Abstract

Many studies try to comprehend and replicate the natural silk spinning process due to its energy-efficient and eco-friendly process. In contrast to spider silk, the mechanisms of how silkworm silk fibroin (SF) undergoes liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) concerning the various environmental factors in the silk glands or how the SF coacervates transform into fibers remain unexplored. Here, we show that calcium ions, among the most abundant metal ions inside the silk glands, induce LLPS of SF under macromolecular crowded conditions by increasing both hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions between SF. Furthermore, SF coacervates assemble and further develop into fibrils under acidification and shear force. Finally, we prepare SF fiber using a pultrusion-based dry spinning, mirroring the natural silk spinning system. Unlike previous artificial spinning methods requiring concentrated solutions or harsh solvents, our process uses a less concentrated aqueous SF solution and minimal shear force, offering a biomimetic approach to fiber production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Silk fibers produced by silkworms have exceptional mechanical strength and toughness achieved by their protein structure and the hierarchical assembly of the proteins to fibrils1,2. Silk fibroin (SF), the main protein of silk fiber, consists of a heavy chain (H-chain; ~391 kDa) and a light chain (L-chain; ~27 kDa). The H-chain has an extended hydrophobic repetitive domain interspersed with hydrophilic spacers and hydrophilic terminal domains3, where the L-chain is connected to the carboxylic terminal domain of H-chain by a single disulfide bond4. The hydrophobic interactions and the self-assembly to beta sheets of the repetitive domain are responsible for the high mechanical strength of silk fibers5. The hydrophilic spacers and terminal domains control the assembly of SF and regulate the transformation of liquid SF solution into solid fibers6,7,8. This domain structure allows the silkworms to instantly produce strong silk fibers from an aqueous protein dope solution with the advantages of minimal force, low energy consumption, and little to no environmental harm9,10. Thus, understanding and replicating the natural silk fiber production process holds significant promise for enhancing current methods for commercial synthetic fiber production.

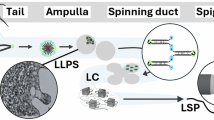

The conversion of SF from a liquid solution to a solid fiber is controlled by a range of chemical and physical factors inside the silk glands. Specifically, from the posterior to the anterior silk gland, SF experiences gradual acidification, converting the secondary structure from a random coil to beta sheets11,12,13. A shear force, mainly generated by pultrusion14, further facilitates the conversion of SF from liquid solution to fibers15,16,17. Throughout this process, various metal ions18,19, such as calcium ions (Ca2+) and potassium ions (K+), actively regulate the silk spinning process, mainly by controlling the secondary structure and shear sensitivity of SF20,21. Particularly, Ca2+ is regarded as one of the most important metal ions as it prevents the premature structural transition of SF before it is spun into fibers and modulates the SF self-assembly by interacting with the negatively charged amino acids during spinning12,21,22,23,24.

On the other hand, liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS), a phenomenon in which one component of a solution spontaneously separates from the remainder of the solution forming a condensed phase called a coacervate, has received recent attention as a crucial component of the silk spinning process. While the term LLPS has not been used for SF until recently, the phenomenon itself has been reported since the 1980s25,26. A number of reports have blended SF with other polymers and observed globular structures27,28,29,30. Importantly, Jin and Kaplan studied the primary sequence of SF and proposed a micelle model, where they suggested that the domain structure of SF may drive the formation of nano- and microscale spherical assemblies in an aqueous milieu6. Furthermore, in a recent report, Eliaz et al. observed LLPS of native SF in the middle silk glands of silkworms, confirming the existence of LLPS in vivo31. However, the critical question of how SF undergoes LLPS under the various environmental factors inside the silk glands (i.e., metal ions, pH, and shear force) and how the SF coacervates transition to solid fibers remains unanswered.

One potential factor closely associated with the LLPS of SF is the ionic environment within the silk glands. Several proteins with a similar domain structure as SF, characterized by a hydrophobic domain flanked by hydrophilic terminal domains, have been reported to undergo LLPS in response to ionic compounds32,33,34. For example, phosphate ions have been found to induce the LLPS of spidroin, the protein constituting spider silks, through a process mediated by the carboxyl-terminal and repetitive domains32. In addition, the interaction between metal ions and the terminal domains of cytoplasmic proteins (e.g., tau, α-synuclein, FUS) has been reported to regulate LLPS33. Hence, it is plausible that the LLPS of SF may exhibit similar ion-dependent behavior. Specifically, Ca2+ is a strong candidate for inducing LLPS of SF, given its abundance within the middle silk gland where LLPS has been observed18,19,31. Therefore, a detailed study on the relationship between Ca2+ and LLPS of SF is required to obtain a better understanding of the silk spinning mechanism.

Herein, we investigated the role of Ca2+ in the LLPS of SF and further evaluated the transition of coacervates into fibrils by external stimuli, namely acidification and shear force. We found that the addition of Ca2+, in the presence of the widely used crowding agent dextran, spontaneously condensed SF into coacervates. Furthermore, acidic conditions and applying shear force led to the transition of these SF coacervates into fibrils. We utilized this transition of SF coacervates and successfully spun SF fibers with hierarchical structures. Our work identifies a role for Ca2+ in inducing LLPS of SF. Moreover, our biomimetic dry spinning method presents the potential of understanding the natural silk spinning mechanism and offers an efficient method for fiber production.

Results

Calcium ions induce the LLPS of SF

As mentioned above, since the LLPS of SF has been observed in the middle silk gland of the silkworm, together with the high content of Ca2+, it suggests a potential role of Ca2+ in the formation of the LLPS of SF. To investigate the effect of Ca2+ on the LLPS of SF, we added Ca2+ (37.5 mM) to a mixed solution of 1.5% (w/v) SF and 2.5% (w/v) dextran (SF_Dex), where dextran was added to increase the interactions between the SF proteins35. Calcium chloride was chosen as the source for Ca2+ as the chloride anion has negligible impact on the LLPS of SF, which will be discussed later. Before adding Ca2+, the SF_Dex solution was transparent (Fig. 1a). However, the solution immediately turned turbid after adding the Ca2+. When the mixture was observed under an optical microscope, the formation of coacervates was observed (Fig. 1b). In addition, the coalescence of the coacervates confirmed their liquid-like properties (Supplementary Fig. 1). To verify which polymer, SF or dextran, was constituting the coacervate phase, a fluorescence microscope was used. Rhodamine B (red) and FITC-dextran (green) were used to visualize SF and dextran, respectively. Fluorescence microscopy images revealed that upon the addition of Ca2+, the two polymers were segregated into two separate phases (Fig. 1b), where SF formed the spherical coacervate phase and dextran was observed in the area outside the coacervates (dilute phase).

a The silk fibroin and dextran solution (SF_Dex) became turbid after the addition of Ca2+ (37.5 mM). The turbid solution was further separated into two phases after centrifugation (10,000 × g, 15 min). b Optical and fluorescence images of Ca2+-induced LLPS of SF. ([SF] = 1.5% (w/v), [dextran]=2.5% (w/v), [Ca2+]=37.5 mM. Red: SF dyed with rhodamine B, green: FITC-dextran. Scale bar=50 µm). c Phase separation map as a function of the SF and Ca2+ concentrations. The red binodal line was drawn by connecting the data points where LLPS was observed after 15 min. The inset fluorescence images correspond to the solutions from each data point inside the dashed boxes. (squrae: No LLPS, triangle: LLPS observed after 15 min, circle: LLPS observed immediately after mixing; scale bar=50 µm). d SF concentrations of the bottom and the supernatant phase at different Ca2+ concentrations calculated from the absorbance at 278 nm. Data are presented as mean ± SD for n = 3 independent experiments. e FTIR spectra of the bottom and the supernatant phase of each solution with different Ca2+ concentrations. f Relative proportions of different types of secondary structure of the SF in the bottom phase determined via deconvolution of the amide I peaks. Data are presented as mean ± SD for n = 5 independent experiments. The deconvolution of the spectra for Ca2+_0 mM and Ca2+_0.75 mM was not conducted because of the existence of dextran in the bottom phase. In (d, e), data from samples that underwent LLPS are highlighted in red. g Diffusion coefficients calculated from FRAP measurements of SF coacervates from different Ca2+ concentrations. Data are presented as mean ± SD for n = 3 independent experiments. The statistical significance (P < 0.05) of the differences was checked using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s test. h Turbidity of SF_Dex solutions with different types of cations and anions at the same concentration (37.5 mM). The highlighted columns indicate the solutions that underwent LLPS. Data are presented as mean ± SD for n = 3 independent experiments. The corresponding data points of the bar graphs in (d, f, g, h) are indicated as triangles.

