Abstract

Understanding how symmetry-breaking processes generate order out of disorder is among the most fundamental problems of nature. The scalar Higgs mode – a massive (quasi-) particle – is a key ingredient in these processes and emerges with the spontaneous breaking of a continuous symmetry. Its related exotic and elusive axial counterpart, a Boson with vector character, can be stabilized through the simultaneous breaking of multiple continuous symmetries. Here, we employ a magnetic field to tune the recently discovered axial Higgs-type charge-density wave amplitude modes in rare-earth tritellurides. We demonstrate a proportionality between the axial Higgs component and the applied field, and a 90° phase shift upon changing the direction of the magnetic field. This indicates that the axial character is directly related to magnetic degrees of freedom. Our approach opens up an in-situ control over the axial character of emergent Higgs modes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Charge-density wave (CDW) phases play an essential role in condensed matter physics, where they are closely linked to exotic phases and emergent phenomena, such as unconventional superconductivity1, topologically non-trivial electronic phases2, or generating novel electronic states along domain walls3,4. On a more fundamental level, charge-density waves serve as valuable platforms to explore general concepts such as the (tunability of the) nature of phase transitions, quantum criticality, and the breaking of symmetries. Especially those CDWs that are linked to unconventional ordering processes may offer access to explore phenomena postulated for high-energy particle physics. A recent polarization-resolved Raman spectroscopic study of the uni-directional charge-density wave materials GdTe3 and LaTe3 revealed a remarkable two-fold (A2) symmetry of the CDW amplitude mode at room temperature and zero magnetic fields. This low symmetry is rationalized by quantum pathway interference processes that uniquely occur in these rare-earth tritellurides with two distinct charge-density wave vectors. In contrast to other conventional CDW materials, RTe3 hosts two (nearly) degenerate nesting conditions, qCDW and c*-qCDW, connecting px–px (py–py) bands of Te, and mixing px–py (py–px) bands, respectively5,6. The resulting two-fold periodic CDW amplitudon with vector character has since been dubbed as an axial Higgs mode7, i.e., a condensed matter analogon to a highly elusive elementary particle.

Two natural questions arise: what is the microscopic mechanism that generates axialness in RTe3, and how can we control or tune the nature of the Higgs mode? Its axialness dictates the breaking of additional symmetries. We can conceive of several potentially relevant scenarios, illustrated in Fig. 1a: (i) Since GdTe3 orders antiferromagnetically below the Néel temperature TN = 11.5 K, a coupling between the Gd spins and the CDW may be a crucial component to the axial Higgs mode. (ii) A slight lattice distortion of the Te square-net units within the CDW phase may be conducive to a ferro-rotational state with axial properties. (iii) A finite orbital angular momentum (OAM) can be generated from the mixing of Te orbitals via px ± ipy, which breaks time-reversal symmetry and can respond to an external magnetic field. Motivated by this open issue, we performed a polarization-resolved Raman spectroscopy study on the two sister compounds GdTe3 (with low-temperature antiferromagnetic order) and LaTe3 (without any long-range magnetic order) at various temperatures and with applied magnetic fields. In this work, we show that the low two-fold symmetry of the Higgs mode persistently observed in both materials and across a wide range of temperatures, together with its dramatic field dependence allows us to rule out spin degrees of freedom as a relevant ingredient, and ultimately highlights the relevance of orbital degrees of freedom to stabilize axial Higgs modes in RTe3.

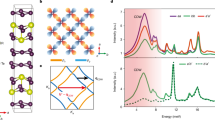

a Illustrations of potential symmetry breaking processes resulting in axial Higgs modes in GdTe3: Coupling between magnetic order in the form of a spin-density wave (SDW) and charge-density-wave (CDW) below TN; ferro-rotational lattice distortion of Te square net units; mixing between px and py orbitals enabling a finite orbital angular momentum. b Side view of alternating Te layers and slabs of GdTe (LaTe) stacked along the crystallographic b-axis. A natural cleaving plane exists between two van-der-Waals coupled Te layers (dashed line). An external magnetic field is applied out-of-plane, and the laser light (green arrow) propagates with its k-vector along the b-axis and with its polarization within the ac-plane. c Top-view (ac-plane) of the Te square lattice, with px and py orbitals drawn in blue and yellow. The configurations for parallel (cc) and crossed (ca) polarizations, later denoted as θ = 0°, are indicated by arrows.

