Abstract

The rapid recombination of photoinduced charge carriers in semiconductors fundamentally limits their application in photocatalysis. Herein, we report that a superlattice interface and S-scheme heterojunction based on Mn0.5Cd0.5S nanorods can significantly promote ultrafast charge separation and transfer. Specifically, the axially distributed zinc blende/wurtzite superlattice interfaces in Mn0.5Cd0.5S nanorods can redistribute photoinduced charge carriers more effectively when boosted by homogeneous internal electric fields and promotes bulk separation. Accordingly, S-scheme heterojunctions between the Mn0.5Cd0.5S nanorods and MnWO4 nanoparticles can further accelerate the surface separation of charge carriers via a heterogeneous internal electric field. Subsequent capture of the photoelectrons by adsorbed H2O is as fast as several picoseconds which results in a photocatalytic H2 evolution rate of 54.4 mmol·g−1·h−1 without any cocatalyst under simulated solar irradiation. The yields are increased by a factor of ~5 times relative to control samples and an apparent quantum efficiency of 63.1% at 420 nm is measured. This work provides a protocol for designing synergistic interface structure for efficient photocatalysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The limited separation efficiency of photoinduced charge carriers, in both temporal and spatial dimensions, without any noble-metal or noble-metal-free cocatalysts, remains a key challenge in the area of semiconductor-based photocatalysis1,2,3,4,5,6. This persistent obstacle significantly hampers the advancement of solar-to-chemical energy conversion efficiency in photocatalytic processes, including photocatalytic water splitting for H2 evolution (PHE). Despite the development of various high-performance photocatalysts7,8,9,10, such as binary sulfides11,12,13, sulfide solid solutions14,15,16,17,18, covalent organic frameworks (COFs)19,20,21, metal organic frameworks (MOFs)22,23 and a range of donor-acceptor conjugated polymers24,25,26,27, their photocatalytic activity remains suboptimal. This shortfall is primarily attributed to the sluggish and localized separation of photoinduced charge carriers. Therefore, achieving ultrafast and universal spatial separation of photoinduced charge carriers within semiconductors is highly desirable and holds great potential for boosting photocatalytic redox reactions.

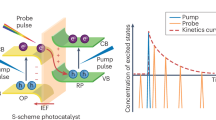

To realize this goal, effective bulk separation of photogenerated charge carriers within semiconductor photocatalysts is a crucial prerequisite28,29. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that step-scheme (S-scheme) heterojunctions can promote spatial charge separation at the surface level30,31. However, if charge separation in the bulk material is inadequate, solely relying on S-scheme heterojunctions for surface charge separation will not achieve the desired ultrafast and universal spatial charge separation32, as displayed in Fig. 1. Superlattice structures, consisting of periodically or quasi-periodically alternating homogeneous or heterogeneous lattices along the growth axis of the material33,34, offer a promising solution. When these periodic alternating homointerfaces or heterointerfaces are continuously distributed throughout the bulk of a photocatalyst with a superlattice structure, they are likely to induce effective separation and ultrafast transfer of photoexcited charge carriers within the bulk35,36,37. However, bulk charge separation alone is insufficient if surface recombination persists38,39, as also shown in Fig. 1. Hence, it is essential to further redistribute the charge carriers to the surfaces of different semiconductor photocatalysts. Constructing S-scheme heterojunctions by loading nanoparticles only a few nanometers in size is a viable strategy that also enhances the photocatalytic redox capability of superlattice structure and loaded nanoparticles30,31. Ultimately, as depicted in Fig. 1, ultrafast and universal spatial charge separation can be achieved through the synergistic interaction between superlattice interfaces and S-scheme heterojunctions, significantly improving the kinetics of photocatalytic redox reactions.

According to the consecution of universal spatial charge separation, only synergy of superlattice interface and S-scheme heterojunction can achieve the ultrafast and universal spatial separation and transfer of charge carriers. The red and green marks represent unsatisfactory and satisfactory separation efficiency, respectively.

In this study, we successfully synthesized zinc blende/wurtzite (ZB/WZ) phase-transition-induced standard one-dimensional (1D) axial superlattice Mn0.5Cd0.5S nanorods (SL-MCS NRs) via an in situ precipitation-solvothermal method. Furthermore, fine MnWO4 nanoparticles (NPs) were in situ deposited onto SL-MCS NRs to form S-scheme heterojunctions. The resulting photocatalyst exhibits a distinctive structure: superlattice interfaces between the ZB and WZ phases are distributed periodically and alternately along the axial direction of SL-MCS NRs, while abundant MnWO4 NPs are anchored on the surface to fabricate extensive S-scheme heterointerfaces. The synergistic effect between the superlattice interfaces and S-scheme heterojunctions in this nanorod composite (SL-MCS/MW NRs) significantly accelerates the separation of photoinduced charge carriers throughout the entire structure. Consequently, the optimal synergy enables the SL-MCS/MW NRs to achieve an average PHE rate of 54.4 mmol·g−1·h−1, accompanied by vigorous bubble formation, without noble-metal or noble-metal-free cocatalysts under simulated solar irradiation. The corresponding apparent quantum efficiency (AQE) reaches 63.1% at 420 nm. Notably, the PHE performance of SL-MCS/MW NRs is up to 4.8 times higher than those of systems with limited charge separation and transfer. This interface synergy mechanism is further validated by theoretical calculations, in situ illumination characterizations, and ultrafast pump–probe detection techniques. This work provides valuable insights into achieving ultrafast spatial charge separation and transfer for efficient photocatalysis and other photoelectric conversion applications.

Results

Synthesis and characterization of interface structure

The synthesis process of SL-MCS/MW NRs is illustrated in Fig. 2. Initially, both OH− and anhydrous ethylenediamine (EDA) act as strong Lewis bases, co-precipitating Mn2+ and Cd2+ to create abundant nucleation sites before the solvothermal reaction. At lower solvothermal temperature, the thermodynamically stable ZB phase dominates40, leading to the in situ growth of Mn0.5Cd0.5S (ZB-MCS) crystal nuclei along the [111]ZB direction from the nucleation sites. As the temperature and pressure increase, lattice distortion centers appear in ZB-MCS NRs. These centers facilitate the phase transition from ZB to WZ, equivalent to stacking faults from the cubic AbBcCa pattern to the hexagonal AbBaAbBa pattern, caused by the glide of Shockley partial dislocation a/6<11\(\bar{2}\)> in ZB (where ‘a’ represents lattice constant)41,42. As the phase transition progresses, ZB/WZ superlattice interfaces form along the [0001]wz direction, resulting in the creation of SL-MCS NRs. The host lattice also transforms from ZB to WZ in this process (see Supplementary Note 1 for details on the formation mechanism of SL-MCS NRs). To construct S-scheme heterojunction, MnWO4 NPs are grown in situ on the as-prepared SL-MCS NRs through a hydrothermal method. It is observed that Mn2+ from the surface of SL-MCS NRs can enter the [WO6] octahedral interspaces, forming fine MnWO4 NPs without additional Mn2+. Finally, an intimate and robust SL-MCS/MnWO4 heterojunction is successfully fabricated.

The phase structures of the as-prepared catalysts were investigated using powder X-ray diffraction (XRD), as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2a, b. Supplementary Fig. 1 clearly shows the absence of any secondary phases, such as rocksalt MnS (RS-MnS), in the as-prepared SL-MCS solid solution NRs. As displayed in Supplementary Fig. 2a, the XRD pattern of SL-MCS NRs resembles those of standard WZ-CdS (JCPDS No. 41-1049), WZ-MnS (JCPDS No. 40-1289) and pristine WZ-MCS (without any modified interfaces), indicating that the host lattice of SL-MCS NRs is WZ rather than a ZB segment. All diffraction peaks of the as-prepared samples in Supplementary Fig. 2a present a shift toward higher 2θ values compared to standard WZ-CdS, which is attributed to the substitution of Cd2+ (ionic radius 0.97 Å) with Mn2+ (ionic radius 0.80 Å)16. Importantly, no diffraction peaks corresponding to ZB segments are observed in the XRD pattern of SL-MCS NRs, suggesting that the incomplete ZB/WZ phase transition results in relatively narrow spatial sizes of the ZB segments in the superlattice structure.

