Abstract

Controlling the suitable light, temperature, and water is essential for plant photosynthesis. While greenhouses/warm-houses are effective in cold or dry climates by creating warm, humid environments, a cool-house that provides a cool local environment with minimal energy and water consumption is highly desirable but has yet to be realized in hot, water-scarce regions. Here, using a synergistic genetic algorithm and machine learning, we propose and demonstrate a coolhouse film that regulates temperature and water for photosynthesis without requiring additional energy or water. This scalable film, selected from hundreds of potential designs, selectively and precisely transmits sunlight needed for photosynthesis while reflecting excess heat, thereby reducing thermal load and evapotranspiration. Its optical properties also exhibit weak angle dependence. In demonstrations in subtropical and arid regions, the film reduces temperatures by 5–17 °C and cuts water loss by half, resulting in more than doubled biomass yield and survival rates. It also improves crop resistance to heat and drought in greenhouse cultivation. The integration of machine learning and photonics provides a powerful toolkit for designing photonic structures and devices aimed at sustainability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Creating a local environment that is more conducive to plant photosynthesis, has been of central importance for human beings since the beginning of civilization, as photosynthesis is closely linked to crucial aspects of sustainability from food to environment. It is becoming more critical with the increasingly worsening global warming and water crisis (with over 70% attributed to anthropogenic activities in agriculture and four billion people affected)1,2,3,4. The key to enable photosynthesis is to offer a hospitable local environment, by controlling the light, temperature, and water use5,6. In cold and/or dry climates/regions, a greenhouse or sometimes referred as a hothouse represents a classical innovation that enables plant growth by creating a local warm-wet environment7,8. For hot and/or water-short climates/regions (e.g., subtropical/tropical and semiarid/arid regions), which account for over half of the earth’s surface, a feasible strategy to create a coolhouse without active energy/water consumption is highly desirable, but so far not yet realized.

Although many advanced active (e.g., using air conditioning and fans) or passive (e.g., using evaporative cooling and shading) strategies have been intensively explored, the challenges related to massive energy/water consumption and high initial/operating cost limit their widespread applications9,10,11. The recent burgeoning developments of radiative cooling12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22 provide an exciting pathway to realize passive cooling without consumption of water and electricity. However, it requires reflection of almost all the incident sunlight to maximize the cooling performance, not compatible with specific light requirements for photosynthesis (detailed below).

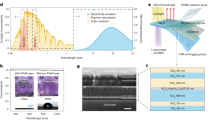

To build a coolhouse for managing light, temperature, and water for plant photosynthesis in hot and water stressed area, it is necessary to first analyze the energy and water balances between plants and surroundings. As schematically shown in Fig. 1a (left panel), the energy flows mainly including evapotranspiration, convection, radiation, conduction, and soil heat storage are all in response to the variations of incoming sunlight23,24. As only a small fraction of the incident solar spectrum (Fig. 1b, c) is utilized for photosynthesis, there is an opportunity to reduce excess sunlight input without affecting photosynthesis. Such reduced sunlight input can not only lead to remarkably reduced temperature of plants, but also minimize water loss due to evapotranspiration, the main water loss pathway in terrestrial ecosystem water balance24,25,26 (Fig. 1a, right panel). Specifically, a photonic design of coolhouse film should enable a selective transmission of sunlight (400–500 nm and 600–700 nm27,28, accounting for 28% of sunlight) for plant photosynthesis, and complete reflection of the rest of the broad solar spectrum (280–400 nm, 500–600 nm, and 700–2500 nm; taking up 72% of sunlight) (Fig. 1d). Notably, the aforementioned design is only a general demonstration to approach the best cooling performance. It calls for a lot more collaborative effort in the future to carefully design the optical spectrum to fit the specific light requirements of different plants and systematic evaluation of various aspects of plant growth. For example, if a specific amount of 500–600 nm or other wavelength of sunlight is necessary for some kinds of plants, it requires further detailed evaluations.

a Simplified energy (left) and water (right) balances between plans and surroundings, respectively. Only major flows are plotted. Sunlight is the dominator of heat input and consequential surface temperature. Water evapotranspiration is the major heat loss that compensates for the sunlight heat input, and also is the primary reason for water loss in the water balance23,24,25,26. The difference between a greenhouse and an open surface are shown by the dashed lines. b The power distribution of sunlight, including ultraviolet (UV, ~4%), visible (Vis, ~43%), and near-infrared (NIR, 53%) light50. The purple, green, orange, and red lines show the positions of wavelengths of 400, 500, 600, and 700 nm, respectively. c Absorptivity spectra of plant pigments that function photosynthesis. Only specific Vis bands of sunlight, mainly at 400–500 and 600–700 nm, are necessary for photosynthesis27,28. The remaining sunlight is largely (>50%) absorbed by plants/ground51,52. The mismatched sunlight supply-demand results in undesired overheating and drastic water loss of plants, thus hindering the normal function of photosynthesis. d The spectral filtration of sunlight enables the best cooling performance, which satisfies the major demand for photosynthesis (transmission) and simultaneously rejects the other wavebands within sunlight (reflection). More than two-thirds of ineffective sunlight is blocked (inset), minimizing the system temperature and water loss. Notably, this spectrum design only suits some plants and more specific waveband requirements need further customization. e The design process of the coolhouse film via synergetic genetic and deep learning algorithms. The forward prediction model in a conventional tandem neural network is replaced as an analytical transfer matrix method (TMM) in our case. f Photonic designs of the coolhouse film generated from the synergetic genetic and deep learning algorithms. The photonic designs with low spectral error (close to the targeted spectrum), small angle dependence (given the motion of the sun), and low difficulty of fabrication are desired. The design highlighted by the red circle thus is chosen as a typical example to demonstrate the coolhouse film. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