In order to determine the concentration of SF and Ca2+ under which SF undergoes LLPS, a phase separation map was generated (Fig. 1c) based on microscopy observations (Supplementary Fig. 2a) and turbidity measurements (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Depending on the concentration of SF and Ca2+, the mixed solution exhibited three different states: 1. a turbid, LLPS solution (2-phase region; circles in Fig. 1c), 2. a transparent solution (1-phase region; squares in Fig. 1c), and 3. a solution undergoing delayed LLPS (Supplementary Fig. 3), which was considered as a threshold concentration for undergoing LLPS (binodal line; triangles in Fig. 1c). The effect of SF and Ca2+ concentrations on the degree of LLPS was investigated by evaluating the coacervate size and the turbidity of the solutions under the 2-phase region (Fig. 1c; Supplementary Fig.2b). At the same SF concentration, the coacervate size was constant regardless of the Ca2+ concentration. Similarly, there was no noticeable difference in turbidity between these solutions (Supplementary Fig. 2b). However, changing the SF concentration impacted the coacervate size. Specifically, when the SF concentration was 1.5% (w/v), the coacervate diameter ranged from 20 to 30 µm, and when the concentration was decreased to 0.5% (w/v), the diameter decreased to less than 10 µm. Further dilution resulted in coacervates with a diameter of less than 1 µm. This size reduction was attributed to the sparseness of the SF proteins in diluted solutions. When coacervates came into contact with other coacervates, they coalesced and formed a larger coacervate. However, when the coacervates were sparsely distributed, coalescence occurred less often, resulting in coacervates with smaller diameters. The coacervate size reduction correlated with the turbidity decrease of LLPS solutions with decreasing SF concentration, which is likely due to the reduced light scattering from smaller and sparser coacervates. Therefore, while the formation of LLPS was Ca2+ concentration-dependent, the coacervate size was dependent on the SF concentration. However, increasing Ca2+ concentration did not have a noticeable effect on the coacervate size or the turbidity of the solution. These results indicated that solutions with additional Ca2+ above the threshold concentration do not have a stronger tendency to undergo LLPS.

SF are condensed in a random coil state inside the coacervates

While further increasing the Ca2+ concentration above the binodal line did not have a notable effect on the degree of LLPS (Fig. 1c; Supplementary Fig. 2), it could have a different effect on the SF inside the coacervates. Therefore, we investigated the effect of different Ca2+ concentrations on the concentration, conformation, and diffusivity of SF inside the coacervates while the initial SF concentration was fixed at 1.5% (w/v). In order to analyze the coacervate and the dilute phase individually, these two phases must be separated32,36. Therefore, the solutions were centrifuged (10,000 × g for 15 min) to achieve fast and uniform precipitation, resulting in a precipitated bottom phase and a supernatant in the upper portion (Fig. 1a). For samples that did not undergo LLPS (0 mM and 0.75 mM Ca2+), centrifugation resulted in no visible change between the bottom and upper portion of the solutions. However, sedimentation of SF may have occurred without visual changes. To account for this possibility, the lowermost and uppermost portions of the centrifuged solution were collected even though no visual sedimentation had occurred.

The SF concentration in each phase was calculated by employing UV‒Vis spectroscopy (Fig. 1d). The SF concentration was determined from the absorbance at 278 nm (Supplementary Fig. 4), which corresponds to the absorbance of Tyr residues abundant in SF. The SF concentration in the bottom phase of the phase-separated solutions (≥7.5 mM Ca2+) was found to be 9–9.9% (w/v), which was 6–6.6-fold greater than the SF concentration in the initial solution 1.5% (w/v). Thus, we quantitatively confirmed that Ca2+-induced LLPS of SF resulted in condensation of SF in the coacervates. However, the SF concentration in the bottom phase of the phase-separated solutions was unaffected by different Ca2+ concentrations. This result indicates that increasing the Ca2+ concentration above the threshold concentration for undergoing LLPS did not increase the degree of condensation of SF, similar to the effect of Ca2+ concentration on the coacervate size and turbidity of the solution discussed above (Fig. 1c).

The composition and the secondary structure of SF in each phase were studied from the FTIR spectra of the bottom and the supernatant phase of the samples with different Ca2+ concentrations (Fig. 1e; Supplementary Fig. 5). No marked difference was observed in the supernatant spectra regardless of whether the samples underwent LLPS. In these spectra, characteristic peaks of both SF (amide I, 1600–1700 cm−1; amide II, 1470–1570 cm−1) and dextran (glycosidic linkage, 950–1050 cm−1) were observed (Supplementary Fig. 6 for pure polymer). However, the FTIR spectra of the bottom phase were significantly different depending on the LLPS formation. For the samples that did not undergo LLPS, the bottom phase spectra exhibited characteristic peaks of both SF and dextran. On the other hand, for the samples that underwent LLPS, the bottom phase spectra exhibited only the characteristic peaks of SF but not those of dextran. This shows that while both SF and dextran were present in the dilute phase, only SF was present in the coacervates, consistent with the fluorescence image analysis (Fig. 1b). Furthermore, deconvolution of the amide I peak revealed that the secondary structure of SF within the coacervates was predominantly random coil, regardless of the Ca2+ concentration (Fig. 1f). This result is consistent with the circular dichroism (CD) spectra, which revealed that SF in the LLPS solutions was in a random coil structure (negative ellipticity near 195 nm; Supplementary Fig. 7). These results indicate that the condensation of SF into coacervates by Ca2+ did not alter the secondary structure of SF.

FRAP analysis was conducted on coacervates with different Ca2+ concentrations to compare the diffusivity of SF. The surfaces of the glass slides and coverslips used for FRAP measurements were conjugated with dextran to prevent the spreading of SF coacervates. To minimize the effect of size, coacervates with diameters larger than 12 µm were chosen for FRAP experiments. The FRAP data were fitted to an exponential decay function to obtain a diffusion coefficient, which represented the diffusion rate of SF inside the coacervates. The diffusion coefficient was found to be independent of the Ca2+ concentration, revealing that while Ca2+ induces the condensation of SF into coacervates, it does not inhibit the mobility of the SF chains (Fig. 1g; Supplementary Fig. 8). Our FTIR data described above (Fig. 1e, f), which revealed that SF remained in a random coil state, further support these results.

Taken together, we have found that Ca2+ condensed SF inside the coacervates without altering the secondary structure or the mobility of SF. A high SF concentration and a stable random coil secondary structure are crucial components of a dope solution for the silk spinning process for retaining the viscosity without irreversible beta sheet transition. Our results confirm that the Ca2+-induced SF LLPS meets these requirements.

Divalent cations and kosmotropic anions also induce LLPS of SF

Next, we investigated whether the induction of LLPS was a specific characteristic of Ca2+ by evaluating the occurrence of LLPS in the presence of different types of cations that can be found inside the silk glands18,19 (Fig. 1h; Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10). The occurrence of LLPS was found to depend on the valence state of the cations. No turbidity changes or coacervates were observed when monovalent cations (sodium and potassium ions) were added to the SF solution. However, when divalent cations (zinc, copper, manganese, magnesium, and calcium ions) were added to the solution, coacervates and an increase in turbidity were observed (Fig. 1h; Supplementary Fig. 9). Additionally, the degree of LLPS differed depending on the type of divalent cation. Notably, the addition of zinc or copper ions led to greater turbidity than that observed with the same concentration of calcium ions. A large error bar in turbidity was obtained upon the addition of copper ions, owing to the fast sedimentation and gelation of the coacervates. This result was expected, as multiple studies have reported that copper ions strongly interact with SF, inducing the formation of beta-sheets even at low concentrations37,38. The addition of manganese ions led to turbidity to a degree similar to that induced by calcium ions. The addition of magnesium ions led to delayed LLPS, where the coacervates slowly appeared over time (Supplementary Fig. 11). According to studies conducted on alginate hydrogels, magnesium ions have a weak tendency to form crosslinks via electrostatic interactions owing to the strong affinity between the magnesium ions and water molecules39,40. These interactions may be the reason for the relatively weak driving force for the phase separation of SF in the presence of magnesium ions. We also performed the same experiment with trivalent cations (ferric ions), but SF gelled immediately after mixing. The fast gelation is possibly due to the strong interaction between ferric ions and SF chains41,42. Therefore, there is a correlation between the valence state of the added cation and its ability to drive LLPS of SF. Moreover, the effect of these different types of cations in different combinations and ratios on the state of SF coacervates may further reveal the fundamental role of metal ions during the silk spinning process. Meanwhile, we also observed that the pH of the solution altered depending on the types of cations added (Supplementary Fig. 12a). However, adjusting the pH with 0.1 M HCl to similar values observed with the added cations did not induce LLPS, suggesting that the pH value was not the determining factor in the LLPS of SF with cations (Supplementary Fig. 12b).

In addition to cations, anionic compounds are also present inside the silk glands as counter ions. Compared to cations, the effect of anions during the silk spinning of silkworms remains largely unexplored. However, multiple studies have suggested that anions play an important role in the silk spinning of spiders. Specifically, phosphate ions are known to drive LLPS of spidroin proteins by increasing hydrophobic interactions32,43. Therefore, we investigated whether anions can also induce LLPS of SF following a mechanism similar to that of spidroin. The anions were selected based on their position in the Hofmeister series44. Similar to what was reported for spidroin, the addition of kosmotropic anions (citrate and phosphate ions) induced LLPS, whereas the addition of chaotropic anions (iodide and thiocyanate ions) did not induce LLPS (Fig. 1h; Supplementary Fig. 10). Therefore, hydrophobic interactions are likely important factors in the LLPS of SF.

