Abstract

Chemical recycling of plastic waste could reduce its environmental impact and create a more sustainable society. Hydrogenolysis is a viable method for polyolefin valorization but typically requires high hydrogen pressures to minimize methane production. Here, we circumvent this stringent requirement using dilute RuPt alloy to suppress the undesired terminal C–C scission under hydrogen-lean conditions. Spectroscopic studies reveal that PE adsorption takes place on both Ru and Pt sites, yet the C–C bond cleavage proceeds faster on Ru site, which helps avoid successive terminal scission of the in situ-generated reactive intermediates due to the lack of a neighboring Ru site. Different from previous research, this method of suppressing methane generation is independent of H2 pressure, and PE can be converted to fuels and waxes/lubricant base oils with only <3.2% methane even under ambient H2 pressure. This advantage would allow the integration of distributed, low-pressure hydrogen sources into the upstream of PE hydrogenolysis and provide a feasible solution to decentralized plastic upcycling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plastics have been an indispensable part in modern society because of their versatile properties, long lifespan, and low cost. They are widely used in various industries, including packaging, healthcare, transportation, consumer electronics, building, and construction1,2. However, the growing production and widespread use of plastics have placed significant stress on the environment, particularly on the aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems3,4. Polyethylene (PE) is the most extensively used plastic, with an annual consumption of 102.9 million metric tons globally5. The majority of PE products were ultimately disposed of in landfills or through incineration6. Recycling and repurposing plastic wastes can reduce their carbon footprint and enable a circular economy. It necessitates a comprehensive waste management system and, more importantly, low-cost technologies for decentralized plastic processing.

Chemical upcycling is an effective approach to waste valorization by converting post-consumer plastics into monomers or value-added molecules. The chemical breakdown of PE can be achieved by a variety of methods, including hydrogenolysis7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18, hydrocracking19,20,21, cracking22,23, pyrolysis24,25,26,27,28, oxidation29,30, and tandem catalysis31,32,33,34,35. Hydrogenolysis is of particular interest because it produces valuable fuels and chemicals at relatively low reaction temperatures. Supported Pt and Ru nanoparticles have been commonly used to catalyze the hydrogenolysis of polyolefins7,10,13,14. For instance, Pt/SiO2 covered by a mesoporous silica shell has been demonstrated to control the product distributions via a processive mechanism36. Compared with Pt, Ru-based catalysts exhibit higher activity7,8,10, but tend to promote terminal C–C scission at low hydrogen pressures, resulting in significant methane production37. Methane is an undesirable product for its low value and high H2 consumption38, which would consume 20 times more H2 than producing the same weight of n-eicosane (C20). The concentration of atomic hydrogen (H*) on the catalyst surface has been identified as one of the key factors influencing the methane yield in hydrogenolysis. High H* surface coverage, as often provided by elevated H2 pressures (2–5 MPa), is required to minimize the terminal C–C bond cleavage and suppress methane generation8,14. Vlachos and co-workers have employed H2 storage material to increase the H* surface coverage on Ru via reverse spillover to increase the production of liquid fuels9,37. Sub-nanometer Ru clusters10 and isolated Ru sites11 were reported to be more favorable for internal C–C bond cleavage than large nanoparticles. However, high H2 pressures (>2 MPa) have been inevitably involved in these processes (Supplementary Table 1).

Polyolefin hydrogenolysis at low H2 pressure is more desirable because it can reduce cost, improve safety, and make the process more energy-efficient. Prior mechanistic studies on short-chain alkane hydrogenolysis can help us identify potential ways to control the product distribution at low H2 pressures39,40,41,42. The alkane hydrogenolysis includes a series of elementary steps (Supplementary Note, equations 1.1–1.8). The 1st C–C bond cleavage results in the formation of two hydrocarbon fragments, which bond to the catalyst surface through their terminal C-atoms (Fig. 1, step 1.4). These fragments can be hydrogenated by H* and desorb to form n-alkanes (Fig. 1, step 1.5). Thus, increasing the H* surface coverage can expedite this step and promote the production of long-chain hydrocarbons, as demonstrated in previous studies9,10,32. Alternatively, these fragments can undergo consecutive dehydrogenation (Fig. 1, step 1.6) and suffer the 2nd C–C bond cleavage (Fig. 1, step 1.7), especially on H*-lean surface. This step is considered to be crucial for the undesired terminal scission. Under low H2 pressure conditions, the previous method of accelerating step 1.5 via high H* coverage would fall short, requiring the development of new strategies.

The hydrogenolysis consists of a series of elementary steps (step 1.1–step 1.8), including H2 dissociation (step 1.1), alkane adsorption (step 1.2) and dehydrogenation (step 1.3), the 1st C–C bond cleavage to form hydrocarbon fragments (step 1.4), the hydrogenation and desorption of these fragments to form n-alkanes (step 1.5). After step 1.4, an alternative reaction pathway could occur through the consecutive dehydrogenation of the hydrocarbon fragments (step 1.6), the 2nd C–C bond cleavage (step 1.7), and the hydrogenation of methyl group (step 1.8).

Here, we use dilute Ru9Pt91 alloy to achieve low methane selectivity with H2-pressure independence by suppressing the 2nd C–C bond cleavage (Fig. 1, step 1.7). We demonstrate that the cleavage of the C–C bond proceeds more rapidly on the Ru site than Pt site. Thus, the dilution of the Ru sites by Pt would not influence the 1st C–C bond cleavage on the Ru site but retard the successive terminal scission on the neighboring Pt site. Because surface H* does not directly participate in the 2nd C–C bond cleavage elementary step (Fig. 1, step 1.7), this dilute alloy is effective even under hydrogen-lean conditions. Other dilute RuM (M = Pd, Co, Ni) alloy catalysts (e.g., Ru9Pd91, Ru6Co94, and Ru14Ni86) are also investigated, but they do not work well at low hydrogen pressures, highlighting the importance of Pt for PE adsorption and H2 dissociation. We further showcase that the Ru9Pt91 can convert real-world PE wastes into liquid fuels and waxes/lubricant base oils with less than 3.2% methane generated under ambient H2 pressure, enabling the seamless integration of decentralized water electrolysis into the upstream of plastic waste valorization.

