Abstract

We present super-resolved coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (CARS) microscopy by implementing phase-resolved image scanning microscopy, achieving up to two-fold resolution increase as compared with a conventional CARS microscope. Phase-sensitivity is required for the standard pixel-reassignment procedure since the scattered field is coherent, thus the point-spread function is well-defined only for the field amplitude. We resolve the complex field by a simple add-on to the CARS setup enabling inline interferometry. Phase-sensitivity offers additional contrast which informs the spatial distribution of both resonant and nonresonant scatterers. As compared with alternative super-resolution schemes in coherent nonlinear microscopy, the proposed method is simple, requires only low-intensity excitation, and is compatible with any conventional forward-detected CARS imaging setup.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Far-field super-resolution optical microscopy has advanced from an exploratory concept to a bioimaging reality in the past 30 years. Traditionally, super-resolution modalities are associated with incoherent signals, predominantly fluorescence. These are based on a variety of physical principles, violating one or more of the underlying assumptions in the derivation of the diffraction limit. Stimulated emission depletion microscopy (STED), which utilizes the extreme nonlinearity of fluorescence depletion (either by stimulated emission or by shelving), is based on quenching fluorescence outside an arbitrarily small volume1. Saturated excitation microscopy (SAX) uses fluorescence saturation directly via observation of the temporal harmonics of the fluorescent signal under modulated excitation2. Techniques like photo-activated localization microscopy (PALM)3 or stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM)4 and super-resolution optical fluctuation imaging (SOFI)5 rely on the utilization of temporal dynamics in the fluorescence signal. Another approach is based on spatially modulated excitation and includes modalities like structured illumination microscopy (SIM)6, random illumination microscopy (RIM)7, and image scanning microscopy (ISM)8,9. These methods take advantage of the increased Fourier support due to the spatial modulation of the excitation to improve resolution. While limited in their ability to increase resolution, these techniques are usually much simpler to implement.

The implementation of super-resolution for imaging modalities based on coherent scattering is lagging behind that of fluorescence. This is despite the fact that the coherence of the signals opens up new opportunities for imaging based on synthetic apertures, such as tomography (and ptychography)10,11,12,13. This lag is due to several reasons, including the difficulty to saturate scattering processes, the fact that the point spread function is only defined for the field amplitude (rather than the intensity) in coherent imaging, the difficulty in temporally modulating the scattering cross-section and the limited pulse energy of laser sources used for coherent imaging which often limits wide-field nonlinear excitation modalities. This is true for coherent nonlinear scattering-based imaging techniques, such as second harmonic generation (SHG)14, third harmonic generation (THG)15, and coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (CARS)16. To date, most of the efforts to perform super-resolution coherent imaging focused on CARS microscopy. CARS is a widely used vibrational imaging method whereby two laser fields at the pump (ωp) and Stokes (ωs) frequencies interact with a medium coherently to generate a new field at the anti-Stokes frequency (ωas = 2ωp−ωs) via a third-order induced polarization16,17. CARS, therefore, affords a non-destructive, label-free method of imaging, which has led it to be one of the most used nonlinear microscopy methods in biology. Nonlinear laser scanning microscopy also offers deeper sample penetration on two fronts: first, the nonlinear intensity dependence provides inherent optical sectioning capability without the use of a pinhole, recovering signal otherwise blocked by the pinhole18; second, near-infrared (NIR) excitation wavelengths lead to greater penetration depth19. Due to the diffraction limit, this leads to lower spatial resolution compared to the shorter-wavelength excitation used in fluorescence microscopy. Therefore, enhancing the resolution of CARS microscopy in particular, and other variants of coherent Raman imaging in general, is highly desirable.

Past attempts to achieve super-resolved coherent Raman microscopy have relied on analogs of fluorescence-based methods. An STED-like configuration was demonstrated by depleting the pump beam using a competing nonlinear process20,21,22. Another STED-like approach used a photoswitchable Raman probe to deplete the Stimulated Raman Scattering (SRS) signal23. A SAX-like configuration utilized saturation of the vibrational transition24,25. The use of higher order nonlinearity (that is, χ(5) or χ(7) rather than χ(3) as in standard CARS)26 is, in many senses, equivalent to SAX and serves the same purpose. Nevertheless, achieving saturation or depletion for a third-order nonlinear signal (or equivalently, the excitation of higher-order nonlinearity) typically requires very high excitation powers, at the level of 1011 W/cm2 and significant experimental complexity, making such methods rather impractical for biological microscopy applications. A RIM analog of CARS imaging was demonstrated utilizing dynamic speckle illumination for both the pump and the Stokes beams in a wide-field CARS microscope27. This makes the CARS signal quasi-incoherent enabling the use of an analysis similar to that used in fluorescence imaging. A similar concept was realized with SRS28.

