Abstract

Electrochemical CO2 reduction reaction (CO2RR) occurring at the electrode/electrolyte interface is sensitive to both the potential and concentration polarization. Compared to static electrolysis at a fixed potential, pulsed electrolysis with alternating anodic and cathodic potentials is an intriguing approach that not only reconstructs the surface structure, but also regulates the local pH and mass transport from the electrolyte side in the immediate vicinity of the cathode. Herein, via a combined online mass spectrometry investigation with sub-second temporal resolution and 1-dimensional diffusion profile simulations, we reveal that heightened surface CO2 concentration promotes CO2RR over H2 evolution for both polycrystalline Ag and Cu electrodes after anodic pulses. Moreover, mild oxidative pulses generate a roughened surface topology with under-coordinated Ag or Cu sites, delivering the best CO2-to-CO and CO2-to-C2+ performance, respectively. Surface-enhanced infrared absorption spectroscopy elucidates the potential dependence of *CO and *OCHO species on Ag as well as the gradually improved *CO consumption rate over under-coordinated Cu after oxidative pulses, directly correlating apparent CO2RR selectivity with dynamic interfacial chemistry at the molecular level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electrochemical CO2 reduction reaction (CO2RR) represents a promising approach for mitigating anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions while simultaneously facilitating the storage of intermittent renewable energy in the form of carbon-based fuels and chemicals1,2,3. However, the implementation of CO2RR is hindered by significant challenges, including the competing hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) that occurs during co-electrolysis with H2O4,5, as well as the complex distribution of products resulting from their similar thermodynamic reduction potentials6,7,8.

In past years, great efforts have been devoted to improving the single-target CO2RR product selectivity and its production rate, including but not limited to the intrinsic physicochemical properties regulation of electrocatalysts9,10,11 and extrinsic local reaction environment optimization in the vicinity of the cathode12,13,14. Compared to the former approach with delicate catalyst design, the latter strategy generally involves a more flexible modification of electrolyte composition and concentration15, the ratio of interfacial CO2 and H2O concentrations16, and the adjustment of applied potential or current density17, thus emerging merits of versatility and scalability toward larger scale implementation of CO2 electrolysis.

Among the different tuning knobs on the extrinsic local reaction environment, pulsed CO2RR instead of static electrolysis has been demonstrated as an efficient way to promote CO2RR over HER on Au18, Ag19, and Sn20 surfaces, as well as to promote C-C coupling on Cu toward enhanced C2+ product selectivity21,22,23. Such pulsed electrolysis with square-wave potential could date back to 198924 and has attracted continuous interest, as summarized in an excellent review recently25. So far, different hypotheses on the promotion mechanism for pulsed electrolysis have been proposed:

-

1.

oxidative removal of carbon deposits to avoid electrode degradation19,26.

-

2.

replenishment of CO2 reactant, CO intermediate, and/or specific anions21,22,23.

-

3.

accumulation of OHads and repulsion of surface H+ toward a higher local pH environment27,28,29.

-

4.

surface reconstruction by repeated electrode oxidation and reduction20,30,31,32.

Early mechanism studies on the above hypotheses were largely drawn from statistical product quantification and electric responses, such as cyclic voltammetry and quartz crystal microbalance measurements. With the fast development of in situ and operando spectroelectrochemical techniques, direct evidence at the atomic and/or molecular level has been witnessed in past years. Taking the CO2-to-C2H5OH conversion on Cu square sites, for example, a twofold enhancement has been noticed in pulsed CO2RR compared to static electrolysis31,33. Timoshenko et al. then conducted a set of X-ray radiated spectroelectrochemical studies, pinpointing the key contribution from coexisting metallic and oxidized Cu surface species during pulsed operation. Thereafter, quasi in situ X-ray photoelectron/absorption spectrometry and time-resolved surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) have been deployed to correlate the CO2RR product distribution with the transients of surface valence state and composition during periodic oxidation-reduction cycles30,34,35. In addition to the electrode reconstruction, online differential electrochemical mass spectrometric (DEMS) results coupled with boundary layer simulations21 highlight the transient state of heightened pH and CO(2) concentration at moderate anodic potential switches in promoting C2+ product selectivity, whereas a recent Raman study ascribes the enhancement of C2+ selectivity to the increased population of adsorbed COads intermediate on CuxO/Cu mixed surface sites22.

Noteworthy, CO2RR as a surface-mediated process is highly sensitive to the polarization of both potential and concentration, where the pulsed electrolysis bears more ramifications on potential and time-dependent behaviors. To thoroughly elucidate the underlying promotion mechanisms in pulsed CO2RR, it is crucial to employ a comprehensive in situ spectroelectrochemical approach that can resolve the complex interactions among the cathode surface, the local reaction environment, and adsorbates in real-time. Herein, we present a cross-scale, multi-modal spectroscopic investigation coupled with numerical simulations to tackle the dynamic interfacial chemistry during pulsed CO2RR on polycrystalline Ag and Cu electrodes. The pulsed CO2RR, conducted under mild anodic oxidation potential, is identified as the optimal operating condition for enhancing CO2-to-CO conversion on Ag as well as for CO2-to-C2+ conversion on Cu. Real-time DEMS results and simulated 1-D diffusion profiles underscore the beneficial effect of heightened surface CO2 concentration on CO2RR over HER for both electrodes after anodic pulses, whereas direct observation on steered CO2RR pathways influenced by surface adsorbates at different applied potentials is achieved through in situ attenuated total reflection surface-enhanced infrared absorption spectroscopy (ATR-SEIRAS).

Results

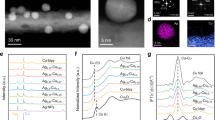

Pulsed electrolysis on Ag

Given its simple product distributions, Ag-catalyzed CO2RR has been carried out with either a static cathodic potential or a pulsed square-wave potential (Fig. 1a) to validate the promotion effect, as well as to optimize the pulse conditions. The cathodic potential (Ec) was fixed at − 1.1 V vs. reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE), where the conversion of CO2-to-CO reaches peak Faradaic efficiency (FE)36. Two anodic potentials (Ea) of − 0.2 V and + 0.7 V were employed, the former represents a shutdown condition in the absence of a Faradaic reaction, while the latter indicates a mild oxidation condition that exceeds the redox potential of Ag/Ag2O37. The duration for each cathodic and anodic pulse (tc and ta, respectively) was initially fixed at 10 s for comparison. Figure 1b illustrates the distribution of CO2RR products within an H-type cell at different electrolysis conditions, with relevant electrochemical responses plotted in Supplementary Fig. 1. The anodic current density during the + 0.7 V pulse was less than 20 μA cm−2, which is negligible (< 1‰) and does not interfere with product quantification or to electric power consumption. Despite CO being the major product in all three conditions, the FE of H2 was observed to decrease from ~ 10% in static electrolysis to nearly zero in the two pulsed cases, verifying the promotion effect of pulsed potential on CO2RR over HER. Formate, as a minor product in Ag-catalyzed CO2RR, exhibited an FE that increased in the following order: + 0.7 V pulse (6.2%) < static (8.7%) < − 0.2 V pulse (13.8%).

a Schematic of Ag catalyzed CO2RR under either static or pulsed electrolysis at a given Ec of − 1.1 V vs. RHE but different Ea of − 0.2 or + 0.7 V vs. RHE. b CO2RR products distribution in H-type cell. The error bars represent six independent measurements. Real-time production of (c) H2, (d) CO, and (e) depletion of CO2 observed by DEMS during the three electrolysis methods within 0.1 M CO2-saturated CsHCO3 electrolyte, together with (f) histogram of electric charge normalized mass ion signals. g Simulated 1-D diffusion profiles for surface CO2 concentration and pH as a function of applied voltage and electrolysis duration. All potentials were referenced to the RHE scale. Typical solution resistance in 0.1 M CO2-saturated CsHCO3 is determined as 15 ± 2 Ω and 35 ± 2 Ω for H-type cell and for DEMS flow cell, respectively. The potentials applied were compensated at an 85% level. Source data for this figure are provided in the Source Data file.

