASOR knockout (KO) cells, performed with two biological replicates, compared to WT puromycin-resistant biological replicates. Differentially expressed (DE) genes (red and blue) meet the following criteria: logCPM > 1, |logFC| > 1, and p-value < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using EdgeR default settings. Out of the 267 differentially expressed genes, 100 (black) are differentially expressed in the same direction in WT + FLAG-TASOR2 cells. E Bar chart showing RT-qPCR performed in biological replicates (n = 2) using RNA collected from WT clones, TASOR KO, TASOR KO rescued with FLAG-TASOR transgene, and WT overexpressing FLAG-TASOR2. Expression levels are measured relative to GAPDH and WT RNA. Each replicate is plotted as a dot and bars are graphed to depict the mean of each measurement.

To investigate the roles of HuSH2 and TASOR2 in LINE-1 silencing, we evaluated ORF1p levels in HuSH subunit knockout cells (Fig. 4A). We observed a marked upregulation of ORF1p in the PPHLN1, MPP8, and TASOR knockout cell lines, indicating derepression of LINE-1 silencing, consistent with previous research findings. Notably, ORF1p expression remain unchanged in TASOR2 knockout cells compared to wild-type parental cells. This observation aligns with the absence of HuSH2 ChIP-seq peak enrichment at LINE-1 elements, suggesting that TASOR2 does not play a direct role in repressing LINE-1 elements within the HuSH complex regulatory network. Our immunoblot analysis revealed a decrease in the steady-state levels of MPP8 and PPHLN1 in TASOR knockout cells. Conversely, the deletion of PPHLN1 or MPP8 resulted in reduced TASOR levels. However, TASOR2 knockout cells did not show a similar decrease, further supporting the notion of reduced HuSH2 levels in these cells (Fig. 4A).

A Immunoblot of whole-cell lysate generated from K-562 CRISPR-Cas9 stable KOs in bioreplicate. This experiment was repeated at least four independent times with similar results. B Immunoblot of whole-cell lysate generated from K-562 wild type (WT), knockout (KO), and FLAG transgene rescues (B–D). These experiments were repeated at least twice independently with similar results. B PPHLN1 KO and FLAG-PPHLN1 (isoform 3); (C) MPP8 KO and MPP8-FLAG; (D) TASORs dKO and FLAG-TASOR. E Schematic representation of the HuSH complex silencing LINE-1 elements. F Immunoblot of whole-cell lysate from K-562 WT, TASOR KO, and TASOR KO with either FLAG-TASOR or FLAG-TASOR2 expressed, highlighting the differential expression and rescue efficiency. This experiment was repeated at least twice independently with similar results. G Immunoblot of whole-cell lysate from K-562 WT, TASOR2 KO with increasing levels of FLAG-TASOR2 transgene expressed, compared to a TASOR KO, illustrating dose-dependent effects. This experiment was repeated at least twice independently with similar results. H Immunoblot of whole-cell lysate from K-562 WT, overexpression of FLAG-TASOR or FLAG-TASOR2 in a wild type (WT) background, showing the impact of overexpression on HuSH complexes. This experiment was repeated at least twice independently with similar results. I Diagram depicting the competitive interaction between TASOR2 and other HuSH components (MPP8 and PPHLN1), demonstrating how increasing TASOR2 levels can destabilize the HuSH complex and impair its ability to silence LINE-1 elements.

We introduced wild-type transgenes of PPHLN1, MPP8, and TASOR to investigate their potential to rescue the silencing of LINE-1 in the respective knockout models. Notably, our findings demonstrate that each of these transgenes effectively restored LINE-1 silencing in their corresponding knockout cell lines and stabilize levels of other HuSH complex members (Fig. 4B, C, F). Furthermore, we observed that TASOR was also capable of rescuing LINE-1 silencing in a double TASOR-TASOR2 knockout cell line (Fig. 4D). These results provide robust evidence for the regulatory role of HuSH in silencing LINE-1 elements and underscore the contributions of all subunits in this process (Fig. 4E). In contrast, the expression of a TASOR2 transgene in a TASOR knockout background failed to rescue LINE-1 silencing but did successfully restore MPP8 protein steady-state levels (Fig. 4F).

Role of MPP8 in HuSH complex assembly and function

Our co-immunoprecipitation and ChIP-seq findings led us to propose that PPHLN1 and/or MPP8 are limiting HuSH subunits in K-562 cells. Consequently, we suggest that competition for these two subunits could potentially regulate LINE-1 elements silencing by altering the levels of HuSH and HuSH2 in cells. An increase in HuSH2 would lead to a decrease in HuSH and loss of LINE-1 silencing (Fig. 4I). To test this hypothesis, we titrated the levels of a wild-type TASOR2 transgene in TASOR2 knockout cells. We found that high levels of the TASOR2 transgene led to derepression of LINE-1, mimicking the effect observed in TASOR knockout cells (Fig. 4G). Additionally, we observed that high levels of a wild-type TASOR2 transgene in wild-type K-562 cell line also led to derepression of LINE-1 elements (Fig. 4H). Importantly, overexpression of a wild-type TASOR transgene did not have this effect. These findings reveal that by manipulating the expression levels of TASOR and TASOR2, either through knockout or overexpression, we can modulate the levels of HuSH and consequently alter the silencing of LINE-1 elements.

Our findings indicate that MPP8 and/or PPHLN1 serve as limiting factors in the assembly of HuSH complexes. We aimed to gain a deeper understanding of how MPP8 functions in modulating the equilibrium within HuSH complexes. Our hypothesis centered on the notion that disrupting the interaction between MPP8 and either TASOR or TASOR2 would result in changes in cellular levels of HuSH2 or HuSH. To achieve this, we employed AlphaFold2 predictions to investigate the formation of secondary and tertiary structures during the complex formation between the TASOR proteins and MPP815.