These stringent requirements impose an immediate challenge in designing such a coolhouse film. Existing approaches that support broadband reflection using optically thick metal13 or randomly stacked Mie scattering structures16,17,18,21 intrinsically block the transmission channels. Alternatively, using extraordinary optical transmission29,30 or all-dielectric bandpass filter31,32 can produce transmission bands at desired wavelength but will introduce additional undesired transmission bands in other wavelength ranges. In addition, it either requires lithography, or a large number of carefully designed chirped layers and complicated processing (e.g., assembly of dozens of layers of films)31,32, adding complexity and cost for practical applications.

With the exciting advancement of computational science, recently both genetic algorithm and machine learning33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43 have been exploited to accelerate the discovery of advanced photonic designs to meet the tough spectrum requirements of photosynthesis. The genetic algorithm is a non-gradient-based optimization technique that can progressively optimize both the thickness and material choice of each layer. It can be applied immediately to a target spectrum without any prior information, and avoid subpar local minima due to the random reproduction and mutation process. However, the iteration is time-consuming and may not ultimately reach the precise local minimum. Machine learning, on the other hand, is based on stochastic gradient descent and performs better when input parameters are continuous, such as layer thickness. Once trained, the models can be used to systematically explore a design parameter space and to approximate a global optimum within the design parameter phase space. However, it requires an input dataset for training purposes and is suboptimal for discrete data such as material sequence.

Here, we propose a framework that combines genetic algorithm and machine learning (tandem neural network) in a synergetic manner, which preserves the respective advantages while avoiding each of their drawbacks, to accelerate the discovery of the photonic designs with not only the desired spectral feature, but also easy fabrication and weak angle dependence (given the motion of the sun). The detailed inverse design process is shown in Fig. 1e. First, the genetic algorithm is used to create multilayer designs that have been pre-optimized with a variety of material selections and sequences. These initial designs, which include the choice of material and the thickness of each layer, serve as the input datasets for the training of neural networks, which would then be used for additional optimization of the design (Supplementary Note 1, and Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2 for more details). Consequently, the hybrid model offers hundreds of possible designs, and the best design is chosen by considering the spectral error compared with the target spectrum, angle dependence, and difficulty of fabrication (by considering layer number, thickness, and materials; see Methods for more details). Therefore, the one highlighted by the red circle in Fig. 1f is chosen as a representative example to realize the aforementioned photonic design of coolhouse film.

As a result, we show this photonic design of coolhouse film via an elaborately designed six-layer film (TiO2/MgF2/TiO2/Ag/MgF2/TiO2), which perfectly fits the aforementioned spectrum feature (with two specified transmission peaks coupled with multi-broadband high reflection) and has weak angle dependence between −50° to 50°. It enables effective passive cooling for plants without affecting photosynthesis and consuming extra energy/water. Both our indoor and outdoor experiments in the subtropical region and desert area consistently verify that our coolhouse film lowers the air temperature around the ground by 5–17 °C and reduces the soil water evaporation by more than half, compared with polyethylene (PE) film (one of the typical greenhouses films) and an open environment without any covering. As shown in more details below, plant cultivation results both outdoors and in a greenhouse, where only the plants under our coolhouse film grow healthily and have the highest photosynthetic rate and fruit together with biomass yields, agree well with the expectations from temperature and water evaporation tests.

Results

Fabrication and characterizations of the coolhouse film

The corresponding material structure of the red star in Fig. 1f is schematically shown in Fig. 2a. Electronic beam evaporation was used to experimentally realize such a design. The combination of the TiO2/MgF2/TiO2/Ag/MgF2/TiO2 layers results in a macroscopically planar and integrated film as shown in the SEM image (Fig. 2b), with the thickness of each layer corresponding to the designed values in Fig. 2a. The as-prepared coolhouse film shows a distinct sunlight filtration effect (the physical mechanism is detailed in Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Figs. 3–5). It reflects sunlight with yellow-green color and transmits sunlight with a complementary purple color (Fig. 2c), indicating its high reflection in 500–600 nm and high transmission in 400–500 nm (blue band) and 600–700 nm (red band). Such an effect is further confirmed by the experimentally measured transmissivity spectrum. As shown in Fig. 2d, two sharp transmission peaks permit the sunlight transmission in the spectral ranges of 400–500 nm and 600–700 nm to meet the optical requirements of photosynthesis, while the other bands of sunlight are reflected (Fig. 2e), corresponding to the goal outlined in Fig. 1d. Importantly, such an optical feature maintains very stable during 16 months of continuous outdoor exposure (Supplementary Fig. 6). It is also noticed that there are still some light transmissions at the 500–600 nm and after 700 nm, which may be conducive to the plant growth with specific requirements for these wavebands.

a, b A schematic and a cross-section SEM image of the experimentally fabricated coolhouse film, respectively. Scale bar of (b) 200 nm. c Outdoor sunlight filtration. As expected, yellow-green sunlight (500–600 nm) is reflected, and 400–500 nm and 600–700 nm sunlight is selectively transmitted (showing a purple color). d The experimental spectrum matches well with the theoretically designed one. e Reflectivity spectra as a function of incident angle of the coolhouse film. The incident light is unpolarized. Weak angle dependence is observed, which is highly desirable in practical applications. f Effects of sunlight filtration. Only 268 W m−2 of sunlight passes the coolhouse film, which is expected to efficiently lower the thermal load and water loss of plants. g The photograph shows a flexible and large-scale (1.6 m by 0.3 m) coolhouse film. Scale bar, 20 cm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We also calculated and monitored the angle-dependent reflectivity spectrum of the coolhouse film. It is found that the positions of the two reflective valleys (i.e., the transmissivity peaks) are nearly unchanged between −50° to 50° of the angles of incidence (Supplementary Fig. 7 and Fig. 2e), suggesting that the spectrum of coolhouse film has a weak angle-dependence, which is important for practical applications since the incident angle of sunlight varies significantly during the course of the day.

