Abstract

Creating statistically equivalent virtual microstructures (SEVM) for polycrystalline materials with complex microstructures that encompass multi-modal morphological and crystallographic distributions is a challenging enterprise. Cold spray-formed (CSF) AA7050 alloy containing coarse-grained prior particles and ultra-fine grains (UFG) and additively manufactured (AM) Ti64 alloys with alpha laths in beta substrates. The paper introduces an approach strategically integrating a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) for multi-modal microstructures with a synthetic microstructure builder DREAM.3D for packing grains conforming to statistics in electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) maps for generating SEVMs of CSF and AM alloy microstructures. A robust multiscale model is subsequently developed for self-consistent coupling of crystal plasticity finite element model (CPFEM) for coarse-grained crystals with an upscaled constitutive model for UFGs. Sub-volume elements are simulated for efficient computations and their responses are averaged for overall stress-strain response. The methods developed are important for image-based micromechanical modeling that is necessary for microstructure-property relations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Materials engineering has witnessed unprecedented growth in recent times, enabled by major advances in manufacturing technologies like 3D printing and advanced materials modeling methods. These advances are creating avenues for material design to reach new heights in performance and life-related properties that would have been previously unachievable. Robust microstructure-informed hierarchical mechanistic modeling for structure-property-response relations is at the core of these developments. The models enable material designers to utilize the full potential of these materials by predicting important deformation and extreme behavior characteristics like fracture and fatigue response.

Image-based micromechanical models rely on the creation of 3D virtual microstructures, mostly through synthetic image reconstruction from 3D experimental data on sample microstructural volumes. Such experimental data may be extracted from electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) and/or scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of serially sectioned samples1,2, or from computed tomography (CT)3. Deterministic models of the microstructure, developed from limited experimental data4, do not accurately represent variations in the microstructural descriptors that are essential for effective micromechanical modeling. A more compelling approach is to create synthetic/virtual microstructures that exhibit statistical equivalence to experimentally extracted images, in terms of distribution and correlation functions of morphological and crystallographic descriptors. For meaningful prediction of a range of response functions, these statistically equivalent virtual microstructures (SEVM)5,6,7,8 must adequately capture the statistics of characteristic variables, e,g, grain or inclusion size and shape, crystallographic orientation, grain misorientations and their correlations9,10. For efficient and accurate micromechanical simulations, the statistically equivalent RVE (SERVE) has been introduced in5,6,7,11,12,13, as the smallest SEVM with statistical functions of microstructural descriptors that are optimally convergent to the experimental measurements of the microstructure. The SERVE is further sub-classified as microstructure-based SERVE (M-SERVE) for convergent statistical functions of morphological and crystallographic descriptors and as property-based SERVE (P-SERVE) for convergent target material properties and response functions5,7,8,12.

Within the Integrated Computational Materials Engineering (ICME) domain, a variety of computational models and tools have emerged for creating image-based synthetic microstructures. These include the DREAM.3D software9,10,14, Neper15, MicroStructPy16, Kanapy17, MicroLib18, among others. Using Voronoi tesselation19, Laguerre-Voronoi tessellation20, sphere packing21,22,23,24, Markov random field algorithms25, cellular automata26, dilation-erosion27 or spatial correlations functions28,29,30, these tools generate SEVMs by selectively matching data from experimental microstructures. While these tools have been typically effective for microstructures with unimodal distribution of heterogeneities like grains and particles, they tend to be ineffective when regenerating microstructures with multi-modal distributions of morphological and crystallographic features. For example, it is difficult to generate polycrystalline microstructures containing dispersed intragranular precipitates8,31 or localized grain clusters in micro-textured regions of the microstructure, with acceptable fidelity32. Many of the emerging materials exhibit high levels of microstructural complexities as a consequence of their processing routes, such as deformation followed by heat treatment like annealing33, severe plastic deformation34, sintering35, cold spray forming (CSF)36, or metals additive manufacturing37.

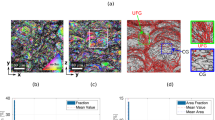

Figure 1a–c shows electron back-scattered diffraction (EBSD) maps of a cold spray-formed (CSF) microstructure of the aluminum alloy AA7050 with a bimodal grain size distribution. Cold spray-forming is a solid-state coating deposition technique, in which deposition layers are formed by the collision and subsequent bonding of particle-substrate and particle-particle interactions. Particle impact results in deformation-induced recrystallization in the CSF layers36, which leads to a bimodal polycrystalline microstructure composed of recrystallized ultra-fine grains (UFG) and deformed coarse grains (CG) within the prior particles. This is shown in Fig. 1a, b for two orthogonal XY and YZ planes, It shows deformed CGs in prior particles that are interjected into substrates containing UFGs. The bimodal grain size has been associated with higher yield strength and ductility38. While a grain size threshold can be used to separate CGs and UFGs, kernel-averaged misorientation (KAM)39,40 is a more effective means of this separation for bimodal microstructures with recrystallized grains. Figure 1c shows zones and grain boundaries of UFGs (in red) and CGs (in black) using grain size and KAM thresholds. Developing image-based microstructural models of such materials with multimodal distributions is a very challenging enterprise. Figure 1d, e shows histograms of the number and area fractions of the grain size generated from the 2D EBSD maps of the polycrystalline microstructure in Fig. 1b. In the histogram, the size of the α − th grain in an ensemble with an area sα is represented by an equivalent grain diameter \({d}^{\alpha }=2\sqrt{{s}^{\alpha }/\pi }\). Each bin in the histogram spans a 0.5 mm grain size. The number and area fractions in the histogram for the i − th bin containing ni grains are respectively computed as:

where NG is the total number of grains in the EBSD map with a total area of S. The area fraction distribution of the grain size in Fig. 1e indicates a multi-modal distribution that deviates considerably from the log-normal distribution typically used in synthetic microstructure generators like DREAM.3D14.

For cold-spray alloy: a Low-resolution inverse pole figure (IPF) of the Z-orientation map in the XY plane showing standard triangle colors for the orientation maps, b corresponding low-resolution IPF of the Z-orientation map in the YZ plane, c high-resolution band contrast map of the boxed region in b with grain boundaries of ultra-fine grains (UFG) and coarse grains (CG) colored in black and red respectively (grain boundaries delineated by an assigned misorientation angle). In c, the green and blue panels show details of the UFGs and CGs. Histograms of d the number fraction and e the area fraction of the equivalent grain diameter indicating multimodal grain size distribution. For Ti64 alloy manufactured by LBPF: IPF in the f XY and g YZ planes.

Computational studies involving bimodal microstructures are rather limited in the literature32,41,42 due to their inherent complexities. In most of these studies, the microstructure has been limited to 2D, and the coarse grains have been represented using simplified geometric constructs. The Neper software15 has been used to generate a 2D bimodal microstructure consisting of large grains and smaller equiaxed grains in ref. 32, while a bimodal Laguerre-Voronoi tessellation method has been used in ref. 19. In ref. 41, the larger grains (CGs) in bimodal microstructures are represented as circles in a continuum matrix representing the smaller UFGs that are modeled using continuum plasticity. The CGs are represented by 2D ellipses and modeled using continuum plasticity in ref. 42, while the UFGs are represented using 2D Voronoi cells and modeled by crystal plasticity. However, for many emerging materials, the CG domain can be quite complex, and simplified geometric models for multi-modal regions are likely to ignore important features that have consequences in the overall behavior and life.

The laser powder bed fusion (LPBF)-based additively manufactured Ti-6Al-4V or Ti64 alloy is another example material that poses considerable challenges in image-based microstructure modeling. The material exhibits a Widmanstätten or basket-weave microstructure consisting of α laths and parent β phase with HCP and BCC crystalline structures, respectively, as shown in Fig. 1f, g. Upon re-solidification of the powder melt-pool in the LPBF process, the material first assumes the β phase till it cools below the β transus temperature when 12 α lath variants nucleate and grow to proliferate the entire microstructure. The high rates of cooling in the AM processes lead to frequent nucleation, resulting in smaller α laths and the Widmanstätten type microstructures43. The crystallographic orientation of each of the 12 α lath variants is related to that of the parent β grain through a unique Burgers relationship, (0001)α∥(101)β and \({[11\bar{2}0]}_{\alpha }\parallel {[\bar{1}11]}_{\beta }\), giving rise to 12 unique variants. Image-based modeling of synthetic Widmanstätten microstructures is rather limited in the literature. While the elongated α laths in LPBF-based Ti64 alloy microstructures can be of arbitrary needle-like shapes43, most studies have approximated their shape as ellipsoids or super-ellipsoids37,44. Accurate statistical representation of the lath morphologies in the virtual microstructural models can lead to better predictions of their properties and performance.