Previous studies have already defined the interaction domains between TASOR and MPP8, which include the MPP8 region located C-terminal to the ankyrin repeats, as well as the DUF3715, SPOC, and DomI domains of TASOR7,13. Although the DomI domains in TASOR and TASOR2 orthologs display substantial dissimilarity in their sequences, AlphaFold2 predictions suggest that both human TASOR proteins share a similar predicted secondary structure (Fig. 5A) and adopt a structurally analogous fold that encompasses four alpha helices. One of these alpha helices is anticipated to interact with a 137-residue domain situated at the C-terminus of MPP8, comprising of beta-sheets and an alpha helix. We generated TASOR and TASOR2 transgenes with two amino acid substitutions, in which we replaced leucine or isoleucine residues with arginine. Subsequently, we introduced these transgenes into TASOR and TASOR2 knockout cells. Our results revealed that the dual L/I-to-R substitutions in both TASOR proteins disrupted their interaction with MPP8 while leaving the interaction with PPHLN1 unaffected, as demonstrated by co-immunoprecipitation (Fig. 5B, C).

A AlphaFold2 predicted structure of MPP8 -TASORs binding domains with DomI of both TASOR and TASOR2 overlapped. Mutated residues highlighted, predicted to disrupt interaction of MPP8 with TASOR (L602R, L606R) or TASOR2 (L269R, L272R). B Immunoblots of FLAG immunoprecipitation (IP) performed in TASOR KO cell-lines stably expressing empty vector (WT-), FLAG-TASOR wild type, or mutant transgene. This experiment was repeated at least twice independently with similar results. C Immunoblots of FLAG immunoprecipitation (IP) performed in TASOR2 KO cell-lines stably expressing empty vector (WT-), FLAG-TASOR2 wild type, or mutant transgene. This experiment was repeated at least twice independently with similar results. D Immunoblot of whole-cell lysate generated from K-562 WT, TASOR KO, and WT/mutant transgene rescue cell-lines. This experiment was repeated at least twice independently with similar results. E Immunoblot of whole-cell lysate generated from K-562 WT, TASOR2 KO, and WT/mutant transgene rescue cell-lines. This experiment was repeated at least twice independently with similar results. F Bar chart showing MPP8 ChIP-qPCR done in technical replicates (n = 2) of WT, TASOR KO, or WT/mutant transgene rescue cell-lines. Intensity measured at HuSH and HuSH2 sites measured by enrichment of percent input over average percent input at negative control sites (GNG and RABL3). Each replicate is plotted as a dot and bars are graphed to depict the mean of each measurement. G Bar chart showing MPP8 ChIP-qPCR done in technical replicates (n = 2) of WT or WT/mutant transgene overexpression cell-lines. Intensity measured at HuSH and HuSH2 sites measured by enrichment of percent input over average percent input at negative control sites (GNG and RABL3). Each replicate is plotted as a dot and bars are graphed to depict the mean of each measurement.

The expression of the mutant TASOR transgene in a TASOR knockout background failed to restore LINE-1 silencing, a function effectively accomplished by expression of a wild-type TASOR transgene (Fig. 5D). When introduced in the context of a TASOR2 transgene, the L/I-to-R substitutions impaired the ability of TASOR2 overexpression to cause derepression of LINE-1, a function attainable with overexpression of wild-type TASOR2 in parental K-562 cells (Fig. 6E). To assess whether the derepression of LINE-1 elements is indeed linked to the inability of MPP8 to interact with and form HuSH, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) targeting MPP8, followed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (MPP8 ChIP-qPCR), in the TASOR mutant transgenic K-562 cell lines. TASOR knockout cells expressing the mutant TASOR transgene exhibited no MPP8 localization at HuSH sites but did not affect localization to HuSH2 sites (Fig. 6F). Additionally, TASOR2 knockout cells expressing a TASOR2 mutant transgene resulted in a loss of MPP8 localization at HuSH2 sites, but not HuSH sites (Fig. 6G). These findings underscore the significance of MPP8 in the formation of the HuSH complexes, and therefore the functionality.

A The results from HOMER findMotif analysis of peaks identified by MACS2 in TASOR2 ChIP-seq data. The top three significant motifs identified include members of the IRF transcription factor family, such as IRF2, ISRE, and IRF1. B Scatter plot illustrating the comparison of Normalized Spectral Abundance Factor (NSAF) enrichment in IP-MS data between TASOR2 and TASOR. Points in purple represent proteins more enriched in TASOR2 pulldowns, with -log(p-value) from TASOR2 NSAF enrichment being used. Points in blue represent proteins more enriched in TASOR pulldowns, with -log(p-value) from TASOR NSAF enrichment being used. All labeled proteins were found to be statistically significant using a standard Student’s t test (p-value < 0.05) and also associated with MPP8 and PPHLN1, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2). C Venn diagram depicting the overlap of peaks for TASOR2, IRF2, and HCFC1. Overlaps were determined using the BedTools window command with a default distance of 1Kb. D Heatmap and peak profiles showing the MACS2-called shared ChIP peaks for TASOR2/IRF2/HCFC1 or TASOR2/IRF2. TASOR2 ChIP-seq was conducted in both WT and TASOR2 KO cell lines, MPP8 ChIP-seq in WT cell lines, and IRF1, IRF2, and HCFC1 ChIP-seq data were obtained from the ENCODE K-562 public datasets. Accompanying bar charts depict the top DAVID functional annotation clusters for promoters found within the two groups of called peaks. E Bar chart displaying qRT-PCR results performed in biological replicates (n = 3) using RNA from WT clones, TASOR KO, and TASOR2 KO. Gene expression levels were normalized to GAPDH and WT RNA. Each replicate is plotted as a dot and bars are graphed to depict the mean of each measurement with error bars depicting ±SD. Statistical analysis using a Students t test revealed significant (*p < 0.05) or strongly significant (**p < 0.01) differences in expression compared to WT. Specifically for TASOR2 KO expression compared to WT the p-values are as follows from left to right (0.0016, 0.0039, 0.0119, 0.0053, 0.0222, 0.0295). For TASOR KO expression compared to WT the p-values are as follows from left to right (0.7264, 0.4031, 0.7702, 1.6494e-05, 0.4034, and 0.0691).