Results

Catalyst characterization

The RuPt nanoparticles (NPs) were synthesized by a colloidal method as described in the Supplementary Material. Transmission electron microscopic (TEM) analysis reveals that the RuPt NPs are monodispersed with an average diameter of approximately 3.8 ± 0.2 nm (Fig. 2a). The composition of the NPs is Ru9Pt91 as determined by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES). The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the Ru9Pt91 NPs show the characteristic diffraction peaks of face-centered cubic (fcc) Pt (Supplementary Fig. 1), which can be assigned to (111), (200), and (220) reflections (PDF#04-0802). The Ru9Pt91 NPs were then loaded onto a carbon support (Vulcan XC72) to prevent particle aggregation (Fig. 2b), denoted as Ru9Pt91/C. The high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) image of a Ru9Pt91 particle is depicted in Fig. 2c. The continuous lattice fringes suggest that the particle is a single crystal. The distances between the adjacent lattice fringes are measured to be 0.19 nm and 0.22 nm, in good agreement with the lattice spacings of Pt (200) and Pt (111) planes, respectively. The energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mapping demonstrates an even distribution of Pt and Ru atoms across the particle (Fig. 2d). For comparison, we also synthesized monodispersed Pt NPs, Ru NPs, and RuPt NPs with ICP compositions of Ru25Pt75 and Ru41Pt59, respectively. The characterizations of these samples are shown in Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3.

a The TEM image of as-synthesized Ru9Pt91 NPs (scale bar, 100 nm). The inset shows the diameter histogram. b The HAADF-STEM image of Ru9Pt91 NPs supported on carbon (scale bar, 50 nm). c The HAADF-STEM image of a Ru9Pt91 NP. The inset shows the corresponding fast Fourier transform (FFT) (scale bar, 1 nm). d EDS mapping of a representative Ru9Pt91 NP (scale bar, 1 nm). e, f Fourier transforms of EXAFS spectra of Ru K-edge (e) and Pt L3-edge (f). g, h Quasi in situ XPS spectra of Pt 4f (g) and Ru 3p (h) for reduced Pt NPs, Ru9Pt91, Ru25Pt75, Ru41Pt59, and Ru NPs.

The structure of the dilute Ru9Pt91 alloy is further characterized by the extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS). The Fourier transform of EXAFS at Ru K-edge is shown in Fig. 2e and analyzed in k- and R- space (Supplementary Fig. 4). The Ru9Pt91 displays a main peak at 1.48 Å, which can be assigned to the Ru–O scattering path (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 2), while the second shell Ru–O–Ru scattering in RuO2 at 3.21 Å is absent in Ru9Pt91. This observation suggests that the surface of Ru9Pt91 is partially oxidized when exposed to air, which is further confirmed by X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) (Supplementary Fig. 5a) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (Supplementary Fig. 5b). The weak peak at R-space of 2.17 Å for Ru9Pt91 can be attributed to the scattering of the Ru–Pt bond, and the peak at higher R space of 2.72 Å can be attributed to the scattering of the Ru–O–Pt (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 2). The peak corresponding to the Ru−Ru scattering path (2.36 Å) is not observed and cannot be fitted in Ru9Pt91, suggesting that the Ru sites are diluted in the sample. The Fourier transform of EXAFS spectra at the Pt L3-edge is shown in Fig. 2f. The intensive peak at 2.31 Å for Pt foil corresponds to the Pt–Pt and Pt–Ru scattering path as observed in the wavelet transform of EXAFS (WT-EXAFS) (Supplementary Fig. 6c). The fitting results for Ru9Pt91 indicate the coordination number (CN) for Pt-Ru pair is 0.7, corresponding to the dilute Ru9Pt91 alloy (Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 3). Considering PE hydrogenolysis is performed under a reducing atmosphere, quasi in situ XPS was carried out to characterize the surface properties of the catalyst under reaction-relevant conditions. The samples were pretreated at 300 °C with H2 flow (10 mL min−1) in a reaction chamber for an hour and then transferred to an XPS chamber under vacuum. The XPS spectra of Pt 4f (Fig. 2g) and Ru 3p (Fig. 2h) reveal that both the Pt species and the Ru species in the samples are in a metallic state under the reaction-relevant conditions.

PE hydrogenolysis evaluation

PE with an average Mw of 4000 g mol−1 (Sigma-Aldrich, 427772, m.p. 107.1 °C) was employed to evaluate the catalytic performance of the dilute Ru9Pt91 alloy. The reaction was performed at 300 °C at a H2 pressure of 0.5 MPa. Figure 3a depicts the time courses of PE hydrogenolysis over Ru9Pt91/C. In the initial stage of the reaction, the solid gradually decreased as the reaction progressed. All the solid was completely converted by 12 h. At this point, long-chain alkanes (C5~C40) were the main products (yield: 81.2%), with 1.5% C2~C4 and 1.2% CH4. After 12 h, the long-chain alkanes were continuously converted into lighter alkanes, as reflected by the detailed carbon distributions (Supplementary Fig. 7). Specifically, the carbon distribution at a 4-h reaction exhibited a narrow profile, with approximately 70% of the products being waxes/lubricant base oils (C20~C40, centered around C27, Supplementary Fig. 7). This distribution pattern remained largely unchanged during the first 8 h of hydrogenolysis. However, with prolonged reaction time, a new distribution centered around C15 gradually evolved and became predominant (Supplementary Fig. 7). Notably, the methane selectivity remained below 2.6% during the entire course of the hydrogenolysis.

