Abstract

The surge in global plastic production, reaching 400.3 million tons in 2022, has exacerbated environmental pollution, with only 11% of plastic being recycled. Catalytic recycling, particularly through hydrogenolysis and hydrocracking, offers a promising avenue for upcycling polyolefin plastic, comprising 55% of global plastic waste. This study investigates the influence of water on polyolefin depolymerization using Ru catalysts, revealing a promotional effect only when both metal and acid sites, particularly Brønsted acid site, are present. Findings highlight the impact of Ru content, metal-acid balance, and their proximity on this interaction, as well as their role in modulating the isomerization process, affecting product selectivity. Additionally, the interaction facilitates the suppression of coke formation, ultimately enhancing catalyst stability. A comprehensive techno-economic and life cycle assessment underscores the viability and environmental benefits of the process, particularly in the presence of water. These insights advance understanding and offer strategies for optimizing polyolefin plastic recycling processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global plastic production has surged over the years, escalating from 1.7 million tons in 1954 to a staggering 400.3 million tons in 20221. However, the management of plastic waste predominantly relies on landfill disposal (~75%) or incineration (~14%), with a mere 11% of plastic being recycled2. This concerning trend exacerbates environmental pollution, highlighting the urgent need for sustainable solutions in plastic waste management. In response to these challenges, there is a critical demand for innovative recycling technologies aimed at mitigating environmental risks3. While mechanical recycling has traditionally been utilized, it often leads to downcycling of plastics, compromising their mechanical properties4. Chemical recycling methods, particularly catalytic recycling, are increasingly recognized as promising alternatives5,6,7. Catalytic recycling enables the conversion of plastic waste into drop-in fuels at lower temperatures (250–400 °C) compared to conventional chemical recycling methods (500–800 °C)8. Furthermore, it facilitates selective cleavage of the C-C bonds in plastic wastes, yielding higher yields of liquid fuels compared to conventional methods9. These advantages reduce separation costs and energy inputs, making catalytic recycling an economically and environmentally friendly solution to the escalating concerns surrounding plastic waste management10.

Hydrogenolysis and hydrocracking are prominent catalytic recycling methods extensively studied for their efficacy in upcycling polyolefin plastic waste, which constitutes over half of the global plastic waste due to its short lifecycle9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35. Hydrogenolysis operates at relatively low temperatures, employing Ru or Pt supported on metal oxides such as CeO2, TiO2, Al2O3, SBA-15, and ZrO2, to produce liquid fuels with high yields13,14,15,16,17,18,19. In hydrogenolysis, both C-H bond activation and C-C bond cleavage primarily occur at metal sites, emphasizing the critical role of the geometric structure of Ru and Pt in influencing activity17,18,19,20,21. Conversely, hydrocracking involves C-H bond activation at metal sites and C-C bond cracking at acid sites, typically employing Pt and Ru metals paired with acidic supports such as WO3/ZrO2 or zeolite22,23,24. The metal-to-acid molar ratio, known as the metal-acid balance (MAB), has been reported to significantly influence hydrocracking reactivity9,23,24,25,26.

Previous studies on hydrogenolysis and hydrocracking of polyolefin plastics have mainly been conducted without solvents, but recent research has shed light on the impact of solvents on catalytic activity, particularly in HDPE hydrogenolysis over Ru/C12. Among various solvents tested, such as water, n-pentane, n-hexane, methylcyclohexane, and decalin, only n-hexane and methylcyclohexane were found to enhance HDPE hydrogenolysis activity12. Molecular dynamics simulations have revealed that the interaction between HDPE and solvent molecules changes the conformation of HDPE12. For instance, in n-hexane, HDPE tends to coil, facilitating access to the catalyst’s active sites and increasing activity, whereas, in decalin, HDPE maintains extended conformations, resulting in decreased catalytic activity12. Notably, previous studies have explored the influence of water in the hydrocracking of n-hexadecane36,37,38. The addition of water was found to reduce the hydrocracking conversion of n-hexadecane over H-ZSM-5 due to competitive adsorption between water and reactants on the acidic sites of the zeolite at relatively low reaction temperatures (<350 °C)37. Conversely, water addition was reported to promote the activity of Pd/NaX zeolite in the hydrocracking of n-hexadecane38. Therefore, we hypothesize that water addition enhances the depolymerization of polyolefin plastic waste in the presence of both metal and acid sites.

In this study, we investigate the influence of water on the depolymerization of polyolefin plastics by synthesizing a series of Ru catalysts supported on various materials, including SiO2, SBA-15, γ-Al2O3, TiO2, and zeolite-Y. Our findings reveal that the promotional effect of water is only observed in the presence of both metal and acid sites, particularly Brønsted acid sites, via the metal-acid interaction, leading to an increase in conversion from 51% to 82%. Additionally, we identify MAB and their proximity as crucial factors in facilitating the metal-acid interaction. Notably, the presence of water also influences the degree of isomerization, with a selectivity toward isomers of 1.6% with water compared to 72.1% without water. Through a comprehensive set of characterization techniques, including GC-MS, MS, and pyridine-DRIFTS, we propose a bifunctional depolymerization reaction mechanism, elucidating key distinctions from hydrogenolysis and hydrocracking processes. Techno-economic analysis (TEA) and life-cycle assessments (LCA) further demonstrate that the addition of water positively impacts both economic and environmental performance. This mechanistic insight not only advances our comprehension of catalytic activity but also provides strategies for regulating the degree of isomerization in polyolefin plastic waste catalytic processes.

Results

LDPE depolymerization

The LDPE depolymerization reactions were conducted using various Ru catalysts supported on SiO2, SBA-15, γ-Al2O3, TiO2, and zeolite-Y. In most cases, the addition of water resulted in lower or comparable activity (Table 1, entries 1–14), consistent with previous findings12. However, 5% Ru/zeolite-Y exhibited a notable 16.3%-point increase in conversion, rising from 80.6% to 96.9% after water addition. This increase in conversion was accompanied by a shift in product distribution toward mid-range (C5-C22) alkanes, which are desirable for liquid fuel production (Fig. 1a). Pyridine-DRIFTS analysis revealed that among the various Ru catalysts, only Ru/zeolite-Y exhibited Brønsted acid sites (BAS) (Fig. 1b and Table 2), suggesting a potential association between enhanced activity in the presence of water and BAS.

a Product distributions after LDPE depolymerization reaction over 5% Ru/zeolite-Y. Raw data from GC-FID and GC-TCD spectra are shown in Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15. Reaction conditions: 250 °C, 3 h, 30 bar H2 (at 25 °C), 1.70 g of LDPE (Mn: ~1700, Mw: ~4000), 50 mg of catalyst, 50 mg of water (if needed). b. Pyridine-DRIFTS spectra of Zeolite-Y and various Ru-based catalysts. c Conversion as a function of reaction time. d. Conversion as a function of Water/Catalyst ratio. Unless otherwise mentioned, the reaction conditions are as follows: 250 °C, 1.5 h, 30 bar H2 pressure (at 25 °C), 1.70 g LDPE (Mn: ~1700, Mw: ~4000), 50 mg of Ru/zeolite-Y (Metal: 5 wt%), and 50 mg of water (if needed). e Representative STEM image and Ru particle size distribution histogram of Ru/zeolite-Y. f, g X-ray photoelectron spectra of Ru 3p3/2 of Ru/zeolite-Y before and after reaction with or without water; f 5% Ru/zeolite-Y and g 0.2% Ru/zeolite-Y. h Pore size distribution of fresh and spent Ru/zeolite Y in the presence or absence of water based on the N2 adsorption-desorption. i. Reusability test results of Ru/zeolite Y. Reaction conditions: 250 °C, 3 h, 30 bar H2 pressure (at 25 °C), 1.70 g of LDPE (Mn: ~1700, Mw: ~4000), 50 mg of spent Ru/zeolite Y (Metal: 5 wt%), 50 mg of water (if required). Error bars = standard deviation. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To understand the promotional effect of water over Ru/zeolite-Y, a series of experiments were conducted by changing the reaction conditions. The results revealed a time-dependent enhancement in conversion with the addition of water (Fig. 1c). Additionally, the conversion displayed a bell-shaped curve as a function of the water/catalyst ratio, peaking at a water/catalyst ratio of 1.0 (Fig. 1d). This observation suggests that the presence of water gradually enhances LDPE conversion as the water/catalyst ratio increases, but beyond this optimal ratio, reactivity diminishes, possibly due to a dilution effect39. Further investigations were conducted to explore the influence of reaction temperature, H2 pressure, and additional Ar (Supplementary Table 1).