Mechanism of calcium ion-induced LLPS of SF

For LLPS to occur, attractive forces between proteins are required45. The above results revealed that divalent cations promote LLPS of SF while monovalent cations did not, suggesting electrostatic forces may be involved in forming LLPS. On the other hand, the addition of kosmotropic anions resulted in LLPS of SF, indicating hydrophobic interactions may also be one of the driving forces for LLPS. Previous studies have reported that Ca2+ mediates the rheological properties and the self-assembly of SF during silk spinning by interacting with the negatively charged amino acids of SF12,20,21,22. Based on these observations, Ca2+ may be driving LLPS by forming salt bridges via electrostatic interaction with carboxylic acid residues of SF. On the other hand, an increase in hydrophobic interactions may also be a factor in Ca2+-induced LLPS. However, unlike the kosmotropic anions observed above, Ca2+ is chaotropic, which weakens hydrophobic interaction between proteins. Another possibility is that Ca2+ shields the negative charge of carboxylic acid residues of SF and destabilizes the electrostatic repulsion, increasing the hydrophobic interactions between SF chains. Therefore, we proposed two possible mechanisms through which Ca2+ might promote the LLPS of SF: 1. hydrophobic interactions via charge screening and 2. salt bridge formation via electrostatic interactions.

We first added 1,6-hexanediol to investigate the feasibility of the first proposed mechanism. The 1,6-hexanediol is an amphiphilic compound known to disrupt the hydrophobic interactions between polymers, which is widely used for investigating hydrophobic interactions in LLPS46,47. From fluorescence microscopy observations, we found that this addition decreased the size of the SF coacervates (Fig. 2a). Moreover, after the addition of 5% (w/v) 1,6-hexanediol, the coacervates entirely disappeared. Therefore, hydrophobic interactions between SFs are closely related to Ca2+-induced LLPS.

a Fluorescence images of silk fibroin (SF) coacervates with different concentrations of 1,6-hexanediol (scale bar = 50 µm). b Zeta potential of SF and dextran (SF_Dex) solutions with different concentrations of Ca2+. Data are presented as mean ± SEM for n = 3 independent experiments. c Zeta potential of SF_Dex solutions with different concentrations of Na+. Data are presented as mean ± SEM for n = 3 independent experiments. The dotted orange line in (b, c) indicates the lowest zeta potential of the SF_Dex solution with added Ca2+ at which LLPS was observed ([Ca2+]=7.5 mM). d Turbidity change in the SF LLPS solution (1 mL, [Ca2+]=7.5 mM) with increasing Na+ content. Data are presented as mean ± SD for n = 3 independent experiments. e Fluorescence images of SF coacervates with different cation compositions (scale bar=50 µm). f Zeta potential of the SF_Dex solution with different cation compositions. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of n = 3 independent experiments. The highlighted columns in (b, f) indicate the solutions that underwent LLPS. Due to instrumental limitations, samples were diluted to 1/10 their initial concentration before zeta potential measurements. The corresponding data points of the bar graphs in (b, c, d, f) are indicated as triangles.

Next, we determined the zeta potential of the solutions to investigate whether the hydrophobic interactions were induced by charge screening (Fig. 2b). In the absence of Ca2+, the zeta potential of the SF_Dex solution was −17.6 mV. As the Ca2+ concentration increased, the zeta potential became less negative, indicating reduced electrostatic repulsion leading to increased interactions between SF chains. Notably, the solutions that underwent LLPS had zeta potentials close to zero (−5.5 ~ −2.0 mV). This correlation demonstrates that charge screening increases the hydrophobic interactions between SF chains, promoting LLPS. It should be noted that dextran also exists in the solution along with SF. However, the zeta potential of dextran was different from SF with different Ca2+ concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 13). Thus, we ruled out the effect of dextran and safely concluded that the zeta potential data obtained with SF_Dex solutions was the result of charge screening of SF.

On the other hand, monovalent cations can also participate in charge screening48. Unlike Ca2+, we observed that adding monovalent cations did not induce LLPS (Fig. 1h; Supplementary Fig. 9). To explain this observation, we analyzed the zeta potential of SF_Dex solutions with monovalent sodium ions (Na+; Fig. 2c) and potassium ions (K+; Supplementary Fig. 14) as controls for Ca2+. The monovalent cations also increased the negative zeta potential close to zero. However, while 7.5 mM of Ca2+ induced a zeta potential of SF to −5.5 mV, monovalent cations required higher concentrations (≥37.5 mM) to reach a similar zeta potential value. It has been known that divalent cations are more effective for charge screening than monovalent cations49. Interestingly, although the zeta potential approached a similar value near zero charge, the monovalent cations did not induce the LLPS of SF. If the increased hydrophobic interactions via charge screening were the only driving force for the LLPS of SF, LLPS should have occurred with high concentrations of monovalent cations. Therefore, another attractive force, such as salt bridge formation, might be involved in Ca2+-induced LLPS of SF, which is our second proposed mechanism.

The possibility of salt bridge formation was assessed using Na+ and K+ as competitive inhibitors. Since monovalent cations can bind to negatively charged carboxylic groups, they can compete with other multivalent cations49. If salt bridges drive the LLPS of SF, the addition of monovalent cations will disrupt the salt bridges, resulting in a coacervate dissolution similar to what was observed with alginate hydrogels50,51. To quantitatively determine the degree of LLPS, we measured the change in turbidity of the phase-separated solutions after adding Na+ (Fig. 2d; Supplementary Fig. 15a) and K+ (Supplementary Fig. 15b). As expected, the turbidity of the LLPS solutions decreased as the monovalent cation content increased. The dissolution of SF coacervate was also confirmed by a fluorescence microscope when an excess amount of Na+ was added (Fig. 2e). Interestingly, when we added extra Ca2+ (equimolar concentration of the added Na+), the initial LLPS state of the solution was restored (Fig. 2e). This reversibility of LLPS suggests that the reversible exchange of Ca2+ and Na+ takes place at the negative amino acid residues of SF, like other proteins52,53. Several articles report that Ca2+ forms salt bridges between negative amino acid residues of SF12,15,54 and acts as a “sticker” in SF assembly20. Therefore, the salt bridges mediated by Ca2+ are driving the LLPS of SF. Moreover, we also found that the zeta potential remained relatively constant during the inhibition (addition of Na+) and recovery (further addition of Ca2+) processes (Fig. 2f), which suggests that hydrophobic interactions via charge screening remained constant during the regulation of LLPS. This result shows that both the hydrophobic interaction and salt bridge formation are the driving forces of the LLPS of SF.

Calcium ion-induced SF LLPS is mediated by the L-chain

To evaluate the possible interaction sites (i.e., negatively charged amino acids) of SF with Ca2+, we studied the structure of SF using an amino acid sequence provided by UniProt. Among the 5525 amino acids comprising SF (H-chain and L-chain), only 77 are negatively charged (aspartic acid and glutamic acid). While this ratio alone makes the involvement of negatively charged amino acids questionable, the arrangement of these amino acids suggests otherwise (Fig. 3a). Most of the negatively charged amino acids in SF are located in terminal domains of the H-chain (the amino-terminal domain (NTD) and carboxyl-terminal domain (CTD)) and the L-chain. When we consider the pI of each terminal domain, the NTD of the H-chain is negatively charged, while the CTD of the H-chain is positively charged at neutral pH due to the high content of positively charged amino acids (lysine and arginine) located in the CTD. However, the existence of the L-chain, which is linked to the CTD of the H-chain via a disulfide bond, makes the overall charge at this region negative55. Therefore, if Ca2+ plays an important role in inducing the LLPS, any change in the negatively charged domain or region would alter the LLPS behavior.

To confirm this hypothesis, we added 2-mercaptoethanol, which is commonly used to reduce disulfide bonds, to the LLPS solution to detach the L-chain from the H-chain, which consequently changes the overall pI of the CTD region of the H-chain (Fig. 3a). Adding 2.5% 2-mercaptoethanol to the phase-separated solution decreased the density and size of the SF coacervates (Fig. 3b). Moreover, further increasing the concentration of 2-mercaptoethanol to 5% completely dissolved the coacervates. Dithiothreitol (DTT), another commonly used reducing agent, yielded the same result, providing further evidence that the reduction of disulfide bonds disrupted the LLPS. In addition, we repeated the experiment with ethanol to assess whether the amphiphilic structure of 2-mercaptoethanol disrupted LLPS, finding that the addition of up to 5% ethanol did not disturb LLPS. Therefore, we concluded that the reduction of disulfide bonds was responsible for the observed LLPS disruption and, thus, that attachment of the L-chain to the CTD of the H-chain is vital for the induction of LLPS. Moreover, most of the past studies conducted on SF have focused on the H-chain56. Our results suggest that further research on the L-chain might be crucial for a better understanding of the silk spinning mechanism. It should be noted that the SF undergoes hydrolysis during the degumming and regeneration process57,58. Nevertheless, our SDS-PAGE result showed that, although hydrolysis did occur, the SF used in our research retained its native structure, i.e., H-chain and L-chain (Supplementary Fig. 16). Therefore, we confirmed that the fundamental structures we based our hypothesis were still intact.