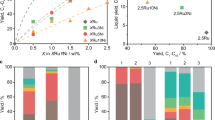

a–c Time courses of PE hydrogenolysis over Ru9Pt91/C (a), Pt/C (b) and Ru/C (c), where the product yields are presented in mass percentage. More detailed carbon distributions are presented in Supplementary Fig. 7. Reaction conditions: 0.5 MPa H2, 300 °C, 340 mg PE, 20 mg catalyst. d The effects of Ru content in RuPt alloy on the methane selectivity at a H2 consumption around 1.75 mmol under 0.5 MPa H2. e Methane selectivity for PE hydrogenolysis under different hydrogen pressures catalyzed by Ru9Pt91/C and Ru/C at H2 consumption around 1.75 mmol. f PE hydrogenolysis over Ru9Pt91/C, Ru14Ni86/C, Ru6Co94/C, and Ru9Pd91/C. Reaction conditions: 0.5 MPa H2, 300 °C, 340 mg PE, 0.5 mg Ru, 8 h. The error bars represent the standard deviations of three independent measurements.

For comparison, the catalytic performance of carbon-supported Pt and Ru NPs was also examined. The hydrogenolysis of PE over Pt/C catalyst was quite sluggish, showing a solid conversion of a mere 8.5% at 8 h and 16.8% at 24 h (Fig. 3b). Notably, 0.45 mmol of H2 was consumed in the initial 8 h, and only 0.07 mmol was consumed in the next 16 h. Since one C–C bond cleavage would consume one H2 molecule (Supplementary Note), the slight H2 consumption after 8 h implies that the Pt/C catalyst exhibits a slower C–C bond cleavage rate7. Compared with Ru9Pt91/C and Pt/C, PE hydrogenolysis proceeded faster over the Ru/C catalyst (Fig. 3c). However, this was accompanied by a significantly high yield of CH4 which exceeded 14.6% at 24 h (Supplementary Fig. 8).

The effect of Ru content in RuPt alloy on the methane selectivity was further investigated. The methane selectivity was determined at a similar H2 consumption of around 1.75 mmol (Supplementary Fig. 9). As shown in Fig. 3d, methane selectivity was proportional to the Ru ratio in the catalyst. It increased from 2.6% for Ru9Pt91 to 18.7% for Ru41Pt59. The result implies that the CH4 generation is related to the Ru sites in the catalyst, and Ru9Pt91/C provides an ideal balance between low methane selectivity and high solid conversion rate.

We subsequently assessed the performance of Ru9Pt91/C at different H2 pressures at similar H2 consumption (Supplementary Fig. 10). As mentioned, previous studies have demonstrated that the methane selectivity over Ru-based catalysts was very sensitive to H2 pressure10. This pressure dependence was confirmed by our Ru/C catalyst. As shown in Fig. 3e, Ru/C exhibited a methane selectivity as high as 29.0% under ambient H2 pressure (Supplementary Fig. 11). The methane selectivity decreased to 21.5% when the hydrogen pressure increased to 1.0 MPa, which can be explained by the accelerated desorption of dehydrogenated fragments due to the increased H* coverage on the catalyst surface (Fig. 1, step 1.5). Instead, Ru9Pt91/C maintained a low methane selectivity (<3.5%) across the entire hydrogen pressure range of investigated, in stark contrast to the behavior of Ru/C. This difference suggests that there might be a different mechanism governing the methane selectivity over the Ru9Pt91/C.

The surface functional groups in carbon support could act as Bronsted acid sites and catalyze cracking. This may interfere with the hydrogenolysis results. To test this possibility, we accessed the catalytic activity of pure carbon support under the same conditions (300 °C, 0.5 MPa H2). It resulted in a 1.3% solid conversion after 24 h. The low solid conversion suggests that the Vulcan XC72 carbon acts inertly during the reaction. We also conducted a hot filtration test of the spent Ru9Pt91/C, which shows negligible metal leaching as determined by ICP-OES. This indicates the NPs keep a good heterogeneity on the carbon support during hydrogenolysis.

Mechanistic study on the C–C bond cleavage

To understand why Ru9Pt91/C can keep low methane selectivity under varying H2 pressures, we first focused on H2 consumption rates over different catalysts. The H2 consumption rate is often used to assess the rate of C–C bond cleavage12. As depicted in Fig. 4a, an increase in Ru content in the catalyst will lead to a significant increase in the H2 consumption rate or a faster C–C bond cleavage rate (Supplementary Fig. 12a). In addition, the near-surface composition determined by XPS and the bulk composition determined by ICP shows a nearly linear relationship, implying there is no obvious surface segregation in the NPs (Supplementary Fig. 12b). We, therefore, normalized the hydrogen consumption rate to each Ru site (defined as Ru-based specific activity), which surprisingly remains little difference for different alloy catalysts (Fig. 4a). This implies that the C–C bond cleavage of PE hydrogenolysis is likely related to the Ru sites in the catalyst.

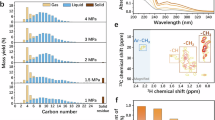

a The H2 consumption rates and Ru-based specific activities of Pt/C, Ru9Pt91/C, Ru25Pt75/C, and Ru41Pt59/C catalysts. Reaction condition: 0.5 MPa H2, 300 °C, 340 mg PE, 20 mg catalyst, 8 h. b In situ DRIFTS spectra of PE hydrogenolysis at 300 °C and ambient pressure catalyzed by Ru9Pt91/C (above) and Ru41Pt59/C (below). The νas(CH2), νs(CH2), ν(C=C), and δ(C–H) represent the asymmetric CH2 stretching, symmetric CH2 stretching, C=C stretching, and CH bending, respectively. c Quasi in situ XPS spectra at Pt 4f of Pt/C, Ru9Pt91/C, Ru25Pt75/C, and Ru41Pt59/C with and without PE after a pretreatment in H2 (10 mL min−1) at 300 °C for one hour. Schematic illustration of the reaction mechanism proposed for Ru9Pt91/C (d) and Ru/C (e), where the grey, black, red, and white balls represent Pt, C, Ru, and H atoms, respectively.