Subsequently, online DEMS measurements were conducted on one single Ag/PTFE electrode (see details in Methods, and the relative DEMS flow cell configuration is depicted in Supplementary Fig. 2) to track the gaseous products and the concentration polarization of reactants in real time under applied potential36,38. Figure 1c, d compare the mass ion signals of H2 (m/z = 2) and CO (m/z = 28, deconvoluted)39 under various electrolysis conditions, where the depletion of interfacial CO2 (m/z = 44) is illustrated in Fig. 1e (see details in Supplementary Fig. 3). Noteworthy, the signals for H2 and CO rapidly increase with the applied Ec, then return to baseline upon the application of Ea in each potential cycle, underscoring the high temporal resolution of our DEMS setup, which is capable of capturing transient information. A zoom-in view of these DEMS profiles is presented in Supplementary Fig. 4. Upon prolonged pulsed electrolysis, a gradually decreased H2 but growing CO production rates and the CO2 consumption ratio are noted at tc after + 0.7 V anodic pulses. Overall, at a comparable cathodic current density (Supplementary Fig. 5), the H2 evolution rate decreased in the order of static > − 0.2 V pulsed > + 0.7 V pulsed electrolysis, while the CO2 consumption ratio exhibited the opposite trend, with an increased CO evolution rate following the order of − 0.2 V pulsed <static < + 0.7 V pulsed electrolysis. A discrepancy between the consumed CO2 and the produced CO was noted during − 0.2 V pulsed electrolysis, indicating an additional contribution from the production of involatile formate to the enhanced CO2RR, which aligns well with the quantification results from the H-cell shown in Fig. 1b.

To quantitatively demonstrate the pulsed effect, we further plotted the electric charge-normalized mass ion signals of produced H2, CO, and the averaged CO2 depletion percentage in Fig. 1f. The normalized H2 signal, which is proportional to the averaged H2 production rate, decreased by 24% and 68% when transitioning from static conditions to − 0.2 V and + 0.7 V pulsed electrolysis, respectively. Moreover, the average CO2 consumption decreased from 40.1% to 21.8% and 26.2% upon potential pulsing, largely benefiting from efficient replenishment during ta period. Meanwhile, a 1-D diffusion model was developed using the Nernst-Planck-Poisson equation to investigate the concentration gradient of interested species, arising from diffusion, electromigration, and buffering reactions in the vicinity of the cathode (Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 6). We initially set the diffusion layer thickness as 100 μm to mimic the static electrolysis in the H-cell, which largely reproduced the transient trends observed in previous studies, despite a higher cathodic current density in our case (Supplementary Fig. 7)40. Given the high catholyte flow rate (~ 128 mL min−1) in our DEMS flow cell, a 30 μm diffusion layer model is more appropriate39 and is used hereafter. As shown in Fig. 1g and Supplementary Fig. 8, a steady-state concentration profile can be achieved within ~ 2 s after the potential switch, i.e., cCO2 returning to ~ 33 mM and pH stabilizing near neutral (7.2 ~ 8.0) during the ta period. Compared to static electrolysis, the replenishment of CO2 during Ea pulses could help suppress HER, whereas the slightly heightened local pH in Ec (i.e., below 0.1 unit) plays only a minor role (Supplementary Note 2, Supplementary Figs. 9–11 and Supplementary Table 3). However, the similar concentration polarization profiles between − 0.2 V and + 0.7 V pulsed electrolysis at tc period could not elucidate the enhanced CO evolution and the further suppressed HER in the latter case. Along this line, intuitive interpretations for the predominance of CO2RR over HER at + 0.7 V pulse may include changes in surface adsorbates at different applied potentials and/or the reconstruction of Ag electrodes due to repeated oxidation and reduction cycles. For the former, highly sensitive surface-enhanced vibrational spectroscopy could provide valuable insights (vide infra). For the latter, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 12, a rougher electrode surface morphology is observed for the + 0.7 V pulsed Ag as compared to the − 0.2 V pulsed counterpart. This observation is quantitatively supported by the increase in electrochemical double-layer capacitance from 0.37 mF cm−2 to 0.63 mF cm−2 (Supplementary Fig. 13). In our recent study on plasma-bombarded Ag, we demonstrated that a roughened Ag electrode with a high density of coordination-unsaturated surface sites significantly enhances CO evolution kinetics36. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that the surface reconstruction effect of the roughened Ag electrode is an additional factor, beyond boundary layer conditions, that promotes CO2RR performance41.

The pulse interval is another important parameter that influences the concentration polarization profile and, consequently, the distribution of branching CO2RR products42,43. Here in Supplementary Fig. 14, we compared the DEMS signals of H2, CO, and CO2 recorded over pulse intervals of 5 s, 10 s, and 20 s, while maintaining a constant Ec = − 1.1 V and Ea = + 0.7 V. Noteworthy, the mass ion signals in our DEMS setup returned to baseline within a 10 s period, ensuring real-time detection of product abundance with state-of-the-art temporal response sensitivity. As illustrated on the right side of Fig. 1f, the 10-s interval yields the highest CO to H2 ratio among the three symmetric pulsed electrolysis conditions at the same Ec and Ea. In contrast, the 20-s duration approaches static condition, while the CO2RR performance for the 5-s duration falls between those of the 10-s and 20-s intervals, consistent with previous reports21,33. Subsequently, the optimal pulsed electrolysis conditions of Ea = + 0.7 V, Ec = − 1.1 V, and ta = tc = 10 s were extended to a 2 h continuous DEMS measurement (Supplementary Fig. 15), where the H2 production rate remained below one-third of that observed in static electrolysis, thereby confirming the applicability of this pulsed strategy.

In addition to the aforementioned pulse effect in promoting CO2-to-CO conversion, another puzzle remains regarding the enhanced CO2-to-formate conversion observed at an applied potential of Ea = − 0.2 V. This observation necessitates careful analysis of the potential dependence of CO2 activation configurations on the Ag surface. Therefore, ATR-SEIRAS, which offers high surface sensitivity, has been deployed on an electro-plated Ag film electrode over an Au/Si prism (detailed in Methods) to track the evolution of potential-dependent adsorbates during the 3 electrolysis conditions.

CO adsorption on Ag was first carried out in a CO-saturated 0.1 M CsHCO3 electrolyte, utilizing a negative-going potential sweep from + 0.7 V to − 1.1 V, at a scan rate of 5 mV s−1 and a temporal resolution of 10 s per spectrum. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 16, no surface adsorbates are detected at positive potentials until the emergence of linear adsorbed CO (COL) at ~ 0 V, which coincides with the interfacial water band (δHOH) at ~ 1610 cm−1 observed. At more negative potentials, the COL band gradually redshifts from 2010 to 1950 cm−1 due to the Stark effect (dνCO/dE)44,45, with a maximum band intensity observed near − 0.35 V. Subsequently, COL is progressively replaced by the bridge adsorbed CO species (COB) in the range of 1848 ~ 1774 cm−1. The potential dependence of these two *CO species is further elucidated by the Stark tuning slope, i.e., ca. 58 cm−1/V for COL and 86 cm−1/V for COB (Supplementary Fig. 17).