Our data provide evidence for the existence of a second HuSH complex centered around TASOR2, which exhibits distinct localization patterns within the human genome. Except for the pseudo-PARP domain, which is absent in the dominant TASOR2 isoform found in most cells (Supplementary Fig. 1A), all other known domains in TASOR are present in TASOR2 (Fig. 1A). Previous studies have suggested that the pseudo-PARP plays an important role for HuSH in LINE-1 silencing7,16. We aimed to explore the importance of the TASOR pseudo-PARP domain in the localization of HuSH and silencing of LINE-1 in K-562 cells. Additionally, we sought to determine whether TASOR lacking its pseudo-PARP domain can relocalize to HuSH2 sites.

To address these hypotheses, we introduced a wild-type TASOR transgene or a TASOR transgene lacking the pseudo-PARP domain in TASOR knockout cells and performed ChIP-seq experiments (Supplementary Fig. 5). Our findings revealed that TASOR knockout led to the loss of TASOR ChIP-seq signal at HuSH sites, accompanied by an increase in the LINE-1 ORF1p protein (Supplementary Fig. 5B, C). Furthermore, the introduction of a wild-type TASOR transgene into TASOR knockout cells restored the ChIP-seq peaks associated with HuSH (Supplementary Fig. 5C). Remarkably, we observed that a TASOR transgene lacking the pseudo-PARP domain was unable to effectively silence LINE-1 elements in a TASOR knockout, in contrast to the wild-type transgene which demonstrated a robust decrease in ORF1p levels (Supplementary Fig. 5B). Notably, the absence of the pseudo-PARP domain resulted in no identifiable TASOR peaks, similar to a full TASOR knockout. These results support the important role of the pseudo-PARP domain of TASOR in HuSH localization. However, the absence of the pseudo-PARP domain did not result in the relocalization of PARP-less TASOR to HuSH2 sites. These findings suggest that additional domains specific to TASOR2 are instrumental in the localization to gene promoters and other chromosomal regions exhibiting HuSH2 occupancy (Supplementary Fig. 4B, C).

Recruitment mechanisms of HuSH2 to gene promoters

Given that the pseudo-PARP domain in TASOR is essential for its localization to retrotransposons, but TASOR2 lacks this domain, we hypothesized that TASOR2 is recruited through alternative mechanisms. We postulated that sequence-specific transcription factors might associate with HuSH2 to facilitate its recruitment to genes. To investigate this, we completed TASOR2 ChIP-seq, but due to the suboptimal performance of commercially available TASOR2 antibodies in immunoblot and ChIP assays, we developed a rabbit polyclonal antibody specific to a region of human TASOR2. This unpublished antibody exhibited superior performance in both applications. Utilizing this antibody, we identified TASOR2-bound genomic loci in K-562 cells, revealing 471 TASOR2-enriched sites that were absent in TASOR2 knockout cell lines (Fig. 6D). We utilized high-quality TASOR2-enriched sequences and employed HOMER to identify sequence motifs prevalent among TASOR2 peaks. Our analysis revealed a significant enrichment of IRF1, IRF2, and ISRE motifs (Fig. 6A). We further analyzed available IRF1 and IRF2 ChIP-seq datasets in K-562 cells to assess the extent of overlap between these transcription factors and TASOR2. Our analysis revealed that 86% of TASOR2 peaks overlapped with IRF2 peaks in K-562 cells, suggesting a potential role of IRF2 in recruiting HuSH2 (Fig. 6C). However, IRF2 was not identified in our mass spectrometry datasets. We attribute this absence to the stringent wash conditions (750 mM KCl) employed to isolate direct interactors of HuSH subunits.

Among the most enriched non-HuSH subunits detected in the co-immunoprecipitation samples from TASOR2, MPP8, and PPHLN1 was Host Cell Factor-1 (HCFC1, also known as HCF-1). HCFC1 is a multifunctional protein involved in various transcriptional regulatory processes, including transcriptional repression. Notably, we did not identify HCFC1 as a TASOR-associated protein (Fig. 6B and Supplementary Fig. 2A,B). HCFC1 is known to interact with multiple transcription factors and co-repressors, thereby modulating gene expression through these interactions. Previous high-throughput studies have reported an association between HCFC1 and IRF217,18. Our findings indicated that 31% of TASOR2 ChIP-seq peaks overlapped with HCFC1 peaks in K-562 cells (Fig. 6C). Additionally, we observed a significant overlap between IRF2 and HCFC1 ChIP-seq peaks, with over 90% of TASOR2-bound genomic loci overlapping with either IRF2 and/or HCFC1.

