Abstract

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) is widely used in plant biology and is a powerful tool for studying cell identity and differentiation. However, the scarcity of known cell-type marker genes and the divergence of marker expression patterns limit the accuracy of cell-type identification and our capacity to investigate cell-type conservation in many species. To tackle this challenge, we devise a novel computational strategy called Orthologous Marker Gene Groups (OMGs), which can identify cell types in both model and non-model plant species and allows for rapid comparison of cell types across many published single-cell maps. Our method does not require cross-species data integration, while still accurately determining inter-species cellular similarities. We validate the method by analyzing published single-cell data from species with well-annotated single-cell maps, and we show our methods can capture majority of manually annotated cell types. The robustness of our method is further demonstrated by its ability to pertinently map cell clusters from 1 million cells, 268 cell clusters across 15 diverse plant species. We reveal 14 dominant groups with substantial conservation in shared cell-type markers across monocots and dicots. To facilitate the use of this method by the broad research community, we launch a user-friendly web-based tool called the OMG browser, which simplifies the process of cell-type identification in plant datasets for biologists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) technology has been widely used in characterizing various cell types in plant growth and development1,2,3,4,5,6. Tissues and organs that have been used in single-cell sequencing include root and shoot apex, leaf, inflorescence, stem, and whole plant across dozens of species7. One of the first steps in single-cell analysis is identifying cell types for each cell in a sample. This step is straightforward in Arabidopsis due to the extensive knowledge of cell-type identity markers8,9. Contrastingly, accurate labeling of cell types in other plant species remains challenging due to the scarcity of validated marker genes10. Notably, many closest orthologs of cell-type identity marker genes in Arabidopsis do not exhibit the same cell-type identity across diverse plant species11,12.

To overcome the challenge of annotating cell clusters of single-cell data from diverse plant species, many approaches have been reported, such as using literature-derived marker gene sets11, directly integrating data from diverse species12, or comparing the gene expression profiles of single-copy orthologous genes between closely related species13. In non-plant systems, a commonly used approach for cell type identification is to integrate single-cell data across species using one-to-one orthologous genes14. However, this approach is unreliable in plants due to gene family expansion and gene duplications. We have found direct integration of single-cell data from diverse plant species resulted in clusters with mixed cell identities (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Data 1). One reason for failed integration with one-to-one orthologous genes is that these genes were assigned solely based on sequence similarity; many such genes may have diverged in their cell type-specific expression levels in different plant species.

To address the limitations of integration using one-to-one orthologs, a method called SAMap15 was developed to map single-cell transcriptomes across various species by creating a gene-by-gene bipartite graph and iteratively refining it by projecting single-cell datasets into a shared manifold space. Another improved method16 identifies one-to-one gene pairs called co-expression proxies. These co-expression proxies provided better anchors for integration between rice and maize single-cell data. However, integration-based methods typically require significant computational resources for constructing and iterating the gene-gene bipartite graph or identifying co-expression proxies. To use integration-based methods for a new plant species, a user still needs to decide which species is best to integrate with; cell types in the integrated data still need to be determined by label transfer; and some cell types may not exist in the reference species.

A different approach to annotating cell types is via marker genes, as described in our method in this manuscript. In marker-based methods, single-cell data were first analyzed to generate cell clusters and cluster marker genes. Known marker genes were compared to these cluster marker genes, and cell types can be defined based on the cell type specificity of these marker genes. Notably, the marker-based approaches can be used without integration with other data. In non-plant systems, several marker-based methods have been developed17,18. However, none of these methods provided markers for plant species. When applying marker-based cell type annotation in diverse plant species, a major limitation to overcome is the challenge of expanded gene families in plants due to frequent tandem duplication and whole genome duplication, which are rare in mammalian lineages.

We reasoned that a robust strategy for marker-based cell type annotation in plants should encompass one-to-one, one-to-many, and many-to-many orthologous genes. Accordingly, we have developed a method called Orthologous Marker gene Groups (OMGs), in which cell type assignments were based on counting overlapping orthologous gene groups between a query species and a collection of reference single-cell maps. A key feature of the OMG method is a statistical test to quantify similarities between cell clusters and account for observed marker overlaps that are due to random noise. This test not only relied on the overlapping number of OMGs between two clusters but also considered the total number of overlapping OMGs in all other clusters between different species. Because our method does not require data integration, using OMGs to assign cell types to single-cell clusters is fast and scalable.

In this manuscript, we first demonstrated the cross-species comparison results using well-established single-cell maps from Arabidopsis, tomato, rice, maize, and poplar. We further showed that using OMGs as a unit to determine cell type identity enables the assignment of cell types by comparing 15 distantly related species. Our analysis revealed 14 dominant clusters with substantial conservation in shared cell-type markers across monocots and dicots.

Results

Overview of the orthologous marker groups approach

To use our method to annotate cell types in different species, we first identified the top N marker genes (N = 200) for each cell cluster in each species using an existing approach (e.g., Seurat19,20 Fig. 1a). Second, we employed OrthoFinder21 to generate orthologous gene groups for M plant species M = 15 in this study, including Arabidopsis, rice (Oryza sativa), maize (Zea mays), and tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), where high quality single-cell maps are available, and 11 other species where single-cell data have more recently become available (Fig. 1b). Third, we performed pairwise comparisons using an overlapping OMGs (ortho-marker groups) between each cluster in the query species and the reference species and visualized the results using heatmap showing the statistical test results (i.e., Fisher’s exact test, -log10FDR) to determine clusters with a significant number of shared OMGs (Fig. 1a). The number of tests equals the number of clusters from the query species times the number of clusters in the reference maps (see discussion for the choice of N, M, and the methods for ortho-group generation).

a Cell type annotation in three steps: (1) identify the top 200 marker genes for each cell cluster. (2) use OrthoFinder to generate orthologous gene groups for different species. (3) perform a pairwise comparison using an overlapping orthologous marker gene (OMG) and Fisher’s exact test to identify clusters with significant shared OMGs, helping identify cell type for a query sample. b The bar chart shows the number of tissues, cell types, and cells across 15 species. The x-axis lists the species. The y-axis on the left side of the plot represents the number of tissues and cell types, ranging from 0 to 80. The y-axis on the right side represents the number of cells, with values scaling up to 400k. Each plant has three bars colored in red, purple, and blue, representing the number of tissues, cell types, and cells respectively. The exact number of tissues, cell types, and cells for each species is displayed at the top of each column.