Perhaps the most natural super-resolution modality to be applied to CARS imaging is ISM, which is by definition a laser scanning modality. ISM is a variant of confocal microscopy that offers access to the full signal collected through an open aperture while maintaining the spatial resolution gained from a closed aperture confocal. This is possible through the use of a pixelated detector in place of a bucket detector, where each pixel now behaves as a small pinhole. Proposed in 19888, it was first experimentally demonstrated in 20109 and it was later applied to SHG microscopy29,30 using a similar analysis as in the incoherent case. Yet, it was later shown that for SHG in particular, and for coherent scattering in general, the ISM analysis must take coherence into account and, for that end, requires either an interferometric microscope31 or direct access to the field (as in photoacoustic imaging)32.

In this work, we apply ISM to CARS by developing a phase-sensitive CARS microscope that enables reconstruction of the full CARS field and, therefore, coherent ISM. We show that for CARS, there is a spatial variation of phase arising from the relative resonant and nonresonant scattering contributions. This requires knowledge of the full field in order to reassign pixel intensities appropriately. We show that CARS-ISM achieves a resolution gain of ~1.8, which is comparable to all previously reported methods of super-resolved CARS, both widefield and laser-scanning, while operating with significantly lower excitation power than STED- and SAX-like methods and requiring a relatively simple extension to the most commonly used CARS microscope configuration employing laser scanning of a single diffraction-limited spot.

Theory of CARS-ISM

ISM makes use of a pixelated detector as an array of pinholes in order to retrieve the resolution offered by a closed aperture while making use of the signal collected by the entire detector. Due to parallax, each off-axis pixel captures a shifted image, so the straightforward summation of pixel intensities results in lost resolution in the same way as opening a confocal pinhole. Shifting the single-pixel images appropriately via a process called pixel reassignment33, corrects for parallax, thus regaining the single-pixel resolution while maintaining all of the signals of an open aperture.

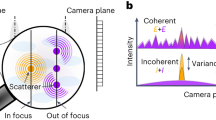

However, ISM was developed to enhance incoherent signals, so the pixel reassignment analysis assumes that individual sources do not interfere and, therefore, that the PSF is well-defined for measured intensity. Yet for CARS, the PSF is only defined for the field amplitude, since even in the simple case of two-point sources, the intensity image captured by the camera relates to the fields of two scatterers as follows:

where E1,2 are the field amplitudes generated by two-point sources. Pixel reassignment must, therefore, be carried out directly on the field amplitude in order to have access to the full possible resolution and avoid artifacts by considering interference terms, as illustrated in Fig. 1a and b. To compute the necessary pixel reassignment and assess the potential resolution gain from coherent ISM in the CARS context, let us assume spatially invariant and Gaussian excitation and detection amplitude spread functions (ASF). The excitation ASF is proportional to

where hp, σp, hs, and σs are the ASF and widths of the pump and Stokes beams, respectively. We define the detection ASF to be the distribution of the detected field of a point source along the camera pixels, given a uniform illumination:

Rs and Rd represent the location of the emitter and a specific pixel in the array with respect to the optical axis on the sample plane, and σc is the width of the CARS signal amplitude spread function. The total response is the multiplication of the excitation and detection amplitude spread functions, as illustrated in Fig. 1c. We can then calculate the shift in the optical axis needed to compensate for parallax:

The estimated resolution from the width of the total response is

which is narrower compared to both excitation and detection ASFs, as expected (see Supplementary Information section 1.1 for a full derivation). In reality, these shifts must be corrected for aberrations. Practically, we obtain the shift vectors numerically by computing the cross-correlation between images from different detector pixels, see Supplementary Information section 1.2. It is worth noting that this approach still assumes PSF shift-invariance. According to Eq. (5), for the experimental conditions used in the experiments described below, we expect to obtain a resolution of σT = 220 nm from coherent ISM. This is compared to the expected resolution given by the excitation ASF: \({\sigma }_{{{ASF}}}=\frac{{\sigma }_{{{p}}}{\sigma }_{{{s}}}}{\sqrt{2{\sigma }_{{{s}}}^{2}+{\sigma }_{{{p}}}^{2}}}\approx 326\) nm. Therefore we expect a circa 1.5× resolution gain. Notably, the exact value depends on the exact shape of the ASFs (which are generally not Gaussian)8.

b The phase impacts the total signal measured on the detector and having access to phase information distinguishes between resonant and nonresonant signal, which are generated with π/2 phase difference in CARS. c The excitation beam (red) defines the optical axis and constitutes the product of the Stokes (dark red) with the squared pump (green) ASF. The detection ASF (blue) represents the response to different locations of the source, assuming uniform illumination. The total response (gray) is the multiplication of the excitation and detection ASF and peaks at a distance described by Eq. (4).

In fluorescence-based ISM, Fourier reweighting is often applied to further enhance spatial resolution. This procedure involves the amplification of the high spatial frequency components so as to compensate for their reduced value following free-space propagation. Notably, for coherent processes, this is significantly less effective since the frequency response is much more uniform over spatial frequencies (see Supplementary Information section 1.4).

Results

To realize CARS-ISM we must build an interferometrically stable setup for characterizing both the amplitude and the phase of the CARS signal as a function of the sample and detector position. We do this by constructing a nearly inline interferometer where the reference is generated by four-wave mixing in a thin glass slide and propagates collinearly with the pump and Stokes beams, as described schematically in Fig. 2. Briefly, the 790 nm pump beam and the 1020 nm Stokes beam are generated by a Ti:sapphire oscillator and a synchronously pumped optical parametric oscillator, respectively. The reference signal is generated via nonresonant four-wave mixing in a glass slide. The phase of the reference beam is externally controlled in a reflective 4f prism-based pulse shaper where a piezoelectric transducer introduces a relative delay between the reference and excitation arms. The pump, Stokes, and reference beams are focused onto the sample by a high-NA objective and the forward-scattered signal is collected through a second high-NA objective. The sample is raster scanned with an X–Y–Z piezoelectric stage, and the interference of the reference and CARS signal is spectrally filtered from the excitation and imaged onto a sCMOS camera such that the excitation spot is imaged on an area of circa 10 × 10 pixels. A detailed description of the setup appears in the Supplementary Information section 2.

The pump (green) passes through an optical parametric oscillator (OPO) to generate the Stokes (red). The laser beams are combined spatially on a dichroic mirror, and the pulses are temporally overlapped by maximizing their sum frequency signal, generated from a beta barium borate (BBO) crystal. The combined excitation is focused on a glass slide to produce the reference beam (blue). Both excitation and reference are sent into a reflective 4f prism shaper, facilitating scanning of the relative phase between the reference and the CARS signal. The beams are focused and recollected from the sample using high NA objectives. Spectral filters are used to clean the pump beam and to spectrally isolate the CARS signal.

The CARS signal is extracted using phase-shifting interferometry, modulating the reference at phases of \(\phi=0,\frac{\pi }{2},\pi,\frac{3\pi }{2}\). The CARS amplitude ∣E∣ and phase θ are then:

where I(ϕ) is the measured intensity in a specific pixel for a recorded image with the reference beam delayed by phase ϕ, shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. For a full derivation, see Supplementary Information section 1.3. η is a correction compensating for the loss of interference contrast introduced by small mismatches in the spectral overlap of the signal and reference pulses and is typically 0.6–0.7 in our experiments. We estimate η from the intensity interference contrast in the spectral and spatial domain. Once the CARS signal is obtained, it can be summed up incoherently over the entire camera to obtain the regular CARS image, pixel-reassigned to obtain the CARS-ISM image, and further Fourier-reweighted to obtain the FR-CARS-ISM image. As described above, the pixel reassignment shift map is obtained directly from an experimental calibration to compensate for system and sample aberrations (see Supplementary Information section 1.2).