Based on the optical spectrum of the as-prepared coolhouse film, we evaluate the energy flows with the coolhouse film under the global standard sunlight spectrum (Air Mass 1.5 G) with a power density of 1000 W m−2. The results show that around 268 W m−2 of sunlight transmits the coolhouse film, where the effective component for photosynthesis is 185 W m−2. At the same time, 659 W m−2 of sunlight is reflected (Fig. 2f). Our following results of plant cultivation demonstrate that such a substantial reduction in thermal load is beneficial for preventing plants from overheating and the resulting excessive water loss/consumption. Based on the above six-layer thin film design, we also explored meter-scale production of the coolhouse film on flexible polyethylene terephthalate (PET) substrate via a large-scale commercial facility. In Fig. 2g, we successfully demonstrate the feasibility toward the scaling-up of the coolhouse film. A preliminary estimation shows that its unit production cost is estimated to be 1 $ m−2 (Supplementary Note 3).

Indoor experiments for verification

Subsequently, we examine the passive cooling effects enabled by our coolhouse film. The UV-NIR filter (the UV and NIR components are reflected/absorbed, Supplementary Fig. 8) and a typical greenhouse film of PE are used as the controls44. The transmissivity spectra of the three samples across the solar spectrum are plotted in Fig. 3a. Based on the optical spectra, we analyze and summarize the transmitted energy flows that are at 400–500 nm coupled with 600–700 nm (effective for photosynthesis) and at other wavelength (beyond the two wavebands of 400–500 nm and 600–700 nm), when plants are covered by the above three samples. The diagram of Fig. 3b clearly shows that the coolhouse film, UV-NIR filter, and PE film permit a similar amount of transmission for the sunlight spectral components that are at 400–500 nm and 600–700 nm for photosynthesis, 185.0, 191.3, and 260.3 W m−2, respectively. However, there are huge differences in the transmission of sunlight spectral components that are at the other wavelength, namely, 82.9, 245.6, and 656.0 W m−2, respectively. We use the ratio of transmitted sunlight at other wavelength to the one at 400–500 nm together with 600–700 nm as a figure of merit to evaluate the sunlight filtration effects of these samples (coolhouse film, UV-NIR filter, and PE film). The ratio for the coolhouse film is calculated to be mere 0.45, in comparison to 1.28 for the UV-NIR filter and 2.52 for PE film, respectively. This means that the transmitted sunlight at other wavelength for the UV-NIR filter or PE film largely exceeds the supposed effective component at 400–500 nm along with 600–700 nm for photosynthesis, which will inevitably aggravate overheating and water loss of plants in hot summer, not desirable for photosynthesis.

a Transmissivity spectra of the control samples, including a PE film, a UV-NIR filter, and our coolhouse film. b Energy analysis based on the optical spectra of the control samples. Our coolhouse film enables a similar transmission of sunlight at 400–500 nm coupled with 600–700 nm for photosynthesis while a much lower amount of energy input at other wavelength, compared with the other two control samples. c Schematics show the experimental setups used for comparing the cooling effects (left, closed system) and soil water evaporation (right, open system) of control samples. d, e Air and soil temperatures of the control samples under different sunlight intensities, respectively. The anomaly of PE film in the case of 1 kW m−2 may come from the light scattering effect of condensed water drops. f Soil water evaporation under varying sunlight intensities (without wind) while covered by the control samples. The coolhouse film effectively lowers the temperature and soil water evaporation. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To further verify our coolhouse film’s capabilities of passive cooling and water retention for plants, we measured air temperature around the ground and soil temperature (1.5 cm beneath the surface) and water evaporation rate from the soil via the experimental setups shown in Fig. 3c (the corresponding photograph is shown in Supplementary Figs. 9, 10). The air and soil temperatures covered by different samples under varied sunlight intensity from 0.25 to 1 kW m−2 with an interval of 0.25 kW m−2 are presented in Fig. 3d, e, respectively (see Method for more experimental details). It can be observed that the coolhouse film consistently enables the lowest temperature in comparison with the cases when the UV-NIR filter and PE film are used. For example, under 1 kW m−2 of sunlight illumination, with the use of the coolhouse film, the air and soil temperatures reduce by 10–15 °C. This proves that our coolhouse film provides an effective passive cooling solution. It is also observed that the air temperature under the coolhouse film is 2.3–4.5 °C higher than the control group (without covering). However, the soil temperature is close to that of the control. This can be mainly attributed to the fact that the absorbed solar heat (provided by a point light source in this test, Supplementary Fig. 9) by air in the control test is quickly dissipated to the colder surroundings via natural convention. The test of the evaporation rate of soil (under a windless condition, Supplementary Fig. 10) demonstrates that the coolhouse film notably slows the water loss rate, compared with the UV-NIR filter and PE film due to the reduced temperature (Fig. 3f). It is found that the water loss of the control group in an open environment without any covering materials (0.89 kg m−2 h−1) is more than twice as much as that with our coolhouse film (0.32 kg m−2 h−1). Therefore, from comprehensive evaluations, our coolhouse film has the best performances in passive cooling and water saving.