Acidification yields SF coacervates with shear sensitivity

The SF inside the silk glands is spun into fibers by acidification and shear force59. We prepared phase-separated solutions with different pH values (pH 5.0, 4.5, 4.0, 3.5, and 3.0) to investigate the effect of acidification on the SF coacervates. The pH value of LLPS solutions was controlled by mixing with an equal volume of acidifying solution with the same dextran and Ca2+ concentration as the LLPS solution to maintain the solution in the 2-phase region. The final composition of the LLPS solution was 0.75 % (w/v) of SF, 2.5% (w/v) of dextran, and 37.5 mM of Ca2+. The acidifying solution was titrated in advance to a predefined pH value required to reach a target pH after mixing with the LLPS solution. The shear force was applied using a syringe needle.

At pH 5.0, there was no discernible difference in the coacervates. However, below pH 4.5, the coacervates started to assemble without coalescing (Fig. 4a, b). Next, we applied a shear force by directly stretching the SF coacervates using a syringe needle under an optical microscope (Fig. 4c, d; Supplementary Movies 1–6). There was no noticeable difference in the coacervates at pH 5.0. At pH 4.5, the assembled coacervates started to deform into short fibrils when shear force was applied. Nevertheless, it was still challenging to stretch the coacervates into fibrils. However, after further reducing the pH below 4.0, the assembled coacervates were able to be stretched and drawn out of the solution into fibrils. Furthermore, the drawn fibrils showed an elastic response, recoiling upon detachment from the syringe needle (Supplementary Movie 4). It should be noted that fibrils were also observed from the assembled coacervates at pH below 4.5 without stretching with a syringe needle (Fig. 4b), which formed as a result of the flow generated during pipetting and by the application of coverslips, thus demonstrating the shear sensitivity of SF coacervates under acidic conditions. We also investigated the effect of basic pH (up to 10) on the SF coacervates using various alkaline solutions (NaOH, NH4OH, and Ca(OH)2) and observed inhibition of LLPS. The dissociation of coacervates at alkaline pH is likely due to increased electrostatic repulsion between SF chains60.

a Optical and (b) fluorescence images of silk fibroin (SF) coacervates at different pH values. c Optical and (d) fluorescence images of SF coacervates at different pH values after direct stretching with a syringe needle. The blue arrows in (c) indicate shear-induced fibril formation of coacervates. The white arrows in (b, d) indicate bead-on-a-string structure (c: scale bar=100 µm; a, b, d: scale bar=50 µm). e Panoramic image of a fiber stretched from a droplet of LLPS solution (pH 3.5, [Ca2+]=37.5 mM). f Diffusion coefficient calculated from FRAP measurements of SF coacervates at different pH values ([Ca2+]=37.5 mM). Data are presented as mean ± SD for n = 3 independent experiments. The statistical significance (P < 0.05) of the differences was checked using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s test. A significant difference was found between pH 4.0 and pH 3.0 (P = 0.01651), while no significant differences were observed between pH 3.5 and pH 3.0 (P = 0.06183) or between pH 4.0 and pH 3.5 (P = 0.54017). The corresponding data points of the bar graphs in (f) are indicated as triangels.

Based on the above optical observations, two stages of transition appeared to occur during acidification and applying shear force: 1. connection/assembly of coacervates (pH 4.5) and 2. shear-induced fibril formation ( ≤ pH 4.0). Interestingly, the threshold pH for coacervate assembly, pH 4.5, is similar to the pI of the NTD (pI=4.6) of the SF H-chain (Fig. 3a). It has been reported that the NTD of the H-chain forms a dimer at pH 4.661. Thus, the observed assembly among coacervates at pH 4.5 might be related to the formation of NTD dimers. The reduced electrostatic repulsion of the SF coacervates due to the protonation of the negatively charged SF surface could be another reason for the assembled coacervates. Furthermore, the shear sensitivity of SF and the mechanical strength of silk fibers are attributed mainly to the repetitive domain15,16,17. Considering that the pI of the repetitive domain (including the hydrophilic spacers) is 3.7 (Fig. 3a), the shear-induced fibril formation below pH 4.0 may be due to reduced electrostatic repulsion, leading to increased interactions between the repetitive domains.

In addition, we repeatedly observed a distinct “bead-on-a-string” structure during the transition from coacervates to fibrils (Fig. 4b, d, e; Supplementary Fig.17; Supplementary Movie 6). When a shear force was applied, either by direct stretching with a syringe needle (Fig. 4d) or by flow generated by applying a coverslip (Fig. 4b), fibrils were observed with coacervates strung through the middle, resembling a beaded necklace. To better understand the development of fibrils from coacervates, we observed the stretching process in real-time using an optical microscope (Supplementary Fig. 17; Supplementary Movie 6). Upon stretching, the assembled coacervates were observed to align linearly along the direction of the applied shear force. In this aligned position, we believe that maximum elongation was achieved in the middle of the aligned coacervates, which led to the formation of fibrils. Observation of the drawn-out fibers showed that the fibers consisted of bundles of fibrils that had been further stretched from the bead-on-a-string structures (Fig. 4e). Some unstretched coacervates were also observed to be attached to the middle of the fiber, where they formed a spindle-knot structure, resulting from Rayleigh instability62, commonly observed with artificially spun silk fibers63 and silk fibers in nature64,65.

While detailed analysis is required to explain the formation of bead-on-a-string structures, it may have occurred due to the dimerization of NTD connecting the assembled coacervates, similar to the report by He et al., which suggested that NTD dimerization modulates the assembly of SF micelles61; and also the report by Hagn et al., which presented the importance of NTD dimerization in shear-induced fiber formation of spider silks66. Moreover, the fibrils appearing between coacervates upon stretching may have developed from SF chains unraveled from the coacervates, either in micelles67 or through the simple unfolding of hydrophilic and hydrophobic domains68,69. In addition, similar structures can be found in recent studies on fibrils developed from silk coacervates70,71 and fiber formation by consolidation72. Further study on the bead-on-a-string structure may help elucidate the transition of SF from coacervates to fibrils.

Next, we performed FRAP measurements to determine the effect of different pH values on the diffusivity of the SF chains inside the coacervates (Fig. 4f). Before comparing the SF diffusivity at each pH, we point out that the FRAP behavior of the coacervates was affected by the degree of contact with a glass substrate (Supplementary Fig. 18). Specifically, during FRAP measurements, the coacervates observed at pH 5.0 and 4.5 were in contact with the glass slide and coverslip surfaces. Meanwhile, the coacervates at pH 4.0, 3.5, and 3.0 were positioned between the glasses without interacting with either surface. This difference may have come from increased interfacial tension from the sol-gel transition of SF inside the coacervates. While we chemically modified the glass surfaces with dextran to prevent the wetting of coacervates, the diffusivity of SF still appears to be affected by contact with glass surfaces. Therefore, we determined the diffusion coefficient only at pH 4.0, 3.5, and 3.0.

The diffusion coefficient was not significantly different between pH 4.0 and pH 3.5 (Fig. 4f). However, at pH 3.0, the coacervates showed slower diffusion, indicating the onset of a sol-gel transition inside the coacervates. The sol-gel transition of SF typically indicates a secondary structure transition from random coil to beta sheets60. However, FTIR analysis of the coacervates at different pH values revealed that the secondary structure of SF remained in a random coil state (amide I peak at 1642 cm−1) even at the lowest pH (Supplementary Fig. 19a). In addition, the drawn-out fibers (pH 3.5) existed predominantly in a random coil state (amide I peak at 1638 cm−1). Further investigation using a thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence assay showed that the structural transition occurred 6–8 h after acidification (Supplementary Fig. 19b). These results suggested that acidification primarily induced the shear sensitivity of SF coacervates by increasing the interaction between the SF chains, followed by a delayed secondary structural transition. Similar delayed kinetics have been observed with fibers spun from silk fibroin extracted from the posterior silk gland59.

Pultrusion-based dry spinning of silk fibers from an LLPS solution via acidification

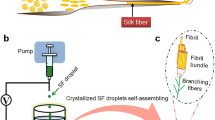

We extended our research to developing fibers from Ca2+-induced SF LLPS solutions by utilizing the effect of acidification and shear force on SF coacervates. For our LLPS system, we opted for a pultrusion-based dry spinning method for fiber production73,74. The dope solution for dry spinning was prepared by the same method used in the above acidification experiment but with a higher SF concentration (6–17% (w/v)). Based on our observations at different pH values (Fig. 4), pH 3.5 was selected as the optimal condition for dry spinning. While dry spinning was also possible at pH 4.0 and pH 3.0, the drawn-out fibers easily disconnected from the dope solution at pH 4.0, making continuous spinning difficult. Moreover, achieving continuous spinning at pH 3.0 was challenging because SF coacervates easily formed aggregates even with low physical agitation.

