Abstract

Single-atom skeletal editing is an increasingly powerful tool for scaffold hopping-based drug discovery. However, the insertion of a functionalized carbon atom into heteroarenes remains rare, especially when performed in complex chemical settings. Despite more than a century of research, Ciamician-Dennstedt (C-D) rearrangement remains limited to halocarbene precursors. Herein, we report a general methodology for the Ciamician-Dennstedt reaction using α-halogen-free carbenes generated in situ from N-triftosylhydrazones. This one-pot, two-step protocol enables the insertion of various carbenes, including those previously unexplored in C-D skeletal editing chemistry, into indoles/pyrroles scaffolds to access 3-functionalized quinolines/pyridines. Mechanistic studies reveal a pathway involving the intermediacy of a 1,4-dihydroquinoline intermediate, which could undergo oxidative aromatization or defluorinative aromatization to form different carbon-atom insertion products.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The concept of “scaffold-hopping”, which aims to identify isofunctional structures with distinct molecular cores that enhance bioactivity and also access new intellectual property space, has recently emerged as an important, enabling strategy in drug discovery1,2. One of the most desirable contexts of this powerful concept is heterocycle replacement, as demonstrated by the successful development of the cholesterol-lowering drug pitavastatin from fluvastatin, and the antineoplastic agent alimta from 5,10-dideazafolic acid (Fig. 1a)3,4. However, the execution of this strategy in molecular optimization campaigns has proven to be time-consuming and labor-intensive due to the distinct preparative methods required for the different heterocyclic cores. As such, synthetic and medicinal chemists are particularly attracted by the direct heterocycle-to-heterocycle transmutation through the insertion or deletion of single atoms from the heterocyclic core of a given active pharmaceutical ingredient5,6,7,8. Within this field, significant advances have been made in single-atom skeletal editing of aliphatic heterocycles9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. However, the successful execution of this concept in the setting of heteroaromatic scaffolds is much more challenging18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26, owing to the high energy barriers encountered during the initial dearomatization processes required for single-atom insertion, which in turn can impose limitations on the range of insertion reagents or reaction conditions26,27.

One of the seminal examples of the single-atom skeletal editing is the Ciamician–Dennstedt (C-D) reaction, in which pyrroles are converted into 3-chloropyridines via the formal insertion of chloroform-derived dichlorocarbene28. Despite their retrosynthetic simplicity in complex molecule synthesis, this method suffered from notable limitations, including harsh reaction conditions and poor yields29. In recent years, Levin, Ball, Xu, and others have made significant contributions to the evolution of this chemistry30,31,32,33,34,35,36. To date, the C-D reactions have been achieved through free carbenes generated from thermally- or photo-activated halocarbene sources (e.g., chloroform28, CCl3CO2Na29, α-chlorodiazirines30,31, dibromofluoromethanes31,32) and metal carbenes by rhodium- and enzyme-catalyzed decomposition of α-halodiazoacetates34,35,36. These C-D reactions proceed via a halocyclopropanation and aromatization-promoted 2π-electrocyclic ring opening sequence. Mechanistically, the expulsion of halide ion in the course of ring expansion is critical to ensure selective ring expansion over C–H functionalization37 (Fig. 1b). As a result, only specially designed halocarbene precursors can be successfully employed in these one-carbon insertions, which limits the functionality installed on the ring-expansion products to halogens, esters, aryl, and heteroaryl groups and prevents their widespread adoption in late-stage skeletal modifications of complex targets. Very recently, we have developed a couple of skeletal editing of N-heteroarenes through dearomative carbon atom insertion, accessing N-heterocycles bearing a quaternary carbon center by trapping of a disubstituted carbenes generated from fluoroalkyl N-triftosylhydrazones25,38,39. We wondered whether this strategy would be applicable in C-D reactions using leaving group-free carbenes; if successful, would considerably expande accessible chemical space of this skeletal editing technique, especially late-stage editing of complex molecules.

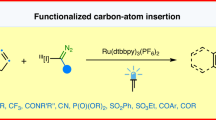

In this work, we present a general and broadly applicable α-halogencarbene-free C-D reaction of indoles and pyrroles, accessing the corresponding 3-functionalized quinolines and pyridines by trapping of a carbene species generated from N-triftosylhydrazones (Fig. 1c). Due to the structural diversity of N-triftosylhydrazones,40,41,42 this leaving group-free C-D reaction allows for the direct introduction of a wide range of functional groups, with indoles and pyrroles converted into 3- functionalized quinolines and pyridines, which are well-known privileged structural elements in drug and agrochemical development.43,44

Results

Reaction optimization

Given the prominence of fluoroalkyl groups in drug and agrochemical development45,46, we first directed our attention to the insertion of fluoroalkylated carbon atoms into indoles, which would offer facile access to 3-fluoroalkylated quinolines. After optimizing various reaction parameters, we found that the reaction of N-TBS-indole 1 with 1.2 equiv. of trifluoroacetaldehyde N-triftosylhydrazone (TFHZ-Tfs, 2)47 in the presence of NaH and TpBr3Cu(CH3CN) (10 mol%) in trifluoromethyl toluene (PhCF3) at 60 °C afforded cyclopropane intermediate 3′ in 94% yield (Supplementary Table 1). Subsequent treatment of the intermediate 3′ without purification with TBAF and DDQ in THF at 25 °C afforded 3-(trifluoromethyl)quinoline 3 in 86% isolated yield (Supplementary Table 1).

