Abstract

Tropospheric ozone formation depends on the emissions of volatile organic compounds (VOC) and nitrogen oxides (NOx). In megacities, abundant VOC and NOx sources cause relentlessly high ozone episodes, affecting a large share of the global population. This study uses data from the Ozone Monitoring Instrument for formaldehyde (HCHO) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) as proxy data for VOC and NOx emissions, respectively, with their ratio serving as an indicator of ozone sensitivity. Ground-level ozone (O3) reanalysis from the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring is used to assess the O3 trends. We evaluate changes from 2005 to 2019 and their relationship with the warming environment in 41 megacities worldwide, applying seasonal Mann-Kendall, trend decomposition methods, and Pearson correlation analysis. We reveal significant increases in global HCHO (0.1 to 0.31 × 1015 mol cm−2 year−1) and regionally varying NO2 (−0.22 to 0.07 × 1015 mol cm−2 year−1). O3 trends range from −0.31 to 0.70 ppb year−1, highlighting the relevance of precursor abundance on O3 levels. The strong correlation between precursor emissions and increasing temperature suggests that O3 will continue to rise as climate change persists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Urban agglomerations have increased significantly over the last two decades. In 2016, 54% of the global population lived in urban areas1, and by 2022, 10% of the urban population was concentrated in 44 megacities2. Projections indicate that the number of urban residents will continue to increase in the coming years2. One undesirable effect of urban growth is the deterioration of air quality. Megacities are often characterised by high levels of air pollution and are especially critical in developing economies3. Simultaneously, the rising urban population puts more people at risk of exposure to deteriorating air quality, increasing morbidity and mortality attributable to ambient air pollution4,5.

Ground-level ozone (O3) is responsible for increased premature deaths and hospital admissions owing to cardiovascular and respiratory diseases6. In 2019, chronic O3 exposure led to 147,100 deaths in urban areas worldwide, with a population exceeding 50,0007. The adverse effects of O3 on crops, ecosystems, and materials have been well-documented8,9,10. O3 also poses a threat to biodiversity11,12 and acts as a greenhouse gas, contributing to climate change13. Although efforts to improve air quality in cities of developed economies have reduced the concentration of primary pollutants, high concentrations of secondary air pollutants, such as O3, remain concerning. Between 2000 and 2019, summertime O3 daily maximum 8-hour values (MDA8) increased in 74% of urban areas worldwide. In cities under VOC-limited conditions, mean O3 concentrations also increased owing to reduced nitrogen oxides (NOx) emissions, resulting in less titration of O3 by NO14. In remote areas, O3 levels rose owing to increased NOx emissions and transport of O3 and its precursor from urban areas15,16,17. Furthermore, nocturnal O3 pollution, which is historically considered to be low and unthreatening, is of rising concern in several regions, such as the United States and China, owing to reduced NOx emissions without similar reductions in the volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions18.

Ozone in the troposphere is formed by a series of reactions driven by the emission of NOx and VOC induced by solar radiation19. Owing to its secondary origins, monitoring and controlling the emissions of the main precursors, VOC and NOx, is crucial. The amount of O3 formed depends on the relative ratio of the precursors. When NOx emissions are abundant, VOC are the limiting species for O3 formation (VOC-limited regime). Meanwhile, NOx emissions govern O3 formation (NOx-limited regime) at low NOx concentrations20,21. However, the O3 production process is influenced by several other factors, such as the competition between VOCs and NOx through HOx chemistry, resulting in a nonlinear relationship between O3 formation and precursor emissions.

Formaldehyde (HCHO) is a secondary product of VOC oxidation, and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) is closely related to NOx owing to the rapid oxidation of NO to NO222. Therefore, HCHO and NO2 have been widely used as proxies for VOC and NOx emissions, respectively, and the HCHO to NO2 ratio (FNR) has been used as an indicator of O3 formation sensitivity23. Different FNR threshold values have been proposed to establish sensitivity regimes, and the methods presented by Duncan et al.24 are among the most commonly used; O3 formation is VOC-limited at FNR < 1, transitional at 1 < FNR <2, and NOx-limited at FNR > 2. However, the threshold values for regime classification are spatially and temporally dependent25,26. Thus, other studies have proposed different threshold values for the transitional regime ranging from 1.5–2.3 to 3–427,28.

With the development of European Global Ozone Monitoring (GOME-1) in 1995, remote sensing began to provide global coverage of HCHO and NO2 column densities in the atmosphere29. In addition, the Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI), launched in 2004, was an improvement because of its finer resolution and daily global coverage30. Since then, several researchers have assessed O3 sensitivity using the HCHO and NO2 column densities from the OMI24,25,31,32,33,34, revealing considerable regional differences and necessitating comprehensive analyses to better assess global trends. Nonetheless, most studies have focused on regions in northern latitudes; therefore, studies of megacities in the tropics and the global south are relatively few, highlighting the need for an extensive analysis to address this disparity, more so when the projections indicate that by 2030, megacities will be concentrated in the less developed regions or the global south1.

This study uses 15 years of daily OMI observations to analyse the HCHO, NO2, and FNR in major urban agglomerations globally and four remote areas with fewer anthropogenic emissions. Monthly O3 reanalysis data from the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS) is used to evaluate O3 trend changes during the same period. Considering that O3 represents a significant global concern16,35, understanding its long-term changes and those from its precursor emissions is essential for assessing the burden of emission-driven O3 on the increased global budget. Correlations among precursor column densities, temperature, and short-wave radiation (SWR) evaluate the influence of climate change on these trends. Therefore, this study aims to provide a synoptic evaluation by performing a robust analysis that integrates several tools for trend estimation. The findings inform the observed changes in areas with the most significant sources of precursors and highest levels of O3 pollution globally, which have yet to be achieved, and serve as support for establishing O3 mitigation strategies on a global scale.

Results and discussion

Global overview of HCHO, NO2, FNR, and O3

Figure 1 shows the global distributions of HCHO, NO2, and FNR in 2005, 2012, and 2019. Changes in the spatial distribution and magnitude of the emissions were evident. The HCHO column densities (Fig. 1a, d, g) showed an apparent increase in the tropics. As biogenic emissions are the primary VOC source globally22, densely forested regions, such as the Amazon and Congo rainforests, have the highest upturns in HCHO. Furthermore, an expansion of high HCHO emission areas in the subtropical and temperate zones was observed, particularly in the northern U.S., Canada, northern Europe, and Russia.

The maps show data in 2005 (a–c), 2012 (d–f), and 2019 (g–i) at a spatial resolution of 0.25° × 0.25°. Masks (white areas) for land–ocean, HCHO values below 7 × 1015 mol cm–2, NO2 values below 1 × 1015 mol cm–2, and FNR values above 6 were applied to facilitate data visualisation. Units for HCHO and NO2 are ×1015 mol cm−2, and FNR is dimensionless. Thin black lines represent country boundaries or shorelines.

In contrast, the spatial distribution of NO2 showed less variability, but significant differences were observed in its magnitude (Fig. 1b, e, h). As shown in Fig. 1, three hotspots were identified: North America, Europe, and East Asia. Moreover, changes in the trends were evident among these regions. North America and Europe exhibited remarkable reductions during the comparison period. However, the regions in East Asia did not show significant changes, and increased levels were observed in the Indian subcontinent. The NO2 emissions in South America and Africa also increased. The FNR also highlights the location of polluted areas (Fig. 1c, f, i). Low-FNR regions translate into high NO2 emissions, whereas high-FNR regions translate into lower NO2 emissions. The U.S. and Europe showed a significant reduction in areas with low FNR owing to significant reductions in NOx emissions. In contrast, the East Asian region still sustains considerable areas with low FNR. The exploratory spatial data analysis (ESDA) showed a strong positive spatial correlation with both HCHO and NO2 (Supplementary Fig. 1), indicating that regions with similar emissions were spatially clustered, with some differences in local distributions.