In addition, only Mn0.5Cd0.5S solid solution can extend and grow in situ into nanorods with a high aspect ratio, as seen in the field emission scanning electron microscope images (FESEM, Supplementary Fig. 3), which promotes the expansion of ZB/WZ coherent interfaces as quasi-periodic superlattice interfaces along the axial direction. It is noticeable in Supplementary Fig. 2b that the in situ loading of [WO6] octahedrons and the diffusion of Mn2+ allow the fine MnWO4 NPs to attach tightly to the surface of SL-MCS NRs, forming S-scheme heterojunctions. These loaded MnWO4 NPs, with an average size of a few nanometers, are too small to be distinguished from the corresponding composites (Supplementary Fig. 4). The actual Mn/Cd ratios in SL-MCS NRs, WZ-MCS and the weight percentage of W element (W wt%) in the as-prepared composites were measured using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES, Supplementary Table 1). The Mn/Cd ratios in both SL-MCS NRs and WZ-MCS are close to 1, and the W wt% values in SL-MCS/MW NRs and WZ-MCS/MW composites are nearly identical. Moreover, as the content of Na2WO4 increases under the same synthetic conditions, the W wt% value in the SL-MCS/MW-x composite also increases, consistent with their XRD patterns.

The detailed interface structure of SL-MCS/MW NRs was thoroughly examined using transmission electron microscope (TEM) and high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscope (HAADF-STEM). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 5a, b, SL-MCS/MW NRs exhibit a nanorod morphology with a high aspect ratio. Upon randomly magnifying the sample (Supplementary Fig. 5c) to achieve atomic-scale resolution of the superlattice interface structure in SL-MCS, as shown in Fig. 3a, the close-packed positions of Mn/Cd atoms display an alternating tendency between ABAB and ABC stacking mode along the [0001] direction, which aligns well with the alternating WZ and ZB segments, respectively. In addition, the corresponding integrated atomic arrangement is illustrated by the structural model below, showing that SL-MCS NRs consist of ZB with cubic AbBcCa stacking and WZ with hexagonal AbBaAbBa stacking. Furthermore, the number of atomic layers in WZ segments is significantly greater than that of the ZB, indicating that the host lattice of SL-MCS NRs is predominantly WZ, as observed in the XRD pattern (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Besides, the alternating and coherent ZB/WZ superlattice interfaces extend laterally to the surface of the nanorods and longitudinally along the [0001] direction of the entire nanorod. This arrangement facilitates the transfer of charge carriers to the surface of SL-MCS NRs and the heterointerfaces between SL-MCS NRs and MnWO4 NPs. Moreover, the d-spacing of the close-packed planes in SL-MCS NRs is measured to be 0.331 nm for both the WZ and ZB segments. This value lies between 0.323 nm (d(0002) of WZ-MnS, JCPDS No. 40-1289) and 0.336 nm (d(0002) of WZ-CdS, JCPDS No. 41-1049). Based on the atomic number contrast distribution (Supplementary Fig. 6) in Fig. 3b, the localized atomic arrangement, showing the co-existence of Mn and Cd atoms, is depicted in Fig. 3c. This evidence confirms the formation of the SL-MCS solid solution, consistent with its XRD patterns (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2a). In the regional fast Fourier transform (FFT) patterns (Fig. 3d) of Fig. 3a, two sets of diffraction spots can be identified, corresponding to ZB with a zone axis of [\(\bar{1}\)10]ZB and WZ with a zone axis of [\(\bar{2}\)110]wz. In addition, geometric phase analysis (GPA) simulation was conducted on Fig. 3a to determine the strain distribution in SL-MCS NRs43. As presented in Fig. 3e, the longitudinal and transverse normal strains (εzz and εyy) of SL-MCS NRs are slight and uniform throughout both the ZB and WZ segments due to the [0001]WZ-[111]ZB orientation attachment38. The shear strain (εzy) varies between −0.1 and 0.1, with a maximum lattice shear deformation of ~5.7°. This minimal lattice distortion highlights the satisfactory stability of ZB/WZ superlattice interfaces in SL-MCS NRs.

a Atomic-scale resolution HAADF-STEM image of SL-MCS region marked in Supplementary Fig. 5c with corresponding schematic diagrams of close-packing style and structural model, where A, B, C and a, b, c represent close-packing positions of Mn/Cd (gray sphere in structural model) and S (yellow sphere in structural model), respectively. b Magnified image of the area marked in (a). c Atom arrangement model of (b). d FFT pattern of (a). e Strain distribution of (a) simulated by GPA. f Atomic-scale resolution HAADF-STEM image of heterointerface in SL-MCS/MW NRs. g FFT pattern of (f). EDX mapping of (h) Mn, (i) Cd, (j) S, (k) W, and (l) O element, respectively.

As displayed in Supplementary Fig. 7 and Fig. 3f, an intimate and distinct heterointerface is observed between SL-MCS NRs and the anchored MnWO4 NPs. The d-spacing of (020) planes in MnWO4 NPs is measured to be 0.279 nm and 0.284 nm, slightly smaller than 0.288 nm (d(020) of MnWO4, JCPDS No.13-0434), likely due to limited Mn2+ diffusion into the [WO6] lattice interspaces (Fig. 2). The corresponding FFT patterns (Fig. 3g) clearly display additional diffraction spots of MnWO4 in SL-MCS/MW NRs. One contact facet in this heterointerface is approximately identified as (01\(\bar{1}\)1) of SL-MCS NRs and (020) of MnWO4 NPs. The energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) mapping images of all elements (Fig. 3h–l) further confirm that SL-MCS solid solution has been synthesized, with MnWO4 NPs uniformly adhering to the surfaces of the SL-MCS NRs. These findings reaffirm that the design of the synergistic interface structure has been successfully achieved, incorporating both superlattice interfaces and S-scheme heterojunctions into SL-MCS/MW NRs. Moreover, the small specific surface area, similar pore structure and hydrophilicity across all catalysts (Supplementary Figs. 8, 9 and Supplementary Table 2) contribute minimally to the observed differences in their PHE performances.

PHE performance

As shown in Fig. 4a, pristine WZ-MCS NPs without any interfacial modulation, achieve a relatively low PHE rate of 11.4 mmol·g−1·h−1 among all the catalysts. By fabricating single S-scheme heterojunctions on the surface of WZ-MCS NPs through loading MnWO4 NPs, the PHE rate of WZ-MCS/MW NPs improves to 15.2 mmol·g−1·h−1, an increase of 1.3 times. However, due to the limited bulk charge separation in WZ-MCS NPs, surface charge separation through S-scheme heterojunctions in WZ-MCS/MW NPs shows only modest improvement. To further optimize bulk charge separation in MnxCd1-xS solid solutions, the PHE performance of a series of MnxCd1-xS solid solutions (x = 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1) was investigated (Supplementary Fig. 10). SL-MCS NRs (x = 0.5) exhibit a notable PHE rate of 33.3 mmol·g−1·h−1 (also shown in Fig. 4a), benefiting from the regulation of the electronic band structure through the solid solution effect between Mn and Cd (Supplementary Fig. 11) within the MnxCd1-xS solid solutions16. This PHE activity of SL-MCS NRs is 2.9 times higher than that of pristine WZ-MCS NPs, mainly due to the pivotal ZB/WZ superlattice interfaces that enable effective bulk charge separation.