Results

Field-tuning the Higgs mode

Figure 1b, c outlines the schematics of our experiment. Layers of [Te]–[GdTe]–[Te] building blocks are stacked along the crystallographic b-axis8, with unidirectional CDW order emerging within the Te square lattice along the a or the c direction9. The incident laser light direction and the magnetic field are both aligned out-of-plane, i.e., along the b-axis. We probe the excitations with light polarized within the ac-plane. The configurations sketched in Fig. 1c correspond to cc (in parallel configuration) and to ca (in crossed polarization), and are later on denoted as θ = 0° (see below). Within this scheme, we obtain highly polarization-resolved Raman data by continuously rotating the light polarization within the ac-plane, while keeping a fixed relation between ein and eout.

Let us first focus on Raman spectra taken at zero applied field in parallel and crossed polarizations, shown as solid blue lines in Fig. 2a top and bottom panels, respectively. The spectra consist of phonons (mainly in the energy range from 12 – 20 meV) and of CDW amplitude (Higgs-) modes at 9.1 meV and 10.8 meV, marked by black arrows (for a detailed thermal evolution of Raman-active modes see Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). In parallel polarization the CDW modes clearly dominate the spectrum, while in crossed polarization their intensities are significantly reduced compared to other phonon modes.

a As-measured Raman spectra of GdTe3 collected at T = 2 K in parallel (top panel) and crossed (bottom panel) polarization at 0 T and at + 7 T. Arrows mark the Higgs-type amplitude modes of the CDW phase. The asterisks mark zone-folded phonons that couple to the CDW. b Integrated intensity of the amplitude mode at 9.1 meV as a function of polarization direction within the ac-plane at various fields in parallel (top panel) and crossed (bottom panel) polarization. Dashed gray lines denote the polarization direction with respect to the crystallographic axes.

Next, we apply an out-of-plane magnetic field to the sample, the corresponding Raman spectra are plotted as solid red lines. In crossed polarization, the CDW amplitude modes, barely observable at 0 T, suddenly dominate the Raman spectrum at 7 T. On the other hand, phonon modes around 13, 15, and 18 meV are robust against magnetic fields. Note that the intensities of two of the phonons (marked by asterisks) mimic the field-induced behavior of the CDW mode. This does not necessarily indicate a field-induced structural transition or lattice distortion and is most likely related to a coupling between this particular phonon and the CDW (see Supplementary Notes 1 and 2, and Supplementary Fig. 2). As we discuss below, there is a distinct difference in the field evolution between these somewhat anomalous phonons and the CDW excitation. In contrast to the remarkable field-enhancement of CDW modes observed in crossed polarization, we find that in parallel polarization a magnetic field of 7 T only moderately changes the intensities of several excitations, but no fundamental difference is observed between measurements at 0 T and + 7 T. To remove any effect related to a particular sample orientation, the spectra shown in Fig. 2a were averaged while rotating the light polarization from 0° to 360° in either parallel or crossed relation.

A key observation of a previous Raman spectroscopy study on GdTe3 carried out at zero magnetic field was the unusually low two-fold symmetry of the Higgs-type CDW amplitude modes observed in both parallel and crossed polarizations, which was taken as experimental evidence for the simultaneous and spontaneous breaking of multiple symmetries, enabling the formation of a CDW amplitude mode with vector character, i.e., an axial Higgs mode instead of a conventional scalar one7. The symmetry of excitations can be investigated via polarization-resolved Raman spectroscopy by rotating the polarization of the laser light within the crystallographic ac-plane from 0° to 360° (see Supplementary Notes 3 and 4 for the full data set). Extracting the integrated intensity of the amplitude mode at 9.1 meV as a function of polarization and magnetic field yields the plots shown in Fig. 2b (the neighboring mode at 10.8 meV mimics this behavior, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). In the upper panel, we detail the symmetry of the Higgs mode probed in parallel polarization at 0 T and at + 7 T. A clear two-fold (180°) symmetry is observed with and without magnetic fields, in good agreement with the previous Raman study7. In crossed polarization, shown in the bottom panel, a magnetic field dependence becomes strikingly clear: while at zero magnetic fields, the symmetry is close to four-fold (with a weak two-fold modulation on top; see Supplementary Note 5 with Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6 for a detailed analysis of the periodicity at B → 0), at applied magnetic fields the two-fold symmetry becomes remarkably dominant. Moreover, a 90° phase shift is induced by changing the out-of-plane field direction from positive to negative. In both configurations, parallel and crossed, the intensity and periodicity of phonon modes that do not directly couple to the CDW remain fully field-independent (see Supplementary Note 6 with Supplementary Fig. 7 for line cuts of phonons at 15 and 18 meV).