The analysis of gene promoters within 1Kb of TASOR2 binding sites revealed a notable prevalence of two categories: interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) and KRAB-ZNF genes (Fig. 6D). ISGs are genes involved in interferon signaling, antiviral defense, and MHC class I antigen presentation19 and KRAB-ZNF genes, play a role in genome defense20. Specifically, IRF2, HCFC1, and TASOR2 shared genomic loci were enriched with ZNF-KRAB gene promoters, while loci primarily bound by IRF2 and TASOR2 were enriched with gene promoters involved in antiviral response. We employed quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) to assess the expression levels of selected KRAB-ZNFs and ISGs, whose promoters were occupied by TASOR2. Our findings indicated that the loss of TASOR2, but not TASOR, resulted in the derepression of these genes (Fig. 6E).

Proposed model for HuSH and HuSH2 complex functions

Collectively, these findings have led us to propose a model for the silencing of LINE-1 elements by the HuSH complex, and the repression of KRAB-ZNFs and ISGs by HuSH2. Under normal conditions in K-562 cells, TASOR acts as a central hub, facilitating the interaction between MPP8 and PPHLN1, which together form the HuSH complex. This complex associates with additional factors that may play a role in regulating its recruitment to chromatin, ultimately contributing to the subsequent silencing of LINE-1 elements. In K-562 cells, LINE-1 expression is typically low, primarily due to the high abundance of HuSH. However, when the levels of HuSH2 increase, either by reducing TASOR or increasing TASOR2 levels, MPP8 and PPHLN1 are titrated away from HuSH sites, thereby decreasing the abundance of HuSH in cells and resulting in the derepression of LINE-1 elements (Fig. 7). Additionally, the loss of HuSH2 leads to the upregulation of genes involved in antiviral monitoring and response. The exact process by which HuSH2 derepression is mitigated under typical conditions remains unknown. We hypothesize that heightened retrotransposon activity may increase the necessity for HUSH-mediated silencing, consequently titrating MPP8 and PPHLN1 away from HuSH2 complexes, and resulting in the derepression of HuSH2-bound ISGs.

HuSH and HuSH2 exist in a critical balance, each occupying distinct loci within the genome, as demonstrated by MPP8 ChIP-seq analysis (right panel). In the absence of either TASOR or TASOR2, the targeted complex fails to form, resulting in the inability of MPP8 to localize to the chromatin targeted by the missing complex. Consequently, an excess of MPP8 is available to stabilize and enhance the still intact complex. This redistribution of MPP8 from HuSH or HuSH2 sites leads to alterations in the silencing of LINE-1 elements, immune response-related genes (ISGs), and KRAB-ZNFs (ZNFs) in K-562 cells. The shift in MPP8 localization thereby significantly impacts the transcriptional regulation of these genomic elements, highlighting the delicate interplay between HuSH and HuSH2 in maintaining genomic stability and gene expression homeostasis in K-562 cells. Created in BioRender. Jensvold, Z. (2024) BioRender.com/z18k565.

Discussion

This study identifies a secondary HuSH complex, HuSH2, centered around TASOR2, a paralog of the core TASOR protein in HuSH. Our work explores the functional differences between HuSH and HuSH2, and the careful balance between the two complexes that cells can manipulate to control expression of their distinct targets. The differential binding patterns of these complexes, revealed through ChIP-seq analysis, demonstrate a clear segregation in their genomic loci. While HuSH predominantly associates with LINE-1 elements, HuSH2 localizes to specific gene promoters and enhancers. The identification of HuSH2 and its specific targeting of ISGs and KRAB-ZNF genes expands the known repertoire of HuSH complex functions and highlights the intricate regulation of genomic silencing processes.

The mechanistic basis of HuSH and HuSH2 recruitment to distinct genomic sites involves the interplay between core subunits and interacting proteins. For example, the pseudo-PARP domain in TASOR, previously suggested to be important for HuSH in LINE-1 silencing, plays a critical role in the localization of HuSH to LINE-1 elements. Previous work shows that the pseudo-PARP is important for HuSH-dependent H3K9me3. This finding was mechanistically ambiguous. Our experiments conclusively demonstrate that the absence of the TASOR pseudo-PARP prevents localization of the complex and therefore prevents establishment of H3K9me37. Recent work demonstrates that conservation among pseudo-PARP domains found in different vertebrate proteins when placed on TASOR can lead to effective silencing16. In addition, our proteomics data indicates that NP220 (ZNF638) interacts specifically with TASOR and not TASOR2. Previous work finds that the HuSH-NP220 interaction is important for silencing extrachromosomal retroviral DNA, and our data suggests that this function is specific for HuSH, not HuSH210.

The localization of HuSH2 is distinct from HuSH, as TASOR2 lacks the pseudo-PARP domain but effectively localizes to genes where it is involved in gene repression. The identification of HCFC1 as a TASOR2-specific partner, along with its known interaction with IRF2, provides a plausible mechanism for HuSH2 recruitment to ISG and KRAB-ZNF gene promoters. The overlap between TASOR2, IRF2, and HCFC1 binding sites further supports the role of transcription factors in directing HuSH2 localization. Our experiments show that TASOR lacking the pseudo-PARP domain affects LINE-1 silencing but does not relocalize TASOR to HuSH2 sites, indicating that additional domains specific to TASOR2 are important for its association with IRF2 and HCFC1.

Our functional assays demonstrate that altering the levels of TASOR and TASOR2 modulates the abundance and activity of HuSH and HuSH2 complexes, thereby impacting LINE-1 silencing and ISG expression. The competitive interaction between TASOR paralogs for MPP8 and PPHLN1 highlights the importance of balanced expression of these subunits in maintaining proper genomic regulation. The derepression of LINE-1 elements upon TASOR2 overexpression or TASOR knockout, coupled with the failure of TASOR2 to rescue LINE-1 silencing in a TASOR knockout background, underscores the specificity of TASOR for LINE-1 element repression.