a Average PHE rate, where N.D. represents no detection. b The optical absorbance-dependent AQE measurement of SL-MCS/MW NRs. Error bars in (a) and (b) represent standard deviation. c Cycling stability test of SL-MCS/MW NRs. d Comparison of PHE performance and AQE (λ = 420 nm) with different reported photocatalysts marked by numbers 1–14. 1: Mn0.8Cd0.2S (no interface), 2: Mn0.25Cd0.75S/MoS2 (Schottky interface), 3: NiS/Mn0.25Cd0.75S (Schottky interface), 4: FeWO4/Mn0.5Cd0.5S (p-n junction), 5: CdWO4/Mn0.5Cd0.5S (Z-scheme heterojunction), 6: CdS/PT polymer (S-scheme heterojunction), 7: g-C3N4/CdS/TiO2 DRSP (dual S-scheme heterojunctions), 8: HOCN-0.01 (homojunction & Ohmic contact), 9: CZS/NiSx (twin homojunction & Schottky heterojunction), 10: CdZnS NCSSs (twin homojunction), 11: Ni-Cd0.5Zn0.5S (twin homojunction & Schottky heterojunction), 12: Cd0.5Zn0.5S/WO3-x (twin homojunction & Z-scheme heterojunction), 13: (3CdS/Au)-4ZnS QDNWs (quasi-superlattice interface), and 14: Cu1.8S-ZnS ASLNWs (quasi-superlattice interface).

Furthermore, when the superlattice interface and S-scheme heterojunction work in synergy in SL-MCS/MW NRs, a high PHE activity of 54.4 mmol·g−1·h−1 is achieved, 4.8 times higher than that of pristine WZ-MCS NPs. This is accompanied by the emergence of numerous H2 bubbles (Supplementary Movie 1) under simulated solar irradiation, without any noble-metal or noble-metal-free cocatalysts. The synergy between the superlattice interface and the S-scheme heterojunction promotes ultrafast, universal spatial charge separation and transfer, which significantly enhances PHE performance. The highest AQE of 63.1% at 420 nm demonstrates the efficient utilization of visible light by SL-MCS/MW NRs for PHE (shown in Fig. 4b, with calculation details in Supplementary Table 3). Regarding cycling stability (Fig. 4c), the PHE performance of SL-MCS/MW NRs initially increases due to the activity induction process and then fundamentally remains stable after 7 cycles, over a total of 21 hours24. The corresponding synergistic interface structure maintains relative stability after cycling test (Supplementary Fig. 12a, b). As summarized in Fig. 4d and Supplementary Table 4, the SL-MCS/MW NRs exhibit significantly higher PHE rates and AQE compared to many reported representative interfacial modification structures. This impressive PHE performance is attributed to the synergistic effect between the ZB/WZ superlattice interface and the S-scheme heterojunction. Under natural sunlight irradiation, abundant H2 bubbles are also observed escaping from the surface of SL-MCS/MW NRs (Supplementary Movie 2), highlighting their potential as a promising candidate for solar-to-H2 applications through water splitting.

Qualitative analysis of band edge

According to ultraviolet−visible diffuse reflectance spectra (UV-Vis DRS, Supplementary Fig. 13a), the steady-state optical absorption band edge of SL-MCS NRs shows a slight blue shift compared to pristine WZ-MCS NPs. As indicated by the corresponding Tauc plots (Supplementary Fig. 13b), the optical bandgaps of WZ-MCS NPs and SL-MCS NRs are 2.39 eV and 2.56 eV, respectively. This increase is primarily due to the modulation of the electronic band structure by the coherent ZB/WZ superlattice interface. After constructing S-scheme heterojunctions with a modest amount of fine MnWO4 NPs, the absorption band edge of SL-MCS/MW NRs shows almost no change compared to that of SL-MCS NRs. Similarly, WZ-MCS/MW NPs with single S-scheme heterojunctions exhibit little variation, as MnWO4 NPs with a wide bandgap of 2.79 eV do not significantly affect the optical absorption. Based on Mott-Schottky plots (Supplementary Fig. 14a), it can be inferred that WZ-MCS, SL-MCS NRs, and MnWO4 are typical n-type semiconductors. The flat-band potential as an energy level can be approximately equivalent to the conduction band minimum (CBM) energy level relative to the same reference electrode. When combined with the optical bandgap, the band alignment of the catalysts is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 14b. The CBM energy level (vs. SHE, pH = 7) of SL-MCS NRs is −0.85 V, which is more negative than that of the other samples and the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) potential of −0.41 V (vs. SHE, pH = 7). This indicates that the photogenerated electrons in SL-MCS NRs are thermodynamically more energetic for the photoreduction of H2O molecules44,45,46.

Mechanism of bulk charge separation via superlattice interface

The impressive PHE activity of SL-MCS/MW NRs arises from the highly efficient charge separation. To investigate the mechanism of bulk charge separation in SL-MCS NRs, density functional theoretical (DFT) calculations were conducted to examine the role of the ZB/WZ superlattice interface compared to pristine WZ-MCS (see Supplementary Fig. 15, Supplementary Data 1, 2 and Supplementary Tables 5, 6 for details on the bulk models). No notable difference in the projected density of states (PDOS, Supplementary Fig. 16) was observed between WZ-MCS and SL-MCS. The S 3p and S 3s/Cd 5s hybrid orbitals predominantly contribute to the valence band maximum (VBM) and CBM energy level, respectively, similar to typical direct-bandgap CdS with a high photon-induced transition probability from VBM to CBM47. However, the spatial distribution of frontier energy level, along with the electrostatic potential distribution (Fig. 5a–d and Supplementary Note 2) reveals intriguing differences between WZ-MCS and SL-MCS. For WZ-MCS without ZB/WZ superlattice interfaces, the spatial distributions of the VBM and CBM are highly similar (Fig. 5a). Both photoexcited holes and electrons are broadly distributed across all S atoms in the bulk lattice of WZ-MCS, leading to inevitable rapid recombination of charge carriers. This recombination is further exacerbated by the weak spontaneously induced homogeneous internal electric field (IEF, Fig. 5b).

a Partial charge density and (b) macro-average electrostatic potential line profiles of WZ-MCS. c Partial charge density and (d) macro-average electrostatic potential line profiles of SL-MCS. Insets in (a, c) are partial charge density distribution images with cyan isosurface value of 0.001 e/Bohr3.

In contrast, the abundant ZB/WZ superlattice interfaces in SL-MCS NRs regulate not only the spatial distribution and concentration of charge carriers but also the spontaneous polarization-induced homogeneous IEF. As shown in Fig. 5c, photoinduced holes on the VBM accumulate primarily in the WZ segments, while electrons on the CBM accumulate in the ZB segments, as further highlighted by the spatial distribution images (insets of Fig. 5c). This represents the initial ultrafast separation process in SL-MCS NRs, occurring within a femtosecond timescale upon photoexcitation near the band edge. Subsequently, the increased spontaneous polarization in SL-MCS NRs via the ZB/WZ superlattice interfaces (Fig. 5d) generates a robust homogeneous IEF along the axial [0001] direction. Electric dipole centers are located at the alternating ZB/WZ superlattice interfaces, driving photoinduced holes and electrons to alternately redistribute at these interfaces. This leads to a secondary ultrafast redistribution process. As a result, the recombination of photoexcited electrons and holes throughout the bulk phase of SL-MCS NRs is effectively suppressed.