Skeletal editing using fluoroalkyl N-triftosylhydrazones

We next explored the scope of this one-pot, two-step skeletal ring expansion reaction of indoles with fluoroalkyl N-triftosylhydrazones. As shown in Fig. 2a, a range of N-TBS-indoles bearing electron-donating or electron-withdrawing substituents at the 4-, 5-, 6-, or 7-positions afforded the corresponding 3-trifluoromethyl quinolines in good to excellent yields (5–22). Many functional groups, such as methyl (5–8), ester (9), acetyl (10), halogens (11, 18, 19, 21, and 22), ethers (12, 16, and 20), protected amine (13), phenyl (14), pyridine (15), and phenylethynyl (17) were well tolerated, although electron-donating substituents gave slightly lower yields (e.g., 5–8, 12, 13, and 20). In contrast to the moderate electronic influence, steric factors play a crucial role in this reaction. For example, the sterically hindered 3-methyl or 3-phenyl TBS-indole displayed much lower yield (i.e., 20% for product 4), and no ring-expansion products were observed when subjecting 2-substituted indoles to the standard reaction conditions (Supplementary Fig. 1). Furthermore, a bioactive natural product, raputimonoindole B, as well as indoles derived from naturally occurring terpenes geraniol and perillyl alcohol, underwent smooth insertion to afford their corresponding quinoline homologs (23–25). In addition to trifluoroacetaldehyde N-triftosylhydrazone (TFHZ-Tfs), difluoroacetaldehyde N-triftosylhydrazone (DFHZ-Tfs)48 could also be used in our ring expansion protocol, affording 3-difluoromethylated quinolines (26–33) in high yields and with excellent chemoselectivity. Aside from indoles, the reaction of 7-azaindole with TFHZ-Tfs or DFHZ-Tfs also performed well to afford the corresponding ring expansion products 34 and 35. Overall, this fluoroalkylative ring expansion exhibits high chemoselectivity, with no competing [2 + 1] cycloaddition (16, 17, 24, 25, and 33), N−H insertion (13) and benzylic or allylic C−H insertion (20 and 30) products found in the presence of copper carbene.

a Direct carbon-atom insertion of indoles with fluoroalkyl carbenes. Conditions A: indole (0.3 mmol), TFHZ-Tfs (0.36 mmol), TpBr3Cu(CH3CN) (10 mol%), NaH (0.72 mmol) in PhCF3 at 60 °C under N2 for 12 h. Conditions B: indole (0.3 mmol), DFHZ-Tfs (0.6 mmol), TpBr3Cu(CH3CN) (10 mol%), Cs2CO3 (1.8 mmol) in DCM at 40 °C under N2 for 24 h. b Defluorinative carbon-atom insertion of indoles with fluoroalkyl carbenes. Conditions C: indole (0.3 mmol), N-triftosylhydrazone (0.6 mmol), TpBr3Cu(CH3CN) (10 mol%), NaH (1.8 mmol) in PhCF3 at 60 °C under N2 for 12 h. Isolated yields.

We then investigated the reactivity of perfluoroalkyl N-triftosylhydrazones. Under standard conditions, the reaction of N-TBS-indole with pentafluoroethyl N-triftosylhydrazone produced the expected ring expansion product 36 in 60% yield along with ~20% of a hydrodefluorinative ring expansion product 37. Intrigued by the formation of 37, we re-optimized the reaction conditions to favor the formation of this hydrodefluorination product (Supplementary Table 4). Gratifyingly, we obtained 37 in 98% yield in the presence of cesium fluoride (CsF) in H2O/DMSO under air at 25 °C. As shown in Fig. 2b, a wide variety of structurally diverse indoles with various functionalities readily underwent this modified ring-expansion reaction, affording 3-fluoroalkylated quinoline products (38–48) in moderate to good yields, and could be extended to azaindole (49). We found that longer-chain perfluoroalkyl N-triftosylhydrazones were also compatible with the transformation, producing the corresponding functionalized carbon-atom insertion products (50–55) in high yields, in which the fluorine atom at the α-carbon of the hydrazone chain underwent selective defluorination.

Surprisingly, we found that the outcome of this reaction could be further tuned by treating the cyclopropane intermediate under identical conditions (CsF/H2O/DMSO under air) at 40 °C instead of 25 °C, which led to the formation of quinoline-3-carboxaldehyde (56) in 78% yield (see Supplementary Table 5). This unexpected defluorinative formylation affords a formal carbonylative insertion product, and proved to be quite general, with an array of electronically differentiated indoles being compatible with these reaction conditions. In all cases, the corresponding quinoline-3-carboxaldehyde products (57–67) were obtained in high yields. Remarkably, indoles derived from naturally occurring terpenes such as geraniol and perillyl alcohol were also smoothly transformed into their corresponding quinoline-3-carboxaldehyde analogs 68 and 69 respectively, despite containing potentially vulnerable ester and alkene functionalities.