HEK cells

We begin by imaging HEK cells, fixed in EprediaTM Immu-MountTM (Mfr No. EprediaTM 9990402). Our system is tuned to the characteristic lipid C–H stretch band (2850 cm−1). To replicate an open-aperture confocal microscope, we treat the camera as a single bucket detector and integrate the signal from all camera pixels. Figure 3 compares the CARS intensity (∣E∣2) images from the open-aperture summation of pixels (Fig. 3b and h), central-pixel confocal images (Fig. 3c and i), CARS-ISM (Fig. 3d and j), and FR-CARS-ISM (Fig. 3e and k). The results in Fig. 3 were obtained using Ppump = 4.8 mW and PStokes = 2.8 mW at the objective with 40 ms pixel dwell time, resulting in acquisition times of a few minutes for a single image (this is multiplied by 4 to retrieve the field). We note that the pixel dwell time is currently limited by the scanning stage response and the synchronization of the camera acquisition and not by the signal level. The basic open-aperture CARS images (Fig. 3b and h) involve no reference beam in order to provide a fair comparison to a typically obtained CARS image. Additionally, the phase images shown in Fig. 3f and l correspond to the ISM intensity images (Fig. 3d and j). The spatial variation of the phase conveys the local ratio of resonant and nonresonant scattering since a resonant CARS signal is generated at a π/2 phase shift relative to the nonresonant signal. We attribute the experimentally observed negative phases in Fig. 3f) to phase drifts between the four relative measurements. Our results showcase the additional contrast provided by phase imaging in CARS microscopy. The qualitative similarity between the phase and intensity images indicates the validity of our approach to the reassignment procedure on the field.

CARS intensity images of HEK cells. a and g basic CARS image of a large field of view (15 × 15 μm) of several cells with squares marking the region imaged in b–f and h–l, respectively. The intensity ∣ECARS∣2 is plotted in b and h by considering straightforward integration of the signal from all detector pixels (basic CARS); c and i the confocal image retrieved from the central pixel of the detector; d and j the ISM image obtained from performing pixel reassignment on the field amplitude captured by each detector pixel; e and k the ISM image following Fourier reweighting analysis. All intensity figures are normalized to the same total intensity and plotted on the same color scale. Additionally, the phase images corresponding to the ISM images are shown in (f) and (l). m and n show line cuts from the cells in a–f and g–l, respectively, comparing open-aperture, confocal, ISM, and FR-ISM. Excitation power before the objective is Ppump = 4.8 mW and PStokes = 2.8 mW. Pixel dwell time is ~40 ms per modulation phase. The intensity image insets in m and n are scaled differently to show detail. Scale bar = 1 μm.

Notably, in contrast with fluorescence microscopy, in CARS imaging, we observe a negligible resolution enhancement from Fourier reweighting. This is due to the fact that the magnitude of both the excitation and the detection ASFs is independent of spatial frequency (see Supplementary Information 1.4 for details). We nevertheless observe a contrast enhancement from the FR procedure. Line cuts in Fig. 3m and n show the increased resolution following pixel reassignment as compared to open aperture, comparable resolution but better signal-to-noise as compared to confocal, and increased contrast (at the expense of signal to noise ratio (SNR)) after Fourier reweighting. Analysis of images using the Fourier ring correlation method indicates a resolution increase of 1.5–2× in the CARS-ISM image as compared with the CARS image, and minor (up to 1.1) additional resolution gain following Fourier reweighting (see Supplementary Information section 1.5 for details). This is in general agreement with the expected resolution increase as derived from Eq. (5) assuming diffraction-limited excitation beams.