To further investigate the role of Ru metal, we prepared Ru/zeolite-Y catalysts with weight loadings of 1% and 0.2%. Given the potential influence of Ru dispersion and acid sites on catalytic activity, we conducted analyses to measure particle size using STEM, acid density through NH3-TPD, and BAS/LAS ratio via pyridine-DRIFTS (Table 2, entries 7, 8 and Fig. 1e). Similar particle size and acidic properties were observed, ruling out the potential influence of Ru dispersion and acidic properties of Ru/zeolite-Y on catalytic activity. STEM analysis of spent catalysts was further conducted to investigate the particle size changes. The spent Ru/zeolite-Y exhibited a slight increase in mean particle sizes with and without water (Supplementary Fig. 3), suggesting that water did not strongly contribute to aggregation. Furthermore, XPS was conducted to determine the electronic structure of Ru/zeolite-Y. The binding energy of spent Ru/zeolite-Y remained constant at 461.7 eV regardless of water and weight loadings (Fig. 1f, g), a characteristic indicative of pure metallic states of Ru (Ru0)40. This suggests that the electronic state of Ru catalysts remained unchanged after the reaction, irrespective of the presence of water.

With evidence that both geometric and electronic structures of Ru catalysts remained similar regardless of the presence of water, we conducted BET analysis to characterize the pore structure of the fresh and spent catalysts. While the general shape of the hysteresis loop remained consistent (Supplementary Fig. 4), the pore size distribution of the spent catalyst shifted to smaller diameters, particularly in the absence of water (Fig. 1h). This shift suggests increased coke formation during the reaction, as evidenced by a decrease in both surface area and pore volume (Supplementary Table 2)41. This inhibition of coke formation was further confirmed by post-calcination characterization, where the presence of water was essential for restoring the catalyst’s performance (Supplementary Table 2). To further assess the stability of the catalyst under different conditions, we conducted control experiments without LDPE at 300 °C for 24 to 48 hours. These experiments showed that the zeolite structure remained largely intact, with only minor reductions in surface area and pore volume for the 5% Ru/zeolite-Y, regardless of water exposure (Supplementary Table 3). The preservation of the zeolite structure can be explained by the low n/n0 ratio in our experiments. The ratio of the amount of water present in the zeolite plus the added water to the molar number of the saturated state (n/n0) was calculated to be 0.056, well below the critical threshold of 0.3 known to cause zeolite crystal structure collapse42. Additionally, the presence of Ru metal helped mitigate structural changes in the zeolite.

To quantify the amount of coke deposited during the reaction, TGA was conducted15,26. The weight loss was approximately 12% following the reaction with water, contrasting with about 22% without water, providing compelling evidence that water suppresses coke formation (Supplementary Fig. 9). Additional TGA results of 0.2% Ru/zeolite-Y and visual comparisons of the catalysts showed the similar trend, reinforcing our conclusions (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11). This observation aligns with earlier findings in methane reforming, where coke formation was higher without water (dry reforming of methane) than with water (steam reforming of methane)43. Further analysis revealed that the coke removed by water was primarily in the form of CO2, with the amount of CO2 extracted increasing with both reaction time and water/catalyst ratio (Supplementary Fig. 12).

The reusability test was performed to investigate the impact of coke deposition on the reactivity of Ru/zeolite-Y in LDPE depolymerization (Fig. 1i). Upon reusing Ru/zeolite-Y with water, the initial conversion was 96.9%, with subsequent 1st and 2nd regenerations yielding conversions of 94.5% and 90.1%, respectively (Table 1, entries 15–18). These results suggest that the reactivity of the catalyst remained nearly unchanged in the presence of water. In contrast, when the reaction was conducted without water, a significant decrease in conversion was observed, dropping from 80.6% to 31.8% after the 1st regeneration and 24.1% in the 2nd. These findings indicate that the addition of water in LDPE depolymerization using Ru/zeolite-Y suppresses coke formation, resulting in improved reactivity and reusability of the catalyst.

Role of acid sites

To understand how water enhances reactivity and reusability, a control experiment was conducted with pyridine. Interestingly, the poisoned Ru/zeolite-Y catalysts exhibited a negligible promotional effect with water (Table 1, entries 19 and 20), different from the fresh catalyst. Additionally, the product distribution of poisoned catalysts remained similar regardless of water (Fig. 2a), unlike the fresh catalyst (Fig. 1a). These findings strongly suggest the involvement of acid sites in LDPE depolymerization for the promotional effect of water. Given that pyridine poisons both Lewis acid sites (LAS) and BAS26, pyridine-DRIFTS, and NH3-TPD analyses of spent Ru/zeolite-Y were performed to discern the role of the BAS. The peaks at 1450 cm-1 (LAS) and 1540 cm-1 (BAS) were present over Ru/zeolite-Y before and after the reaction with water (Fig. 2b). However, the pyridine-DRIFTS spectra of the spent catalyst without water showed a noticeable decrease in the peak at 1540 cm-1. Indeed, the BAS of the catalyst decreased from 185.0 μmol/g to 44.1 μmol/g after the reaction without water (Supplementary Table 7). Conversely, the BAS was maintained at 160.8 μmol/g after the reaction with water. This trend was also observed for the 0.2% Ru/zeolite-Y catalyst. The substantial decrease in the BAS after the reaction without water can be attributed to coke deposition on the BAS during the reaction without water23,26. This also suggests that the reaction predominantly occurs at the BAS rather than the LAS.

a Product distributions after the LDPE depolymerization reaction over pyridine-poisoned 5% Ru/zeolite-Y. b Pyridine-DRIFTS spectra of Ru/zeolite-Y before and after the reaction or controlled reaction in the presence or absence of water. The spent catalyst was obtained under the following conditions: 250 °C, 12 h, 30 bar H2 pressure (at 25 °C), 50 mg of Ru/zeolite-Y (Metal: 5 wt%), 50 mg of water (if required), 1.70 g of LDPE (Mn: ~1700, Mw: ~4000). LDPE was not added in the controlled reaction. c–k Product distributions after LDPE depolymerization reaction. Reaction over: c 5% Ru/zeolite-Y (Si/Al=30), d 5% Ru/zeolite-Y (Si/Al=80), e 5% Ru/zeolite-Y (2.5 mg Ru), f 1% Ru/zeolite-Y (0.5 mg Ru), g Physical mixture of 1% Ru/zeolite-Y and zeolite-Y (0.5 mg Ru), h 1% Ru/zeolite-Y (2.5 mg Ru), i 0.2% Ru/zeolite-Y (2.5 mg Ru), j Physical mixture of 5% Ru/SiO2 and zeolite-Y (2.5 mg Ru), and k 5% Pt/zeolite-Y. l Isomer selectivity with different catalysts. Reaction conditions: 250 °C, 3 h, 30 bar H2 (at 25 °C), 1.70 g of LDPE (Mn: ~1700, Mw: ~4000). Other conditions are shown in Table 1. Error bars = standard deviation. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To discern whether the decrease in the BAS was caused by coke deposition during LDPE depolymerization or by catalyst structure deformation at the reaction temperature, additional control experiments were conducted without LDPE under identical reaction conditions. The pyridine-DRIFTS spectra of control experiments with and without water (Fig. 2b) remained similar to that of the fresh catalyst (Fig. 1b), indicating that the loss of the BAS without water is associated with coke formation during LDPE depolymerization. This suggests that the reduction of the BAS coincides with coking occurrences. To further evaluate the relationship between reactivity and acid strength, we synthesized and tested catalysts with SiO2/Al2O3 ratios of 30 and 80, different from our reference catalyst with a SiO2/Al2O3 ratio of 60. All catalysts showed similar levels of conversion enhancement (Table 1, entries 19-22). However, differences in isomer selectivity were observed based on the concentration of the BAS, particularly in the absence of water (Table 2, entries 9, 10). High Ru loading generally led to reduced isomer selectivity, with selectivity decreasing further to 3.35%, 1.97%, and 1.11% as the SiO2/Al2O3 ratio increased to 30, 60, and 80, when water was absent. In contrast, isomer selectivities remained relatively stable, ranging from 1.08% to 1.51%, in the presence of water, regardless of the SiO2/Al2O3 ratio (Fig. 2c–e). This behavior indicates that selectivity is influenced by both the presence of water and the density of BAS, which varies with the SiO2/Al2O3 ratio.