To gain further insights into the role of the Ru sites in PE hydrogenolysis, we employed in situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) to identify the surface species involved in the reaction. The DRIFTS spectrum of free PE exhibits three characteristic peaks (Supplementary Fig. 13), including the asymmetric CH2 stretching at 2920 cm−1, symmetric CH2 stretching at 2850 cm−1, and CH bending at 1462 cm−1. Under reaction conditions (300 °C, ambient H2 pressure), the peak intensities at 2920 cm−1, 2850 cm−1, and 1462 cm−1 decreased with the reaction time in the presence of Ru9Pt91/C or Ru41Pt59/C (Fig. 4b), indicating that PE was gradually converted (the shorter alkanes evaporated and were carried away by the H2 gas flow). Notably, there was another peak appearing at 1630 cm−1 for Ru9Pt91/C. As the stretching vibration of the C=C bond is around 1640 cm−1, the peak at 1630 cm−1 can be ascribed to the dehydrogenated intermediates accumulating on the surface of Ru9Pt9143,44. In comparison, no obvious infrared peak at 1630 cm−1 was observed throughout the reaction when using Ru41Pt59/C as the catalyst (Fig. 4b), indicative of very few dehydrogenated species on the catalyst surface. As Ru41Pt59/C has more Ru sites exposed on the surface, the negligible dehydrogenated species combined with the high H2 consumption rate (Fig. 4a) suggests that the Ru sites are more effective in catalyzing the C–C bond cleavage than the Pt sites (Fig. 1, step 1.4).

To elucidate the role of Pt atoms in hydrogenolysis, we first performed density functional theory (DFT) calculations to compare the H2 dissociation on different surfaces. The models of RuPt alloy were constructed by random substitution based on stoichiometric ratio and the most energetically stable models were selected for subsequent studies (Supplementary Fig. 14a). The H2 molecule dissociates rapidly on these surfaces and the related dissociation energy is shown in Supplementary Fig. 14b. The H2 dissociation energies of Pt (−1.2 eV), Ru9Pt91 (−1.2 eV), Ru25Pt75 (−1.2 eV), Ru41Pt59 (−1.3 eV), and Ru (−1.5 eV) indicate that H2 can easily dissociates on these metal surface. Although the H2 dissociation energy on Ru is slightly more negative, the difference in dissociation ability is not significant considering the high reaction temperature (573 K).

In addition to H2 dissociation, surface Pt is also the active site for PE dehydrogenation (Fig. 1, step 1.2, step 1.3). This is evidenced by in situ DRIFTS spectra of PE hydrogenolysis over Pt/C (Supplementary Fig. 15). As the reaction proceeded, a characteristic C=C stretch at 1630 cm−1 appeared, which indicates the presence of dehydrogenated species on the catalyst surface. The interaction between the Pt sites and PE was further investigated using quasi in situ XPS. Before the measurement, all the samples were pretreated in H2 atmosphere at 300 °C. As depicted in Fig. 4c, the Pt 4f7/2 peaks had a notable shift from 71.4 eV to 70.6 eV when the catalysts were pretreated together with PE. This shift can be explained by PE dehydrogenation and adsorption on the Pt sites. A similar phenomenon was observed in propane dehydrogenation, in which Pt 4f7/2 peak shifted to lower binding energy in reaction atmosphere45. The above results collectively indicate that Pt sites play important roles in H2 dissociation as well as PE dehydrogenation/adsorption. However, considering the poor catalytic performance of Pt/C and the accumulation of dehydrogenation intermediates on its surface (Supplementary Fig. 15), Pt appears to be less efficient in cleaving the C–C bonds compared with Ru.

Putting all the information together, we proposed a mechanism for PE hydrogenolysis using dilute Ru9Pt91 alloy. As the reaction starts, H2 molecules easily dissociate into H* on the catalyst surface, and PE adsorbs onto the catalyst surface and dehydrogenates (Fig. 1, step 1.2, step 1.3). Following that, the C–C bond cleavage is assumed to occur through an α,β-bound RC*–C*R′⧧ transition state, as commonly proposed in gas-phase alkane hydrogenolysis39,40,41,42. This transition state is illustrated in Fig. 4d. Two distinct sites in the dilute Ru9Pt91 alloy are involved in the formation of the α,β-bound transition state: one is a Ru site coordinated with two dehydrogenated carbon atoms, and another is a neighboring Pt site with a similar coordination. Our mechanistic investigations suggest that the C–C bond mostly cleaves at the Ru site, resulting in the formation of two hydrocarbon fragments (Fig. 4d). These two fragments, bonded onto the surface through terminal carbon atoms, may either hydrogenate and desorb to form long-chain alkanes or undergo further dehydrogenation and the 2nd C–C bond cleavage. In the latter pathway, the transition state is more likely to form at the adjacent site, which is more likely to be a Pt site in the dilute RuPt alloy (Fig. 4d), thus resulting in a much slower cleavage rate and potentially causing this pathway to stagnate. Consequently, these fragments are more likely to combine with H* and desorb, avoiding the undesired terminal scission. The picture will be completely different when Ru sites are not diluted (Fig. 4e), in which case the 2nd C–C bond cleavage also occurs at a Ru site and rapidly generates methane.

The mechanism described in Fig. 4d highlights the importance of the diluted Ru sites in Ru9Pt91 alloy in controlling the CH4 selectivity. One question we were interested in is whether the diluted Ru sites on a substrate other than Pt can have the same effect, because the amount of precious metal would be greatly reduced if Pt can be replaced. To this end, we prepared other dilute RuM alloys, including Ru14Ni86/C, Ru6Co94/C, and Ru9Pd91/C. All these dilute alloys showed a very low activity towards PE hydrogenolysis at both 0.5 and 2.0 MPa H2 (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. 16). This comparison suggests that the Pt sites in dilute Ru9Pt91 alloy play an indispensable role in PE hydrogenolysis under low hydrogen pressures.