Our in silico protein structure predictions and subsequent mutagenesis experiments reveal critical insights into the interactions between MPP8 and TASOR paralogs. The disruption of these interactions through targeted amino acid substitutions results in the loss of MPP8 binding and consequent failure of complex assembly and function. These findings provide a structural basis for the differential roles of TASOR and TASOR2 in HuSH complex formation and genomic targeting.

The evolution of the HuSH complexes showcases an important mechanism by which vertebrate genomes adapt to control the activity of retrotransposons and manage the host response to their activation. HuSH achieves this by recruiting various epigenetic modifiers to retrotransposon loci, leading to the formation of repressive chromatin states that prevent their transcription and mobilization. This silencing is essential for protecting the host genome from the deleterious effects of retrotransposon activity. However, the constant evolutionary arms race between host genomes and retrotransposons likely drives the need for additional regulatory layers, leading to the emergence of HuSH2. This variant not only participates in the repression of retrotransposons, through competition with HuSH, but also modulates the host’s response to their potential activation. HuSH2 likely evolves to fine-tune the immune response, preventing overreaction to retrotransposon activation, which could otherwise result in detrimental inflammation and autoimmunity. While this manuscript was under revision, a related study by Danac et al. reported the existence of the HuSH2 complex and its role in the regulation of interferon-response genes21,22.

By associating with factors such as IRF2 and regulating genes involved in antiviral responses, HuSH2 exemplifies an adaptive strategy to balance the need for retrotransposon suppression with the necessity of controlling the immune response. For instance, the interaction between TASOR2, a component of HuSH2, and IRF2 at various genomic loci underscores a complex regulatory network. When TASOR2 is lost, the derepression of genes like IFIH1 suggests that HuSH2 is critical for preventing an unnecessary immune response that could be triggered by retrotransposon activity.

The HuSH complex has been identified as a critical player in retrotransposon silencing across a wide range of developmental pathways and disease models. Its regulation impacts not only retrotransposons but also influences various aspects of biology. The significance of the HuSH complex in retrotransposon control has been recognized in the context of the HIV lifecycle23,24,25,26, as well as in mammalian development13. Moreover, it plays a pivotal role in the immune response in mammals5 and its dysregulation has been associated with Acute Myeloid Leukemia27,28. The intricate interplay between HuSH and HuSH2 could have significant implications for the reactivation of LINE-1 elements in development and disease.

The dynamic interplay between TASOR and TASOR2, mediated by their competition for limiting subunits MPP8 and PPHLN1, enables fine-tuned control of genomic silencing mechanisms. The identification of undescribed HuSH-associating proteins and the elucidation of transcription factor-mediated recruitment pathways offer different avenues for investigating the regulatory networks governing genomic stability and immune response. Further work into the precise molecular interactions and regulatory dynamics of HuSH complexes will provide deeper insights into their roles in genome regulation and potential implications for disease states characterized by dysregulated retrotransposon activity and immune response.

Methods

Transgenic cell lines and culture

K-562 human lymphoblast cell lines were purchased from ATCC (CCL-243). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 10% FBS, 1x glutamax and 1x penicillin-streptomycin, at 37 °C and 5% carbon dioxide. HEK293T human embryonic kidney cells (ATCC CRL-3216) were cultured in DMEM media supplemented with 10% FBS, 1x glutamax and 1x penicillin-streptomycin, grown at 37 °C at 5% carbon dioxide. All cell lines were monitored for mycoplasma contamination once a month, using the LiliF e-Myco plus Mycoplasma PCR Detection Kit.

Production of mammalian CRISPR-edited cell lines

Electroporation by Amaxa nucleofector 1D machine and Lonza Nucleofector Kit V (Catalog #: VCA-1003) was used to introduce CRIPSR editing plasmid (pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP (PX458)) with appropriate sgRNA sequences (Table 2) to K-562 cells. 24 h after electroporation cells were sorted by UW FLOW Core (Aria Cell Sorter) for single GFP cells into 96 well plates with K-562 media (described above), with an additional 10% FBS added. Successful CRISPR knockouts were screened by western blot analysis using appropriate antibodies (Table 1) and by genomic DNA sanger sequencing for deleterious mutations. Bio-replicates were grown separately from single-cell clonal populations that had confirmed distinct mutations by use of different gRNAs or different mutations from homologous recombination confirmed through gDNA sequencing.

Production of stable transgenic mammalian cell lines by transduction

Lentiviruses were produced by co-transfecting packaging vectors (psPAX2 and pMD2.G) and transfer vectors (pCDH-EF1a-MCS-PuroR) cloned with insertion of FLAG-PPHLN1, FLAG-TASOR, or FLAG-MPP8 transgenes, in HEK293T cells using PEI (24765-2) in vitro DNA transfection reagent. Media containing lentiviruses were collected 48 and 72 h after transfection. K-562 cells were transduced with lentiviruses for 2 days and selected using 2 ug/ml puromycin for 4 days.

Production of stable transgenic mammalian cell lines by electroporation

For protein expression of those above lentivirus packaging limits (>6 kb DNA sequences), electroporation of pCAG vector cloned with a FLAG-TASOR2-IRES-PuroR insertion was used (Amaxa nucleofector 1D). After 24 hours K-562 cells were selected using 1 ug/ml puromycin.