Skeletal editing using functionalized N-triftosylhydrazones

We recognized that the value of this chemistry would be significantly enhanced if other hydrazones could be applied, and turned our attention to the synthesis of 3-arylquinolines using aryl and heteroaryl aldehyde-derived N-triftosylhydrazones as carbene precursors. While the reaction of N-TBS-indole with 4-tolyl N-triftosylhydrazone under the previously optimized conditions delivered the desired ring expansion product 70 in only 20% yield, after significant re-optimization, we were delighted to discover that TpBr3Ag(thf) as the catalyst improved this yield to 97% (Fig. 3a, see Supplementary Table 6 for details). Under these new conditions, a wide variety of electronically differentiated aryl N-triftosylhydrazones were successfully inserted, with tolerance of functionalities such as phenyl, naphthyl, trifluoromethyl, trifluoromethoxy, halogens, and ethers (71–80). The practicality of our protocol was demonstrated by the gram-scale synthesis of 70. The extension of this method to N-triftosylhydrazones bearing a fused or hetero aromatic ring would be of great significance for drug discovery. We found that this was indeed possible, with furan, benzofuran, benzothiophene, thiophene, and pyridine substituents all successfully introduced into the ring expansion products (81–86). We could further expand the scope of N-triftosylhydrazone substituents to alkyl, alkene, and even alkyne groups; these insertions also proceeded smoothly, producing the corresponding 3-alkyl-, alkenyl-, and alkynyl-quinolines (87–92) in good to excellent yields, which were challenging to access with previous approaches using α-chlorodiazirines as one-carbon source30,31. The incorporation of these unsaturated moieties provides valuable functional handles for additional downstream synthetic transformations.

a Functionalized carbon-atom insertion of indoles. Reaction conditions: N-triftosylhydrazone (0.3 mmol), N-TBS indole (0.6 mmol), NaH (0.6 mmol) and TpBr3Ag(thf) (10 mol%) in PhCF3 (10 mL) at 60 °C under N2 for 12 h then TBAF (0.75 mmol) at 25 °C under air for 10 min. b One-carbon insertion of pyrroles. Reaction conditions: N-triftosylhydrazone (0.3 mmol), 1H-pyrrole (0.6 mmol), NaH (0.6 mmol) and Rh2(esp)2 (1 mol%) in PhCF3 (5 mL) at 60 °C under N2 for 12 h. Isolated yields. Rh2(esp)2, Bis[rhodium(α,α,α′,α′-tetramethyl-1,3-benzenedipropionic acid). a80 °C. bCsF/DMSO instead of TBAF. cThe OH group in indole or N-triftosylhydrazone was protected by TBS and deprotected in the reaction conditions. dDCM instead of PhCF3. eCsF/DMF instead of TBAF. f1 mol% Rh2(esp)2. gN-triftosylhydrazone derived from 3-(triisopropylsilyl)propiolaldehyde.

Having established the broad scope of the N-triftosylhydrazone partners that can be employed in this chemistry, we then turned our attention to the indole substrate. To our delight, using 4-tolyl N-triftosylhydrazone as the carbene precursor, indoles adorned with bromo, nitro, ester, pyridine, allyloxy, protected amine, phenyl, halogen, methoxy, cyano, and acetal functionalities at different positions of indole scaffold proved successful, affording the corresponding 3-arylquinolines (93–106) in moderate to excellent yields. Interestingly, the OTBS (tert-butyldimethylsilyloxy) group can be tolerated in the first step but is hydrolyzed to the hydroxyl group in the second step, thereby providing a practical route to access hydroxyl-containing bioactive compounds (vide infra). In addition, 7-azaindole and 5-chloro-7-azaindole, which had not previously been demonstrated30,31,32,33,34,35,36, produced the corresponding ring expansion products (109 and 110). We also applied this silver-catalyzed ring-expansion protocol to the late-stage modification of bioactive indoles such as tryptophol, melatonin, raputimonoindole B, and verticillatine B, providing respective ring-expansion products 111–114 in moderate yields. Important drug intermediates (e.g., pindolol) or indoles derived from steroids (e.g., pregnenolone) and terpenes (e.g., perillyl alcohol and geraniol) also proved to be good substrates, affording their 3-aryl quinoline analogs 115–118. Notably, the sterically hindered 2- and 3-substituted indoles that are not amenable to the fluoroalkylative expansion, have undergone arylative ring expansion with synthetically meaningful yields (e.g., 107, 108, 111, and 112).

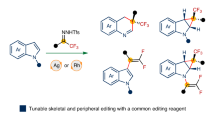

Of high importance in molecular editing is the ability to apply a single reaction to multiple heterocyclic cores. As such, we next sought to expand our protocol to pyrroles to access pyridines. Unfortunately, under similar conditions, N-TBS-protected pyrrole failed to afford the desired ring-expansion product (entries 1–3, Supplementary Table 7), which is consistent with previous observations that C–H insertion is favored over C=C cyclopropanation when electron-donating group-protected pyrroles react with copper or silver carbene49. Inspired by the work of the Levin group, we turned our attention to 1H-pyrrole and were delighted to find that 1H-pyrrole could afford carbon insertion product 119 in 48% yield when using Rh2(esp)2 as a catalyst (Supplementary Table 7). With suitable modified editing conditions established, we first investigated the range of N-triftosylhydrazone coupling partners that could be used. As shown in Fig. 3b, we found that a variety of mono- and di-substituted aryl N-triftosylhydrazones bearing trifluoromethyl, fluoro, ester, methyl, and chloro substituents directly afforded the corresponding 3-aryl pyridines (120–125). Unfortunately, other types of N-triftosylhydrazones, such as trifluoromethyl-, perfluoroalkyl-, alkyl-, alkenyl- and alkynyl-substituted N-triftosylhydrazones, are not suitable carbene precursors, representing a current limitation of the reaction (Supplementary Fig. 2). A brief survey of pyrrole scope revealed that 2-(trichloroacetyl)-1H-pyrrole provided 2-(dichloroacetyl)pyridine 126 in 59% yield, while 3-methyl-1H-pyrrole resulted in a 4:3 mixture of regioisomeric ring expansion products 127 and 128, in 56% total yield.