In recent years, machine learning-based virtual microstructure generators have shown considerable promise, e.g., in refs. 45,46,47,48,49,50. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)51,52, which incorporate a deep learning architecture consisting of two neural networks competing against each other in a zero-sum game framework, are emerging as popular generative tools in this operation. GANs are a powerful class of neural networks for unsupervised learning that generate new, synthetic data resembling known data distribution. They have been used to generate topologically complex binary and three-phase microstructures in refs. 45,46,48,49,50. In ref. 48, the authors have compared the results of a microstructural model of a three-phase solid oxide fuel cell electrode, generated by GANs with those generated by the DREAM.3D software. Their studies have concluded that GANs can create more realistic three-phase microstructures in terms of visual resemblance, statistics, and topological properties. While their potential is well recognized, the application and effectiveness of GANs for creating multi-domain heterogeneous material microstructures, such as polycrystals, remain to be achieved. A GAN-based computational tool, SliceGAN has been recently developed in ref. 46 for generating 3D microstructures from 2D data in binary, three-phase, or polycrystalline microstructures. While SliceGAN is able to generate high-fidelity binary and three-phase microstructures, the quality diminishes drastically for polycrystalline microstructures with insufficient grain boundary identification.

The goal of this paper is two-fold. First, it uses a combination of GANs and conventional synthetic microstructure builders to create statistically equivalent virtual microstructures (SEVMs) for complex heterogeneous (including multimodal) materials that are difficult to model otherwise. The second objective is to use this virtual microstructure to develop a concurrent multiscale model for simulating these microstructures that inherently have multiple scales in their morphology and crystallography. The paper develops robust image-based micromechanical models for complex polycrystalline microstructures with multimodal grain-size distributions, as shown in Fig. 1. A focus is on the cold spray-formed (CSF) Aluminum alloy AA7050, whose microstructure has a bimodal grain size distribution in the form of CGs and UFGs. While some computational studies have focused on the CSF particle deposition process53,54,55,56, there is very little literature on modeling the deformation and material behavior of CSF materials57. A primary reason for this paucity is the difficulties encountered in generating 3D SEVMs and SERVEs for analyzing the complex bimodal microstructures shown in Fig. 1, with the conventional synthetic microstructure generation tools. The large size discrepancy between the coexisting CGs and UFGs in the microstructure necessitates a multiscale modeling approach for computational feasibility. In this approach, the CG domains are explicitly represented as polycrystalline ensembles, while the UFGs are represented by a homogenized domain, for which the response is obtained by upscaling the high-resolution microstructural UFG behavior. Correspondingly, it is important to separate these domains in the construction of microstructural SEVMs. The creation of 3D SEVMs from 2D EBSD maps of these bimodal microstructures, using commonly used synthetic generation software like DREAM.3D14 and SliceGAN46, are faced with significant difficulties like inappropriate representation of the morphological shapes and sizes of prior particles and the UFGs in the EBSD scans of Fig. 1a, b. The discrepancies are discussed in the Discussion section of this paper under the heading Challenges with conventional synthetic builders. These shortcomings are overcome in this paper by integrating the GANs-based generation of 3D binary microstructures with the DREAM.3D software-based14 grain-packing conforming to the statistics in EBSD maps. The methodology developed is applicable to a broader class of complex heterogeneous microstructures, e.g., the LPBF-based additively manufactured Ti-6Al-4V or Ti64 alloy with a Widmanstätten microstructure as shown in the figure in the results Generating SEVM for additively manufactured Ti6Al4 alloy.

This paper is organized as follows. The Results section shows the results of the integrated SliceGAN-DREAM.3D platform for generating 3D SEVMs of bimodal CSF Al7075 and AM Ti64 microstructures. The mechanical response of the CSF Al7075 SEVM is simulated and compared with experiments. The Discussion section summarizes the importance of the methods developed and proposes avenues for improvement. The Methods section discusses the specifics of the material and processing conditions and developmental steps for SliceGAN and DREAM.3D for the creation of the SEVMs. Additional information is provided in the accompanying Supplementary Material document.

Results

The results correspond to a robust methodology that is developed for image-based micromechanical modeling of the cold spray-formed (CSF) AA7050 alloy. It includes the generation of 3D SEVMs of topologically complex bimodal microstructures containing both CGs and UFGs, along with a multiscale model for the material response. To demonstrate the versatility of the SEVM generation process, the methodology is also applied to an additively manufactured Ti64 alloy. The SEVMs are generated using a strategic combination of a GAN-based SliceGAN code46 and a conventional synthetic microstructure generator software DREAM.3D14. The material and processing condition specifics are discussed in the Methods section. The SEVM reconstruction methodology generally requires at least two orthogonal EBSD maps for input information on the bimodal domain morphology and an additional high-resolution map that provides high-quality statistical information on grain morphology and crystallography. The following sections detail the results of the SEVM reconstruction and micromechanical modeling process.

Characteristics of experimentally acquired EBSD images of CSF AA7050 alloy

The impact during the CSF deposition process produces a geometry change from roughly spherical particles to lune-like or imbricated prior particles in ref. 58. During impact, deformation-induced recrystallization takes place and results in microstructures with a bimodal grain size distribution. Microstructures of the CSF AA7050 alloy are analyzed using an Oxford Instruments EBSD system, attached to a JEOL 7000 field emission Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM). The EBSD images are treated using the MTEX toolbox in a Matlab environment59, and the acquired low-resolution EBSD maps in the XY and YZ planes, impacted in the Z-direction, are shown in Fig. 1a, b respectively. Each of these EBSD maps is scanned with a step size of 0.5 mm and has a size of 0.15 mm × 0.15 mm. The black zones in the EBSD maps correspond to a large number of recrystallized, ultra-fine grains (UFGs). The UFG domain generally envelops the prior particles in a complex 3D network. In the XY plane, the initial spherical geometry of the particles is preserved, while the YZ plane map shows evidence of significant deformation with impact, resulting in a deviation from the spherical shape. The CGs within the prior particles do not recrystallize but deform with the parent particle as a whole. Figure 1c corresponds to a 50 mm × 50 mm high-resolution EBSD map, scanned with a step size of 0.166 mm. The three EBSD scans at different resolutions are necessary for generating the 3D SEVMs using the proposed methodology. The low-resolution EBSD maps are assumed to provide a statistically significant sample size of prior particles for the reconstruction of prior particle morphology, while the high-resolution map provides the necessary morphological and crystallographic information on the UFGs and CGs.

The deformed CGs can be differentiated from the recrystallized UFGs in the EBSD maps by using measures like the Kernel Average Misorientation (KAM) and the Grain Average KAM (GAKAM)39,40, in addition to the grain size distribution. The KAM measures, which are based on the lattice misorientation in the grain interior induced by deformation, are found to be ideal for the CS-formed microstructures. The parameter KAMi represents the average misorientation angle θij between a point i and its neighbor j, (j = 1 ⋯ n) within the same grain g. The parameter GAKAMg is a property for a grain g that is calculated as the average KAMi over i = N points in the grain and is expressed as:

The KAM and GAKAM vary with the geometrically necessary dislocations (GNDs)60 and are effective in differentiating the recrystallized UFGs from the CGs, which have a higher KAM value. Figure 2a, b respectively, show the GAKAM map and the GAKAM histogram of the EBSD map in Fig. 1a. There is a direct correlation between the low values of GAKAM colored in blue in Fig. 2a and the zones around the prior particles in Fig. 1a. The GAKAM distribution exhibits a clear threshold between the two types of grain populations, where the peak around 0 degrees corresponds to the UFGs and the remaining parts of the histogram correspond to CGs.

Generating 3D SEVM of bimodal AA7050 microstructures

The generation of 3D SEVMs from orthogonal 2D EBSD maps of the bimodal microstructures in Fig. 1a, b is based on the statistics of physically relevant microstructural features. The large size disparity between the CGs and UFGs necessitates a multiscale modeling approach, in which, the CG domains are explicitly represented as polycrystalline ensembles, whereas the UFGs are represented as homogenized domains whose response is obtained by upscaling the high-resolution microstructural behavior. Correspondingly, it is important to separate these domains in the construction of microstructural SEVMs, as well as their simulations.

Integrating SliceGAN with the synthetic builder DREAM.3D for creating SEVMs

As detailed in the Discussion section, the GANs-based approaches in SliceGAN46 are capable of producing good binary or three-phase microstructures, while the synthetic microstructure builder DREAM.3D software14 is capable of packing grains conforming to the experimental statistics in EBSD maps. Consequently, their complementary advantages are strategically integrated to create the bimodal microstructures of the CSF alloy AA7050 using a methodology detailed in the Methods section.