Immunoblot

Immunoprecipitation samples or whole-cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, blocked in 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.5 % Tween-20, probed with primary antibodies, and detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated or fluorescently labeled anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibodies. A list of the antibodies used is provided in Table 1.

NE Ammonium sulfate FLAG affinity purification

Cells were homogenized in hypotonic lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EGTA, 0.1 mM EDTA 1 mM DTT, 1 mM Benzamidine, 0.8 mM PMSF) and lysed in lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 110 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 1x Protease inhibitor cocktail, 0.4 mM PMSF). Lysis was incubated in 400 mM ammonium sulfate and centrifugated in ultra-centrifuge (28.5Kxg for 1.5 h). Nuclear extract was dialyzed in buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 250 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.01% NP-40, 0.4 mM PMSF, 2 mM BME) for 2 h twice. Nuclear extract was incubated with M2 anti-FLAG affinity gel (Sigma A2220) for 2 h. Beads were washed 3-times with wash buffer (15 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 750 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.05% Triton X-100, 8 mM PMSF) and captured proteins were eluted using 300 mg/ml of 3xFLAG peptide.

Whole-cell FLAG affinity purification

Cells were lysed in buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 200 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 2 mM MgCl2, 1x protein inhibitor cocktail, 0.2% Triton-x, 2 mM BME, 0.4 mM PMSF) and the resulting lysate was incubated with M2 anti-FLAG affinity gel (Sigma A2220) for 2 h. Beads were washed 3 times with wash buffer (15 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 300-750 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.05% Triton X-100, 8 mM PMSF) and captured proteins were eluted using 300 mg/ml of 3xFLAG peptides.

Liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry

After nuclear extract FLAG affinity purification, elution samples were analyzed by LC-MS/MS at the UW Biotech Center. Eluates from FLAG immunoprecipitation were subjected to reduction with 10 mM DTT for 30 min at 56 °C. This was followed by alkylation with 50 mM iodoacetamide for 40 min at room temperature in the dark to prevent re-formation of disulfide bonds. The samples were then diluted with four volumes of 50 mM Tris pH 8, 2 mM CaCl2, and digested overnight at 37 °C using 1 μg of trypsin. To terminate the digestion, trifluoroacetic acid was added to a final concentration of 1%. Samples were desalted using C18 stage tips prior to LC-MS/MS analysis. Peptide digests were analyzed using an EasyLC1000 nano-liquid chromatography system (Thermo) coupled to a Fusion Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo). Chromatographic separation was achieved with a flow rate of 400 nl/min, utilizing a gradient of 4–22% solvent B (80% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid) over 75 min, 22–35% solvent B over 15 min, 35–80% solvent B for 5 min, and holding at 80% solvent B for 10 min. Solvent A consisted of water with 0.1% formic acid.

For mass spectrometry analysis, a full MS scan was acquired every 2 s in the Orbitrap in positive centroid mode with a resolution of 120,000, scan range of 300–1200 m/z, automatic gain control (AGC) of 5e5, and maximum injection time of 50 milliseconds. Between full scans, data-dependent MS/MS (ddMS2) was performed on the most abundant precursors with charge states from +2 to +6. High-energy collision dissociation (HCD) fragmentation was used with a normalized collision energy (NCE) of 27. MS/MS data were collected in the ion trap in positive profile mode, using an isolation width of 2 m/z, with AGC set to 1e4 and maximum injection time of 120 milliseconds. Dynamic exclusion was set to 40 s to minimize repeated sequencing of the same precursor ions. The resulting MS/MS data were analyzed using ProteomeDiscoverer software (Thermo), searching against the UniProt human database. A precursor mass tolerance of 10 ppm and a fragment mass tolerance of 0.5 Da were applied. Carbamidomethylation of cysteines was set as a fixed modification, while N-terminal acetylation was considered a variable modification. Normalized Spectral Abundance Factor (NSAF) calculations were utilized, and Students t test was used for significance29. GGplot2 was utilized for all data visualization (bubblechart and scatterplots)30. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD04908531.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Approximately 40 million mammalian cells were crosslinked with 1% Paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 10 min at 37 °C and quenched with 0.2 M glycine. Cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 140 mL NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.5% NP40, 0.25% Triton X-100). Nuclei were washed twice with digestion buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 1 mM CaCl2, 20 mM NaCl, 1x protease inhibitor cocktail, and 0.5 mM PMSF), and treated with 105 Units of MNase (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, LS004798) per 40 million cells for 10 min at 37 °C. Reaction was quenched by adding 10 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, 80 mM NaCl, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.2% SDS. Nucleosomes were solubilized by sonication using Covaris S220 (160 peak incidental power, 5% duty factor, 200 cycles/burst, 45” ON-30” OFF) 6-times. One percent Triton X-100 was added to the chromatin and insoluble chromatin was removed using centrifugation. Chromatin concentration was measured using qubit and spike-in chromatin (mouse prepared in the same way) was added at a 1:40 ratio. Chromatin was incubated with primary antibodies overnight, for MPP8, TASOR, PPHLN1 and TASOR2, (Table 2) 80 μg of chromatin was incubated with 1.14 μg antibody (3.5 μg for TASOR2). Antibodies was captured using Dynabeads for 4 h at 4 °C and washed 3x using RIPA buffer, 2x using RIPA + 300 mM NaCl and 2x with LiCl buffer. Chromatin was reverse crosslinked at 65 °C overnight in 10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, and 1% SDS. The next day chromatin was incubated with RNase A for 1 h at 37 °C and proteinase K for 2 h at 55 °C and DNA was purified using PCR purification columns. Eluted DNA was diluted 1:10 for qPCR analysis (using primers in Table 3). Sequencing libraries were prepared using NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina with NEBNext Multiplex Unique Dual Oligos. Sequencing was performed on a NovaSeq6000 at the UW Biocore Sequencing Facility, paired end 150 bp for 15 million reads each sample. ChIPs were performed in at least two biological replicates with similar results, data in the qPCR figures show technical replicates.