Metal-acid interaction in the presence of water

Considering the involvement of Brønsted acid in LDPE depolymerization, additional experiments were performed to investigate how water influences this process (Table 1, entries 23-34). As shown in Figs. 2e, 5% Ru/zeolite-Y exhibited an enhanced conversion of 96.9% in the presence of water, compared to 80.6% in the absence of water after a 3-hour reaction. Conversely, 1% Ru/zeolite-Y exhibited negligible differences in conversion, with conversions of 34.3% with water and 35.3% without, indicating negligible promotional effect of water (Fig. 2f). To understand this further, additional zeolite-Y was added to increase the number of acid sites. However, despite this addition, no significant water-induced enhancement occurred for 1% Ru/zeolite-Y (Fig. 2g). When the quantity of 1% Ru/zeolite-Y was adjusted to match the Ru content of 5% Ru/zeolite-Y while keeping acid sites constant, a notable increase in conversion was observed—from 56.8% to 94.5% with water (Fig. 2h). A similar trend was observed for 0.2% Ru/zeolite-Y, where conversion increased from 54.5% to 82.8% with water (Fig. 2i). These findings highlight the importance of MAB in the promotional effect of water.

To explore the influence of proximity between metal and acid sites, experiments were performed with a physical mixture of 5% Ru/SiO2 and zeolite-Y (Fig. 2j). The mixture exhibited a negligible promotional effect, suggesting the pivotal role of metal-acid proximity in inducing the promotional effect of water via the metal-acid interactions in LDPE depolymerization. Additional experiments using Pt/zeolite-Y (Fig. 2k) revealed minimal enhancement in conversion, but changes in isomer selectivity were observed (Fig. 2l), consistent with previous findings44. This can be attributed to Pt’s relatively lower C-C bond dissociation ability compared to Ru. Previous studies have shown that the ability to dissociate C-C bonds follows the order Ru > Rh > Ir > Pt45, which may explain why Pt, despite interacting with water and acid sites to modify selectivity, does not significantly enhance conversion—similar to the effect seen with insufficient Ru amounts (0.5 mg, Fig. 2f).

Furthermore, notable variations in product distribution were observed with and without water. The product distribution remained relatively consistent with water; however, significant variations were observed depending on the Ru loading without water, particularly in catalysts with lower Ru loading (Supplementary Figs. 25 and 26). Considering that hydrocracking reactions typically produce shorter alkanes (C3-C4) in the presence of dominant acid sites and longer alkanes (C21+) or methane in the presence of prevalent metal sites23,24,26, this observation suggests that reactions primarily occur at Ru sites rather than zeolite sites with water, regardless of the Ru loading.

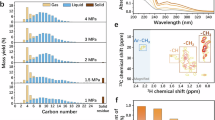

Mechanistic insights

To elucidate the influence of water on the reaction mechanism, we employed deuterated water (D2O) alongside regular water (H2O). The results revealed a similar product distributions with both H2O and D2O (Fig. 3a). Further analysis using mass spectrometry (MS) showed the absence of HDO and D2O peaks in the catalyst after reaction without water, while HDO peaks appeared in the catalyst after reactions with D2O, indicating the incorporation of deuterium atoms (Supplementary Fig. 27). Additionally, isotopic composition analysis of gas products (Fig. 3b, c) showed a selectivity of 0.3% for substituted deuterium atoms without water, which increased to 4.1% with D2O, suggesting the replacement of some hydrogen atoms by deuterium. These results support the hypothesis that water acts as a proton donor in the reaction38. Furthermore, MS and GC-MS analyses were conducted to examine the effect of water on the degree of isomerization reaction. Using n-dodecane as a surrogate, we aimed to elucidate the role of acid sites, crucial for isomerization46. Comparing reactions with and without water over 0.2% and 5% Ru/zeolite-Y catalysts (Fig. 3d–f), we observed significant differences in isomer selectivity. Specifically, the selectivity for isomers over 0.2% Ru/zeolite-Y decreased from 72.1% without water to 1.6% with water (Fig. 3e, f), indicating a profound shift in the reaction pathway in the presence of water, especially with low metal loading. Conversely, reactions over 5% Ru/zeolite-Y exhibited an isomer selectivity of 1.2% without water and 3.0% with water, indicating a dominant role of metal sites in these conditions regardless of the presence of water (Fig. 3d–f). This suggests that water alters the reaction pathways in LDPE depolymerization, potentially by promoting the protonation of carbon cations rather than skeletal rearrangement, leading to the predominant production of linear alkanes. Additionally, the detection of aromatic compounds via acid sites chemistry indicates a complex interplay of reaction mechanisms30.

a–c LDPE depolymerization reaction over 5% Ru/zeolite-Y. a Detailed carbon distributions after 3 h reaction with H2O or D2O (b–c). Selectivity of isotopes in gaseous products after 12 h reaction: b After the reaction without water, and c After the reaction with D2O. Reaction conditions: 250 °C, 30 bar H2 (at 25 °C), 1.70 g of LDPE (Mn: ~1700, Mw: ~4000), 50 mg of 5% Ru/zeolite-Y, 50 mg of H2O or 55.6 mg of D2O (if required). d–f Dodecane decomposition reaction over: d 5% Ru/zeolite-Y, e 0.2% Ru/zeolite-Y, f total normal and isomer yield. Reaction conditions: 250 °C, 3 h, 30 bar H2 (at 25 °C), 1.0 g of n-Dodecane, m(Ru): 2.5 mg, Water/Catalyst ratio: 1 or 0. Error bars = standard deviation. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Relationship between metal-acid balance and reaction pathways

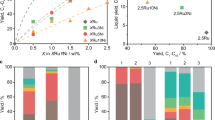

Given that MAB is widely recognized as a crucial factor in small alkane hydrogenolysis or hydrocracking24,47,48,49, we incorporated MAB as a classification criterion. An acid-catalyzed reaction tends to slow at a high MAB, whereas a low MAB shifts the rate-determining step toward hydrogenation/dehydrogenation reactions. Reflecting these shifts, the molar ratio of C21+/C4-6 was reported to increase with an elevated MAB24 (Fig. 4a). To illustrate this, we plotted the molar ratio of C21+/C4-6 using Ru/zeolite-Y with varying Ru loading. In alignment with prior findings, the molar ratio of C21+/C4-6 rises with increasing MAB without water (Fig. 4a)24. However, results with water show a noticeable difference in product distribution, implying a mechanism distinct from hydrogenolysis and hydrocracking. For example, the yield of gasoline is highest without water, while the yield of diesel and lubricant peaks with water over 0.2% Ru/zeolite-Y (Fig. 2i). In addition to the C21+/C4-6 ratio, the ratio of the average carbon number of the gas and liquid phases was influenced by MAB24. Similar to the previous findings24, the Cliq/Cgas ratio of the average carbon number without water increases with increasing MAB (Fig. 4b). However, even with similar MAB levels, the distribution differs significantly with water, resulting in different Cliq/Cgas. Therefore, we consider both the MAB and the all-product distribution to categorize the depolymerization of polyolefins into three groups (see details in Supplementary Note 1).

a Molar ratio of C21+ to C4-6 products as a function of MAB, ref. 24. b Average carbon number ratio of the liquid (C5–C35) to gaseous phase (C1–C4) as a function of MAB, ref. 24. c Reactivity-mechanism map of the PE depolymerization reaction. d Average product distribution. e Color of products after PE depolymerization reactions. Reaction conditions: 250 °C, 3 h, 30 bar H2 (at 25 °C), 1.70 g of PE (Mn: ~1700, Mw: ~4000), 50 mg of water (if required). Error bars = standard deviation. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Considering both MAB and the corresponding ratios, a lower MAB and a lower Cliq/Cgas correspond to reactions closer to hydrocracking (see full details in Methods). Conversely, a higher MAB and a higher Cliq/Cgas align with reactions closer to hydrogenolysis, with moderate cases being classified as bifunctional depolymerization reactions (Fig. 4c). The mechanisms of each reaction categorized in Fig. 4c are described in Fig. 59,22,24,50,51. The distribution shown in Fig. 4d represents the average of all reaction results. In instances of high Ru loading and low concentration of acid sites, hydrogenolysis is the dominant reaction. This reaction proceeds through the dehydrogenation of the reactant, followed by the cleavage of the C-C bond at the metal site, as illustrated in the Fig. 5a pathway (II). Although the introduction of water may facilitate intermediates to undergo protonation (Fig. 5a, II-ii), β-scission does not occur due to the absence of, or few, acid sites even in the presence of water. Consequently, the hydrogenolysis reaction over Ru catalysts primarily produces methane (Figs. 5b and 4d). The Ru/zeolite-Y catalyst, subjected to pyridine poisoning, is also categorized as a hydrogenolysis reaction due to the absence of acid sites, specifically because C-C bond dissociation occurs solely on Ru.