Implications of the Higgs-mode character on its symmetry

To account for such low two-fold symmetry in both parallel and crossed scattering configurations requires a Raman tensor with anti-symmetric off-diagonal tensor elements, as described in a previous Raman scattering study7:

Here, the empty tensor elements (…) reflect the notion that we carry out experiments exclusively within the ac plane and, therefore, cannot access any tensor elements related to the crystallographic b direction. In the parallel configuration, the polarizations of the incident and scattered light are parallel to each other, ein // eout, while in the crossed configuration eout is shifted by 90° with respect to ein. As the Raman scattered intensity I is given by I ∝ ∣ein ⋅ Raxial ⋅ eout∣2, we can express the angular dependence of the Higgs mode intensity as \(I(\theta )\propto | \gamma+(\alpha -\gamma )\cdot {\cos }^{2}\theta {| }^{2}\) for parallel polarization, and \(I(\theta )\propto | 1/2\cdot (\alpha -\gamma )\cdot \sin (2\theta )-\beta {| }^{2}\) for crossed polarization. As we note from these equations, the Raman scattering intensity in parallel polarization is solely determined by the diagonal tensor elements α and γ, while the off-diagonal element β becomes relevant for the scattering intensity in crossed polarization. Thus, using the dataset recorded in parallel polarization, we extract values for α and γ (shown in Supplementary Note 7), which then allow us to accurately determine β as a single fitting parameter from the crossed-polarization dataset. Fits of these angle-dependent intensity curves to the data shown in Fig. 2b are indicated by solid lines. Based on these fits and on the stark difference between parallel and crossed configurations with and without applied fields, we conclude that the tensor elements α and γ remain (mostly) field-independent, while the field-dependent Higgs mode intensity observed in crossed polarization is dictated by the field-dependence of Raman tensor element β. We also recall that – based on symmetry considerations – effects of hybridization between px and py should only be accessible in crossed polarization and absent in parallel configuration6. Therefore, tensor element β may offer a direct glimpse into the effects of applied magnetic field on orbital hybridization.

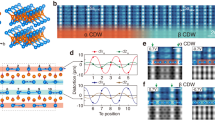

To quantify the field-dependence of β, we now continuously tune the out-of-plane magnetic field from + 7 T to − 5 T in steps of 1 T, and plot the intensity of the CDW amplitude mode measured in crossed configuration as a function of in-plane light polarization in the color contour plot of Fig. 3a. Note that these detailed field-dependent measurements have been carried out on a different GdTe3 specimen ("sample 2”) from the one discussed in Fig. 2 ("sample 1”). This has been done to demonstrate the reproducibility of the observed field-dependent effect. In Fig. 3b we plot the fitted values of the Raman tensor element β as a function applied magnetic field (red circles). For direct comparison, we show the extracted values of β from “sample 1” and from a third specimen “sample 3” in Supplementary Fig. 11. For all three samples β becomes strongly enhanced with increasing magnetic fields, and the observed phase shift shown in Fig. 2b for reversing magnetic field directions necessitates a sign change of β as a function of field direction. Summarizing our results, we find that Raxial can aptly describe our data and that tensor element β appears to be close to proportional to the applied magnetic field B (see Supplementary Note 8 and Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13). An important question is whether this field-tuning is uniquely observed for the CDW amplitudon, or if other excitations show comparable anomalies. Indeed, the high-energy CDW shoulder located at 10.8 meV shows an identical behavior, as seen in Fig. 3c. The zone-folded phonon located at 12 meV also evidences some appreciable field-dependence (Fig. 3d), although it is more subtle and with a 90° phase shift with respect to the amplitudon. In Fig. 3e we plot the field-dependence of a reference phonon located at 15 meV with no field-dependence whatsoever, while a second zone-folded phonon at 17 meV keeps its four-fold periodicity and phase independent of the magnetic field, and only evidences a general field-induced increase in intensity (Fig. 3f). We thus conclude that only the CDW amplitudon is dramatically affected by magnetic fields and that some of the CDW-coupled zone-folded phonons show their own distinct but more subtle field-induced anomalies. This also underlines our assumption that all observed effects are intrinsic to the sample rather than extrinsic experimental artifacts, which should not distinguish between amplitudons and phonons. In the following, we will rationalize the observed field stabilization of the axial Higgs mode, the phase shift with reversing field direction, and the existence of off-diagonal anti-symmetric tensor elements in Raxial, by considering either the orbitals or ferro-rotational lattice distortion involved in the CDW and Raman scattering processes.