Figures 2a–c plot the real-time ATR-SEIRA spectra recorded during both static and pulsed CO2RR. A time-resolved band intensity profile and a prolonged 600 s contour plot are comparatively presented in Supplementary Figs. 18 and 19. In all three scenarios, a downward peak at ~ 2340 cm−1 was noted, corresponding to the consumption of interfacial dissolved CO2 species. During static electrolysis at − 1.1 V, only COB at 1760 cm−1 was observed with its band intensity reaching a plateau at ~ 8 s, thus indicating that the 10-s pulse interval is sufficient to establish a stable local reaction environment. In both pulsed electrolysis cases, the interconversion between COB and COL was successfully tracked upon switching the potential between Ec and Ea, where the COL band intensity decreased rapidly at Ea of + 0.7 V, corresponding to the oxidation stripping of *CO at this potential. At Ea = − 0.2 V, a broad shoulder peak ranging from ca. 1650 to 1730 cm−1 was noted, likely arising from the overlapping ν(C = O) stretching vibration features of adsorbed formate and *CO on hollow sites (COH). To shed light on the possible peak assignments, Fig. 2d, Supplementary Fig. 20 and Supplementary Data 1 depict the adsorption configurations and simulated vibrational frequency of different CO2RR intermediates on Ag(111), in comparison to the experimental observations. Though we did not consider the effect of the applied potential in the theoretical calculations for simplicity, the calculated wavenumbers are sufficiently close to the COL and COB bands observed in SEIRAS results. The divergence for COH likely arises from its presence only at large cathodic overpotentials and the lack of accurate Stark tuning slope. Figure 2e and f depict the deconvoluted SEIRA spectra obtained at the same Ec = − 1.1 V but different tc of 188.3 s (the 10th pulse cycle) and 526.7 s (the 27th pulse cycle), respectively, under three distinct electrolysis conditions. A notable peak at ~ 1674 cm−1 was consistently observed for − 0.2 V pulsed condition throughout the extended electrolysis, with its peak intensity significantly exceeding that observed under static or + 0.7 V pulsed electrolysis. Figure 2g compares the SEIRA spectra recorded at 191.6 s (ta period) under anodic conditions, where the intensity of this 1669 cm−1 peak at − 0.2 V even comparable to that of COB. To better address the potential dependence of these adsorbates, we performed grand canonical density functional theory (GC-DFT) calculations to evaluate the Gibbs free energy (∆G) change of CO2 reduction compared to that of H2 evolution on Ag(111) at different potentials (Supplementary Note 3). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 21, ∆G for H2 formation is − 1.35 eV, while that for the formation of monodentate formate species (*OCHOM) is − 0.89 eV at − 1.1 V vs. RHE, indicating that H2 formation is more favorable under this large cathodic overpotential condition. Conversely, a similar ∆G of − 0.54 eV is observed for both reactions at − 0.2 V, suggesting a relatively higher coverage of *OCHOM but lower coverage of *H at − 0.2 V compared to − 1.1 V. Considering this potential-dependent feature, along with the simulated wavenumber and previous reports of *HCOO on Ag(111)46, this suspicious peak at 1670–1680 cm−1 is most likely ascribed to the C = O stretching vibration of monodentate formate. A similar potential-dependent behavior of *OCHOM species has also been observed on the SnO2 electrode during pulsed CO2 electrolysis (Supplementary Note 4), where *OCHOM serves as the active intermediate for CO2-to-formate conversion, aligning well with the pulsed results on the Ag surface (Supplementary Figs. 22–25 and Supplementary Table 4).

a Representative ATR-SEIRA spectra recorded in the first 40 s for static CO2RR at − 1.1 V vs. RHE, and for pulsed electrolysis at (b) Ea = − 0.2 V vs. RHE or (c) Ea = + 0.7 V vs. RHE, where a same Ec = − 1.1 V and a same interval of ta = tc = 10 s have been applied. d Schematic of COL, COB, COH, and OCHOM adsorbates on Ag(111), together with the calculated and observed IR wavenumbers. Detailed atomic coordinates of the adsorbates can be found in Supplementary Data 1. e Deconvoluted IR features at the cathodic period of 188.3 s and (f) 526.7 s, or (g) at the anodic period of 191.6 s. All potentials were referenced to the RHE scale. Typical solution resistance in 0.1 M CO2-saturated CsHCO3 is determined as 58 ± 2.5 Ω for ATR-SEIRAS cell. The potentials applied were compensated at an 85% level. Source data for this figure are provided in the Source Data file.

In a theoretical study on transition metal-catalyzed CO2RR, Studt et al. identified Ag as a promising catalyst for the electroreduction of CO2 to HCOOH with an overpotential of ~ 0.1 V47. However, experimental results indicate that CO is the predominant product in most static electrolysis experiments conducted within a potential window from − 0.6 to − 1.4 V36,48, in which the significant cathodic overpotential may offset the limiting potential for CO2-to-CO conversion on Ag surfaces. Herein, we present, for the first time, direct evidence of enhanced *OCHOM adsorption on the Ag electrode, obtained through a real-time high-sensitivity SEIRAS approach under pulsed electrolysis conditions. This provides a molecular-level insight into the enhanced CO2-to-formate conversion.

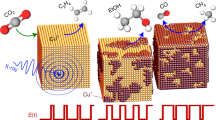

Pulsed electrolysis on Cu

The above results for Ag illustrate the effectiveness of the combined DEMS and ATR-SEIRAS approach in directly capturing transient information regarding both adsorbed intermediates and the local reaction environment. This methodology helps to clarify the underlying promotion mechanism during pulsed CO2RR. In contrast to Ag, Cu exhibits a unique behavior in CO2RR, generating C2+ hydrocarbons and oxygenates through the deep reduction of *CO. This process involves a more complex reaction network at the electrode surface as well as within the boundary layer14.

Similar to the pulsed operation observed at Ag, we applied the same Ec of − 1.1 V to the Cu electrode to mitigate severe mass transport limitation. This was conducted with a symmetric pulse interval of ta = tc = 10 s. Two anodic potentials were considered: − 0.8 V and + 0.6 V, the former corresponds to typical CO accumulation condition21 while the latter is associated with mild oxidation reconstruction of Cu surfaces30,31. Notably, an even higher oxidative anodic potential of + 1.2 V has been reported to enhance the CH4 production over C2+ products, likely due to the exposure of enriched Cuδ+ nanoclusters following surface reconstruction30 and/or the consumption of local OH− species49. Supplementary Fig. 26 illustrates the promotional effect on CO2RR from both pulsed electrolysis conditions, where HER is suppressed from 31% under static conditions to 27% at − 0.8 V pulsed electrolysis and further reduced to ~ 10% at + 0.6 V pulsed conditions. In contrast, CO FE increases from 2.3% (static) to 4.1% (Ea = − 0.8 V) but decreases to 1.4% at Ea = + 0.6 V. The reduction products beyond CO, which involve more than two electrons, increase from 47.9% to 51.0% and 77.8%, respectively. To resolve the puzzle of where and how these CO2RR products get steered in such a complex system, online DEMS and in situ ATR-SEIRAS have been deployed to tackle the characteristic timescales and the potential dependence of key species on Cu.