In instances of low Ru loading and a high concentration of acid sites, the primary reaction is hydrocracking. This process involves dehydrogenation at the metal site, followed by protonation at the acid sites, leading to skeletal rearrangement for isomerization. The protonated intermediate then undergoes β-scission to cleave the C-C bond at the acid site (Fig. 5a, pathway I). Notably, the β-scission rates of the reaction intermediate differ based on the skeleton structure, with deep skeletal rearrangement showing the fastest rate, while reactions lacking branches are slower or forbidden (Fig. 5a, I-iv)9. As previously shown in Fig. 4d–e, the quantity of iso-C12 is relatively larger than other Cn(<12) products in both 0.2% and 5% Ru/zeolite-Y, irrespective of water. This is mainly associated with the rate-determining step, β-scission, in LDPE depolymerization (Fig. 5). Alkanes undergo protonation after dehydrogenation, leading to isomerization through skeletal rearrangement, followed by conversion to a short alkane via β-scission. In this series of steps, the β-scission reaction works as the rate-determining step; thus, the preceding skeletal rearrangement step produces a larger amount of iso-C12. Interestingly, products obtained from hydrocracking exhibit a yellow hue, signifying the formation of isomeric products, as previously reported (Fig. 4e)32.

In cases where the MAB falls within an intermediate range, it is categorized as bifunctional depolymerization (Fig. 4c). While the roles of the metal and acid sites are well-defined in hydrogenolysis and hydrocracking reactions, bifunctional depolymerization involves the simultaneous occurrence of hydrocracking and hydrogenolysis reactions. Essentially, the cleavage of C-C bonds occurs concurrently at both the metal and acid sites, resulting in superior activity compared to other mechanisms (Fig. 4c). For instance, catalysts with relatively low MABs, such as 0.2% and 1% Ru/zeolite-Y, exhibited enhanced reactivity in the presence of water compared to its absence due to the bifunctional depolymerization mechanism. Water can protonate or deprotonate intermediates at the metal or acid site, as illustrated by the two-way arrow highlighted in green in Fig. 5a. This process facilitates the simultaneous dissociation of C-C bonds at both the metal and acid sites, resulting in an enhancement in PE depolymerization.

Application to various plastic wastes

Understanding the influence of water on reaction mechanisms, we conducted depolymerization reactions using substances with varying degrees of branching. The product distribution exhibited notable differences between the more branched substance (PP) and the less branched one (HDPE) (Fig. 6a, b). In substances with more branching, such as PP, β-scission occurs more rapidly due to the stabilization provided by neighboring carbons9, allowing it to occur without the need for skeletal rearrangement. Conversely, in substances like HDPE with fewer branches, skeletal rearrangement becomes essential for β-scission. Additionally, water plays a significant role by facilitating the protonation or deprotonation of the carbon cation to achieve a more stable state (Fig. 6a). In the presence of water, HDPE predominantly produced methane due to the dissociation of terminal C-C bonds at Ru sites rather than undergoing skeletal rearrangement. Conversely, PP exhibited a more stable carbon cation skeleton in the presence of water, leading to the dissociation of internal C-C bonds rather than terminal ones. This resulted in higher yields of high-value materials in the gasoline and jet fuel range compared to short alkanes of C3-6.

Depolymerization reaction over 0.2% Ru/zeolite-Y both with and without water of a PP, b HDPE, c Commercial LDPE, and d LDPE bottle. Reaction conditions: 300 °C, 9 h, 30 bar H2 (at 25 °C), 1.70 g of reactant, 2.5 mg of Ru, and a water/catalyst ratio of 1.0 for the reactions with water. Detailed reaction results are shown in Supplementary Table 8. Error bars = standard deviation. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The promotional effect of water was also evident involving commercial LDPE and LDPE bottles. For commercial LDPE, the gas yield decreased from 32.2% without water to 2.5% with water, while the diesel yield increased from 0.7% without water to 34.3% with water (Fig. 6c). Similarly, for LDPE bottles, the gasoline yield decreased from 34.1% without water to 8.8% with water, while the diesel yield increased from 9.2% without water to 21.1% with water, reflecting a noticeable shift in product distribution (Fig. 6d). This shift highlights the practical feasibility of directing the depolymerization pathway toward the desired carbon range products, representing a significant advancement in plastic waste upcycling. Additionally, the observation of CO/CO2 peak only in the presence of water indicates that water not only influences product distribution but also facilitates the removal of coke (Supplementary Fig. 29).

Techno-economic analysis

To assess the economic viability of implementing a real commercial-scale process utilizing a 0.2% Ru/zeolite-Y catalyst, a comprehensive techno-economic analysis was performed52,53,54. It was found that the LDPE fractionation, both with and without water, emerged as a major cost-driver mainly due to high material expenses and high capital cost, resulting from multiple reactors to continuously depolymerize LDPE (Figs. 7a and 7b). Specifically, approximately 62.1% and 66.3% of the total costs occurred from purchasing waste LDPE, respectively. Notably, while the same amount of LDPE (240 tons/day) was supplied in both scenarios, the relatively lower contribution of LDPE cost in the process without water can be primarily attributed to a higher hydrogen consumption (192.0 kg/hr)55. The reaction with water requires relatively less hydrogen (94.6 kg/hr), primarily because of the production of heavier carbon-range products (C22+). However, to further enhance the value of the products, particularly those in the gasoline or diesel range, an additional fluidized catalytic cracking subsystem ($0.49/GGE) is required in the process with water to convert C22+ into more valuable fuel products, leading to an increase in the total capital investment compared to the process without water ($114.7 × 106 vs. $132.0 × 106) (see Supplementary Table 12 for detailed capital cost). However, when considering the cost per gasoline gallon eq. (GGE), the process of utilizing water incurs a higher material cost ($3.10/GGE) mainly due to LDPE ($2.90/GGE) and hydrogen ($0.19/GGE). This higher cost is attributed to the lower production rate (1978 gal/hr vs. 2941 gal/hr) despite slightly higher energy content (30.4 kWh/gal vs. 28.7 kWh/gal) compared to that process without water (28.7 kWh/gal, 2941 gal/hr). The black arrows representing carbon flows confirm that when LDPE’s carbon content is 100%, the carbon efficiency of gasoline is 75% for processes without water and 54% for the process with water. Notably, although the carbon efficiency of gasoline in the process with water is lower than that in the process without water, the total carbon efficiency, considering both gasoline and diesel, is higher in the process with water (94%) than in the process without water (87%).

Cost contributions for a process without water and b process with water. Carbon flows (black arrows) and major three heat networks (dashed arrows) are represented. The storage ($0.04/GGE and $0.05/GGE, respectively) and utility ($0.01/GGE and $0.01/GGE, respectively) subsystems are not represented. c Comparison of economic performance between processes with and without water. Detailed economic parameters and results are specified in Supplementary Tables 11 and 12. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The economics of the process with water is improved primarily due to higher carbon efficiency, which increases production rates and, in turn, boosts product revenues, including byproduct credits ($2.97/GGE). This occurs despite the higher total cost compared to the process without water ($5.13/GGE vs. $3.63/GGE). Specifically, the production costs, including LDPE and hydrogen costs, are the most significant factors, accounting for 75.8% and 72.1%, respectively. The MSP of gasoline for each process is determined by subtracting the income generated from diesel and electricity from the overall cost54,56,57. Consequently, the MSP of the process with water is $2.16/GGE, whereas for the process without water, it is $2.95/GGE, indicating the economic advantage of the process with water. The MSP of the processes without and with water can be increased by 10.2% to $3.25/GGE and by 9.3% to $2.36/GGE, respectively, due to changes in the hydrogen price—which is one of the most influential parameters on the MSP—from $3640/ton to $7280/ton. Considering the conventional retail gasoline price range ($1.66/GGE - $4.84/GGE), both processes are market-competitive even with a higher discount rate (20%) compared to a typical rate in the nth plant assumption (10%)54,58. In conclusion, despite the increased overall cost, the addition of water results in a 26.8% reduction in MSP, making it the more economically preferred.