The O3 levels between 2005 and 2019 showed a significant global increase (Fig. 2). The yearly average anomaly for the 50th percentile revealed that concentrations were higher in 2019 than the long-term average (Fig. 2c), with certain areas reporting an increase of up to 5 ppb. Europe, the Middle East, East Asia, and Southeast Asia are among the regions with the most substantial O3 differences, which aligns with these regions having the highest emissions of precursors.

The maps show anomalies in 2005 (a), 2012 (b), and 2019 (c). The yearly averages were derived from the monthly reanalysis datasets provided by the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service, which were regridded to a spatial resolution of 0.25° × 0.25°. Units are ppb. The maps show regions with positive and negative O3 anomalies relative to the long-term mean. White areas represent water bodies, and thin black lines represent country boundaries or shorelines.

Trend analysis in global megacities and four remote areas

Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 1 show the locations and coordinates of the analysed area for each of the 45 sites. The results of the Mann–Kendall test for trend detection and Sen’s slope test for the magnitude of change between 2005−2019 are shown in Table 1 for HCHO, NO2, and O3. The data were grouped according to the geographical location in the megacities, and the four remote areas were grouped together.

The red areas outline the extension of the analysed dataset in each region. A description of this extension by latitude and longitude is provided in Supplementary Table 1. Thin black lines represent country boundaries or shorelines. The abbreviations assigned to the sites are as follows: Los Angeles (LAX), New York City (NYC), Mexico City (MXC), Bogotá (BOG), Lima (LIM), Sao Paulo (SAO), Rio de Janeiro (RIO), Buenos Aires (BAS), Paris (PAR), London (LON), Moscow (MOS), Istanbul (IST), Cairo (CAI), Lagos (LAG), Kinshasa (KSA), Luanda (LUA), Johannesburg (JHB), Tehran (THR), Lahore (LHR), Karachi (KAR), Delhi (DLH), Mumbai (MUM), Bengaluru (BAN), Chennai (CHN), Kolkata (KOL), Dhaka (DHK), Chengdu (CDU), Chongqing (CQG), Xi’an (XIA), Zhengzhou (ZZU), Beijing–Tianjin (BJN), Wuhan (WHN), Yangtze River Delta (YRD), Pearl River Delta (PRD), Bangkok (BKK), Ho Chi Minh City (HCM), Manila (MNL), Jakarta (JKT), Seoul (SEO), Osaka (OSK), Tokyo (KTO). The abbreviations for the remote areas are Amazon Rainforest (AMZ), Congo Rainforest (CNG), Sahara Desert (SAH), and Great Victoria Desert (GVD).

The HCHO column densities increased significantly in all 45 analysed areas (p < 0.05); the deseasonalised trends are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. Sen’s slope was greater in megacities in South America (Lima, São Paulo, and Rio de Janeiro) and Asia (Chengdu, Tehran, and Xi’an). Dhaka, Bengaluru, Ho Chi Minh, and Jakarta were also among the regions with prominent increases. Most of these megacities are located in the tropics. The Amazon and Congo rainforests also exhibited significant surges. Megacities located in temperate zones, such as New York, London, Moscow, and Tokyo, also showed increased HCHO levels; however, the magnitude of these changes was lower than that in other regions. None of the areas exhibited a decreasing trend.

Based on the NO2 column densities, the increasing, decreasing, and no-trend regions were identified. These differences indicate that megacities in developed economies have significantly reduced NO2 emissions. The most prominent decreases were observed in Los Angeles, Osaka, Tokyo, and London, followed by New York, Moscow, and Paris, as observed in Table 1. In contrast, megacities in developing economies were among the regions with the most significant upturns, namely, Dhaka, Lahore, Tehran, and Kolkata. Remarkably, all megacities with the highest increases were in Asia.

Most regions in China did not display a significant trend, except for the Pearl River Delta and Zhengzhou, which showed decreasing values, and Xi’an, which showed a significant increase. Latin American megacities exhibited mixed trends. Mexico City, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Buenos Aires decreased their NO2 emissions, but it increased in Lima and a non-significant trend was observed in Bogotá. The remote areas showed increasing trends in all cases, with the Amazon and Congo rainforests having the steepest slopes compared with the desert areas of the Sahara and Great Victoria Deserts. The NO2 deseasonalised trend plots for each site are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3.

Descriptive statistics for the FNR from 2005 to 2019 for the 41 megacities are presented in Fig. 4. A clear distinction was observed between megacities in the most industrialised regions, which had the lowest FNRs, and those in developing economies with higher FNRs. Minima (towards VOC-limited) were observed in the U.S., European, and East Asian megacities. Intermediate levels (transitional/NOx-limited) were observed in megacities in Latin American and Western and South Asia. The highest FNR values (strongly NOx-limited) were observed in African and Southeast Asian megacities. The variability was also highest in these regions, possibly because of the higher HCHO observed.

Box plots show the median (horizontal line), 25th and 75th percentiles (boxes), and minimum and maximum (whiskers). The abbreviations assigned to megacities are as follows: Los Angeles (LAX), New York City (NYC), Mexico City (MXC), Bogotá (BOG), Lima (LIM), Sao Paulo (SAO), Rio de Janeiro (RIO), Buenos Aires (BAS), Paris (PAR), London (LON), Moscow (MOS), Istanbul (IST), Cairo (CAI), Lagos (LAG), Kinshasa (KSA), Luanda (LUA), Johannesburg (JHB), Tehran (THR), Lahore (LHR), Karachi (KAR), Delhi (DLH), Mumbai (MUM), Bengaluru (BAN), Chennai (CHN), Kolkata (KOL), Dhaka (DHK), Chengdu (CDU), Chongqing (CQG), Xi’an (XIA), Zhengzhou (ZZU), Beijing–Tianjin (BJN), Wuhan (WHN), Yangtze River Delta (YRD), Pearl River Delta (PRD), Bangkok (BKK), Ho Chi Minh City (HCM), Manila (MNL), Jakarta (JKT), Seoul (SEO), Osaka (OSK), Tokyo (KTO).

Nonetheless, the Mann-Kendall analysis of FNR (Supplementary Table 2) indicates that ozone sensitive trends are shifting towards transitional/NOx-limited conditions in most of the compared sites, primarily owing to the generalised increase in HCHO trends. The greatest magnitude changes were observed in megacities in the tropics and the global south, such as Jakarta and Sao Paulo, owing to their significant elevations in HCHO and decreasing trends in NO2. Megacities in developed economies are also moving towards higher FNR values but at a slower pace. Dhaka and Lagos were the only megacities with significant reductions in their FNR, coinciding with being the megacities with the most significant increases in NO2. Supplementary Fig. 4 shows the deseasonalised trends for FNR in all the analysed sites.

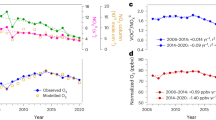

Consistent with the precursor emission trends, the Mann–Kendall test results for O3 in Table 1 revealed increasing O3 in 35 of the 45 studied areas, although the trends were significant in only 25 sites. Interestingly, O3 in most megacities in China decreased throughout the analysis period. However, the O3 seasonal trend decomposition analysis in Supplementary Fig. 5 displays two periods at several sites: 2005–2011 and 2012–2019. Supplementary Table 3 presents the trend and magnitude changes (ppb year−1) for 2005–2011 and 2012–2019.

From 2005 to 2011, O3 remained relatively stable in several megacities, such as Los Angeles, London, Paris, Mexico City, and Seoul, but decreased in most megacities in China. However, from 2012 to 2019, a significant increase was observed at 29 of the analysed sites, with the greatest changes observed in megacities in Asia, such as Tehran, Seoul, and Jakarta. Chinese megacities transitioned from decreasing during 2005–2011 to a significant increasing trend from 2012, with Wuhan and the megacity clusters of the Pearl River Delta and Yangtze River Delta showing the most marked changes. Similarly, megacities in India showed decreasing values from 2005 to 2011 but significant increasing trends from 2012 to 2019.

The four remote areas also showed increased O3 levels from 2012, with the increase being significant only in the Amazon and Congo rainforests, possibly owing to higher biogenic sources of ozone precursors than in the desert areas of the Sahara and the Great Victoria Desert.