Figure 3 and Supplementary Fig. 27 compare the total current density and mass ion currents recorded on a Cu/PTFE electrode during either static conditions or 40 consecutive cycles of pulsed electrolysis. Only H2 and CO2 generate exclusive DEMS signals at m/z = 2 (Fig. 3b) and 44 (Supplementary Fig. 27a), respectively. A careful deconvolution protocol has been applied to all other volatile CO2RR products to reflect their respective dynamic generation rate profiles (Fig. 3a–c and Supplementary Fig. 27b–d)39. Supplementary Fig. 28 plots the histogram of electric charge-normalized mass ion signals within 800 s for comparison. Although the total current density jtotal is similar, the average CO2 depletion ratio decreases from 25.4% to 12.6% and 10.9%, accompanied by a decrease in the HER rate of 52% and by 68% from static to pulsed electrolysis with Ea = − 0.8 V and + 0.6 V, respectively, highlighting the beneficial effect of CO2 replenishment in suppressing HER, as observed in the case of Ag. Compared to static conditions, both pulsed electrolysis methods improve the CO2RR rate, in which the CO-accumulated Ea pulses favor C1 products of CO and CH4 (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 28a, b) while the oxidative Ea promotes the C2 products generation like C2H4 and C2H5OH (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 28c). Taking representative C2 and C1 hydrocarbons as examples (Supplementary Fig. 29), the production rate ratio of C2H4 to CH4 increases in the order of − 0.8 V pulsed (ca. 2.25) < static (ca. 2.46) < + 0.6 V pulsed electrolysis (ca. 2.72), which qualitatively in agreement with the determined Faradaic efficiencies in the H-cell despite a higher C2H4 selectivity in DEMS results as arisen from its enhanced mass transport (Supplementary Fig. 30).

a Total current density, the (deconvoluted) mass ion signals for (b) H2, (c) CO, and (d) C2H5OH during the three electrolysis methods within 0.1 M CO2-saturated CsHCO3 electrolyte. e The comparison of normalized H2 and CO2 DEMS signals, together with (f) the comparison of the determined production rate ratio of C2H4 to CH4 under different electrolysis strategies, where the DEMS results after signal calibration agree well with that of GC quantification. All potentials were referenced to the RHE scale. Typical solution resistance for 0.1 M CO2-saturated CsHCO3 DEMS flow cell is 35 ± 2 Ω. The potentials applied were compensated at an 85% level. Source data for this figure are provided in the Source Data file.

ATR-SEIRAS measurements were conducted on one single electro-plated Cu film electrode over an Au/Si prism to track the dynamic evolution of surface adsorbates during CO2RR50. Prior to comparison, we first monitored the SEIRA spectral features during a negative-going potential sweep from − 0.2 to − 1.1 V at a rate of 5 mV s−1 in CO2-saturated 0.1 M CsHCO3. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 31, adsorbed COL from CO2 reduction shows up at ~ − 0.4 V and, thereafter, at frequencies of 2049–2077 cm−1. In the meantime, a minor broad peak is noted between 1700 and 1800 cm−1, likely associated with the COB or *CHO species adsorbed on Cu51. Throughout the potential window of interest, no COL band is detected above 2100 cm−1, suggesting no appreciable exposure of the underlying Au sites (Supplementary Fig. 32)52,53. Figure 4a–c compare the SEIRAS contour plots recorded during the initial 300 s of static, − 0.8 V pulsed, and + 0.6 V pulsed electrolysis (ca. 15 pulse cycles), respectively, with the raw spectra presented in Supplementary Fig. 33 and the total current alongside the integrated COL band intensity shown in Fig. 4d. Under an applied Ec of − 1.1 V, *CO accumulation occurs in the first 2 spectra (~ 3 s), followed by gradual consumption in the subsequent time cycles due to its deep reduction. At the period of ta, Ea = − 0.8 V condition apparently gives rise to the highest *CO coverage despite its relatively lower gaseous CO production rate compared to Ec condition, while *CO is completely oxidized at Ea = + 0.6 V pulse with local CO concentration in the vicinity to cathode dropping to zero. Of particular interest, the 1700–1800-cm−1 band appears only at the cathodic potential of − 1.1 V, and alternates with COL under − 0.8 V pulsed condition (Fig. 4b), thus can be assigned to the C = O stretching mode of *CHO, which serves as the subsequent reduction intermediate of *COL.

a Contour map of SEIRA spectra recorded under static CO2RR at − 1.1 V vs. RHE, or under pulsed electrolysis at (b) Ea = − 0.8 V vs. RHE or (c) Ea = + 0.6 V vs. RHE, where a same Ec = − 1.1 V and a same interval of ta = tc = 10 s have been applied. d Time-course current density, integrated COL band intensity, and CO mass ion currents at different electrolysis conditions. e CO depletion rate in the cathodic pulse of Ea = − 0.8 V and Ea = + 0.6 V. f First-order fitting of the depleted *CO band intensity during cathodic pulses, together with (g) fitted kd of *CO depletion rate constant subject to different pulsed cycles. The shadows represent the 95% confidence bands for directing eyes, where an exponential asymptotic fitting was carried out. h Relative change of the slopes for deconvoluted DEMS signal of representative CO2RR product, detailed time-course evolution can be found in Supplementary Fig. 41 and Supplementary Table 5. All potentials were referenced to the RHE scale. Typical solution resistance for 0.1 M CO2-saturated CsHCO3 in ATR-SEIRA cell is 58 ± 2.5 Ω. The potentials applied were compensated at an 85% level. Source data for this figure are provided in the Source Data file.

Given the vital role of *CO in CO2-to-C2+ conversion, we take a zoom-in view of its dynamic coverage under two pulsed conditions. Figure 4e shows the overall COL depletion profile as derived from its integrated band intensity during the tc period. In this analysis, we observe a gradually increasing COL depletion rate from 0.005 to 0.02 s−1 during the first 100 s of + 0.6 V pulsed electrolysis, whereas a reverse trend decreasing from 0.011 to 0.004 s−1 is noted for the − 0.8 V pulsed condition. In Supplementary Note 5, we conducted a combined DEMS and ATR-SEIRAS study on pulsed CORR over Cu electrode, where a growing COL depletion rate, a lower H2 FE but higher C2H4/CH4 selectivity ratio is noted upon + 0.6 V oxidative pulses as compared to the − 0.5 V CO-accumulative pulsed condition (Supplementary Figs. 34–39). In a recent in situ Raman study on the pulsed CO2RR over Cu, the *CO population (coverage) was suggested as a descriptor for C2+/C1 selectivity22. Herein, by comparing the ν(COL) band intensity in pulsed electrolysis at Ea = − 0.8 V and + 0.6 V, our results demonstrate that the *CO depletion rate, rather than its surface coverage, plays a more important role in determining the selectivity of C2+ products.

Notably, there are three branches following *CO in the CO2RR flowchart54, namely the release into COg, hydrogenation into *CHO, or dimerization into C2+ products as *CO-CHO/*CO-COH55,56. Based on the rate expression for C2+ products generated at a given potential, the jC2+ is proportional to the rate constant kC2+ for C2+ products and to the θCO of *CO surface coverage. Along this line, a further kinetic analysis was carried out to tackle the *CO reactivity under the same Cu film electrode but different Ea pulse conditions. A simple first-order kinetic equation was deployed to evaluate the depletion of *CO:

where A represents the integrated IR band intensity for *COL, kd is the rate constant for *CO depletion53. It is important to note that second-order kinetics fitting was not conducted due to the high energetic barrier associated with direct coupling between two *CO adsorbates56 and its inadequate representation of the C1 pathway toward COg and CH4. As shown in Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 40, a fitting line can be constructed in the semi-logarithmic graph of A*CO-t with the intercept fixed at 0. This is achieved by using the maximum *CO band intensity during a given cathodic pulse as the reference. A significant increase in kd is observed under the + 0.6 V pulsed electrolysis condition, i.e., the *CO depletion rate constant doubles after five repeated cycles, whereas a reverse trend is noted under the − 0.8 V pulsed condition (Fig. 4g). Further kinetic analysis has been applied to the extended pulse cycles, revealing a gradually plateaued kd for both pulsed electrolysis conditions. Notably, the + 0.6 V mild oxidative pulsed condition results in a higher *COL depletion rate compared to the − 0.8 V condition.