Life-cycle assessment

To quantitatively evaluate the environmental impacts of the processes without water and with water, a life-cycle assessment (LCA) was conducted following the guidelines provided by ISO 14040 and 1404459,60,61,62. Based on the environmental impacts of one gallon of conventional gasoline production (100%), the relative environmental impacts of the processes are represented in Fig. 8a. Unlike conventional gasoline, the environmental impacts of gasoline produced from both processes yield negative values, indicating environmental benefits. The environmental impacts of the process without water range from -2% to -42%, while those of the process with water range from -10% to -103%. This implies that the process with water offers both economic and environmental advantages. The beneficial impacts of the process with water are derived from the production of diesel. As shown in Fig. 8b, the environmental impacts attributed to input materials and energy in the process with water are offset by the production of diesel, while the process without water mitigates the environmental impacts via the production of diesel and electricity. Notably, these coproducts can substitute conventional counterparts that largely rely on fossil fuels. Consequently, the production of coproducts from these processes contributes to reducing the reliance on fossil fuels, resulting in environmentally favorable outcomes.

a An environmental impact radar chart for the major categories, and b heatmaps of environmental contributions. The major categories include global warming potential (GWP), stratospheric ozone depletion (SOD), terrestrial acidification (TA), marine ecotoxicity (MEu), fossil resource scarcity (FRS), and fine particulate matter formation (FPMF). Additional life-cycle assessment (LCA) results are specified in Supplementary Table 13. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Furthermore, the process with water exhibits a larger offset impact in diesel production due to its higher production rate compared to the process without water. Additionally, the analysis revealed that the disposal of boiler slag, generated during the incineration of byproducts such as C22+, is the most environmentally intensive component. The major environmental impacts originated from disposal of residue are freshwater eutrophication (FWEu), freshwater ecotoxicity (FWEc), marine ecotoxicity (MEc), human carcinogenic toxicity (HCT), and human non-carcinogenic toxicity (HNCT) of both processes, respectively. Especially, disposal of residue accounts for 96% and 94% of HCT of both processes. This significant influence of disposing of residue is attributed to the cement used for its solidification.

Discussion

The catalytic depolymerization of polyolefins presents a promising route for recycling plastic waste in terms of process economics and sustainability. In this study, we found the significant impact of water addition on plastic depolymerization, elevating the yield of valuable liquid fuels from 41.8% to 71.0% and effectively suppressing coke formation to preserve catalyst activity. Through our investigation into reaction mechanisms with water, we categorized reactions into three groups based on catalytic properties and product distribution including hydrogenolysis, hydrocracking, and bifunctional depolymerization. Among these, the proposed bifunctional depolymerization reaction demonstrated the highest activity, where the cleavage of C-C bonds occurs simultaneously at the metal and acid sites. This promotional effect of water extends across various waste plastics, promising implications for the recycling of plastic waste. Moreover, the addition of water not only enhances carbon efficiency, improving economic and environmental performance based on TEA and LCA analysis, but also increases conversion to gasoline and diesel. This results in a 26.8% reduction in the MSP of gasoline and enhances economic efficiency. Additionally, the increased production rate achieved by adding water substantially mitigates environmental impacts and reduces reliance on fossil fuels, thereby replacing diesel derived from fossil fuels. This opens up the possibility to advance the entire chemical recycling of plastic waste, while simultaneously addressing environmental pollution caused by plastic waste.

Methods

Chemicals and materials

All chemicals were analytical or higher grade and used as received without further treatment. RuCl3·xH2O (product no. 11043) was purchased from Alfa Aesar. SiO2 (product no. 236845) of Davisil grade 646, SBA-15 (product no. 806862), γ-Al2O3 (product no. 544,833), and TiO2 (product no. 634662) of P25 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Zeolite Y with SiO2:Al2O3 ratios of 30:1 (product no. 045870), 60:1 (product no. 045871), and 80:1 (product no. 045872) was purchased from Alfa Aesar. PE (Mn: ~1700, Mw: ~ 4000, product no. 427772) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich, commercial LDPE was purchased from Hanwha Total (product code: 530 G), and LDPE bottle was purchased from Korea Ace Scientific. Mesitylene (product no. 12558) was purchased from Acros Organics, toluene (product no. 22903) was purchased from Alfa Aesar, and pyridine (product no. 270407) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. High-density polyethylene (product no. 427985), polypropylene (product no. 427888), deuterium oxide (product no. 151882), alkane standard solution C8-C20 (product no. 04070) and C21-C40 (product no. 04071) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. n-pentane (product no. 16787), and n-dodecane (product no. 43459) were purchased from Acros Organics. n-hexane (product no. L09938), n-heptane (product no. A19894), n-octane (product no. A13181), n-nonane (product no. A16177), n-docosane (product no. A18050) were purchased from Alfa Aesar. n-octadecane (product no. O652) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Catalyst preparation

Supported Ru catalysts were prepared by a wet impregnation method. The support (0.96 g) and RuCl3·xH2O (133.0 mg, 0.50 mmol) were added to deionized water (100 mL) for 5 wt% Ru/support catalyst. The suspension was stirred at 600 rpm for 2 hours for mixing and heated to 50 °C until completely dried. Subsequently, the obtained catalyst was dried 12 hours at 100 °C and reduced under a 10% H2/Ar flow (50 mL/min) at 500 °C for 3 hours, with a ramping rate of 2.5 °C/min. Prior to the reaction, the catalyst was ex-situ reduced for 1.5 hours at 400 °C under a 10% H2/Ar flow (50 mL/min), with a ramping rate of 5 °C/min. A similar procedure was performed using the support (2.50 g) and RuCl3·xH2O (66.5 mg, 0.25 mmol) for 1 wt% Ru/support, and the support (3.78 g) and RuCl3·xH2O (19.9 mg, 0.075 mmol) for 0.2 wt% Ru/support catalyst. To distinguish between zeolites with different SiO2:Al2O3 ratios, zeolite Y with a SiO2:Al2O3 ratio of 30:1 termed Ru/zeolite-Y (Si/Al=30), 60:1 termed Ru/zeolite-Y, and 80:1 termed Ru/zeolite-Y (Si/Al=80).

Reaction of polyethylene depolymerization

A glass-coated magnetic stir bar, pretreated catalyst, water (if required), and PE were added to the glass liner in this order, and the liner was then placed into 50 mL 316 L stainless-steel high-pressure batch reactors fitted with a spiral wound gasket (Hanwoul Engineering CO., LTD). For depolymerization of post-consumer plastic waste, the commercial LDPE was used as received, and the LDPE bottle was cut into small pieces (3 mm x 3 mm) as shown in Supplementary Fig. 30. The reactor was purged three times with Ar (30 bar) and then three times with H2 (30 bar), followed by pressurized to H2 (30 bar). The pressurized reactor was placed in a heater, and heated at the reaction temperature (200 – 300 °C) for approximately 1 h. The reaction temperature was monitored by a thermocouple, which was inserted into the reactor. Once the temperature reached 150 °C, stirring at a rate of 500 rpm was initiated for the target reaction time. After the reaction, the reactor was cooled down to room temperature in an ice bath. The gas and liquid products were transferred to a 2 L PVC gas bag and a 50 mL centrifuge tube, respectively. Mesitylene solution (125 mmol/L) was used as an internal standard, and toluene was used as a washing solvent for the collection of the liquid phase. The unreacted reactant and catalyst were separated and subsequently dried in an oven set to 60 °C for 48 hours. The centrifuge tube, containing the reaction products and catalyst, was then weighed after drying. The weight of the initial empty tube and added catalyst were subsequently subtracted from the measurement, yielding the exact amount of unreacted reactant. The products were analyzed using a gas chromatograph (Agilent 8890 GC System) equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID) and thermal conductivity detector (TCD). A GS-Carbon PLOT (Agilent) column was used for the gas phase and an HP-1 column (Agilent) was used for the liquid phase. Analysis of gaseous products was performed using an Agilent 8890 GC System, with a ramping rate of 20 °C/min from 38 to 325 °C, and hold 10 min. The corresponding retention times of C1-C6 hydrocarbons were identified and FID area signals were calibrated by a reference gas mixture obtained from Union gas comprising CH4, C2H4, C2H6, C3H8, and n-C4H10 in Ar. TCD area signals were calibrated by high-purity hydrogen (99.999%) obtained from Union gas. Analysis of liquid product was also performed using an Agilent 8890 GC System, with a ramping rate of 15 °C/min from 50 to 325 °C, and hold 45 min. The corresponding retention times of C5-C40 hydrocarbons were identified and FID area signals were calibrated by n-pentane, n-hexane, n-heptane, n-octane, n-nonane, n-dodecane, n-octadecane, n-docosane and an alkane standard solution C8-C20 and C21-C40 from Sigma-Aldrich.