Clustering analysis

The elbow criterion determined that four was the most adequate K for the clustering analysis (Supplementary Fig. 6). When considering only the HCHO and NO2 mean column densities, the algorithm clustered the sites into four relationships (Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 4): highest-NO2/mid-HCHO (Cluster 3), high-NO2/mid-HCHO (Cluster 0), lower-NO2/low-HCHO (Cluster 2), and lower-NO2/high-HCHO (Cluster 1). When the FNR was added as a third clustering variable, the algorithm regrouped the sites based on FNR similarities. Due to the inherent spatial and temporal variability of the FNR values that define ozone sensitivity regimes, the analysis did not aim to provide a single universal threshold for each site. However, by clustering regions with similar HCHO, NO2, and FNR, it was possible to identify areas with similar ozone sensitivities. In the clusters, sites displaying the lowest FNR were considered to have VOC-limited conditions, sites with intermediate FNR were considered to have transitional/NOx-limited conditions, and sites with the highest FNR were considered NOx-limited regions.

As shown in Fig. 5, in the upper extreme, the remote areas in the Amazon and Congo rainforests were in Cluster 1, showing the highest FNR (NOx-limited) owing to the highest HCHO and lowest NO2 emissions. At the lower end, megacities with the lowest FNR (VOC-limited) were grouped in Cluster 3 owing to their maximum NO2 emissions. Cluster 0 included megacities with FNR values towards transitional/NOx-limited regimes, while Cluster 2 grouped regions under strong NOx-limited conditions, owing to a higher FNR.

Units for HCHO and NO2 are ×1015 mol cm−2, and FNR is dimensionless. Each point represents a site. Sites are grouped into distinct clusters using the K-means algorithm. Colour coding highlights the different clusters, with clusters indicating regions with similar ozone sensitivities due to similar FNR. The sites assigned to each cluster are as follows: Cluster 0: Mexico City, Jakarta, Buenos Aires, São Paulo, Los Angeles, Dhaka, Mumbai, Kolkata, Karachi, Bengaluru, Chengdu, Istanbul, Chongqing, Rio de Janeiro, Chennai, and Lima. Cluster 1: Amazon rainforest and Congo rainforest. Cluster 2: Lagos, Kinshasa, Bogotá, Sahara Desert, Manila, Bangkok, Ho Chi Minh, Luanda, and Great Victoria Desert. Cluster 3: New York City, Pearl River Delta, Tokyo, Delhi, Johannesburg, Seoul, Cairo, Yangtze River Delta, Beijing–Tianjin, Moscow, Osaka, Lahore, Tehran, Xi’an, Paris, Zhengzhou, London, and Wuhan.

Supplementary Table 5 shows the mean HCHO, NO2, and FNR at each site used in the clustering analysis from 2005 to 2019. When comparing the FNR at each site with the threshold values established by Jin et al. (2020)27 for regime classification, where the transitional regime was at FNR 3-4, it was observed that all sites in cluster 3 would be under VOC-limited conditions, while the rest were under transitional or NOx-limited conditions. Although this classification can provide some insights into the regime of each site, it should be interpreted with caution because of the high uncertainty associated with it due to the spatial and temporal dependency of the established thresholds. In the case of Jin et al.27, the values were determined specifically for urban areas in the US.

Despite the clustered sites having similar FNRs, the NO2 emission trends differed among the grouped megacities. The Seasonal trend decomposition using LOESS (STL) analysis showed significant differences (Supplementary Fig. 3). NO2 trends in megacities towards VOC-limited conditions (Cluster 3) can be divided into those with sharply decreasing NO2 emissions, such as Tokyo (KTO), and those without a clear trend, such as the Beijing–Tianjin (BJN) megacity cluster. Cluster 0, which grouped regions with FNRs towards transitional/NOx-limited regimes, included megacities with decreasing trends, such as Los Angeles (LAX), and those with increasing levels, such as Dhaka (DHK). The Indian megacities of Chennai (CHN), Kolkata (KOL), and Bengaluru (BAN), which were also assigned to this cluster, showed increased NO2 levels. Cluster 2 included megacities with the highest FNRs, indicating strong NOx-limited conditions; all megacities in this group showed increasing NO2 trends.

Through categorising the sites based on their ozone sensitivity, it is possible to find areas that could share similar approaches in their O3 regulations. The regions with the highest O3 levels fell within the same group owing to their similar FNR, which indicates that joint efforts to control air pollution among these regions could be an effective approach to address the issue. Additionally, the clusters highlighted that economic development influences O3 sensitivity; O3 formation is more dependent on the VOC emissions in developed and industrialised economies. Furthermore, their increasing FNR indicates that O3 sensitivity would vary at different levels of development. Thus, the air quality management and policy measures of megacities in developed regions could serve as an example for those in developing economies, which are in transitional/NOx-limited regimes.

Meteorology trends and their correlation with precursor emissions

Figure 6 shows the temperature and SWR anomalies in 2019, relative to the average for 2005–2019. Temperatures increased between 0.5–1.5 °C in most of the planet, and according to NOAA and NASA, 2019 was the second warmest year since records, and the period spanning 2005 to 2019 held nine of the ten warmest years in records36, evidencing the increasing global temperatures due to climate change. SWR showed the most significant increments in the tropics and Southern Hemisphere.

The maps show anomalies for T (a) and SWR (b). The anomalies were derived from the GLDAS reanalysis data at 0.25° × 0.25° resolution. Units are Celsius (°C) for T and watts per square metre (Wm−2) for SWR. The maps depict regions with positive and negative anomalies compared to the long-term average. The white areas represent water bodies, and the thin black lines represent country boundaries or shorelines.

Locally, in the 45 areas, the trend analysis in Table 2 shows that the temperature increase was statistically significant in most regions, with Istanbul, Tehran, and Paris exhibiting the most significant increase. Supplementary Fig. 8 shows the deseasonalised trend of temperatures at the 45 sites; an increasing trend was observed at most of the analysed sites. In contrast, the SWR displayed heterogeneous trends, increasing in some megacities and decreasing in others, as shown in Table 2. Bengaluru, Chennai, and Cairo were the megacities with the most significant increases. Remarkably, the SWR in all megacities in China showed significant declining trends, possibly associated with high levels of particulate matter pollution37.

The precursor column densities and meteorological datasets were grouped according to the clustered sites, and a correlation analysis was performed within the clusters using the yearly values of HCHO, NO2, temperature, and SWR. Figure 7 shows the results of the analysis.

The colour intensity indicates the strength and direction of the correlation. Darker colours represent stronger positive correlations, and lighter colours indicate negative correlations. Sites assigned to each cluster are as follows: Cluster 0: Mexico City, Jakarta, Buenos Aires, São Paulo, Los Angeles, Dhaka, Mumbai, Kolkata, Karachi, Bengaluru, Chengdu, Istanbul, Chongqing, Rio de Janeiro, Chennai, and Lima. Cluster 1: Amazon rainforest and Congo rainforest. Cluster 2: Lagos, Kinshasa, Bogotá, Sahara Desert, Manila, Bangkok, Ho Chi Minh, Luanda, and Great Victoria Desert. Cluster 3: New York City, Pearl River Delta, Tokyo, Delhi, Johannesburg, Seoul, Cairo, Yangtze River Delta, Beijing–Tianjin, Moscow, Osaka, Lahore, Tehran, Xi’an, Paris, Zhengzhou, London, and Wuhan.

In all cases, HCHO showed a strong positive correlation with temperature. The strong correlation observed in Cluster 1, which only included the two remote sites in the Amazon and Congo rainforests, indicates a significant influence of the warming environment on higher biogenic VOC (BVOC) emissions, which is one of the controlling factors of increased HCHO in the Amazon38. Furthermore, under dry conditions, BVOC emissions from soils in the Amazon are known to be comparable in magnitude to those of canopy emissions39, and these BVOC emissions may become even more significant in future years because of more frequent drought episodes.