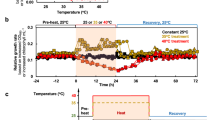

Outdoor field tests

Following the indoor experiments, as mapped out in Fig. 4a, we next carried out outdoor field tests in two places that have pressing requirements for passive cooling and water-saving for plant photosynthesis: one in Nanjing, Jiangsu province (subtropical area, a famous oven-city in China) and one in Ulan Buh Desert, Inner Mongolia (one of the eight largest deserts in China)11,44,45. The temperature profiles in Fig. 4b (tested in Nanjing) show that the air temperature below the coolhouse film is about 30 °C, which is ~5 °C and ~10 °C lower than that below the UV-NIR filter and PE film, respectively, again proving that the coolhouse film has much better passive cooling performance (sunlight power ~600 W m−2 is recorded and shown in Supplementary Fig. 11). We also observed that the air temperature with the coolhouse film is ~5 °C higher than that in the control. This is mainly because the test was performed in the late autumn (November of Nanjing). It is expected that if the comparative experiments were done on hot summer days, our coolhouse film is capable of cooling plants to a temperature that is lower than the control as our demonstrations in the desert experiment below.

a The map and photographs show the two field tests (orange rectangles): Nanjing (hot in summer) and Ulan Buh desert (hot and dry in summer). The foam with Al foil of the experimental setup (silvery part) is used to minimize parasitic heat flows with the surroundings. Scale bar, 15 cm (left) and 10 cm (right). b–d Field test in Nanjing. b Air temperature comparisons. Our coolhouse film is capable of effectively reducing the temperature of plants to the hospitable range for photosynthesis of below 35 °C (the dashed line). c Top view of the Arabidopsis at day 15 under different control samples. The Arabidopsis under our coolhouse film grows healthily. In contrast, overheating and too fast water loss kill most Arabidopsis of the other three control groups. Scale bar, 5 cm. d Aboveground fresh weight of the Arabidopsis under different control samples. The data are presented as the mean ± s.d. (n = 31); the error bars indicate measurement variations. Our coolhouse film enables the highest biomass yield. e–g Field test in Ulan Buh desert. e Air temperature comparisons. The coolhouse film enables the most resultful cooling (lowest air temperature). f Top view of the Gaillardia aristate at day 3 under different control samples. A similar trend is observed as that of the Arabidopsis experiments in Nanjing. Scale bar, 5 cm. g Comparison in the ratio of water loss with natural wind. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Due to the effective passive cooling enabled by the coolhouse film, the Arabidopsis (a classical plant used in botany studies with an upper range of tolerable temperature of ~35 °C) grows healthily, as shown by the photographs in Fig. 4c (see Supplementary Fig. 12 for more test details). In contrast, the Arabidopsis beneath the UV-NIR filter and PE film are killed by overheating. The Arabidopsis without any covering material (control group) is also withered because of too fast water loss in the open system. In Fig. 4d, we record the fresh weight of the Arabidopsis in the four control experiments. It clearly shows that the plants with the coolhouse film enable the highest biomass yield thanks to effective passive cooling and water saving.

We next evaluate the passive cooling and water-saving effects of the coolhouse film in a hot-dry desert (in August, summer days). As shown in Fig. 4e, the air temperature under the coolhouse film is the lowest in comparison to the other three control groups (sunlight power ~750 W m−2 is recorded and shown in Supplementary Fig. 13). It is estimated that at noon (12:00–14:00) the air temperature difference between the coolhouse film and the control, the UV-NIR filter, and the PE film are ~5 °C, ~13 °C, and ~17 °C, respectively. Such results prove that the coolhouse film enables high-performing passive cooling for plants, even in a very harsh environment. Results of plant cultivation with Gaillardia aristate (a typical dryness and high-temperature tolerant plant) have a similar trend as the Arabidopsis experiment (Fig. 4f, see Supplementary Fig. 14 for more test details). Therefore, the coolhouse film is repeatedly verified to have excellent passive cooling effects for plant photosynthesis. It should be noted that the current temperature (30–55 °C) may be still relatively high for some plants. In the future, it is expected that continuous effort in designing more precise spectrum, incorporating phase change materials46,47 or other novel cooling technologies (e.g., radiative cooling13,14, synergetic radiative and evaporative cooling48,49), and integrating with some mature cooling methods in the greenhouse (e.g., micro-fog cooling, wet pad cooling system, or even air conditioner) can enable further decrease in the temperature.

Besides the verifications for cooling effects, we further evaluate the water-saving effects of the coolhouse film, which is crucial, especially for cultivating plants in areas with severe water stress or regional water scarcity. The rate of soil water loss under natural wind therefore is tested via an open setup (see Supplementary Figs. 15 and 16 for more test details). The results in Fig. 4g show that the ratio of water loss is halved by the coolhouse film, from 70% (control group) to 33%. Due to the effective passive cooling and water saving effects, our recent test with soybean shows that the coolhouse film enables the highest photosynthesis rate (Supplementary Fig. 17).