Reusability test

The spent catalyst was collected after 12 h of reaction to attain full conversion to extractable. After the drying of the reaction mixture, the spent catalyst underwent a two-step process. Firstly, it was calcined at a temperature of 300 °C under an air flow (80 mL/min). Subsequently, the catalyst was pretreated at 400 °C under a 10% H2/Ar flow (50 mL/min). The preceding reaction was repeated more than twice to ensure an adequate amount of catalyst for the subsequent reaction due to a loss of approximately 5% in catalyst recovery as in a previous work15.

Reactivity-mechanism map

The reactivity mechanism map is plotted with the summation of the normalized average carbon number ratio and metal acid balance on the x-axis and the corresponding conversion on the y-axis. To consider the MAB and average carbon number ratios as equivalent ratios, each was normalized to 0 for the lowest value and 5 for the highest, and the sum was expressed from 0 to 10. From 0 to 3.3, we denoted hydrocracking, from 3.3 to 6.7, bifunctional hydrocracking, and from 6.7 to 10, hydrogenolysis. The formula is as follows:

where \({v}_{m}\) is a volume occupied by an atom in bulk Ru metal63, \({a}_{m}\) is an area occupied by a surface atom63, and \({d}_{{VA}}\) is an average particle size determined by CO-chemisorption.

Pyridine poisoning

The catalyst underwent ex-situ reduction at a ramping rate of 5 °C/min, maintaining a temperature of 400 °C for 1.5 h under a 10% H2/Ar flow (50 mL/min). Pyridine (100 mg, 1.27 mmol) was added dropwise using a pipette to poison 50 mg of 5% Ru/zeolite-Y, 40 times the estimated acid site density by NH3-TPD to ensure sufficient poisoning. The mixture was dried for 12 hours at room temperature in a vacuum desiccator and used immediately in the reaction.

Data analysis

The BAS/LAS ratio was calculated as follows64:

where IBAS and ILAS are the integrated absorbance of the BAS and LAS band (cm 1); r is the radius of the sample disk (cm); msample is the weight of the sample (mg). The molar extinction coefficient used was 1.8 cm/μmol for BAS and 1.5 cm/μmol for LAS65,66.

Conversion and yield were calculated as follows:

Techno-economic analysis

We developed two integrated processes to produce gasoline and diesel based on experimental data (Supplementary Fig. 31): (1) one employing the depolymerization reaction with water, and (2) the other using the reaction without water (hereafter, referred to as the process with and without water, respectively). In both processes, the downstream separation system was designed to efficiently recover gasoline and diesel, considering the contaminants present in the effluent stream of the depolymerization reactor. In the process without water, since the effluent stream consists primarily of light hydrocarbons with carbon numbers below those of gasoline and diesel, a series of flash drums and distillation columns was employed for separation. On the other hand, in the process with water, heavier carbon-range products (C22+) are present in the effluent stream, requiring an additional fluidized catalytic cracking (FCC) subsystem to upgrade these C22+ into valuable fuel products.

Based on the heat and mass balance of the developed process (Supplementary Fig. 31 and Supplementary Tables 9 and 10), capital and operating costs are computed. To calculate the capital cost, equipment costs are estimated by using the Aspen Process Economic Analyzer (V12.1) or by adopting the cost data from the literature67,68. The adopted cost data is adjusted to the capacity of the process as follows:

The variable n represents the scaling exponent that quantifies the economic impact of scale. The computed capital and operating costs are adjusted to the common basis of 2020 USD using the following formula.

With the adjusted capital and operating costs, the MSP of gasoline is determined. The MSP, which means the selling price at the breakeven point, is one of the economic indicators. Supplementary Table 11 contains the detailed economic parameters and assumptions.

Life-cycle assessment

According to the international standards (ISO 14040 and 14044), LCA is conducted with four interconnected steps: goal and scope definition, life-cycle inventory analysis, life-cycle impact assessment, and life-cycle interpretation. The system boundary is from waste LDPE fractionation to product separation. To compare the environmental impact of processes, both input and output materials and energy are normalized based on a functional unit of 1 GGE of gasoline production. The environmental impacts are calculated by employing SimaPro 9.1 and the ReCiPe 2016 Midpoint with a hierarchical approach. Moreover, to consider the general region, rather than focusing on a particular local location. a global region dataset from Ecoinvent 3.6 is used.

Instruments

Pyridine adsorption spectra were acquired using a Nicolet iS20 FTIR spectrometer equipped with a Hg/Cd/telluride detector cooled using liquid nitrogen. Prior to measurements, the catalysts were reduced in situ at 400 °C for 1.5 hours under 10% H2/Ar, followed by cooled to ambient temperature (25 °C) under an Ar atmosphere. To measure the acid sites of the catalyst after the reaction, the spent catalyst was treated with in situ reduction at 400 °C for 1.5 hours under 10% H2/Ar only. A baseline spectrum was recorded prior to introducing pyridine. Subsequently, the catalysts were exposed to pyridine vapor in Ar for 20 min, generated by passing Ar flow through a bubbler filled with liquid pyridine24. Physically adsorbed pyridine was subsequently removed with pure Ar for 50 minutes. All spectra were obtained using 128 scans with a resolution of 2 cm−1. The peaks at 1450 cm−1 and 1540 cm−1 correspond to the Lewis acid sites (LAS) and the Brønsted acid sites (BAS)65,66,69,70, respectively. The ratio of Brønsted acid site density to Lewis acid site density (BAS/LAS) was estimated by pyridine-DRIFTS analysis69,70. The pyridine vibration bands were classified as following70: Brønsted acid site (BAS) exhibiting peaks around 1540 cm−1, Lewis acid site (LAS) characterized by peaks near 1450 cm−1.

Scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) was conducted using a NEOARM (JEOL) with a Cs probe aberration corrector operated at 200 kV with a spatial resolution of <0.1 nm. STEM images were recorded after ex situ reduction of the fresh and spent catalysts at 400 °C under 10% H2/Ar. The high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) mode was applied to acquire images under the following conditions: HAADF detector angle: 68 to 270 mrad; probe convergence angle (2α): 1.5 to 20 mrad; probe current: 1.0 nA; and probe diameter: 0.2 nm. Over 200 randomly selected particles were examined to calculate the mean particle size, which exhibited a narrow Gaussian distribution in the histogram.

A Thermo Scientific NEXSA XPS system equipped with a monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source was used for XPS. XPS spectra were recorded after ex situ reduction of the fresh and spent catalysts at 400 °C under 10% H2/Ar. The number of scans and dwell time were 10 and 50 ms, respectively. To accurately calibrate the binding energies, the reference for this calibration was the lattice oxygen (O 1 s) peak at 529.9 eV, instead of the C 1 s peak19. This selection was primarily based on the overlap between the binding energy of the C 1s peak and the Ru 3d5/2 peak, rendering the C 1 s peak unsuitable for precise calibration40.

Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) analysis were conducted using an automated gas adsorption analyzer (TriStar 3000, Micromeritics). Prior to analysis, fresh and spent catalysts weighing ~0.1 g was subjected to degassing by heating at 90 °C for 2 h, followed by further heating at 300 °C for 6 h under He flow (60 mL/min). BET surface area was determined through a standard multipoint analysis (P/P0 = 0.05-0.3), while the pore volume was measured using the single-point method at P/P0 = 0.995. The adsorption average pore width (4 V/A) was calculated based on the BET results. Additionally, pore size distribution was obtained using the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) method.