Similarly, we conducted an independent analysis of the DEMS data during the initial five pulses to qualitatively correlate the interfacial surface chemistry with the evolution of CO2RR products. For both pulsed conditions, the (deconvoluted) m/z signals were linearly fitted at a given tc and a cathodic potential of − 1.1 V (Supplementary Fig. 41). The statistical results after 5 pulses are illustrated in Fig. 4h and Supplementary Table 5. In response to the doubled kd derived from ATR-SEIRAS, the slopes of representative C2 DEMS signals like C2H4 and C2H5OH increase more rapidly than those for COg and CH4 under Ea = + 0.6 V operation, along with a halved slope for H2. These results confirm the overall suppressed HER while improving the CO2-to-C2+ conversion rate after these successive anodic pulses. In other words, the periodic oxidation and reduction during oxidative pulses not only maintain a favorable local reaction environment for CO2RR of enriched reactant but also generate more undercoordinated Cu surface sites that utilize *CO more efficiently for stable C2+ production (Supplementary Fig. 42)54,57.

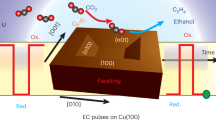

Effects of surface topology and composition

To shed light on the effects of surface restructuring and roughening induced by oxidative pulses31,58,59, atomic force microscopy (AFM) has been employed to characterize the surface roughness of Cu foils. Figure 5a compares the topography images of Cu foil following either 1 h of static electrolysis at −1.1 V or after 2 h of oxidation pulse with Ea = + 0.6 V. Clearly, a more fluctuating Cu surface topology is noticed after the oxidative pulses, demonstrating an increased arithmetic surface roughness factor (Ra) from 3.0 nm to 6.0 nm and qualitatively in good agreement with the SEM images shown in Supplementary Fig. 43. In addition to the enlarged surface area, our previous theoretical analysis suggests that a higher fraction of 4-fold square sites on the roughened Cu surfaces could aid to an enhanced C2+ product generation54. Herein, we carried out Pb underpotential deposition (UPD) on the Cu foil after 20 min of static electrolysis at − 1.1 V or after oxidative pulses lasting either 20 min or 70 min, utilizing an Ar-saturated electrolyte containing 10 mM Pb(ClO4)2 and 0.1 M HClO4. As shown in Fig. 5b, an oxidative stripping peak of the Pb overlayer is found at ~ + 0.02 V, whereas a pair of Pb UPD peaks centered at ~ 0.0 V and − 0.04 V can be deconvoluted for all three electrodes, corresponding to the characteristic cathodic features of Cu(111) and Cu(100) facets, respectively60,61. By integrating the Pb stripping charge, ca. 1.6 ~ 1.7 times enlarged Cu surface area is noted after pulsed electrolysis compared to the static condition, which aligns with the morphological characterization and the double-layer capacitance results (Supplementary Fig. 44). Furthermore, the percentage of Cu(100)-like square sites increases from 15% after 20 min static electrolysis to 26% and 33% after 20 min and 70 min of oxidative pulsed electrolysis, respectively. This two-fold increase in the percentage of surface Cu square sites may account for the enhanced C2+ production rates observed in DEMS and *CO utilization in ATR-SEIRAS under oxidative pulses.

a 3-D AFM image of Cu foil after 1-h static electrolysis at − 1.1 V vs. RHE or after 2-h oxidative pulse with Ea = + 0.6 V vs. RHE. b Pb UPD on Cu foil after 20-min static electrolysis, or after 20 min and 70 min oxidative pulses, using Ar-saturated 10 mM Pb(ClO4)2 + 0.1 M HClO4 electrolyte (pH = 1.0) at a scan rate of 10 mV s−1. c Cu LMM Auger spectra and (d) core-level O 1 s XPS spectra recorded on Cu foil after 70 min static or pulsed electrolysis with Ea = + 0.6 V. All potentials were referenced to the RHE scale. Source data for this figure are provided in the Source Data file.

Figure 5c illustrates the averaged Cu surface state after 70 min of static or pulsed electrolysis, with the core-level Cu 2p spectra plotted in Supplementary Fig. 45 and the O 1 s spectra plotted in Fig. 5d. Clearly, the metallic Cu feature is dominant after static electrolysis at − 1.1 V, whereas an increased proportion of Cu+ sites at ~ 917.4 eV62 can be resolved from the Cu LMM Auger spectra on the electrode subjected to oxidative pulses. In the meantime, the relative content of lattice O centered at ~ 529.8 eV increased from 9.6% on the statically electrolyzed Cu foil to 52.2% on the pulse-electrolyzed foil (Supplementary Table 6), suggesting that the generated Cu2O species during ta period were partially reserved during the 10-s periodic cathodic pulses63. Previous theoretical predictions and X-ray absorption spectroscopic studies indicate that the coexistence of metallic and oxidized Cu surface sites enhances CO production and facilitates CO dimerization to C2+ due to the asymmetry in CO adsorption energies33,64. In short, this observed change in surface composition, together with roughened surface topology and the exposure of more square sites following oxidative pulses, contributes to the overall CO utilization, as revealed by ATR-SEIRAS (Fig. 4).

Discussion

In this work, we illustrate how the square-wave potential in pulsed electrolysis regulates the choreography of mass transport, surface adsorbates, the evolution of electrode topology in the vicinity of the cathode, and the resultant product distribution from the CO2 reduction reaction. Compared to the static electrolysis at a fixed cathodic potential, alternating anodic pulses at more positive potentials replenish the CO2 reactant for the following electrolysis at the cathodic pulse, thus promoting CO2RR over HER for both Ag and Cu electrodes. Furthermore, mild oxidative pulses are found to generate a roughened surface topology with under-coordinated Ag or Cu sites due to periodic oxidation and reduction, delivering the best CO2-to-CO and CO2-to-C2+ conversion performance. On the basis of in situ electrochemical surface-enhanced infrared spectroscopy results, we capture the monodentate formate species on Ag that emerges only after the anodic pulse potential of − 0.2 V near its thermodynamic reduction potential, which is responsible for the enhanced CO2-to-formate conversion. In the case of Cu, we disclose a higher utilization of linear-bonded CO species on the under-coordinated Cu sites following oxidative pulses and rationalize that the *COL depletion rate, rather than surface coverage, should serve as a more accurate descriptor for C2+ selectivity. The findings of this study not only shed light on the mechanism for pulsed CO2 electrolysis but also provide a foundation for understanding the complex interactions at the electrode-electrolyte interface benefiting the broader electrocatalysis community.

Methods

H-type cell measurements

Mechanically polished Ag foil (99.99%, ZhongNuo Advanced Material), electrochemically polished Cu foil (99.9999%, Alfa Aesar), and carbon fiber paper supported commercial SnO2 nanoparticles (Innochem, 99.99%, 50-70 nm) at a catalyst loading of 0.5 mg cm−2 were used as the working electrode in H-cell measurements6. Prior to electrolysis, the SnO2 cathode was pre-reduced at − 0.6 V vs. RHE for 1800 s, the electrode area was fixed at 1 cm−2. Electrochemical CO2RR measurements were performed in a customized gastight H-type glass cell separated by Nafion 117 membrane (Fuel Cell Store). A high-purity graphite rod (99.995%, Aldrich) and a saturated calomel electrode (SCE, CH Instruments) were employed as the counter and reference electrode, respectively. Before each measurement, the reference electrode potential was calibrated by another standard SCE, and the potential error was within 2 mV. Electrochemical responses were recorded on a Biologic VSP-300 potentiostat. The solution resistance (Ru) was determined by potentiostatic electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (PEIS) at frequencies ranging from 0.1 Hz to 200 kHz and manually compensated as E (iR-corrected vs RHE) = E (vs RHE) - Ru×i (amps of averaged current). All potentials (if not specifically mentioned) in this work were converted to the RHE scale as E (vs RHE) = E (vs. SCE) + 0.244 V + 0.0591×pHbulk and E (vs. RHE). Prior to each measurement, 50 sccm CO2 (99.995%, Air Liquide) was purged into pre-purified 0.05 M Cs2CO3 (99.99%, Adamas-Beta) solution for at least 30 min to obtain a 0.1 M CO2-saturated CsHCO3 electrolyte (pH = 6.8 ± 0.01). The electrolyte volume used in both cathodic and anodic chambers was 25 mL.