a Integrated scattering intensity of the CDW amplitude mode at 9.1 meV in GdTe3 as a function of out-of-plane field strength and light polarization with ein⊥ eout. At small fields, domain poling effects contribute, while at higher fields the axialness of the Higgs mode increases linearly with B, as indicated by the arrow on the right. Crystallographic axes are indicated at the top. All data was acquired at T = 2 K. b Field-dependent Raman tensor element β extracted from fits to the integrated intensity plotted in panel (a). The standard deviation for each fitted value is within the size of the symbols. The data at B = 0 has been omitted due to ambiguity in fitting (see Supplementary Note 7 and Supplementary Figs. 8–11 for details). The dashed line is a guide to the eyes. The field regime dominated by field-poling effects is indicated by a shaded background. c–f Field- and polarization angle dependence of the Raman scattering intensity for four selected modes (10.8 meV, 12 meV, 15 meV, and 17 meV) measured with ein⊥ eout at T = 2 K.

Discussion

The drastic effect of out-of-plane fields on the Higgs mode intensity and on its symmetry requires the presence of intrinsic magnetic degrees of freedom in GdTe3. Here, we will propose and discuss three scenarios, following the illustrations shown in Fig. 1a. Considering the magnetic field dependence, a plausible scenario is that spin degrees of freedom in GdTe3 are the relevant ingredient. In GdTe3, the Gd spins order antiferromagnetically below TN = 11.5 K10 with magnetic moments aligned within the plane, which could result in an interplay between magnetic order and the CDW. We can rule this first scenario as unlikely based on the following observations: As shown in Supplementary Notes 9 and 10 with Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15, the same field-induced behavior of the Higgs modes is seen below and well above TN. Furthermore, a detailed look at the thermal evolution of Raman active modes reveals the absence of any significant anomalies across TN. More importantly, the non-magnetic sister compound LaTe3 evidences an identical response of its CDW mode to applied magnetic fields.

A second, more likely scenario that is discussed in the context of order parameters with axial-vector character is ferro-rotational order11,12,13. Such order, driven by lattice distortion within the CDW phase, does not by itself couple to electromagnetic fields. It may, however, activate chiral phonons that, in turn, generate intrinsic magnetic moments14, or affect the orbital overlap, which could be further tuned by magnetic fields. Our data may, to some extent, support this scenario, as two Ag-symmetric phonon modes respond to applied magnetic fields (see the asterisk-marked phonons in Fig. 2a). On the other hand, if the drastic amplitude-mode field-tuning is a secondary effect of magneto-elastic coupling, one might expect a significant continuous evolution of phonon frequencies with magnetic fields. In that sense, none of the Raman-active phonons suggest any obvious magneto-elastic coupling (Supplementary Note 2), and clear fingerprints for chiral phonons are lacking (Supplementary Note 11 and Supplementary Fig. 16).