Application in greenhouse crop production

With excellent capacities in passive cooling and water saving demonstrated above, the coolhouse film is poised to offer significant potential for crop cultivations in a greenhouse during hot seasons. It can be applied either alone as a free-standing feature or as a tandem layer above/below the conventional greenhouse film. As an initial demonstration, here we developed four sample chambers and mounted them in a greenhouse with averaged inner air temperature, sunlight intensity, and CO2 concentration of ~36 °C, ~560 W m−2, and ~400 ppm respectively (Supplementary Figs. 18–21). Three kinds of model plants in greenhouse, including a leafy vegetable of lettuce and fruit-producing crops of chili along with eggplant, are covered by different samples to evaluate their impacts on growth (Fig. 5a). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 22, the coolhouse film consistently shows the best performance in controlling the temperature during summer days.

a A schematic of the experiment. Different samples are covered over many crops in a greenhouse to evaluate their impacts. b–d Lettuce experiment. b A photograph of the lettuces under different samples. The lettuces under the coolhouse film have the best growing status. Scale bar, 5 cm. c Maximal efficiency of PSII chemistry for the lettuces (the mean from three trials is shown). The coolhouse film is capable of enhancing the photosynthesis rate of lettuces under temperature and water stress cultivations. d Fresh and dry weight of the lettuces. The coolhouse film enables the best yield. The data are presented as the mean ± s.d. (n = 8); the error bars indicate measurement variations. e–h Chili experiment. e A photograph shows the chilis under the coolhouse film successfully completing the most important biological processes of producing flowers and fruits. Scale bar, 2 cm. f Maximal efficiency of PSII chemistry for the chilis (the average value from three trials is shown). g Fruit fresh weight. The data are presented as the mean ± s.d. (n = 4); the error bars indicate measurement variations. Insert: a photograph of the chili fruits (scale bar, 2 cm). Only the coolhouse film with excellent passive cooling and water saving capacities enables the production of chili fruits. h Fresh and dry weight of the chilis. The data are presented as the mean ± s.d. (n = 4); the error bars indicate measurement variations. i Eggplant under the coolhouse film also realizes successful production of flows and fruits. Only the eggplants under the coolhouse film realize successful fruit production. Scale bar, 1 cm (left) and 2 cm (right). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Multiple evaluations from growth status to biological parameter and final yield all prove that the coolhouse film has the potential to enhance crop production when the temperature is high and water supply is limited (stress cultivations). The photographs of lettuces record that the coolhouse film enables the best growth (Fig. 5b). It is also measured that the lettuces under the coolhouse film have the highest maximal efficiency of PSII chemistry of 0.82 (0.56 under UV-NIR filter, 0.31 under PE film, and 0.39 in the control group), verifying that the coolhouse film enables the minimal stress on the lettuces (Fig. 5c). As a result, the dry and fresh biomass yield by the coolhouse film is more than double in comparison to the other control groups (Fig. 5d).

In addition to leafy vegetables, it is important to evaluate the performance of coolhouse film for fruit-producing crops. It is found that the chilis under the coolhouse film are capable of successfully producing flowers and fruits (Fig. 5e). The results prove that the optical management of the coolhouse film does not block the most important biological processes of chili, while a more comprehensive study of other biological properties is expected for future research. The chilis under the coolhouse film again exhibit the maximal efficiency of PSII chemistry (Fig. 5f). Finally, the fruit and biomass yield under the coolhouse film are the highest as well (Fig. 5g and h). It is interesting to find that the chilis under the coolhouse film are the only ones that bear fruits. This may be due to its excellent passive cooling and water saving capacities. Additionally, we carried out tests with eggplant. The results show a very consistent trend as observed in the chili test (Fig. 5i and Supplementary Fig. 23). Based on the above tests from leafy vegetables to fruit-producing crops, it is clear that the coolhouse film enables the highest enhancement for photosynthesis; therefore, showing great promise in increasing the crop resistance in hot and arid environments.

Discussion

In summary, with the assistance of a hybrid inverse design based on machine learning, we conceptually propose and experimentally demonstrate a scalable coolhouse film out of hundreds of possible designs that selectively permits the transmission of 400–500 nm and 600–700 nm sunlight that are effective for photosynthesis, while reflecting the other components of sunlight with weak angle dependence between −50° to 50°. Such a reflection-selective film enables effective passive cooling and water-saving for plants without affecting photosynthesis. The indoor experiments and field tests consistently verify that our coolhouse film offers an ideal local environment for photosynthesis in terms of light, temperature, and water compared with a UV-NIR filter, PE film, and control group without any covering. Plant cultivations both outdoors and in a greenhouse further prove that our coolhouse film can significantly enhance the plant’s resistance to high temperatures and arid conditions compared with traditional methods. The coolhouse film reported here realize effective and eco-friendly passive cooling and water-saving for plant photosynthesis without extra energy/water consumption. It is also expected that the synergetic machine learning method will provide a powerful toolbox for designing advanced photonic structures and devices.

Although this work has preliminarily demonstrated the great promise of the coolhouse film in plant cultivation, many aspects should be carefully studied in future research. First, it is necessary to comprehensively evaluate the sunlight requirements for different plants and develop convenient methods for designing customized coolhouse films. This requires deep interdisciplinary cooperation among materials scientists, optical experts, biologists, and agricultural scientists. Second, large-scale trials under thorough evaluation standards are crucial to further proving the coolhouse film’s impact in practical applications. Research institutions, the industrial sector, and policymakers must work closely together to achieve this. Third, our coolhouse film is mainly aimed at hot and dry areas. It may have counterproductive impacts during cold days, which can be avoided by rolling up the film during the cold season, either automatically or manually, as done in modern greenhouses with automatic indoor/outdoor shade screens and manual greenhouse insulation membranes. More ideally, it is asking for developing some smart temperature-responsive materials without affecting the optical functions of the coolhouse film to enable autonomous switch.