3-Aryl quinolines are common motifs in pharmaceutically interesting compounds, although their construction typically requires multiple steps. To further demonstrate the utility of the ring-editing protocol, we have targeted the streamlined synthesis of bioactive quinolines of medicinal interest (Fig. 4). One advantage of this protocol is that OTBS-substituted indoles could directly provide OH-containing quinoline derivatives. Taking advantage of this, we successfully synthesized potential anticancer agents50 131 and 132 from commercially available indole 129 in two steps with 72% and 49% total yields, respectively (Fig. 4a). This protocol has better tolerance for arylcarbenes with strong electron-donating groups compared to previous protocols using α-chlorodiazirines as the one-carbon source30,31. For example, 3-(4-methoxyphenyl)quinoline-2-carbaldehyde 134, a key intermediary for the synthesis of pharmaceuticals with antiproliferative (136) and anti-dengue activity (137), can be obtained in two steps from 2-methylindole 134 with an overall yield of 62% (Fig. 4b). Notably, the compound 134 was previously prepared from isatin 136 in three steps, with 53% overall yield51. Applying this silver-catalyzed C-D protocol, electron-rich aryl-substituted quinoline derivatives 138, 140, and 142 can be obtained in 90%, 81%, and 89% yields, respectively. These compounds can be further transformed into bioactive molecules, such as anti-inflammatory compound 13952, β-glucuronidase inhibitor 14153 and antimycobacterial treatment adjuvant 14354, in two steps with preparatively useful total yields (Fig. 4c). Finally, the Buchwald-Hartwig amination of product 144, which was obtained by one-carbon insertion in 88% yield, with morpholine afforded quinoline 145 in 80% yield, which is used for the treatment of hypopharyngeal cancer55.

Mechanistic investigations

To gain insight into the mechanism of the halogencarbene-free C-D reaction, we performed a series of experiments to study the reaction pathway for the formation of the various products. First, resubjection 3-(difluoromethyl)quinoline 29 to the standard conditions for TBS deprotection (CsF/H2O/DMSO) did not yield any aldehyde 62, ruling out the possibility of difluoromethyl hydrolysis to the aldehyde (Supplementary Fig. 5). Second, we were able to isolate trifluoromethyl cyclopropane 146 as a single diastereomer from the reaction of ester-substituted indole with TFHZ-Tfs (2) (Supplementary Fig. 6). Subsequent treatment of cyclopropane 146 with CsF in DMSO/H2O under a nitrogen atmosphere at room temperature for 10 min gave a mixture of 147 and 148 in a ~1:1 ratio (82% yield). When these products were exposed to additional CsF and water under air at 40 °C, formal formylation product 62 was obtained in 80% yield (Fig. 5a), suggesting both 1,4-dihydroquinoline 147 and 3,4-dihydroquinoline 148 are the key intermediates in the formation of the aldehyde product.

a Identification of the reaction intermediates. b Experiments to probe the source of the hydrogen atom incorporated in quinoline-3-carboxaldehyde. c Experiment to validate the process of imine-enamine tautomerization. d Probing source of oxygen atom incorporated into quinoline-3-carboxaldehyde. e Proposed reaction pathways for one-carbon insertion of indoles with fluoroalkyl carbenes.

We then performed a series of deuterium labeling studies. Treatment of the deuterated cyclopropane 146-d with TBAF at −60 °C for 10 min resulted in the formation of the mono-deuterated 1,4-dihydroquinoline 147-d1 (90% D incorporation), which was further converted into the deuterated product 62-d with 20% D incorporation at the carbonyl carbon and 70% D retention at the C4-position. This result suggests that deuterium atoms in 146-d1 are perfectly retained in 62-d and hydrogen atoms transfer to carbonyl carbon preferentially over deuterium atoms. Bis-deuterated 1,4-dihydroquinoline 147-d2 (65% D incorporation) was isolated in 92% yield by treating 146-d with TBAF/D2O at −60 °C for 10 min. The cross-over experiment of deuterated 147-d2 and non-deuterated 149 afforded bis-deuterated compound 62-d and non-deuterated 56-d (Fig. 5b). Furthermore, D incorporation at carbonyl carbon was improved to 74% when using bis-deuterated 1,4-dihydroquinoline with 80% D incorporation (Supplementary Fig. 8). These results indicate that the aldehyde hydrogen in 56 may derive from the C4-H of the 1,4-dihydroquinoline intermediate, and proceed through a formal intramolecular 1,3-hydrogen shift. Interestingly, treatment of deuterated cyclopropane 150-d with TBAF in THF at 25 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere afforded the deuterated 1,4-dihydroquinoline 151 in NMR 98% yield, with 40% D incorporation at the N1-position and 30% D incorporation at the C4-position, presumably by an imine-enamine tautomerization. Subsequently, 151 could be oxidized by air to give 3-arylquinoline 70-d in 97% yield and with 10% D retention at the C4-position, further suggesting that direct carbon insertion may proceed via oxidative dehydrogenation of 1,4-dihydroquinoline (Fig. 5c). Finally, subjecting trifluoromethyl cyclopropane 152 to the standard reaction conditions but using H218O instead of H2O yielded the 18O-incorporated quinoline-3-carboxaldehyde 56-18O, indicating that the oxygen atom in the aldehyde is derived from water (Fig. 5d).