Mechanism of surface charge separation via S-scheme heterojunction

DFT calculations were initially conducted to predict the possible direction of the heterogeneous IEF after forming an intimate interfacial contact between SL-MCS NRs and MnWO4 NPs. According to the contact orientation in Fig. 3f, corresponding surface and interface slab models were constructed (Supplementary Fig. 17, Supplementary Data 3–5 and Supplementary Tables 5 and 6). Theoretical work functions of SL-MCS-(01\(\bar{1}\)1) and MnWO4-(020) were calculated to be 5.70 eV and 6.07 eV, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 18a, b), implying that electrons are more likely to transfer from SL-MCS-(01\(\bar{1}\)1) to MnWO4-(020) after contact. The electron density difference line profile of SL-MCS/MW clearly illustrates that 0.238 electrons transfer from SL-MCS-(01\(\bar{1}\)1) to MnWO4-(020) after forming a heterojunction (Supplementary Fig. 18c, d). Consequently, this electron transfer generates an IEF from SL-MCS NRs towards the attached MnWO4 NPs at the heterointerface.

Similarly, in situ illumination X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (ISI-XPS, Supplementary Fig. 19a–f) reveals that the binding energies of Mn 2p1/2 and Mn 2p3/2 (Supplementary Fig. 19b) in SL-MCS/MW NRs are more positive than those in SL-MCS NRs. The same trend is observed for Cd 3d (Supplementary Fig. 19c) and S 2p (Supplementary Fig. 19d). In contrast, the W 4f spectra (Supplementary Fig. 19e) show that the peaks corresponding to 4f5/2 and 4f7/2 in SL-MCS/MW NRs shift negatively compared to pure MnWO4, a trend also seen for lattice oxygen (Olattice) in the O 1s spectra (Supplementary Fig. 19f). These findings strongly indicate that the tightly adhered MnWO4 NPs accept electrons from SL-MCS NRs in the dark state, forming a heterogeneous IEF from SL-MCS NRs to MnWO4 NPs. Upon illumination, the peaks of Mn 2p, Cd 3d, and S 2p attributed to SL-MCS NRs in the SL-MCS/MW NRs shift negatively compared to the dark state. On the contrary, the peaks of W 4f and O 1s of Olattice assigned to MnWO4 NPs in SL-MCS/MW NRs shift positively.

Identically, in the photo-irradiated Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM, Fig. 6a), a typical SL-MCS/MW nanorod was randomly selected for the measurement. Upon illumination, the surface potential of the entire SL-MCS nanorod decreases markedly from 741.5 mV to 712.2 mV (areas near point A in Fig. 6b, c and corresponding line profiles in Fig. 6d), as also shown in Supplementary Fig. 20. Distinctly, a small region assigned to MnWO4 NPs presents an increased surface potential, rising from 732.7 mV to 770.0 mV compared to the dark state (area near point B in Fig. 6b, c and corresponding line profiles in Fig. 6d). Taking the band alignment into account (Supplementary Fig. 14a, b), the phenomenon strongly supports the conclusion that photoinduced electrons and holes extensively concentrate on the surfaces of SL-MCS NRs and the attached MnWO4 NPs, both possessing vigorous photoredox capabilities. Fundamentally, the heterogeneous IEF in the S-scheme heterojunction extracts photoinduced holes from SL-MCS NRs, which are then immediately quenched by photoinduced electrons from the attached MnWO4 NPs within the depletion layer, enabling surface charge separation (Fig. 6e). As a result, the average lifetime of photoexcited electrons at the ZB/WZ superlattice interfaces in SL-MCS NRs, with their enhanced reducibility, is significantly prolonged, allowing them to be captured by adsorbed H2O molecules on the surface. Furthermore, only the heterogeneous IEF, which spans both the top and side surfaces (whether near the superlattice interfaces or not) of SL-MCS NRs, can achieve ultrafast and universal charge separation and transfer, facilitated by the synergy between the superlattice interface and the S-scheme heterojunction (Supplementary Fig. 21 and Supplementary Note 3).

a Atomic force microscopy (AFM) image of SL-MCS/MW NRs. Corresponding surface potential distribution (b) under dark state and (c) light irradiation of 420 nm. d Line profiles of surface potential from point A to B, marked in (b) and (c). e Schematic illustration of charge separation and transfer mechanism of S-scheme heterojunction in SL-MCS/MW NRs.

Validation of ultrafast charge separation and transfer in SL-MCS/MW NRs

Given that the ultrafast and universal charge separation and transfer mechanism in SL-MCS/MW NRs has been elucidated, femtosecond transient absorption (fs-TA) spectroscopy was further employed to provide deeper insights into this ultrafast process. It is noted that all signals from the as-prepared samples originate from Mn0.5Cd0.5S, particularly in WZ-MCS/MW and SL-MCS/MW NRs, due to the S-scheme charge separation and transfer mechanism (Supplementary Note 4). As shown in Fig. 7a–d and Supplementary Fig. 22a–d, two intrinsic signals are prominently observed at ~440 nm and ~475 nm in all catalysts suspended in MeCN, corresponding to the ground-state bleach (GSB) and excited-state absorption (ESA) near the band edge, respectively. Both the GSB and ESA signals gradually intensify, from WZ-MCS to SL-MCS/MW NRs. This can be attributed to the extended spatial scale of charge carrier separation, which enhances ground-state absorption and excited-state reabsorption, while also suppressing the decay kinetics of GSB and ESA signals. In addition, the decline of ESA signals to negative values in all catalysts indicates that the higher excited states gradually quench to the lowest excited state rather than returning to the ground state48.

When suspended in water (Fig. 7e–h and Supplementary Fig. 22e–h), the augmented GSB signals of all catalysts display red shifts to ~450 nm. Besides, the ESA signals near the band edge shift positively to ~480 nm and rapidly quench to GSB signals, primarily due to the solvent polarization effect of H2O molecules rather than the capture of photoinduced electrons by adsorbed H2O molecules49, because the positive ESA signal decay is not observed in any of the as-prepared photocatalysts. As the CBM of all catalysts is close to the equilibrium potential of H+/H2 (Supplementary Fig. 14b), the adsorbed H2O molecule-derived surface states (ADSS) significantly influence the rapid decay of GSB signals. In particular, the kinetic decay of GSB signals at ~450 nm and ~480 nm (quenched from ESA signals) is notably accelerated in water for all catalysts, showing an opposite decay trend from WZ-MCS to SL-MCS/MW NRs compared to that in MeCN (Fig. 7a–d). This demonstrates that, with the extended spatial separation of charge carriers, the ADSS on Mn0.5Cd0.5S swiftly capture the photoexcited electrons occupying the CBM, leading to an enhanced charge transfer rate (also reflected in Supplementary Fig. 23a, b)50,51.

It is crucial to quantitatively compare the decay kinetics of the excited states among all catalysts (Fig. 8 and Supplementary Table 7). The intrinsic decay kinetics of GSB signals at 440 nm for all catalysts suspended in MeCN (Fig. 8a–d and Supplementary Table 7) can be deconstructed into reabsorption (RA, τ1), vibrational relaxation & internal conversion (VR&IC, τ2) of the excited state. The ESA signals at 475 nm are fitted by VR&IC (τ1), stimulated emission (SE, τ2) and nonradiative relaxation (to the lowest excited state) of the higher excited state (τ3).

From WZ-MCS to SL-MCS/MW NRs, both τ1 and the average lifetime (τave) of GSB signals are progressively elongated, from 0.2 ps (2.9%) to 1.3 ps (52.6%) and from 1.3 ps to 4.0 ps, respectively, which reflects the significant concentration of photoinduced charge carriers in SL-MCS/MW NRs due to ultrafast and universal spatial separation. In terms of the decay kinetics of ESA signals in MeCN, τ2 for pristine WZ-MCS (990.5 ps, 46.9%) and WZ-MCS/MW (986.8 ps, 43.1%) remains similar, because a single S-scheme heterojunction cannot efficiently extract photoinduced holes from the bulk WZ-MCS to quench photoexcited electrons in the loaded MnWO4, thus promoting inherent radiative recombination. Although the superlattice interfaces in SL-MCS NRs improve bulk separation to generate numerous photogenerated charge carriers, the absence of surface separation leads to a noticeable tendency for radiative recombination (1224.9 ps, 36.7%). Conversely, in SL-MCS/MW NRs, the synergy between superlattice interface and the S-scheme heterojunction significantly suppresses radiative recombination (134.3 ps, 4.2%) compared to other catalysts. Accordingly, τ3 and τave of ESA signal in SL-MCS/MW NRs reach the longest lifetimes of 1857.0 ps (92.6%) and 1727.7 ps, respectively, indicating the prolonged excited-state lifetimes due to the synergistic interfaces.