Adjusting the pH to 3.5 allowed dry spinning with SF concentrations of 6% (w/v), 10% (w/v), and 17% (w/v) (Fig. 5a; Supplemenatry Fig. 20a, b; Supplementary Movies 7, 8). SF solutions with different concentrations all had the same effect, namely that increasing the concentration of SF did not affect LLPS formation (Fig. 5b; Supplementary Fig. 20b). Fluorescence microscopy observation of the spun fibers revealed that the coacervates developed into micro- and nanofibrils, forming a hierarchical structure (Fig. 5c). When the fibers were observed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM), the surface of the fibers exhibited microfibril-like patterns (Fig. 5d). Examining the cross-section of these fibers revealed that the fibers consisted of nanofibrils embedded in a polymeric matrix resembling the natural structure of silk fibers, where the sericin protein layer envelops two strands of SF fibrils (Fig. 5e; Supplementary Fig. 20c). The polymeric matrix may consist of dextran and SF in the dilute phase. Furthermore, the spun fibers quickly dried and solidified in the air in less than 5 min. Automated spinning was also possible by placing the drawn-out fibers on a rotating collector (Fig. 5f; Supplementary Movie 9). This finding shows that by adjusting the pH to 3.5, coacervates could be drawn into fibrils, and other coacervates could be spontaneously collected in the vicinity, suggesting the possibility of automated fiber production.

a Pultrusion-based dry spinning from the LLPS dope solution. b Fluorescence image of the LLPS dope solution without acidification (scale bar = 50 µm). c Fluorescence image of a fiber immediately after spinning (scale bar=200 µm). d SEM image of a spun fiber after drying for 24 h (scale bar=10 µm). e SEM image of the cross-section of a spun fiber after drying for 24 h (scale bar=500 nm). f Automated draw spinning using a step motor. The initial SF concentration used for the above images was 10% (w/v), and the SF concentration in the dope solution was 2.5% (w/v). The dextran and Ca2+ concentrations in the dope solution were 2.5% (w/v) and 37.5 mM, respectively.

It should be noted that the method we used for inducing LLPS and adjusting the pH resulted in the dilution of the SF solution. To create the LLPS condition, we have to add dextran and Ca2+ solution to the initial SF solution. Moreover, an acidifying solution should be added just before spinning. Therefore, the actual SF concentration in the dope solution used for spinning was 1.5–4.25% (w/v), which was one-quarter of the initial SF concentration. A silk fiber dope solution requires a high concentration of SF to obtain sufficient viscosity for the spinning process75,76. To our knowledge, most published studies on artificial silk spinning used a concentrated SF solution above 10% (w/v); few studies have used water as a solvent75,77. For dry spinning, the high concentration requirement becomes more crucial, and it inevitably leads to the use of organic solvents, as obtaining an aqueous SF solution with high concentration and a stable random coil conformation is challenging. This indicates that the high SF concentration and organic solvents frequently used for traditional silk spinning may not be necessary for artificial silk production using LLPS dope solutions. Our results demonstrated that the combination of inducing LLPS and carefully controlling the pH could lead to the development of an efficient, biomimetic silk spinning method.

Nevertheless, a few issues in our dry spinning design must be resolved before mass fiber production can be achieved. While the fibers were elastic right after being drawn from the dope solution, often stretching 2–3 times its initial length (Supplementary Fig. 20d), they rapidly dried and became brittle (strength: 30–40 MPa, elongation at break: ≤0.1). The main reason for the mediocre mechanical properties is the absence of beta sheets (Supplementary Fig. 19a). It may be possible that the Ca2+ used to induce LLPS acted as a chaotropic salt and prevented the structural transition of SF23,78. While the present study accentuates the facile silk fiber production using biomimetic systems, the mechanical properties of the resulting fibers can be improved by adequate post-treatment inducing beta sheets, such as ethanol treatment or post-spinning drawing. Moreover, it should be noted that the current research was conducted using a diluted system compared to the concentrated natural silk dope solution (20–30%)75,79. The behavior characterized using diluted solution, such as the degree of SF condensation inside the coacervates, zeta potential, and FRAP behavior in response to pH, may shift at higher SF concentrations. A detailed study with highly concentrated SF solutions on these properties may help bridge the observation from our current research to understanding the native spinning mechanism more accurately.

Discussion

In summary, we revealed that Ca2+ may act as a key driving force in inducing the LLPS of SF during the silk spinning process. Two mechanisms were proposed for Ca2+-triggered LLPS of SF based on experimental observations: increased hydrophobic interactions via charge screening and salt bridge formation via electrostatic interactions. The LLPS of SF was inhibited by detaching the L-chain from the CTD of the H-chain, suggesting that a terminal domain-specific interaction may exist between Ca2+ and SF. This result suggests that the L-chain may be a crucial structure of SF for silk spinning. We also observed that acidification triggered the assembly of SF coacervates, which subsequently developed into fibrils upon stretching. Finally, we successfully achieved pultrusion-based dry spinning from the aqueous LLPS dope solution. This demonstrates the potential of our spinning systems and provides a guideline for producing fibers with minimal environmental impact and enhanced energy efficiency. Furthermore, we expect our findings to contribute to understanding the silk spinning mechanism, suggesting a link between the recently proposed LLPS of SF and the ionic environment within the silk glands.

Methods

Preparation of the regenerated aqueous silk fibroin solution

Degumming is required to remove the sericin layer which is coating the SF fibers of the silkworm cocoons (provided by the National Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Korea). A 40 g cocoons were cut into four pieces. The cocoon pieces were boiled at 100 °C for 30 min in one liter of an aqueous degumming solution containing 0.2% (w/v) sodium carbonate (Junsei, Japan) and 0.3% (w/v) sodium oleate (Junsei, Japan). Then, the cocoon pieces were boiled again for 30 min with fresh degumming solution. The resulting SF was dried in an oven held at 50 °C.

The obtained SF was dissolved in a 9.3 M LiBr (Alfa Aesar, USA) solution at 60 °C for 4 h. The dissolved solution (10% (w/v)) was dialyzed in a deionized water bath for 3 days using a dialysis tube (6–8 kDa molecular weight cutoff). The temperature of the water bath was kept constant using a refrigerated circulator set at 4 °C. After dialysis, the SF solution was stored at 4 °C until use. The obtained SF had a molecular weight of approximately 344 kDa, which was calculated from the SDS-PAGE data (Supplementary Fig. 16). SF solution that had been stored for fewer than 10 days was used for all experiments. The concentration of the SF solution was measured using a moisture analyzer (MB95, Ohaus, USA). The concentration of the regenerated SF solution was 3.0–3.5% (w/v). The concentration was diluted or concentrated depending on the experiment. For example, to construct a phase separation map, the SF solution was diluted to the desired concentration (0.2–3.0% (w/v)). For fiber spinning, the SF solution was concentrated to 6.0% (w/v)~17.0 % (w/v) by dialyzing against a 20 wt% PEG solution. For the other analyses, an SF solution of 3% (w/v) was used to minimize any agitation caused by diluting the regenerated silk fibroin solution.

Induction of the LLPS of SF

An aqueous solution of SF was mixed with an equal volume of 5% (w/v) aqueous dextran (60–76 kDa; Sigma‒Aldrich, USA) solution and a negligible volume of calcium chloride dihydrate (Sigma‒Aldrich, USA) solution. For instance, 500 µL of SF solution, 500 µL of 5% (w/v) dextran solution, and 25 µL of 1.5 M calcium chloride dihydrate stock solution were mixed using a micropipette to obtain an SF LLPS solution with a Ca2+ concentration of approximately 37.5 mM. The concentration of Ca2+ was controlled by changing the concentration of the stock solution.

In the ion specificity for LLPS induction experiment, the solutions were prepared using the same protocol as that described above. The concentrations of SF and the salt stock solution were fixed at 3% (w/v) and 1.5 M, respectively. The following salts were used for the experiment: FeCl3 (Sigma‒Aldrich, USA), ZnCl2 (Sigma‒Aldrich, USA), CuCl2 (Sigma‒Aldrich, USA), MnCl2 (Sigma‒Aldrich, USA), MgCl2 (Sigma‒Aldrich, USA), NaCl (Merck, Germany), KCl (Sigma‒Aldrich, USA), sodium citrate tribasic dihydrate (Fluka, USA), NaH2PO4 (Sigma‒Aldrich, USA), KI (Sigma‒Aldrich, USA), and KSCN (Sigma‒Aldrich, USA).

Phase separation map

A phase separation map was drawn as a function of the SF and Ca2+ concentrations. The occurrence of LLPS was determined based on changes in turbidity, optical microscopy (Eclipse LV100, Nikon, Japan), and inverted fluorescence microscopy (Celena S, logos Biosystems, Korea). The data points in the phase separation map were classified into three different groups: □ no LLPS; △ LLPS observed after 15 min of mixing SF, dextran, and Ca2+; and ○ LLPS observed immediately after mixing.