In the most polluted regions (Clusters 0 and 3), temperature was strongly correlated with HCHO. Anthropogenic emissions are the main source of VOCs in polluted environments, and efforts have been made to reduce these emissions and thus improve air quality. However, these efforts are being offset by increasing biogenic emissions and their greater ozone formation potential, as has been proven by other studies in megacities40,41. The strongest correlation between HCHO and temperature was observed in Cluster 2, which mainly included tropical megacities in less-developed economies in Africa and Southeast Asia. This implies that tropical megacities with fewer regulations for anthropogenic VOC emissions, which also correlate positively with temperature42,43, will see the greatest increases due to the increasing apportionment from biogenic sources caused by climate change. In all cases, SWR showed an insignificant or low correlation with HCHO.

The correlation analysis between NO2 and temperature showed evident differences between the clusters. The remote areas in Cluster 1 showed the strongest positive correlation, suggesting that increasing global temperatures are causing an increase in NOx emissions in non-polluted environments. Considering that biogenic emissions from soils are the most significant source of NOx in remote areas44, the increasing temperatures are causing increased NOx emissions from biogenic sources, whose contribution to the global budget has been demonstrated to be ~15%45. Cluster 2, which grouped cities in less developed economies with lower NO2 emissions but increasing trends, displayed a strong positive correlation, indicating that these NOx increases are attributable to biogenic and anthropogenic contributions.

Clusters 0 and 3, which comprise megacities in developed and rapidly developing economies, showed a negative correlation between NO2 and temperature. The strongest negative coefficient was observed for Cluster 3, which included megacities with the most prominent decreases in NO2. Anthropogenic activities are the main source of NOx in these areas, so the strong negative correlations result from the significant reductions in NO2 achieved by some of these megacities. However, it is noteworthy that soil emissions are also relevant in regions such as the North China Plain46, which encompasses megacities with the highest current NO2 levels in our analysis. Cluster 0 displayed a moderate negative correlation between NO2 and temperature, attributable to the mixed NO2 trends in the megacities in this cluster, including cities with significantly decreased NO2, such as Los Angeles, and megacities with increasing levels, such as Dhaka.

Furthermore, in addition to influencing the precursor emissions, the warming environment also influences the reaction rates of the photochemical processes controlling O3 formation. Globally, rising temperatures lead to increased BVOC emissions as well as higher O3 formation rates owing to increased recycling of NOx from isoprene nitrates formed from BVOC oxidation, as demonstrated by Ito et al. (2009)47. Coates et al. (2016)48 conducted a modelling study that evaluated the effects of temperature on O3 under different NOx conditions, finding that increased VOC oxidation reaction rates and increased peroxy nitrate decomposition rates led to higher O3 production as temperature increased. Similarly, Meng et al. (2023)49 analysed the O3 formation under extreme temperature events in urban areas of China, combining observations with simulated data. Their findings showed that radical cycling is more effective at high temperatures. Therefore, the rate of HO2 + NO significantly increases with temperature, leading to NO removal without O3 consumption, which is a major factor in causing a net O3 accumulation. Moreover, they reported that O3 production duration is longer under extreme heat temperatures than under cold weather.

Overall, the warming climate is causing increased emissions of ozone precursors from biogenic sources while enhancing the photochemical processes that result in O3 production. The above emphasises the need to consider the direct and indirect effects of increasing temperatures in a continuously warming environment where extreme temperature events are expected to rise.

Differences among regions

VOC and NOx emission sources in the Earth’s atmosphere differ significantly. Globally, BVOC accounts for approximately 90% of the total VOC50, and anthropogenic NOx contributes 77% to the global budget51. High HCHO emissions indicate reactive VOC emissions owing to their faster oxidation. Because isoprene (of biogenic origin) is the most abundant reactive VOC globally, the highest differences in HCHO distribution were observed in remote forested areas of South America and Africa. Conversely, the NO2 spatial distribution indicates locations where anthropogenic activity is the primary source of air pollutants. Consequently, NO2 hotspots are located in the most industrialised regions or areas undergoing rapid economic growth.

Clustered megacities with the lowest FNRs (VOC-limited) not only included regions with the most significant NO2 emissions globally but also those with the sharpest NO2 decrease. However, NOx reduction is ineffective in decreasing O3 under VOC-limited conditions, even more so when VOC emissions are also increasing, as indicated by the increasing HCHO trends. Additionally, the O3 issue might worsen in megacities under VOC-limited conditions owing to future vehicle electrification, which will cause a decrease in NOx but increased O3 levels caused by reduced titration52,53. Although significant reductions in NOx emissions could lead to O3 reductions after a shift from VOC-limited to NOx-limited conditions, time and investment in new technologies are required to reach the necessary NOx cuts54. Therefore, focusing on VOC emission control is recommended to decrease the O3 levels in megacities with low FNRs. Owing to the increased relevance of BVOC emissions, choosing the right species for green urban infrastructure should be one of the strategies for decreasing VOC in urban areas under VOC-limited conditions55.

The most significant increase in NO2 levels was observed in Cluster 2, which grouped areas under transitional/NOx-limited regime. In particular, Dhaka and Bengaluru showed the highest relative differences between 2005 and 2019 (Supplementary Table 6). Similarly, Cluster 3 of megacities with the highest FNRs (strong NOx-limited conditions) displayed increasing NOx trends.

In alignment with the spatial distribution of precursor emissions, the megacities with the highest O3 levels are also those with the highest precursor emissions, indicating that emission-driven O3 constitutes the most relevant source of O3 in megacities globally and will continue to do so mainly because of increased VOC and reduced NOx emissions in VOC-limited regions and increasing NOx emissions in regions under transitional/NOx-limited conditions.

Drivers of the observed trends

The trends in precursor emissions can be attributed to different reasons. Globally, the predominant source of NOx emissions is the use of fossil fuels for energy generation, with power plants and vehicles being the most significant sources. Furthermore, the contributions of motor vehicles and power plants are greater in developed economies than in developing economies51. Thus, megacities in developed and industrialised economies have the highest global NOx emissions owing to their higher energy demand56, causing them to be under VOC-limited conditions.

NOx emissions follow a typical environmental Kuznets curve, increasing during the first stage of development and decreasing after reaching a certain point57. Megacities in developing economies have shown increasing NO2 trends, likely due to their ongoing development, which has not yet reached the turning point of decreasing51. Therefore, their VOC-to-NOx emission ratios remain high. However, they are at risk of moving towards VOC-limited conditions if the increasing NOx emission trends continue and their ratio exceeds those of VOC emissions as observed in Dhaka and Lagos in the FNR analysis.

Temperature is strongly correlated with HCHO emissions. All the analysed sites showed increasing HCHO trends. The magnitude of the change was higher in megacities in the tropics and comparable to that in the Amazon and Congo rainforests. In tropical megacities, higher VOC emissions result from both biogenic and anthropogenic sources, partly due to the lack of regulations for the latter. In contrast, efforts to reduce VOC emissions in developed economies are based on anthropogenic sources. However, as global warming continues, biogenic emissions will increase and become more relevant in the O3 formation cycle.

Although global O3 trends indicate a generalised increase, regional differences are apparent and are influenced by different factors. The analysis of precursor emissions and their ratios helps explain these differences. NO2 column densities in China increased from 2005 to 2012 but have since decreased, which has also been confirmed by other studies58,59,60. In contrast, O3 decreased from 2005 to 2011 and increased significantly from 2012 onwards. Nonetheless, the coarse resolution of the data used in our analysis limits the observation of local variations in Chinese megacity clusters. Li et al. (2022)60 reported a continuous increase from 2006 to 2019 of the O3 50th percentile in the Pearl River Delta urban sites, however a significant decrease in regional sites was observed. Due to the spatial resolution limitations, this study cannot resolve these local variations.

The FNR in megacities in China is among the lowest in the analysed regions, and the increase in O3 as NOx decreases is evidence of VOC-limited conditions. However, the FNR showed increasing trends due to reduced NO2 and increased HCHO, which will likely cause a shift towards transitional/ NOx-limited conditions in the coming years. Other studies have reported this change in the ozone sensitivity regime in several regions of China25,61.