Resolution

To provide an alternative quantification of the resolution enhancement obtained using CARS-ISM, we lithographically fabricated resolution targets from a Raman-active polymer (ZEP), as shown in Fig. 4. Our sample was fabricated using e-beam lithography and characterized by atomic force microscopy (AFM) as described in Supplementary Information section 3. Each element in the target consists of 650 nm deep line pairs, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 6. The periodicity varied from 400 to 700 nm. Since the target consists of a combination of polymer and air gaps, it introduces significant aberrations both in excitation and in detection. We, therefore, choose to look at the images from several individual detector pixels, mimicking a closed-aperture confocal system, rather than employing pixel reassignment. Images obtained by summation of all detector pixels (in the absence of a reference) are shown in Fig. 4b, g, l, and q, and represent the basic CARS resolution. The on-axis single-pixel intensity images (squaring the field reconstruction after interference with a reference beam) serve as a proxy for the resolution which can be obtained in CARS-ISM after pixel reassignment and indicate that the resolving power of our system is improved from circa 700 nm in the open-aperture (OA) image to between 400 and 500 nm, indicating a resolution gain of ~1.5–1.6×. Figure 4c, h, m, and r show single-pixel images taken in the first minimum of the detection PSF Airy disk, where we observe significant image distortion due to aberrations induced by the refractive index mismatch of the sample, as discussed in the Supplementary Information section 4. Such effects are largely minimized in the images of cells in Fig. 3, due to much smaller variation in refractive index. Images from the first Airy ring (Fig. 4e, j, o, and t) show significant distortion but a slightly increased resolution. This is a reasonable outcome of the fact that the system PSF is not fully spatially invariant34. To further supplement our estimate of the resolution gain offered by CARS-ISM, we image an edge in the polymer resolution target and extract via deconvolution a resolution gain of 1.87 from pixel reassignment (see Supplementary Information section 5). The results of Fourier ring correlation (FRC) analysis, edge deconvolution, and line cuts of biological samples are all in general agreement with the expected resolution gain in the range of 1.5–2.

Ground truth images obtained via AFM are shown in panels a, f, k, and p. b, g, l, and q show the standard open aperture (OA) CARS image, where CARS signal (involving no reference beam) from all detector pixels is summed. c, h, m, and r show confocal (single on-axis pixel) CARS images, as a proxy for the resolution obtained by pixel reassignment. d, i, n, and s show images from pixels located at 1 Airy unit from the optical axis, and e, j, o, and t show images from pixels located at 1.3 Airy units. Scalebar = 1 μm.

Discussion

We have shown that the resolution of conventional CARS imaging can be enhanced by a factor of circa 1.8 by a combination of interferometric CARS imaging with ISM and appropriate pixel reassignment (performed on the field amplitude rather than on the intensity). We have also shown that specifically for coherent Raman signals, there is an inherent variation of CARS phase on position due to the different relative contributions of resonant and nonresonant scattering, which necessitates the measurement of the complex field amplitude to avoid artifacts. Our technique utilizes a nearly inline interferometer using a modified pulse shaper and, as such, does not require active stabilization and adds limited complexity to the optical setup while offering a relatively straightforward analysis. The main cost of this is a fourfold increase in the imaging time due to the need to implement phase-shifting interferometry, requiring four acquisitions per pixel. Notably, however, in the present realization, it can only be practically implemented as forward-scattering CARS. This configuration benefits from higher signal strength and better SNR but can only be applied to relatively thin, transparent specimens and limits access to the sample if employing other detection modalities such as electrophysiology. Different past implementations of super-resolved coherent Raman imaging have utilized somewhat different excitation and collection objectives having different numerical apertures and used different methods for estimating the resolution. Thus, a direct comparison of the obtained spatial resolution may be misleading. It is, therefore, more useful to compare the resolution gain rather than the absolute values. Practically all previously reported methods exhibit a resolution gain in the range of 1.5–2. For a comprehensive list, see Supplementary Table 2 in the Supplementary Information file. RIM-CARS showed the highest reported value, of about 2, whereas saturation-based methods and higher order CARS showed values of around 1.6. Therefore, the resolution gain from CARS-ISM is comparable to those while not requiring either strong excitation fields (in fact, the use of the reference as a local oscillator enables the detection of relatively weaker signals) or the use of a specialized setup as in widefield RIM-CARS.