As shown in Fig. 8e–h and Supplementary Table 7, the decay kinetics of GSB signals at 450 nm for all catalysts suspended in water can be fitted by RA (τ1) of the excited state and VR&IC (τ2). However, the GSB signals at 480 nm require fitting with different multi-exponential decay models due to distinct decay characteristics (Supplementary Note 5). From WZ-MCS to SL-MCS/MW NRs, all τave for the GSB signals at 450 nm (which quickly quenches to zero) are very similar, primarily due to the reabsorption at shorter wavelength than 450 nm (Fig. 8e–h and Supplementary Table 7). Regarding the decay kinetics of GSB signals at 480 nm near the band edge, restricted ADSS capture (τ2, 180.3 ps, 16.2%) occurs in pristine WZ-MCS due to limited charge separation, with a tendency toward radiative recombination (τ3, 1093.8 ps, 83.2%). Surprisingly, this decay course gradually accelerates from WZ-MCS (τave, 939.3 ps) to SL-MCS/MW NRs (τave, 1.8 ps) with the acceleration of ADSS capture (τ2) from 180.3 ps (16.2%) to several picoseconds. Therefore, the synergistic interfaces between the superlattice and S-scheme heterojunctions enable boosted ultrafast charge separation and transfer (also reflected in Supplementary Fig. 23a, b) and ADSS capture. In addition, the decay kinetics near the band edge (GSB signals at 480 nm in water) of ADSS capture (τ2 in several picoseconds) is closely linked to PHE activity. In other word, the photoinduced electrons on the surface of SL-MCS/MW NRs can be effectively captured by the abundantly adsorbed H2O molecules with the fastest kinetics, further validating the advantages provided by the synergy between superlattice interfaces and S-scheme heterojunctions.

The overall process of ultrafast and universal spatial charge separation and transfer in SL-MCS/MW NRs for productive PHE is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 24. ZB/WZ superlattice interfaces create a homogeneous IEF throughout the bulk of SL-MCS NRs along the [0001] axial direction, completely separating photoinduced charge carriers at alternate superlattice interfaces. Simultaneously, a heterogeneous IEF at the S-scheme heterojunctions between SL-MCS NRs and loaded MnWO4 NPs effectively extracts photoexcited holes from the superlattice interfaces, which are then swiftly quenched by photoexcited electrons from MnWO4. As a result, the photoexcited electrons with stronger reducibility at the ZB/WZ superlattice interfaces of SL-MCS NRs are retained and promptly captured by adsorbed H2O molecules within several picoseconds. The photoinduced holes with higher oxidizability on MnWO4 NPs are quickly trapped by the sacrificial agents S2- and \({\mbox{S}}{{\mbox{O}}}_{3}^{2-}\)16,52. Therefore, with synergistic interfaces in SL-MCS/MW NRs, ultrafast and universal charge separation and transfer are achieved, leading to high PHE activity.

Discussion

Building on the logical framework of universal spatial charge separation, SL-MCS/MW NRs with a synergistic interface structure were carefully fabricated. The interfacial synergy, mediated by the robust IEF in superlattice interfaces and S-scheme heterojunctions, successfully enables ultrafast and universal spatial charge separation and transfer in SL-MCS/MW NRs, as thoroughly explained through DFT calculations, in situ illumination characterization and fs-TA techniques. In this context, compared to pristine WZ-MCS, SL-MCS/MW NRs demonstrate a high PHE rate of 54.4 mmol·g−1·h−1 under simulated solar irradiation (up to ~4.8 times than that of pristine WZ-MCS) and AQE of 63.1% at 420 nm without any noble-metal or noble-metal-free cocatalysts. Notably, this work offers valuable insights into interfacial structure design for efficient photocatalysis and other photoelectric conversion applications.

Methods

Materials

Mn(Ac)2 · 4H2O (AR, ≥99%), Cd(Ac)2 · 2H2O (AR, ≥98%), Na2WO4 · 2H2O (AR, ≥99%), thioacetamide (TAA, AR, ≥99%), L-cysteine (AR, ≥99%) and granular NaOH (AR, ≥99%) were purchased from Shanghai Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Anhydrous ethylenediamine (EDA, AR, ≥99%) was purchased from Shanghai Lingfeng Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Hydrochloric acid was purchased from Chengdu Kelong Chemical Co., Ltd. Anhydrous acetonitrile (MeCN, standard for GC, ≥99.9%) was obtained from Aladdin Reagent Co. Ltd. All chemical reagents were used without further purification and ultrapure water (18.25 MΩ·cm−1) was used throughout the whole experiment.

Synthesis of MnxCd1-xS solid solution

MnxCd1-xS solid solution (x = 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1) was prepared by precipitation-solvothermal method, where Mn0.5Cd0.5S was termed as SL-MCS NRs. Typically for CdS (x = 0), 1.6 g granular NaOH was firstly dissolved in 60 mL mixture of EDA and H2O (v/v = 1:5, pH = 13 under R.T.). Then, 10 mmol (2.665 g) Cd(Ac)2·2H2O was added into above solution with continuously and vigorously magnetic stirring of 30 min to produce plentiful dark brown precipitation, followed by adding 20 mmol TAA. Typically for Mn0.25Cd0.75S (x = 0.25), 1.6 g granular NaOH was firstly dissolved in 60 mL mixture of EDA and H2O (v/v = 1:5, pH = 13 under R.T.). Then, 2.5 mmol (0.613 g) Mn(Ac)2·4H2O and 7.5 mmol (1.999 g) Cd(Ac)2·2H2O and were simultaneously added into above solution with continuously and vigorously magnetic stirring of 30 min to produce plentiful dark brown precipitation, followed by adding 20 mmol TAA. Typically for SL-MCS NRs (x = 0.5), 1.6 g granular NaOH was firstly dissolved in 60 mL mixture of EDA and H2O (v/v = 1:5, pH = 13 under R.T.). Then, 5 mmol (1.226 g) Mn(Ac)2·4H2O and 5 mmol (1.333 g) Cd(Ac)2·2H2O and were simultaneously added into above solution with continuously and vigorously magnetic stirring of 30 min to produce plentiful dark brown precipitation, followed by adding 20 mmol TAA. Typically for Mn0.75Cd0.25S (x = 0.75), 1.6 g granular NaOH was firstly dissolved in 60 mL mixture of EDA and H2O (v/v = 1:5, pH = 13 under R.T.). Then, 7.5 mmol (1.838 g) Mn(Ac)2·4H2O and 2.5 mmol (0.666 g) Cd(Ac)2·2H2O and were simultaneously added into above solution with continuously and vigorously magnetic stirring of 30 min to produce plentiful dark brown precipitation, followed by adding 20 mmol TAA. Typically for MnS (x = 1), 1.6 g granular NaOH was firstly dissolved in 60 mL mixture of EDA and H2O (v/v = 1:5, pH = 13 under R.T.). Then, 10 mmol (2.451 g) Mn(Ac)2·4H2O was added into above solution with continuously and vigorously magnetic stirring of 30 min to produce plentiful dark brown precipitation, followed by adding 20 mmol TAA. Subsequently, the mixtures were transferred into a 100 mL PPL-lined autoclave along with steadily magnetic stirring of 1000 rpm and maintained at 180 °C for 18 h. After cooling down to R.T., the products were obtained via centrifugation and washing with ethanol and ultrapure water by three times at least, finally dried at 60 °C in vacuum oven overnight.