Methods

Definition of spectral error, angle dependence, and difficulty of fabrication

The spectral error (SE) for normal incidence of light is defined as:

where \(\lambda\) is the wavelength and \(W(\lambda )\) describes the energy weight of sunlight associated with each wavelength. \(T(\lambda )\) and \({T}^{*}(\lambda )\) are denoted as the transmission spectrum of the designed structure at normal incidence and target transmission spectrum, respectively. \({N}_{W}\) is the number of wavelength data used in the calculation.

The angel dependence (AD) of spectral is defined as:

where \({T}_{\theta }^{{TE}}\) \((\lambda )\) and \({T}_{\theta }^{{TM}}\) \((\lambda )\) denote the TE polarization and TM polarization transmissivity of the actual design at an incident angle from 0° to 50°, respectively. \({N}_{A}\) is the number of angular channels used in the calculation.

The difficulty of fabrication (DF) is defined as:

where, L is the total number of layers, T is the total thickness, and N is the total number of materials used in the design.

Fabrication of the coolhouse film

The coolhouse film was fabricated using electron beam evaporation on top of a 1 mm-thick quadrate quartz (15 by 15 cm) or 0.1 mm-thick PET (1.6 m by 0.3 m) substrate. 130 nm-thick of TiO2, 130 nm-thick of MgF2, 17 nm-thick of Ag, 188 nm-thick of TiO2, 57 nm-thick of MgF2, and 88 nm-thick of TiO2 were sequentially deposited on the substrate to form the coolhouse film. The thicknesses of each layer were real-time monitored using a quartz crystal monitor during deposition.

Material characterizations

The cross-sectional microscopic image of the coolhouse film was captured via an scanning electron microscopy (SEM; MIRA3, TESCAN). The transmissivity of samples in the ultraviolet, visible, and near-infrared wavebands were measured using the spectrophotometers (UV-3600, SHIMADZU or LAMBDA 1050 + , PerkinElmer) equipped with an integrating sphere (ISR-310 or LAMBDA 150-mm InGaAs). The angular reflectivity spectrum was measured using the spectrophotometer (Cary7000, Agilent).

Indoor cooling tests

The temperature was monitored by K-type thermocouples and real-time recorded by a recorder (MIK R6000C, Asmik). The water mass change in the indoor test (windless), used to calculate the evaporation rate, was measured in real-time by a high-accuracy balance (FA 2004, 0.1 mg in accuracy). The sand used in this test was collected from a desert (Ulan Buh Desert, China). A xenon lamp (Solar-500, Yingwave Optics) with an optical filter for the standard AM 1.5 G spectrum was used as the illuminant (see Supplementary Fig. 10 for the photograph). The light intensity was calibrated by a thermopile power sensor (GCI-080250, Daheng Optics).

Field cooling tests

The temperature was monitored through the same method used in indoor test. All the plants were planted in soil from Klasmann-Deilmann company (TS 1, 876) with pots. In the Arabidopsis experiment, the seed (Col-0) were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC). The seedings were first cultivated for 2 weeks and the ones with similar growth status were used for the following tests. During the experiment, the number of Arabidopsis in each control group was 2 pots with 15/16 seedings per pot. The total growing days under different control samples are 16 (starting from November 6th). While in the Gaillardia aristate experiment, the seeds were obtained from Alibaba. The seedings after 3 weeks of cultivation were selected and used in the tests (3 pots with 3 seedings per pot in each control group). The growing days under different control samples are 5 (starting from August 16th). The fresh weight of the plant was measured by a high-accuracy balance (FA 2004, 0.1 mg in accuracy). The water loss of soil was obtained by an electric balance (JH30002, Jiahe; Supplementary Fig. 16). The ratio of water loss was obtained by dividing the water loss by the original water content in the soil. The photosynthesis rate of soybean was measured with a portable photosynthesis system (LI-COR LI-6400XT). The power of incident sunlight is recorded by a solar radiation meter (TBQ) or a handheld solar power meter (1333 R, TES).

Greenhouse tests

The experiment was conducted in a greenhouse located in Sydney from December to January. The greenhouse has a glass roof (Viridian VFloatTM, clear glass, 4 mm thick). Its visible light (380–780 nm) transmission, solar (300–2500 nm) transmission, and U value are 89%, 79%, and 5.9 W m−2, respectively. The dimensions of this greenhouse are presented in Supplementary Fig. 18. Lettuce, chili, and eggplant were selected as the model corps. The lettuce, chili, and eggplant seedings were purchased from Bunnings (Australia). They were cultivated in soil from Scotts company (Premium porting soil, 0.07-0.01-0.03) under hospitable conditions for around 2.5 weeks. To make sure that the final differences in experiment results are only attributed to the different samples, the seedings with similar growth states were screened for the following tests. Then 8/4/3 pots of lettuce/chili/eggplant were used in each control group. The total growing days of lettuce, chili, and eggplant are 20, 27, and 31 (all starting from December 14th), respectively. During the test, we manually watered the plants every 2 days with ~50 g per pot. No fertilizer (including carbon dioxide) was further intentionally added. The dry/fresh weight and temperature were tested in the same ways in the above experiments. The maximal efficiency of PSII chemistry was tested by an advanced continuous excitation chlorophyll fluorimeter (Handy PEA + , Hansatech Instruments Ltd). During the measurement, a dark acclimatization process (about 30 min) was performed on all leaves. Then, a 1-s flash of 650 nm light with an intensity of 1500 μmol m−2 s−1 from three light-emitting diode arrays in the sensor was applied on the surface of a 4 mm-diameter leaf, inducing a fluorescence response. We performed the dark treatment separately for each plant and measured its maximal efficiency of PSII photochemistry. We repeated this step three times for each group to obtain the average value.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data are available in the main text or the supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code to reproduce these findings are available in Figshare: https://figshare.com/s/b8907a08e6877832e1f3.