The effluent from the cathodic chamber was analyzed with a Shimadzu 2014 gas chromatograph equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) for H2 concentration quantification and a flame ionization detector (FID) coupled with a methanizer for quantifying the CO and hydrocarbon concentrations. The signal response of the TCD and FID were calibrated by analyzing a series of standard gas mixture65. The FE of a given reduction product was calculated as follows:

where \({x}_{i}\) is the volume fraction of species i as determined by online GC,\(\,v\) is the flow rate calibrated by a mass flow meter (Alicat), \(n\) is the electron transfer number, F is the Faradaic constant, V is the molar volume of an ideal gas under CO2RR operating conditions, and \(j\) is the total current density.

The liquid products were collected after sufficient coulomb accumulation, 600 μL collected electrolyte of a total 25 mL catholyte was mixed with 100 μL of D2O (Sigma Aldrich, 99.9 wt.% deuterium) and 0.05 μL dimethylsulfoxide (as an internal standard, Sigma Aldrich, 99.9%), then quantified with 1H NMR spectra using a Bruker Avance NEO 400 MHz spectromete65.

Online DEMS measurements

For DEMS measurement, ca. 300 nm Ag or Cu film was sputtered onto PTFE membrane substrate (20 nm pore size, Cobetter) using a Denton sputtering system at a deposition rate of 1 Å/s under a 0.5 Pa Ar atmosphere (99.999%, Air Liquide) and served as working electrode36. Prior to the magnetron sputtering, the hydrophobic PTFE membrane was pre-treated with acetone, methanol, and Milli-Q water (18.2 MΩ·cm) in succession and dried in a stream of flowing N2 (99.999%, Keju Chemistry). The setup of DEMS flow cell consists of a 1.13 cm−2 Ag or Cu sputtered PTFE working electrode, a Pt gauze counter electrode, and a leak-free Ag/AgCl reference electrode (Innovative), where the cathodic and anodic chambers are separated by a Fumasep FAA-PK-130 anion exchange membrane (Supplementary Fig. 2). Before each measurement, the Ag/AgCl reference electrode potential was calibrated by a standard SCE, and the potential error was within 2 mV. Prior to each experiment, the flow cell was sonicated in 20 wt% nitric acid (diluted from 70% concentrated HNO3, AR, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent) and boiled in Milli-Q water for cleaning. 0.05 M Cs2CO3 was used as both catholyte and anolyte with 50 sccm CO2 continually purged during electrolysis, the volume of cathodic and anodic chamber was 0.9 and 0.6 mL, respectively. The electrolyte circulation in each chamber was controlled by an individual peristaltic pump at 128 mL min−1 and forced flow through a 0.8 mm capillary each36,39.

Online DEMS measurements were run on a Hiden HPR-40 quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with a secondary electron multiplier detector. A cage voltage of 4.5 V, an electron energy of 70 eV, and an emission current of 800 μA were set at the ionization source, together with a detector voltage of 1200 V for recording real-time mass spectra. Prior to data acquisition, DEMS background signals were pre-stabilized for 1 h and subtracted from m/z signals for quantitative analysis. The solution resistance (Ru) was compensated in situ at the 85% level by the potentiostat during linear potential sweeps. Unless otherwise indicated, all potentials in DEMS measurement were converted to the RHE scale as E (vs. RHE) = E (vs Ag/AgCl) + 0.197 V + 0.0591 × pHbulk.

ATR-SEIRAS measurements

The preparation procedures of Ag and Cu film working electrodes in ATR-SEIRAS were modified from a two-step wet process, involving the initial chemical deposition of an Au thin film (~ 60 nm) on a hemispherical Si prism followed by the electrodeposition of an Ag or Cu overlayer66. The Ag film was electro-deposited onto an Au/Si prism by holding the potential at 0.5 V vs. RHE for 600 s in 0.1 M HClO4 + 10 mM AgNO3 solution, where the Cu film was electro-deposited at 0.23 V vs. RHE in 5 mM CuSO4 + 50 mM H2SO4 solution until a total charge of 27 C (ca. 150 layers of Cu). The Ag or Cu film-coated Au/Si prism was used as the working electrode, together with an SCE and a graphite rod as the reference and the counter electrode, respectively. ATR-SEIRA spectra were acquired at a resolution of 4 cm−1 with unpolarized IR radiation at an incidence angle of ca. 70° by a Nicolet iS50 FTIR spectrometer with a built-in MCT detector and an in situ IR optical accessory (SPEC-I, Shanghai Yuanfang Tech.). All of the spectra are shown in the absorbance unit as −log (I/I0), where I and I0 represent the intensity of the reflected radiation of the sample and reference spectra, respectively.

Theoretical calculations

Spin-polarized density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (version 5.4.4)67. The revised Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (RPBE) functional and DFT-D3 methods of Grimme et al. were employed68,69. The cutoff energy was set to 450 eV, and the convergence tolerances of energy and force were set to 10−4 eV and 0.05 eV/Å, respectively. We modeled a three-layered (3 × 3) Ag (111) surface, with the bottom-most layer fixed to the bulk positions. 15 Å of a vacuum layer was added along the z-direction. (3 × 3 × 1) Monkhorst-Pack mesh of k-points was sampled70. The vibrational frequencies of adsorbed intermediates were calculated using the finite difference method as implemented in an atomic simulation environment (ASE) with ± 0.005 Å atomic displacements from the optimized structure71.

To maintain the electrode potential during the simulations, we performed grand-canonical DFT (GC-DFT) calculations72. In this approach, we modeled the surface-electrolyte interface as a polarizable continuum using the linearized Poisson-Boltzmann equation, as implemented in VASPsol73. The number of electrons in the system was adjusted to introduce a surface charge and to achieve a target potential. The GC-DFT energy at the applied potential U is calculated as \({{{{\rm{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{GC}}}}-{{{\rm{DFT}}}}}={{{{\rm{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{DFT}}}}}+\Delta {{{\rm{n}}}}\times (4.01+U-{V}_{{bulk}})\), where \(\Delta n\) is the number of electrons added to the charge-neutral system, 4.01 represents the absolute potential versus RHE at pH 6.8, and \({V}_{{bulk}}\) is the electrostatic potential of the bulk electrolyte.

We employed the computational hydrogen electrode (CHE) method to calculate the Gibbs free energy of each reaction at different potentials74. In this method, the Gibbs free energy of the proton and electron pair is derived from half of that of hydrogen gas, and the effect of the applied electrode potential is included, i.e., G(H+ + e−) = 0.5 G(H2) – eU. The Gibbs free energy corrections, including zero-point energy, enthalpic, and entropic contributions, were calculated using the harmonic oscillator and the ideal gas approximation for adsorbates and gas molecules, respectively, at 298.15 K71. Thus, the Gibbs free energy change of the reaction is given by \(\Delta {{{\rm{G}}}}=\,\Delta {{{{\rm{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{GC}}}}-{{{\rm{DFT}}}}}+\,\Delta {{{{\rm{G}}}}}_{{{{\rm{corr}}}}}\). To correct the gas-phase errors originating from the RPBE functional, we added +0.46 eV to the DFT energy of the CO2 molecule75.