Synthesis of WZ-MCS and ZB-MCS

Both of WZ-MCS and ZB-MCS were synthesized by hydrothermal methods53. As for WZ-MCS, 5 mmol (1.226 g) Mn(Ac)2·4H2O and 5 mmol (1.333 g) Cd(Ac)2·2H2O were fully dissolved in 60 mL ultrapure water with magnetic stirring of 30 min, followed by adding 20 mmol (2.423 g) L-cysteine till the solution turned yellow. Then, the mixture was moved into a 100 mL PPL-lined autoclave with magnetic stirring of 1000 rpm and maintained at 180 °C for 18 h. The operation of gathering products was analogous to SL-MCS NRs. For ZB-MCS NPs, the procedure was same as that of WZ-MCS, except the replacement of 20 mmol (2.423 g) L-cysteine with 10 mmol (0.751 g) TAA.

Synthesis of SL-MCS/MW-x NRs composites

All composites were fabricated by hydrothermal methods. Initially, 0.1 g SL-MCS NRs was ultrasonically dispersed in 30 mL ultrapure water for 10 min, called suspension A. Then, the pH value of another 30 mL ultrapure water was adjusted to 2.3 at R.T. with diluted HCl (aq.), followed by dissolving Na2WO4·2H2O of 0.0285 g, 0.0711 g and 0.1423 g, respectively, named solution B. Finally, suspension A was blended with solution B and the mixture was stirred thoroughly for 30 min, afterwards transferring into a 100 mL PPL-lined autoclave with magnetic stirring of 1000 rpm and maintained at 160 °C for 4 h. The operation of collecting products was similar to SL-MCS NRs. According to the increasing dosage of Na2WO4·2H2O referring to 0.0285 g, 0.0711 g and 0.1423 g, the as-fabricated composites were recorded as SL-MCS/MW-x (x = 1, 2, 3), where SL-MCS/MW-2 was specially abbreviated to SL-MCS/MW. Besides, WZ-MCS/MW composites with single S-scheme heterojunctions were synthesized in the same way with 0.0711 g Na2WO4·2H2O added.

Synthesis of pure MnWO4

3 mmol (0.735 g) Mn(Ac)2·4H2O and 3 mmol (0.990 g) Na2WO4·2H2O were added into 60 mL ultrapure water with pH = 1.0 at R.T. controlled by diluted HCl (aq.). The solution was kept stirring for 30 min, and then it was moved into a 100 mL PPL-lined autoclave with magnetic stirring of 1000 rpm and maintained at 160 °C for 4 h. The procedure of gathering products was similar to SL-MCS NRs.

Photocatalytic H2 evolution

The PHE performance was conducted to assess the photocatalytic activity of as-prepared photocatalysts through the top-irradiation of AM 1.5 G bandpass filter (100 mW·cm−2, 300 W Xe lamp, Beijing PerfectLight Microsolar300, Beijing) and all glass automatic on-line trace gas analysis system (Beijing PerfectLight Labsolar-6A, Beijing). Specifically, 10 mg catalyst was ultrasonically dispersed in 50 mL 0.35 M Na2S/0.25 M Na2SO3 (aq., pH = 13.22 ± 0.03 under R.T.) solution contained in a quartz reactor, followed by connecting the quartz reactor to the Labsolar-6A on-line reaction system and continuous vacuumizing to evacuate the air inside. Then, it was fed with Ar at ~80 kPa to create inert reaction atmosphere inside. In addition, the Labsolar-6A on-line reaction system was maintained at R.T., while the quartz reactor was kept at 10 °C by circulating water cooling system to avoid the effect of heating. It should be added that the vertical distance and irradiation surface area of top irradiation were 10 cm and 25.5 cm2 for the evaluation of average PHE rate, respectively. Monochromatic bandpass light irradiance was measured by a photoradiometer (Beijing PerfectLight PL−MW2000, Beijing). Finally, the average PHE rate and apparent quantum efficiency (AQE) were both analyzed by an on-line gas chromatography system (GC-2030, Shimadzu, Japan, He as the carrier gas, 5 Å molecular sieve column, and BID detector). For the stability test of as-prepared catalysts during the same reaction conditions, the Labsolar-6A on-line reaction system was evacuated every 3 h and after repeated 7 times to investigate the stability.

Characterizations

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded by a Japan Rigaku D/Max-RB X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.15418 nm) with a constant scanning step of 0.15°/s. Micro-morphology observation was taken on a field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM) (JSM 7500F, JEOL, Japan). High-resolution transmission electron microscope (HR-TEM) images and atomic-resolution scanning transmission electron microscope (STEM) images were recorded by double aberration corrected TEM (Titan Cubed Themis G2 300, FEI, USA) working at 300 kV to characterize atomic-scale microstructure. Energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) mapping images were obtained under the STEM mode. Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) specific surface area and Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) pore size distribution were acquired by N2 adsorption-desorption test at 77.3 K on a Micromeritics ASAP 2020 (USA) instrument. The powder samples were degassed off-line at 100 °C for 24 h under dynamic vacuum (10−5 bar) prior to measurement. Hydrophilicity and static contact angle (CA) test were performed using a drop shape analyzer (Theta Lite Auto 1, Biolin Scientific, Sweden). Inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) (Prodigy 7, Leeman Labs) was utilized for element content analysis of as-prepared catalysts. The ultraviolet−visible diffuse reflectance spectra (UV-Vis DRS) were carried out on a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (UV-2600, Shimadzu, Japan) with BaSO4 as a reference. The transient photocurrent response (I–t), electrochemical impedance spectra (EIS) and Mott-Schottky tests of as-prepared samples were studied by an electrochemical workstation (CHI660C Instruments, China) with a standard three-electrode system in 30 mL 0.5 M Na2SO4 (aq.), where a Ag/AgCl (saturating KCl), a Pt plate and indium tin oxide (ITO) glass coated with the sample worked as the reference, counter electrode and working electrode, respectively. Regarding the preparation of working electrode, firstly, 5 mg powder sample was ultrasonically dispersed thoroughly in a mixture of 200 μL ethanol and 20 μL 5% nafion solution (D-520, DuPont, USA). Then, 20 μL of the mixture was evenly spun onto the conductive surface of ITO glass (0.5 cm × 0.5 cm) and dried in an oven at 60 °C for a moment. Besides, the potential was set as 0.5 V for the measurement of I–t curves and EIS. The Mott-Schottky tests were obtained with the potentials ranging from −0.8 V to 0.5 V at different frequencies (800, 1000, and 1200 Hz). In situ illumination X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (ISI-XPS) under 365-nm light excitation were tested on an electron spectrometer (ESCALAB 250Xi, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) with Al Kα radiation (hv = 1486.7 eV), and all binding energies were referenced to the adventitious carbon C 1s at 284.8 eV. The alteration of surface potential of as-synthesized samples under 420-nm light excitation was tested by photo-irradiated Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM) (SPM-9700, Shimadzu, Japan).