Ammonia temperature-programmed desorption (NH3-TPD) spectra were collected by AutoChem II 2920 (Micromeritics) instrument. Before conducting NH3-TPD, the catalyst underwent in situ reduction at 400 °C for 1.5 hours under a 10% H2/Ar flow (50 mL/min). Subsequently, the catalyst was purged with He and cooled down to 50 °C under He flows (50 mL/min). Adsorption of NH3 onto the catalyst surfaces occurred by flowing 10% NH3/He at 50 °C and 50 mL/min for 1 hour, followed by purging with He for 1 hour. The desorption process was quantified using a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) with a temperature ramp of 5 °C/min, starting from 100 °C and reaching 900 °C. The acid site density was estimated by calculating a coefficient multiplied by the area divided by the weight, and the coefficient was obtained using a specified reference.

DEPT 135 13C NMR analysis was conducted using a 600 MHz Agilent DD2 NMR Spectrometer at room temperature to characterize the product structure. The product was diluted in CDCl3, and the spectra were recorded over 500 scans.

TPO-MS analysis was conducted using a BEL CAT II and BEL mass analyzer (MicrotracBEL). Prior to analysis, catalysts were heated to 200 °C for 2 hours under a He flow (30 mL/min) to remove physically adsorbed water. Thereafter, the catalyst was heated to 1000 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min under a 5% O2/He flow (30 mL/min). The analysis was performed using thermal conductivity (TCD) and mass spectrometry.

To estimate the amount of coke in the spent catalysts, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed using a DTG-60H (Simadzu). Prior to analysis, catalysts were heated to 200 °C for 1 hour under nitrogen flow (50 mL/min) to remove physically adsorbed water. Thereafter, the catalyst was heated to 800 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min under airflow (50 mL/min) within an alumina cell.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are provided in the Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Plastics Europe. Plastics – The Fast Facts 2023 (2023).

Geyer, R., Jambeck, J. R. & Law, K. L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 3, e1700782 (2017).

Jung, S. & Ro, I. Strategic use of thermo-chemical processes for plastic waste valorization. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 40, 693–705 (2023).

Vollmer, I. et al. Beyond mechanical recycling: giving new life to plastic waste. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 15402–15423 (2020).

Musa, A., Jaseer, E. A., Barman, S. & Garcia, N. Review on catalytic depolymerization of polyolefin waste by hydrogenolysis: state-of-the-art and outlook. Energy Fuels 38, 1676–1691 (2024).

Dong, S. et al. Catalytic conversion of model compounds of plastic pyrolysis oil over ZSM-5. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 324, 122219 (2023).

Ragauskas, A. J. et al. New technologies are needed to improve the recycling and upcycling of waste plastics. ChemSusChem 14, 3982–3984 (2021).

Font, R., Marcilla, A., Garcia, A. N., Caballero, J. A. & Conesa, J. A. Comparison between the pyrolysis products obtained from different organic wastes at high temperatures. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 32, 41–49 (1995).

Weitkamp, J. Catalytic hydrocracking-mechanisms and versatility of the process. ChemCatChem 4, 292–306 (2012).

Wang, Y.-Y. et al. Catalytic hydrogenolysis of polyethylene under reactive separation. ACS Catal. 14, 2084–2094 (2024).

Zhao, Z. et al. Catalytic hydrogenolysis of plastic to liquid hydrocarbons over a nickel-based catalyst. Environ. Pollut. 313, 120154 (2022).

Jia, C. et al. Deconstruction of high-density polyethylene into liquid hydrocarbon fuels and lubricants by hydrogenolysis over Ru catalyst. Chem. Catal. 1, 437–455 (2021).

Rorrer, J. E., Beckham, G. T. & Román-Leshkov, Y. Conversion of polyolefin waste to liquid alkanes with Ru-based catalysts under mild conditions. JACS Au 1, 8–12 (2021).

Ellis, L. D. et al. Chemical and biological catalysis for plastics recycling and upcycling. Nat. Catal. 4, 539–556 (2021).

Nakaji, Y. et al. Low-temperature catalytic upgrading of waste polyolefinic plastics into liquid fuels and waxes. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 285, 119805–119805 (2021).

Nakagawa, Y. et al. Regioselectivity and reaction mechanism of Ru-catalyzed hydrogenolysis of squalane and model alkanes. ChemSusChem 10, 189–198 (2017).

Chen, S. et al. Ultrasmall amorphous zirconia nanoparticles catalyse polyolefin hydrogenolysis. Nat. Catal. 6, 161–173 (2023).

Nguyen-Phu, H. et al. Investigating the influence of Ru structures and supports on hydrogenolysis of polyethylene plastic waste. Chem. Eng. J. 475, 146076 (2023).

Kim, T., Nguyen-Phu, H., Kwon, T., Kang, K. H. & Ro, I. Investigating the impact of TiO(2) crystalline phases on catalytic properties of Ru/TiO2 for hydrogenolysis of polyethylene plastic waste. Environ. Pollut. 331, 121876 (2023).

Celik, G. et al. Upcycling single-use polyethylene into high-quality liquid products. ACS Cent. Sci. 5, 1795–1803 (2019).

Wu, X. et al. Size-controlled nanoparticles embedded in a mesoporous architecture leading to efficient and selective hydrogenolysis of polyolefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 5323–5334 (2022).

Wang, C. et al. Polyethylene hydrogenolysis at mild conditions over ruthenium on tungstated zirconia. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1, 1422–1434 (2021).

Rorrer, J. E. et al. Role of bifunctional Ru/Acid catalysts in the selective hydrocracking of polyethylene and polypropylene waste to liquid hydrocarbons. ACS Catal. 12, 13969–13979 (2022).

Vance, B. C. et al. Single pot catalyst strategy to branched products via adhesive isomerization and hydrocracking of polyethylene over platinum tungstated zirconia. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 299, 120483–120483 (2021).

Munir, D., Irfan, M. F. & Usman, M. R. Hydrocracking of virgin and waste plastics: a detailed review. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 90, 490–515 (2018).

Liu, S., Kots, P. A., Vance, B. C., Danielson, A. & Vlachos, D. G. Plastic waste to fuels by hydrocracking at mild conditions. Sci. Adv. 7, 1–10 (2021).

Vance, B. C., Kots, P. A., Wang, C., Granite, J. E. & Vlachos, D. G. Ni/SiO2 catalysts for polyolefin deconstruction via the divergent hydrogenolysis mechanism. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 322, 122138 (2023).

Sun, J. A. et al. Size and structure effects of carbon-supported ruthenium nanoparticles on waste polypropylene hydrogenolysis activity, selectivity, and product microstructure. ACS Catal. 14, 3228–3240 (2024).

Tamura, M. et al. Structure-activity relationship in hydrogenolysis of polyolefins over Ru/support catalysts. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 318, 121870 (2022).

Du, J. et al. Efficient solvent- and hydrogen-free upcycling of high-density polyethylene into separable cyclic hydrocarbons. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 772–779 (2023).

Kwon, T. & Ro, I. Advancing towards a sustainable future: recent trends in catalytic upcycling of waste plastics. Korean Chem. Eng. Res. 61, 505–516 (2023).

Lee, W. T. et al. Mechanistic classification and benchmarking of polyolefin depolymerization over silica-alumina-based catalysts. Nat. Commun. 13, 4850 (2022).

Kots, P. A., Vance, B. C., Quinn, C. M., Wang, C. & Vlachos, D. G. A two-stage strategy for upcycling chlorine-contaminated plastic waste. Nat. Sustain. 6, 1258–1267 (2023).

Chen, L. et al. Disordered, sub-nanometer Ru structures on CeO2 are highly efficient and selective catalysts in polymer upcycling by hydrogenolysis. ACS Catal. 12, 4618–4627 (2022).

Kwon, T., Jeong, H., Kim, M., Jung, S. & Ro, I. Catalytic approaches to tackle mixed plastic waste challenges: a review. Langmuir 40, 17212–17238 (2024).

Martínez, A. et al. A detailed study of the activity and deactivation of zeolites in hybrid Co/SiO2-zeolite Fischer–Tropsch catalysts. J. Catal. 249, 162–173 (2007).