Electrode characterizations

The surface morphology images were filmed with a NOVA NanoSEM 230 field-emission scanning electron microscope, using an electron beam energy of 5 kV and a spot size of 3.0 nm. MFP-3D Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) was used to characterize the surface topology and the surface roughness. Near-surface composition of the Cu electrodes was probed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) with a Kratos AXIS Ultra DLD spectrometer, using monochromatic Al Kα radiation (1486.6 eV) and a low energy flood gun as the neutralizer. The Casa XPS program was employed for surface component content analysis, with the binding energies calibrated with reference to the C 1 s peak at 284.8 eV. Pb UPD and oxidative stripping were carried in a gas-tight cell containing Ar-saturated 10 mM Pb(ClO4)2 + 0.1 M HClO4, using a cyclic voltammetry from − 0.11 to + 0.19 V vs. RHE, at a scan rate of 10 mV s−1.

Numerical simulations

The one-dimensional numerical simulations and the transport of species in the cathodic boundary layer were solved using COMSOL Multiphysics 6.0. A synopsis of the modeling details is given in Supplementary Note 1.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information. Source data are provided in this paper.

References

De Luna, P. et al. What would it take for renewably powered electrosynthesis to displace petrochemical processes? Science 364, eaav3506 (2019).

Seh, Z. W. et al. Combining theory and experiment in electrocatalysis: Insights into materials design. Science 355, 6321 (2017).

Stephens, I. E. L. et al. 2022 roadmap on low temperature electrochemical CO2 reduction. J. Phys. Energy 4, 042003 (2022).

Nitopi, S. et al. Progress and perspectives of electrochemical CO2 reduction on copper in aqueous electrolyte. Chem. Rev. 119, 7610–7672 (2019).

Marcandalli, G., Monteiro, M. C. O., Goyal, A. & Koper, M. T. M. Electrolyte effects on CO2 electrochemical reduction to CO. Acc. Chem. Res. 55, 1900–1911 (2022).

Kuhl, K. P., Cave, E. R., Abram, D. N. & Jaramillo, T. F. New insights into the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide on metallic copper surfaces. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 7050–7059 (2012).

Birdja, Y. Y. et al. Advances and challenges in understanding the electrocatalytic conversion of carbon dioxide to fuels. Nat. Energy 4, 732–745 (2019).

Dattila, F., Seemakurthi, R. R., Zhou, Y. & López, N. Modeling operando electrochemical CO2 reduction. Chem. Rev. 122, 11085–11130 (2022).

Wang, G. et al. Electrocatalysis for CO2 conversion: from fundamentals to value-added products. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 4993–5061 (2021).

Fan, L. et al. Strategies in catalysts and electrolyzer design for electrochemical CO2 reduction toward C2 products. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay3111 (2020).

Wang, Y., Liu, J. & Zheng, G. Designing copper‐based catalysts for efficient carbon dioxide electroreduction. Adv. Mater. 33, 2005798 (2021).

Bui, J. C. et al. Engineering catalyst-electrolyte microenvironments to optimize the activity and selectivity for the electrochemical reduction of CO2 on Cu and Ag. Acc. Chem. Res. 55, 484–494 (2022).

Malkani, A. et al. Understanding the electric and nonelectric field components of the cation effect on the electrochemical CO reduction reaction. Sci. Adv. 6, eabd2569 (2020).

Zhang, G., Ye, K., Ni, B. & Jiang, K. Steering the products distribution of CO2 electrolysis: A perspective on extrinsic tuning knobs. Chem. Catal. 3, 100746 (2023).

Xu, A., Govindarajan, N., Kastlunger, G., Vijay, S. & Chan, K. Theories for electrolyte effects in CO2 electroreduction. Acc. Chem. Res. 55, 495–503 (2022).

Kim, C. et al. Tailored catalyst microenvironments for CO2 electroreduction to multicarbon products on copper using bilayer ionomer coatings. Nat. Energy 6, 1026–1034 (2021).

Xu, Z., Xie, Y. & Wang, Y. Pause electrolysis for acidic CO2 reduction on 3-dimensional Cu. Mater. Rep. Energy 3, 100173 (2023).

Kedzierzawski, P. & Augustynski, J. Poisoning and activation of the gold cathode during electroreduction of CO2. J. Electrochem. Soc. 141, L58 (1994).

Shiratsuchi, R. & Nogami, G. Pulsed electroreduction of CO2 on silver electrodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 143, 582 (1996).

Woldu, A. R. et al. Insights into electrochemical CO2 reduction on SnS2: Main product switch from hydrogen to formate by pulsed potential electrolysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202301621 (2023).

Kim, C., Weng, L.-C. & Bell, A. T. Impact of pulsed electrochemical reduction of CO2 on the formation of C2+ products over Cu. ACS Catal. 10, 12403–12413 (2020).

Li, Z., Wang, L., Wang, T., Sun, L. & Yang, W. Steering the dynamics of reaction intermediates and catalyst surface during electrochemical pulsed CO2 reduction for enhanced C2+ selectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 20655–20664 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Customizing CO2 electroreduction by pulse-induced anion enrichment. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 26213–26221 (2023).

Wasmus, S., Cattaneo, E. & Vielstich, W. Reduction of carbon dioxide to methane and ethene—an on-line MS study with rotating electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 35, 771–775 (1990).

Casebolt, R., Levine, K., Suntivich, J. & Hanrath, T. Pulse check: Potential opportunities in pulsed electrochemical CO2 reduction. Joule 5, 1987–2026 (2021).

Lee, J. & Tak, Y. Electrocatalytic activity of Cu electrode in electroreduction of CO2. Electrochim. Acta 46, 3015–3022 (2001).

Kimura, K. W. et al. Selective electrochemical CO2 reduction during pulsed potential stems from dynamic interface. ACS Catal. 10, 8632–8639 (2020).

Casebolt DiDomenico, R. et al. Pulsing the applied potential in electrochemical CO2 reduction enhances the C2 activity by modulating the dynamic competitive binding of *CO and *H. ACS Catal. 14, 785–796 (2024).

Herzog, A. et al. Operando raman spectroscopy uncovers hydroxide and CO species enhance ethanol selectivity during pulsed CO2 electroreduction. Nat. Commun. 15, 3986 (2024).

Zhang, X.-D. et al. Asymmetric low-frequency pulsed strategy enables ultralong CO2 reduction stability and controllable product selectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 2195–2206 (2023).

Arán-Ais, R. M., Scholten, F., Kunze, S., Rizo, R. & Roldan Cuenya, B. The role of in situ generated morphological motifs and Cu(i) species in C2+ product selectivity during CO2 pulsed electroreduction. Nat. Energy 5, 317–325 (2020).

Chang, C.-J. et al. Lewis acidic support boosts C–C coupling in the pulsed electrochemical CO2 reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 6953–6965 (2023).

Timoshenko, J. et al. Steering the structure and selectivity of CO2 electroreduction catalysts by potential pulses. Nat. Catal. 5, 259–267 (2022).

Xu, L. et al. Identifying the optimal oxidation state of Cu for electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 to C2+ products. Green. Chem. 25, 1326–1331 (2023).

de Ruiter, J. et al. Probing the dynamics of low-overpotential CO2-to-CO activation on copper electrodes with time-resolved Raman spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 15047–15058 (2022).

Ye, K. et al. Resolving local reaction environment toward an optimized CO2-to-CO conversion performance. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 749–759 (2022).

Hans, M., Mathews, S., Mücklich, F. & Solioz, M. Physicochemical properties of copper important for its antibacterial activity and development of a unified model. Biointerphases 11, 018902 (2015).

Clark, E. L. & Bell, A. T. Direct observation of the local reaction environment during the electrochemical reduction of CO2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 7012–7020 (2018).

Ye, K. et al. Steering CO2 electrolysis selectivity by modulating the local reaction environment: An online DEMS approach for Cu electrodes. eScience 3, 100143 (2023).

Gupta, N., Gattrell, M. & MacDougall, B. Calculation for the cathode surface concentrations in the electrochemical reduction of CO2 in KHCO3 solutions. J. Appl. Electrochem. 36, 161–172 (2005).