Based on these experiments, possible reaction pathways for the C-D editing of indoles with fluoroalkyl carbenes are shown in Fig. 5e. Firstly, [2 + 1] cycloaddition of the indole with the in situ generated fluoroalkyl carbene occurs to form the N-TBS protected cyclopropane intermediate I, which undergoes TBS group deprotection with the assistance of TBAF or CsF. Concurrent or subsequent ring-opening generates the 3,4-dihydroquinoline anion II, which is readily protonated (by water) to furnish the 1,4-dihydroquinoline intermediate IV following imine-enamine tautomerization. From this key intermediate, two reaction pathways are possible, depending on the reaction conditions. Firstly, intermediate IV (R=F) can undergo oxidative aromatization with the strong oxidant DDQ to produce the 3-(trifluoromethyl)quinoline (3) (pathway I). Alternatively, the gem-difluoromethylene intermediate V can be formed by a base-mediated fluoride elimination (pathway II). On the one hand, intermediate V (R=CF3) undergoes a formal 1,3-hydrogen shift to deliver the defluorinated product 37. On the other hand, for intermediate V (R=F), oxa-Michael addition of water occurs to form intermediate VI, followed by HF elimination to generate intermediate VII. As evidenced by the deuterium labeling studies (vide supra), a formal 1,3-hydrogen shift of VII occurs to produce an intermediate VIII, which eliminates another molecule of HF to furnish the quinoline-3-carboxaldehyde product 56.

To further support the proposed mechanism shown in Fig. 5e, we performed computational studies of the ring-opening of cyclopropane intermediate Int1. As shown in Fig. 6a, nucleophilic attack of fluoride on the TBS group in Int1, via transition state TS1 (ΔG‡ = 14.4 kcal/mol), generates the zwitterionic intermediate Int3, which is exergonic by 40.6 kcal/mol (from Int1) providing the thermodynamic driving force for the ring-opening (Fig. 6a). Protonation of Int3 with H2O via transition state TS2 (ΔG‡ = 7.6 kcal/mol) results in imine intermediate Int5, which can isomerize to the more stable enamine Int6 with a free energy release of ΔG0 = −4.0 kcal/mol. The calculated process for imine-enamine tautomerization is supported by the deuterium labeling studies on the ring-opening of deuterium-labeled cyclopropane 150 to afford the N1 and C3 deuterium labeled intermediate 151 (Fig. 5c). The 1,4-dihydroquinoline Int6 then undergoes a CsF-mediated HF-elimination via TS3 to generate the gem-difluoromethylene intermediate Int8 with a modest barrier of 13.0 kcal/mol (Fig. 6a). The relatively low barrier results from the F ∙ ∙ ∙ Cs interaction as well as the C–H ∙ ∙ ∙ O and C–H ∙ ∙ ∙ F hydrogen bond interactions between the solvent, CsF, and the indole, which stabilizes the transition state TS3 and thus facilitates the HF elimination. Our experimental results also support this facile formation of the gem-difluoromethylene intermediate (Fig. 5b). Subsequently, a 1,4-oxa-Michael addition of H2O to the gem-difluoromethylene Int-8 affords the intermediate Int10 with an energy barrier of 6.2 kcal/mol (Fig. 6b). In turn, Int10 must overcome a relatively high energy barrier of 22.4 kcal/mol (via TS5) to eliminate CsF to form the enol intermediate Int11. CsF/DMSO-assisted formal 1,3-H shift (via TS6, ΔG‡ = 3.1 kcal/mol) produces Int12 (Supplementary Fig. 19). Finally, CsF/DMSO-assisted elimination of HF from Int12 via TS7 (ΔG‡ = 5.7 kcal/mol) furnishes the quinoline-3-carboxaldehyde product 56. Overall, the formation of the enol intermediate via CsF elimination (ΔG‡ = 22.4 kcal/mol) is the rate-determining step in the catalytic cycle.

a Free energy profiles for the formation of gem-difluoromethylene intermediate Int8. b Free energy profiles for Michael addition and CsF/DMSO-assisted formal 1,3-H transfer of Int8 leading to quinoline-3-carboxaldehyde 56. Calculations were carried out at the SMD(DMSO)-M06/6-31 G(d,p)-SDD(Cs) level of theory. Energies are in kcal/mol. Distances are in angstroms. Most hydrogen atoms in 3D structures are omitted for clarity.

We also computationally investigated the origin of the chemoselectivities of CF3- and C2F5-substituted carbenes by analyzing key transition states or intermediates leading to the defluorinative formylation insertion product 56 and the hydrodefluorination insertion product 37 (Fig. 7). Our calculations show that Int8–generated from the CF3-substituted carbene–strongly prefers the Michael addition of H2O leading to product 56 (via TS4, ΔG‡ = 6.2 kcal/mol) compared to Int8-1–generated from the CF2CF3-substituted carbene. Natural Population Analysis (NPA) indicated that Int9 (precursor of TS4) has a larger electronegativity difference between O and C atoms than Int9-1 (the precursor of TS4-1) (Δe = 2.011 vs. Δe = 1.447), thus lowering the energy barrier of TS4. The large difference in electronegativity can be attributed to the stronger electron-withdrawing effect of the trifluoromethyl group than the fluorine atom, which is the origin of the reversed chemoselectivity of Int8-1 (Fig. 7a). In addition, frontier molecular orbital analysis indicates that the stability of the formed allyl carbon anion intermediates (Int10’ and Int10-1’) for the 1,3-H transfer may be influenced by the energy of HOMO orbital and hydrogen bonding interactions (Fig. 7b). More specifically, the energy of HOMO orbital of Int10’ leading to product 26 by CsF/DMSO assisted formal 1,3-H transfer of Int8, is higher than that of Int10-1’ leading to product 37 (EHOMO = −4.59 eV vs. EHOMO = −4.70 eV). Besides, there are more hydrogen bonding interactions in Int10-1’. All these factors can stabilize Int10-1’ and make Int8-1 easier to occur CsF/DMSO-assisted formal 1,3-H transfer to give hydrodefluorination insertion product 37.