Figure 3a shows a SEVM containing 24924 coarse grains in the prior particles that are reconstructed by the integrated SliceGAN-DREAM.3D platform. The figure illustrates details of the prior particle morphology with the included grain crystallography at different locations in the SEVM. The crystallographic orientations are assigned to the grains of the SEVM by sampling from the experimental EBSD data to yield statistical equivalence to the microstructural texture. The grain-to-grain misorientation angle distribution is augmented by introducing a crystallographic orientation swapping algorithm. Figure 3b–e compares the SEVM texture (pole figures), misorientation angle distribution, grain size distribution, and grain aspect ratio distribution with those from the EBSD maps. The texture, misorientation, and equivalent diameter generally show very good agreement. The aspect ratio distribution in Fig. 3e, however, shows a difference with the SEVM distribution peaking at a higher aspect ratio. Note that this kind of misfit is a common occurrence with stereology techniques when microstructural characteristics are mapped from 2D to 3D. A better plot to understand the accuracy is shown in the first figure in Discussion Section I, where 2D slices of the 3D SEVM, shown in Fig. 3a, are compared with the 2D EBSD data.

a Integrated SliceGAN-DREAM.3D platform-generated SEVM (Insets show two prior particles with the included CG morphology and crystallography). Comparison of the b texture (pole figures), c misorientation angle distribution [for EBSD n = 3643, for SEVM n = 279079], d grain size distribution [for EBSD n = 771, for SEVM n = 24924], and e aspect ratio distribution [for EBSD n = 771, for SEVM n = 24924], of the SEVM and electron back-scattered diffraction (EBSD) data.

Modeling SEVMs for mechanical response using a multiscale approach

The multiscale modeling approach combines two different models to overcome the length-scale difference between the CGs and UFGs. The mechanical behavior of CG domains is described using a crystal plasticity constitutive model8, while the mechanical behavior of UFGs is described using an upscaled constitutive model (UCM) following a construct introduced in refs. 61,62. The micromechanical constitutive models are explained in detail in Supplementary Material: Micromechanical crystal plasticity and upscaled constitutive models.

The large size of the SEVM containing a high number of particles with included CGs makes direct FE analysis using crystal plasticity FEM, computationally prohibitive. To overcome this limitation, the SEVM needs to be divided into smaller sub-volume elements (SVE) for direct FE analysis to be performed over each volume element. Subsequently, the overall mechanical response of each SVE can be averaged to obtain the overall SEVM response. For viable analysis, in terms of overall accuracy and reduced computational speed, it is important to determine the number of SVEs that should be considered in the averaging. In Supplementary Material: FE simulation strategy of the SEVMs for mechanical response, two convergence tests are performed to assess this number. Convergence analysis of the microstructure-based and property-based statistical volume elements (M-SVE and P-SVE), shows that approximately 40 SVE samples are necessary to capture the properties of the SEVM presented in Fig. 3a.

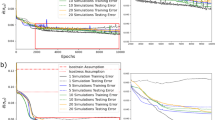

Figure 4a, c respectively, show the statistically equivalent bimodal microstructure used for calibration and different P-SVEs extracted from the SEVM in Fig. 3a. Consistent with the experiments, the SEVM and SVE simulations are conducted under uniaxial tension loading in the X-axis (raster direction) for a constant strain rate of \(\dot{\varepsilon }=\)0.001s−1. Figure 4b, d shows the volume-averaged equivalent true stress-true strain responses of the calibration model and different SVEs, respectively, using the crystal plasticity (CP) model and upscaled constitutive model (UCM) with calibrated parameters. The calibration model in Fig. 4b agrees very well with the experimental data, confirming that the optimization procedure has converged correctly. More importantly, the mean average response of the SVEs in Fig. 4c also agrees very favorably with the experimental data in Fig. 4d. The SVE v-1 consists of 459 CGs in three prior particle clusters, whereas the SVE v-2 consists of 464 CGs in one dominant cluster. Figure 4e shows the contour plots of the Cauchy stress component σxx, and Fig. 4f shows the effective plastic strain εp for loading in the X-direction corresponding to a true strain of ~ 2.0 × 10−2. Significant stress concentration is observed at the interfaces of the prior particles containing CGs and the UFG domains in the SVE v-1. For the SVE v-2, the stress concentration is found in the grain boundaries of the CGs close to the CG-UFG interface. A similar pattern is found in the effective plastic strain, but most of the high points are located within the CGs. The difference in local stress concentrations is reflected in the volume-averaged stress-strain response with different yield stresses and hardening slopes.

a A statistically equivalent bimodal microstructure containing coarse grains (CGs) embedded in the ultra-fine grain (UFG) domain in translucent red, used for calibration, b comparison of the post-calibration stress-strain curve with experiments (the experiment range corresponds to the maximum and minimum stress values that were observed), c different statistical volume elements (SVEs) taken from the SEVM created using the integrated SliceGAN-DREAM.3D platform of the cold spray-formed AA7050 alloy, d comparison of the range of stress-strain response curves generated by different SVEs with the experimental data, as well as the average response; Contour plots of e the stress component σxx in Pa and f effective plastic strain εp for the SVEs v-1 and v-2 at a strain of ~ 2.1 × 10−2. The simulations are performed with an applied strain rate of \(\dot{\varepsilon }=\)0.001s−1. In b and d, Range refers to the variation of different curves, and Mean refers to the average of the different curves.

Generating SEVM for additively manufactured Ti6Al4 alloy

The methodology to create SEVMs for the CSF AA7050 alloy is next tested for the additively manufactured Ti-6Al-4V or Ti64 alloy with a Widmanstätten microstructure, discussed in the Introduction section. The microstructures shown in Fig. 1f, g consist of 12 variants, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 12a, b. In this case, the input to SliceGAN incorporates 12 masks that describe every variant individually, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 12c–f. Figure 5a shows the 3D SEVM with 12 variants generated by the integrated SliceGAN-DREAM.3D platform. The SEVM presents a visual resemblance with the elongated laths and complex intersection between variants in the EBSD scans. The volume fraction of every variant of the SEVM and the two EBSD planes is shown in Fig. 5b with satisfactory agreement. For the volume fractions of the EBSD maps that are different, e.g., for variants 10 and 12 in Supplementary Fig. 12e, f, the SEVM values lie between those of the EBSD maps. The crystallographic orientation of every variant is taken from the EBSD data, and the grains are segmented. Figure 5d–f compares the distributions of grain size, aspect ratio, and misorientation angle of the SEVM and the EBSD planes. The aspect ratio and misorientation angle distributions of the SEVM are similar to the EBSD maps. The grain size distribution of the SEVM peaks at a smaller value than the EBSD planes. In Fig. 5c, the pole figures of the SEVM and the EBSD maps are depicted. The pole figures of the SEVM exhibit the essential EBSD characteristics, as is expected.

a The generated SEVM; comparison of b volume fraction of the 12 variants, c texture (pole figure) in the frequency of specific orientations (in radians), d grain size distribution [for SEVM n = 1260, for EBSD XY n = 1251, for EBSD YZ n = 1057], e aspect ratio distribution [for SEVM n = 1260, for EBSD XY n = 1251, for EBSD YZ n = 1057], and f misorientation angle distribution in degrees [for SEVM n = 12770, for EBSD XY n = 6466, for EBSD YZ n = 5584]. In c–f, the data is combined for all the 12 variants.

Discussion

Material properties, especially those corresponding to extreme values like fatigue life and ductility, are very sensitive to the morphological and crystallographic aspects of the microstructure63. Experimental studies of fatigue life in CSF Al alloys64 have shown that cracks initiate in the prior particle substructure near the CG grain boundaries and have a strong influence on specimen failure. Studies in ref. 57 have observed that cracks nucleate near the surface from particle-particle bonding defects, and subsequently evolve in the CG domain along the particle boundaries. The prior particle boundaries and the CG microstructure are major determinants of crack evolution in CSF alloys. Similarly, the fatigue crack behavior of additively manufactured Ti-6Al-4V alloy with a Widmanstätten microstructure has been reported to be highly sensitive to the crystallography and the morphology of the laths65. This underscores the importance of developing high-fidelity SEVMs, along with their implementation in a simulation tool for determining mechanical response.

The methodology developed in this paper not only demonstrates a viable path for generating statistically equivalent material microstructures for complex multi-modal and heterogeneous microstructures but also introduces a robust multiscale modeling technique that can overcome the challenges of accounting for material features at a range of length scales. The proposed computational framework on GANs-based virtual microstructure generation, along with the multiscale modeling methods, is expected to open the door for addressing structure-property relations in complex materials that have thus far been difficult with conventional models, especially with respect to extreme properties.