ChIP-Sequencing analysis

Reads that passed quality score were aligned to mouse (mm9) or human (hg38) genomes using bowtie2 (parameters: -q -v 2 -m 2 -a –best –strata) (Langmead et al., 2009). Sample normalization factor was determined as ChIP-Rx = 10^6 / (total reads aligned to exogenous reference genome) or RPKM = 10^6 / (total aligned reads). Sam files were converted to bam files using samtools32. Bigwig files were generated using deeptools (-bs 50 –smoothLength 600)33. Peaks were called using MACS234. Motif analysis and peak annotation was done by HOMER35. Deeptools and IGV genome browser33,36 was used for data visualization of the data in this publication along with datasets from the ENCODE portal (https://www.encodeproject.org/) with the following identifiers: ENCFF198SGR, ENCFF559ODJ, ENCFF559WCY, ENCFF139FMU, and ENCFF503UFO.

RT-qPCR

Cell were grown as described above and 48 h before harvest cells were grown at 0.7 million cells/mL in fresh media for growth normalization. Cells were collected for RNA extraction through centrifugation at 300xg for 3 min and lysed in Tryzol and frozen for future use. QuickRNA miniprep (Zymo) kit was used for further purification and DNAse I digestion off column. All eluted RNA was kept at -80C for stability. Reverse transcription was performed with the Promega GOScript RT master mix and primed with random hexamers. qPCR was performed with primers found in Table 3 and POWER SYBR Green Master Mix. Program: Initial 95 °C for 10”, then 95 °C for 20″, 60 °C for 30″, 72 °C for 20″ (52 cycles).

RNA-sequencing

The quality of RNA preparation was assessed using RIN scores based on Bioanalyzer analysis. 500 ng of RNA was used for RNA library preperation using the NEBNext rRNA Depletion Kit, NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina, and NEBNext Multiplex Unique Dual Oligos. Sequencing was performed on a NovaSeq6000 at the UW Biocore, paired end 150 bp for 15 million reads each sample. Two biological replicates were completed for each experiment.

RNA-sequencing analysis

Reads that passed quality score were aligned human (hg38) transcriptome (ENSMBL for host genes and NCBI for transposable elements) using STAR -2.7.8a and the follow parameters (--quantMode TranscriptomeSAM GeneCounts)37. For host genes Salmon and EdgeR were used for differential expression analysis38,39. All analysis were done with two biological replicates. Data was visualized using ggplot230.

TASOR2 antibody generation

A truncation of TASOR2 (S993-V1633) with an N- and C-terminal 6xHis tag was cloned into Pet28b bacterial expression vector and transformed into Rosetta cells. Cells were grown at 37 °C under kanamycin selection until reaching an OD of 0.7-0.8. The cultures were induced with 100 mM IPTG at 37 °C for 3 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (5000xg for 10 min) and resuspended in resuspension buffer (50 mM Na-phosphate (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, 1 mM PMSF). Cells were lysed using a French press. After centrifugation at 18000xg for 15 min, the lysate was loaded onto Ni-NTA beads equilibrated with resuspension buffer and incubated with agitation for two hours at 4 °C. The flow-through was discarded, then beads were washed with wash buffer 1 (6.2 M Gu-HCl, 500 mM NaCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol), then wash buffer 2 (6.3 M Gu-HCl, 1 M NaCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol), then wash buffer 3 (150 mM NaCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol). The protein was then eluted with wash buffer 3 with 5 M imidazole, pH 8. The purified protein was sent to Sino Biological for generation of a rabbit polyclonal antibody.

Statistics and reproducibility

For all Western blot analyses at least three independent biological replicates were assessed. Independent knockout clones were generated for all HuSH subunits used for immunoblots, RNA-seq, ChIP-seq, and qRT-PCR data.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Total RNA-sequencing and ChIP-sequencing data are available on the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus database. Accession numbers for the publicly available data are: [GSE234279] for ChIP-sequencing data on the HUSH complex, and [GSE234280] for RNA-sequencing data. All mass spectrometry data are available via ProteomeXchange with identifier [PXD049085]. All data is available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data for all figures are provided with this paper. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Tchasovnikarova, I. A. et al. Epigenetic silencing by the HUSH complex mediates position-effect variegation in human cells. Science 348, 1481–1485 (2015).

Tchasovnikarova, I. A. et al. Hyperactivation of HUSH complex function by Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease mutation in MORC2. Nat. Genet. 49, 1035–1044 (2017).

Timms, R. T., Tchasovnikarova, I. A., Antrobus, R., Dougan, G. & Lehner, P. J. ATF7IP-mediated stabilization of the histone methyltransferase SETDB1 is essential for heterochromatin formation by the HUSH complex. Cell Rep. 17, 653–659 (2016).

Liu, N. et al. Selective silencing of euchromatic L1s revealed by genome-wide screens for L1 regulators. Nature 553, 228–232 (2018).

Tunbak, H. et al. The HUSH complex is a gatekeeper of type I interferon through epigenetic regulation of LINE-1s. Nat. Commun. 3, 54–67 (2020).

Seczynska, M., Bloor, S., Cuesta, S. M. & Lehner, P. J. Genome surveillance by HUSH-mediated silencing of intronless mobile elements. Nature 601, 440–445 (2021).