As presented above, there is still room for improvement in the CARS-ISM setup and sensitivity in various aspects. Due to the use of a reference beam, which is focused onto the sample along with the pump and Stokes beams, it is rather sensitive to chromatic aberrations, which result in distortion of the reference phase across the image. Further, the phase stability between the reference and the pump and Stokes beams would be greatly improved without the use of three separate reflecting elements in the prism compressor. This could be achieved, for example, by replacing them with a deformable mirror to perform phase-shifting interferometry. Such an element could also better compensate dispersion so as to improve the spectral overlap between the reference and the generated signal. A rough characterization of the stability of phase measurements in the current implementation can be found in Supplementary Information section 6. At present, the use of a camera limits the acquisition rate at every pixel. Nevertheless, much faster detectors such as monolithic SPAD arrays have already been used in ISM to speed up the acquisition process35. Exhibiting very low dark count rates (especially upon time gating), these should exhibit similar performance to high-end scientific CMOS cameras. Using SPAD array imagers and (descanned) laser scanning would enable to perform CARS-ISM at a speed limited only by the signal level and not by the scanning or imaging apparatus, corresponding to one to two orders of magnitude improvement in acquisition speed as compared with the currently presented results. A comparison of effective acquisition speed with other reported methods of super-resolved coherent Raman is included in Supplementary Table 2.

One should note that the analysis used here utilizes pixel reassignment, which makes the approximation of a spatially invariant ASF. This is not strictly correct, especially under high numerical aperture illumination and collection (see Supplementary Figs. 7–9). An alternative to pixel reassignment, which solves a global optimization problem and avoids this assumption, has recently been shown to yield superior results in terms of spatial resolution in fluorescence imaging34. This method can be adapted to CARS-ISM upon proper calibration of the ASF. Finally, we note that many CARS applications require epi-detection of the CARS signal. The phase variation between resonant and nonresonant components of the CARS signal is maintained also for backscattered signals (in contrast with a forward signal which is backscattered following further propagation in the sample). Thus, phase information is still required for proper pixel reassignment. As presented here, the inline interferometry method is not suitable for generating a reference in the backward direction. One possible alternative is to use a strong nonresonant background, generated along with the resonant signal, as a replacement for the reference, but this requires significant modifications to the setup. Another is the use of a wavefront sensor for imaging. This introduces other complexities to CARS-ISM, such as the need for phase unwrapping.

We have presented a simple add-on to a scanning CARS microscope that enables super-resolved CARS by implementing coherent ISM to gain a factor of 1.5–2 in resolution. Coherent ISM relies on appropriately reassigning the field amplitude rather than the intensity, requiring that phase information is retrieved. We measure phase directly by inline interferometry in order to reconstruct the full CARS field. From the phase measurements, we also gain spatially varying information on the sample's resonant and nonresonant emitter content. We also suggest that more rigorously accounting for system aberrations, which are enhanced in coherent microscopy, holds the potential for further resolution increase.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Code availability

The code used during the current study is available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Klar, T. A. & Hell, S. W. Subdiffraction resolution in far-field fluorescence microscopy. Opt. Lett. 24, 954 (1999).

Fujita, K., Kobayashi, M., Kawano, S., Yamanaka, M. & Kawata, S. High-resolution confocal microscopy by saturated excitation of fluorescence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 228105 (2007).

Betzig, E. et al. Imaging intracellular fluorescent proteins at nanometer resolution. Science 313, 1642–1645 (2006).

Rust, M. J., Bates, M. & Zhuang, X. Sub-diffraction-limit imaging by stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (storm). Nat. Methods 3, 793–795 (2016).

Dertinger, T., Colyer, R., Iyer, G., Weiss, S. & Enderlein, J. Fast, background-free, 3d super-resolution optical fluctuation imaging (SOFI). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 22287–22292 (2009).

Gustafsson, M. G. Surpassing the lateral resolution limit by a factor of two using structured illumination microscopy. J. Microsc. 198, 82–87 (2000).

Mudry, E. et al. Structured illumination microscopy using unknown speckle patterns. Nat. Photonics 6, 312–315 (2012).

Sheppard, C. J. R. Super-resolution in confocal imaging. Optik (Stuttgart) 80, 53–54 (1988).

Müller, C. B. & Enderlein, J. Image scanning microscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 198101 (2010).

Heuke, S. et al. Coherent anti-stokes Raman Fourier ptychography. Opt. Express 27, 23497–23514 (2019).

Heuke, S., Rigneault, H. & Sentenac, A. 3d-coherent anti-stokes Raman scattering Fourier ptychography tomography (cars-fpt). Opt. Express 29, 4230–4239 (2021).

Hu, C. et al. Harmonic optical tomography of nonlinear structures. Nat. Photonics 14, 564–569 (2020).

Farah, Y. et al. Synthetic spatial aperture holographic third harmonic generation microscopy. Optica 11, 693–705 (2024).