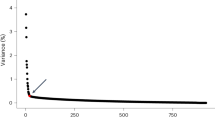

An R package is provided in GitHub such that experienced users can use different parameters (N, M) and other ways to assign orthologous gene groups. Using the same N in different clusters ensures the statistical results are comparable between cell clusters. The choice of N equals 200 in this analysis resulted in sufficient overlapping OMGs between clusters across species while preserving marker gene specificity. Using N smaller than 200 leads to a rapid decrease of overlapping markers across diverse species (Supplementary Fig. 2a), while using N larger than 200 leads to low specificity (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Using OrthoFinder allows the generation of ortho groups with only 15 selected species, and reasons for not using other methods are included in the discussion section.

Evaluating the OMG method for identifying cell types in plants

To validate the performance of our OMG method, we first used this method between two dicots using single-cell data from Arabidopsis1 and tomato roots5. We chose tomato because several promoter-GFP lines are available for this species, which provide a gold-standard validation for cell-type identity5; such a resource is not available for most other plants. We performed the OMG test on 165 pairs of clusters (15 clusters in tomato x 11 clusters in Arabidopsis, Fig. 2a and Supplementary Data 2). Without providing the published cell-type identity from tomato, our analysis found 24 pairs of clusters (Fig. 2a, red boxes) with significant numbers of shared OMGs between two species (FDR < 0.01). Furthermore, the published annotations (Fig. 2a, labels on the right) of the 12 clusters in tomato exactly match the corresponding Arabidopsis clusters (Fig. 2a, green labels on the right). The cortex cluster in tomato is a partial match (yellow) because it shared significant OMGs with both cortex and nonhair cells. There are two exodermis clusters, which is a cell type not found in Arabidopsis (blue). We found that the exodermis clusters in tomato have significant overlapping OMGs with endodermis clusters in Arabidopsis. Both endodermis in Arabidopsis and exodermis in tomato contain suberized barriers in their cell walls22, which could explain the commonality between these two cell clusters. In summary, all clusters in the tomato root data showed exact, partial, or functional matches with corresponding Arabidopsis clusters using the OMG method, and genes from OMG groups showed high cell type specificity (Supplementary Fig. 3).

a Using Arabidopsis OMGs to predict tomato root cell types. Each box displays the number of conserved OMGs between the two cell types being compared. The red highlighted boxes indicate FDR-adjusted p < 0.01 based on the Fisher’s exact upper-tailed test. Labels on the right indicate the cell type labels based on published annotation. b UMAP of 15 default tomato root clusters. Specifically, we merge all the meristematic zones (clusters 4, 6, 8, 10, in a) into a single cluster (cluster MZ). Similarly, we have recreated the cortex, hair, and non-hair clusters based on the original assignment in the published study. c Pairwise comparison of cell clusters from rice and Arabidopsis, with the number in each cell reflecting common OMGs between clusters, darker colors indicate more OMGs and red boxes highlight significant overlapping (adjust p value < 0.01). The 9 matched clusters are marked by a black star (*). The putative meristematic clusters are marked by two red stars (**). The heatmap demonstrates the OMG method’s specificity: for instance, the Arabidopsis xylem cluster shares 43, 15, and 24 OMGs with rice’s xylem, cortex, and stele clusters respectively, but only the xylem-to-xylem comparison shows significant overlap by the Fisher’s exact upper-tailed test. d The heatmap shows prediction of tomato shoot clusters (y-axis) using Arabidopsis shoot OMGs (x-axis). Numbers in each cell represent shared OMGs between clusters. Red boxes indicate significant sharing between Arabidopsis and tomato clusters, tested by the Fisher’s exact test. Published tomato cell-type labels are shown on the right (0–14). The match between predicted and published labels is indicated by green boxes (full match), yellow boxes (partial match), and gray boxes (non-significant by statistical test).

To further test the accuracy of our method, we performed OMG test between a dicot (Arabidopsis) and a monocot (rice). We used single-cell data from Arabidopsis1 and rice2 roots where 11 and 10 clusters in each species have corresponding cell types in the counterpart species. We identified significant similarities between 8 pairs of cell clusters using one-to-one orthologous genes (Supplementary Fig. 4a), and 14 pairs using the OMG method (FDR < 0.01, Fig. 2c, Supplementary Data 3). When mapping cell clusters with one-to-one orthologous genes, only three out of eight pairs are from orthologous cell types (Supplementary Fig. 4a). In contrast, the OMG method identified 13 out of 14 cluster pairs between Arabidopsis and rice from orthologous cell types, among which, 9 pairs were from exact or partial matches.

There are four mismatched clusters located in the connecting region of multiple clusters on the Arabidopsis and rice UMAPs (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b), suggesting these clusters are made of undifferentiated cells as compared to other clusters. To test this hypothesis, we performed an OMG test using a 15-species reference map (Fig. S4b). These four clusters showed significant similarities with meristematic cells from tomato, cassava roots23, wild strawberry (Fragaria vesca)24, field mustard (Brassica rapa)25, and Madagascar periwinkle (Catharanthus roseus) leaves26. Furthermore, using the Gene Ontology (GO) functional enrichment analysis27, these four clusters from rice and Arabidopsis are enriched with similar GO categories, such as ribosomal genes, which are a hallmark of meristematic cell identities (Supplementary Fig. 4c and Supplementary Data 3). Notably, non-hair cluster 1 and cluster 2 in Arabidopsis have distinct GO enrichment, whereas non-hair cluster 2 and stele cluster 1 in Arabidopsis have almost identical GO enrichment as those found in meristem and endodermis clusters in rice data (Supplementary Fig. 4c). These results suggest that these clusters are better labeled as meristematic cells. With this re-labeling, the OMG method correctly assigned 13 out of 14 cluster pairs between rice and Arabidopsis, significantly improving cell type identification and mapping precision between the distantly related monocot and dicot species, which diverged ~150 million years ago.