Although the dilute Ru9Pt91/C can achieve low methane selectivity over a wide range of hydrogen pressure, the reaction temperature is relatively high (300 °C). We therefore attempted to optimize the activity by replacing the intert carbon support with metal oxides. To this end, the colloidal Ru9Pt91 NPs were dispersed onto SiO2 or CeO2 at a metal loading of about 5 wt%. We first compared the catalytic performance of the Ru9Pt91/C, Ru9Pt91/SiO2, and Ru9Pt91/CeO2 at 300 °C under 0.5 Mpa of H2. After two hours of the reaction (Fig. 5a), the solid conversion followed the order of Ru9Pt91/C < Ru9Pt91/SiO2 < Ru9Pt91/CeO2. Meanwhile, these catalysts exhibited similar methane selectivities (<2.3%, Fig. 5a), suggesting that the suppression of terminal scission on the dilute Ru9Pt91 alloy is universal on different supports. Because CeO2 shows significant promoting effect on the hydrogenolysis activity, we then evaluate the Ru9Pt91/CeO2 at a lower reaction temperature of 250 °C. As a result, the Ru9Pt91/CeO2 can fully convert the PE within 3 h at 2.0 MPa or within 8 h at 0.5 MPa with methane selectivities less than 3.7% (Fig. 5b). Characterization on the used catalysts shows that the size distribution of the Ru9Pt91 NPs supported on carbon became broader (Supplementary Fig. 17), while no obvious particle aggregation was observed on CeO2 (Supplementary Fig. 18).

a PE hydrogenolysis catalzed by Ru9Pt91/C, Ru9Pt91/SiO2, and Ru9Pt91/CeO2. Reaction condition: 300 °C, 0.5 MPa H2, 340 mg PE, 20 mg catalyst (Ru9Pt91/C, Ru9Pt91/SiO2, and Ru9Pt91/CeO2; loadings: 4.7 wt% on the basis of Pt), 2 h. b PE hydrogenolysis catalyzed by Ru9Pt91/CeO2 under different H2 pressures. Reaction condition: 250 °C, 340 mg PE, 20 mg catalyst (Ru9Pt91/CeO2 with 4.7 wt%Pt), 3 h for 2.0 MPa (8 h for 0.5 MPa, 24 h for ambient pressure).

Integration of low-pressure hydrogen source into PE hydrogenolysis

Since the dilute Ru9Pt91 alloy breaks the H2-pressure dependence of CH4 production, we consider to run PE hydrogenolysis under low or even ambient H2 pressures for the benefits of simplified reactor design, increased intrinsic safety, improved energy efficiency, and various low-pressure H2 sources (e.g., coke oven gas, propane dehydrogenation, chlor-alkali industry, and water electrolysis). More importantly, single-use PE consumables are widespread and expensive to transport. Distributed plastic recycling/upcycling unit requires a cheap reactor that is compatible with community-scale recycling and can operate under mild conditions.

As a proof-of-concept demonstration, we integrated a water electrolyzer into the upstream of a homemade PE hydrogenolysis reactor. As depicted in Fig. 6a, H2 was produced via water splitting, dried by solid desiccant, and then introduced into an air-tight glass reactor containing PE and the Ru9Pt91/C catalyst. A complete conversion of commercial PE powder (Mw ~ 4000, m.p. 107.1 °C) into fuels and waxes/lubricant base oils was observed after 24 h hydrogenolysis, with a methane yield of 3.2% (Fig. 6b). This approach works well for other PE feedstocks, including low-density PE bags (m.p. 107.1 °C), high-density PE caps (m.p. 134.8 °C), and mixed polyolefins (59% PE, 29% polypropene, and 12% polystyrene, equals to their market share5). This indicates that the dilute Ru9Pt91 alloy has a good tolerance to dyes and additives in the substrates. The product distribution of these different plastic feedstocks exhibited a similar pattern with a yield of C5~C40 no less than 77.8% (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 19). These products can be categorized into different fuels and waxes/lubricant base oils (Fig. 6d, for linear hydrocarbon percentages, see Supplementary Table 4). For example, the products from the hydrogenolysis of HDPE cap under ambient H2 pressure are composed of 10.7% gasoline, 19.4% jet fuel, 38.0% diesel, and 62.5% waxes/lubricant base oils.

a A customized reactor integrating water electrolysis into the upstream of PE hydrogenolysis. b The product distributions of PE powder, low-density PE bag, high-density PE caps, and a mixture of polyolefins. Reaction conditions: ambient H2 pressure, 300 °C, 24 h, 340 mg substrate, 40 mg Ru9Pt91/C. c Detailed carbon distributions of the products for HDPE cap. d Selectivity by carbon range: gasoline, C5~C12; jet fuel, C8~C16; diesel, C9~C22; and waxes/lubricant base oils, C20~C40.

Discussion

In summary, we have demonstrated that dilute RuPt alloy can suppress methane production for PE hydrogenolysis under a wide range of hydrogen pressure. Different from previous approaches that use high H* coverage to accelerate the desorption of dehydrogenated intermediates, this work uses dilute Ru9Pt91 alloy to create disparity in the reaction rate of the 1st and 2nd C–C bond cleavage (Fig. 1). The dilute Ru9Pt91 alloy can convert real-world PE feedstocks into value-added products with a methane selectivity of in the range of 2.0~3.2% under ambient H2 pressure. This new approach enables the coupling of water electrolysis and PE hydrogenolysis, providing a promising solution to decentralized plastic upcycling. The “green H2 + waste plastic → liquid fuels” scheme is worth a more comprehensive life cycle analysis in the future. Future works should also focus on the reactor design to harness the potential of this ambient pressure hydrogenolysis.

Methods

Synthesis of Ru9Pt91

The synthesis of dilute Ru9Pt91 alloy nanoparticles follows a previously reported protocol46. In a typical synthesis, 0.3 mmol of Pt(acac)2 and 0.03 mmol of Ru(acac)3 were mixed with 10 mL of OAm in a three-neck round-bottom flask. The mixture was stirred at 50 °C for 20 min. After complete dissolution, the reaction solution was heated up to 100 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere at a rate of 5 °C min−1. Subsequently, 0.3 mmol of BBA was introduced into the mixture. The reaction was maintained at 100 °C for 30 min, and then was further heated up to 300 °C at the same ramp rate. After reacting at 300 °C for 1 h, the reaction was cooled down to room temperature. The products were collected and purified by centrifuge. Approximately 20 mL of acetone was added into the reaction solution, and the mixture was centrifuged at 6791 × g for 3 min. After discarding the supernatant, the nanoparticles were redispersed in toluene (10 mL) and acetone (20 mL) and subjected to centrifuge again. This process was repeated twice. The final product was redispersed and stored in 10 mL of toluene for further use.