In contrast, the high FNR (towards NOx-limited conditions) observed in tropical megacities in Africa and Southeast Asia indicates that the significant increase in O3 trends is caused by increased NOx emissions. Megacities in the Indian region have been increasing their NOx emissions and O3 levels significantly since 2012, indicating a NOx-limited chemical regime from the later period.

In certain analysed megacities such as Los Angeles, Mexico City, Paris, London, Seoul, and Osaka, non-significant changes were observed during 2005–2011 in O3 levels. However, a steep increase has been observed since 2015, which is possibly associated with higher temperatures. According to NOAA, between 2015 and 2019, five of the warmest years on record occurred36. This temperature increase during the later years might exacerbate O3 levels due to increased emissions of precursors of biogenic origin, particularly in areas where the potential to reduce anthropogenic emissions is decreasing62. Additionally, regional transport has influenced the increase in O3 levels, particularly in East and Southeast Asia63,64. Furthermore, vertical transport has been reported to be a relevant factor for persistently high O3 levels in this region, which is also influenced by temperature65,66.

The increased O3 in remote and rural areas has been attributed to increased NOx emissions driven by soil microbes67. The four remote areas analysed showed a positive correlation between temperature and NOx emissions. Hence, because O3 formation in remote areas is strongly NOx-limited, O3 continues to increase with temperature.

OMI data are susceptible to bias caused by factors such as instrument aging. In particular, HCHO retrieval has become noisier over time. Although this issue has been addressed in the latest version of the retrieval algorithm68, it might influence the results presented in this study. Similarly, the reported bias in the CAMS EAC4 reanalysis data69 could influence the O3 trend analysis of megacities in the northern latitudes. Additionally, although the CAMS EAC4 reanalysis dataset provided valuable insights into the regional ozone trends and their precursors across the sites analysed, the inherent spatial resolution was insufficient to resolve the fine-scale spatial heterogeneity observed in extensive urban areas fully. Therefore, caution is warranted when using reanalysis data for site-specific interpretations. Future studies should consider integrating higher-resolution datasets to complement the regional insights provided by reanalysis.

Lastly, satellite and reanalysis datasets comprehensively view atmospheric conditions over large areas. However, they may not fully replicate the detailed variability captured by ground-based observations. Thus, improving the monitoring infrastructure in developing regions is essential for obtaining a better-integrated analysis, which would help validate the accuracy of satellite-based and reanalysis datasets at global scales.

Implications

The analysis showed that O3 increased in global megacities from 2005 to 2019 owing to different trends in precursor emissions and the warming environment. Megacities in most developed economies remain in areas with saturated NOx emissions (towards VOC-limited conditions). Therefore, the increasing VOC and decreasing NOx stagnated or increased the O3 levels. In contrast, megacities experiencing rapid development, located mainly in the tropics, show the most significant increase in NOx emissions. Owing to its transitional/NOx-limited conditions, O3 will likely continue to rise in the coming years.

Increasing temperatures are associated with rising precursor emissions in urban and remote environments. In addition to anthropogenic sources of precursors contributing to O3 formation, biogenic sources will continue to increase their apportionment to the emission-driven O3 formation. Thus, effective regulation requires the consideration of non-anthropogenic sources, which might be challenging but will increase their relevance in a continuously warming environment.

Urban populations are at higher risk of exposure to unhealthy O3 levels. Although less extensive urban areas are desired, projections indicate that megacities will continue to grow, especially in fast-developing economies in the tropics and the global south. Without effective mitigation efforts, O3 will continue to be a critical issue for the public health of inhabitants in the largest urban agglomerations globally, along with the adverse effects of increasing global temperatures.

Given that O3 pollution in megacities has local and global consequences, reducing it will positively impact the health of inhabitants and support greenhouse gas reduction. The results of this analysis support the selection of adequate strategies for reducing O3 based on the long-term trends of its precursor, as inferred from satellite observations.

Methods

Data products

The OMI onboard NASA’s Aura satellite measures backscattered sunlight at UV-visible wavelengths (264–504 nm) with a 2600 km swath. The column densities of trace gases, including HCHO and NO2, were retrieved from the measured irradiances available at four processing levels: Level 0 (L0), Level 1B (L1), Level 2 (L2), and Level 3 (L3). L0 is the raw sensor count, L1 and L2 are time-referenced orbital swaths that include ancillary information such as radiometric counts and geometric calibration coefficients, and L3 products, originating from the extensive screening of L2 data for quality assurance, are allocated in time intervals (monthly or daily) over a latitude–longitude grid covering the entire Earth30,70.

HCHO L3 OMI OMHCHOd products71 were used for analysis. The OMI OMHCHOd data produced by the Harvard and Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory68 provide global, daily averaged, and quality-controlled total columns at a resolution of 0.1° × 0.1°. To derive the HCHO L3 datasets, L2 retrievals were screened to exclude pixels with cloud fractions >30%, high solar zenith angles (>70°), and pixels affected by OMI row anomalies. Validation of the OMI HCHO products showed a strong spatial correlation with aircraft observations. However, a negative bias under high-HCHO conditions and a positive bias under low-HCHO conditions have been reported72,73.

For the analysis of NO2, L3 OMNO2d74 was used. The OMNO2d products generated using the v4.0 OMI NO2 algorithm75 provided daily averaged tropospheric columns at a resolution of 0.25°. Orbital swaths in L2 were mapped onto a latitude–longitude grid to generate L3. The screening criteria for generating OMNO2d products included pixels with cloud fraction <30% and solar zenith angle <85° and excluded pixels affected by row anomalies. Previous studies have shown good agreement among OMI, ground-based, and aircraft observations, with correlation factors of >0.776.

Filtering, infilling, and spatiotemporal averaging procedures were applied to the daily HCHO and NO2 products to reduce the noise and discontinuity. For HCHO, grids with column densities in the range of −0.5 ×1016 mol cm–2 to 10 ×1016 mol cm–2 were used77. The weighted average of the daily products was used to calculate the monthly mean global values. The monthly datasets were filled through bilinear interpolation using eight neighbouring cells. For NO2, following the recommendations in the documentation of the L3 OMNO2d v4, all daily values were included in the averaging procedure, regardless of their sign75. NO2 daily retrievals were used to calculate the monthly mean global values using the same method as with HCHO. Data were processed using the nctoolkit Python package v0.978.

The generated monthly datasets were used to calculate the global FNR. The HCHO products were re-gridded to 0.25° × 0.25° to equal the resolution between the datasets. Considering that the FNR threshold values for regime classification are spatially and temporally dependent, this study focused on analysing the FNR trends instead of establishing a regime classification. Therefore, the results and discussion emphasise the moving FNR trend, either towards VOC-limited conditions for megacities with the lowest FNRs, transitional/NOx-limited conditions for areas with intermediate FNRs, or a strong NOx-limited regime for megacities with the highest FNRs. When mapping the data, masks for land–ocean, HCHO values below 7 ×1015 mol cm–2, NO2 values below 1 ×1015 mol cm–2, and FNR values above 6 were applied to facilitate data visualisation and for driving attention to polluted areas. Maps with non-masked values are shown in Supplementary Fig. 9 for comparative purposes. All mapping was performed using the Python module for the Generic Mapping Tools version 679.

The Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS) provides reanalysis data of atmospheric composition (AC) for different chemical species, including ozone80. The fourth-generation datasets (EAC4) cover 2003 to 2023, providing information in a globally 3-dimensional time-consistent grid with a horizontal spatial resolution of 0.75° at different vertical levels and temporal resolutions. For this analysis, global monthly averaged data at the ground level81 were retrieved from 2005 to 2019. A regridding process was applied to the datasets to equal the grid size to that for HCHO and NO2 (0.25° × 0.25°) using bilinear interpolation. The annual global averages were calculated from the monthly datasets. The validation of EAC4 by comparison with Global Atmosphere Watch data showed improvement compared with the previous versions of the reanalysis, with reported overestimations within 30%, particularly in northern latitudes69.