Our analyses of these pairs of species also demonstrated that cell type assignment cannot rely on a small number of manually curated orthologous genes, without a statistical test that considers the number of overlapping markers in other clusters. These pair-wise comparisons showed that most cluster pairs shared more than 10 ortho-gene groups in top 200 OMGs between cell types in roots (Fig. 2a and c). As one example, when comparing the OMGs between each of the 10 rice clusters to Arabidopsis xylem cell cluster, the xylem cell cluster in rice has 43 OMGs shared with the xylem cluster in Arabidopsis (Fig. 2c, column 1). However, other clusters in rice also shares a substantial number of OMGs with the xylem cell cluster in Arabidopsis. For example, the cortex and stele clusters in rice shared 15 and 24 OMGs with the xylem cluster in Arabidopsis. In the first case (cortex vs xylem), only relying on the 15 shared marker genes between these two clusters, without performing a statistical test across all other cell cluster pairs, could lead to an incorrect assignment of the rice cortex cluster as a putative xylem cluster. In the second case (stele vs xylem), because xylem is considered part of the stele, the overlaps between xylem and stele is expected because highly expressed genes in xylem could also be found highly expressed in stele. Our method allows ranking of cluster identity based on relative enrichment; in this case, indicating higher overlap of the xylem cluster in Arabidopsis with the xylem cluster in rice as compared to the stele cluster in rice. In summary, it is important to compare each cluster from a query species to all other cell clusters in a reference map, as done in the OMG method, to ensure the specificity of cell identity assignment.

To further demonstrate the general applicability of this method, we applied this method to single-cell data of roots and shoot apical meristems from rice2, maize3, poplar28, tomato6, and Arabidopsis4. For example, when testing our method on shoot apical meristem tissues between Arabidopsis and tomato, eleven out of fifteen clusters showed an exact or partial match in their identity with significant overlap in OMGs (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Data 2). This concordance of cell types based on OMGs was found between all other pairwise comparisons performed in roots, as well as in shoot apical meristems (Supplementary Fig. 6). These results demonstrate that by using OMGs between different plant species, cell types can be assigned for a majority of cell clusters regardless of the tissue type.

Revealing the broad conservation of cell type marker genes in plants by the OMG method

To demonstrate the scalability of our approach and to understand the conservation and divergence of cell types across a variety of plants, we performed pairwise comparison of OMGs for 15 species29 across monocots and dicots (Supplementary Fig. 7a, b), including Arabidopsis1,4,9,12,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44, field mustard25, Madagascar periwinkle26, wild strawberry24, soybean45, cotton (Gossypium bickii46 and Gossypium hirsutum47,48), cassava23, barrel clover (Medicago truncatula)49, coyote tobacco (Nicotiana attenuata50), rice12,51,52,53, Populus (alba var pyramidalis, and alba x populus glandulosa)28,54, tomato, and maize3,11,55,56,57,58,59 (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Data 4). This dataset comprises 268 cell clusters, ~1 million cells, and 53,600 marker genes, which were obtained from multiple sources (Fig. 1b). This large-scale analysis across 15 species has not been reported in plants nor in any other multi-cellular organisms before.

a Pairwise comparison of cell clusters across 15 species based on the shared OMGs. The color scale represents the negative logarithm of the FDR-adjusted p value. Odd Ratios (OR) represent the likelihood of a particular cell type appearing in a specified group relative to its presence in all other groups. Proportion indicates the frequency of the predominant cell type within each group. Groups are named according to the most prevalent cell type, as indicated by their respective OR and proportion values. b, c, d Cell type-specific clustering (phloem, xylem, and cortex) across 15 species.

Based on smaller-scale analyses in non-plant species, one outcome of such mapping would be grouping similar cell types into clusters, neglecting any overriding effects of species dominance. Alternatively, if species-specific effects are significant, cell types from the same species will form species-specific groups. A prior study of mammalian systems demonstrated that gene expression levels group samples by organs whereas in insects, isoform expression levels group samples by species of origin, suggesting a strong species-specific effect on splicing60,61. These prior reports suggest both scenarios have been observed in the regulation of cell type-specific gene expression in other multi-cellular organisms.

Interestingly, our analysis identified 15 cell type groups and 14 of these can be named based on the dominant cell types present within each group as determined by odds ratio (OR range between 4.3 to 1560, Fig. 3a). We observed that all these 14 groups are clustered based on the cell type, tissue type or cell cycle phase, not the species. For example, G2M cells from leaf, inflorescence, and shoot apex in different species formed a single cluster. Similarly, the mesophyll cell type is conserved across leaf, shoot apex, and inflorescence in different plant species. Functionally relevant clusters are also closely related in this map, for example, cells from G2M and S phases formed two smaller clusters which are two sub-clusters within a large cluster (Fig. 3a). Detailed annotations of each sub-cluster can be found in Supplementary Fig. 8. Only cluster that showed strong species effect is cluster 15 (Mix), which contains two monocot and two dicot sub-clusters, consisting of cells from various non-homologous tissues.

When focused on each cell type, the OMG method revealed intriguing cell type-specific conservation and divergence. For example, both phloem and xylem are vascular tissues, however, these two cell types demonstrated different marker conservation between root and shoot tissues. The phloem cluster consists of two sub-clusters, phloem cells and phloem parenchyma/pericycle cells. For phloem cells, there are no separate clusters for leaf phloem or root phloem (Fig. 3b). In contrast, xylem has a distinct pattern between root and non-root tissues (Fig. 3c), with one sub-cluster consisting of mainly root xylem cells while other sub-cluster consisted of a mixture of xylem cells from different tissue types. A similar example is seen in the epidermal cells, where the epidermis in root tissues displays a different pattern compared to non-root tissues. The root epidermis and non-root epidermis form two distinguished groups (Supplementary Fig. 8). This observation could suggest that root hair cells consisted of similar regulatory program across species whereas non-hair cells harbor species-specific regulation.

Some cell types showed divergence between monocots and dicots, for example, the cortex cluster include four sub-clusters, with one from monocots and three from dicots (Fig. 3d). In contrast, in the exodermis cluster, we observed a notable similarity between endodermis in Arabidopsis and exodermis in maize, rice, and tomato, supporting the functional similarity between these cell types as we observed between tomato and Arabidopsis (Fig. 2a).

Overall, the OMG method offers a robust methodology to map cell types across plant species and reveal tissue-specific patterns. Finally, to understand how the number of common OMGs between two species changes over an evolutionary distance, we found a statistically significant (p < 0.05) decrease in common OMGs with increasing evolutionary distance (Supplementary Fig. 9a). However, including species-specific cell types such as cells from soybean nodules eliminate this trend (Supplementary Fig. 9b).

Verifying functional conservation of cell identity markers from conserved orthologous marker groups across plant species via GO enrichment analysis

To verify whether similar cell types across plant species share functions, we performed GO enrichment analysis on the top 200 marker genes for clusters across species in each cell type group. We analyzed 13 cell type groups: G2M phase, S phase, Meristem, Root pericycle, Mesophyll, Epidermis, Cortex, Root hair, Phloem/Companion cell, Exodermis/Endodermis, Xylem, Vascular, and Vascular1. Two groups, Pistil/Inflorescence and Mix were excluded due to insufficient marker genes and unclear identity. The functions of genes in each group were summarized using a bag-of-words model to highlight key functions for each cell type. For example, G2M phase involves microtubule formation and spindle assembly; S phase is enriched with nucleosome assembly and chromatin remodeling, functions related to DNA replication. Meristem functions are associated with ribosome biogenesis, and mesophyll functions are related to photosynthesis. Epidermis functions include lipid binding, lipid transport, and acyltransferase activity, while Xylem functions are associated with secondary cell wall formation (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 10, and Supplementary Data 5). This analysis demonstrates that our cell clustering and marker gene identification have biological relevance and, in particular, that the uniquely expressed marker genes highlight functions explicitly associated with individual cell types.

The dot plot illustrates the significance and enrichment levels of GO terms across 13 cell identities from the heatmap in Fig. 3a. The x-axis represents different cell types, while the y-axis displays GO terms summarized using the bag of words method for interpretation and visualization. The size of each dot indicates the number of genes associated with a particular GO term, with larger dots representing more genes. The color of the dots reflects the significance of the enrichment, using a gradient color scale to denote varying p values within a range of 0–0.5.

Discussion

The OMG framework is a straightforward and effective marker-based method to attribute cell type identities across multiple plant species using single-cell reference maps, eliminating the need for significant computational resources typical of integration methods. This method is also inherently explainable because the lists of overlapping marker genes can be further examined to study their biological relevance.

However, this method has limitations, including the challenge of selecting the number of clusters, as different choices can result in varying markers. Since the cell clusters were generated using an unsupervised method, the cluster numbers can be adjusted. For example, the published UMAP of tomato root cells merged some clusters into bigger clusters of the same cell type (Fig. 2b). To further explore the effect of different cluster numbers, we first adjusted the Seurat20 parameter to generate 30 clusters from the tomato dataset (Supplementary Fig. 12a, b). We found that 20 out of 30 clusters are exact matches with the Arabidopsis clusters. An exodermis cluster splits into three clusters with two matches to endodermis and one match to cortex. We also found four clusters without significant matches. This result shows that increasing query cluster numbers maintains a majority of significant overlaps, but also leads to smaller clusters that do not show exact matches to any Arabidopsis clusters, which is due to an insufficient number of marker genes to accurately ascribe cell types. Second, we used the cluster assignment provided by the original publication (Supplementary Fig. 12c and Supplementary Data 2). This resulting heatmap also showed high concordance between the cluster annotations in the two species. The same analysis was performed between rice root and tomato root data. As expected for these two distantly related species, we found fewer significant overlapping OMGs, however, the majority of significant similar clusters are from the same cell type in two species (Supplementary Fig. 12d) based on OMG method.

Besides that, the analysis in this study was conducted using published datasets, where inconsistent cell-type labeling in the reference datasets can cause mismatches or inaccurate cell-type labeling in the query dataset. Additionally, insufficient data to characterize cell type-specific decay of overlapping OMGs leads to failures in accurately annotating cell types. These limitations can be further mitigated with community-based agreement on meta-data publication standards62 such that it is easier to reproduce the published clusters, extract marker genes automatically, and enable faster cross-species comparison in many species.

Moreover, this method is constrained to identify the conserved OMGs in more than two species in monocots and dicots. Using root single-cell data from rice2, maize3, and Arabidopsis1 as our models to define common OMGs, we found that only five cell types contain common OMGs, and for these, only a few OMGs are shared among all three species (Supplementary Fig. 13a). To tackle this scarcity of common OMGs, we considered increasing the marker gene pool (i.e., N > 200) but found that this carries a trade-off of lower marker specificity (Supplementary Fig. S2a, b). Aiming to bolster the number of markers without sacrificing the specificity, we employed two machine learning methods (SHAP-RF and SVM). We found a high level of agreement between the ML-derived markers, and fewer markers were shared between the ML methods and the Seurat method (Supplementary Fig. S13b). With ML-derived markers, we found six more OMGs for xylem, one additional OMG for each of the hair/non-hair clusters in three species, and new OMGs between stele clusters (Supplementary Fig. S13c). These results suggest using different methods to identify cluster marker genes could lead to a few new markers. However, it also highlights the substantial reduction of conserved marker genes in certain cell types when trying to find them across more than two species, regardless of the methods used to identify these markers.

Given the reduction in conserved marker genes, the flexibility of the OMG pipeline is important. The first step of the OMG pipeline introduces methods such as the rank sum test default function from the Seurat package, SHAP-RF, and SVM, to identify marker genes. However, the pipeline is flexible and can accommodate any feature detection methods.

Following the initial marker identification, the second step involves using OrthoFinder to identify orthologous groups. The OMG method is also compatible with other ortholog detection methods such as BLAST63, OMA64, OrthoMCL65, and OrthoDB66. Each method has its strengths and limitations, but OrthoFinder was chosen for its flexibility and technical convenience.

An additional limitation in studying cell type functions of less well-studied species is the lack of available data in databases. GO assignment functions for genes were retrieved from Ensembl Plants, with sufficient data available for seven species: Arabidopsis, Maize, Rice, Tomato, Field mustard, Soybean, and Tobacco. Medicago was excluded from the GO analysis due to discrepancies between gene names in the database and marker genes. To ensure consistency in GO term assignments across species, we exclusively used data from the Ensembl Plants database. Different databases might use varying criteria or methodologies for annotation, leading to potential mismatches in functional profiles. Even with this restriction, we identified an unexpected result where GO term functions in maize were completely different from those in other species when compared in the same cell type (Supplementary Fig. 11).

In the future, we will continue to enhance the applicability of the OMG method to a wider range of plant species, as well as a broader range of tissues and developmental stages. This effort will provide more comprehensive insights into plant cell type diversity and improve the quality and comprehensiveness of single-cell reference maps. Additionally, we will develop strategies to account for species-specific biases in gene expression and marker specificity to improve the accuracy of cross-species cell type assignments. We also aim to establish community-based standards for metadata publication and orthologous gene group identification to facilitate more consistent and reproducible analyses across studies. By addressing these future directions, the OMG method can become a more versatile and powerful tool for plant biology research, enabling new discoveries and applications in understanding plant growth, development, and adaptation.

Methods

Cell type assignment for published scRNA-seq datasets

For Fig. 1, gene expression data from Arabidopsis thaliana, Zea mays, and Oryza sativa were re-analyzed. Parameters for the re-analysis were selected to reproduce UMAP plots that best resemble those in the published results. The data consisted of 7522 Arabidopsis cells, 14,733 Zea mays cells, and 27,426 Oryza sativa cells, which were published by Ryu et al., Ortiz-Ramírez et al., and Zhang et al., respectively (GSE123013, GSE172302, PRJNA706435). To process the gene expression matrix, a standard workflow that included the NormalizeData, FindVariableFeatures, and ScaleData functions, was used with default parameters in the Seurat package (version 4.1.1). Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to reduce the high-dimensional data into 30, 15, and 32 principal components (PCs) for Arabidopsis, maize, and rice, respectively. The FindCluster function with resolutions of 0.5, 0.55, and 0.4 was applied to these PCs using the Louvain algorithm to identify the clusters, and the uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) method was used to visualize all cells in two dimensions. Finally, lists of known marker genes from these published papers were used to label all the cell clusters. If a cluster did not include any marker genes from the publication, the cluster is labeled as unknown. The cell-type assignment scripts can be found in our GitHub repository.

Integration of three plant species datasets together

To integrate scRNA-seq datasets from Arabidopsis, maize, and rice, the Seurat integration pipeline was used. First, genes from each species were converted into orthologous gene IDs, and 5000 high variable genes were identified and ranked from 1 to 5000 using the FindVariableFeatures function and nfeature = 5000. Since one orthologous gene can consist of one or more species of genes, ranking the list of high-variable genes supported the selection of the top genes in each orthologous group for integration. Second, top 2000 (out of 5000) unique high-variable orthologous genes corresponding to the top high-variable genes for each species were selected to ensure that the most informative genes were used in the integration process. To ensure the quality of each dataset, the merged Seurat object of three datasets was split into its individual components, and each was independently normalized and scaled using the SCTransform method. The SelectIntegrationFeatures function was then used to identify the top informative features for integrating multiple datasets, and the PreSCTIntegration function was employed to ensure that the Pearson residuals for the selected features were present in each Seurat object. To integrate the three datasets, the FindIntegrationAnchors function was used to identify a set of anchors between all Seurat objects in the list, and these anchors were then used to integrate the three objects together with IntegrateData. Finally, the standard workflow for processing scRNA-seq data was applied, including RunPCA, RunUMAP, FindNeighbors, and FindClusters. The clustering was performed using 30 dimensions and a resolution of 0.3. This analysis produced an integrated UMAP for Arabidopsis, rice, and maize.

The integrated metadata was annotated based on the cell-type annotation obtained from the original analyses where each species was analyzed separately. This step avoided the potential overfitting in the integration process that could lead to loss of biologically important variations across species. To investigate whether the number of homogenous clusters would increase, the resolution parameter of FindClusters was modified to 0.9, resulting in the number of clusters being increased to 30. In addition, to examine the potential impact of heterogenous clusters caused by different integration methods, the harmony integration was employed by applying the RunHarmony function after conducting PCA.

Marker gene identification by differential gene expression analysis

The FindAllMarkers function in the Seurat package was used to detect marker genes in species-specific UMAPs. A default differential expression test of expression level in a single cell type versus the expression in all other cell types was performed based on the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. To detect marker genes, we included only.pos = TRUE, which selects only positive log-fold changes, min.pct = 0.3, which sets a minimum percentage of cells that express the gene, and logfc.threshold = 0.45, which sets the threshold for log-fold change to select significant genes. After running the FindAllMarkers function, the list of differentially expressed genes was sorted based on their log-fold change values, and the top 200 most significant marker genes were selected for each cluster.

Marker gene identification by SHAP and SVM methods

We used the SPMarker Python package to identify marker genes in our Arabidopsis, rice, maize, and tomato datasets. The SPMarker package employed two feature selection techniques, namely Shapley additive explanations (SHAP) based on random forest and support vector machine, to develop a pipeline for calculating the contribution of each gene on the cell type assignment model. This approach allowed us to handle imbalanced data caused by major and minor clusters in scRNA-seq data and identify unique marker genes in each cell type cluster. To generate the cell type and gene expression matrix files, a custom R script was used with Seurat’s FindVariableFeatures function to select 5000 high-variable genes and the SCTransform function to normalize the selected dataset. Using the SHAP value and SVM coefficients, cell type-specific markers were identified in the species-specific UMAPs. Similar to the default Seurat method, the top 200 most significant marker genes were selected for each cluster.

Identification of conserved orthologous marker genes and analysis of the conserved orthologous marker genes between two species

OrthoFinder software (v2.5.4) was used to search homologous genes and cluster these genes into ortho-groups. Protein sequences in FASTA format for each species were downloaded from the Ensembl plants database and used as input for the OrthoFinder analysis. Species-specific marker gene names were mapped to the ortho-group name and these ortho-groups are named Orthologous Marker gene Groups (OMGs). These OMGs were used in downstream analyses, in place of the original marker genes, to enable comparison between species.

After obtaining lists of orthologous marker genes for all cell types in each of the species, the number of common orthologous marker genes between any two species was calculated. To evaluate the significance of the conserved marker gene list, Fisher’s exact independent tests were performed, hypothesizing that the orthologous marker gene list for each cell-type cluster from one species was independent of those from another species. Fisher’s exact test is a statistical method used to analyze the association between two categorical variables, and in this case, it was used to determine the significance of the overlap in marker genes between species. The p value from the Fisher test could provide evidence to evaluate the significance of the conserved marker gene list. The p value is obtained through the R code:

df[i,j] is a matrix where i \(\in\) (1, M) where M is the number of clusters in species 1, and j \(\in\) (1, N) where N is the number of clusters in species 2.

To address the issue of multiple testing, we applied an FDR correction to the p values obtained from the Fisher exact test. A threshold of 0.01 was then set on the q-value to determine which tests were significant.

Conservation of OMG across 15 plant species

We employed a hierarchical clustering approach based on Fisher’s exact test p values to generate a heatmap. The heatmap represents an analysis of a 268 species-specific cell clusters, ~1 million cells, and over 53,600 marker genes. We began by identifying the number of commons OMG between cell-type clusters of two species. Data sources for the 15 species can be found in Supplementary Data 6. We then evaluated the significance of the conservation using Fisher’s exact tests, adjusting p values for FDR to correct for multiple testing. We applied negative log transformation to these p values at various thresholds for better visual differentiation of significance levels. The complete method of hierarchical clustering was applied to define clusters and sub-clusters within the data. The final heatmap was generated by the pheatmap R function with color-coded to enhance interpretability. Heatmap was generated using the -log10 FDR adjusted p value rounded to the following thresholds 50, 30, 20, 10, 5, 3, 2 for better visualization.

Odds ratio (OR) to name cell type groups that map cell types across 15 species

The odds ratio (OR) is a measure indicating the likelihood of a certain cell type across different species clustering together as shown by a heatmap’s color bar, versus scattering among different groups. It is calculated as the ratio of the odds of that cell type appearing in one specific group compared to its odds across all other groups. An OR greater than 1 suggests that the cell type is clustered into a particular group, justifying its use as a label for that group in the heatmap.

The correlation between phylogenetic distance and shared OMGs between Arabidopsis and other plant species

To investigate this relationship, we processed the phylogenetic tree obtained from OrthoFinder using the Tree class in the ete3 Python module. We normalized the evolutionary distances of each species to Arabidopsis on a scale from 0 to 1, with lower values denoting a closer evolutionary relationship with Arabidopsis and higher values indicating greater divergence. To visualize the relationship between the shared OMGs and the phylogenetic distance, we applied the ggplot2 package in R to generate a line plot and performed linear regression analysis.

GO enrichment analysis for Arabidopsis and rice marker genes

To identify GO terms in our marker gene lists, we performed GO enrichment analysis using the R package such as clusterProfiler, AnnotationDbi, and AnnotationHub, along with org.At.tair.db for Arabidopsis annotation. We analyzed marker genes associated with Arabidopsis’s nonhair and stele. The compareCluster function implemented the enrichment analysis, using a p value cutoff of 0.01 and adjusted p value using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. The results were visualized through the dotplot, which depicted the gene count by dot size and significance by color. For rice, we accessed the genome annotation via AnnottaionHub and used biomart to ensure only genes with valid Entrez IDs were included. The enrichment analysis for rice followed the same parameters as for Arabidopsis.

GO enrichment analysis to identify shared functions across plant species

We used biomaRt_2.60.1 to fetch data from Ensembl Plants and clusterProfiler_4.12.0 to perform enrichment analysis and visualize the functional profiles of genes. Among the 15 species mentioned, we found data for Arabidopsis (athaliana_eg_gene), maize (zmays_eg_gene), rice (osativa_eg_gene), tomato (slycopersicum_eg_gene), field mustard (brapa_eg_gene), soybean (gmax_eg_gene), and tobacco (nattenuat_eg_gene).

We analyzed gene functions in 13 out of 15 groups from the heatmap in Fig. 4a, excluding the Pistil/Inflorescent tissue and Mix groups due to an insufficient number of marker genes. To verify whether similar cell types across species share the same functions, we compared the functions of the top 200 marker genes in all clusters within each cell type group. We displayed GO terms shared by more than half of the clusters in each group with a p value below 0.05. Since the order of cell types analyzed followed the order in Fig. 4a, GO terms appear only once in the joint analysis plot. Consequently, later-appearing cell-type groups might have fewer shared GO terms compared to earlier clusters, as their shared GO terms could appear in the early clusters. This is evident from some GO terms being shared across multiple cell type groups. A bag of words model was employed from the website Worditout to highlight key functions for each cell type group to enhance interpretation of shared gene functions.

OMG browser

To facilitate the use of this method by the broad research community, we have launched a user-friendly web-based tool called the OMG browser, which enables effortless identification of cell types or perform pairwise comparison across monocot and dicot. For input preparation, the Seurat package’s FindAllMarker function or alternative methods can be utilized to determine marker genes. Inputs should be formatted as a data frame with three columns specifying gene names, cluster names, and gene expression levels. For guidance on generating this input, please refer to our instructional video at https://youtu.be/oliRmER1rXw. When the marker gene table is uploaded, the browser allows users to conduct pairwise comparisons with our reference data, incorporating a statistical test to highlight significant findings. If the users’ data have not been previously labeled, our browser can assist in labeling through comparison and statistical validation. A detailed tutorial video is available to walk users through the process, which can be found at https://youtu.be/Jb4uMq394Sg.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The orthologous marker genes data generated in this study are provided in the Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The scripts for the analysis can be found at our GitHub repository (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14353406) and shinyR website for visual comparisons (http://orthomarkergenes.org).

References

Ryu, K. H., Huang, L., Kang, H. M. & Schiefelbein, J. Single-cell RNA sequencing resolves molecular relationships among individual plant cells. Plant Physiol. 179, 1444–1456 (2019).

Zhang, T. Q., Chen, Y., Liu, Y., Lin, W. H. & Wang, J. W. Single-cell transcriptome atlas and chromatin accessibility landscape reveal differentiation trajectories in the rice root. Nat. Commun. 12, 2053 (2021).

Ortiz-Ramírez, C. et al. Ground tissue circuitry regulates organ complexity in maize and Setaria. Science (1979) 374, 1247–1252 (2021).

Zhang, T. Q., Chen, Y. & Wang, J. W. A single-cell analysis of the Arabidopsis vegetative shoot apex. Dev. Cell 56, 1056–1074.e8 (2021).

Cantó-Pastor, A. et al. A suberized exodermis is required for tomato drought tolerance. Nat. Plants 10, 118–130 (2024).

Tian, C., Du, Q., Xu, M., Du, F. & Jiao, Y. Single-nucleus RNA-seq resolves spatiotemporal developmental trajectories in the tomato shoot apex. bioRxiv 2020.09.20.305029 https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.20.305029 (2020).

Chen, H. et al. PlantscRNAdb: a database for plant single-cell RNA analysis. Mol. Plant 14, 855–857 (2021).

Yan, H. et al. Identification of new marker genes from plant single-cell RNA-seq data using interpretable machine learning methods. N. Phytol. 234, 1507–1520 (2022).

Shahan, R. et al. A single-cell Arabidopsis root atlas reveals developmental trajectories in wild-type and cell identity mutants. Dev. Cell 57, 543–560.e9 (2022).

Ryu, K. H., Zhu, Y. & Schiefelbein, J. Plant cell identity in the era of single-cell transcriptomics. Annu. Rev. Genet. 55, 479–496 (2021).

Marand, A. P., Chen, Z., Gallavotti, A. & Schmitz, R. J. A cis-regulatory atlas in maize at single-cell resolution. Cell 184, 3041–3055.e21 (2021).

Liu, Q. et al. Transcriptional landscape of rice roots at the single-cell resolution. Mol. Plant 14, 384–394 (2021).

Guillotin, B. et al. A pan-grass transcriptome reveals patterns of cellular divergence in crops. Nature 617, 785–791. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06053-0 (2023).

Luecken, M. D. et al. Benchmarking atlas-level data integration in single-cell genomics. Nat. Methods 19, 41–50 (2022).

Tarashansky, A. J. et al. Mapping single-cell atlases throughout Metazoa unravels cell type evolution. Elife 10, e66747 (2021).

Passalacqua, M. J. & Gillis, J. Coexpression enhances cross-species integration of single-cell RNA sequencing across diverse plant species. Nat Plants 10, 1075–1080 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-024-01738-4 (2024).

Ianevski, A., Giri, A. K. & Aittokallio, T. Fully-automated and ultra-fast cell-type identification using specific marker combinations from single-cell transcriptomic data. Nat. Commun. 13, 1246 (2022).

Quan, F. et al. Annotation of cell types (ACT): a convenient web server for cell type annotation. Genome Med. 15, 91 (2023).

Butler, A., Hoffman, P., Smibert, P., Papalexi, E. & Satija, R. Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 411–420 (2018).

Stuart, T. et al. Comprehensive integration of single-cell data. Cell 177, 1888–1902.e21 (2019).

Emms, D. M. & Kelly, S. OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 20, 238 (2019).

Cohen, H., Fedyuk, V., Wang, C., Wu, S. & Aharoni, A. SUBERMAN regulates developmental suberization of the Arabidopsis root endodermis. Plant J. 102, 431–447 (2020).

Song, J. et al. Single-cell transcriptome sequencing atlas of cassava tuberous root. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 1053669 (2023).

Bai, Y. et al. Development of a single-cell atlas for woodland strawberry (Fragaria vesca) leaves during early Botrytis cinerea infection using single-cell RNA-seq. Hortic. Res. 9, uhab055 (2022).

Guo, X. et al. Single‐cell transcriptome reveals differentiation between adaxial and abaxial mesophyll cells in Brassica rapa. Plant Biotechnol. J. 20, 2233–2235 (2022).

Sun, S. et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing provides a high-resolution roadmap for understanding the multicellular compartmentation of specialized metabolism. Nature Plants 9, 179–190 (2023).

Reimand, J. et al. Pathway enrichment analysis and visualization of omics data using g:Profiler, GSEA, Cytoscape and EnrichmentMap. Nat. Protoc. 14, 482–517 (2019).

Conde, D. et al. Single-nuclei transcriptome analysis of the shoot apex vascular system differentiation in Populus. Development 149, dev200632 (2022).

Cao, S. et al. scPlant: a versatile framework for single-cell transcriptomic data analysis in plants. Plant Commun. 4, 100631 (2023).

Wendrich, J. R. et al. Vascular transcription factors guide plant epidermal responses to limiting phosphate conditions. Science 370, eaay4970 (2020).

Zhang, T.-Q., Xu, Z.-G., Shang, G.-D. & Wang, J.-W. A single-cell RNA sequencing profiles the developmental landscape of Arabidopsis root. Mol. Plant 12, 648–660 (2019).

Jean-Baptiste, K. et al. Dynamics of gene expression in single root cells of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 31, 993–1011 (2019).

Gala, H. P. et al. A single-cell view of the transcriptome during lateral root initiation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 33, 2197–2220 (2021).

Kim, J.-Y. et al. Distinct identities of leaf phloem cells revealed by single cell transcriptomics. Plant Cell 33, 511–530 (2021).

Tenorio Berrío, R. et al. Single-cell transcriptomics sheds light on the identity and metabolism of developing leaf cells. Plant Physiol. 188, 898–918 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Global dynamic molecular profiling of stomatal lineage cell development by single-cell RNA sequencing. Mol. Plant 13, 1178–1193 (2020).

Denyer, T. et al. Spatiotemporal developmental trajectories in the Arabidopsis root revealed using high-throughput single-cell RNA sequencing. Dev. Cell 48, 840–852.e5 (2019).

Shulse, C. N. et al. High-throughput single-cell transcriptome profiling of plant cell types. Cell Rep. 27, 2241–2247.e4 (2019).

Neumann, M. et al. A 3D gene expression atlas of the floral meristem based on spatial reconstruction of single nucleus RNA sequencing data. Nat. Commun. 13, 2838 (2022).

Zhai, N. & Xu, L. Pluripotency acquisition in the middle cell layer of callus is required for organ regeneration. Nat. Plants 7, 1453–1460 (2021).

Procko, C. et al. Leaf cell-specific and single-cell transcriptional profiling reveals a role for the palisade layer in UV light protection. Plant Cell 34, 3261–3279 (2022).

Long, Y. et al. FlsnRNA-seq: protoplasting-free full-length single-nucleus RNA profiling in plants. Genome Biol. 22, 66 (2021).

Maeda, T. et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing of arabidopsis leaf tissues identifies multiple specialized cell types: idioblast myrosin cells and potential glucosinolate-producing cells. Plant Cell Physiol. 64, 234–247 (2023).

Kao, P., Schon, M. A., Mosiolek, M., Enugutti, B. & Nodine, M. D. Gene expression variation in Arabidopsis embryos at single-nucleus resolution. Development 148, dev199589 (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. Integrated single-nucleus and spatial transcriptomics captures transitional states in soybean nodule maturation. Nat. Plants 9, 515–524 (2023).

Sun, Y. et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis reveals the developmental trajectory and transcriptional regulatory networks of pigment glands in Gossypium bickii. Mol. Plant 16, 694–708 (2023).

Qin, Y. et al. Single‐cell RNA‐seq reveals fate determination control of an individual fibre cell initiation in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). Plant Biotechnol. J. 20, 2372–2388 (2022).

Wang, D. et al. Cell-specific clock-controlled gene expression program regulates rhythmic fiber cell growth in cotton. Genome Biol. 24, 49 (2023).

Cervantes-Pérez, S. A. et al. Cell-specific pathways recruited for symbiotic nodulation in the Medicago truncatula legume. Mol. Plant 15, 1868–1888 (2022).

Kang, M., Choi, Y., Kim, H. & Kim, S. Single‐cell RNA‐sequencing of Nicotiana attenuata corolla cells reveals the biosynthetic pathway of a floral scent. N. Phytol. 234, 527–544 (2022).

Xie, Y. et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing efficiently predicts transcription factor targets in plants. Front Plant Sci. 11, (2020).

Zong, J. et al. A rice single cell transcriptomic atlas defines the developmental trajectories of rice floret and inflorescence meristems. N. Phytol. 234, 494–512 (2022).

Wang, Y., Huan, Q., Li, K. & Qian, W. Single-cell transcriptome atlas of the leaf and root of rice seedlings. J. Genet. Genome. 48, 881–898 (2021).

Chen, Y. et al. Transcriptional landscape of highly lignified poplar stems at single-cell resolution. Genome Biol. 22, 319 (2021).

Bezrutczyk, M. et al. Evidence for phloem loading via the abaxial bundle sheath cells in maize leaves. Plant Cell 33, 531–547 (2021).

Sun, G. et al. The maize single-nucleus transcriptome comprehensively describes signaling networks governing movement and development of grass stomata. Plant Cell 34,1890–1911 https://doi.org/10.1093/plcell/koac047 (2022).

Tao, S. et al. Single-cell transcriptome and network analyses unveil key transcription factors regulating mesophyll cell development in maize. Genes 13, 374 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals the landscape of maize root tips and assists in identification of cell type-specific nitrate-response genes. Crop J. 10, 1589–1600 (2022).

Satterlee, J. W. et al. A Wox3-patterning module organizes planar growth in grass leaves and ligules. Nat. Plants 9, 720–732 (2023).

Cardoso-Moreira, M. et al. Gene expression across mammalian organ development. Nature 571, 505–509 (2019).

Gibilisco, L., Zhou, Q., Mahajan, S. & Bachtrog, D. Alternative Splicing within and between Drosophila Species, Sexes, Tissues, and Developmental Stages. PLoS Genet. 12, e1006464 (2016).

Grones, C. et al. Best practices for the execution, analysis, and data storage of plant single-cell/nucleus transcriptomics. Plant Cell https://doi.org/10.1093/plcell/koae003 (2024).

Camacho, C. et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinforma. 10, 421 (2009).

Altenhoff, A. M., Schneider, A., Gonnet, G. H. & Dessimoz, C. OMA 2011: orthology inference among 1000 complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, D289–D294 (2011).

Li, L., Stoeckert, C. J. & Roos, D. S. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 13, 2178–2189 (2003).

Kuznetsov, D. et al. OrthoDB v11: annotation of orthologs in the widest sampling of organismal diversity. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D445–D451 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Plant Genome Research Program (PGRP, Grant No. 2344169), the US Department of Energy (DOE, Grant No. DE-SC0022985), and the National Science Foundation Early-concept Grants for Exploratory Research (NSF-EAGER, Grant No. 2218234).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L. developed the project and supervised its execution. T.N.C. performed the research and analyzed data. S.P.B. developed the web browser. P.R.T. and S.K. performed the data analysis. T.N.C., B.O.R.B., and S.L. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Sergio Cervantes-Pérez, and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chau, T.N., Timilsena, P.R., Bathala, S.P. et al. Orthologous marker groups reveal broad cell identity conservation across plant single-cell transcriptomes. Nat Commun 16, 201 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55755-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55755-0

This article is cited by

-

Recent progress in single-cell transcriptomic studies in plants

Plant Biotechnology Reports (2025)