Taken together, our combined experimental and DFT calculation results indicate that the formal carbon atom insertion proceeds through a cyclopropanation/fragmentation cascade to generate a key 1,4-dihydroquinoline intermediate, which can then undergo an unprecedented defluorinative aromatization to deliver the hydrodefluorination insertion product 37 or the defluorinative carbonylation insertion product 56, depending on the carbene precursor and reaction conditions. In both processes, CsF and DMSO play critical roles in controlling the chemoselectivity and lowering the activation energy by stabilizing transition states or intermediates via hydrogen bonding interactions.

Thermal hazard assessment using differential scanning calorimetry suggested that there was no impact sensitivity (IS) and/or explosive propagation (EP) in N-triftosylhydrazones (Supplementary Table 8 and Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4), further confiming that N-triftosylhydrazones are operationally safe compared to the corresponding diazo compounds40.

Discussion

In summary, this study substantially expands the chemical space of Ciamician-Dennstedt reaction by using functionalized N-triftosylhydrazones as carbene precursors. This one-pot, two-step procedure allows a variety of carbenes to be inserted into the skeletons of indoles and pyrroles, accessing the corresponding quinolines and pyridines with various 3-substituents, such as trifluoromethyl, difluoromethyl, fluoroalkyl, formyl, alkyl, alkenyl, alkynyl, aryl, and heteroaryl, most of which are challenging to be installed with existing C-D skeletal editing technique. More importantly, this insertion reaction proceeds either through (i) an oxidative aromatization or (ii) a defluorinative aromatization of the 1,4-dihydroquinoline intermediate, which is distinct from the classical C-D reaction pathway and opens a new window for possible single-atom skeletal editing.

Methods

General procedure A for one-carbon insertion of indoles with fluoroalkyl N-triftosylhydrazones

In a glove box, an oven-dried screw-cap reaction tube was charged with fluoroalkyl N-triftosylhydrazone (0.36 mmol), NaH (0.72 mmol, 60 wt% dispersion in mineral oil), N-TBS indole (0.3 mmol), TpBr3Cu(CH3CN) (10 mol%) and PhCF3 (10 mL). Next, the sealed vial was removed from glovebox and stirred at 60 °C for 12 h. After cooling to room temperature, the reaction mixture was filtered through a short pad of silica gel with DCM as an eluent. After removal of the solvent in vacuo, the residue was added TBAF (0.36 mmol, 1.0 mol/L in THF) and DDQ (0.45 mmol.) and THF (10 mL). The resulting mixture was stirred at 25 °C for 10 min and filtered through a short pad of silica gel (pre-treated with triethylamine) with DCM as an eluent. After removal of the solvent in vacuo, the residue was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (pre-treated with trimethylamine, using petroleum ether-EtOAc as eluent) to afford the products.

General procedure B for defluorinative one-carbon insertion of indoles with trifluoroacetaldehyde N-triftosylhydrazones (TFHZ-Tfs)

In a glove box, an oven-dried screw-cap reaction tube was charged with TFHZ-Tfs 2 (0.36 mmol), NaH (0.72 mmol, 60 wt% dispersion in mineral oil), N-TBS indoles (0.3 mmol), TpBr3Cu(CH3CN) (10 mol%) and PhCF3 (10 mL). Next, the sealed vial was removed from glovebox and stirred at 60 °C for 12 h. After cooling to room temperature, the reaction mixture was filtered through a short pad of silica gel with DCM as an eluent. After removal of the solvent in vacuo, the residue was added CsF (0.36 mmol), H2O (20.0 equiv.) and DMSO (10 mL). The resulting mixture was stirred at 25 °C for 10 min and diluted with DCM, washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure to leave a crude product, which was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (pre-treated with trimethylamine, using petroleum ether-EtOAc as eluent) to give the 3-formylquinoline products.

General procedure C for one-carbon insertion of indoles with functionalized N-triftosylhydrazones

In a glove box, an oven-dried screw-cap reaction tube was charged with N-triftosylhydrazone (0.3 mmol), NaH (0.6 mmol, 60 wt% dispersion in mineral oil), N-TBS indole (0.6 mmol), TpBr3Ag(thf) (10 mol%) and PhCF3 (5.0 mL). Next, the sealed vial was removed from glovebox and stirred at 60 °C for 12 h. After cooling to room temperature, the reaction mixture was added TBAF (0.75 mmol, 1.0 mol/L in THF) and stired at 25 °C for 10 min. After completion of the reaction, the mixture was filtered through a short pad of silica gel (pre-treated with triethylamine) with DCM as an eluent. After removal of the solvent in vacuo, the residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel (pre-treated with trimethylamine, using petroleum ether-EtOAc as eluent) to give the corresponding 3-arylquinoline products.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information. The Cartesian coordinates of all optimized structures are available from the Supplementary Data 1. All other data are available in the main text and the Supplementary Information. All data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Hu, Y., Stumpfe, D. & Bajorath, J. Recent advances in scaffold hopping. J. Med. Chem. 60, 1238–1246 (2017).

Acharya, A., Yadav, M., Nagpure, M., Kumaresan, S. & Guchhait, S. K. Molecular medicinal insights into scaffold hopping-based drug discovery success. Drug Discov. Today 19, 103845 (2024).

Endo, A. A historical perspective on the discovery of statins. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 86, 484–493 (2010).

Taylor, E. C. in Successful Drug Discovery, (eds Fischer, J. D. & Rotella, P.) (Wiley, 2015).