Douse, C. H. et al. TASOR is a pseudo-PARP that directs HUSH complex assembly and epigenetic transposon control. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–16 (2020).

Robbez-Masson, L. et al. The HUSH complex cooperates with TRIM28 to repress young retrotransposons and new genes. Genome Res. 28, 836–845 (2018).

Spencley, A. L. et al. Co-transcriptional genome surveillance by HUSH is coupled to termination machinery. Mol. Cell 83, 1623–1639.e8 (2023).

Zhu, Y., Wang, G. Z., Cingöz, O. & Goff, S. P. NP220 mediates silencing of unintegrated retroviral DNA. Nature 564, 278–282 (2018).

Tsusaka, T. et al. Tri-methylation of ATF7IP by G9a/GLP recruits the chromodomain protein MPP8. Epigenet. Chromatin 11, 56 (2018).

Marnef, A. et al. A cohesin/HUSH-and LINC-dependent pathway controls ribosomal DNA double-strand break repair. Genes Dev. 33, 1–16 (2019).

Müller, I. et al. MPP8 is essential for sustaining self-renewal of ground-state pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Commun. 12, 3034 (2021).

Prigozhin, D. M. et al. Periphilin self-association underpins epigenetic silencing by the HUSH complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 10313–10328 (2020).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021).

Schöpp, T. et al. The DUF3715 domain has a conserved role in RNA-directed transposon silencing. RNA https://doi.org/10.1261/RNA.079693.123 (2023).

Li, S., Wang, L., Berman, M., Kong, Y.-Y. & Dorf, M. E. Mapping a dynamic innate immunity protein interaction network regulating type I interferon production. Immunity 35, 426–440 (2011).

Hubel, P. et al. A protein-interaction network of interferon-stimulated genes extends the innate immune system landscape. Nat. Immunol. 20, 493–502 (2019).

Schoggins, J. W. & Rice, C. M. Interferon-stimulated genes and their antiviral effector functions. Curr. Opin. Virol. 1, 519–525 (2011).

Imbeault, M., Helleboid, P.-Y. & Trono, D. KRAB zinc-finger proteins contribute to the evolution of gene regulatory networks. Nature 543, 550–554 (2017).

Jensvold, Z. D., Christenson, A. E., Flood, J. R. & Lewis, P. W. Interplay between Two Paralogous Human Silencing Hub (HuSH) Complexes in Regulating LINE-1 Element Silencing. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.12.28.573526 (2023).

Danac, J. M. C. et al. Competition between two HUSH complexes orchestrates the immune response to retroelement invasion. Mol. Cell 84, 2870–2881.e5 (2024).

Matkovic, R. et al. TASOR epigenetic repressor cooperates with a CNOT1 RNA degradation pathway to repress HIV. RNA 29, 1471–1480 (2023).

Chougui, G. et al. HIV-2/SIV viral protein X counteracts HUSH repressor complex. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 891–897 (2018).

Machida, S. et al. Exploring histone loading on HIV DNA reveals a dynamic nucleosome positioning between unintegrated and integrated viral genome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1913754117 (2020).

Yurkovetskiy, L. et al. Primate immunodeficiency virus proteins Vpx and Vpr counteract transcriptional repression of proviruses by the HUSH complex. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 1354–1361 (2018).

Cuellar, T. L. et al. Silencing of retrotransposons by SETDB1 inhibits the interferon response in acute myeloid leukemia. J. Cell Biol. 216, 3535–3549 (2017).

Gu, Z. et al. Silencing of LINE-1 retrotransposons is a selective dependency of myeloid leukemia. Nat. Genet. 53, 672–682 (2021).

Zhang, Y., Wen, Z., Washburn, M. P. & Florens, L. Refinements to label free proteome quantitation: How to deal with peptides shared by multiple proteins. Anal. Chem. 82, 2272–2281 (2010).

Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer-Verlag New York, 2016).

Perez-Riverol, Y. et al. The PRIDE database resources in 2022: a hub for mass spectrometry-based proteomics evidences. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D543–D552 (2022).

Danecek, P. et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience 10, 1–4 (2021).

Ramírez, F. et al. deepTools2: a next generation web server for deep-sequencing data analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W160–W165 (2016).

Zhang, Y. et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 9, 1–9 (2008).

Heinz, S., Benner, C., Spann, N. & Bertolino, E. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol. Cell 38, 576–589 (2010).

Robinson, J. T. et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 24 (2011).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013).

Patro, R., Duggal, G., Love, M. I., Irizarry, R. A. & Kingsford, C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods 14, 417–419 (2017).

Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by funding from National Institutes of Health, P01CA196539; the Greater Milwaukee Foundation; the Sidney Kimmel Foundation (Kimmel Scholar Award). P.W.L. is a Pew Scholar in the Biomedical Sciences. Z.J.D. was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (GRFP).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.D.J., J.R.F., and A.E.C. performed the experiments. Z.D.J, J.R.F, A.E.C., and P.W.L. conceived the study. Z.D.J. performed the bioinformatics analysis. Z.D.J, J.R.F, A.E.C., and P.W.L. prepared the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jensvold, Z.D., Flood, J.R., Christenson, A.E. et al. Interplay between Two Paralogous Human Silencing Hub (HuSH) Complexes in Regulating LINE-1 Element Silencing. Nat Commun 15, 9492 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53761-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53761-w

This article is cited by

-

The HUSH complex facilitates the exit of pluripotency

Communications Biology (2025)

-

Transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of transposable elements and their roles in development and disease

Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology (2025)