Challenges with generating SEVMs using conventional methods

Various challenges are encountered in 3D SEVM generation from morphologically complex 2D EBSD maps, using commonly used synthetic generation software like DREAM.3D and SliceGAN alone. Figure 6a–c shows SEVMs generated by (i) the DREAM.3D software, (ii) SliceGAN software, and (iii) the integrated SliceGAN-DREAM.3D platform, respectively. The major steps in executing each methodology are discussed in the Methods section. Figure 6d–f shows a few key distribution and correlation functions obtained from SEVMs, viz., the 2-point correlation of the UFG domain, grain size, aspect ratio, and misorientation angle distributions.

a DREAM.3D, b SliceGAN, and c integrated SliceGAN-DREAM.3D platform. Comparison of SEVM microstructural characteristics with those from EBSD maps: d Prior particle 2-point correlation S2 function of the sum of 5 equally spaced and normalized slices of each SEVM in each orthogonal plane (XY (top) and YZ (bottom)), and the corresponding extremum of the central ellipse measured for a two-point correlation value of S2 = 0.25 across each axis, e PDFs of the major grain features viz. grain size, aspect ratio, and misorientation for each SEVM measured as 2D slices in the YZ plane, and f texture (pole figures).

The DREAM.3D-generated SEVM in Fig. 6a exhibits several discrepancies. First, the shape of prior particles in the CG domain is much more regular in comparison with those seen in the real microstructures of Fig. 1. Second, the representation of the UFG domain has a nearly constant width of approximately 2.625 mm, which is not characteristic of the real UFG domain. Furthermore, the morphological anisotropy of the DREAM.3D-generated grains, delineated by the histogram of aspect ratios in two orthogonal planes in Fig. 6e, is different from that for the EBSD maps.

The SliceGAN code46 needs amendments to receive inputs in the form of Euler angles, quaternions, grain IDs, and grain sizes for generating SEVMs. Quaternions are used to generate the SEVM in Fig. 6, and Euler angles are used for post-processing. The direct output from SliceGAN does not yield microstructures with clearly distinguishable grains. Consequently, a post-processing operation is conducted, which incorporates a minimum grain size thresholding and a watershed filter using gradients of the Euler angles computed through Sobel operators66. Additional information on the post-processing operation is given in Supplementary Material: Additional details on generating SEVMs for CSF Al7050. Figure 6d–f depicts the morphological and crystallographic characteristics of the SliceGAN-generated SEVM. While the virtual UFG and CG domains generated by SliceGAN are slightly more representative of the real microstructure, the grains are found to be generally equiaxed and larger than those observed in the EBSD maps. Furthermore, the generated texture is dissimilar to that of the EBSD maps. The misorientation angle shows two peaks, but the fraction of the peaks is incorrect. The crystallographic data can be improved through a sampling of the orientation from the experimental data, and the misfit can be reduced by using different grain size thresholds, and variations in the watershed filter. Moreover, the morphological data can be corrected through the improvement of the artificial network (AN) used in the GAN model by utilizing the difference shown in the Supplementary Material: Additional details on generating SEVMs for CSF Al7050, Supplementary Fig. 2f and the statistical data from Fig. 6 as metrics in a hyperparameter optimization algorithm.

Figure 6 d, e, Table 1 and Fig. 7 compare the two-point correlation function S228,29,30 and the distributions of major microstructural descriptors for the EBSD maps with two orthogonal sections taken from SEVMs generated by DREAM.3D, SliceGAN and the integrated SliceGAN-DREAM.3D platform.

The geometrical anisotropy of the CG domain is represented using the two-point correlation function in Fig. 6d for the XY and YZ planes. The correlation in the EBSD map shows two important characteristics. First, the XY plane shows a more circular peak in the center because the CG domain preserves the initial spherical shape of the prior particles, and it is also concentrated along the Y-direction as shown in the image labeled Plane XY of Fig. 8. Second, the YZ plane shows a more elliptical peak as the CGs are more elongated in the Y-direction after impact and it is also more concentrated along the Y-direction, as depicted in the image labeled Plane YZ of Fig. 8. The SEVM created with DREAM.3D shows a peak shape in the two planes similar to the peaks in the EBSD maps, however, the concentration of the planes is along diagonal directions that do not match those of the EBSD. The SEVM created using SliceGAN only shows poor quality in reproducing the anisotropy of the CG. The peak shows two elliptical shapes and the principal directions do not match the direction of the EBSD map. Results in Fig. 6d with the integrated SliceGAN-DREAM.3D platform are closer to the EBSD results and represent the main characteristics of the EBSD map. Table 1 shows the principal direction of the ellipsoid representing the peak and its aspect ratio, with the SliceGAN-generated SEVM being the closest to the characteristics of the EBSD map. Figure 6e shows the distribution of grain size, aspect ratio, and misorientation angle distributions on slices in two orthogonal planes. The SliceGAN-based SEVM in Fig. 6b exhibits a poor representation of the grain size and aspect ratio distributions, but a good representation of the misorientation angle distribution. On the other hand, the DREAM.3D and integrated SliceGAN-DREAM.3D platform-based SEVMs in Fig. 6a, c matches the three distributions closely, since grain-packing is achieved through DREAM.3D for both cases. Figure 7 compares the KS value for each distribution in both planes of the EBSD results with synthetic microstructures created by DREAM.3D, SliceGAN, and integrated SliceGAN-DREAM.3D platform for descriptors viz. (a) the equivalent grain size, (b) aspect ratio, and (c) misorientation distributions. While the integrated SliceGAN-DREAM.3D platform-generated SEVM has the closest grain size and misorientation angle distributions, it is interesting that the DREAM.3D-based SEVM shows slightly better results for the aspect ratio distribution as DREAM.3D has been used to pack the grain for the two methods. The difference between the KS value of the DREAM.3D and integrated SliceGAN-DREAM.3D generated SEVMs is small, possibly due to the methodology used to create the UFG domain.

Avenues for improving the proposed SEVM generation methodology

The integrated SliceGAN-DREAM.3D SEVM generator, developed in this work, is a robust enabler that can capture the local microstructural characteristics. SliceGAN learns the main characteristics of the bimodal microstructure and generates a range of microstructures to result in a rich microstructure database representing the heterogeneity of the CSF microstructures. DREAM.3D, on the other hand, readily incorporates the grain distributions and crystallographic texture in the microstructure. It should be emphasized that at least two EBSD maps are necessary to create robust 3D SEVMs.

To improve the SEVM quality, a large amount of data is needed from multiple EBSD maps for training the GAN models. This can be a significant bottleneck with respect to current data acquisition techniques. In reality, the amount of EBSD data can be rather limited for a given material under a specific processing condition. To overcome these issues, aspects of the GAN model can be enhanced to obtain the morphology and crystallography of complex polycrystalline microstructures. First, it is possible to modify images before passing them to the discriminator using a dataset augmentation technique. This step helps the model to modify and interpret every image differently. Another essential aspect of GANs is the computation of the loss function. It has been shown that the gradient penalty term in Equation (4) has limitations with respect to convergence, and regularization terms can be implemented to improve convergence and limit over-fitting67. Finally, the GANs can be modified to use EBSD data for different material pedigrees under different processing conditions, with supervised learning using the processing conditions as additional inputs in the GANs model, as well as linking GANs with variational auto-encoders (VAEs) or diffusion models. For the case of richer datasets or microstructures with different characteristics, disentanglement could potentially be an issue, and style-based generators can be used to improve the variation of generated images and disentangle the latent space68,69. These techniques are currently under investigation. Other physical properties and metrics like percolation are beyond the scope of this paper and may need additional considerations.

Methods

Material and manufacturing process descriptions

The cold spray formed AA7050 alloy

The chemical composition of AA7050 alloy, comprising prior particles and substrate material, is given in Supplementary Table 1 in Supplementary Material: Material and processing parameters and mechanical testing data. Gas-atomized AA7050 powders (Valimet, Stockton, CA, USA) are used for cold spray in this study. Feed-stock AA7050 powders have spherical morphologies and diameters smaller than 53 μm (-270 mesh). The cold spray deposition process is performed using a VRC Metal Systems Gen III high-pressure cold spray system with deposition parameters given in Supplementary Table 2 in Supplementary Material: Material and processing parameters and mechanical testing data. After deposition, the coating is removed from the substrate and machined to eliminate the wrought material substrate. Samples are prepared for EBSD characterization by mechanical polishing followed by fine polishing (3 μm and 1 μm diamond suspensions). The final polishing is performed on a vibratory polisher for 3 h with a 0.02 μm colloidal silica suspension.

Mechanical testing for material response

Mechanical tests are performed on tensile geometry based on ASTM ceramic tensile testing standards. A cold spray deposit is prepared for longitudinal and transverse loading. The specimens are sanded prior to testing to 400p grit due to the high sensitivity to surface defects. The samples are tested on an MTS Landmark 25 kN frame (Model 370.02). The tests are run at a nominal strain rate of 0.001 s−1 with a 5 mm extensometer. A typical sample and the tensile data are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1 in Supplementary Material: Material and processing parameters and mechanical testing data. The experimental data shows a difference in the ultimate strain of the samples along the longitudinal and transverse directions. On the other hand, the tensile data shows a higher deviation along the transverse direction. These results are used to calibrate the crystal plasticity (CP) and upscaled constitutive model (UCM) parameters.