References

Hanjra, M. A. & Qureshi, M. E. Global water crisis and future food security in an era of climate change. Food Policy 35, 365–377 (2010).

Gupta, P., Singh, J., Verma, S., Chandel, A. S. & Bhatla, R. Water Conservation in the Era of Global Climate Change, Vol. 472 (Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2021).

The World Bank. “Water in Agriculture”. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/water-in-agriculture#1 (2020).

Mekonnen, M. M. & Hoekstra, A. Y. Four billion people facing severe water scarcity. Sci. Adv. 2, e1500323 (2016).

Khan, F. A., Kurklu, A., Qasid, A. G., Muhammad, A. & Shahzaib, U. A review on hydroponic greenhouse cultivation for sustainable agriculture. Int. J. Agric. Environ. Food Sci. 2, 59–66 (2018).

Lakhiar, I. A., Gao, J., Syed, T. N., Chandio, F. A. & Buttar, N. A. Modern plant cultivation technologies in agriculture under controlled environment: a review on aeroponics. J. Plant Interact. 13, 338–352 (2018).

Choaba, N. et al. Review on greenhouse microclimate and application: design parameters, thermal modeling and simulation, climate controlling technologies. Sol. Energy 191, 109–137 (2019).

Tong, G., Chen, Q. & Xu, H. Passive solar energy utilization: a review of envelope material selection for Chinese solar greenhouses. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 50, 101833 (2022).

Li, H. Technology and studies for greenhouse cooling. World J. Eng. Technol. 3, 73 (2015).

Abdulrahim, A. M. et al. Recent patents on greenhouse cooling techniques: a review. Recent Pat. Eng. 15, 338–355 (2021).

Kumar, K. S., Tiwari, K. N. & Jha, M. K. Design and technology for greenhouse cooling in tropical and subtropical regions: a review. Energy Build. 41, 1269–1275 (2009).

Rephaeli, E., Raman, A. & Fan, S. Ultrabroadband photonic structures to achieve high-performance daytime radiative cooling. Nano lett. 13, 1457–1461 (2013).

Raman, A. P., Anoma, M. A., Zhu, L., Rephaeli, E. & Fan, S. Passive radiative cooling below ambient air temperature under direct sunlight. Nature 515, 540–544 (2014).

Fan, S. & Li, W. Photonics and thermodynamics concepts in radiative cooling. Nat. Photonics 16, 182–190 (2022).

Zhai, Y. et al. Scalable-manufactured randomized glass-polymer hybrid metamaterial for daytime radiative cooling. Science 355, 1062–1066 (2017).

Hsu, P. et al. Radiative human body cooling by nanoporous polyethylene textile. Science 353, 1019–1023 (2016).

Mandal, J. et al. Hierarchically porous polymer coatings for highly efficient passive daytime radiative cooling. Science 362, 315–319 (2018).

Li, T. et al. A radiative cooling structural material. Science 364, 760–763 (2019).

Leroy, A. et al. High-performance subambient radiative cooling enabled by optically selective and thermally insulating polyethylene aerogel. Sci. Adv. 5, eaat9480 (2019).

Zhou, L. et al. A polydimethylsiloxane-coated metal structure for all-day radiative cooling. Nat. Sustain. 2, 718–724 (2019).

Zeng, S. et al. Hierarchical-morphology metafabric for scalable passive daytime radiative cooling. Science 373, 692–696 (2021).

Tang, K. et al. Temperature-adaptive radiative coating for all-season household thermal regulation. Science 374, 1504–1509 (2021).

Shen, Y. et al. Energy/water budgets and productivity of the typical croplands irrigated with groundwater and surface water in the North China Plain. Agric. For. Meteorol. 181, 133–142 (2013).

Wang, Y. et al. Characteristics of carbon, water, and energy fluxes on abandoned farmland revealed by critical zone observation in the karst region of southwest China. Agric., Ecosyst. Environ. 292, 106821 (2020).

Lei, H. & Yang, D. Interannual and seasonal variability in evapotranspiration and energy partitioning over an irrigated cropland in the North China Plain. Agric. Meteorol. 150, 581–589 (2010).

Kendy, E. et al. A soil‐water‐balance approach to quantify groundwater recharge from irrigated cropland in the North China Plain. Hydrol. Process. 17, 2011–2031 (2003).

Chang, S.-Y., Cheng, P., Li, G. & Yang, Y. Transparent polymer photovoltaics for solar energy harvesting and beyond. Joule 2, 1039–1054 (2018).

Shen, L. et al. Increasing greenhouse production by spectral-shifting and unidirectional light-extracting photonics. Nat. Food 2, 434–441 (2021).

Ebbesen, T. W., Lezec, H. J., Ghaemi, H. F., Thio, T. & Wolff, P. A. Extraordinary optical transmission through sub-wavelength hole arrays. Nature 391, 667–669 (1998).