Synthesis of RuPt alloy nanoparticles

The synthesis of RuPt alloy nanoparticles follows the same procedure for Ru9Pt91, but with different feeding amounts of Ru(acac)3. Specifically, 0.3 mmol of Pt(acac)2 was mixed with varying amounts of Ru(acac)3 (0 mmol for Pt/C, 0.1 mmol for Ru25Pt75, and 0.21 mmol for Ru41Pt59) in the synthesis.

Synthesis of Ru14Ni86, Ru6Co94 and Ru9Pd91

The synthesis of Ru14Ni86, Ru6Co94, and Ru9Pd91 nanoparticles follows the same procedure for Ru9Pt91, but with the replacement of Pt(acac)2 into Ni(acac)2, Co(acac)2, and Pd(acac)2.

Catalyst loading on support

To prepare carbon-supported catalysts, Vulcan XC72 carbon was first dispersed in toluene under sonication for 10 min. The stock solution of nanoparticles in toluene was added into the carbon dispersion dropwise under sonication, and the mixture was further sonicated for 1 h. The metal loadings were determined to be 22.0 wt% Pt for Pt/C, 20.0 wt% Pt for Ru9Pt91/C, 16.5 wt% Pt for Ru25Pt75/C, 13.0 wt% Pt for Ru41Pt59/C, 3.6 wt% Ni for Ru14Ni86/C, 5.9 wt% Co for Ru6Co94/C, and 10.6 wt% Pd for Ru9Pd91/C. The total molar amounts of precious metals on the support were kept the same for different catalysts. The resultant suspension was then transferred to a centrifuge tube and centrifuged at 6791 × g for 3 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the solid residue was washed twice with toluene. The solid powder was subsequently dried at 65 °C in an oven overnight and calcined in air at 200 °C in a muffle furnace for 3 h to eliminate the remaining ligands.

To prepare SiO2 and CeO2-supported catalysts, the procedure is similar to the catalyst loading on the carbon support. The metal loading was determined to be 4.7 wt% on the basis of Pt.

Synthesis of Ru/C catalyst

The synthesis of Ru/C is based on a previously reported procedure with slight modifications47. Typically, 0.06 mmol of RuCl3·xH2O, 28 mg of PVP, and 532 mg of Vulcant XC72 were mixed with 10 mL of ethylene glycol in a two-neck round-bottom flask. The mixture was heated up to 200 °C in an oil bath and maintained at this temperature for 3 h. After that, the reaction was cooled down to room temperature. The reaction mixture was transferred into a centrifuge tube and centrifuged at 10612 × g for 3 min. The transparent supernatant was discarded. The solid at the bottom of the centrifuge tube was then washed three times with water and ethanol. The solid powder was subsequently dried at 80 °C in an oven overnight and calcined in air at 200 °C in a muffle furnace to remove remaining organic ligands.

Catalytic hydrogenolysis of PE

The PE hydrogenolysis was performed in a 25 mL batch autoclave. PE (340 mg) and catalyst (20 mg) were loaded into a glass-lined autoclave and stirred with a glass magnetic stirrer. The glass liner was customized with a glass thermowell of 4 mm diameter and welded to the bottom of the liner. A K-type thermocouple with a diameter of 1.5 mm was bent and soaked to the bottom of the thermowell to measure the temperature of reactants. The autoclave was sealed, vacuumed, purged with argon for three times, and then purged with hydrogen for another three times. After this, the autoclave was pressurized to the specified pressure. All the pressures reported in this work are gauge pressure at room temperature. After a designated time, the reactor was allowed to cool down to room temperature. The gas was released, collected using a gas bag, and analyzed by gas chromatography (GC). The products were dissolved in CHCl3 and analyzed by GC. The polymeric residue was calculated by the mass difference of the glass line before and after the reaction.

Catalytic hydrogenolysis of PE under ambient pressure

The PE hydrogenolysis under ambient pressure was performed in a homemade reactor (Fig. 6a). PE (340 mg), catalyst (40 mg), and a glass magnetic stirrer were loaded into an air-tight glass tube. The reactor was vacuumed and purged with hydrogen. The reactor was then heated up to 300 °C and maintained at this temperature for 24 h. The H2 was supplied from a water electrolyzer and introduced into the reactor intermittently every 15 min by controlling the current (purge for 1 min each time at a flow rate of about 2 mL min−1). All gas was collected in a gas bag and further quantified in GC. The non-volatile products were dissolved in CHCl3 and analyzed by GC.

Product analysis

An Agilent Technologies 8890 GC system equipped with a temperature conductivity detector (TCD) and flame ionization detector (FID) was used to analyze the gas and liquid products.

For gas products, a certain volume of nitrogen was purged into the gas bag as a standard. The GC is configured with two separate channels. One is equipped with two Hayesep Q (G3591-81020) columns and a MolSieve 5 A column (G3591-81022) to separate the hydrogen, nitrogen, methane, ethane, propane, and butane, which are quantified by a TCD detector. The other channel is equipped with a capillary column DB-1 (123-1032,0.32 mm, 30 m, 0.25 µm) to separate pentane, hexane, and heptane, which are quantified by an FID detector. The mass of the gas product is calculated using the predictive Redlich-Kwong-Soave (PSRK) equation.

All the liquid products were dissolved and collected in 50 mL chloroform. Mesitylene was added to the liquid sample as a standard. The sample was separated in the channel equipped with a capillary column DB−1 (123-1032,0.32 mm, 30 m, 0.25 µm) to separate the product from C7H16 to C40H88 which was quantified by a FID detector. The species were calibrated by the retention time of C7~C40 saturated alkanes standard (Supelco, Lot 49452-U) with 1000 μg mL−1. At the same time, the response factor of alkanes of each carbon number in FID was also calibrated. The positions of isomers of each carbon number were established concerning the linear chain.

Hot infiltration test

The hot filtration test was conducted by dispersing 20 mg of the used catalyst into 2 mL of n-hexadecane (b.p. 286.9 °C) and the mixture was heated at 100 °C for one hour. The hot mixture was poured through a filter paper which was pre-heated at 100 °C in an oven. The filtrate was collected and transferred into a 20 mL glass vial. After the evaporation of the solvent, nitric acid and hydrochloric acid were added into the vial to digest any metals in the residual under sonication for one hour. The digestion solution was diluted and analyzed using ICP-OES to quantify the metal content.