The additively manufactured Ti64 alloy

The additively manufactured Ti64 alloy has a chemical composition by weight of 5.82% Al, 4% V, 0.2% Fe, 0.1% O, and the rest of Ti. The sample shown in Fig. 1f, g is processed on an EOS M290 metal laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) system in argon shielding gas using a 400W yb-fiber laser with a spot size of 100 mm. Grade 5 Ti powder is obtained from EOS with chemical composition in accordance with ASTM F1472 and F2924.

Samples are prepared for image acquisition using SiC paper, 1 mm alumina powder, and 0.02 mm colloidal silica on a VibroMetTM 2 for ~ 17 hrs. EBSD maps are obtained with a Thermo Scientific Scios scanning electron microscope equipped with an Oxford NordlysMax3 detector. Oxford Aztec data acquisition software is used to get the diffraction patterns. The EBSD step is acquired using a step of 100 nm and an acceleration voltage of 25 kV.

Steps for generating SEVMs using DREAM.3D, SliceGAN, and an integrated SliceGAN-DREAM.3D platform

The generation of 3D SEVMs from orthogonal 2D EBSD maps in Fig. 1b, c accounts for physically relevant microstructural feature statistics, including grain size and grain aspect ratio distributions, texture, grain misorientation angle distributions, as well as the area fraction of the CG domain. Three different methodologies are implemented and tested for this purpose.

DREAM.3D

The major steps in the DREAM.3D generation include (i) separating the UFG and CG domains, (ii) identifying prior particles containing the CG domain in the EBSD map using a 2D watershed algorithm, (iii) packing prior particles in the SEVM domain from consideration of morphological characteristics, (iv) evaluating morphological and crystallographic characteristics of the CGs, and (v) packing CGs within the prior particles delineated in step (iii).

SliceGAN: A generative adversarial network (GAN) model

The GAN used in this work, along with its architecture and parameters, is based on a model introduced in ref. 46. The binary microstructure in Fig. 9c, d is used as input for characterizing the UFG and CG domains in the SEVM, while the microstructures shown in Figs. 6b, 5 use the grain orientation in the form of quaternions as inputs. The training runs of the binary CSF AA7050 and additively manufactured Ti64 microstructures were performed on 1 GPU Nvidia A100 with 40 GB of memory for a period of 2 h. Once the model is trained, a new microstructure with different characteristics can be generated in 15 seconds. An example of a different microstructure is shown in Supplementary Fig. 5.

a–d Result of operations in step 1 (Separating the UFG and CG domains) towards creating SEVMs containing UFGs (blue) and CGs (red) using: a GAKAM threshold, b both GAKAM and grains size threshold, and a dilation/erosion operation to avoid the UFGs inside the CGs for the c XY plane and d YZ plane. e, f 3D binary microstructure obtained in step 2 (Generating binary 3D SEVMs) directly from e SliceGAN and f after using the improved mask with a volume fraction threshold. g Comparing area fractions (\(\frac{{A}_{{\rm{UFG}}}}{{A}_{{\rm{Total}}}}\)) of the EBSD data and orthogonal slices of the 3D mask by just using SliceGAN, and from SliceGAN with improved masking. [For all histograms, n = 300].

The GAN implements two tasks, viz., a generator for learning to generate plausible data, and a discriminator for learning to distinguish the generator’s fake data from real data. As illustrated in Fig. 8, the discriminator is composed of five convolution layers, while the generator is composed of five transposed convolution layers and one softmax layer. The original SliceGAN code is modified to handle more than 1 input in the form of text or hd5f files. The hd5f files are used to bridge SliceGAN and DREAM.3D. The generated 3D microstructure is sectioned along three orthogonal planes and compared to the corresponding experimental data. Hence, every plane has its own loss function. The Wasserstein loss function70 is used in this work. In the Wasserstein GANs (WGANs) with gradient penalty, the Generator \({\mathcal{G}}\) and Discriminator \({\mathcal{D}}\) play a zero-sum game. The WGAN objective function is defined as:

where \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{r}\) and \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{f}\) are the real and fake data distributions, respectively, and D() is the discriminator function computed on the real data subset r, and the fake slice of the generated 3D microstructure fs. \({\mathbb{E}}[D({\boldsymbol{X}})]\) is the expectation of D(X) given a random variable X. In SliceGAN46, an additional gradient penalty term is proposed in ref. 71, is considered for the calculation of the discriminator loss function as:

where λ is the penalty coefficient, k = εfs + (1 − ε)r with ε = [0, 1] being randomly sampled, and ∇k is the Laplacian with gradients represented in the coordinates k. In addition, the generator loss function is defined in a more simplified way as:

Integrated SliceGAN-DREAM.3D Platform

The generation process entails three major steps, as shown in Fig. 8.

Step 1: Separating the UFG and CG domains: The first step in constructing SEVMs of cold spray-formed microstructures entails the separation of the two categories of grains, viz., the recrystallized UFGs and the prior particle CGs. The two orthogonal EBSD maps in Fig. 1b, c are considered for providing the input microstructural data source. The UFGs and CGs have different dislocation densities, and hence the KAM data can be used to distinguish between the two groups of grains72,73. Figure 9a–d shows the results of operations in step 1 to generate a binary microstructure from a given EBSD map.

An initial separation of the UFG and CG is obtained by choosing a GAKAM threshold of 0.056∘. Figure 9a shows the UFG (in blue) and CG (in red) domains created by using only the GAKAM threshold. As recrystallization leads to much smaller grains, a grain size threshold criterion, in addition to the GAKAM threshold, is enacted to refine the result in Fig. 9a. Figure 9b shows the resulting UFG and CG domains created using both the GAKAM and a cluster size criteria obtained via a Gaussian blur filter to remove small, isolated clusters of CGs identified by GAKAM. Figure 9c, and d show the final UFG and CG domains of the two orientation maps shown in Fig. 1b, and c, respectively, after an additional erode/dilate operation is performed. The two domains have different geometrical features in the XY plane in Fig. 9c and the YZ plane in Fig. 9d. In the XY plane, the CGs preserve the initial circular geometry of the particles, while in the YZ plane, the CGs have elongated and imbricated geometries resulting from the deformation of particles during the impact.

Step 2: Generating binary 3D SEVMs from 2D data using a generative adversarial network (GAN): The second step in creating the SEVM is the generation of a 3D binary microstructure from the orthogonal 2D binary microstructures shown in Fig. 9c, d. For this operation, the generative adversarial network code SliceGAN46 is used to create 3D data from orthogonal 2D images. To accomplish this, SliceGAN combines a 3D generator and 3 separate 2D discriminators, one for each orthogonal direction. After generating a 3D microstructure, a slicing step is activated in the 3 mutually orthogonal directions to compare the statistics from the 3D volume to those from the 2D training images, as shown in Fig. 8. SliceGAN has two major advantages, viz. (i) the training data is reduced to a single 2D representative image for isotropic microstructures, and (ii) the method can be extended to anisotropic microstructures if three different image scans are provided as input. This is important for applications in which limited data is available to create virtual instantiations of the microstructure. For the examples shown in this work, the sampling window has a size of 64 pixels × 64 pixels. This size can be changed but this value provides enough sub-images from the masks created in step 1. They also contain the principal features of the microstructure.

From visual identification, it is assumed that the YZ and XZ planes of the EBSD maps have similar statistics and can be represented by a single data set. Consequently, only two EBSD-based images are used to generate the 3D binary microstructure, viz. (i) the XY plane in Fig. 9c and (ii) the YZ plane in Fig. 9d with similar assumed statistics for the XZ plane. Figure 9e shows the 3D binary microstructure generated by SliceGAN, where the CG domain is colored in red, and the UFG domain is colored in blue. While the results from SliceGAN represent the two phases well, the grain morphology is altered due to the truncation of grain data beyond the UFG-CG domain boundary, when applied directly as a mask in the DREAM.3D software. Consequently, an improvement of the mask is developed to better retain the morphological statistics of the grains after packing with better conformity to the area fractions of the EBSD data. First, the entire cubic volume is packed with grains, having equivalent statistical distributions of morphological features, using DREAM.3D. To accomplish this, the volume fraction vfrac of each grain intersected by the 3D mask from SilceGAN is defined using a relation:

where vG is the volume of the grain and vmask the volume of the mask. If vfrac falls below a given threshold, i.e., vfrac < vfth, the entire grain is omitted from the mask. Otherwise, the grain is retained. Figure 9f shows the improved mask using a volume fraction threshold of vfth = 0.1. Using these steps, the important characteristics of the 3D microstructure obtained by SliceGAN are preserved. Furthermore, the area fractions \(\frac{{A}_{{\rm{UFG}}}}{{A}_{{\rm{Total}}}}\) are closer to the EBSD, as shown in the statistics of Fig. 9g.