Fluorescence microscopy

Fluorescence microscopy images were obtained using an inverted fluorescence microscope. Rhodamine B (Sigma‒Aldrich, USA) and FITC-dextran (70 kDa; Sigma‒Aldrich, USA) were used to label SF and dextran, respectively. The typical mixing process was as follows: 5 µL of 0.02 M rhodamine B solution was mixed with 25 µL of Ca2+ stock solution and 500 µL of 5% (w/v) dextran solution. To label dextran, 5% (w/v) FTIC-dextran was mixed with unlabeled dextran at a 1:9 volume ratio. Afterward, 500 µL of SF solution was mixed using a micropipette. The final solution was dropped on a glass slide and covered with a coverslip for observation. For experiments involving the addition of 1,6-hexanediol (Sigma‒Aldrich, USA), 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma‒Aldrich, USA), dithiothreitol (DTT, Sigma‒Aldrich, USA), or ethanol (Merck, Germany), each compound was mixed with 5% (w/v) dextran solution before mixing with Ca2+ and SF. A panoramic fluorescence image was obtained by connecting multiple low-magnification images.

Turbidity measurements and SF concentration calculations

The turbidity of the solution was quantified by measuring the absorbance at 550 nm using UV‒Vis spectroscopy (Optizen POP, Mecasys, Korea). The solutions were loaded in disposable polystyrene cuvette with a 1 cm pathlength for the measurements. For the SF concentration calculations, a quartz cuvette with a 1 cm pathlength was used. The SF concentration of a solution was determined by using a calibration curve relating SF concentration to absorbance at 278 nm. Each solution was diluted to one one-hundredth of its initial concentration to decrease the absorbance to a reliable range (below 2.0).

Separation of the coacervates from an SF LLPS solution

To separate the coacervate phase from the dilute phase, each LLPS solution was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 min. After centrifugation, the turbid portion of the solution precipitated to the bottom, dividing the solution into two bulk phases: the precipitated bottom phase and the transparent supernatant phase. These phases were separated using a micropipette with caution.

FTIR

The bottom and the supernatant phase of each solution after centrifugation were transferred to separate microtubes, frozen with liquid nitrogen, and freeze-dried for 3 days. For the dry-spun fibers, 4–5 fibers were carefully gathered in a bundle and loaded on an attenuated total reflection (ATR) crystal for measurement. FTIR spectra were measured using an ATR-FTIR instrument (Nicolet summit, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) with 8 cm−1 resolution and 64 scans. For the figures, the full-scan spectra were normalized to the intensity of the amide I peak.

Deconvolution of the amide I peak was performed using OMNIC 9 and Origin 2018 software. In brief, the amide I peak was baseline corrected and processed with the Fourier self-deconvolution (FSD) function in OMNIC. The processed data were fitted with the Peak Analyzer tool provided in the Origin software. Finally, the fitted peaks were each assigned to a secondary structure as described in previous studies80,81,82. The detailed information used for the secondary structure assignment can be found in the supplementary information (Supplementary Table 1). Measurements were repeated five times for each sample for deconvolution.

Acidification of SF coacervates

To adjust the pH without disrupting the coacervates, an LLPS solution was mixed with an equal volume of acidifying solution containing the same concentration of dextran and Ca2+. For example, to change the pH of an LLPS solution with a Ca2+ concentration of 37.5 mM (prepared by mixing 500 µL of 3% (w/v) SF, 500 µL of 5% (w/v) dextran, and 25 µL of 1.5 M Ca2+ stock solution) to 3.5, we mixed an equal volume of an acidifying solution of 2.5% (w/v) dextran and 37.5 mM Ca2+ with a pH value of 2.4. The pH of the acidifying solution required to reach the target pH was predefined, and the solution was titrated in advance. To avoid the introduction of additional cations, pH titration of the acidifying solutions was performed using 1 M HCl (Duksan, Korea) and an aqueous solution of 2.5% (w/v) dextran and 37.5 mM Ca2+. Afterward, the pH-adjusted SF coacervates were transferred to glass slides for observation using optical and fluorescence microscopy. Special care was given to minimize the shear force applied to the SF coacervates during mixing and transfer via a micropipette. Shear force was applied by manually stretching the SF coacervates using a syringe needle.

CD and ThT analyses

CD analysis was performed using a circular dichroism detector (Chirascan plus, Applied Photophysics, UK) to analyze the secondary structure of SF. The LLPS solution was loaded in a 0.01 mm pathlength cuvette without dilution. Each sample was measured three times and smoothed (window size 3) using Chirascan software.

We performed thioflavin T (ThT; Sigma‒Aldrich, USA) fluorescence analysis to evaluate the formation of the beta-sheet structure of SF. First, the pH of the LLPS solution was adjusted. The detailed method for adjusting the pH is explained in the “Acidification of SF coacervates” section. Next, 1 µL of 2 mM ThT was mixed with 200 µL of pH-adjusted LLPS solution and transferred to a 96-well black plate. The well plate was loaded into a microplate reader (Synergy H1, BioTek, USA) at 25 °C. The change in fluorescence intensity (excitation: 420 nm, emission: 480 nm, sensitivity: 75) was measured every 30 min for 12 h.

Zeta potential measurements

The zeta potential was measured using a Zetasizer Nano ZS90 (Malvern, UK). Due to instrumental limitations, all the samples were diluted to one-tenth of their initial concentration. The diluted samples were transferred to a folded capillary zeta cell for analysis. Each sample was measured three times. Each measurement represents the average of four consecutive readings.

Changing the cation composition

When the cation composition of a solution was changed, a fixed volume of concentrated bulk cation solution was used. For example, the solutions used to obtain the result in Fig. 2e, f were obtained by the following procedure: First, an LLPS solution with a Ca2+ concentration of approximately 7.5 mM was prepared by mixing 25 µL of 300 mM Ca2+ stock solution, 500 µL of 5% (w/v) dextran solution, and 500 µL of 3% (w/v) SF solution. Next, 25 µL of 3.0 M Na+ stock solution was added to the LLPS solution, yielding a Na+ concentration of approximately 75 mM. Finally, 25 µL of 3.0 M Ca2+ solution was added to increase the Ca2+ concentration of the LLPS solution.

A similar method was used to prepare the solution used to obtain the results shown in Fig. 2d. An LLPS solution of 1 mL with a Ca2+ concentration of 7.5 mM was first prepared. Afterward, the Na+ concentration of the LLPS solution was increased by adding 25 µL of 3.0 M Na+ stock solution at a time.

Amino acid composition and pI calculation

The content of aspartic acid and glutamic acid in SF was calculated by using the information found in UniProt (heavy chain (H-chain): entry P05790; light chain (L-chain): entry P21828). The pI value of each domain was calculated using the ExPASy pI calculator.

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP)

The glass slides and coverslips used for FRAP measurements were chemically modified with CM-dextran using EDC/NHS chemistry83,84. The glass surfaces were cleaned using NaOH (Samchun, Korea), soap, and ethanol before surface modification85. The clean glassware was placed in a 3% (v/v) (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES; Sigma‒Aldrich, USA)/ethanol solution for 2 h. The amidated glassware was sonicated in ethanol for 5 min, rinsed with ethanol, and dried using nitrogen gas. Next, a reaction solution containing 3% (w/v) CM-dextran (Sigma‒Aldrich, USA), 50 mM 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC; Sigma‒Aldrich, USA), and 50 mM N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS; Sigma‒Aldrich, USA) was prepared. The pH of the solution was adjusted to 7 before the amidated glassware was added. The reaction was carried out for 18 h at room temperature with gentle rocking. Finally, the glassware was rinsed with deionized water and dried with nitrogen gas.

Fluorescence-labeled SF was synthesized with rhodamine B isothiocyanate (RBITC; Sigma‒Aldrich, USA). RBITC was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma‒Aldrich, USA) to a concentration of 8 mg/mL. The pH of the 3% (w/v) SF solution was adjusted to 9 using 0.1 M sodium carbonate (Junsei, Japan). Next, the RBITC and SF solutions were mixed at a ratio of 1:5 (v/v) and kept in the dark at 4 °C for 8 h. Afterward, the solution was dialyzed (6–8 kDa molecular weight cutoff) in the dark at 4 °C for 4 days against deionized water. The obtained RBITC-labeled SF was mixed with unlabeled SF at a ratio of 1:9 (v/v) before analysis.

The FRAP experiments were performed using an SP8 X Leica confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica, Germany) with a 40x water immersion objective. An LLPS solution was prepared as described in the “Phase separation map” section with 3% (w/v) SF solution mixed with RBITC-labeled SF. A sample for FRAP was prepared by dropping 25 µL of LLPS solution onto dextran-modified glass slides. The droplet was covered with a dextran-modified coverslip (24×40 mm), and the edges around the coverslip were coated with commercial nail polish. This process reduces coacervate drift during FRAP measurements. Drift occurs because of the convection generated by the evaporation of the solution at the liquid-air interface around the coverslip. Applying a coating at the interface prevents evaporation and hence improves the stability of the coacervates. Nail polish was applied at least one hour before measurements to ensure that the coating was sufficiently dry.

The coacervates were partially bleached (4 µm in diameter) with 20% laser power for 15 s. Postbleach recovery images were acquired at 0.433 s intervals. The fluorescence intensities from three regions of interest (ROIs) were used for the correction and normalization processes: 1. photobleached area; 2. background; and 3. whole image. The fluorescence intensities were corrected and normalized using the following equations to account for the background signals and photofading86:

The diffusion coefficient was derived according to the method used by Ray et al.87. Briefly, the Inormalized(t) curves were fitted to an exponential decay function using Origin software. From the fitted function, the half-time to full recovery was defined and subsequently converted to the diffusion coefficient.