Computational methods

The density functional theory (DFT) was performed with Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)54. The projector augmented wave (PAW) methods were applied to the interactions of valence electrons with the atomic nucleus55. Specifically, Mn 3d64s1, Cd 4d105s2, W 5d56s1, S 3s23p4, O 2s22p4, H 1s1 and a pseudohydrogen model H1.5 (containing 1.5 valence electrons to saturate dangling bonds) were used as the valence configurations. The electron exchange correlation functional used the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) of the generalized gradient approximation (GGA)56. In addition, spin polarization was considered throughout the whole calculations. Due to the magnetic transition metal Mn element involving in all the models and high 3d orbital occupation number of Mn2+, while this hardly occurs in 5d orbital of W6+, we selected GGA + U method to correct strong on-site Coulomb interaction of Mn 3d-electrons under different chemical environment57. The corresponding effective U value (Ueff) were adopted as 5.0 eV and 3.9 eV in [MnS4] tetrahedron and [MnO6] octahedron, respectively58. The k point sampling of Brillouin zone employed 4 × 4 × 1 and 5 × 2 × 1 Monkhorst-Pack scheme centered at gamma point on bulk models (WZ-MCS and SL-MCS) and slab models (SL-MCS-(\(01\bar{1}1\)), MnWO4-(020), and SL-MCS/MW)59. The energy cutoff of the wave function in the plane-wave basis was tested as 400 eV. The DFT-D2 method was used to describe the Van der Waals interaction for all calculations60. With respect to various slab models, vacuum layer thickness was all set to 15 Å to avoid the interactions between neighboring substrates. Furthermore, all the geometry structure optimization calculations were terminated until the maximum force upon each atom and energy were less than 0.02 eV/Å and 1.0 × 10−6 eV. The structure information of fully optimized bulk and surface model was presented in Supplementary Data 1–5.

Femtosecond transient absorption measurement

The femtosecond transient absorption (fs-TA) setup utilized in this investigation is centered around a regenerative amplified Ti:sapphire laser system sourced from Coherent (800 nm, 35 fs, 6 mJ per pulse, and 1 kHz repetition rate), coupled with nonlinear frequency mixing techniques and a pump–probe system (Helios Fire, Ultrafast System). In brief, the 800 nm output pulse from the regenerative amplifier underwent a beam splitter division. The transmitted portion was employed to energize an Optical Parametric Amplifier (OPera Solo), generating a pump beam with a wavelength centered at 340 nm. Simultaneously, the reflected 800 nm beam underwent further splitting. A segment was attenuated via a neutral density filter and focused into a CaF2 crystal to produce a white light continuum (WLC) ranging from 320 nm to 650 nm, utilized as the probe beam. The probe beam was then directed onto the sample via an Al parabolic reflector. Post-sample interaction, the probe beam was collimated and subsequently directed into a fiber-coupled spectrometer, with detection occurring at a frequency of 1 kHz. The temporal separation between the pump and probe pulses was modulated by a motorized delay stage. The pump pulses underwent modulation by a synchronized chopper operating at 500 Hz, with absorbance changes deduced from the juxtaposition of two adjacent probe pulses (pump-blocked and pump-unblocked).

Quantitative samples were dispersed in MeCN and water respectively with same concentration of 0.2 g·L−1. The mixture was added into quartz cuvettes with a path length of 2 mm and evacuated by N2 flow for 5 min to remove the air inside. All data were obtained using an excitation wavelength of 340 nm and optical power of 100 µW·cm−2. The decay curves obtained from the fs-TA spectra (normalized in [−0.5,0.5]) were fitted by the following multi-exponential Eq. (1):

Where A0 represents the baseline correction value, and t is the probe time delay. Ai and τi are amplitudes and decay lifetime, respectively. The relative amplitude fi of according decay component and decay average lifetime τave were calculated by Eq. (2) and Eq. (3), respectively:

Statistics and reproducibility

No statistical method is used to predetermine sample size. No data are excluded from the analyses. The experiments were not randomized. The Investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Data availability

Data can be obtained from the authors upon request. All data produced during this research are included in the Source data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Fujishima, A. & Honda, K. Electrochemical photolysis of water at a semiconductor electrode. Nature 238, 37–38 (1972).

Xia, M., Zhao, X., Zhang, Y., Pan, W. & Leung, D. Y. C. Rational catalyst design for spatial separation of charge carriers in a multi-component photocatalyst for effective hydrogen evolution. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 25380–25405 (2022).

Hu, C. et al. Photocatalysis enhanced by external fields. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 16309–16328 (2021).

Müller, C., Bold, S., Chavarot-Kerlidou, M. & Dietzek-Ivanšić, B. Photoinduced electron transfer in triazole-bridged donor-acceptor dyads—a critical perspective. Coord. Chem. Rev. 472, 214764 (2022).

Cheng, C. et al. In-situ formatting donor-acceptor polymer with giant dipole moment and ultrafast exciton separation. Nat. Commun. 15, 1313 (2024).

Deng, X. et al. Ultrafast electron transfer at the In2O3/Nb2O5 S-scheme interface for CO2 photoreduction. Nat. Commun. 15, 4807 (2024).

Xu, C., Anusuyadevi, P. R., Aymonier, C., Luque, R. & Marre, S. Nanostructured materials for photocatalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 3868–3902 (2019).

Hisatomi, T., Kubota, J. & Domen, K. Recent advances in semiconductors for photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical water splitting. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 7520–7535 (2014).

Osterloh, F. E. Inorganic nanostructures for photoelectrochemical and photocatalytic water splitting. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 2294–2320 (2013).

Cao, S., Piao, L. & Chen, X. Emerging photocatalysts for hydrogen evolution. Trends Chem. 2, 57–70 (2020).

Li, F., Jiang, J., Li, N., Gao, Y. & Ge, L. Design and fabrication of hollow structured Cu2MoS4/ZnIn2S4 nanocubes with significant enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen evolution performance. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 46, 37847–37859 (2021).

Luo, J., Lin, Z., Zhao, Y., Jiang, S. & Song, S. The embedded CuInS2 into hollow-concave carbon nitride for photocatalytic H2O splitting into H2 with S-scheme principle. Chin. J. Catal. 41, 122–130 (2020).

Luo, N. et al. Photocatalytic coproduction of deoxybenzoin and H2 through tandem redox reactions. ACS Catal. 10, 762–769 (2020).

Chen, Y.-G. et al. Synergetic integration of Cu1.94S-ZnxCd1-xS heteronanorods for enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic hydrogen production. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 4286–4289 (2016).

Jiang, X.-W. et al. In situ photodeposition of metalloid Ni2P co-catalyst on Mn0.5Cd0.5S for enhanced photocatalytic H2 evolution with visible light. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 46, 5197–5206 (2021).

Li, L. et al. Highly efficient colloidal MnxCd1-xS nanorod solid solution for photocatalytic hydrogen generation. J. Mater. Chem. A 6, 23683–23689 (2018).

Liu, X.-L. et al. Highly efficient and noble metal-free NiS modified MnxCd1-xS solid solutions with enhanced photocatalytic activity for hydrogen evolution under visible light irradiation. Appl. Catal. B 203, 282–288 (2017).

Su, D. W. et al. Atomically dispersed Ni in cadmium-zinc sulfide quantum dots for high-performance visible-light photocatalytic hydrogen production. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz8447 (2020).

Chen, R.-F. et al. Rational design of isostructural 2D porphyrin-based covalent organic frameworks for tunable photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–9 (2021).

Wu, S.-H. et al. Crystalline covalent organic frameworks with tailored linkages for photocatalytic H2 evolution. ChemSusChem 14, 4958–4972 (2021).

Qian, Y. et al. Computation-based regulation of excitonic effects in donor-acceptor covalent organic frameworks for enhanced photocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 14, 3083 (2023).

Shi, Y., Yang, A.-F., Cao, C.-S. & Zhao, B. Applications of MOFs: recent advances in photocatalytic hydrogen production from water. Coord. Chem. Rev. 390, 50–75 (2019).

Wen, M.-C., Mori, K., Kuwahara, Y., An, T.-C. & Yamashita, H. Design and architecture of metal organic frameworks for visible light enhanced hydrogen production. Appl. Catal. B 218, 555–569 (2017).

Wan, S.-J., Xu, J.-S., Cao, S.-W. & Yu, J.-G. Promoting intramolecular charge transfer of graphitic carbon nitride by donor–acceptor modulation for visible–light photocatalytic H2 evolution. Interdiscip. Mater. 1, 294–308 (2022).