Gannaway, J. N. & Sheppard, C. J. R. Second-harmonic imaging in the scanning optical microscope. Opt. Quant. Electron. 10, 435–439 (1978).

Squier, J. A., Müller, M., Brakenhoff, G. J. & Wilson, K. R. Third harmonic generation microscopy. Opt. Express 3, 315–324 (1998).

Duncan, M. D., Reintjes, J. & Manuccia, T. J. Scanning coherent anti-stokes Raman microscope. Opt. Lett. 7, 350–352 (1982).

Zumbusch, A., Holtom, G. R. & Xie, X. S. Three-dimensional vibrational imaging by coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 4142 (1999).

Denk, W., Strickler, J. H. & Webb, W. W. Two-photon laser scanning fluorescence microscopy. Science 248, 73–76 (1990).

Kobat, D. et al. Deep tissue multiphoton microscopy using longer wavelength excitation. Opt. Express 17, 13354–13364 (2009).

Silva, W. R., Graefe, C. T. & Frontiera, R. R. Toward label-free super-resolution microscopy. ACS Photonics 3, 79–86 (2016).

Kim, D. et al. Selective suppression of stimulated Raman scattering with another competing stimulated Raman scattering. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 6118–6123 (2017).

Choi, D. S. et al. Selective suppression of CARS signal with three-beam competing stimulated Raman scattering processes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 17156–17170 (2018).

Shou, J. et al. Super-resolution vibrational imaging based on photoswitchable Raman probe. Sci. Adv. 9, eade9118 (2023).

Yonemaru, Y. et al. Super-spatial-and-spectral-resolution in vibrational imaging via saturated coherent anti-stokes Raman scattering. Phys. Rev. Appl. 4, 014010 (2015).

Gong, L., Zheng, W., Ma, Y. & Huang, Z. Saturated stimulated-Raman-scattering microscopy for far-field superresolution vibrational imaging. Phys. Rev. Appl. 11, 034041 (2019).

Gong, L., Zheng, W., Ma, Y. & Huang, Z. Higher-order coherent anti-stokes Raman scattering microscopy realizes label-free super-resolution vibrational imaging. Nat. Photonics 14, 115–122 (2020).

Fantuzzi, E. M. et al. Wide-field coherent anti-stokes Raman scattering microscopy using random illuminations. Nat. Photonics 17, 1097–1104 (2023).

Guilbert, J. et al. Label-free super-resolution stimulated Raman scattering imaging of biomedical specimens. Adv. Imaging 1, 011004 (2024).

Gregor, I. et al. Rapid nonlinear image scanning microscopy. Nat. Methods 14, 1087–1089 (2017).

Stanciu, S. G. et al. Super-resolution re-scan second harmonic generation microscopy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2214662119 (2022).

Raanan, D., Song, M. S., Tisdale, W. A. & Oron, D. Super-resolved second harmonic generation imaging by coherent image scanning microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 120, 071111 (2022).

Sommer, T. I. & Katz, O. Pixel-reassignment in ultrasound imaging. Appl. Phys. Lett. 119, 123701 (2021).

Sheppard, C. J. R., Mehta, S. B. & Heintzmann, R. Superresolution by image scanning microscopy using pixel reassignment. Opt. Lett. 38, 2889–2892 (2013).

Rossman, U., Dadosh, T., Eldar, Y. C. & Oron, D. cSPARCOM: multi-detector reconstruction by confocal super-resolution correlation microscopy. Opt. Express 29, 12772–12786 (2021).

Castello, M. et al. A robust and versatile platform for image scanning microscopy enabling super-resolution film. Nat. Methods 16, 175–178 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank Shira Cohen and Professor Philipp Selenko for preparing and providing HEK cell samples. We thank Irit Goldian for her assistance in obtaining AFM images. D.O. is the incumbent of the Harry Weinrebe professorial chair of laser physics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.Z. and E.B. built the system, performed the experiments, and analyzed the data. OB prepared the resolution target samples. D.O. conceived the idea and supervised the project. A.Z. and D.O. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Li Gong, Simon Labouesse and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhitnitsky, A., Benjamin, E., Bitton, O. et al. Super-resolved coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy by coherent image scanning. Nat Commun 15, 10073 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54429-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54429-1