Material characterizations

TEM images were taken on a Hitachi H-7650B microscope operated at 80 kV. The high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscope (HAADF-STEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analyses were performed on aberration-corrected TEM using a FEI-Titan Cubed Themis G2 300 and a FEI-Themis Z microscope operated at 300 kV. Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were collected using Rigaku Mini Flex 600 with Cu-Kα radiation. Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) was measured using Thermo Scientific iCAP 6300.

X-ray adsorption spectroscopy

The XAS data were collected at the BL11B and BL14W1 stations at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF), and 1W1B, 4B9A station at Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility (BSRF). The data at Pt L3-edge was calibrated to a Pt foil, while the Ru K-edge was calibrated to a Ru foil. All the data analysis was carried out using Artemis and Athena in the Demeter software suite by FEFF software4 using bulk references. For EXAFS fitting, the amplitude reduction factor (S02) was determined by fitting the first shell scattering of the reference metal foil. The obtained S02 was then fixed in the samples.

Quasi in situ X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy

Quasi in situ X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) experiments were performed on an Axis Supra (Kratos Analytical Ltd., UK) system equipped with an Al Kα X-ray source (1486.6 eV) operating at 200 W for survey scans and 300 W for core level spectra. The binding energy was calibrated by the C 1 s line at 284.8 eV. The XPS is equipped with a reaction chamber connected through a UHV-chamber.

The catalyst sample was tablet-pressed and placed in a glass holder. The holder was vacuumed and transferred into the reaction chamber and pretreated at 300 °C for 1 h under a H2 flow at 10 mL min−1. After cooling down to room temperature under H2 flow, the reaction chamber was vacuumed and the glass holder was transferred into the XPS chamber for characterization.

The catalyst mixed with PE was treated in the following way. Initially, 0.1 g of PE was dissolved in 1 mL of toluene at 100 °C. The solution was immediately mixed with 20 mg of the catalysts. The mixture was stirred until dry, and was further dried out in an oven at 65 °C overnight. The solid was then tablet-pressed and placed in a glass holder for further treatment and characterization.

In situ diffuse reflections infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS)

In situ, DRIFTS measurements were performed via a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (Thermo Nicolet iS50) equipped with a diffuse reflection accessory (Harrick Inc.). To prepare the sample, 20 mg of the catalysts was first mixed with KBr (200 mg). Then, 10 mg of PE was dissolved in 1 mL of toluene at 100 °C. The PE solution (0.1 mL) was added to the catalyst/KBr mixture and stirred until dry. The mixture was further dried out in an oven at 65 °C overnight. The sample was loaded in a high-temperature in situ DRIFTS reactor (Harric Inc.). The sample was pretreated at 150 °C under a H2 flow (5 mL min−1) for 30 min and then heated up to 300 °C to start the measurement.

Data availability

All data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

MacLeod, M., Arp, H. P. H., Tekman, M. B. & Jahnke, A. The global threat from plastic pollution. Science 373, 61–65 (2021).

Geyer, R., Jambeck, J. R. & Law, K. L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 3, e1700782 (2017).

Jambeck, J. R. et al. Marine pollution. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science 347, 768–771 (2015).

Garcia, J. M. & Robertson, M. L. The future of plastics recycling. Science 358, 870–872 (2017).

Ellis, L. D. et al. Chemical and biological catalysis for plastics recycling and upcycling. Nat. Catal. 4, 539–556 (2021).

Milbrandt, A., Coney, K., Badgett, A. & Beckham, G. T. Quantification and evaluation of plastic waste in the United States. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 183, 106363 (2022).

Celik, G. et al. Upcycling single-use polyethylene into high-quality liquid products. ACS Cent. Sci. 5, 1795–1803 (2019).

Rorrer, J. E., Beckham, G. T. & Román-Leshkov, Y. Conversion of polyolefin waste to liquid alkanes with Ru-based catalysts under mild conditions. JACS Au. 1, 8–12 (2021).

Wang, C. et al. Polyethylene hydrogenolysis at mild conditions over ruthenium on tungstated zirconia. JACS Au. 1, 1422–1434 (2021).

Chen, L. et al. Disordered, sub-nanometer Ru structures on CeO2are highly efficient and selective catalysts in polymer upcycling by hydrogenolysis. ACS Catal. 12, 4618–4627 (2022).

Chu, M. et al. Site-selective polyolefin hydrogenolysis on atomic Ru for methanation suppression and liquid fuel production. Research 6, 0023 (2023).

Chen, S. et al. Ultrasmall amorphous zirconia nanoparticles catalyse polyolefin hydrogenolysis. Nat. Catal. 6, 161–173 (2023).

Wu, X. et al. Size-controlled nanoparticles embedded in a mesoporous architecture leading to efficient and selective hydrogenolysis of polyolefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 5323–5334 (2022).

Nakaji, Y. et al. Low-temperature catalytic upgrading of waste polyolefinic plastics into liquid fuels and waxes. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. Energy 285, 119805 (2021).

Cappello, V. et al. Conversion of plastic waste into high-value lubricants: techno-economic analysis and life cycle assessment. Green. Chem. 24, 6306–6318 (2022).

Wang, M. et al. Complete hydrogenolysis of mixed plastic wastes. Nat. Chem. Eng. 15, 8536 (2024).

Sun, C. et al. Pt enhanced C–H bond activation for efficient and low-methane-selectivity hydrogenolysis of polyethylene over alloyed RuPt/ZrO2. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. Energy 353, 124046 (2024).

Hu, P. et al. Stable interfacial ruthenium species for highly efficient polyolefin upcycling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 7076–7087 (2024).

Liu, S., Kots, P. A., Vance, B. C., Danielson, A. & Vlachos, D. G. Plastic waste to fuels by hydrocracking at mild conditions. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf8283 (2021).

Lee, J. et al. Highly active and stable catalyst with exsolved PtRu alloy nanoparticles for hydrogen production via commercial diesel reforming. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. Energy 316, 121645 (2022).