NASA’s Global Land Data Assimilation System (GLDAS) generates optimal fields for land surface states and fluxes by integrating satellite and ground-based observational data with numerical models82. GLDAS is a global, high-resolution, offline terrestrial modelling system that provides Level 4 global products of surface air temperature and SWR fluxes, among other climate variables. Previous studies have shown that GLDAS products for surface air temperature and SWR accurately estimate variables and correctly reproduce spatial and temporal changes83,84,85 Monthly spatially and temporally continuous products at a spatial grid resolution of 0.25° from 2005 to 2019 were retrieved86 from the GES-DISC NASA website, and annual global averages were calculated from the monthly datasets.

Study sites

The annual averages for HCHO, NO2, and FNR from 2005 to 2019 were mapped to qualitatively evaluate the global changes in the variables. Thereafter, 45 sites were selected for comparison. These chosen sites comprised all urban areas globally, exceeding a population of 10 million (based on Demographia1) and four remote regions. The 41 megacities included three megacity clusters spread across all continents except Oceania. The four remote areas included the Amazon and Congo rainforests, two of the most extensive tropical forests, and two desertic regions in the Sahara and Great Victoria Deserts. The extent of the analysed urban sites was determined based on built-up surface data produced by the Global Human Settlement Layer project of the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre87. The countries of the 41 megacities were categorised as developed and developing based on the World Bank income classification system88. In this study, megacities in high-income countries are considered developed, and those in upper-middle, middle-low, and low-income countries are considered developing (Supplementary Table 7).

Statistical methods

For quantitative analysis, yearly HCHO, NO2, and FNR values were used to evaluate global distributions through exploratory spatial data analysis using the Moran’s Index. At the local level, at the 45 selected sites, trends were assessed using time-series data of monthly values (50th percentile). Missing data in the time series were estimated using linear interpolation. The statistics are described in the following sections.

Moran’s index evaluates spatial autocorrelation in global HCHO and NO2 yearly data, quantitatively measuring whether data are dispersed, clustered, or randomly distributed through a correlation analysis between a variable and its neighbouring values89. This is calculated as follows:

where \(n\) corresponds to the number of spatial units indexed by \({i\; j}\), \(x\) is the variable of interest, \(\bar{x}\) is the global mean, and \({w}_{{ij}}\) is the spatial weight between \({i\; j}.\) The contiguity criterion was applied to create the weighting matrix used to calculate the spatial lags. Moran’s index can take values between –1 and 1. A positive spatial autocorrelation indicates that observations with similar values are clustered, whereas a negative spatial autocorrelation indicates that dissimilar values are close to each other. The local Moran’s index was used to identify local clusters in the global data90. Local analysis indicates the extent of significant spatial clustering by grouping the data according to their similarity to their neighbours. Thus, high–high regions indicate high values clustered around high values, and low–low areas indicate low values neighbouring low values.

The Seasonal Mann–Kendall (SK) and Sens slope tests were applied for trend detection using the monthly time series of all variables at the 45 sites. The SK test is a non-parametric statistic that considers data seasonality by performing a Mann–Kendall test for each evaluated season (monthly in this study) and then comparing the results for the same seasons91. The relative magnitudes of each value were compared with those of all subsequent values. The Mann–Kendall test was performed as follows:

where \(n\) is the sample size and \(y\) are the data points at times \(j\) and \(i\). The test was performed with an alpha of 0.05. Positive \(S\) values indicate an increasing trend and low negative \(S\) indicates a decreasing trend. Kendall’s tau, which measures the correlation between rankings, was used as an indicator of slope monotony (positive when increasing and negative when decreasing). The Theil-Sen estimator, calculated as the median of all slopes between data pairs, was used to measure the magnitude of change (the more significant the slope, the greater the change)92.

Seasonal trend decompositions using LOESS (STL) was performed to complement the SK test. This is a robust method for analysing time-series data with recurring temporal patterns. The method proposed in Cleveland et al. (1990)93 decomposes the time-series data \({y}_{t}\) into three main components as follows:

where \({T}_{t}\) is the changing trend, \({S}_{t}^{\left(i\right)}\) is the seasonal component, and \({R}_{t}\) is the remaining component. This method uses multivariate locally weighted regression (Loess)94 for smoothing operations. STL analysis was performed using the monthly 50th percentile of all variables at the 45 sites using the Statsmodels module in Python95.

The 45 analysed sites were categorised using K-means clustering analysis based on Lloyd’s algorithm96. The ideal number of clusters (K) is determined as the inflection point in the plot of K values as a function of the square of the distance between the points (elbow method). The algorithm minimises the group variance by assigning centroids that group observations with the shortest distance to their mean by optimising the following function57:

where J is the criterion function, \({x}_{{i}}\) is the observed variable, \({C}_{j}\) is the cluster centre, and \(k\) is the number of clusters97. The Scikit-learn Python package98 was used for the analysis, with the K-means ++99 initialisation scheme assigning the centroids. The mean values from 2005 to 2019 for each variable were used for the analysis.

Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to measure the relationship between precursor emissions and the meteorological variables of temperature and SWR. The data were grouped according to the clusters identified by the K-means analysis. The correlations between all variables were evaluated using the annual mean from 2005 to 2019 for the 45 selected sites.

Data availability

All datasets used in this analysis are publicly available. Formaldehyde71, nitrogen dioxide74, temperature86, and short-wave radiation86 data are provided by the Goddard Earth Sciences Data and Information Services Center of NASA and are available for download at https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/. The ground-level ozone reanalysis data81 are provided by the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service and are available for download at https://ads.atmosphere.copernicus.eu/datasets/cams-global-reanalysis-eac4-monthly?tab=download.

Code availability

All analyses and visualisations in this study were conducted using Python, with information on the used libraries detailed in the methods and the codes for the data processing included as supplementary materials.

References

United Nations. The World’s Cities in 2016. Available from www.unpopulation.org, (2016).

Demographia. Demographia World Urban Areas 19th edn. Available from: http://www.demographia.com/db-worldua.pdf, (2023).

Marlier, M. E., Jina, A. S., Kinney, P. L. & DeFries, R. S. Extreme air pollution in global megacities. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 2, 15–27 (2016).

Cohen, A. J. et al. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. Lancet 389, 1907–1918 (2017).

Abbafati, C. et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396, 1223–1249 (2020).

Cakaj, A. et al. Assessing surface ozone risk to human health and forests over time in Poland. Atmos. Environ. 309, 119926 (2023).

Malashock, D. A. et al. Estimates of ozone concentrations and attributable mortality in urban, peri-urban and rural areas worldwide in 2019. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 054023 (2022).

Agathokleous, E., Saitanis, C. J. & Koike, T. Tropospheric O3, the nightmare of wild plants: a review study. J. Agric. Meteorol. 71, 142–152 (2015).

Emberson, L. D. et al. Ozone effects on crops and consideration in crop models. Eur. J. Agron. 100, 19–34 (2018).

Rim, D., Gall, E. T., Maddalena, R. L. & Nazaroff, W. W. Ozone reaction with interior building materials: Influence of diurnal ozone variation, temperature and humidity. Atmos. Environ. 125, 15–23 (2016).

Agathokleous, E., Sicard, P., Feng, Z. & Paoletti, E. Ozone pollution threatens bird populations to collapse: an imminent ecological threat? J. Res 34, 1653–1656 (2023).

Agathokleous, E. et al. Ozone affects plant, insect, and soil microbial communities: a threat to terrestrial ecosystems and biodiversity. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc1176 (2020).

Stohl, A. et al. Evaluating the climate and air quality impacts of short-lived pollutants. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 10529–10566 (2015).

Sicard, P. et al. Trends in urban air pollution over the last two decades: a global perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 858, 160064 (2023).

Gaudel, A. et al. Aircraft observations since the 1990s reveal increases of tropospheric ozone at multiple locations across the Northern Hemisphere. Sci. Adv. 6, 8272–8293 (2020).