The 3D binary microstructure generated using SliceGAN is visually similar to the geometry of the 2D binary microstructure generated in step 1, as shown in Fig. 9c, d. Figure 9g shows the area fraction of the CGs (red domain). For the area fraction distributions, 2D slices are sampled from the synthetic 3D microstructure in each orthogonal direction, and compared with data from corresponding EBSD windows of the same dimensions as the 3D slices. It is evident that the masking technique improves the area fraction of the domains in the three orthogonal directions. In the Supplementary Material: Additional details on generating SEVMs for CSF Al7050 Supplementary Fig. 8 shows details from particles inside the SEVM shown in Fig. 3a, and Supplementary Fig. 4 depicts slices from orthogonal sections of the improved binary microstructure in Fig. 9f at different locations. The images confirm that the principal characteristics of the experimental data are reproduced, and the topological complexity of both the UFG and CG domains is well captured.

Step 3: Generating the 3D SEVM by grain packing using DREAM.3D: The third step entails coarse grain packing in the prior particles such that the morphological and crystallographic characteristics of the EBSD data are conserved. DREAM.3D14 is employed to match the EBSD morphological distributions, e.g., grain size and aspect ratio distributions of CGs in the prior particles. Figure 3a shows the reconstructed microstructure with 24924 coarse grains. Crystallographic orientations are assigned to the grains of the virtual microstructure by sampling from the experimental EBSD data, thus conforming to the microstructural texture as shown in Fig. 3b. The misorientation angle distribution is also improved by using a crystallographic orientation swapping algorithm, in which the orientations of two or more grains are swapped, and the difference in the misorientation angle distributions between the newly instantiated SEVM and EBSD maps are compared using Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test to analyze the goodness-of-fit with respect to the experimental data74. The KS test quantifies the maximum difference in the cumulative distribution functions (CDF) of the virtual and experimental data sets. If the KS value of the new SEVM misorientation angle distribution is lower than the KS value before the swapping, the new orientations are accepted. This process is repeated up to a certain tolerance where the KS value converges.

It is evident that the final SEVM characteristics are in agreement with the morphological and crystallographic data in the EBSD maps. The pole figures of the SEVM, shown in Fig. 3b, are close to the experimental pole figures. The misorientation angle distribution, a crucial determinant of fatigue crack evolution, is also improved with the swapping algorithm as shown in Fig. 3c.

Concurrent micromechanical CG and UFG models and calibration procedure

The concurrent multiscale model of the SEVMs consists of two phases, viz., the polycrystalline ensembles of CGs and UFGs that are represented by different types of constitutive models. The CGs are modeled using a crystal plasticity (CP) constitutive model given in ref. 8, while the UFGs are modeled using an upscaled constitutive model (UCM)61,62 that is derived by upscaling the behavior of the polycrystalline SERVEs modeled by CP models. The essential relations for both these models are summarized in this section, but more details are provided in Supplementary Materials: Micromechanical crystal plasticity and upscaled constitutive models.

Crystal plasticity model

A thermally activated flow rule is used to represent the slip rate \({\dot{\gamma }}^{\alpha }\) in terms of the driving stress σα as \({\dot{\gamma }}^{\alpha }={\dot{\gamma }}_{ref}^{\alpha }exp\left(\frac{{Q}_{slip}^{\alpha }}{{K}_{B}\theta }{[1-{\left(\frac{| {\sigma }^{\alpha }| -{s}_{a}^{\alpha }}{{s}_{\star }^{\alpha }}\right)}^{P}]}^{Q}\right)\) where \({\dot{\gamma }}_{ref}^{\alpha }\) is the reference slip rate, \({Q}_{slip}^{\alpha }\) is the thermal activation energy, KB is the Boltzmann constant, θ is the temperature, and P and Q are materials constants. The athermal and thermal slip resistances, \({s}_{a}^{\alpha }\) and \({s}_{\star }^{\alpha }\), consider both statistically stored dislocations (SSDs) and geometrically necessary dislocations (GNDs) given as:

where \({s}_{a,0}^{\alpha }\) and \({s}_{\star,0}^{\alpha }\) are the initial resistances, and the evolution of the thermal and athermal SSDs are defined using a phenomenological hardening equation:

where t0 is the direction of the dislocation line, hαβ is the hardening of slip system α due to the activity on slip system β.

Upscaled constitutive model (UCM)

The UCM is based on a constitutive model that is thermodynamically consistent with the homogenized behavior of the underlying SERVE response in crystal plasticity-based micromechanical simulations. Detailed concepts of the development of UCMs are given in refs. 61,62. The upscaled anisotropic yield function (Y) and the flow stress (Y0) in the plastic deformation are respectively expressed as:

and

where λ1, λ2, and λ3 are the eigenvalues of a transformed second Piola-Kirchhoff stress tensor given as \({\mathbf{\Sigma }}={\mathbb{L}}:({\boldsymbol{S}}-{\boldsymbol{\chi }})\), S is the second Piola-Kirchhoff stress, χ is the back-stress, and εp is the effective plastic strain. k and a are, respectively, the tension-compression asymmetry parameter and the yield surface exponent that controls its shape, Yref is the initial flow, Ysat and β are microstructure and loading direction-dependent parameters, and α corresponds to the hardening slope.

Calibration process

The crystal plasticity (CP) and upscaled constitutive model (UCM) parameters are calibrated simultaneously for the bimodal material microstructure by using an open-source hyper-parameter optimization framework and code75 in conjunction with FE simulations of a concurrent model, in which the CG domain of crystal plasticity-based modeling is interfaced in a self-consistent manner with UFG domain of UCM-based modeling. The set of parameters to be calibrated includes the parameter set (\({{\mathcal{S}}}_{{\mathcal{C}}}=\{{s}_{a,0}^{\alpha },{s}_{\star,0}^{\alpha },{h}_{a}^{\alpha \beta },{h}_{\star }^{\alpha \beta }\}\)) for the CP model and the parameter set (\({{\mathcal{S}}}_{{\mathcal{U}}}=\{m,{Y}_{sat},\alpha,\beta \}\)) for the UCM. The calibration procedure is comprised of two loops, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 9, viz. (i) an outer loop that compares the mechanical response of the complete bimodal SEVM to the experimental data and (ii) an inner loop where the stress-strain response by the UCM matches the stress-strain response by the crystal plasticity model for the UFGs. For this calibration, an objective function \({\mathcal{L}}(\sigma )\) is set up to minimize the area under the two stress-strain plots, as well as their slope-strain plots, given as:

where σexp and σsim are, respectively, the experimental and simulated stresses, ε is the ultimate strain, εy is the yield strain, and the weighting functions are \({W}_{1}=\frac{2}{3}\), and \({W}_{2}=\frac{1}{3}\).

The steps in the calibration of the CP and UCM model parameters include:

-

(i)

Assume a CP parameter set \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{{\mathcal{C}}}\);

-

(ii)

Perform simulation of the UFGs using the parameters \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{{\mathcal{C}}}\) in the CP model;

-

(iii)

Define a set of parameters \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{{\mathcal{U}}}\);

-

(iv)

Simulate the UFGs using the parameter set \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{{\mathcal{U}}}\) in the UCM;

-

(v)

Evaluate the objective function \({\mathcal{L}}{(\sigma )}_{UFG}\) between the stress-strain response obtained using CP and UCM simulations in steps (ii) and (iv),

-

(vi)

If \({\mathcal{L}}{(\sigma )}_{UFG}\ge {\mathcal{L}}{(\sigma )}_{threshold}\) go back to step (iii), otherwise,

-

(vii)

Perform a simulation of the bimodal microstructure with explicit CGs and upscaled UFGs using the sets \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{{\mathcal{C}}}\) and \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{{\mathcal{U}}}\),

-

(viii)

Evaluate the objective function \({\mathcal{L}}{(\sigma )}_{Exp}\) between the stress-strain response of the bimodal microstructure and the experimental data;

-

(ix)

If \({\mathcal{L}}{(\sigma )}_{Exp} < {\mathcal{L}}{(\sigma )}_{threshold}\) the calibration process is completed, otherwise go back to step (i).