Rorrer, J. E. et al. Role of bifunctional Ru/acid catalysts in the selective hydrocracking of polyethylene and polypropylene waste to liquid hydrocarbons. ACS Catal. 12, 13969–13979 (2022).

Zhang, Z. et al. Recovering waste plastics using shape-selective nano-scale reactors as catalysts. Nat. Sustain. 2, 39–42 (2019).

Duan, J. et al. Coking-resistant polyethylene upcycling modulated by zeolite micropore diffusion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 14269–14277 (2022).

Jie, X. et al. Microwave-initiated catalytic deconstruction of plastic waste into hydrogen and high-value carbons. Nat. Catal. 3, 902–912 (2020).

Dai, L. et al. Catalytic fast pyrolysis of low density polyethylene into naphtha with high selectivity by dual-catalyst tandem catalysis. Sci. Total Environ. 771, 144995 (2021).

Supriyanto, Ylitervo, P. & Richards, T. Gaseous products from primary reactions of fast plastic pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 158, 105248 (2021).

Dong, Q. et al. Depolymerization of plastics by means of electrified spatiotemporal heating. Nature 616, 488–494 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. Mixed plastics wastes upcycling with high-stability single-atom Ru catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 22836–22844 (2023).

Sullivan, K. P. et al. Mixed plastics waste valorization through tandem chemical oxidation and biological funneling. Science 378, 207–211 (2022).

Zhao, B. et al. Catalytic conversion of mixed polyolefins under mild atmospheric pressure. Innovation 5, 100586 (2024).

Zhang, F. et al. Polyethylene upcycling to long-chain alkylaromatics by tandem hydrogenolysis/aromatization. Science 370, 437–441 (2020).

Wang, N. M. et al. Chemical recycling of polyethylene by tandem catalytic conversion to propylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 18526–18531 (2022).

Sun, J. et al. Bifunctional tandem catalytic upcycling of polyethylene to surfactant-range alkylaromatics. Chem 9, 2318–2336 (2023).

Conk, R. J. et al. Catalytic deconstruction of waste polyethylene with ethylene to form propylene. Science 377, 1561–1566 (2022).

Jia, X., Qin, C., Friedberger, T., Guan, Z. & Huang, Z. Efficient and selective degradation of polyethylenes into liquid fuels and waxes under mild conditions. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501591 (2016).

Tennakoon, A. et al. Catalytic upcycling of high-density polyethylene via a processive mechanism. Nat. Cat. 3, 893–901 (2020).

Wang, C. et al. A general strategy and a consolidated mechanism for low-methane hydrogenolysis of polyethylene over ruthenium. Appl Catal. B-Environ. Energy 319, 121899 (2022).

Lee, K., Jing, Y., Wang, Y. & Yan, N. A unified view on catalytic conversion of biomass and waste plastics. Nat. Rev. Chem. 6, 635–652 (2022).

Flaherty, D. W. & Iglesia, E. Transition-state enthalpy and entropy effects on reactivity and selectivity in hydrogenolysis of n -alkanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 18586–18599 (2013).

Flaherty, D. W., Hibbitts, D. D. & Iglesia, E. Metal-catalyzed C–C bond cleavage in alkanes: Effects of methyl substitution on transition-state structures and stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 9664–9676 (2014).

Flaherty, D. W., Hibbitts, D. D., Gürbüz, E. I. & Iglesia, E. Theoretical and kinetic assessment of the mechanism of ethane hydrogenolysis on metal surfaces saturated with chemisorbed hydrogen. J. Catal. 311, 350–356 (2014).

Hibbitts, D. D., Flaherty, D. W. & Iglesia, E. Effects of chain length on the mechanism and rates of metal-catalyzed hydrogenolysis of n-Alkanes. J. Phys. Chem. C. 120, 8125–8138 (2016).

Shi, L. S., Wang, L. Y. & Wang, Y. N. The investigation of argon plasma surface modification to polyethylene: Quantitative ATR-FTIR spectroscopic analysis. Eur. Polym. J. 42, 1625–1633 (2006).

Zhou, Q. et al. Mechanistic understanding of efficient polyethylene hydrocracking over two-dimensional platinum-anchored tungsten trioxide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202305644 (2023).

Chen, S. et al. Propane dehydrogenation on single-site [PtZn4] intermetallic catalysts. Chem 7, 387–405 (2021).

Li, J. et al. Anisotropic strain tuning of L10ternary nanoparticles for oxygen reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 19209–19216 (2020).

Kusada, K. et al. Discovery of face-centered-cubic ruthenium nanoparticles: Facile size-controlled synthesis using the chemical reduction method. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 5493–5496 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Beijing Natural Science Foundation (Z240029) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22375113 and 22075162). We acknowledge the BL11B, BL14W1 stations in Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) and 1W1B, 4B9A station in Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility (BSRF) for the collection of XAFS data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.N. conceptualized and guided this work. Z.N. and Q.H. designed the experiments. Q.H. performed the catalyst preparation and hydrogenolysis. Y.C. and S.Q. performed the DFT calculations. M.J. quantified the potential for climate change mitigation. T.G. performed XAS measurement and data analysis. Z.N., Q.H., and S.Q. wrote the paper. Y.W., J.Z., M.S., H.H., J.M., and J.Z. revised the manuscript. All the authors participated in the data analysis and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, Q., Qian, S., Wang, Y. et al. Polyethylene hydrogenolysis by dilute RuPt alloy to achieve H2-pressure-independent low methane selectivity. Nat Commun 15, 10573 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54786-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54786-x

This article is cited by

-

Current perspective on heterogeneous thermal catalytic approaches for closed-loop polyolefin plastic recycling

Discover Chemistry (2026)

-

Sustainable polyolefin upcycling using liquid organic hydrogen carrier based hydrogen delivery and hydrocracking

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Polyethylene hydrogenolysis to liquid products over bimetallic catalysts with favorable environmental footprint and economics

Nature Communications (2025)

-

CO-promoted polyethylene hydrogenolysis with renewable formic acid as hydrogen donor

Nature Communications (2025)