Sicard, P. Ground-level ozone over time: An observation-based global overview. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 19, 100226 (2021).

Sicard, P. et al. Ozone weekend effect in cities: Deep insights for urban air pollution control. Environ. Res. 191, 110193 (2020).

Agathokleous, E., Feng, Z. & Sicard, P. Surge in nocturnal ozone pollution. Science 382, 1131 (2023).

Monks, P. S. et al. Tropospheric ozone and its precursors from the urban to the global scale from air quality to short-lived climate forcer. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 8889–8973 (2015).

Sillman, S. The relation between ozone, NO(x) and hydrocarbons in urban and polluted rural environments. Atmos. Environ. 33, 1821–1845 (1999).

Sillman, S., Logan, J. A. & Wofsy, S. C. The sensitivity of ozone to nitrogen oxides and hydrocarbons in regional ozone episodes. J. Geophys Res. 95, 1837–1851 (1990).

Fortems-Cheiney, A. et al. The formaldehyde budget as seen by a global-scale multi-constraint and multi-species inversion system. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 6699–6721 (2012).

Sillman, S. The use of NOy, H202, and HNO3 as indicators for ozone-NOx-hydrocarbon sensitivity in urban locations. J. Geophys. Res. 100, 175–188 (1995).

Duncan, B. N. et al. Application of OMI observations to a space-based indicator of NOx and VOC controls on surface ozone formation. Atmos. Environ. 44, 2213–2223 (2010).

Jin, X. et al. Evaluating a space-based indicator of surface ozone-NOx-VOC sensitivity over midlatitude source regions and application to decadal trends. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 122, 10439–10461 (2017).

Souri, A. H. et al. Revisiting the effectiveness of HCHO/NO2 ratios for inferring ozone sensitivity to its precursors using high resolution airborne remote sensing observations in a high ozone episode during the KORUS-AQ campaign. Atmos. Environ. 224, 117341 (2020).

Jin, X., Fiore, A., Folkert Boersma, K., De Smedt, I. & Valin, L. Inferring changes in summertime surface ozone−NOx −VOC chemistry over U.S. urban areas from two decades of satellite and ground-based observations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 6529 (2020).

Chang, C. Y. et al. Investigating ambient ozone formation regimes in neighboring cities of shale plays in the Northeast United States using photochemical modeling and satellite retrievals. Atmos. Environ. 142, 152–170 (2016).

Burrows, J. P. et al. The Global Ozone Monitoring Experiment (GOME): mission concept and first scientific results. J. Atmos. Sci. 56, 151–175 (1999).

Levelt, P. F. et al. The ozone monitoring instrument. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 44, 1093–1101 (2006).

Ren, J., Guo, F. & Xie, S. Diagnosing ozone-NOx-VOC sensitivity and revealing causes of ozone increases in China based on 2013-2021 satellite retrievals. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 15035–15047 (2022).

Vazquez Santiago, J., Inoue, K. & Tonokura, K. Diagnosis of ozone formation sensitivity in the Mexico City Metropolitan Area using HCHO/NO2 column ratios from the ozone monitoring instrument. Environ. Adv. 6, 100138 (2021).

Inoue, K., Tonokura, K. & Yamada, H. Modeling study on the spatial variation of the sensitivity of photochemical ozone concentrations and population exposure to VOC emission reductions in Japan. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 12, 1035–1047 (2019).

Itahashi, S., Irie, H., Shimadera, H. & Chatani, S. Fifteen-year trends (2005-2019) in the satellite-derived ozone-sensitive regime in East Asia: a gradual shift from VOC-sensitive to NOx-sensitive. Remote Sens 14, 4512 (2022).

Archibald, A. T. et al. Tropospheric ozone assessment report: a critical review of changes in the tropospheric ozone burden and budget from 1850 to 2100. Elem. Sci. Anth. 8, 034 (2020).

NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. Monthly Global Climate Report for Annual 2019. Available from https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/monthly-report/global/201913 (2020).

Luo, H., Han, Y., Lu, C., Yang, J. & Wu, Y. Characteristics of surface solar radiation under different air pollution conditions over nanjing, china: observation and simulation. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 36, 1047–1059 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. The controlling factors of atmospheric formaldehyde (HCHO) in Amazon as seen from satellite. Earth Space Sci. 6, 959–971 (2019).

Bourtsoukidis, E. et al. Strong sesquiterpene emissions from Amazonian soils. Nat. Commun. 9, 2226 (2018).

Gu, S., Guenther, A. & Faiola, C. Effects of anthropogenic and biogenic volatile organic compounds on Los Angeles Air Quality. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 12191–12201 (2021).

Cao, J., Situ, S., Hao, Y., Xie, S. & Li, L. Enhanced summertime ozone and SOA from biogenic volatile organic compound (BVOC) emissions due to vegetation biomass variability during 1981-2018 in China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 2351–2364 (2022).

Mohd Hanif, N. et al. Ambient volatile organic compounds in tropical environments: Potential sources, composition and impacts—a review. Chemosphere 285, 131355 (2021).

Song, C., Liu, B., Dai, Q., Li, H. & Mao, H. Temperature dependence and source apportionment of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) at an urban site on the north China plain. Atmos. Environ. 207, 167–181 (2019).

Vinken, G. C. M., Boersma, K. F., Maasakkers, J. D., Adon, M. & Martin, R. V. Worldwide biogenic soil NOx emissions inferred from OMI NO2 observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 10363–10381 (2014).

Weng, H. et al. Global high-resolution emissions of soil NOx, sea salt aerosols, and biogenic volatile organic compounds. Sci. Data 7, 148 (2020).

Lu, X. et al. The underappreciated role of agricultural soil nitrogen oxide emissions in ozone pollution regulation in North China. Nat. Commun. 12, 5021 (2021).

Ito, A., Sillman, S. & Penner, J. E. Global chemical transport model study of ozone response to changes in chemical kinetics and biogenic volatile organic compounds emissions due to increasing temperatures: Sensitivities to isoprene nitrate chemistry and grid resolution. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 114, D9 (2009).

Coates, J., Mar, K. A., Ojha, N. & Butler, T. M. The influence of temperature on ozone production under varying NOx conditions—a modelling study. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 11601–11615 (2016).

Meng, X. et al. Chemical drivers of ozone change in extreme temperatures in eastern China. Sci. Total Environ. 874, 16424 (2023).

Sindelarova, K. et al. High-resolution biogenic global emission inventory for the time period 2000-2019 for air quality modelling. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 251–270 (2022).

Huang, T. et al. Spatial and temporal trends in global emissions of nitrogen oxides from 1960 to 2014. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 7992–8000 (2017).

Calatayud, V., Diéguez, J. J., Agathokleous, E. & Sicard, P. Machine learning model to predict vehicle electrification impacts on urban air quality and related human health effects. Environ. Res. 228, 115835 (2023).

Hata, H. & Tonokura, K. Impact of next-generation vehicles on tropospheric ozone estimated by chemical transport model in the Kanto region of Japan. Sci. Rep. 9, 3573 (2019).

Vazquez Santiago, J., Inoue, K. & Tonokura, K. Modeling ground ozone concentration changes after variations in precursor emissions and assessing their benefits in the Kanto region of Japan. Atmosphere 13, 1187 (2022).

Sicard, P., Agathokleous, E., De Marco, A. & Paoletti, E. Ozone-reducing urban plants: choose carefully. Science 377, 585 (2022).

Kennedy, C. A. et al. Energy and material flows of megacities. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 5985–5990 (2015).

Bates, J. M., Cole, M. A. & Rayner, A. J. The environmental Kuznets curve: an empirical analysis. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2, 401–416 (1997).

Lin, N., Wang, Y., Zhang, Y. & Yang, K. A large decline of tropospheric NO2 in China observed from space by SNPP OMPS. Sci. Total Environ. 675, 337–342 (2019).

Wang, N. et al. Aggravating O 3 pollution due to NO x emission control in eastern China. Sci. Total Environ. 677, 732–744 (2019).