It is important to note that the calibrated parameters depend on the morphological or crystallographic characteristics of the microstructure, as well as on the material properties. Hence, the calibration process needs to be repeated if any of these characteristics are different. For the bimodal CSF AA7050 alloy in this study, the number of outer loops needed for calibration is 38, with a maximum of 100 inner loops per outer loop. The UCM model simulations take approximately one minute on a single processor, while simulations with the CP model take approximately 2 h on 24 processors of a Rockfish cluster. It consists of Intel Xeon Gold Cascade Lake 6248R processors with 4GBs of 2933MHz DDR4 memory per processor.

Data visualization

Data visualization was performed using Paraview76, MTEX59, Matplotlib77, and Inkscape.

Data availability

All datasets have been shared within the codes on the general repository Zenodo and published at https://zenodo.org/records/13621616. The repository name and DOI are given below. Dataset: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13621615(2024). Repository Name: SliceGAN, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13372514 (2024). This has been cited in78,79. The input data used to generate the cold-sprayed and Ti64 microstructures are in the input folder of SliceGAN79. The relevant raw data for each figure and the files to visualize the microstructures are provided in Zenodo78. Source data are provided in this paper.

Code availability

All datasets have been shared within the codes on the general repository Zenodo. The repository name and DOI are given below. 1. Repository Name: SliceGAN, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13372514(2024) 2. Repository Name: csf-al7050-processing, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13372512 (2024) They have been cited in ref. 79 and ref. 80 respectively.

References

Groeber, M., Haley, B., Uchic, M., Dimiduk, D. & Ghosh, S. 3D reconstruction and characterization of polycrystalline microstructures using a FIB-SEM system. Mater. Charact. 57, 259–273 (2006).

Uchic, M. D. et al. Augmenting the 3D characterization capability of the dual beam FIB SEM. Micros. Microanal. 10, 1136–1137 (2004).

Turner, T. J. et al. Crystal plasticity model validation using combined high-energy diffraction microscopy data for a Ti-7Al specimen. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 48, 627–647 (2017).

Bhandari, Y. et al. 3D polycrystalline microstructure reconstruction from FIB generated serial sections for FE analysis. Comput. Mater. Sci. 41, 222–235 (2007).

Bagri, A. et al. Microstructure and property-based statistically equivalent representative volume elements for polycrystalline Ni-based superalloys containing annealing twins. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 49, 5727–5744 (2018).

Ghosh, S. & Groeber, M. A. Handbook of Materials Modeling: Methods: Theory and Modeling, 1, 1631–1656 (Springer Intl., 2020).

Pinz, M. et al. Microstructure and property based statistically equivalent RVEs for intragranular γ- γ’microstructures of Ni-based superalloys. Acta Mater. 157, 245–258 (2018).

Tu, X., Shahba, A., Shen, J. & Ghosh, S. Microstructure and property based statistically equivalent RVEs for polycrystalline-polyphase aluminum alloys. Int. J. Plast. 115, 268–292 (2019).

Groeber, M., Ghosh, S., Uchic, M. D. & Dimiduk, D. M. A framework for automated analysis and simulation of 3d polycrystalline microstructures.: Part 1: Statistical characterization. Acta Mater. 56, 1257–1273 (2008).

Groeber, M., Ghosh, S., Uchic, M. D. & Dimiduk, D. M. A framework for automated analysis and simulation of 3d polycrystalline microstructures. Part 2: Synthetic structure generation. Acta Mater. 56, 1274–1287 (2008).

Swaminathan, S., Ghosh, S. & Pagano, N. Statistically equivalent representative volume elements for unidirectional composite microstructures: Part I-without damage. J. Compos. Mater. 40, 583–604 (2006).

Ghosh, S., Dimiduk, D.M. & Furrer, D. Statistically equivalent representative volume elements (SERVE) for material behavior analysis and multiscale modeling. Int. Mater. Rev. 68, 1158–1191 (2023).

Swaminathan, S. & Ghosh, S. Statistically equivalent representative volume elements for unidirectional composite microstructures: Part II-with interfacial debonding. J. Compos. Mater. 40, 605–621 (2006).

Groeber, M. A. & Jackson, M. A. DREAM.3D: a digital representation environment for the analysis of microstructure in 3d. Integ. Mater. Manuf. Innov. 3, 56–72 (2014).

Quey, R. & Kasemer, M. The NEPER/FEPX project: Free / open-source polycrystal generation, deformation simulation, and post-processing. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1249, 012021 (2022).

Hart, K. A. & Rimoli, J. J. Microstructpy: A statistical microstructure mesh generator in python. SoftwareX 12, 100595 (2020).

Prasad, M. R., Vajragupta, N. & Hartmaier, A. Kanapy: A python package for generating complex synthetic polycrystalline microstructures. J. Open Source Softw. 4, 1732 (2019).

Kench, S., Squires, I., Dahari, A. & Cooper, S. J. Microlib: A library of 3D microstructures generated from 2D micrographs using SLICEGAN. Sci. Data 9, 1–8 (2022).

Imai, H., Iri, M. & Murota, K. Voronoi diagram in the Laguerre geometry and its applications. SIAM J. Comput. 14, 93–105 (1985).

Shamos, M. I. & Hoey, D. Closest-point problems. In 16th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (sfcs 1975), 151–162 (IEEE, 1975).

Visscher, W. M. & Bolsterli, M. Random packing of equal and unequal spheres in two and three dimensions. Nature 239, 504–507 (1972).

Bagi, K. A quasi-static numerical model for micro-level analysis of granular assemblies. Mech. Mater. 16, 101–110 (1993).

Jodrey, W. & Tory, E. Computer simulation of isotropic, homogeneous, dense random packing of equal spheres. Powder Tech. 30, 111–118 (1981).

Hitti, K. & Bernacki, M. Optimized dropping and rolling (ODR) method for packing of poly-disperse spheres. Appl. Math. Model. 37, 5715–5722 (2013).

Acar, P. & Sundararaghavan, V. A Markov random field approach for modeling spatio-temporal evolution of microstructures. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 24, 075005 (2016).

Boguń, K., Sitko, M., Mojżeszko, M. & Madej, Ł. Cellular automata-based computational library for development of digital material representation models of heterogeneous microstructures. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 21, 1–15 (2021).

Guo, E.-Y., Chawla, N., Jing, T., Torquato, S. & Jiao, Y. Accurate modeling and reconstruction of three-dimensional percolating filamentary microstructures from two-dimensional micrographs via dilation-erosion method. Mater. Charact. 89, 33–42 (2014).

Jiao, Y., Stillinger, F. & Torquato, S. Modeling heterogeneous materials via two-point correlation functions: Basic principles. Phys. Rev. E 76, 031110 (2007).

Tewari, A., Gokhale, A., Spowart, J. & Miracle, D. Quantitative characterization of spatial clustering in three-dimensional microstructures using two-point correlation functions. Acta Mater. 52, 307–319 (2004).

Hasanabadi, A., Baniassadi, M., Abrinia, K., Safdari, M. & Garmestani, H. Optimization of solid oxide fuel cell cathodes using two-point correlation functions. Comput. Mater. Sci. 123, 268–276 (2016).

Chen, S., Kirubanandham, A., Chawla, N. & Jiao, Y. Stochastic multi-scale reconstruction of 3D microstructure consisting of polycrystalline grains and second-phase particles from 2D micrographs. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 47, 1440–1450 (2016).

Flipon, B., Keller, C., Quey, R. & Barbe, F. A full-field crystal-plasticity analysis of bimodal polycrystals. Int. J. Solids Struct. 184, 178–192 (2020).

Wu, H., Niu, G., Cao, J. & Yang, M. Annealing of strain-induced martensite to obtain micro/nanometre grains in austenitic stainless. Mater. Sci. Technol. 33, 480–486 (2017).

Shekhar, S., Cai, J., Wang, J. & Shankar, M. Multimodal ultrafine grain size distributions from severe plastic deformation at high strain rates. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 527, 187–191 (2009).

Dirras, G., Gubicza, J., Ramtani, S., Bui, Q. & Szilágyi, T. Microstructure and mechanical characteristics of bulk polycrystalline Ni consolidated from blends of powders with different particle size. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 527, 1206–1214 (2010).

Zou, Y. et al. Dynamic recrystallization in the particle/particle interfacial region of cold-sprayed nickel coating: Electron backscatter diffraction characterization. Scripta Mater. 61, 899–902 (2009).

Pinz, M. et al. Efficient computational framework for image-based micromechanical analysis of additively manufactured Ti-6Al-4V alloy. Addit. Manuf. 60, 103269 (2022).

Zhang, Z., Vajpai, S. K., Orlov, D. & Ameyama, K. Improvement of mechanical properties in sus304l steel through the control of bimodal microstructure characteristics. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 598, 106–113 (2014).

Lee, J.-W. et al. Correlations between two EBSD-based metrics Kernel Average Misorientation and image quality on indicating dislocations of near-failure low alloy steels induced by tensile and cyclic deformations. Mater. Today Commun. 27, 102445 (2021).