Our third scenario is based on a direct orbital-driven mechanism without invoking lattice degrees of freedom and involves field-tuned hybridization between Te px and py orbitals. As was pointed out in previous studies, the interference between qCDW and the additional CDW vector c*-qCDW resulting from such hybridization determines the axialness of the Higgs mode and, thereby its Raman scattering intensity for light polarization configurations compatible with the wave vector6,7. A hybridization px ± ipy is associated with a finite OAM mℓ. Hence, applying a magnetic field B will directly affect the mixing of orbitals. In the balanced case (mℓ = 0) the hybridization and the interference with c*-qCDW both vanish. Therefore, the amplitudon would recover its conventional scalar form. Once mℓ assumes a finite value (i.e., the degeneracy between (px + ipy) and (px − ipy) is lifted upon application of a magnetic field), hybridization becomes finite and therefore an interplay between qCDW and c*-qCDW dictates the Raman scattering intensity of the now axial Higgs mode (indicated by the red- and blue-shaded regions around the Fermi energy EF in Fig. 4). The corresponding transitions involved in this Raman scattering process are sketched in Fig. 4 in the framework of a single-particle spectral function. Although CDW order leaves the Fermi surface partially ungapped15, we here consider the region in momentum space that is most relevant for our Raman scattering process. Based on this scenario the off-diagonal Raman tensor element can be expressed as \(\beta \, \sim \langle {\varphi }_{{{\rm{v}}}}| \hat{y}| {\varphi }_{{{{\rm{c}}}}^{{\prime} }}\rangle \langle {\varphi }_{{{{\rm{c}}}}^{{\prime} }}| {\hat{H}}_{{{\rm{el-CDW}}}}| {\varphi }_{{{\rm{c}}}}\rangle \langle {\varphi }_{{{\rm{c}}}}| \hat{x}| {\varphi }_{{{\rm{v}}}}\rangle\), where \(\hat{x}\) and \(\hat{y}\) are orthogonal electric dipole operators16,17, and φv and φc (\({\varphi }_{{{{\rm{c}}}}^{{\prime} }}\)) are electronic states in the valence- and conduction band. Here, the Hamiltonian \({\hat{H}}_{{{\rm{el-CDW}}}}\) yields the off-diagonal hopping element \({\hat{H}}_{{{\rm{xy}}}}\), when φc and \({\varphi }_{{{{\rm{c}}}}^{{\prime} }}\) are orthogonal to each other. In this scattering configuration, β is intimately linked to \({\hat{H}}_{{{\rm{xy}}}}\), and thereby allows us to directly probe the degree of hybridization between px and py, which is governed by \({\hat{H}}_{{{\rm{xy}}}} \sim {{\bf{B}}}\cdot {{{\bf{m}}}}_{\ell }\). This also implies that in contrast to out-of-plane magnetic fields, in-plane magnetic fields would leave the hybridization between px and py invariant, resulting in a field-independent Raman response of the CDW amplitudon. Future magneto-Raman scattering experiments carried out in Voigt geometry may, therefore, ultimately confirm our hypothesis.

a A gapless state at T > TCDW. b Below TCDW a charge-density wave gap (ΔCDW) opens around the region relevant for the Raman scattering process. The system is in its ground state. c The Raman scattering process probing the axial Higgs mode: An incident photon with energy hν (green arrow) excites an electron from the valence band to an unoccupied state across ΔCDW, which couples to an amplitudon (red and blue shaded areas around ΔCDW) in a second step. In the final step, the electron recombines with the hole and emits a photon with energy \(h\nu {\prime}\) (orange arrow) with a polarization orthogonal to that of the incident photon.