Zhao, C.-X., Chen, Z.-P., Shi, R., Yang, X.-F. & Zhang, T.-R. Recent advances in conjugated polymers for visible-light-driven water splitting. Adv. Mater. 32, 1907296 (2020).

Yang, C., Wan, S.-J., Zhu, B.-C., Yu, J.-G. & Cao, S.-W. Calcination-regulated microstructures of donor-acceptor polymers towards enhanced and stable photocatalytic H2O2 production in pure water. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202208438 (2022).

Cheng, J., Wan, S. & Cao, S. Promoting solar-driven hydrogen peroxide production over thiazole-based conjugated polymers via generating and converting singlet oxygen. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202310476 (2023).

Zhao, K. et al. Surface oxygen vacancy modified Bi2MoO6/MIL-88B(Fe) heterostructure with enhanced spatial charge separation at the bulk & interface. Appl. Catal. B 268, 118740 (2020).

Chen, F., Ma, T., Zhang, T., Zhang, Y. & Huang, H. Atomic-level charge separation strategies in semiconductor-based photocatalysts. Adv. Mater. 33, 2005256 (2021).

Zhang, L.-Y., Zhang, J.-J. & Yu, H.-G. & Yu, J.-G. Emerging S-scheme photocatalyst. Adv. Mater. 34, 2107688 (2022).

Xu, Q.-L., Zhang, L.-Y., Cheng, B., Fan, J.-J. & Yu, J.-G. S-Scheme heterojunction photocatalyst. Chem 6, 1543–1559 (2020).

Ruan, X. et al. Artificial photosynthetic system with spatial dual reduction site enabling enhanced solar hydrogen production. Adv. Mater. 36, 2309199 (2024).

Zhao, B. et al. High-order superlattices by rolling up van der Waals heterostructures. Nature 591, 385–390 (2021).

Jin, G. et al. Heteroepitaxial van der Waals semiconductor superlattices. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 1092–1098 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Pulsed axial epitaxy of colloidal quantum dots in nanowires enables facet-selective passivation. Nat. Commun. 9, 4947 (2018).

Liu, M.-C., Jing, D.-W., Zhou, Z.-H. & Guo, L.-J. Twin-induced one-dimensional homojunctions yield high quantum efficiency for solar hydrogen generation. Nat. Commun. 4, 1–8 (2013).

Liu, M.-C., Wang, L.-Z., Lu, G.-Q., Yao, X.-D. & Guo, L.-J. Twins in Cd1-xZnxS solid solution: highly efficient photocatalyst for hydrogen generation from water. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 1372–1378 (2011).

Zhang, K. et al. Polarization-induced saw-tooth-like potential distribution in zincblende-wurtzite superlattice for efficient charge separation. Nano Energy 41, 101–108 (2017).

Liu, M. et al. Photocatalytic hydrogen production using twinned nanocrystals and an unanchored NiSx co-catalyst. Nat. Energy 1, 16151 (2016).

Li, Z. et al. Mechanically controlling the reversible phase transformation from zinc blende to wurtzite in AlN. Mater. Res. Lett. 5, 426–432 (2017).

Sun, S., Zhang, X., Cui, J., Yang, Q. & Liang, S. Twin engineering of photocatalysts: a minireview. Catal. Sci. Technol. 10, 4164–4178 (2020).

Liu, M., Jing, D., Zhou, Z. & Guo, L. Twin-induced one-dimensional homojunctions yield high quantum efficiency for solar hydrogen generation. Nat. Commun. 4, 2278 (2013).

Hÿtch, M. J., Snoeck, E. & Kilaas, R. Quantitative measurement of displacement and strain fields from HREM micrographs. Ultramicroscopy 74, 131–146 (1998).

Qi, M.-Y., Conte, M., Anpo, M., Tang, Z.-R. & Xu, Y.-J. Cooperative coupling of oxidative organic synthesis and hydrogen production over semiconductor-based photocatalysts. Chem. Rev. 121, 13051–13085 (2021).

Chen, X., Shen, S., Guo, L. & Mao, S. S. Semiconductor-based photocatalytic hydrogen generation. Chem. Rev. 110, 6503–6570 (2010).

Suzuki, T., Watanabe, H., Oaki, Y. & Imai, H. Tuning of photocatalytic reduction by conduction band engineering of semiconductor quantum dots with experimental evaluation of the band edge potential. Chem. Commun. 52, 6185–6188 (2016).

Wang, T. et al. Indirect to direct bandgap transition in methylammonium lead halide perovskite. Energy Environ. Sci. 10, 509–515 (2017).

Zhang, J., Zhu, B., Zhang, L. & Yu, J. Femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy investigation into the electron transfer mechanism in photocatalysis. Chem. Commun. 59, 688–699 (2023).

Kong, J. et al. Bridge-length- and solvent-dependent charge separation and recombination processes in donor–bridge–acceptor molecules. J. Phys. Chem. B 125, 13279–13290 (2021).

Brown, A. M. et al. Ultrafast electron transfer between dye and catalyst on a mesoporous NiO surface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 8060–8063 (2016).

Edme, K., Bettis Homan, S., Nepomnyashchii, A. B. & Weiss, E. A. Ultrafast exciton decay in PbS quantum dots through simultaneous electron and hole recombination with a surface-localized ion pair. Chem. Phys. 471, 46–53 (2016).

Schneider, J. & Bahnemann, D. W. Undesired role of sacrificial reagents in photocatalysis. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 3479–3483 (2013).

Wang, C.-X. et al. Highly efficient photocatalytic H2 evolution over NiCo2S4/Mn0.5Cd0.5S: bulk twinned homojunctions and interfacial heterojunctions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 592, 66–76 (2021).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple [Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996)]. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 1396–1396 (1997).

Anisimov, V. I., Zaanen, J. & Andersen, O. K. Band theory and Mott insulators: Hubbard U instead of Stoner I. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter 44, 943–954 (1991).

Dudarev, S., Botton, G. A., Savrasov, S. Y., Humphreys, C. & Sutton, A. P. Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: an LSDA + U study. Phys. Rev. B 57, 1505–1509 (1998).

Chadi, D. J. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 16, 1746–1747 (1977).

Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 27, 1787–1799 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFE0114800, S.C.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (22278324, B.C. and 52073223, B.C.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptional layout: S.C., J.Y., S.W., W.W., and J.Z. Investigation: S.C., J.Y., S.W., W.W., J.Z., B.C., G.L., Q.S., and L.Z. Experimental data collection and processing: S.W. Computational simulation: S.W. Manuscript co-writing: S.W. and W.W. Manuscript revising: S.C., J.Y., S.W., W.W., and J.Z. Funding acquisition: S.C. and B.C. Supervision: S.C. and J.Y.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Xinlong Tian, Zhiliang Jin and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wan, S., Wang, W., Cheng, B. et al. A superlattice interface and S-scheme heterojunction for ultrafast charge separation and transfer in photocatalytic H2 evolution. Nat Commun 15, 9612 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53951-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53951-6

This article is cited by

-

Structural and Optical Engineering of Bi2O3 Nanostructures for Enhanced Visible-Light Photocatalysis

Catalysis Letters (2026)

-

Integrating the bicrystalline monoclinic-tetragonal BiVO4 with g-C3N4 to form S-scheme heterojunction for bromocresol green dye degradation under visible light

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2026)

-

Asymmetric coordination enhances the synergy of Pt species dual active sites for efficient photocatalytic H2 evolution

Nature Communications (2025)

-

BiVO4/SnS2 S-scheme heterojunction for improved photocatalytic performance under visible light: charge carrier mechanism validation by DFT and electrochemical studies

Applied Physics A (2025)

-

From type-I heterojunction to high-low junction: Novel charge transfer mechanisms and recent advances

Science China Technological Sciences (2025)