Liu, H. & Lalanne, P. Microscopic theory of the extraordinary optical transmission. Nature 452, 728–731 (2008).

Fink, Y. et al. A dielectric omnidirectional reflector. Science 282, 1679–1682 (1998).

Li, W., Shi, Y., Chen, K., Zhu, L. & Fan, S. A comprehensive photonic approach for solar cell cooling. ACS Photonics 4, 774–782 (2017).

Liu, D., Tan, Y., Khoram, E. & Yu, Z. Training deep neural networks for the inverse design of nanophotonic structures. ACS Photonics 5, 1365–1369 (2018).

Golberg, D. E. Genetic Algorithms in Search, Optimization, and Machine Learning, Vol. 432 (Addion Wesley, 1989).

Martin, S., Rivory, J. & Schoenauer, M. Synthesis of optical multilayer systems using genetic algorithms. Appl. Opt. 34, 2247–2254 (1995).

Schubert, M. F. et al. Design of multilayer antireflection coatings made from co-sputtered and low-refractive-index materials by genetic algorithm. Opt. Express 16, 5290–5298 (2008).

Moscato, P. On Evolution, Search, Optimization, Genetic Algorithms and Martial Arts-Towards Memetic Algorithms. https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=1621282 (1989).

Patel, S. J. & Kheraj, V. Optimization of the genetic operators and algorithm parameters for the design of a multilayer anti-reflection coating using the genetic algorithm. Opt. Laser Technol. 70, 94–99 (2015).

Liu, Z. et al. Compounding meta‐atoms into metamolecules with hybrid artificial intelligence techniques. Adv. Mater. 32, 1904790 (2020).

Huntington, M. D., Lauhon, L. J. & Odom, T. W. Subwavelength lattice optics by evolutionary design. Nano Lett. 14, 7195–7200 (2014).

Ma, W. et al. Pushing the limits of functionality‐multiplexing capability in metasurface design based on statistical machine learning. Adv. Mater. 34, 2110022 (2022).

Zhu, R. et al. Deep-learning-empowered holographic metasurface with simultaneously customized phase and amplitude. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 48303–48310 (2022).

Ma, W. et al. Deep learning for the design of photonic structures. Nat. Photonics 15, 77–90 (2021).

Al-Helal, I. M., Alzahrani, S. M., Alsadon, A. A., Ali, I. M. & Elleithy, R. M. Covering materials incorporating radiation-preventing techniques to meet greenhouse cooling challenges in arid regions: a review. Sci. World J. 2012, 906360 (2012).

Pakari, A. & Ghani, S. Evaluation of a novel greenhouse design for reduced cooling loads during the hot season in subtropical regions. Sol. Energy 181, 234–242 (2019).

Nie, B. et al. Review on phase change materials for cold thermal energy storage applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 134, 110340 (2020).

Akeiber, H. et al. A review on phase change material (PCM) for sustainable passive cooling in building envelopes. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 60, 1470–1497 (2016).

Li, J. et al. A tandem radiative/evaporative cooler for weather-insensitive and high-performance daytime passive cooling. Sci. Adv. 8, eabq0411 (2022).

Yao, H. et al. Integrated radiative and evaporative cooling beyond daytime passive cooling power limit. Nano Res. Energy 2, e9120060 (2023).

Gao, M., Zhu, L., Peh, C. K. & Ho, G. W. Solar absorber material and system designs for photothermal water vaporization towards clean water and energy production. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 841–864 (2019).

Artiola, J. F., Brusseau, M. L. & Pepper, I. L. Environmental Monitoring and Characterization, Vol. 410 (Academic Press, 2004).

Mondal, B. P. Hyper-spectral analysis of soil properties for soil management. Adv. Agric. Sustain. Dev. 17, 2252 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the micro-fabrication center at the National Laboratory of Solid State Microstructures (NLSSM) for technical support. J.Z. acknowledges support from the XPLORER PRIZE. This work was jointly supported by the National Key Research and Development Programme of China (2022YFA1404704 and 2020YFA0406104), National Natural Science Foundation of China (52372197), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20231540), Excellent Research Programme of Nanjing University (ZYJH005), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (021314380184, 021314380208, 021314380190, 021314380140, and 021314380150), and State Key Laboratory of New Textile Materials and Advanced Processing Technologies (Wuhan Textile University, No. FZ2022011). W.L. acknowledges the support of National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 62134009 and 62121005) and the Innovation Grant of Changchun Institute of Optics, Fine Mechanics and Physics (CIOMP). S.F. acknowledges the support of US Department of Energy (No. DE-FG-07ER46426).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L., N.X., B.Z., and J.Z. conceived the idea. J.L., Y.J., and H.S. designed and performed experiments. B.L., Y.X., Y.L., W.L, and S.F. did the optical calculations. D.Z. and Y.Z. provide important suggestions for the plant stress tests. P.W., Z.L., S.S., and J.W. offered excellent support from plant science. K.Z., B.Z., W.L., Y.L., S.F., and J.Z. supervised the project. J.L., Y.J., B.L., and Y.X. wrote the manuscript. M.Z., Q.L., B.Z., W.L., Y.L., S.F., and J.Z. revised the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Md Shamim Ahamed, and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Jiang, Y., Li, B. et al. Accelerated photonic design of coolhouse film for photosynthesis via machine learning. Nat Commun 16, 1396 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54983-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54983-8

This article is cited by

-

Radiative cooling drives the integration and application of thermal management in flexible electronic devices

npj Flexible Electronics (2025)