Ma, M., Trzesniewski, B. J., Xie, J. & Smith, W. A. Selective and efficient reduction of carbon dioxide to carbon monoxide on oxide-derived nanostructured silver electrocatalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 9748–9752 (2016).

Kumar, B. et al. Controlling the product syngas H2:CO Ratio through pulsed-bias electrochemical reduction of CO2 on copper. ACS Catal. 6, 4739–4745 (2016).

Bui, J. C., Kim, C., Weber, A. Z. & Bell, A. T. Dynamic boundary layer simulation of pulsed CO2 electrolysis on a copper catalyst. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 1181–1188 (2021).

Chang, S. C. & Weaver, M. J. Coverage‐dependent dipole coupling for carbon monoxide adsorbed at ordered platinum(111)‐aqueous interfaces: Structural and electrochemical implications. J. Chem. Phys. 92, 4582–4594 (1990).

Jiang, K. et al. Local coordination and reactivity of a Pt single-atom catalyst as probed by spectroelectrochemical and computational approaches. CCS Chem. 3, 241–251 (2021).

Sim, W. S., Gardner, P. & King, D. A. Multiple bonding configurations of adsorbed formate on Ag{111}. J. Phys. Chem. C. 100, 12509–12516 (1996).

Yoo, J. S., Christensen, R., Vegge, T., Nørskov, J. K. & Studt, F. Theoretical insight into the trends that guide the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide to formic acid. ChemSusChem 9, 358–363 (2015).

Hatsukade, T., Kuhl, K. P., Cave, E. R., Abram, D. N. & Jaramillo, T. F. Insights into the electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 on metallic silver surfaces. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 13814–13819 (2014).

Jeon, H. S. et al. Selectivity control of Cu nanocrystals in a gas-fed flow cell through CO2 pulsed electroreduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 7578–7587 (2021).

Li, H. et al. Changing the product selectivity for electrocatalysis of CO2 reduction reaction on plated Cu electrodes. ChemCatChem 11, 6139–6146 (2019).

Zhu, S., Li, T., Cai, W.-B. & Shao, M. CO2 Electrochemical reduction as probed through infrared spectroscopy. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 682–689 (2019).

Dunwell, M. et al. The central role of bicarbonate in the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide on gold. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 3774–3783 (2017).

Tao, Z., Pearce, A. J., Mayer, J. M. & Wang, H. Bridge sites of Au surfaces are active for electrocatalytic CO2 reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 8641–8648 (2022).

Jiang, K. et al. Effects of surface roughness on the electrochemical reduction of CO2 over Cu. ACS Energy Lett. 5, 1206–1214 (2020).

Garza, A. J., Bell, A. T. & Head-Gordon, M. Mechanism of CO2 reduction at copper surfaces: Pathways to C2 products. ACS Catal. 8, 1490–1499 (2018).

Liu, X. et al. pH effects on the electrochemical reduction of CO2 towards C2 products on stepped copper. Nat. Commun. 10, 32 (2019).

Gao, W. et al. CO Binding energy is an incomplete descriptor of Cu-based catalysts for the electrochemical CO2 reduction reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202313798 (2023).

Lai, W. et al. Dynamic evolution of active sites in electrocatalytic CO2 reduction reaction: Fundamental understanding and recent progress. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2111193 (2022).

Amirbeigiarab, R. et al. Atomic-scale surface restructuring of copper electrodes under CO2 electroreduction conditions. Nat. Catal. 6, 837–846 (2023).

Brisard, G. M., Zenati, E., Gasteiger, H. A., Markovic, N. M. & Ross, P. N. Underpotential deposition of lead on copper(111): A study using a single-crystal rotating ring disk electrode and ex situ low-energy electron diffraction and scanning tunneling microscopy. Langmuir 11, 2221–2230 (1995).

Sebastián-Pascual, P. & Escudero-Escribano, M. Surface characterization of copper electrocatalysts by lead underpotential deposition. J. Electroanal. Chem. 896, 115446 (2021).

Biesinger, M. C. Advanced analysis of copper X‐ray photoelectron spectra. Surf. Interface Anal. 49, 1325–1334 (2017).

Liu, W. et al. Electrochemical CO2 reduction to ethylene by ultrathin CuO nanoplate arrays. Nat. Commun. 13, 1877 (2022).

Xiao, H., Goddard, W. A., Cheng, T. & Liu, Y. Cu metal embedded in oxidized matrix catalyst to promote CO2 activation and CO dimerization for electrochemical reduction of CO2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 6685–6688 (2017).

Zhang, G. et al. Electrifying HCOOH synthesis from CO2 building blocks over Cu-Bi nanorod arrays. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2400898121 (2024).

Ma, X.-Y., Zhang, W.-Y., Ye, K., Jiang, K. & Cai, W.-B. Electrolyte-layer-tunable ATR-SEIRAS for simultaneous detection of adsorbed and dissolved species in electrochemistry. Anal. Chem. 94, 11337–11344 (2022).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comp. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Hammer, B., Hansen, L. B. & Nørskov, J. K. Improved adsorption energetics within density-functional theory using revised Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof functionals. Phys. Rev. B 59, 7413–7421 (1999).

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S. & Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1456–1465 (2011).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Hjorth Larsen, A. et al. The atomic simulation environment-a Python library for working with atoms. J. Phys. Condens. Mat. 29, 273002 (2017).

Kim, J. et al. Vitamin C-induced CO2 capture enables high-rate ethylene production in CO2 electroreduction. Nat. Commun. 15, 192 (2024).

Mathew, K., Kolluru, V. S. C., Mula, S., Steinmann, S. N. & Hennig, R. G. Implicit self-consistent electrolyte model in plane-wave density-functional theory. J. Chem. Phys. 151, 234101 (2019).

Nørskov, J. K. et al. Origin of the overpotential for oxygen reduction at a fuel-cell cathode. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 17886–17892 (2004).

Granda-Marulanda, L. P. et al. A semiempirical method to detect and correct DFT-based gas-phase errors and its application in electrocatalysis. ACS Catal. 10, 6900–6907 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFB4102000, 2022YFA1505100, 2022YFA1503803), the NSFC (22472038, 22002088, 51972223), and the Shanghai Science and Technology Innovation Action Plan (22dz1205500). S.B. acknowledges the support from the Nano & Material Technology Development Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by Ministry of Science and ICT (RS-2024-00406517, RS-2024-00448287). The authors would like to thank Dr. Peng Li at Wuhan University and Dr. Meng Lin at SUSTech for fruitful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.J. conceptualized the project. K.Y., T.W.J., and K.J. developed and conducted electrochemical tests and related data processing. K.Y. performed materials characterization with the help of P.S., Z.W. H.D.J., S.J., and S.B. carried out DFT calculations. All authors discussed the results and commented on the paper. K.J., W.B.C., and S.B. supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Zhi-Yuan Gu, Chanyeon Kim, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ye, K., Jiang, TW., Jung, H.D. et al. Molecular level insights on the pulsed electrochemical CO2 reduction. Nat Commun 15, 9781 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54122-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54122-3

This article is cited by

-

Pulsed Dynamic Water Electrolysis: Mass Transfer Enhancement, Microenvironment Regulation, and Hydrogen Production Optimization

Nano-Micro Letters (2026)

-

AI‑driven photonic noses: from conventional sensors to cloud‑to-edge intelligent microsystems

Microsystems & Nanoengineering (2025)

-

Identifying Cu reconstruction mechanism in CO2 and CO electroreduction via Cu+ detection and in situ atomic force microscopy

Science China Materials (2025)

-

Membrane-separated differential electrochemical mass spectrometry enables long-term gas evolution analysis in volatile-electrolyte batteries

Science China Chemistry (2025)