Oppmann, N. & Jess, A. Hydrocracking of model substances on Pt/H‐ZSM‐5 under an imitated fischer‐tropsch product gas composition. Chem. Eng. Technol. 46, 1924–1934 (2023).

Yan, T. Y. The promotional effect of water in hydrocracking. J. Catal. 25, 204–211 (1972).

Zhao, Y. X. & Wojciechowski, B. W. The consequences of steam dilution in catalytic cracking: I. Effect of steam dilution on reaction rates and activation energy in 2-methylpentane cracking over USHY. J. Catal. 163, 365–373 (1996).

Morgan, D. J. Resolving ruthenium: XPS studies of common ruthenium materials. Surf. Interface Anal. 47, 1072–1079 (2015).

Wood, J. & Gladden, L. F. Effect of coke deposition upon pore structure and self-diffusion in deactivated industrial hydroprocessing catalysts. Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 249, 241–253 (2003).

Lu, Z., Kuizhi, C. & Banghao, C. Factors that determine zeolite stability in hot liquid water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 11810–11819 (2015).

Wolf, M. Thermodynamic assessment of the stability of bulk and nanoparticulate cobalt and nickel during dry and steam reforming of methane. RSC Adv. 11, 18187–18197 (2021).

Brosius, R., Kooyman, P. J. & Fletcher, J. C. Selective formation of linear alkanes from n-hexadecane primary hydrocracking in shape-selective MFI zeolites by competitive adsorption of water. ACS Catal. 6, 7710–7715 (2016).

Zong, X., Xie, T. & Vlachos, D. G. Predicting hydrogenolysis reaction barriers of large hydrocarbons on metal surfaces using machine learning: Implications for polymer deconstruction. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 353, 124070 (2024).

Wang, C. et al. A general strategy and a consolidated mechanism for low-methane hydrogenolysis of polyethylene over ruthenium. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 319, 121899–121899 (2022).

Degnan, T. F. & Kennedy, C. R. Impact of catalyst acid/metal balance in hydroisomerization of normal paraffins. AIChE J. 39, 607–614 (2004).

Thybaut, J. W. et al. Acid-Metal Balance of a Hydrocracking Catalyst: Ideal versusNonideal Behavior. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 44, 5159–5169 (2005).

Alvarez, F. F. R. R., G. Perot, C. Thomazeau, M. Guisnet. Hydroisomerization and Hydrocracking of Alkanes: 7. Influence of the Balance between Acid and Hydrogenating Functions on the Transformation ofn-Decane on PtHY Catalysts. J. Catal. 162, 179–189 (1996).

Zecevic, J., Vanbutsele, G., De Jong, K. P. & Martens, J. A. Nanoscale intimacy in bifunctional catalysts for selective conversion of hydrocarbons. Nature 528, 245–254 (2015).

Chen, L. et al. Effect of reaction conditions on the hydrogenolysis of polypropylene and polyethylene into gas and liquid alkanes. React. Chem. Eng. 7, 844–854 (2022).

Jeong, S., Kim, J., Liu, J. J. & Won, W. A lignocellulosic 2, 3-butanediol strategy: process development and integrative analyses. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11, 110085 (2023).

Oh, M.-Y., Gujjala, L. K. S. & Won, W. Process development for production of platform chemicals from white birch: Insights from techno-economic and life-cycle assessment. Chem. Eng. J. 472, 144955 (2023).

Wiatrowski, M., Klein, B., Kinchin, C., Huang, Z. & Davis, R. Opportunities for Utilization of Low-Cost Algae Resources: Techno-Economic Analysis Screening for Near-Term Deployment (Parts 1 and 2). (National Renewable Energy Lab.(NREL), 2022).

Yadav, G. et al. Techno-economic analysis and life cycle assessment for catalytic fast pyrolysis of mixed plastic waste. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 3638–3653 (2023).

Gong, C., Lee, S. & Won, W. Process development and analyses for the co‐production of 2‐methyltetrahydrofuran and 1, 4‐pentanediol from lignocellulosic biomass. GCB Bioenergy 15, 900–915 (2023).

Kang, C., Liu, J. J., Woo, N. & Won, W. Process design for the sustainable production of butyric acid using techno-economic analysis and life cycle assessment. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 11, 4430–4440 (2023).

Ahn, B., Jin, G., Kim, J. & Won, W. Integrated process design and analysis for co-production of biofuels with adipic acid and tetrahydrofuran. Ind. Crop. Prod. 200, 116830 (2023).

Ahn, B., Park, C., Liu, J. J., Ok, Y. S. & Won, W. Maximizing the utilization of lignocellulosic biomass: Process development and analysis. Renew. Energy 215, 119004 (2023).

ISO, I. 14044: 2006/AMD 2: 2020—Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines—Amendment 2. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland (2020).

Park, D., Lee, H. & Won, W. Unveiling the environmental gains of biodegradable plastics in the waste treatment Phase: A Cradle-to-Grave life cycle assessment. Chem. Eng. J. 487, 150540 (2024).

Technical Committee ISO/TC 207, E. M. Environmental Management-life Cycle Assessment-principles And Framework (International Organization for Standardization, 2006).

Ertl, G., Knözinger, H. & Weitkamp, J. Handbook of Heterogeneous Catalysis. Vol. 2 (VCH Weinheim, 1997).

Emeis, C. A. Determination of integrated molar extinction coefficients for IR absorption bands of pyridine adsorbed on solid acid catalysts. J. Catal. 141, 347–354 (1993).

S. Khabtou, T. C., J.C. Lavalley. Quantitative infrared study of the distinct acidic hydroxyl groups contained in modified Y zeolites. Microporous Mater. 3, 133–148 (1994).

Zholobenko, V. et al. Probing the acid sites of zeolites with pyridine: quantitative AGIR measurements of the molar absorption coefficients. J. Catal. 385, 52–60 (2020).

Davis, R., Wiatrowski, M., Kinchin, C. & Humbird, D. Conceptual Basis and Techno-Economic Modeling for Integrated Algal Biorefinery Conversion of Microalgae to Fuels and Products (2019 NREL TEA Update: Highlighting Paths to Future Cost Goals via a New Pathway for Combined Algal Processing) (National Renewable Energy Lab.(NREL), 2020).

Davis, R. E. et al. Process Design And Economics For The Conversion Of Lignocellulosic Biomass To Hydrocarbon Fuels And Coproducts: 2018 Biochemical Design Case Update; Biochemical Deconstruction And Conversion Of Biomass To Fuels And Products Via Integrated Biorefinery Pathways (National Renewable Energy Lab.(NREL), Golden, 2018).

Zepeda, T. A. et al. Synergetic effect in RuxMo(1-x)S2/SBA-15 hydrodesulfurization catalysts: comparative experimental and DFT studies. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 251, 143–153 (2019).

Kumar, V. V. et al. An investigation on the influence of support type for Ni catalysed vapour phase hydrogenation of aqueous levulinic acid to γ-valerolactone. RSC Adv. 6, 9872–9879 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Korea Environment Industry & Technology Institute(KEITI) through the Center of plasma process for organic material recycling project, funded by Korea Ministry of Environment(MOE) (2022003650002 to I.R.), the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by The Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT) under grant NRF-2022R1F1A1074392 to I.R., and the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning(KETEP) and the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy(MOTIE) of the Republic of Korea (RS-2024-00419764 to W. W.)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.R. conceived the project idea and contributed to the experiment design. T.K. conducted the experiments, while T.K. and K.H.K. handled catalyst characterization and data analysis. B.A. and W.W. provided insights into process analysis. Project supervision was carried out by I.R. and W.W. The manuscript was collectively written by T.K., B.A., W.W., and I.R. All authors participated in result discussions and manuscript review.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Avantika Singh and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kwon, T., Ahn, B., Kang, K.H. et al. Unraveling the role of water in mechanism changes for economically viable catalytic plastic upcycling. Nat Commun 15, 10239 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54495-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54495-5

This article is cited by

-

Hydrogen-Free Catalytic Strategies for the Upcycling of Polyolefin Plastics

Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering (2026)

-

Polyethylene hydrogenolysis to liquid products over bimetallic catalysts with favorable environmental footprint and economics

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Sustainable polyolefin upcycling using liquid organic hydrogen carrier based hydrogen delivery and hydrocracking

Nature Communications (2025)