Jurczyk, J. et al. Single-atom logic for heterocycle editing. Nat. Synth. 1, 352–364 (2022).

Peplow, M. Almost magical’: chemists can now move single atoms in and out of a molecule’s core. Nature 618, 21–24 (2023).

Liu, Z., Sivaguru, P., Ning, Y., Wu, Y. & Bi, X. Skeletal editing of (hetero)arenes using carbenes. Chem. Eur. J. 29, e202301227 (2023).

Joynson, B. W. & Ball, L. T. Skeletal editing: interconversion of arenes and heteroarenes. Helv. Chim. Acta 106, e202200182 (2023).

Roque, J. B., Kuroda, Y., Göttemann, L. T. & Sarpong, R. Deconstructive diversification of cyclic amines. Nature 564, 244–248 (2018).

Jurczyk, J. et al. Photomediated ring contraction of saturated heterocycles. Science 373, 1004–1012 (2021).

Lyu, H., Kevlishvili, I., Yu, X., Liu, P. & Dong, G. Boron insertion into alkyl ether bonds via zinc/nickel tandem catalysis. Science 372, 175–182 (2021).

Kennedy, S. H., Dherange, B. D., Berger, K. J. & Levin, M. D. Skeletal editing through direct nitrogen deletion of secondary amines. Nature 593, 223–227 (2021).

Hui, C., Brieger, L., Strohmann, C. & Antonchick, A. P. Stereoselective synthesis of cyclobutanes by contraction of pyrrolidines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 18864–18870 (2021).

Miller, D. C., Lal, R. G., Marchetti, L. A. & Arnold, F. H. Biocatalytic one-carbon ring expansion of aziridines to azetidines via a highly enantioselective [1,2]-stevens rearrangement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 4739–4745 (2022).

Wright, B. A. et al. Skeletal editing approach to bridge-functionalized bicyclo[1.1.1]pentanes from azabicyclo[2.1.1]hexanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 10960–10966 (2023).

Zhong, H. et al. Skeletal metalation of lactams through a carbonyl-to-nickel-exchange logic. Nat. Commun. 14, 5273 (2023).

Ning, Y., Chen, H., Ning, Y., Zhang, J. & Bi, X. Rhodium-catalyzed one-carbon ring expansion of aziridines with vinyl-N-triftosylhydrazones for the synthesis of 2-vinyl azetidines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202318072 (2024).

Reisenbauer, J. C., Green, O., Franchino, A., Finkelstein, P. & Morandi, B. Late-stage diversification of indole skeletons through nitrogen atom insertion. Science 377, 1104–1109 (2022).

Woo, J. et al. Scaffold hopping by net photochemical carbon deletion of azaarenes. Science 376, 527–532 (2022).

Wang, H. J. et al. Dearomative ring expansion of thiophenes by bicyclobutane insertion. Science 381, 75–81 (2023).

Hyland, E. E., Kelly, P. Q., McKillop, A. M., Dherange, B. D. & Levin, M. D. Unified access to pyrimidines and quinazolines enabled by N–N cleaving carbon atom insertion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 19258–19264 (2022).

Huang, X.-Y., Xie, P.-P., Zou, L.-M., Zheng, C. & You, S.-L. Asymmetric dearomatization of indoles with azodicarboxylates via cascade electrophilic amination/aza-prins cyclization/phenonium-like rearrangement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 11745–11753 (2023).

Bartholomew, G. L., Carpaneto, F. & Sarpong, R. Skeletal editing of pyrimidines to pyrazoles by formal carbon deletion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 22309–22315 (2022).

Boudry, E., Bourdreux, F., Marrot, J., Moreau, X. & Ghiazza, C. Dearomatization of pyridines: photochemical skeletal enlargement for the synthesis of 1,2-diazepines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 2845–2854 (2024).

Li, L. et al. Dearomative insertion of fluoroalkyl carbenes into azoles leading to fluoroalkyl heterocycles with a quaternary center. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202313807 (2024).

Cheng, Q. et al. Skeletal editing of pyridines through atom-pair swap from CN to CC. Nat. Chem. 16, 741–748 (2024).

Sattler, A. & Parkin, G. Cleaving carbon–carbon bonds by inserting tungsten into unstrained aromatic rings. Nature 463, 523–526 (2010).

Ciamician, G. L. & Dennstedt, M. Ueber die einwirkung des chloroforms auf die kaliumverbindung pyrrols. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 14, 1153–1163 (1881).

Ma, D., Martin, B. S., Gallagher, K. S., Saito, T. & Dai, M. One-carbon insertion and polarity inversion enabled a pyrrole strategy to the total syntheses of pyridine-containing Lycopodium alkaloids: complanadine A and lycodine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 16383–16387 (2021).

Dherange, B. D., Kelly, P. Q., Liles, J. P., Sigman, M. S. & Levin, M. D. Carbon atom insertion into pyrroles and indoles promoted by chlorodiazirines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 11337–11344 (2021).

Joynson, B. W., Cumming, G. R. & Ball, L. T. Photochemically mediated ring expansion of indoles and pyrroles with chlorodiazirines: synthetic methodology and thermal hazard assessment. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202305081 (2023).

Guo, H., Qiu, S. & Xu, P. One-carbon ring expansion of indoles and pyrroles: a straightforward access to 3-fluorinated quinolines and pyridines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202317104 (2023).

Li, C. et al. C-F bond insertion into indoles with CHBr2F: an efficient method to synthesize fluorinated quinolines and quinolones. Chin. J. Chem. 42, 1128–1132 (2024).