Finally, let us comment on subtle differences between our work and the previous Raman scattering study on GdTe3. While Wang, et al. reported a pronounced two-fold symmetric (i.e., axial) Higgs mode in crossed polarization for B = 0 at both room temperature as well as 8 K7, our data taken at 2 K without magnetic field is more ambiguous with a weak and almost 4-fold periodic Higgs mode. A key difference between our methodologies is the laser spot diameter during the Raman experiment, which is as tight as 2 μm in the former case, while in our experiment it is spread out to about 100 μm, thereby averaging over a much larger sample area. To facilitate a better comparison, we also conducted room temperature experiments at zero fields with a tightly focused spot diameter of about 2 μm, which yielded a clear two-fold periodicity (see Supplementary Note 5). Based on these observations, we conjecture that twin domains are prevalent throughout the sample on a length scale of a few micrometers, which will mostly average out any intrinsic imbalance between + mℓ and − mℓ at B = 0 T when integrating the Raman signal over a large-enough sample area. Indeed, such twin domains were recently uncovered in GdTe3 via scanning tunneling microscopy18, and their existence would naturally explain the subtle hysteresis behavior seen around small fields for β(B) in Fig. 3b. In Supplementary Note 12 and Supplementary Fig. 17 we compare room temperature spectra of GdTe3 with and without magnetic field, which clearly highlight a field-induced increase in Higgs mode intensity. Conspicuously, all these observations demand that a weaker axial character of the Higgs mode is already developed in GdTe3 at room temperature and without any applied magnetic field. Yet, the continuous linear increase of β for higher fields supports the scenario of a field-driven control over axialness. An important implication is that with the onset of CDW order, either ferro-rotational distortion spontaneously appears or time-reversal symmetry breaks spontaneously, even at B = 0 T. To test this hypothesis, we call on future μSR investigations, circular-dichroism angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy, or scanning tunneling microscopy experiments in applied magnetic fields. If indeed time-reversal symmetry breaks spontaneously in RTe3, such studies could reveal vital insight relevant to related materials with unconventional charge-density wave order, such as vanadium-based kagome metals. Furthermore, these rare-earth tritellurites may be apt hosts for other exotic states of matter, such as chiral superconductivity, e.g., by applying hydrostatic pressure19.

Methods

Sample synthesis

Stoichiometric single-crystalline GdTe3 flakes were used for the self-flux growth method using a box furnace. High-purity Gd metal (99.9%) and Te chips (99.999%) were mixed in a 1:30 molar ratio to achieve a Te-rich self-flux condition. The mixed precursor of GdTe3 was loaded into quartz tubes and sealed at ~ 10−5 torr using a turbo pump to prevent oxygen contamination. The maximum heating temperature was set to 900 °C, and the temperature was maintained for 24 h to achieve a homogeneous melt. After melting, the sample was cooled down to 500 °C at a rate of − 2 °C per hour. The melt in the ampule was decanted at room temperature until it turned solids.

Raman scattering

Samples were mechanically exfoliated right before being transferred into the He-gas filled sample chamber of a magneto-optical cryostat (Oxford SpectromagPT, \({T}_{\min }=1.6\) K, B\({}_{\max }=\pm 7\) T). Thereby, the fresh surface exposure to air was minimized to less than 5 s. While the sample remained inside the cryostat, no effects of sample degradation through the appearance of additional tellurium oxide modes20 were observed over a period of two weeks. Raman scattering experiments were carried out in backscattering geometry using a single-mode laser emitting at λ = 561 nm (Oxxius-LCX) and a laser power of 0.6 mW or less at the sample position. The laser was focused onto the sample via a series of achromatic lenses, resulting in a beam spot diameter of about 100 μm (for details about the beampath see Supplementary Note 13 and Supplementary Fig. 18). The in-plane light polarization was controlled using a superachromatic λ/2 waveplate (Thorlabs) in front of the sample. Raman-scattered light was dispersed and recorded through a Princeton Instruments TriVista 777 spectrometer and a PyLoN eXcelon charge-coupled device, respectively. For field-dependent measurements samples were first zero-field cooled to T = 2 K, followed by a magnetic field ramp up to + 7 T. From there, data was collected while decreasing the field in steps of 1 T through B = 0 and down to − 5 T. Additional zero-field Raman spectra were collected using a home-built microscope stage with a laser spot diameter at the sample surface of about 2 μm and the sample mounted inside an open-flow cryostat (Oxford MicroStat HR).

Data availability

The datasets generated in this study have been deposited in the Figshare database under the https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25722585.

References

Mielke III, C. et al. Time-reversal symmetry-breaking charge order in a kagome superconductor. Nature 602, 245–250 (2022).

Gooth, J. et al. Axionic charge-density wave in the Weyl semimetal (TaSe4)2I. Nature 575, 315–319 (2019).

Sipos, B. et al. From Mott state to superconductivity in 1T-TaS2. Nat. Mater. 7, 960–965 (2008).

Joe, Y. I. et al. Emergence of charge density wave domain walls above the superconducting dome in 1T-TiSe2. Nat. Phys. 10, 421–425 (2014).