Pultrusion-based dry spinning of SF LLPS solutions

First, the SF solution was concentrated by dialysis against a 20 wt% PEG solution (MW 20,000; Sigma‒Aldrich, USA) using a 3.5 kDa molecular weight cutoff dialysis tube. Dialysis was performed at 4 °C for 18 h while the PEG solution was stirred with a magnetic stirrer at 80 rpm. The concentration of the resulting SF solution was determined using a moisture analyzer. The resulting concentration of SF was 15–17% (w/v). The obtained SF solution was diluted to reach the target concentration.

The dope solution for dry spinning was prepared by mixing the LLPS solution with an acidifying solution. The concentrated SF solution (500 µL) was mixed with 5% (w/v) dextran solution (500 µL) and 25 µL of 1.5 M Ca2+ stock solution to induce LLPS (Ca2+, 37.5 mM). Next, the LLPS solution was acidified to pH 3.5 by following the procedure described in the “Acidification of SF coacervates” section. The pH of the acidifying solution required to reach a final pH of 3.5 was measured prior to use. To minimize unwanted agitation/shear, the LLPS and acidifying solutions were directly mixed on top of a flat surface. Fibers were drawn from the LLPS solution using tweezers. Fluorescence images were obtained immediately after repeating this process on a glass slide. The detailed morphology of the drawn fibers was analyzed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Sigma, Carl Zeiss, UK). The drawn fibers were sufficiently dried for 24 h and sputter-coated with Pt to a thickness of approximately 5 nm. The samples for SEM cross-section imaging were prepared by cutting the fibers using a scissor. For automated spinning, the drawn fibers were attached to a rotating collector. The collector was rotated using an Arduino step motor. The fiber collector was designed using a CAD program and printed using a DLP printer (Photon Mono 4k, Anycubic, China). The spun fibers were air-dried in a fume hood.

Statistical analysis and reproducibility

The deconvolution of the FTIR amide I spectra was conducted five times. All other analyses were conducted three times. The zeta potential data are presented as a mean value with standard error. All other analyses data are presented as a mean value with standard deviation. The statistical significance (P < 0.05) of the differences was checked using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s test, which was performed with Origin 2018 software. All imaging has been performed more than three times with similar observations.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this research are available within the article, supplementary information, or source data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Omenetto, F. G. & Kaplan, D. L. New opportunities for an ancient material. Science 329, 528–531 (2010).

Qiu, W., Patil, A., Hu, F. & Liu, X. Y. Hierarchical structure of silk materials versus mechanical performance and mesoscopic engineering principles. Small 15, https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201903948 (2019).

Mita, K., Ichimura, S. & James, T. C. Highly repetitive structure and its organization of the silk fibroin gene. J. Mol. Evol. 38, 583–592 (1994).

Inoue, S. et al. Silk fibroin of Bombyx mori is secreted, assembling a high molecular mass elementary unit consisting of H-chain, L-chain, and P25, with a 6:6:1 molar ratio. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 40517–40528 (2000).

Koh, L. D. et al. Structures, mechanical properties and applications of silk fibroin materials. Prog. Polym. Sci. 46, 86–110 (2015).

Jin, H. J. & Kaplan, D. L. Mechanism of silk processing in insects and spiders. Nature 424, 1057–1061 (2003).

Bini, E., Knight, D. P. & Kaplan, D. L. Mapping domain structures in silks from insects and spiders related to protein assembly. J. Mol. Biol. 335, 27–40 (2004).

Bauer, J. & Scheibel, T. Dimerization of the conserved N-terminal domain of a spider silk protein controls the self-assembly of the repetitive core domain. Biomacromolecules 18, 2521–2528 (2017).

Holland, C., Vollrath, F., Ryan, A. J. & Mykhaylyk, O. O. Silk and synthetic polymers: Reconciling 100 degrees of separation. Adv. Mater. 24, 105–109 (2012).

Vollrath, F. & Porter, D. Silks as ancient models for modern polymers. Polymer 50, 5623–5632 (2009).

Domigan, L. J. et al. Carbonic anhydrase generates a pH gradient in Bombyx mori silk glands. Insect Biochem. Mol. 65, 100–106 (2015).

Foo, C. W. P. et al. Role of pH and charge on silk protein assembly in insects and spiders. Appl Phys. a-Mater. 82, 223–233 (2006).

Miyake, S. & Azuma, M. Acidification of the Silk Gland Lumen in Bombyx mori and Samia cynthia ricini and Localization of H+-Translocating Vacuolar-Type ATPase. J. Insect Biotechnol. Sericology 77, 1_9–1_16 (2008).

Sparkes, J. & Holland, C. Analysis of the pressure requirements for silk spinning reveals a pultrusion dominated process. Nat Commun 8, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00409-7 (2017).

Iizuka, E. Silk thread: mechanism of spinning and its mechanical properties. Appl. Polym. Symp. 41, 173–185 (1985).

Xie, F., Zhang, H. H., Shao, H. L. & Hu, X. C. Effect of shearing on formation of silk fibers from regenerated Bombyx mori silk fibroin aqueous solution. Int J. Biol. Macromol. 38, 284–288 (2006).

Yamaura, K., Okumura, Y., Ozaki, A. & Matsuzawa, S. Flow-induced crystallization of Bombyx-Mori L silk fibroin from regenerated aqueous-solution and spinnability of its solution. Appl. Polym. Symp. 41, 205–220 (1985).

Zhou, L., Chen, X., Shao, Z. Z., Huang, Y. F. & Knight, D. P. Effect of metallic ions on silk formation the mulberry silkworm, Bombyx mori. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 16937–16945 (2005).

Liu, Q. S. et al. Dynamic changes and characterization of the metal ions in the silk glands and silk fibers of silkworm. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24076556 (2023).

Schaefer, C., Laity, P. R., Holland, C. & McLeish, T. C. B. Silk protein solution: A natural example of sticky reptation. Macromolecules 53, 2669–2676 (2020).

Koeppel, A., Laity, P. R. & Holland, C. The influence of metal ions on native silk rheology. Acta Biomater. 117, 204–212 (2020).

Dubey, P., Murab, S., Karmakar, S., Chowdhury, P. K. & Ghosh, S. Modulation of self-assembly process of fibroin: An insight for regulating the conformation of silk biomaterials. Biomacromolecules 16, 3936–3944 (2015).

Zhou, P. et al. Effects of pH and calcium ions on the conformational transitions in silk fibroin using 2D Raman correlation spectroscopy and 13C solid-state NMR. Biochem.-Us 43, 11302–11311 (2004).

Wei, W. et al. Bio-inspired capillary dry spinning of regenerated silk fibroin aqueous solution. Mat. Sci. Eng. C.-Mater. 31, 1602–1608 (2011).

Akai, H. The structure and ultrastructure of the silk gland. Experientia 39, 443–449 (1983).

Vollrath, F. & Knight, D. P. Liquid crystalline spinning of spider silk. Nature 410, 541–548 (2001).

Tanaka, T., Suzuki, M., Kuranuki, N., Tanigami, T. & Yamaura, K. Properties of silk fibroin/poly(vinyl alcohol) blend solutions and peculiar structure found in heterogeneous blend films. Polym. Int 42, 107–111 (1997).

Jin, H. J., Fridrikh, S. V., Rutledge, G. C. & Kaplan, D. L. Electrospinning Bombyx mori silk with poly(ethylene oxide). Biomacromolecules 3, 1233–1239 (2002).

Park, D. et al. pH-triggered silk fibroin/alginate structures fabricated in aqueous two-phase system. Acs Biomater. Sci. Eng. 5, 5897–5905 (2019).

Shen, Y. et al. Biomolecular condensates undergo a generic shear-mediated liquid-to-solid transition. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 841–847 (2020).

Eliaz, D. et al. Micro and nano-scale compartments guide the structural transition of silk protein monomers into silk fibers. Nat Commun 13, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-35505-w (2022).

Malay, A. D. et al. Spider silk self-assembly via modular liquid-liquid phase separation and nanofibrillation. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb6030 (2020).

Soltys, K., Tarczewska, A. & Bystranowska, D. Modulation of biomolecular phase behavior by metal ions. Bba-Mol Cell Res. 1870, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamcr.2023.119567 (2023).

Miserez, A., Yu, J. & Mohammadi, P. Protein-based biological materials: Molecular design and artificial production. Chem. Rev. 123, 2049–2111 (2023).

Dubey, P., Seit, S., Chowdhury, P. K. & Ghosh, S. Effect of macromolecular crowders on the self-assembly process of silk fibroin. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 221, 2000113 (2020).

Park, S. et al. Dehydration entropy drives liquid-liquid phase separation by molecular crowding. Commun. Chem. 3, 83 (2020).

Wang, X. et al. In vivo effects of metal ions on conformation and mechanical performance of silkworm silks. Bba-Gen. Subj. 1861, 567–576 (2017).