Mortén, M., Hennum, M. & Bonge-Hansen, T. Synthesis of quinoline-3-carboxylates by a Rh(II)-catalyzed cyclopropanation-ring expansion reaction of indoles with halodiazoacetates. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 11, 1944–1949 (2015).

Peeters, S., Berntsen, L. N., Rongved, P. & Bonge-Hansen, T. Cyclopropanation–ring expansion of 3-chloroindoles with α-halodiazoacetates: novel synthesis of 4-quinolone-3-carboxylic acid and norfloxacin. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 15, 2156–2160 (2019).

Stenner, R., Steventon, J. W., Seddon, A. & Anderson, J. L. R. A de novo peroxidase is also a promiscuous yet stereoselective carbene transferase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 1419–1428 (2020).

Davies, H. M. & Spangler, J. E. Reactions of indoles with metal-bound carbenoids. Adv. Heterocycl. Chem. 110, 43–72 (2013).

Liu, S. et al. Tunable molecular editing of indoles with fluoroalkyl carbenes. Nat. Chem. 16, 988–997 (2024).

Yang, Y. et al. Controllable skeletal and peripheral editing of pyrroles with vinylcarbenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202401359 (2024).

Liu, Z., Sivaguru, P., Zanoni, G. & Bi, X. N-Triftosylhydrazones: a new chapter for diazo-based carbene chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 55, 1763–1781 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Site-selective C–H benzylation of alkanes with N-triftosylhydrazones leading to alkyl aromatics. Chem. 6, 2110–2114 (2020).

Yang, Y. et al. Site-selective C−H allylation of alkanes: facile access to allylic quaternary sp3-carbon centers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202214519 (2023).

Michael, J. P. Quinoline, quinazoline and acridonealkaloids. Nat. Prod. Rep. 25, 166–187 (2008).

Heravi, M. M. & Zadsirjan, V. Prescribed drugs containing nitrogen heterocycles: an overview. RSC Adv. 10, 44247–44311 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Fluorine in pharmaceutical industry: fluorine-containing drugs introduced to the market in the last decade (2001–2011). Chem. Rev. 114, 2432–2506 (2014).

Zhou, Y. et al. Next generation of fluorine-containing pharmaceuticals, compounds currently in phase II–III clinical trials of major pharmaceutical companies: new structural trends and therapeutic areas. Chem. Rev. 116, 422–518 (2016).

Zhang, X. et al. Use of trifluoroacetaldehyde N-tfsylhydrazone as a trifluorodiazoethane surrogate and its synthetic applications. Nat. Commun. 10, 284 (2019).

Ning, Y. et al. Difluoroacetaldehyde N-triftosylhydrazone (DFHZ-Tfs) as a bench-stable crystalline diazo surrogate for diazoacetaldehyde and difluorodiazoethane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 6473–6481 (2020).

Rodríguez, A. M., Molina, F., Díaz-Requejo, M. M. & Pérez, P. J. Copper-catalyzed selective pyrrole functionalization by carbene transfer reaction. Adv. Synth. Catal. 362, 1998–2004 (2020).

Hu, Y. et al. Antitumor and topoisomerase IIα inhibitory activities of 3-aryl-7-hydroxyquinolines. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 39, 3230–3236 (2019).

Tseng, C.-H. et al. Synthesis and antiproliferative evaluation of 3-phenylquinolinylchalcone derivatives against non-small cell lung cancers and breast cancers. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 59, 274–282 (2013).

Yang, C.-Y. et al. Discovery of 2-substituted 3-arylquinoline derivatives as potential anti-Inflammatory agents through inhibition of LPS-induced inflammatory responses in macrophages. Molecules 24, 1162 (2019).

Cheng, K.-W. et al. Specific inhibition of bacterial β-glucuronidase by pyrazolo[4,3-c]quinoline derivatives via a pH-dependent manner to suppress chemotherapy-induced intestinal toxicity. J. Med. Chem. 60, 9222–9238 (2017).

Felicetti, T. et al. Modifications on C6 and C7 positions of 3-phenylquinolone efflux pump inhibitors led to potent and safe antimycobacterial treatment adjuvants. ACS Infect. Dis. 5, 982–1000 (2019).

Thandra, D. R. & Allikayala, R. Synthesis, characterization, molecular structure determination by single crystal X-ray diffraction, and hirshfeld surface analysis of 7-fluoro-6-morpholino-3-phenylquinolin-1-ium chloride salt and computational studies of its cation. J. Mol. Struct. 1250, 131701 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22331004 to X.B. and No. 22371035 to Z.L.) and the Science and Technology Development Plan Project of Jilin Province, China (No. 20240305092YY to Z.L.). E.A.A. and X.B. thank the Royal Society for support (Newton Advanced Fellowship to X.B., NAF\R1\191210).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L., Y.Y., and Q.S. contributed equally to this work. S.L. and Y.Y. conducted the experiments and analyzed the data. Q.S. carried out the DFT calculations. Y.Z. helped with substrate synthesis and data collection. G.R. provided NHC-Fe/Co catalysts. Z.L., E.A.A., and X.B. conceived the concept, supervised the experiments, and prepared the manuscript with P.S. and G.R. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Xiaotian Qi, who co-reviewed with Yixin Luo; Ke Zheng and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, S., Yang, Y., Song, Q. et al. Halogencarbene-free Ciamician-Dennstedt single-atom skeletal editing. Nat Commun 15, 9998 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54379-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54379-8

This article is cited by

-

Decatungstate-photoinitiated skeletal editing of cyclic ketones by ring expansion/acylation

Science China Chemistry (2026)