Brouet, V. et al. Angle-resolved photoemission study of the evolution of band structure and charge density wave properties in RTe3 (R = Y, La, Ce, Sm, Gd, Tb, and Dy). Phys. Rev. B 77, 235104 (2008).

Eiter, H.-M. et al. Alternative route to charge density wave formation in multiband systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110(1), 64–69 (2013).

Wang, Y. et al. Axial Higgs mode detected by quantum pathway interference in RTe3. Nature 606, 896–901 (2022).

Norling, B. K. & Steinfink, H. The crystal structure of neodymium tritelluride. Inorg. Chem. 5, 1488–1491 (1966).

DiMasi, E., Aronson, M. C., Mansfield, J. F., Foran, B. & Lee, S. Chemical pressure and charge-density waves in rare-earth tritellurides. Phys. Rev. B 52, 14516 (1995).

Iyeiri, Y., Okumura, T., Michioka, C. & Suzuki, K. Magnetic properties of rare-earth metal tritellurides RTe3 (R = Ce, Pr, Nd, Gd, Dy). Phys. Rev. B 67, 144417 (2003).

Cheong, S.-W., Talbayev, D., Kiryukhin, V. & Saxena, A. Broken symmetries, non-reciprocity, and multiferroicity. Npj Quant. Mater. 3, 19 (2018).

Hlinka, J., Privratska, J., Ondrejkovic, P. & Janovec, V. Symmetry guide to ferroaxial transitions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 177602 (2016).

Liu, G. et al. Electrical switching of ferro-rotational order in nanometre-thick 1T-TaS2 crystals. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 854–860 (2023).

Ataei, A. et al. Phonon chirality from impurity scattering in the antiferromagnetic phase of Sr2IrO4. Nat. Phys. 20, 585–588 (2024).

Ru, N. et al. Effect of chemical pressure on the charge density wave transition in rare-earth tritellurides RTe3. Phys. Rev. B 77, 035114 (2008).

Cardona, M. Light Scattering In Solids I (Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg New York, 1983).

Pimenta, M. A., Resende, G. C., Ribeiro, H. B. & Carvalho, B. R. Polarized Raman spectroscopy in low-symmetry 2D materials: angle-resolved experiments and complex number tensor elements. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 23, 27103 (2021).

Lee, S. et al. Melting of unidirectional charge density waves across twin domain boundaries in GdTe3. Nano Lett. 23, 11219–11225 (2023).

Zocco, D. A. et al. Pressure dependence of the charge-density-wave and superconducting states in GdTe3, TbTe3, and DyTe3. Phys. Rev. B 91, 205114 (2015).

Gray, M. J. et al. A cleanroom in a glovebox. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 91, 073909 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge important discussions with Ken Burch, Birender Singh, Suyoung Lee, Jun-Won Rhim, Jennifer Cano, Judy Cha, Rafael Fernandez, and Eun-Gook Moon. This work was supported by the Institute for Basic Science (IBS) (Grant Nos. IBS-R009-G2 [J.P. and C.K.] and IBS-R006-Y3 [D.W.]). T.T. was supported by KAKENHI (Grant No. 24K00560) from the MEXT, Japan. S.R.P. was supported by the NRF (Grant No. 2020R1A2C1011439). C.K. was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) (Grant Nos. RS-2023-00258359 and NRF-2022R1A3B1077234).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.P. synthesized GdTe3 and LaTe3 single crystals. D.W., J.P., and C.K. performed Raman spectroscopic measurements. D.W. and C.K. analyzed the data. Symmetry analysis was carried out by T.T., S.R.P., and C.K. D.W. and C.K. wrote the manuscript with important contributions from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Yiping Wang, Naotaka Yoshikawa, and the other anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wulferding, D., Park, J., Tohyama, T. et al. Magnetic field control over the axial character of Higgs modes in charge-density wave compounds. Nat Commun 16, 114 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55355-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55355-y

This article is cited by

-

Charge transfer empties the flat band in 4Hb-TaS2, except at the surface

Communications Physics (2026)

-

Visualizing the internal structure of the charge-density-wave state in CeSbTe

Nature Communications (2025)