Li, X. B. et al. Long-term trend of ozone in southern China reveals future mitigation strategy for air pollution. Atmos. Environ. 269, 118869 (2022).

Wang, W. Van Der A, R., Ding, J., Van Weele, M. & Cheng, T. Spatial and temporal changes of the ozone sensitivity in China based on satellite and ground-based observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 7253–7269 (2021).

Lyu, X. et al. A synergistic ozone-climate control to address emerging ozone pollution challenges. One Earth 6, 964–977 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Rapidly changing emissions drove substantial surface and tropospheric ozone increases over Southeast Asia. Geophys Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL100223 (2022).

Cuesta, J. et al. Transboundary ozone pollution across East Asia: Daily evolution and photochemical production analysed by IASI + GOME2 multispectral satellite observations and models. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 9499–9525 (2018).

Qu, K. et al. Rethinking the role of transport and photochemistry in regional ozone pollution: insights from ozone concentration and mass budgets. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 7653–7671 (2023).

Chen, Z. et al. Stratospheric influence on surface ozone pollution in China. Nat. Commun. 15, 4064 (2024).

Romer, P. S. et al. Effects of temperature-dependent NOx emissions on continental ozone production. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 2601–2614 (2018).

González Abad, G. et al. Updated Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory Ozone Monitoring Instrument (SAO OMI) formaldehyde retrieval. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 8, 19–32 (2015).

Wagner, A. et al. Comprehensive evaluation of the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS) reanalysis against independent observations: Reactive gases. Elem. Sci. Anth. 9, 00171 (2021).

Ahmad, S. P. et al. In: William L. Barnes (Ed.), Earth Observing Systems VIII 619–630 (SPIE, 2003).

Kelly Chance. OMI/Aura Formaldehyde (HCHO) Total Column Daily L3 Weighted Mean Global 0.1deg Lat/Lon Grid V003. Greenbelt, MD, USA, Goddard Earth Sciences Data and Information Services Center (GES DISC) (2019). https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/. Accessed 10 Oct 2024.

Zhu, L. et al. Validation of satellite formaldehyde (HCHO) retrievals using observations from 12 aircraft campaigns. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 12329–12345 (2020).

Zhu, L. et al. Observing atmospheric formaldehyde (HCHO) from space: Validation and intercomparison of six retrievals from four satellites (OMI, GOME2A, GOME2B, OMPS) with SEAC4RS aircraft observations over the southeast US. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 13477–13490 (2016).

Lamsal, L. N. et al. OMI/Aura NO2 Tropospheric, Stratospheric & Total Columns MINDS Daily L3 Global Gridded 0.25 degree x 0.25 degree. NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Goddard Earth Sciences Data and Information Services Center (GES DISC) (2022). https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/. Accessed 10 Oct 2024.

Lamsal, L. N. et al. Evaluation of OMI operational standard NO2 column retrievals using in situ and surface-based NO2 observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 11587–11609 (2014).

Lamsal, N. L. et al. Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI) Aura nitrogen dioxide standard product version 4.0 with improved surface and cloud treatments. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 14, 455–479 (2021).

Zhu, L. et al. Long-term (2005–2014) trends in formaldehyde (HCHO) columns across North America as seen by the OMI satellite instrument: Evidence of changing emissions of volatile organic compounds. Geophys Res. Lett. 44, 7079–7086 (2017).

Wilson, R. J. & Artioli, Y. nctoolkit: A Python package for netCDF analysis and post-processing. J. Open Source Softw. 8, 5494 (2023).

Wessel, P. et al. The Generic Mapping Tools Version 6. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 20, 5556–5564 (2019).

Inness, A. et al. The CAMS reanalysis of atmospheric composition. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 3515–3556 (2019).

Inness, A. et al. CAMS global reanalysis (EAC4) monthly averaged fields. Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS) Atmosphere Data Store. https://ads.atmosphere.copernicus.eu/datasets/cams-global-reanalysis-eac4-monthly?tab=download. Accessed 10 Oct 2024.

Rodell, B. M. et al. The global land data assimilation system. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 85, 381–394 (2004).

Slater, A. G. Surface solar radiation in North America: a comparison of observations, reanalyses, satellite, and derived products. J. Hydrometeorol. 14, 401–420 (2016).

Xu, Y. et al. Comparative analysis of three near-surface air temperature reanalysis datasets in inner Mongolia region. Sustainability 15, 13046 (2023).

Ji, L., Senay, G. B. & Verdin, J. P. Evaluation of the Global Land Data Assimilation System (GLDAS) air temperature data products. J. Hydrometeorol. 16, 2463–2480 (2015).

Beaudoing, H. & Rodell, M. GLDAS Noah Land Surface Model L4 monthly 0.25 x 0.25 degree V2.1. Greenbelt, Maryland, USA, Goddard Earth Sciences Data and Information Services Center (GES DISC), Accessed: 10-10-2024. https://doi.org/10.5067/SXAVCZFAQLNO (2020). Available for download at https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/.

European Commission. GHSL Data Package 2023. (2023) https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC133256. Accessed 10 Oct 2024.

Fantom, N. & Serajuddin, U. The World Bank’s Classification of Countries by Income. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/408581467988942234/pdf/WPS7528.pdf (2016).

Moran, P. A. P. Interpretation Stat. Maps. J. R. Stat. Soc. B (Methodol.) 10, 243–251 (1948).

Anselin, L. Local Indicators of Spatial Association—LISA. Geogr. Anal. 27, 93–115 (1995).

Hirsch, R. M., Slack, J. R. & Smith, R. A. Techniques of trend analysis for monthly water quality data. Water Resour. Res. 18, 107–121 (1982).

Sen, P. K. Estimates of the regression coefficient based on Kendall’s Tau. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 63, 1379–1389 (1968).

Cleveland, R. B., Cleveland, W. S., McRae, J. E. & Terpenning, I. A seasonal-trend decomposition procedure based on loess. J. Stat. 6, 3–73 (1990).

Cleveland, W. S. & Devlin, S. J. Locally weighted regression: an approach to regression analysis by local fitting. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 83, 596–610 (1988).

Seabold, S. & Perktold, J. Statsmodels: econometric and statistical modeling with Python. In: Stéfan van der Walt, and Jarrod Millman (Eds.), Proc. 9th Python in Science Conference 92–96 (2010).

Lloyd, S. P. Least squares quantization in PCM. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theor. 28, 129–137 (1982).

Govender, P. & Sivakumar, V. Application of k-means and hierarchical clustering techniques for analysis of air pollution: a review (1980–2019). Atmos. Pollut. Res. 11, 40–56 (2020).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Arthur, D. & Vassilvitskii, S. k-means++: the advantages of careful seeding. In: Harold Gabow (Ed.), SODA’07: Proc. 18th Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms 1027–1035 (Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, 2007).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the support provided by the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO) of Japan (JPNP18016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.V.S., H.H. and K.I conceived the project J.V.S. designed the research and analysed the data J.V.S. and E.M.N. led the data retrieval and processing. J.V.S. wrote the manuscript. K.I. guided and supervised the project. All authors contributed to the discussion and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vazquez Santiago, J., Hata, H., Martinez-Noriega, E.J. et al. Ozone trends and their sensitivity in global megacities under the warming climate. Nat Commun 15, 10236 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54490-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54490-w

This article is cited by

-

Stress-testing the cascading economic impacts of urban flooding across 306 Chinese cities

Nature Cities (2026)

-

A global land daily 10-km-resolution surface ozone dataset from 2013–2022

Scientific Data (2025)

-

Spatial heterogeneity of the Holocene winter temperature in mid-latitude Asia

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)

-

Prediction of coating degradation based on “Environmental Factors–Physical Property–Corrosion Failure” two-stage machine learning

npj Materials Degradation (2025)

-

Associations Between Short-term Exposure to Ambient Air Pollution and Daily Asthma-related Adult Hospital Admissions in Urumqi City, China: a Time Series Study

Water, Air, & Soil Pollution (2025)