Abstract

Deep learning has proven capable of automating key aspects of histopathologic analysis. However, its context-specific nature and continued reliance on large expert-annotated training datasets hinders the development of a critical mass of applications to garner widespread adoption in clinical/research workflows. Here, we present an online collaborative platform that streamlines tissue image annotation to promote the development and sharing of custom computer vision models for PHenotyping And Regional Analysis Of Histology (PHARAOH; https://www.pathologyreports.ai/). Specifically, PHARAOH uses a weakly supervised, human-in-the-loop learning framework whereby patch-level image features are leveraged to organize large swaths of tissue into morphologically-uniform clusters for batched annotation by human experts. By providing cluster-level labels on only a handful of cases, we show how custom PHARAOH models can be developed efficiently and used to guide the quantification of cellular features that correlate with molecular, pathologic and patient outcome data. Moreover, by using our PHARAOH pipeline, we showcase how correlation of cohort-level cytoarchitectural features with accompanying biological and outcome data can help systematically devise interpretable morphometric models of disease. Both the custom model design and feature extraction pipelines are amenable to crowdsourcing, positioning PHARAOH to become a fully scalable, systems-level solution for the expansion, generalization and cataloging of computational pathology applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Deep learning has the potential to help automate and objectify many manual and subjective aspects of histomorphologic analysis1. With the growing availability of digital Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E)-stained tissue Whole Slide Images (WSIs), machines can now leverage massive volumes of labeled image data to guide feature engineering in an entirely automated and data-driven manner. Despite this exciting prospect, the real-world utility and broad adoption of deep learning in pathology has been challenged by the high input requirements of expert-annotated data for each context-specific application. To solve this gap, recent approaches have explored using weakly supervised multi-instance learning to assign patch-level tissue labels using existing WSI-level clinical annotations2. While these approaches have shown that laborious manual annotations can potentially be bypassed, the continued requirement for massive data volumes to achieve good model performance (e.g. ~10,000 WSIs/application) may limit generalizability2. There is therefore a need for more practical hybrid approaches where both humans and machines contribute to learning, as these may provide a more favorable balance between automation and data efficiency. Such “human-in-the-loop” (HITL) learning paradigms3,4 may help to more efficiently produce the full diversity and scale of training data necessary to generate a comprehensive toolbox of context-specific Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), and other emerging deep learning architectures, for computational pathology.

We recently developed a computational pipeline (coined “Histomic Atlases of Variation Of Cancer” (HAVOC5)) that takes advantage of Deep Learning Feature Vectors (DLFVs), generated in a CNN’s final global pooling layer, to serve as “histomorphologic fingerprints” of individual pathology images6. By clustering associated image patches using these signatures, we found that HAVOC could segment WSIs, from a wide diversity of tissue types, into regional partitions showing relative cytoarchitectural uniformity7 (Fig. 1Ai). Importantly, we found that these proposed tissue partitions/regions correlate with expert annotations, immunohistochemical readouts and even subtle intra-tumoral differences in molecular profiles5. As such, we reasoned that this DLFV-based clustering approach could potentially serve as the foundation of a HITL weakly supervised learning approach in which a system only needs to query experts for sparse cluster-level labeling of grouped image patches for custom model training3,4.

A (i) Workflow highlighting mapping of tissue patterns across entire Whole Slide Images (WSIs). Briefly, a pre-trained Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) is used as a feature extractor and the generated Deep Learning Feature Vector (DLFV)s are used to cluster and map image patches back onto the WSI. (ii–iv) Cartoon schematic of the PHARAOH workflow. (ii) Unlabeled WSIs are uploaded to the online portal. Users receive tile-clustered maps to help decipher proposed groupings. Users provide cluster-level annotations which are aggregated across multiple WSIs and used to finetune custom CNN models. The process can be repeated to refine accuracy/desired outputs. (iii) Once developed, trained classifiers are made publicly available. In addition to tissue segmentation, various regional histomic (DLFs) and cell-based phenotyping outputs are provided to serve as biomarkers of disease (e.g. tumor infiltrating lymphocytes). (iv) In addition to core PHARAOH outputs, users can also export segmented target regions of interest and carry out custom image analyses using other third-party tools on companion platforms (CODIDO; codido.co). Panels (ii–iv) created in BioRender. Diamandis, P. (2025) https://BioRender.com/y70k830. B, C Demonstrative input (WSI) (B) and output (tissue heterogeneity map) (C) images of a sample colorectal adenocarcinoma from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). Scale bars = 2 mm. (n = 984 tiles extracted/clustered from this sample). D Representative image patches highlighting stereotypical morphology from different partitions. Tiles = 256 × 256 pixels. E, F The relative degree of histomorphology similarities/differences align with cluster positioning on dimensionality reduction plots (UMAP) (E) and Pairwise Pearson correlation coefficients (r) (F) of the partition’s DLFVs. G–I Box plots highlighting quantitative cellularity (G), epithelial (DLF66) (H), and fibrosis (DLF215) (I) marker differences between defined regions. Box plots show minimum, first quartile, median, third quartile, and maximum. Counts represent nuclear instances or overall activation per 67,488 µm2. ***p < 0.001 (2-sided t-test). J Regional cell composition differences (HoVer-Net outputs). All relevant source data including number of unique image patches (technical replicates) for each comparison group are provided as Supplementary Data files.

In this work, by combinatorially coupling these custom tissue segmentation models with a complementary set of context-agnostic cellular phenotyping readouts (e.g. cell-type classification/nuclear morphometric analysis), we present a framework for a community-driven encyclopedia of computational pathology tools for PHenotyping and Regional Analysis Of Histology (PHARAOH; https://www.pathologyreports.ai/) (Fig. 1Aii–iv). Importantly, in this work, we also highlight how PHARAOH models, designed with weak labels from a relatively small sample of images, can be used to make meaningful population-level inferences with clinical and biological significance.

Results

Image-feature clustering automates the organization of image patches into histologically-uniform batches

To automate segmentation of histological information spanning entire tissue sections, the user-friendly platform PHARAOH leverages HAVOC to divide submitted WSIs into non-overlapping image patches (~0.017–0.07 mm2; user-defined size) and uses patch-level DLFV signatures to organize tiles into a tunable number of image clusters (default k = 9)5 (Fig. 1B, C). Importantly, we found that, when tile partitions are projected back onto the original WSIs, clusters often show non-random spatial distributions that closely mirror morphologic regions of uniformity and can be easily recognized and labeled by pathologists (Fig. 1D). For each analyzed WSI, PHARAOH also provides additional visualization outputs, such as the positional relationships of clustered tiles on uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) and their pairwise DLFV Pearson correlation coefficients (r), to allow users to decipher more subtle spatial deviations in related tissue types and patterns (e.g. stromal elements in green/cyan clusters; normal epithelium in purple cluster; inflammation in orange cluster and tumor in red/yellow/blue/lime clusters) (Fig. 1E, F). Using more formal benchmarking strategies, we also show a high level of agreement between this unsupervised image segmentation workflow and manual (Dicemean = 0.93 \(\pm\) 0.04, n = 6), immunohistochemical (Dicemean = 0.82 \(\pm\) 0.1, n = 6) and transcriptionally-defined tissue boundaries (Dicemean = 0.82 \(\pm\) 0.1, n = 4) (see Supplementary Figs. 1–3).

The downstream outputs of PHARAOH can further help in objectively characterizing the delineated histological tissue regions (Fig. 1 Aiii). For example, on every submitted case, PHARAOH carries out nuclear segmentation/classification and morphometric analyses (e.g. cellularity and nuclear surface area) in a representative subset of tiles derived from each partitioned tissue region. Indeed, as highlighted in the Fig. 1 demonstrative example, cellularity counts are, as expected, significantly higher in compact lymphocyte-rich tissue regions as compared to areas containing larger neoplastic and non-neoplastic epithelial cells, as well as the more paucicellular connective tissue compartments (Fig. 1G, Supplementary Data 1A). Previously-reported individual Deep Learning Features (DLFs)6 are also standard PHARAOH outputs and closely correlate with epithelial- (DLF66), fiber- (DLF215) and mucin- (DLF382) rich regions, allowing users to have additional supporting and objective metrics of interpretability for different cluster compositions (Fig. 1H, I and Supplementary Fig. 4, Supplementary Data 2). Regional nuclear segmentation and classification using the HoVerNet-PanNuke8,9 model can also provide support and objective cross-verification for an increased relative number of epithelial (neoplastic/non-neoplastic), inflammatory and/or stromal cells within respective WSI partitions (Fig. 1J and Supplementary Data 1B). Overall, this automated framework of WSI segmentation and downstream phenotyping with interpretable features provides a dynamic approach for arranging large swaths of tissue into uniform and informative subregions across diverse tissue types.

Regional features are associated with clinical outcome and transcriptional processes in skin melanoma

To demonstrate the adaptive ability of this workflow (Fig. 2A) to streamline the development of clinically-meaningful histopathologic applications, we set out to confirm the known prognostic relationship between the levels of Tumor Infiltrating Lymphocytes (TILs), inferred from H&E images, with median overall survival time in patients with cutaneous melanoma10. To train the model, we first performed automated region delineation in a handful of WSI samples (n = 7) from the cutaneous melanoma cohort of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA-SKCM) (see Supplementary Fig. 5). On average, we found that the labeling of tissue regions delineated by the PHARAOH workflow took ~1–2 min/WSI, and generated a total of 23,211 annotated images spanning 8 unified classes (e.g. tumor and surrounding tissue types) (Supplementary Data 3). This weakly-labeled dataset was then used to fine-tune a VGG19 CNN model for automated lesion segmentation tasks. Importantly, a comparison of this melanoma model (PHARAOH model ID: e5dad8db) with additional PHARAOH-derived lesion classification models showed high spatial (Dicemean = 0.86 \(\pm\) 0.09, n = 9) and overall patch-level agreement (r = 0.79, n = 50, p < 0.0001, 2-side t-test) when compared to manual annotation and immunohistochemical ground truths (see Supplementary Figs. 1, 6 and 7). We therefore proceeded to use the cell phenotyping readouts provided by HoVer-Net/PanNuke, which are built into the standard PHARAOH workflow, to quantify immune cells in up to 200 representative tiles (from each of the remaining TCGA melanoma cases) that were classified as tumor (probability score: >90% tumor). To later highlight how the PHARAOH workflow can be leveraged to facilitate custom and collaborative applications, we also exported this representative set of target image tiles to the companion platform CODIDO, which hosts additional third party feature extractors, to generate an additional set of 160 quantitative nuclear parameters using a hosted and fully executable version of CellProfiler11 (Fig. 2A).

A Schematic of weakly supervised annotation pipeline to train Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) models for automated tumor delineation, coupled with Tumor Infiltrating Lymphocyte (TIL) inferencing and morphometric analysis. B Sample Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E)-stained Whole Slide Image (WSI) case input (top) and Class Activation Map output (bottom) of a representative case from The Cancer Genome Atlas Skin Cutaneous Melanoma (TCGA-SKCM) cohort; custom region of interest (melanoma) shown in brown; adipose and fibroconnective tissue shown in red and yellow, respectively. Scale bars = 2 mm. C Representative output of HoverNet/PanNuke for nuclear segmentation and classification; nuclei from neoplastic cells delineated in red, TILs in yellow. Tile length = 129 µm. D Sample distribution of TIL counts in 200 tiles classified as tumor and computed sample-level TIL score (mean and standard deviation shown in red) from 200 target tiles extracted from this representative case. E Scatter plot of case-level correlation between PHARAOH-based TIL quantification and RNA-based Lymphocyte infiltration signature score across TCGA-SKCM cohort. (R2 and p-value generated by simple linear fit model). F Kaplan–Meier survival curves for TCGA-SKCM cohort split into “high” (yellow) and “low” (blue) PHARAOH-TIL scores based on the overall cohort’s median value. p-value derived from 2-sided log rank test. Shaded bands show 95% confidence intervals of the variance in survival estimates (standard deviation). G Top ranked morphometric features whose values were found to predict divergent values in the Mitotic spindle program (p < 0.05, 2-sided ANOVA). H Sample case images with low, intermediate and high activations for the feature “AreaOccupied_NucleiObjects”, showing an expected increase in nuclear density. Tiles = 256 × 256 pixels. I Volcano plot highlighting significant differences in Single Sample Gene Sets Enrichment (ssGSEA) between subgroups of cases with high and low values of the morphometric feature “AreaOccupied_NucleiObjects”. Legend is shown above plot (p-value generated by 2-sided ANOVA, no FDR). J Morphometric model of interpretable features that predict melanoma with elevated mitotic spindle activity. All relevant source data for this figure are provided as Supplementary Data files. Panels (A, J) created with Biorender.com. Diamandis, P. (2025) https://BioRender.com/c69l485.

Altogether, after filtering out low-quality WSIs, we applied this tandem model to compute a sample-level TIL score for the remaining 385 patients from the TCGA-SKCM cohort, defined as the log-transformed mean value of lymphocyte counts across the set of sampled tiles classified as tumor (Fig. 2B–D, Supplementary Data 4). Molecular metadata in TCGA supported the validity of our approach, as the computed TIL score aligned with the RNA-based Lymphocyte Infiltrating Signature Score12 (linear model fit, 2-sided, R2 = 0.18, p < 0.0001, n = 385) (Fig. 2E). Moreover, partitioning the TCGA-SKCM cohort into groups of cases with either high or low TIL scores (with respect to the median score) showed significant differences in median survival (high = 109 months, low = 66 months, log rank test, 2-sided, p = 0.00016, n = 385) (Fig. 2F), which aligns with previously-reported results from RNA-based TIL inferences13 and other computer vision TIL models14. Together, this demonstrates how the annotation of image-feature-based clusters, generated from only a small handful of cases submitted to PHARAOH, can be utilized to develop custom biologically-informative histologic biomarkers of clinical outcomes without imposing significant data curation requirements on researchers.

In addition to providing examples of how PHARAOH can aid in the automation and quantification of established histomorphologic paradigms (e.g. TILs), we also leveraged specific PHARAOH outputs in exploratory analyses to show how the platform can be used to generate biological insights. Using transcriptomic data from the TCGA-SKCM cohort and the 160 morphometric features produced by CellProfiler, we ranked cases based on enrichment of genes related to mitotic spindle activity. Specifically, this was done by establishing high and low subgroups for each nuclear feature and computing differences in their average Single Sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (ssGSEA) scores from the “MSigDB_Hallmark Mitotic Spindle” gene set (Fig. 2G, Supplementary Data 5). In this analysis, the computed “AreaOccupied_NucleiObjects”, which can be interpreted as an aggregate measurement of cellular density and/or nuclear size, proved to be the most informative feature (p = 0.002, ANOVA, 2-side, no FDR) and was corroborated by histological review (Fig. 2H). Encouragingly, further analysis of the transcriptomic profiles of the high/low subgroups for the feature “AreaOccupied_NucleiObjects” revealed multiple additional cell cycle-related molecular programs as being enriched in cases with higher nuclear densities, whereas many KRAS-related gene sets (e.g. KRAS_PROSTATE_UP), which have been associated with cancer migration processes in different cancer types15, were found to be enriched in the subgroup of melanoma cases with lower nuclear densities/sizes (Fig. 2I). In addition to the conceptual value such models provide (Fig. 2J), we envision that they can be leveraged by pathologists, reviewing routine H&E slides, to guide the triaging/prioritizing of patients for advanced molecular testing to ultimately improve enrollment and uptake of precise medicine-based care.

Multivariate models of morphometric features predict aggressiveness in clear cell renal cell carcinoma

We next investigated how the aggregate use of morphometric features, extracted from tumor regions delineated by PHARAOH classifiers, could be used to develop clinically-informative models of disease. As a proof-of-concept, we investigated the degree of correlation between the grading annotations of the TCGA Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma cohort (TCGA-KIRC) with relevant nuclear morphometric features computed with CellProfiler (via CODIDO). The aforementioned weakly supervised tissue segmentation pipeline was again used to develop a tumor segmentation model for clear cell Renal Cell Carcinoma (ccRCC) with cluster-level annotations for 27 cases from the TCGA-KIRC cohort. A total of 81,768 annotated images, spanning 9 tissue classes, were generated (Supplementary Data 6 & Supplementary Fig. 8), and later used to fine-tune a custom ccRCC model (PHARAOH model ID: 82829b22). We then used this PHARAOH model to delineate lesional regions and extract a representative set of up to 200 tiles classified as tumor (probability score: >90%) from each of the remaining TCGA-KIRC cases. Then, each case’s set of tumor tiles underwent nuclear segmentation using HoVer-Net/Kumar, followed by analysis with CellProfiler (v4.0.5) to extract a set of 160 morphometric features encompassing both nucleus- and tile-level metrics (Supplementary Data 7). As an initial attempt, we developed a 3-feature aggregate score by using the average of the normalized values of the following three relevant features: (i) nuclear atypia (inverse AreaShape_FormFactor), (ii) nuclear size (AreaShape_Perimeter) and (iii) nuclear staining heterogeneity as a marker of prominent nucleoli (Intensity_MADIntensity_Grayscale) (Fig. 3A, Supplementary Data 8). Importantly, in cases where this metric could be computed, this 3-feature aggregate score showed significant alignment with the Fuhrman ccRCC grading system reported in TCGA-KIRC samples (Fig. 3B, C). To demonstrate the real-world generalizability of PHARAOH models outside of the potentially idealized cohorts of TCGA, we also applied this pipeline to a local cohort of 35 ccRCCs stratified to include cases spanning all 4 grades (Supplementary Data 9). The aggregate risk score again showed a strong relationship with tumor grade in this independent cohort (Fig. 3D, Supplementary Data 10). Lastly, partitioning the TCGA-KIRC cohort into cases with either high or low aggregate scores (with respect to the median cohort value) showed significant differences in median survival times (log-rank test, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3E).

A Schematic of the hand-crafted 3-feature model designed to capture key aspects of clear cell Renal Cell Carcinoma (ccRCC) Fuhrman grading. Created with Biorender.com. Diamandis, P. (2025) https://BioRender.com/c69l485. B Sample case input (top) and Class Activation Map (CAM) output (bottom) of a representative case from The Cancer Genome Atlas Kidney Renal Clear Cell Carcinoma (TCGA-KIRC) cohort. Custom region of interest (ccRCC) is shown in brown while normal renal parenchyma and fibroconnective tissue are shown in cyan and yellow, respectively. Scale bars = 2 mm. C, D Box plots showing aggregate nuclear feature values, separated by their pathologist-reported nuclear grades, in the TCGA-KIRC study (test set, n = 446 subjects, G1-4: 12,194,183,57 respectively) and in a local cohort (n = 35 subjects, G1-4: 8,10,9,8 respectively) (Saint Michael’s Hospital; SMH), respectively. Legend is shown between panels. E Kaplan–Meier (KM) survival curves for the TCGA-KIRC cohort split into “high” (yellow) and “low” (blue) aggregate nuclear feature score groups based on the overall cohort’s median value. F Variable importance in the XGBoost model for survival, trained with the 160 morphometric features. G, H Box plots showing predicted risk scores stratified by nuclear grade, in the TCGA-KIRC study (test dataset, n = 242 subjects, G1-4: 5,111,98,28) and in a local cohort (n = 35 subjects, G1-4: as above), respectively. Legend is shown between panels. I KM analysis for the TCGA-KIRC cohort (test dataset, n = 242 subjects) split into groups with “high” (pink) and “low” (turquoise) risk scores shows a more pronounced survival difference than the former hand-crafted model. All box plots in this figure show minimum, first quartile, median, third quartile, and maximum. p-value thresholds for box plots are denoted as follows using a 2-sided ANOVA test: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001. NS = not significant. P-values for KM survival curves represent 2-side log rank tests. Shaded bands show 95% confidence intervals of the variance in survival estimates (standard deviation). Corrections for multiple comparisons were not relevant to these analyses. All relevant source data for this figure are provided as Supplementary Data files.

To achieve a more generalizable and data-driven approach, compared to this initial manually hand-crafted model, we investigated the use of machine learning to produce more complex signatures capable of handling the entire set of extracted morphometric features. To this end, we trained an XGBoost to build a survival model using all 160 morphometric features extracted from the TCGA-KIRC cases (50/50 train/test split). This approach produces an output risk score that is analogous to hazard ratios in conventional Cox models. Inspection of the ranked feature importance from this XGBoost model highlighted distinct but encouragingly related morphometric features, underscoring the interpretability of these biologically-informed features (Fig. 3F). Importantly, the predicted risk scores again aligned with Fuhrman grade in both the TCGA-KIRC (test dataset, n = 244) (Fig. 3G, Supplementary Data 8) and in the local ccRCC (n = 35) (Fig. 3H, Supplementary Data 10) cohorts; however, the smaller size of the latter cohort limited confirmation of significant differences between the multiple group comparisons. Additionally, stratification of the remaining TCGA-KIRC cohort (unseen test dataset) into high and low risk score subgroups, based on the median cohort value, yielded an even more pronounced and significant difference in survival (log-rank test, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3I). Altogether, these results illustrate how a diversity of machine learning models can be successfully used in tandem to select regions of interest (PHARAOH), extract morphometric features (CellProfiler on CODIDO) and link them to clinical outcomes (XGBoost). The generalizability of these steps opens the door for the automated analyses of readily available H&E images to generate interpretable readouts such as risk scores across different cancer types and relevant features of interest.

Discussion

Deep learning has proven to be capable of addressing many of the challenges surrounding human subjectivity and automation in histomorphologic analyses. However, the inherent context-specific nature of developing robust models, including the required development of large, domain-specific training image datasets, has made implementation and translational efforts difficult. Building a “one-size-fits-all” solution or, conversely, innumerable “point” solutions, scattered across different online repositories, therefore present practical inefficiencies in sharing innovations in computational pathology. To address these critical scalability barriers, we developed PHARAOH to serve as a dynamic “systems-level” platform that can continually evolve through asynchronous cross-disciplinary contributions from pathologists and computer scientists. In addition to allowing translational researchers to seamlessly use advanced computational tools, PHARAOH is distinct by also empowering users to contribute unique clinical knowhow to design and share highly nuanced tools for custom applications. Like many other social platforms (e.g. Wikipedia, YouTube) this facilitates widespread access to a growing catalog of catered and personalized content. Notably, the cluster-level labels PHARAOH uses significantly reduce the time investment from expert annotators, who have demanding clinical schedules, and can be carried out entirely online without the need for any specialized hardware/software. The modular nature of PHARAOH, in combination with other complementary platforms (e.g. CODIDO), also allows computational researchers to agnostically plug-in their own innovations (e.g. mitosis detection algorithms) to explore clinical applications (e.g. using multiple PHARAOH classifiers) without the need to collaborate with scarce/busy subspecialists. Indeed, we have collectively used this pipeline to virtually catalog a diverse set of both tissue segmentation models (PHARAOH) and feature extractors (CODIDO) that were developed across several international institutions and among collaborators who have never physically met and/or have not had previous formal relationships. By enabling/promoting the sharing of developed tools, PHARAOH has the potential to develop an expansive catalog of custom models to help address the challenges of equitability, inclusiveness and diversity of machine learning tools across distinct patient populations and geographies.

In addition to automating well understood clinical paradigms, we also highlight how PHARAOH can be used to derive translational and biological insights by computationally cataloging the histomorphologic landscape of disease across different clinical (Fig. 3) and molecular variables (Fig. 2). While we show how quantitative image analysis of the TCGA-SKCM cohort can be leveraged to build computational morphometric models of rapidly cycling melanomas, this approach can be seamlessly applied to additional pathways and disease types of interest. In TCGA-KIRC, we show how the generalizable PHARAOH-CODIDO pipeline can be used to develop data-driven histomorphologic models of aggressive cancers. By mapping interpretable features (e.g. cell size, density) on routine H&E-stained sections to actionable biological parameters, we envision knowledge generated from these pipelines will augment pathologists’ ability to better prioritize specific patients for the most appropriate ancillary molecular tests and downstream clinical stratification.

As a final note, we raise some caveats to consider while using this initial iteration of PHARAOH. Firstly, while there are parameters in the image clustering workflow that perform well across a wide range of applications (e.g. tile size: 256–512, 7–9 clusters), the optimal values for specific contexts will likely differ and thus can be tuned based on specific applications and user preferences. For challenging cases, heterogeneous clusters may still persist, and can therefore be omitted and censored from downstream analyses. As each cluster generated in PHARAOH is accompanied by a proposed label and confidence score, future improvements will focus on developing more active learning approaches to mark and prioritize the most challenging cases for human review. Similarly, while we focus on using the VGG19 CNN as the backbone for fine-tuning custom models, future iterations of PHARAOH will look to expand offerings to include other CNN architectures and emerging vision transformer and foundation models16. Lastly, while we focus on surgical cancer specimens as an initial application, we note the exciting potential for the generalization of this workflow to non-neoplastic tissue types (see Supplementary Fig. 4). All together, we believe that PHARAOH represents a dynamic Wikipedia-like crowd-sourcing platform to improve the system-level reproducibility, scaling and generalization of computational pathology tools for both clinical and translational research applications.

Methods

Ethical approval

The University Health Network Research Ethics Board has approved the study REB #17-5387 as it has been found to comply with relevant research ethics guidelines, as well as the Ontario Personal Health Information Protection Act (PHIPA), 2004. Patient consent was not directly obtained and a consent waiver for this study was granted by the University Health Network Research Ethics Board as the research was deemed to involve no more than minimal risk as it included the use of exclusively existing pathology specimens. The remainder of the WSIs were obtained from various TCGA cohorts that are publicly available for research purposes, and did not require any additional institutional review board approval.

Reporting on sex and gender

There are no currently known major sex or gender differences in the diagnostic morphologic patterns of cancer as seen under a microscope. Therefore, given our primary goal of developing a crowd-sourcing pipeline for computational pathology, the focus was on validating the pipelines on well understood sex/gender-agnostic biological parameters (e.g. TILs, nuclear grades). It is therefore expected that the tools developed will therefore apply to all sexes/genders. As TCGA collected and reported the sex of each patient, future studies can apply the reported pipeline and data generated towards these questions. The age range and sex of patients in the local ccRCC cohort is also provided in Supplementary Data 10.

Image feature-based decomposition of WSIs into patch clusters with uniform histomorphology

Tissue partitions are generated in PHARAOH using an unsupervised image feature-based clustering workflow we previously coined “HAVOC” that is implemented in python (https://pypi.org/project/havoc-clustering/) and described in detail elsewhere5,7. Briefly, WSIs are first tiled into individual 0.066–0.27 mm2 image patches (patch width: 129 µm (256 pixels) to 258 µm (512 pixels)) respectively. While this parameter is entirely tunable by the user when WSIs are submitted to PHARAOH, we found that this apparent magnification effectively separates a variety of tissue types/tumor sub-patterns while providing a favorable balance between capturing both individual cellular differences (e.g. nuclear features) and more advanced secondary structures (see below for further details). Although various tile sizes were used during the initial tests, for simplicity and consistency, we have set the current default on PHARAOH to 0.066 mm2 (512 x 512 pixel, 20x apparent magnification) and 9 clusters. The results generated from this patch size maintained easily recognizable spatial patterns in tissue makeup while reducing tile-to-tile variability and not compromising the computational time of the workflow.

Histomorphologic signatures for individual tiles are represented by averaging the “deep learning feature” (DLF) values extracted from the final global average pooling layer of a previously fine-tuned version of the VGG19 CNN that we trained, with transfer learning, on a diverse set of nearly 1 million pathologist-annotated image patches spanning over 70 distinct tissue classes that were extracted from over 1000 brain tumor samples6. We refer to these 512 feature representations as the “Deep Learning Feature Vector” (DLFV). We previously showed that individual DLFs are activated by specific histomorphologic patterns (e.g. fibrosis, epithelium and mucin), allowing them to drive the clustering of image patches with relatively similar morphologies. Tile-level DLFVs are scaled feature-wise and are then hierarchically clustered into 9 clusters using Ward’s Method6. As discussed below, the total number of generated clusters can also be tuned by the user, and in conjunction with custom tile sizes, can help optimally align clustering solutions with the contextual level of tissue complexity. Empirically, this solution tends to ensure slight over-clustering of distinct (sub)regions while maximizing the production of relatively uniform histomorphological subgroups of images that are readily identifiable by expert reviewers5. To help further qualitatively and quantitatively visualize inter-cluster relationships, PHARAOH also produces tile-level UMAP projections and pair-wise Pearson correlation coefficients of each region’s average DLFVs. To include a spatial context to these image feature-based clusters, the cluster identities are also projected back onto a thumbnail of the WSI as different colors. This creates the so-called “Histomic Atlases of Variation of Cancer” (HAVOC) that we found could be easily inspected by experienced histologists/pathologists to assign accurate cluster-level labels or omit heterogenous ones in a fairly streamlined and intuitive manner.

Weakly supervised annotation and tissue-specific CNN fine-tuning

The PHARAOH workflow generates tissue-specific CNN classifiers by using expert-annotated histologically-homogeneous clusters of images as training data. Briefly, WSIs undergo deep image feature-based decomposition (via HAVOC), as described above, to form 7–12 partitions, usually comprising ~103-104 image patches per cluster (512px, 20x apparent magnification). To facilitate the annotation process, PHARAOH also provides a companion set of interpretable features at the region level. Using Mask R-CNN17,18 for nuclear segmentation and Detectron2 for morphometric analysis, the workflow calculates regional average values for cell counts, nuclear surface area and circularity. Additionally, “preliminary labels” and probability scores (e.g. Class: Fibrocollagenous tissue, Probability: 85%) from existing models are provided for each region to pre-populate commonly-found histological entities and allow users to focus their annotations on the classes that lacked high-confidence labeling. The pre-populated labels also serve as a cross-verification system to help users potentially seek additional consensus for cases where their interpretations may not match results generated from similar relevant models.

Specifically, after submitting the desired set of WSIs to be used for training to PHARAOH for analysis, users can use the “create” function from their Personal Dashboard to design and develop custom models. For each included case, users are sequentially shown a HAVOC map depicting each image cluster spatially projected back onto the original slide thumbnail. By comparing each HAVOC color map with the respective original high-quality WSI, users can choose to either keep or update the pre-populated cluster labels and effectively assign the same class label to all tiles from that specific region (“Tiles from HAVOC region”). For example, for the WSI “TCGA-D3-A8GD-06Z-00-DX1” from the “TCGA-SKCM” cohort, all 226 tiles from the blue HAVOC cluster (“TCGA-D3-A8GD-06Z-00-DX1_HAVOC_k12_blue”) were annotated with the label “lymph_dense” when developing the Melanoma (ID: e5dad8db) classifier (see Supplementary Data 3). The annotations from these multiple WSIs/HAVOC maps are then merged to create a global summary of annotations. By evaluating this summary report, users can confirm whether all the tissue classes have reached a sufficient number of annotated tiles for CNN fine-tuning and decide which classes should be included, merged or omitted from training (see Methods for further details). We also produced an instructional step-by-step video demonstrating how to develop a custom PHARAOH classifier: https://youtu.be/H9oBpH8bApc.

The annotated collection of image patches is then used to fine-tune a CNN for custom classifier generation19. During this process, the image set is filtered to remove patches with over 40% blank space, and the remaining tiles are then partitioned into training and validation sets (ratio: 85:15). The final, fully-connected layers of the VGG19 CNN are removed and replaced with a global average pooling, single fully-connected layer, and then these final two convolutional layer blocks of the network are retrained using the user-annotated images. The process is carried out using the Keras framework with a Tensorflow backend and powered by an NVIDIA RTX 3090 graphics processing unit (GPU). Users are free to iteratively retrain and refine models as they see fit.

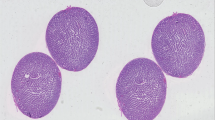

Nuclear segmentation and classification

To provide estimates of the cellular composition of tissue images, PHARAOH performs nuclear segmentation and classification using the HoVer-Net/PanNuke model (TIAToolbox implementation20), which produces counts for the following cell types: neoplastic epithelial, inflammatory, connective, necrotic and non-neoplastic epithelial. Although this model was trained with 512 x 512 pixel tiles and 40x apparent magnification, we found we could also apply this model to a WSI scanned at an apparent magnification of 20x by producing tiles of 256 × 256 pixel and scaling them to pseudo-40x magnification, 512 x 512 pixel, using bicubic pixel interpolation (‘vips resize’ command). To manage the level of utilization of computational resources, nuclear segmentation and classification is carried out on a sample of up to 200 tiles from each region of interest.

To elaborate, while the dimensions of a WSI can vary depending on the size of the sectioned tissue area, typical sections reach 150,000 (length) x 100,000 pixels (width) when scanned at a magnification of 40x. At this magnification, each pixel represents a physical length of 0.2531 microns. In addition to the need to divide these large images into smaller, more manageable and standardized image patches (tiles of 512 x 512 pixel dimensions), it is also important to correct for potential differences in the scanning resolution/magnification of the WSI. For example, many cohorts/datasets, including TCGA, contain WSIs scanned at either 40x and/or 20x. At this latter magnification, each pixel represents a physical length of 0.521 microns. If not corrected, the lower pixel density of tiles generated from 20x WSIs can make both distances and cells be computationally interpreted as much smaller than they really are. For algorithms designed to work at 40x (e.g. HoVer-Net), these apparent differences can lead to increased misclassification of larger cells (e.g. epithelial/cancer cells) as smaller cell types (e.g. lymphocytes) and distort meaningful differences in classification. Scanning resolution encoded in the metadata of each WSI was used to dictate when we generate 512 x 512 pixel (microns per pixel: 0.2531, 40x) or 256 × 256 pixel (micros per pixel: 0.521, 20x) tiles to ensure we normalize the capture area and distances of image patches.

As part of the effort to generate interpretable readouts for the regions produced by automated tissue segmentation, PHARAOH runs HoVer-Net/PanNuke in tiles sampled from all the resulting regions. In Fig. 1, we merged the non-neoplastic and neoplastic epithelial categories and omitted the necrotic class as we found that these classes had low specificity in this context.

After a tissue classification model has been established, HoVer-Net/PanNuke can be run in the tiles that have been classified as lesional with a high degree of confidence (>0.9 probability) to provide a readout of the immune status of the tumor areas. A total of 476 WSIs (.svs files) from the TCGA-SKCM study21 were downloaded from the GDC Data Portal using the GDC Data Transfer Tool Client v1.6.1. The associated clinical information was obtained from cBioportal’s dataset download section (https://www.cbioportal.org/datasets) by selecting the “TCGA, Firehose legacy” data release of the TCGA-SKCM study. We developed a training cohort of labeled image patches (256 × 256 pixel, 20x apparent magnification) using the PHARAOH workflow as described above. Specifically, we selected 7 representative WSIs containing melanoma and other commonly-encountered tissue types including normal skin, lymph nodes and intestinal mucosa. Each WSI was passed through our image feature-based clustering workflow to delineate 12 clusters of tiles per slide. Overall, we included 8 tissue classes in the final model (see Supplementary Data 3 and Supplementary Fig. 5). The annotated tiles were used to fine-tune a pre-trained VGG19 neural network. The remaining WSIs of the TCGA-SKCM were analyzed with the newly developed melanoma classifier, and a representative sample from each WSI of up to 200 tiles (bicubic pixel interpolation for 512 x 512 pixel, pseudo-40x magnification) was analyzed with the HoVer-Net/PanNuke model. Cases with only a handful of selected lesional tiles were filtered out as a quality control step prior to the formal TIL analysis. For this analysis of the TCGA-SKCM cohort, we made the assumption that the resulting inflammatory cell counts provided by the model are equivalent to TIL counts. A region-level TIL score was defined using the following formula:

In this formula, TIL score is the mean value of the log-transformed “inflammatory cell count” (ICC) of each selected tile (n = up to 200 available tiles/region) computed by HoVer-Net/PanNuke.

Nuclear segmentation and morphometric analysis in ccRCC

To investigate the level of alignment between nuclear morphometric features and pathology grading (Fuhrman grade) in ccRCC, the PHARAOH weakly supervised workflow was used to develop a ccRCC classifier with 9 tissue types using images from TCGA-KIRC (n = 27) and additional non-lesional tiles from TCGA-KIRP (n = 2) (Supplementary Data 6) (PHARAOH model ID: 82829b22). The classifier was then used to analyze the remaining WSIs from the TCGA-KIRC cohort (downloaded again from the GDC Data Portal) to delineate their tumor-containing regions, followed by sampling of up to 200 lesional tiles from each WSI. HoVer-Net/Kumar8, an image segmentation architecture trained to detect cell nuclei in histology images, was applied to each set of lesional tiles. Then, a CellProfiler pipeline was used to perform morphometric analyses that included the following image analysis modules for NucleiObjects: MeasureObjectSizeShape, MeasureImageAreaOccupied, MeasureObjectIntensity, MeasureObjectIntensityDistribution (with maximum radius set to 100), MeasureGranularity and MeasureObjectNeighbors; and the following modules for image-level analyses: MeasureTexture and MeasureImageIntensity. A total of 160 morphometric features were generated, and their values, averaged for the selected lesional tiles, were used to represent each WSI/case. A Docker image with CellProfiler was used as the base component of the workflow, to which HoVer-Net/Kumar and application-specific scripts were added (https://github.com/duanxianpi/Nuclei-Feature-Extraction). This workflow can be run either in a GPU-enabled system locally or online in PHARAOH’s companion platform CODIDO (https://www.codido.co/; “Nuclear Feature Extractor”).

A model to infer risk scores in ccRCC was trained with data from 50% of the samples from the TCGA-KIRC cohort (n = 243) using the set of 160 morphometric features, together with the survival time and status. The XGBoost for survival model was trained using the following parameters: objective = survival:cox, eval_metric = cox-nloglik, eta = 0.05, max_depth = 2, subsample = 0.85 and nrounds = 100. Inference was performed in the test dataset (n = 244) and the resulting risk scores, which are analogous to hazard ratios in Cox models, were used in subsequent analyses.

Validation of PHARAOH outside of TCGA

It is possible that the large-scale nature of the TCGA initiative could contain biases in the inclusion of cases that have definitive and particularly representative histomorphologic tumors that differ from those encountered in real-world practice. Therefore, to externally validate the robustness of the PHARAOH workflow, we scanned independent cases from local Toronto hospitals that did not participate in the TCGA study. These included relevant cases of: (i) cutaneous melanoma (3 cases generated at the Toronto General Hospital) (ii) ccRCC (35 cases generated at Saint Micheal’s Hospital (SMH)) and (iii) metastatic brain lesions (3 cases generated at the Toronto General Hospital) (total: n = 41). For all these local cases, we highlight strong concordance of partitions formed by image feature-based clusters (HAVOC) and class activation maps with manual annotations of tumors by pathologists. For the final cohort (brain metastases: lung adenocarcinoma, melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma), we also leveraged access to relevant objective IHC markers to benchmark the reliability of outputs in this independent dataset (see Supplementary Figs. 2 and 7). To validate the fidelity of generating downstream regional morphometric outputs, our local cohort of ccRCCs was stratified to include cases from all 4 Fuhrman grades (n = 35; Grade 1: 8; Grade 2: 10; Grade 3: 9; Grade 4: 8).

Strategies for managing complex tissue patterns in the PHARAOH workflow

While we have found the presented workflow to be highly generalizable to multiple tissue types and users, tissue complexity in pathology can show extreme variations that may benefit from more context-specific parameter optimization. Therefore, we describe below many built-in strategies to improve the usefulness of outputs depending on users’ judgment and preferences. Examples of how these strategies can be implemented by users during the development of classifiers is demonstrated in an accompanying instructional video (https://youtu.be/H9oBpH8bApc).

Customization and optimization of the number of HAVOC clusters and the tile sizes generated for labeling

Due to the extreme diversity of tissue heterogeneity across different specimen types, the optimal number of clusters and the optimal tile size can vary greatly across applications. We previously found that ~9 HAVOC clusters (k-value) was able to most consistently segment relevant tissue compartments across a variety of WSIs derived from different organ systems. For some simpler and/or more complex tissue sections this default k-solution (k = 9) may be suboptimal. For WSIs with relatively simple tissue compositions, generating a smaller number of partitions (k < 9) may be sufficient to capture the main variation of tissue into uniform clusters and simplify annotation. We find that solving for additional clusters in these cases often leads to the generation of redundant (but uniform) subclusters and can make interpretation/labeling more laborious. Conversely, for large and highly heterogeneous tissue, it is possible that 9 clusters is not enough and therefore that partitions may contain a mix of 2 or more distinct but somewhat morphologically-similar tissue types/patterns. In these scenarios, solving for additional clusters (k > 9) may provide more uniform groups for labeling.

While we previously attempted to solve the complexity surrounding image clustering computationally on a case-by-case basis, we found that this often led to poor and under-clustered solutions that missed critical subtleties in histomorphology that would have been consistently segmented further by histology experts. We therefore set the default number of clusters to an empirically optimized value of 9, defined in our original HAVOC study, and allow for further fine-tuning by the user each time a WSI is submitted for analysis. The size of the generated tiles for clustering can also be tuned to further optimize the uniformity of the training images for precise labeling and training. Users are also free to re-run cases to experiment with varying HAVOC tile sizes and cluster values until the optimal solution is achieved.

Censoring of problematic clusters during labeling and training

It is possible that even with multiple attempts and parameter changes, not every cluster generated in PHARAOH will represent a uniform set of images. This is most often encountered with highly complex tissue, where some HAVOC-based clusters can contain: (i) heterogeneous tiles that do not neatly belong to/are not accurately described by a specific descriptor, (ii) contain non-contributory artifacts (over-stained regions), or (iii) are comprised of legitimate patterns that are rare and unlikely to re-occur even across large cohorts (e.g. embolization material). In these circumstances, users are free to use their discretion when providing labels for these clusters for simplicity. We found that including too many or heterogeneous classes (especially when not represented by examples from multiple cases) can reduce classifier performance or lead to overfitting. In these scenarios, users can censor the problematic tile clusters from entering the training data by not providing labels (leaving textbox blank) during the annotation step. For example, the user may decide to only label 7 (out of 9) high quality clusters and exclude the remaining 2 from downstream analysis. Conversely, labeled clusters that are of high quality, but turn out to be uncommon in the annotation cohort, can also be omitted in the final training data integration step, just prior to submitting the entire cohort of labeled tiles for training.

Standardization of classification labels

To improve the standardization of class labels between classifiers, we also provide a recommended ontological schema (see Supplementary Fig. 9). For example, we recommend first organizing regions defined within cancer specimens into either neoplastic (lesional/tumor) or non-neoplastic tissue classes. In some cases, this can include a broad category such as “neoplastic tissue” or, where appropriate, can include relevant tumor sub-patterns (e.g. micropapillary vs mucinous adenocarcinoma). For non-neoplastic regions, we recommend including separate annotations for surrounding normal tissue elements (e.g. renal tubules for ccRCC) and other non-diagnostic/extraneous tissue patterns (e.g. hemorrhage, surgical gauze, necrosis). While each classifier will likely have its own nuances, we anticipate that this general scheme will help improve the standardization of classifiers across PHARAOH.

Additionally, the pre-populated labels assigned to each cluster based on existing classifiers also aim to help guide standardization across models. Lastly, while the most appropriate number of classes depends on the specific context, as with many machine learning workflows, including tissue patterns with <1000 tile-level examples, especially when derived from single cases, or with significant class imbalances, can erode the performance of the classifier. To manage this limitation, we provide users with a running tally of annotated tiles to allow sparse patterns to be omitted and/or merged with other redundant classes (see instructional video tutorial for demo).

Cross-verification of image labels and classifier performance

While human cross-verification approaches, including expert consensus, can be used at the discretion of users to improve the quality of cluster annotations, in the spirit of crowdsourcing and customization, we do not attempt to oversee or change final annotation labels provided by users. However, to improve quality control and consistency of standardized labels across different classifiers, as noted above, each image-feature-based cluster generated on PHARAOH for annotation is pre-populated with preliminary labels (and respective confidence scores) using the specific “seed” classifier used to run the initial WSI analysis. Users designing custom classifiers can therefore use these initial labels as a starting point or for cross-verification. For challenging cases, users can also re-process WSIs using multiple related PHARAOH classifiers, prior to final annotations, to understand how other user-developed models would have labeled the respective regions. Ultimately, we believe the classifier’s performance on independent cases serves as the true verification of the quantity and quality of the labeled training data (described below).

Benchmarking the segmentation performance of image feature-based clustering and custom PHARAOH models

To assess the performance of tissue segmentation obtained using our image clustering pipeline (HAVOC) and various PHARAOH models, we compare results on a set of representative WSIs that include (i) regions of interest (lesion) manually annotated by expert histologists and objective ground truths defined by (ii) immunohistochemical and (iii) spatial transcriptomic readouts22. While the latter non-expert molecular approaches show slightly lower concordance (Dice Scores) due to various nuances (e.g. non-specific staining of markers in necrosis tissue areas), we believe their entirely objective nature complements and further strengthens the manually provided annotations. These are described individually in more detail below. Dice scores and various enrichment metrics were used to report performance across the different methods and testing cases.

Benchmarking segmentation of image feature-based clustering and custom PHARAOH models to manual annotations

To validate the segmentation accuracy of classifiers developed using the PHARAOH workflow, we carried out comparisons of lesion (Class) Activation Maps (CAMs) with representative WSIs manually annotated by human experts. Specifically, we compared the overlap between lesional and “other” (non-lesional) regions for a set of 3 local cutaneous melanoma and 3 clear cell renal cell carcinoma cases using the same PHARAOH Melanoma (ID: e5dad8db) and Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma (ID: 82829b22) classifiers central to our study. Manual annotations were carried out using QuPath (https://qupath.github.io/). The annotated regions were projected back onto the WSI as binary 512 x 512 image patches labeled as either “lesion” or “other” (non-lesional areas). These labels were compared to tile labels with classification scores of >85% melanoma/clear cell renal cell carcinoma (lesion) or <85% (“other”/non-lesion). Overlap was benchmarked by computing a dice score. A similar approach was carried out to compare HAVOC regions to the CAMs for the same 6 cases. For this analysis, we chose to solve for relatively fewer clusters to ensure the lesion was represented by a single cluster, thereby making comparisons more objective.

To extend benchmarking across a larger diversity of cases, we also compared the overall lesional class prediction score (lesional class activation % across the entire WSI) with the proportion of tiles containing “lesion” from 200 representative (random) tiles. This process was performed across a total of 50 non-overlapping TCGA cases spanning multiple cancer types (see Supplementary Fig. 6D). For this analysis, a Person correlation was used to report the relationship between the overall WSI lesion fraction and manual estimates derived from the fraction of representative tiles showing tumor in each case. Importantly, this relationship was much stronger when using the context-appropriate PHARAOH classifier rather than an “out-of-distribution” model (r = 0.79 vs r = 0.43, n = 3 out of distribution classifiers tested). Conversely, the reported fraction of user-defined lesion tiles (up to 200 with a lesion class probability of >85%) was well over 90% in all cases, supporting that PHARAOH classifiers could robustly select and enrich for relevant lesional tiles, irrespective of the overall lesional fraction of WSIs (see Supplementary Fig. 6E). This supports the close relationship between custom classifier- and expert-based lesional segmentation across a diversity of WSIs.

More up-to-date and classifier-specific performance metrics are also included on the main page of each PHARAOH classifier to help better inform users as to how classifiers are expected to perform across different contexts. “Tile selection map” thumbnails (similar to Supplementary Fig. 6B) are also included with each analysis to allow users to quickly survey where each classifier is selecting relevant tiles from on the WSI and how this compares to the corresponding CAM.

Benchmarking segmentation of image feature-based clustering and custom PHARAOH models to immunohistochemistry-based readouts

We also used more objective immunohistochemical (IHC)-based ground truths to benchmark the performance of classifiers (regional lesion class activation/probability scores) as well as the tissue partitioning workflow (HAVOC) hosted on PHARAOH. For this, we used our local neuropathology service to identify 3 brain metastases with corresponding IHC stains of the lesion and surrounding brain tissue. To benchmark segmentation, we independently compared (i) tile-level class (activation) probability scores and (ii) HAVOC Cluster IDs to positive staining on relevant IHC slides. Briefly, for the former, we tiled representative H&E WSIs into non-overlapping image patches and assigned tiles with >85% lesion probability scores as “lesion tissue” using the “Common Brain Tumors and Surrounding Tissue Elements” (ID: 48137ffb) PHARAOH classifier (visualized as RED Boxes in Supplementary Fig. 7, panel v). For this analysis, the remaining tiles containing tissue were considered non-lesion (green box). We then used Scale Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT23) to spatially align these H&E sections to relevant immunohistochemical stains (e.g. cytokeratin for an epithelial brain metastasis). For aligned tissue regions on the IHC slide, we used a separate IHC CNN classifier to assign a “positive” (Red) label to regions in which >85% of cells are deemed positive. The remaining selected tiles on the IHC slide were assigned a “negative” label (Green). The overall overlap between the paired green (and red regions) was used to produce a dice score.

A similar series of steps was performed to evaluate specific HAVOC regions of interest (e.g. GFAP for brain tissue; CK7 for lesional tissue). In addition to a dice score between the regions of interest and the relevant IHC positive areas, the purity of these HAVOC regions was calculated by determining the number of tiles that are correspondingly IHC positive or negative for various stains. This may perhaps be a better benchmarking metric for this unsupervised analysis as different partitions may be positive for a specific marker due to both biologically-explainable or non-specific staining factors, but does not inherently affect the labeling performance of specific regions by users.

Benchmarking image feature-based clustering pattern segmentation using spatial transcriptomics

To highlight the generalizability of the HAVOC segmentation approach to multiple tissue types and non-neoplastic tissue patterns, we also compared our image clustering algorithm to objective spatial tissue boundaries defined purely based on global molecular signatures. Briefly, a H&E-stained slide of a male C57BL/6 E15.5 FFPE mouse embryo section was obtained from the 10X Genomics website (https://www.10xgenomics.com/datasets/visium-hd-cytassist-gene-expression-libraries-of-mouse-embryo) and clustered using our HAVOC pipeline (256 pixel tile size, k = 6). To benchmark the quality of the segmentation, HAVOC-derived clusters were matched to corresponding Visium 10X Genomics spots of the same tissue section by aligning the centroid of each tile to the coordinates of Visium spots using a k-dimensional tree for nearest neighbor analysis. Expression of canonical organ-specific markers was extracted from the Visium spatial gene expression data to assess the specificity of HAVOC-derived clusters to unique organs. Expression of 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase (HPD), an enzyme widely expressed in the liver, was used to isolate liver tissue. Suprabasin (SBSN), a marker of differentiated keratinocytes, was used to identify skin tissue. Expression of collagen type XI alpha 2 chain was used to identify soft tissue elements. Tubulin beta-3 chain (TUBB3), a tubulin isotype expressed exclusively in neurons, was used to identify brain tissue. After identifying four organs (brain, liver, skin, soft tissue), violin plots of gene expression among the four HAVOC clusters belonging to these organs were produced using Loupe Browser. To calculate the Dice coefficient (F1), Visium spots belonging to each of the 4 clusters were selected based on expression of the respective marker gene, which was done by removing low count Visium spots to match the same number of spots as are in the corresponding cluster. Spots not belonging to these 4 organ clusters were excluded from the analysis. A confusion matrix was produced using spots shared among both the gene expression-derived spots and the HAVOC-derived spots and marker gene spots were used as ground truth.

Statistics and reproducibility

The number of image feature-based partitions generated from each WSI was set by default to 9, but users are able to fine-tune and customize the precise number of tissue partitions based on their preferences and/or context-specific needs as described above (e.g. Fig. 1Ai). For the comparison of cellular and deep features between image feature-based clustering partitions, either all or a randomly-selected representative subset of image patches (up to 200 tiles) were selected for analysis (e.g. Fig. 1D–J). For survival (e.g. Figs. 2F, 3E), molecular (e.g. Fig. 2E, G–J), and clinical grading analysis (e.g. Fig. 3C), all available cases in the aforementioned TCGA cohorts were included. The large sizes of these cohorts (n = ~400 each) were deemed to be sufficient to produce meaningful and representative differences with respect to histological features and the chosen biological and clinical benchmarking parameters. As there was no appreciable extra cost to analyze all WSIs and we could not recruit additional cases, all available cases were included and no statistical method was employed to pre-determine sample size. As this study focused on crowd-sourcing the development of automated histopathological analytical pipelines, multi-variate analysis with clinical variables was not immediately relevant to the presented benchmarking metrics (e.g. quantifying TILs and nuclear grade) or performed. Rare WSIs were omitted only if no significant tumor regions (e.g. few image patches with a probability score >0.90 “lesion”) could be identified by the relevant PHARAOH-developed algorithm or if a relevant downstream score could not be computed (see Supplementary Data for examples). Case IDs of each sample included in each analysis are provided in the Supplementary Data. For the XGBoost models (e.g. Fig. 3F–I), the TCGA-KIRC cohort was randomized into a non-overlapping training and test set (50:50 split). The developed algorithm was blinded to the test cases until fully trained and risk scores were only calculated once following model training. The external validation cohort data was developed by stratification of ccRCC cases across the 4 nuclear grades based entirely on pathology reports by a researcher blinded to the goals of our study. The risk score for these cases were generated only after the cohort was finalized (e.g. Fig. 3D).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

WSI (.svs files) from both the TCGA-SKCM and TCGA-KIRC/KIRP cohorts are publicly available and were downloaded from the GDC Data Portal. The associated clinical information was obtained from cBioportal as described below. The scanned WSIs of the local RCC cohort developed for external validation in this study have been deposited in the ZENODO database24,25 under the accession codes: 10.5281/zenodo.13695615 (https://zenodo.org/records/13695615) and 10.5281/zenodo.13710865 (https://zenodo.org/records/13710865). Source data are also provided with this paper as Supplementary Data 1–10. The spatial transcriptomic dataset used for benchmarking segmentation is available from the 10x Genomics website (https://www.10xgenomics.com/datasets)22. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code used for extracting lesional tiles and the clear cell renal carcinoma (ID: 82829b22) and melanoma (ID: e5dad8db) models on PHARAOH are publicly available at https://bitbucket.org/diamandislabii/faust-pharaoh-2024. The code used for HAVOC and SIFT slide alignment can be found at the previously published repos https://bitbucket.org/diamandislabii/havoc & https://bitbucket.org/diamandislabii/faust-alignment-2021, respectively.

References

Djuric, U., Zadeh, G., Aldape, K. & Diamandis, P. Precision histology: how deep learning is poised to revitalize histomorphology for personalized cancer care. npj Precis. Oncol. 1, 22 (2017).

Campanella, G. et al. Clinical-grade computational pathology using weakly supervised deep learning on whole slide images. Nat. Med. 25, 1301–1309 (2019).

Bernard, J., Zeppelzauer, M., Lehmann, M., Müller, M. & Sedlmair, M. Towards user-centered active learning algorithms. Comput. Graph. Forum. 37, 121–132 (2018).

Shuyang, Z., Heittola, T. & Virtanen, T. Active learning for sound event detection. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 28, 2895–2905 (2020).

Dent, A. et al. HAVOC: Small-scale histomic mapping of cancer biodiversity across large tissue distances using deep neural networks. Sci. Adv. 9, eadg1894 (2023).

Faust, K. et al. Intelligent feature engineering and ontological mapping of brain tumour histomorphologies by deep learning. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1, 316–321 (2019).

Faust, K. et al. Unsupervised resolution of histomorphologic heterogeneity in renal cell carcinoma using a brain tumor–educated neural network. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 4, 811–821 (2020).

Graham, S. et al. Hover-Net: Simultaneous segmentation and classification of nuclei in multi-tissue histology images. Med. Image Anal. 58, 101563 (2019).

Gamper, J. et al. PanNuke dataset extension, insights and baselines. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2003.10778 (2020).

Fu, Q. et al. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncoimmunology 8, 1593806 (2019).

cellprofiler/cellprofiler. Docker Image Docker Hub. https://hub.docker.com/r/cellprofiler/cellprofiler. (2024).

Calabrò, A. et al. Effects of infiltrating lymphocytes and estrogen receptor on gene expression and prognosis in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 116, 69–77 (2009).

Thorsson, V. et al. The immune landscape of cancer. Immunity 48, 812–830.e14 (2018).

Saltz, J. et al. Spatial organization and molecular correlation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes using deep learning on pathology images. Cell Rep. 23, 181–193.e7 (2018).

Lam, K. H. B. et al. Topographic mapping of the glioblastoma proteome reveals a triple-axis model of intra-tumoral heterogeneity. Nat. Commun. 13, 116 (2022).

Xu, H. et al. A whole-slide foundation model for digital pathology from real-world data. Nat 2024 630, 181–188 (2024). 6308015.

He, K., Gkioxari, G., Dollár, P. & Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 42, 386–397 (2017).

Kyung, M. et al. Compound computer vision workflow for efficient and automated immunohistochemical analysis of whole slide images. J. Clin. Pathol. 0, 1–6 (2022).

Faust, K. et al. Visualizing histopathologic deep learning classification and anomaly detection using nonlinear feature space dimensionality reduction. BMC Bioinforma. 19, 173 (2018).

Pocock, J. et al. TIAToolbox as an end-to-end library for advanced tissue image analytics. Commun. Med. 2, 1–14 (2022).

Guan, J., Gupta, R. & Filipp, F. V. Cancer systems biology of TCGA SKCM: efficient detection of genomic drivers in melanoma. Sci. Rep. 2015 5, 1–10 (2015).

10xGenomics. Mouse Embryo from C57BL/6 Mice, HD Spatial Gene Expression Dataset by Space Ranger v3.0. https://www.10xgenomics.com/datasets?query=&page=1&configure%5BhitsPerPage%5D=50&configure%5BmaxValuesPerFacet%5D=1000 (2024).

Faust, K. et al. Integrating morphologic and molecular histopathological features through whole slide image registration and deep learning. Neuro Oncol. Adv. 4, vdac001 (2022).

Diamandis, P. PHARAOH: A collaborative crowdsourcing platform for PHenotyping and regional analysis of histology: CCRCC validation cohort grades 3 and 4. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.03.20.585977 (2024).

Diamandis, P. PHARAOH: A collaborative crowdsourcing platform for PHenotyping and regional analysis of histology: CCRCC validation cohort grades 1 and 2. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.13695615 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Project Grant (FRN: 178104) (P.D.), the Cancer Research Society Operating Grant (1280470) (P.D.) and the Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation (P.D.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.F. and P.D. conceived the idea and approach. K.F. and A.J.L. developed the computational pipelines. K.F., M.C., A.J.L. and D.G.O. developed the weakly supervised custom training approach. K.F, M.C., A.J.L., E.K.H, A.P. and P.B.Z. analyzed and interpreted data outputs. D.G.O., M.M., K.J., P.M., P.B.Z., L.V.M., M.R., M.J.A., N.S.A., R.C., R.M.S., V.F.C., N.N., Y.A., N.A., G.M.Y., A.S.A., S.J.D., Z.S.K., S.S.A., and P.E. provided annotations and cases and contributed to the design and testing of custom classifiers using the developed approach. K.F. developed the online portal. K.F., R.J.S., Xianpi D., Xianzhao D., and M.L., developed the CODIDO workflow and relevant models. K.F., A.J.L., and P.D. wrote the manuscript, with input from all other authors. P.D. supervised the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Philipp Vollmuth, Aditya Rastogi and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Faust, K., Chen, M.L., Babaei Zadeh, P. et al. PHARAOH: A collaborative crowdsourcing platform for phenotyping and regional analysis of histology. Nat Commun 16, 742 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55780-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55780-z

This article is cited by

-

Integrative whole slide image and spatial transcriptomics analysis with QuST and QuPath

npj Precision Oncology (2025)