Zong, X. H. et al. Effect of pH and copper(II) on the conformation transitions of silk fibroin based on EPR, NMR, and Raman spectroscopy. Biochem.-Us 43, 11932–11941 (2004).

Donati, I., Asaro, F. & Paoletti, S. Experimental evidence of counterion affinity in alginates: The case of nongelling ion Mg2+. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 12877–12886 (2009).

Huynh, U. T. D., Lerbret, A., Neiers, F., Chambin, O. & Assifaoui, A. Binding of divalent cations to polygalacturonate: A mechanism driven by the hydration water. J. Phys. Chem. B 120, 1021–1032 (2016).

Liu, Q. S. et al. A strategy for improving the mechanical properties of silk fiber by directly injection of ferric ions into silkworm. Mater. Des. 146, 134–141 (2018).

Ji, D., Deng, Y. B. & Zhou, P. Folding process of silk fibroin induced by ferric and ferrous ions. J. Mol. Struct. 938, 305–310 (2009).

Slotta, U. K., Rammensee, S., Gorb, S. & Scheibel, T. An engineered spider silk protein forms microspheres. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. 47, 4592–4594 (2008).

Zhang, Y. J. & Cremer, P. S. Chemistry of hofmeister anions and osmolytes. Annu Rev. Phys. Chem. 61, 63–83 (2010).

Shin, Y. & Brangwynne, C. P. Liquid phase condensation in cell physiology and disease. Science 357, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf4382 (2017).

Muzzopappa, F. et al. Detecting and quantifying liquid–liquid phase separation in living cells by model-free calibrated half-bleaching. Nat Commun 13, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-35430-y (2022).

Sabari, B. R. et al. Coactivator condensation at super-enhancers links phase separation and gene control. Science 361, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aar3958 (2018).

Krainer, G. et al. Reentrant liquid condensate phase of proteins is stabilized by hydrophobic and non-ionic interactions. Nat Commun 12, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21181-9 (2021).

Matsarskaia, O., Roosen-Runge, F. & Schreiber, F. Multivalent ions and biomolecules: Attempting a comprehensive perspective. Chemphyschem 21, 1742–1767 (2020).

LeRoux, M. A., Guilak, F. & Setton, L. A. Compressive and shear properties of alginate gel: Effects of sodium ions and alginate concentration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 47, 46–53 (1999).

Qin, Y. M. Alginate fibres: an overview of the production processes and applications in wound management. Polym. Int 57, 171–180 (2008).

Iwaki, M. et al. Structure-affinity insights into the Na+ and Ca2+ interactions with multiple sites of a sodium-calcium exchanger. Febs J. 287, 4678–4695 (2020).

Jordan, E. et al. Competing salt effects on phase behavior of protein solutions: Tailoring of protein interaction by the binding of multivalent ions and charge screening. J. Phys. Chem. B 118, 11365–11374 (2014).

Ochi, A., Hossain, K. S., Magoshi, J. & Nemoto, N. Rheology and dynamic light scattering of silk fibroin solution extracted from the middle division of Bombyx mori silkworm. Biomacromolecules 3, 1187–1196 (2002).

Lammel, A. S., Hu, X., Park, S. H., Kaplan, D. L. & Scheibel, T. R. Controlling silk fibroin particle features for drug delivery. Biomaterials 31, 4583–4591 (2010).

Hao, Z. Z. et al. New insight into the mechanism of in vivo fibroin self-assembly and secretion in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Int J. Biol. Macromol. 169, 473–479 (2021).

Wang, H. Y. & Zhang, Y. Q. Effect of regeneration of liquid silk fibroin on its structure and characterization. Soft Matter 9, 138–145 (2013).

Moreno-Tortolero, R. O. et al. Molecular organization of fibroin heavy chain and mechanism of fibre formation in Bombyx mori. Commun Biol 7, https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-06474-1 (2024).

Koeppel, A., Stehling, N., Rodenburg, C. & Holland, C. Spinning beta silks requires both pH activation and extensional stress. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202103295 (2021).

Matsumoto, A. et al. Mechanisms of silk fibroin sol-gel transitions. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 21630–21638 (2006).

He, Y. X. et al. N-terminal domain of Bombyx mori fibroin mediates the assembly of silk in response to pH decrease. J. Mol. Biol. 418, 197–207 (2012).

Haefner, S. et al. Influence of slip on the Plateau-Rayleigh instability on a fibre. Nat Commun 6, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8409 (2015).

Peng, Q. F., Shao, H. L., Hu, X. C. & Zhang, Y. P. The development of fibers that mimic the core-sheath and spindle-knot morphology of artificial silk using microfluidic devices. Macromol Mater. Eng. 302, https://doi.org/10.1002/mame.201700102 (2017).

Zheng, Y. M. et al. Directional water collection on wetted spider silk. Nature 463, 640–643 (2010).

Li, J., Li, J. Q., Sun, J., Feng, S. & Wang, Z. Biological and engineered topological droplet rectifiers. Adv. Mater. 31, 1806501 (2019).

Hagn, F., Thamm, C., Scheibel, T. & Kessler, H. pH-dependent dimerization and salt-dependent stabilization of the N-terminal domain of spider dragline silk—implications for fiber formation. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. 50, 310–313 (2011).

Greving, I., Cai, M., Vollrath, F. & Schniepp, H. C. Shear-induced self-assembly of native silk proteins into fibrils studied by atomic force microscopy. Biomacromolecules 13, 676–682 (2012).

Zhang, W. K. et al. Single-molecule force spectroscopy on Bombyx mori silk fibroin by atomic force microscopy. Langmuir 16, 4305–4308 (2000).

Shulha, H., Foo, C. W. P., Kaplan, D. L. & Tsukruk, V. V. Unfolding the multi-length scale domain structure of silk fibroin protein. Polymer 47, 5821–5830 (2006).

Miali, M. E., Eliaz, D., Solomonov, A. & Shimanovich, U. Microcompartmentalization Controls Silk Feedstock Rheology. Langmuir 39, 8984–8995 (2023).

Fan, R. X. et al. Sustainable spinning of artificial spider silk fibers with excellent toughness and inherent potential for functionalization. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2410415 (2024).

Wan, Q. et al. Mesoscale structure development reveals when a silkworm silk is spun. Nat Commun 12, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23960-w (2021).

Li, X. et al. Customized flagelliform spidroins form spider silk-like fibers at pH 8.0 with outstanding tensile strength. Acs Biomater. Sci. Eng. 8, 119–127 (2022).

Välisalmi, T., Bettahar, H., Zhou, Q. & Linder, M. B. Pulling and analyzing silk fibers from aqueous solution using a robotic device. Int. J. Biol. Macromol 250, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.126161 (2023).

Koeppel, A. & Holland, C. Progress and trends in artificial silk spinning: A systematic review. Acs Biomater. Sci. Eng. 3, 226–237 (2017).

Wöltje, M., Isenberg, K. L., Cherif, C. & Aibibu, D. Continuous wet spinning of regenerated silk fibers from spinning dopes containing 4% fibroin protein. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241713492 (2023).

Xu, Z. P. et al. Spinning from nature: Engineered preparation and application of high-performance bio-based fibers. Engineering 14, 100–112 (2022).

Oktaviani, N. A., Matsugami, A., Hayashi, F. & Numata, K. Ion effects on the conformation and dynamics of repetitive domains of a spider silk protein: implications for solubility and β-sheet formation. Chem. Commun. 55, 9761–9764 (2019).

Laity, P. R., Gilks, S. E. & Holland, C. Rheological behaviour of native silk feedstocks. Polymer 67, 28–39 (2015).

Hu, X., Kaplan, D. & Cebe, P. Determining beta-sheet crystallinity in fibrous proteins by thermal analysis and infrared spectroscopy. Macromolecules 39, 6161–6170 (2006).

Kasoju, N., Hawkins, N., Pop-Georgievski, O., Kubies, D. & Vollrath, F. Silk fibroin gelation via non-solvent induced phase separation. Biomater. Sci. 4, 460–473 (2016).

Zhang, H. P. et al. Enhancing effect of glycerol on the tensile properties of Bombyx mori cocoon sericin films. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 12, 3170–3181 (2011).

Bart, J. et al. Room-temperature intermediate layer bonding for microfluidic devices. Lab Chip 9, 3481–3488 (2009).

Saftics, A. et al. Fabrication and characterization of ultrathin dextran layers: Time dependent nanostructure in aqueous environments revealed by OWLS. Colloids Surf. B: Biointerfaces 146, 861–870 (2016).

Lau, A. W. C., Prasad, A. & Dogic, Z. Condensation of isolated semi-flexible filaments driven by depletion interactions. Europhys. Lett. 87, 48006 (2009).

Kang, M. C., Andreani, M. & Kenworthy, A. K. Validation of normalizations, scaling, and photofading corrections for FRAP data analysis. Plos One 10, e012966 (2015).

Ray, S. et al. α-Synuclein aggregation nucleates through liquid-liquid phase separation. Nat. Chem. 12, 705–716 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government. (MIST) (grant number NRF-2020R1A2C1012179 (K.H.L.)).

Author information