Chen, Y.-W. et al. Phase quantification in low carbon Nb-Mo bearing steel by electron backscatter diffraction technique coupled with kernel average misorientation. Mater. Charact. 139, 49–58 (2018).

Zhu, L. & Lu, J. Modelling the plastic deformation of nanostructured metals with bimodal grain size distribution. Int. J. Plast. 30–31, 166–184 (2012).

Magee, A. C. & Ladani, L. Representation of a microstructure with bimodal grain size distribution through crystal plasticity and cohesive interface modeling. Mech. Mater. 82, 1–12 (2015).

Liu, S. & Shin, Y. C. Additive manufacturing of Ti6Al4V alloy: A review. Mater. Des. 164, 107552 (2019).

Krishnamoorthi, S., Bandyopadhyay, R. & Sangid, M. A microstructure-based fatigue model for additively manufactured Ti-6Al-4V, including the role of prior β boundaries. Int. J. Plast. 163, 103569 (2023).

Fokina, D., Muravleva, E., Ovchinnikov, G. & Oseledets, I. Microstructure synthesis using style-based generative adversarial networks. Phys. Rev. E 101, 043308 (2020).

Kench, S. & Cooper, S. J. Generating three-dimensional structures from a two-dimensional slice with generative adversarial network-based dimensionality expansion. Nat. Mach. Intell. 3, 299–305 (2021).

Jung, J., Yoon, J. I., Park, H. K., Jo, H. & Kim, H. S. Microstructure design using machine learning generated low dimensional and continuous design space. Materialia 11, 100690 (2020).

Hsu, T. et al. Microstructure generation via generative adversarial network for heterogeneous, topologically complex 3D materials. JOM 73, 90–102 (2021).

Lee, J.-W., Goo, N. H., Park, W. B., Pyo, M. & Sohn, K.-S. Virtual microstructure design for steels using generative adversarial networks. Eng. Rep. 3, e12274 (2021).

Zhang, T., Ji, X. & Lu, F. 3d reconstruction of porous media by combining scaling transformation and multi-scale discrimination using generative adversarial networks. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 209, 109815 (2022).

Goodfellow, I. J. et al. Generative adversarial networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Proc. Syst. 27, (2014).

Goodfellow, I. et al. Generative adversarial networks. Commun. ACM 63, 139–144 (2020).

Assadi, H., Gärtner, F., Stoltenhoff, T. & Kreye, H. Bonding mechanism in cold gas spraying. Acta Mater. 51, 4379–4394 (2003).

Bae, G., Xiong, Y., Kumar, S., Kang, K. & Lee, C. General aspects of interface bonding in kinetic sprayed coatings. Acta Mater. 56, 4858–4868 (2008).

Ahmed, R. et al. On the role of deformation and cracking in the cold spray processing of refractory ta powders onto ta or 4340 steel substrates: Effects of topical oxide layers and spray velocity. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 53, 3381–3391 (2022).

Weiller, S. & Delloro, F. A numerical study of pore formation mechanisms in aluminium cold spray coatings. Addit. Manuf. 60, 103193 (2022).

Williamson, C., Webb, A., Brewer, L., Allison, P. & Jordon, J. Effect of powder heat treatment on fatigue mechanisms of freestanding AA7075 cold spray deposits. Int. J. Fatigue 167(A), 107256 (2022).

Gillibert, L., Peyrega, C., Jeulin, D., Guipont, V. & Jeandin, M. 3D multiscale segmentation and morphological analysis of X-ray microtomography from cold-sprayed coatings. J. Microsc. 248, 187–199 (2012).

Bachmann, F., Hielscher, R. & Schaeben, H. Texture analysis with Mtex - free and open source software toolbox. Solid State Phenom. 160, 63–68 (2010).

Calcagnotto, M., Ponge, D., Demir, E. & Raabe, D. Orientation gradients and geometrically necessary dislocations in ultrafine grained dual-phase steels studied by 2D and 3D EBSD. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 527, 2738–2746 (2010).

Kotha, S., Ozturk, D. & Ghosh, S. Parametrically homogenized constitutive models (PHCMs) from micromechanical crystal plasticity FE simulations, Part I: Sensitivity analysis and parameter identification for titanium alloys. Int. J. Plast. 120, 296–319 (2019).

Kotha, S., Ozturk, D. & Ghosh, S. Parametrically homogenized constitutive models (PHCMs) from micromechanical crystal plasticity FE simulations, Part II: Thermo-elasto-plastic model with experimental validation for Titanium alloys. Int. J. Plast. 120, 296–319 (2019).

Pinz, M., Weber, G., Stinville, J. C., Pollock, T. & Ghosh, S. Data-driven Bayesian model-based prediction of fatigue crack nucleation in Ni-based superalloys. NPJ Comput. Mater. 8, 39 (2022).

Peng, D., Jones, R., Matthews, N. & Tang, C. On the role of the interface on the damage tolerance and durability of cold spray repairs to AA7075-T7351 aluminium alloy wing skins. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 3, 100044 (2021).

Pegues, J. W. et al. Fatigue of additive manufactured Ti-6Al-4V, Part I: The effects of powder feedstock, manufacturing, and post-process conditions on the resulting microstructure and defects. Int. J. Fatigue 132, 107256 (2020).

Kanopoulos, N., Vasanthavada, N. & Baker, R. L. Design of an image edge detection filter using the Sobel operator. IEEE J. Solid State Circuits 23, 358–367 (1988).

Mescheder, L., Geiger, A. & Nowozin, S. Which training methods for GANs do actually converge? Int. Conf. Mach. Learn. 80, 3481–3490 (2018).

Karras, T., Laine, S. & Aila, T. A style-based generator architecture for generative adversarial networks. In Proc. IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 4401–4410 (2019).

Chung, H. & Ye, J. C. Reusability report: Feature disentanglement in generating a three-dimensional structure from a two-dimensional slice with SliceGAN. Nat. Mach. Intell. 3, 861–863 (2021).

Arjovsky, M., Chintala, S. & Bottou, L. Wasserstein generative adversarial networks. Int. Conf. Mach. Learn. 70, 214–223 (2017).

Gulrajani, I., Ahmed, F., Arjovsky, M., Dumoulin, V. & Courville, A. C. Improved training of Wasserstein GANs. Adv. Neural Inf. Proc. Syst. 30, (2017).

Nicolay, A. et al. Discrimination of dynamically and post-dynamically recrystallized grains based on EBSD data: application to Inconel 718. J. Microsc. 273, 135–147 (2019).

Zouari, M., Logé, R. E. & Bozzolo, N. In situ characterization of Inconel 718 post-dynamic recrystallization within a scanning electron microscope. Metals 7, 476 (2017).

Massey Jr, F. J. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for goodness of fit. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 46, 68–78 (1951).

Optuna: Optimize Your Optimization: An open-source hyperparameter optimization framework to automate hyperparameter search. https://optuna.org/ (2024).

Ahrens, J., Geveci, B. & Law, C. The Visualization Handbook. (2005).

Hunter, J. D. Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Comp. Sci. Eng. 9, 90–95 (2007).

Murgas, B., Stickel, J. & Ghosh, S. Dataset for publication: Statistically Equivalent Virtual Microstructures for Modeling of Complex Polycrystalline Alloys Using a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN)-Enabled Computational Platform [Data set]. Zenodo, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13621615 (2024).

Murgas, B., Stickel, J. & Ghosh, S. Statistically Equivalent Virtual Microstructures for Modeling of Complex Polycrystalline Alloys Using a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN)-Enabled Computational Platform. Repository Name: sliceGAN, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13372514 (2024).

Murgas, B., Stickel, J. & Ghosh, S. Statistically Equivalent Virtual Microstructures for Modeling of Complex Polycrystalline Alloys Using a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN)-Enabled Computational Platform. Repository Name: csf-al7050-processing, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13372512 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work has been sponsored by a grant from the Office of Naval Research Aero Structures & Materials program, USA, through Grant Number: N00014-20-1-4004 (S.G.). The program managers of this grant are Dr. William Nickerson and Dr. Anisur Rahman. The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of this work. Computational support for this work has been provided by the Advanced Research Computing at Hopkins (ARCH) core facility supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) grant number OAC 1920103. Computational support for this work is also provided by an AFOSR DURIP grant FA9550-21-1-0303 (S.G.). The authors also thank Steven Storck of JHU/APL for providing the images and data on the additively manufactured Ti64 alloy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.G. has conceived the overall concept. He has also revised and written parts of the manuscript. B.M. has proposed the methodology. Both B.M. and J.S. have developed the models and codes, produced the results, and written the first draft of the manuscript. L.B. did the experiments and provided the experimental data on the CSF AA7050 alloy.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Samuel Cooper and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions